User login

As part of its Next Accreditation System, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has introduced the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, designed to assess the learning environment of institutions that have ACGME residency and fellowship programs.1 The CLER program emphasizes the responsibility of these hospitals, multispecialty groups, and other organizations to focus on quality and safety in the health care environment of resident learning and patient care. The expectation is that emphasis on quality of care in a residency training program will influence these physicians’ approach to quality of care after graduation.2,3 The Department of Dermatology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC)(Jackson, Mississippi) saw CLER as an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the patient safety movement.

CLER Program at UMMC

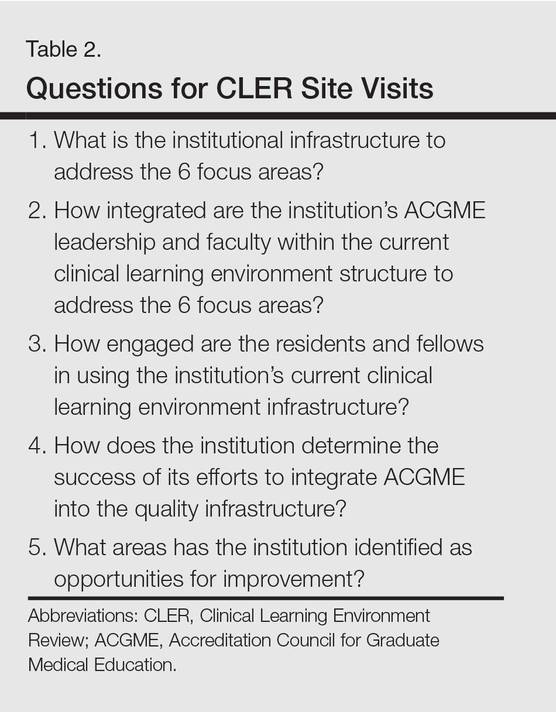

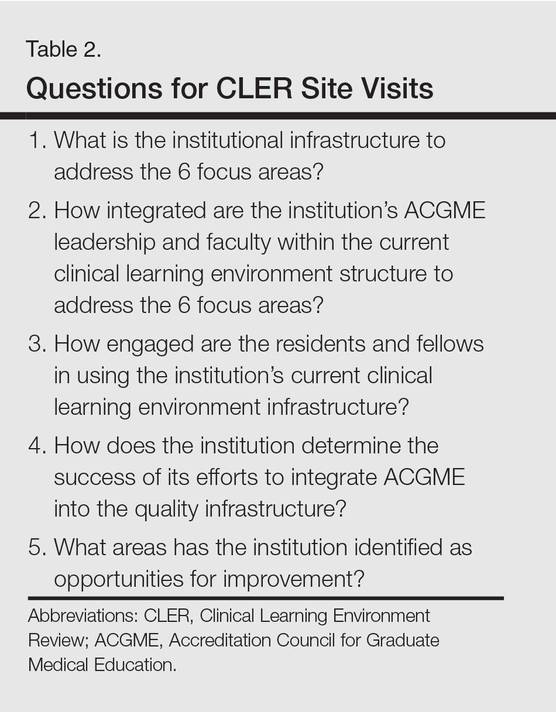

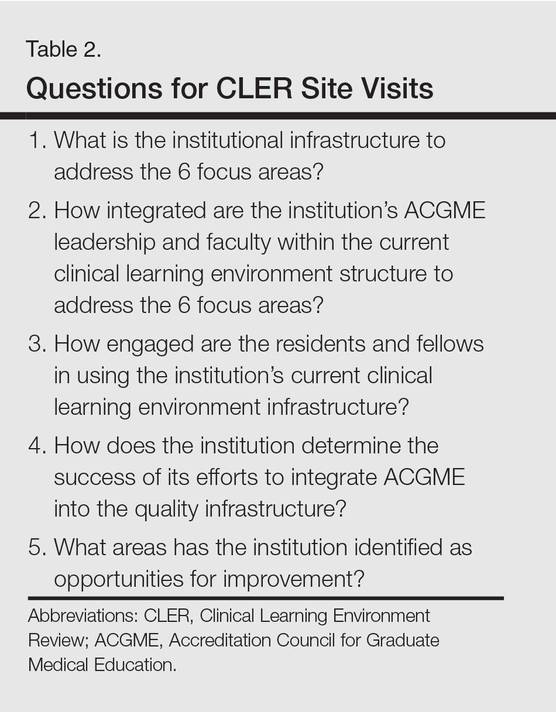

As a model CLER program at our institution, our project at the outset concentrated resident efforts on the focus areas specified by the ACGME (Table 1). We also were aware that our ACGME committee would need to answer questions during CLER site visits (Table 2). Because the data generated would not be used for accreditation decisions, there was no concern that exposing errors would jeopardize our postgraduate training certification.

The first 15 minutes of monthly faculty meetings were devoted to the presentation of a resident project, called a QA/QI (quality assurance/quality improvement) moment, that addressed ACGME focus areas 1, 2, 3, or 6 (Table 1). (Transitions in care [focus area 4] and work hours and fatigue [focus area 5] generally are less important issues in a predominantly outpatient specialty such as dermatology.) The residents were encouraged to identify areas where patient harm could occur due to poorly designed systems and to report situations in which patients actually were harmed.

Each project had to be approved by the department chairperson based on the following 4 requirements: First, the initiative must have the potential to notably impact patient safety and reduce harm. Second, residents with faculty support had to design methods to assess the identified problem. Third, participants had to design (to the best of their abilities) cost-effective and achievable interventions in a manner that would not produce unintended consequences. Fourth, residents were asked to devise a system to close the loop, ensuring that the effort put into the process was not wasted.

Findings From the CLER Program

The CLER program generates data on program and institutional attributes that have a salutatory effect on quality and safety, specifically involving 6 focus areas highlighted in Table 1. Putting residents at the center of efforts to improve the quality of care in our department proved critical to improving patient safety.

Involving residents in a series of QA/QI initiatives was logical because they rotate with faculty members. They also are in a position to view inconsistencies and to work to establish consistent patterns of patient care. In addition, our busy faculty members are charged with a variety of other clinical, educational, and administrative duties complicated by requirements in the design of a new residency training program. Faculty and residents working together were able to find problem areas in our department and devise solutions to improve those problems.

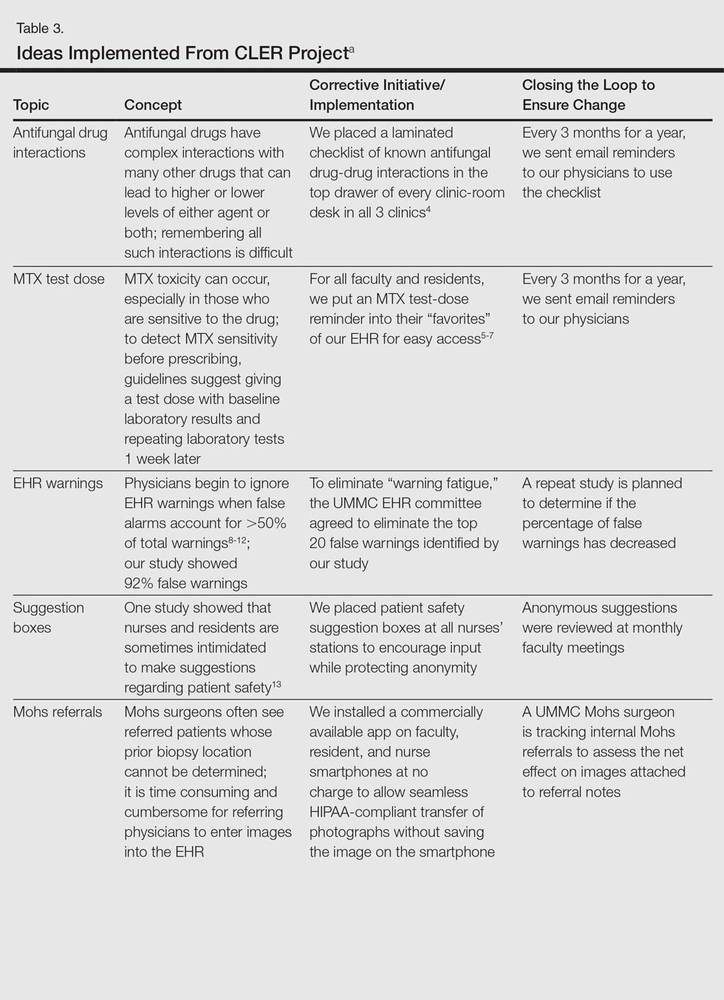

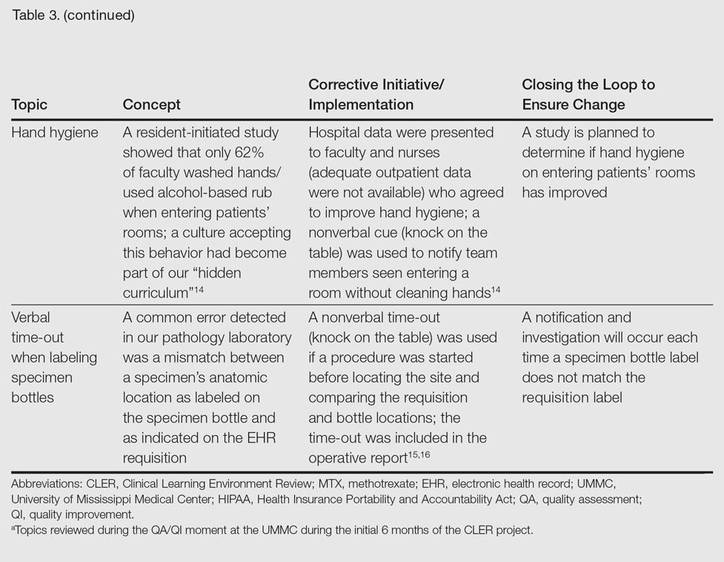

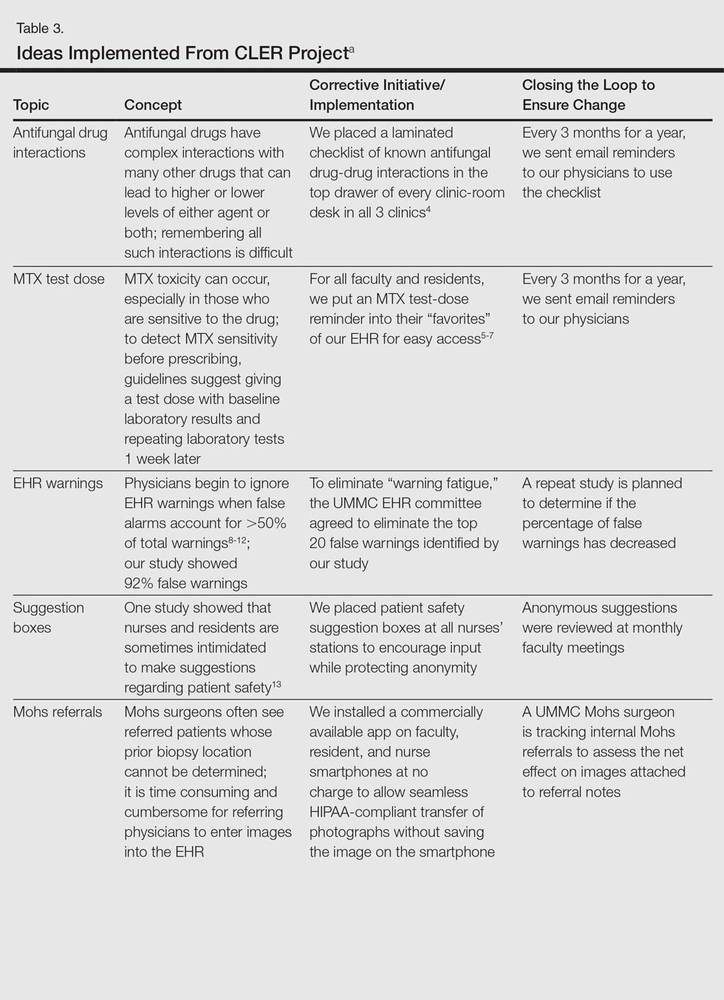

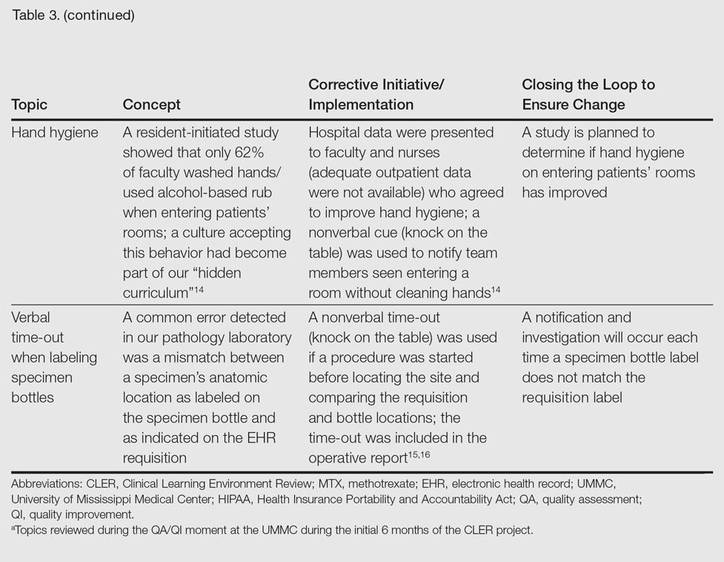

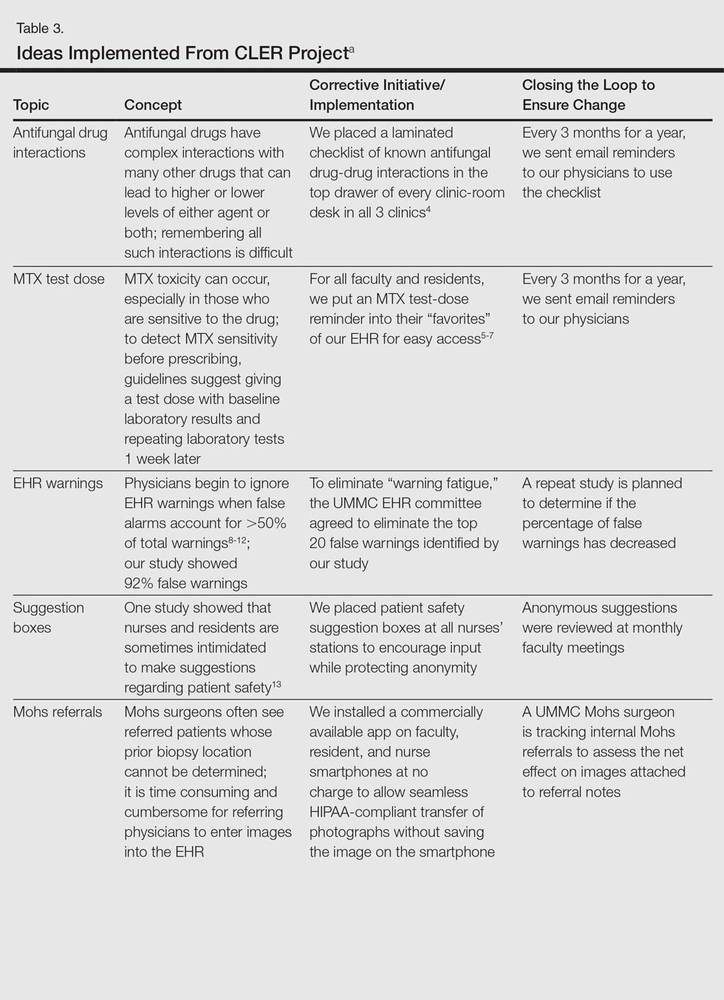

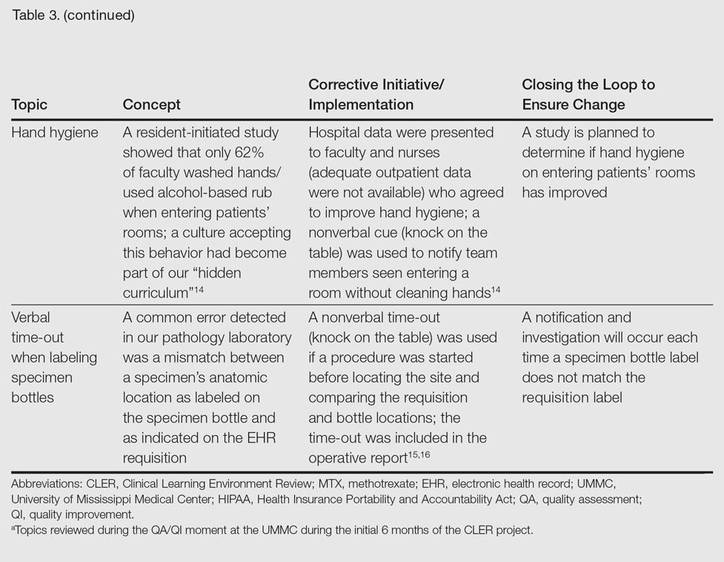

The CLER program involved a series of steps. Residents were charged with identifying errors (QA) and then devising a system to prevent similar errors from being repeated (QI)(Table 3). Efforts focused on preventing needless harm in our department. Initiatives developed by residents, who are closest to patients, have advantages over safety programs developed by the hospital’s administration. Residents became passionate about error prevention when they determined that their efforts could make a difference to patients.

Forward Thinking for Dermatology Practices

Perhaps there are lessons here that could apply to safety promotion in the practicing dermatologist’s office. The American Board of Dermatology, within the framework established by the American Board of Medical Specialties, requires physicians seeking recertification to participate in preapproved practice assessment QI exercises twice every 10 years.17 Six programs sponsored by the American Academy of Dermatology have now been approved in the areas of melanoma, biopsy follow-up measure, psoriasis, chronic urticaria, venous insufficiency, and laser- and light-based therapy for rejuvenation.18 An additional program has been approved for dermatopathologists through the American Society of Dermatopathology.19 None of these programs match the topics chosen by our residents in consultation with faculty to meet safety gaps identified in clinics at UMMC. Perhaps the next generation of performance improvement continuing medical education programs could include a pilot program for part 4 of Maintenance of Certification credit that is nonpunitive, patient focused, and allows dermatologists to design specific error-prevention solutions tailored to their individual practice in the same way residency programs are taking up this task.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The Next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051-1056.

- Philibert I, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Lannon C, et al. Quality improvement skills for pediatric residents: from lecture to implementation and sustainability. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:40-46.

- Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, et al. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89:460-468.

- Brodell RT, Elewski B. Antifungal drug interactions. avoidance requires more than memorization. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:41-43.

- Kerr IG, Jolivet J, Collin JM, et al. Test dose for predicting high-dose methotrexate infusions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:44-51.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

- Saporito FC, Menter MA. Methotrexate and psoriasis in the era of new biologic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:301-309.

- Van Der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138-147.

- Hunter KM. Implementation of an electronic medication administration record and bedside verification system. Online J Nurs Inform (OJNI). 2011;15:672.

- Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:487-491.

- Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians’ prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:531-538.

- Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, et al. Improving patient safety through medical alert management: an automated decision tool to reduce alert fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:417-421.

- Brenner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc. 2007;105:165-169.

- Rush JL, Flowers RH, Casamiquela KM, et al. Research letter: the knock: an adjunct to education opening the door to improved outpatient hand hygiene. J Am Acad Dermatol. In press.

- Lee SL. The extended surgical time-out: does it improve quality and prevent wrong-site surgery? Perm J. 2010;14:19-23.

- Altpeter T, Luckhardt K, Lewis JN, et al. Expanded surgical time out: a key to real-time data collection and quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:527-532.

- MOC requirements. American Board of Dermatology Web site. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/moc-requirements.aspx#PI. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- How AAD develops measures. American Academy of Dermatology Web site. https://www.aad.org/practice-tools/quality-care/quality-measures. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Quality assurance programs. The American Society of Dermatopathology Web site. http://www.asdp.org/education/quality-assurance-programs. Accessed January 20, 2016.

As part of its Next Accreditation System, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has introduced the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, designed to assess the learning environment of institutions that have ACGME residency and fellowship programs.1 The CLER program emphasizes the responsibility of these hospitals, multispecialty groups, and other organizations to focus on quality and safety in the health care environment of resident learning and patient care. The expectation is that emphasis on quality of care in a residency training program will influence these physicians’ approach to quality of care after graduation.2,3 The Department of Dermatology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC)(Jackson, Mississippi) saw CLER as an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the patient safety movement.

CLER Program at UMMC

As a model CLER program at our institution, our project at the outset concentrated resident efforts on the focus areas specified by the ACGME (Table 1). We also were aware that our ACGME committee would need to answer questions during CLER site visits (Table 2). Because the data generated would not be used for accreditation decisions, there was no concern that exposing errors would jeopardize our postgraduate training certification.

The first 15 minutes of monthly faculty meetings were devoted to the presentation of a resident project, called a QA/QI (quality assurance/quality improvement) moment, that addressed ACGME focus areas 1, 2, 3, or 6 (Table 1). (Transitions in care [focus area 4] and work hours and fatigue [focus area 5] generally are less important issues in a predominantly outpatient specialty such as dermatology.) The residents were encouraged to identify areas where patient harm could occur due to poorly designed systems and to report situations in which patients actually were harmed.

Each project had to be approved by the department chairperson based on the following 4 requirements: First, the initiative must have the potential to notably impact patient safety and reduce harm. Second, residents with faculty support had to design methods to assess the identified problem. Third, participants had to design (to the best of their abilities) cost-effective and achievable interventions in a manner that would not produce unintended consequences. Fourth, residents were asked to devise a system to close the loop, ensuring that the effort put into the process was not wasted.

Findings From the CLER Program

The CLER program generates data on program and institutional attributes that have a salutatory effect on quality and safety, specifically involving 6 focus areas highlighted in Table 1. Putting residents at the center of efforts to improve the quality of care in our department proved critical to improving patient safety.

Involving residents in a series of QA/QI initiatives was logical because they rotate with faculty members. They also are in a position to view inconsistencies and to work to establish consistent patterns of patient care. In addition, our busy faculty members are charged with a variety of other clinical, educational, and administrative duties complicated by requirements in the design of a new residency training program. Faculty and residents working together were able to find problem areas in our department and devise solutions to improve those problems.

The CLER program involved a series of steps. Residents were charged with identifying errors (QA) and then devising a system to prevent similar errors from being repeated (QI)(Table 3). Efforts focused on preventing needless harm in our department. Initiatives developed by residents, who are closest to patients, have advantages over safety programs developed by the hospital’s administration. Residents became passionate about error prevention when they determined that their efforts could make a difference to patients.

Forward Thinking for Dermatology Practices

Perhaps there are lessons here that could apply to safety promotion in the practicing dermatologist’s office. The American Board of Dermatology, within the framework established by the American Board of Medical Specialties, requires physicians seeking recertification to participate in preapproved practice assessment QI exercises twice every 10 years.17 Six programs sponsored by the American Academy of Dermatology have now been approved in the areas of melanoma, biopsy follow-up measure, psoriasis, chronic urticaria, venous insufficiency, and laser- and light-based therapy for rejuvenation.18 An additional program has been approved for dermatopathologists through the American Society of Dermatopathology.19 None of these programs match the topics chosen by our residents in consultation with faculty to meet safety gaps identified in clinics at UMMC. Perhaps the next generation of performance improvement continuing medical education programs could include a pilot program for part 4 of Maintenance of Certification credit that is nonpunitive, patient focused, and allows dermatologists to design specific error-prevention solutions tailored to their individual practice in the same way residency programs are taking up this task.

As part of its Next Accreditation System, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has introduced the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program, designed to assess the learning environment of institutions that have ACGME residency and fellowship programs.1 The CLER program emphasizes the responsibility of these hospitals, multispecialty groups, and other organizations to focus on quality and safety in the health care environment of resident learning and patient care. The expectation is that emphasis on quality of care in a residency training program will influence these physicians’ approach to quality of care after graduation.2,3 The Department of Dermatology at the University of Mississippi Medical Center (UMMC)(Jackson, Mississippi) saw CLER as an opportunity to demonstrate leadership in the patient safety movement.

CLER Program at UMMC

As a model CLER program at our institution, our project at the outset concentrated resident efforts on the focus areas specified by the ACGME (Table 1). We also were aware that our ACGME committee would need to answer questions during CLER site visits (Table 2). Because the data generated would not be used for accreditation decisions, there was no concern that exposing errors would jeopardize our postgraduate training certification.

The first 15 minutes of monthly faculty meetings were devoted to the presentation of a resident project, called a QA/QI (quality assurance/quality improvement) moment, that addressed ACGME focus areas 1, 2, 3, or 6 (Table 1). (Transitions in care [focus area 4] and work hours and fatigue [focus area 5] generally are less important issues in a predominantly outpatient specialty such as dermatology.) The residents were encouraged to identify areas where patient harm could occur due to poorly designed systems and to report situations in which patients actually were harmed.

Each project had to be approved by the department chairperson based on the following 4 requirements: First, the initiative must have the potential to notably impact patient safety and reduce harm. Second, residents with faculty support had to design methods to assess the identified problem. Third, participants had to design (to the best of their abilities) cost-effective and achievable interventions in a manner that would not produce unintended consequences. Fourth, residents were asked to devise a system to close the loop, ensuring that the effort put into the process was not wasted.

Findings From the CLER Program

The CLER program generates data on program and institutional attributes that have a salutatory effect on quality and safety, specifically involving 6 focus areas highlighted in Table 1. Putting residents at the center of efforts to improve the quality of care in our department proved critical to improving patient safety.

Involving residents in a series of QA/QI initiatives was logical because they rotate with faculty members. They also are in a position to view inconsistencies and to work to establish consistent patterns of patient care. In addition, our busy faculty members are charged with a variety of other clinical, educational, and administrative duties complicated by requirements in the design of a new residency training program. Faculty and residents working together were able to find problem areas in our department and devise solutions to improve those problems.

The CLER program involved a series of steps. Residents were charged with identifying errors (QA) and then devising a system to prevent similar errors from being repeated (QI)(Table 3). Efforts focused on preventing needless harm in our department. Initiatives developed by residents, who are closest to patients, have advantages over safety programs developed by the hospital’s administration. Residents became passionate about error prevention when they determined that their efforts could make a difference to patients.

Forward Thinking for Dermatology Practices

Perhaps there are lessons here that could apply to safety promotion in the practicing dermatologist’s office. The American Board of Dermatology, within the framework established by the American Board of Medical Specialties, requires physicians seeking recertification to participate in preapproved practice assessment QI exercises twice every 10 years.17 Six programs sponsored by the American Academy of Dermatology have now been approved in the areas of melanoma, biopsy follow-up measure, psoriasis, chronic urticaria, venous insufficiency, and laser- and light-based therapy for rejuvenation.18 An additional program has been approved for dermatopathologists through the American Society of Dermatopathology.19 None of these programs match the topics chosen by our residents in consultation with faculty to meet safety gaps identified in clinics at UMMC. Perhaps the next generation of performance improvement continuing medical education programs could include a pilot program for part 4 of Maintenance of Certification credit that is nonpunitive, patient focused, and allows dermatologists to design specific error-prevention solutions tailored to their individual practice in the same way residency programs are taking up this task.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The Next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051-1056.

- Philibert I, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Lannon C, et al. Quality improvement skills for pediatric residents: from lecture to implementation and sustainability. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:40-46.

- Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, et al. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89:460-468.

- Brodell RT, Elewski B. Antifungal drug interactions. avoidance requires more than memorization. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:41-43.

- Kerr IG, Jolivet J, Collin JM, et al. Test dose for predicting high-dose methotrexate infusions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:44-51.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

- Saporito FC, Menter MA. Methotrexate and psoriasis in the era of new biologic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:301-309.

- Van Der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138-147.

- Hunter KM. Implementation of an electronic medication administration record and bedside verification system. Online J Nurs Inform (OJNI). 2011;15:672.

- Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:487-491.

- Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians’ prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:531-538.

- Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, et al. Improving patient safety through medical alert management: an automated decision tool to reduce alert fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:417-421.

- Brenner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc. 2007;105:165-169.

- Rush JL, Flowers RH, Casamiquela KM, et al. Research letter: the knock: an adjunct to education opening the door to improved outpatient hand hygiene. J Am Acad Dermatol. In press.

- Lee SL. The extended surgical time-out: does it improve quality and prevent wrong-site surgery? Perm J. 2010;14:19-23.

- Altpeter T, Luckhardt K, Lewis JN, et al. Expanded surgical time out: a key to real-time data collection and quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:527-532.

- MOC requirements. American Board of Dermatology Web site. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/moc-requirements.aspx#PI. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- How AAD develops measures. American Academy of Dermatology Web site. https://www.aad.org/practice-tools/quality-care/quality-measures. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Quality assurance programs. The American Society of Dermatopathology Web site. http://www.asdp.org/education/quality-assurance-programs. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, et al. The Next GME accreditation system—rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1051-1056.

- Philibert I, Gonzalez del Rey JA, Lannon C, et al. Quality improvement skills for pediatric residents: from lecture to implementation and sustainability. Acad Pediatr. 2014;14:40-46.

- Vidyarthi AR, Green AL, Rosenbluth G, et al. Engaging residents and fellows to improve institution-wide quality: the first six years of a novel financial incentive program. Acad Med. 2014;89:460-468.

- Brodell RT, Elewski B. Antifungal drug interactions. avoidance requires more than memorization. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:41-43.

- Kerr IG, Jolivet J, Collin JM, et al. Test dose for predicting high-dose methotrexate infusions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1983;33:44-51.

- Menter A, Korman NJ, Elmets CA, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis: section 4. guidelines of care for the management and treatment of psoriasis with traditional systemic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;61:451-485.

- Saporito FC, Menter MA. Methotrexate and psoriasis in the era of new biologic agents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;50:301-309.

- Van Der Sijs H, Aarts J, Vulto A, et al. Overriding of drug safety alerts in computerized physician order entry. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13:138-147.

- Hunter KM. Implementation of an electronic medication administration record and bedside verification system. Online J Nurs Inform (OJNI). 2011;15:672.

- Nanji KC, Slight SP, Seger DL, et al. Overrides of medication-related clinical decision support alerts in outpatients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21:487-491.

- Schedlbauer A, Prasad V, Mulvaney C, et al. What evidence supports the use of computerized alerts and prompts to improve clinicians’ prescribing behavior? J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2009;16:531-538.

- Lee EK, Mejia AF, Senior T, et al. Improving patient safety through medical alert management: an automated decision tool to reduce alert fatigue. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2010;2010:417-421.

- Brenner AB. Physician and nurse relationships, a key to patient safety. J Ky Med Assoc. 2007;105:165-169.

- Rush JL, Flowers RH, Casamiquela KM, et al. Research letter: the knock: an adjunct to education opening the door to improved outpatient hand hygiene. J Am Acad Dermatol. In press.

- Lee SL. The extended surgical time-out: does it improve quality and prevent wrong-site surgery? Perm J. 2010;14:19-23.

- Altpeter T, Luckhardt K, Lewis JN, et al. Expanded surgical time out: a key to real-time data collection and quality improvement. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204:527-532.

- MOC requirements. American Board of Dermatology Web site. https://www.abderm.org/diplomates/fulfilling-moc-requirements/moc-requirements.aspx#PI. Accessed January 18, 2016.

- How AAD develops measures. American Academy of Dermatology Web site. https://www.aad.org/practice-tools/quality-care/quality-measures. Accessed January 20, 2016.

- Quality assurance programs. The American Society of Dermatopathology Web site. http://www.asdp.org/education/quality-assurance-programs. Accessed January 20, 2016.

Practice Points

- The Clinical Learning Environment Review mobilizes residency and fellowship training programs in the movement to improve the quality of patient care.

- Quality assessment/quality improvement (QA/QI) projects enhance communication between residents and faculty and promote systems that improve patient safety.

- Emphasis on resident-initiated QA/QI impacts quality of care in clinical practice long after graduation.