User login

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is an emerging therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mental health indications but not widely available in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). rTMS uses a device to create magnetic fields that cause electrical current to flow into targeted neurons in the brain.1 The area of the brain targeted depends on the shape of the magnetic coil and dose of stimulation (Figures 1 and 2). The most common coil shape is the figure-8 coil, which is believed to stimulate about a 2- to 3-cm2 area of the brain at a depth of about 2 cm from the coil surface. The stimulus is thought to activate certain nerve growth factors and ultimately relevant neurotransmitters in the stimulated areas and parts of the brain connected to where the stimulus occurs.2

The most common clinical use of rTMS is for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). The FDA has approved rTMS for the treatment of MDD and for at least 4 device manufacturers. The treatment has been studied in multiple clinical trials.3 An overview of these trials, additional rTMS training and educational materials, and device information can be accessed at www.mirecc.va.gov/visn21/education/tms_education.asp. rTMS for MDD administers a personalized dose with stimulation delivered over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. A typical clinical course runs for 40 minutes a day for 20 to 30 sessions. In addition to studies of depression,1,4-7 rTMS has been studied for the following diseases and conditions:

- Headache (especially migraine)8

- Alzheimer disease9

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)10

- Obesity11

- Schizophrenia12

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)13

- Alcohol and nicotine dependence14

The FDA also has approved the use of rTMS for OCD. In addition, some health care providers (HCPs) are treating depression with rTMS in conjunction with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Treatment for Veterans

MDD is one of the most significant risk factors for suicide. Therefore, treating depression with rTMS would likely diminish suicide risk. The annual suicide rate among veterans has been higher than the national average.15 However, most of these veterans are not getting their care at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Major efforts at the VA have been made to address this problem, including modification and promotion of the Veterans Crisis Line, increased mental health clinic hours, mental health same-day appointment availability for veterans, as well as raising awareness of suicide and suicidal ideation.16 George and colleagues showed that it is safe and feasible to treat acutely suicidal inpatients at a VA or US Department of Defense hospital over an intensive 3 day, 3 treatments per day regimen. This regimen would be potentially useful in a suicidal inpatient population, a technically and ethically difficult group to study.17

MDD in many patients can be chronic and reoccurring with medication and psychotherapy providing inadequate relief.17 There clearly is a need for additional treatment options. MDD and OCD are the only indications that have received FDA approval for rTMS use. The initial FDA approval for MDD was based on a 2007 study of medication-free patients who had failed previous therapy and found a significant effect of rTMS compared with a sham procedure.7 MDD remains a common problem among veterans who have failed one or more antidepressant medications. Such patients might benefit from rTMS.6,18

rTMS has several advantages over ECT, another significant FDA-approved, nonpharmacologic treatment alternative for medication-refractory MDD. rTMS is less invasive, requires fewer resources, does not require anesthesia or restrict activities, and does not cause memory loss. After an rTMS treatment, the patient can drive home.

Nationwide Pilot Program

The VA pilot program was created to supply rTMS machines nationwide to VHA sites and to offer a framework for establishing a clinical program. Preliminary program evaluation data suggest patients experienced a reduction in depression and suicidal ideation.

There were many challenges to implementation; for example, one VA site was eager to start using the device but could not secure space or personnel. An interdisciplinary team consisting of physicians, nurses, psychologists, suicide prevention coordinators, and others in the VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Precision Neurostimulation Clinic (PNC) has been instrumental in overcoming these challenges. VAPAHCS oversees the pilot and employs the national director.

Thirty-five sites nationwide were initially selected due to their ability to provide space for a rTMS machine and appropriate staffing to set up and run a Clinic (Figure 3). The pilot started with tertiary care VA medical centers then expanded to include community-based outpatient clinics as resources permitted. Sites that were unable to meet these standards were not included. Of these 35 original sites, 26 are treating patients and collecting data. Some early delays were due to unassigned relative value units (RVUs) to rTMS, which since have been revised as imputed RVU values. The American Medical Association established and defined RVUs to compare the value of different health care roles.19 The clinics have been established with smooth operations as the pilot program has provided the infrastructure.

REDCap (www.project-redcap.org), a data collection tool used primarily in academic research settings, was selected to gather program evaluation data through patient questionnaires informed by the VHA measurement-based care initiative. Standard psychometrics were readily available in the VHA application and REDCap Mental Health Assistant includes the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) Brief Symptom Inventory 18, Posttraumatic Checklist 5, Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, and Quality of Life Inventory. The Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scale (TCFES), which can be completed in 30 to 35 minutes and is a measure of overall function of relevant relationships, also may be added. Future studies are needed to confirm psychometrics of this scale in this setting, but the TCFES metric is widely used for similar purposes.

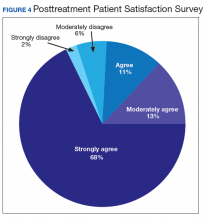

Nationwide, more than 950 patients have started treatment (ie, including active, completed, and discontinued treatment) and 412 veterans have completed the rTMS treatment. The goal of the program evaluation is to examine large scale rTMS efficacy in a large veteran population as well as determine predictors of individual patient response. Nationwide, PHQ-9 depression scores declined from a pretreatment average (SD) of 18.2 (5.5; range, 5-27) to a posttreatment average (SD) of 11.0 (7.1; range, 0-27). Patients also have indicated a high level of satisfaction with the treatment (Figure 4). Collecting data on a national level is a powerful way to examine rTMS efficacy and predictors of response that might be lost in a smaller subset of cases.

Implementation

It took 11 months for the VA contracting department to determine which machine to buy. However, the lengthy process assured that the equipment selected met all standards for clinical safety and efficacy. Furthermore, provision was made to allow for additional orders as new sites came online as well as upgrading the equipment for advances in technology.

The PNC set up several training programs to ensure proper use of this novel treatment. The education is ongoing and available as new sites are identified and initiated. The education includes, but is not limited to, in-person onsite and offsite training programs, online training modules that are available in the VA Electronic Educational Services (EES), and video telehealth consultations. Participants can view online lectures and then receive hands-on training as part of the educational program. Up to 3 HCPs for each site can receive funding to attend. Online programs also are available for new material to support continuing medical education. However, hands-on training is essential to understand how to obtain the motor threshold, which is used to determine the strength of the rTMS stimulus dose. Furthermore, hands-on training is essential for the proper localization of the stimulus, which is determined by certain anatomical landmarks. A phantom mannequin (ERIK [Evaluating Resting motor threshold and Insuring Kappa]) has been developed to assist in the hands-on learning.20

Relative Value Units

The VHA uses RVUs to properly account for workload and clinician activities. As a result, RVUs play an essential role as a currency that denotes the relative value of one type of clinical activity when compared with other activities. Depending on the treating specialty, clinicians generally use procedure codes outlined in the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code set or the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) for medical billing. Most insurance carriers use RVUs set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) system as a standard system to determine HCP reimbursement for medical procedures.

The CPT codes associated with rTMS currently are 90867 to 90869. CMS had initially assigned a zero RVU to these CPT codes due to wide variations in the cost of performing rTMS. When we began implementing rTMS in the VHA, the lack of RVUs for rTMS rendered it impossible to show clinical workload for this activity using established VHA clinical accounting methods. The lack of RVUs assigned to rTMS CPT codes made justification for this treatment to clinical management difficult, which limited its clinical use in the VHA. In addition, HCPs who were using rTMS to treat severely ill veterans appeared artificially unproductive despite a significant patient workload. As we and VHA leadership became aware the program could not be staffed locally without getting workload credit for work done, the value was raised to 1.37 for treatment (90868) and 2.12 and 1.93 for evaluations (90867) and reevaluations (90869), respectively, thus reducing a potential roadblock to implementation.

Challenges as the Program Expands

Future challenges include upgrading machines to do intermittent θ burst stimulation (iTBS), which decreases the standard treatment time from 37.5 minutes to 3 minutes. Both patients and HCPs find iTBS to have similar tolerability to standard rTMS but in much less time. iTBS mimics endogenous θ rhythms and has been shown to be noninferior to rTMS for depression.21,22 Several devices have received FDA approval to treat MDD, including the Magstim and MagVenture TMS devices used in this program.

A major challenge for the VHA with rTMS will be to maintain a consistent level of competence and training. There is a need for continued maintenance of staff competence with ongoing training and training for new staff. Novel ways of training operators have been developed including ERIK.

Determining treatment interaction with other psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies is another challenge. Currently, rTMS is considered an adjunctive treatment added to the current patient treatment plan. We do not know yet how best to incorporate this somatic treatment with other approaches, and further research is necessary. A key issue is to determine which approach provides the best long-term results for a patient at risk for recurrence of depression. In addition, more research into maintaining healthy relationships for veterans with both MDD and PTSD is needed.

Many misconceptions exist about rTMS and HCPs need to be educated about the benefits of this modality. In addition, patients should understand the differences between rTMS and ECT. Even with newer approaches that streamline rTMS, the therapy remains costly in terms of direct costs as well as patient and HCP time.

Streamlining rTMS treatment remains an important concern. Compressing treatment schedules (ie, many treatments delivered to a patient in a single day) would allow the entire process to be delivered in days, not weeks. This would be especially advantageous to patients who live far from a treatment site. Performing multiple rTMS daily treatments is especially feasible with iTBS with its short treatment time.

Conclusions

rTMS is an emerging modality with both established and novel applications. The best studied application is treatment resistant MDD. Currently, rTMS has only been approved by the FDA for treatment of MDD. A pilot program was established by the VHA to distribute 30 rTMS machines sites nationwide. Results from data collected by these sites have shown patients improving on standard psychometric scales. Future changes include upgrading the machines to provide θ bursts, which has been shown to be faster and noninferior. Integrating rTMS with other pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies remains poorly understood and needs more research.

1. George MS, Wassermann EM, Williams WA, et al. Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves mood in depression. Neuroreport. 1995;6(14):1853‐1856. doi:10.1097/00001756-199510020-00008

2. Tik M, Hoffmann A, Sladky R, et al. Towards understanding rTMS mechanism of action: stimulation of the DLPFC causes network-specific increase in functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2017;162:289‐296. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.09.022

3. Perera T, George MS, Grammer G, Janicak PG, Pascual-Leone A, Wirecki TS. The Clinical TMS Society consensus review and treatment recommendations for TMS therapy for major depressive disorder. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(3):336‐346. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2016.03.010

4. George MS, Taylor JJ, Short EB. The expanding evidence base for rTMS treatment of depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(1):13‐18. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835ab46d

5. Lisanby SH, Husain MM, Rosenquist PB, et al. Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: clinical predictors of outcome in a multisite, randomized controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(2):522‐534. doi:10.1038/npp.2008.118

6. Yesavage JA, Fairchild JK, Mi Z, et al. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on treatment-resistant major depression in US veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):884‐893. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1483

7. O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1208‐1216. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018

8. Stilling JM, Monchi O, Amoozegar F, Debert CT. Transcranial magnetic and direct current stimulation (TMS/tDCS) for the treatment of headache: a systematic review. Headache. 2019;59(3):339‐357. doi:10.1111/head.13479

9. Lin Y, Jiang WJ, Shan PY, et al. The role of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2019;398:184‐191. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2019.01.038

10. Carmi L, Tendler A, Bystritsky A, et al. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(11):931‐938. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18101180

11. Song S, Zilverstand A, Gui W, Li HJ, Zhou X. Effects of single-session versus multi-session non-invasive brain stimulation on craving and consumption in individuals with drug addiction, eating disorders or obesity: a meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(3):606‐618. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2018.12.975

12. Wagner E, Wobrock T, Kunze B, et al. Efficacy of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in schizophrenia patients with treatment-resistant negative symptoms treated with clozapine. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:370‐376. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.021

13. Kozel FA, Van Trees K, Larson V, et al. One hertz versus ten hertz repetitive TMS treatment of PTSD: a randomized clinical trial. Psychiatry Res. 2019;273:153‐162. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.004

14. Coles AS, Kozak K, George TP. A review of brain stimulation methods to treat substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2018;27(2):71‐91. doi:10.1111/ajad.12674

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2019 National veteran suicide prevention annual report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf. Published September 19, 2019. Accessed May 18, 2020.

16. Ritchie EC. Improving Veteran engagement with mental health care. Fed Pract. 2017;34(8):55‐56.

17. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1231‐1242. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052963

18. Kozel FA, Hernandez M, Van Trees K, et al. Clinical repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for veterans with major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(4):242‐248.

19. National Health Policy Forum. The basics: relative value units (RVUs). https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/master/borndig/101513853/Relative%20Value%20Units.pdf. Published January 12, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2020.

20. Finetto C, Glusman C, Doolittle J, George MS. Presenting ERIK, the TMS phantom: a novel device for training and testing operators. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(4):1095‐1097. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2019.04.01521. Trevizol AP, Vigod SN, Daskalakis ZJ, Vila-Rodriguez F, Downar J, Blumberger DM. Intermittent theta burst stimulation for major depression during pregnancy. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(3):772‐774. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2019.01.003

22. Blumberger DM, Vila-Rodriguez F, Thorpe KE, et al. Effectiveness of theta burst versus high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression (THREE-D): a randomised non-inferiority trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2018 Jun 23;391(10139):e24]. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1683‐1692. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30295-2

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is an emerging therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mental health indications but not widely available in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). rTMS uses a device to create magnetic fields that cause electrical current to flow into targeted neurons in the brain.1 The area of the brain targeted depends on the shape of the magnetic coil and dose of stimulation (Figures 1 and 2). The most common coil shape is the figure-8 coil, which is believed to stimulate about a 2- to 3-cm2 area of the brain at a depth of about 2 cm from the coil surface. The stimulus is thought to activate certain nerve growth factors and ultimately relevant neurotransmitters in the stimulated areas and parts of the brain connected to where the stimulus occurs.2

The most common clinical use of rTMS is for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). The FDA has approved rTMS for the treatment of MDD and for at least 4 device manufacturers. The treatment has been studied in multiple clinical trials.3 An overview of these trials, additional rTMS training and educational materials, and device information can be accessed at www.mirecc.va.gov/visn21/education/tms_education.asp. rTMS for MDD administers a personalized dose with stimulation delivered over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. A typical clinical course runs for 40 minutes a day for 20 to 30 sessions. In addition to studies of depression,1,4-7 rTMS has been studied for the following diseases and conditions:

- Headache (especially migraine)8

- Alzheimer disease9

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)10

- Obesity11

- Schizophrenia12

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)13

- Alcohol and nicotine dependence14

The FDA also has approved the use of rTMS for OCD. In addition, some health care providers (HCPs) are treating depression with rTMS in conjunction with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Treatment for Veterans

MDD is one of the most significant risk factors for suicide. Therefore, treating depression with rTMS would likely diminish suicide risk. The annual suicide rate among veterans has been higher than the national average.15 However, most of these veterans are not getting their care at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Major efforts at the VA have been made to address this problem, including modification and promotion of the Veterans Crisis Line, increased mental health clinic hours, mental health same-day appointment availability for veterans, as well as raising awareness of suicide and suicidal ideation.16 George and colleagues showed that it is safe and feasible to treat acutely suicidal inpatients at a VA or US Department of Defense hospital over an intensive 3 day, 3 treatments per day regimen. This regimen would be potentially useful in a suicidal inpatient population, a technically and ethically difficult group to study.17

MDD in many patients can be chronic and reoccurring with medication and psychotherapy providing inadequate relief.17 There clearly is a need for additional treatment options. MDD and OCD are the only indications that have received FDA approval for rTMS use. The initial FDA approval for MDD was based on a 2007 study of medication-free patients who had failed previous therapy and found a significant effect of rTMS compared with a sham procedure.7 MDD remains a common problem among veterans who have failed one or more antidepressant medications. Such patients might benefit from rTMS.6,18

rTMS has several advantages over ECT, another significant FDA-approved, nonpharmacologic treatment alternative for medication-refractory MDD. rTMS is less invasive, requires fewer resources, does not require anesthesia or restrict activities, and does not cause memory loss. After an rTMS treatment, the patient can drive home.

Nationwide Pilot Program

The VA pilot program was created to supply rTMS machines nationwide to VHA sites and to offer a framework for establishing a clinical program. Preliminary program evaluation data suggest patients experienced a reduction in depression and suicidal ideation.

There were many challenges to implementation; for example, one VA site was eager to start using the device but could not secure space or personnel. An interdisciplinary team consisting of physicians, nurses, psychologists, suicide prevention coordinators, and others in the VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Precision Neurostimulation Clinic (PNC) has been instrumental in overcoming these challenges. VAPAHCS oversees the pilot and employs the national director.

Thirty-five sites nationwide were initially selected due to their ability to provide space for a rTMS machine and appropriate staffing to set up and run a Clinic (Figure 3). The pilot started with tertiary care VA medical centers then expanded to include community-based outpatient clinics as resources permitted. Sites that were unable to meet these standards were not included. Of these 35 original sites, 26 are treating patients and collecting data. Some early delays were due to unassigned relative value units (RVUs) to rTMS, which since have been revised as imputed RVU values. The American Medical Association established and defined RVUs to compare the value of different health care roles.19 The clinics have been established with smooth operations as the pilot program has provided the infrastructure.

REDCap (www.project-redcap.org), a data collection tool used primarily in academic research settings, was selected to gather program evaluation data through patient questionnaires informed by the VHA measurement-based care initiative. Standard psychometrics were readily available in the VHA application and REDCap Mental Health Assistant includes the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) Brief Symptom Inventory 18, Posttraumatic Checklist 5, Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, and Quality of Life Inventory. The Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scale (TCFES), which can be completed in 30 to 35 minutes and is a measure of overall function of relevant relationships, also may be added. Future studies are needed to confirm psychometrics of this scale in this setting, but the TCFES metric is widely used for similar purposes.

Nationwide, more than 950 patients have started treatment (ie, including active, completed, and discontinued treatment) and 412 veterans have completed the rTMS treatment. The goal of the program evaluation is to examine large scale rTMS efficacy in a large veteran population as well as determine predictors of individual patient response. Nationwide, PHQ-9 depression scores declined from a pretreatment average (SD) of 18.2 (5.5; range, 5-27) to a posttreatment average (SD) of 11.0 (7.1; range, 0-27). Patients also have indicated a high level of satisfaction with the treatment (Figure 4). Collecting data on a national level is a powerful way to examine rTMS efficacy and predictors of response that might be lost in a smaller subset of cases.

Implementation

It took 11 months for the VA contracting department to determine which machine to buy. However, the lengthy process assured that the equipment selected met all standards for clinical safety and efficacy. Furthermore, provision was made to allow for additional orders as new sites came online as well as upgrading the equipment for advances in technology.

The PNC set up several training programs to ensure proper use of this novel treatment. The education is ongoing and available as new sites are identified and initiated. The education includes, but is not limited to, in-person onsite and offsite training programs, online training modules that are available in the VA Electronic Educational Services (EES), and video telehealth consultations. Participants can view online lectures and then receive hands-on training as part of the educational program. Up to 3 HCPs for each site can receive funding to attend. Online programs also are available for new material to support continuing medical education. However, hands-on training is essential to understand how to obtain the motor threshold, which is used to determine the strength of the rTMS stimulus dose. Furthermore, hands-on training is essential for the proper localization of the stimulus, which is determined by certain anatomical landmarks. A phantom mannequin (ERIK [Evaluating Resting motor threshold and Insuring Kappa]) has been developed to assist in the hands-on learning.20

Relative Value Units

The VHA uses RVUs to properly account for workload and clinician activities. As a result, RVUs play an essential role as a currency that denotes the relative value of one type of clinical activity when compared with other activities. Depending on the treating specialty, clinicians generally use procedure codes outlined in the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code set or the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) for medical billing. Most insurance carriers use RVUs set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) system as a standard system to determine HCP reimbursement for medical procedures.

The CPT codes associated with rTMS currently are 90867 to 90869. CMS had initially assigned a zero RVU to these CPT codes due to wide variations in the cost of performing rTMS. When we began implementing rTMS in the VHA, the lack of RVUs for rTMS rendered it impossible to show clinical workload for this activity using established VHA clinical accounting methods. The lack of RVUs assigned to rTMS CPT codes made justification for this treatment to clinical management difficult, which limited its clinical use in the VHA. In addition, HCPs who were using rTMS to treat severely ill veterans appeared artificially unproductive despite a significant patient workload. As we and VHA leadership became aware the program could not be staffed locally without getting workload credit for work done, the value was raised to 1.37 for treatment (90868) and 2.12 and 1.93 for evaluations (90867) and reevaluations (90869), respectively, thus reducing a potential roadblock to implementation.

Challenges as the Program Expands

Future challenges include upgrading machines to do intermittent θ burst stimulation (iTBS), which decreases the standard treatment time from 37.5 minutes to 3 minutes. Both patients and HCPs find iTBS to have similar tolerability to standard rTMS but in much less time. iTBS mimics endogenous θ rhythms and has been shown to be noninferior to rTMS for depression.21,22 Several devices have received FDA approval to treat MDD, including the Magstim and MagVenture TMS devices used in this program.

A major challenge for the VHA with rTMS will be to maintain a consistent level of competence and training. There is a need for continued maintenance of staff competence with ongoing training and training for new staff. Novel ways of training operators have been developed including ERIK.

Determining treatment interaction with other psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies is another challenge. Currently, rTMS is considered an adjunctive treatment added to the current patient treatment plan. We do not know yet how best to incorporate this somatic treatment with other approaches, and further research is necessary. A key issue is to determine which approach provides the best long-term results for a patient at risk for recurrence of depression. In addition, more research into maintaining healthy relationships for veterans with both MDD and PTSD is needed.

Many misconceptions exist about rTMS and HCPs need to be educated about the benefits of this modality. In addition, patients should understand the differences between rTMS and ECT. Even with newer approaches that streamline rTMS, the therapy remains costly in terms of direct costs as well as patient and HCP time.

Streamlining rTMS treatment remains an important concern. Compressing treatment schedules (ie, many treatments delivered to a patient in a single day) would allow the entire process to be delivered in days, not weeks. This would be especially advantageous to patients who live far from a treatment site. Performing multiple rTMS daily treatments is especially feasible with iTBS with its short treatment time.

Conclusions

rTMS is an emerging modality with both established and novel applications. The best studied application is treatment resistant MDD. Currently, rTMS has only been approved by the FDA for treatment of MDD. A pilot program was established by the VHA to distribute 30 rTMS machines sites nationwide. Results from data collected by these sites have shown patients improving on standard psychometric scales. Future changes include upgrading the machines to provide θ bursts, which has been shown to be faster and noninferior. Integrating rTMS with other pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies remains poorly understood and needs more research.

Repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) is an emerging therapy approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for mental health indications but not widely available in the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA). rTMS uses a device to create magnetic fields that cause electrical current to flow into targeted neurons in the brain.1 The area of the brain targeted depends on the shape of the magnetic coil and dose of stimulation (Figures 1 and 2). The most common coil shape is the figure-8 coil, which is believed to stimulate about a 2- to 3-cm2 area of the brain at a depth of about 2 cm from the coil surface. The stimulus is thought to activate certain nerve growth factors and ultimately relevant neurotransmitters in the stimulated areas and parts of the brain connected to where the stimulus occurs.2

The most common clinical use of rTMS is for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). The FDA has approved rTMS for the treatment of MDD and for at least 4 device manufacturers. The treatment has been studied in multiple clinical trials.3 An overview of these trials, additional rTMS training and educational materials, and device information can be accessed at www.mirecc.va.gov/visn21/education/tms_education.asp. rTMS for MDD administers a personalized dose with stimulation delivered over the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. A typical clinical course runs for 40 minutes a day for 20 to 30 sessions. In addition to studies of depression,1,4-7 rTMS has been studied for the following diseases and conditions:

- Headache (especially migraine)8

- Alzheimer disease9

- Obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD)10

- Obesity11

- Schizophrenia12

- Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)13

- Alcohol and nicotine dependence14

The FDA also has approved the use of rTMS for OCD. In addition, some health care providers (HCPs) are treating depression with rTMS in conjunction with electroconvulsive therapy (ECT).

Treatment for Veterans

MDD is one of the most significant risk factors for suicide. Therefore, treating depression with rTMS would likely diminish suicide risk. The annual suicide rate among veterans has been higher than the national average.15 However, most of these veterans are not getting their care at the Veterans Health Administration (VHA). Major efforts at the VA have been made to address this problem, including modification and promotion of the Veterans Crisis Line, increased mental health clinic hours, mental health same-day appointment availability for veterans, as well as raising awareness of suicide and suicidal ideation.16 George and colleagues showed that it is safe and feasible to treat acutely suicidal inpatients at a VA or US Department of Defense hospital over an intensive 3 day, 3 treatments per day regimen. This regimen would be potentially useful in a suicidal inpatient population, a technically and ethically difficult group to study.17

MDD in many patients can be chronic and reoccurring with medication and psychotherapy providing inadequate relief.17 There clearly is a need for additional treatment options. MDD and OCD are the only indications that have received FDA approval for rTMS use. The initial FDA approval for MDD was based on a 2007 study of medication-free patients who had failed previous therapy and found a significant effect of rTMS compared with a sham procedure.7 MDD remains a common problem among veterans who have failed one or more antidepressant medications. Such patients might benefit from rTMS.6,18

rTMS has several advantages over ECT, another significant FDA-approved, nonpharmacologic treatment alternative for medication-refractory MDD. rTMS is less invasive, requires fewer resources, does not require anesthesia or restrict activities, and does not cause memory loss. After an rTMS treatment, the patient can drive home.

Nationwide Pilot Program

The VA pilot program was created to supply rTMS machines nationwide to VHA sites and to offer a framework for establishing a clinical program. Preliminary program evaluation data suggest patients experienced a reduction in depression and suicidal ideation.

There were many challenges to implementation; for example, one VA site was eager to start using the device but could not secure space or personnel. An interdisciplinary team consisting of physicians, nurses, psychologists, suicide prevention coordinators, and others in the VA Palo Alto Health Care System (VAPAHCS) Precision Neurostimulation Clinic (PNC) has been instrumental in overcoming these challenges. VAPAHCS oversees the pilot and employs the national director.

Thirty-five sites nationwide were initially selected due to their ability to provide space for a rTMS machine and appropriate staffing to set up and run a Clinic (Figure 3). The pilot started with tertiary care VA medical centers then expanded to include community-based outpatient clinics as resources permitted. Sites that were unable to meet these standards were not included. Of these 35 original sites, 26 are treating patients and collecting data. Some early delays were due to unassigned relative value units (RVUs) to rTMS, which since have been revised as imputed RVU values. The American Medical Association established and defined RVUs to compare the value of different health care roles.19 The clinics have been established with smooth operations as the pilot program has provided the infrastructure.

REDCap (www.project-redcap.org), a data collection tool used primarily in academic research settings, was selected to gather program evaluation data through patient questionnaires informed by the VHA measurement-based care initiative. Standard psychometrics were readily available in the VHA application and REDCap Mental Health Assistant includes the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9) Brief Symptom Inventory 18, Posttraumatic Checklist 5, Beck Scale for Suicidal Ideation, and Quality of Life Inventory. The Timberlawn Couple and Family Evaluation Scale (TCFES), which can be completed in 30 to 35 minutes and is a measure of overall function of relevant relationships, also may be added. Future studies are needed to confirm psychometrics of this scale in this setting, but the TCFES metric is widely used for similar purposes.

Nationwide, more than 950 patients have started treatment (ie, including active, completed, and discontinued treatment) and 412 veterans have completed the rTMS treatment. The goal of the program evaluation is to examine large scale rTMS efficacy in a large veteran population as well as determine predictors of individual patient response. Nationwide, PHQ-9 depression scores declined from a pretreatment average (SD) of 18.2 (5.5; range, 5-27) to a posttreatment average (SD) of 11.0 (7.1; range, 0-27). Patients also have indicated a high level of satisfaction with the treatment (Figure 4). Collecting data on a national level is a powerful way to examine rTMS efficacy and predictors of response that might be lost in a smaller subset of cases.

Implementation

It took 11 months for the VA contracting department to determine which machine to buy. However, the lengthy process assured that the equipment selected met all standards for clinical safety and efficacy. Furthermore, provision was made to allow for additional orders as new sites came online as well as upgrading the equipment for advances in technology.

The PNC set up several training programs to ensure proper use of this novel treatment. The education is ongoing and available as new sites are identified and initiated. The education includes, but is not limited to, in-person onsite and offsite training programs, online training modules that are available in the VA Electronic Educational Services (EES), and video telehealth consultations. Participants can view online lectures and then receive hands-on training as part of the educational program. Up to 3 HCPs for each site can receive funding to attend. Online programs also are available for new material to support continuing medical education. However, hands-on training is essential to understand how to obtain the motor threshold, which is used to determine the strength of the rTMS stimulus dose. Furthermore, hands-on training is essential for the proper localization of the stimulus, which is determined by certain anatomical landmarks. A phantom mannequin (ERIK [Evaluating Resting motor threshold and Insuring Kappa]) has been developed to assist in the hands-on learning.20

Relative Value Units

The VHA uses RVUs to properly account for workload and clinician activities. As a result, RVUs play an essential role as a currency that denotes the relative value of one type of clinical activity when compared with other activities. Depending on the treating specialty, clinicians generally use procedure codes outlined in the Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code set or the Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System (HCPCS) for medical billing. Most insurance carriers use RVUs set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) system as a standard system to determine HCP reimbursement for medical procedures.

The CPT codes associated with rTMS currently are 90867 to 90869. CMS had initially assigned a zero RVU to these CPT codes due to wide variations in the cost of performing rTMS. When we began implementing rTMS in the VHA, the lack of RVUs for rTMS rendered it impossible to show clinical workload for this activity using established VHA clinical accounting methods. The lack of RVUs assigned to rTMS CPT codes made justification for this treatment to clinical management difficult, which limited its clinical use in the VHA. In addition, HCPs who were using rTMS to treat severely ill veterans appeared artificially unproductive despite a significant patient workload. As we and VHA leadership became aware the program could not be staffed locally without getting workload credit for work done, the value was raised to 1.37 for treatment (90868) and 2.12 and 1.93 for evaluations (90867) and reevaluations (90869), respectively, thus reducing a potential roadblock to implementation.

Challenges as the Program Expands

Future challenges include upgrading machines to do intermittent θ burst stimulation (iTBS), which decreases the standard treatment time from 37.5 minutes to 3 minutes. Both patients and HCPs find iTBS to have similar tolerability to standard rTMS but in much less time. iTBS mimics endogenous θ rhythms and has been shown to be noninferior to rTMS for depression.21,22 Several devices have received FDA approval to treat MDD, including the Magstim and MagVenture TMS devices used in this program.

A major challenge for the VHA with rTMS will be to maintain a consistent level of competence and training. There is a need for continued maintenance of staff competence with ongoing training and training for new staff. Novel ways of training operators have been developed including ERIK.

Determining treatment interaction with other psychotherapies and pharmacotherapies is another challenge. Currently, rTMS is considered an adjunctive treatment added to the current patient treatment plan. We do not know yet how best to incorporate this somatic treatment with other approaches, and further research is necessary. A key issue is to determine which approach provides the best long-term results for a patient at risk for recurrence of depression. In addition, more research into maintaining healthy relationships for veterans with both MDD and PTSD is needed.

Many misconceptions exist about rTMS and HCPs need to be educated about the benefits of this modality. In addition, patients should understand the differences between rTMS and ECT. Even with newer approaches that streamline rTMS, the therapy remains costly in terms of direct costs as well as patient and HCP time.

Streamlining rTMS treatment remains an important concern. Compressing treatment schedules (ie, many treatments delivered to a patient in a single day) would allow the entire process to be delivered in days, not weeks. This would be especially advantageous to patients who live far from a treatment site. Performing multiple rTMS daily treatments is especially feasible with iTBS with its short treatment time.

Conclusions

rTMS is an emerging modality with both established and novel applications. The best studied application is treatment resistant MDD. Currently, rTMS has only been approved by the FDA for treatment of MDD. A pilot program was established by the VHA to distribute 30 rTMS machines sites nationwide. Results from data collected by these sites have shown patients improving on standard psychometric scales. Future changes include upgrading the machines to provide θ bursts, which has been shown to be faster and noninferior. Integrating rTMS with other pharmacotherapies and psychotherapies remains poorly understood and needs more research.

1. George MS, Wassermann EM, Williams WA, et al. Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves mood in depression. Neuroreport. 1995;6(14):1853‐1856. doi:10.1097/00001756-199510020-00008

2. Tik M, Hoffmann A, Sladky R, et al. Towards understanding rTMS mechanism of action: stimulation of the DLPFC causes network-specific increase in functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2017;162:289‐296. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.09.022

3. Perera T, George MS, Grammer G, Janicak PG, Pascual-Leone A, Wirecki TS. The Clinical TMS Society consensus review and treatment recommendations for TMS therapy for major depressive disorder. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(3):336‐346. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2016.03.010

4. George MS, Taylor JJ, Short EB. The expanding evidence base for rTMS treatment of depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(1):13‐18. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835ab46d

5. Lisanby SH, Husain MM, Rosenquist PB, et al. Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: clinical predictors of outcome in a multisite, randomized controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(2):522‐534. doi:10.1038/npp.2008.118

6. Yesavage JA, Fairchild JK, Mi Z, et al. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on treatment-resistant major depression in US veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):884‐893. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1483

7. O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1208‐1216. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018

8. Stilling JM, Monchi O, Amoozegar F, Debert CT. Transcranial magnetic and direct current stimulation (TMS/tDCS) for the treatment of headache: a systematic review. Headache. 2019;59(3):339‐357. doi:10.1111/head.13479

9. Lin Y, Jiang WJ, Shan PY, et al. The role of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2019;398:184‐191. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2019.01.038

10. Carmi L, Tendler A, Bystritsky A, et al. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(11):931‐938. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18101180

11. Song S, Zilverstand A, Gui W, Li HJ, Zhou X. Effects of single-session versus multi-session non-invasive brain stimulation on craving and consumption in individuals with drug addiction, eating disorders or obesity: a meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(3):606‐618. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2018.12.975

12. Wagner E, Wobrock T, Kunze B, et al. Efficacy of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in schizophrenia patients with treatment-resistant negative symptoms treated with clozapine. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:370‐376. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.021

13. Kozel FA, Van Trees K, Larson V, et al. One hertz versus ten hertz repetitive TMS treatment of PTSD: a randomized clinical trial. Psychiatry Res. 2019;273:153‐162. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.004

14. Coles AS, Kozak K, George TP. A review of brain stimulation methods to treat substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2018;27(2):71‐91. doi:10.1111/ajad.12674

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2019 National veteran suicide prevention annual report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf. Published September 19, 2019. Accessed May 18, 2020.

16. Ritchie EC. Improving Veteran engagement with mental health care. Fed Pract. 2017;34(8):55‐56.

17. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1231‐1242. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052963

18. Kozel FA, Hernandez M, Van Trees K, et al. Clinical repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for veterans with major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(4):242‐248.

19. National Health Policy Forum. The basics: relative value units (RVUs). https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/master/borndig/101513853/Relative%20Value%20Units.pdf. Published January 12, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2020.

20. Finetto C, Glusman C, Doolittle J, George MS. Presenting ERIK, the TMS phantom: a novel device for training and testing operators. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(4):1095‐1097. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2019.04.01521. Trevizol AP, Vigod SN, Daskalakis ZJ, Vila-Rodriguez F, Downar J, Blumberger DM. Intermittent theta burst stimulation for major depression during pregnancy. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(3):772‐774. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2019.01.003

22. Blumberger DM, Vila-Rodriguez F, Thorpe KE, et al. Effectiveness of theta burst versus high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression (THREE-D): a randomised non-inferiority trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2018 Jun 23;391(10139):e24]. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1683‐1692. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30295-2

1. George MS, Wassermann EM, Williams WA, et al. Daily repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) improves mood in depression. Neuroreport. 1995;6(14):1853‐1856. doi:10.1097/00001756-199510020-00008

2. Tik M, Hoffmann A, Sladky R, et al. Towards understanding rTMS mechanism of action: stimulation of the DLPFC causes network-specific increase in functional connectivity. Neuroimage. 2017;162:289‐296. doi:10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.09.022

3. Perera T, George MS, Grammer G, Janicak PG, Pascual-Leone A, Wirecki TS. The Clinical TMS Society consensus review and treatment recommendations for TMS therapy for major depressive disorder. Brain Stimul. 2016;9(3):336‐346. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2016.03.010

4. George MS, Taylor JJ, Short EB. The expanding evidence base for rTMS treatment of depression. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2013;26(1):13‐18. doi:10.1097/YCO.0b013e32835ab46d

5. Lisanby SH, Husain MM, Rosenquist PB, et al. Daily left prefrontal repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: clinical predictors of outcome in a multisite, randomized controlled clinical trial. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(2):522‐534. doi:10.1038/npp.2008.118

6. Yesavage JA, Fairchild JK, Mi Z, et al. Effect of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation on treatment-resistant major depression in US veterans: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(9):884‐893. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.1483

7. O’Reardon JP, Solvason HB, Janicak PG, et al. Efficacy and safety of transcranial magnetic stimulation in the acute treatment of major depression: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(11):1208‐1216. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.01.018

8. Stilling JM, Monchi O, Amoozegar F, Debert CT. Transcranial magnetic and direct current stimulation (TMS/tDCS) for the treatment of headache: a systematic review. Headache. 2019;59(3):339‐357. doi:10.1111/head.13479

9. Lin Y, Jiang WJ, Shan PY, et al. The role of repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS) in the treatment of cognitive impairment in patients with Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Neurol Sci. 2019;398:184‐191. doi:10.1016/j.jns.2019.01.038

10. Carmi L, Tendler A, Bystritsky A, et al. Efficacy and safety of deep transcranial magnetic stimulation for obsessive-compulsive disorder: a prospective multicenter randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2019;176(11):931‐938. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.18101180

11. Song S, Zilverstand A, Gui W, Li HJ, Zhou X. Effects of single-session versus multi-session non-invasive brain stimulation on craving and consumption in individuals with drug addiction, eating disorders or obesity: a meta-analysis. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(3):606‐618. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2018.12.975

12. Wagner E, Wobrock T, Kunze B, et al. Efficacy of high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in schizophrenia patients with treatment-resistant negative symptoms treated with clozapine. Schizophr Res. 2019;208:370‐376. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2019.01.021

13. Kozel FA, Van Trees K, Larson V, et al. One hertz versus ten hertz repetitive TMS treatment of PTSD: a randomized clinical trial. Psychiatry Res. 2019;273:153‐162. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2019.01.004

14. Coles AS, Kozak K, George TP. A review of brain stimulation methods to treat substance use disorders. Am J Addict. 2018;27(2):71‐91. doi:10.1111/ajad.12674

15. US Department of Veterans Affairs, Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention. 2019 National veteran suicide prevention annual report. https://www.mentalhealth.va.gov/docs/data-sheets/2019/2019_National_Veteran_Suicide_Prevention_Annual_Report_508.pdf. Published September 19, 2019. Accessed May 18, 2020.

16. Ritchie EC. Improving Veteran engagement with mental health care. Fed Pract. 2017;34(8):55‐56.

17. Rush AJ, Trivedi MH, Wisniewski SR, et al. Bupropion-SR, sertraline, or venlafaxine-XR after failure of SSRIs for depression. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(12):1231‐1242. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa052963

18. Kozel FA, Hernandez M, Van Trees K, et al. Clinical repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation for veterans with major depressive disorder. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29(4):242‐248.

19. National Health Policy Forum. The basics: relative value units (RVUs). https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/master/borndig/101513853/Relative%20Value%20Units.pdf. Published January 12, 2015. Accessed May 18, 2020.

20. Finetto C, Glusman C, Doolittle J, George MS. Presenting ERIK, the TMS phantom: a novel device for training and testing operators. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(4):1095‐1097. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2019.04.01521. Trevizol AP, Vigod SN, Daskalakis ZJ, Vila-Rodriguez F, Downar J, Blumberger DM. Intermittent theta burst stimulation for major depression during pregnancy. Brain Stimul. 2019;12(3):772‐774. doi:10.1016/j.brs.2019.01.003

22. Blumberger DM, Vila-Rodriguez F, Thorpe KE, et al. Effectiveness of theta burst versus high-frequency repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation in patients with depression (THREE-D): a randomised non-inferiority trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2018 Jun 23;391(10139):e24]. Lancet. 2018;391(10131):1683‐1692. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30295-2