User login

Carpal tunnel release is one of the most common hand surgeries performed at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS). Depending on surgeon experience and comfort level, surgeries are performed through either the traditional open method or the endoscopic method, single or double port (Figures 1 and 2). The advantage of the endoscopic method is faster recovery and return to work; however, the endoscopic method requires more expensive equipment and a steeper learning curve for surgeons. Complications are uncommon but can create unsatisfactory patient experiences because of costly lost workdays and long travel distances to the medical facility.

The purpose of this study was to compare the endoscopic method with the open carpal tunnel release method to determine whether there was an increased complication risk. Researchers anticipated that this information would help surgeons better inform patients of operative risks and prompt changes in NFSGVHS treatment plans to improve the quality of veteran care.

Methods

An Institutional Review Board- approved (#647-2011) retrospective review was done of patients who had carpal tunnel surgery performed by the NFSGVHS plastic surgery service from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2010. Surgeries included in the review took place at the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville and at the Lake City VAMC, both in Florida. Most of the surgeries included in the study were performed by a resident or fellow under the supervision of an attending physician. Eight different attending surgeons staffed the operations. Seven were board-certified or board-eligible plastic surgeons, 2 had advanced hand fellowship training, and 1 was a general surgeon with hand fellowship training. All hand fellowship-trained surgeons were in their first year of practice at the time of the study.

Only primary carpal tunnel releases were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included patients who were operated on by a service section other than the plastic surgery service (orthopedics or neurosurgery) and hands on which other procedures were performed during the same operation. Charts were reviewed for up to 1 year post surgery. Complications that required intervention were recorded. Researchers did not include pillar tenderness or an increase in occupational therapy visits as complications, due to the wide variety of patient tolerance to postoperative pain and varying motivation to return to work and daily routine.

Methods of release were endoscopic, open, or endoscopic converted to open. All but 6 of the completed endoscopic surgeries were performed using the double port Chow technique. The other 6 endoscopic surgeries were performed using the single port Agee technique at the distal wrist crease. There were 3 endoscopic converted to open cases that were performed using a single port, proximally-based technique in the midpalm. This method was abandoned after 3 unsuccessful endoscopic attempts, 1 resulting in digital nerve injury despite interactive cadaver labs prior to operative experience.

Endoscopic surgeries converted to open were recorded as open surgeries, because the patients had the full invasive experience. Researchers used the chi-square test and P value < .05 to compare the different methods of carpal tunnel release with identified complications.

Results and Complications

A total of 584 hands belonging to 452 patients were included in the study. Patients included 395 men and 57 women aged from 33 to 91 years. There were 271 endoscopic releases, 228 open releases, and 85 endoscopic converted to open releases. The NFSGVHS conversion rate was 23.7%. Complications in the converted cases (n = 4) were included in the open release results.

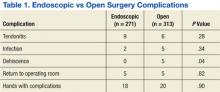

There were 40 complications in 38 hands. The overall complication rate was 6.5%. Complications noted were tendonitis presenting as De Quervain disease or trigger finger (9 endoscopic surgeries; 6 open surgeries), infection (2 endoscopic surgeries; 6 open surgeries), wound dehiscence (5 open surgeries), nerve injury (1 open surgery), respiratory distress (1 endoscopic), complex regional pain syndrome (1 open surgery), and scheduled returns to the operating room (OR) for recurrent, ongoing, or worsening symptoms (5 endoscopic surgeries; 5 open surgeries). Complications with an n > 1 were evaluated for statistical significance with P value < .05 (Table 1).

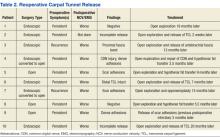

The NFSGVHS study had 10 patients return to the OR for open exploration (Table 2). Nine of these patients went back to the OR based on symptoms consistent with nerve conduction studies that had deteriorated compared with their preoperative studies. One endoscopic case was brought back to the OR for a suspected nerve injury without nerve conduction studies. Findings during reoperation included scar adhesions, incomplete release of ligaments, digital nerve injury, and negative explorations.

Two hypothenar fat transfers were performed to prevent scar adhesions in cases that had originally been open releases.1 Two of the open cases were endoscopic converted to open cases. One went back to the OR with a suspected nerve injury. Dense adhesions and an injured common digital nerve were identified and repaired. The second converted case that went back to the OR had a suspected, but unconfirmed, nerve injury to the motor branch. The diagnosis and treatment were delayed for more than a year due to the patient having other pressing medical and family concerns. An exploration found significant scar adhesions, and an opponensplasty was performed.

One patient had respiratory insufficiency secondary to chemical pneumonitis. The patient was sedated during an endoscopic carpal tunnel release, aspirated, and kept intubated in the intensive care unit until the morning after surgery.

An early complex regional pain syndrome diagnosis was made in a patient with underlying neuropathy and a preoperative “profound” median neuropathies diagnosis at the wrist with underlying peripheral neuropathy found on nerve conduction studies. The patient experienced an unusual amount of postoperative pain and edema after an uncomplicated open carpal tunnel release. This was treated with rapid intervention using anti- inflammatories and hand therapy. The patient also started a regimen of skin care, edema management, neuroreeducation, and contrast baths. Symptoms responded within a week.

There were 12 wound complications: 10 in open and 2 in endoscopic surgeries. Total wound complications were equally split between patients with and without diabetes. Infection and dehiscence were noted. Sutures were removed an average of 9.6 days after surgery in the patients whose wounds broke down. A statistically significant relationship was found only between the open method of release and wound dehiscence (P < .05).

There was no statistically significant difference in the overall complication rate in the NFSGVHS population when comparing endoscopic with open carpal tunnel release or when comparing the risk of postoperative tendonitis, wound infection, or return to the OR.

Discussion

Carpal tunnel syndrome was documented by James Paget in mid-19th century in reference to a distal radius fracture.2 It is the most common peripheral nerve compression, with an incidence ranging from 1 to 3 cases per 1,000 subjects per year and a prevalence of 50 cases per 1,000 subjects per year.3 In an active-duty U.S. military population, the incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome is 3.98 per 1,000 person years.4

Related: Risk Factors for Postoperative Complications in Trigger Finger Release

The endoscopic method of release was first introduced in 1989 by Okutsu and colleagues.5 About 500,000 carpal tunnel releases are now performed in the U.S. every year, with 50,000 performed endoscopically.3 There were 185 carpal tunnel releases (56 endoscopic and 129 open) performed at the NFSGVHS in 2012.6 The minimally invasive procedure was designed to preserve the overlying skin and fascia, promoting an earlier return to work and daily activities. This is particularly relevant for manual workers who desire rapid return of grip strength. Multiple published reports have found more rapid recovery based on a reduction in scar tenderness, increase in grip strength, or return to work.7-13 Patients seem to have equivalent results over the long term, ranging from 3 months to 1 year.7,8,13-15 Return to work was not evaluated in this study, because many patients were either retired or not working steadily.

The endoscopic method was criticized after its introduction due to its potential increase in major structural injury to the median nerve, ulnar nerve, palmar arch, ulnar artery, or flexor tendons.16 A meta-analysis found improved outcomes but a statistically significant higher complication rate in endoscopic, compared with open release (2.2% in endoscopic vs 1.2% in open).16 Referral patterns have found iatrogenic nerve injury in patients referred by surgeons without formal hand fellowship training.17 There is a wide variety of background training for surgeons who may offer carpal tunnel release, including plastic surgery, orthopedics, general surgery, and neurosurgery.

Major structural injuries were reported by hand surgeons using both open and endoscopic methods in a questionnaire sent to members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, indicating that either approach demands respect.18 A large review of the literature from 1966 to 2001 by Benson and colleagues found that the endoscopic approach was not more likely to produce injury to tendons, arteries, or nerves compared with the open approach and actually had a lower rate of structural damage (0.49% vs 0.19%).19 Researchers who conducted this study confirmed one common digital nerve injury in an endoscopic converted to open technique, using a distally-based port with the blade not being deployed via the endoscopic method. The endoscopic method has been found to have a higher rate of reversible nerve injury (neuropraxia) compared with the open technique.7,10,19

The NFSGVHS results found a higher rate of wound dehiscence. More frequent wound site complications, particularly infection, hypertrophic scar, and scar tenderness have been noted using the open method.3,8,20 This is probably due to the deeper and slightly larger incision used for the open method compared with the smaller and shallower incisions used for the endoscopic release.

There is the inevitable learning curve for the endoscopic release due to the more complicated nature of the procedure. The NFSGVHS conversion rate was 23.7% over the 5-year period from 2005 to 2010. All 3 fellowship- trained hand surgeons were in their first year of practice at the time of the study, so the authors anticipate a lower conversion rate in forthcoming studies. The NFSGVHS researchers did not consider converting to an open technique to be a complication and believe it is appropriate to teach plastic surgery residents and fellows to have a low threshold to convert when visualization is not optimal and the potential for significant injury exists. The learning curve and a higher conversion rate have been acknowledged by Beck and colleagues with no increase in morbidity.21

The authors anticipated finding an increased rate of tendonitis in the endoscopic method, as found by Goshtasby and colleagues, where trigger finger was found more frequently in the endoscopic patients.22 The NFSGVHS study found that the number of patients presenting for steroid injections to treat postoperative tendonitis in the hand and wrist was not statistically significant when comparing the 2 surgical methods of release (3.3% in endoscopic vs 1.9% in open; P = .28).

The NFSGVHS rate of return to the OR within a year of surgery was 1.7%. The researchers from NFSGHVS anticipated a higher rate of return to the OR for ongoing symptoms secondary to incomplete release of the transverse carpal ligament. Published studies have found an intact retinaculum to be a cause of persistent symptoms when smaller incisions are used.23,24 Five endoscopic cases and 5 open cases eventually returned to the OR for carpal tunnel exploration. Two of the patients were classified as recurrent, because they had improvement of symptoms initially but presented > 6 months later with new symptoms. Eight of the patients were classified as persistent, because they did not have an extended period of relief of preoperative symptoms (Table 2).25 There was no statistically significant difference in return to the OR in the 2 study groups. The NFSGVHS researchers did note a trend in more incomplete nerve releases in the endoscopic group and more scar adhesions as the etiology of symptoms in the open group who went back to surgery.

Published studies have found no difference in overall complication rates when comparing the open with the endoscopic method of release, which is consistent with NFSGVHS data.8,11,12,26

A limitation of the current retrospective study is the large number of providers who both operated on the patients and documented their postoperative findings. The strength of the study is that VA patients tend to stay within the VISN for their health care so postoperative problems will be identified and routed to the plastic surgery service for evaluation and treatment.

Clinical implications for the NFSGVHS practice are that surgeons can confidently offer both the open and endoscopic surgeries without an overall risk of increased complications to patients. Patients who are identified as higher risk for wound dehiscence, such as those who place an unusual amount of pressure on their palms due to assisted walking devices or are at a higher risk of falling onto the surgical site, will be steered toward an endoscopic surgery. The NFSGVHS began a splinting protocol in the early postoperative period that was not previously used on those select patients who have open carpal tunnel releases.

Conclusion

Wound dehiscence was the only statistically significant complication found in the NFSGVHS veteran population when comparing open with endoscopic carpal tunnel release. This can potentially be prevented in future patients by delaying the removal of sutures and prolonging the use of a protective dressing in patients who undergo open release. There was not a statistically significant increase in overall complications when using the minimally invasive method of release, which is consistent with existing literature.

Acknowledgement

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VAMC.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Chrysopoulo MT, Greenberg JA, Kleinman WB. The hypothenar fat pad transposition flap: a modified surgical technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2006;10(3):150-156.

2. Paget J. Lectures on Surgical Pathology Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. London, England: Longman, Green, Brown, and Longmans; 1853.

3. Mintalucci DJ, Leinberry CF Jr. Open versus endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43(4):431-437.

4. Wolf JM, Mountcastle S, Owens BD. Incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in the US military population. Hand (NY). 2009;4(3):289-293.

5. Okutsu I, Ninomiya S, Takatori Y, Ugawa Y. Endoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(1):11-18.

6. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture Database, Ambulatory Surgical Case Load Report, 2012. Accessed March 14, 2013.

7. Larsen MB, Sørensen AI, Crone KL, Weis T, Boeckstyns ME. Carpal tunnel release: a randomized comparison of three surgical methods. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(6):646-650.

8. Malhotra R, Kiran EK, Dua A, Mallinath SG, Bhan S. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release: a short-term comparative study. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(1):57-61.

9. Sabesan VJ, Pedrotty D, Urbaniak JR, Aldridge JM 3rd. An evidence-based review of a single surgeon’s experience with endoscopic carpal tunnel release. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2012;21(3):117-121.

10. Thoma A, Veltri K, Haines T, Duku E. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing endoscopic and open carpal tunnel decompression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(5):1137-1146.

11. Tian Y, Zhao H, Wang T. Prospective comparison of endoscopic and open surgical methods for carpal tunnel syndrome. Chin Med Sci J. 2007;22(2):104-107.

12. Trumble TE, Diao E, Abrams RA, Gilbert-Anderson MM. Single-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release compared with open release: a prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(7):1107-1115.

13. Vasiliadis HS, Xenakis TA, Mitsionis G, Paschos N, Georgoulis A. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2010:26(1):26-33.

14. Macdermid JC, Richards RS, Roth JH, Ross DC, King GJ. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release: a randomized trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(3):475-480.

15. Aslani HR, Alizadeh K, Eajazi A, et al. Comparison of carpal tunnel release with three different techniques. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114(7):965-968.

16. Kohanzadeh S, Herrera FA, Dobke M. Outcomes of open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a meta-analysis. Hand (NY). 2012;7(3):247-251.

17. Azari KK, Spiess AM, Buterbaugh GA, Imbriglia JE. Major nerve injuries associated with carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(6):1977-1978.

18. Palmer AK, Toivonen DA. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(3):561-565.

19. Benson LS, Bare AA, Nagle DJ, Harder VS, Williams CS, Visotsky JL. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):919-924, 924.e1-e2.

20. Gerritsen AA, Uitdehaag BM, van Geldere D, Scholten RJ, de Vet HC, Bouter LM. Systematic review of randomized clinical trials of surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Br J Surg. 2001;88(10):1285-1295.

21. Beck JD, Deegan JH, Rhoades D, Klena JC. Results of endoscopic carpal tunnel release relative to surgeon experience with the Agee technique. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(1):61-64.

22. Goshtasby PH, Wheeler DR, Moy OJ. Risk factors for trigger finger occurrence after carpal tunnel release. Hand Surg. 2010;15(2):81-87.

23. Assmus H, Dombert T, Staub F. Reoperations for CTS because of recurrence or for correction [article in German]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):306-311.

24. Frik A, Baumeister RG. Re-intervention after carpal tunnel release [article in German]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):312-316.

25. Jones NF, Ahn HC, Eo S. Revision surgery for persistent and recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome and for failed carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(3):683-692.

26. Ferdinand RD, MacLean JG. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release in bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. A prospective, randomised, blinded assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002:84(3):375-379.

Carpal tunnel release is one of the most common hand surgeries performed at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS). Depending on surgeon experience and comfort level, surgeries are performed through either the traditional open method or the endoscopic method, single or double port (Figures 1 and 2). The advantage of the endoscopic method is faster recovery and return to work; however, the endoscopic method requires more expensive equipment and a steeper learning curve for surgeons. Complications are uncommon but can create unsatisfactory patient experiences because of costly lost workdays and long travel distances to the medical facility.

The purpose of this study was to compare the endoscopic method with the open carpal tunnel release method to determine whether there was an increased complication risk. Researchers anticipated that this information would help surgeons better inform patients of operative risks and prompt changes in NFSGVHS treatment plans to improve the quality of veteran care.

Methods

An Institutional Review Board- approved (#647-2011) retrospective review was done of patients who had carpal tunnel surgery performed by the NFSGVHS plastic surgery service from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2010. Surgeries included in the review took place at the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville and at the Lake City VAMC, both in Florida. Most of the surgeries included in the study were performed by a resident or fellow under the supervision of an attending physician. Eight different attending surgeons staffed the operations. Seven were board-certified or board-eligible plastic surgeons, 2 had advanced hand fellowship training, and 1 was a general surgeon with hand fellowship training. All hand fellowship-trained surgeons were in their first year of practice at the time of the study.

Only primary carpal tunnel releases were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included patients who were operated on by a service section other than the plastic surgery service (orthopedics or neurosurgery) and hands on which other procedures were performed during the same operation. Charts were reviewed for up to 1 year post surgery. Complications that required intervention were recorded. Researchers did not include pillar tenderness or an increase in occupational therapy visits as complications, due to the wide variety of patient tolerance to postoperative pain and varying motivation to return to work and daily routine.

Methods of release were endoscopic, open, or endoscopic converted to open. All but 6 of the completed endoscopic surgeries were performed using the double port Chow technique. The other 6 endoscopic surgeries were performed using the single port Agee technique at the distal wrist crease. There were 3 endoscopic converted to open cases that were performed using a single port, proximally-based technique in the midpalm. This method was abandoned after 3 unsuccessful endoscopic attempts, 1 resulting in digital nerve injury despite interactive cadaver labs prior to operative experience.

Endoscopic surgeries converted to open were recorded as open surgeries, because the patients had the full invasive experience. Researchers used the chi-square test and P value < .05 to compare the different methods of carpal tunnel release with identified complications.

Results and Complications

A total of 584 hands belonging to 452 patients were included in the study. Patients included 395 men and 57 women aged from 33 to 91 years. There were 271 endoscopic releases, 228 open releases, and 85 endoscopic converted to open releases. The NFSGVHS conversion rate was 23.7%. Complications in the converted cases (n = 4) were included in the open release results.

There were 40 complications in 38 hands. The overall complication rate was 6.5%. Complications noted were tendonitis presenting as De Quervain disease or trigger finger (9 endoscopic surgeries; 6 open surgeries), infection (2 endoscopic surgeries; 6 open surgeries), wound dehiscence (5 open surgeries), nerve injury (1 open surgery), respiratory distress (1 endoscopic), complex regional pain syndrome (1 open surgery), and scheduled returns to the operating room (OR) for recurrent, ongoing, or worsening symptoms (5 endoscopic surgeries; 5 open surgeries). Complications with an n > 1 were evaluated for statistical significance with P value < .05 (Table 1).

The NFSGVHS study had 10 patients return to the OR for open exploration (Table 2). Nine of these patients went back to the OR based on symptoms consistent with nerve conduction studies that had deteriorated compared with their preoperative studies. One endoscopic case was brought back to the OR for a suspected nerve injury without nerve conduction studies. Findings during reoperation included scar adhesions, incomplete release of ligaments, digital nerve injury, and negative explorations.

Two hypothenar fat transfers were performed to prevent scar adhesions in cases that had originally been open releases.1 Two of the open cases were endoscopic converted to open cases. One went back to the OR with a suspected nerve injury. Dense adhesions and an injured common digital nerve were identified and repaired. The second converted case that went back to the OR had a suspected, but unconfirmed, nerve injury to the motor branch. The diagnosis and treatment were delayed for more than a year due to the patient having other pressing medical and family concerns. An exploration found significant scar adhesions, and an opponensplasty was performed.

One patient had respiratory insufficiency secondary to chemical pneumonitis. The patient was sedated during an endoscopic carpal tunnel release, aspirated, and kept intubated in the intensive care unit until the morning after surgery.

An early complex regional pain syndrome diagnosis was made in a patient with underlying neuropathy and a preoperative “profound” median neuropathies diagnosis at the wrist with underlying peripheral neuropathy found on nerve conduction studies. The patient experienced an unusual amount of postoperative pain and edema after an uncomplicated open carpal tunnel release. This was treated with rapid intervention using anti- inflammatories and hand therapy. The patient also started a regimen of skin care, edema management, neuroreeducation, and contrast baths. Symptoms responded within a week.

There were 12 wound complications: 10 in open and 2 in endoscopic surgeries. Total wound complications were equally split between patients with and without diabetes. Infection and dehiscence were noted. Sutures were removed an average of 9.6 days after surgery in the patients whose wounds broke down. A statistically significant relationship was found only between the open method of release and wound dehiscence (P < .05).

There was no statistically significant difference in the overall complication rate in the NFSGVHS population when comparing endoscopic with open carpal tunnel release or when comparing the risk of postoperative tendonitis, wound infection, or return to the OR.

Discussion

Carpal tunnel syndrome was documented by James Paget in mid-19th century in reference to a distal radius fracture.2 It is the most common peripheral nerve compression, with an incidence ranging from 1 to 3 cases per 1,000 subjects per year and a prevalence of 50 cases per 1,000 subjects per year.3 In an active-duty U.S. military population, the incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome is 3.98 per 1,000 person years.4

Related: Risk Factors for Postoperative Complications in Trigger Finger Release

The endoscopic method of release was first introduced in 1989 by Okutsu and colleagues.5 About 500,000 carpal tunnel releases are now performed in the U.S. every year, with 50,000 performed endoscopically.3 There were 185 carpal tunnel releases (56 endoscopic and 129 open) performed at the NFSGVHS in 2012.6 The minimally invasive procedure was designed to preserve the overlying skin and fascia, promoting an earlier return to work and daily activities. This is particularly relevant for manual workers who desire rapid return of grip strength. Multiple published reports have found more rapid recovery based on a reduction in scar tenderness, increase in grip strength, or return to work.7-13 Patients seem to have equivalent results over the long term, ranging from 3 months to 1 year.7,8,13-15 Return to work was not evaluated in this study, because many patients were either retired or not working steadily.

The endoscopic method was criticized after its introduction due to its potential increase in major structural injury to the median nerve, ulnar nerve, palmar arch, ulnar artery, or flexor tendons.16 A meta-analysis found improved outcomes but a statistically significant higher complication rate in endoscopic, compared with open release (2.2% in endoscopic vs 1.2% in open).16 Referral patterns have found iatrogenic nerve injury in patients referred by surgeons without formal hand fellowship training.17 There is a wide variety of background training for surgeons who may offer carpal tunnel release, including plastic surgery, orthopedics, general surgery, and neurosurgery.

Major structural injuries were reported by hand surgeons using both open and endoscopic methods in a questionnaire sent to members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, indicating that either approach demands respect.18 A large review of the literature from 1966 to 2001 by Benson and colleagues found that the endoscopic approach was not more likely to produce injury to tendons, arteries, or nerves compared with the open approach and actually had a lower rate of structural damage (0.49% vs 0.19%).19 Researchers who conducted this study confirmed one common digital nerve injury in an endoscopic converted to open technique, using a distally-based port with the blade not being deployed via the endoscopic method. The endoscopic method has been found to have a higher rate of reversible nerve injury (neuropraxia) compared with the open technique.7,10,19

The NFSGVHS results found a higher rate of wound dehiscence. More frequent wound site complications, particularly infection, hypertrophic scar, and scar tenderness have been noted using the open method.3,8,20 This is probably due to the deeper and slightly larger incision used for the open method compared with the smaller and shallower incisions used for the endoscopic release.

There is the inevitable learning curve for the endoscopic release due to the more complicated nature of the procedure. The NFSGVHS conversion rate was 23.7% over the 5-year period from 2005 to 2010. All 3 fellowship- trained hand surgeons were in their first year of practice at the time of the study, so the authors anticipate a lower conversion rate in forthcoming studies. The NFSGVHS researchers did not consider converting to an open technique to be a complication and believe it is appropriate to teach plastic surgery residents and fellows to have a low threshold to convert when visualization is not optimal and the potential for significant injury exists. The learning curve and a higher conversion rate have been acknowledged by Beck and colleagues with no increase in morbidity.21

The authors anticipated finding an increased rate of tendonitis in the endoscopic method, as found by Goshtasby and colleagues, where trigger finger was found more frequently in the endoscopic patients.22 The NFSGVHS study found that the number of patients presenting for steroid injections to treat postoperative tendonitis in the hand and wrist was not statistically significant when comparing the 2 surgical methods of release (3.3% in endoscopic vs 1.9% in open; P = .28).

The NFSGVHS rate of return to the OR within a year of surgery was 1.7%. The researchers from NFSGHVS anticipated a higher rate of return to the OR for ongoing symptoms secondary to incomplete release of the transverse carpal ligament. Published studies have found an intact retinaculum to be a cause of persistent symptoms when smaller incisions are used.23,24 Five endoscopic cases and 5 open cases eventually returned to the OR for carpal tunnel exploration. Two of the patients were classified as recurrent, because they had improvement of symptoms initially but presented > 6 months later with new symptoms. Eight of the patients were classified as persistent, because they did not have an extended period of relief of preoperative symptoms (Table 2).25 There was no statistically significant difference in return to the OR in the 2 study groups. The NFSGVHS researchers did note a trend in more incomplete nerve releases in the endoscopic group and more scar adhesions as the etiology of symptoms in the open group who went back to surgery.

Published studies have found no difference in overall complication rates when comparing the open with the endoscopic method of release, which is consistent with NFSGVHS data.8,11,12,26

A limitation of the current retrospective study is the large number of providers who both operated on the patients and documented their postoperative findings. The strength of the study is that VA patients tend to stay within the VISN for their health care so postoperative problems will be identified and routed to the plastic surgery service for evaluation and treatment.

Clinical implications for the NFSGVHS practice are that surgeons can confidently offer both the open and endoscopic surgeries without an overall risk of increased complications to patients. Patients who are identified as higher risk for wound dehiscence, such as those who place an unusual amount of pressure on their palms due to assisted walking devices or are at a higher risk of falling onto the surgical site, will be steered toward an endoscopic surgery. The NFSGVHS began a splinting protocol in the early postoperative period that was not previously used on those select patients who have open carpal tunnel releases.

Conclusion

Wound dehiscence was the only statistically significant complication found in the NFSGVHS veteran population when comparing open with endoscopic carpal tunnel release. This can potentially be prevented in future patients by delaying the removal of sutures and prolonging the use of a protective dressing in patients who undergo open release. There was not a statistically significant increase in overall complications when using the minimally invasive method of release, which is consistent with existing literature.

Acknowledgement

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VAMC.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Carpal tunnel release is one of the most common hand surgeries performed at the North Florida/South Georgia Veterans Health System (NFSGVHS). Depending on surgeon experience and comfort level, surgeries are performed through either the traditional open method or the endoscopic method, single or double port (Figures 1 and 2). The advantage of the endoscopic method is faster recovery and return to work; however, the endoscopic method requires more expensive equipment and a steeper learning curve for surgeons. Complications are uncommon but can create unsatisfactory patient experiences because of costly lost workdays and long travel distances to the medical facility.

The purpose of this study was to compare the endoscopic method with the open carpal tunnel release method to determine whether there was an increased complication risk. Researchers anticipated that this information would help surgeons better inform patients of operative risks and prompt changes in NFSGVHS treatment plans to improve the quality of veteran care.

Methods

An Institutional Review Board- approved (#647-2011) retrospective review was done of patients who had carpal tunnel surgery performed by the NFSGVHS plastic surgery service from January 1, 2005, to December 31, 2010. Surgeries included in the review took place at the Malcom Randall VAMC in Gainesville and at the Lake City VAMC, both in Florida. Most of the surgeries included in the study were performed by a resident or fellow under the supervision of an attending physician. Eight different attending surgeons staffed the operations. Seven were board-certified or board-eligible plastic surgeons, 2 had advanced hand fellowship training, and 1 was a general surgeon with hand fellowship training. All hand fellowship-trained surgeons were in their first year of practice at the time of the study.

Only primary carpal tunnel releases were included in the study. Exclusion criteria included patients who were operated on by a service section other than the plastic surgery service (orthopedics or neurosurgery) and hands on which other procedures were performed during the same operation. Charts were reviewed for up to 1 year post surgery. Complications that required intervention were recorded. Researchers did not include pillar tenderness or an increase in occupational therapy visits as complications, due to the wide variety of patient tolerance to postoperative pain and varying motivation to return to work and daily routine.

Methods of release were endoscopic, open, or endoscopic converted to open. All but 6 of the completed endoscopic surgeries were performed using the double port Chow technique. The other 6 endoscopic surgeries were performed using the single port Agee technique at the distal wrist crease. There were 3 endoscopic converted to open cases that were performed using a single port, proximally-based technique in the midpalm. This method was abandoned after 3 unsuccessful endoscopic attempts, 1 resulting in digital nerve injury despite interactive cadaver labs prior to operative experience.

Endoscopic surgeries converted to open were recorded as open surgeries, because the patients had the full invasive experience. Researchers used the chi-square test and P value < .05 to compare the different methods of carpal tunnel release with identified complications.

Results and Complications

A total of 584 hands belonging to 452 patients were included in the study. Patients included 395 men and 57 women aged from 33 to 91 years. There were 271 endoscopic releases, 228 open releases, and 85 endoscopic converted to open releases. The NFSGVHS conversion rate was 23.7%. Complications in the converted cases (n = 4) were included in the open release results.

There were 40 complications in 38 hands. The overall complication rate was 6.5%. Complications noted were tendonitis presenting as De Quervain disease or trigger finger (9 endoscopic surgeries; 6 open surgeries), infection (2 endoscopic surgeries; 6 open surgeries), wound dehiscence (5 open surgeries), nerve injury (1 open surgery), respiratory distress (1 endoscopic), complex regional pain syndrome (1 open surgery), and scheduled returns to the operating room (OR) for recurrent, ongoing, or worsening symptoms (5 endoscopic surgeries; 5 open surgeries). Complications with an n > 1 were evaluated for statistical significance with P value < .05 (Table 1).

The NFSGVHS study had 10 patients return to the OR for open exploration (Table 2). Nine of these patients went back to the OR based on symptoms consistent with nerve conduction studies that had deteriorated compared with their preoperative studies. One endoscopic case was brought back to the OR for a suspected nerve injury without nerve conduction studies. Findings during reoperation included scar adhesions, incomplete release of ligaments, digital nerve injury, and negative explorations.

Two hypothenar fat transfers were performed to prevent scar adhesions in cases that had originally been open releases.1 Two of the open cases were endoscopic converted to open cases. One went back to the OR with a suspected nerve injury. Dense adhesions and an injured common digital nerve were identified and repaired. The second converted case that went back to the OR had a suspected, but unconfirmed, nerve injury to the motor branch. The diagnosis and treatment were delayed for more than a year due to the patient having other pressing medical and family concerns. An exploration found significant scar adhesions, and an opponensplasty was performed.

One patient had respiratory insufficiency secondary to chemical pneumonitis. The patient was sedated during an endoscopic carpal tunnel release, aspirated, and kept intubated in the intensive care unit until the morning after surgery.

An early complex regional pain syndrome diagnosis was made in a patient with underlying neuropathy and a preoperative “profound” median neuropathies diagnosis at the wrist with underlying peripheral neuropathy found on nerve conduction studies. The patient experienced an unusual amount of postoperative pain and edema after an uncomplicated open carpal tunnel release. This was treated with rapid intervention using anti- inflammatories and hand therapy. The patient also started a regimen of skin care, edema management, neuroreeducation, and contrast baths. Symptoms responded within a week.

There were 12 wound complications: 10 in open and 2 in endoscopic surgeries. Total wound complications were equally split between patients with and without diabetes. Infection and dehiscence were noted. Sutures were removed an average of 9.6 days after surgery in the patients whose wounds broke down. A statistically significant relationship was found only between the open method of release and wound dehiscence (P < .05).

There was no statistically significant difference in the overall complication rate in the NFSGVHS population when comparing endoscopic with open carpal tunnel release or when comparing the risk of postoperative tendonitis, wound infection, or return to the OR.

Discussion

Carpal tunnel syndrome was documented by James Paget in mid-19th century in reference to a distal radius fracture.2 It is the most common peripheral nerve compression, with an incidence ranging from 1 to 3 cases per 1,000 subjects per year and a prevalence of 50 cases per 1,000 subjects per year.3 In an active-duty U.S. military population, the incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome is 3.98 per 1,000 person years.4

Related: Risk Factors for Postoperative Complications in Trigger Finger Release

The endoscopic method of release was first introduced in 1989 by Okutsu and colleagues.5 About 500,000 carpal tunnel releases are now performed in the U.S. every year, with 50,000 performed endoscopically.3 There were 185 carpal tunnel releases (56 endoscopic and 129 open) performed at the NFSGVHS in 2012.6 The minimally invasive procedure was designed to preserve the overlying skin and fascia, promoting an earlier return to work and daily activities. This is particularly relevant for manual workers who desire rapid return of grip strength. Multiple published reports have found more rapid recovery based on a reduction in scar tenderness, increase in grip strength, or return to work.7-13 Patients seem to have equivalent results over the long term, ranging from 3 months to 1 year.7,8,13-15 Return to work was not evaluated in this study, because many patients were either retired or not working steadily.

The endoscopic method was criticized after its introduction due to its potential increase in major structural injury to the median nerve, ulnar nerve, palmar arch, ulnar artery, or flexor tendons.16 A meta-analysis found improved outcomes but a statistically significant higher complication rate in endoscopic, compared with open release (2.2% in endoscopic vs 1.2% in open).16 Referral patterns have found iatrogenic nerve injury in patients referred by surgeons without formal hand fellowship training.17 There is a wide variety of background training for surgeons who may offer carpal tunnel release, including plastic surgery, orthopedics, general surgery, and neurosurgery.

Major structural injuries were reported by hand surgeons using both open and endoscopic methods in a questionnaire sent to members of the American Society for Surgery of the Hand, indicating that either approach demands respect.18 A large review of the literature from 1966 to 2001 by Benson and colleagues found that the endoscopic approach was not more likely to produce injury to tendons, arteries, or nerves compared with the open approach and actually had a lower rate of structural damage (0.49% vs 0.19%).19 Researchers who conducted this study confirmed one common digital nerve injury in an endoscopic converted to open technique, using a distally-based port with the blade not being deployed via the endoscopic method. The endoscopic method has been found to have a higher rate of reversible nerve injury (neuropraxia) compared with the open technique.7,10,19

The NFSGVHS results found a higher rate of wound dehiscence. More frequent wound site complications, particularly infection, hypertrophic scar, and scar tenderness have been noted using the open method.3,8,20 This is probably due to the deeper and slightly larger incision used for the open method compared with the smaller and shallower incisions used for the endoscopic release.

There is the inevitable learning curve for the endoscopic release due to the more complicated nature of the procedure. The NFSGVHS conversion rate was 23.7% over the 5-year period from 2005 to 2010. All 3 fellowship- trained hand surgeons were in their first year of practice at the time of the study, so the authors anticipate a lower conversion rate in forthcoming studies. The NFSGVHS researchers did not consider converting to an open technique to be a complication and believe it is appropriate to teach plastic surgery residents and fellows to have a low threshold to convert when visualization is not optimal and the potential for significant injury exists. The learning curve and a higher conversion rate have been acknowledged by Beck and colleagues with no increase in morbidity.21

The authors anticipated finding an increased rate of tendonitis in the endoscopic method, as found by Goshtasby and colleagues, where trigger finger was found more frequently in the endoscopic patients.22 The NFSGVHS study found that the number of patients presenting for steroid injections to treat postoperative tendonitis in the hand and wrist was not statistically significant when comparing the 2 surgical methods of release (3.3% in endoscopic vs 1.9% in open; P = .28).

The NFSGVHS rate of return to the OR within a year of surgery was 1.7%. The researchers from NFSGHVS anticipated a higher rate of return to the OR for ongoing symptoms secondary to incomplete release of the transverse carpal ligament. Published studies have found an intact retinaculum to be a cause of persistent symptoms when smaller incisions are used.23,24 Five endoscopic cases and 5 open cases eventually returned to the OR for carpal tunnel exploration. Two of the patients were classified as recurrent, because they had improvement of symptoms initially but presented > 6 months later with new symptoms. Eight of the patients were classified as persistent, because they did not have an extended period of relief of preoperative symptoms (Table 2).25 There was no statistically significant difference in return to the OR in the 2 study groups. The NFSGVHS researchers did note a trend in more incomplete nerve releases in the endoscopic group and more scar adhesions as the etiology of symptoms in the open group who went back to surgery.

Published studies have found no difference in overall complication rates when comparing the open with the endoscopic method of release, which is consistent with NFSGVHS data.8,11,12,26

A limitation of the current retrospective study is the large number of providers who both operated on the patients and documented their postoperative findings. The strength of the study is that VA patients tend to stay within the VISN for their health care so postoperative problems will be identified and routed to the plastic surgery service for evaluation and treatment.

Clinical implications for the NFSGVHS practice are that surgeons can confidently offer both the open and endoscopic surgeries without an overall risk of increased complications to patients. Patients who are identified as higher risk for wound dehiscence, such as those who place an unusual amount of pressure on their palms due to assisted walking devices or are at a higher risk of falling onto the surgical site, will be steered toward an endoscopic surgery. The NFSGVHS began a splinting protocol in the early postoperative period that was not previously used on those select patients who have open carpal tunnel releases.

Conclusion

Wound dehiscence was the only statistically significant complication found in the NFSGVHS veteran population when comparing open with endoscopic carpal tunnel release. This can potentially be prevented in future patients by delaying the removal of sutures and prolonging the use of a protective dressing in patients who undergo open release. There was not a statistically significant increase in overall complications when using the minimally invasive method of release, which is consistent with existing literature.

Acknowledgement

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the Malcom Randall VAMC.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

1. Chrysopoulo MT, Greenberg JA, Kleinman WB. The hypothenar fat pad transposition flap: a modified surgical technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2006;10(3):150-156.

2. Paget J. Lectures on Surgical Pathology Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. London, England: Longman, Green, Brown, and Longmans; 1853.

3. Mintalucci DJ, Leinberry CF Jr. Open versus endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43(4):431-437.

4. Wolf JM, Mountcastle S, Owens BD. Incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in the US military population. Hand (NY). 2009;4(3):289-293.

5. Okutsu I, Ninomiya S, Takatori Y, Ugawa Y. Endoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(1):11-18.

6. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture Database, Ambulatory Surgical Case Load Report, 2012. Accessed March 14, 2013.

7. Larsen MB, Sørensen AI, Crone KL, Weis T, Boeckstyns ME. Carpal tunnel release: a randomized comparison of three surgical methods. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(6):646-650.

8. Malhotra R, Kiran EK, Dua A, Mallinath SG, Bhan S. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release: a short-term comparative study. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(1):57-61.

9. Sabesan VJ, Pedrotty D, Urbaniak JR, Aldridge JM 3rd. An evidence-based review of a single surgeon’s experience with endoscopic carpal tunnel release. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2012;21(3):117-121.

10. Thoma A, Veltri K, Haines T, Duku E. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing endoscopic and open carpal tunnel decompression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(5):1137-1146.

11. Tian Y, Zhao H, Wang T. Prospective comparison of endoscopic and open surgical methods for carpal tunnel syndrome. Chin Med Sci J. 2007;22(2):104-107.

12. Trumble TE, Diao E, Abrams RA, Gilbert-Anderson MM. Single-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release compared with open release: a prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(7):1107-1115.

13. Vasiliadis HS, Xenakis TA, Mitsionis G, Paschos N, Georgoulis A. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2010:26(1):26-33.

14. Macdermid JC, Richards RS, Roth JH, Ross DC, King GJ. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release: a randomized trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(3):475-480.

15. Aslani HR, Alizadeh K, Eajazi A, et al. Comparison of carpal tunnel release with three different techniques. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114(7):965-968.

16. Kohanzadeh S, Herrera FA, Dobke M. Outcomes of open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a meta-analysis. Hand (NY). 2012;7(3):247-251.

17. Azari KK, Spiess AM, Buterbaugh GA, Imbriglia JE. Major nerve injuries associated with carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(6):1977-1978.

18. Palmer AK, Toivonen DA. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(3):561-565.

19. Benson LS, Bare AA, Nagle DJ, Harder VS, Williams CS, Visotsky JL. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):919-924, 924.e1-e2.

20. Gerritsen AA, Uitdehaag BM, van Geldere D, Scholten RJ, de Vet HC, Bouter LM. Systematic review of randomized clinical trials of surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Br J Surg. 2001;88(10):1285-1295.

21. Beck JD, Deegan JH, Rhoades D, Klena JC. Results of endoscopic carpal tunnel release relative to surgeon experience with the Agee technique. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(1):61-64.

22. Goshtasby PH, Wheeler DR, Moy OJ. Risk factors for trigger finger occurrence after carpal tunnel release. Hand Surg. 2010;15(2):81-87.

23. Assmus H, Dombert T, Staub F. Reoperations for CTS because of recurrence or for correction [article in German]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):306-311.

24. Frik A, Baumeister RG. Re-intervention after carpal tunnel release [article in German]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):312-316.

25. Jones NF, Ahn HC, Eo S. Revision surgery for persistent and recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome and for failed carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(3):683-692.

26. Ferdinand RD, MacLean JG. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release in bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. A prospective, randomised, blinded assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002:84(3):375-379.

1. Chrysopoulo MT, Greenberg JA, Kleinman WB. The hypothenar fat pad transposition flap: a modified surgical technique. Tech Hand Up Extrem Surg. 2006;10(3):150-156.

2. Paget J. Lectures on Surgical Pathology Delivered at the Royal College of Surgeons of England. London, England: Longman, Green, Brown, and Longmans; 1853.

3. Mintalucci DJ, Leinberry CF Jr. Open versus endoscopic carpal tunnel release. Orthop Clin North Am. 2012;43(4):431-437.

4. Wolf JM, Mountcastle S, Owens BD. Incidence of carpal tunnel syndrome in the US military population. Hand (NY). 2009;4(3):289-293.

5. Okutsu I, Ninomiya S, Takatori Y, Ugawa Y. Endoscopic management of carpal tunnel syndrome. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(1):11-18.

6. U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs. Health Information Systems and Technology Architecture Database, Ambulatory Surgical Case Load Report, 2012. Accessed March 14, 2013.

7. Larsen MB, Sørensen AI, Crone KL, Weis T, Boeckstyns ME. Carpal tunnel release: a randomized comparison of three surgical methods. J Hand Surg Eur Vol. 2013;38(6):646-650.

8. Malhotra R, Kiran EK, Dua A, Mallinath SG, Bhan S. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release: a short-term comparative study. Indian J Orthop. 2007;41(1):57-61.

9. Sabesan VJ, Pedrotty D, Urbaniak JR, Aldridge JM 3rd. An evidence-based review of a single surgeon’s experience with endoscopic carpal tunnel release. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2012;21(3):117-121.

10. Thoma A, Veltri K, Haines T, Duku E. A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials comparing endoscopic and open carpal tunnel decompression. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;114(5):1137-1146.

11. Tian Y, Zhao H, Wang T. Prospective comparison of endoscopic and open surgical methods for carpal tunnel syndrome. Chin Med Sci J. 2007;22(2):104-107.

12. Trumble TE, Diao E, Abrams RA, Gilbert-Anderson MM. Single-portal endoscopic carpal tunnel release compared with open release: a prospective, randomized trial. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A(7):1107-1115.

13. Vasiliadis HS, Xenakis TA, Mitsionis G, Paschos N, Georgoulis A. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2010:26(1):26-33.

14. Macdermid JC, Richards RS, Roth JH, Ross DC, King GJ. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release: a randomized trial. J Hand Surg Am. 2003;28(3):475-480.

15. Aslani HR, Alizadeh K, Eajazi A, et al. Comparison of carpal tunnel release with three different techniques. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2012;114(7):965-968.

16. Kohanzadeh S, Herrera FA, Dobke M. Outcomes of open and endoscopic carpal tunnel release: a meta-analysis. Hand (NY). 2012;7(3):247-251.

17. Azari KK, Spiess AM, Buterbaugh GA, Imbriglia JE. Major nerve injuries associated with carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;119(6):1977-1978.

18. Palmer AK, Toivonen DA. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. J Hand Surg Am. 1999;24(3):561-565.

19. Benson LS, Bare AA, Nagle DJ, Harder VS, Williams CS, Visotsky JL. Complications of endoscopic and open carpal tunnel release. Arthroscopy. 2006;22(9):919-924, 924.e1-e2.

20. Gerritsen AA, Uitdehaag BM, van Geldere D, Scholten RJ, de Vet HC, Bouter LM. Systematic review of randomized clinical trials of surgical treatment for carpal tunnel syndrome. Br J Surg. 2001;88(10):1285-1295.

21. Beck JD, Deegan JH, Rhoades D, Klena JC. Results of endoscopic carpal tunnel release relative to surgeon experience with the Agee technique. J Hand Surg Am. 2011;36(1):61-64.

22. Goshtasby PH, Wheeler DR, Moy OJ. Risk factors for trigger finger occurrence after carpal tunnel release. Hand Surg. 2010;15(2):81-87.

23. Assmus H, Dombert T, Staub F. Reoperations for CTS because of recurrence or for correction [article in German]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):306-311.

24. Frik A, Baumeister RG. Re-intervention after carpal tunnel release [article in German]. Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2006;38(5):312-316.

25. Jones NF, Ahn HC, Eo S. Revision surgery for persistent and recurrent carpal tunnel syndrome and for failed carpal tunnel release. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129(3):683-692.

26. Ferdinand RD, MacLean JG. Endoscopic versus open carpal tunnel release in bilateral carpal tunnel syndrome. A prospective, randomised, blinded assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002:84(3):375-379.