User login

In the past 10 years, artificial intelligence (AI) applications have exploded in numerous fields, including medicine. Myriad publications report that the use of AI in health care is increasing, and AI has shown utility in many medical specialties, eg, pathology, radiology, and oncology.1,2

In cancer pathology, AI was able not only to detect various cancers, but also to subtype and grade them. In addition, AI could predict survival, the success of therapeutic response, and underlying mutations from histopathologic images.3 In other medical fields, AI applications are as notable. For example, in imaging specialties like radiology, ophthalmology, dermatology, and gastroenterology, AI is being used for image recognition, enhancement, and segmentation. In addition, AI is beneficial for predicting disease progression, survival, and response to therapy in other medical specialties. Finally, AI may help with administrative tasks like scheduling.

However, many obstacles to successfully implementing AI programs in the clinical setting exist, including clinical data limitations and ethical use of data, trust in the AI models, regulatory barriers, and lack of clinical buy-in due to insufficient basic AI understanding.2 To address these barriers to successful clinical AI implementation, we decided to create a formal governing body at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida. Accordingly, the hospital AI committee charter was officially approved on July 22, 2021. Our model could be used by both US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and non-VA hospitals throughout the country.

AI Committee

The vision of the AI committee is to improve outcomes and experiences for our veterans by developing trustworthy AI capabilities to support the VA mission. The mission is to build robust capacity in AI to create and apply innovative AI solutions and transform the VA by facilitating a learning environment that supports the delivery of world-class benefits and services to our veterans. Our vision and mission are aligned with the VA National AI Institute. 4

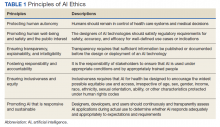

The AI Committee comprises 7 subcommittees: ethics, AI clinical product evaluation, education, data sharing and acquisition, research, 3D printing, and improvement and innovation. The role of the ethics subcommittee is to ensure the ethical and equitable implementation of clinical AI. We created the ethics subcommittee guidelines based on the World Health Organization ethics and governance of AI for health documents.5 They include 6 basic principles: protecting human autonomy; promoting human well-being and safety and the public interest; ensuring transparency, explainability, and intelligibility; fostering responsibility and accountability; ensuring inclusiveness and equity; and promoting AI that is responsive and sustainable (Table 1).

As the name indicates, the role of the AI clinical product evaluation subcommittee is to evaluate commercially available clinical AI products. More than 400 US Food and Drug Administration–approved AI medical applications exist, and the list is growing rapidly. Most AI applications are in medical imaging like radiology, dermatology, ophthalmology, and pathology.6,7 Each clinical product is evaluated according to 6 principles: relevance, usability, risks, regulatory, technical requirements, and financial (Table 2).8 We are in the process of evaluating a few commercial AI algorithms for pathology and radiology, using these 6 principles.

Implementations

After a comprehensive evaluation, we implemented 2 ClearRead (Riverain Technologies) AI radiology solutions. ClearRead CT Vessel Suppress produces a secondary series of computed tomography (CT) images, suppressing vessels and other normal structures within the lungs to improve nodule detectability, and ClearRead Xray Bone Suppress, which increases the visibility of soft tissue in standard chest X-rays by suppressing the bone on the digital image without the need for 2 exposures.

The role of the education subcommittee is to educate the staff about AI and how it can improve patient care. Every Friday, we email an AI article of the week to our practitioners. In addition, we publish a newsletter, and we organize an annual AI conference. The first conference in 2022 included speakers from the National AI Institute, Moffitt Cancer Center, the University of South Florida, and our facility.

As the name indicates, the data sharing and acquisition subcommittee oversees preparing data for our clinical and research projects. The role of the research subcommittee is to coordinate and promote AI research with the ultimate goal of improving patient care.

Other Technologies

Although 3D printing does not fall under the umbrella of AI, we have decided to include it in our future-oriented AI committee. We created an online 3D printing course to promote the technology throughout the VA. We 3D print organ models to help surgeons prepare for complicated operations. In addition, together with our colleagues from the University of Florida, we used 3D printing to address the shortage of swabs for COVID-19 testing. The VA Sunshine Healthcare Network (Veterans Integrated Services Network 8) has an active Innovation and Improvement Committee. 9 Our improvement and innovation subcommittee serves as a coordinating body with the network committee .

Conclusions

Through the hospital AI committee, we believe that we may overcome many obstacles to successfully implementing AI applications in the clinical setting, including the ethical use of data, trust in the AI models, regulatory barriers, and lack of clinical buy-in due to insufficient basic AI knowledge.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

In the past 10 years, artificial intelligence (AI) applications have exploded in numerous fields, including medicine. Myriad publications report that the use of AI in health care is increasing, and AI has shown utility in many medical specialties, eg, pathology, radiology, and oncology.1,2

In cancer pathology, AI was able not only to detect various cancers, but also to subtype and grade them. In addition, AI could predict survival, the success of therapeutic response, and underlying mutations from histopathologic images.3 In other medical fields, AI applications are as notable. For example, in imaging specialties like radiology, ophthalmology, dermatology, and gastroenterology, AI is being used for image recognition, enhancement, and segmentation. In addition, AI is beneficial for predicting disease progression, survival, and response to therapy in other medical specialties. Finally, AI may help with administrative tasks like scheduling.

However, many obstacles to successfully implementing AI programs in the clinical setting exist, including clinical data limitations and ethical use of data, trust in the AI models, regulatory barriers, and lack of clinical buy-in due to insufficient basic AI understanding.2 To address these barriers to successful clinical AI implementation, we decided to create a formal governing body at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida. Accordingly, the hospital AI committee charter was officially approved on July 22, 2021. Our model could be used by both US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and non-VA hospitals throughout the country.

AI Committee

The vision of the AI committee is to improve outcomes and experiences for our veterans by developing trustworthy AI capabilities to support the VA mission. The mission is to build robust capacity in AI to create and apply innovative AI solutions and transform the VA by facilitating a learning environment that supports the delivery of world-class benefits and services to our veterans. Our vision and mission are aligned with the VA National AI Institute. 4

The AI Committee comprises 7 subcommittees: ethics, AI clinical product evaluation, education, data sharing and acquisition, research, 3D printing, and improvement and innovation. The role of the ethics subcommittee is to ensure the ethical and equitable implementation of clinical AI. We created the ethics subcommittee guidelines based on the World Health Organization ethics and governance of AI for health documents.5 They include 6 basic principles: protecting human autonomy; promoting human well-being and safety and the public interest; ensuring transparency, explainability, and intelligibility; fostering responsibility and accountability; ensuring inclusiveness and equity; and promoting AI that is responsive and sustainable (Table 1).

As the name indicates, the role of the AI clinical product evaluation subcommittee is to evaluate commercially available clinical AI products. More than 400 US Food and Drug Administration–approved AI medical applications exist, and the list is growing rapidly. Most AI applications are in medical imaging like radiology, dermatology, ophthalmology, and pathology.6,7 Each clinical product is evaluated according to 6 principles: relevance, usability, risks, regulatory, technical requirements, and financial (Table 2).8 We are in the process of evaluating a few commercial AI algorithms for pathology and radiology, using these 6 principles.

Implementations

After a comprehensive evaluation, we implemented 2 ClearRead (Riverain Technologies) AI radiology solutions. ClearRead CT Vessel Suppress produces a secondary series of computed tomography (CT) images, suppressing vessels and other normal structures within the lungs to improve nodule detectability, and ClearRead Xray Bone Suppress, which increases the visibility of soft tissue in standard chest X-rays by suppressing the bone on the digital image without the need for 2 exposures.

The role of the education subcommittee is to educate the staff about AI and how it can improve patient care. Every Friday, we email an AI article of the week to our practitioners. In addition, we publish a newsletter, and we organize an annual AI conference. The first conference in 2022 included speakers from the National AI Institute, Moffitt Cancer Center, the University of South Florida, and our facility.

As the name indicates, the data sharing and acquisition subcommittee oversees preparing data for our clinical and research projects. The role of the research subcommittee is to coordinate and promote AI research with the ultimate goal of improving patient care.

Other Technologies

Although 3D printing does not fall under the umbrella of AI, we have decided to include it in our future-oriented AI committee. We created an online 3D printing course to promote the technology throughout the VA. We 3D print organ models to help surgeons prepare for complicated operations. In addition, together with our colleagues from the University of Florida, we used 3D printing to address the shortage of swabs for COVID-19 testing. The VA Sunshine Healthcare Network (Veterans Integrated Services Network 8) has an active Innovation and Improvement Committee. 9 Our improvement and innovation subcommittee serves as a coordinating body with the network committee .

Conclusions

Through the hospital AI committee, we believe that we may overcome many obstacles to successfully implementing AI applications in the clinical setting, including the ethical use of data, trust in the AI models, regulatory barriers, and lack of clinical buy-in due to insufficient basic AI knowledge.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.

In the past 10 years, artificial intelligence (AI) applications have exploded in numerous fields, including medicine. Myriad publications report that the use of AI in health care is increasing, and AI has shown utility in many medical specialties, eg, pathology, radiology, and oncology.1,2

In cancer pathology, AI was able not only to detect various cancers, but also to subtype and grade them. In addition, AI could predict survival, the success of therapeutic response, and underlying mutations from histopathologic images.3 In other medical fields, AI applications are as notable. For example, in imaging specialties like radiology, ophthalmology, dermatology, and gastroenterology, AI is being used for image recognition, enhancement, and segmentation. In addition, AI is beneficial for predicting disease progression, survival, and response to therapy in other medical specialties. Finally, AI may help with administrative tasks like scheduling.

However, many obstacles to successfully implementing AI programs in the clinical setting exist, including clinical data limitations and ethical use of data, trust in the AI models, regulatory barriers, and lack of clinical buy-in due to insufficient basic AI understanding.2 To address these barriers to successful clinical AI implementation, we decided to create a formal governing body at James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital in Tampa, Florida. Accordingly, the hospital AI committee charter was officially approved on July 22, 2021. Our model could be used by both US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) and non-VA hospitals throughout the country.

AI Committee

The vision of the AI committee is to improve outcomes and experiences for our veterans by developing trustworthy AI capabilities to support the VA mission. The mission is to build robust capacity in AI to create and apply innovative AI solutions and transform the VA by facilitating a learning environment that supports the delivery of world-class benefits and services to our veterans. Our vision and mission are aligned with the VA National AI Institute. 4

The AI Committee comprises 7 subcommittees: ethics, AI clinical product evaluation, education, data sharing and acquisition, research, 3D printing, and improvement and innovation. The role of the ethics subcommittee is to ensure the ethical and equitable implementation of clinical AI. We created the ethics subcommittee guidelines based on the World Health Organization ethics and governance of AI for health documents.5 They include 6 basic principles: protecting human autonomy; promoting human well-being and safety and the public interest; ensuring transparency, explainability, and intelligibility; fostering responsibility and accountability; ensuring inclusiveness and equity; and promoting AI that is responsive and sustainable (Table 1).

As the name indicates, the role of the AI clinical product evaluation subcommittee is to evaluate commercially available clinical AI products. More than 400 US Food and Drug Administration–approved AI medical applications exist, and the list is growing rapidly. Most AI applications are in medical imaging like radiology, dermatology, ophthalmology, and pathology.6,7 Each clinical product is evaluated according to 6 principles: relevance, usability, risks, regulatory, technical requirements, and financial (Table 2).8 We are in the process of evaluating a few commercial AI algorithms for pathology and radiology, using these 6 principles.

Implementations

After a comprehensive evaluation, we implemented 2 ClearRead (Riverain Technologies) AI radiology solutions. ClearRead CT Vessel Suppress produces a secondary series of computed tomography (CT) images, suppressing vessels and other normal structures within the lungs to improve nodule detectability, and ClearRead Xray Bone Suppress, which increases the visibility of soft tissue in standard chest X-rays by suppressing the bone on the digital image without the need for 2 exposures.

The role of the education subcommittee is to educate the staff about AI and how it can improve patient care. Every Friday, we email an AI article of the week to our practitioners. In addition, we publish a newsletter, and we organize an annual AI conference. The first conference in 2022 included speakers from the National AI Institute, Moffitt Cancer Center, the University of South Florida, and our facility.

As the name indicates, the data sharing and acquisition subcommittee oversees preparing data for our clinical and research projects. The role of the research subcommittee is to coordinate and promote AI research with the ultimate goal of improving patient care.

Other Technologies

Although 3D printing does not fall under the umbrella of AI, we have decided to include it in our future-oriented AI committee. We created an online 3D printing course to promote the technology throughout the VA. We 3D print organ models to help surgeons prepare for complicated operations. In addition, together with our colleagues from the University of Florida, we used 3D printing to address the shortage of swabs for COVID-19 testing. The VA Sunshine Healthcare Network (Veterans Integrated Services Network 8) has an active Innovation and Improvement Committee. 9 Our improvement and innovation subcommittee serves as a coordinating body with the network committee .

Conclusions

Through the hospital AI committee, we believe that we may overcome many obstacles to successfully implementing AI applications in the clinical setting, including the ethical use of data, trust in the AI models, regulatory barriers, and lack of clinical buy-in due to insufficient basic AI knowledge.

Acknowledgments

This material is the result of work supported with resources and the use of facilities at the James A. Haley Veterans’ Hospital.