User login

Premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) are a common cause of palpitations, and are also often detected incidentally on electrocardiography (ECG), ambulatory monitoring, or inpatient telemetry. At the cellular level, ventricular myocytes spontaneously depolarize to create an extra systole that is “out of sync” with the cardiac cycle.

Although nearly everyone has some PVCs from time to time, people vary widely in their frequency of PVCs and their sensitivity to them.1,2 Some patients are exquisitely sensitive to even a small number of PVCs, while others are completely unaware of PVCs in a bigeminal pattern (ie, every other heartbeat). This article will review the evaluation and management of PVCs with a focus on clinical aspects.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Personal and family history

Symptoms. The initial history should establish the presence, extent, timing, and duration of symptoms. Patients may use the word “palpitations” to describe their symptoms, but they also describe them as “hard” heartbeats, “chest-thumping,” or as a “catch” or “skipped” heartbeat. Related symptoms may include difficulty breathing, chest pain, fatigue, and dizziness.

The interview should determine whether the symptoms represent a minor nuisance or a major quality-of-life issue to the patient, and whether there are any specific associations or triggers. For example, it is very common for patients to become aware of PVCs at night, particularly in certain positions, such as lying on the left side. Patients often associate PVC symptoms with emotional stress, exercise, or caffeine or stimulant use.

Medication use. An accurate and up-to-date list of prescription medications should be screened for alpha-, beta-, or dopamine-receptor agonist drugs. Similarly, any use of over-the-counter sympathomimetic medications and nonprescription supplements should be elicited, including compounded elixirs or beverages. Many commercially available products designed to treat fatigue or increase alertness contain large doses of caffeine or other stimulants. It is also important to consider the use of illicit substances such as cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and their derivatives.

The patient’s medical and surgical history should be queried for any known structural heart disease, including coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, and heritable conditions such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, prolonged QT syndromes, or other channel disorders. Pulmonary disorders such as sarcoidosis, pulmonary hypertension, or obstructive sleep apnea are also relevant. Similarly, it is important to identify endocrine disorders, including thyroid problems, sex hormone abnormalities, or adrenal gland conditions.

A careful family history should include any instance of sudden death in first-degree relatives, any heritable cardiac conditions, or coronary artery disease at an early age.

Physical examination

The physical examination should focus on findings that suggest underlying structural heart disease. Findings suggestive of congestive heart failure include elevated jugular venous pressures, abnormal cardiac sounds, pulmonary rales, abnormal arterial pulses, or peripheral edema. A murmur or a pathologic heart sound should raise suspicion of valvular or congenital heart disease when present in a young patient.

Inspection and palpation of the thyroid can reveal a related disorder. Obvious skin changes or neurologic findings can similarly reveal a systemic and possibly related clinical disorder that can have cardiac manifestations (eg, muscular dystrophy).

Electrocardiography, Holter monitoring, and other monitoring

Assessment of the cardiac rhythm includes 12-lead ECG and ambulatory Holter monitoring, typically for 24 or 48 hours.

Holter monitoring provides a continuous recording, usually in at least two or three leads. Patients are given a symptom journal or are asked to keep a diary of symptoms experienced during the monitoring period. The monitor is worn underneath clothing and is returned for download upon completion. Technicians process the data with the aid of computer software, and the final output is reviewed and interpreted by a cardiologist or cardiac electrophysiologist.

Holter monitoring for at least 24 hours is a critical step in assessing any patient with known or suspected PVCs, as it can both quantify the total burden of ventricular ectopy and identify the presence of any related ventricular tachycardia. In addition, it can detect additional supraventricular arrhythmias or bradycardia during the monitoring period. The PVC burden is an important measurement; it is expressed as the percentage of heartbeats that were ventricular extrasystoles during the monitoring period.

Both ECG and Holter monitoring are limited in that they are only snapshots of the rhythm during the period when a patient is actually hooked up. Many patients experience PVCs in clusters every very few days or weeks. Such a pattern is unlikely to be detected by a single ECG or 24- or 48-hour Holter monitoring.

A 30-day ambulatory event monitor (also known as a wearable loop recorder) is an important diagnostic tool in these scenarios. The concept is very similar to that of Holter monitoring, except that the device provides a continuous loop recording of the cardiac rhythm that is digitally stored in clips when the patient activates the device. Some wearable loop recorders also have auto-save features for heart rates falling outside of a programmed range.

Mobile outpatient cardiac telemetry is the most comprehensive form of noninvasive rhythm monitoring available. This is essentially the equivalent of continuous inpatient cardiac telemetry, but in a patient who is not hospitalized. It is a wearable ambulatory device providing continuous recordings, real-time automatic detections, and patient-activated symptom recordings. It can be used for up to 6 weeks. Advantages include detection and quantification of asymptomatic events, and real-time transmissions that the physician can act upon. The major disadvantage is cost, including coverage denial by many third-party payers.

This test is rarely indicated as part of a PVC evaluation and is typically ordered only by a cardiologist or cardiac electrophysiologist.

Noninvasive cardiac evaluation

Surface echocardiography is indicated to look for overt structural heart disease and can reliably detect abnormalities in cardiac chamber size, wall thickness, and function. Valvular heart disease is concomitantly identified by two-dimensional imaging as well as by color Doppler. The finding of significant structural heart disease in conjunction with PVCs should prompt a cardiology referral, as this carries significant prognostic implications.3–5

Exercise treadmill stress testing is appropriate for patients who experience PVCs with exercise or for whom an evaluation for coronary artery disease is indicated. The expected finding would be an increase in PVCs or ventricular tachycardia with exercise or in the subsequent recovery period. Exercise testing can be combined with either echocardiographic or nuclear perfusion imaging to evaluate the possibility of myocardial ischemia. For patients unable to exercise, pharmacologic stress testing with dobutamine or a vasodilator agent can be performed.

Advanced noninvasive cardiac imaging— such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron-emission tomography—should be reserved for specific clinical indications such as congenital heart disease, suspected cardiac sarcoidosis, and infiltrative heart disease, and for specific cardiomyopathies, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. For example, frequent PVCs with a left bundle branch block morphology and superior axis raise the concern for a right ventricular disorder and may prompt cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for either arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy or sarcoidosis.

PVCs WITHOUT STRUCTURAL HEART DISEASE

Outflow tract PVCs and ventricular tachycardia

The right or left ventricular outflow tracts, or the epicardial tissue immediately adjacent to the aortic sinuses of Valsalva are the most common sites of origin for ventricular ectopy in the absence of structural heart disease.6–9 Affected cells often demonstrate a triggered activity mechanism due to cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated and calcium-dependent delayed after-depolarizations.7,8

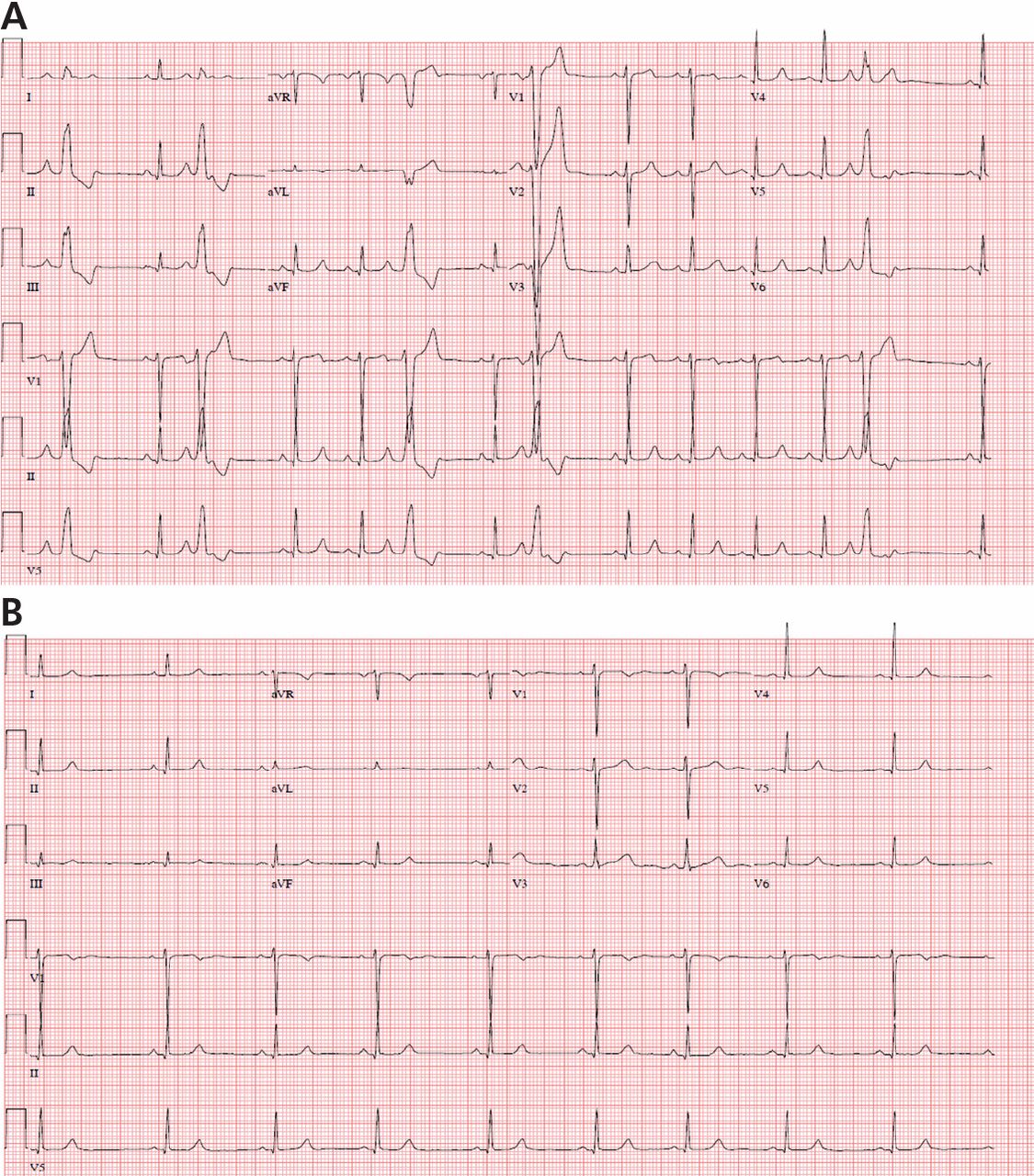

Most of these foci are in the right ventricular outflow tract, producing a left bundle branch block morphology with an inferior axis (positive R waves in limb leads II, III, and aVF) and typical precordial R-wave transition in V3 and V4 (Figure 1). A minority are in the left ventricular outflow tract, producing a right bundle branch block with an inferior axis pattern, or in the aortic sinuses with a left bundle branch block pattern but with early precordial R transition in V2 and V3.

A study in 122 patients showed that right and left outflow tract arrhythmias had similar electrophysiologic properties and pharmacologic sensitivities, providing evidence for shared mechanisms possibly due to the common embryologic origin of these structures.9

Such arrhythmias are typically catecholamine-sensitive and are sometimes inducible with burst pacing in the electrophysiology laboratory. The short ventricular coupling intervals can promote intracellular calcium overload in the affected cells, leading to triggered activity.

Therefore, outflow tract PVCs and ventricular tachycardia are commonly encountered clinically during exercise and, to an even greater extent, in the postexercise cool-down period. Similarly, they can be worse during periods of emotional stress or fatigue, when the body’s endogenous catecholamine production is elevated. However, it is worthwhile to note that there are exceptions to this principle in which faster sinus rates seem to overdrive the PVCs in some patients, causing them to become paradoxically more frequent at rest, or even during sleep.

Outflow tract PVCs can be managed medically with beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil or diltiazem), or, less commonly, class IC drugs such as flecainide. They are also highly curable by catheter ablation (Figure 2), with procedure success rates greater than 90%.9.10

However, a subset of outflow tract PVCs nested deep in a triangle of epicardial tissue between the right and left endocardial surface and underneath the left main coronary artery can be challenging. This region has been labeled the left ventricular summit, and is shielded from ablation by an epicardial fat pad in the adjacent pericardial space.11 Ablation attempts made from the right and left endocardial surfaces as well as the epicardial surface (pericardial space) sometimes cannot adequately penetrate the tissue deep enough to reach the originating focus deep within this triangle. While ablation cannot always fully eliminate the PVC, ablation from more than one of the sites listed can generally reduce its burden, often in combination with suppressive medical therapy (Figure 3).

Fascicular PVCs

Fascicular PVCs originate from within the left ventricular His-Purkinje system12 and produce a right bundle branch block morphology with either an anterior or posterior hemiblock pattern (Figure 4). Exit from the posterior fascicle causes an anterior hemiblock pattern, and exit from the anterior fascicle a posterior hemiblock pattern. Utilization of the rapidly conducting His-Purkinje system gives these PVCs a very narrow QRS duration, sometimes approaching 120 milliseconds or shorter. This occasionally causes them to be mistaken for aberrantly conducted supraventricular beats. Such spontaneous PVCs are commonly associated with both sustained and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and are usually sensitive to verapamil.13

Special issues relating to mapping and catheter ablation of fascicular arrhythmias involve the identification of Purkinje fiber potentials and associated procedural diagnostic maneuvers during tachycardia.14

Other sites for PVCs

Other sites of origin for PVCs in the absence of structural heart disease include ventricular tissue adjacent to the aortomitral continuity,15 the tricuspid annulus,16 the mitral valve annulus, 17 papillary muscles,18 and other Purkinje-adjacent structures such as left ventricular false tendons.19 An example of a papillary muscle PVC is shown in Figures 5 and 6.

Curable by catheter ablation

Any of these PVCs can potentially be cured by catheter ablation when present at a sufficient burden to allow for activation mapping in the electrophysiology laboratory. The threshold for offering ablation varies among operators, but is generally around 10% or greater. Pacemapping is a technique applied in the electrophysiology laboratory when medically refractory symptomatic PVCs occurring at a lower burden require ablation.

PVCs WITH AN UNDERLYING CARDIAC CONDITION

Coronary artery disease

Tissue injury and death caused by acute myocardial infarction has long been recognized as a common cause of spontaneous ventricular ectopy attributed to infarct border zones of ischemic or hibernating myocardium.20,21

Suppression has not been associated with improved outcomes, as shown for class IC drugs in the landmark Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST),22 or in the amiodarone treatment arm of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT-II).23 Therefore, treatment of ventricular ectopy in this patient population is usually symptom-driven unless there is hemodynamic intolerance, tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy, or a very high burden of PVCs in a patient who may be at risk of developing tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy. Antiarrhythmic drug treatment, when required, usually involves beta-blockers or class III medications such as sotalol or amiodarone.

Nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy

This category includes patients with a wide variety of disease states including valvular heart disease, lymphocytic and other viral myocarditis, cardiac sarcoidosis, amyloidosis and other infiltrative diseases, familial conditions, and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (ie, etiology unknown). Although it is a heterogeneous group, a common theme is that PVCs in this patient cohort may require epicardial mapping and ablation.24 Similarly, epicardial PVCs and ventricular tachycardia cluster at the basal posterolateral left ventricle near the mitral annulus, for unclear reasons.25

While specific criteria have been published, an epicardial focus is suggested by slowing of the initial QRS segment, pseudo-delta waves, a wider overall QRS, and Q waves in limb lead I.26

Treatment is symptom-driven unless the patient has a tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy or a high burden associated with the risk for its development. Antiarrhythmic drug therapy, when required, typically involves a beta-blocker or a class III drug such as sotalol or amiodarone. Sotalol is used in this population but has limited safety data and should be used cautiously in patients without an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

Spontaneous ventricular ectopy and tachycardia are common, if not expected, in patients with this heritable autosomal dominant disorder. This condition is progressive and associated with the risk of sudden cardiac death. Criteria for diagnosis were established in 2010, and patients with suspected arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy often undergo cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.27 Diagnostic findings include fibro-fatty tissue replacement, which usually starts in the right ventricle but can progress to involve the left ventricle. PVCs and ventricular tachycardia can involve the right ventricular free wall and are often epicardial.

Catheter ablation is usually palliative, as future arrhythmias are expected. Many patients with this condition require an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for prevention of sudden cardiac death, and some go on to cardiac transplantation as the disease progresses and ventricular arrhythmias become incessant.

Other conditions

Spontaneous ventricular ectopy is common in other heritable and acquired cardiomyopathies including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and in infiltrative or inflammatory disorders such as cardiac amyloidosis and sarcoidosis. While technically falling under the rubric of nonischemic heart disease, the presence of spontaneous ventricular ectopy carries specific prognostic implications depending on the underlying diagnosis. Therefore, an appropriate referral for complete cardiac evaluation should be considered when a heritable disorder or other acquired structural heart disease is suspected.

TACHYCARDIA-RELATED CARDIOMYOPATHY

Tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy refers to left ventricular systolic dysfunction that is primarily caused by arrhythmias. This includes frequent PVCs or ventricular tachycardia but also atrial arrhythmias occurring at a high burden that directly weaken myocardial function over time. Although much research has been devoted to this condition, our understanding of its etiology and pathology is incomplete.

PVCs and ventricular ectopy burdens in excess of 15% to 20% have been associated with the development of this condition.28,29 However, it is important to note that cardiomyopathy can also develop at lower burdens.30 One study found that a burden greater than 24% was 79% sensitive and 78% specific for development of tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy.31 Additional studies have demonstrated specific PVC morphologic features such as slurring in the initial QRS segment and also PVCs occurring at shorter coupling intervals as being associated with cardiomyopathy.32–34

For these reasons, both quantification of the total burden and careful evaluation of available electrocardiograms and rhythm strips are important even in asymptomatic patients with frequent PVCs. Similarly, unexplained left ventricular dysfunction in patients with PVC burdens in these discussed ranges should raise suspicion for this diagnosis. Patients with tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy usually have at least partially reversible left ventricular dysfunction when identified or treated early.29,35

MEDICAL AND ABLATIVE TREATMENT

Available treatments include medical suppression and catheter ablation. One needs to exercise clinical judgment and incorporate all of the PVC-related data to make treatment decisions.

Little data for trigger avoidance and behavioral modification

Some patients report a strong association between palpitations related to PVCs and caffeine intake, other stimulants, or other dietary triggers. However, few data exist to support the role of trigger avoidance and behavioral modification in treatment. In fact, an older randomized trial in 81 men found no benefit in a program of total abstinence from caffeine and smoking, moderation of alcohol intake, and physical conditioning.36

Nonetheless, some argue in favor of advising patients to make these dietary and lifestyle changes, given the overall health benefits of aggressive risk-factor modification for cardiovascular disease.37 Certainly, a trial of trigger avoidance and behavioral modification seems reasonable for patients who have strongly associated historical triggers in the absence of structural heart disease and PVCs occurring at a low to modest burden.

Beta-blockers are the mainstay

Beta-blockers are the mainstay of medical suppression of PVCs, primarily through their effect on beta-1 adrenergic receptors to reduce intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate and thus decrease automaticity. Blocking beta-1 receptors also causes a negative chronotropic effect, reducing the resting sinus rate in addition to slowing atrioventricular nodal conduction.

Cardioselective beta-blockers include atenolol, betaxolol, metoprolol, and nadolol. These drugs are effective in suppressing PVCs, or at least in reducing the burden to more tolerable levels.

Beta-blockers are most strongly indicated in patients who require PVC suppression and who have concomitant coronary artery disease, prior myocardial infarction, or other cardiomyopathy, as this drug class favorably affects long-term prognosis in these conditions.

Common side effects of beta-blockers include fatigue, shortness of breath, depressed mood, and loss of libido. Side effects can present a significant challenge, particularly for younger patients. Noncardioselective beta-blockers are less commonly prescribed, with the exception of propranolol, which is an effective sympatholytic drug that blocks both beta-1 and beta-2 receptors.

Many patients with asthma or peripheral arterial disease can tolerate these drugs well despite concerns about provoked bronchospasm or claudication, respectively, and neither of these conditions is considered an absolute contraindication. Excessive bradycardia with beta-blocker therapy can lead to dizziness, lightheadedness, or overt syncope, and these drugs should be used with caution in patients with baseline sinus node dysfunction or atrioventricular nodal disease.

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are particularly effective for PVC suppression in patients without structural heart disease by the mechanisms previously described involving intracellular calcium channels. In particular, they are highly effective and are considered the drugs of choice in treating fascicular PVCs.

Verapamil is a potent drug in this class, but it also commonly causes constipation as a side effect. Diltiazem is less constipating but can cause fatigue, drowsiness, and headaches. Both drugs reduce the resting heart rate and slow atrioventricular nodal conduction. Patients predisposed to bradycardia or atrioventricular block can develop dizziness or overt syncope. Calcium channel blockers are also used cautiously in patients with congestive heart failure, given their potential negative inotropic effects.

Overall, calcium channel blockers are a very reasonable choice for young patients without structural heart disease who need PVC suppression.

Other antiarrhythmic drugs

Sotalol merits special consideration because it has both beta-blocker and class III antiarrhythmic properties, blocking potassium channels and prolonging cardiac repolarization. It can be very effective in PVC suppression but also creates some degree of QT prolongation. The QT-prolonging effect is accentuated in patients with baseline QT prolongation or abnormal renal function. Rarely, this can lead to torsades de pointes. As a safety precaution, some patients are admitted to the hospital when they start sotalol therapy so that they can be monitored with continuous telemetry and ECG to detect excessive QT prolongation.

Amiodarone is a versatile drug with mixed pharmacologic properties that include a predominantly potassium channel-blocking class III drug effect. However, this effect is balanced by its other pharmacologic properties that make QT prolongation less of a clinical concern. Excessive QT prolongation may still occur when used concomitantly with other QT-prolonging drugs.

Amiodarone is very effective in suppressing PVCs and ventricular arrhythmias but has considerable short-term and long-term side effects. Cumulative toxicity risks include damage to the thyroid gland, liver, skin, eyes, and lungs. Routine thyroid function testing, pulmonary function testing, and eye examinations are often considered for patients on long-term amiodarone therapy. Short-term use of this drug does not typically require such surveillance.

Catheter ablation

As mentioned in the previous sections, catheter ablation is a safe and effective treatment for PVCs. It is curative in most cases, and significantly reduces the PVC burden in others.

Procedure. Patients are brought to the electrophysiology laboratory in a fasted state and are partially sedated with an intravenous drug such as midazolam or fentanyl, or both. Steerable catheters are placed into appropriate cardiac chambers from femoral access sites, which are infiltrated with local anesthesia. Sometimes sedative or analgesic drugs must be limited if they are known to suppress PVCs.

Most operators prefer a technique called activation mapping, in which the catheter is maneuvered to home in on the precise PVC origin within the heart, which is subsequently ablated. This technique has very high success rates, but having enough spontaneous PVCs to map during the procedure is essential for the technique to succeed. Conversely, not having sufficient PVCs on the day of the procedure is a common reason that ablation fails or cannot be performed at all.

Pace-mapping is an alternate technique that does not require a continuous stream of PVCs. This involves pacing from different candidate locations inside the heart in an effort to precisely match the ECG appearance of the clinical PVC and to ablate at this site. Although activation mapping generally yields higher success rates and is preferred by most operators, pace-mapping can be successful when a perfect 12–12 match is elicited. In many cases, the two techniques are used together during the same procedure, particularly if the patient’s PVCs spontaneously wax and wane, as they often do.

Risks. Like any medical procedure, catheter ablation carries some inherent risks, including rare but potentially serious events. Unstable arrhythmias may require pace-termination from the catheter or, rarely, shock-termination externally. Even more rare is cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Uncommon but life-threatening complications also include pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade requiring percutaneous drainage or, rarely, emergency surgical correction. Although such events are life-threatening, death is extremely rare.

Complications causing permanent disability are also very uncommon but include the risk of collateral injury to the conduction system requiring permanent pacemaker placement, injury to the coronary vessels requiring urgent treatment, or diaphragmatic injury affecting breathing. Left-sided cardiac ablation also carries a small risk of stroke, which is mitigated by giving intravenous heparin during the procedure.

More common but generally non-life-threatening complications include femoral vascular events such as hematomas, pseudoaneurysms, or fistulas that sometimes require subsequent treatment. These complications are generally treatable but can significantly prolong the recovery period.

Catheter ablation procedures are typically 2 to 6 hours in duration, depending on the chambers involved, PVC frequency, and other considerations. Postprocedure bed rest is required for a number of hours. A Foley catheter is sometimes used for patient comfort when a prolonged procedure is anticipated. This carries a small risk of urinary tract infection. Epicardial catheter ablation that requires access to the surface of the heart (ie, the pericardial space) is uncommon but carries some unique risks, including rare injury to coronary vessels or adjacent organs such as the liver or stomach.

Overall, both endocardial and epicardial catheter ablation can be performed safely and effectively in the overwhelming majority of patients, but understanding and explaining the potential risks remains a crucial part of the informed consent process.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- PVCs are a common cause of palpitations but are also noted as incidental findings by ECG, Holter monitoring, and inpatient telemetry.

- The diagnostic evaluation includes an assessment for underlying structural heart disease and quantification of the total PVC burden.

- Patients without structural heart disease and with low-to-modest PVC burdens may not require specific treatment. PVCs at greater burdens, typically 15% to 20%, or with specific high-risk features carry a risk of tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy and may require treatment even if they are asymptomatic. These high-risk features include initial QRS slurring and PVCs occurring at shorter coupling intervals.

- Treatment involves medical therapy with a beta-blocker, a calcium channel blocker, or another antiarrhythmic drug, and catheter ablation in selected cases.

- Catheter ablation can be curative but is typically reserved for drug-intolerant or medically refractory patients with a high PVC burden.

- Kostis JB, McCrone K, Moreyra AE, et al. Premature ventricular complexes in the absence of identifiable heart disease. Circulation 1981; 63:1351–1356.

- Sobotka PA, Mayer JH, Bauernfeind RA, Kanakis C, Rosen KM. Arrhythmias documented by 24-hour continuous ambulatory electrocardiographic monitoring in young women without apparent heart disease. Am Heart J 1981; 101:753–759.

- Niwano S, Wakisaka Y, Niwano H, et al. Prognostic significance of frequent premature ventricular contractions originating from the ventricular outflow tract in patients with normal left ventricular function. Heart 2009; 95:1230–1237.

- Simpson RJ, Cascio WE, Schreiner PJ, Crow RS, Rautaharju PM, Heiss G. Prevalence of premature ventricular contractions in a population of African American and white men and women: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Am Heart J 2002; 143:535–540.

- Chakko CS, Gheorghiade M. Ventricular arrhythmias in severe heart failure: incidence, significance, and effectiveness of antiarrhythmic therapy. Am Heart J 1985; 109:497–504.

- Gami AS, Noheria A, Lachman N, et al. Anatomical correlates relevant to ablation above the semilunar valves for the cardiac electrophysiologist: a study of 603 hearts. J Interv Card Electrophysiol 2011; 30:5–15.

- Lerman BB, Belardinelli L, West GA, Berne RM, DiMarco JP. Adenosine-sensitive ventricular tachycardia: evidence suggesting cyclic AMP-mediated triggered activity. Circulation 1986; 74:270–280.

- Lerman BB, Stein K, Engelstein ED, et al. Mechanism of repetitive monomorphic ventricular tachycardia. Circulation 1995; 92:421–429.

- Iwai S, Cantillon DJ, Kim RJ, et al. Right and left ventricular outflow tract tachycardias: evidence for a common electrophysiologic mechanism. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 2006; 17:1052–1058.

- Kim RJ, Iwai S, Markowitz SM, Shah BK, Stein KM, Lerman BB. Clinical and electrophysiological spectrum of idiopathic ventricular outflow tract arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 49:2035–2043.

- Yamada T, McElderry HT, Doppalapudi H, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from the left ventricular summit: anatomic concepts relevant to ablation. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010; 3:616–623.

- Ouyang F, Cappato R, Ernst S, et al. Electroanatomic substrate of idiopathic left ventricular tachycardia: unidirectional block and macro-reentry within the Purkinje network. Circulation 2002; 105:462–469.

- Iwai S, Lerman BB. Management of ventricular tachycardia in patients with clinically normal hearts. Curr Cardiol Rep 2000; 2:515–521.

- Nogami A. Purkinje-related arrhythmias part I: monomorphic ventricular tachycardias. Pacing Clin Electrophysiol 2011; 34:624–650.

- Letsas KP, Efremidis M, Kollias G, Xydonas S, Sideris A. Electrocardiographic and electrophysiologic characteristics of ventricular extrasystoles arising from the aortomitral continuity. Cardiol Res Pract 2011; 2011:864964.

- Tada H, Tadokoro K, Ito S, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias originating from the tricuspid annulus: prevalence, electrocardiographic characteristics, and results of radiofrequency catheter ablation. Heart Rhythm 2007; 4:7–16.

- Tada H, Ito S, Naito S, et al. Idiopathic ventricular arrhythmia arising from the mitral annulus: a distinct subgroup of idiopathic ventricular arrhythmias. J Am Coll Cardiol 2005; 45:877–886.

- Doppalapudi H, Yamada T, McElderry HT, Plumb VJ, Epstein AE, Kay GN. Ventricular tachycardia originating from the posterior papillary muscle in the left ventricle: a distinct clinical syndrome. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2008; 1:23–29.

- Scheinman MM. Role of the His-Purkinje system in the genesis of cardiac arrhythmia. Heart Rhythm 2009; 6:1050–1058.

- Bigger JT, Dresdale FJ, Heissenbuttel RH, Weld FM, Wit AL. Ventricular arrhythmias in ischemic heart disease: mechanism, prevalence, significance, and management. Prog Cardiovasc Dis 1977; 19:255–300.

- Eldar M, Sievner Z, Goldbourt U, Reicher-Reiss H, Kaplinsky E, Behar S. Primary ventricular tachycardia in acute myocardial infarction: clinical characteristics and mortality. The SPRINT Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1992; 117:31–36.

- Preliminary report: effect of encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia suppression after myocardial infarction. The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) Investigators. N Engl J Med 1989; 321:406–412.

- Moss AJ, Zareba W, Hall WJ, et al; Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II Investigators. Prophylactic implantation of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med 2002; 346:877–883.

- Cano O, Hutchinson M, Lin D, et al. Electroanatomic substrate and ablation outcome for suspected epicardial ventricular tachycardia in left ventricular nonischemic cardiomyopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol 2009; 54:799–808.

- Marchlinski FE. Perivalvular fibrosis and monomorphic ventricular tachycardia: toward a unifying hypothesis in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circulation 2007; 116:1998–2001.

- Vallès E, Bazan V, Marchlinski FE. ECG criteria to identify epicardial ventricular tachycardia in nonischemic cardiomyopathy. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2010; 3:63–71.

- Marcus FI, McKenna WJ, Sherrill D, et al. Diagnosis of arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: proposed modification of the task force criteria. Circulation 2010; 121:1533–1541.

- Lee GK, Klarich KW, Grogan M, Cha YM. Premature ventricular contraction-induced cardiomyopathy: a treatable condition. Circ Arrhythm Electrophysiol 2012; 5:229–236.

- Yarlagadda RK, Iwai S, Stein KM, et al. Reversal of cardiomyopathy in patients with repetitive monomorphic ventricular ectopy originating from the right ventricular outflow tract. Circulation 2005; 112:1092–1097.

- Kanei Y, Friedman M, Ogawa N, Hanon S, Lam P, Schweitzer P. Frequent premature ventricular complexes originating from the right ventricular outflow tract are associated with left ventricular dysfunction. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 2008; 13:81–85.

- Baman TS, Lange DC, Ilg KJ, et al. Relationship between burden of premature ventricular complexes and left ventricular function. Heart Rhythm 2010; 7:865–869.

- Moulton KP, Medcalf T, Lazzara R. Premature ventricular complex morphology. A marker for left ventricular structure and function. Circulation 1990; 81:1245–1251.

- Olgun H, Yokokawa M, Baman T, et al. The role of interpolation in PVC-induced cardiomyopathy. Heart Rhythm 2011; 8:1046–1049.

- Sun Y, Blom NA, Yu Y, et al. The influence of premature ventricular contractions on left ventricular function in asymptomatic children without structural heart disease: an echocardiographic evaluation. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging 2003; 19:295–299.

- Sarrazin JF, Labounty T, Kuhne M, et al. Impact of radiofrequency ablation of frequent post-infarction premature ventricular complexes on left ventricular ejection fraction. Heart Rhythm 2009; 6:1543–1549.

- DeBacker G, Jacobs D, Prineas R, et al. Ventricular premature contractions: a randomized non-drug intervention trial in normal men. Circulation 1979; 59:762–769.

- Glatter KA, Myers R, Chiamvimonvat N. Recommendations regarding dietary intake and caffeine and alcohol consumption in patients with cardiac arrhythmias: what do you tell your patients to do or not to do? Curr Treat Options Cardiovasc Med 2012; 14:529–535.

Premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) are a common cause of palpitations, and are also often detected incidentally on electrocardiography (ECG), ambulatory monitoring, or inpatient telemetry. At the cellular level, ventricular myocytes spontaneously depolarize to create an extra systole that is “out of sync” with the cardiac cycle.

Although nearly everyone has some PVCs from time to time, people vary widely in their frequency of PVCs and their sensitivity to them.1,2 Some patients are exquisitely sensitive to even a small number of PVCs, while others are completely unaware of PVCs in a bigeminal pattern (ie, every other heartbeat). This article will review the evaluation and management of PVCs with a focus on clinical aspects.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Personal and family history

Symptoms. The initial history should establish the presence, extent, timing, and duration of symptoms. Patients may use the word “palpitations” to describe their symptoms, but they also describe them as “hard” heartbeats, “chest-thumping,” or as a “catch” or “skipped” heartbeat. Related symptoms may include difficulty breathing, chest pain, fatigue, and dizziness.

The interview should determine whether the symptoms represent a minor nuisance or a major quality-of-life issue to the patient, and whether there are any specific associations or triggers. For example, it is very common for patients to become aware of PVCs at night, particularly in certain positions, such as lying on the left side. Patients often associate PVC symptoms with emotional stress, exercise, or caffeine or stimulant use.

Medication use. An accurate and up-to-date list of prescription medications should be screened for alpha-, beta-, or dopamine-receptor agonist drugs. Similarly, any use of over-the-counter sympathomimetic medications and nonprescription supplements should be elicited, including compounded elixirs or beverages. Many commercially available products designed to treat fatigue or increase alertness contain large doses of caffeine or other stimulants. It is also important to consider the use of illicit substances such as cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and their derivatives.

The patient’s medical and surgical history should be queried for any known structural heart disease, including coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, and heritable conditions such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, prolonged QT syndromes, or other channel disorders. Pulmonary disorders such as sarcoidosis, pulmonary hypertension, or obstructive sleep apnea are also relevant. Similarly, it is important to identify endocrine disorders, including thyroid problems, sex hormone abnormalities, or adrenal gland conditions.

A careful family history should include any instance of sudden death in first-degree relatives, any heritable cardiac conditions, or coronary artery disease at an early age.

Physical examination

The physical examination should focus on findings that suggest underlying structural heart disease. Findings suggestive of congestive heart failure include elevated jugular venous pressures, abnormal cardiac sounds, pulmonary rales, abnormal arterial pulses, or peripheral edema. A murmur or a pathologic heart sound should raise suspicion of valvular or congenital heart disease when present in a young patient.

Inspection and palpation of the thyroid can reveal a related disorder. Obvious skin changes or neurologic findings can similarly reveal a systemic and possibly related clinical disorder that can have cardiac manifestations (eg, muscular dystrophy).

Electrocardiography, Holter monitoring, and other monitoring

Assessment of the cardiac rhythm includes 12-lead ECG and ambulatory Holter monitoring, typically for 24 or 48 hours.

Holter monitoring provides a continuous recording, usually in at least two or three leads. Patients are given a symptom journal or are asked to keep a diary of symptoms experienced during the monitoring period. The monitor is worn underneath clothing and is returned for download upon completion. Technicians process the data with the aid of computer software, and the final output is reviewed and interpreted by a cardiologist or cardiac electrophysiologist.

Holter monitoring for at least 24 hours is a critical step in assessing any patient with known or suspected PVCs, as it can both quantify the total burden of ventricular ectopy and identify the presence of any related ventricular tachycardia. In addition, it can detect additional supraventricular arrhythmias or bradycardia during the monitoring period. The PVC burden is an important measurement; it is expressed as the percentage of heartbeats that were ventricular extrasystoles during the monitoring period.

Both ECG and Holter monitoring are limited in that they are only snapshots of the rhythm during the period when a patient is actually hooked up. Many patients experience PVCs in clusters every very few days or weeks. Such a pattern is unlikely to be detected by a single ECG or 24- or 48-hour Holter monitoring.

A 30-day ambulatory event monitor (also known as a wearable loop recorder) is an important diagnostic tool in these scenarios. The concept is very similar to that of Holter monitoring, except that the device provides a continuous loop recording of the cardiac rhythm that is digitally stored in clips when the patient activates the device. Some wearable loop recorders also have auto-save features for heart rates falling outside of a programmed range.

Mobile outpatient cardiac telemetry is the most comprehensive form of noninvasive rhythm monitoring available. This is essentially the equivalent of continuous inpatient cardiac telemetry, but in a patient who is not hospitalized. It is a wearable ambulatory device providing continuous recordings, real-time automatic detections, and patient-activated symptom recordings. It can be used for up to 6 weeks. Advantages include detection and quantification of asymptomatic events, and real-time transmissions that the physician can act upon. The major disadvantage is cost, including coverage denial by many third-party payers.

This test is rarely indicated as part of a PVC evaluation and is typically ordered only by a cardiologist or cardiac electrophysiologist.

Noninvasive cardiac evaluation

Surface echocardiography is indicated to look for overt structural heart disease and can reliably detect abnormalities in cardiac chamber size, wall thickness, and function. Valvular heart disease is concomitantly identified by two-dimensional imaging as well as by color Doppler. The finding of significant structural heart disease in conjunction with PVCs should prompt a cardiology referral, as this carries significant prognostic implications.3–5

Exercise treadmill stress testing is appropriate for patients who experience PVCs with exercise or for whom an evaluation for coronary artery disease is indicated. The expected finding would be an increase in PVCs or ventricular tachycardia with exercise or in the subsequent recovery period. Exercise testing can be combined with either echocardiographic or nuclear perfusion imaging to evaluate the possibility of myocardial ischemia. For patients unable to exercise, pharmacologic stress testing with dobutamine or a vasodilator agent can be performed.

Advanced noninvasive cardiac imaging— such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron-emission tomography—should be reserved for specific clinical indications such as congenital heart disease, suspected cardiac sarcoidosis, and infiltrative heart disease, and for specific cardiomyopathies, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. For example, frequent PVCs with a left bundle branch block morphology and superior axis raise the concern for a right ventricular disorder and may prompt cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for either arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy or sarcoidosis.

PVCs WITHOUT STRUCTURAL HEART DISEASE

Outflow tract PVCs and ventricular tachycardia

The right or left ventricular outflow tracts, or the epicardial tissue immediately adjacent to the aortic sinuses of Valsalva are the most common sites of origin for ventricular ectopy in the absence of structural heart disease.6–9 Affected cells often demonstrate a triggered activity mechanism due to cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated and calcium-dependent delayed after-depolarizations.7,8

Most of these foci are in the right ventricular outflow tract, producing a left bundle branch block morphology with an inferior axis (positive R waves in limb leads II, III, and aVF) and typical precordial R-wave transition in V3 and V4 (Figure 1). A minority are in the left ventricular outflow tract, producing a right bundle branch block with an inferior axis pattern, or in the aortic sinuses with a left bundle branch block pattern but with early precordial R transition in V2 and V3.

A study in 122 patients showed that right and left outflow tract arrhythmias had similar electrophysiologic properties and pharmacologic sensitivities, providing evidence for shared mechanisms possibly due to the common embryologic origin of these structures.9

Such arrhythmias are typically catecholamine-sensitive and are sometimes inducible with burst pacing in the electrophysiology laboratory. The short ventricular coupling intervals can promote intracellular calcium overload in the affected cells, leading to triggered activity.

Therefore, outflow tract PVCs and ventricular tachycardia are commonly encountered clinically during exercise and, to an even greater extent, in the postexercise cool-down period. Similarly, they can be worse during periods of emotional stress or fatigue, when the body’s endogenous catecholamine production is elevated. However, it is worthwhile to note that there are exceptions to this principle in which faster sinus rates seem to overdrive the PVCs in some patients, causing them to become paradoxically more frequent at rest, or even during sleep.

Outflow tract PVCs can be managed medically with beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil or diltiazem), or, less commonly, class IC drugs such as flecainide. They are also highly curable by catheter ablation (Figure 2), with procedure success rates greater than 90%.9.10

However, a subset of outflow tract PVCs nested deep in a triangle of epicardial tissue between the right and left endocardial surface and underneath the left main coronary artery can be challenging. This region has been labeled the left ventricular summit, and is shielded from ablation by an epicardial fat pad in the adjacent pericardial space.11 Ablation attempts made from the right and left endocardial surfaces as well as the epicardial surface (pericardial space) sometimes cannot adequately penetrate the tissue deep enough to reach the originating focus deep within this triangle. While ablation cannot always fully eliminate the PVC, ablation from more than one of the sites listed can generally reduce its burden, often in combination with suppressive medical therapy (Figure 3).

Fascicular PVCs

Fascicular PVCs originate from within the left ventricular His-Purkinje system12 and produce a right bundle branch block morphology with either an anterior or posterior hemiblock pattern (Figure 4). Exit from the posterior fascicle causes an anterior hemiblock pattern, and exit from the anterior fascicle a posterior hemiblock pattern. Utilization of the rapidly conducting His-Purkinje system gives these PVCs a very narrow QRS duration, sometimes approaching 120 milliseconds or shorter. This occasionally causes them to be mistaken for aberrantly conducted supraventricular beats. Such spontaneous PVCs are commonly associated with both sustained and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and are usually sensitive to verapamil.13

Special issues relating to mapping and catheter ablation of fascicular arrhythmias involve the identification of Purkinje fiber potentials and associated procedural diagnostic maneuvers during tachycardia.14

Other sites for PVCs

Other sites of origin for PVCs in the absence of structural heart disease include ventricular tissue adjacent to the aortomitral continuity,15 the tricuspid annulus,16 the mitral valve annulus, 17 papillary muscles,18 and other Purkinje-adjacent structures such as left ventricular false tendons.19 An example of a papillary muscle PVC is shown in Figures 5 and 6.

Curable by catheter ablation

Any of these PVCs can potentially be cured by catheter ablation when present at a sufficient burden to allow for activation mapping in the electrophysiology laboratory. The threshold for offering ablation varies among operators, but is generally around 10% or greater. Pacemapping is a technique applied in the electrophysiology laboratory when medically refractory symptomatic PVCs occurring at a lower burden require ablation.

PVCs WITH AN UNDERLYING CARDIAC CONDITION

Coronary artery disease

Tissue injury and death caused by acute myocardial infarction has long been recognized as a common cause of spontaneous ventricular ectopy attributed to infarct border zones of ischemic or hibernating myocardium.20,21

Suppression has not been associated with improved outcomes, as shown for class IC drugs in the landmark Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST),22 or in the amiodarone treatment arm of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT-II).23 Therefore, treatment of ventricular ectopy in this patient population is usually symptom-driven unless there is hemodynamic intolerance, tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy, or a very high burden of PVCs in a patient who may be at risk of developing tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy. Antiarrhythmic drug treatment, when required, usually involves beta-blockers or class III medications such as sotalol or amiodarone.

Nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy

This category includes patients with a wide variety of disease states including valvular heart disease, lymphocytic and other viral myocarditis, cardiac sarcoidosis, amyloidosis and other infiltrative diseases, familial conditions, and idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy (ie, etiology unknown). Although it is a heterogeneous group, a common theme is that PVCs in this patient cohort may require epicardial mapping and ablation.24 Similarly, epicardial PVCs and ventricular tachycardia cluster at the basal posterolateral left ventricle near the mitral annulus, for unclear reasons.25

While specific criteria have been published, an epicardial focus is suggested by slowing of the initial QRS segment, pseudo-delta waves, a wider overall QRS, and Q waves in limb lead I.26

Treatment is symptom-driven unless the patient has a tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy or a high burden associated with the risk for its development. Antiarrhythmic drug therapy, when required, typically involves a beta-blocker or a class III drug such as sotalol or amiodarone. Sotalol is used in this population but has limited safety data and should be used cautiously in patients without an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator.

Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy

Spontaneous ventricular ectopy and tachycardia are common, if not expected, in patients with this heritable autosomal dominant disorder. This condition is progressive and associated with the risk of sudden cardiac death. Criteria for diagnosis were established in 2010, and patients with suspected arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy often undergo cardiac magnetic resonance imaging.27 Diagnostic findings include fibro-fatty tissue replacement, which usually starts in the right ventricle but can progress to involve the left ventricle. PVCs and ventricular tachycardia can involve the right ventricular free wall and are often epicardial.

Catheter ablation is usually palliative, as future arrhythmias are expected. Many patients with this condition require an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for prevention of sudden cardiac death, and some go on to cardiac transplantation as the disease progresses and ventricular arrhythmias become incessant.

Other conditions

Spontaneous ventricular ectopy is common in other heritable and acquired cardiomyopathies including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and in infiltrative or inflammatory disorders such as cardiac amyloidosis and sarcoidosis. While technically falling under the rubric of nonischemic heart disease, the presence of spontaneous ventricular ectopy carries specific prognostic implications depending on the underlying diagnosis. Therefore, an appropriate referral for complete cardiac evaluation should be considered when a heritable disorder or other acquired structural heart disease is suspected.

TACHYCARDIA-RELATED CARDIOMYOPATHY

Tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy refers to left ventricular systolic dysfunction that is primarily caused by arrhythmias. This includes frequent PVCs or ventricular tachycardia but also atrial arrhythmias occurring at a high burden that directly weaken myocardial function over time. Although much research has been devoted to this condition, our understanding of its etiology and pathology is incomplete.

PVCs and ventricular ectopy burdens in excess of 15% to 20% have been associated with the development of this condition.28,29 However, it is important to note that cardiomyopathy can also develop at lower burdens.30 One study found that a burden greater than 24% was 79% sensitive and 78% specific for development of tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy.31 Additional studies have demonstrated specific PVC morphologic features such as slurring in the initial QRS segment and also PVCs occurring at shorter coupling intervals as being associated with cardiomyopathy.32–34

For these reasons, both quantification of the total burden and careful evaluation of available electrocardiograms and rhythm strips are important even in asymptomatic patients with frequent PVCs. Similarly, unexplained left ventricular dysfunction in patients with PVC burdens in these discussed ranges should raise suspicion for this diagnosis. Patients with tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy usually have at least partially reversible left ventricular dysfunction when identified or treated early.29,35

MEDICAL AND ABLATIVE TREATMENT

Available treatments include medical suppression and catheter ablation. One needs to exercise clinical judgment and incorporate all of the PVC-related data to make treatment decisions.

Little data for trigger avoidance and behavioral modification

Some patients report a strong association between palpitations related to PVCs and caffeine intake, other stimulants, or other dietary triggers. However, few data exist to support the role of trigger avoidance and behavioral modification in treatment. In fact, an older randomized trial in 81 men found no benefit in a program of total abstinence from caffeine and smoking, moderation of alcohol intake, and physical conditioning.36

Nonetheless, some argue in favor of advising patients to make these dietary and lifestyle changes, given the overall health benefits of aggressive risk-factor modification for cardiovascular disease.37 Certainly, a trial of trigger avoidance and behavioral modification seems reasonable for patients who have strongly associated historical triggers in the absence of structural heart disease and PVCs occurring at a low to modest burden.

Beta-blockers are the mainstay

Beta-blockers are the mainstay of medical suppression of PVCs, primarily through their effect on beta-1 adrenergic receptors to reduce intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate and thus decrease automaticity. Blocking beta-1 receptors also causes a negative chronotropic effect, reducing the resting sinus rate in addition to slowing atrioventricular nodal conduction.

Cardioselective beta-blockers include atenolol, betaxolol, metoprolol, and nadolol. These drugs are effective in suppressing PVCs, or at least in reducing the burden to more tolerable levels.

Beta-blockers are most strongly indicated in patients who require PVC suppression and who have concomitant coronary artery disease, prior myocardial infarction, or other cardiomyopathy, as this drug class favorably affects long-term prognosis in these conditions.

Common side effects of beta-blockers include fatigue, shortness of breath, depressed mood, and loss of libido. Side effects can present a significant challenge, particularly for younger patients. Noncardioselective beta-blockers are less commonly prescribed, with the exception of propranolol, which is an effective sympatholytic drug that blocks both beta-1 and beta-2 receptors.

Many patients with asthma or peripheral arterial disease can tolerate these drugs well despite concerns about provoked bronchospasm or claudication, respectively, and neither of these conditions is considered an absolute contraindication. Excessive bradycardia with beta-blocker therapy can lead to dizziness, lightheadedness, or overt syncope, and these drugs should be used with caution in patients with baseline sinus node dysfunction or atrioventricular nodal disease.

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers

Nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers are particularly effective for PVC suppression in patients without structural heart disease by the mechanisms previously described involving intracellular calcium channels. In particular, they are highly effective and are considered the drugs of choice in treating fascicular PVCs.

Verapamil is a potent drug in this class, but it also commonly causes constipation as a side effect. Diltiazem is less constipating but can cause fatigue, drowsiness, and headaches. Both drugs reduce the resting heart rate and slow atrioventricular nodal conduction. Patients predisposed to bradycardia or atrioventricular block can develop dizziness or overt syncope. Calcium channel blockers are also used cautiously in patients with congestive heart failure, given their potential negative inotropic effects.

Overall, calcium channel blockers are a very reasonable choice for young patients without structural heart disease who need PVC suppression.

Other antiarrhythmic drugs

Sotalol merits special consideration because it has both beta-blocker and class III antiarrhythmic properties, blocking potassium channels and prolonging cardiac repolarization. It can be very effective in PVC suppression but also creates some degree of QT prolongation. The QT-prolonging effect is accentuated in patients with baseline QT prolongation or abnormal renal function. Rarely, this can lead to torsades de pointes. As a safety precaution, some patients are admitted to the hospital when they start sotalol therapy so that they can be monitored with continuous telemetry and ECG to detect excessive QT prolongation.

Amiodarone is a versatile drug with mixed pharmacologic properties that include a predominantly potassium channel-blocking class III drug effect. However, this effect is balanced by its other pharmacologic properties that make QT prolongation less of a clinical concern. Excessive QT prolongation may still occur when used concomitantly with other QT-prolonging drugs.

Amiodarone is very effective in suppressing PVCs and ventricular arrhythmias but has considerable short-term and long-term side effects. Cumulative toxicity risks include damage to the thyroid gland, liver, skin, eyes, and lungs. Routine thyroid function testing, pulmonary function testing, and eye examinations are often considered for patients on long-term amiodarone therapy. Short-term use of this drug does not typically require such surveillance.

Catheter ablation

As mentioned in the previous sections, catheter ablation is a safe and effective treatment for PVCs. It is curative in most cases, and significantly reduces the PVC burden in others.

Procedure. Patients are brought to the electrophysiology laboratory in a fasted state and are partially sedated with an intravenous drug such as midazolam or fentanyl, or both. Steerable catheters are placed into appropriate cardiac chambers from femoral access sites, which are infiltrated with local anesthesia. Sometimes sedative or analgesic drugs must be limited if they are known to suppress PVCs.

Most operators prefer a technique called activation mapping, in which the catheter is maneuvered to home in on the precise PVC origin within the heart, which is subsequently ablated. This technique has very high success rates, but having enough spontaneous PVCs to map during the procedure is essential for the technique to succeed. Conversely, not having sufficient PVCs on the day of the procedure is a common reason that ablation fails or cannot be performed at all.

Pace-mapping is an alternate technique that does not require a continuous stream of PVCs. This involves pacing from different candidate locations inside the heart in an effort to precisely match the ECG appearance of the clinical PVC and to ablate at this site. Although activation mapping generally yields higher success rates and is preferred by most operators, pace-mapping can be successful when a perfect 12–12 match is elicited. In many cases, the two techniques are used together during the same procedure, particularly if the patient’s PVCs spontaneously wax and wane, as they often do.

Risks. Like any medical procedure, catheter ablation carries some inherent risks, including rare but potentially serious events. Unstable arrhythmias may require pace-termination from the catheter or, rarely, shock-termination externally. Even more rare is cardiac arrest requiring cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Uncommon but life-threatening complications also include pericardial effusion or cardiac tamponade requiring percutaneous drainage or, rarely, emergency surgical correction. Although such events are life-threatening, death is extremely rare.

Complications causing permanent disability are also very uncommon but include the risk of collateral injury to the conduction system requiring permanent pacemaker placement, injury to the coronary vessels requiring urgent treatment, or diaphragmatic injury affecting breathing. Left-sided cardiac ablation also carries a small risk of stroke, which is mitigated by giving intravenous heparin during the procedure.

More common but generally non-life-threatening complications include femoral vascular events such as hematomas, pseudoaneurysms, or fistulas that sometimes require subsequent treatment. These complications are generally treatable but can significantly prolong the recovery period.

Catheter ablation procedures are typically 2 to 6 hours in duration, depending on the chambers involved, PVC frequency, and other considerations. Postprocedure bed rest is required for a number of hours. A Foley catheter is sometimes used for patient comfort when a prolonged procedure is anticipated. This carries a small risk of urinary tract infection. Epicardial catheter ablation that requires access to the surface of the heart (ie, the pericardial space) is uncommon but carries some unique risks, including rare injury to coronary vessels or adjacent organs such as the liver or stomach.

Overall, both endocardial and epicardial catheter ablation can be performed safely and effectively in the overwhelming majority of patients, but understanding and explaining the potential risks remains a crucial part of the informed consent process.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- PVCs are a common cause of palpitations but are also noted as incidental findings by ECG, Holter monitoring, and inpatient telemetry.

- The diagnostic evaluation includes an assessment for underlying structural heart disease and quantification of the total PVC burden.

- Patients without structural heart disease and with low-to-modest PVC burdens may not require specific treatment. PVCs at greater burdens, typically 15% to 20%, or with specific high-risk features carry a risk of tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy and may require treatment even if they are asymptomatic. These high-risk features include initial QRS slurring and PVCs occurring at shorter coupling intervals.

- Treatment involves medical therapy with a beta-blocker, a calcium channel blocker, or another antiarrhythmic drug, and catheter ablation in selected cases.

- Catheter ablation can be curative but is typically reserved for drug-intolerant or medically refractory patients with a high PVC burden.

Premature ventricular complexes (PVCs) are a common cause of palpitations, and are also often detected incidentally on electrocardiography (ECG), ambulatory monitoring, or inpatient telemetry. At the cellular level, ventricular myocytes spontaneously depolarize to create an extra systole that is “out of sync” with the cardiac cycle.

Although nearly everyone has some PVCs from time to time, people vary widely in their frequency of PVCs and their sensitivity to them.1,2 Some patients are exquisitely sensitive to even a small number of PVCs, while others are completely unaware of PVCs in a bigeminal pattern (ie, every other heartbeat). This article will review the evaluation and management of PVCs with a focus on clinical aspects.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Personal and family history

Symptoms. The initial history should establish the presence, extent, timing, and duration of symptoms. Patients may use the word “palpitations” to describe their symptoms, but they also describe them as “hard” heartbeats, “chest-thumping,” or as a “catch” or “skipped” heartbeat. Related symptoms may include difficulty breathing, chest pain, fatigue, and dizziness.

The interview should determine whether the symptoms represent a minor nuisance or a major quality-of-life issue to the patient, and whether there are any specific associations or triggers. For example, it is very common for patients to become aware of PVCs at night, particularly in certain positions, such as lying on the left side. Patients often associate PVC symptoms with emotional stress, exercise, or caffeine or stimulant use.

Medication use. An accurate and up-to-date list of prescription medications should be screened for alpha-, beta-, or dopamine-receptor agonist drugs. Similarly, any use of over-the-counter sympathomimetic medications and nonprescription supplements should be elicited, including compounded elixirs or beverages. Many commercially available products designed to treat fatigue or increase alertness contain large doses of caffeine or other stimulants. It is also important to consider the use of illicit substances such as cocaine, amphetamine, methamphetamine, and their derivatives.

The patient’s medical and surgical history should be queried for any known structural heart disease, including coronary artery disease, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, valvular heart disease, congenital heart disease, and heritable conditions such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, prolonged QT syndromes, or other channel disorders. Pulmonary disorders such as sarcoidosis, pulmonary hypertension, or obstructive sleep apnea are also relevant. Similarly, it is important to identify endocrine disorders, including thyroid problems, sex hormone abnormalities, or adrenal gland conditions.

A careful family history should include any instance of sudden death in first-degree relatives, any heritable cardiac conditions, or coronary artery disease at an early age.

Physical examination

The physical examination should focus on findings that suggest underlying structural heart disease. Findings suggestive of congestive heart failure include elevated jugular venous pressures, abnormal cardiac sounds, pulmonary rales, abnormal arterial pulses, or peripheral edema. A murmur or a pathologic heart sound should raise suspicion of valvular or congenital heart disease when present in a young patient.

Inspection and palpation of the thyroid can reveal a related disorder. Obvious skin changes or neurologic findings can similarly reveal a systemic and possibly related clinical disorder that can have cardiac manifestations (eg, muscular dystrophy).

Electrocardiography, Holter monitoring, and other monitoring

Assessment of the cardiac rhythm includes 12-lead ECG and ambulatory Holter monitoring, typically for 24 or 48 hours.

Holter monitoring provides a continuous recording, usually in at least two or three leads. Patients are given a symptom journal or are asked to keep a diary of symptoms experienced during the monitoring period. The monitor is worn underneath clothing and is returned for download upon completion. Technicians process the data with the aid of computer software, and the final output is reviewed and interpreted by a cardiologist or cardiac electrophysiologist.

Holter monitoring for at least 24 hours is a critical step in assessing any patient with known or suspected PVCs, as it can both quantify the total burden of ventricular ectopy and identify the presence of any related ventricular tachycardia. In addition, it can detect additional supraventricular arrhythmias or bradycardia during the monitoring period. The PVC burden is an important measurement; it is expressed as the percentage of heartbeats that were ventricular extrasystoles during the monitoring period.

Both ECG and Holter monitoring are limited in that they are only snapshots of the rhythm during the period when a patient is actually hooked up. Many patients experience PVCs in clusters every very few days or weeks. Such a pattern is unlikely to be detected by a single ECG or 24- or 48-hour Holter monitoring.

A 30-day ambulatory event monitor (also known as a wearable loop recorder) is an important diagnostic tool in these scenarios. The concept is very similar to that of Holter monitoring, except that the device provides a continuous loop recording of the cardiac rhythm that is digitally stored in clips when the patient activates the device. Some wearable loop recorders also have auto-save features for heart rates falling outside of a programmed range.

Mobile outpatient cardiac telemetry is the most comprehensive form of noninvasive rhythm monitoring available. This is essentially the equivalent of continuous inpatient cardiac telemetry, but in a patient who is not hospitalized. It is a wearable ambulatory device providing continuous recordings, real-time automatic detections, and patient-activated symptom recordings. It can be used for up to 6 weeks. Advantages include detection and quantification of asymptomatic events, and real-time transmissions that the physician can act upon. The major disadvantage is cost, including coverage denial by many third-party payers.

This test is rarely indicated as part of a PVC evaluation and is typically ordered only by a cardiologist or cardiac electrophysiologist.

Noninvasive cardiac evaluation

Surface echocardiography is indicated to look for overt structural heart disease and can reliably detect abnormalities in cardiac chamber size, wall thickness, and function. Valvular heart disease is concomitantly identified by two-dimensional imaging as well as by color Doppler. The finding of significant structural heart disease in conjunction with PVCs should prompt a cardiology referral, as this carries significant prognostic implications.3–5

Exercise treadmill stress testing is appropriate for patients who experience PVCs with exercise or for whom an evaluation for coronary artery disease is indicated. The expected finding would be an increase in PVCs or ventricular tachycardia with exercise or in the subsequent recovery period. Exercise testing can be combined with either echocardiographic or nuclear perfusion imaging to evaluate the possibility of myocardial ischemia. For patients unable to exercise, pharmacologic stress testing with dobutamine or a vasodilator agent can be performed.

Advanced noninvasive cardiac imaging— such as computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, or positron-emission tomography—should be reserved for specific clinical indications such as congenital heart disease, suspected cardiac sarcoidosis, and infiltrative heart disease, and for specific cardiomyopathies, such as hypertrophic cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy. For example, frequent PVCs with a left bundle branch block morphology and superior axis raise the concern for a right ventricular disorder and may prompt cardiac magnetic resonance imaging for either arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy or sarcoidosis.

PVCs WITHOUT STRUCTURAL HEART DISEASE

Outflow tract PVCs and ventricular tachycardia

The right or left ventricular outflow tracts, or the epicardial tissue immediately adjacent to the aortic sinuses of Valsalva are the most common sites of origin for ventricular ectopy in the absence of structural heart disease.6–9 Affected cells often demonstrate a triggered activity mechanism due to cyclic adenosine monophosphate-mediated and calcium-dependent delayed after-depolarizations.7,8

Most of these foci are in the right ventricular outflow tract, producing a left bundle branch block morphology with an inferior axis (positive R waves in limb leads II, III, and aVF) and typical precordial R-wave transition in V3 and V4 (Figure 1). A minority are in the left ventricular outflow tract, producing a right bundle branch block with an inferior axis pattern, or in the aortic sinuses with a left bundle branch block pattern but with early precordial R transition in V2 and V3.

A study in 122 patients showed that right and left outflow tract arrhythmias had similar electrophysiologic properties and pharmacologic sensitivities, providing evidence for shared mechanisms possibly due to the common embryologic origin of these structures.9

Such arrhythmias are typically catecholamine-sensitive and are sometimes inducible with burst pacing in the electrophysiology laboratory. The short ventricular coupling intervals can promote intracellular calcium overload in the affected cells, leading to triggered activity.

Therefore, outflow tract PVCs and ventricular tachycardia are commonly encountered clinically during exercise and, to an even greater extent, in the postexercise cool-down period. Similarly, they can be worse during periods of emotional stress or fatigue, when the body’s endogenous catecholamine production is elevated. However, it is worthwhile to note that there are exceptions to this principle in which faster sinus rates seem to overdrive the PVCs in some patients, causing them to become paradoxically more frequent at rest, or even during sleep.

Outflow tract PVCs can be managed medically with beta-blockers, nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers (verapamil or diltiazem), or, less commonly, class IC drugs such as flecainide. They are also highly curable by catheter ablation (Figure 2), with procedure success rates greater than 90%.9.10

However, a subset of outflow tract PVCs nested deep in a triangle of epicardial tissue between the right and left endocardial surface and underneath the left main coronary artery can be challenging. This region has been labeled the left ventricular summit, and is shielded from ablation by an epicardial fat pad in the adjacent pericardial space.11 Ablation attempts made from the right and left endocardial surfaces as well as the epicardial surface (pericardial space) sometimes cannot adequately penetrate the tissue deep enough to reach the originating focus deep within this triangle. While ablation cannot always fully eliminate the PVC, ablation from more than one of the sites listed can generally reduce its burden, often in combination with suppressive medical therapy (Figure 3).

Fascicular PVCs

Fascicular PVCs originate from within the left ventricular His-Purkinje system12 and produce a right bundle branch block morphology with either an anterior or posterior hemiblock pattern (Figure 4). Exit from the posterior fascicle causes an anterior hemiblock pattern, and exit from the anterior fascicle a posterior hemiblock pattern. Utilization of the rapidly conducting His-Purkinje system gives these PVCs a very narrow QRS duration, sometimes approaching 120 milliseconds or shorter. This occasionally causes them to be mistaken for aberrantly conducted supraventricular beats. Such spontaneous PVCs are commonly associated with both sustained and nonsustained ventricular tachycardia and are usually sensitive to verapamil.13

Special issues relating to mapping and catheter ablation of fascicular arrhythmias involve the identification of Purkinje fiber potentials and associated procedural diagnostic maneuvers during tachycardia.14

Other sites for PVCs

Other sites of origin for PVCs in the absence of structural heart disease include ventricular tissue adjacent to the aortomitral continuity,15 the tricuspid annulus,16 the mitral valve annulus, 17 papillary muscles,18 and other Purkinje-adjacent structures such as left ventricular false tendons.19 An example of a papillary muscle PVC is shown in Figures 5 and 6.

Curable by catheter ablation

Any of these PVCs can potentially be cured by catheter ablation when present at a sufficient burden to allow for activation mapping in the electrophysiology laboratory. The threshold for offering ablation varies among operators, but is generally around 10% or greater. Pacemapping is a technique applied in the electrophysiology laboratory when medically refractory symptomatic PVCs occurring at a lower burden require ablation.

PVCs WITH AN UNDERLYING CARDIAC CONDITION

Coronary artery disease

Tissue injury and death caused by acute myocardial infarction has long been recognized as a common cause of spontaneous ventricular ectopy attributed to infarct border zones of ischemic or hibernating myocardium.20,21

Suppression has not been associated with improved outcomes, as shown for class IC drugs in the landmark Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST),22 or in the amiodarone treatment arm of the Multicenter Automatic Defibrillator Implantation Trial II (MADIT-II).23 Therefore, treatment of ventricular ectopy in this patient population is usually symptom-driven unless there is hemodynamic intolerance, tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy, or a very high burden of PVCs in a patient who may be at risk of developing tachycardia-related cardiomyopathy. Antiarrhythmic drug treatment, when required, usually involves beta-blockers or class III medications such as sotalol or amiodarone.

Nonischemic dilated cardiomyopathy