User login

ABSTRACT

Blunt trauma to the anterior knee typically results in a contusion or fracture of the patella. Additionally, injury to the extensor mechanism may come from a partial or full disruption of the patellar or quadriceps tendon. A professional baseball player suffered an injury to his knee after he collided with an outfield wall. Acute swelling in the suprapatellar soft tissues concealed a palpable defect, which initially was suspected to be an injury to the quadriceps tendon. Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee revealed an intact extensor mechanism; moreover, a fracture of the subcutaneous fat anterior to the quadriceps tendon was evident and diagnosed as a fat fracture.

Fat fracture is a rare diagnosis, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported diagnosis in a professional athlete. Conservative management including, but not limited to, range of motion exercises, hydrotherapy, and iontophoresis effectively treated the athlete’s injury.

Blunt trauma to the anterior knee can result in a contusion or fracture of the patella, subluxation of the patella, and injury to the quadriceps or patellar tendon. Typically, a contusion or non-displaced fracture of the patella clinically presents with a direct anterior effusion and point tenderness. A displaced fracture or tendon deficit typically has an extensor lag or weakness in extension. Fat fracture or traumatic lipomata has been previously described in 1 case of anterior knee pain after blunt injury.1

In this article, we present the case of a 32-year-old professional baseball player who suffered a blunt injury to his left knee after collision with the outfield wall and experienced both anterior and medial knee pain. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

A 32-year-old outfielder for a professional baseball team was attempting a catch in the outfield when his left knee collided with the padded outfield wall in a semiflexed position. The player was able to walk off the field in the middle of the inning; however, he then experienced increasing pain and was unable to return to play. He had no prior history of significant knee pain or injury. He complained only of pain, with no instability or sensation of catching or locking.

Continue to: Physical examination of the patient...

Physical examination of the patient revealed a grade 1+ swelling over the anterior aspect of the superior pole of the patella in the prepatellar region, as well as medially over the medial femoral condyle. However, there was no joint effusion. Palpation of the superomedial aspect of the patella elicited pain, but no medial joint line tenderness was elicited. Percussion testing to the patella was negative. There were no gross palpable defects in the extensor mechanism, and the patient was able to perform a straight leg raise against resistance with pain.

Mild coronal laxity of the patella was noted compared with that of the contralateral knee. Hip range of motion (ROM) was intact, but knee ROM was limited to 110° of flexion, with the complaint of anterior tightness at this position. He was able to fully extend his knee without symptoms. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress at both 0° and 30° of flexion. Lachman and anterior and posterior drawer tests were negative and symmetric to the contralateral knee. The McMurray test for meniscal pathology also was negative. Radiographs of the left knee were completed and were negative for fracture.

OUTCOMES

The initial clinical diagnosis was a patellar contusion and sprain of the medial retinaculum, and the athlete was treated with multiple modalities available in the athletic training room. Rehabilitation included activity modifications, passive and active ROM activities, quadriceps isometric exercises, and neuromuscular control activities. Adjunctive modalities included cryotherapy, hydrotherapy, topical hematoma cream, and iontophoresis.2 This aggressive treatment was continued for 3 days with decreased but persistent pain with running drills and limited knee flexion. Repeat clinical examination revealed a decreased swelling, but there was evidence of a clinically palpable defect anteriorly proximal to the patella. Although the patient could perform a straight leg raise, a partial injury to the quadriceps became plausible. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left knee was performed, owing to the persistent pain and limited flexion despite aggressive conservative management, as well as the palpable soft-tissue defect.

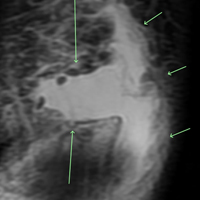

MRI was performed using a 3T (Tesla) system (GE Healthcare) with a GE Healthcare Precision 8-channel knee coil. Routine knee protocol imaging was performed to include the distal quadriceps tendon due to clinical concern for a quadriceps tear. Sagittal proton density and proton-density fat-saturated (PD FS), coronal T1 and PD FS, and axial T1 and PD FS sequences were acquired.

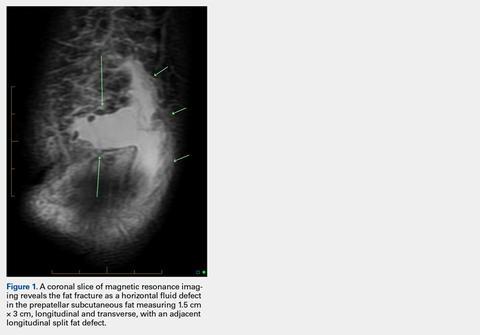

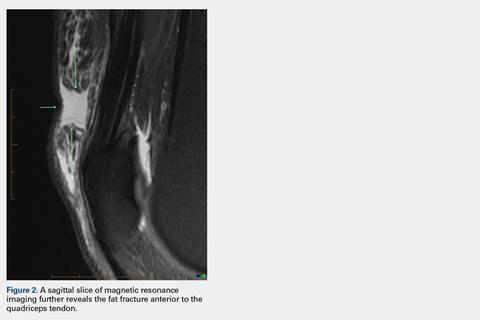

An acutely marginated, 1.5 cm × 3 cm, longitudinal and transverse fluid defect “crevasse” was identified at the midline in the prepatellar subcutaneous fat overlying the distal quadriceps tendon and corresponded to a clinically palpable abnormality (Figures 1, 2).

Continue to: These findings explained...

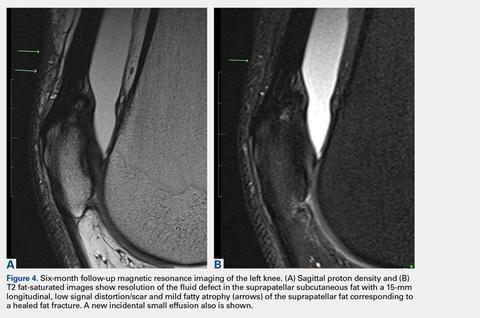

These findings explained the delayed course in resolution of symptoms. Over the next 48 hours, continued conservative management, as outlined above, led to the resolution of symptoms, and the athlete returned to play. At a 2-month follow-up, the athlete described normal function in his knee without any residual symptoms. He returned to play without any symptoms. At 6 months, the athlete underwent MRI of the same knee for an unrelated reason. MRI revealed a healed fat fracture with resolution of the fluid defect in the subcutaneous fat (Figures 4A, 4B).

DISCUSSION

A fat fracture was first described in 1972 in 12 cases of buttock fat fractures after blunt trauma.3 The authors explained that fat lobules are typically arranged in layers and supported by horizontal and vertical fibrous septa. Typical loads flatten the lobules and disperse the forces throughout the layer. However, abnormal loads to a local area disrupt the fat lobules and shear the septa, resulting in decreased integrity of the interface between the epidermis and the fascia.

However, the extremities typically have less adipose tissue than in the buttocks, and the anterior knee is prone to blunt trauma. A previous description of a fat fracture in the knee noted a palpable defect in the quadriceps tendon and an inability to perform a straight leg raise. Our case initially presented with swelling, which concealed any soft-tissue defect. Furthermore, a straight leg raise was always intact despite the fat fracture defect surfacing after anterior swelling subsided. However, the disparity in these 2 cases highlights the spectrum of injury that is possible, as well as the difficulty in diagnosing a fat fracture. The previous report used ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis and assess the integrity of adjacent musculotendinous structures. An ultrasound may be readily available in athletic training rooms.1 Of note, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature to report a fat fracture in a professional athlete and in baseball players. Furthermore, this case report describes an athlete who presented with anterior and medial knee pain. The edema from the fat fracture dispersed into the medial prepatellar bursa, which could be confused with edema from an injury to the medial-sided soft tissues.

Although these injuries do not require operative management, conservative measures may not be as effective as those in a patellar contusion or ligamentous sprain, and prolonged treatment may be necessary. Additionally, healthcare providers should be aware of this possible source of injury and counsel on an appropriate recovery time. Ideally, further recognition of such injuries can facilitate improved management and a faster return to activity.

1. Thomas RH, Holt MD, James SH, White PG. 'Fat fracture'—a physical sign mimicking tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(2):204-205.

2. Antich T, Randall CC, Westbrook RA, Morrissey MC, Brewster CE. Physical therapy treatment of knee extensor mechanism disorders: comparison of four treatment modalities*. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1986;8(5):255-259.

3. Meggitt BF, Wilson JN. The battered buttock syndrome—fat fractures. A report on a group of traumatic lipomata. Br J Surg. 1972;59(3):165-169.

ABSTRACT

Blunt trauma to the anterior knee typically results in a contusion or fracture of the patella. Additionally, injury to the extensor mechanism may come from a partial or full disruption of the patellar or quadriceps tendon. A professional baseball player suffered an injury to his knee after he collided with an outfield wall. Acute swelling in the suprapatellar soft tissues concealed a palpable defect, which initially was suspected to be an injury to the quadriceps tendon. Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee revealed an intact extensor mechanism; moreover, a fracture of the subcutaneous fat anterior to the quadriceps tendon was evident and diagnosed as a fat fracture.

Fat fracture is a rare diagnosis, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported diagnosis in a professional athlete. Conservative management including, but not limited to, range of motion exercises, hydrotherapy, and iontophoresis effectively treated the athlete’s injury.

Blunt trauma to the anterior knee can result in a contusion or fracture of the patella, subluxation of the patella, and injury to the quadriceps or patellar tendon. Typically, a contusion or non-displaced fracture of the patella clinically presents with a direct anterior effusion and point tenderness. A displaced fracture or tendon deficit typically has an extensor lag or weakness in extension. Fat fracture or traumatic lipomata has been previously described in 1 case of anterior knee pain after blunt injury.1

In this article, we present the case of a 32-year-old professional baseball player who suffered a blunt injury to his left knee after collision with the outfield wall and experienced both anterior and medial knee pain. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

A 32-year-old outfielder for a professional baseball team was attempting a catch in the outfield when his left knee collided with the padded outfield wall in a semiflexed position. The player was able to walk off the field in the middle of the inning; however, he then experienced increasing pain and was unable to return to play. He had no prior history of significant knee pain or injury. He complained only of pain, with no instability or sensation of catching or locking.

Continue to: Physical examination of the patient...

Physical examination of the patient revealed a grade 1+ swelling over the anterior aspect of the superior pole of the patella in the prepatellar region, as well as medially over the medial femoral condyle. However, there was no joint effusion. Palpation of the superomedial aspect of the patella elicited pain, but no medial joint line tenderness was elicited. Percussion testing to the patella was negative. There were no gross palpable defects in the extensor mechanism, and the patient was able to perform a straight leg raise against resistance with pain.

Mild coronal laxity of the patella was noted compared with that of the contralateral knee. Hip range of motion (ROM) was intact, but knee ROM was limited to 110° of flexion, with the complaint of anterior tightness at this position. He was able to fully extend his knee without symptoms. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress at both 0° and 30° of flexion. Lachman and anterior and posterior drawer tests were negative and symmetric to the contralateral knee. The McMurray test for meniscal pathology also was negative. Radiographs of the left knee were completed and were negative for fracture.

OUTCOMES

The initial clinical diagnosis was a patellar contusion and sprain of the medial retinaculum, and the athlete was treated with multiple modalities available in the athletic training room. Rehabilitation included activity modifications, passive and active ROM activities, quadriceps isometric exercises, and neuromuscular control activities. Adjunctive modalities included cryotherapy, hydrotherapy, topical hematoma cream, and iontophoresis.2 This aggressive treatment was continued for 3 days with decreased but persistent pain with running drills and limited knee flexion. Repeat clinical examination revealed a decreased swelling, but there was evidence of a clinically palpable defect anteriorly proximal to the patella. Although the patient could perform a straight leg raise, a partial injury to the quadriceps became plausible. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left knee was performed, owing to the persistent pain and limited flexion despite aggressive conservative management, as well as the palpable soft-tissue defect.

MRI was performed using a 3T (Tesla) system (GE Healthcare) with a GE Healthcare Precision 8-channel knee coil. Routine knee protocol imaging was performed to include the distal quadriceps tendon due to clinical concern for a quadriceps tear. Sagittal proton density and proton-density fat-saturated (PD FS), coronal T1 and PD FS, and axial T1 and PD FS sequences were acquired.

An acutely marginated, 1.5 cm × 3 cm, longitudinal and transverse fluid defect “crevasse” was identified at the midline in the prepatellar subcutaneous fat overlying the distal quadriceps tendon and corresponded to a clinically palpable abnormality (Figures 1, 2).

Continue to: These findings explained...

These findings explained the delayed course in resolution of symptoms. Over the next 48 hours, continued conservative management, as outlined above, led to the resolution of symptoms, and the athlete returned to play. At a 2-month follow-up, the athlete described normal function in his knee without any residual symptoms. He returned to play without any symptoms. At 6 months, the athlete underwent MRI of the same knee for an unrelated reason. MRI revealed a healed fat fracture with resolution of the fluid defect in the subcutaneous fat (Figures 4A, 4B).

DISCUSSION

A fat fracture was first described in 1972 in 12 cases of buttock fat fractures after blunt trauma.3 The authors explained that fat lobules are typically arranged in layers and supported by horizontal and vertical fibrous septa. Typical loads flatten the lobules and disperse the forces throughout the layer. However, abnormal loads to a local area disrupt the fat lobules and shear the septa, resulting in decreased integrity of the interface between the epidermis and the fascia.

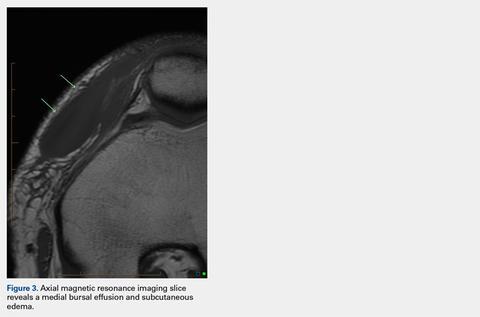

However, the extremities typically have less adipose tissue than in the buttocks, and the anterior knee is prone to blunt trauma. A previous description of a fat fracture in the knee noted a palpable defect in the quadriceps tendon and an inability to perform a straight leg raise. Our case initially presented with swelling, which concealed any soft-tissue defect. Furthermore, a straight leg raise was always intact despite the fat fracture defect surfacing after anterior swelling subsided. However, the disparity in these 2 cases highlights the spectrum of injury that is possible, as well as the difficulty in diagnosing a fat fracture. The previous report used ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis and assess the integrity of adjacent musculotendinous structures. An ultrasound may be readily available in athletic training rooms.1 Of note, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature to report a fat fracture in a professional athlete and in baseball players. Furthermore, this case report describes an athlete who presented with anterior and medial knee pain. The edema from the fat fracture dispersed into the medial prepatellar bursa, which could be confused with edema from an injury to the medial-sided soft tissues.

Although these injuries do not require operative management, conservative measures may not be as effective as those in a patellar contusion or ligamentous sprain, and prolonged treatment may be necessary. Additionally, healthcare providers should be aware of this possible source of injury and counsel on an appropriate recovery time. Ideally, further recognition of such injuries can facilitate improved management and a faster return to activity.

ABSTRACT

Blunt trauma to the anterior knee typically results in a contusion or fracture of the patella. Additionally, injury to the extensor mechanism may come from a partial or full disruption of the patellar or quadriceps tendon. A professional baseball player suffered an injury to his knee after he collided with an outfield wall. Acute swelling in the suprapatellar soft tissues concealed a palpable defect, which initially was suspected to be an injury to the quadriceps tendon. Magnetic resonance imaging of the knee revealed an intact extensor mechanism; moreover, a fracture of the subcutaneous fat anterior to the quadriceps tendon was evident and diagnosed as a fat fracture.

Fat fracture is a rare diagnosis, and to the best of our knowledge, this is the first reported diagnosis in a professional athlete. Conservative management including, but not limited to, range of motion exercises, hydrotherapy, and iontophoresis effectively treated the athlete’s injury.

Blunt trauma to the anterior knee can result in a contusion or fracture of the patella, subluxation of the patella, and injury to the quadriceps or patellar tendon. Typically, a contusion or non-displaced fracture of the patella clinically presents with a direct anterior effusion and point tenderness. A displaced fracture or tendon deficit typically has an extensor lag or weakness in extension. Fat fracture or traumatic lipomata has been previously described in 1 case of anterior knee pain after blunt injury.1

In this article, we present the case of a 32-year-old professional baseball player who suffered a blunt injury to his left knee after collision with the outfield wall and experienced both anterior and medial knee pain. The patient provided written informed consent for print and electronic publication of this case report.

CASE

A 32-year-old outfielder for a professional baseball team was attempting a catch in the outfield when his left knee collided with the padded outfield wall in a semiflexed position. The player was able to walk off the field in the middle of the inning; however, he then experienced increasing pain and was unable to return to play. He had no prior history of significant knee pain or injury. He complained only of pain, with no instability or sensation of catching or locking.

Continue to: Physical examination of the patient...

Physical examination of the patient revealed a grade 1+ swelling over the anterior aspect of the superior pole of the patella in the prepatellar region, as well as medially over the medial femoral condyle. However, there was no joint effusion. Palpation of the superomedial aspect of the patella elicited pain, but no medial joint line tenderness was elicited. Percussion testing to the patella was negative. There were no gross palpable defects in the extensor mechanism, and the patient was able to perform a straight leg raise against resistance with pain.

Mild coronal laxity of the patella was noted compared with that of the contralateral knee. Hip range of motion (ROM) was intact, but knee ROM was limited to 110° of flexion, with the complaint of anterior tightness at this position. He was able to fully extend his knee without symptoms. The knee was stable to varus and valgus stress at both 0° and 30° of flexion. Lachman and anterior and posterior drawer tests were negative and symmetric to the contralateral knee. The McMurray test for meniscal pathology also was negative. Radiographs of the left knee were completed and were negative for fracture.

OUTCOMES

The initial clinical diagnosis was a patellar contusion and sprain of the medial retinaculum, and the athlete was treated with multiple modalities available in the athletic training room. Rehabilitation included activity modifications, passive and active ROM activities, quadriceps isometric exercises, and neuromuscular control activities. Adjunctive modalities included cryotherapy, hydrotherapy, topical hematoma cream, and iontophoresis.2 This aggressive treatment was continued for 3 days with decreased but persistent pain with running drills and limited knee flexion. Repeat clinical examination revealed a decreased swelling, but there was evidence of a clinically palpable defect anteriorly proximal to the patella. Although the patient could perform a straight leg raise, a partial injury to the quadriceps became plausible. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the left knee was performed, owing to the persistent pain and limited flexion despite aggressive conservative management, as well as the palpable soft-tissue defect.

MRI was performed using a 3T (Tesla) system (GE Healthcare) with a GE Healthcare Precision 8-channel knee coil. Routine knee protocol imaging was performed to include the distal quadriceps tendon due to clinical concern for a quadriceps tear. Sagittal proton density and proton-density fat-saturated (PD FS), coronal T1 and PD FS, and axial T1 and PD FS sequences were acquired.

An acutely marginated, 1.5 cm × 3 cm, longitudinal and transverse fluid defect “crevasse” was identified at the midline in the prepatellar subcutaneous fat overlying the distal quadriceps tendon and corresponded to a clinically palpable abnormality (Figures 1, 2).

Continue to: These findings explained...

These findings explained the delayed course in resolution of symptoms. Over the next 48 hours, continued conservative management, as outlined above, led to the resolution of symptoms, and the athlete returned to play. At a 2-month follow-up, the athlete described normal function in his knee without any residual symptoms. He returned to play without any symptoms. At 6 months, the athlete underwent MRI of the same knee for an unrelated reason. MRI revealed a healed fat fracture with resolution of the fluid defect in the subcutaneous fat (Figures 4A, 4B).

DISCUSSION

A fat fracture was first described in 1972 in 12 cases of buttock fat fractures after blunt trauma.3 The authors explained that fat lobules are typically arranged in layers and supported by horizontal and vertical fibrous septa. Typical loads flatten the lobules and disperse the forces throughout the layer. However, abnormal loads to a local area disrupt the fat lobules and shear the septa, resulting in decreased integrity of the interface between the epidermis and the fascia.

However, the extremities typically have less adipose tissue than in the buttocks, and the anterior knee is prone to blunt trauma. A previous description of a fat fracture in the knee noted a palpable defect in the quadriceps tendon and an inability to perform a straight leg raise. Our case initially presented with swelling, which concealed any soft-tissue defect. Furthermore, a straight leg raise was always intact despite the fat fracture defect surfacing after anterior swelling subsided. However, the disparity in these 2 cases highlights the spectrum of injury that is possible, as well as the difficulty in diagnosing a fat fracture. The previous report used ultrasound to confirm the diagnosis and assess the integrity of adjacent musculotendinous structures. An ultrasound may be readily available in athletic training rooms.1 Of note, to the best of our knowledge, this is the first case in the literature to report a fat fracture in a professional athlete and in baseball players. Furthermore, this case report describes an athlete who presented with anterior and medial knee pain. The edema from the fat fracture dispersed into the medial prepatellar bursa, which could be confused with edema from an injury to the medial-sided soft tissues.

Although these injuries do not require operative management, conservative measures may not be as effective as those in a patellar contusion or ligamentous sprain, and prolonged treatment may be necessary. Additionally, healthcare providers should be aware of this possible source of injury and counsel on an appropriate recovery time. Ideally, further recognition of such injuries can facilitate improved management and a faster return to activity.

1. Thomas RH, Holt MD, James SH, White PG. 'Fat fracture'—a physical sign mimicking tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(2):204-205.

2. Antich T, Randall CC, Westbrook RA, Morrissey MC, Brewster CE. Physical therapy treatment of knee extensor mechanism disorders: comparison of four treatment modalities*. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1986;8(5):255-259.

3. Meggitt BF, Wilson JN. The battered buttock syndrome—fat fractures. A report on a group of traumatic lipomata. Br J Surg. 1972;59(3):165-169.

1. Thomas RH, Holt MD, James SH, White PG. 'Fat fracture'—a physical sign mimicking tendon rupture. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83(2):204-205.

2. Antich T, Randall CC, Westbrook RA, Morrissey MC, Brewster CE. Physical therapy treatment of knee extensor mechanism disorders: comparison of four treatment modalities*. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1986;8(5):255-259.

3. Meggitt BF, Wilson JN. The battered buttock syndrome—fat fractures. A report on a group of traumatic lipomata. Br J Surg. 1972;59(3):165-169.

TAKE-HOME POINTS

- A fat fracture should be considered in the setting of a blunt injury to the anterior knee when a palpable soft-tissue defect is observed and the extensor mechanism is clinically intact.

- An ultrasound or MRI can assist in making the diagnosis, which can aid in guiding the patient with management and in determining the expected duration of symptoms.

- Injuries to the anterior knee that may present as contusions but have a prolonged course of symptoms should not be overlooked.