User login

Cutaneous granulomatous diseases encompass many entities that are skin-limited or systemic. The prototypical cutaneous granuloma is a painless, rounded, well-defined, red-pink or flesh-colored papule1 and is smooth, owing to minimal epidermal involvement. Examples of conditions that present with such lesions include granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD), granulomatous rosacea (GR), lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and papular sarcoidosis. These entities commonly are seen on the face and can be a source of distress to patients when they are extensive. Several reports have raised the possibility that these conditions lie on a spectrum.2-4 We present 2 cases of patients with facial papular granulomas, discuss potential causes of the lesions, review historical aspects from the literature, and highlight the challenges that these lesions can pose to the clinician.

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 10-year-old Ethiopian girl with a history of atopic dermatitis presented with a facial rash of 4 months’ duration. Her pediatrician initially treated the rash as pityriasis alba and prescribed hydrocortisone cream. Two months into treatment, the patient developed an otherwise asymptomatic, unilateral, papular dermatosis on the right cheek. She subsequently was switched to treatment with benzoyl peroxide and topical clindamycin, which she had been using for 2 months with no improvement at the time of the current presentation. The lesions then spread bilaterally and periorally.

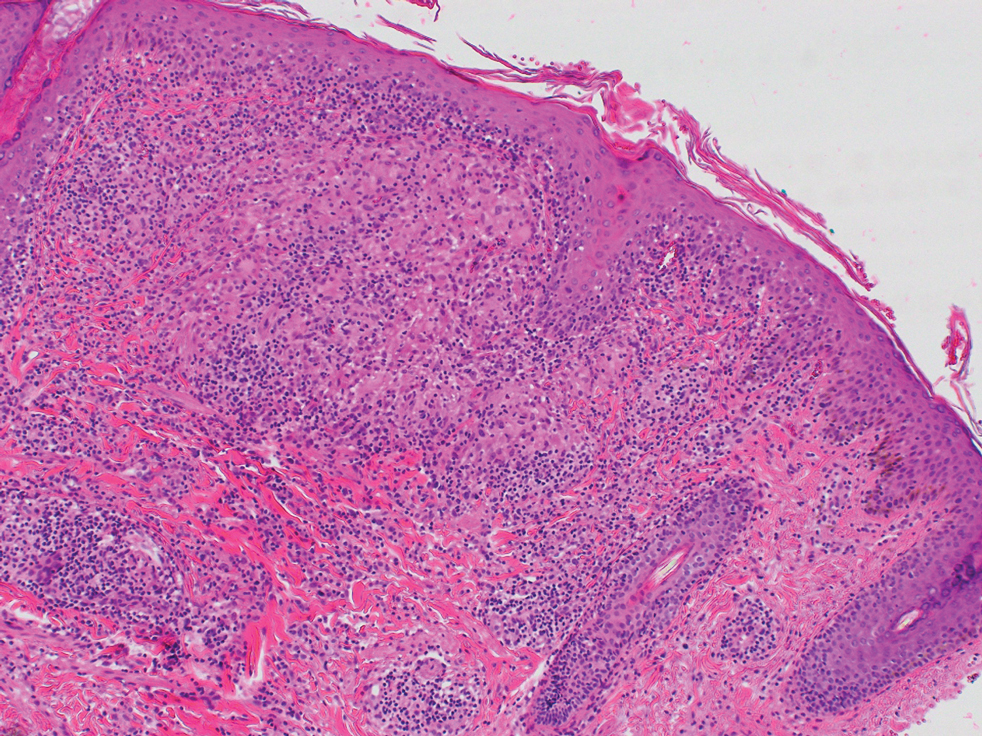

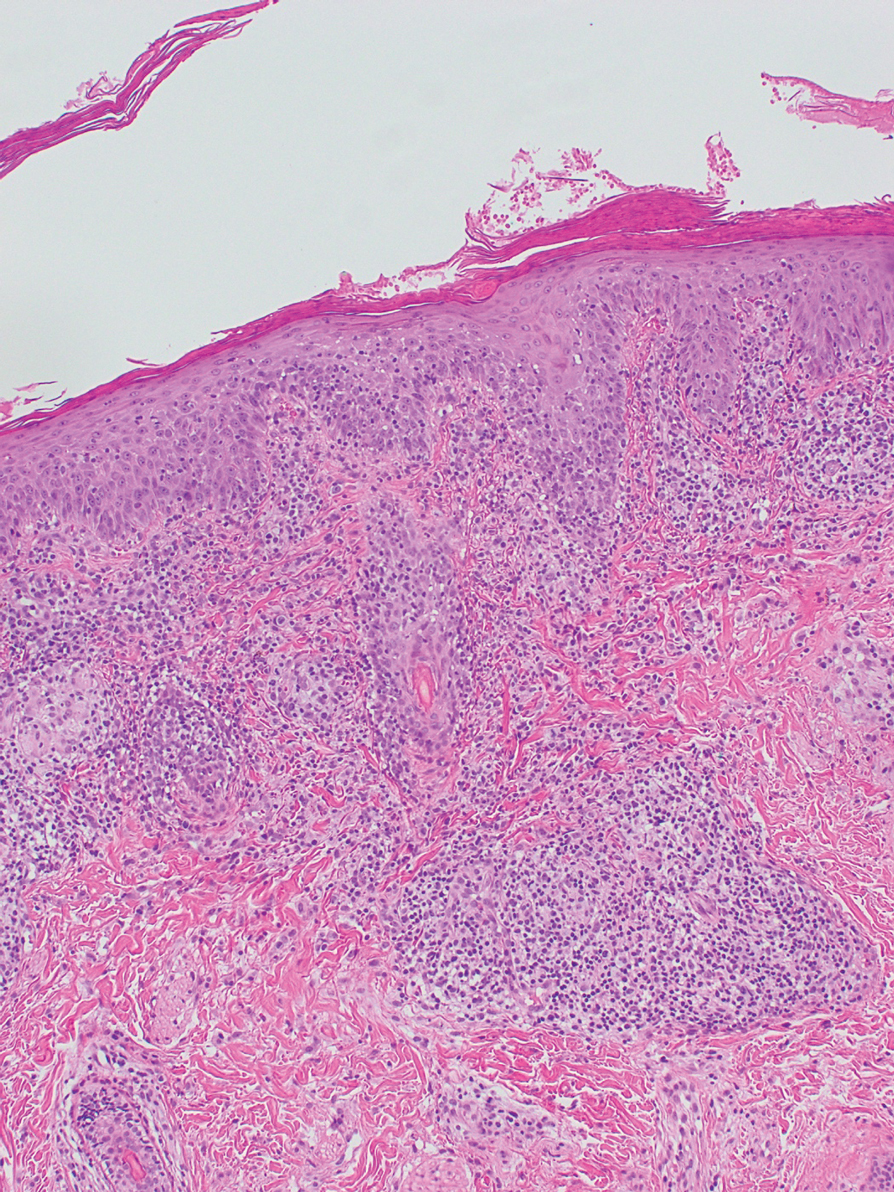

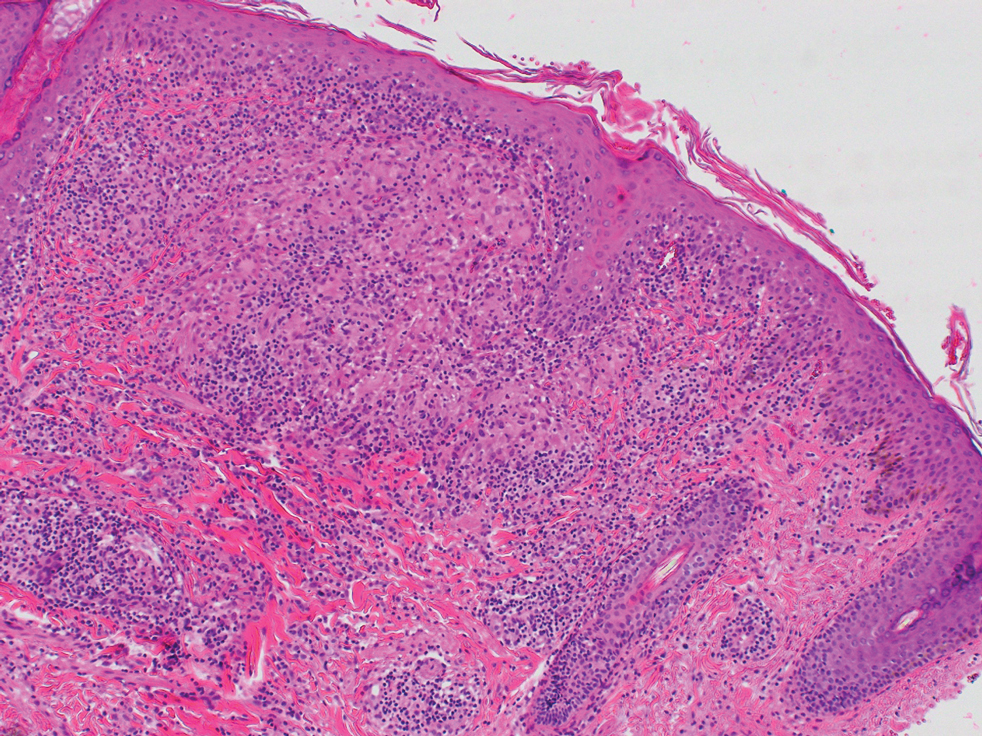

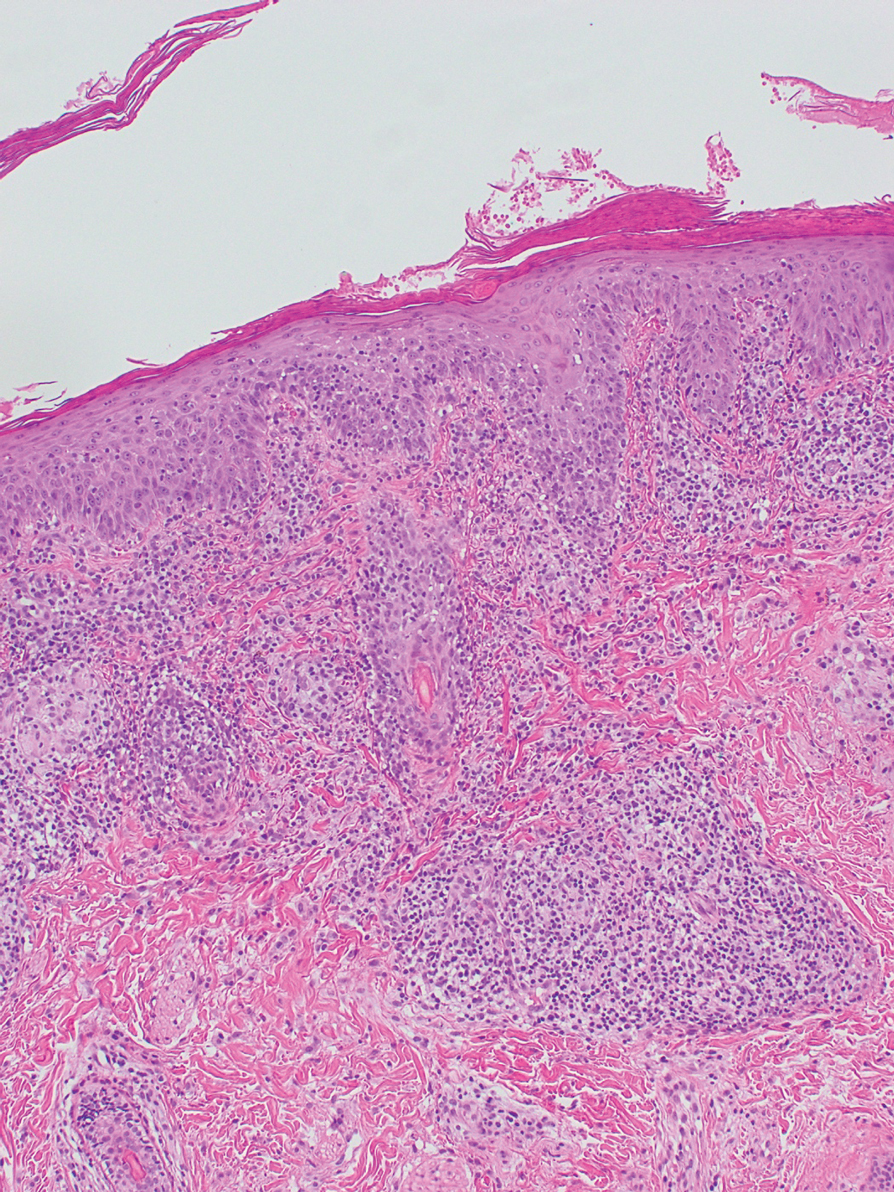

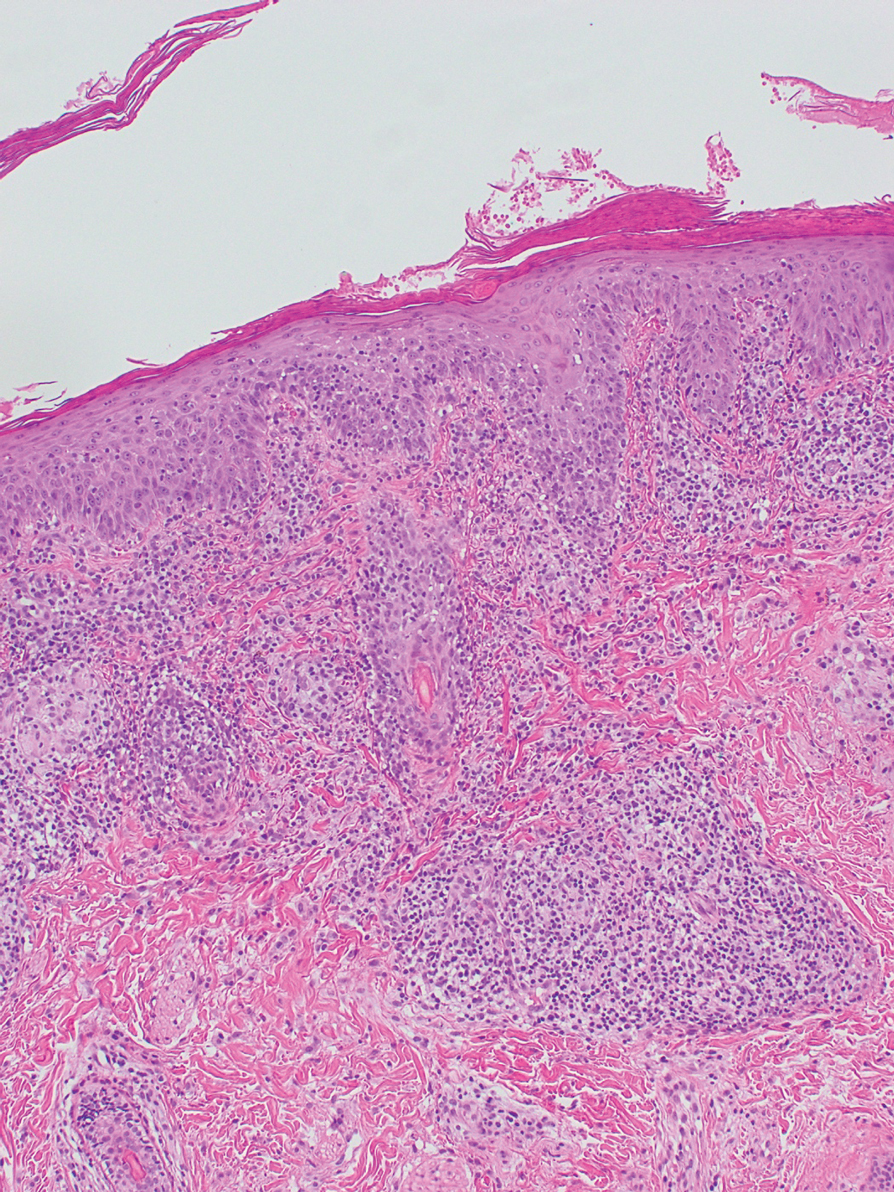

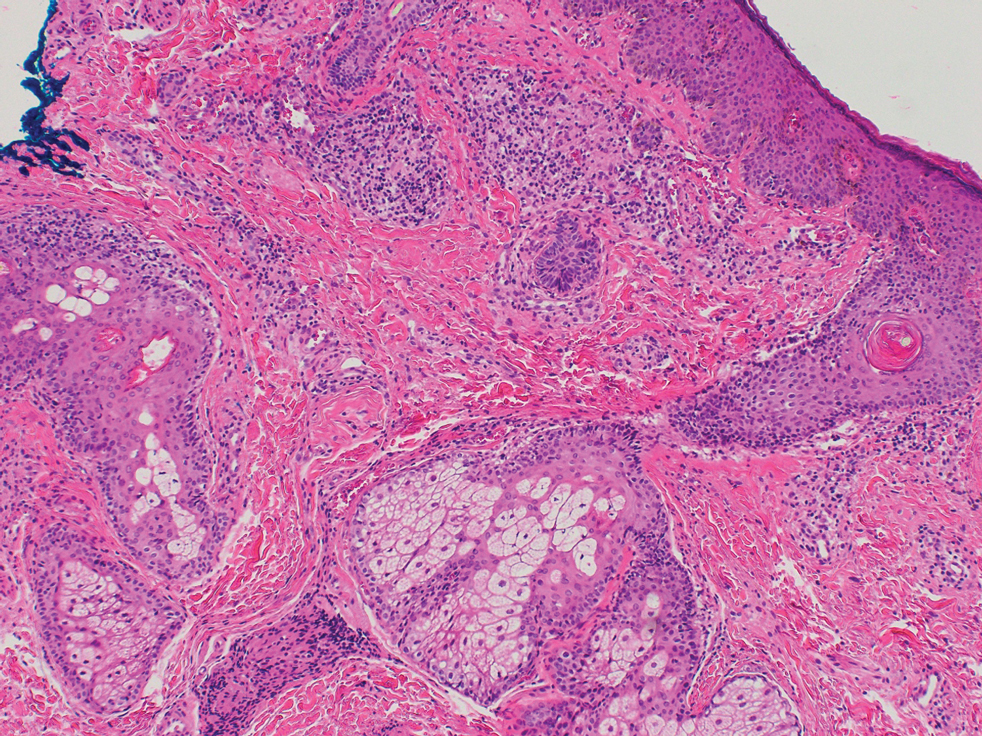

At the current presentation, physical examination demonstrated fine, diffuse, follicular-based, flesh-colored papules over both cheeks, the right side of the nose, and the perioral region (Figure 1). A biopsy of a papular lesion from the right cheek revealed well-formed, noncaseating granulomas in the superficial and mid dermis with an associated lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). No organisms were identified on acid-fast, Fite, or periodic acid–Schiff staining. A tuberculin skin test was negative. A chest radiograph showed small calcified hilar lymph nodes bilaterally. Pulmonary function tests were unremarkable. Calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal.

The patient denied any fever, chills, hemoptysis, cough, dyspnea, lymphadenopathy, scleral or conjunctival pain or erythema, visual disturbances, or arthralgias. Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was started with minimal improvement after 5 months. Methotrexate 20 mg once weekly was then added. Topical fluocinonide 0.05% also was started at this time, as the patient had required several prednisone tapers over the past 3 months for symptomatic relief. The lesions improved minimally after 5 more months of treatment, at which time she had developed inflammatory papules, pustules, and open comedones in the same areas as well as the glabella.

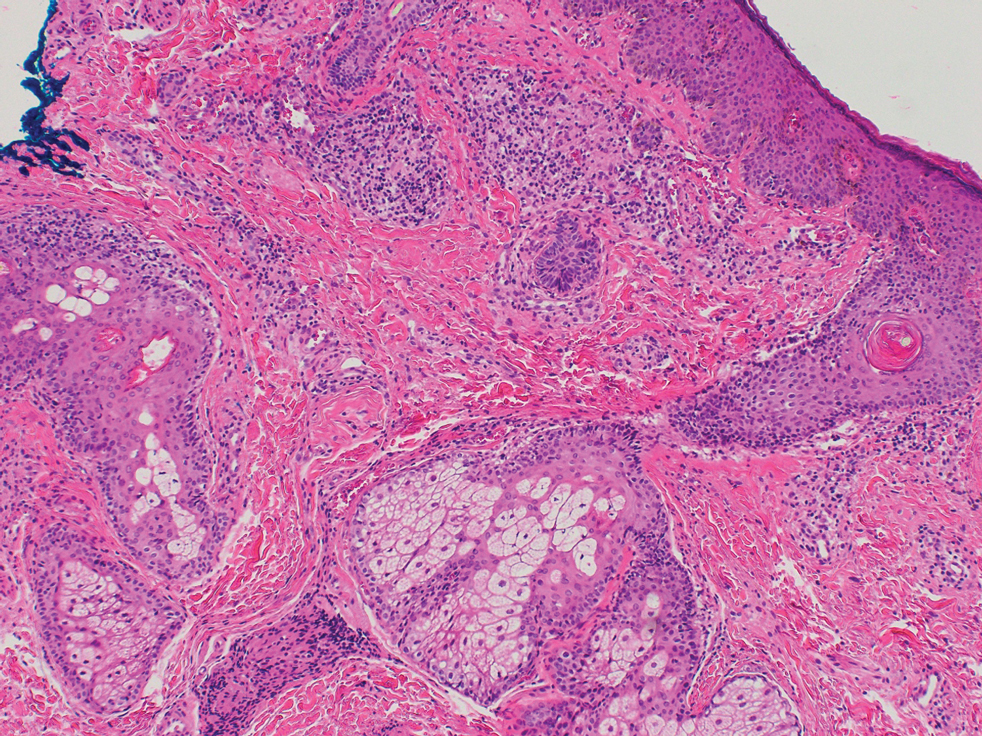

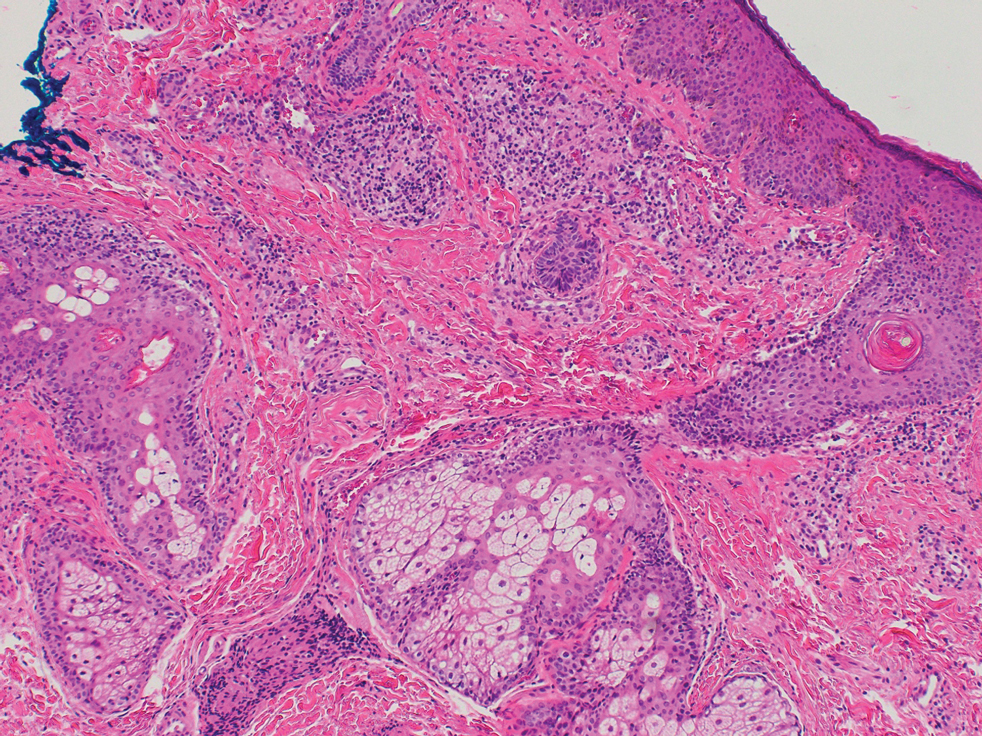

Repeat biopsy of a papular lesion demonstrated noncaseating granulomas and an associated chronic lymphocytic infiltrate in a follicular and perifollicular distribution (Figure 3). Biopsy of a pustule demonstrated acute Demodex folliculitis. Fluocinonide was stopped, and anti-mite therapy with ivermectin, permethrin cream 5%, and selenium sulfide lotion 2.5% was started, with good response from the pustular lesions.

The patient continued taking methotrexate 20 mg once weekly during this time, with improvement in the papular lesions. She discontinued methotrexate after 12 months with complete resolution. At follow-up 12 months after stopping the methotrexate (roughly 2 years after initial presentation), she showed sustained resolution, with small pitted scars on both cheeks and the nasal tip.

Patient 2—A 33-year-old Ethiopian woman presented with a facial rash of 15 years’ duration. The lesions had been accumulating slowly and were asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed multiple follicular-based, flesh-colored, and erythematous papules on the cheeks, chin, perioral area, and forehead (Figure 4). There were no pustules or telangiectasias. Treatment with tretinoin cream 0.05% for 6 months offered minimal relief.

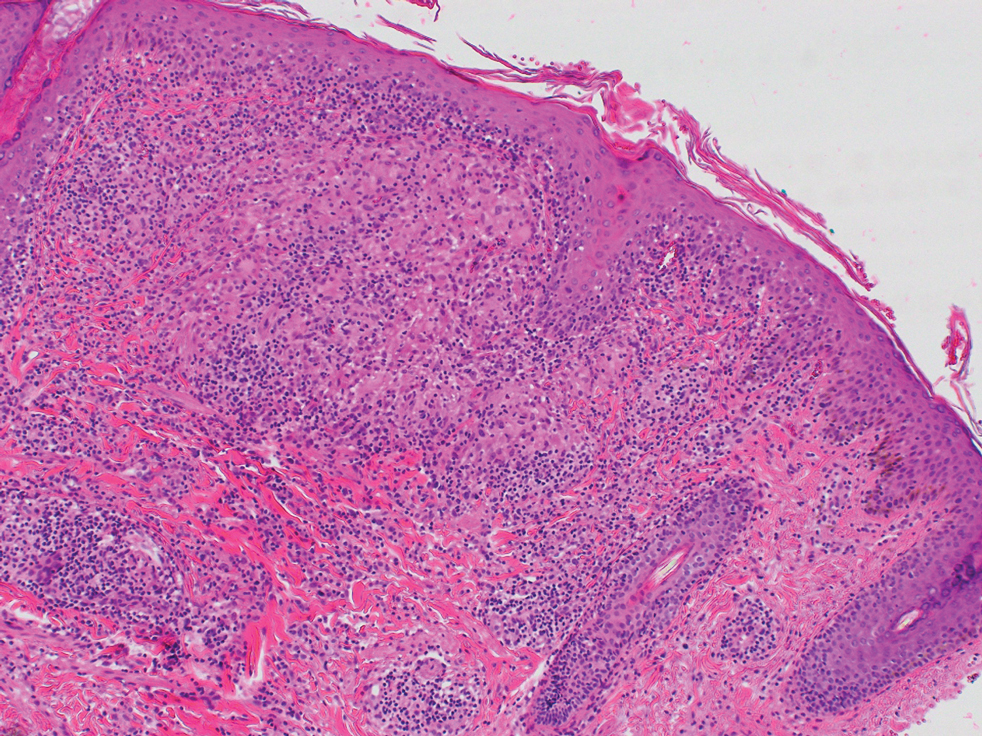

Biopsy of a papule from the left mandible showed superficial vascular telangiectasias, noncaseating granulomas comprising epithelioid histiocytes and lymphocytes in the superficial dermis, and a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 5). No organisms were identified on Fite or Gomori methenamine silver staining.

Comment

The first step in differentiating cutaneous granulomatous lesions should be to distinguish infectious from noninfectious causes.1 Noninfectious cutaneous granulomas can appear nearly anywhere; however, certain processes have a predilection for the face, including GPD, GR, LMDF, and papular sarcoidosis.5-7 These conditions generally present with papular granulomas with features as described above.

Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis—In 1970, Gianotti and colleagues8 briefly described the first possible cases of GPD in 5 children. The eruption comprised numerous yellow, dome-shaped papules in a mostly perioral distribution. Tuberculin and the Kveim tests were nonreactive; histopathology was described as sarcoid-type and not necessarily follicular or perifollicular.8 In 1974, Marten et al9 described 22 Afro-Caribbean children with flesh-colored, papular eruptions on the face that did not show histologic granulomatous changes but were morphologically similar to the reports by Gianotti et al.8 By 1989, Frieden and colleagues10 described this facial eruption as “granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children”. Additionally, the investigators observed granulomatous infiltrates in a perifollicular distribution and suggested follicular disruption as a possible cause. It was clear from the case discussions that these eruptions were not uncommonly diagnosed as papular sarcoidosis.10 The following year, Williams et al11 reported 5 cases of similar papular eruptions in 5 Afro-Caribbean children, coining the term facial Afro-Caribbean eruption.11 Knautz and Lesher12 referred to this entity as “childhood GPD” in 1996 to avoid limiting the diagnosis to Afro-Caribbean patients and to a perioral distribution; this is the most popular current terminology.12 Since then, reports of extrafacial involvement and disease in adults have been published.13,14

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis often is seen in the perinasal, periocular, and perioral regions of the face.2 It is associated with topical steroid exposure.5 Histologically, noncaseating granulomas around the upper half of undisrupted hair follicles with a lymphocytic infiltrate are typical.13 Treatment should begin with cessation of any topical steroids; first-line agents are oral tetracycline or macrolide antibiotics.5 These agents can be used alone or in combination with topical erythromycin, metronidazole, or sulfur-based lotions.13 Rarely, GPD presents extrafacially.13 Even so, it usually resolves within 2 weeks to 6 months, especially with therapy; scarring is unusual.5,13,15

Granulomatous Rosacea—A report in the early 20th century described patients with tuberculoid granulomas resembling papular rosacea; the initial belief was that this finding represented a rosacealike tuberculid eruption.5 However, this belief was questioned by Snapp,16 among others, who demonstrated near universal lack of reactivity to tuberculin among 20 of these patients in 1949; more recent evidence has substantiated these findings.17 Still, Snapp16 postulated that these rosacealike granulomatous lesions were distinct from classic rosacea because they lacked vascular symptoms and pustules and were recalcitrant to rosacea treatment modalities.

In 1970, Mullanax and colleagues18 introduced the term granulomatous rosacea, reiterating that this entity was not tuberculous. They documented papulopustular lesions as well as telangiectasias, raising the possibility that GR does overlap with acne rosacea. More recent studies have established the current theory that GR is a histologic variant of acne rosacea because, in addition to typical granulomatous papules, its microscopic features can be seen across subtypes of acne rosacea.19,20

Various causes have been proposed for GR. Demodex mites have been reported in association with GR for nearly 30 years.19,20 In the past 10 years, molecular studies have started to define the role of metalloproteinases, UV radiation, and cutaneous peptides in the pathogenesis of acne rosacea and GR.21,22

Granulomatous rosacea typically is seen in middle-aged women.20,23 Hallmarks of rosacea, such as facial erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, pustules, and rhinophyma, are not always present in GR.5,20,23 Lesions usually are distributed around the central face, although extension to the cheeks, total facial involvement, and extrafacial lesions are possible.5,20 Histologically, perifollicular and follicular-based noncaseating granulomas with dilatation of the dermal papillary vasculature are seen.17,23 As a whole, rosacea is comparatively uncommon in dark-skinned patients; when it does occur, GR is a frequent presentation.24

First-line treatment for GR is tetracycline antibiotics.5 Unresponsive cases have been treated—largely anecdotally—with topical modalities (eg, metronidazole, steroids, immunomodulators), systemic agents (eg, dapsone, erythromycin, isotretinoin), and other therapies.5 Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a chronic course.5,23

Lupus Miliaris Disseminatus Faciei—Classic LMDF demonstrates caseating perifollicular granulomas histologically.6,17,25 Lesions tend to appear on the central face, particularly the eyelids, and can be seen extrafacially.3,6,25,26 Although LMDF originally was categorized as a tuberculid eruption, this no longer is thought to be the case.27 It is now regarded by some as a variant of GR25; however, LMDF responds poorly to tetracyclines, is more common in males, and lacks rosacealike vascular abnormalities, leading some to question this association.3,6,17 In the past 20 years, some have proposed renaming LMDF to better reflect its clinical course and to consider it independent of tuberculosis and GR.28 It usually resolves spontaneously after 1 to 3 years, leaving pitted scars.3,6

Papular Sarcoidosis—The first potential documented case of sarcoidosis was by Hutchinson29 in 1869 in a patient seen in London. The author labeled purple plaques on the index patient’s legs and hands as “livid papillary psoriasis.” In 1889, Besnier30 described a patient with violaceous swellings on the nose, ears, and fingers, which he called “lupus pernio”; his contemporary, Tenneson,31 published a case of lupus pernio and described its histologic profile as comprising epithelioid cells and giant cells. It was not until 1899 that the term sarkoid was used to describe these cutaneous lesions by Boeck,32 who thought they were reminiscent of sarcoma. In 1915, Kuznitsky and Bittorf33 described a patient with cutaneous lesions histologically consistent with Boeck’s sarkoid but additionally with hilar lymphadenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates. Around 1916 or 1917, Schaumann34 described patients with cutaneous lesions and additionally with involvement of pulmonary, osseous, hepatosplenic, and tonsillar tissue. These reports are among the first to recognize the multisystemic nature of sarcoidosis. The first possible case of childhood sarcoidosis might have been reported by Osler35 in the United States in 1898.

In the past century or so, an ongoing effort by researchers has focused on identifying etiologic triggers for sarcoidosis. Microbial agents have been considered in this role, with Mycobacterium and Propionibacterium organisms the most intensively studied; the possibility that foreign material contributes to the formation of granulomas also has been raised.36 Current models of the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis involve an interplay between the immune system in genetically predisposed patients and an infection that leads to a hyperimmune type 1 T–helper cell response that clears the infection but not antigens generated by the microbes and the acute host response, including proteins such as serum amyloid A and vimentin.36,37 These antigens aggregate and serve as a nidus for granuloma formation and maintenance long after infection has resolved.

Cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis include macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio, as well as lesions arising within scars or tattoos, with many less common presentations.7,38 Papular sarcoidosis is common on the face but also can involve the extremities.4,7 Strictly, at least 2 organ systems must be involved to diagnose sarcoidosis, but this is debatable.4,7 Among 41 patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, 24 (58.5%) had systemic disease; cutaneous lesions were the presenting sign in 87.5% (21/24) of patients.38 Histologic analysis, regardless of the lesion, usually shows noncaseating so-called “naked” granulomas, which have minimal lymphocytic infiltrate associated with the epithelioid histiocytes.38,39 Perifollicular granulomas are possible but unusual.40

Treatment depends on the extent of cutaneous and systemic involvement. Pharmacotherapeutic modalities include topical steroids, immunomodulators, and retinoids; systemic immunomodulators and immunosuppressants; and biologic agents.7 Isolated cutaneous sarcoidosis, particularly the papular variant, usually is associated with acute disease lasting less than 2 years, with resolution of skin lesions.7,38 That said, a recent report suggested that cutaneous sarcoidosis can progress to multisystemic disease as long as 7 years after the initial diagnosis.41

Clinical and Histologic Overlap—Despite this categorization of noninfectious facial granulomatous conditions, each has some clinical and histologic overlap with the others, which must be considered when encountering a granulomatous facial dermatosis. Both GPD and GR tend to present with lesions near the eyes, mouth, and nose, although GR can extend to lateral aspects of the face, below the mandible, and the forehead and has different demographic features.15,20,23 Granulomas in both GPD and GR generally are noncaseating and form in a follicular or perifollicular distribution within the dermis.2,15,23 Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei and GR share a similar facial distribution in some cases.17,20 Even papular cutaneous sarcoidosis has masqueraded as GR clinically and histologically.4

Diagnostic and Treatment Difficulty—Our cases illustrate the range of difficulty in evaluating and managing patients with facial papular granulomas. On one hand, our adult patient’s clinical and histologic findings were highly consistent with GR; on the other hand, our younger patient had clinicopathologic features of both sarcoidosis and GPD at varying times. Both conditions are more common in dark-skinned patients.11,42

Juvenile sarcoidosis is comparatively rare, with a reported annual incidence of 0.22 to 0.27 for every 100,000 children younger than 15 years; however, juvenile sarcoidosis commonly presents around 8 to 15 years of age.43

It is unusual for sarcoid granulomas to be isolated to the skin, much less to the face.4,7,43,44 Patient 1 initially presented in this manner and lacked convincing laboratory or radiographic evidence of systemic sarcoidosis. Bilateral hilar calcifications in sarcoidosis are more typical among adults after 5 to 20 years; there were no signs or symptoms of active infection that could account for the pulmonary and cutaneous lesions.45

The presence of perifollicular granulomas with associated lymphocytic infiltrates on repeat biopsy, coupled with the use of topical steroids, made it difficult to rule out a contribution by GPD to her clinical course. That her lesions resolved with pitted scarring while she was taking methotrexate and after topical steroids had been stopped could be the result of successful management or spontaneous resolution of her dermatosis; both papular sarcoidosis and GPD tend to have a self-limited course.7,13

Conclusion

We present 2 cases of papular facial granulomas in patients with similar skin types who had different clinical courses. Evaluation of such lesions remains challenging given the similarity between specific entities that present in this manner. Certainly, it is reasonable to consider a spectrum upon which all of these conditions fall, in light of the findings of these cases and those reported previously.

- Beretta-Piccoli BT, Mainetti C, Peeters M-A, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8666-8

- Lucas CR, Korman NJ, Gilliam AC. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis: a variant of granulomatous rosacea in children? J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:115-118. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07088

- van de Scheur MR, van der Waal RIF, Starink TM. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei: a distinctive rosacea-like syndrome and not a granulomatous form of rosacea. Dermatology. 2003;206:120-123. doi:10.1159/000068457

- Simonart T, Lowy M, Rasquin F, et al. Overlap of sarcoidosis and rosacea. Dermatology. 1997;194:416-418. doi:10.1159/000246165

- Lee GL, Zirwas MJ. Granulomatous rosacea and periorificial dermatitis: controversies and review of management. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:447-455. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.009

- Michaels JD, Cook-Norris RH, Lehman JS, et al. Adult with papular eruption of the central aspect of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:410-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.039

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;38:685-702. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.010

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Benelli MG, et al. Particulière dermatite peri-orale infantile. observations sur 5 cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1970;77:341.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual papular and acneiform facial eruption in the negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb13083.x

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Williams HC, Ashworth J, Pembroke AC, et al. FACE—facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:163-166. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1990.tb02063.x

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL Jr. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1996.tb01419.x

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.10.1354

- Vincenzi C, Parente G, Tosti A. Perioral granulomatous dermatitis: two cases treated with clarithromycin. J Dermatol Treat. 2000;11:57-61.

- Kim YJ, Shin JW, Lee JS, et al. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:386-388. doi:10.5021/ad.2011.23.3.386

- Snapp RH. Lewandowsky’s rosacea-like eruption; a clinical study. J Invest Dermatol. 1949;13:175-190. doi:10.1038/jid.1949.86

- Chougule A, Chatterjee D, Sethi S, et al. Granulomatous rosacea versus lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei—2 faces of facial granulomatous disorder: a clinicohistological and molecular study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:819-823. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001243

- Mullanax MG, Kierland RR. Granulomatous rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:206-211.

- Sánchez JL, Berlingeri-Ramos AC, Dueño DV. Granulomatous rosacea. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:6-9. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815bc191

- Helm KF, Menz J, Gibson LE, et al. A clinical and histopathologic study of granulomatous rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1038-1043. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70304-k

- Kanada KN, Nakatsuji T, Gallo RL. Doxycycline indirectly inhibits proteolytic activation of tryptic kallikrein-related peptidases and activation of cathelicidin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1435-1442. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.14

- Jang YH, Sim JH, Kang HY, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of matrix metalloproteinases in the granulomatous rosacea compared with the non-granulomatous rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:544-548. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03825.x

- Khokhar O, Khachemoune A. A case of granulomatous rosacea: sorting granulomatous rosacea from other granulomatous diseases that affect the face. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:6.

- Rosen T, Stone MS. Acne rosacea in blacks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:70-73. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70173-x

- Adams AK, Davis JL, Davis MDP, et al. What is your diagnosis? granulomatous rosacea (lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, acne agminata). Cutis. 2008;82:103-112.

- Shitara A. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:542-544. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb04206.x

- Hodak E, Trattner A, Feuerman H, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei—the DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is not detectable in active lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:614-619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03797.x

- Skowron F, Causeret AS, Pabion C, et al. F.I.GU.R.E.: facial idiopathic granulomas with regressive evolution. Dermatology. 2000;201:287-289. doi:10.1159/000051539

- Hutchinson J. Case of livid papillary psoriasis. In: London J, Churchill A, eds. Illustrations of Clinical Surgery. J&A Churchill; 1877:42-43.

- Besnier E. Lupus pernio of the face [in French]. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris). 1889;10:33-36.

- Tenneson H. Lupus pernio. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris). 1889;10:333-336.

- Boeck C. Multiple benign sarkoid of the skin [in Norwegian]. Norsk Mag Laegevidensk. 1899;14:1321-1334.

- Kuznitsky E, Bittorf A. Sarkoid mit beteiligung innerer organe. Münch Med Wochenschr. 1915;62:1349-1353.

- Schaumann J. Etude sur le lupus pernio et ses rapports avec les sarcoides et la tuberculose. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr. 1916-1917;6:357-373.

- Osler W. On chronic symmetrical enlargement of the salivary and lacrimal glands. Am J Med Sci. 1898;115:27-30.

- Chen ES, Moller DR. Etiologies of sarcoidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:6-18. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8481-z

- Eberhardt C, Thillai M, Parker R, et al. Proteomic analysis of Kveim reagent identifies targets of cellular immunity in sarcoidosis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170285. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170285

- Esteves TC, Aparicio G, Ferrer B, et al. Prognostic value of skin lesions in sarcoidosis: clinical and histopathological clues. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:556-562. doi:10.1684/ejd.2015.2666

- Cardoso JC, Cravo M, Reis JP, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: a histopathological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:678-682. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03153.x

- Mangas C, Fernández-Figueras M-T, Fité E, et al. Clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 32 cases of specific cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:772-777. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00563.x

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis. clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14218

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16. doi:10.1186/1546-0096-6-16

- Milman N, Hoffmann AL, Byg KE. Sarcoidosis in children. epidemiology in Danes, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:871-878. doi:10.1080/08035259875001366244. A, H, Yapıcı I. Isolated cutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:220.

- Scadding JG. The late stages of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Postgrad Med J. 1970;46:530-536. doi:10.1136/pgmj.46.538.530

Cutaneous granulomatous diseases encompass many entities that are skin-limited or systemic. The prototypical cutaneous granuloma is a painless, rounded, well-defined, red-pink or flesh-colored papule1 and is smooth, owing to minimal epidermal involvement. Examples of conditions that present with such lesions include granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD), granulomatous rosacea (GR), lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and papular sarcoidosis. These entities commonly are seen on the face and can be a source of distress to patients when they are extensive. Several reports have raised the possibility that these conditions lie on a spectrum.2-4 We present 2 cases of patients with facial papular granulomas, discuss potential causes of the lesions, review historical aspects from the literature, and highlight the challenges that these lesions can pose to the clinician.

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 10-year-old Ethiopian girl with a history of atopic dermatitis presented with a facial rash of 4 months’ duration. Her pediatrician initially treated the rash as pityriasis alba and prescribed hydrocortisone cream. Two months into treatment, the patient developed an otherwise asymptomatic, unilateral, papular dermatosis on the right cheek. She subsequently was switched to treatment with benzoyl peroxide and topical clindamycin, which she had been using for 2 months with no improvement at the time of the current presentation. The lesions then spread bilaterally and periorally.

At the current presentation, physical examination demonstrated fine, diffuse, follicular-based, flesh-colored papules over both cheeks, the right side of the nose, and the perioral region (Figure 1). A biopsy of a papular lesion from the right cheek revealed well-formed, noncaseating granulomas in the superficial and mid dermis with an associated lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). No organisms were identified on acid-fast, Fite, or periodic acid–Schiff staining. A tuberculin skin test was negative. A chest radiograph showed small calcified hilar lymph nodes bilaterally. Pulmonary function tests were unremarkable. Calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal.

The patient denied any fever, chills, hemoptysis, cough, dyspnea, lymphadenopathy, scleral or conjunctival pain or erythema, visual disturbances, or arthralgias. Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was started with minimal improvement after 5 months. Methotrexate 20 mg once weekly was then added. Topical fluocinonide 0.05% also was started at this time, as the patient had required several prednisone tapers over the past 3 months for symptomatic relief. The lesions improved minimally after 5 more months of treatment, at which time she had developed inflammatory papules, pustules, and open comedones in the same areas as well as the glabella.

Repeat biopsy of a papular lesion demonstrated noncaseating granulomas and an associated chronic lymphocytic infiltrate in a follicular and perifollicular distribution (Figure 3). Biopsy of a pustule demonstrated acute Demodex folliculitis. Fluocinonide was stopped, and anti-mite therapy with ivermectin, permethrin cream 5%, and selenium sulfide lotion 2.5% was started, with good response from the pustular lesions.

The patient continued taking methotrexate 20 mg once weekly during this time, with improvement in the papular lesions. She discontinued methotrexate after 12 months with complete resolution. At follow-up 12 months after stopping the methotrexate (roughly 2 years after initial presentation), she showed sustained resolution, with small pitted scars on both cheeks and the nasal tip.

Patient 2—A 33-year-old Ethiopian woman presented with a facial rash of 15 years’ duration. The lesions had been accumulating slowly and were asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed multiple follicular-based, flesh-colored, and erythematous papules on the cheeks, chin, perioral area, and forehead (Figure 4). There were no pustules or telangiectasias. Treatment with tretinoin cream 0.05% for 6 months offered minimal relief.

Biopsy of a papule from the left mandible showed superficial vascular telangiectasias, noncaseating granulomas comprising epithelioid histiocytes and lymphocytes in the superficial dermis, and a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 5). No organisms were identified on Fite or Gomori methenamine silver staining.

Comment

The first step in differentiating cutaneous granulomatous lesions should be to distinguish infectious from noninfectious causes.1 Noninfectious cutaneous granulomas can appear nearly anywhere; however, certain processes have a predilection for the face, including GPD, GR, LMDF, and papular sarcoidosis.5-7 These conditions generally present with papular granulomas with features as described above.

Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis—In 1970, Gianotti and colleagues8 briefly described the first possible cases of GPD in 5 children. The eruption comprised numerous yellow, dome-shaped papules in a mostly perioral distribution. Tuberculin and the Kveim tests were nonreactive; histopathology was described as sarcoid-type and not necessarily follicular or perifollicular.8 In 1974, Marten et al9 described 22 Afro-Caribbean children with flesh-colored, papular eruptions on the face that did not show histologic granulomatous changes but were morphologically similar to the reports by Gianotti et al.8 By 1989, Frieden and colleagues10 described this facial eruption as “granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children”. Additionally, the investigators observed granulomatous infiltrates in a perifollicular distribution and suggested follicular disruption as a possible cause. It was clear from the case discussions that these eruptions were not uncommonly diagnosed as papular sarcoidosis.10 The following year, Williams et al11 reported 5 cases of similar papular eruptions in 5 Afro-Caribbean children, coining the term facial Afro-Caribbean eruption.11 Knautz and Lesher12 referred to this entity as “childhood GPD” in 1996 to avoid limiting the diagnosis to Afro-Caribbean patients and to a perioral distribution; this is the most popular current terminology.12 Since then, reports of extrafacial involvement and disease in adults have been published.13,14

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis often is seen in the perinasal, periocular, and perioral regions of the face.2 It is associated with topical steroid exposure.5 Histologically, noncaseating granulomas around the upper half of undisrupted hair follicles with a lymphocytic infiltrate are typical.13 Treatment should begin with cessation of any topical steroids; first-line agents are oral tetracycline or macrolide antibiotics.5 These agents can be used alone or in combination with topical erythromycin, metronidazole, or sulfur-based lotions.13 Rarely, GPD presents extrafacially.13 Even so, it usually resolves within 2 weeks to 6 months, especially with therapy; scarring is unusual.5,13,15

Granulomatous Rosacea—A report in the early 20th century described patients with tuberculoid granulomas resembling papular rosacea; the initial belief was that this finding represented a rosacealike tuberculid eruption.5 However, this belief was questioned by Snapp,16 among others, who demonstrated near universal lack of reactivity to tuberculin among 20 of these patients in 1949; more recent evidence has substantiated these findings.17 Still, Snapp16 postulated that these rosacealike granulomatous lesions were distinct from classic rosacea because they lacked vascular symptoms and pustules and were recalcitrant to rosacea treatment modalities.

In 1970, Mullanax and colleagues18 introduced the term granulomatous rosacea, reiterating that this entity was not tuberculous. They documented papulopustular lesions as well as telangiectasias, raising the possibility that GR does overlap with acne rosacea. More recent studies have established the current theory that GR is a histologic variant of acne rosacea because, in addition to typical granulomatous papules, its microscopic features can be seen across subtypes of acne rosacea.19,20

Various causes have been proposed for GR. Demodex mites have been reported in association with GR for nearly 30 years.19,20 In the past 10 years, molecular studies have started to define the role of metalloproteinases, UV radiation, and cutaneous peptides in the pathogenesis of acne rosacea and GR.21,22

Granulomatous rosacea typically is seen in middle-aged women.20,23 Hallmarks of rosacea, such as facial erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, pustules, and rhinophyma, are not always present in GR.5,20,23 Lesions usually are distributed around the central face, although extension to the cheeks, total facial involvement, and extrafacial lesions are possible.5,20 Histologically, perifollicular and follicular-based noncaseating granulomas with dilatation of the dermal papillary vasculature are seen.17,23 As a whole, rosacea is comparatively uncommon in dark-skinned patients; when it does occur, GR is a frequent presentation.24

First-line treatment for GR is tetracycline antibiotics.5 Unresponsive cases have been treated—largely anecdotally—with topical modalities (eg, metronidazole, steroids, immunomodulators), systemic agents (eg, dapsone, erythromycin, isotretinoin), and other therapies.5 Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a chronic course.5,23

Lupus Miliaris Disseminatus Faciei—Classic LMDF demonstrates caseating perifollicular granulomas histologically.6,17,25 Lesions tend to appear on the central face, particularly the eyelids, and can be seen extrafacially.3,6,25,26 Although LMDF originally was categorized as a tuberculid eruption, this no longer is thought to be the case.27 It is now regarded by some as a variant of GR25; however, LMDF responds poorly to tetracyclines, is more common in males, and lacks rosacealike vascular abnormalities, leading some to question this association.3,6,17 In the past 20 years, some have proposed renaming LMDF to better reflect its clinical course and to consider it independent of tuberculosis and GR.28 It usually resolves spontaneously after 1 to 3 years, leaving pitted scars.3,6

Papular Sarcoidosis—The first potential documented case of sarcoidosis was by Hutchinson29 in 1869 in a patient seen in London. The author labeled purple plaques on the index patient’s legs and hands as “livid papillary psoriasis.” In 1889, Besnier30 described a patient with violaceous swellings on the nose, ears, and fingers, which he called “lupus pernio”; his contemporary, Tenneson,31 published a case of lupus pernio and described its histologic profile as comprising epithelioid cells and giant cells. It was not until 1899 that the term sarkoid was used to describe these cutaneous lesions by Boeck,32 who thought they were reminiscent of sarcoma. In 1915, Kuznitsky and Bittorf33 described a patient with cutaneous lesions histologically consistent with Boeck’s sarkoid but additionally with hilar lymphadenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates. Around 1916 or 1917, Schaumann34 described patients with cutaneous lesions and additionally with involvement of pulmonary, osseous, hepatosplenic, and tonsillar tissue. These reports are among the first to recognize the multisystemic nature of sarcoidosis. The first possible case of childhood sarcoidosis might have been reported by Osler35 in the United States in 1898.

In the past century or so, an ongoing effort by researchers has focused on identifying etiologic triggers for sarcoidosis. Microbial agents have been considered in this role, with Mycobacterium and Propionibacterium organisms the most intensively studied; the possibility that foreign material contributes to the formation of granulomas also has been raised.36 Current models of the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis involve an interplay between the immune system in genetically predisposed patients and an infection that leads to a hyperimmune type 1 T–helper cell response that clears the infection but not antigens generated by the microbes and the acute host response, including proteins such as serum amyloid A and vimentin.36,37 These antigens aggregate and serve as a nidus for granuloma formation and maintenance long after infection has resolved.

Cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis include macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio, as well as lesions arising within scars or tattoos, with many less common presentations.7,38 Papular sarcoidosis is common on the face but also can involve the extremities.4,7 Strictly, at least 2 organ systems must be involved to diagnose sarcoidosis, but this is debatable.4,7 Among 41 patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, 24 (58.5%) had systemic disease; cutaneous lesions were the presenting sign in 87.5% (21/24) of patients.38 Histologic analysis, regardless of the lesion, usually shows noncaseating so-called “naked” granulomas, which have minimal lymphocytic infiltrate associated with the epithelioid histiocytes.38,39 Perifollicular granulomas are possible but unusual.40

Treatment depends on the extent of cutaneous and systemic involvement. Pharmacotherapeutic modalities include topical steroids, immunomodulators, and retinoids; systemic immunomodulators and immunosuppressants; and biologic agents.7 Isolated cutaneous sarcoidosis, particularly the papular variant, usually is associated with acute disease lasting less than 2 years, with resolution of skin lesions.7,38 That said, a recent report suggested that cutaneous sarcoidosis can progress to multisystemic disease as long as 7 years after the initial diagnosis.41

Clinical and Histologic Overlap—Despite this categorization of noninfectious facial granulomatous conditions, each has some clinical and histologic overlap with the others, which must be considered when encountering a granulomatous facial dermatosis. Both GPD and GR tend to present with lesions near the eyes, mouth, and nose, although GR can extend to lateral aspects of the face, below the mandible, and the forehead and has different demographic features.15,20,23 Granulomas in both GPD and GR generally are noncaseating and form in a follicular or perifollicular distribution within the dermis.2,15,23 Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei and GR share a similar facial distribution in some cases.17,20 Even papular cutaneous sarcoidosis has masqueraded as GR clinically and histologically.4

Diagnostic and Treatment Difficulty—Our cases illustrate the range of difficulty in evaluating and managing patients with facial papular granulomas. On one hand, our adult patient’s clinical and histologic findings were highly consistent with GR; on the other hand, our younger patient had clinicopathologic features of both sarcoidosis and GPD at varying times. Both conditions are more common in dark-skinned patients.11,42

Juvenile sarcoidosis is comparatively rare, with a reported annual incidence of 0.22 to 0.27 for every 100,000 children younger than 15 years; however, juvenile sarcoidosis commonly presents around 8 to 15 years of age.43

It is unusual for sarcoid granulomas to be isolated to the skin, much less to the face.4,7,43,44 Patient 1 initially presented in this manner and lacked convincing laboratory or radiographic evidence of systemic sarcoidosis. Bilateral hilar calcifications in sarcoidosis are more typical among adults after 5 to 20 years; there were no signs or symptoms of active infection that could account for the pulmonary and cutaneous lesions.45

The presence of perifollicular granulomas with associated lymphocytic infiltrates on repeat biopsy, coupled with the use of topical steroids, made it difficult to rule out a contribution by GPD to her clinical course. That her lesions resolved with pitted scarring while she was taking methotrexate and after topical steroids had been stopped could be the result of successful management or spontaneous resolution of her dermatosis; both papular sarcoidosis and GPD tend to have a self-limited course.7,13

Conclusion

We present 2 cases of papular facial granulomas in patients with similar skin types who had different clinical courses. Evaluation of such lesions remains challenging given the similarity between specific entities that present in this manner. Certainly, it is reasonable to consider a spectrum upon which all of these conditions fall, in light of the findings of these cases and those reported previously.

Cutaneous granulomatous diseases encompass many entities that are skin-limited or systemic. The prototypical cutaneous granuloma is a painless, rounded, well-defined, red-pink or flesh-colored papule1 and is smooth, owing to minimal epidermal involvement. Examples of conditions that present with such lesions include granulomatous periorificial dermatitis (GPD), granulomatous rosacea (GR), lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei (LMDF), and papular sarcoidosis. These entities commonly are seen on the face and can be a source of distress to patients when they are extensive. Several reports have raised the possibility that these conditions lie on a spectrum.2-4 We present 2 cases of patients with facial papular granulomas, discuss potential causes of the lesions, review historical aspects from the literature, and highlight the challenges that these lesions can pose to the clinician.

Case Reports

Patient 1—A 10-year-old Ethiopian girl with a history of atopic dermatitis presented with a facial rash of 4 months’ duration. Her pediatrician initially treated the rash as pityriasis alba and prescribed hydrocortisone cream. Two months into treatment, the patient developed an otherwise asymptomatic, unilateral, papular dermatosis on the right cheek. She subsequently was switched to treatment with benzoyl peroxide and topical clindamycin, which she had been using for 2 months with no improvement at the time of the current presentation. The lesions then spread bilaterally and periorally.

At the current presentation, physical examination demonstrated fine, diffuse, follicular-based, flesh-colored papules over both cheeks, the right side of the nose, and the perioral region (Figure 1). A biopsy of a papular lesion from the right cheek revealed well-formed, noncaseating granulomas in the superficial and mid dermis with an associated lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 2). No organisms were identified on acid-fast, Fite, or periodic acid–Schiff staining. A tuberculin skin test was negative. A chest radiograph showed small calcified hilar lymph nodes bilaterally. Pulmonary function tests were unremarkable. Calcium and angiotensin-converting enzyme levels were normal.

The patient denied any fever, chills, hemoptysis, cough, dyspnea, lymphadenopathy, scleral or conjunctival pain or erythema, visual disturbances, or arthralgias. Hydroxychloroquine 200 mg twice daily was started with minimal improvement after 5 months. Methotrexate 20 mg once weekly was then added. Topical fluocinonide 0.05% also was started at this time, as the patient had required several prednisone tapers over the past 3 months for symptomatic relief. The lesions improved minimally after 5 more months of treatment, at which time she had developed inflammatory papules, pustules, and open comedones in the same areas as well as the glabella.

Repeat biopsy of a papular lesion demonstrated noncaseating granulomas and an associated chronic lymphocytic infiltrate in a follicular and perifollicular distribution (Figure 3). Biopsy of a pustule demonstrated acute Demodex folliculitis. Fluocinonide was stopped, and anti-mite therapy with ivermectin, permethrin cream 5%, and selenium sulfide lotion 2.5% was started, with good response from the pustular lesions.

The patient continued taking methotrexate 20 mg once weekly during this time, with improvement in the papular lesions. She discontinued methotrexate after 12 months with complete resolution. At follow-up 12 months after stopping the methotrexate (roughly 2 years after initial presentation), she showed sustained resolution, with small pitted scars on both cheeks and the nasal tip.

Patient 2—A 33-year-old Ethiopian woman presented with a facial rash of 15 years’ duration. The lesions had been accumulating slowly and were asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed multiple follicular-based, flesh-colored, and erythematous papules on the cheeks, chin, perioral area, and forehead (Figure 4). There were no pustules or telangiectasias. Treatment with tretinoin cream 0.05% for 6 months offered minimal relief.

Biopsy of a papule from the left mandible showed superficial vascular telangiectasias, noncaseating granulomas comprising epithelioid histiocytes and lymphocytes in the superficial dermis, and a perifollicular lymphocytic infiltrate (Figure 5). No organisms were identified on Fite or Gomori methenamine silver staining.

Comment

The first step in differentiating cutaneous granulomatous lesions should be to distinguish infectious from noninfectious causes.1 Noninfectious cutaneous granulomas can appear nearly anywhere; however, certain processes have a predilection for the face, including GPD, GR, LMDF, and papular sarcoidosis.5-7 These conditions generally present with papular granulomas with features as described above.

Granulomatous Periorificial Dermatitis—In 1970, Gianotti and colleagues8 briefly described the first possible cases of GPD in 5 children. The eruption comprised numerous yellow, dome-shaped papules in a mostly perioral distribution. Tuberculin and the Kveim tests were nonreactive; histopathology was described as sarcoid-type and not necessarily follicular or perifollicular.8 In 1974, Marten et al9 described 22 Afro-Caribbean children with flesh-colored, papular eruptions on the face that did not show histologic granulomatous changes but were morphologically similar to the reports by Gianotti et al.8 By 1989, Frieden and colleagues10 described this facial eruption as “granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children”. Additionally, the investigators observed granulomatous infiltrates in a perifollicular distribution and suggested follicular disruption as a possible cause. It was clear from the case discussions that these eruptions were not uncommonly diagnosed as papular sarcoidosis.10 The following year, Williams et al11 reported 5 cases of similar papular eruptions in 5 Afro-Caribbean children, coining the term facial Afro-Caribbean eruption.11 Knautz and Lesher12 referred to this entity as “childhood GPD” in 1996 to avoid limiting the diagnosis to Afro-Caribbean patients and to a perioral distribution; this is the most popular current terminology.12 Since then, reports of extrafacial involvement and disease in adults have been published.13,14

Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis often is seen in the perinasal, periocular, and perioral regions of the face.2 It is associated with topical steroid exposure.5 Histologically, noncaseating granulomas around the upper half of undisrupted hair follicles with a lymphocytic infiltrate are typical.13 Treatment should begin with cessation of any topical steroids; first-line agents are oral tetracycline or macrolide antibiotics.5 These agents can be used alone or in combination with topical erythromycin, metronidazole, or sulfur-based lotions.13 Rarely, GPD presents extrafacially.13 Even so, it usually resolves within 2 weeks to 6 months, especially with therapy; scarring is unusual.5,13,15

Granulomatous Rosacea—A report in the early 20th century described patients with tuberculoid granulomas resembling papular rosacea; the initial belief was that this finding represented a rosacealike tuberculid eruption.5 However, this belief was questioned by Snapp,16 among others, who demonstrated near universal lack of reactivity to tuberculin among 20 of these patients in 1949; more recent evidence has substantiated these findings.17 Still, Snapp16 postulated that these rosacealike granulomatous lesions were distinct from classic rosacea because they lacked vascular symptoms and pustules and were recalcitrant to rosacea treatment modalities.

In 1970, Mullanax and colleagues18 introduced the term granulomatous rosacea, reiterating that this entity was not tuberculous. They documented papulopustular lesions as well as telangiectasias, raising the possibility that GR does overlap with acne rosacea. More recent studies have established the current theory that GR is a histologic variant of acne rosacea because, in addition to typical granulomatous papules, its microscopic features can be seen across subtypes of acne rosacea.19,20

Various causes have been proposed for GR. Demodex mites have been reported in association with GR for nearly 30 years.19,20 In the past 10 years, molecular studies have started to define the role of metalloproteinases, UV radiation, and cutaneous peptides in the pathogenesis of acne rosacea and GR.21,22

Granulomatous rosacea typically is seen in middle-aged women.20,23 Hallmarks of rosacea, such as facial erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, pustules, and rhinophyma, are not always present in GR.5,20,23 Lesions usually are distributed around the central face, although extension to the cheeks, total facial involvement, and extrafacial lesions are possible.5,20 Histologically, perifollicular and follicular-based noncaseating granulomas with dilatation of the dermal papillary vasculature are seen.17,23 As a whole, rosacea is comparatively uncommon in dark-skinned patients; when it does occur, GR is a frequent presentation.24

First-line treatment for GR is tetracycline antibiotics.5 Unresponsive cases have been treated—largely anecdotally—with topical modalities (eg, metronidazole, steroids, immunomodulators), systemic agents (eg, dapsone, erythromycin, isotretinoin), and other therapies.5 Granulomatous rosacea tends to have a chronic course.5,23

Lupus Miliaris Disseminatus Faciei—Classic LMDF demonstrates caseating perifollicular granulomas histologically.6,17,25 Lesions tend to appear on the central face, particularly the eyelids, and can be seen extrafacially.3,6,25,26 Although LMDF originally was categorized as a tuberculid eruption, this no longer is thought to be the case.27 It is now regarded by some as a variant of GR25; however, LMDF responds poorly to tetracyclines, is more common in males, and lacks rosacealike vascular abnormalities, leading some to question this association.3,6,17 In the past 20 years, some have proposed renaming LMDF to better reflect its clinical course and to consider it independent of tuberculosis and GR.28 It usually resolves spontaneously after 1 to 3 years, leaving pitted scars.3,6

Papular Sarcoidosis—The first potential documented case of sarcoidosis was by Hutchinson29 in 1869 in a patient seen in London. The author labeled purple plaques on the index patient’s legs and hands as “livid papillary psoriasis.” In 1889, Besnier30 described a patient with violaceous swellings on the nose, ears, and fingers, which he called “lupus pernio”; his contemporary, Tenneson,31 published a case of lupus pernio and described its histologic profile as comprising epithelioid cells and giant cells. It was not until 1899 that the term sarkoid was used to describe these cutaneous lesions by Boeck,32 who thought they were reminiscent of sarcoma. In 1915, Kuznitsky and Bittorf33 described a patient with cutaneous lesions histologically consistent with Boeck’s sarkoid but additionally with hilar lymphadenopathy and pulmonary infiltrates. Around 1916 or 1917, Schaumann34 described patients with cutaneous lesions and additionally with involvement of pulmonary, osseous, hepatosplenic, and tonsillar tissue. These reports are among the first to recognize the multisystemic nature of sarcoidosis. The first possible case of childhood sarcoidosis might have been reported by Osler35 in the United States in 1898.

In the past century or so, an ongoing effort by researchers has focused on identifying etiologic triggers for sarcoidosis. Microbial agents have been considered in this role, with Mycobacterium and Propionibacterium organisms the most intensively studied; the possibility that foreign material contributes to the formation of granulomas also has been raised.36 Current models of the pathogenesis of sarcoidosis involve an interplay between the immune system in genetically predisposed patients and an infection that leads to a hyperimmune type 1 T–helper cell response that clears the infection but not antigens generated by the microbes and the acute host response, including proteins such as serum amyloid A and vimentin.36,37 These antigens aggregate and serve as a nidus for granuloma formation and maintenance long after infection has resolved.

Cutaneous lesions of sarcoidosis include macules, papules, plaques, and lupus pernio, as well as lesions arising within scars or tattoos, with many less common presentations.7,38 Papular sarcoidosis is common on the face but also can involve the extremities.4,7 Strictly, at least 2 organ systems must be involved to diagnose sarcoidosis, but this is debatable.4,7 Among 41 patients with cutaneous sarcoidosis, 24 (58.5%) had systemic disease; cutaneous lesions were the presenting sign in 87.5% (21/24) of patients.38 Histologic analysis, regardless of the lesion, usually shows noncaseating so-called “naked” granulomas, which have minimal lymphocytic infiltrate associated with the epithelioid histiocytes.38,39 Perifollicular granulomas are possible but unusual.40

Treatment depends on the extent of cutaneous and systemic involvement. Pharmacotherapeutic modalities include topical steroids, immunomodulators, and retinoids; systemic immunomodulators and immunosuppressants; and biologic agents.7 Isolated cutaneous sarcoidosis, particularly the papular variant, usually is associated with acute disease lasting less than 2 years, with resolution of skin lesions.7,38 That said, a recent report suggested that cutaneous sarcoidosis can progress to multisystemic disease as long as 7 years after the initial diagnosis.41

Clinical and Histologic Overlap—Despite this categorization of noninfectious facial granulomatous conditions, each has some clinical and histologic overlap with the others, which must be considered when encountering a granulomatous facial dermatosis. Both GPD and GR tend to present with lesions near the eyes, mouth, and nose, although GR can extend to lateral aspects of the face, below the mandible, and the forehead and has different demographic features.15,20,23 Granulomas in both GPD and GR generally are noncaseating and form in a follicular or perifollicular distribution within the dermis.2,15,23 Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei and GR share a similar facial distribution in some cases.17,20 Even papular cutaneous sarcoidosis has masqueraded as GR clinically and histologically.4

Diagnostic and Treatment Difficulty—Our cases illustrate the range of difficulty in evaluating and managing patients with facial papular granulomas. On one hand, our adult patient’s clinical and histologic findings were highly consistent with GR; on the other hand, our younger patient had clinicopathologic features of both sarcoidosis and GPD at varying times. Both conditions are more common in dark-skinned patients.11,42

Juvenile sarcoidosis is comparatively rare, with a reported annual incidence of 0.22 to 0.27 for every 100,000 children younger than 15 years; however, juvenile sarcoidosis commonly presents around 8 to 15 years of age.43

It is unusual for sarcoid granulomas to be isolated to the skin, much less to the face.4,7,43,44 Patient 1 initially presented in this manner and lacked convincing laboratory or radiographic evidence of systemic sarcoidosis. Bilateral hilar calcifications in sarcoidosis are more typical among adults after 5 to 20 years; there were no signs or symptoms of active infection that could account for the pulmonary and cutaneous lesions.45

The presence of perifollicular granulomas with associated lymphocytic infiltrates on repeat biopsy, coupled with the use of topical steroids, made it difficult to rule out a contribution by GPD to her clinical course. That her lesions resolved with pitted scarring while she was taking methotrexate and after topical steroids had been stopped could be the result of successful management or spontaneous resolution of her dermatosis; both papular sarcoidosis and GPD tend to have a self-limited course.7,13

Conclusion

We present 2 cases of papular facial granulomas in patients with similar skin types who had different clinical courses. Evaluation of such lesions remains challenging given the similarity between specific entities that present in this manner. Certainly, it is reasonable to consider a spectrum upon which all of these conditions fall, in light of the findings of these cases and those reported previously.

- Beretta-Piccoli BT, Mainetti C, Peeters M-A, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8666-8

- Lucas CR, Korman NJ, Gilliam AC. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis: a variant of granulomatous rosacea in children? J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:115-118. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07088

- van de Scheur MR, van der Waal RIF, Starink TM. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei: a distinctive rosacea-like syndrome and not a granulomatous form of rosacea. Dermatology. 2003;206:120-123. doi:10.1159/000068457

- Simonart T, Lowy M, Rasquin F, et al. Overlap of sarcoidosis and rosacea. Dermatology. 1997;194:416-418. doi:10.1159/000246165

- Lee GL, Zirwas MJ. Granulomatous rosacea and periorificial dermatitis: controversies and review of management. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:447-455. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.009

- Michaels JD, Cook-Norris RH, Lehman JS, et al. Adult with papular eruption of the central aspect of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:410-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.039

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;38:685-702. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.010

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Benelli MG, et al. Particulière dermatite peri-orale infantile. observations sur 5 cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1970;77:341.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual papular and acneiform facial eruption in the negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb13083.x

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Williams HC, Ashworth J, Pembroke AC, et al. FACE—facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:163-166. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1990.tb02063.x

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL Jr. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1996.tb01419.x

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.10.1354

- Vincenzi C, Parente G, Tosti A. Perioral granulomatous dermatitis: two cases treated with clarithromycin. J Dermatol Treat. 2000;11:57-61.

- Kim YJ, Shin JW, Lee JS, et al. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:386-388. doi:10.5021/ad.2011.23.3.386

- Snapp RH. Lewandowsky’s rosacea-like eruption; a clinical study. J Invest Dermatol. 1949;13:175-190. doi:10.1038/jid.1949.86

- Chougule A, Chatterjee D, Sethi S, et al. Granulomatous rosacea versus lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei—2 faces of facial granulomatous disorder: a clinicohistological and molecular study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:819-823. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001243

- Mullanax MG, Kierland RR. Granulomatous rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:206-211.

- Sánchez JL, Berlingeri-Ramos AC, Dueño DV. Granulomatous rosacea. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:6-9. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815bc191

- Helm KF, Menz J, Gibson LE, et al. A clinical and histopathologic study of granulomatous rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1038-1043. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70304-k

- Kanada KN, Nakatsuji T, Gallo RL. Doxycycline indirectly inhibits proteolytic activation of tryptic kallikrein-related peptidases and activation of cathelicidin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1435-1442. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.14

- Jang YH, Sim JH, Kang HY, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of matrix metalloproteinases in the granulomatous rosacea compared with the non-granulomatous rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:544-548. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03825.x

- Khokhar O, Khachemoune A. A case of granulomatous rosacea: sorting granulomatous rosacea from other granulomatous diseases that affect the face. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:6.

- Rosen T, Stone MS. Acne rosacea in blacks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:70-73. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70173-x

- Adams AK, Davis JL, Davis MDP, et al. What is your diagnosis? granulomatous rosacea (lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, acne agminata). Cutis. 2008;82:103-112.

- Shitara A. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:542-544. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb04206.x

- Hodak E, Trattner A, Feuerman H, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei—the DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is not detectable in active lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:614-619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03797.x

- Skowron F, Causeret AS, Pabion C, et al. F.I.GU.R.E.: facial idiopathic granulomas with regressive evolution. Dermatology. 2000;201:287-289. doi:10.1159/000051539

- Hutchinson J. Case of livid papillary psoriasis. In: London J, Churchill A, eds. Illustrations of Clinical Surgery. J&A Churchill; 1877:42-43.

- Besnier E. Lupus pernio of the face [in French]. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris). 1889;10:33-36.

- Tenneson H. Lupus pernio. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris). 1889;10:333-336.

- Boeck C. Multiple benign sarkoid of the skin [in Norwegian]. Norsk Mag Laegevidensk. 1899;14:1321-1334.

- Kuznitsky E, Bittorf A. Sarkoid mit beteiligung innerer organe. Münch Med Wochenschr. 1915;62:1349-1353.

- Schaumann J. Etude sur le lupus pernio et ses rapports avec les sarcoides et la tuberculose. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr. 1916-1917;6:357-373.

- Osler W. On chronic symmetrical enlargement of the salivary and lacrimal glands. Am J Med Sci. 1898;115:27-30.

- Chen ES, Moller DR. Etiologies of sarcoidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:6-18. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8481-z

- Eberhardt C, Thillai M, Parker R, et al. Proteomic analysis of Kveim reagent identifies targets of cellular immunity in sarcoidosis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170285. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170285

- Esteves TC, Aparicio G, Ferrer B, et al. Prognostic value of skin lesions in sarcoidosis: clinical and histopathological clues. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:556-562. doi:10.1684/ejd.2015.2666

- Cardoso JC, Cravo M, Reis JP, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: a histopathological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:678-682. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03153.x

- Mangas C, Fernández-Figueras M-T, Fité E, et al. Clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 32 cases of specific cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:772-777. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00563.x

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis. clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14218

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16. doi:10.1186/1546-0096-6-16

- Milman N, Hoffmann AL, Byg KE. Sarcoidosis in children. epidemiology in Danes, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:871-878. doi:10.1080/08035259875001366244. A, H, Yapıcı I. Isolated cutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:220.

- Scadding JG. The late stages of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Postgrad Med J. 1970;46:530-536. doi:10.1136/pgmj.46.538.530

- Beretta-Piccoli BT, Mainetti C, Peeters M-A, et al. Cutaneous granulomatosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2018;54:131-146. doi:10.1007/s12016-017-8666-8

- Lucas CR, Korman NJ, Gilliam AC. Granulomatous periorificial dermatitis: a variant of granulomatous rosacea in children? J Cutan Med Surg. 2009;13:115-118. doi:10.2310/7750.2008.07088

- van de Scheur MR, van der Waal RIF, Starink TM. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei: a distinctive rosacea-like syndrome and not a granulomatous form of rosacea. Dermatology. 2003;206:120-123. doi:10.1159/000068457

- Simonart T, Lowy M, Rasquin F, et al. Overlap of sarcoidosis and rosacea. Dermatology. 1997;194:416-418. doi:10.1159/000246165

- Lee GL, Zirwas MJ. Granulomatous rosacea and periorificial dermatitis: controversies and review of management. Dermatol Clin. 2015;33:447-455. doi:10.1016/j.det.2015.03.009

- Michaels JD, Cook-Norris RH, Lehman JS, et al. Adult with papular eruption of the central aspect of the face. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:410-412. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2012.06.039

- Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;38:685-702. doi:10.1016/j.ccm.2015.08.010

- Gianotti F, Ermacora E, Benelli MG, et al. Particulière dermatite peri-orale infantile. observations sur 5 cas. Bull Soc Fr Dermatol Syphiligr. 1970;77:341.

- Marten RH, Presbury DG, Adamson JE, et al. An unusual papular and acneiform facial eruption in the negro child. Br J Dermatol. 1974;91:435-438. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb13083.x

- Frieden IJ, Prose NS, Fletcher V, et al. Granulomatous perioral dermatitis in children. Arch Dermatol. 1989;125:369-373.

- Williams HC, Ashworth J, Pembroke AC, et al. FACE—facial Afro-Caribbean childhood eruption. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1990;15:163-166. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1990.tb02063.x

- Knautz MA, Lesher JL Jr. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 1996;13:131-134. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1470.1996.tb01419.x

- Urbatsch AJ, Frieden I, Williams ML, et al. Extrafacial and generalized granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Arch Dermatol. 2002;138:1354-1358. doi:10.1001/archderm.138.10.1354

- Vincenzi C, Parente G, Tosti A. Perioral granulomatous dermatitis: two cases treated with clarithromycin. J Dermatol Treat. 2000;11:57-61.

- Kim YJ, Shin JW, Lee JS, et al. Childhood granulomatous periorificial dermatitis. Ann Dermatol. 2011;23:386-388. doi:10.5021/ad.2011.23.3.386

- Snapp RH. Lewandowsky’s rosacea-like eruption; a clinical study. J Invest Dermatol. 1949;13:175-190. doi:10.1038/jid.1949.86

- Chougule A, Chatterjee D, Sethi S, et al. Granulomatous rosacea versus lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei—2 faces of facial granulomatous disorder: a clinicohistological and molecular study. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:819-823. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000001243

- Mullanax MG, Kierland RR. Granulomatous rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 1970;101:206-211.

- Sánchez JL, Berlingeri-Ramos AC, Dueño DV. Granulomatous rosacea. Am J Dermatopathol. 2008;30:6-9. doi:10.1097/DAD.0b013e31815bc191

- Helm KF, Menz J, Gibson LE, et al. A clinical and histopathologic study of granulomatous rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1991;25:1038-1043. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(91)70304-k

- Kanada KN, Nakatsuji T, Gallo RL. Doxycycline indirectly inhibits proteolytic activation of tryptic kallikrein-related peptidases and activation of cathelicidin. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1435-1442. doi:10.1038/jid.2012.14

- Jang YH, Sim JH, Kang HY, et al. Immunohistochemical expression of matrix metalloproteinases in the granulomatous rosacea compared with the non-granulomatous rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2011;25:544-548. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2010.03825.x

- Khokhar O, Khachemoune A. A case of granulomatous rosacea: sorting granulomatous rosacea from other granulomatous diseases that affect the face. Dermatol Online J. 2004;10:6.

- Rosen T, Stone MS. Acne rosacea in blacks. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1987;17:70-73. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(87)70173-x

- Adams AK, Davis JL, Davis MDP, et al. What is your diagnosis? granulomatous rosacea (lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, acne agminata). Cutis. 2008;82:103-112.

- Shitara A. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei. Int J Dermatol. 1984;23:542-544. doi:10.1111/j.1365-4362.1984.tb04206.x

- Hodak E, Trattner A, Feuerman H, et al. Lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei—the DNA of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is not detectable in active lesions by polymerase chain reaction. Br J Dermatol. 1997;137:614-619. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1997.tb03797.x

- Skowron F, Causeret AS, Pabion C, et al. F.I.GU.R.E.: facial idiopathic granulomas with regressive evolution. Dermatology. 2000;201:287-289. doi:10.1159/000051539

- Hutchinson J. Case of livid papillary psoriasis. In: London J, Churchill A, eds. Illustrations of Clinical Surgery. J&A Churchill; 1877:42-43.

- Besnier E. Lupus pernio of the face [in French]. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris). 1889;10:33-36.

- Tenneson H. Lupus pernio. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr (Paris). 1889;10:333-336.

- Boeck C. Multiple benign sarkoid of the skin [in Norwegian]. Norsk Mag Laegevidensk. 1899;14:1321-1334.

- Kuznitsky E, Bittorf A. Sarkoid mit beteiligung innerer organe. Münch Med Wochenschr. 1915;62:1349-1353.

- Schaumann J. Etude sur le lupus pernio et ses rapports avec les sarcoides et la tuberculose. Ann Dermatol Syphiligr. 1916-1917;6:357-373.

- Osler W. On chronic symmetrical enlargement of the salivary and lacrimal glands. Am J Med Sci. 1898;115:27-30.

- Chen ES, Moller DR. Etiologies of sarcoidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:6-18. doi:10.1007/s12016-015-8481-z

- Eberhardt C, Thillai M, Parker R, et al. Proteomic analysis of Kveim reagent identifies targets of cellular immunity in sarcoidosis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0170285. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0170285

- Esteves TC, Aparicio G, Ferrer B, et al. Prognostic value of skin lesions in sarcoidosis: clinical and histopathological clues. Eur J Dermatol. 2015;25:556-562. doi:10.1684/ejd.2015.2666

- Cardoso JC, Cravo M, Reis JP, et al. Cutaneous sarcoidosis: a histopathological study. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:678-682. doi:10.1111/j.1468-3083.2009.03153.x

- Mangas C, Fernández-Figueras M-T, Fité E, et al. Clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 32 cases of specific cutaneous sarcoidosis. J Cutan Pathol. 2006;33:772-777. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0560.2006.00563.x

- García-Colmenero L, Sánchez-Schmidt JM, Barranco C, et al. The natural history of cutaneous sarcoidosis. clinical spectrum and histological analysis of 40 cases. Int J Dermatol. 2019;58:178-184. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14218

- Shetty AK, Gedalia A. Childhood sarcoidosis: a rare but fascinating disorder. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2008;6:16. doi:10.1186/1546-0096-6-16

- Milman N, Hoffmann AL, Byg KE. Sarcoidosis in children. epidemiology in Danes, clinical features, diagnosis, treatment and prognosis. Acta Paediatr. 1998;87:871-878. doi:10.1080/08035259875001366244. A, H, Yapıcı I. Isolated cutaneous sarcoidosis. Arch Bronconeumol. 2016;52:220.

- Scadding JG. The late stages of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Postgrad Med J. 1970;46:530-536. doi:10.1136/pgmj.46.538.530

Practice Points

- Dermatologists should be aware that noninfectious granulomatous dermatosis of the face can be caused by granulomatous periorificial dermatitis, granulomatous rosacea, lupus miliaris disseminatus faciei, and papular sarcoidosis.

- These conditions lie on a spectrum, suggested by their historical description and clinical and histological features.

- Because their clinical courses can vary considerably from patient to patient, a thorough effort should be made to differentiate these conditions.