User login

Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers of Rosacea

Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers of Rosacea

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, papules, pustules, and rarely, phymatous changes that primarily manifest in a centrofacial distribution.1,2 Although establishing the true prevalence of rosacea may be challenging due to a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, current studies estimate that it is between 5% to 6% of the global adult population and that rosacea most commonly is diagnosed in patients aged 30 and 60 years, though it occasionally can affect adolescents and children.3,4 Although the origin and pathophysiology of rosacea remain incompletely understood, the condition arises from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, immune, microbial, and neurovascular factors; this interplay ultimately leads to excessive production of inflammatory and vasoactive peptides, chronic inflammation, and neurovascular hyperreactivity.1,5-7

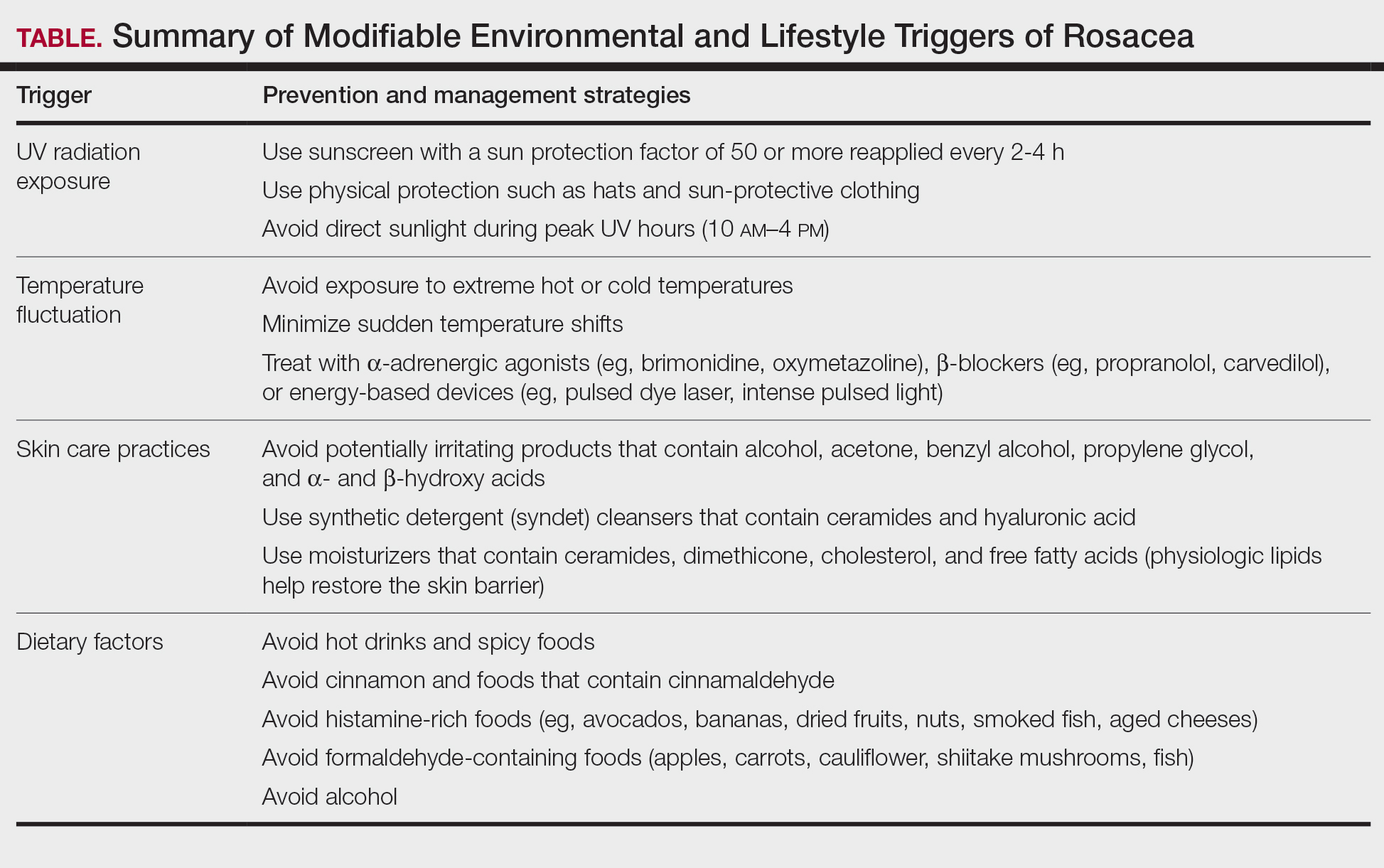

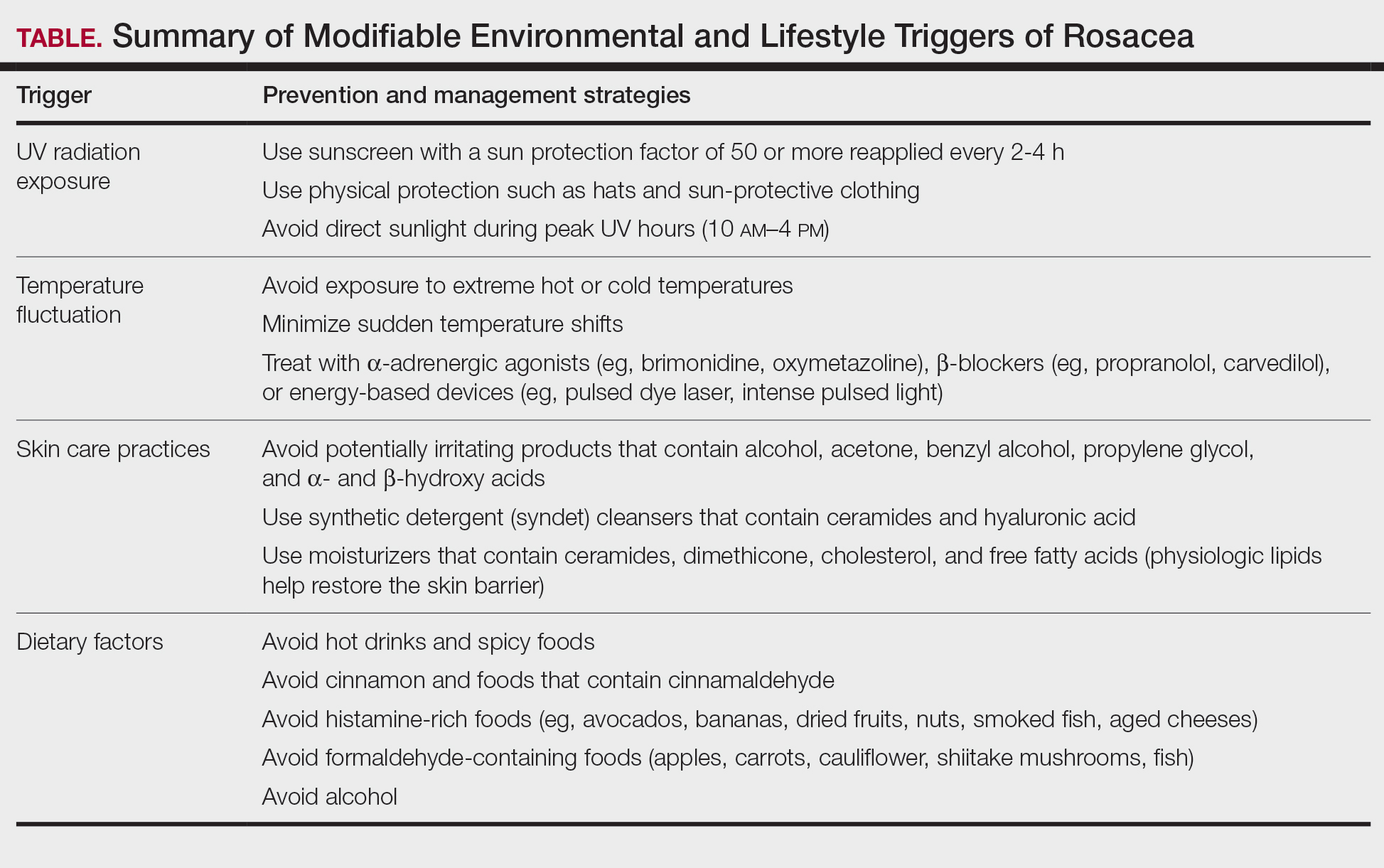

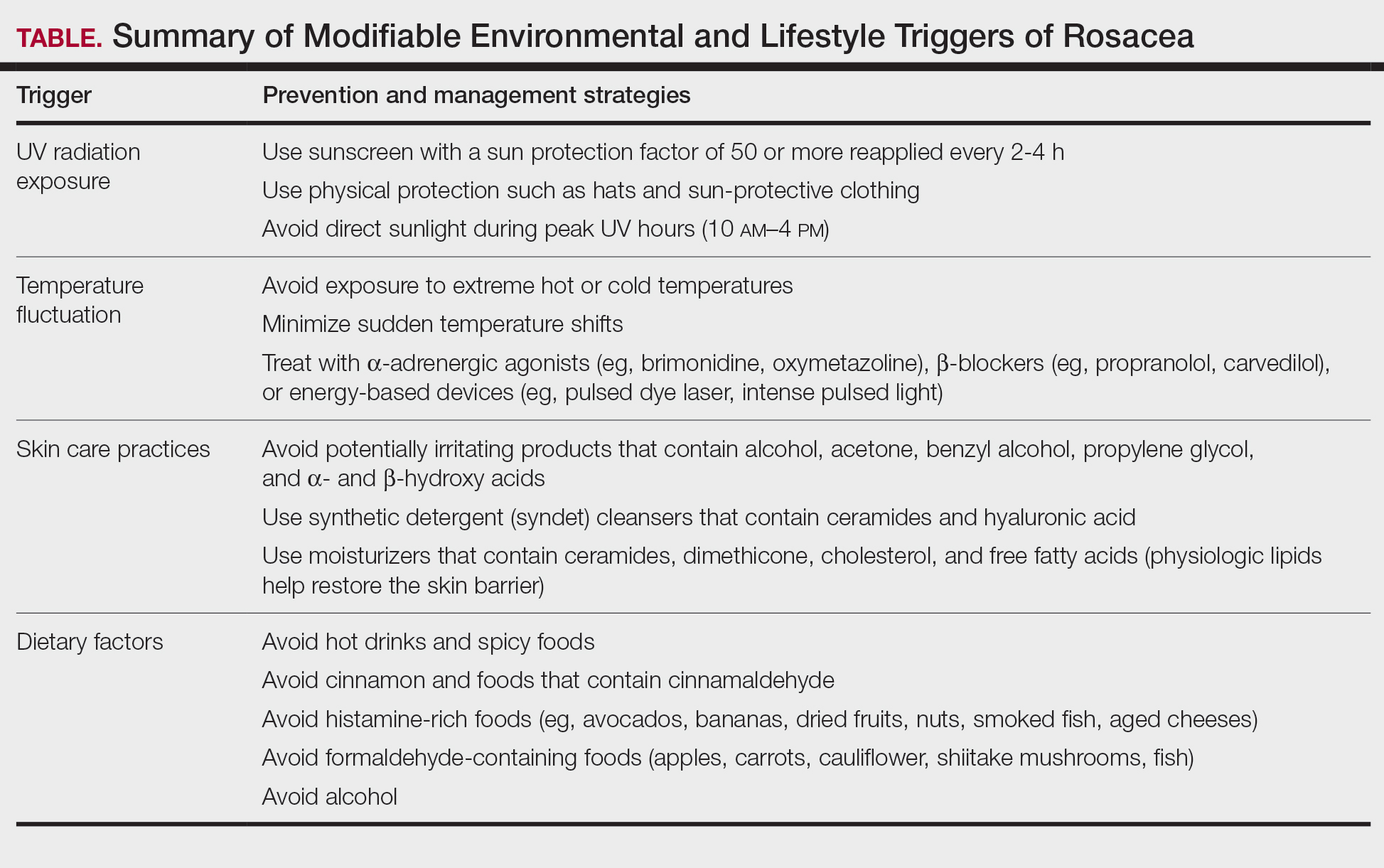

Identifying triggers can be valuable in managing rosacea, as avoidance of these exposures may lead to disease improvement. In this review, we highlight 4 major environmental triggers of rosacea—UV radiation exposure, temperature fluctuation, skin care practices, and diet—and their roles in its pathogenesis and management. A high-level summary of recommendations can be found in the Table.

UV Radiation Exposure

Exposure to UV radiation is a known trigger of rosacea and may worsen symptoms through several mechanisms.8,9 It increases the production of inflammatory cytokines, which enhance the release of vascular endothelial growth factor, promoting angiogenesis and vasodilation.10 Exposure to UV radiation also contributes to tissue inflammation through the production of reactive oxygen species, further mediating inflammatory cascades and leading to immune dysregulation.11,12 Interestingly, though the mechanisms by which UV radiation may contribute to the pathophysiology of rosacea are well described, it remains unclear whether chronic UV exposure plays a major role in the pathogenesis or disease progression of rosacea.1 Studies have observed that increased exposure to sunlight seems to be correlated with increased severity of redness but not of papules and pustules.13,14

Despite some uncertainty regarding the relationship between rosacea and chronic UV exposure, sun protection is a prudent recommendation in this patient population, particularly given other risks of exposure to UV radiation, such as photoaging and skin cancer.9,15,16 Sun protection can be accomplished using broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 50 or higher, reapplied every 2 to 4 hours) or by wearing physical protection (eg, hats, sun-protective clothing) along with avoidance of sun exposure during peak UV hours (ie, 10 am-

Temperature Fluctuation

Both heat and cold exposure have been suggested as triggers for rosacea, thought to be mediated through dysregulations in neurovascular and thermal pathways, resulting in increased flushing and erythema.6 Skin affected by rosacea exhibits a lower threshold for temperature and pain stimuli, resulting in heightened hypersensitivity compared to normal skin.18 Exposure to heat activates thermosensitive receptors found in neuronal and nonneuronal tissues, triggering the release of vasoactive neuropeptides.1 Among these, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels seem to play a crucial role in neurovascular reactivity and have been studied in the pathophysiology of rosacea.1,8 Overexpression or excessive stimulation of TRPs by various environmental triggers, such as heat or cold, leads to increased neuropeptide production, ultimately contributing to persistent erythema and vascular dysfunction, as well as a burning or stinging sensation.1,2 Moreover, rapid temperature changes, such as moving from freezing outdoor conditions into a heated environment, may also trigger flushing due to sudden vasodilation.2

Adopting behavioral strategies such as preventing overheating, minimizing sudden temperature shifts, and protecting the skin from cold can help reduce rosacea flare-ups, particularly flushing. For patients who do not achieve sufficient relief through lifestyle modifications alone, targeted pharmacologic treatments are available to help manage these symptoms. Topical α-adrenergic agonists (eg, brimonidine, oxymetazoline) are effective in reducing erythema and flushing by causing vasoconstriction.15,19 For persistent erythema and telangiectasias, pulsed dye laser and intense pulsed light therapies can be effective treatments, as they target hemoglobin in blood vessels, leading to their destruction and a subsequent reduction in erythema.20 Other medications such as topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, calcitonin-gene related peptide inhibitors, and systemic ß-blockers also can be used to treat flushing and redness.15,21

Skin Care Practices

Due to the increased tissue inflammation and potential skin barrier dysfunction, rosacea-affected skin is highly sensitive, and skin care practices or products that disrupt the already compromised skin barrier can contribute to flare-ups. General recommendations should include use of gentle cleansers and moisturizers to prevent dry skin and improve skin barrier function22 as well as avoidance of ingredients that are common irritants and inducers of allergic contact dermatitis (eg, fragrances).9

Cleansing the face should be limited to 1 to 2 times daily, as excessive cleansing and use of harsh formulations with exfoliative ingredients can lead to skin irritation and worsening of symptoms.9 Overcleansing can lead to alterations in cutaneous pH and strip the stratum corneum of healthy components such as lipids and natural moisturizing factors. Common ingredients in cleansers that should be avoided due to their irritant nature include alcohol, acetone, benzyl alcohol, propylene glycol, and α- and ß-hydroxy acids. Instead, syndet (synthetic detergent) cleansers that contain ceramides, hyaluronic acid, or other hydrating agents with a near-physiological pH can be helpful for dry and sensitive skin.23 Toners with high alcohol content and astringent-based products also should be avoided.

Optimal moisturizers for rosacea-affected skin should contain physiologic lipids that help replace a healthy skin barrier as well as relieve dryness and seal in moisture. Beneficial barrier-restoring ingredients include ceramides, dimethicone, cholesterol, and free fatty acids as well as humectants such as glycerin and hyaluronic acid.9,23,24 Applying moisturizer immediately after cleansing and prior to the application of any topical treatments also can help decrease irritation.

As mentioned previously, sun protection is a cornerstone in the management of rosacea and can help reduce redness and skin irritation. Using combination formulas, such as moisturizers with a sun protection factor of at least 50, can be effective.25 Additionally, products with antioxidant or anti-inflammatory ingredients such as niacinamide and allantoin can further support skin health. Lastly, formulations containing green pigments may also be beneficial, as they provide cosmetic camouflage to neutralize redness.26

Dietary Factors

Several dietary factors have been proposed as triggers for rosacea, but conclusive evidence remains limited.27 Foods and beverages that generate heat (eg, hot drinks, spicy foods) may exacerbate rosacea by causing vasodilation and stimulating TRP channels, resulting in flushing.18 While capsaicin, found in spicy foods, may lead to flushing through similar activation of TRP channels, current evidence has not proved a specific and consistent role in the pathogenesis of rosacea.18,27 Similarly, cinnamaldehyde, found in cinnamon and many commercial cinnamon-containing foods as well as various fruits and vegetables, activates thermosensitive receptors that may worsen rosacea symptoms.28 Other potential triggers include histamine-rich foods (eg, avocados, bananas, dried fruits, nuts, smoked fish, aged cheeses), which can lead to skin hypersensitivity and flushing, and formaldehyde-containing foods (eg, apples, carrots, cauliflower, shiitake mushrooms, fish), though the role these types of foods play in rosacea remains unclear.1,29-31

The relationship between caffeine and rosacea is complex. While caffeine commonly is found in coffee, tea, and soda, some studies have suggested that coffee consumption may reduce rosacea risk due to its vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects.28,32 In contrast, alcohol—particularly white wine and liquor—has been associated with increased rosacea risk due to its effect on vasodilation, inflammation, and oxidative stress.33 Despite anecdotal reports, the role of dairy products in rosacea remains unclear, with conflicting studies suggesting dairy consumption may exacerbate or protect against rosacea.27,28 Given the variability in dietary triggers, patients with rosacea may benefit from using a dietary journal to identify and avoid foods that exacerbate their symptoms, though more research is needed to establish clear recommendations.

Conclusion

Rosacea is a complex condition influenced by genetic, immune, microbial, and environmental factors. Triggers such as UV exposure, temperature fluctuations, alterations in the skin microbiome, and diet contribute to disease exacerbation through mechanisms like vasodilation, neurogenic inflammation, and immune dysregulation. These triggers often interact, compounding their effects and making symptom management more challenging and multifaceted.

Successful rosacea treatment relies on identifying and minimizing patient-specific triggers, as lifestyle modifications can reduce flare-ups and improve outcomes. When combined with interventional, oral, and topical therapies, these adjustments enhance treatment effectiveness and contribute to better long-term disease control. Clinicians should adopt a personalized holistic approach by educating patients on common triggers, recommending lifestyle changes, and integrating medical treatments as necessary. Future research should continue exploring the relationships between rosacea and environmental factors to develop more targeted and evidence-based recommendations.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885.

- Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:282-289. doi:10.1111/bjd.16481

- Chamaillard M, Mortemousque B, Boralevi F, et al. Cutaneous and ocular signs of childhood rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:167-171.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos H, et al. Risk factors associated with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:565-571.

- Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Steinhoff M, et al. Rosacea: the cytokine and chemokine network. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:40-47.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

- Morgado‐Carrasco D, Granger C, Trullas C, et al. Impact of ultraviolet radiation and exposome on rosacea: key role of photoprotection in optimizing treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3415-3421.

- Suhng E, Kim BH, Choi YW, et al. Increased expression of IL‐33 in rosacea skin and UVB‐irradiated and LL‐37‐treated HaCaT cells. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:1023-1029.

- Tisma VS, Basta-Juzbasic A, Jaganjac M, et al. Oxidative stress and ferritin expression in the skin of patients with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:270-276.

- Kulkarni NN, Takahashi T, Sanford JA, et al. Innate immune dysfunction in rosacea promotes photosensitivity and vascular adhesion molecule expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:645-655.E6.

- Bae YI, Yun SJ, Lee JB, et al. Clinical evaluation of 168 Korean patients with rosacea: the sun exposure correlates with the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:243-249.

- McAleer, MA, Fitzpatrick P, Powell FC. Papulopustular rosacea: prevalence and relationship to photodamage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:33-39.

- Van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1754-1764.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:761-770.

- Nichols K, Desai N, Lebwohl MG. Effective sunscreen ingredients and cutaneous irritation in patients with rosacea. Cutis. 1998;61:344-346.

- Guzman-Sanchez DA, Ishiuji Y, Patel T, et al. Enhanced skin blood flow and sensitivity to noxious heat stimuli in papulopustular rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:800-805.

- Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol.2019;181:65-79.

- Wienholtz NKF, Christensen CE, Do TP, et al. Erenumab for treatment of persistent erythema and flushing in rosacea: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol.2024;160:612-619.

- Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 1: a status report on the disease state, general measures, and adjunctive skin care. Cutis. 2013;92:234-240.

- Baldwin H, Alexis AF, Andriessen A, et al. Evidence of barrier deficiency in rosacea and the importance of integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:384-392.

- Schlesinger TE, Powell CR. Efficacy and tolerability of low molecular weight hyaluronic acid sodium salt 0.2% cream in rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:664-667.

- Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902-910.E2.

- Draelos ZD. Cosmeceuticals for rosacea. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:213-217.

- Yuan X, Huang X, Wang B, et al. Relationship between rosacea and dietary factors: a multicenter retrospective case–control survey. J Dermatol. 2019;46:219-225.

- Alia E, Feng H. Rosacea pathogenesis, common triggers, and dietary role: the cause, the trigger, and the positive effects of different foods. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:122-127.

- Branco ACCC, Yoshikawa FSY, Pietrobon AJ, et al. Role of histamine in modulating the immune response and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:1-10.

- Darrigade A, Dendooven E, Aerts O. Contact allergy to fragrances and formaldehyde contributing to papulopustular rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:395-397.

- Linauskiene K, Isaksson M. Allergic contact dermatitis from formaldehyde mimicking impetigo and initiating rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:359-361.

- Al Reef T, Ghanem E. Caffeine: well-known as psychotropic substance, but little as immunomodulator. Immunobiology. 2018;223:818-825.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Rosacea and alcohol intake. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:E25.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, papules, pustules, and rarely, phymatous changes that primarily manifest in a centrofacial distribution.1,2 Although establishing the true prevalence of rosacea may be challenging due to a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, current studies estimate that it is between 5% to 6% of the global adult population and that rosacea most commonly is diagnosed in patients aged 30 and 60 years, though it occasionally can affect adolescents and children.3,4 Although the origin and pathophysiology of rosacea remain incompletely understood, the condition arises from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, immune, microbial, and neurovascular factors; this interplay ultimately leads to excessive production of inflammatory and vasoactive peptides, chronic inflammation, and neurovascular hyperreactivity.1,5-7

Identifying triggers can be valuable in managing rosacea, as avoidance of these exposures may lead to disease improvement. In this review, we highlight 4 major environmental triggers of rosacea—UV radiation exposure, temperature fluctuation, skin care practices, and diet—and their roles in its pathogenesis and management. A high-level summary of recommendations can be found in the Table.

UV Radiation Exposure

Exposure to UV radiation is a known trigger of rosacea and may worsen symptoms through several mechanisms.8,9 It increases the production of inflammatory cytokines, which enhance the release of vascular endothelial growth factor, promoting angiogenesis and vasodilation.10 Exposure to UV radiation also contributes to tissue inflammation through the production of reactive oxygen species, further mediating inflammatory cascades and leading to immune dysregulation.11,12 Interestingly, though the mechanisms by which UV radiation may contribute to the pathophysiology of rosacea are well described, it remains unclear whether chronic UV exposure plays a major role in the pathogenesis or disease progression of rosacea.1 Studies have observed that increased exposure to sunlight seems to be correlated with increased severity of redness but not of papules and pustules.13,14

Despite some uncertainty regarding the relationship between rosacea and chronic UV exposure, sun protection is a prudent recommendation in this patient population, particularly given other risks of exposure to UV radiation, such as photoaging and skin cancer.9,15,16 Sun protection can be accomplished using broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 50 or higher, reapplied every 2 to 4 hours) or by wearing physical protection (eg, hats, sun-protective clothing) along with avoidance of sun exposure during peak UV hours (ie, 10 am-

Temperature Fluctuation

Both heat and cold exposure have been suggested as triggers for rosacea, thought to be mediated through dysregulations in neurovascular and thermal pathways, resulting in increased flushing and erythema.6 Skin affected by rosacea exhibits a lower threshold for temperature and pain stimuli, resulting in heightened hypersensitivity compared to normal skin.18 Exposure to heat activates thermosensitive receptors found in neuronal and nonneuronal tissues, triggering the release of vasoactive neuropeptides.1 Among these, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels seem to play a crucial role in neurovascular reactivity and have been studied in the pathophysiology of rosacea.1,8 Overexpression or excessive stimulation of TRPs by various environmental triggers, such as heat or cold, leads to increased neuropeptide production, ultimately contributing to persistent erythema and vascular dysfunction, as well as a burning or stinging sensation.1,2 Moreover, rapid temperature changes, such as moving from freezing outdoor conditions into a heated environment, may also trigger flushing due to sudden vasodilation.2

Adopting behavioral strategies such as preventing overheating, minimizing sudden temperature shifts, and protecting the skin from cold can help reduce rosacea flare-ups, particularly flushing. For patients who do not achieve sufficient relief through lifestyle modifications alone, targeted pharmacologic treatments are available to help manage these symptoms. Topical α-adrenergic agonists (eg, brimonidine, oxymetazoline) are effective in reducing erythema and flushing by causing vasoconstriction.15,19 For persistent erythema and telangiectasias, pulsed dye laser and intense pulsed light therapies can be effective treatments, as they target hemoglobin in blood vessels, leading to their destruction and a subsequent reduction in erythema.20 Other medications such as topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, calcitonin-gene related peptide inhibitors, and systemic ß-blockers also can be used to treat flushing and redness.15,21

Skin Care Practices

Due to the increased tissue inflammation and potential skin barrier dysfunction, rosacea-affected skin is highly sensitive, and skin care practices or products that disrupt the already compromised skin barrier can contribute to flare-ups. General recommendations should include use of gentle cleansers and moisturizers to prevent dry skin and improve skin barrier function22 as well as avoidance of ingredients that are common irritants and inducers of allergic contact dermatitis (eg, fragrances).9

Cleansing the face should be limited to 1 to 2 times daily, as excessive cleansing and use of harsh formulations with exfoliative ingredients can lead to skin irritation and worsening of symptoms.9 Overcleansing can lead to alterations in cutaneous pH and strip the stratum corneum of healthy components such as lipids and natural moisturizing factors. Common ingredients in cleansers that should be avoided due to their irritant nature include alcohol, acetone, benzyl alcohol, propylene glycol, and α- and ß-hydroxy acids. Instead, syndet (synthetic detergent) cleansers that contain ceramides, hyaluronic acid, or other hydrating agents with a near-physiological pH can be helpful for dry and sensitive skin.23 Toners with high alcohol content and astringent-based products also should be avoided.

Optimal moisturizers for rosacea-affected skin should contain physiologic lipids that help replace a healthy skin barrier as well as relieve dryness and seal in moisture. Beneficial barrier-restoring ingredients include ceramides, dimethicone, cholesterol, and free fatty acids as well as humectants such as glycerin and hyaluronic acid.9,23,24 Applying moisturizer immediately after cleansing and prior to the application of any topical treatments also can help decrease irritation.

As mentioned previously, sun protection is a cornerstone in the management of rosacea and can help reduce redness and skin irritation. Using combination formulas, such as moisturizers with a sun protection factor of at least 50, can be effective.25 Additionally, products with antioxidant or anti-inflammatory ingredients such as niacinamide and allantoin can further support skin health. Lastly, formulations containing green pigments may also be beneficial, as they provide cosmetic camouflage to neutralize redness.26

Dietary Factors

Several dietary factors have been proposed as triggers for rosacea, but conclusive evidence remains limited.27 Foods and beverages that generate heat (eg, hot drinks, spicy foods) may exacerbate rosacea by causing vasodilation and stimulating TRP channels, resulting in flushing.18 While capsaicin, found in spicy foods, may lead to flushing through similar activation of TRP channels, current evidence has not proved a specific and consistent role in the pathogenesis of rosacea.18,27 Similarly, cinnamaldehyde, found in cinnamon and many commercial cinnamon-containing foods as well as various fruits and vegetables, activates thermosensitive receptors that may worsen rosacea symptoms.28 Other potential triggers include histamine-rich foods (eg, avocados, bananas, dried fruits, nuts, smoked fish, aged cheeses), which can lead to skin hypersensitivity and flushing, and formaldehyde-containing foods (eg, apples, carrots, cauliflower, shiitake mushrooms, fish), though the role these types of foods play in rosacea remains unclear.1,29-31

The relationship between caffeine and rosacea is complex. While caffeine commonly is found in coffee, tea, and soda, some studies have suggested that coffee consumption may reduce rosacea risk due to its vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects.28,32 In contrast, alcohol—particularly white wine and liquor—has been associated with increased rosacea risk due to its effect on vasodilation, inflammation, and oxidative stress.33 Despite anecdotal reports, the role of dairy products in rosacea remains unclear, with conflicting studies suggesting dairy consumption may exacerbate or protect against rosacea.27,28 Given the variability in dietary triggers, patients with rosacea may benefit from using a dietary journal to identify and avoid foods that exacerbate their symptoms, though more research is needed to establish clear recommendations.

Conclusion

Rosacea is a complex condition influenced by genetic, immune, microbial, and environmental factors. Triggers such as UV exposure, temperature fluctuations, alterations in the skin microbiome, and diet contribute to disease exacerbation through mechanisms like vasodilation, neurogenic inflammation, and immune dysregulation. These triggers often interact, compounding their effects and making symptom management more challenging and multifaceted.

Successful rosacea treatment relies on identifying and minimizing patient-specific triggers, as lifestyle modifications can reduce flare-ups and improve outcomes. When combined with interventional, oral, and topical therapies, these adjustments enhance treatment effectiveness and contribute to better long-term disease control. Clinicians should adopt a personalized holistic approach by educating patients on common triggers, recommending lifestyle changes, and integrating medical treatments as necessary. Future research should continue exploring the relationships between rosacea and environmental factors to develop more targeted and evidence-based recommendations.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin disease characterized by erythema, flushing, telangiectasias, papules, pustules, and rarely, phymatous changes that primarily manifest in a centrofacial distribution.1,2 Although establishing the true prevalence of rosacea may be challenging due to a wide spectrum of clinical manifestations, current studies estimate that it is between 5% to 6% of the global adult population and that rosacea most commonly is diagnosed in patients aged 30 and 60 years, though it occasionally can affect adolescents and children.3,4 Although the origin and pathophysiology of rosacea remain incompletely understood, the condition arises from a complex interplay of genetic, environmental, immune, microbial, and neurovascular factors; this interplay ultimately leads to excessive production of inflammatory and vasoactive peptides, chronic inflammation, and neurovascular hyperreactivity.1,5-7

Identifying triggers can be valuable in managing rosacea, as avoidance of these exposures may lead to disease improvement. In this review, we highlight 4 major environmental triggers of rosacea—UV radiation exposure, temperature fluctuation, skin care practices, and diet—and their roles in its pathogenesis and management. A high-level summary of recommendations can be found in the Table.

UV Radiation Exposure

Exposure to UV radiation is a known trigger of rosacea and may worsen symptoms through several mechanisms.8,9 It increases the production of inflammatory cytokines, which enhance the release of vascular endothelial growth factor, promoting angiogenesis and vasodilation.10 Exposure to UV radiation also contributes to tissue inflammation through the production of reactive oxygen species, further mediating inflammatory cascades and leading to immune dysregulation.11,12 Interestingly, though the mechanisms by which UV radiation may contribute to the pathophysiology of rosacea are well described, it remains unclear whether chronic UV exposure plays a major role in the pathogenesis or disease progression of rosacea.1 Studies have observed that increased exposure to sunlight seems to be correlated with increased severity of redness but not of papules and pustules.13,14

Despite some uncertainty regarding the relationship between rosacea and chronic UV exposure, sun protection is a prudent recommendation in this patient population, particularly given other risks of exposure to UV radiation, such as photoaging and skin cancer.9,15,16 Sun protection can be accomplished using broad-spectrum sunscreen (sun protection factor 50 or higher, reapplied every 2 to 4 hours) or by wearing physical protection (eg, hats, sun-protective clothing) along with avoidance of sun exposure during peak UV hours (ie, 10 am-

Temperature Fluctuation

Both heat and cold exposure have been suggested as triggers for rosacea, thought to be mediated through dysregulations in neurovascular and thermal pathways, resulting in increased flushing and erythema.6 Skin affected by rosacea exhibits a lower threshold for temperature and pain stimuli, resulting in heightened hypersensitivity compared to normal skin.18 Exposure to heat activates thermosensitive receptors found in neuronal and nonneuronal tissues, triggering the release of vasoactive neuropeptides.1 Among these, transient receptor potential (TRP) channels seem to play a crucial role in neurovascular reactivity and have been studied in the pathophysiology of rosacea.1,8 Overexpression or excessive stimulation of TRPs by various environmental triggers, such as heat or cold, leads to increased neuropeptide production, ultimately contributing to persistent erythema and vascular dysfunction, as well as a burning or stinging sensation.1,2 Moreover, rapid temperature changes, such as moving from freezing outdoor conditions into a heated environment, may also trigger flushing due to sudden vasodilation.2

Adopting behavioral strategies such as preventing overheating, minimizing sudden temperature shifts, and protecting the skin from cold can help reduce rosacea flare-ups, particularly flushing. For patients who do not achieve sufficient relief through lifestyle modifications alone, targeted pharmacologic treatments are available to help manage these symptoms. Topical α-adrenergic agonists (eg, brimonidine, oxymetazoline) are effective in reducing erythema and flushing by causing vasoconstriction.15,19 For persistent erythema and telangiectasias, pulsed dye laser and intense pulsed light therapies can be effective treatments, as they target hemoglobin in blood vessels, leading to their destruction and a subsequent reduction in erythema.20 Other medications such as topical metronidazole, azelaic acid, calcitonin-gene related peptide inhibitors, and systemic ß-blockers also can be used to treat flushing and redness.15,21

Skin Care Practices

Due to the increased tissue inflammation and potential skin barrier dysfunction, rosacea-affected skin is highly sensitive, and skin care practices or products that disrupt the already compromised skin barrier can contribute to flare-ups. General recommendations should include use of gentle cleansers and moisturizers to prevent dry skin and improve skin barrier function22 as well as avoidance of ingredients that are common irritants and inducers of allergic contact dermatitis (eg, fragrances).9

Cleansing the face should be limited to 1 to 2 times daily, as excessive cleansing and use of harsh formulations with exfoliative ingredients can lead to skin irritation and worsening of symptoms.9 Overcleansing can lead to alterations in cutaneous pH and strip the stratum corneum of healthy components such as lipids and natural moisturizing factors. Common ingredients in cleansers that should be avoided due to their irritant nature include alcohol, acetone, benzyl alcohol, propylene glycol, and α- and ß-hydroxy acids. Instead, syndet (synthetic detergent) cleansers that contain ceramides, hyaluronic acid, or other hydrating agents with a near-physiological pH can be helpful for dry and sensitive skin.23 Toners with high alcohol content and astringent-based products also should be avoided.

Optimal moisturizers for rosacea-affected skin should contain physiologic lipids that help replace a healthy skin barrier as well as relieve dryness and seal in moisture. Beneficial barrier-restoring ingredients include ceramides, dimethicone, cholesterol, and free fatty acids as well as humectants such as glycerin and hyaluronic acid.9,23,24 Applying moisturizer immediately after cleansing and prior to the application of any topical treatments also can help decrease irritation.

As mentioned previously, sun protection is a cornerstone in the management of rosacea and can help reduce redness and skin irritation. Using combination formulas, such as moisturizers with a sun protection factor of at least 50, can be effective.25 Additionally, products with antioxidant or anti-inflammatory ingredients such as niacinamide and allantoin can further support skin health. Lastly, formulations containing green pigments may also be beneficial, as they provide cosmetic camouflage to neutralize redness.26

Dietary Factors

Several dietary factors have been proposed as triggers for rosacea, but conclusive evidence remains limited.27 Foods and beverages that generate heat (eg, hot drinks, spicy foods) may exacerbate rosacea by causing vasodilation and stimulating TRP channels, resulting in flushing.18 While capsaicin, found in spicy foods, may lead to flushing through similar activation of TRP channels, current evidence has not proved a specific and consistent role in the pathogenesis of rosacea.18,27 Similarly, cinnamaldehyde, found in cinnamon and many commercial cinnamon-containing foods as well as various fruits and vegetables, activates thermosensitive receptors that may worsen rosacea symptoms.28 Other potential triggers include histamine-rich foods (eg, avocados, bananas, dried fruits, nuts, smoked fish, aged cheeses), which can lead to skin hypersensitivity and flushing, and formaldehyde-containing foods (eg, apples, carrots, cauliflower, shiitake mushrooms, fish), though the role these types of foods play in rosacea remains unclear.1,29-31

The relationship between caffeine and rosacea is complex. While caffeine commonly is found in coffee, tea, and soda, some studies have suggested that coffee consumption may reduce rosacea risk due to its vasoconstrictive and anti-inflammatory effects.28,32 In contrast, alcohol—particularly white wine and liquor—has been associated with increased rosacea risk due to its effect on vasodilation, inflammation, and oxidative stress.33 Despite anecdotal reports, the role of dairy products in rosacea remains unclear, with conflicting studies suggesting dairy consumption may exacerbate or protect against rosacea.27,28 Given the variability in dietary triggers, patients with rosacea may benefit from using a dietary journal to identify and avoid foods that exacerbate their symptoms, though more research is needed to establish clear recommendations.

Conclusion

Rosacea is a complex condition influenced by genetic, immune, microbial, and environmental factors. Triggers such as UV exposure, temperature fluctuations, alterations in the skin microbiome, and diet contribute to disease exacerbation through mechanisms like vasodilation, neurogenic inflammation, and immune dysregulation. These triggers often interact, compounding their effects and making symptom management more challenging and multifaceted.

Successful rosacea treatment relies on identifying and minimizing patient-specific triggers, as lifestyle modifications can reduce flare-ups and improve outcomes. When combined with interventional, oral, and topical therapies, these adjustments enhance treatment effectiveness and contribute to better long-term disease control. Clinicians should adopt a personalized holistic approach by educating patients on common triggers, recommending lifestyle changes, and integrating medical treatments as necessary. Future research should continue exploring the relationships between rosacea and environmental factors to develop more targeted and evidence-based recommendations.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885.

- Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:282-289. doi:10.1111/bjd.16481

- Chamaillard M, Mortemousque B, Boralevi F, et al. Cutaneous and ocular signs of childhood rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:167-171.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos H, et al. Risk factors associated with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:565-571.

- Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Steinhoff M, et al. Rosacea: the cytokine and chemokine network. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:40-47.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

- Morgado‐Carrasco D, Granger C, Trullas C, et al. Impact of ultraviolet radiation and exposome on rosacea: key role of photoprotection in optimizing treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3415-3421.

- Suhng E, Kim BH, Choi YW, et al. Increased expression of IL‐33 in rosacea skin and UVB‐irradiated and LL‐37‐treated HaCaT cells. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:1023-1029.

- Tisma VS, Basta-Juzbasic A, Jaganjac M, et al. Oxidative stress and ferritin expression in the skin of patients with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:270-276.

- Kulkarni NN, Takahashi T, Sanford JA, et al. Innate immune dysfunction in rosacea promotes photosensitivity and vascular adhesion molecule expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:645-655.E6.

- Bae YI, Yun SJ, Lee JB, et al. Clinical evaluation of 168 Korean patients with rosacea: the sun exposure correlates with the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:243-249.

- McAleer, MA, Fitzpatrick P, Powell FC. Papulopustular rosacea: prevalence and relationship to photodamage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:33-39.

- Van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1754-1764.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:761-770.

- Nichols K, Desai N, Lebwohl MG. Effective sunscreen ingredients and cutaneous irritation in patients with rosacea. Cutis. 1998;61:344-346.

- Guzman-Sanchez DA, Ishiuji Y, Patel T, et al. Enhanced skin blood flow and sensitivity to noxious heat stimuli in papulopustular rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:800-805.

- Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol.2019;181:65-79.

- Wienholtz NKF, Christensen CE, Do TP, et al. Erenumab for treatment of persistent erythema and flushing in rosacea: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol.2024;160:612-619.

- Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 1: a status report on the disease state, general measures, and adjunctive skin care. Cutis. 2013;92:234-240.

- Baldwin H, Alexis AF, Andriessen A, et al. Evidence of barrier deficiency in rosacea and the importance of integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:384-392.

- Schlesinger TE, Powell CR. Efficacy and tolerability of low molecular weight hyaluronic acid sodium salt 0.2% cream in rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:664-667.

- Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902-910.E2.

- Draelos ZD. Cosmeceuticals for rosacea. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:213-217.

- Yuan X, Huang X, Wang B, et al. Relationship between rosacea and dietary factors: a multicenter retrospective case–control survey. J Dermatol. 2019;46:219-225.

- Alia E, Feng H. Rosacea pathogenesis, common triggers, and dietary role: the cause, the trigger, and the positive effects of different foods. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:122-127.

- Branco ACCC, Yoshikawa FSY, Pietrobon AJ, et al. Role of histamine in modulating the immune response and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:1-10.

- Darrigade A, Dendooven E, Aerts O. Contact allergy to fragrances and formaldehyde contributing to papulopustular rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:395-397.

- Linauskiene K, Isaksson M. Allergic contact dermatitis from formaldehyde mimicking impetigo and initiating rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:359-361.

- Al Reef T, Ghanem E. Caffeine: well-known as psychotropic substance, but little as immunomodulator. Immunobiology. 2018;223:818-825.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Rosacea and alcohol intake. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:E25.

- Steinhoff M, Schauber J, Leyden JJ. New insights into rosacea pathophysiology: a review of recent findings. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S15-S26.

- Buddenkotte J, Steinhoff M. Recent advances in understanding and managing rosacea. F1000Res. 2018;7:F1000 Faculty Rev-1885.

- Gether L, Overgaard LK, Egeberg A, et al. Incidence and prevalence of rosacea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Dermatol. 2018;179:282-289. doi:10.1111/bjd.16481

- Chamaillard M, Mortemousque B, Boralevi F, et al. Cutaneous and ocular signs of childhood rosacea. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144:167-171.

- Abram K, Silm H, Maaroos H, et al. Risk factors associated with rosacea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2010;24:565-571.

- Gerber PA, Buhren BA, Steinhoff M, et al. Rosacea: the cytokine and chemokine network. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:40-47.

- Steinhoff M, Buddenkotte J, Aubert J, et al. Clinical, cellular, and molecular aspects in the pathophysiology of rosacea. J Investig Dermatol Symp Proc. 2011;15:2-11.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:749-758.

- Morgado‐Carrasco D, Granger C, Trullas C, et al. Impact of ultraviolet radiation and exposome on rosacea: key role of photoprotection in optimizing treatment. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2021;20:3415-3421.

- Suhng E, Kim BH, Choi YW, et al. Increased expression of IL‐33 in rosacea skin and UVB‐irradiated and LL‐37‐treated HaCaT cells. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27:1023-1029.

- Tisma VS, Basta-Juzbasic A, Jaganjac M, et al. Oxidative stress and ferritin expression in the skin of patients with rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:270-276.

- Kulkarni NN, Takahashi T, Sanford JA, et al. Innate immune dysfunction in rosacea promotes photosensitivity and vascular adhesion molecule expression. J Invest Dermatol. 2020;140:645-655.E6.

- Bae YI, Yun SJ, Lee JB, et al. Clinical evaluation of 168 Korean patients with rosacea: the sun exposure correlates with the erythematotelangiectatic subtype. Ann Dermatol. 2009;21:243-249.

- McAleer, MA, Fitzpatrick P, Powell FC. Papulopustular rosacea: prevalence and relationship to photodamage. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;63:33-39.

- Van Zuuren EJ. Rosacea. N Engl J Med. 2017;377:1754-1764.

- Two AM, Wu W, Gallo RL, et al. Rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;72:761-770.

- Nichols K, Desai N, Lebwohl MG. Effective sunscreen ingredients and cutaneous irritation in patients with rosacea. Cutis. 1998;61:344-346.

- Guzman-Sanchez DA, Ishiuji Y, Patel T, et al. Enhanced skin blood flow and sensitivity to noxious heat stimuli in papulopustular rosacea. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007;57:800-805.

- Fowler J Jr, Jackson M, Moore A, et al. Efficacy and safety of once-daily topical brimonidine tartrate gel 0.5% for the treatment of moderate to severe facial erythema of rosacea: results of two randomized, double-blind, and vehicle-controlled pivotal studies. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:650-656.

- van Zuuren EJ, Fedorowicz Z, Tan J, et al. Interventions for rosacea based on the phenotype approach: an updated systematic review including GRADE assessments. Br J Dermatol.2019;181:65-79.

- Wienholtz NKF, Christensen CE, Do TP, et al. Erenumab for treatment of persistent erythema and flushing in rosacea: a nonrandomized controlled trial. JAMA Dermatol.2024;160:612-619.

- Del Rosso JQ, Thiboutot D, Gallo R, et al. Consensus recommendations from the American Acne & Rosacea Society on the management of rosacea, part 1: a status report on the disease state, general measures, and adjunctive skin care. Cutis. 2013;92:234-240.

- Baldwin H, Alexis AF, Andriessen A, et al. Evidence of barrier deficiency in rosacea and the importance of integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2021;20:384-392.

- Schlesinger TE, Powell CR. Efficacy and tolerability of low molecular weight hyaluronic acid sodium salt 0.2% cream in rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2013;12:664-667.

- Williams JD, Maitra P, Atillasoy E, et al. SPF 100+ sunscreen is more protective against sunburn than SPF 50+ in actual use: results of a randomized, double-blind, split-face, natural sunlight exposure clinical trial. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:902-910.E2.

- Draelos ZD. Cosmeceuticals for rosacea. Clin Dermatol. 2017;35:213-217.

- Yuan X, Huang X, Wang B, et al. Relationship between rosacea and dietary factors: a multicenter retrospective case–control survey. J Dermatol. 2019;46:219-225.

- Alia E, Feng H. Rosacea pathogenesis, common triggers, and dietary role: the cause, the trigger, and the positive effects of different foods. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:122-127.

- Branco ACCC, Yoshikawa FSY, Pietrobon AJ, et al. Role of histamine in modulating the immune response and inflammation. Mediators Inflamm. 2018;2018:1-10.

- Darrigade A, Dendooven E, Aerts O. Contact allergy to fragrances and formaldehyde contributing to papulopustular rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2019;81:395-397.

- Linauskiene K, Isaksson M. Allergic contact dermatitis from formaldehyde mimicking impetigo and initiating rosacea. Contact Dermatitis. 2018;78:359-361.

- Al Reef T, Ghanem E. Caffeine: well-known as psychotropic substance, but little as immunomodulator. Immunobiology. 2018;223:818-825.

- Drago F, Ciccarese G, Herzum A, et al. Rosacea and alcohol intake. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:E25.

Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers of Rosacea

Environmental and Lifestyle Triggers of Rosacea

PRACTICE POINTS

- It is important to routinely assess and individualize rosacea management by encouraging use of symptom and trigger diaries to guide lifestyle modifications.

- Patients with rosacea should be encouraged to use mild, fragrance-free cleansers, barrier-supporting moisturizers, and daily broad-spectrum sunscreen and to avoid common irritants.

- Address flushing and erythema with behavioral and medical strategies; counsel patients on minimizing abrupt temperature shifts and consider topical Symbolα-adrenergic agonists, anti-inflammatory agents, or laser therapies when lifestyle measures alone are insufficient.

- Lifestyle recommendations (eg, optimal skin care practices, avoidance of dietary triggers) should be incorporated in treatment plans.

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

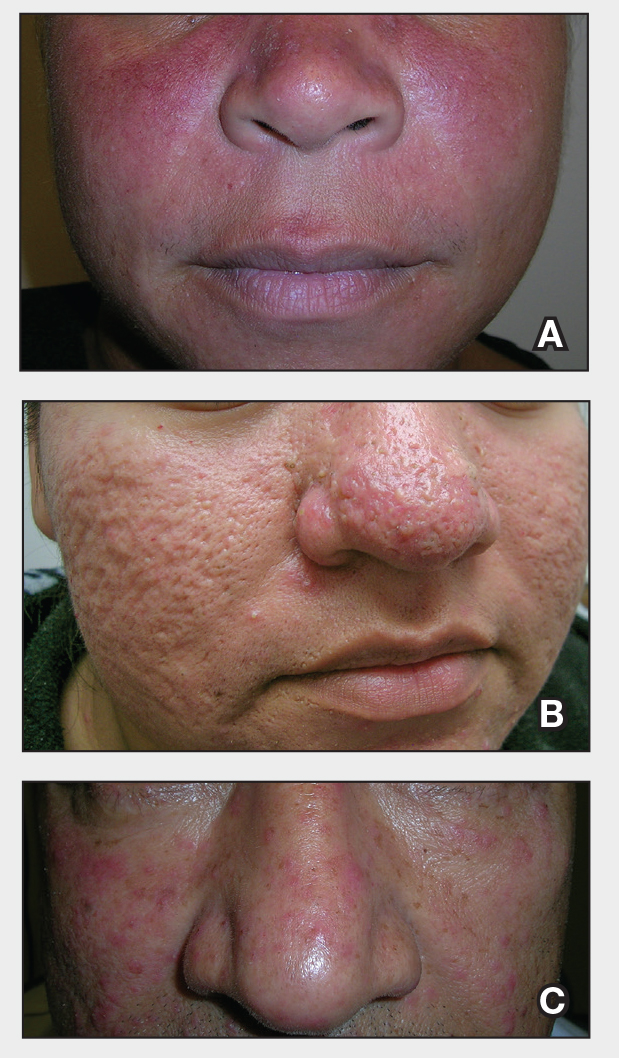

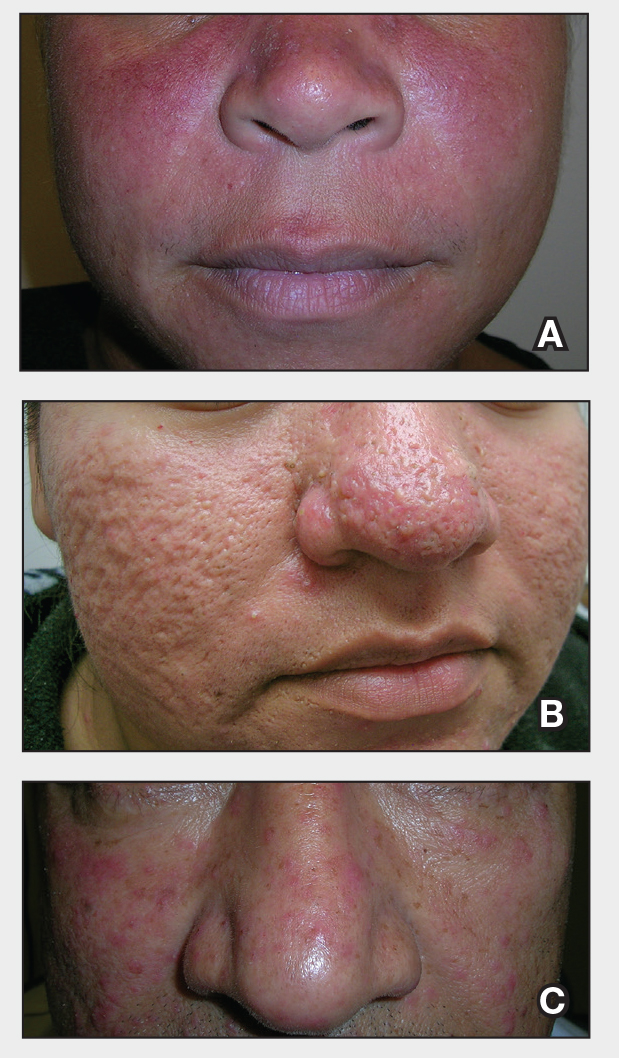

THE COMPARISON:

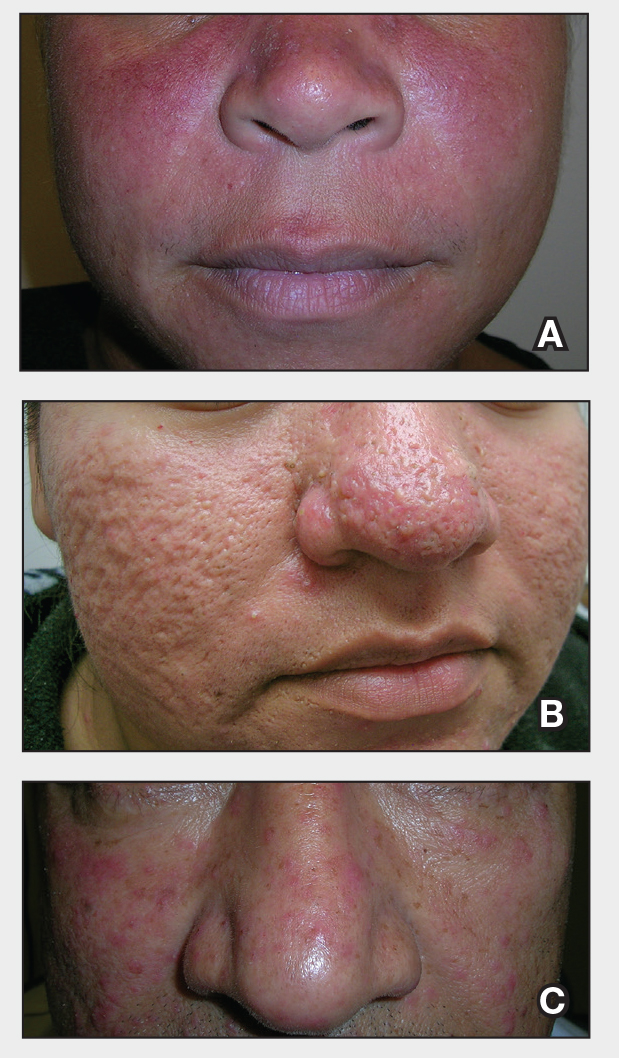

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

THE COMPARISON:

- A. Erythematotelangiectatic rosacea in a polygonal vascular pattern on the cheeks in a Black woman who also has eyelid hypopigmentation due to vitiligo.

- B. Rhinophymatous rosacea in a Hispanic woman who also has papules and pustules on the chin and upper lip region as well as facial scarring from severe inflammatory acne during her teen years.

- C. Papulopustular rosacea in a Hispanic man.

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory condition characterized by facial flushing and persistent erythema of the central face, typically affecting the cheeks and nose. It also may manifest with papules, pustules, and telangiectasias. The 4 main subtypes of rosacea are erythematotelangiectatic, papulopustular, phymatous (involving thickening of the skin, often of the nose), and ocular (dry, itchy, or irritated eyes).1 Patients also may report stinging, burning, dryness, and edema.2 The etiology of rosacea is unclear but is believed to involve immune dysfunction, neurovascular dysregulation, certain microorganisms, and genetic predisposition.1,2

Epidemiology

Rosacea often is associated with fair skin and more frequently is reported in individuals of Northern European descent.1,2 While it may be less common in darker skin types, rosacea is not rare in patients with skin of color (SOC). A review of US outpatient data from 1993 to 2010 found that 2% of patients with rosacea were Black, 2.3% were Asian or Pacific Islander, and 3.9% were Hispanic or Latino.3 Global estimates suggest that up to 40 million individuals with SOC may be affected by rosacea,4 with the reported prevalence as high as 10%.2 Although early research linked rosacea primarily to adults older than 30 years, newer data show peak prevalence between ages 25 to 39 years, suggesting that younger adults may be affected more than previously recognized.5

Key Clinical Features

In addition to the traditional subtypes, updated guidelines recommend a phenotype- based approach to diagnosing rosacea focusing on observable features such as persistent redness in the central face and thickened skin rather than classifying patients into broad categories. A diagnosis can be made when at least one diagnostic feature is present (eg, fixed facial erythema or phymatous changes) or when 2 or more major features are observed (eg, papules, pustules, flushing, visible blood vessels, or ocular findings).6

In individuals with darker skin types, erythema may not be bright red; rather, the skin may appear pink, reddish-brown, violaceous, or dusky brown.7 Postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, which is common in darker skin tones, can further mask erythema.2 Pressing a microscope slide or magnifying glass against the skin can help assess for blanching, which is indicative of erythema. Telangiectasias also may be more challenging to appreciate in patients with SOC and typically require bright, shadow-free lighting or dermoscopy for detection.2

Skin thickening across the cheeks and nose with overlying acneform papules can be diagnostic clues of rosacea in darker skin types and help distinguish it from acne.2 It also is important to distinguish rosacea from systemic lupus erythematosus, which typically manifests as a malar rash that spares the nasolabial folds and is nonpustular. If uncertain, consider serologic testing for antinuclear antibodies, patch testing, or biopsy.8

Worth Noting

Treatment of rosacea is focused on managing symptoms and reducing flares. First-line strategies include behavioral modifications and trigger avoidance, such as minimizing sun exposure and avoiding consumption of alcohol and spicy foods.9 Gentle skin care practices are essential, including the use of light, fragrance-free, nonirritating cleansers and moisturizers at least once daily. Application of sunscreen with an SPF of at least 30 also is routinely recommended.9,10 Additionally, patients should be counseled to avoid harsh cleansers, such as exfoliants, astringents, and chemicals that may further diminish the skin barrier.10

Treatment options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for rosacea include oral doxycycline, oral minocycline, topical brimonidine, oxymetazoline, ivermectin, metronidazole, azelaic acid, sodium sulfacetamide/sulfur, encapsulated benzoyl peroxide cream, and minocycline.11-13

Topical treatment options commonly used off-label for rosacea include topical clindamycin, topical retinoids, and azithromycin. Oral tetracyclines should be avoided in children and pregnant women; instead, oral erythromycin and topical metronidazole commonly are used.14

Laser or intense pulsed light therapy may be considered, although results have been mixed, and the long-term benefits are uncertain. Given the higher risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation in patients with SOC, these modalities should be used cautiously.15 Among the available options, the Nd:YAG laser is preferred in darker skin types due to its safety profile.16 A small case series reported successful CO2 laser treatment for rhinophyma in patients with melanated skin; however, some patients developed localized scarring, suggesting that conservative depth settings should be used to reduce risk for this adverse event.17

Health Disparity Highlight

Rosacea may be underdiagnosed in individuals with darker skin types,2,15,18 likely due in part to reduced contrast between erythema and background skin tone, which can make features such as flushing and telangiectasias harder to appreciate.1,10,15

Although tools to assess erythema exist, they rarely are used in everyday clinical practice.10 In patients with deeply pigmented skin, ensuring adequate examination room lighting and using dermoscopy can help identify any subtle vascular or textural changes localized across the central face. While various imaging techniques are used in clinical trials to monitor treatment response, few have been studied and optimized across a wide range of skin tones.10 There is a need for dermatologic assessment tools that better capture the degree of erythema, inflammation, and vascular features of rosacea in pigmented skin. Emerging research is focused on developing more equitable imaging technologies.19

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

- Rainer BM, Kang S, Chien AL. Rosacea: epidemiology, pathogenesis, and treatment. Dermatoendocrinol. 2017;9:E1361574.

- Alexis AF, Callender VD, Baldwin HE, et al. Global epidemiology and clinical spectrum of rosacea, highlighting skin of color: review and clinical practice experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1722-1729.e7.

- Al-Dabagh A, Davis SA, McMichael AJ, el al. Rosacea in skin of color: not a rare diagnosis. Dermatol Online J. 2014;20:13030/qt1mv9r0ss.

- Tan J, Berg M. Rosacea: current state of epidemiology. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2013;69(6 suppl 1):S27-S35.

- Saurat JH, Halioua B, Baissac C, et al. Epidemiology of acne and rosacea: a worldwide global study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;90:1016-1018.

- Gallo RL, Granstein RD, Kang S, et al. Standard classification and pathophysiology of rosacea: the 2017 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;78:148-155.

- Finlay AY, Griffiths TW, Belmo S, et al. Why we should abandon the misused descriptor ‘erythema’. Br J Dermatol. 2021;185:1240-1241.

- Callender VD, Barbosa V, Burgess CM, et al. Approach to treatment of medical and cosmetic facial concerns in skin of color patients. Cutis. 2017;100:375-380.

- Baldwin H, Alexis A, Andriessen A, et al. Supplement article: skin barrier deficiency in rosacea: an algorithm integrating OTC skincare products into treatment regimens. J Drugs Dermatol. 2022;21:SF3595563-SF35955610.

- Ohanenye C, Taliaferro S, Callender VD. Diagnosing disorders of facial erythema. Dermatol Clin. 2023;41:377-392.

- Thiboutot D, Anderson R, Cook-Bolden F, et al. Standard management options for rosacea: the 2019 update by the National Rosacea Society Expert Committee. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82:1501-1510.

- Del Rosso JQ, Schlessinger J, Werschler P. Comparison of anti-inflammatory dose doxycycline versus doxycycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea. J Drugs Dermatol. 2008;7:573-576.

- van der Linden MMD, van Ratingen AR, van Rappard DC, et al. DOMINO, doxycycline 40 mg vs. minocycline 100 mg in the treatment of rosacea: a randomized, single-blinded, noninferiority trial, comparing efficacy and safety. Br J Dermatol. 2017;176:1465-1474.

- Geng R, Bourkas A, Sibbald RG, et al. Efficacy of treatments for rosacea in the pediatric population: a systematic review. JEADV Clinical Practice. 2024;3:17-48.

- Sarkar R, Podder I, Jagadeesan S. Rosacea in skin of color: a comprehensive review. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:611-621.

- Chen A, Choi J, Balazic E, et al. Review of laser and energy-based devices to treat rosacea in skin of color. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2024;26:43-53.

- Nganzeu CG, Lopez A, Brennan TE. Ablative CO2 laser treatment of rhinophyma in people of color: a case series. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open. 2025;13:E6616.

- Kulthanan K, Andriessen A, Jiang X, et al. A review of the challenges and nuances in treating rosacea in Asian skin types using cleansers and moisturizers as adjuncts. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22:45-53.

- Jarang A, McGrath Q, Harunani M, et al. Multispectral SWIR imaging for equitable pigmentation-insensitive assessment of inflammatory acne in darkly pigmented skin. Presented at Photonics in Dermatology and Plastic Surgery 2025; January 25-27, 2025; San Francisco, California.

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

Don’t Miss These Signs of Rosacea in Darker Skin Types

The Skin Microbiome in Rosacea: Mechanisms, Gut-Skin Interactions, and Therapeutic Implications

The Skin Microbiome in Rosacea: Mechanisms, Gut-Skin Interactions, and Therapeutic Implications

Rosacea is a chronic inflammatory skin condition affecting the central face—including the cheeks, nose, chin, and forehead—that causes considerable discomfort.1 Its pathogenesis involves immune dysregulation, genetic predisposition, and microbial dysbiosis.2 While immune and environmental factors are known triggers of rosacea, recent research highlights the roles of the gut and skin microbiomes in disease progression. While the skin microbiome interacts directly with the immune system to regulate inflammation and skin homeostasis, the gut microbiome also influences cutaneous inflammation, emphasizing the need to address both topical and internal microbiome imbalances.3 In this article, we review gut and skin microbial alterations in rosacea, focusing on the skin microbiome and including the gut-skin axis implications as well as therapeutic strategies aimed at microbiome balance to enhance patient outcomes.

Skin Microbiome Alterations in Rosacea

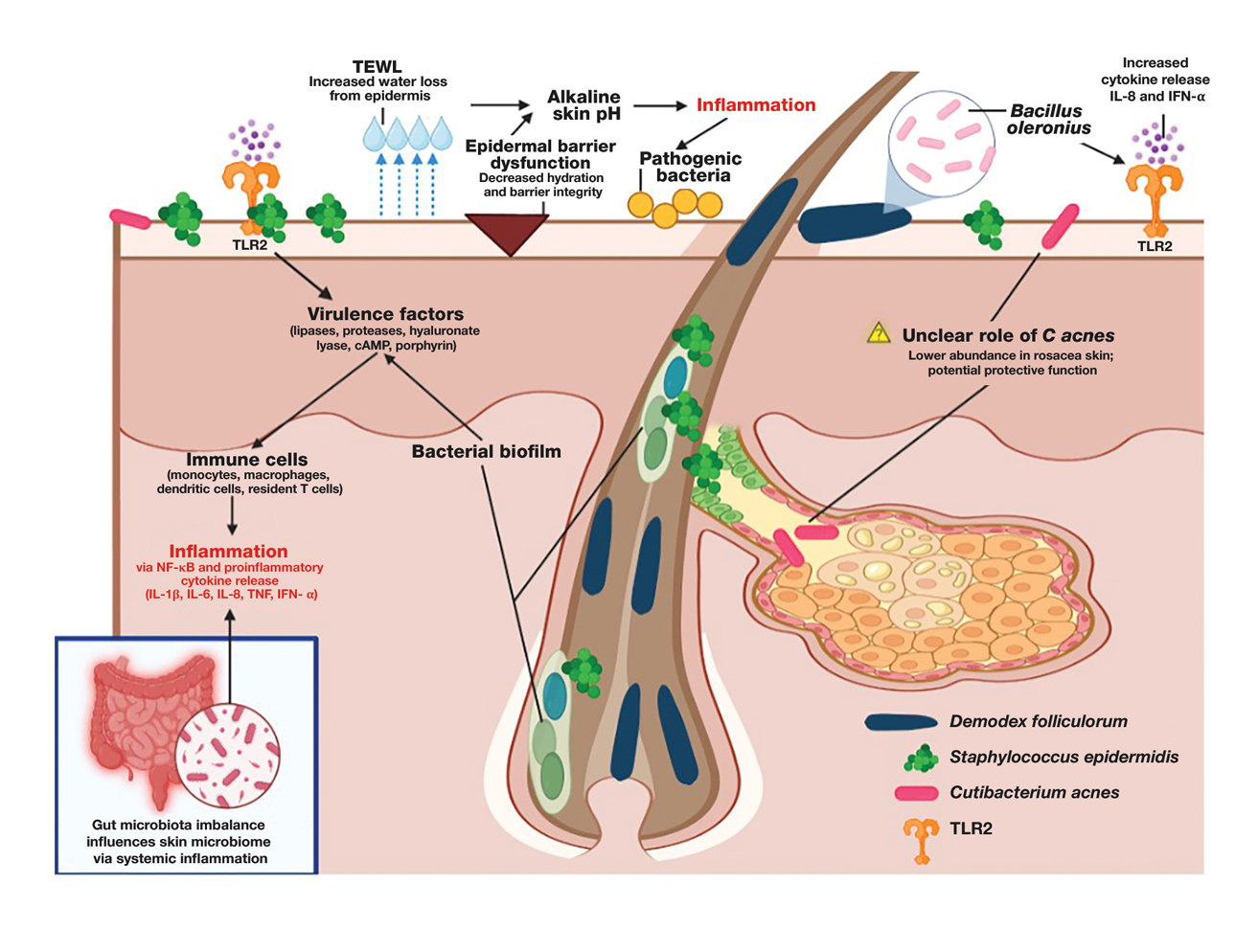

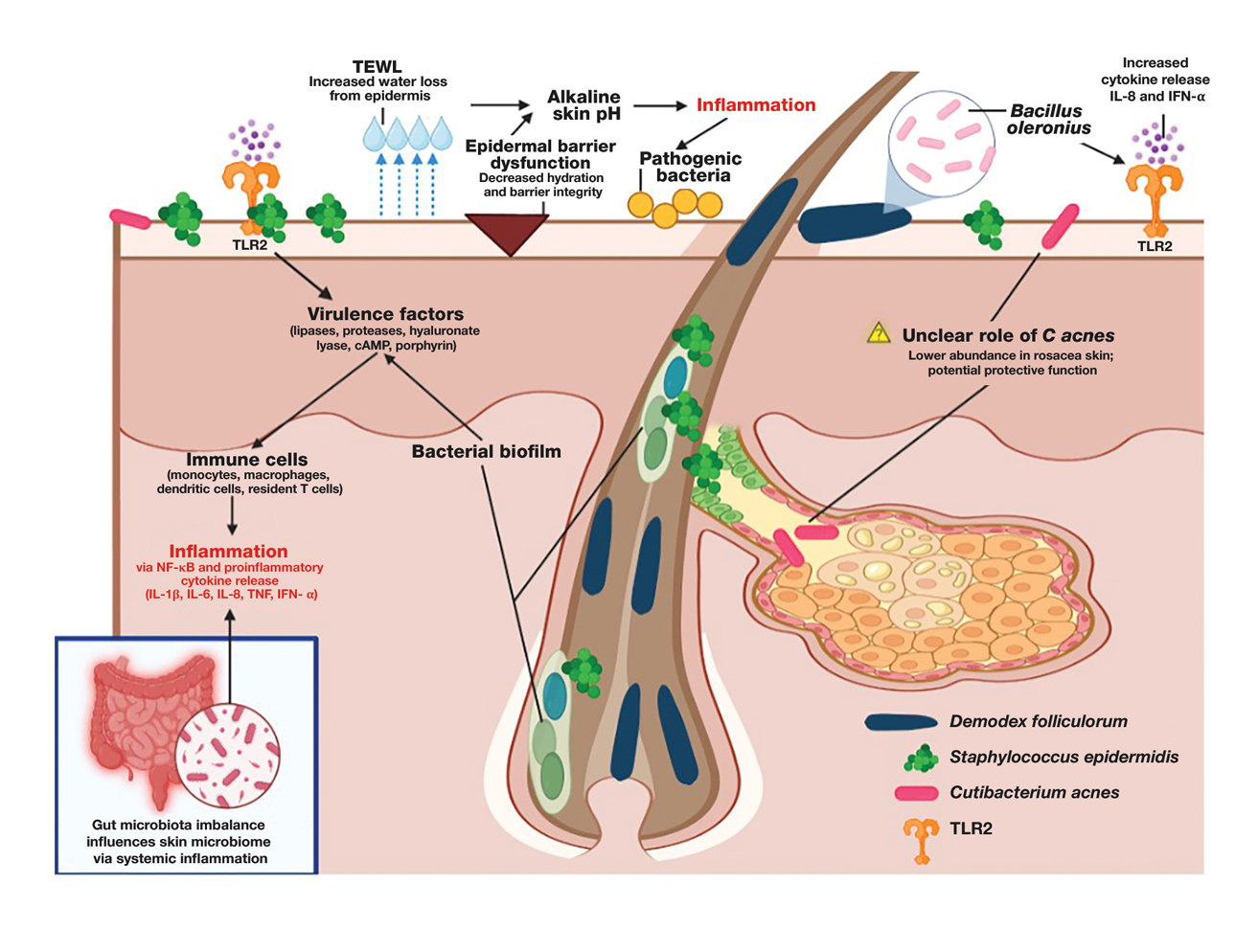

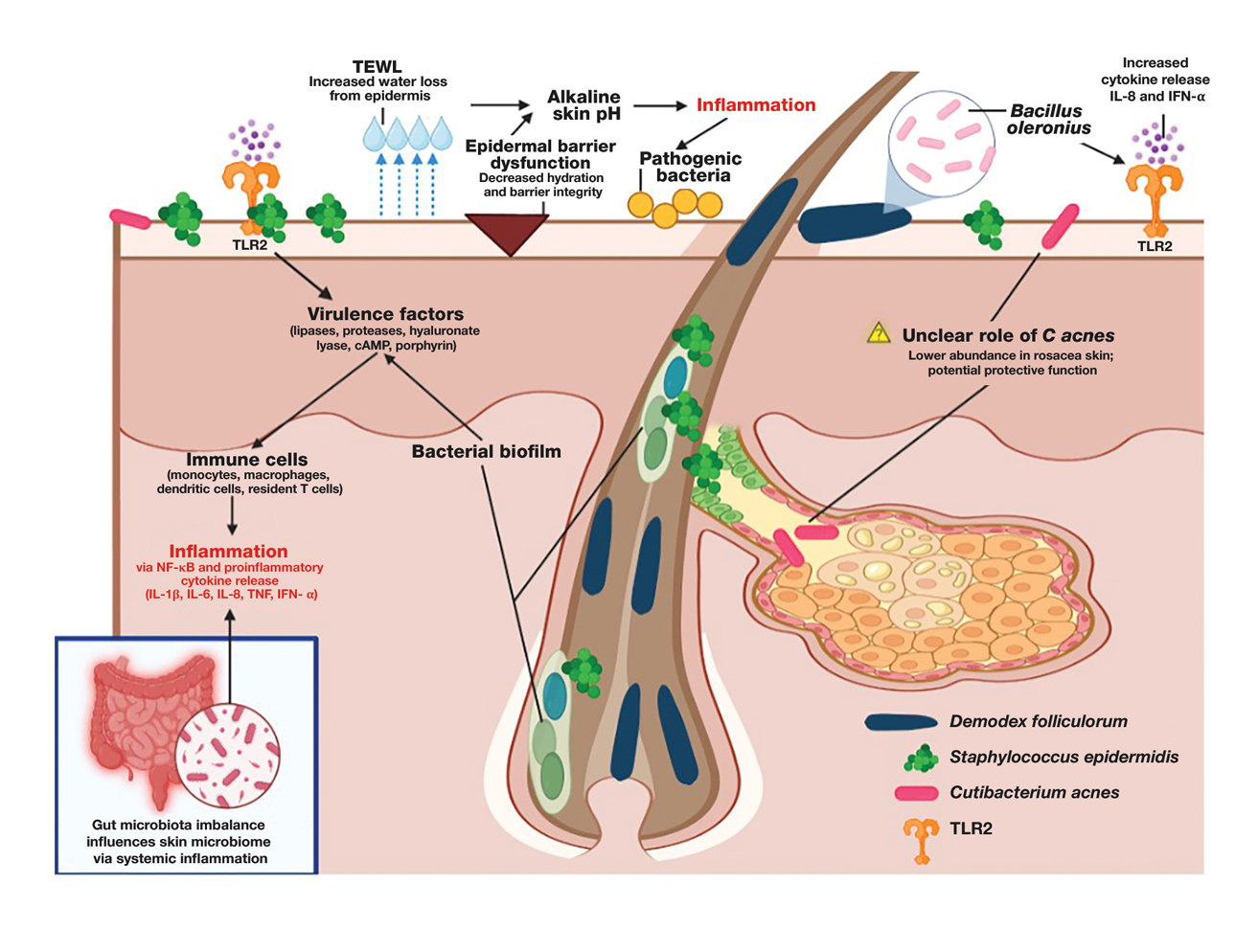

The human skin microbiome interacts with the immune system, and microbial imbalances have been shown to contribute to immune dysregulation. Several key microbial species have been identified as playing a large role in rosacea, including Demodex folliculorum, Staphylococcus epidermidis, Bacillus oleronius, and Cutibacterium acnes (Figure).

Demodex folliculorum is a microscopic mite is found in hair follicles and sebaceous glands. Patients with rosacea have higher densities of D folliculorum, which trigger follicular occlusion and immune activation.1 Bacillus oleronius be isolated from D folliculorum and can further activate toll-like receptor 2, leading to cytokine production and immune cell infiltration.3,4 Increased propagation of this mite correlates with shifts in skin microbiome composition, demonstrating increased inflammatory microbial populations.3

Staphylococcus epidermidis normally is commensal but can become pathogenic (pathobiont) in rosacea due to disruptions in the skin microenvironment, where it can form biofilms and produce virulence factors, particularly in papulopustular rosacea.5