User login

Physicians assume myriad leadership roles within medical institutions. Clinically‐oriented leadership roles can range from managing a small group of providers, to leading entire health systems, to heading up national quality improvement initiatives. While often competent in the practice of medicine, many physicians have not pursued structured management or administrative training. In a survey of Medicine Department Chairs at academic medical centers, none had advanced management degrees despite spending an average of 55% of their time on administrative duties. It is not uncommon for physicians to attend leadership development programs or management seminars, as evidenced by the increasing demand for education.1 Various methods for skill enhancement have been described24; however, the most effective approaches have yet to be determined.

Miller and Dollard5 and Bandura6, 7 have explained that behavioral contracts have evolved from social cognitive theory principles. These contracts are formal written agreements, often negotiated between 2 individuals, to facilitate behavior change. Typically, they involve a clear definition of expected behaviors with specific consequences (usually positive reinforcement).810 Their use in modifying physician behavior, particularly those related to leadership, has not been studied.

Hospitalist physicians represent the fastest growing specialty in the United States.11, 12 Among other responsibilities, they have taken on roles as leaders in hospital administration, education, quality improvement, and public health.1315 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the largest US organization committed to the practice of hospital medicine,16 has established Leadership Academies to prepare hospitalists for these duties. The goal of this study was to assess how hospitalist physicians' commitment to grow as leaders was expressed using behavioral contacts as a vehicle to clarify their intentions and whether behavioral change occurred over time.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative study design was selected to explore how current and future hospitalist leaders planned to modify their behaviors after participating in a hospitalist leadership training course. Participants were encouraged to complete a behavioral contract highlighting their personal goals.

Approximately 12 months later, follow‐up data were collected. Participants were sent copies of their behavioral contracts and surveyed about the extent to which they have realized their personal goals.

Subjects

Hospitalist leaders participating in the 4‐day level I or II leadership courses of the SHM Leadership Academy were studied.

Data Collection

In the final sessions of the 2007‐2008 Leadership Academy courses, participants completed an optional behavioral contract exercise in which they partnered with a colleague and were asked to identify 4 action plans they intended to implement upon their return home. These were written down and signed. Selected demographic information was also collected.

Follow‐up surveys were sent by mail and electronically to a subset of participants with completed behavioral contracts. A 5‐point Likert scale (strongly agree . . . strongly disagree) was used to assess the extent of adherence to the goals listed in the behavioral contracts.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using an editing organizing style, a qualitative analysis technique to find meaningful units or segments of text that both stand on their own and relate to the purpose of the study.12 With this method, the coding template emerges from the data. Two investigators independently analyzed the transcripts and created a coding template based on common themes identified among the participants. In cases of discrepant coding, the 2 investigators had discussions to reach consensus. The authors agreed on representative quotes for each theme. Triangulation was established through sharing results of the analysis with a subset of participants.

Follow‐up survey data was summarized descriptively showing proportion data.

Results

Response Rate and Participant Demographics

Out of 264 people who completed the course, 120 decided to participate in the optional behavioral contract exercise. The median age of participants was 38 years (Table 1). The majority were male (84; 70.0%), and hospitalist leaders (76; 63.3%). The median time in practice as a hospitalist was 4 years. Fewer than one‐half held an academic appointment (40; 33.3%) with most being at the rank of Assistant Professor (14; 11.7%). Most of the participants worked in a private hospital (80; 66.7%).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age in years [median (SD)] | 38 (8) |

| Male [n (%)] | 84 (70.0) |

| Years in practice as hospitalist [median (SD)] | 4 (13) |

| Leader of hospitalist program [n (%)] | 76 (63.3) |

| Academic affiliation [n (%)] | 40 (33.3) |

| Academic rank [n (%)] | |

| Instructor | 9 (7.5) |

| Assistant professor | 14 (11.7) |

| Associate professor | 13 (10.8) |

| Hospital type [n (%)] | |

| Private | 80 (66.7) |

| University | 15 (12.5) |

| Government | 2 (1.7) |

| Veterans administration | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) |

Results of Qualitative Analysis of Behavioral Contracts

From the analyses of the behavioral contracts, themes emerged related to ways in which participants hoped to develop and improve. The themes and the frequencies with which they were recorded in the behavioral contracts are shown in Table 2.

| Theme | Total Number of Times Theme Mentioned in All Behavioral Contracts | Number of Respondents Referring to Theme [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Improving communication and interpersonal skills | 132 | 70 (58.3) |

| Refinement of vision, goals, and strategic planning | 115 | 62 (51.7) |

| Improve intrapersonal development | 65 | 36 (30.0) |

| Enhance negotiation skills | 65 | 44 (36.7) |

| Commit to organizational change | 53 | 32 (26.7) |

| Understanding business drivers | 38 | 28 (23.3) |

| Setting performance and clinical metrics | 34 | 26 (21.7) |

| Strengthen interdepartmental relations | 32 | 26 (21.7) |

Improving Communication and Interpersonal Skills

A desire to improve communication and listening skills, particularly in the context of conflict resolution, was mentioned repeatedly. Heightened awareness about different personality types to allow for improved interpersonal relationships was another concept that was emphasized.

One female Instructor from an academic medical center described her intentions:

I will try to do a better job at assessing the behavioral tendencies of my partners and adjust my own style for more effective communication.

Refinement of Vision, Goals, and Strategic Planning

Physicians were committed to returning to their home institutions and embarking on initiatives to advance vision and goals of their groups within the context of strategic planning. Participants were interested in creating hospitalist‐specific mission statements, developing specific goals that take advantage of strengths and opportunities while minimizing internal weaknesses and considering external threats. They described wanting to align the interests of members of their hospitalist groups around a common goal.

A female hospitalist leader in private practice wished to:

Clearly define a group vision and commit to re‐evaluation on a regular basis to ensure we are on track . . . and conduct a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis to set future goals.

Improve Intrapersonal Development

Participants expressed desire to improve their leadership skills. Proposed goals included: (1) recognizing their weaknesses and soliciting feedback from colleagues, (2) minimizing emotional response to stress, (3) sharing their knowledge and skills for the benefit of peers, (4) delegating work more effectively to others, (5) reading suggested books on leadership, (6) serving as a positive role model and mentor, and (7) managing meetings and difficult coworkers more skillfully.

One female Assistant Professor from an academic medical center outlined:

I want to be able to: (1) manage up better and effectively negotiate with the administration on behalf of my group; (2) become better at leadership skills by using the tools offered at the Academy; and (3) effectively support my group members to develop their skills to become successful in their chosen niches. I will . . . improve the poor morale in my group.

Enhance Negotiation Skills

Many physician leaders identified negotiation principles and techniques as foundations for improvement for interactions within their own groups, as well as with the hospital administration.

A male private hospitalist leader working for 4 years as a hospitalist described plans to utilize negotiation skills within and outside the group:

Negotiate with my team of hospitalists to make them more compliant with the rules and regulations of the group, and negotiate an excellent contract with hospital administration. . . .

Commit to Organizational Change

The hospitalist respondents described their ability to influence organizational change given their unique position at the interface between patient care delivery and hospital administration. To realize organizational change, commonly cited ideas included recruitment and retention of clinically excellent practitioners, and developing standard protocols to facilitate quality improvement initiatives.

A male Instructor of Medicine listed select areas in which to become more involved:

Participation with the Chief Executive Officer of the company in quality improvement projects, calls to the primary care practitioners upon discharge, and the handoff process.

Other Themes

The final 3 themes included are: understanding business drivers; the establishment of better metrics to assess performance; and the strengthening of interdepartmental relations.

Follow‐up Data About Adherence to Plans Delineated in Behavioral Contracts

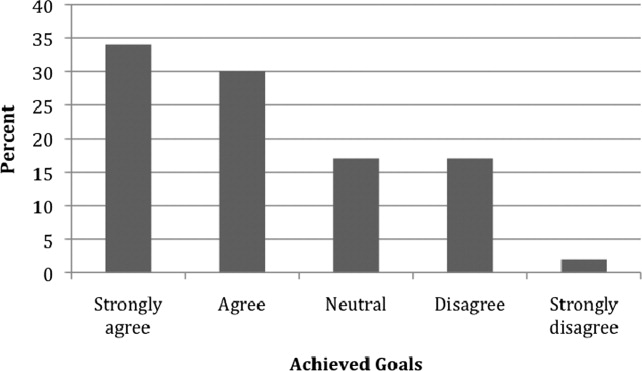

Out of 65 completed behavioral contracts from the 2007 Level I participants, 32 returned a follow‐up survey (response rate 49.3%). Figure 1 shows the extent to which respondents believed that they were compliant with their proposed plans for change or improvement. Degree of adherence was displayed as a proportion of total goals. Out of those who returned a follow‐up survey, all but 1 respondent either strongly agreed or agreed that they adhered to at least one of their goals (96.9%).

Select representative comments that illustrate the physicians' appreciation of using behavioral contracts include:

my approach to problems is a bit more analytical.

simple changes in how I approach people and interact with them has greatly improved my skills as a leader and allowed me to accomplish my goals with much less effort.

Discussion

Through the qualitative analysis of the behavioral contracts completed by participants of a Leadership Academy for hospitalists, we characterized the ways that hospitalist practitioners hoped to evolve as leaders. The major themes that emerged relate not only to their own growth and development but also their pledge to advance the success of the group or division. The level of commitment and impact of the behavioral contracts appear to be reinforced by an overwhelmingly positive response to adherence to personal goals one year after course participation. Communication and interpersonal development were most frequently cited in the behavioral contracts as areas for which the hospitalist leaders acknowledged a desire to grow. In a study of academic department of medicine chairs, communication skills were identified as being vital for effective leadership.3 The Chairs also recognized other proficiencies required for leading that were consistent with those outlined in the behavioral contracts: strategic planning, change management, team building, personnel management, and systems thinking. McDade et al.17 examined the effects of participation in an executive leadership program developed for female academic faculty in medical and dental schools in the United States and Canada. They noted increased self‐assessed leadership capabilities at 18 months after attending the program, across 10 leadership constructs taught in the classes. These leadership constructs resonate with the themes found in the plans for change described by our informants.

Hospitalists are assuming leadership roles in an increasing number and with greater scope; however, until now their perspectives on what skill sets are required to be successful have not been well documented. Significant time, effort, and money are invested into the development of hospitalists as leaders.4 The behavioral contract appears to be a tool acceptable to hospitalist physicians; perhaps it can be used as part annual reviews with hospitalists aspiring to be leaders.

Several limitations of the study shall be considered. First, not all participants attending the Leadership Academy opted to fill out the behavioral contracts. Second, this qualitative study is limited to those practitioners who are genuinely interested in growing as leaders as evidenced by their willingness to invest in going to the course. Third, follow‐up surveys relied on self‐assessment and it is not known whether actual realization of these goals occurred or the extent to which behavioral contracts were responsible. Further, follow‐up data were only completed by 49% percent of those targeted. However, hospitalists may be fairly resistant to being surveyed as evidenced by the fact that SHM's 2005‐2006 membership survey yielded a response rate of only 26%.18 Finally, many of the thematic goals were described by fewer than 50% of informants. However, it is important to note that the elements included on each person's behavioral contract emerged spontaneously. If subjects were specifically asked about each theme, the number of comments related to each would certainly be much higher. Qualitative analysis does not really allow us to know whether one theme is more important than another merely because it was mentioned more frequently.

Hospitalist leaders appear to be committed to professional growth and they have reported realization of goals delineated in their behavioral contracts. While varied methods are being used as part of physician leadership training programs, behavioral contracts may enhance promise for change.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Regina Hess for assistance in data preparation and Laurence Wellikson, MD, FHM, Russell Holman, MD and Erica Pearson (all from the SHM) for data collection.

Physicians assume myriad leadership roles within medical institutions. Clinically‐oriented leadership roles can range from managing a small group of providers, to leading entire health systems, to heading up national quality improvement initiatives. While often competent in the practice of medicine, many physicians have not pursued structured management or administrative training. In a survey of Medicine Department Chairs at academic medical centers, none had advanced management degrees despite spending an average of 55% of their time on administrative duties. It is not uncommon for physicians to attend leadership development programs or management seminars, as evidenced by the increasing demand for education.1 Various methods for skill enhancement have been described24; however, the most effective approaches have yet to be determined.

Miller and Dollard5 and Bandura6, 7 have explained that behavioral contracts have evolved from social cognitive theory principles. These contracts are formal written agreements, often negotiated between 2 individuals, to facilitate behavior change. Typically, they involve a clear definition of expected behaviors with specific consequences (usually positive reinforcement).810 Their use in modifying physician behavior, particularly those related to leadership, has not been studied.

Hospitalist physicians represent the fastest growing specialty in the United States.11, 12 Among other responsibilities, they have taken on roles as leaders in hospital administration, education, quality improvement, and public health.1315 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the largest US organization committed to the practice of hospital medicine,16 has established Leadership Academies to prepare hospitalists for these duties. The goal of this study was to assess how hospitalist physicians' commitment to grow as leaders was expressed using behavioral contacts as a vehicle to clarify their intentions and whether behavioral change occurred over time.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative study design was selected to explore how current and future hospitalist leaders planned to modify their behaviors after participating in a hospitalist leadership training course. Participants were encouraged to complete a behavioral contract highlighting their personal goals.

Approximately 12 months later, follow‐up data were collected. Participants were sent copies of their behavioral contracts and surveyed about the extent to which they have realized their personal goals.

Subjects

Hospitalist leaders participating in the 4‐day level I or II leadership courses of the SHM Leadership Academy were studied.

Data Collection

In the final sessions of the 2007‐2008 Leadership Academy courses, participants completed an optional behavioral contract exercise in which they partnered with a colleague and were asked to identify 4 action plans they intended to implement upon their return home. These were written down and signed. Selected demographic information was also collected.

Follow‐up surveys were sent by mail and electronically to a subset of participants with completed behavioral contracts. A 5‐point Likert scale (strongly agree . . . strongly disagree) was used to assess the extent of adherence to the goals listed in the behavioral contracts.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using an editing organizing style, a qualitative analysis technique to find meaningful units or segments of text that both stand on their own and relate to the purpose of the study.12 With this method, the coding template emerges from the data. Two investigators independently analyzed the transcripts and created a coding template based on common themes identified among the participants. In cases of discrepant coding, the 2 investigators had discussions to reach consensus. The authors agreed on representative quotes for each theme. Triangulation was established through sharing results of the analysis with a subset of participants.

Follow‐up survey data was summarized descriptively showing proportion data.

Results

Response Rate and Participant Demographics

Out of 264 people who completed the course, 120 decided to participate in the optional behavioral contract exercise. The median age of participants was 38 years (Table 1). The majority were male (84; 70.0%), and hospitalist leaders (76; 63.3%). The median time in practice as a hospitalist was 4 years. Fewer than one‐half held an academic appointment (40; 33.3%) with most being at the rank of Assistant Professor (14; 11.7%). Most of the participants worked in a private hospital (80; 66.7%).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age in years [median (SD)] | 38 (8) |

| Male [n (%)] | 84 (70.0) |

| Years in practice as hospitalist [median (SD)] | 4 (13) |

| Leader of hospitalist program [n (%)] | 76 (63.3) |

| Academic affiliation [n (%)] | 40 (33.3) |

| Academic rank [n (%)] | |

| Instructor | 9 (7.5) |

| Assistant professor | 14 (11.7) |

| Associate professor | 13 (10.8) |

| Hospital type [n (%)] | |

| Private | 80 (66.7) |

| University | 15 (12.5) |

| Government | 2 (1.7) |

| Veterans administration | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) |

Results of Qualitative Analysis of Behavioral Contracts

From the analyses of the behavioral contracts, themes emerged related to ways in which participants hoped to develop and improve. The themes and the frequencies with which they were recorded in the behavioral contracts are shown in Table 2.

| Theme | Total Number of Times Theme Mentioned in All Behavioral Contracts | Number of Respondents Referring to Theme [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Improving communication and interpersonal skills | 132 | 70 (58.3) |

| Refinement of vision, goals, and strategic planning | 115 | 62 (51.7) |

| Improve intrapersonal development | 65 | 36 (30.0) |

| Enhance negotiation skills | 65 | 44 (36.7) |

| Commit to organizational change | 53 | 32 (26.7) |

| Understanding business drivers | 38 | 28 (23.3) |

| Setting performance and clinical metrics | 34 | 26 (21.7) |

| Strengthen interdepartmental relations | 32 | 26 (21.7) |

Improving Communication and Interpersonal Skills

A desire to improve communication and listening skills, particularly in the context of conflict resolution, was mentioned repeatedly. Heightened awareness about different personality types to allow for improved interpersonal relationships was another concept that was emphasized.

One female Instructor from an academic medical center described her intentions:

I will try to do a better job at assessing the behavioral tendencies of my partners and adjust my own style for more effective communication.

Refinement of Vision, Goals, and Strategic Planning

Physicians were committed to returning to their home institutions and embarking on initiatives to advance vision and goals of their groups within the context of strategic planning. Participants were interested in creating hospitalist‐specific mission statements, developing specific goals that take advantage of strengths and opportunities while minimizing internal weaknesses and considering external threats. They described wanting to align the interests of members of their hospitalist groups around a common goal.

A female hospitalist leader in private practice wished to:

Clearly define a group vision and commit to re‐evaluation on a regular basis to ensure we are on track . . . and conduct a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis to set future goals.

Improve Intrapersonal Development

Participants expressed desire to improve their leadership skills. Proposed goals included: (1) recognizing their weaknesses and soliciting feedback from colleagues, (2) minimizing emotional response to stress, (3) sharing their knowledge and skills for the benefit of peers, (4) delegating work more effectively to others, (5) reading suggested books on leadership, (6) serving as a positive role model and mentor, and (7) managing meetings and difficult coworkers more skillfully.

One female Assistant Professor from an academic medical center outlined:

I want to be able to: (1) manage up better and effectively negotiate with the administration on behalf of my group; (2) become better at leadership skills by using the tools offered at the Academy; and (3) effectively support my group members to develop their skills to become successful in their chosen niches. I will . . . improve the poor morale in my group.

Enhance Negotiation Skills

Many physician leaders identified negotiation principles and techniques as foundations for improvement for interactions within their own groups, as well as with the hospital administration.

A male private hospitalist leader working for 4 years as a hospitalist described plans to utilize negotiation skills within and outside the group:

Negotiate with my team of hospitalists to make them more compliant with the rules and regulations of the group, and negotiate an excellent contract with hospital administration. . . .

Commit to Organizational Change

The hospitalist respondents described their ability to influence organizational change given their unique position at the interface between patient care delivery and hospital administration. To realize organizational change, commonly cited ideas included recruitment and retention of clinically excellent practitioners, and developing standard protocols to facilitate quality improvement initiatives.

A male Instructor of Medicine listed select areas in which to become more involved:

Participation with the Chief Executive Officer of the company in quality improvement projects, calls to the primary care practitioners upon discharge, and the handoff process.

Other Themes

The final 3 themes included are: understanding business drivers; the establishment of better metrics to assess performance; and the strengthening of interdepartmental relations.

Follow‐up Data About Adherence to Plans Delineated in Behavioral Contracts

Out of 65 completed behavioral contracts from the 2007 Level I participants, 32 returned a follow‐up survey (response rate 49.3%). Figure 1 shows the extent to which respondents believed that they were compliant with their proposed plans for change or improvement. Degree of adherence was displayed as a proportion of total goals. Out of those who returned a follow‐up survey, all but 1 respondent either strongly agreed or agreed that they adhered to at least one of their goals (96.9%).

Select representative comments that illustrate the physicians' appreciation of using behavioral contracts include:

my approach to problems is a bit more analytical.

simple changes in how I approach people and interact with them has greatly improved my skills as a leader and allowed me to accomplish my goals with much less effort.

Discussion

Through the qualitative analysis of the behavioral contracts completed by participants of a Leadership Academy for hospitalists, we characterized the ways that hospitalist practitioners hoped to evolve as leaders. The major themes that emerged relate not only to their own growth and development but also their pledge to advance the success of the group or division. The level of commitment and impact of the behavioral contracts appear to be reinforced by an overwhelmingly positive response to adherence to personal goals one year after course participation. Communication and interpersonal development were most frequently cited in the behavioral contracts as areas for which the hospitalist leaders acknowledged a desire to grow. In a study of academic department of medicine chairs, communication skills were identified as being vital for effective leadership.3 The Chairs also recognized other proficiencies required for leading that were consistent with those outlined in the behavioral contracts: strategic planning, change management, team building, personnel management, and systems thinking. McDade et al.17 examined the effects of participation in an executive leadership program developed for female academic faculty in medical and dental schools in the United States and Canada. They noted increased self‐assessed leadership capabilities at 18 months after attending the program, across 10 leadership constructs taught in the classes. These leadership constructs resonate with the themes found in the plans for change described by our informants.

Hospitalists are assuming leadership roles in an increasing number and with greater scope; however, until now their perspectives on what skill sets are required to be successful have not been well documented. Significant time, effort, and money are invested into the development of hospitalists as leaders.4 The behavioral contract appears to be a tool acceptable to hospitalist physicians; perhaps it can be used as part annual reviews with hospitalists aspiring to be leaders.

Several limitations of the study shall be considered. First, not all participants attending the Leadership Academy opted to fill out the behavioral contracts. Second, this qualitative study is limited to those practitioners who are genuinely interested in growing as leaders as evidenced by their willingness to invest in going to the course. Third, follow‐up surveys relied on self‐assessment and it is not known whether actual realization of these goals occurred or the extent to which behavioral contracts were responsible. Further, follow‐up data were only completed by 49% percent of those targeted. However, hospitalists may be fairly resistant to being surveyed as evidenced by the fact that SHM's 2005‐2006 membership survey yielded a response rate of only 26%.18 Finally, many of the thematic goals were described by fewer than 50% of informants. However, it is important to note that the elements included on each person's behavioral contract emerged spontaneously. If subjects were specifically asked about each theme, the number of comments related to each would certainly be much higher. Qualitative analysis does not really allow us to know whether one theme is more important than another merely because it was mentioned more frequently.

Hospitalist leaders appear to be committed to professional growth and they have reported realization of goals delineated in their behavioral contracts. While varied methods are being used as part of physician leadership training programs, behavioral contracts may enhance promise for change.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Regina Hess for assistance in data preparation and Laurence Wellikson, MD, FHM, Russell Holman, MD and Erica Pearson (all from the SHM) for data collection.

Physicians assume myriad leadership roles within medical institutions. Clinically‐oriented leadership roles can range from managing a small group of providers, to leading entire health systems, to heading up national quality improvement initiatives. While often competent in the practice of medicine, many physicians have not pursued structured management or administrative training. In a survey of Medicine Department Chairs at academic medical centers, none had advanced management degrees despite spending an average of 55% of their time on administrative duties. It is not uncommon for physicians to attend leadership development programs or management seminars, as evidenced by the increasing demand for education.1 Various methods for skill enhancement have been described24; however, the most effective approaches have yet to be determined.

Miller and Dollard5 and Bandura6, 7 have explained that behavioral contracts have evolved from social cognitive theory principles. These contracts are formal written agreements, often negotiated between 2 individuals, to facilitate behavior change. Typically, they involve a clear definition of expected behaviors with specific consequences (usually positive reinforcement).810 Their use in modifying physician behavior, particularly those related to leadership, has not been studied.

Hospitalist physicians represent the fastest growing specialty in the United States.11, 12 Among other responsibilities, they have taken on roles as leaders in hospital administration, education, quality improvement, and public health.1315 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the largest US organization committed to the practice of hospital medicine,16 has established Leadership Academies to prepare hospitalists for these duties. The goal of this study was to assess how hospitalist physicians' commitment to grow as leaders was expressed using behavioral contacts as a vehicle to clarify their intentions and whether behavioral change occurred over time.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative study design was selected to explore how current and future hospitalist leaders planned to modify their behaviors after participating in a hospitalist leadership training course. Participants were encouraged to complete a behavioral contract highlighting their personal goals.

Approximately 12 months later, follow‐up data were collected. Participants were sent copies of their behavioral contracts and surveyed about the extent to which they have realized their personal goals.

Subjects

Hospitalist leaders participating in the 4‐day level I or II leadership courses of the SHM Leadership Academy were studied.

Data Collection

In the final sessions of the 2007‐2008 Leadership Academy courses, participants completed an optional behavioral contract exercise in which they partnered with a colleague and were asked to identify 4 action plans they intended to implement upon their return home. These were written down and signed. Selected demographic information was also collected.

Follow‐up surveys were sent by mail and electronically to a subset of participants with completed behavioral contracts. A 5‐point Likert scale (strongly agree . . . strongly disagree) was used to assess the extent of adherence to the goals listed in the behavioral contracts.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using an editing organizing style, a qualitative analysis technique to find meaningful units or segments of text that both stand on their own and relate to the purpose of the study.12 With this method, the coding template emerges from the data. Two investigators independently analyzed the transcripts and created a coding template based on common themes identified among the participants. In cases of discrepant coding, the 2 investigators had discussions to reach consensus. The authors agreed on representative quotes for each theme. Triangulation was established through sharing results of the analysis with a subset of participants.

Follow‐up survey data was summarized descriptively showing proportion data.

Results

Response Rate and Participant Demographics

Out of 264 people who completed the course, 120 decided to participate in the optional behavioral contract exercise. The median age of participants was 38 years (Table 1). The majority were male (84; 70.0%), and hospitalist leaders (76; 63.3%). The median time in practice as a hospitalist was 4 years. Fewer than one‐half held an academic appointment (40; 33.3%) with most being at the rank of Assistant Professor (14; 11.7%). Most of the participants worked in a private hospital (80; 66.7%).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age in years [median (SD)] | 38 (8) |

| Male [n (%)] | 84 (70.0) |

| Years in practice as hospitalist [median (SD)] | 4 (13) |

| Leader of hospitalist program [n (%)] | 76 (63.3) |

| Academic affiliation [n (%)] | 40 (33.3) |

| Academic rank [n (%)] | |

| Instructor | 9 (7.5) |

| Assistant professor | 14 (11.7) |

| Associate professor | 13 (10.8) |

| Hospital type [n (%)] | |

| Private | 80 (66.7) |

| University | 15 (12.5) |

| Government | 2 (1.7) |

| Veterans administration | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) |

Results of Qualitative Analysis of Behavioral Contracts

From the analyses of the behavioral contracts, themes emerged related to ways in which participants hoped to develop and improve. The themes and the frequencies with which they were recorded in the behavioral contracts are shown in Table 2.

| Theme | Total Number of Times Theme Mentioned in All Behavioral Contracts | Number of Respondents Referring to Theme [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Improving communication and interpersonal skills | 132 | 70 (58.3) |

| Refinement of vision, goals, and strategic planning | 115 | 62 (51.7) |

| Improve intrapersonal development | 65 | 36 (30.0) |

| Enhance negotiation skills | 65 | 44 (36.7) |

| Commit to organizational change | 53 | 32 (26.7) |

| Understanding business drivers | 38 | 28 (23.3) |

| Setting performance and clinical metrics | 34 | 26 (21.7) |

| Strengthen interdepartmental relations | 32 | 26 (21.7) |

Improving Communication and Interpersonal Skills

A desire to improve communication and listening skills, particularly in the context of conflict resolution, was mentioned repeatedly. Heightened awareness about different personality types to allow for improved interpersonal relationships was another concept that was emphasized.

One female Instructor from an academic medical center described her intentions:

I will try to do a better job at assessing the behavioral tendencies of my partners and adjust my own style for more effective communication.

Refinement of Vision, Goals, and Strategic Planning

Physicians were committed to returning to their home institutions and embarking on initiatives to advance vision and goals of their groups within the context of strategic planning. Participants were interested in creating hospitalist‐specific mission statements, developing specific goals that take advantage of strengths and opportunities while minimizing internal weaknesses and considering external threats. They described wanting to align the interests of members of their hospitalist groups around a common goal.

A female hospitalist leader in private practice wished to:

Clearly define a group vision and commit to re‐evaluation on a regular basis to ensure we are on track . . . and conduct a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, Threats) analysis to set future goals.

Improve Intrapersonal Development

Participants expressed desire to improve their leadership skills. Proposed goals included: (1) recognizing their weaknesses and soliciting feedback from colleagues, (2) minimizing emotional response to stress, (3) sharing their knowledge and skills for the benefit of peers, (4) delegating work more effectively to others, (5) reading suggested books on leadership, (6) serving as a positive role model and mentor, and (7) managing meetings and difficult coworkers more skillfully.

One female Assistant Professor from an academic medical center outlined:

I want to be able to: (1) manage up better and effectively negotiate with the administration on behalf of my group; (2) become better at leadership skills by using the tools offered at the Academy; and (3) effectively support my group members to develop their skills to become successful in their chosen niches. I will . . . improve the poor morale in my group.

Enhance Negotiation Skills

Many physician leaders identified negotiation principles and techniques as foundations for improvement for interactions within their own groups, as well as with the hospital administration.

A male private hospitalist leader working for 4 years as a hospitalist described plans to utilize negotiation skills within and outside the group:

Negotiate with my team of hospitalists to make them more compliant with the rules and regulations of the group, and negotiate an excellent contract with hospital administration. . . .

Commit to Organizational Change

The hospitalist respondents described their ability to influence organizational change given their unique position at the interface between patient care delivery and hospital administration. To realize organizational change, commonly cited ideas included recruitment and retention of clinically excellent practitioners, and developing standard protocols to facilitate quality improvement initiatives.

A male Instructor of Medicine listed select areas in which to become more involved:

Participation with the Chief Executive Officer of the company in quality improvement projects, calls to the primary care practitioners upon discharge, and the handoff process.

Other Themes

The final 3 themes included are: understanding business drivers; the establishment of better metrics to assess performance; and the strengthening of interdepartmental relations.

Follow‐up Data About Adherence to Plans Delineated in Behavioral Contracts

Out of 65 completed behavioral contracts from the 2007 Level I participants, 32 returned a follow‐up survey (response rate 49.3%). Figure 1 shows the extent to which respondents believed that they were compliant with their proposed plans for change or improvement. Degree of adherence was displayed as a proportion of total goals. Out of those who returned a follow‐up survey, all but 1 respondent either strongly agreed or agreed that they adhered to at least one of their goals (96.9%).

Select representative comments that illustrate the physicians' appreciation of using behavioral contracts include:

my approach to problems is a bit more analytical.

simple changes in how I approach people and interact with them has greatly improved my skills as a leader and allowed me to accomplish my goals with much less effort.

Discussion

Through the qualitative analysis of the behavioral contracts completed by participants of a Leadership Academy for hospitalists, we characterized the ways that hospitalist practitioners hoped to evolve as leaders. The major themes that emerged relate not only to their own growth and development but also their pledge to advance the success of the group or division. The level of commitment and impact of the behavioral contracts appear to be reinforced by an overwhelmingly positive response to adherence to personal goals one year after course participation. Communication and interpersonal development were most frequently cited in the behavioral contracts as areas for which the hospitalist leaders acknowledged a desire to grow. In a study of academic department of medicine chairs, communication skills were identified as being vital for effective leadership.3 The Chairs also recognized other proficiencies required for leading that were consistent with those outlined in the behavioral contracts: strategic planning, change management, team building, personnel management, and systems thinking. McDade et al.17 examined the effects of participation in an executive leadership program developed for female academic faculty in medical and dental schools in the United States and Canada. They noted increased self‐assessed leadership capabilities at 18 months after attending the program, across 10 leadership constructs taught in the classes. These leadership constructs resonate with the themes found in the plans for change described by our informants.

Hospitalists are assuming leadership roles in an increasing number and with greater scope; however, until now their perspectives on what skill sets are required to be successful have not been well documented. Significant time, effort, and money are invested into the development of hospitalists as leaders.4 The behavioral contract appears to be a tool acceptable to hospitalist physicians; perhaps it can be used as part annual reviews with hospitalists aspiring to be leaders.

Several limitations of the study shall be considered. First, not all participants attending the Leadership Academy opted to fill out the behavioral contracts. Second, this qualitative study is limited to those practitioners who are genuinely interested in growing as leaders as evidenced by their willingness to invest in going to the course. Third, follow‐up surveys relied on self‐assessment and it is not known whether actual realization of these goals occurred or the extent to which behavioral contracts were responsible. Further, follow‐up data were only completed by 49% percent of those targeted. However, hospitalists may be fairly resistant to being surveyed as evidenced by the fact that SHM's 2005‐2006 membership survey yielded a response rate of only 26%.18 Finally, many of the thematic goals were described by fewer than 50% of informants. However, it is important to note that the elements included on each person's behavioral contract emerged spontaneously. If subjects were specifically asked about each theme, the number of comments related to each would certainly be much higher. Qualitative analysis does not really allow us to know whether one theme is more important than another merely because it was mentioned more frequently.

Hospitalist leaders appear to be committed to professional growth and they have reported realization of goals delineated in their behavioral contracts. While varied methods are being used as part of physician leadership training programs, behavioral contracts may enhance promise for change.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Regina Hess for assistance in data preparation and Laurence Wellikson, MD, FHM, Russell Holman, MD and Erica Pearson (all from the SHM) for data collection.

Copyright © 2010 Society of Hospital Medicine