User login

Checklist of Safe Discharge Practices

The transition from hospital to home can expose patients to adverse events during the postdischarge period.[1, 2] Deficits in communication at hospital discharge are common,[3] and accurate information on important hospital events is often inadequately transmitted to outpatient providers, which may adversely affect patient outcomes.[4, 5, 6] Discharge bundles (multifaceted interventions including patient education, structured discharge planning, medication reconciliation, and follow‐up visits or phone calls) are strategies that provide support to patients returning home and facilitate transfer of information to primary‐care providers (PCPs).[7, 8, 9] These interventions collectively may improve patient satisfaction and possibly reduce rehospitalization.[10]

Beginning in 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will be reducing payments to facilities with high rates of readmissions.[11] Thus, improving care transitions and thereby reducing avoidable readmissions are now priorities in many jurisdictions in the United States. There is a similar focus on readmission rates in the province of Ontario.[12] The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care convened an expert advisory panel with a mandate to provide guidance on evidence‐based practices that ensure efficient, effective, safe, and patient‐centered care transitions.[13] The objective of this study is to describe a structured panel approach to safe discharge practices, including a checklist of a recommended sequence of steps that can be followed throughout the hospital stay. This tool can aid efforts to optimize patient discharge from the hospital and improve outcomes.

METHODS

Literature Review

The research team reviewed the literature to determine the nature and format of the core information to be contained in a discharge checklist for hospitalized patients. We searched Medline (through January 2011) for relevant articles. We used combined Medical Subject Headings and keywords using patient discharge, transition, and medication reconciliation. Bibliographies of all relevant articles were reviewed to identify additional studies. In addition, we conducted a focused study of select resources, such as the systematic review examining interventions to reduce rehospitalization by Hansen and colleagues,[10] the Transitional Care Initiative for heart failure patients,[14] the Care Transitions Intervention,[15] Project RED (Re‐Engineered Hospital Discharge),[7] Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions),[16] and The King's Fund report on avoiding hospital admissions.[17] Available toolkit resources including those developed by the Commonwealth Fund in partnership with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,[18] the World Health Organization,[19] and the Safer Healthcare Now![20] were examined in detail.

Consultation With Experts

The panel was composed of expert members from multiple disciplines and across several healthcare sectors, including PCPs, hospitalists, rehabilitation clinicians, nurses, researchers, pharmacists, academics, and hospital administrators. The aim was to create a discharge checklist to aid in transition planning based on best practices.

Checklist‐Development Process

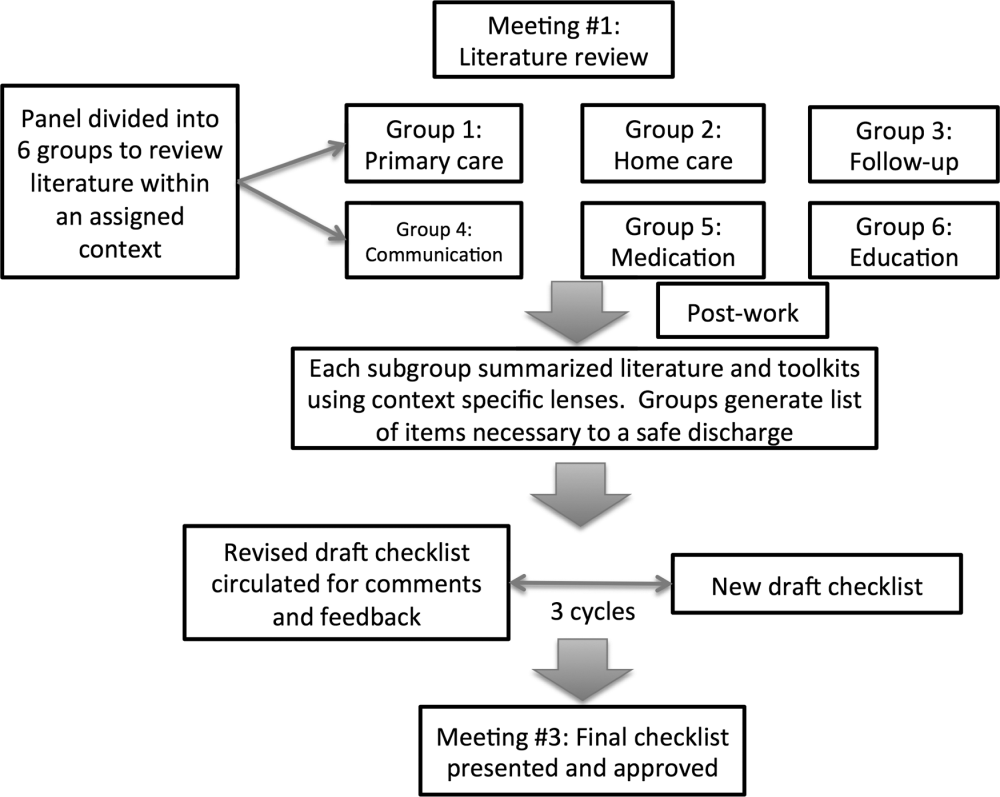

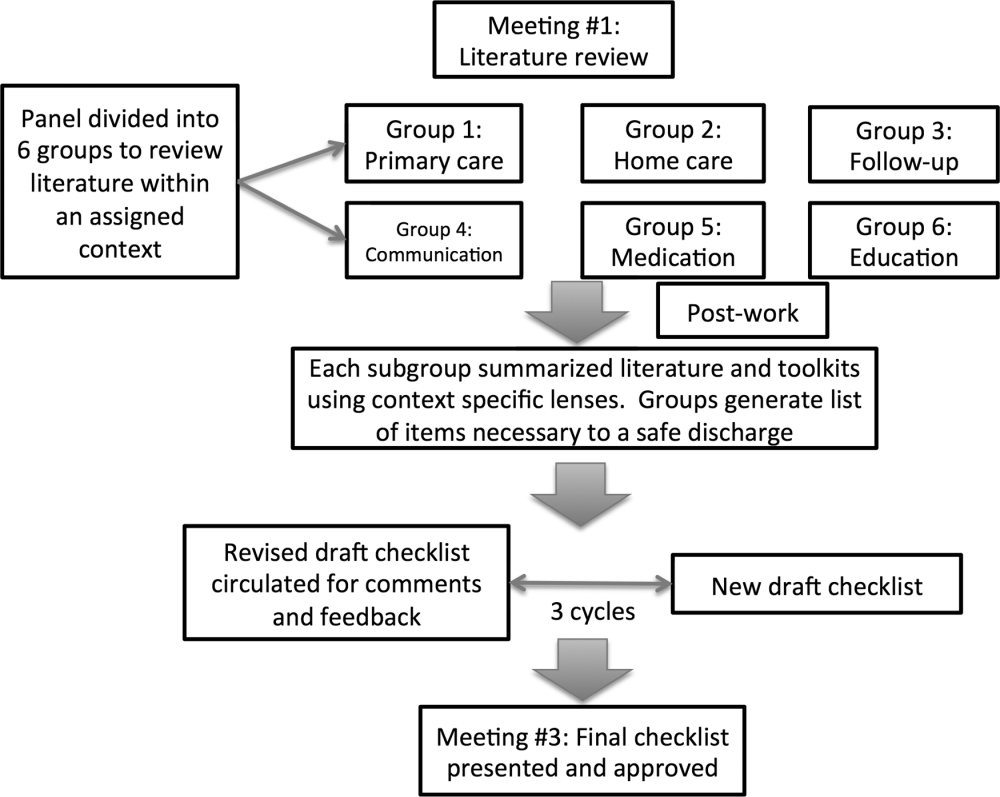

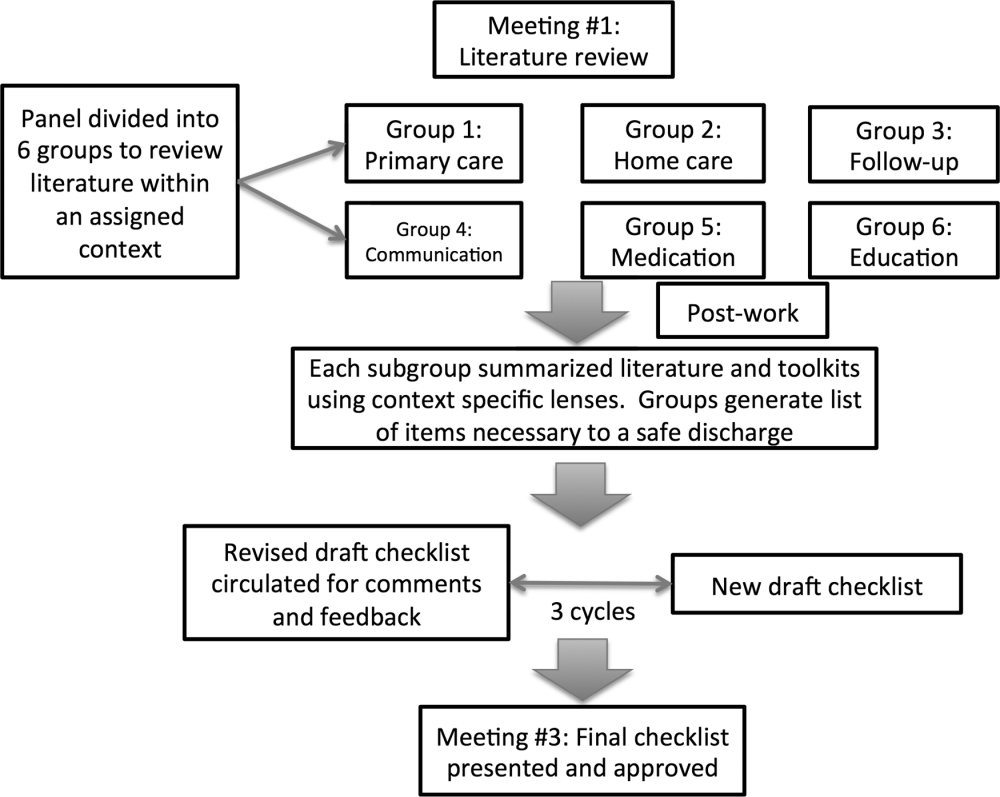

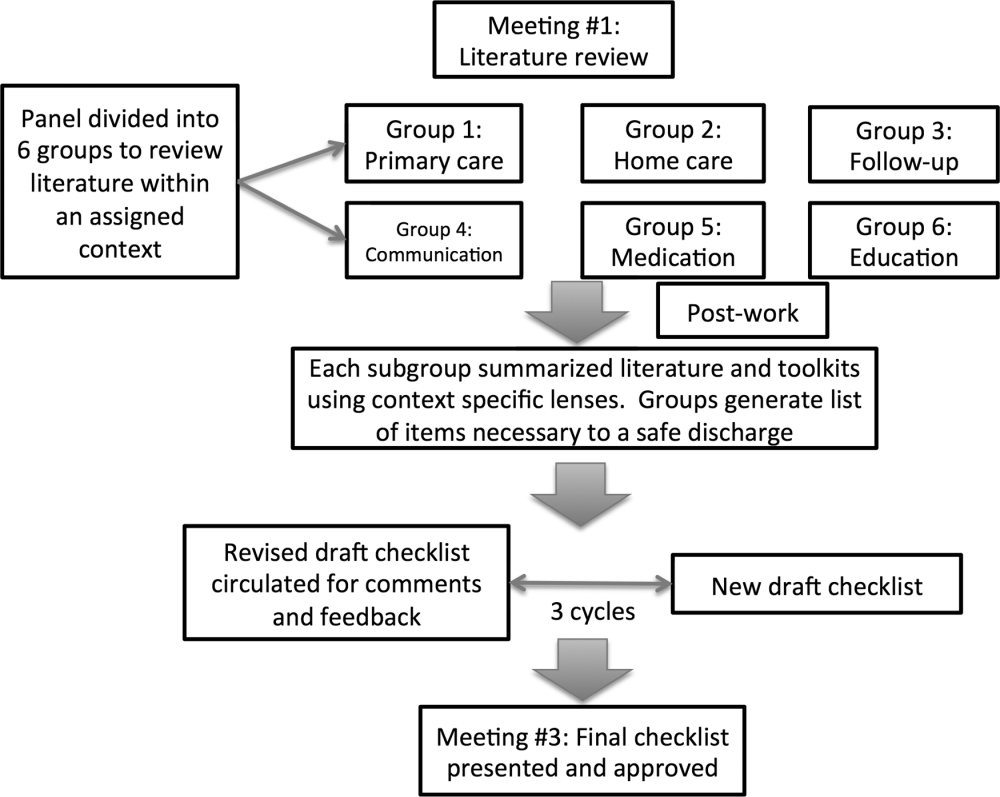

An improvement consultant (N.Z.) facilitated the process (Figure 1). The results of the literature review were circulated prior to the first meeting. The panel met 3 times in person over a period of 3 months, from January 2011 to March 2011. At the first meeting, the panel reviewed existing toolkits and evidence‐based recommendations around best discharge practices. During the meeting, panel members were assigned to 1 of 6 groups (based on specialty area) and instructed to review toolkits and literature using a context‐specific lens (primary care, home care, follow‐up plans, communication to providers and caregivers, medication, and education). The goal of this exercise was to ensure that elements necessary for a successful discharge were viewed through the perspectives of interprofessional groups involved in the care of a patient. For example, PCPs in group 1 were asked to consider an ideal discharge from the perspective of primary care. Following the meeting, each group communicated via e‐mail to generate a list of evidence‐based items necessary for a safe discharge within the context of the group's assigned lens. Every group reached consensus on items specific to its context. A preliminary draft checklist was produced based on input from all groups. The checklist was created using recommended human‐factors engineering concepts.[21] The second meeting provided the opportunity for individual comments and feedback on the draft checklist. Three cycles of checklist revision followed by comments and feedback were conducted after the meeting, through e‐mail exchange. A final meeting provided consensus of the panel on every element of the Safe Discharge Practices Checklist.

RESULTS

Evidence‐based interventions pre‐, post‐, and bridging discharge were categorized into 7 domains: (1) indication for hospitalization, (2) primary care, (3) medication safety, (4) follow‐up plans, (5) home‐care referral, (6) communication with outpatient providers, and (7) patient education (Table 1). The panel reached 100% agreement on the recommended timeline to implement elements of the discharge checklist. Given the diverse interprofessional membership of the panel, it was felt that a daily reminder of tasks to be performed would provide the best format and have the highest likelihood of engaging team members in patient care coordination. It was also felt that daily interdisciplinary (ie, bullet) rounds would serve as the most appropriate venue to utilize the checklist tool.

| Day of Admission | Subsequent Hospital Days | Discharge Day | Discharge Day +3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| 1. Hospital | ||||

| a. Assess patient to see if hospitalization is still required. | ||||

| 2. Primary care | ||||

| a. Identify and/or confirm patient has an active PCP; alert care team if no PCP and/or begin PCP search. | ||||

| b. Contact PCP and notify of patient's admission, diagnosis, and predicted discharge date. | ||||

| c. Book postdischarge PCP follow‐up appointment within 714 days of discharge (according to patient/caregiver availability and transportation needs). | ||||

| 3. Medication safety | ||||

| a. Develop BPMH and reconcile this to admission's medication orders. | ||||

| b. Teach patient how to properly use discharge medications and how these relate to the medications patient was taking prior to admission. | ||||

| c. Reconcile discharge medication order/prescription with BPMH and medications prescribed while in hospital. | ||||

| 4. Follow‐up | ||||

| a.Perform postdischarge follow‐up phone call to patient (for patients with high LACE scoresa). During call, ask: | ||||

| Has patient received new meds (if any)? | ||||

| Has patient received home care? | ||||

| Remind patient of upcoming appointments. | ||||

| If necessary, schedule patient and caregiver to come back to facility for education and training. | ||||

| b. If necessary, arrange outpatient investigations (laboratory, radiology, etc.). | ||||

| c. If necessary, book specialty‐clinic follow‐up appointment. | ||||

| 5. Home care | ||||

| a. Home‐care agency shares information, where available, about patient's existing community services. | ||||

| b. Engage home‐care agencies (eg, interdisciplinary rounds). | ||||

| c. If necessary, schedule postdischarge care. | ||||

| 6. Communication | ||||

| a. Provide patient, community pharmacy, PCP, and formal caregiver (family, LTC, home‐care agency) with copy of Discharge Summary Plan/Note and the Medication Reconciliation Form, and contact information of attending hospital physician and inpatient unit. | ||||

| 7. Patient education | ||||

| a. Clinical team performs teach‐back to patient.b | ||||

| b. Explain to patient how new medications relate to diagnosis. | ||||

| c. Thoroughly explain discharge summary to patient (use teach‐back if needed). | ||||

| d. Explain potential symptoms, what to expect while at home, and under what circumstances patient should visit ED. | ||||

The panel chose daily reminders to perform patient education around medications and clinical care for several reasons. Daily teaching provides an opportunity to assess information carried over and accurate understanding of treatment plans, as well as to review changes in care plans that may be evolving during a hospitalization. Although education starting on day 1 of admission may seem premature, we felt there was merit in addressing issues early. For example, patients admitted with heart failure can benefit from daily inpatient education around self‐monitoring, diet, and lifestyle counseling.[22]

The literature review identified communication with PCPs as an important focus to prevent adverse events when patients transition from hospital to home.[3] The expert panel agreed on admission notification, follow‐up appointment scheduling, and transfer of a high‐quality discharge summary to the patient's PCP, such as one described by Maslove and colleagues.[23] For example, summaries containing structured sections such as relevant inpatient provider contacts, diagnoses, course in hospital, results of investigations (including pending results), discharge instructions and follow‐up, and medication reconciliation have been recommended to improve communication to outpatient providers.[3] Use of validated scores such as the LACE index (a score calculated based on 4 factors: [L] length of hospital stay, [A] acuity on admission, [C] comorbidity, and [E] emergency department visits) to identify patients at high risk of readmission and targeting these individuals when arranging postdischarge follow‐up is encouraged.[24, 25] Patients with high LACE scores (10) would benefit from postdischarge follow‐up phone calls within the first 3 days of returning home. In addition, high‐risk patients may require an earlier follow‐up appointment with the PCP, and the panel supports attempts to arrange follow‐up within 7 days for at‐risk individuals. For those without a PCP, it was recommended that a search should be initiated to assist the patient in obtaining a PCP.

Medication safety is a significant source of adverse events for patients returning home from the hospital.[2, 26, 27, 28] The discharge checklist provides prompts to reconcile medications on admission and discharge, in addition to daily patient education on proper use of medications. Formal medication reconciliation programs should be tailored to the individual hospital's own resources and requirements.[29, 30]

Postdischarge care plays an important role in supporting the patient upon discharge and when part of a multifaceted discharge plan can result in decreased readmission rates and hospital utilization.[7, 9, 15, 31] The panel incorporated these elements by recommending performing postdischarge phone calls, arranging outpatient follow‐up if necessary, and coordinating home‐care services through local agencies.

To facilitate transfer of information, patients, caregivers, outpatient providers, and community pharmacies are to be provided copies of a comprehensive discharge summary, medication reconciliation, and contact information of the inpatient team under the category of Communication. Finally, as the teach‐back method is an effective tool to ensure patient understanding of their health issues, the panel recommended its use when educating patients on medication use, plan of care, and discharge instructions.[32, 33] Examples of scenarios where teach‐back would be of benefit include changes in medications with a high risk of adverse events, such as warfarin or furosemide, to ensure patients understand the dosing, frequency, and monitoring required; and self‐management skills (eg, daily weights and dietary changes) in patients with heart failure.

Finally, the panel noted that it was important to link the checklist items with relevant measures, audit, and feedback to determine associations between process and outcomes. The group avoided specific detailed recommendations to allow each institution to locally tailor appropriate process and outcome measures to assess fidelity of each component of the checklist.

DISCUSSION

A standardized, evidence‐based discharge process is critical to safe transitions for the hospitalized patient. We have used a consensus process of stakeholders to develop a Checklist of Safe Discharge Practices for Hospital Patients that details the steps of events that need to be completed for every day of a typical hospitalization. The day of discharge is often a confusing and chaotic time, with patients receiving an overwhelming volume of information on their last day in the hospital. We believe that discharge planning starts from the day of admission with daily patient education and a coordinated interdisciplinary team approach. The components of the discharge checklist should be completed throughout a patient's hospitalization to ensure a successful discharge and transmission of knowledge.

Discharge checklists have been described previously. Halasyamani and colleagues developed a checklist for elderly inpatients created through a process of literature and peer review followed by a panel discussion at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting.[34] The resultant tool described important data elements necessary for a successful discharge and which processes were most appropriate to facilitate the transfer of information. This differs significantly from our discharge checklist, which provides specific recommendations on methods and processes to effect a safe discharge in addition to an expected timeline of when to complete each step. Kripalani et al reviewed the literature for suggested methods of promoting effective transitions of care at discharge, and their results are consistent with those summarized in our discharge checklist.[29] In contrast to both efforts, our group was multidisciplinary and had broad representation from the acute care, chronic care, home care, rehabilitation medicine, and long‐term care sectors, thereby incorporating all possible aspects of the transition process. Coordinating discharge care requires significant teamwork; our tool extends beyond a checklist of tasks to be performed, and rather serves as a platform to facilitate interprofessional collaboration. In addition, this checklist was designed to integrate discharge planning into interprofessional care rounds occurring throughout a hospital admission. As well, our paper follows an explicit and defined consensus process. Finally, our proposed tool better follows a recommended checklist format.[21]

The discharge process occurring during a patient's hospitalization is a complex, multifaceted care‐coordination plan that must begin on the first day of admission. Often, transfer of important information and medication review take place only hours before a patient leaves the hospital, a suboptimal time for patient education.[28, 35] Just as standardized treatment protocols and care plans can improve outcomes,[36] a similar approach for discharge processes may facilitate safe transition from hospital to home. Our discharge checklist prompts hospital providers to initiate steps necessary for a successful discharge while allowing for local adaptation in how each element is performed. We suggest using the checklist during daily interprofessional team rounds to ensure each task is completed, if appropriate. Institutions may consider measuring process measures such as adherence and completion of checklist, audits of discharge summaries for completion and transmission rates to PCPs (by fax or through health record departments), and documentation of patient education or medication reconciliation. Example outcome measures, if feasible, include Care Transitions Measure (CTM) scores, patient satisfaction surveys, and readmission rates.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, current literature on safe discharge practices is limited by low study‐design quality, with a paucity of randomized controlled trials. However, a recent systematic review found that bundled discharge interventions are likely to be most effective.[10] Individual items of the checklist may not have had an extensive evidence base; however, some of these suggested elements (eg, contact home care) have clinical face validity. Second, the heterogeneity of interventions studied pose challenges in determining generalizable best practices without considering local factors. To mitigate this, we suggest adapting the checklist to local contexts and resource availability. Third, the checklist has not been tested. The next step of this project is to pilot checklist use through small‐scale Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act (PDSA) cycles followed by large‐scale implementation. We plan to collect baseline, process, and outcome measures before and after implementation of the checklist at multiple institutions to determine utility.

Standardization of discharge practices is critical to safe transitions and preventing avoidable admissions to hospital. Our discharge checklist is an expanded tool that provides explicit guidance for each day of hospitalization and can be adapted for any hospital admission to aid interdisciplinary efforts toward a successful discharge. Future studies to evaluate the checklist in improving care‐transition processes are required to determine association with outcomes.

Disclosures

Nothing to report.

- , , , , . The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–128.

- , , , , , . Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , , , . “I wish I had seen this test result earlier!”: dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2223–2228.

- , . Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(7):533–536.

- , , , . Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624–631.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187.

- , , , et al. A Quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 57(9):1540–1546.

- , , , et al. Reduction of 30‐day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high‐risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):211–218.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. Available at: http://cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare‐Fee‐for‐Service‐Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions‐Reduction‐Program.html.Accessed September 5, 2012.

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care. The Excellent Care for All Act, 2010. Available at: http://health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ecfa/default.aspx/. Accessed February 28, 2013.

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care; Baker GR, ed. Enhancing the Continuum of Care: Report of the Avoidable Hospitalization Advisory Panel, November 2011. Available at: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/baker_2011/baker_2011.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- , , , , , . Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1228]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675–684.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Project BOOST: Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/BOOST/. Accessed October 31, 2012.

- The King's Fund; , , . Avoiding Hospital Admissions: Lessons From Evidence and Experience. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/avoiding‐hospital‐admissions‐lessons‐evidence. Published October 28, 2010. Accessed September 4, 2012.

- Nielsen GA, Rutherford P, Taylor J, eds. How‐To Guide: Creating an Ideal Transition Home. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at: http://www.ihi.org or http://ah.cms‐plus.com/files/IHI_How_to_Guide_Creating_an_Ideal_Transition_Home.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- World Health Organization. Action on Patient Safety—High 5s. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/en/index.html. Accessed October 29, 2012.

- Safer Healthcare Now! Medication Reconciliation in Acute Care: Getting Started Kit. Available at: http://www.ismp‐canada.org/download/MedRec/Medrec_AC_English_GSK_V3.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2012.

- US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PSNet: Patient‐safety primers, checklists. Available at: http://www.psnet.ahrq.gov/primer.aspx?primerID=14. Accessed November 1, 2012.

- , , , . Benefits of comprehensive inpatient education and discharge planning combined with outpatient support in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2005;11(6):315–321.

- , , , et al. Electronic versus dictated hospital discharge summaries: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):995–1001.

- , , , et al. Unplanned readmissions after hospital discharge among patients identified as being at high risk for readmission using a validated predictive algorithm. Open Med. 2011;5(2):e104–e111.

- , , , et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–557.

- . Will, ideas, and execution: their role in reducing adverse medication events. J Pediatr. 2005;147(6):727–728.

- , , , . Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2014–2018.

- , , , et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):565–571.

- , , , . Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314–323.

- , . Medication reconciliation in the hospital. Healthc Q. 2012;15:42–49.

- , , , , , . Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):999–1006.

- , , , et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90.

- , , . The effects of patient communication skills training on compliance. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(1):57–64.

- , , , et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354–360.

- , , , , . Influence of a “discharge interview” on patient knowledge, compliance, and functional status after hospitalization. Med Care. 1983;21(8):755–767.

- , , , , . Critical pathways intervention to reduce length of hospital stay. Am J Med. 2001;110(3):175–180.

The transition from hospital to home can expose patients to adverse events during the postdischarge period.[1, 2] Deficits in communication at hospital discharge are common,[3] and accurate information on important hospital events is often inadequately transmitted to outpatient providers, which may adversely affect patient outcomes.[4, 5, 6] Discharge bundles (multifaceted interventions including patient education, structured discharge planning, medication reconciliation, and follow‐up visits or phone calls) are strategies that provide support to patients returning home and facilitate transfer of information to primary‐care providers (PCPs).[7, 8, 9] These interventions collectively may improve patient satisfaction and possibly reduce rehospitalization.[10]

Beginning in 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will be reducing payments to facilities with high rates of readmissions.[11] Thus, improving care transitions and thereby reducing avoidable readmissions are now priorities in many jurisdictions in the United States. There is a similar focus on readmission rates in the province of Ontario.[12] The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care convened an expert advisory panel with a mandate to provide guidance on evidence‐based practices that ensure efficient, effective, safe, and patient‐centered care transitions.[13] The objective of this study is to describe a structured panel approach to safe discharge practices, including a checklist of a recommended sequence of steps that can be followed throughout the hospital stay. This tool can aid efforts to optimize patient discharge from the hospital and improve outcomes.

METHODS

Literature Review

The research team reviewed the literature to determine the nature and format of the core information to be contained in a discharge checklist for hospitalized patients. We searched Medline (through January 2011) for relevant articles. We used combined Medical Subject Headings and keywords using patient discharge, transition, and medication reconciliation. Bibliographies of all relevant articles were reviewed to identify additional studies. In addition, we conducted a focused study of select resources, such as the systematic review examining interventions to reduce rehospitalization by Hansen and colleagues,[10] the Transitional Care Initiative for heart failure patients,[14] the Care Transitions Intervention,[15] Project RED (Re‐Engineered Hospital Discharge),[7] Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions),[16] and The King's Fund report on avoiding hospital admissions.[17] Available toolkit resources including those developed by the Commonwealth Fund in partnership with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,[18] the World Health Organization,[19] and the Safer Healthcare Now![20] were examined in detail.

Consultation With Experts

The panel was composed of expert members from multiple disciplines and across several healthcare sectors, including PCPs, hospitalists, rehabilitation clinicians, nurses, researchers, pharmacists, academics, and hospital administrators. The aim was to create a discharge checklist to aid in transition planning based on best practices.

Checklist‐Development Process

An improvement consultant (N.Z.) facilitated the process (Figure 1). The results of the literature review were circulated prior to the first meeting. The panel met 3 times in person over a period of 3 months, from January 2011 to March 2011. At the first meeting, the panel reviewed existing toolkits and evidence‐based recommendations around best discharge practices. During the meeting, panel members were assigned to 1 of 6 groups (based on specialty area) and instructed to review toolkits and literature using a context‐specific lens (primary care, home care, follow‐up plans, communication to providers and caregivers, medication, and education). The goal of this exercise was to ensure that elements necessary for a successful discharge were viewed through the perspectives of interprofessional groups involved in the care of a patient. For example, PCPs in group 1 were asked to consider an ideal discharge from the perspective of primary care. Following the meeting, each group communicated via e‐mail to generate a list of evidence‐based items necessary for a safe discharge within the context of the group's assigned lens. Every group reached consensus on items specific to its context. A preliminary draft checklist was produced based on input from all groups. The checklist was created using recommended human‐factors engineering concepts.[21] The second meeting provided the opportunity for individual comments and feedback on the draft checklist. Three cycles of checklist revision followed by comments and feedback were conducted after the meeting, through e‐mail exchange. A final meeting provided consensus of the panel on every element of the Safe Discharge Practices Checklist.

RESULTS

Evidence‐based interventions pre‐, post‐, and bridging discharge were categorized into 7 domains: (1) indication for hospitalization, (2) primary care, (3) medication safety, (4) follow‐up plans, (5) home‐care referral, (6) communication with outpatient providers, and (7) patient education (Table 1). The panel reached 100% agreement on the recommended timeline to implement elements of the discharge checklist. Given the diverse interprofessional membership of the panel, it was felt that a daily reminder of tasks to be performed would provide the best format and have the highest likelihood of engaging team members in patient care coordination. It was also felt that daily interdisciplinary (ie, bullet) rounds would serve as the most appropriate venue to utilize the checklist tool.

| Day of Admission | Subsequent Hospital Days | Discharge Day | Discharge Day +3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| 1. Hospital | ||||

| a. Assess patient to see if hospitalization is still required. | ||||

| 2. Primary care | ||||

| a. Identify and/or confirm patient has an active PCP; alert care team if no PCP and/or begin PCP search. | ||||

| b. Contact PCP and notify of patient's admission, diagnosis, and predicted discharge date. | ||||

| c. Book postdischarge PCP follow‐up appointment within 714 days of discharge (according to patient/caregiver availability and transportation needs). | ||||

| 3. Medication safety | ||||

| a. Develop BPMH and reconcile this to admission's medication orders. | ||||

| b. Teach patient how to properly use discharge medications and how these relate to the medications patient was taking prior to admission. | ||||

| c. Reconcile discharge medication order/prescription with BPMH and medications prescribed while in hospital. | ||||

| 4. Follow‐up | ||||

| a.Perform postdischarge follow‐up phone call to patient (for patients with high LACE scoresa). During call, ask: | ||||

| Has patient received new meds (if any)? | ||||

| Has patient received home care? | ||||

| Remind patient of upcoming appointments. | ||||

| If necessary, schedule patient and caregiver to come back to facility for education and training. | ||||

| b. If necessary, arrange outpatient investigations (laboratory, radiology, etc.). | ||||

| c. If necessary, book specialty‐clinic follow‐up appointment. | ||||

| 5. Home care | ||||

| a. Home‐care agency shares information, where available, about patient's existing community services. | ||||

| b. Engage home‐care agencies (eg, interdisciplinary rounds). | ||||

| c. If necessary, schedule postdischarge care. | ||||

| 6. Communication | ||||

| a. Provide patient, community pharmacy, PCP, and formal caregiver (family, LTC, home‐care agency) with copy of Discharge Summary Plan/Note and the Medication Reconciliation Form, and contact information of attending hospital physician and inpatient unit. | ||||

| 7. Patient education | ||||

| a. Clinical team performs teach‐back to patient.b | ||||

| b. Explain to patient how new medications relate to diagnosis. | ||||

| c. Thoroughly explain discharge summary to patient (use teach‐back if needed). | ||||

| d. Explain potential symptoms, what to expect while at home, and under what circumstances patient should visit ED. | ||||

The panel chose daily reminders to perform patient education around medications and clinical care for several reasons. Daily teaching provides an opportunity to assess information carried over and accurate understanding of treatment plans, as well as to review changes in care plans that may be evolving during a hospitalization. Although education starting on day 1 of admission may seem premature, we felt there was merit in addressing issues early. For example, patients admitted with heart failure can benefit from daily inpatient education around self‐monitoring, diet, and lifestyle counseling.[22]

The literature review identified communication with PCPs as an important focus to prevent adverse events when patients transition from hospital to home.[3] The expert panel agreed on admission notification, follow‐up appointment scheduling, and transfer of a high‐quality discharge summary to the patient's PCP, such as one described by Maslove and colleagues.[23] For example, summaries containing structured sections such as relevant inpatient provider contacts, diagnoses, course in hospital, results of investigations (including pending results), discharge instructions and follow‐up, and medication reconciliation have been recommended to improve communication to outpatient providers.[3] Use of validated scores such as the LACE index (a score calculated based on 4 factors: [L] length of hospital stay, [A] acuity on admission, [C] comorbidity, and [E] emergency department visits) to identify patients at high risk of readmission and targeting these individuals when arranging postdischarge follow‐up is encouraged.[24, 25] Patients with high LACE scores (10) would benefit from postdischarge follow‐up phone calls within the first 3 days of returning home. In addition, high‐risk patients may require an earlier follow‐up appointment with the PCP, and the panel supports attempts to arrange follow‐up within 7 days for at‐risk individuals. For those without a PCP, it was recommended that a search should be initiated to assist the patient in obtaining a PCP.

Medication safety is a significant source of adverse events for patients returning home from the hospital.[2, 26, 27, 28] The discharge checklist provides prompts to reconcile medications on admission and discharge, in addition to daily patient education on proper use of medications. Formal medication reconciliation programs should be tailored to the individual hospital's own resources and requirements.[29, 30]

Postdischarge care plays an important role in supporting the patient upon discharge and when part of a multifaceted discharge plan can result in decreased readmission rates and hospital utilization.[7, 9, 15, 31] The panel incorporated these elements by recommending performing postdischarge phone calls, arranging outpatient follow‐up if necessary, and coordinating home‐care services through local agencies.

To facilitate transfer of information, patients, caregivers, outpatient providers, and community pharmacies are to be provided copies of a comprehensive discharge summary, medication reconciliation, and contact information of the inpatient team under the category of Communication. Finally, as the teach‐back method is an effective tool to ensure patient understanding of their health issues, the panel recommended its use when educating patients on medication use, plan of care, and discharge instructions.[32, 33] Examples of scenarios where teach‐back would be of benefit include changes in medications with a high risk of adverse events, such as warfarin or furosemide, to ensure patients understand the dosing, frequency, and monitoring required; and self‐management skills (eg, daily weights and dietary changes) in patients with heart failure.

Finally, the panel noted that it was important to link the checklist items with relevant measures, audit, and feedback to determine associations between process and outcomes. The group avoided specific detailed recommendations to allow each institution to locally tailor appropriate process and outcome measures to assess fidelity of each component of the checklist.

DISCUSSION

A standardized, evidence‐based discharge process is critical to safe transitions for the hospitalized patient. We have used a consensus process of stakeholders to develop a Checklist of Safe Discharge Practices for Hospital Patients that details the steps of events that need to be completed for every day of a typical hospitalization. The day of discharge is often a confusing and chaotic time, with patients receiving an overwhelming volume of information on their last day in the hospital. We believe that discharge planning starts from the day of admission with daily patient education and a coordinated interdisciplinary team approach. The components of the discharge checklist should be completed throughout a patient's hospitalization to ensure a successful discharge and transmission of knowledge.

Discharge checklists have been described previously. Halasyamani and colleagues developed a checklist for elderly inpatients created through a process of literature and peer review followed by a panel discussion at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting.[34] The resultant tool described important data elements necessary for a successful discharge and which processes were most appropriate to facilitate the transfer of information. This differs significantly from our discharge checklist, which provides specific recommendations on methods and processes to effect a safe discharge in addition to an expected timeline of when to complete each step. Kripalani et al reviewed the literature for suggested methods of promoting effective transitions of care at discharge, and their results are consistent with those summarized in our discharge checklist.[29] In contrast to both efforts, our group was multidisciplinary and had broad representation from the acute care, chronic care, home care, rehabilitation medicine, and long‐term care sectors, thereby incorporating all possible aspects of the transition process. Coordinating discharge care requires significant teamwork; our tool extends beyond a checklist of tasks to be performed, and rather serves as a platform to facilitate interprofessional collaboration. In addition, this checklist was designed to integrate discharge planning into interprofessional care rounds occurring throughout a hospital admission. As well, our paper follows an explicit and defined consensus process. Finally, our proposed tool better follows a recommended checklist format.[21]

The discharge process occurring during a patient's hospitalization is a complex, multifaceted care‐coordination plan that must begin on the first day of admission. Often, transfer of important information and medication review take place only hours before a patient leaves the hospital, a suboptimal time for patient education.[28, 35] Just as standardized treatment protocols and care plans can improve outcomes,[36] a similar approach for discharge processes may facilitate safe transition from hospital to home. Our discharge checklist prompts hospital providers to initiate steps necessary for a successful discharge while allowing for local adaptation in how each element is performed. We suggest using the checklist during daily interprofessional team rounds to ensure each task is completed, if appropriate. Institutions may consider measuring process measures such as adherence and completion of checklist, audits of discharge summaries for completion and transmission rates to PCPs (by fax or through health record departments), and documentation of patient education or medication reconciliation. Example outcome measures, if feasible, include Care Transitions Measure (CTM) scores, patient satisfaction surveys, and readmission rates.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, current literature on safe discharge practices is limited by low study‐design quality, with a paucity of randomized controlled trials. However, a recent systematic review found that bundled discharge interventions are likely to be most effective.[10] Individual items of the checklist may not have had an extensive evidence base; however, some of these suggested elements (eg, contact home care) have clinical face validity. Second, the heterogeneity of interventions studied pose challenges in determining generalizable best practices without considering local factors. To mitigate this, we suggest adapting the checklist to local contexts and resource availability. Third, the checklist has not been tested. The next step of this project is to pilot checklist use through small‐scale Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act (PDSA) cycles followed by large‐scale implementation. We plan to collect baseline, process, and outcome measures before and after implementation of the checklist at multiple institutions to determine utility.

Standardization of discharge practices is critical to safe transitions and preventing avoidable admissions to hospital. Our discharge checklist is an expanded tool that provides explicit guidance for each day of hospitalization and can be adapted for any hospital admission to aid interdisciplinary efforts toward a successful discharge. Future studies to evaluate the checklist in improving care‐transition processes are required to determine association with outcomes.

Disclosures

Nothing to report.

The transition from hospital to home can expose patients to adverse events during the postdischarge period.[1, 2] Deficits in communication at hospital discharge are common,[3] and accurate information on important hospital events is often inadequately transmitted to outpatient providers, which may adversely affect patient outcomes.[4, 5, 6] Discharge bundles (multifaceted interventions including patient education, structured discharge planning, medication reconciliation, and follow‐up visits or phone calls) are strategies that provide support to patients returning home and facilitate transfer of information to primary‐care providers (PCPs).[7, 8, 9] These interventions collectively may improve patient satisfaction and possibly reduce rehospitalization.[10]

Beginning in 2012, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services will be reducing payments to facilities with high rates of readmissions.[11] Thus, improving care transitions and thereby reducing avoidable readmissions are now priorities in many jurisdictions in the United States. There is a similar focus on readmission rates in the province of Ontario.[12] The Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care convened an expert advisory panel with a mandate to provide guidance on evidence‐based practices that ensure efficient, effective, safe, and patient‐centered care transitions.[13] The objective of this study is to describe a structured panel approach to safe discharge practices, including a checklist of a recommended sequence of steps that can be followed throughout the hospital stay. This tool can aid efforts to optimize patient discharge from the hospital and improve outcomes.

METHODS

Literature Review

The research team reviewed the literature to determine the nature and format of the core information to be contained in a discharge checklist for hospitalized patients. We searched Medline (through January 2011) for relevant articles. We used combined Medical Subject Headings and keywords using patient discharge, transition, and medication reconciliation. Bibliographies of all relevant articles were reviewed to identify additional studies. In addition, we conducted a focused study of select resources, such as the systematic review examining interventions to reduce rehospitalization by Hansen and colleagues,[10] the Transitional Care Initiative for heart failure patients,[14] the Care Transitions Intervention,[15] Project RED (Re‐Engineered Hospital Discharge),[7] Project BOOST (Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions),[16] and The King's Fund report on avoiding hospital admissions.[17] Available toolkit resources including those developed by the Commonwealth Fund in partnership with the Institute for Healthcare Improvement,[18] the World Health Organization,[19] and the Safer Healthcare Now![20] were examined in detail.

Consultation With Experts

The panel was composed of expert members from multiple disciplines and across several healthcare sectors, including PCPs, hospitalists, rehabilitation clinicians, nurses, researchers, pharmacists, academics, and hospital administrators. The aim was to create a discharge checklist to aid in transition planning based on best practices.

Checklist‐Development Process

An improvement consultant (N.Z.) facilitated the process (Figure 1). The results of the literature review were circulated prior to the first meeting. The panel met 3 times in person over a period of 3 months, from January 2011 to March 2011. At the first meeting, the panel reviewed existing toolkits and evidence‐based recommendations around best discharge practices. During the meeting, panel members were assigned to 1 of 6 groups (based on specialty area) and instructed to review toolkits and literature using a context‐specific lens (primary care, home care, follow‐up plans, communication to providers and caregivers, medication, and education). The goal of this exercise was to ensure that elements necessary for a successful discharge were viewed through the perspectives of interprofessional groups involved in the care of a patient. For example, PCPs in group 1 were asked to consider an ideal discharge from the perspective of primary care. Following the meeting, each group communicated via e‐mail to generate a list of evidence‐based items necessary for a safe discharge within the context of the group's assigned lens. Every group reached consensus on items specific to its context. A preliminary draft checklist was produced based on input from all groups. The checklist was created using recommended human‐factors engineering concepts.[21] The second meeting provided the opportunity for individual comments and feedback on the draft checklist. Three cycles of checklist revision followed by comments and feedback were conducted after the meeting, through e‐mail exchange. A final meeting provided consensus of the panel on every element of the Safe Discharge Practices Checklist.

RESULTS

Evidence‐based interventions pre‐, post‐, and bridging discharge were categorized into 7 domains: (1) indication for hospitalization, (2) primary care, (3) medication safety, (4) follow‐up plans, (5) home‐care referral, (6) communication with outpatient providers, and (7) patient education (Table 1). The panel reached 100% agreement on the recommended timeline to implement elements of the discharge checklist. Given the diverse interprofessional membership of the panel, it was felt that a daily reminder of tasks to be performed would provide the best format and have the highest likelihood of engaging team members in patient care coordination. It was also felt that daily interdisciplinary (ie, bullet) rounds would serve as the most appropriate venue to utilize the checklist tool.

| Day of Admission | Subsequent Hospital Days | Discharge Day | Discharge Day +3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| 1. Hospital | ||||

| a. Assess patient to see if hospitalization is still required. | ||||

| 2. Primary care | ||||

| a. Identify and/or confirm patient has an active PCP; alert care team if no PCP and/or begin PCP search. | ||||

| b. Contact PCP and notify of patient's admission, diagnosis, and predicted discharge date. | ||||

| c. Book postdischarge PCP follow‐up appointment within 714 days of discharge (according to patient/caregiver availability and transportation needs). | ||||

| 3. Medication safety | ||||

| a. Develop BPMH and reconcile this to admission's medication orders. | ||||

| b. Teach patient how to properly use discharge medications and how these relate to the medications patient was taking prior to admission. | ||||

| c. Reconcile discharge medication order/prescription with BPMH and medications prescribed while in hospital. | ||||

| 4. Follow‐up | ||||

| a.Perform postdischarge follow‐up phone call to patient (for patients with high LACE scoresa). During call, ask: | ||||

| Has patient received new meds (if any)? | ||||

| Has patient received home care? | ||||

| Remind patient of upcoming appointments. | ||||

| If necessary, schedule patient and caregiver to come back to facility for education and training. | ||||

| b. If necessary, arrange outpatient investigations (laboratory, radiology, etc.). | ||||

| c. If necessary, book specialty‐clinic follow‐up appointment. | ||||

| 5. Home care | ||||

| a. Home‐care agency shares information, where available, about patient's existing community services. | ||||

| b. Engage home‐care agencies (eg, interdisciplinary rounds). | ||||

| c. If necessary, schedule postdischarge care. | ||||

| 6. Communication | ||||

| a. Provide patient, community pharmacy, PCP, and formal caregiver (family, LTC, home‐care agency) with copy of Discharge Summary Plan/Note and the Medication Reconciliation Form, and contact information of attending hospital physician and inpatient unit. | ||||

| 7. Patient education | ||||

| a. Clinical team performs teach‐back to patient.b | ||||

| b. Explain to patient how new medications relate to diagnosis. | ||||

| c. Thoroughly explain discharge summary to patient (use teach‐back if needed). | ||||

| d. Explain potential symptoms, what to expect while at home, and under what circumstances patient should visit ED. | ||||

The panel chose daily reminders to perform patient education around medications and clinical care for several reasons. Daily teaching provides an opportunity to assess information carried over and accurate understanding of treatment plans, as well as to review changes in care plans that may be evolving during a hospitalization. Although education starting on day 1 of admission may seem premature, we felt there was merit in addressing issues early. For example, patients admitted with heart failure can benefit from daily inpatient education around self‐monitoring, diet, and lifestyle counseling.[22]

The literature review identified communication with PCPs as an important focus to prevent adverse events when patients transition from hospital to home.[3] The expert panel agreed on admission notification, follow‐up appointment scheduling, and transfer of a high‐quality discharge summary to the patient's PCP, such as one described by Maslove and colleagues.[23] For example, summaries containing structured sections such as relevant inpatient provider contacts, diagnoses, course in hospital, results of investigations (including pending results), discharge instructions and follow‐up, and medication reconciliation have been recommended to improve communication to outpatient providers.[3] Use of validated scores such as the LACE index (a score calculated based on 4 factors: [L] length of hospital stay, [A] acuity on admission, [C] comorbidity, and [E] emergency department visits) to identify patients at high risk of readmission and targeting these individuals when arranging postdischarge follow‐up is encouraged.[24, 25] Patients with high LACE scores (10) would benefit from postdischarge follow‐up phone calls within the first 3 days of returning home. In addition, high‐risk patients may require an earlier follow‐up appointment with the PCP, and the panel supports attempts to arrange follow‐up within 7 days for at‐risk individuals. For those without a PCP, it was recommended that a search should be initiated to assist the patient in obtaining a PCP.

Medication safety is a significant source of adverse events for patients returning home from the hospital.[2, 26, 27, 28] The discharge checklist provides prompts to reconcile medications on admission and discharge, in addition to daily patient education on proper use of medications. Formal medication reconciliation programs should be tailored to the individual hospital's own resources and requirements.[29, 30]

Postdischarge care plays an important role in supporting the patient upon discharge and when part of a multifaceted discharge plan can result in decreased readmission rates and hospital utilization.[7, 9, 15, 31] The panel incorporated these elements by recommending performing postdischarge phone calls, arranging outpatient follow‐up if necessary, and coordinating home‐care services through local agencies.

To facilitate transfer of information, patients, caregivers, outpatient providers, and community pharmacies are to be provided copies of a comprehensive discharge summary, medication reconciliation, and contact information of the inpatient team under the category of Communication. Finally, as the teach‐back method is an effective tool to ensure patient understanding of their health issues, the panel recommended its use when educating patients on medication use, plan of care, and discharge instructions.[32, 33] Examples of scenarios where teach‐back would be of benefit include changes in medications with a high risk of adverse events, such as warfarin or furosemide, to ensure patients understand the dosing, frequency, and monitoring required; and self‐management skills (eg, daily weights and dietary changes) in patients with heart failure.

Finally, the panel noted that it was important to link the checklist items with relevant measures, audit, and feedback to determine associations between process and outcomes. The group avoided specific detailed recommendations to allow each institution to locally tailor appropriate process and outcome measures to assess fidelity of each component of the checklist.

DISCUSSION

A standardized, evidence‐based discharge process is critical to safe transitions for the hospitalized patient. We have used a consensus process of stakeholders to develop a Checklist of Safe Discharge Practices for Hospital Patients that details the steps of events that need to be completed for every day of a typical hospitalization. The day of discharge is often a confusing and chaotic time, with patients receiving an overwhelming volume of information on their last day in the hospital. We believe that discharge planning starts from the day of admission with daily patient education and a coordinated interdisciplinary team approach. The components of the discharge checklist should be completed throughout a patient's hospitalization to ensure a successful discharge and transmission of knowledge.

Discharge checklists have been described previously. Halasyamani and colleagues developed a checklist for elderly inpatients created through a process of literature and peer review followed by a panel discussion at the Society of Hospital Medicine Annual Meeting.[34] The resultant tool described important data elements necessary for a successful discharge and which processes were most appropriate to facilitate the transfer of information. This differs significantly from our discharge checklist, which provides specific recommendations on methods and processes to effect a safe discharge in addition to an expected timeline of when to complete each step. Kripalani et al reviewed the literature for suggested methods of promoting effective transitions of care at discharge, and their results are consistent with those summarized in our discharge checklist.[29] In contrast to both efforts, our group was multidisciplinary and had broad representation from the acute care, chronic care, home care, rehabilitation medicine, and long‐term care sectors, thereby incorporating all possible aspects of the transition process. Coordinating discharge care requires significant teamwork; our tool extends beyond a checklist of tasks to be performed, and rather serves as a platform to facilitate interprofessional collaboration. In addition, this checklist was designed to integrate discharge planning into interprofessional care rounds occurring throughout a hospital admission. As well, our paper follows an explicit and defined consensus process. Finally, our proposed tool better follows a recommended checklist format.[21]

The discharge process occurring during a patient's hospitalization is a complex, multifaceted care‐coordination plan that must begin on the first day of admission. Often, transfer of important information and medication review take place only hours before a patient leaves the hospital, a suboptimal time for patient education.[28, 35] Just as standardized treatment protocols and care plans can improve outcomes,[36] a similar approach for discharge processes may facilitate safe transition from hospital to home. Our discharge checklist prompts hospital providers to initiate steps necessary for a successful discharge while allowing for local adaptation in how each element is performed. We suggest using the checklist during daily interprofessional team rounds to ensure each task is completed, if appropriate. Institutions may consider measuring process measures such as adherence and completion of checklist, audits of discharge summaries for completion and transmission rates to PCPs (by fax or through health record departments), and documentation of patient education or medication reconciliation. Example outcome measures, if feasible, include Care Transitions Measure (CTM) scores, patient satisfaction surveys, and readmission rates.

Several limitations of this study should be considered. First, current literature on safe discharge practices is limited by low study‐design quality, with a paucity of randomized controlled trials. However, a recent systematic review found that bundled discharge interventions are likely to be most effective.[10] Individual items of the checklist may not have had an extensive evidence base; however, some of these suggested elements (eg, contact home care) have clinical face validity. Second, the heterogeneity of interventions studied pose challenges in determining generalizable best practices without considering local factors. To mitigate this, we suggest adapting the checklist to local contexts and resource availability. Third, the checklist has not been tested. The next step of this project is to pilot checklist use through small‐scale Plan‐Do‐Study‐Act (PDSA) cycles followed by large‐scale implementation. We plan to collect baseline, process, and outcome measures before and after implementation of the checklist at multiple institutions to determine utility.

Standardization of discharge practices is critical to safe transitions and preventing avoidable admissions to hospital. Our discharge checklist is an expanded tool that provides explicit guidance for each day of hospitalization and can be adapted for any hospital admission to aid interdisciplinary efforts toward a successful discharge. Future studies to evaluate the checklist in improving care‐transition processes are required to determine association with outcomes.

Disclosures

Nothing to report.

- , , , , . The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–128.

- , , , , , . Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , , , . “I wish I had seen this test result earlier!”: dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2223–2228.

- , . Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(7):533–536.

- , , , . Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624–631.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187.

- , , , et al. A Quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 57(9):1540–1546.

- , , , et al. Reduction of 30‐day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high‐risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):211–218.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. Available at: http://cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare‐Fee‐for‐Service‐Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions‐Reduction‐Program.html.Accessed September 5, 2012.

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care. The Excellent Care for All Act, 2010. Available at: http://health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ecfa/default.aspx/. Accessed February 28, 2013.

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care; Baker GR, ed. Enhancing the Continuum of Care: Report of the Avoidable Hospitalization Advisory Panel, November 2011. Available at: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/baker_2011/baker_2011.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- , , , , , . Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1228]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675–684.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Project BOOST: Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/BOOST/. Accessed October 31, 2012.

- The King's Fund; , , . Avoiding Hospital Admissions: Lessons From Evidence and Experience. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/avoiding‐hospital‐admissions‐lessons‐evidence. Published October 28, 2010. Accessed September 4, 2012.

- Nielsen GA, Rutherford P, Taylor J, eds. How‐To Guide: Creating an Ideal Transition Home. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at: http://www.ihi.org or http://ah.cms‐plus.com/files/IHI_How_to_Guide_Creating_an_Ideal_Transition_Home.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- World Health Organization. Action on Patient Safety—High 5s. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/en/index.html. Accessed October 29, 2012.

- Safer Healthcare Now! Medication Reconciliation in Acute Care: Getting Started Kit. Available at: http://www.ismp‐canada.org/download/MedRec/Medrec_AC_English_GSK_V3.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2012.

- US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PSNet: Patient‐safety primers, checklists. Available at: http://www.psnet.ahrq.gov/primer.aspx?primerID=14. Accessed November 1, 2012.

- , , , . Benefits of comprehensive inpatient education and discharge planning combined with outpatient support in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2005;11(6):315–321.

- , , , et al. Electronic versus dictated hospital discharge summaries: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):995–1001.

- , , , et al. Unplanned readmissions after hospital discharge among patients identified as being at high risk for readmission using a validated predictive algorithm. Open Med. 2011;5(2):e104–e111.

- , , , et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–557.

- . Will, ideas, and execution: their role in reducing adverse medication events. J Pediatr. 2005;147(6):727–728.

- , , , . Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2014–2018.

- , , , et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):565–571.

- , , , . Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314–323.

- , . Medication reconciliation in the hospital. Healthc Q. 2012;15:42–49.

- , , , , , . Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):999–1006.

- , , , et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90.

- , , . The effects of patient communication skills training on compliance. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(1):57–64.

- , , , et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354–360.

- , , , , . Influence of a “discharge interview” on patient knowledge, compliance, and functional status after hospitalization. Med Care. 1983;21(8):755–767.

- , , , , . Critical pathways intervention to reduce length of hospital stay. Am J Med. 2001;110(3):175–180.

- , , , , . The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161–167.

- , , , et al. Patient safety concerns arising from test results that return after hospital discharge. Ann Intern Med. 2005;143(2):121–128.

- , , , , , . Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital‐based and primary care physicians: implications for patient safety and continuity of care. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831–841.

- , , , , , . “I wish I had seen this test result earlier!”: dissatisfaction with test result management systems in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164(20):2223–2228.

- , . Lost in transition: challenges and opportunities for improving the quality of transitional care. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(7):533–536.

- , , , . Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624–631.

- , , , et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178–187.

- , , , et al. A Quality improvement intervention to facilitate the transition of older adults from three hospitals back to their homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 57(9):1540–1546.

- , , , et al. Reduction of 30‐day postdischarge hospital readmission or emergency department (ED) visit rates in high‐risk elderly medical patients through delivery of a targeted care bundle. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(4):211–218.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(8):520–528.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Readmissions reduction program. Available at: http://cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare‐Fee‐for‐Service‐Payment/AcuteInpatientPPS/Readmissions‐Reduction‐Program.html.Accessed September 5, 2012.

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care. The Excellent Care for All Act, 2010. Available at: http://health.gov.on.ca/en/public/programs/ecfa/default.aspx/. Accessed February 28, 2013.

- Ontario Ministry of Health and Long‐Term Care; Baker GR, ed. Enhancing the Continuum of Care: Report of the Avoidable Hospitalization Advisory Panel, November 2011. Available at: http://www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/ministry/publications/reports/baker_2011/baker_2011.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- , , , , , . Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial [published correction appears in J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(7):1228]. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(5):675–684.

- , , , . The care transitions intervention: results of a randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(17):1822–1828.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Project BOOST: Better Outcomes by Optimizing Safe Transitions. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/BOOST/. Accessed October 31, 2012.

- The King's Fund; , , . Avoiding Hospital Admissions: Lessons From Evidence and Experience. Available at: http://www.kingsfund.org.uk/publications/articles/avoiding‐hospital‐admissions‐lessons‐evidence. Published October 28, 2010. Accessed September 4, 2012.

- Nielsen GA, Rutherford P, Taylor J, eds. How‐To Guide: Creating an Ideal Transition Home. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; 2009. Available at: http://www.ihi.org or http://ah.cms‐plus.com/files/IHI_How_to_Guide_Creating_an_Ideal_Transition_Home.pdf. Accessed August 8, 2012.

- World Health Organization. Action on Patient Safety—High 5s. Available at: http://www.who.int/patientsafety/implementation/solutions/high5s/en/index.html. Accessed October 29, 2012.

- Safer Healthcare Now! Medication Reconciliation in Acute Care: Getting Started Kit. Available at: http://www.ismp‐canada.org/download/MedRec/Medrec_AC_English_GSK_V3.pdf. Accessed October 29, 2012.

- US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. PSNet: Patient‐safety primers, checklists. Available at: http://www.psnet.ahrq.gov/primer.aspx?primerID=14. Accessed November 1, 2012.

- , , , . Benefits of comprehensive inpatient education and discharge planning combined with outpatient support in elderly patients with congestive heart failure. Congest Heart Fail. 2005;11(6):315–321.

- , , , et al. Electronic versus dictated hospital discharge summaries: a randomized controlled trial. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(9):995–1001.

- , , , et al. Unplanned readmissions after hospital discharge among patients identified as being at high risk for readmission using a validated predictive algorithm. Open Med. 2011;5(2):e104–e111.

- , , , et al. Derivation and validation of an index to predict early death or unplanned readmission after discharge from hospital to the community. CMAJ. 2010;182(6):551–557.

- . Will, ideas, and execution: their role in reducing adverse medication events. J Pediatr. 2005;147(6):727–728.

- , , , . Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2014–2018.

- , , , et al. Role of pharmacist counseling in preventing adverse drug events after hospitalization. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(5):565–571.

- , , , . Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2007;2(5):314–323.

- , . Medication reconciliation in the hospital. Healthc Q. 2012;15:42–49.

- , , , , , . Comprehensive discharge planning for the hospitalized elderly: a randomized clinical trial. Ann Intern Med. 1994;120(12):999–1006.

- , , , et al. Closing the loop: physician communication with diabetic patients who have low health literacy. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(1):83–90.

- , , . The effects of patient communication skills training on compliance. Arch Fam Med. 2000;9(1):57–64.

- , , , et al. Transition of care for hospitalized elderly patients—development of a discharge checklist for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(6):354–360.

- , , , , . Influence of a “discharge interview” on patient knowledge, compliance, and functional status after hospitalization. Med Care. 1983;21(8):755–767.

- , , , , . Critical pathways intervention to reduce length of hospital stay. Am J Med. 2001;110(3):175–180.

Copyright © 2013 Society of Hospital Medicine

Hospitalist Physician Leadership Skills

Physicians assume myriad leadership roles within medical institutions. Clinically‐oriented leadership roles can range from managing a small group of providers, to leading entire health systems, to heading up national quality improvement initiatives. While often competent in the practice of medicine, many physicians have not pursued structured management or administrative training. In a survey of Medicine Department Chairs at academic medical centers, none had advanced management degrees despite spending an average of 55% of their time on administrative duties. It is not uncommon for physicians to attend leadership development programs or management seminars, as evidenced by the increasing demand for education.1 Various methods for skill enhancement have been described24; however, the most effective approaches have yet to be determined.

Miller and Dollard5 and Bandura6, 7 have explained that behavioral contracts have evolved from social cognitive theory principles. These contracts are formal written agreements, often negotiated between 2 individuals, to facilitate behavior change. Typically, they involve a clear definition of expected behaviors with specific consequences (usually positive reinforcement).810 Their use in modifying physician behavior, particularly those related to leadership, has not been studied.

Hospitalist physicians represent the fastest growing specialty in the United States.11, 12 Among other responsibilities, they have taken on roles as leaders in hospital administration, education, quality improvement, and public health.1315 The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM), the largest US organization committed to the practice of hospital medicine,16 has established Leadership Academies to prepare hospitalists for these duties. The goal of this study was to assess how hospitalist physicians' commitment to grow as leaders was expressed using behavioral contacts as a vehicle to clarify their intentions and whether behavioral change occurred over time.

Methods

Study Design

A qualitative study design was selected to explore how current and future hospitalist leaders planned to modify their behaviors after participating in a hospitalist leadership training course. Participants were encouraged to complete a behavioral contract highlighting their personal goals.

Approximately 12 months later, follow‐up data were collected. Participants were sent copies of their behavioral contracts and surveyed about the extent to which they have realized their personal goals.

Subjects

Hospitalist leaders participating in the 4‐day level I or II leadership courses of the SHM Leadership Academy were studied.

Data Collection

In the final sessions of the 2007‐2008 Leadership Academy courses, participants completed an optional behavioral contract exercise in which they partnered with a colleague and were asked to identify 4 action plans they intended to implement upon their return home. These were written down and signed. Selected demographic information was also collected.

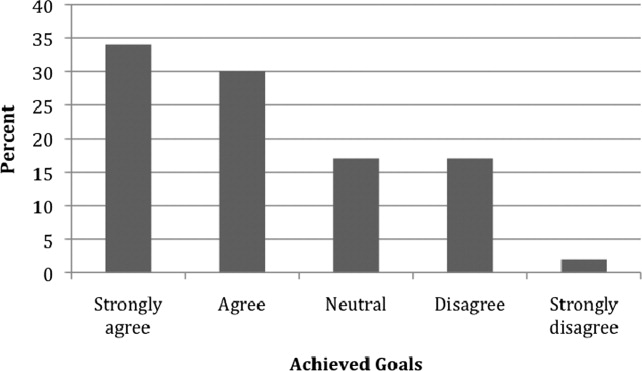

Follow‐up surveys were sent by mail and electronically to a subset of participants with completed behavioral contracts. A 5‐point Likert scale (strongly agree . . . strongly disagree) was used to assess the extent of adherence to the goals listed in the behavioral contracts.

Data Analysis

Transcripts were analyzed using an editing organizing style, a qualitative analysis technique to find meaningful units or segments of text that both stand on their own and relate to the purpose of the study.12 With this method, the coding template emerges from the data. Two investigators independently analyzed the transcripts and created a coding template based on common themes identified among the participants. In cases of discrepant coding, the 2 investigators had discussions to reach consensus. The authors agreed on representative quotes for each theme. Triangulation was established through sharing results of the analysis with a subset of participants.

Follow‐up survey data was summarized descriptively showing proportion data.

Results

Response Rate and Participant Demographics

Out of 264 people who completed the course, 120 decided to participate in the optional behavioral contract exercise. The median age of participants was 38 years (Table 1). The majority were male (84; 70.0%), and hospitalist leaders (76; 63.3%). The median time in practice as a hospitalist was 4 years. Fewer than one‐half held an academic appointment (40; 33.3%) with most being at the rank of Assistant Professor (14; 11.7%). Most of the participants worked in a private hospital (80; 66.7%).

| Characteristic | |

|---|---|

| |

| Age in years [median (SD)] | 38 (8) |

| Male [n (%)] | 84 (70.0) |

| Years in practice as hospitalist [median (SD)] | 4 (13) |

| Leader of hospitalist program [n (%)] | 76 (63.3) |

| Academic affiliation [n (%)] | 40 (33.3) |

| Academic rank [n (%)] | |

| Instructor | 9 (7.5) |

| Assistant professor | 14 (11.7) |

| Associate professor | 13 (10.8) |

| Hospital type [n (%)] | |

| Private | 80 (66.7) |

| University | 15 (12.5) |

| Government | 2 (1.7) |

| Veterans administration | 0 (0.0) |

| Other | 1 (0.1) |

Results of Qualitative Analysis of Behavioral Contracts

From the analyses of the behavioral contracts, themes emerged related to ways in which participants hoped to develop and improve. The themes and the frequencies with which they were recorded in the behavioral contracts are shown in Table 2.

| Theme | Total Number of Times Theme Mentioned in All Behavioral Contracts | Number of Respondents Referring to Theme [n (%)] |

|---|---|---|

| ||

| Improving communication and interpersonal skills | 132 | 70 (58.3) |

| Refinement of vision, goals, and strategic planning | 115 | 62 (51.7) |

| Improve intrapersonal development | 65 | 36 (30.0) |

| Enhance negotiation skills | 65 | 44 (36.7) |

| Commit to organizational change | 53 | 32 (26.7) |

| Understanding business drivers | 38 | 28 (23.3) |

| Setting performance and clinical metrics | 34 | 26 (21.7) |

| Strengthen interdepartmental relations | 32 | 26 (21.7) |

Improving Communication and Interpersonal Skills

A desire to improve communication and listening skills, particularly in the context of conflict resolution, was mentioned repeatedly. Heightened awareness about different personality types to allow for improved interpersonal relationships was another concept that was emphasized.

One female Instructor from an academic medical center described her intentions:

I will try to do a better job at assessing the behavioral tendencies of my partners and adjust my own style for more effective communication.

Refinement of Vision, Goals, and Strategic Planning