User login

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

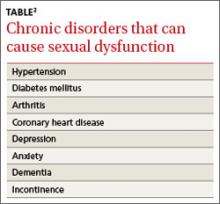

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; [email protected]

1. Balami JS. Are geriatricians guilty of failure to take a sexual history? J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;2:17-20.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.

3. Bradford A, Meston CM. Senior sexual health: The effects of aging on sexuality. In: VandeCreek L, Petersen FL, Bley JW, eds. Innovations in Clinical Practice: Focus on Sexual Health. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2007:35-45.

4. Graber C. Sex keeps elderly happier in marriage. Scientific American.

Available at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/sex-keeps-elderly-happier-in-marria-11-11-29. Accessed March 26, 2014.

5. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

6. Tobin JM, Harindra V. Attendance by older patients at a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:289-291.

7. Bauer M, McAuliffe L, Nay R. Sexuality, health care and the older person: an overview of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs. 2007;2:63-68.

8. Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, et al. The health of aging lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in California. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2011;(PB2011-2):1-8.

9. Henry J, McNab W. Forever young: a health promotion focus on sexuality and aging. Gerontol Geriatr Education. 2003;23:57-74.

10. Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2093-2103.

11. Nusbaum MR, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1705-1712.

12. Burd ID, Nevadunsky N, Bachmann G. Impact of physician gender on sexual history taking in a multispecialty practice. J Sex Med. 2006;3:194-200.

13. Kazer MW. Sexuality Assessment for Older Adults. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing Web site. Available at: http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_10.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed March 14, 2014.

14. Wallace MA. Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nursing. 2012;108:52-60.

15. Sexuality in later life. National Institute on Aging Web site. Available at: http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexualitylater-life. Updated March 11, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2014.

16. Hajjar RR, Kamel HK. Sexuality in the nursing home, part 1: attitudes and barriers to sexual expression. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(2 suppl):S42-S47.

17. Bildtgård T. The sexuality of elderly people on film—visual limitations. J Aging Identity. 2000;5:169-183.

18. Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6-16.

19. Gott M, Hinchliff S. Barriers to seeking treatment for sexual problems in primary care: a qualitative study with older people. Fam Pract. 2003;20:690-695.

20. Politi MC, Clark MA, Armstrong G, et al. Patient-provider communication about sexual health among unmarried middle-aged and older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:511-516.

21. Bouman W, Arcelus J, Benbow S. Nottingham study of sexuality & ageing (NoSSA I). Attitudes regarding sexuality and older people: a review of the literature. Sex Relationship Ther. 2006;21:149-161.

22. Low LPL, Lui MHL, Lee DTF, et al. Promoting awareness of sexuality of older people in residential care. Electronic J Human Sexuality. 2005;8:8-16.

23. Rheaume C, Mitty E. Sexuality and intimacy in older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29:342-349.

24. Nagaratnam N, Gayagay G Jr. Hypersexuality in nursing care facilities—a descriptive study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35:195-203.

25. HIV among older Americans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/age/olderamericans/. Updated December 23, 2013. Accessed February 28, 2014.

26. Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:453-472.

27. Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; [email protected]

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; [email protected]

1. Balami JS. Are geriatricians guilty of failure to take a sexual history? J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;2:17-20.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.

3. Bradford A, Meston CM. Senior sexual health: The effects of aging on sexuality. In: VandeCreek L, Petersen FL, Bley JW, eds. Innovations in Clinical Practice: Focus on Sexual Health. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2007:35-45.

4. Graber C. Sex keeps elderly happier in marriage. Scientific American.

Available at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/sex-keeps-elderly-happier-in-marria-11-11-29. Accessed March 26, 2014.

5. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

6. Tobin JM, Harindra V. Attendance by older patients at a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:289-291.

7. Bauer M, McAuliffe L, Nay R. Sexuality, health care and the older person: an overview of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs. 2007;2:63-68.

8. Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, et al. The health of aging lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in California. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2011;(PB2011-2):1-8.

9. Henry J, McNab W. Forever young: a health promotion focus on sexuality and aging. Gerontol Geriatr Education. 2003;23:57-74.

10. Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2093-2103.

11. Nusbaum MR, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1705-1712.

12. Burd ID, Nevadunsky N, Bachmann G. Impact of physician gender on sexual history taking in a multispecialty practice. J Sex Med. 2006;3:194-200.

13. Kazer MW. Sexuality Assessment for Older Adults. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing Web site. Available at: http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_10.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed March 14, 2014.

14. Wallace MA. Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nursing. 2012;108:52-60.

15. Sexuality in later life. National Institute on Aging Web site. Available at: http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexualitylater-life. Updated March 11, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2014.

16. Hajjar RR, Kamel HK. Sexuality in the nursing home, part 1: attitudes and barriers to sexual expression. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(2 suppl):S42-S47.

17. Bildtgård T. The sexuality of elderly people on film—visual limitations. J Aging Identity. 2000;5:169-183.

18. Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6-16.

19. Gott M, Hinchliff S. Barriers to seeking treatment for sexual problems in primary care: a qualitative study with older people. Fam Pract. 2003;20:690-695.

20. Politi MC, Clark MA, Armstrong G, et al. Patient-provider communication about sexual health among unmarried middle-aged and older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:511-516.

21. Bouman W, Arcelus J, Benbow S. Nottingham study of sexuality & ageing (NoSSA I). Attitudes regarding sexuality and older people: a review of the literature. Sex Relationship Ther. 2006;21:149-161.

22. Low LPL, Lui MHL, Lee DTF, et al. Promoting awareness of sexuality of older people in residential care. Electronic J Human Sexuality. 2005;8:8-16.

23. Rheaume C, Mitty E. Sexuality and intimacy in older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29:342-349.

24. Nagaratnam N, Gayagay G Jr. Hypersexuality in nursing care facilities—a descriptive study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35:195-203.

25. HIV among older Americans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/age/olderamericans/. Updated December 23, 2013. Accessed February 28, 2014.

26. Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:453-472.

27. Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.

1. Balami JS. Are geriatricians guilty of failure to take a sexual history? J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;2:17-20.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.

3. Bradford A, Meston CM. Senior sexual health: The effects of aging on sexuality. In: VandeCreek L, Petersen FL, Bley JW, eds. Innovations in Clinical Practice: Focus on Sexual Health. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2007:35-45.

4. Graber C. Sex keeps elderly happier in marriage. Scientific American.

Available at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/sex-keeps-elderly-happier-in-marria-11-11-29. Accessed March 26, 2014.

5. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

6. Tobin JM, Harindra V. Attendance by older patients at a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:289-291.

7. Bauer M, McAuliffe L, Nay R. Sexuality, health care and the older person: an overview of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs. 2007;2:63-68.

8. Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, et al. The health of aging lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in California. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2011;(PB2011-2):1-8.

9. Henry J, McNab W. Forever young: a health promotion focus on sexuality and aging. Gerontol Geriatr Education. 2003;23:57-74.

10. Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2093-2103.

11. Nusbaum MR, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1705-1712.

12. Burd ID, Nevadunsky N, Bachmann G. Impact of physician gender on sexual history taking in a multispecialty practice. J Sex Med. 2006;3:194-200.

13. Kazer MW. Sexuality Assessment for Older Adults. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing Web site. Available at: http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_10.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed March 14, 2014.

14. Wallace MA. Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nursing. 2012;108:52-60.

15. Sexuality in later life. National Institute on Aging Web site. Available at: http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexualitylater-life. Updated March 11, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2014.

16. Hajjar RR, Kamel HK. Sexuality in the nursing home, part 1: attitudes and barriers to sexual expression. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(2 suppl):S42-S47.

17. Bildtgård T. The sexuality of elderly people on film—visual limitations. J Aging Identity. 2000;5:169-183.

18. Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6-16.

19. Gott M, Hinchliff S. Barriers to seeking treatment for sexual problems in primary care: a qualitative study with older people. Fam Pract. 2003;20:690-695.

20. Politi MC, Clark MA, Armstrong G, et al. Patient-provider communication about sexual health among unmarried middle-aged and older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:511-516.

21. Bouman W, Arcelus J, Benbow S. Nottingham study of sexuality & ageing (NoSSA I). Attitudes regarding sexuality and older people: a review of the literature. Sex Relationship Ther. 2006;21:149-161.

22. Low LPL, Lui MHL, Lee DTF, et al. Promoting awareness of sexuality of older people in residential care. Electronic J Human Sexuality. 2005;8:8-16.

23. Rheaume C, Mitty E. Sexuality and intimacy in older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29:342-349.

24. Nagaratnam N, Gayagay G Jr. Hypersexuality in nursing care facilities—a descriptive study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35:195-203.

25. HIV among older Americans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/age/olderamericans/. Updated December 23, 2013. Accessed February 28, 2014.

26. Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:453-472.

27. Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.