User login

Establishing a Genetic Cancer Risk Assessment Clinic

Genetic cancers are relatively uncommon but not rare. Although there has not been a comprehensive study of the incidence of cancers that are caused by an identifiable single gene mutation, it is estimated that they account for approximately 5% to 10% of all cancers, or 50,000 to 100,000 patients annually in the U.S.1 The hallmarks of a genetic cancer syndrome are early onset, multiple family members in multiple generations with cancer, bilateral cancer, and multiple cancers in the same person.

Until recently, the VA has not had a significant interest in genetic cancer risk assessment (GCRA). This is changing, however, because veterans with identified genetic risks for cancer can benefit from targeted screening and intervention strategies to lower their risk of dying of cancer. The value of GCRA was also recognized in the 2015 standards for accreditation of the American College of Surgeons, which include a requirement for programs to include a provision for GCRA.2

The 2 most common familial cancer syndromes are hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome, which occurs in about 5% of all patients with breast cancer, and Lynch syndrome (LS), or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (CRC) syndrome, which occurs in about 3% of all patients with CRC.3,4 Other familial cancer syndromes are rare: For example, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) accounts for 0.2% to 0.5% of all CRC cases.5

The Raymond G. Murphy VAMC in Albuquerque is the sole VA hospital in New Mexico. Its catchment area extends into southern Colorado, eastern Arizona, and western Texas. About 40 CRCs and 8 breast cancers are diagnosed at this facility yearly. Given the incidence of these familial cancer syndromes, one might expect to see 1 LS case/year, 1 HBOC case every 2 years, and 1 FAP or attenuated FAP case every 5 to 10 years.

Methods

In 2010, a GCRA clinic was set up to evaluate and manage treatment of veterans who might have inherited a genetic cancer syndrome. Prior to that, veterans with suspected genetic cancer family syndromes were referred to the University of New Mexico for evaluation and testing. Initially, the pathology department (PD) paid for genetic testing. However, due to the cost of testing, a formal budget for genetic testing was approved. Contracts were set up by the PD with outside laboratories for genetic testing services. For quality control, all veterans who were referred for genetic evaluation were seen by Dr. Lin.

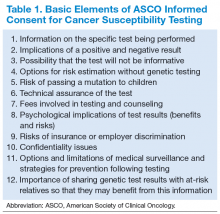

The initial consultation consisted of construction of a family pedigree and evaluation, using available models or tables, such as the Myriad tables (BRCA), Penn II BRCA, or PREMM1,2,6 (LS), to estimate likelihood of finding a mutation. Veterans who had a 10% likelihood of finding a gene mutation were counseled, following the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines (Table 1). Those who consented to genetic testing signed a consent form and were given a copy of that form and a copy of their family pedigree. Because the VA covers the cost of counseling and testing, cost was not discussed.

Veterans had a follow-up visit to review the test results. Patients were counseled on treatment recommendations, including a copy of current consensus recommendations, and disclosure to the family. The recommendations were then included in the patient’s electronic medical record. For example, BRCA patients had a discussion of risks and benefits of various management options, including breast magnetic resonance imaging, prophylactic mastectomy, and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, once childbearing was complete.

Results

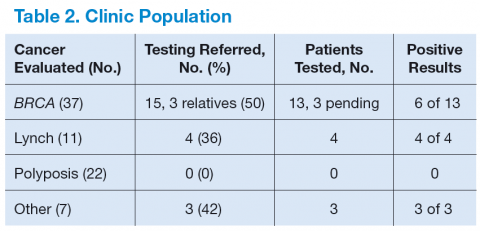

Table 2 shows the number of veterans referred to the GCRA clinic since it started in late 2010, categorized by the likely genetic syndrome, the number and percentage of veterans where genetic testing was recommended, and the results of testing. Four veterans, 2 with LS, 1 with CHEK2 mutation, and 1 with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, were identified outside the VA system but were referred for counseling. One of the veterans with LS was referred by an outside provider who obtained a suspicious family history, and the other was identified via pathologic screening. The miscellaneous group included 1 veteran with MEN 1 and 1 veteran with Birt-Hogg-Dube.

There are a number of interesting results. Although the number of patients referred for LS was low, the number of annual referrals for possible BRCA was about equal to the number of patients with breast cancer who were diagnosed and treated yearly. Although this could have been due to pent up demand initially, the number of annual referrals has not decreased with time. Furthermore, the number of patients referred for polyposis has been considerably higher than would be expected by the rarity of attenuated FAP. Initially, patients with 10 to 20 polyps of any type were referred for evaluation. All but 1 had their first polyp diagnosed after the age of 50 years. Five veterans who were referred to GCRA had < 10 polyps lifetime, 3 veterans had between 10 and 20 polyps, and 12 veterans have had ≥ 20 adenomatous polyps over their lifetime. None seen to date have had a personal or family history of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer.

Discussion

A genetic cancer risk assessment clinic was set up in a VA hospital and has been running successfully for 4 years. Although many parts of setting up such a clinic are common to a community GCRA clinic, there are also aspects that are specific to a VA setting.6

Because genetic testing is relatively expensive, a budget must be set up and approved by VA administration. This budget is based on the estimated number of veterans that will be referred yearly, the likely percentage that will need to be tested, and the cost of testing. Currently, the average cost of a single gene test is about $2,000 to $3,000. Some patients will need to have 2 to 4 genes tested. Furthermore, many centers are now moving to multigene testing, and the cost of these panels is about $10,000 or more, though this is less than the cumulative cost of the genes done individually.

Since there is currently no national VA contract for genetic cancer testing, each VA facility needs to negotiate contracts with outside laboratories. Several of these laboratories offer gene panel testing, but the panels vary from one laboratory to another.

Limiting the number of providers who can order genetic testing helps maintain quality control and ensure a comprehensive database of patient testing. At the Albuquerque VAMC, Dr. Lin is currently the only provider who can order genetic testing for cancer risk assessment. Nearly all GCRA consultations, from obtaining a detailed family history to providing education on the risks, benefits, and limitations of genetic testing, can be conducted via telemedicine. The VA GCRA program in Utah has established a number of telemedicine collaborations with VA facilities around the country, beginning with BRCA consultations and branching out into a national LS screening program.

The first few years of the program have shown some unexpected results, including a much higher referral rate for HBOC referrals than was anticipated. The reasons for this are not clear. The high rate of polyposis referrals can be attributed in large part to the robust CRC screening program in the VA system. Veterans are routinely screened for CRC with occult blood tests, and positive results are referred for colonoscopy. Nearly 400 veterans per year have a colonoscopy at the Albuquerque VAMC.

Because the VA screening program begins at age 50 years, nearly all the veterans referred to date have had their first polyp diagnosed at age ≥ 50 years. Unfortunately, the 1 patient who had polyps and CRC at a young age was not tested due to lack of budget when she was evaluated. By contrast, in a large study, the median age of first polyp diagnosis in patients with APC mutation was 30 years, and with biallelic MUTYH mutations was 47 years.7

The difficulty in distinguishing which veterans should be tested for attenuated FAP lies in the fact that age of onset and personal or family history alone or in

combination do not seem to be adequate discriminators to screen out low-risk veterans who do not need testing.7 Considering the number of veterans referred each year and the incidence of attenuated FAP, if every veteran who fit the current criteria of 20 adenomatous polyps lifetime were tested, about 35 to 70 veterans would have to be tested to detect 1 mutation carrier. The development of clinical criteria to identify low-risk patients would be very helpful.

On the other hand, referrals for LS were uncommon. This is consistent with results reported elsewhere.8 For this reason, diagnosis of LS has shifted from clinical identification to pathologic screening for the molecular hallmarks of LS in tumor specimens.8,9 Shortly after the GCRA clinic was established, a pathologist with an interest in GI malignancies developed and validated a pathologic screening program using immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for mismatch repair (MMR) gene expression, with the assistance of a pathologist who had been involved in a community-based LS screening program.9 For the past 3 years, all CRC patients aged ≤ 60 years have been screened for loss of expression of MMR IHC. Patients identified have been seen in the GCRA clinic to discuss possible genetic testing. This screening program is now extending to all patients with CRC aged ≤ 70 years, in line with consensus recommendations.10

The Future

The lack of a national VA contract with outside laboratories for genetic testing means that each facility has to negotiate its own contract, which is a wasteful duplication of resources that needs to be addressed. Beyond this parochial concern, GCRA is undergoing a revolution in diagnosing and managing cancer risk. In the past, a careful family history was followed by selected single gene testing for mutations, using Sanger sequencing. However, many laboratories are now offering multigene testing using next-generation sequencing that can look at multiple genes, all the way up to whole genome sequencing. Current estimates for the actual cost to the laboratory for a whole genome using next-generation sequencing is about $1,000.

A number of laboratories also have been offering multigene panels for testing in patients with familial cancer syndromes. The genes in these panels include those with a well-documented association with known cancer syndromes as well as other genes where mutations may confer only a modestly increased risk. Furthermore, new genetic syndromes and new genes associated with known syndromes are being reported yearly.

This revolution in technology and the virtual explosion in the amount of data generated have raised as many questions as answers.11 One joke in the genetic testing community goes: “$1,000 genome, $100,000 interpretation.” Among the remaining issues are how to counsel patients about the possible results from multigene testing, including the possibility of results that may be applicable to noncancer-related diagnoses; what to do about the unanticipated actionable finding (incidentaloma); how to interpret and treat a patient whose gene test results are at odds with the clinical family history; how to treat patients whose panel returns with a mutation in a gene that has only a minor increased risk for the cancers; how genes with modestly increased or decreased risk singly or in combination may modify highrisk gene expression; and how to address variants of unknown significance.

A general consensus has emerged that these questions will need much more research correlating genetic and clinical data to answer. As a result, many leading researchers have set up multi-institutional, international collaborative groups directed at specific syndromes, which pool data from many investigators to answer questions beyond the capability of any single investigator or group. These big data collaborative studies are already beginning to publish early results and seem to represent the future of genetic cancer risk assessment, a field that is at once dynamic, exciting, and confusing.4

A major question is whether and how the VA can cooperate with these international consortia. The VA has particular concerns about confidentiality based on past experience, but it also has a unique group of patients who could provide valuable contributions to our knowledge about genetic markers for disease, including cancer. A method for the VA system to provide data to collaborative groups who are advancing our knowledge of the genetic risk factors for cancer while protecting the confidentiality of veterans could provide a model for collaboration between the VA and non-VA health care systems.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Claus EB, Schildkraut JM, Thompson WD, Risch NJ. The genetic attributable risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1996;77(11):2318-2324.

2. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient- Centered Care, v1.2.1. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Accessed July 6, 2015.

3. Campeau PM, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz MD. Hereditary breast cancer: new genetic developments, new therapeutic avenues. Hum Genet. 2008;124(1):31-34.

4. Moreira L, Balaguer F, Lindor N, et al; EPICOLON Consortium. Identification of Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1555-1565.

5. Bülow S, Faurschou Nielsen T, Bülow C, Bisgaard ML, Karlsen L, Moesgaard F. The incidence rate of familial adenomatous polyposis. Results from the Danish Polyposis Register. Int J Colorect Dis. 1996;11(2):88-91.

6. Duncan PR, Lin JT. Ingredients for success: a familial cancer clinic in an oncology

practice setting. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):39-42.

7. Grover S, Kastrinos F, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prevalence and phenotypes of APC and MUTYH mutations in patients with multiple colorectal adenomas. JAMA. 2012;308(5):485-492.

8. Hampel H, de la Chapelle A. How do we approach the goal of identifying everybody with Lynch syndrome? Fam Cancer. 2013;12(2):313-317.

9. Duncan PR, Lin JT, Feddersen R. Prospective screening for Lynch syndrome (LS) in a cohort of colorectal cancer (CRC) surgical patients in a community hospital. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl; abstr 1535):15s.

10. Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(8):1025-1048.

11. Domchek SM, Bradbury A, Garber JE, Offit K, Robson ME. Multiplex genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: out on a high wire without a net? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1267-1270.

Genetic cancers are relatively uncommon but not rare. Although there has not been a comprehensive study of the incidence of cancers that are caused by an identifiable single gene mutation, it is estimated that they account for approximately 5% to 10% of all cancers, or 50,000 to 100,000 patients annually in the U.S.1 The hallmarks of a genetic cancer syndrome are early onset, multiple family members in multiple generations with cancer, bilateral cancer, and multiple cancers in the same person.

Until recently, the VA has not had a significant interest in genetic cancer risk assessment (GCRA). This is changing, however, because veterans with identified genetic risks for cancer can benefit from targeted screening and intervention strategies to lower their risk of dying of cancer. The value of GCRA was also recognized in the 2015 standards for accreditation of the American College of Surgeons, which include a requirement for programs to include a provision for GCRA.2

The 2 most common familial cancer syndromes are hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome, which occurs in about 5% of all patients with breast cancer, and Lynch syndrome (LS), or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (CRC) syndrome, which occurs in about 3% of all patients with CRC.3,4 Other familial cancer syndromes are rare: For example, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) accounts for 0.2% to 0.5% of all CRC cases.5

The Raymond G. Murphy VAMC in Albuquerque is the sole VA hospital in New Mexico. Its catchment area extends into southern Colorado, eastern Arizona, and western Texas. About 40 CRCs and 8 breast cancers are diagnosed at this facility yearly. Given the incidence of these familial cancer syndromes, one might expect to see 1 LS case/year, 1 HBOC case every 2 years, and 1 FAP or attenuated FAP case every 5 to 10 years.

Methods

In 2010, a GCRA clinic was set up to evaluate and manage treatment of veterans who might have inherited a genetic cancer syndrome. Prior to that, veterans with suspected genetic cancer family syndromes were referred to the University of New Mexico for evaluation and testing. Initially, the pathology department (PD) paid for genetic testing. However, due to the cost of testing, a formal budget for genetic testing was approved. Contracts were set up by the PD with outside laboratories for genetic testing services. For quality control, all veterans who were referred for genetic evaluation were seen by Dr. Lin.

The initial consultation consisted of construction of a family pedigree and evaluation, using available models or tables, such as the Myriad tables (BRCA), Penn II BRCA, or PREMM1,2,6 (LS), to estimate likelihood of finding a mutation. Veterans who had a 10% likelihood of finding a gene mutation were counseled, following the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines (Table 1). Those who consented to genetic testing signed a consent form and were given a copy of that form and a copy of their family pedigree. Because the VA covers the cost of counseling and testing, cost was not discussed.

Veterans had a follow-up visit to review the test results. Patients were counseled on treatment recommendations, including a copy of current consensus recommendations, and disclosure to the family. The recommendations were then included in the patient’s electronic medical record. For example, BRCA patients had a discussion of risks and benefits of various management options, including breast magnetic resonance imaging, prophylactic mastectomy, and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, once childbearing was complete.

Results

Table 2 shows the number of veterans referred to the GCRA clinic since it started in late 2010, categorized by the likely genetic syndrome, the number and percentage of veterans where genetic testing was recommended, and the results of testing. Four veterans, 2 with LS, 1 with CHEK2 mutation, and 1 with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, were identified outside the VA system but were referred for counseling. One of the veterans with LS was referred by an outside provider who obtained a suspicious family history, and the other was identified via pathologic screening. The miscellaneous group included 1 veteran with MEN 1 and 1 veteran with Birt-Hogg-Dube.

There are a number of interesting results. Although the number of patients referred for LS was low, the number of annual referrals for possible BRCA was about equal to the number of patients with breast cancer who were diagnosed and treated yearly. Although this could have been due to pent up demand initially, the number of annual referrals has not decreased with time. Furthermore, the number of patients referred for polyposis has been considerably higher than would be expected by the rarity of attenuated FAP. Initially, patients with 10 to 20 polyps of any type were referred for evaluation. All but 1 had their first polyp diagnosed after the age of 50 years. Five veterans who were referred to GCRA had < 10 polyps lifetime, 3 veterans had between 10 and 20 polyps, and 12 veterans have had ≥ 20 adenomatous polyps over their lifetime. None seen to date have had a personal or family history of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer.

Discussion

A genetic cancer risk assessment clinic was set up in a VA hospital and has been running successfully for 4 years. Although many parts of setting up such a clinic are common to a community GCRA clinic, there are also aspects that are specific to a VA setting.6

Because genetic testing is relatively expensive, a budget must be set up and approved by VA administration. This budget is based on the estimated number of veterans that will be referred yearly, the likely percentage that will need to be tested, and the cost of testing. Currently, the average cost of a single gene test is about $2,000 to $3,000. Some patients will need to have 2 to 4 genes tested. Furthermore, many centers are now moving to multigene testing, and the cost of these panels is about $10,000 or more, though this is less than the cumulative cost of the genes done individually.

Since there is currently no national VA contract for genetic cancer testing, each VA facility needs to negotiate contracts with outside laboratories. Several of these laboratories offer gene panel testing, but the panels vary from one laboratory to another.

Limiting the number of providers who can order genetic testing helps maintain quality control and ensure a comprehensive database of patient testing. At the Albuquerque VAMC, Dr. Lin is currently the only provider who can order genetic testing for cancer risk assessment. Nearly all GCRA consultations, from obtaining a detailed family history to providing education on the risks, benefits, and limitations of genetic testing, can be conducted via telemedicine. The VA GCRA program in Utah has established a number of telemedicine collaborations with VA facilities around the country, beginning with BRCA consultations and branching out into a national LS screening program.

The first few years of the program have shown some unexpected results, including a much higher referral rate for HBOC referrals than was anticipated. The reasons for this are not clear. The high rate of polyposis referrals can be attributed in large part to the robust CRC screening program in the VA system. Veterans are routinely screened for CRC with occult blood tests, and positive results are referred for colonoscopy. Nearly 400 veterans per year have a colonoscopy at the Albuquerque VAMC.

Because the VA screening program begins at age 50 years, nearly all the veterans referred to date have had their first polyp diagnosed at age ≥ 50 years. Unfortunately, the 1 patient who had polyps and CRC at a young age was not tested due to lack of budget when she was evaluated. By contrast, in a large study, the median age of first polyp diagnosis in patients with APC mutation was 30 years, and with biallelic MUTYH mutations was 47 years.7

The difficulty in distinguishing which veterans should be tested for attenuated FAP lies in the fact that age of onset and personal or family history alone or in

combination do not seem to be adequate discriminators to screen out low-risk veterans who do not need testing.7 Considering the number of veterans referred each year and the incidence of attenuated FAP, if every veteran who fit the current criteria of 20 adenomatous polyps lifetime were tested, about 35 to 70 veterans would have to be tested to detect 1 mutation carrier. The development of clinical criteria to identify low-risk patients would be very helpful.

On the other hand, referrals for LS were uncommon. This is consistent with results reported elsewhere.8 For this reason, diagnosis of LS has shifted from clinical identification to pathologic screening for the molecular hallmarks of LS in tumor specimens.8,9 Shortly after the GCRA clinic was established, a pathologist with an interest in GI malignancies developed and validated a pathologic screening program using immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for mismatch repair (MMR) gene expression, with the assistance of a pathologist who had been involved in a community-based LS screening program.9 For the past 3 years, all CRC patients aged ≤ 60 years have been screened for loss of expression of MMR IHC. Patients identified have been seen in the GCRA clinic to discuss possible genetic testing. This screening program is now extending to all patients with CRC aged ≤ 70 years, in line with consensus recommendations.10

The Future

The lack of a national VA contract with outside laboratories for genetic testing means that each facility has to negotiate its own contract, which is a wasteful duplication of resources that needs to be addressed. Beyond this parochial concern, GCRA is undergoing a revolution in diagnosing and managing cancer risk. In the past, a careful family history was followed by selected single gene testing for mutations, using Sanger sequencing. However, many laboratories are now offering multigene testing using next-generation sequencing that can look at multiple genes, all the way up to whole genome sequencing. Current estimates for the actual cost to the laboratory for a whole genome using next-generation sequencing is about $1,000.

A number of laboratories also have been offering multigene panels for testing in patients with familial cancer syndromes. The genes in these panels include those with a well-documented association with known cancer syndromes as well as other genes where mutations may confer only a modestly increased risk. Furthermore, new genetic syndromes and new genes associated with known syndromes are being reported yearly.

This revolution in technology and the virtual explosion in the amount of data generated have raised as many questions as answers.11 One joke in the genetic testing community goes: “$1,000 genome, $100,000 interpretation.” Among the remaining issues are how to counsel patients about the possible results from multigene testing, including the possibility of results that may be applicable to noncancer-related diagnoses; what to do about the unanticipated actionable finding (incidentaloma); how to interpret and treat a patient whose gene test results are at odds with the clinical family history; how to treat patients whose panel returns with a mutation in a gene that has only a minor increased risk for the cancers; how genes with modestly increased or decreased risk singly or in combination may modify highrisk gene expression; and how to address variants of unknown significance.

A general consensus has emerged that these questions will need much more research correlating genetic and clinical data to answer. As a result, many leading researchers have set up multi-institutional, international collaborative groups directed at specific syndromes, which pool data from many investigators to answer questions beyond the capability of any single investigator or group. These big data collaborative studies are already beginning to publish early results and seem to represent the future of genetic cancer risk assessment, a field that is at once dynamic, exciting, and confusing.4

A major question is whether and how the VA can cooperate with these international consortia. The VA has particular concerns about confidentiality based on past experience, but it also has a unique group of patients who could provide valuable contributions to our knowledge about genetic markers for disease, including cancer. A method for the VA system to provide data to collaborative groups who are advancing our knowledge of the genetic risk factors for cancer while protecting the confidentiality of veterans could provide a model for collaboration between the VA and non-VA health care systems.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

Genetic cancers are relatively uncommon but not rare. Although there has not been a comprehensive study of the incidence of cancers that are caused by an identifiable single gene mutation, it is estimated that they account for approximately 5% to 10% of all cancers, or 50,000 to 100,000 patients annually in the U.S.1 The hallmarks of a genetic cancer syndrome are early onset, multiple family members in multiple generations with cancer, bilateral cancer, and multiple cancers in the same person.

Until recently, the VA has not had a significant interest in genetic cancer risk assessment (GCRA). This is changing, however, because veterans with identified genetic risks for cancer can benefit from targeted screening and intervention strategies to lower their risk of dying of cancer. The value of GCRA was also recognized in the 2015 standards for accreditation of the American College of Surgeons, which include a requirement for programs to include a provision for GCRA.2

The 2 most common familial cancer syndromes are hereditary breast and ovarian cancer (HBOC) syndrome, which occurs in about 5% of all patients with breast cancer, and Lynch syndrome (LS), or hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (CRC) syndrome, which occurs in about 3% of all patients with CRC.3,4 Other familial cancer syndromes are rare: For example, familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) accounts for 0.2% to 0.5% of all CRC cases.5

The Raymond G. Murphy VAMC in Albuquerque is the sole VA hospital in New Mexico. Its catchment area extends into southern Colorado, eastern Arizona, and western Texas. About 40 CRCs and 8 breast cancers are diagnosed at this facility yearly. Given the incidence of these familial cancer syndromes, one might expect to see 1 LS case/year, 1 HBOC case every 2 years, and 1 FAP or attenuated FAP case every 5 to 10 years.

Methods

In 2010, a GCRA clinic was set up to evaluate and manage treatment of veterans who might have inherited a genetic cancer syndrome. Prior to that, veterans with suspected genetic cancer family syndromes were referred to the University of New Mexico for evaluation and testing. Initially, the pathology department (PD) paid for genetic testing. However, due to the cost of testing, a formal budget for genetic testing was approved. Contracts were set up by the PD with outside laboratories for genetic testing services. For quality control, all veterans who were referred for genetic evaluation were seen by Dr. Lin.

The initial consultation consisted of construction of a family pedigree and evaluation, using available models or tables, such as the Myriad tables (BRCA), Penn II BRCA, or PREMM1,2,6 (LS), to estimate likelihood of finding a mutation. Veterans who had a 10% likelihood of finding a gene mutation were counseled, following the American Society of Clinical Oncology guidelines (Table 1). Those who consented to genetic testing signed a consent form and were given a copy of that form and a copy of their family pedigree. Because the VA covers the cost of counseling and testing, cost was not discussed.

Veterans had a follow-up visit to review the test results. Patients were counseled on treatment recommendations, including a copy of current consensus recommendations, and disclosure to the family. The recommendations were then included in the patient’s electronic medical record. For example, BRCA patients had a discussion of risks and benefits of various management options, including breast magnetic resonance imaging, prophylactic mastectomy, and prophylactic bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, once childbearing was complete.

Results

Table 2 shows the number of veterans referred to the GCRA clinic since it started in late 2010, categorized by the likely genetic syndrome, the number and percentage of veterans where genetic testing was recommended, and the results of testing. Four veterans, 2 with LS, 1 with CHEK2 mutation, and 1 with Peutz-Jeghers syndrome, were identified outside the VA system but were referred for counseling. One of the veterans with LS was referred by an outside provider who obtained a suspicious family history, and the other was identified via pathologic screening. The miscellaneous group included 1 veteran with MEN 1 and 1 veteran with Birt-Hogg-Dube.

There are a number of interesting results. Although the number of patients referred for LS was low, the number of annual referrals for possible BRCA was about equal to the number of patients with breast cancer who were diagnosed and treated yearly. Although this could have been due to pent up demand initially, the number of annual referrals has not decreased with time. Furthermore, the number of patients referred for polyposis has been considerably higher than would be expected by the rarity of attenuated FAP. Initially, patients with 10 to 20 polyps of any type were referred for evaluation. All but 1 had their first polyp diagnosed after the age of 50 years. Five veterans who were referred to GCRA had < 10 polyps lifetime, 3 veterans had between 10 and 20 polyps, and 12 veterans have had ≥ 20 adenomatous polyps over their lifetime. None seen to date have had a personal or family history of gastrointestinal (GI) cancer.

Discussion

A genetic cancer risk assessment clinic was set up in a VA hospital and has been running successfully for 4 years. Although many parts of setting up such a clinic are common to a community GCRA clinic, there are also aspects that are specific to a VA setting.6

Because genetic testing is relatively expensive, a budget must be set up and approved by VA administration. This budget is based on the estimated number of veterans that will be referred yearly, the likely percentage that will need to be tested, and the cost of testing. Currently, the average cost of a single gene test is about $2,000 to $3,000. Some patients will need to have 2 to 4 genes tested. Furthermore, many centers are now moving to multigene testing, and the cost of these panels is about $10,000 or more, though this is less than the cumulative cost of the genes done individually.

Since there is currently no national VA contract for genetic cancer testing, each VA facility needs to negotiate contracts with outside laboratories. Several of these laboratories offer gene panel testing, but the panels vary from one laboratory to another.

Limiting the number of providers who can order genetic testing helps maintain quality control and ensure a comprehensive database of patient testing. At the Albuquerque VAMC, Dr. Lin is currently the only provider who can order genetic testing for cancer risk assessment. Nearly all GCRA consultations, from obtaining a detailed family history to providing education on the risks, benefits, and limitations of genetic testing, can be conducted via telemedicine. The VA GCRA program in Utah has established a number of telemedicine collaborations with VA facilities around the country, beginning with BRCA consultations and branching out into a national LS screening program.

The first few years of the program have shown some unexpected results, including a much higher referral rate for HBOC referrals than was anticipated. The reasons for this are not clear. The high rate of polyposis referrals can be attributed in large part to the robust CRC screening program in the VA system. Veterans are routinely screened for CRC with occult blood tests, and positive results are referred for colonoscopy. Nearly 400 veterans per year have a colonoscopy at the Albuquerque VAMC.

Because the VA screening program begins at age 50 years, nearly all the veterans referred to date have had their first polyp diagnosed at age ≥ 50 years. Unfortunately, the 1 patient who had polyps and CRC at a young age was not tested due to lack of budget when she was evaluated. By contrast, in a large study, the median age of first polyp diagnosis in patients with APC mutation was 30 years, and with biallelic MUTYH mutations was 47 years.7

The difficulty in distinguishing which veterans should be tested for attenuated FAP lies in the fact that age of onset and personal or family history alone or in

combination do not seem to be adequate discriminators to screen out low-risk veterans who do not need testing.7 Considering the number of veterans referred each year and the incidence of attenuated FAP, if every veteran who fit the current criteria of 20 adenomatous polyps lifetime were tested, about 35 to 70 veterans would have to be tested to detect 1 mutation carrier. The development of clinical criteria to identify low-risk patients would be very helpful.

On the other hand, referrals for LS were uncommon. This is consistent with results reported elsewhere.8 For this reason, diagnosis of LS has shifted from clinical identification to pathologic screening for the molecular hallmarks of LS in tumor specimens.8,9 Shortly after the GCRA clinic was established, a pathologist with an interest in GI malignancies developed and validated a pathologic screening program using immunohistochemistry (IHC) staining for mismatch repair (MMR) gene expression, with the assistance of a pathologist who had been involved in a community-based LS screening program.9 For the past 3 years, all CRC patients aged ≤ 60 years have been screened for loss of expression of MMR IHC. Patients identified have been seen in the GCRA clinic to discuss possible genetic testing. This screening program is now extending to all patients with CRC aged ≤ 70 years, in line with consensus recommendations.10

The Future

The lack of a national VA contract with outside laboratories for genetic testing means that each facility has to negotiate its own contract, which is a wasteful duplication of resources that needs to be addressed. Beyond this parochial concern, GCRA is undergoing a revolution in diagnosing and managing cancer risk. In the past, a careful family history was followed by selected single gene testing for mutations, using Sanger sequencing. However, many laboratories are now offering multigene testing using next-generation sequencing that can look at multiple genes, all the way up to whole genome sequencing. Current estimates for the actual cost to the laboratory for a whole genome using next-generation sequencing is about $1,000.

A number of laboratories also have been offering multigene panels for testing in patients with familial cancer syndromes. The genes in these panels include those with a well-documented association with known cancer syndromes as well as other genes where mutations may confer only a modestly increased risk. Furthermore, new genetic syndromes and new genes associated with known syndromes are being reported yearly.

This revolution in technology and the virtual explosion in the amount of data generated have raised as many questions as answers.11 One joke in the genetic testing community goes: “$1,000 genome, $100,000 interpretation.” Among the remaining issues are how to counsel patients about the possible results from multigene testing, including the possibility of results that may be applicable to noncancer-related diagnoses; what to do about the unanticipated actionable finding (incidentaloma); how to interpret and treat a patient whose gene test results are at odds with the clinical family history; how to treat patients whose panel returns with a mutation in a gene that has only a minor increased risk for the cancers; how genes with modestly increased or decreased risk singly or in combination may modify highrisk gene expression; and how to address variants of unknown significance.

A general consensus has emerged that these questions will need much more research correlating genetic and clinical data to answer. As a result, many leading researchers have set up multi-institutional, international collaborative groups directed at specific syndromes, which pool data from many investigators to answer questions beyond the capability of any single investigator or group. These big data collaborative studies are already beginning to publish early results and seem to represent the future of genetic cancer risk assessment, a field that is at once dynamic, exciting, and confusing.4

A major question is whether and how the VA can cooperate with these international consortia. The VA has particular concerns about confidentiality based on past experience, but it also has a unique group of patients who could provide valuable contributions to our knowledge about genetic markers for disease, including cancer. A method for the VA system to provide data to collaborative groups who are advancing our knowledge of the genetic risk factors for cancer while protecting the confidentiality of veterans could provide a model for collaboration between the VA and non-VA health care systems.

Author disclosures

The author reports no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review the complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Claus EB, Schildkraut JM, Thompson WD, Risch NJ. The genetic attributable risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1996;77(11):2318-2324.

2. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient- Centered Care, v1.2.1. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Accessed July 6, 2015.

3. Campeau PM, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz MD. Hereditary breast cancer: new genetic developments, new therapeutic avenues. Hum Genet. 2008;124(1):31-34.

4. Moreira L, Balaguer F, Lindor N, et al; EPICOLON Consortium. Identification of Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1555-1565.

5. Bülow S, Faurschou Nielsen T, Bülow C, Bisgaard ML, Karlsen L, Moesgaard F. The incidence rate of familial adenomatous polyposis. Results from the Danish Polyposis Register. Int J Colorect Dis. 1996;11(2):88-91.

6. Duncan PR, Lin JT. Ingredients for success: a familial cancer clinic in an oncology

practice setting. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):39-42.

7. Grover S, Kastrinos F, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prevalence and phenotypes of APC and MUTYH mutations in patients with multiple colorectal adenomas. JAMA. 2012;308(5):485-492.

8. Hampel H, de la Chapelle A. How do we approach the goal of identifying everybody with Lynch syndrome? Fam Cancer. 2013;12(2):313-317.

9. Duncan PR, Lin JT, Feddersen R. Prospective screening for Lynch syndrome (LS) in a cohort of colorectal cancer (CRC) surgical patients in a community hospital. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl; abstr 1535):15s.

10. Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(8):1025-1048.

11. Domchek SM, Bradbury A, Garber JE, Offit K, Robson ME. Multiplex genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: out on a high wire without a net? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1267-1270.

1. Claus EB, Schildkraut JM, Thompson WD, Risch NJ. The genetic attributable risk of breast and ovarian cancer. Cancer. 1996;77(11):2318-2324.

2. American College of Surgeons. Cancer Program Standards 2012: Ensuring Patient- Centered Care, v1.2.1. Chicago, IL: American College of Surgeons; 2012. https://www.facs.org/~/media/files/quality%20programs/cancer/coc/programstandards2012.ashx. Accessed July 6, 2015.

3. Campeau PM, Foulkes WD, Tischkowitz MD. Hereditary breast cancer: new genetic developments, new therapeutic avenues. Hum Genet. 2008;124(1):31-34.

4. Moreira L, Balaguer F, Lindor N, et al; EPICOLON Consortium. Identification of Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 2012;308(15):1555-1565.

5. Bülow S, Faurschou Nielsen T, Bülow C, Bisgaard ML, Karlsen L, Moesgaard F. The incidence rate of familial adenomatous polyposis. Results from the Danish Polyposis Register. Int J Colorect Dis. 1996;11(2):88-91.

6. Duncan PR, Lin JT. Ingredients for success: a familial cancer clinic in an oncology

practice setting. J Oncol Pract. 2011;7(1):39-42.

7. Grover S, Kastrinos F, Steyerberg EW, et al. Prevalence and phenotypes of APC and MUTYH mutations in patients with multiple colorectal adenomas. JAMA. 2012;308(5):485-492.

8. Hampel H, de la Chapelle A. How do we approach the goal of identifying everybody with Lynch syndrome? Fam Cancer. 2013;12(2):313-317.

9. Duncan PR, Lin JT, Feddersen R. Prospective screening for Lynch syndrome (LS) in a cohort of colorectal cancer (CRC) surgical patients in a community hospital. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(suppl; abstr 1535):15s.

10. Giardiello FM, Allen JI, Axilbund JE, et al. Guidelines on genetic evaluation and management of Lynch syndrome: a consensus statement by the US Multi-Society Task Force on Colorectal Cancer. Dis Colon Rectum. 2014;57(8):1025-1048.

11. Domchek SM, Bradbury A, Garber JE, Offit K, Robson ME. Multiplex genetic testing for cancer susceptibility: out on a high wire without a net? J Clin Oncol. 2013;31(10):1267-1270.

How to discuss sex with elderly patients

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

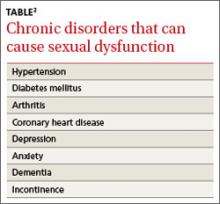

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; [email protected]

1. Balami JS. Are geriatricians guilty of failure to take a sexual history? J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;2:17-20.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.

3. Bradford A, Meston CM. Senior sexual health: The effects of aging on sexuality. In: VandeCreek L, Petersen FL, Bley JW, eds. Innovations in Clinical Practice: Focus on Sexual Health. Sarasota, FL: Professional Resource Press; 2007:35-45.

4. Graber C. Sex keeps elderly happier in marriage. Scientific American.

Available at: http://www.scientificamerican.com/podcast/episode/sex-keeps-elderly-happier-in-marria-11-11-29. Accessed March 26, 2014.

5. Hinchliff S, Gott M. Seeking medical help for sexual concerns in mid- and later life: a review of the literature. J Sex Res. 2011;48:106-117.

6. Tobin JM, Harindra V. Attendance by older patients at a genitourinary medicine clinic. Sex Transm Infect. 2001;77:289-291.

7. Bauer M, McAuliffe L, Nay R. Sexuality, health care and the older person: an overview of the literature. Int J Older People Nurs. 2007;2:63-68.

8. Wallace SP, Cochran SD, Durazo EM, et al. The health of aging lesbian, gay and bisexual adults in California. Policy Brief UCLA Cent Health Policy Res. 2011;(PB2011-2):1-8.

9. Henry J, McNab W. Forever young: a health promotion focus on sexuality and aging. Gerontol Geriatr Education. 2003;23:57-74.

10. Gott M, Hinchliff S, Galena E. General practitioner attitudes to discussing sexual health issues with older people. Soc Sci Med. 2004;58:2093-2103.

11. Nusbaum MR, Hamilton CD. The proactive sexual health history. Am Fam Physician. 2002;66:1705-1712.

12. Burd ID, Nevadunsky N, Bachmann G. Impact of physician gender on sexual history taking in a multispecialty practice. J Sex Med. 2006;3:194-200.

13. Kazer MW. Sexuality Assessment for Older Adults. Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing Web site. Available at: http://consultgerirn.org/uploads/File/trythis/try_this_10.pdf. Updated 2012. Accessed March 14, 2014.

14. Wallace MA. Assessment of sexual health in older adults. Am J Nursing. 2012;108:52-60.

15. Sexuality in later life. National Institute on Aging Web site. Available at: http://www.nia.nih.gov/health/publication/sexualitylater-life. Updated March 11, 2014. Accessed March 21, 2014.

16. Hajjar RR, Kamel HK. Sexuality in the nursing home, part 1: attitudes and barriers to sexual expression. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2004;5(2 suppl):S42-S47.

17. Bildtgård T. The sexuality of elderly people on film—visual limitations. J Aging Identity. 2000;5:169-183.

18. Moreira ED Jr, Brock G, Glasser DB, et al; GSSAB Investigators’ Group. Help-seeking behaviour for sexual problems: the global study of sexual attitudes and behaviors. Int J Clin Pract. 2005;59:6-16.

19. Gott M, Hinchliff S. Barriers to seeking treatment for sexual problems in primary care: a qualitative study with older people. Fam Pract. 2003;20:690-695.

20. Politi MC, Clark MA, Armstrong G, et al. Patient-provider communication about sexual health among unmarried middle-aged and older women. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24:511-516.

21. Bouman W, Arcelus J, Benbow S. Nottingham study of sexuality & ageing (NoSSA I). Attitudes regarding sexuality and older people: a review of the literature. Sex Relationship Ther. 2006;21:149-161.

22. Low LPL, Lui MHL, Lee DTF, et al. Promoting awareness of sexuality of older people in residential care. Electronic J Human Sexuality. 2005;8:8-16.

23. Rheaume C, Mitty E. Sexuality and intimacy in older adults. Geriatr Nurs. 2008;29:342-349.

24. Nagaratnam N, Gayagay G Jr. Hypersexuality in nursing care facilities—a descriptive study. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2002;35:195-203.

25. HIV among older Americans. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/risk/age/olderamericans/. Updated December 23, 2013. Accessed February 28, 2014.

26. Nguyen N, Holodniy M. HIV infection in the elderly. Clin Interv Aging. 2008;3:453-472.

27. Jena AB, Goldman DP, Kamdar A, et al. Sexually transmitted diseases among users of erectile dysfunction drugs: analysis of claims data. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:1-7.

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; [email protected]

› Keep in mind that elderly patients may want to discuss matters of sexuality but can also be embarrassed, fearful, or reluctant to do so with a younger caregiver. C

› Consider making a patient’s sexual history part of your general health screening, perhaps using the PLISSIT model for facilitating discussion. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Sexuality is a central aspect of being human. It encompasses sex, gender identities and roles, sexual orientation, pleasure, eroticism, and intimacy, and is a major contributor to an individual’s quality of life and sense of wellbeing.1,2 Positive sexual relationships and behaviors are integral to maintaining good health and general well-being later in life, as well.2,3 Cynthia Graber, a reporter with Scientific American, reported that sex is a key reason retirees have a happy life.4

While there is a decline in sexual activity with age, a great number of men and women continue to engage in vaginal or anal intercourse, oral sex, and masturbation into the eighth and ninth decades of life.2,5 In a survey conducted among married men and women, about 90% of respondents between the ages of 60 and 64 and almost 30% of those older than age 80 said they were still sexually active.2 Another study reported that 62% of men and 30% of women 80 to 102 years of age were still sexually active.6 However, sexuality is rarely discussed with the elderly, and most physicians are unsure about how to handle such conversations.7

The baby boomer population is aging in the United States and elsewhere. By 2030, 20% of the US population will be ≥65 years old, and 4% (3 million) will be lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) elderly adults.3,8 Given the impact of sex on maintaining quality of life, it is important for health care providers to be comfortable discussing sexuality with the elderly.9

Barriers to discussing sexuality

Physician barriers

Primary care physicians typically are the first point of contact for elderly adults experiencing health problems, including sexual dysfunction. According to the American Psychological Association, sex is not discussed enough with the elderly. Most physicians do not address sexual health proactively, and rarely do they include a sexual history as part of general health screening in the elderly.2,10,11 Inadequate training of physicians in sexual health is likely a contributing factor.5 Physicians also often feel discomfort when discussing such matters with patients of the opposite sex.12 (For a suggested approach to these conversations, see “Discussing sexuality with elderly patients: Getting beyond ‘don’t ask, don’t tell,” below.) With the increasing number of LGBTQ elderly adults, physicians should not assume their patients have any particular sexual behavior or orientation. This will help elderly LGBTQ patients feel more comfortable discussing their sexual health needs.8

The PLISSIT model, developed in 1976 by clinical psychologist Dr. Jack Annon, can facilitate a discussion of sexuality with elderly patients.11,13 First, the healthcare provider seeks permission (P) to discuss sexuality with the patient. After permission is given, the provider can share limited information (LI) about sexual issues that affect the older adult. Next, the provider may offer specific suggestions (SS) to improve sexual health or resolve problems. Finally, referral for intensive therapy (IT) may be needed for someone whose sexual dysfunction goes beyond the scope of the health care provider’s expertise. In 2000, open-ended questions were added to the PLISSIT model to more effectively guide an assessment of sexuality in older adults13,14:

• Can you tell me how you express your sexuality?

• What concerns or questions do you have about fulfilling your continuing sexual needs?

• In what ways has your sexual relationship with your partner changed as you have aged?

Many physicians have only a vague understanding of the sexual needs of the elderly, and some may even consider sexuality among elderly people a taboo.5 The reality is that elderly adults need to be touched, held, and feel loved, and this does not diminish with age.15-17 Unfortunately, many healthcare professionals have a mindset of, “I don’t want to think about my parents having sex, let alone my grandparents.” It is critical that physicians address intimacy needs as part of a medical assessment of the elderly.

Loss of physical and emotional intimacy is profound and often ignored as a source of suffering for the elderly. Most elderly patients want to discuss sexual issues with their physician, according to the Global Study of Sexual Attitudes among men and women ages 40 to 80 years.18 Surprisingly, even geriatricians often fail to take a sexual history of their patients. In one study, only 57% of 120 geriatricians surveyed routinely took a sexual history, even though 97% of them believed that patients with sexual problems should be managed further.1

Patient barriers

Even given a desire to discuss sexual concerns with their health care provider, elderly patients can be reluctant due to embarrassment or a fear of sexuality. Others may hesitate because their caregiver is younger than they or is of the opposite sex.19,20 The attitude of a medical professional has a powerful impact on the sexual attitudes and behaviors of elderly patients, and on their level of comfort in discussing sexual issues.21 Elderly patients do not usually complain to their physicians about sexual dysfunctions; 92% of men and 96% of women who reported at least one sexual problem in a survey had not sought help at all.18

Addressing issues in sexual dysfunction

Though sexual desires and needs may not decline with age, sexual function might, for any number of reasons.1,2,7 Many chronic diseases are known to interfere with sexual function (TABLE).2 Polypharmacy can lead to physical challenges, cognitive changes, and impaired sexual arousal, especially in men.3 However, the reason cited most often for absence of sexual activity is lack of a partner or a willing partner.2 Unfortunately as one ages, the chance of finding a partner diminishes. Hence the need to discuss alternative expressions of sexuality that may not require a partner.3 Many elderly individuals enjoy masturbation as a form of sexual expression.

Men and women have different sexual problems, but they are all treatable. For instance, with normal aging, levels of testosterone in men and estrogen in women decrease.5,15 Despite the number of sexual health dysfunctions, only 14% of men and 1% of women use medications to treat them.2,5 With men who have erectile dysfunction, discuss possible testosterone replacement or medication. For women with postmenopausal (atrophic) vaginitis, estrogen therapy or a lubricant (for those with contraindication to estrogen therapy) can improve sexual function. Anorgasmia and low libido are other concerns for postmenopausal women, and may warrant gynecologic referral.

For elderly adults moving into assisted living or a nursing home, the transition can signal the end of a sexual life.16,22 There is limited opportunity for men and women in residential settings to engage in sexual activity, in part due to a lack of privacy.23 The nursing home is still a home, and facility staff should provide opportunities for privacy and intimacy. In a study conducted in a residential setting, more than 25% of those ages 65 to 85 reported an active sex life, while 90% of those surveyed had sexual thoughts and fantasies.22 Of course, many elderly adults enter residential settings without a partner. They should be allowed to engage in sexual activities if they can understand, consent to, and form a relationship. Sexual needs remain even in those with dementia. But cognitive impairment frequently manifests as inappropriate sexual behavior. A study of cognitively impaired older adults revealed that 1.8% had displayed sexually inappropriate verbal or physical behavior.24 In these situations, a behavior medicine specialist can be of great help.

Health risks of sexual activity in the elderly

In 2011, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 5% of new human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) cases occurred in those ≥55 years, and almost 2% of new diagnoses were in the those ≥65 years.25 Sexually active elderly individuals are at risk for acquiring HIV, in part because they do not consider themselves to be at risk for sexually transmitted diseases (STDs).26 They also might not have received education about the importance of condom use.11,26 In addition, prescribing erectile dysfunction medications for men and hormone replacement therapy for women might have played a part in increasing STDs among the elderly, particularly Chlamydia and HIV.27 The long-term effects of STDs left untreated can easily be mistaken for other symptoms or diseases of aging, which further underscores the importance of discussing sexuality with elderly patients.

CORRESPONDENCE

Folashade Omole, MD, FAAFP, 1513 East Cleveland Avenue, Building 100, Suite 300-A, East Point, GA 30344; [email protected]

1. Balami JS. Are geriatricians guilty of failure to take a sexual history? J Clin Gerontol Geriatr. 2011;2:17-20.

2. Lindau ST, Schumm LP, Laumann EO, et al. A study of sexuality and health among older adults in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:762-774.