User login

When Stephen Tyring, MD, PhD, an infectious disease dermatologist, started his career in the early 1980s, he said “we were diagnosing Kaposi’s sarcoma right and left. We would see a new case every day or two.”

It was the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and dermatologists were at the forefront because HIV/AIDS often presented with skin manifestations. Dr. Tyring, clinical professor in the departments of dermatology, microbiology & molecular genetics and internal medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, and his colleagues referred Kaposi’s patients for chemotherapy and radiation, but the outlook was often grim, especially if lesions developed in the lungs.

Dermatologist don’t see much Kaposi’s anymore because of highly effective treatments for HIV.

Members of the original editorial advisory board saw it coming. In a feature in which board members provided their prediction for the 1970s that appeared in the first issue, New York dermatologist Norman Orentreich, MD, counted the “probable introduction of virucidal agents” as one of the “significant advances or changes that I foresee in the next 10 years.” J. Lamar Callaway, MD, professor of dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., predicted that “the next 10 years should develop effective anti-viral agents for warts, herpes simplex, and herpes zoster.”

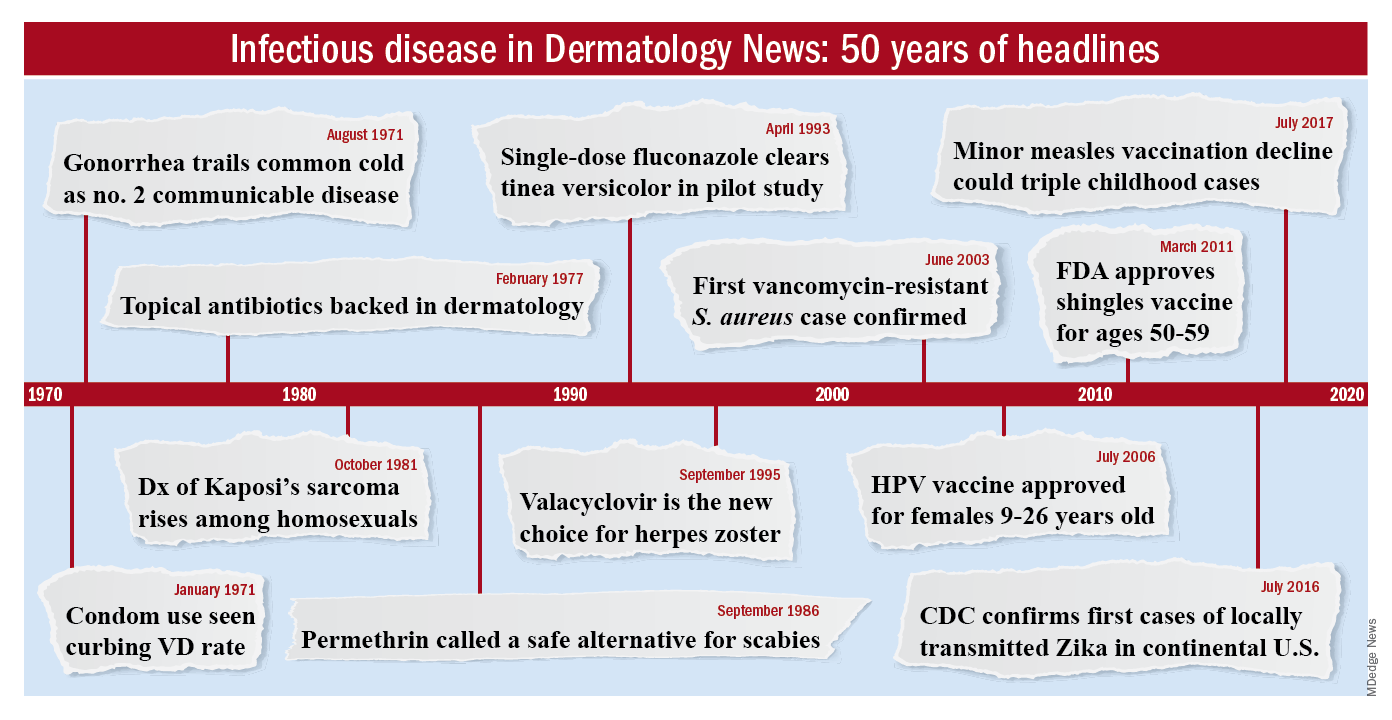

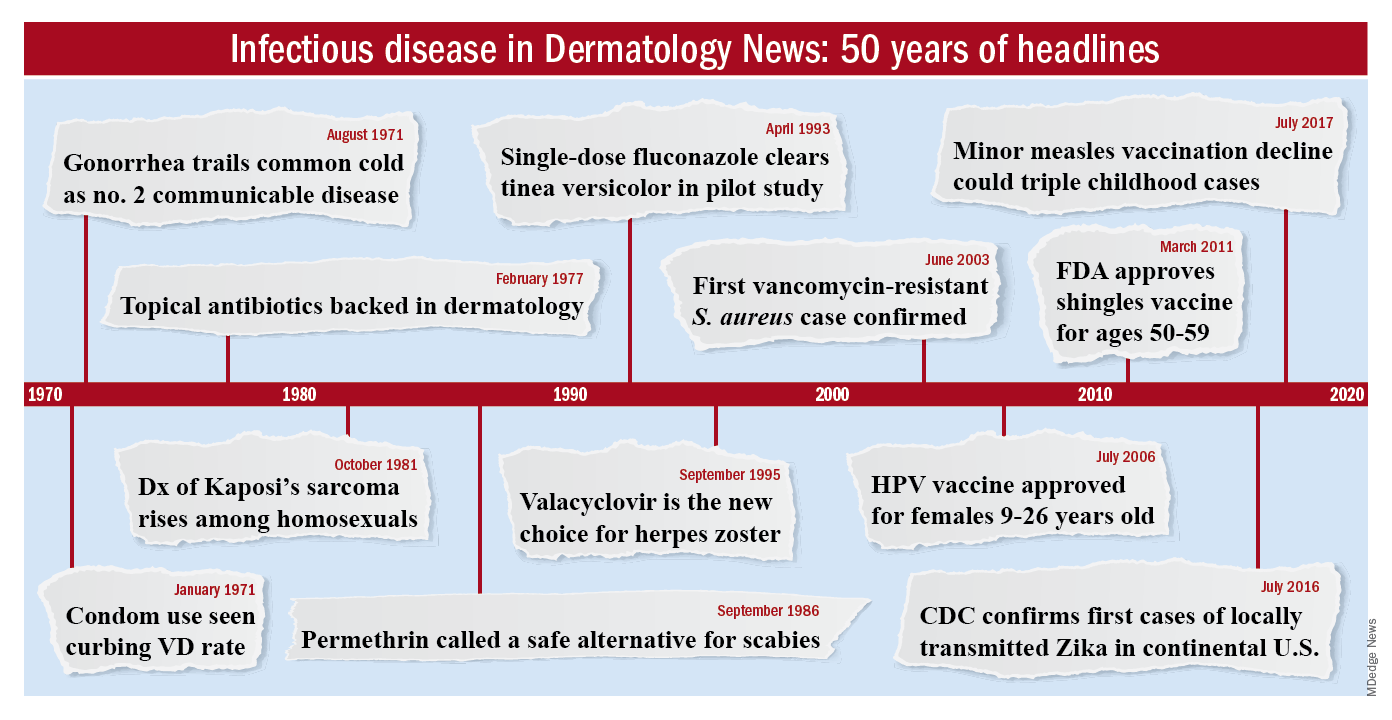

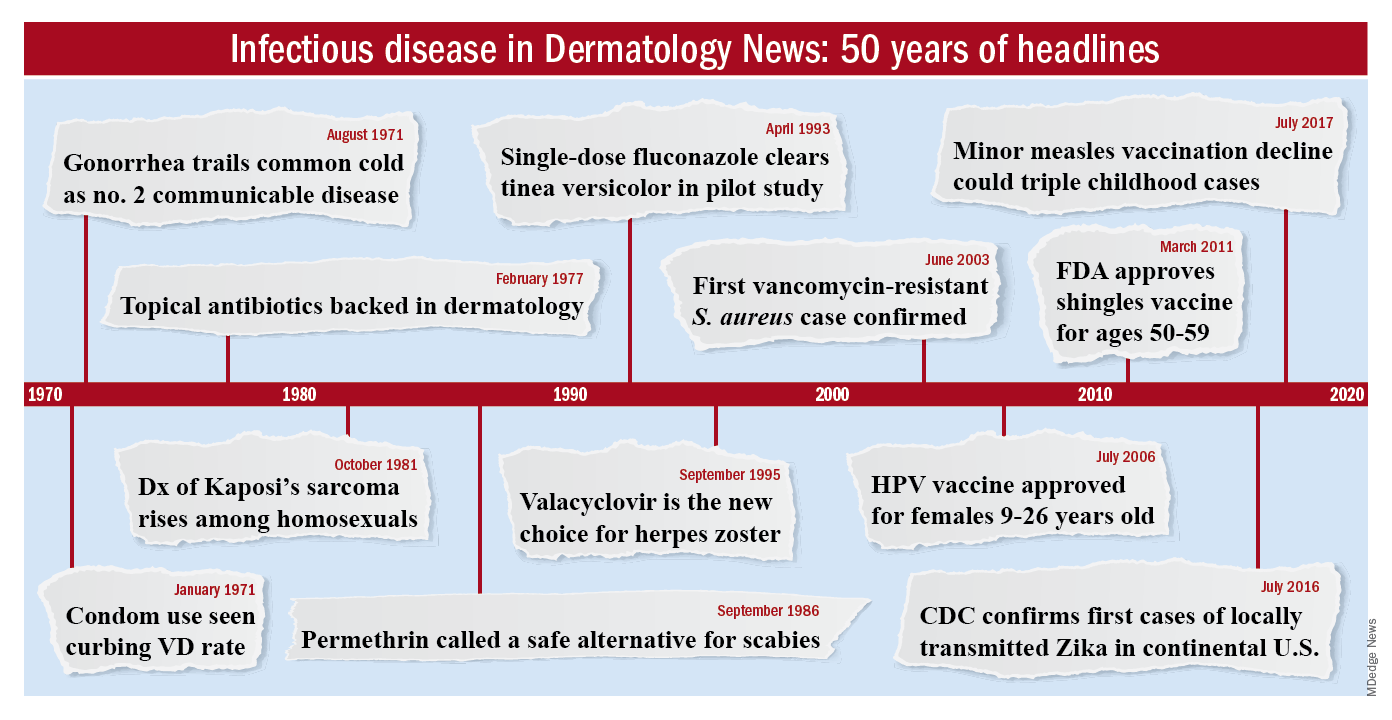

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News, we are looking back at how the field has changed since that first issue. The focus this month is infectious disease. There’s a lot to be grateful for but there are also challenges like antibiotic resistance that weren’t on the radar screens of Dr. Orentreich, Dr. Callaway, and their peers in 1970.

All in all, “the only thing I wish we did the old way is sit at the bedside and talk to patients more. We rely so much on technology now that we sometimes lose the art of medicine, which is comforting to the patient,” said Theodore Rosen, MD, an ID dermatologist and professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who’s been in practice for 42 years.

“A lot of advancements against herpes viruses”

One of the biggest wins for ID dermatology over the last 5 decades has been the management of herpes, both herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, as well as herpes zoster virus. It started with the approval of acyclovir in 1981. Before then, “we had no direct therapy for genital herpes, herpes zoster, or disseminated herpes in immunosuppressed or cancer patients,” Dr. Rosen said.

“I can remember doing an interview with Good Morning America when I gave the first IV dose of acyclovir in the city of Houston for really bad disseminated herpes” in an HIV patient, he said, and it worked.

Two derivatives, valacyclovir and famciclovir, became available in the mid-1990s, so today “we have three drugs and some others at the periphery that are all highly effective not only” against herpes, but also for preventing outbreaks; valacyclovir can even prevent asymptomatic shedding, therefore possibly preventing new infections. “That’s a concept we didn’t even have 40 years ago,” Dr. Rosen said.

Cidofovir has also made a difference. The IV formulation was approved for AIDS-associated cytomegalovirus retinitis in 1996 but discontinued a few years later amid concerns of severe renal toxicity. It’s found a new home in dermatology since then, explained ID dermatologist Carrie Kovarik, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dermatologists see acyclovir-resistant herpes “heaped up on the genitals in HIV patients,” and there weren’t many options in the past. A few years ago, “we [tried] injecting cidofovir directly into the skin lesions, and it’s been remarkably successful. It is a good way to treat these lesions” if dermatologists can get it compounded, she said.

Shingles vaccines, first the live attenuated zoster vaccine (Zostavax) approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2006 and the more effective recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) approved in 2017, have also had a significant impact.

Dr. Rosen remembers what it was like when he first started practicing over 40 years ago. Not uncommonly, “we saw horrible cases of shingles,” including one in his uncle, who was left with permanent hand pain long after the rash subsided.

Today, “I see much less shingles, and when I do see it, it’s in a much-attenuated form. [Shingrix], even if it doesn’t prevent the disease, often prevents postherpetic neuralgia,” he said.

Also, with pediatric vaccinations against chicken pox, “we’re probably going to see a whole new generation without shingles, which is huge. We’ve made a lot of advancements against herpes viruses,” Dr. Kovarik said.

“We finally found something that helps”

“We’ve [also] come a really long way with genital wart treatment,” Dr. Kovarik said.

It started with approval of topical imiquimod in 1997. “Before that, we were just killing one wart here and one wart there” but they would often come back and pop up in other areas. Injectable interferon was an option at the time, but people didn’t like all the needles.

With imiquimod, “we finally [had] a way to target HPV [human papillomavirus] and not just scrape” or freeze one wart at a time, and “we were able to generate an inflammatory response in the whole area to clear the virus.” Working with HIV patients, “I see sheets and sheets of confluent warts throughout the whole genital area; to try to freeze that is impossible. Now I have a way to get rid of [genital] warts and keep them away even if you have a big cluster,” she said.

“Sometimes, we’ll do both liquid nitrogen and imiquimod. That’s a good way to tackle people who have a high burden of warts,” Dr. Kovarik noted. Other effective treatments have come out as well, including an ointment formulation of sinecatechins, extracted from green tea, “but you have to put it on several times a day, and insurance companies don’t cover it often,” she said.

Intralesional cidofovir is also proving to be boon for potentially malignant refractory warts in HIV and transplant patients. “It’s an incredible treatment. We can inject that antiviral into warts and get rid of them. We finally found something that helps” these people, Dr. Kovarik said.

The HPV vaccine Gardasil is making a difference, as well. In addition to cervical dysplasia and anogenital cancers, it protects against two condyloma strains. Dr. Rosen said he’s seeing fewer cases of genital warts now than when he started practicing, likely because of the vaccine.

“Organisms that weren’t pathogens are now pathogens”

Antibiotic resistance probably tops the list for what’s changed in a bad way in ID dermatology since 1970. Dr. Rosen remembers at the start of his career that “we never worried about antibiotic resistance. We’d put people on antibiotics for acne, rosacea, and we’d keep them on them for 3 years, 6 years”; resistance wasn’t on the radar screen and was not mentioned once in the first issue of Dermatology News, which was packed with articles and ran 24 pages.

The situation is different now. Driven by decades of overuse in agriculture and the medical system, antibiotic resistance is a concern throughout medicine, and unfortunately, “we have not come nearly as far as fast with antibiotics,” at least the ones dermatologists use, “as we have with antivirals,” Dr. Tyring said.

For instance, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), first described in the United States in 1968, is “no longer the exception to the rule, but the rule” itself, he said, with carbuncles, furuncles, and abscesses not infrequently growing out MRSA. There are also new drug-resistant forms of old problems like gonorrhea and tuberculosis, among other developments, and impetigo has shifted since 1970 from mostly a Streptococcus infection easily treated with penicillin to often a Staphylococcus disease that’s resistant to it. There’s also been a steady march of new pathogens, including the latest one, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, which has been recognized as having a variety of skin manifestations.

“No matter how smart we think we are, nature has a way of putting us back in our place,” Dr. Rosen said.

The bright spot is that “we’ve become very adept at identifying and characterizing” microbes “based on techniques we didn’t even have when I started practicing,” such as polymerase chain reaction. “It has taken a lot of guess work out of treating infectious diseases,” he said.

The widespread use of immunosuppressives such as cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, azathioprine, rituximab, and other agents used in conjunction with solid organ transplantation, has also been a challenge. “We are seeing infections with really odd organisms. Just recently, I had a patient with fusarium in the skin; it’s a fungus that lives in the dirt. I saw a patient with a species of algae” that normally lives in stagnant water, he commented. “We used to get [things like that] back on reports, and we’d throw them away. You can’t do that anymore. Organisms that weren’t pathogens in the past are now pathogens,” particularly in immunosuppressed people, Dr. Rosen said.

Venereologists no more

There’s been another big change in the field. “Back in the not too distant past, dermatologists in the U.S. were referred to as ‘dermatologist-venereologists.’ ” It goes back to the time when syphilis wasn’t diagnosed and treated early, so patients often presented with secondary skin complications and went to dermatologists for help. As a result, “dermatologists became the most experienced at treating it,” Dr. Tyring said.

That’s faded from practice. Part of the reason is that as late as 2000, syphilis seemed to be on the way out; the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention even raised the possibility of elimination. Dermatologists turned their attention to other areas.

It might have been short-sighted, Dr. Rosen said. Syphilis has made a strong comeback, and drug-resistant gonorrhea has also emerged globally and in at least a few states. No other medical field has stepped in to take up the slack. “Ob.gyns. are busy delivering babies, ID [physicians are] concerned about HIV, and urologists are worried about kidney stones and cancer.” Other than herpes and genital warts, “we have not done well” with management of sexually transmitted diseases, he said.

“I could sense” his frustration

The first issue of Dermatology News carried an article and photospread about scabies that could run today, except that topical permethrin and oral ivermectin have largely replaced benzyl benzoate and sulfur ointments for treatment in the United States. In the article, Scottish dermatologist J. O’D. Alexander, MD, called scabies “the scourge of mankind” and blamed it’s prevalence on “an offhand attitude to the disease which makes control very difficult.”

“I could sense this man’s frustration that people were not recognizing scabies,” Dr. Kovarik said, and it’s no closer to being eradicated than it was in 1970. “It’s still around, and we see it in our clinics. It’s a horrible disease in kids we see in dermatology not infrequently,” and treatment has only advanced a bit.

The article highlights what hasn’t changed much in ID dermatology over the years. Common warts are another one. “With all the evolution in medicine, we don’t have any better treatments approved for common warts than we ever had.” Injecting cidofovir “works great,” but access is a problem, Dr. Tyring said.

Onychomycosis has also proven a tough nut to crack. Readers back in 1970 counted the introduction of the antifungal, griseofulvin, as a major advancement in the 1960s; it’s still a go-to for tinea capitis, but it didn’t work very well for toenail fungus. Terbinafine (Lamisil), approved in 1993, and subsequent developments have helped, but the field still awaits more effective options; a few potential new agents are in the pipeline.

Although there have been major advancements for serious systemic fungal infections, “we’ve mainly seen small steps forward” in ID dermatology, Dr. Tyring said.

Dr. Tyring, Dr. Kovarik, and Dr. Rosen said they had no relevant disclosures.

When Stephen Tyring, MD, PhD, an infectious disease dermatologist, started his career in the early 1980s, he said “we were diagnosing Kaposi’s sarcoma right and left. We would see a new case every day or two.”

It was the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and dermatologists were at the forefront because HIV/AIDS often presented with skin manifestations. Dr. Tyring, clinical professor in the departments of dermatology, microbiology & molecular genetics and internal medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, and his colleagues referred Kaposi’s patients for chemotherapy and radiation, but the outlook was often grim, especially if lesions developed in the lungs.

Dermatologist don’t see much Kaposi’s anymore because of highly effective treatments for HIV.

Members of the original editorial advisory board saw it coming. In a feature in which board members provided their prediction for the 1970s that appeared in the first issue, New York dermatologist Norman Orentreich, MD, counted the “probable introduction of virucidal agents” as one of the “significant advances or changes that I foresee in the next 10 years.” J. Lamar Callaway, MD, professor of dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., predicted that “the next 10 years should develop effective anti-viral agents for warts, herpes simplex, and herpes zoster.”

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News, we are looking back at how the field has changed since that first issue. The focus this month is infectious disease. There’s a lot to be grateful for but there are also challenges like antibiotic resistance that weren’t on the radar screens of Dr. Orentreich, Dr. Callaway, and their peers in 1970.

All in all, “the only thing I wish we did the old way is sit at the bedside and talk to patients more. We rely so much on technology now that we sometimes lose the art of medicine, which is comforting to the patient,” said Theodore Rosen, MD, an ID dermatologist and professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who’s been in practice for 42 years.

“A lot of advancements against herpes viruses”

One of the biggest wins for ID dermatology over the last 5 decades has been the management of herpes, both herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, as well as herpes zoster virus. It started with the approval of acyclovir in 1981. Before then, “we had no direct therapy for genital herpes, herpes zoster, or disseminated herpes in immunosuppressed or cancer patients,” Dr. Rosen said.

“I can remember doing an interview with Good Morning America when I gave the first IV dose of acyclovir in the city of Houston for really bad disseminated herpes” in an HIV patient, he said, and it worked.

Two derivatives, valacyclovir and famciclovir, became available in the mid-1990s, so today “we have three drugs and some others at the periphery that are all highly effective not only” against herpes, but also for preventing outbreaks; valacyclovir can even prevent asymptomatic shedding, therefore possibly preventing new infections. “That’s a concept we didn’t even have 40 years ago,” Dr. Rosen said.

Cidofovir has also made a difference. The IV formulation was approved for AIDS-associated cytomegalovirus retinitis in 1996 but discontinued a few years later amid concerns of severe renal toxicity. It’s found a new home in dermatology since then, explained ID dermatologist Carrie Kovarik, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dermatologists see acyclovir-resistant herpes “heaped up on the genitals in HIV patients,” and there weren’t many options in the past. A few years ago, “we [tried] injecting cidofovir directly into the skin lesions, and it’s been remarkably successful. It is a good way to treat these lesions” if dermatologists can get it compounded, she said.

Shingles vaccines, first the live attenuated zoster vaccine (Zostavax) approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2006 and the more effective recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) approved in 2017, have also had a significant impact.

Dr. Rosen remembers what it was like when he first started practicing over 40 years ago. Not uncommonly, “we saw horrible cases of shingles,” including one in his uncle, who was left with permanent hand pain long after the rash subsided.

Today, “I see much less shingles, and when I do see it, it’s in a much-attenuated form. [Shingrix], even if it doesn’t prevent the disease, often prevents postherpetic neuralgia,” he said.

Also, with pediatric vaccinations against chicken pox, “we’re probably going to see a whole new generation without shingles, which is huge. We’ve made a lot of advancements against herpes viruses,” Dr. Kovarik said.

“We finally found something that helps”

“We’ve [also] come a really long way with genital wart treatment,” Dr. Kovarik said.

It started with approval of topical imiquimod in 1997. “Before that, we were just killing one wart here and one wart there” but they would often come back and pop up in other areas. Injectable interferon was an option at the time, but people didn’t like all the needles.

With imiquimod, “we finally [had] a way to target HPV [human papillomavirus] and not just scrape” or freeze one wart at a time, and “we were able to generate an inflammatory response in the whole area to clear the virus.” Working with HIV patients, “I see sheets and sheets of confluent warts throughout the whole genital area; to try to freeze that is impossible. Now I have a way to get rid of [genital] warts and keep them away even if you have a big cluster,” she said.

“Sometimes, we’ll do both liquid nitrogen and imiquimod. That’s a good way to tackle people who have a high burden of warts,” Dr. Kovarik noted. Other effective treatments have come out as well, including an ointment formulation of sinecatechins, extracted from green tea, “but you have to put it on several times a day, and insurance companies don’t cover it often,” she said.

Intralesional cidofovir is also proving to be boon for potentially malignant refractory warts in HIV and transplant patients. “It’s an incredible treatment. We can inject that antiviral into warts and get rid of them. We finally found something that helps” these people, Dr. Kovarik said.

The HPV vaccine Gardasil is making a difference, as well. In addition to cervical dysplasia and anogenital cancers, it protects against two condyloma strains. Dr. Rosen said he’s seeing fewer cases of genital warts now than when he started practicing, likely because of the vaccine.

“Organisms that weren’t pathogens are now pathogens”

Antibiotic resistance probably tops the list for what’s changed in a bad way in ID dermatology since 1970. Dr. Rosen remembers at the start of his career that “we never worried about antibiotic resistance. We’d put people on antibiotics for acne, rosacea, and we’d keep them on them for 3 years, 6 years”; resistance wasn’t on the radar screen and was not mentioned once in the first issue of Dermatology News, which was packed with articles and ran 24 pages.

The situation is different now. Driven by decades of overuse in agriculture and the medical system, antibiotic resistance is a concern throughout medicine, and unfortunately, “we have not come nearly as far as fast with antibiotics,” at least the ones dermatologists use, “as we have with antivirals,” Dr. Tyring said.

For instance, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), first described in the United States in 1968, is “no longer the exception to the rule, but the rule” itself, he said, with carbuncles, furuncles, and abscesses not infrequently growing out MRSA. There are also new drug-resistant forms of old problems like gonorrhea and tuberculosis, among other developments, and impetigo has shifted since 1970 from mostly a Streptococcus infection easily treated with penicillin to often a Staphylococcus disease that’s resistant to it. There’s also been a steady march of new pathogens, including the latest one, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, which has been recognized as having a variety of skin manifestations.

“No matter how smart we think we are, nature has a way of putting us back in our place,” Dr. Rosen said.

The bright spot is that “we’ve become very adept at identifying and characterizing” microbes “based on techniques we didn’t even have when I started practicing,” such as polymerase chain reaction. “It has taken a lot of guess work out of treating infectious diseases,” he said.

The widespread use of immunosuppressives such as cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, azathioprine, rituximab, and other agents used in conjunction with solid organ transplantation, has also been a challenge. “We are seeing infections with really odd organisms. Just recently, I had a patient with fusarium in the skin; it’s a fungus that lives in the dirt. I saw a patient with a species of algae” that normally lives in stagnant water, he commented. “We used to get [things like that] back on reports, and we’d throw them away. You can’t do that anymore. Organisms that weren’t pathogens in the past are now pathogens,” particularly in immunosuppressed people, Dr. Rosen said.

Venereologists no more

There’s been another big change in the field. “Back in the not too distant past, dermatologists in the U.S. were referred to as ‘dermatologist-venereologists.’ ” It goes back to the time when syphilis wasn’t diagnosed and treated early, so patients often presented with secondary skin complications and went to dermatologists for help. As a result, “dermatologists became the most experienced at treating it,” Dr. Tyring said.

That’s faded from practice. Part of the reason is that as late as 2000, syphilis seemed to be on the way out; the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention even raised the possibility of elimination. Dermatologists turned their attention to other areas.

It might have been short-sighted, Dr. Rosen said. Syphilis has made a strong comeback, and drug-resistant gonorrhea has also emerged globally and in at least a few states. No other medical field has stepped in to take up the slack. “Ob.gyns. are busy delivering babies, ID [physicians are] concerned about HIV, and urologists are worried about kidney stones and cancer.” Other than herpes and genital warts, “we have not done well” with management of sexually transmitted diseases, he said.

“I could sense” his frustration

The first issue of Dermatology News carried an article and photospread about scabies that could run today, except that topical permethrin and oral ivermectin have largely replaced benzyl benzoate and sulfur ointments for treatment in the United States. In the article, Scottish dermatologist J. O’D. Alexander, MD, called scabies “the scourge of mankind” and blamed it’s prevalence on “an offhand attitude to the disease which makes control very difficult.”

“I could sense this man’s frustration that people were not recognizing scabies,” Dr. Kovarik said, and it’s no closer to being eradicated than it was in 1970. “It’s still around, and we see it in our clinics. It’s a horrible disease in kids we see in dermatology not infrequently,” and treatment has only advanced a bit.

The article highlights what hasn’t changed much in ID dermatology over the years. Common warts are another one. “With all the evolution in medicine, we don’t have any better treatments approved for common warts than we ever had.” Injecting cidofovir “works great,” but access is a problem, Dr. Tyring said.

Onychomycosis has also proven a tough nut to crack. Readers back in 1970 counted the introduction of the antifungal, griseofulvin, as a major advancement in the 1960s; it’s still a go-to for tinea capitis, but it didn’t work very well for toenail fungus. Terbinafine (Lamisil), approved in 1993, and subsequent developments have helped, but the field still awaits more effective options; a few potential new agents are in the pipeline.

Although there have been major advancements for serious systemic fungal infections, “we’ve mainly seen small steps forward” in ID dermatology, Dr. Tyring said.

Dr. Tyring, Dr. Kovarik, and Dr. Rosen said they had no relevant disclosures.

When Stephen Tyring, MD, PhD, an infectious disease dermatologist, started his career in the early 1980s, he said “we were diagnosing Kaposi’s sarcoma right and left. We would see a new case every day or two.”

It was the early days of the HIV/AIDS epidemic, and dermatologists were at the forefront because HIV/AIDS often presented with skin manifestations. Dr. Tyring, clinical professor in the departments of dermatology, microbiology & molecular genetics and internal medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center, Houston, and his colleagues referred Kaposi’s patients for chemotherapy and radiation, but the outlook was often grim, especially if lesions developed in the lungs.

Dermatologist don’t see much Kaposi’s anymore because of highly effective treatments for HIV.

Members of the original editorial advisory board saw it coming. In a feature in which board members provided their prediction for the 1970s that appeared in the first issue, New York dermatologist Norman Orentreich, MD, counted the “probable introduction of virucidal agents” as one of the “significant advances or changes that I foresee in the next 10 years.” J. Lamar Callaway, MD, professor of dermatology at Duke University, Durham, N.C., predicted that “the next 10 years should develop effective anti-viral agents for warts, herpes simplex, and herpes zoster.”

To celebrate the 50th anniversary of Dermatology News, we are looking back at how the field has changed since that first issue. The focus this month is infectious disease. There’s a lot to be grateful for but there are also challenges like antibiotic resistance that weren’t on the radar screens of Dr. Orentreich, Dr. Callaway, and their peers in 1970.

All in all, “the only thing I wish we did the old way is sit at the bedside and talk to patients more. We rely so much on technology now that we sometimes lose the art of medicine, which is comforting to the patient,” said Theodore Rosen, MD, an ID dermatologist and professor of dermatology at Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, who’s been in practice for 42 years.

“A lot of advancements against herpes viruses”

One of the biggest wins for ID dermatology over the last 5 decades has been the management of herpes, both herpes simplex virus 1 and 2, as well as herpes zoster virus. It started with the approval of acyclovir in 1981. Before then, “we had no direct therapy for genital herpes, herpes zoster, or disseminated herpes in immunosuppressed or cancer patients,” Dr. Rosen said.

“I can remember doing an interview with Good Morning America when I gave the first IV dose of acyclovir in the city of Houston for really bad disseminated herpes” in an HIV patient, he said, and it worked.

Two derivatives, valacyclovir and famciclovir, became available in the mid-1990s, so today “we have three drugs and some others at the periphery that are all highly effective not only” against herpes, but also for preventing outbreaks; valacyclovir can even prevent asymptomatic shedding, therefore possibly preventing new infections. “That’s a concept we didn’t even have 40 years ago,” Dr. Rosen said.

Cidofovir has also made a difference. The IV formulation was approved for AIDS-associated cytomegalovirus retinitis in 1996 but discontinued a few years later amid concerns of severe renal toxicity. It’s found a new home in dermatology since then, explained ID dermatologist Carrie Kovarik, MD, associate professor of dermatology at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

Dermatologists see acyclovir-resistant herpes “heaped up on the genitals in HIV patients,” and there weren’t many options in the past. A few years ago, “we [tried] injecting cidofovir directly into the skin lesions, and it’s been remarkably successful. It is a good way to treat these lesions” if dermatologists can get it compounded, she said.

Shingles vaccines, first the live attenuated zoster vaccine (Zostavax) approved by the Food and Drug Administration in 2006 and the more effective recombinant zoster vaccine (Shingrix) approved in 2017, have also had a significant impact.

Dr. Rosen remembers what it was like when he first started practicing over 40 years ago. Not uncommonly, “we saw horrible cases of shingles,” including one in his uncle, who was left with permanent hand pain long after the rash subsided.

Today, “I see much less shingles, and when I do see it, it’s in a much-attenuated form. [Shingrix], even if it doesn’t prevent the disease, often prevents postherpetic neuralgia,” he said.

Also, with pediatric vaccinations against chicken pox, “we’re probably going to see a whole new generation without shingles, which is huge. We’ve made a lot of advancements against herpes viruses,” Dr. Kovarik said.

“We finally found something that helps”

“We’ve [also] come a really long way with genital wart treatment,” Dr. Kovarik said.

It started with approval of topical imiquimod in 1997. “Before that, we were just killing one wart here and one wart there” but they would often come back and pop up in other areas. Injectable interferon was an option at the time, but people didn’t like all the needles.

With imiquimod, “we finally [had] a way to target HPV [human papillomavirus] and not just scrape” or freeze one wart at a time, and “we were able to generate an inflammatory response in the whole area to clear the virus.” Working with HIV patients, “I see sheets and sheets of confluent warts throughout the whole genital area; to try to freeze that is impossible. Now I have a way to get rid of [genital] warts and keep them away even if you have a big cluster,” she said.

“Sometimes, we’ll do both liquid nitrogen and imiquimod. That’s a good way to tackle people who have a high burden of warts,” Dr. Kovarik noted. Other effective treatments have come out as well, including an ointment formulation of sinecatechins, extracted from green tea, “but you have to put it on several times a day, and insurance companies don’t cover it often,” she said.

Intralesional cidofovir is also proving to be boon for potentially malignant refractory warts in HIV and transplant patients. “It’s an incredible treatment. We can inject that antiviral into warts and get rid of them. We finally found something that helps” these people, Dr. Kovarik said.

The HPV vaccine Gardasil is making a difference, as well. In addition to cervical dysplasia and anogenital cancers, it protects against two condyloma strains. Dr. Rosen said he’s seeing fewer cases of genital warts now than when he started practicing, likely because of the vaccine.

“Organisms that weren’t pathogens are now pathogens”

Antibiotic resistance probably tops the list for what’s changed in a bad way in ID dermatology since 1970. Dr. Rosen remembers at the start of his career that “we never worried about antibiotic resistance. We’d put people on antibiotics for acne, rosacea, and we’d keep them on them for 3 years, 6 years”; resistance wasn’t on the radar screen and was not mentioned once in the first issue of Dermatology News, which was packed with articles and ran 24 pages.

The situation is different now. Driven by decades of overuse in agriculture and the medical system, antibiotic resistance is a concern throughout medicine, and unfortunately, “we have not come nearly as far as fast with antibiotics,” at least the ones dermatologists use, “as we have with antivirals,” Dr. Tyring said.

For instance, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), first described in the United States in 1968, is “no longer the exception to the rule, but the rule” itself, he said, with carbuncles, furuncles, and abscesses not infrequently growing out MRSA. There are also new drug-resistant forms of old problems like gonorrhea and tuberculosis, among other developments, and impetigo has shifted since 1970 from mostly a Streptococcus infection easily treated with penicillin to often a Staphylococcus disease that’s resistant to it. There’s also been a steady march of new pathogens, including the latest one, SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19, which has been recognized as having a variety of skin manifestations.

“No matter how smart we think we are, nature has a way of putting us back in our place,” Dr. Rosen said.

The bright spot is that “we’ve become very adept at identifying and characterizing” microbes “based on techniques we didn’t even have when I started practicing,” such as polymerase chain reaction. “It has taken a lot of guess work out of treating infectious diseases,” he said.

The widespread use of immunosuppressives such as cyclophosphamide, mycophenolate, azathioprine, rituximab, and other agents used in conjunction with solid organ transplantation, has also been a challenge. “We are seeing infections with really odd organisms. Just recently, I had a patient with fusarium in the skin; it’s a fungus that lives in the dirt. I saw a patient with a species of algae” that normally lives in stagnant water, he commented. “We used to get [things like that] back on reports, and we’d throw them away. You can’t do that anymore. Organisms that weren’t pathogens in the past are now pathogens,” particularly in immunosuppressed people, Dr. Rosen said.

Venereologists no more

There’s been another big change in the field. “Back in the not too distant past, dermatologists in the U.S. were referred to as ‘dermatologist-venereologists.’ ” It goes back to the time when syphilis wasn’t diagnosed and treated early, so patients often presented with secondary skin complications and went to dermatologists for help. As a result, “dermatologists became the most experienced at treating it,” Dr. Tyring said.

That’s faded from practice. Part of the reason is that as late as 2000, syphilis seemed to be on the way out; the Centers for Disease and Control and Prevention even raised the possibility of elimination. Dermatologists turned their attention to other areas.

It might have been short-sighted, Dr. Rosen said. Syphilis has made a strong comeback, and drug-resistant gonorrhea has also emerged globally and in at least a few states. No other medical field has stepped in to take up the slack. “Ob.gyns. are busy delivering babies, ID [physicians are] concerned about HIV, and urologists are worried about kidney stones and cancer.” Other than herpes and genital warts, “we have not done well” with management of sexually transmitted diseases, he said.

“I could sense” his frustration

The first issue of Dermatology News carried an article and photospread about scabies that could run today, except that topical permethrin and oral ivermectin have largely replaced benzyl benzoate and sulfur ointments for treatment in the United States. In the article, Scottish dermatologist J. O’D. Alexander, MD, called scabies “the scourge of mankind” and blamed it’s prevalence on “an offhand attitude to the disease which makes control very difficult.”

“I could sense this man’s frustration that people were not recognizing scabies,” Dr. Kovarik said, and it’s no closer to being eradicated than it was in 1970. “It’s still around, and we see it in our clinics. It’s a horrible disease in kids we see in dermatology not infrequently,” and treatment has only advanced a bit.

The article highlights what hasn’t changed much in ID dermatology over the years. Common warts are another one. “With all the evolution in medicine, we don’t have any better treatments approved for common warts than we ever had.” Injecting cidofovir “works great,” but access is a problem, Dr. Tyring said.

Onychomycosis has also proven a tough nut to crack. Readers back in 1970 counted the introduction of the antifungal, griseofulvin, as a major advancement in the 1960s; it’s still a go-to for tinea capitis, but it didn’t work very well for toenail fungus. Terbinafine (Lamisil), approved in 1993, and subsequent developments have helped, but the field still awaits more effective options; a few potential new agents are in the pipeline.

Although there have been major advancements for serious systemic fungal infections, “we’ve mainly seen small steps forward” in ID dermatology, Dr. Tyring said.

Dr. Tyring, Dr. Kovarik, and Dr. Rosen said they had no relevant disclosures.