User login

Provider attire has come under scrutiny in the more recent medical literature. Epidemiologic data have shown that lab coats, ties, and other articles of clothing are frequently contaminated with disease-causing pathogens including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus , vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Acinetobacter species, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomona s species, and Clostridium difficile.1 Clothing may serve as a vector for spread of these bacteria and may contribute to hospital-acquired infections, increased cost of care, and patient morbidity. Prior to February 2015, the dermatology service line at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania, had followed a formal dress code that included white lab coats (white coats) along with long-sleeve shirts and ties/bowties for male providers and blouses, skirts, dress pants, and dresses for female providers. After a review of the recent literature on contamination rates of provider attire,2 we transitioned away from formal attire to adopt fitted, embroidered, black or navy blue scrubs to be worn in the clinic (Figure). Fitted scrubs differ from traditional unisex operating room scrubs, conferring a more professional appearance.

Limited research has shown that dermatology patients may have a slight preference for formal provider attire.2,3 In these studies, patients were shown photographs of providers in various dress (ie, professional attire, business attire, casual attire, scrubs). Patients preferred or had more confidence in the photograph of the provider in professional attire2,3; however, it is unclear if dermatology provider attire has any measurable effect on overall patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction relies on a myriad of factors, including both spoken and unspoken communication skills. Patient satisfaction has become an integral part of health care, and with an emphasis on value-based care, it will likely be one determining factor in how providers are reimbursed for their services.4,5 In this study, we investigated if a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs influenced patient satisfaction using a common third-party patient satisfaction survey.

Methods

Patient Satisfaction Survey

We conducted a retrospective cohort study analyzing 10 questions from the care provider section of the Press Ganey third-party patient satisfaction survey regarding providers in our dermatology service line. Only providers with at least 12 months of survey data before (study period 1) and after (study period 2) the change in attire were included in the study. Mohs surgeons were excluded, as they already wore fitted scrubs in the clinic. Residents also were excluded, as they are rapidly developing their patient communication skills and may have a notable change in patient satisfaction over a 2-year period.

The survey data were collected, and provider names were removed and replaced with alphanumeric codes to protect anonymity while still allowing individual provider analysis. Aggregate patient comments from surveys before and after the change in attire were digitally searched using the terms scrub, coat, white, attire, and clothing for pertinent positive or negative comments.

Outcomes

We compared individual and aggregate satisfaction scores for our providers during the 12-month periods before and after the adoption of fitted scrubs. The primary outcome was statistically significant change in patient satisfaction scores before and after the institution of fitted scrubs. Secondary outcomes included summation of patient comments, both positive and negative, regarding provider attire, as recorded on satisfaction surveys.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survey scores and scores on individual survey items were summarized using mean (SD), median and interquartile range, or frequency counts and percentage, as appropriate. The overall satisfaction score and responses to individual survey items were compared using Mantel-Haenszel or Pearson χ2 tests, as appropriate.

Assuming an equal number of surveys would be completed during study periods 1 and 2, an average (SD) satisfaction score of 95.4 (15), we calculated that as many as 2136 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −1.9 and 1.9 (a 1% difference). As few as 352 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −4.7 and 4.7 (a 5% difference). Sample size calculations assume 80% power and a significance level of 0.05. Comparison of responses for study periods 1 and 2 were made using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test.

Because more than 80% of respondents selected very good for each question, the responses also were treated as dichotomous variables with a category for very good and a category for responses that were lower than very good (ie, good, fair, poor, very poor). Responses of very good versus less than very good were compared for the study periods 1 and 2 using the Pearson χ2 test.

Two versions of an overall score were analyzed. The first version was for patients who responded to at least 1 of 10 survey items. If responses to all the items were very good, the patient was assigned to the category of all very good. If a patient answered any of the questions with a response less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. The second version was for patients who responded to all 10 survey items. If all 10 responses were very good, the patient was assigned to a category of all very good. If any of the 10 responses were less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. Differences between study periods for both score versions were tested using the Pearson χ2 test.

Results

Data for 22 providers in the dermatology service line—13 staff dermatologists, 6 physician assistants, 1 nurse practitioner, and 2 podiatrists—were included in the study, with a total of 7702 patient satisfaction surveys completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2016: 3511 were completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015 (study period 1), and 4191 were completed between February 1, 2015, and January 31, 2016 (study period 2).

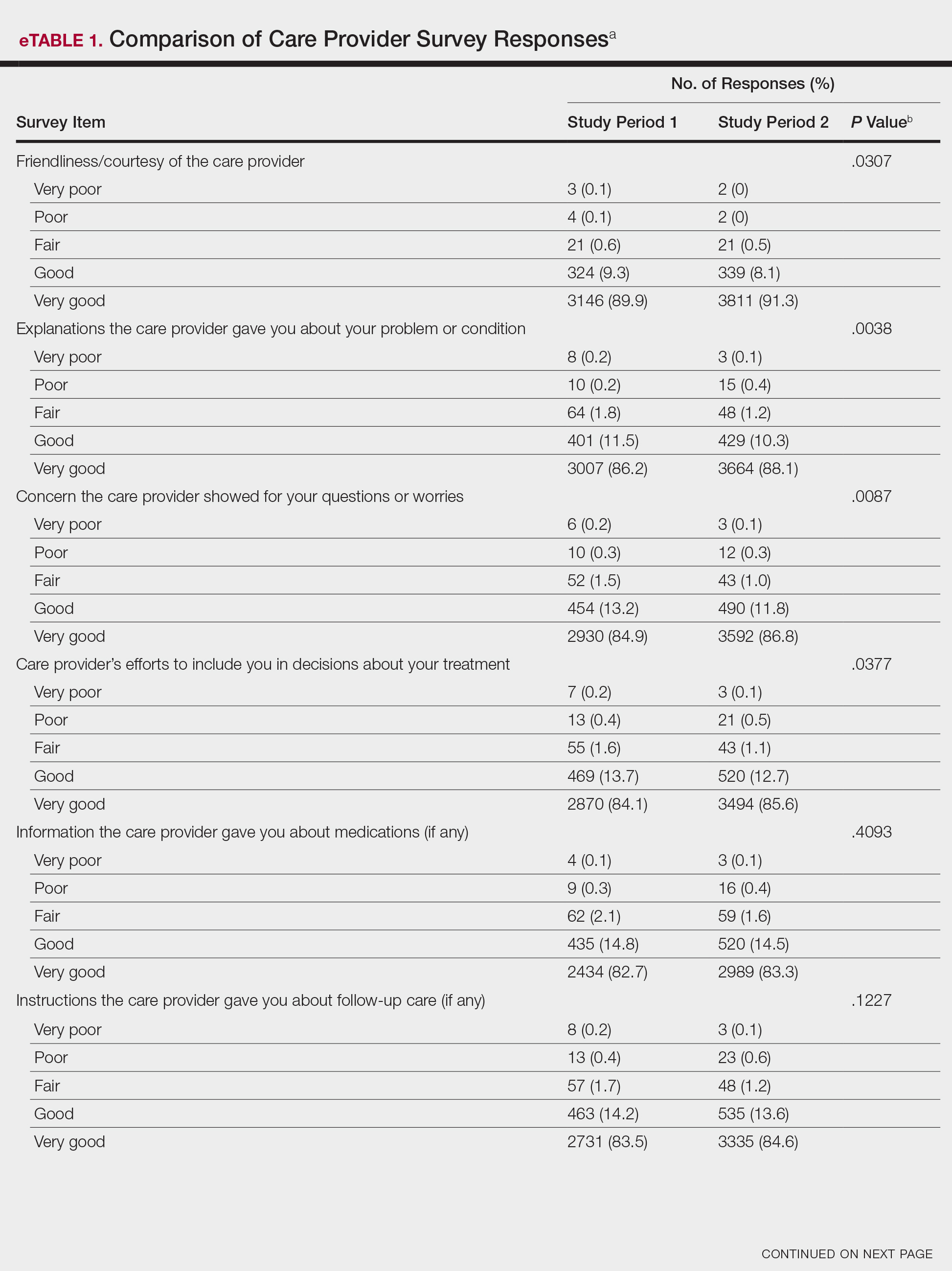

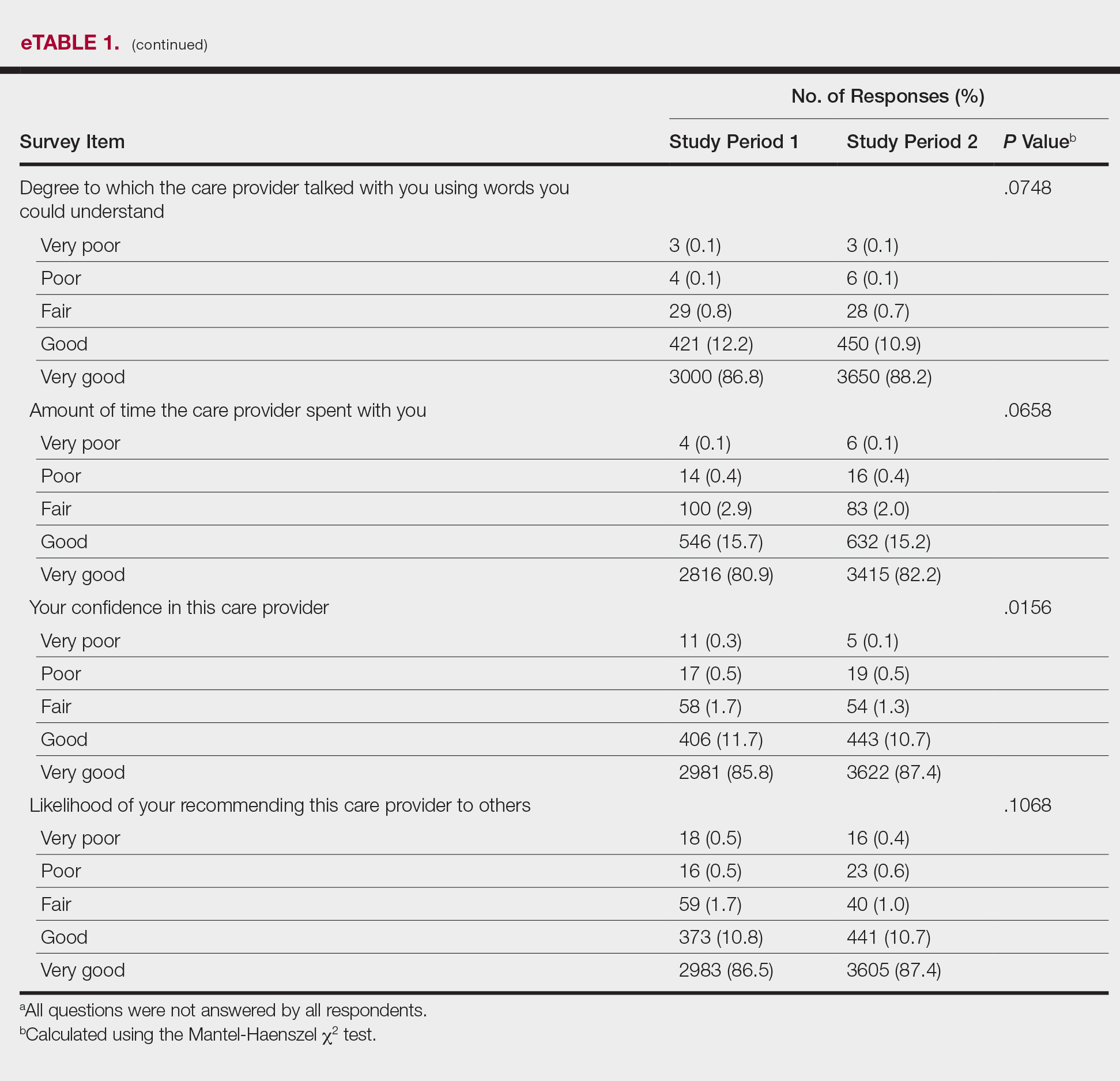

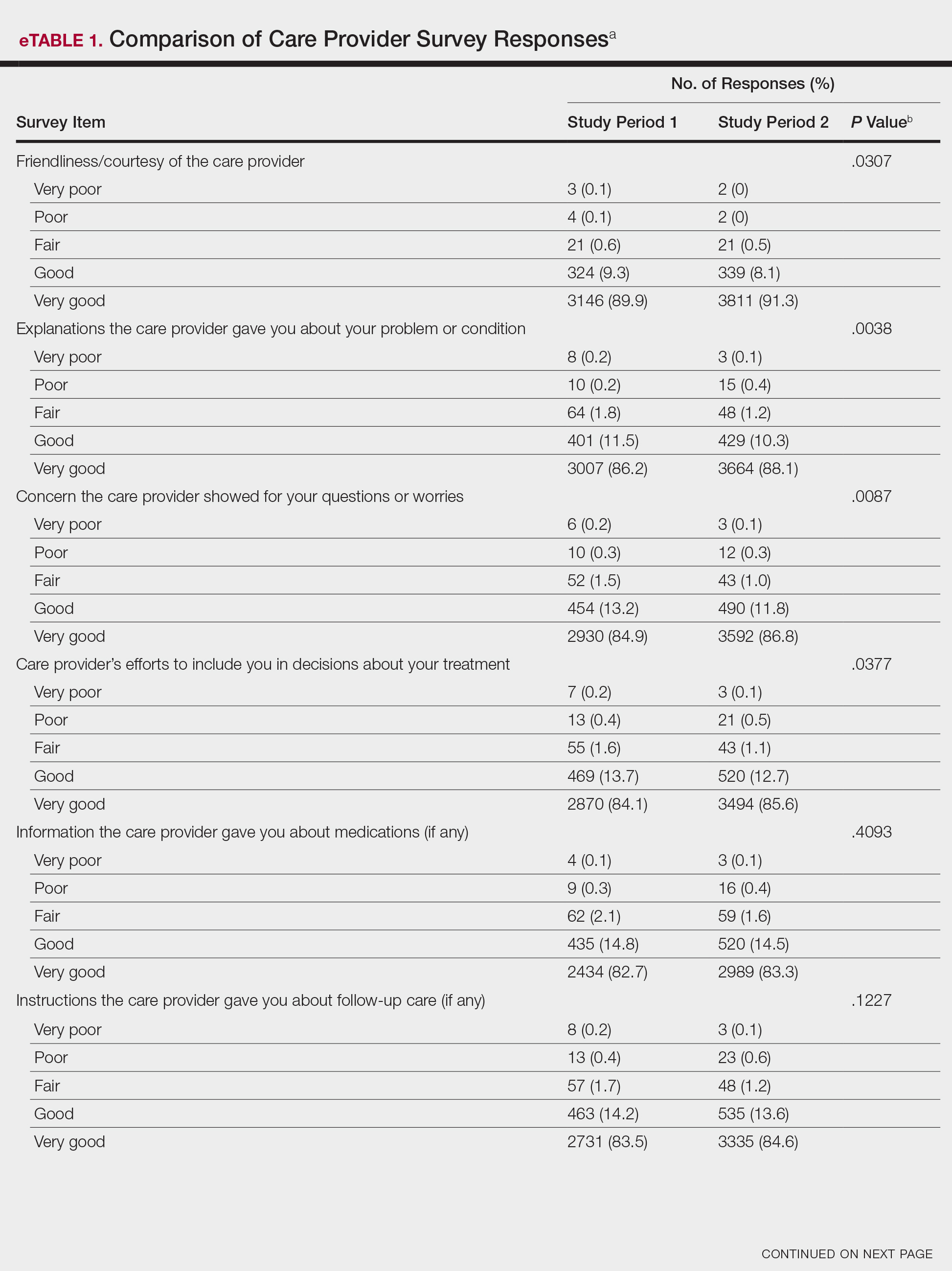

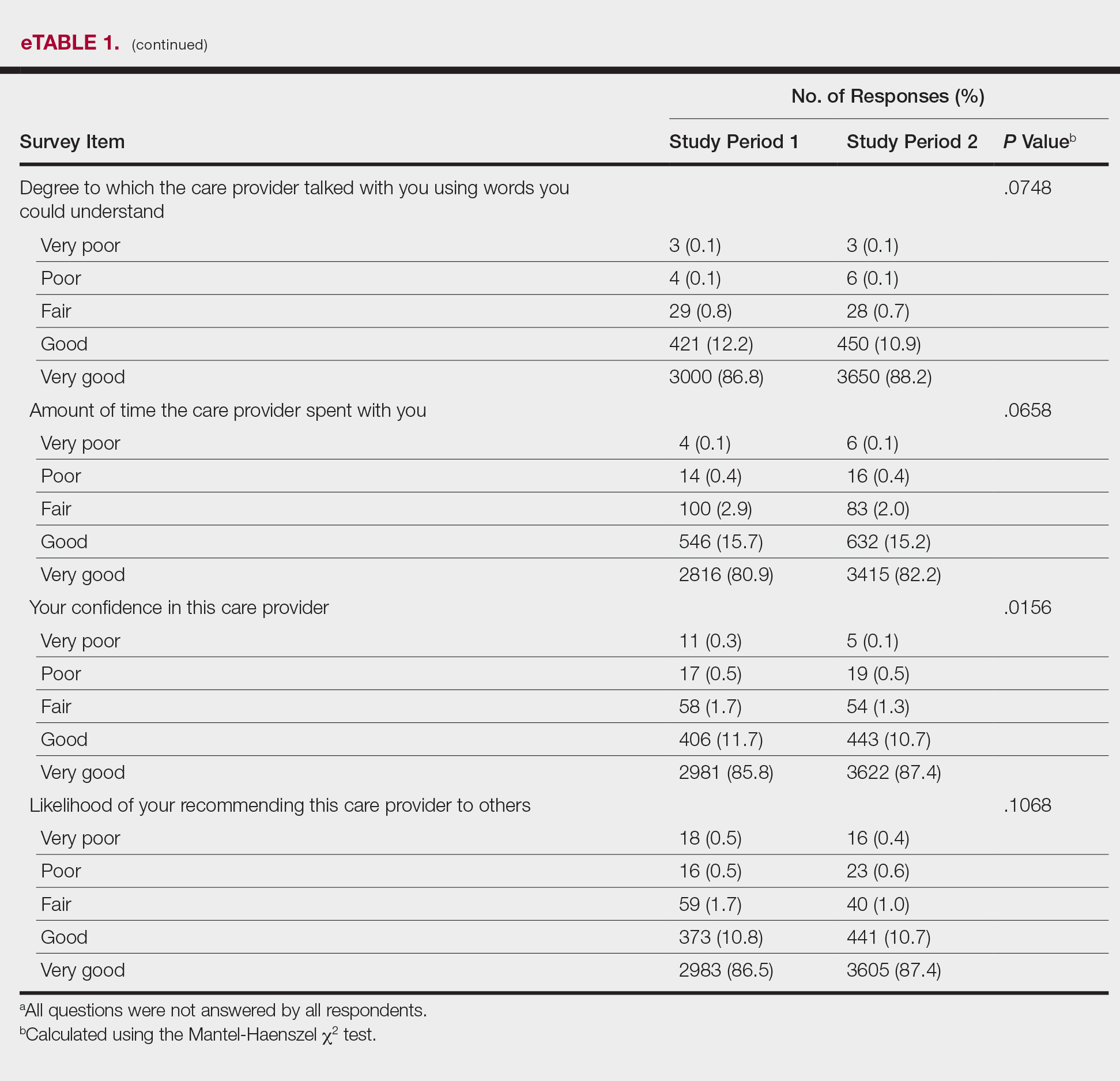

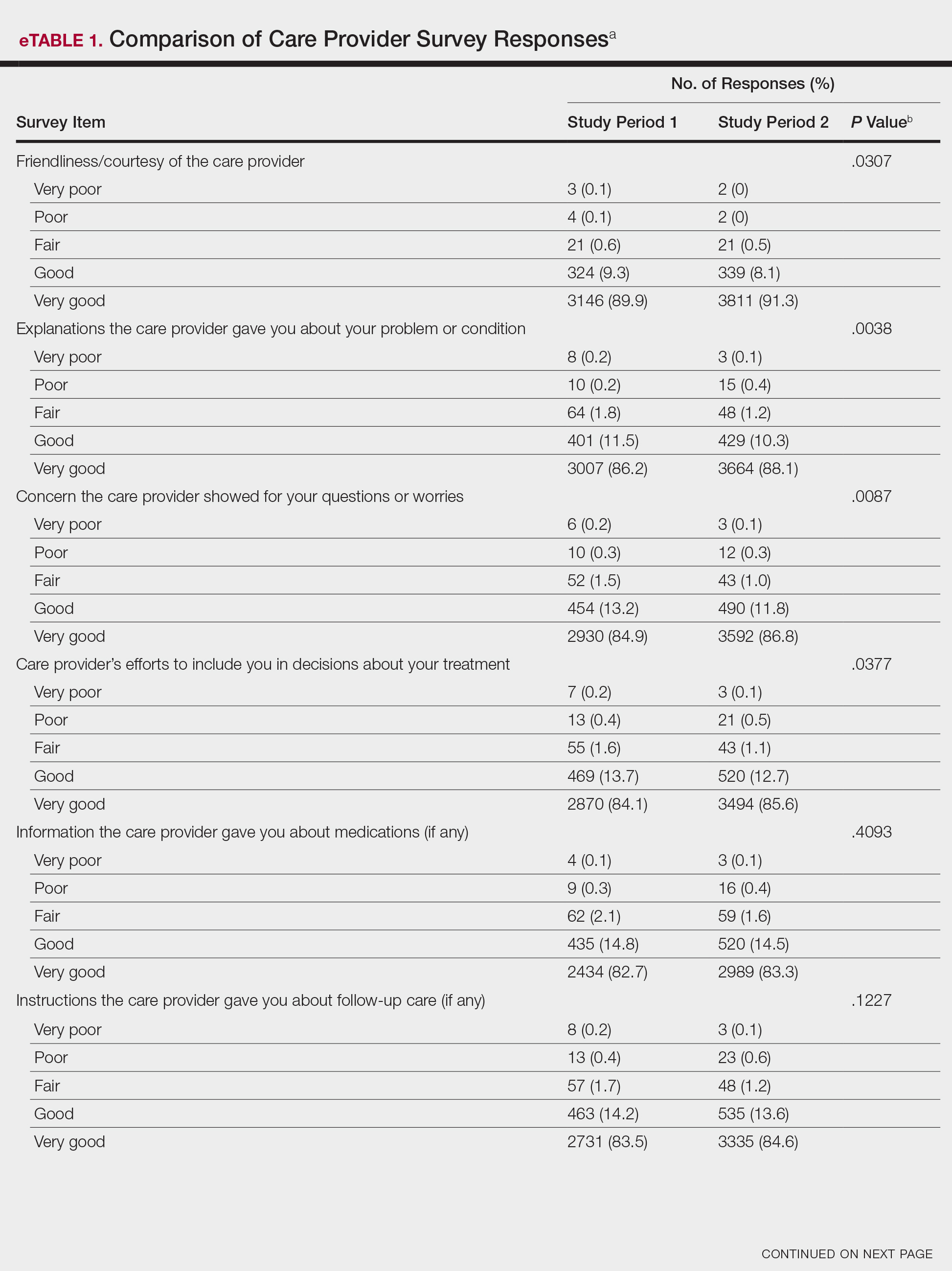

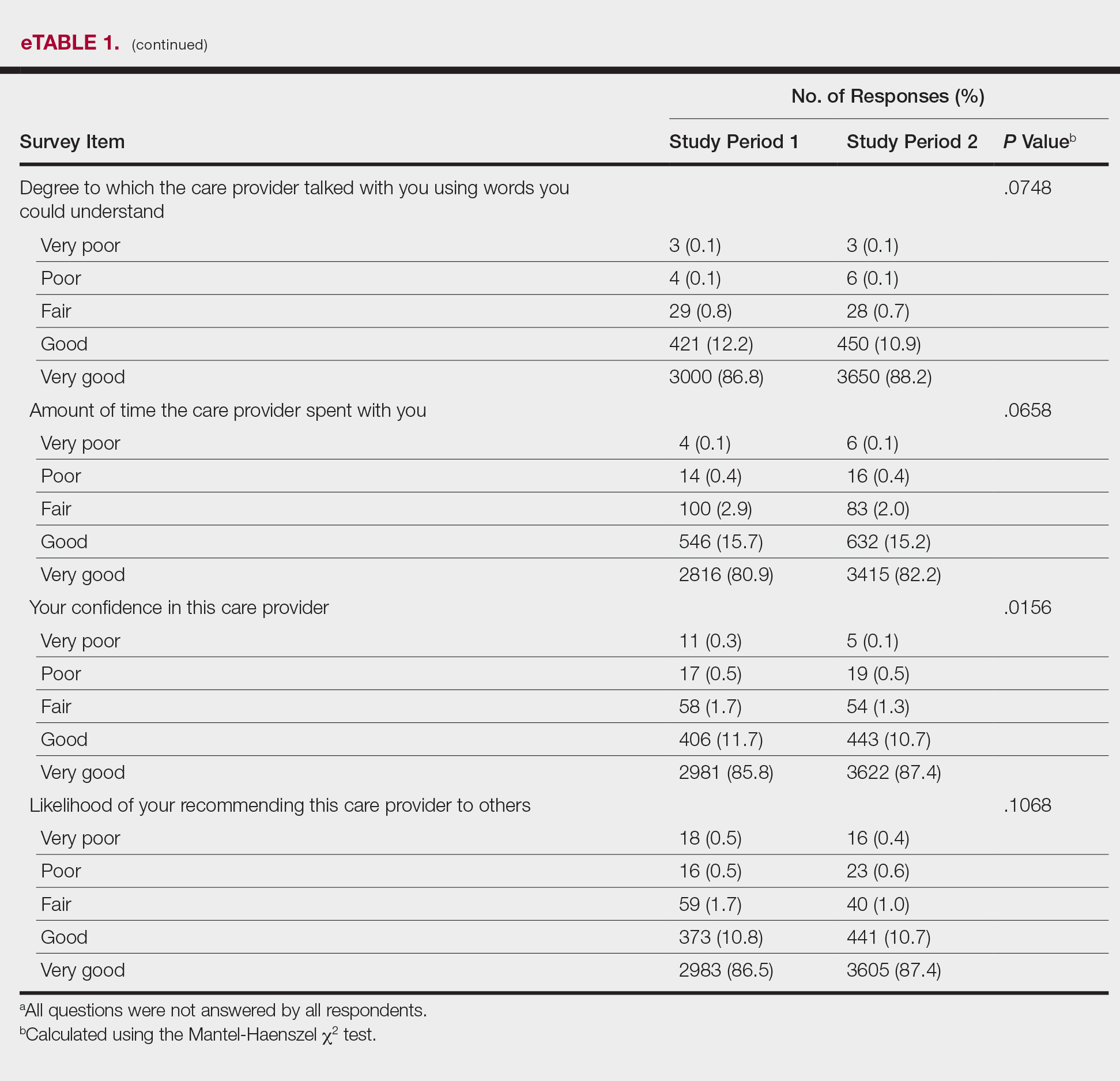

Analysis of the overall distribution of possible responses for each survey item showed significant differences between study periods 1 and 2 for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0307), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0038), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0087), care provider’s efforts to include the patient in decisions about treatment (P=.0377), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0156). These survey items trended toward more positive responses in study period 2. The full results are provided in eTable 1.

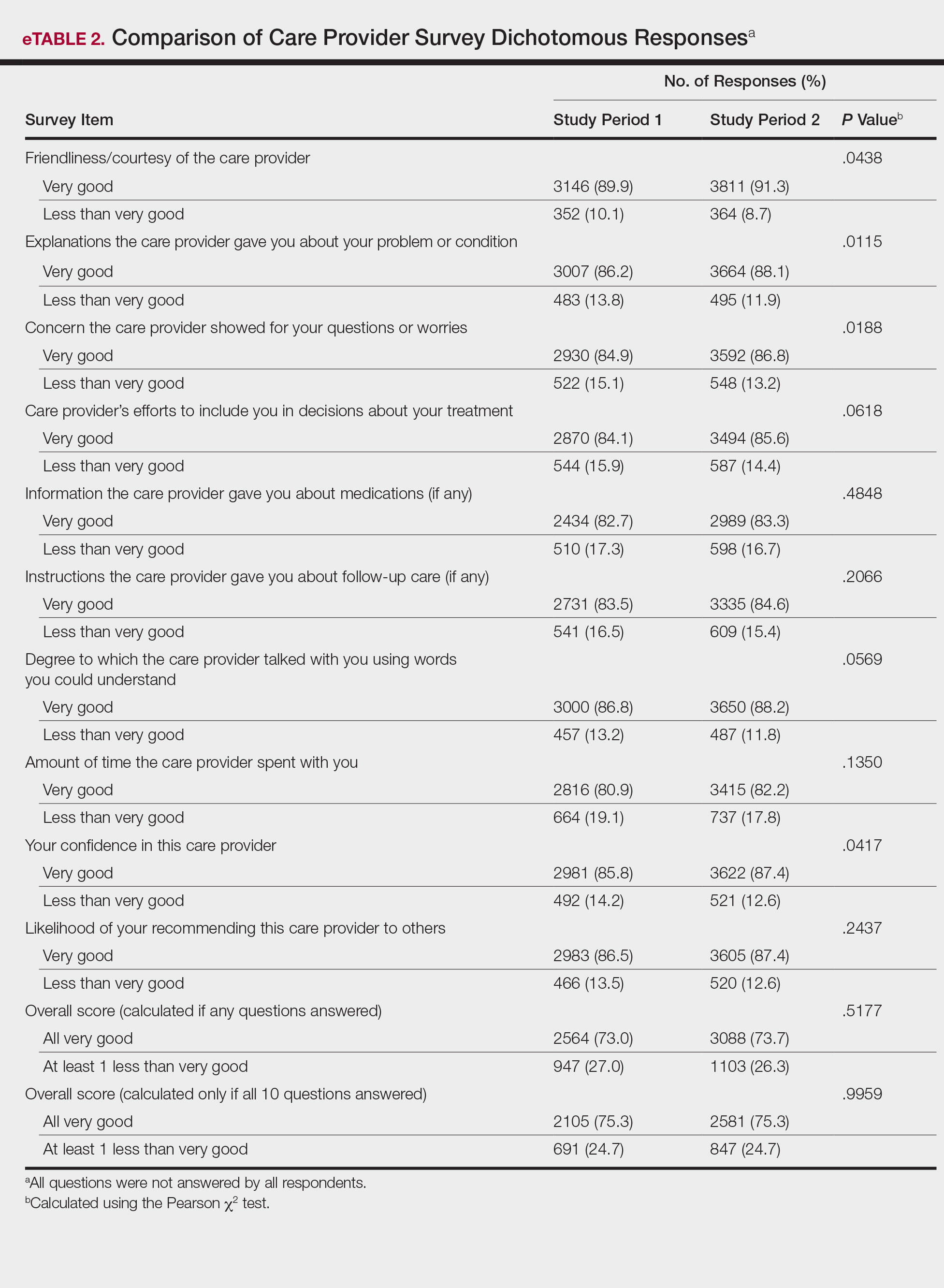

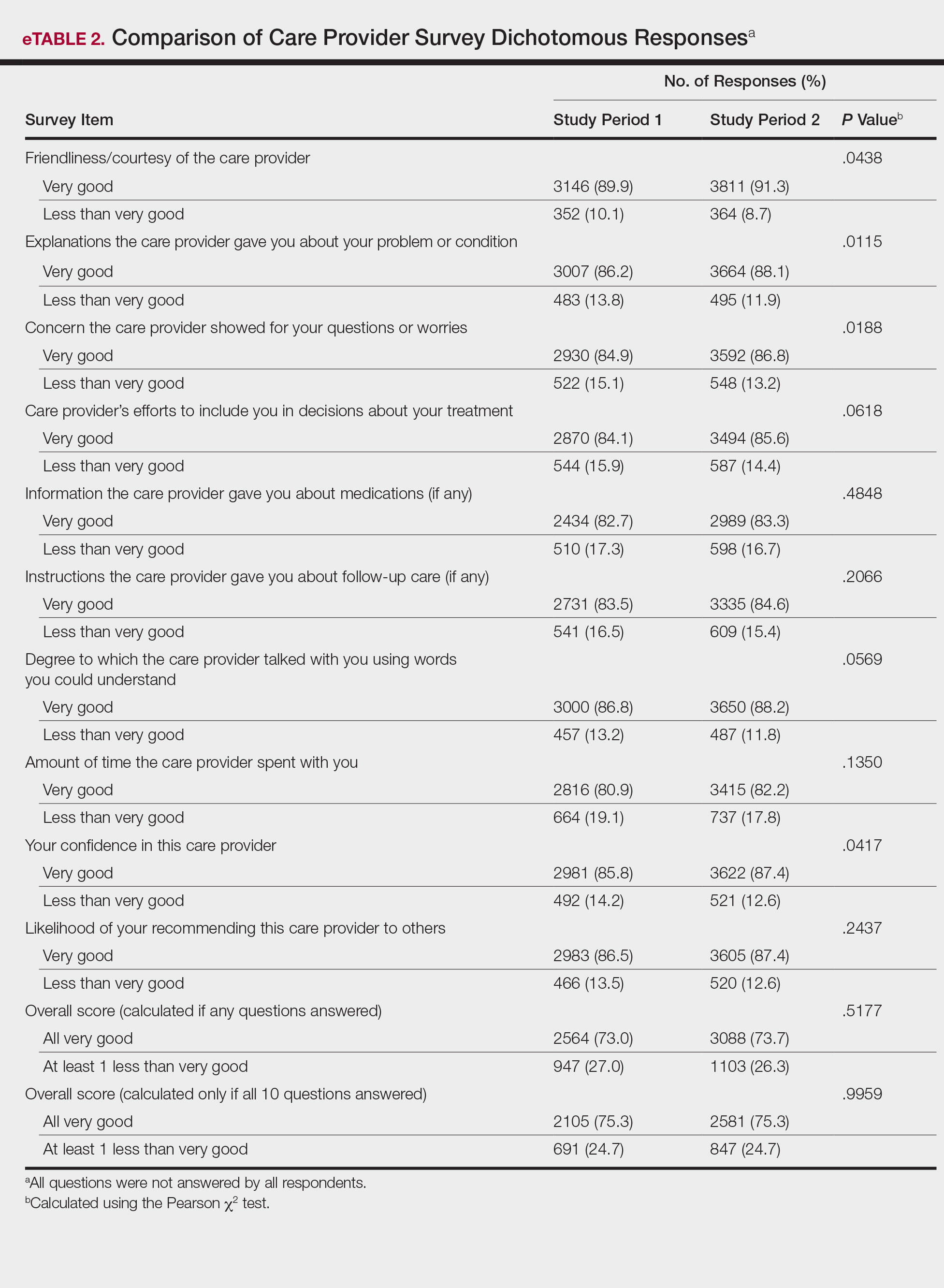

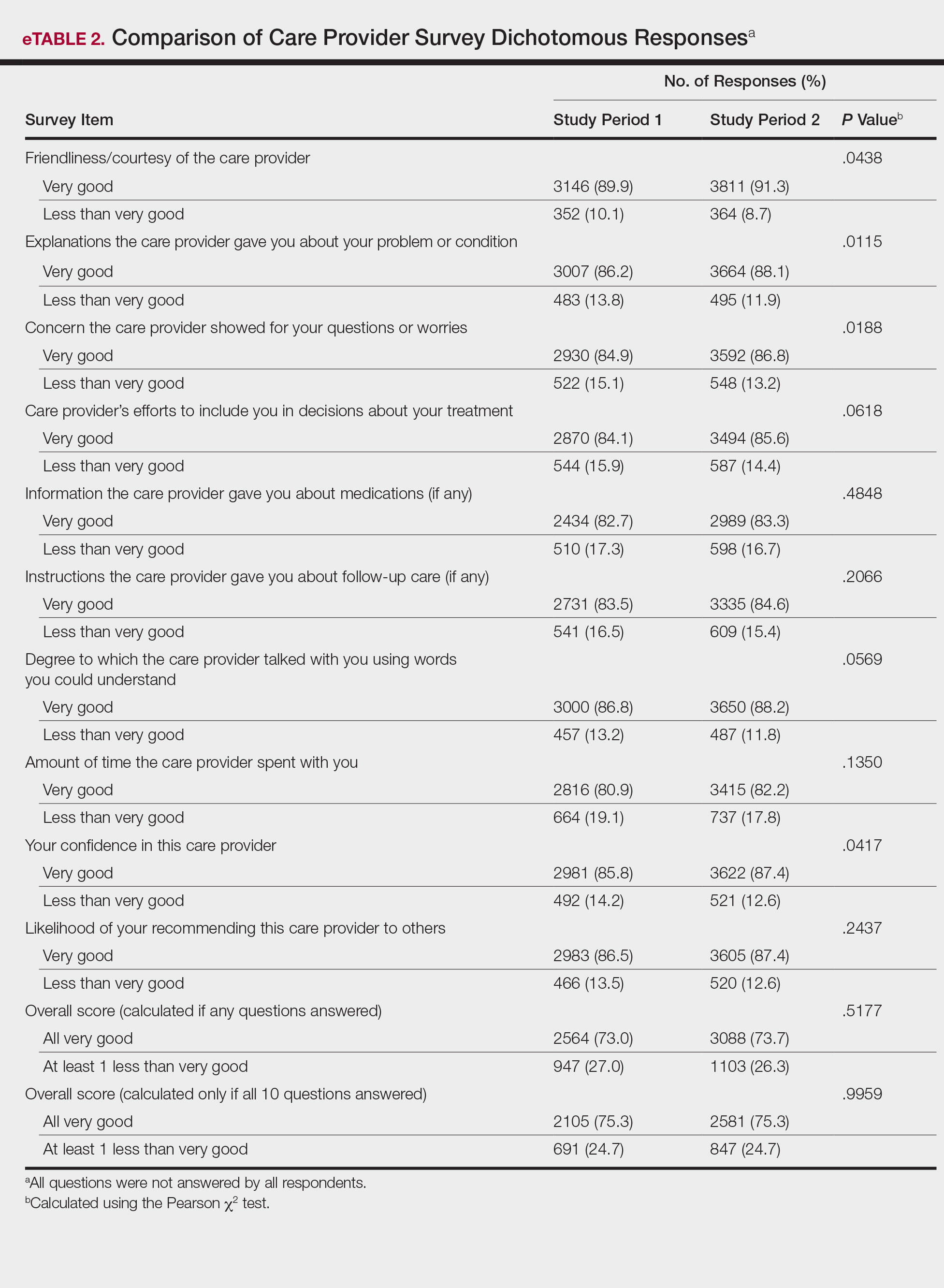

The analysis that looked at responses as binary (very good vs less than very good) showed a greater proportion of very good responses for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0438), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0115), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0188), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0417). The full results are provided in eTable 2.

There were no significant differences in the overall satisfaction scores between the first and second study periods. The differences were statistically significant when the overall score was calculated if any questions were answered (P=.5177) and when the overall score was calculated if all 10 questions were answered (P=.9959). For patients who responded to all survey items, 75.3% selected all very good responses for both the first and second study periods.

Review of the surveys for comments from both study periods revealed only a single patient comment pertaining to attire. The comment, which was submitted during study period 2, was considered positive, referring to the fitted scrubs as neat and professional. No negative comments were found during either period.

Comment

In this study, we did not find that a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs had a measurable negative impact on patient satisfaction scores. Conversely, we found a small but statistically significant improvement on several survey items after the change to fitted scrubs. The data suggest that changing from formal attire to fitted scrubs in an outpatient dermatology clinic had little impact on overall patient satisfaction. Only 1 positive comment and no negative comments were received regarding providers wearing fitted scrubs.

A prior study in an outpatient gynecology/obstetrics clinic showed similar results.6 In that study, providers were randomly assigned to business attire, casual attire, or scrubs. A 10-question patient satisfaction survey was designed that specifically avoided asking about provider attire to reduce any bias. The study found that over a 3-month period, attire had no influence on patient satisfaction.6

Our data suggest that factors beyond provider attire have the greatest influence on patient satisfaction scores. Patient satisfaction is likely driven by other factors such as provider communication skills, concern for patient well-being, ability to empathize, and timeliness. Given the biologic plausibility of increased infection rate from contaminated provider attire, we feel that comfortable, washable, fitted scrubs provide a sanitary and acceptable alternative to more traditional formal provider attire in the office setting. Bearman et al1 suggest consideration of a bare-below-the-elbows policy (with or without scrubs) for inpatient services and lab coats (if worn per facility policy), and other articles of clothing should be laundered frequently or if visibly soiled. We feel these policies also can be applied to outpatient dermatology clinics, as long as the rationale is well communicated to all parties.

Several items on the patient satisfaction survey were statistically improved during the second study period; however, it is impossible to determine if provider attire was an important factor in this change. Improvement in satisfaction scores could be attributed to ongoing departmental and institutional emphasis on patient care and servic

Anecdotally, most providers in our department were enthusiastic and supportive of the change to fitted scrubs. It is possible that provider happiness is reflected in improved patient satisfaction scores. Provider satisfaction has been shown to correlate with patient satisfaction.7

Limitations include possible other unmeasured variables that had a more substantial impact on patient satisfaction survey results. We also recognize that the survey used in this study contained no questions that directly asked patients about their satisfaction with provider attire; however, bias or any preconception patients may have had regarding attire may have been avoided in the process. We also were not able to separate patient surveys based on age or other demographics. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other settings where patient perceptions may be different from those of central Pennsylvania.

Conclusion

Transitioning from formal provider attire to fitted scrubs did not have a strong impact on overall patient satisfaction scores in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Providers and institutions should consider this information when developing dress code policies.

- Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S, et al. Expert guidance: healthcare personnel attire in non-operating room settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:107-121.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Maruani A, Léger J, Giraudeau B, et al. Effect of physician dress style on patient confidence. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E333-E337.

- Guadagnino C. Patient satisfaction critical to hospital value-based purchasing program. The Hospitalist. Published October 2012. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/article/patient-satisfaction-critical-to-hospital-value-based-purchasing-program/. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, et al. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:201-203.

- Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, et al. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:122-128.

- Fischer RL, Hansen CE, Hunter RL, et al. Does physician attire influence patient satisfaction in an outpatient obstetrics and gynecology setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:186.e1-186.e5.

Provider attire has come under scrutiny in the more recent medical literature. Epidemiologic data have shown that lab coats, ties, and other articles of clothing are frequently contaminated with disease-causing pathogens including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus , vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Acinetobacter species, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomona s species, and Clostridium difficile.1 Clothing may serve as a vector for spread of these bacteria and may contribute to hospital-acquired infections, increased cost of care, and patient morbidity. Prior to February 2015, the dermatology service line at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania, had followed a formal dress code that included white lab coats (white coats) along with long-sleeve shirts and ties/bowties for male providers and blouses, skirts, dress pants, and dresses for female providers. After a review of the recent literature on contamination rates of provider attire,2 we transitioned away from formal attire to adopt fitted, embroidered, black or navy blue scrubs to be worn in the clinic (Figure). Fitted scrubs differ from traditional unisex operating room scrubs, conferring a more professional appearance.

Limited research has shown that dermatology patients may have a slight preference for formal provider attire.2,3 In these studies, patients were shown photographs of providers in various dress (ie, professional attire, business attire, casual attire, scrubs). Patients preferred or had more confidence in the photograph of the provider in professional attire2,3; however, it is unclear if dermatology provider attire has any measurable effect on overall patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction relies on a myriad of factors, including both spoken and unspoken communication skills. Patient satisfaction has become an integral part of health care, and with an emphasis on value-based care, it will likely be one determining factor in how providers are reimbursed for their services.4,5 In this study, we investigated if a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs influenced patient satisfaction using a common third-party patient satisfaction survey.

Methods

Patient Satisfaction Survey

We conducted a retrospective cohort study analyzing 10 questions from the care provider section of the Press Ganey third-party patient satisfaction survey regarding providers in our dermatology service line. Only providers with at least 12 months of survey data before (study period 1) and after (study period 2) the change in attire were included in the study. Mohs surgeons were excluded, as they already wore fitted scrubs in the clinic. Residents also were excluded, as they are rapidly developing their patient communication skills and may have a notable change in patient satisfaction over a 2-year period.

The survey data were collected, and provider names were removed and replaced with alphanumeric codes to protect anonymity while still allowing individual provider analysis. Aggregate patient comments from surveys before and after the change in attire were digitally searched using the terms scrub, coat, white, attire, and clothing for pertinent positive or negative comments.

Outcomes

We compared individual and aggregate satisfaction scores for our providers during the 12-month periods before and after the adoption of fitted scrubs. The primary outcome was statistically significant change in patient satisfaction scores before and after the institution of fitted scrubs. Secondary outcomes included summation of patient comments, both positive and negative, regarding provider attire, as recorded on satisfaction surveys.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survey scores and scores on individual survey items were summarized using mean (SD), median and interquartile range, or frequency counts and percentage, as appropriate. The overall satisfaction score and responses to individual survey items were compared using Mantel-Haenszel or Pearson χ2 tests, as appropriate.

Assuming an equal number of surveys would be completed during study periods 1 and 2, an average (SD) satisfaction score of 95.4 (15), we calculated that as many as 2136 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −1.9 and 1.9 (a 1% difference). As few as 352 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −4.7 and 4.7 (a 5% difference). Sample size calculations assume 80% power and a significance level of 0.05. Comparison of responses for study periods 1 and 2 were made using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test.

Because more than 80% of respondents selected very good for each question, the responses also were treated as dichotomous variables with a category for very good and a category for responses that were lower than very good (ie, good, fair, poor, very poor). Responses of very good versus less than very good were compared for the study periods 1 and 2 using the Pearson χ2 test.

Two versions of an overall score were analyzed. The first version was for patients who responded to at least 1 of 10 survey items. If responses to all the items were very good, the patient was assigned to the category of all very good. If a patient answered any of the questions with a response less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. The second version was for patients who responded to all 10 survey items. If all 10 responses were very good, the patient was assigned to a category of all very good. If any of the 10 responses were less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. Differences between study periods for both score versions were tested using the Pearson χ2 test.

Results

Data for 22 providers in the dermatology service line—13 staff dermatologists, 6 physician assistants, 1 nurse practitioner, and 2 podiatrists—were included in the study, with a total of 7702 patient satisfaction surveys completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2016: 3511 were completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015 (study period 1), and 4191 were completed between February 1, 2015, and January 31, 2016 (study period 2).

Analysis of the overall distribution of possible responses for each survey item showed significant differences between study periods 1 and 2 for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0307), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0038), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0087), care provider’s efforts to include the patient in decisions about treatment (P=.0377), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0156). These survey items trended toward more positive responses in study period 2. The full results are provided in eTable 1.

The analysis that looked at responses as binary (very good vs less than very good) showed a greater proportion of very good responses for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0438), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0115), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0188), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0417). The full results are provided in eTable 2.

There were no significant differences in the overall satisfaction scores between the first and second study periods. The differences were statistically significant when the overall score was calculated if any questions were answered (P=.5177) and when the overall score was calculated if all 10 questions were answered (P=.9959). For patients who responded to all survey items, 75.3% selected all very good responses for both the first and second study periods.

Review of the surveys for comments from both study periods revealed only a single patient comment pertaining to attire. The comment, which was submitted during study period 2, was considered positive, referring to the fitted scrubs as neat and professional. No negative comments were found during either period.

Comment

In this study, we did not find that a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs had a measurable negative impact on patient satisfaction scores. Conversely, we found a small but statistically significant improvement on several survey items after the change to fitted scrubs. The data suggest that changing from formal attire to fitted scrubs in an outpatient dermatology clinic had little impact on overall patient satisfaction. Only 1 positive comment and no negative comments were received regarding providers wearing fitted scrubs.

A prior study in an outpatient gynecology/obstetrics clinic showed similar results.6 In that study, providers were randomly assigned to business attire, casual attire, or scrubs. A 10-question patient satisfaction survey was designed that specifically avoided asking about provider attire to reduce any bias. The study found that over a 3-month period, attire had no influence on patient satisfaction.6

Our data suggest that factors beyond provider attire have the greatest influence on patient satisfaction scores. Patient satisfaction is likely driven by other factors such as provider communication skills, concern for patient well-being, ability to empathize, and timeliness. Given the biologic plausibility of increased infection rate from contaminated provider attire, we feel that comfortable, washable, fitted scrubs provide a sanitary and acceptable alternative to more traditional formal provider attire in the office setting. Bearman et al1 suggest consideration of a bare-below-the-elbows policy (with or without scrubs) for inpatient services and lab coats (if worn per facility policy), and other articles of clothing should be laundered frequently or if visibly soiled. We feel these policies also can be applied to outpatient dermatology clinics, as long as the rationale is well communicated to all parties.

Several items on the patient satisfaction survey were statistically improved during the second study period; however, it is impossible to determine if provider attire was an important factor in this change. Improvement in satisfaction scores could be attributed to ongoing departmental and institutional emphasis on patient care and servic

Anecdotally, most providers in our department were enthusiastic and supportive of the change to fitted scrubs. It is possible that provider happiness is reflected in improved patient satisfaction scores. Provider satisfaction has been shown to correlate with patient satisfaction.7

Limitations include possible other unmeasured variables that had a more substantial impact on patient satisfaction survey results. We also recognize that the survey used in this study contained no questions that directly asked patients about their satisfaction with provider attire; however, bias or any preconception patients may have had regarding attire may have been avoided in the process. We also were not able to separate patient surveys based on age or other demographics. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other settings where patient perceptions may be different from those of central Pennsylvania.

Conclusion

Transitioning from formal provider attire to fitted scrubs did not have a strong impact on overall patient satisfaction scores in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Providers and institutions should consider this information when developing dress code policies.

Provider attire has come under scrutiny in the more recent medical literature. Epidemiologic data have shown that lab coats, ties, and other articles of clothing are frequently contaminated with disease-causing pathogens including methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus , vancomycin-resistant enterococci, Acinetobacter species, Enterobacteriaceae, Pseudomona s species, and Clostridium difficile.1 Clothing may serve as a vector for spread of these bacteria and may contribute to hospital-acquired infections, increased cost of care, and patient morbidity. Prior to February 2015, the dermatology service line at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, Pennsylvania, had followed a formal dress code that included white lab coats (white coats) along with long-sleeve shirts and ties/bowties for male providers and blouses, skirts, dress pants, and dresses for female providers. After a review of the recent literature on contamination rates of provider attire,2 we transitioned away from formal attire to adopt fitted, embroidered, black or navy blue scrubs to be worn in the clinic (Figure). Fitted scrubs differ from traditional unisex operating room scrubs, conferring a more professional appearance.

Limited research has shown that dermatology patients may have a slight preference for formal provider attire.2,3 In these studies, patients were shown photographs of providers in various dress (ie, professional attire, business attire, casual attire, scrubs). Patients preferred or had more confidence in the photograph of the provider in professional attire2,3; however, it is unclear if dermatology provider attire has any measurable effect on overall patient satisfaction. Patient satisfaction relies on a myriad of factors, including both spoken and unspoken communication skills. Patient satisfaction has become an integral part of health care, and with an emphasis on value-based care, it will likely be one determining factor in how providers are reimbursed for their services.4,5 In this study, we investigated if a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs influenced patient satisfaction using a common third-party patient satisfaction survey.

Methods

Patient Satisfaction Survey

We conducted a retrospective cohort study analyzing 10 questions from the care provider section of the Press Ganey third-party patient satisfaction survey regarding providers in our dermatology service line. Only providers with at least 12 months of survey data before (study period 1) and after (study period 2) the change in attire were included in the study. Mohs surgeons were excluded, as they already wore fitted scrubs in the clinic. Residents also were excluded, as they are rapidly developing their patient communication skills and may have a notable change in patient satisfaction over a 2-year period.

The survey data were collected, and provider names were removed and replaced with alphanumeric codes to protect anonymity while still allowing individual provider analysis. Aggregate patient comments from surveys before and after the change in attire were digitally searched using the terms scrub, coat, white, attire, and clothing for pertinent positive or negative comments.

Outcomes

We compared individual and aggregate satisfaction scores for our providers during the 12-month periods before and after the adoption of fitted scrubs. The primary outcome was statistically significant change in patient satisfaction scores before and after the institution of fitted scrubs. Secondary outcomes included summation of patient comments, both positive and negative, regarding provider attire, as recorded on satisfaction surveys.

Statistical Analysis

Overall survey scores and scores on individual survey items were summarized using mean (SD), median and interquartile range, or frequency counts and percentage, as appropriate. The overall satisfaction score and responses to individual survey items were compared using Mantel-Haenszel or Pearson χ2 tests, as appropriate.

Assuming an equal number of surveys would be completed during study periods 1 and 2, an average (SD) satisfaction score of 95.4 (15), we calculated that as many as 2136 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −1.9 and 1.9 (a 1% difference). As few as 352 surveys would be needed to conclude satisfaction scores are the same for equivalence limits of −4.7 and 4.7 (a 5% difference). Sample size calculations assume 80% power and a significance level of 0.05. Comparison of responses for study periods 1 and 2 were made using the Mantel-Haenszel χ2 test.

Because more than 80% of respondents selected very good for each question, the responses also were treated as dichotomous variables with a category for very good and a category for responses that were lower than very good (ie, good, fair, poor, very poor). Responses of very good versus less than very good were compared for the study periods 1 and 2 using the Pearson χ2 test.

Two versions of an overall score were analyzed. The first version was for patients who responded to at least 1 of 10 survey items. If responses to all the items were very good, the patient was assigned to the category of all very good. If a patient answered any of the questions with a response less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. The second version was for patients who responded to all 10 survey items. If all 10 responses were very good, the patient was assigned to a category of all very good. If any of the 10 responses were less than very good, he/she was categorized as at least 1 less than very good. Differences between study periods for both score versions were tested using the Pearson χ2 test.

Results

Data for 22 providers in the dermatology service line—13 staff dermatologists, 6 physician assistants, 1 nurse practitioner, and 2 podiatrists—were included in the study, with a total of 7702 patient satisfaction surveys completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2016: 3511 were completed between February 1, 2014, and January 31, 2015 (study period 1), and 4191 were completed between February 1, 2015, and January 31, 2016 (study period 2).

Analysis of the overall distribution of possible responses for each survey item showed significant differences between study periods 1 and 2 for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0307), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0038), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0087), care provider’s efforts to include the patient in decisions about treatment (P=.0377), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0156). These survey items trended toward more positive responses in study period 2. The full results are provided in eTable 1.

The analysis that looked at responses as binary (very good vs less than very good) showed a greater proportion of very good responses for friendliness/courtesy of the care provider (P=.0438), explanations the care provider gave about the problem or condition (P=.0115), concern the care provider showed for questions or worries (P=.0188), and patient confidence in the care provider (P=.0417). The full results are provided in eTable 2.

There were no significant differences in the overall satisfaction scores between the first and second study periods. The differences were statistically significant when the overall score was calculated if any questions were answered (P=.5177) and when the overall score was calculated if all 10 questions were answered (P=.9959). For patients who responded to all survey items, 75.3% selected all very good responses for both the first and second study periods.

Review of the surveys for comments from both study periods revealed only a single patient comment pertaining to attire. The comment, which was submitted during study period 2, was considered positive, referring to the fitted scrubs as neat and professional. No negative comments were found during either period.

Comment

In this study, we did not find that a change from formal attire to fitted scrubs had a measurable negative impact on patient satisfaction scores. Conversely, we found a small but statistically significant improvement on several survey items after the change to fitted scrubs. The data suggest that changing from formal attire to fitted scrubs in an outpatient dermatology clinic had little impact on overall patient satisfaction. Only 1 positive comment and no negative comments were received regarding providers wearing fitted scrubs.

A prior study in an outpatient gynecology/obstetrics clinic showed similar results.6 In that study, providers were randomly assigned to business attire, casual attire, or scrubs. A 10-question patient satisfaction survey was designed that specifically avoided asking about provider attire to reduce any bias. The study found that over a 3-month period, attire had no influence on patient satisfaction.6

Our data suggest that factors beyond provider attire have the greatest influence on patient satisfaction scores. Patient satisfaction is likely driven by other factors such as provider communication skills, concern for patient well-being, ability to empathize, and timeliness. Given the biologic plausibility of increased infection rate from contaminated provider attire, we feel that comfortable, washable, fitted scrubs provide a sanitary and acceptable alternative to more traditional formal provider attire in the office setting. Bearman et al1 suggest consideration of a bare-below-the-elbows policy (with or without scrubs) for inpatient services and lab coats (if worn per facility policy), and other articles of clothing should be laundered frequently or if visibly soiled. We feel these policies also can be applied to outpatient dermatology clinics, as long as the rationale is well communicated to all parties.

Several items on the patient satisfaction survey were statistically improved during the second study period; however, it is impossible to determine if provider attire was an important factor in this change. Improvement in satisfaction scores could be attributed to ongoing departmental and institutional emphasis on patient care and servic

Anecdotally, most providers in our department were enthusiastic and supportive of the change to fitted scrubs. It is possible that provider happiness is reflected in improved patient satisfaction scores. Provider satisfaction has been shown to correlate with patient satisfaction.7

Limitations include possible other unmeasured variables that had a more substantial impact on patient satisfaction survey results. We also recognize that the survey used in this study contained no questions that directly asked patients about their satisfaction with provider attire; however, bias or any preconception patients may have had regarding attire may have been avoided in the process. We also were not able to separate patient surveys based on age or other demographics. Finally, our results may not be generalizable to other settings where patient perceptions may be different from those of central Pennsylvania.

Conclusion

Transitioning from formal provider attire to fitted scrubs did not have a strong impact on overall patient satisfaction scores in an outpatient dermatology clinic. Providers and institutions should consider this information when developing dress code policies.

- Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S, et al. Expert guidance: healthcare personnel attire in non-operating room settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:107-121.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Maruani A, Léger J, Giraudeau B, et al. Effect of physician dress style on patient confidence. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E333-E337.

- Guadagnino C. Patient satisfaction critical to hospital value-based purchasing program. The Hospitalist. Published October 2012. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/article/patient-satisfaction-critical-to-hospital-value-based-purchasing-program/. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, et al. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:201-203.

- Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, et al. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:122-128.

- Fischer RL, Hansen CE, Hunter RL, et al. Does physician attire influence patient satisfaction in an outpatient obstetrics and gynecology setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:186.e1-186.e5.

- Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S, et al. Expert guidance: healthcare personnel attire in non-operating room settings. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35:107-121.

- Fox JD, Prado G, Baquerizo Nole KL, et al. Patient preference in dermatologist attire in the medical, surgical, and wound care settings. JAMA Dermatol. 2016;152:913-919.

- Maruani A, Léger J, Giraudeau B, et al. Effect of physician dress style on patient confidence. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013;27:E333-E337.

- Guadagnino C. Patient satisfaction critical to hospital value-based purchasing program. The Hospitalist. Published October 2012. http://www.the-hospitalist.org/article/patient-satisfaction-critical-to-hospital-value-based-purchasing-program/. Accessed June 23, 2018.

- Manary MP, Boulding W, Staelin R, et al. The patient experience and health outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:201-203.

- Haas JS, Cook EF, Puopolo AL, et al. Is the professional satisfaction of general internists associated with patient satisfaction? J Gen Intern Med. 2000;15:122-128.

- Fischer RL, Hansen CE, Hunter RL, et al. Does physician attire influence patient satisfaction in an outpatient obstetrics and gynecology setting? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;196:186.e1-186.e5.

Practice Points

- Provider attire is known to harbor disease-causing microorganisms, potentially serving as a vector and contributing to hospital-acquired infections.

- A change from formal provider attire, including white coats, to fitted scrubs had no measurable impact on patient satisfaction in an outpatient dermatology clinic.

- Patient satisfaction is most strongly linked to other provider characteristics, such as communication skills, concern for patient well-being, ability to empathize, and timeliness.