User login

Risk factors for dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) are not clearly defined. Prosthetic dislocation can result in poor patient satisfaction, worse functional outcomes, and return to the operating room.1-3 As a result, identification of modifiable risk factors for complications represents an important research initiative for shoulder surgeons.

There is a paucity of literature devoted to the study of dislocation after RTSA. Chalmers and colleagues4 found a 2.9% (11/385) incidence of early dislocation within 3 months after index surgery—an improvement over the 15.8% reported for early instability over the period 2004–2006.5 As prosthesis design has improved and surgeons have become more comfortable with the RTSA prosthesis, surgical indications have expanded,6,7 and dislocation rates appear to have decreased. Although the most common indication for RTSA continues to be cuff tear arthropathy (CTA),6 there has been increased use in rheumatoid arthritis8-10; proximal humerus fractures, especially in cases of poor bone quality and unreliable fixation of tuberosities11-13; and failed previous shoulder reconstruction.14,15 As RTSA is performed more often, limiting the complications will become more important for both patient care and economics.

We conducted a study to analyze dislocation rates at our institution and to identify both modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for dislocation after RTSA. By identifying risk factors for dislocation, we will be able to implement additional perioperative clinical measures to reduce the incidence of dislocation.

Materials and Methods

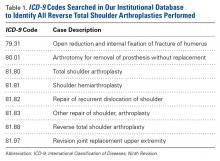

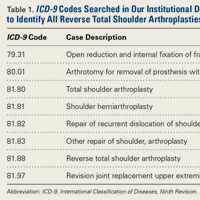

This retrospective study of dislocation after RTSA was conducted at the Rothman Institute of Orthopedics and Methodist Hospital (Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, Philadelphia, PA). After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for the study, we searched our institution’s electronic database of shoulder arthroplasties to identify all RTSAs performed at our 2 large-volume urban institutions between September 27, 2010 and December 31, 2013. For the record search, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes were used (Table 1).

The medical records of each patient were used to identify independent variables that could be associated with dislocation rate. Demographic variables included sex, age, and race. Preoperative clinical data included body mass index (BMI), etiology of shoulder disease leading to RTSA, individual comorbidities, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)16 modified to be used with ICD-9 codes.17 In addition, prior shoulder surgery history and arthroplasty type (primary or revision) were determined. Postoperative considerations were time to dislocation, mechanism of dislocation, and intervention(s) needed for dislocation. Although the institutional database did not include operative variables such as prosthesis type and surgical approach, all 6 surgeons in this study were using a standard deltopectoral approach in beach-chair position with a Grammont style prosthesis for RTSA cases.

Descriptive statistics for RTSA patients and the dislocation subpopulation were compiled. Bivariate analysis was used to evaluate which of the previously described variables influenced dislocation rates. Last, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate which factors were independent predictors of dislocation. We included demographic variables (age, sex, ethnicity), clinical variables (BMI, individual comorbidities, CCI), and surgical variables (primary vs revision, diagnosis at time of surgery). All statistical analyses were performed with Excel 2013 (Microsoft) and SPSS Statistics Version 20.0 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

From the database, we identified 487 patients who underwent 510 RTSAs during the study period. These surgeries were performed by 6 shoulder and elbow fellowship–trained surgeons. Of the 510 RTSAs, 393 (77.1%) were primary cases, and 117 (22.9%) were revision cases.

Of the 510 shoulders that underwent RTSA, 15 (2.9%; 14 patients) dislocated. Of these 15 cases, 5 were primary (1.3% of all primary cases) and 10 were revision (8.5% of all revision cases). Mean time from index surgery to diagnosis of dislocation was 58.2 days (range, 0-319 days). One dislocation occurred immediately after surgery, 2 after falls, 4 from patient-identified low-energy mechanisms of injury, and 8 without known inciting events. Nine dislocations (60%) did not have a subscapularis repair (7 were irreparable, 2 underwent subscapularis peel without repair), and the other 6 were repaired primarily (Table 2).

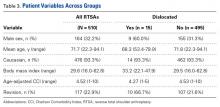

Male patients accounted for 32.2% of the study population but 60.0% of the dislocations (P = .019) (Table 3).

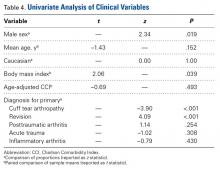

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed revision arthroplasty (OR = 7.515; P = .042) and increased BMI (OR = 1.09; P = .047) to be independent risk factors for dislocation after RTSA. Analysis also found a diagnosis of primary CTA to be independently associated with lower risk of dislocation after RTSA (OR = 0.025; P = .008). Last, the previously described risk factor of male sex was found not to be a significant independent risk factor, though it did trend positively (OR = 3.011; P = .071).

Discussion

With more RTSAs being performed, evaluation of their common complications becomes increasingly important.18 We found a 3.0% rate of dislocation after RTSA, which is consistent with the most recently reported incidence4 and falls within the previously described range of 0% to 8.6%.19-26 Of the clinical risk factors identified in this study, those previously described were prior surgery, subscapularis insufficiency, higher BMI, and male sex.4 However, our finding of lower risk of dislocation after RTSA for primary rotator cuff pathology was not previously described. Although Chalmers and colleagues4 did not report this lower risk, 3 (27.3%) of their 11 patients with dislocation had primary CTA, compared with 1 (6.7%) of 15 patients in the present study.4 Our literature review did not identify any studies that independently reported the dislocation rate in patients who underwent RTSA for rotator cuff failure.

The risk factors of subscapularis irreparability and revision surgery suggest the importance of the soft-tissue envelope and bony anatomy in dislocation prevention. Previous analyses have suggested implant malpositioning,27,28 poor subscapularis quality,29 and inadequate muscle tensioning5,30-32 as risk factors for RTSA. Patients with an irreparable subscapularis tendon have often had multiple surgeries with compromise to the muscle/soft-tissue envelope or bony anatomy of the shoulder. A biomechanical study by Gutiérrez and colleagues31 found the compressive forces of the soft tissue at the glenohumeral joint to be the most important contributor to stability in the RTSA prosthesis. In clinical studies, the role of the subscapularis in preventing instability after RTSA remains unclear. Edwards and colleagues29 prospectively compared dislocation rates in patients with reparable and irreparable subscapularis tendons during RTSA and found a higher rate of dislocation in the irreparable subscapularis group. Of note, patients in the irreparable subscapularis group also had more complex diagnoses, including proximal humeral nonunion, fixed glenohumeral dislocation, and failed prior arthroplasty. Clark and colleagues33 retrospectively analyzed subscapularis repair in 2 RTSA groups and found no appreciable effect on complication rate, dislocation events, range-of-motion gains, or pain relief.

Our finding that higher BMI is an independent risk factor was previously described.4 The association is unclear but could be related to implant positioning, difficulty in intraoperative assessment of muscle tensioning, or body habitus that may generate a lever arm for impingement and dislocation when the arm is in adduction. Last, our finding that male sex is a risk factor for dislocation approached significance, and this relationship was previously reported.4 This could be attributable to a higher rate of activity or of indolent infection in male patients.34,35Besides studying risk factors for dislocation after RTSA, we investigated treatment. None of our patients were treated successfully and definitively with closed reduction in the clinic. This finding diverges from findings in studies by Teusink and colleagues2 and Chalmers and colleagues,4who respectively reported 62% and 44% rates of success with closed reduction. Our cohort of 14 patients with 15 dislocations required a total of 17 trips to the operating room after dislocation. This significantly higher rate of return to the operating room suggests that dislocation after RTSA may be a more costly and morbid problem than has been previously described.

This study had several weaknesses. Despite its large consecutive series of patients, the study was retrospective, and several variables that would be documented and controlled in a prospective study could not be measured here. Specifically, neither preoperative physical examination nor patient-specific assessments of pain or function were consistently obtained. Similarly, postoperative patient-specific instruments of outcomes evaluation were not obtained consistently, so results of patients with dislocation could not be compared with those of a control group. In addition, preoperative and postoperative radiographs were not consistently present in our electronic medical records, so the influence of preoperative bony anatomy, intraoperative limb lengthening, and any implant malpositioning could not be determined. Furthermore, operative details, such as reparability of the subscapularis, were not fully available for the control group and could not be included in statistical analysis. In addition, that the known dislocation risk factor of male sex4 was identified here but was not significant in multivariate regression analysis suggests that this study may not have been adequately powered to identify a significant difference in dislocation rate between the sexes. Last, though our results suggested associations between the aforementioned variables and dislocation after RTSA, a truly causative relationship could not be confirmed with this study design or analysis. Therefore, our study findings are hypothesis-generating and may indicate a benefit to greater deltoid tensioning, use of retentive liners, or more conservative rehabilitation protocols for high-risk patients.

Conclusion

Dislocation after RTSA is an uncommon complication that often requires a return to the operating room. This study identified a modifiable risk factor (higher BMI) and 3 nonmodifiable risk factors (male sex, subscapularis insufficiency, revision surgery) for dislocation after RTSA. In contrast, patients who undergo RTSA for primary rotator cuff pathology are unlikely to dislocate after surgery. This low risk of dislocation after RTSA for primary cuff pathology was not previously described. Patients in the higher risk category may benefit from preoperative lifestyle modification, intraoperative techniques for increasing stability, and more conservative therapy after surgery. In addition, unlike previous investigations, this study did not find closed reduction in the clinic alone to be successful in definitively treating this patient population.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E444-E450. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Aldinger PR, Raiss P, Rickert M, Loew M. Complications in shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of 485 cases. Int Orthop. 2010;34(4):517-524.

2. Teusink MJ, Pappou IP, Schwartz DG, Cottrell BJ, Frankle MA. Results of closed management of acute dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(4):621-627.

3. Fink Barnes LA, Grantham WJ, Meadows MC, Bigliani LU, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Sports activity after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Orthop. 2015;44(2):68-72.

4. Chalmers PN, Rahman Z, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Early dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):737-744.

5. Gallo RA, Gamradt SC, Mattern CJ, et al; Sports Medicine and Shoulder Service at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY. Instability after reverse total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):584-590.

6. Walch G, Bacle G, Lädermann A, Nové-Josserand L, Smithers CJ. Do the indications, results, and complications of reverse shoulder arthroplasty change with surgeon’s experience? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1470-1477.

7. Smith CD, Guyver P, Bunker TD. Indications for reverse shoulder replacement: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):577-583.

8. Young AA, Smith MM, Bacle G, Moraga C, Walch G. Early results of reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(20):1915-1923.

9. Hedtmann A, Werner A. Shoulder arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis [in German]. Orthopade. 2007;36(11):1050-1061.

10. Rittmeister M, Kerschbaumer F. Grammont reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and nonreconstructible rotator cuff lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(1):17-22.

11. Acevedo DC, Vanbeek C, Lazarus MD, Williams GR, Abboud JA. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures: update on indications, technique, and results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(2):279-289.

12. Bufquin T, Hersan A, Hubert L, Massin P. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: a prospective review of 43 cases with a short-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(4):516-520.

13. Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2050-2055.

14. Walker M, Willis MP, Brooks JP, Pupello D, Mulieri PJ, Frankle MA. The use of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of failed total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(4):514-522.

15. Valenti P, Kilinc AS, Sauzières P, Katz D. Results of 30 reverse shoulder prostheses for revision of failed hemi- or total shoulder arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(8):1375-1382.

16. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383.

17. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619.

18. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

19. Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer Award 2005: the Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):527-540.

20. Cuff D, Pupello D, Virani N, Levy J, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1244-1251.

21. Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, Saleem A, Mighell M, Vasey M. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1697-1705.

22. Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1742-1747.

23. Mulieri P, Dunning P, Klein S, Pupello D, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tear without glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2544-2556.

24. Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Molé D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(3):388-395.

25. Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(7):1476-1485.

26. Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1476-1486.

27. Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. The reverse shoulder prosthesis in the treatment of fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):535-539.

28. Stephenson DR, Oh JH, McGarry MH, Rick Hatch GF 3rd, Lee TQ. Effect of humeral component version on impingement in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):652-658.

29. Edwards TB, Williams MD, Labriola JE, Elkousy HA, Gartsman GM, O’Connor DP. Subscapularis insufficiency and the risk of shoulder dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):892-896.

30. Affonso J, Nicholson GP, Frankle MA, et al. Complications of the reverse prosthesis: prevention and treatment. Instr Course Lect. 2012;61:157-168.

31. Gutiérrez S, Keller TS, Levy JC, Lee WE 3rd, Luo ZP. Hierarchy of stability factors in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):670-676.

32. Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):147S-161S.

33. Clark JC, Ritchie J, Song FS, et al. Complication rates, dislocation, pain, and postoperative range of motion after reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with and without repair of the subscapularis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):36-41.

34. Richards J, Inacio MC, Beckett M, et al. Patient and procedure-specific risk factors for deep infection after primary shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(9):2809-2815.

35. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Schleck C, Harmsen WS, Cofield RH. Periprosthetic infections after total shoulder arthroplasty: a 33-year perspective. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1534-1541.

Risk factors for dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) are not clearly defined. Prosthetic dislocation can result in poor patient satisfaction, worse functional outcomes, and return to the operating room.1-3 As a result, identification of modifiable risk factors for complications represents an important research initiative for shoulder surgeons.

There is a paucity of literature devoted to the study of dislocation after RTSA. Chalmers and colleagues4 found a 2.9% (11/385) incidence of early dislocation within 3 months after index surgery—an improvement over the 15.8% reported for early instability over the period 2004–2006.5 As prosthesis design has improved and surgeons have become more comfortable with the RTSA prosthesis, surgical indications have expanded,6,7 and dislocation rates appear to have decreased. Although the most common indication for RTSA continues to be cuff tear arthropathy (CTA),6 there has been increased use in rheumatoid arthritis8-10; proximal humerus fractures, especially in cases of poor bone quality and unreliable fixation of tuberosities11-13; and failed previous shoulder reconstruction.14,15 As RTSA is performed more often, limiting the complications will become more important for both patient care and economics.

We conducted a study to analyze dislocation rates at our institution and to identify both modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for dislocation after RTSA. By identifying risk factors for dislocation, we will be able to implement additional perioperative clinical measures to reduce the incidence of dislocation.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study of dislocation after RTSA was conducted at the Rothman Institute of Orthopedics and Methodist Hospital (Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, Philadelphia, PA). After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for the study, we searched our institution’s electronic database of shoulder arthroplasties to identify all RTSAs performed at our 2 large-volume urban institutions between September 27, 2010 and December 31, 2013. For the record search, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes were used (Table 1).

The medical records of each patient were used to identify independent variables that could be associated with dislocation rate. Demographic variables included sex, age, and race. Preoperative clinical data included body mass index (BMI), etiology of shoulder disease leading to RTSA, individual comorbidities, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)16 modified to be used with ICD-9 codes.17 In addition, prior shoulder surgery history and arthroplasty type (primary or revision) were determined. Postoperative considerations were time to dislocation, mechanism of dislocation, and intervention(s) needed for dislocation. Although the institutional database did not include operative variables such as prosthesis type and surgical approach, all 6 surgeons in this study were using a standard deltopectoral approach in beach-chair position with a Grammont style prosthesis for RTSA cases.

Descriptive statistics for RTSA patients and the dislocation subpopulation were compiled. Bivariate analysis was used to evaluate which of the previously described variables influenced dislocation rates. Last, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate which factors were independent predictors of dislocation. We included demographic variables (age, sex, ethnicity), clinical variables (BMI, individual comorbidities, CCI), and surgical variables (primary vs revision, diagnosis at time of surgery). All statistical analyses were performed with Excel 2013 (Microsoft) and SPSS Statistics Version 20.0 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

From the database, we identified 487 patients who underwent 510 RTSAs during the study period. These surgeries were performed by 6 shoulder and elbow fellowship–trained surgeons. Of the 510 RTSAs, 393 (77.1%) were primary cases, and 117 (22.9%) were revision cases.

Of the 510 shoulders that underwent RTSA, 15 (2.9%; 14 patients) dislocated. Of these 15 cases, 5 were primary (1.3% of all primary cases) and 10 were revision (8.5% of all revision cases). Mean time from index surgery to diagnosis of dislocation was 58.2 days (range, 0-319 days). One dislocation occurred immediately after surgery, 2 after falls, 4 from patient-identified low-energy mechanisms of injury, and 8 without known inciting events. Nine dislocations (60%) did not have a subscapularis repair (7 were irreparable, 2 underwent subscapularis peel without repair), and the other 6 were repaired primarily (Table 2).

Male patients accounted for 32.2% of the study population but 60.0% of the dislocations (P = .019) (Table 3).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed revision arthroplasty (OR = 7.515; P = .042) and increased BMI (OR = 1.09; P = .047) to be independent risk factors for dislocation after RTSA. Analysis also found a diagnosis of primary CTA to be independently associated with lower risk of dislocation after RTSA (OR = 0.025; P = .008). Last, the previously described risk factor of male sex was found not to be a significant independent risk factor, though it did trend positively (OR = 3.011; P = .071).

Discussion

With more RTSAs being performed, evaluation of their common complications becomes increasingly important.18 We found a 3.0% rate of dislocation after RTSA, which is consistent with the most recently reported incidence4 and falls within the previously described range of 0% to 8.6%.19-26 Of the clinical risk factors identified in this study, those previously described were prior surgery, subscapularis insufficiency, higher BMI, and male sex.4 However, our finding of lower risk of dislocation after RTSA for primary rotator cuff pathology was not previously described. Although Chalmers and colleagues4 did not report this lower risk, 3 (27.3%) of their 11 patients with dislocation had primary CTA, compared with 1 (6.7%) of 15 patients in the present study.4 Our literature review did not identify any studies that independently reported the dislocation rate in patients who underwent RTSA for rotator cuff failure.

The risk factors of subscapularis irreparability and revision surgery suggest the importance of the soft-tissue envelope and bony anatomy in dislocation prevention. Previous analyses have suggested implant malpositioning,27,28 poor subscapularis quality,29 and inadequate muscle tensioning5,30-32 as risk factors for RTSA. Patients with an irreparable subscapularis tendon have often had multiple surgeries with compromise to the muscle/soft-tissue envelope or bony anatomy of the shoulder. A biomechanical study by Gutiérrez and colleagues31 found the compressive forces of the soft tissue at the glenohumeral joint to be the most important contributor to stability in the RTSA prosthesis. In clinical studies, the role of the subscapularis in preventing instability after RTSA remains unclear. Edwards and colleagues29 prospectively compared dislocation rates in patients with reparable and irreparable subscapularis tendons during RTSA and found a higher rate of dislocation in the irreparable subscapularis group. Of note, patients in the irreparable subscapularis group also had more complex diagnoses, including proximal humeral nonunion, fixed glenohumeral dislocation, and failed prior arthroplasty. Clark and colleagues33 retrospectively analyzed subscapularis repair in 2 RTSA groups and found no appreciable effect on complication rate, dislocation events, range-of-motion gains, or pain relief.

Our finding that higher BMI is an independent risk factor was previously described.4 The association is unclear but could be related to implant positioning, difficulty in intraoperative assessment of muscle tensioning, or body habitus that may generate a lever arm for impingement and dislocation when the arm is in adduction. Last, our finding that male sex is a risk factor for dislocation approached significance, and this relationship was previously reported.4 This could be attributable to a higher rate of activity or of indolent infection in male patients.34,35Besides studying risk factors for dislocation after RTSA, we investigated treatment. None of our patients were treated successfully and definitively with closed reduction in the clinic. This finding diverges from findings in studies by Teusink and colleagues2 and Chalmers and colleagues,4who respectively reported 62% and 44% rates of success with closed reduction. Our cohort of 14 patients with 15 dislocations required a total of 17 trips to the operating room after dislocation. This significantly higher rate of return to the operating room suggests that dislocation after RTSA may be a more costly and morbid problem than has been previously described.

This study had several weaknesses. Despite its large consecutive series of patients, the study was retrospective, and several variables that would be documented and controlled in a prospective study could not be measured here. Specifically, neither preoperative physical examination nor patient-specific assessments of pain or function were consistently obtained. Similarly, postoperative patient-specific instruments of outcomes evaluation were not obtained consistently, so results of patients with dislocation could not be compared with those of a control group. In addition, preoperative and postoperative radiographs were not consistently present in our electronic medical records, so the influence of preoperative bony anatomy, intraoperative limb lengthening, and any implant malpositioning could not be determined. Furthermore, operative details, such as reparability of the subscapularis, were not fully available for the control group and could not be included in statistical analysis. In addition, that the known dislocation risk factor of male sex4 was identified here but was not significant in multivariate regression analysis suggests that this study may not have been adequately powered to identify a significant difference in dislocation rate between the sexes. Last, though our results suggested associations between the aforementioned variables and dislocation after RTSA, a truly causative relationship could not be confirmed with this study design or analysis. Therefore, our study findings are hypothesis-generating and may indicate a benefit to greater deltoid tensioning, use of retentive liners, or more conservative rehabilitation protocols for high-risk patients.

Conclusion

Dislocation after RTSA is an uncommon complication that often requires a return to the operating room. This study identified a modifiable risk factor (higher BMI) and 3 nonmodifiable risk factors (male sex, subscapularis insufficiency, revision surgery) for dislocation after RTSA. In contrast, patients who undergo RTSA for primary rotator cuff pathology are unlikely to dislocate after surgery. This low risk of dislocation after RTSA for primary cuff pathology was not previously described. Patients in the higher risk category may benefit from preoperative lifestyle modification, intraoperative techniques for increasing stability, and more conservative therapy after surgery. In addition, unlike previous investigations, this study did not find closed reduction in the clinic alone to be successful in definitively treating this patient population.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E444-E450. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

Risk factors for dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty (RTSA) are not clearly defined. Prosthetic dislocation can result in poor patient satisfaction, worse functional outcomes, and return to the operating room.1-3 As a result, identification of modifiable risk factors for complications represents an important research initiative for shoulder surgeons.

There is a paucity of literature devoted to the study of dislocation after RTSA. Chalmers and colleagues4 found a 2.9% (11/385) incidence of early dislocation within 3 months after index surgery—an improvement over the 15.8% reported for early instability over the period 2004–2006.5 As prosthesis design has improved and surgeons have become more comfortable with the RTSA prosthesis, surgical indications have expanded,6,7 and dislocation rates appear to have decreased. Although the most common indication for RTSA continues to be cuff tear arthropathy (CTA),6 there has been increased use in rheumatoid arthritis8-10; proximal humerus fractures, especially in cases of poor bone quality and unreliable fixation of tuberosities11-13; and failed previous shoulder reconstruction.14,15 As RTSA is performed more often, limiting the complications will become more important for both patient care and economics.

We conducted a study to analyze dislocation rates at our institution and to identify both modifiable and nonmodifiable risk factors for dislocation after RTSA. By identifying risk factors for dislocation, we will be able to implement additional perioperative clinical measures to reduce the incidence of dislocation.

Materials and Methods

This retrospective study of dislocation after RTSA was conducted at the Rothman Institute of Orthopedics and Methodist Hospital (Thomas Jefferson University Hospitals, Philadelphia, PA). After obtaining Institutional Review Board approval for the study, we searched our institution’s electronic database of shoulder arthroplasties to identify all RTSAs performed at our 2 large-volume urban institutions between September 27, 2010 and December 31, 2013. For the record search, International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) codes were used (Table 1).

The medical records of each patient were used to identify independent variables that could be associated with dislocation rate. Demographic variables included sex, age, and race. Preoperative clinical data included body mass index (BMI), etiology of shoulder disease leading to RTSA, individual comorbidities, and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)16 modified to be used with ICD-9 codes.17 In addition, prior shoulder surgery history and arthroplasty type (primary or revision) were determined. Postoperative considerations were time to dislocation, mechanism of dislocation, and intervention(s) needed for dislocation. Although the institutional database did not include operative variables such as prosthesis type and surgical approach, all 6 surgeons in this study were using a standard deltopectoral approach in beach-chair position with a Grammont style prosthesis for RTSA cases.

Descriptive statistics for RTSA patients and the dislocation subpopulation were compiled. Bivariate analysis was used to evaluate which of the previously described variables influenced dislocation rates. Last, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to evaluate which factors were independent predictors of dislocation. We included demographic variables (age, sex, ethnicity), clinical variables (BMI, individual comorbidities, CCI), and surgical variables (primary vs revision, diagnosis at time of surgery). All statistical analyses were performed with Excel 2013 (Microsoft) and SPSS Statistics Version 20.0 (SPSS Inc.).

Results

From the database, we identified 487 patients who underwent 510 RTSAs during the study period. These surgeries were performed by 6 shoulder and elbow fellowship–trained surgeons. Of the 510 RTSAs, 393 (77.1%) were primary cases, and 117 (22.9%) were revision cases.

Of the 510 shoulders that underwent RTSA, 15 (2.9%; 14 patients) dislocated. Of these 15 cases, 5 were primary (1.3% of all primary cases) and 10 were revision (8.5% of all revision cases). Mean time from index surgery to diagnosis of dislocation was 58.2 days (range, 0-319 days). One dislocation occurred immediately after surgery, 2 after falls, 4 from patient-identified low-energy mechanisms of injury, and 8 without known inciting events. Nine dislocations (60%) did not have a subscapularis repair (7 were irreparable, 2 underwent subscapularis peel without repair), and the other 6 were repaired primarily (Table 2).

Male patients accounted for 32.2% of the study population but 60.0% of the dislocations (P = .019) (Table 3).

Multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed revision arthroplasty (OR = 7.515; P = .042) and increased BMI (OR = 1.09; P = .047) to be independent risk factors for dislocation after RTSA. Analysis also found a diagnosis of primary CTA to be independently associated with lower risk of dislocation after RTSA (OR = 0.025; P = .008). Last, the previously described risk factor of male sex was found not to be a significant independent risk factor, though it did trend positively (OR = 3.011; P = .071).

Discussion

With more RTSAs being performed, evaluation of their common complications becomes increasingly important.18 We found a 3.0% rate of dislocation after RTSA, which is consistent with the most recently reported incidence4 and falls within the previously described range of 0% to 8.6%.19-26 Of the clinical risk factors identified in this study, those previously described were prior surgery, subscapularis insufficiency, higher BMI, and male sex.4 However, our finding of lower risk of dislocation after RTSA for primary rotator cuff pathology was not previously described. Although Chalmers and colleagues4 did not report this lower risk, 3 (27.3%) of their 11 patients with dislocation had primary CTA, compared with 1 (6.7%) of 15 patients in the present study.4 Our literature review did not identify any studies that independently reported the dislocation rate in patients who underwent RTSA for rotator cuff failure.

The risk factors of subscapularis irreparability and revision surgery suggest the importance of the soft-tissue envelope and bony anatomy in dislocation prevention. Previous analyses have suggested implant malpositioning,27,28 poor subscapularis quality,29 and inadequate muscle tensioning5,30-32 as risk factors for RTSA. Patients with an irreparable subscapularis tendon have often had multiple surgeries with compromise to the muscle/soft-tissue envelope or bony anatomy of the shoulder. A biomechanical study by Gutiérrez and colleagues31 found the compressive forces of the soft tissue at the glenohumeral joint to be the most important contributor to stability in the RTSA prosthesis. In clinical studies, the role of the subscapularis in preventing instability after RTSA remains unclear. Edwards and colleagues29 prospectively compared dislocation rates in patients with reparable and irreparable subscapularis tendons during RTSA and found a higher rate of dislocation in the irreparable subscapularis group. Of note, patients in the irreparable subscapularis group also had more complex diagnoses, including proximal humeral nonunion, fixed glenohumeral dislocation, and failed prior arthroplasty. Clark and colleagues33 retrospectively analyzed subscapularis repair in 2 RTSA groups and found no appreciable effect on complication rate, dislocation events, range-of-motion gains, or pain relief.

Our finding that higher BMI is an independent risk factor was previously described.4 The association is unclear but could be related to implant positioning, difficulty in intraoperative assessment of muscle tensioning, or body habitus that may generate a lever arm for impingement and dislocation when the arm is in adduction. Last, our finding that male sex is a risk factor for dislocation approached significance, and this relationship was previously reported.4 This could be attributable to a higher rate of activity or of indolent infection in male patients.34,35Besides studying risk factors for dislocation after RTSA, we investigated treatment. None of our patients were treated successfully and definitively with closed reduction in the clinic. This finding diverges from findings in studies by Teusink and colleagues2 and Chalmers and colleagues,4who respectively reported 62% and 44% rates of success with closed reduction. Our cohort of 14 patients with 15 dislocations required a total of 17 trips to the operating room after dislocation. This significantly higher rate of return to the operating room suggests that dislocation after RTSA may be a more costly and morbid problem than has been previously described.

This study had several weaknesses. Despite its large consecutive series of patients, the study was retrospective, and several variables that would be documented and controlled in a prospective study could not be measured here. Specifically, neither preoperative physical examination nor patient-specific assessments of pain or function were consistently obtained. Similarly, postoperative patient-specific instruments of outcomes evaluation were not obtained consistently, so results of patients with dislocation could not be compared with those of a control group. In addition, preoperative and postoperative radiographs were not consistently present in our electronic medical records, so the influence of preoperative bony anatomy, intraoperative limb lengthening, and any implant malpositioning could not be determined. Furthermore, operative details, such as reparability of the subscapularis, were not fully available for the control group and could not be included in statistical analysis. In addition, that the known dislocation risk factor of male sex4 was identified here but was not significant in multivariate regression analysis suggests that this study may not have been adequately powered to identify a significant difference in dislocation rate between the sexes. Last, though our results suggested associations between the aforementioned variables and dislocation after RTSA, a truly causative relationship could not be confirmed with this study design or analysis. Therefore, our study findings are hypothesis-generating and may indicate a benefit to greater deltoid tensioning, use of retentive liners, or more conservative rehabilitation protocols for high-risk patients.

Conclusion

Dislocation after RTSA is an uncommon complication that often requires a return to the operating room. This study identified a modifiable risk factor (higher BMI) and 3 nonmodifiable risk factors (male sex, subscapularis insufficiency, revision surgery) for dislocation after RTSA. In contrast, patients who undergo RTSA for primary rotator cuff pathology are unlikely to dislocate after surgery. This low risk of dislocation after RTSA for primary cuff pathology was not previously described. Patients in the higher risk category may benefit from preoperative lifestyle modification, intraoperative techniques for increasing stability, and more conservative therapy after surgery. In addition, unlike previous investigations, this study did not find closed reduction in the clinic alone to be successful in definitively treating this patient population.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E444-E450. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Aldinger PR, Raiss P, Rickert M, Loew M. Complications in shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of 485 cases. Int Orthop. 2010;34(4):517-524.

2. Teusink MJ, Pappou IP, Schwartz DG, Cottrell BJ, Frankle MA. Results of closed management of acute dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(4):621-627.

3. Fink Barnes LA, Grantham WJ, Meadows MC, Bigliani LU, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Sports activity after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Orthop. 2015;44(2):68-72.

4. Chalmers PN, Rahman Z, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Early dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):737-744.

5. Gallo RA, Gamradt SC, Mattern CJ, et al; Sports Medicine and Shoulder Service at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY. Instability after reverse total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):584-590.

6. Walch G, Bacle G, Lädermann A, Nové-Josserand L, Smithers CJ. Do the indications, results, and complications of reverse shoulder arthroplasty change with surgeon’s experience? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1470-1477.

7. Smith CD, Guyver P, Bunker TD. Indications for reverse shoulder replacement: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):577-583.

8. Young AA, Smith MM, Bacle G, Moraga C, Walch G. Early results of reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(20):1915-1923.

9. Hedtmann A, Werner A. Shoulder arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis [in German]. Orthopade. 2007;36(11):1050-1061.

10. Rittmeister M, Kerschbaumer F. Grammont reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and nonreconstructible rotator cuff lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(1):17-22.

11. Acevedo DC, Vanbeek C, Lazarus MD, Williams GR, Abboud JA. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures: update on indications, technique, and results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(2):279-289.

12. Bufquin T, Hersan A, Hubert L, Massin P. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: a prospective review of 43 cases with a short-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(4):516-520.

13. Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2050-2055.

14. Walker M, Willis MP, Brooks JP, Pupello D, Mulieri PJ, Frankle MA. The use of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of failed total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(4):514-522.

15. Valenti P, Kilinc AS, Sauzières P, Katz D. Results of 30 reverse shoulder prostheses for revision of failed hemi- or total shoulder arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(8):1375-1382.

16. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383.

17. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619.

18. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

19. Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer Award 2005: the Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):527-540.

20. Cuff D, Pupello D, Virani N, Levy J, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1244-1251.

21. Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, Saleem A, Mighell M, Vasey M. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1697-1705.

22. Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1742-1747.

23. Mulieri P, Dunning P, Klein S, Pupello D, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tear without glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2544-2556.

24. Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Molé D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(3):388-395.

25. Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(7):1476-1485.

26. Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1476-1486.

27. Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. The reverse shoulder prosthesis in the treatment of fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):535-539.

28. Stephenson DR, Oh JH, McGarry MH, Rick Hatch GF 3rd, Lee TQ. Effect of humeral component version on impingement in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):652-658.

29. Edwards TB, Williams MD, Labriola JE, Elkousy HA, Gartsman GM, O’Connor DP. Subscapularis insufficiency and the risk of shoulder dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):892-896.

30. Affonso J, Nicholson GP, Frankle MA, et al. Complications of the reverse prosthesis: prevention and treatment. Instr Course Lect. 2012;61:157-168.

31. Gutiérrez S, Keller TS, Levy JC, Lee WE 3rd, Luo ZP. Hierarchy of stability factors in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):670-676.

32. Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):147S-161S.

33. Clark JC, Ritchie J, Song FS, et al. Complication rates, dislocation, pain, and postoperative range of motion after reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with and without repair of the subscapularis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):36-41.

34. Richards J, Inacio MC, Beckett M, et al. Patient and procedure-specific risk factors for deep infection after primary shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(9):2809-2815.

35. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Schleck C, Harmsen WS, Cofield RH. Periprosthetic infections after total shoulder arthroplasty: a 33-year perspective. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1534-1541.

1. Aldinger PR, Raiss P, Rickert M, Loew M. Complications in shoulder arthroplasty: an analysis of 485 cases. Int Orthop. 2010;34(4):517-524.

2. Teusink MJ, Pappou IP, Schwartz DG, Cottrell BJ, Frankle MA. Results of closed management of acute dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2015;24(4):621-627.

3. Fink Barnes LA, Grantham WJ, Meadows MC, Bigliani LU, Levine WN, Ahmad CS. Sports activity after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty with minimum 2-year follow-up. Am J Orthop. 2015;44(2):68-72.

4. Chalmers PN, Rahman Z, Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Early dislocation after reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(5):737-744.

5. Gallo RA, Gamradt SC, Mattern CJ, et al; Sports Medicine and Shoulder Service at the Hospital for Special Surgery, New York, NY. Instability after reverse total shoulder replacement. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):584-590.

6. Walch G, Bacle G, Lädermann A, Nové-Josserand L, Smithers CJ. Do the indications, results, and complications of reverse shoulder arthroplasty change with surgeon’s experience? J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1470-1477.

7. Smith CD, Guyver P, Bunker TD. Indications for reverse shoulder replacement: a systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2012;94(5):577-583.

8. Young AA, Smith MM, Bacle G, Moraga C, Walch G. Early results of reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(20):1915-1923.

9. Hedtmann A, Werner A. Shoulder arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis [in German]. Orthopade. 2007;36(11):1050-1061.

10. Rittmeister M, Kerschbaumer F. Grammont reverse total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis and nonreconstructible rotator cuff lesions. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2001;10(1):17-22.

11. Acevedo DC, Vanbeek C, Lazarus MD, Williams GR, Abboud JA. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for proximal humeral fractures: update on indications, technique, and results. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2014;23(2):279-289.

12. Bufquin T, Hersan A, Hubert L, Massin P. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of three- and four-part fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly: a prospective review of 43 cases with a short-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2007;89(4):516-520.

13. Cuff DJ, Pupello DR. Comparison of hemiarthroplasty and reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of proximal humeral fractures in elderly patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2013;95(22):2050-2055.

14. Walker M, Willis MP, Brooks JP, Pupello D, Mulieri PJ, Frankle MA. The use of the reverse shoulder arthroplasty for treatment of failed total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(4):514-522.

15. Valenti P, Kilinc AS, Sauzières P, Katz D. Results of 30 reverse shoulder prostheses for revision of failed hemi- or total shoulder arthroplasty. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2014;24(8):1375-1382.

16. Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373-383.

17. Deyo RA, Cherkin DC, Ciol MA. Adapting a clinical comorbidity index for use with ICD-9-CM administrative databases. J Clin Epidemiol. 1992;45(6):613-619.

18. Kim SH, Wise BL, Zhang Y, Szabo RM. Increasing incidence of shoulder arthroplasty in the United States. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2011;93(24):2249-2254.

19. Boileau P, Watkinson D, Hatzidakis AM, Hovorka I. Neer Award 2005: the Grammont reverse shoulder prosthesis: results in cuff tear arthritis, fracture sequelae, and revision arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2006;15(5):527-540.

20. Cuff D, Pupello D, Virani N, Levy J, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of rotator cuff deficiency. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2008;90(6):1244-1251.

21. Frankle M, Siegal S, Pupello D, Saleem A, Mighell M, Vasey M. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. A minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(8):1697-1705.

22. Guery J, Favard L, Sirveaux F, Oudet D, Mole D, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. Survivorship analysis of eighty replacements followed for five to ten years. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(8):1742-1747.

23. Mulieri P, Dunning P, Klein S, Pupello D, Frankle M. Reverse shoulder arthroplasty for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tear without glenohumeral arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2544-2556.

24. Sirveaux F, Favard L, Oudet D, Huquet D, Walch G, Molé D. Grammont inverted total shoulder arthroplasty in the treatment of glenohumeral osteoarthritis with massive rupture of the cuff. Results of a multicentre study of 80 shoulders. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(3):388-395.

25. Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O’Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(7):1476-1485.

26. Werner CM, Steinmann PA, Gilbart M, Gerber C. Treatment of painful pseudoparesis due to irreparable rotator cuff dysfunction with the Delta III reverse-ball-and-socket total shoulder prosthesis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87(7):1476-1486.

27. Cazeneuve JF, Cristofari DJ. The reverse shoulder prosthesis in the treatment of fractures of the proximal humerus in the elderly. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(4):535-539.

28. Stephenson DR, Oh JH, McGarry MH, Rick Hatch GF 3rd, Lee TQ. Effect of humeral component version on impingement in reverse total shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2011;20(4):652-658.

29. Edwards TB, Williams MD, Labriola JE, Elkousy HA, Gartsman GM, O’Connor DP. Subscapularis insufficiency and the risk of shoulder dislocation after reverse shoulder arthroplasty. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2009;18(6):892-896.

30. Affonso J, Nicholson GP, Frankle MA, et al. Complications of the reverse prosthesis: prevention and treatment. Instr Course Lect. 2012;61:157-168.

31. Gutiérrez S, Keller TS, Levy JC, Lee WE 3rd, Luo ZP. Hierarchy of stability factors in reverse shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466(3):670-676.

32. Boileau P, Watkinson DJ, Hatzidakis AM, Balg F. Grammont reverse prosthesis: design, rationale, and biomechanics. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(1 suppl S):147S-161S.

33. Clark JC, Ritchie J, Song FS, et al. Complication rates, dislocation, pain, and postoperative range of motion after reverse shoulder arthroplasty in patients with and without repair of the subscapularis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(1):36-41.

34. Richards J, Inacio MC, Beckett M, et al. Patient and procedure-specific risk factors for deep infection after primary shoulder arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2014;472(9):2809-2815.

35. Singh JA, Sperling JW, Schleck C, Harmsen WS, Cofield RH. Periprosthetic infections after total shoulder arthroplasty: a 33-year perspective. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2012;21(11):1534-1541.