User login

Insulin injection therapy is one of the most widely used health care interventions to manage both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T1DM/T2DM). Globally, more than 150 to 200 million people inject insulin into their upper posterior arms, buttocks, anterior and lateral thighs, or abdomen.1,2 In an ideal world, every patient would be using the correct site and rotating their insulin injection sites in accordance with health care professional (HCP) recommendations—systematic injections in one general body location, at least 1 cm away from the previous injection.2 Unfortunately, same-site insulin injection (repeatedly in the same region within 1 cm of previous injections) is a common mistake made by patients with DM—in one study, 63% of participants either did not rotate sites correctly or failed to do so at all.

Insulin-resistant cutaneous complications may occur as a result of same-site insulin injections. The most common is lipohypertrophy, reported in some studies in nearly 50% of patients with DM on insulin therapy.4 Other common cutaneous complications include lipoatrophy and amyloidosis. Injection-site acanthosis nigricans, although uncommon, has been reported in 18 cases in the literature.

Most articles suggest that same-site insulin injections decrease local insulin sensitivity and result in tissue hypertrophy because of the anabolic properties of insulin and increase in insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor.5-20 The hyperkeratotic growth and varying insulin absorption rates associated with these cutaneous complications increase chances of either hyper- or hypoglycemic episodes in patients.10,11,13 It is the responsibility of the DM care professional to provide proper insulin-injection technique education and perform routine inspection of injection sites to reduce cutaneous complications of insulin therapy. The purpose of this article is to (1) describe a case of acanthosis nigricans resulting from insulin injection at the same site; (2) review case reports

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old patient with an 8-year history of T2DM, as well as stable coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stage 3 chronic kidney disease, presented with 2 discrete abdominal hyperpigmented plaques. At the time of the initial clinic visit, the patient was taking metformin 1000 mg twice daily and insulin glargine 40 units once daily. When insulin was initiated 7 years prior, the patient received

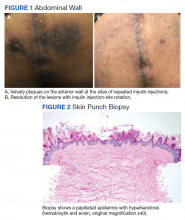

The patient reported 5 years of progressive, asymptomatic hyperpigmentation of the skin surrounding his insulin glargine injection sites and injecting in these same sites daily without rotation. He reported no additional skin changes or symptoms. He had noticed no skin changes while using NPH insulin during his first year of insulin therapy. On examination, the abdominal wall skin demonstrated 2 well-demarcated, nearly black, soft, velvety plaques, measuring 9 × 8 cm on the left side and 4 × 3.5 cm on the right, suggesting acanthosis nigricans (Figure 1A). The remainder of the skin examination, including the flexures, was normal. Of note, the patient received biweekly intramuscular testosterone injections in the gluteal region for secondary hypogonadism with no adverse dermatologic effects. A skin punch biopsy was performed and revealed epidermal papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis, confirming the clinical diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans (Figure 2).

After a review of insulin-injection technique at his clinic visit, the patient started rotating insulin injection sites over his entire abdomen, and the acanthosis nigricans partially improved. A few months later, the patient stopped rotating the insulin injection site, and the acanthosis nigricans worsened again. Because of worsening glycemic control, the patient was then started on insulin aspart. He did not develop any skin changes at the insulin aspart injection site, although he was not rotating its site of injection.

Subsequently, with reeducation and proper injection-site rotation, the patient had resolution of his acanthosis nigricans (Figure 1b).

Discussion

A review of the literature revealed 18 reported cases of acanthosis nigricans at sites of repeated insulin injection (Table).5-20 Acanthosis nigricans at the site of insulin injection afflicts patients of any age, with cases observed in patients aged 14 to 75 years. Sixteen (84%) of 19 cases were male. Fourteen cases (73%) had T2DM; the rest of the patients had T1DM. The duration of insulin injection therapy prior to onset ranged from immediate to 13 years (median 4 years). Fourteen cases (73%) were reported on the abdomen; however, other sites, such as thighs and upper arm, also were reported. Lesions size varied from 12 to 360 cm2. Two cases had associated amyloidosis. The average HbA1c reported at presentation was 10%. Following insulin injection-site rotation, most of the cases reported improvement of both glycemic control and acanthosis nigricans appearance.

In the case described by Kudo and colleagues, a 59-year-old male patient with T2DM had been injecting insulin into the same spot on his abdomen for 10 years. He developed acanthosis nigricans and an amyloidoma so large and firm that it bent the needle when he injected insulin.11

Most of the cases we found in the literature were after 2005 and associated with the use of human or analog insulin. These cases may be related to a bias, as cases may be easier to find in digital archives in the later years, when human or analog insulins have been in common use. Also noteworthy, in cases that reported dosage, most were not very high, and the highest daily dose was 240 IU/d. Ten reports of injection-site acanthosis nigricans were in dermatology journals; only 5 reports were in endocrinology journals and 3 in general medical journals, indicating possible less awareness of this phenomenon in other HCPs who care for patients with DM.

Complications of Same-Site Injections

Acanthosis nigricans. Commonly found in the armpits, neck folds, and groin, acanthosis nigricans is known as one of the calling cards for insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperinsulinemia.21 Acanthosis nigricans can be seen in people with or without DM and is not limited to those on insulin therapy. However, same-site insulin injections for 4 to 6 years also may result in injection-site acanthosis nigricans–like lesions because of factors such as insulin exposure at the local tissue level.16

Acanthosis nigricans development is characterized by hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic, velvety, and sometimes verrucous plaques.6 Acanthosis nigricans surrounding repeated injection sites is hypothesized to develop as a result of localized hyperinsulinemia secondary to insulin resistance, which increases the stimulation of IGF, thereby causing epidermal hypertrophy.5-20 If insulin injection therapy continues to be administered through the acanthosis nigricans lesion, it results in decreased insulin absorption, leading to poor glycemic control.13

Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin injection is reversible. After rotation of injection sites, lesions either decrease in size or severity of appearance.5-8,11 Also, by avoiding injection into the hyperkeratotic plaques and using normal subcutaneous tissue for injection, patients’ response to insulin improves, as measured by HbA1c and by decreased daily insulin requirement.6-8,10,12,18-20

Lipohypertrophy. This is characterized by an increase in localized adipose tissue and is the most common cutaneous complication of insulin therapy.2 Lipohypertrophy presents as a firm, rubbery mass in the location of same-site insulin injections.22 Development of lipohypertrophy is suspected to be the result of either (1) anabolic effect of insulin on local adipocytes, promoting fat and protein synthesis; (2) an autoimmune response by immunoglobulin (Ig) G or IgE antibodies to insulin, immune response to insulin of different species, or to insulin injection techniques; or (3) repeated trauma to the injection site from repeated needle usage.4,23

In a study assessing the prevalence of lipohypertrophy and its relation to insulin technique, 49.1% of participants with

Primary prevention measures include injection site inspection and patient education about rotation and abstaining from needle reuse.22 If a patient already has signs of lipohypertrophy, data supports education and insulin injection technique practice as simple and effective means to reduce insulin action variability and increase glycemic control.24

Lipoatrophy. Lipoatrophy is described as a local loss of subcutaneous adipose tissue often in the face, buttocks, legs and arm regions and can be rooted in genetic, immune, or drug-associated etiologies.25 Insulin-induced lipoatrophy is suspected to be the result of tumor necrosis factor-α hyperproduction in reaction to insulin crystal presence at the injection site.26,27 Overall, lipoatrophy development has decreased since the use of recombinant human insulin and analog insulin therapy.28 The decrease is hypothesized to be due to increased subcutaneous tissue absorption rate of human insulin and its analog, decreasing overall adipocyte exposure to localized high insulin concentration.27 Treatments for same-site insulin-derived lipoatrophy include changing injection sites and preparation of insulin.26 When injection into the lipoatrophic site was avoided, glycemic control and lipoatrophy appearance improved.26

Amyloidosis. Amyloidosis indicates the presence of an extracellular bundle of insoluble polymeric protein fibrils in tissues and organs.29 Insulin-induced amyloidosis presents as a hard mass or ball near the injection site.29 Insulin is one of many hormones that can form amyloid fibrils, and there have been several dozen cases reported of amyloid formation at the site of insulin injection.29-31 Although insulin-derived amyloidosis is rare, it may be misdiagnosed as lipohypertrophy due to a lack of histopathologic testing or general awareness of the complication.29

In a case series of 7 patients with amyloidosis, all patients had a mean HbA1c of 9.3% (range, 8.5-10.2%) and averaged 1 IU/kg bodyweight before intervention.30 After the discovery of the mass, participants were instructed to avoid injection into the amyloidoma, and average insulin requirements decreased to 0.48 IU/kg body weight (P = .40).30 Patients with amyloidosis who rotated their injection sites experienced better glycemic control and decreased insulin requirements.30

Pathophysiology of Localized Insulin Resistance

Insulin regulates glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, increases hepatic and adipocyte lipid synthesis, and decreases adipocyte fatty acid release.32 Generalized insulin resistance occurs when target tissues have decreased glucose uptake in response to circulating insulin.32 Insulin resistance increases the amount of free insulin in surrounding tissues. At high concentrations, insulin fosters tissue growth by binding to IGF-1 receptors, stimulating hypertrophy and reproduction of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.33 This pathophysiology helps explain the origin of localized acanthosis nigricans at same-site insulin injections.

Conclusions

Cutaneous complications are a local adverse effect of long-term failure to rotate insulin injection sites. Our case serves as a call to action for HCPs to improve education regarding insulin injection-site rotation, conduct routine injection-site inspection, and actively document cases as they occur to increase public awareness of these important complications.

If a patient with DM presents with unexplained poor glycemic control, consider questioning the patient about injection-site location and how often they are rotating the insulin injection site. Inspect the site for cutaneous complications. Of note, if a patient has a cutaneous complication due to insulin injection, adjust or decrease the insulin dosage when rotating sites to mitigate the risk of hypoglycemic episodes.

Improvement of glycemic control, cosmetic appearance of injection site, and insulin use all begin with skin inspection, injection technique education, and periodic review by a HCP.

1. Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016-2018. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(2):66-72. doi:10.1089/dia.2018.0384

2. Frid AH, Kreugel G, Grassi G, et al. New insulin delivery recommendations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(9):1231-1255. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.010

3. Blanco M, Hernández MT, Strauss KW, Amaya M. Prevalence and risk factors of lipohypertrophy in insulin-injecting patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(5):445-453. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2013.05.006

4. Johansson UB, Amsberg S, Hannerz L, et al. Impaired absorption of insulin aspart from lipohypertrophic injection sites. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):2025-2027. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.8.2025

5. Erickson L, Lipschutz DE, Wrigley W, Kearse WO. A peculiar cutaneous reaction to repeated injections of insulin. JAMA. 1969;209(6):934-935. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03160190056019

6. Fleming MG, Simon SI. Cutaneous insulin reaction resembling acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1001/archderm.1986.01660210104028 7. Gannon D, Ross MW, Mahajan T. Acanthosis nigricans-like plaque and lipohypertrophy in type 1 diabetes. Pract Diabetes International. 2005;22(6).

8. Mailler-Savage EA, Adams BB. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(1):126-127. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2007.27

9. Pachón Burgos A, Chan Aguilar MP. Visual vignette. Hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic cutaneous insulin reaction that resembles acanthosis nigricans with lipohypertrophy. Endocr Pract. 2008;14(4):514. doi:10.4158/EP.14.4.514

10. Buzási K, Sápi Z, Jermendy G. Acanthosis nigricans as a local cutaneous side effect of repeated human insulin injections. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(2):e34-e36. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2011.07.023

11. Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, Mukai K, Chen KR. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;38(1):25-29. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04373.x

12. Brodell JD Jr, Cannella JD, Helms SE. Case report: acanthosis nigricans resulting from repetitive same-site insulin injections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(12):e85-e87.

13. Kanwar A, Sawatkar G, Dogra S, Bhadada S. Acanthosis nigricans—an uncommon cutaneous adverse effect of a common medication: report of two cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(4):553. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.113112

14. Dhingra M, Garg G, Gupta M, Khurana U, Thami GP. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans: could it be a cause of increased insulin requirement? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(1):9. Published 2013 Jan 15.

15. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57(1):127-129. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.130920

16. Yahagi E, Mabuchi T, Nuruki H, et al. Case of exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans caused by insulin injections. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2014;39(1):5-9.

17. Chapman SE, Bandino JP. A verrucous plaque on the abdomen: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(12):e163. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000659

18. Huang Y, Hessami-Booshehri M. Acanthosis nigricans at sites of insulin injection in a man with diabetes. CMAJ. 2018;190(47):E1390. doi:10.1503/cmaj.180705

19. Pal R, Bhattacharjee R, Chatterjee D, Bhadada SK, Bhansali A, Dutta P. Exogenous insulin-induced localized acanthosis nigricans: a rare injection site complication. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44(3):219-221. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2019.08.010

20. Bomar L, Lewallen R, Jorizzo J. Localized acanthosis nigricans at the site of repetitive insulin injections. Cutis. 2020;105(2);E20-E22.

21. Karadağ AS, You Y, Danarti R, Al-Khuzaei S, Chen W. Acanthosis nigricans and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(1):48-53. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.008

22. Kalra S, Kumar A, Gupta Y. Prevention of lipohypertrophy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(7):910-911.

23. Singha A, Bhattarcharjee R, Ghosh S, Chakrabarti SK, Baidya A, Chowdhury S. Concurrence of lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy in children with type 1 diabetes using recombinant human insulin: two case reports. Clin Diabetes. 2016;34(1):51-53. doi:10.2337/diaclin.34.1.51

24. Famulla S, Hövelmann U, Fischer A, et al. Insulin injection into lipohypertrophic tissue: blunted and more variable insulin absorption and action and impaired postprandial glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(9):1486-1492. doi:10.2337/dc16-0610.

25. Reitman ML, Arioglu E, Gavrilova O, Taylor SI. Lipoatrophy revisited. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11(10):410-416. doi:10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00309-x

26. Kondo A, Nakamura A, Takeuchi J, Miyoshi H, Atsumi T. Insulin-Induced Distant Site Lipoatrophy. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(6):e67-e68. doi:10.2337/dc16-2385

27. Jermendy G, Nádas J, Sápi Z. “Lipoblastoma-like” lipoatrophy induced by human insulin: morphological evidence for local dedifferentiation of adipocytes?. Diabetologia. 2000;43(7):955-956. doi:10.1007/s001250051476

28. Mokta JK, Mokta KK, Panda P. Insulin lipodystrophy and lipohypertrophy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(4):773-774. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.113788

29. Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(1):174-177. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.146879

30. Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127(5):450-454. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.029

31. Swift B. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabet Med. 2002;19(10):881-882. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.07581.x

32. Sesti G. Pathophysiology of insulin resistance. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20(4):665-679. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2006.09.007

33. Phiske MM. An approach to acanthosis nigricans. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(3):239-249. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.137765

Insulin injection therapy is one of the most widely used health care interventions to manage both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T1DM/T2DM). Globally, more than 150 to 200 million people inject insulin into their upper posterior arms, buttocks, anterior and lateral thighs, or abdomen.1,2 In an ideal world, every patient would be using the correct site and rotating their insulin injection sites in accordance with health care professional (HCP) recommendations—systematic injections in one general body location, at least 1 cm away from the previous injection.2 Unfortunately, same-site insulin injection (repeatedly in the same region within 1 cm of previous injections) is a common mistake made by patients with DM—in one study, 63% of participants either did not rotate sites correctly or failed to do so at all.

Insulin-resistant cutaneous complications may occur as a result of same-site insulin injections. The most common is lipohypertrophy, reported in some studies in nearly 50% of patients with DM on insulin therapy.4 Other common cutaneous complications include lipoatrophy and amyloidosis. Injection-site acanthosis nigricans, although uncommon, has been reported in 18 cases in the literature.

Most articles suggest that same-site insulin injections decrease local insulin sensitivity and result in tissue hypertrophy because of the anabolic properties of insulin and increase in insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor.5-20 The hyperkeratotic growth and varying insulin absorption rates associated with these cutaneous complications increase chances of either hyper- or hypoglycemic episodes in patients.10,11,13 It is the responsibility of the DM care professional to provide proper insulin-injection technique education and perform routine inspection of injection sites to reduce cutaneous complications of insulin therapy. The purpose of this article is to (1) describe a case of acanthosis nigricans resulting from insulin injection at the same site; (2) review case reports

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old patient with an 8-year history of T2DM, as well as stable coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stage 3 chronic kidney disease, presented with 2 discrete abdominal hyperpigmented plaques. At the time of the initial clinic visit, the patient was taking metformin 1000 mg twice daily and insulin glargine 40 units once daily. When insulin was initiated 7 years prior, the patient received

The patient reported 5 years of progressive, asymptomatic hyperpigmentation of the skin surrounding his insulin glargine injection sites and injecting in these same sites daily without rotation. He reported no additional skin changes or symptoms. He had noticed no skin changes while using NPH insulin during his first year of insulin therapy. On examination, the abdominal wall skin demonstrated 2 well-demarcated, nearly black, soft, velvety plaques, measuring 9 × 8 cm on the left side and 4 × 3.5 cm on the right, suggesting acanthosis nigricans (Figure 1A). The remainder of the skin examination, including the flexures, was normal. Of note, the patient received biweekly intramuscular testosterone injections in the gluteal region for secondary hypogonadism with no adverse dermatologic effects. A skin punch biopsy was performed and revealed epidermal papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis, confirming the clinical diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans (Figure 2).

After a review of insulin-injection technique at his clinic visit, the patient started rotating insulin injection sites over his entire abdomen, and the acanthosis nigricans partially improved. A few months later, the patient stopped rotating the insulin injection site, and the acanthosis nigricans worsened again. Because of worsening glycemic control, the patient was then started on insulin aspart. He did not develop any skin changes at the insulin aspart injection site, although he was not rotating its site of injection.

Subsequently, with reeducation and proper injection-site rotation, the patient had resolution of his acanthosis nigricans (Figure 1b).

Discussion

A review of the literature revealed 18 reported cases of acanthosis nigricans at sites of repeated insulin injection (Table).5-20 Acanthosis nigricans at the site of insulin injection afflicts patients of any age, with cases observed in patients aged 14 to 75 years. Sixteen (84%) of 19 cases were male. Fourteen cases (73%) had T2DM; the rest of the patients had T1DM. The duration of insulin injection therapy prior to onset ranged from immediate to 13 years (median 4 years). Fourteen cases (73%) were reported on the abdomen; however, other sites, such as thighs and upper arm, also were reported. Lesions size varied from 12 to 360 cm2. Two cases had associated amyloidosis. The average HbA1c reported at presentation was 10%. Following insulin injection-site rotation, most of the cases reported improvement of both glycemic control and acanthosis nigricans appearance.

In the case described by Kudo and colleagues, a 59-year-old male patient with T2DM had been injecting insulin into the same spot on his abdomen for 10 years. He developed acanthosis nigricans and an amyloidoma so large and firm that it bent the needle when he injected insulin.11

Most of the cases we found in the literature were after 2005 and associated with the use of human or analog insulin. These cases may be related to a bias, as cases may be easier to find in digital archives in the later years, when human or analog insulins have been in common use. Also noteworthy, in cases that reported dosage, most were not very high, and the highest daily dose was 240 IU/d. Ten reports of injection-site acanthosis nigricans were in dermatology journals; only 5 reports were in endocrinology journals and 3 in general medical journals, indicating possible less awareness of this phenomenon in other HCPs who care for patients with DM.

Complications of Same-Site Injections

Acanthosis nigricans. Commonly found in the armpits, neck folds, and groin, acanthosis nigricans is known as one of the calling cards for insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperinsulinemia.21 Acanthosis nigricans can be seen in people with or without DM and is not limited to those on insulin therapy. However, same-site insulin injections for 4 to 6 years also may result in injection-site acanthosis nigricans–like lesions because of factors such as insulin exposure at the local tissue level.16

Acanthosis nigricans development is characterized by hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic, velvety, and sometimes verrucous plaques.6 Acanthosis nigricans surrounding repeated injection sites is hypothesized to develop as a result of localized hyperinsulinemia secondary to insulin resistance, which increases the stimulation of IGF, thereby causing epidermal hypertrophy.5-20 If insulin injection therapy continues to be administered through the acanthosis nigricans lesion, it results in decreased insulin absorption, leading to poor glycemic control.13

Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin injection is reversible. After rotation of injection sites, lesions either decrease in size or severity of appearance.5-8,11 Also, by avoiding injection into the hyperkeratotic plaques and using normal subcutaneous tissue for injection, patients’ response to insulin improves, as measured by HbA1c and by decreased daily insulin requirement.6-8,10,12,18-20

Lipohypertrophy. This is characterized by an increase in localized adipose tissue and is the most common cutaneous complication of insulin therapy.2 Lipohypertrophy presents as a firm, rubbery mass in the location of same-site insulin injections.22 Development of lipohypertrophy is suspected to be the result of either (1) anabolic effect of insulin on local adipocytes, promoting fat and protein synthesis; (2) an autoimmune response by immunoglobulin (Ig) G or IgE antibodies to insulin, immune response to insulin of different species, or to insulin injection techniques; or (3) repeated trauma to the injection site from repeated needle usage.4,23

In a study assessing the prevalence of lipohypertrophy and its relation to insulin technique, 49.1% of participants with

Primary prevention measures include injection site inspection and patient education about rotation and abstaining from needle reuse.22 If a patient already has signs of lipohypertrophy, data supports education and insulin injection technique practice as simple and effective means to reduce insulin action variability and increase glycemic control.24

Lipoatrophy. Lipoatrophy is described as a local loss of subcutaneous adipose tissue often in the face, buttocks, legs and arm regions and can be rooted in genetic, immune, or drug-associated etiologies.25 Insulin-induced lipoatrophy is suspected to be the result of tumor necrosis factor-α hyperproduction in reaction to insulin crystal presence at the injection site.26,27 Overall, lipoatrophy development has decreased since the use of recombinant human insulin and analog insulin therapy.28 The decrease is hypothesized to be due to increased subcutaneous tissue absorption rate of human insulin and its analog, decreasing overall adipocyte exposure to localized high insulin concentration.27 Treatments for same-site insulin-derived lipoatrophy include changing injection sites and preparation of insulin.26 When injection into the lipoatrophic site was avoided, glycemic control and lipoatrophy appearance improved.26

Amyloidosis. Amyloidosis indicates the presence of an extracellular bundle of insoluble polymeric protein fibrils in tissues and organs.29 Insulin-induced amyloidosis presents as a hard mass or ball near the injection site.29 Insulin is one of many hormones that can form amyloid fibrils, and there have been several dozen cases reported of amyloid formation at the site of insulin injection.29-31 Although insulin-derived amyloidosis is rare, it may be misdiagnosed as lipohypertrophy due to a lack of histopathologic testing or general awareness of the complication.29

In a case series of 7 patients with amyloidosis, all patients had a mean HbA1c of 9.3% (range, 8.5-10.2%) and averaged 1 IU/kg bodyweight before intervention.30 After the discovery of the mass, participants were instructed to avoid injection into the amyloidoma, and average insulin requirements decreased to 0.48 IU/kg body weight (P = .40).30 Patients with amyloidosis who rotated their injection sites experienced better glycemic control and decreased insulin requirements.30

Pathophysiology of Localized Insulin Resistance

Insulin regulates glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, increases hepatic and adipocyte lipid synthesis, and decreases adipocyte fatty acid release.32 Generalized insulin resistance occurs when target tissues have decreased glucose uptake in response to circulating insulin.32 Insulin resistance increases the amount of free insulin in surrounding tissues. At high concentrations, insulin fosters tissue growth by binding to IGF-1 receptors, stimulating hypertrophy and reproduction of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.33 This pathophysiology helps explain the origin of localized acanthosis nigricans at same-site insulin injections.

Conclusions

Cutaneous complications are a local adverse effect of long-term failure to rotate insulin injection sites. Our case serves as a call to action for HCPs to improve education regarding insulin injection-site rotation, conduct routine injection-site inspection, and actively document cases as they occur to increase public awareness of these important complications.

If a patient with DM presents with unexplained poor glycemic control, consider questioning the patient about injection-site location and how often they are rotating the insulin injection site. Inspect the site for cutaneous complications. Of note, if a patient has a cutaneous complication due to insulin injection, adjust or decrease the insulin dosage when rotating sites to mitigate the risk of hypoglycemic episodes.

Improvement of glycemic control, cosmetic appearance of injection site, and insulin use all begin with skin inspection, injection technique education, and periodic review by a HCP.

Insulin injection therapy is one of the most widely used health care interventions to manage both type 1 and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T1DM/T2DM). Globally, more than 150 to 200 million people inject insulin into their upper posterior arms, buttocks, anterior and lateral thighs, or abdomen.1,2 In an ideal world, every patient would be using the correct site and rotating their insulin injection sites in accordance with health care professional (HCP) recommendations—systematic injections in one general body location, at least 1 cm away from the previous injection.2 Unfortunately, same-site insulin injection (repeatedly in the same region within 1 cm of previous injections) is a common mistake made by patients with DM—in one study, 63% of participants either did not rotate sites correctly or failed to do so at all.

Insulin-resistant cutaneous complications may occur as a result of same-site insulin injections. The most common is lipohypertrophy, reported in some studies in nearly 50% of patients with DM on insulin therapy.4 Other common cutaneous complications include lipoatrophy and amyloidosis. Injection-site acanthosis nigricans, although uncommon, has been reported in 18 cases in the literature.

Most articles suggest that same-site insulin injections decrease local insulin sensitivity and result in tissue hypertrophy because of the anabolic properties of insulin and increase in insulin binding to insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) receptor.5-20 The hyperkeratotic growth and varying insulin absorption rates associated with these cutaneous complications increase chances of either hyper- or hypoglycemic episodes in patients.10,11,13 It is the responsibility of the DM care professional to provide proper insulin-injection technique education and perform routine inspection of injection sites to reduce cutaneous complications of insulin therapy. The purpose of this article is to (1) describe a case of acanthosis nigricans resulting from insulin injection at the same site; (2) review case reports

Case Presentation

A 75-year-old patient with an 8-year history of T2DM, as well as stable coronary artery disease, atrial fibrillation, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and stage 3 chronic kidney disease, presented with 2 discrete abdominal hyperpigmented plaques. At the time of the initial clinic visit, the patient was taking metformin 1000 mg twice daily and insulin glargine 40 units once daily. When insulin was initiated 7 years prior, the patient received

The patient reported 5 years of progressive, asymptomatic hyperpigmentation of the skin surrounding his insulin glargine injection sites and injecting in these same sites daily without rotation. He reported no additional skin changes or symptoms. He had noticed no skin changes while using NPH insulin during his first year of insulin therapy. On examination, the abdominal wall skin demonstrated 2 well-demarcated, nearly black, soft, velvety plaques, measuring 9 × 8 cm on the left side and 4 × 3.5 cm on the right, suggesting acanthosis nigricans (Figure 1A). The remainder of the skin examination, including the flexures, was normal. Of note, the patient received biweekly intramuscular testosterone injections in the gluteal region for secondary hypogonadism with no adverse dermatologic effects. A skin punch biopsy was performed and revealed epidermal papillomatosis and hyperkeratosis, confirming the clinical diagnosis of acanthosis nigricans (Figure 2).

After a review of insulin-injection technique at his clinic visit, the patient started rotating insulin injection sites over his entire abdomen, and the acanthosis nigricans partially improved. A few months later, the patient stopped rotating the insulin injection site, and the acanthosis nigricans worsened again. Because of worsening glycemic control, the patient was then started on insulin aspart. He did not develop any skin changes at the insulin aspart injection site, although he was not rotating its site of injection.

Subsequently, with reeducation and proper injection-site rotation, the patient had resolution of his acanthosis nigricans (Figure 1b).

Discussion

A review of the literature revealed 18 reported cases of acanthosis nigricans at sites of repeated insulin injection (Table).5-20 Acanthosis nigricans at the site of insulin injection afflicts patients of any age, with cases observed in patients aged 14 to 75 years. Sixteen (84%) of 19 cases were male. Fourteen cases (73%) had T2DM; the rest of the patients had T1DM. The duration of insulin injection therapy prior to onset ranged from immediate to 13 years (median 4 years). Fourteen cases (73%) were reported on the abdomen; however, other sites, such as thighs and upper arm, also were reported. Lesions size varied from 12 to 360 cm2. Two cases had associated amyloidosis. The average HbA1c reported at presentation was 10%. Following insulin injection-site rotation, most of the cases reported improvement of both glycemic control and acanthosis nigricans appearance.

In the case described by Kudo and colleagues, a 59-year-old male patient with T2DM had been injecting insulin into the same spot on his abdomen for 10 years. He developed acanthosis nigricans and an amyloidoma so large and firm that it bent the needle when he injected insulin.11

Most of the cases we found in the literature were after 2005 and associated with the use of human or analog insulin. These cases may be related to a bias, as cases may be easier to find in digital archives in the later years, when human or analog insulins have been in common use. Also noteworthy, in cases that reported dosage, most were not very high, and the highest daily dose was 240 IU/d. Ten reports of injection-site acanthosis nigricans were in dermatology journals; only 5 reports were in endocrinology journals and 3 in general medical journals, indicating possible less awareness of this phenomenon in other HCPs who care for patients with DM.

Complications of Same-Site Injections

Acanthosis nigricans. Commonly found in the armpits, neck folds, and groin, acanthosis nigricans is known as one of the calling cards for insulin resistance, obesity, and hyperinsulinemia.21 Acanthosis nigricans can be seen in people with or without DM and is not limited to those on insulin therapy. However, same-site insulin injections for 4 to 6 years also may result in injection-site acanthosis nigricans–like lesions because of factors such as insulin exposure at the local tissue level.16

Acanthosis nigricans development is characterized by hyperpigmented, hyperkeratotic, velvety, and sometimes verrucous plaques.6 Acanthosis nigricans surrounding repeated injection sites is hypothesized to develop as a result of localized hyperinsulinemia secondary to insulin resistance, which increases the stimulation of IGF, thereby causing epidermal hypertrophy.5-20 If insulin injection therapy continues to be administered through the acanthosis nigricans lesion, it results in decreased insulin absorption, leading to poor glycemic control.13

Acanthosis nigricans associated with insulin injection is reversible. After rotation of injection sites, lesions either decrease in size or severity of appearance.5-8,11 Also, by avoiding injection into the hyperkeratotic plaques and using normal subcutaneous tissue for injection, patients’ response to insulin improves, as measured by HbA1c and by decreased daily insulin requirement.6-8,10,12,18-20

Lipohypertrophy. This is characterized by an increase in localized adipose tissue and is the most common cutaneous complication of insulin therapy.2 Lipohypertrophy presents as a firm, rubbery mass in the location of same-site insulin injections.22 Development of lipohypertrophy is suspected to be the result of either (1) anabolic effect of insulin on local adipocytes, promoting fat and protein synthesis; (2) an autoimmune response by immunoglobulin (Ig) G or IgE antibodies to insulin, immune response to insulin of different species, or to insulin injection techniques; or (3) repeated trauma to the injection site from repeated needle usage.4,23

In a study assessing the prevalence of lipohypertrophy and its relation to insulin technique, 49.1% of participants with

Primary prevention measures include injection site inspection and patient education about rotation and abstaining from needle reuse.22 If a patient already has signs of lipohypertrophy, data supports education and insulin injection technique practice as simple and effective means to reduce insulin action variability and increase glycemic control.24

Lipoatrophy. Lipoatrophy is described as a local loss of subcutaneous adipose tissue often in the face, buttocks, legs and arm regions and can be rooted in genetic, immune, or drug-associated etiologies.25 Insulin-induced lipoatrophy is suspected to be the result of tumor necrosis factor-α hyperproduction in reaction to insulin crystal presence at the injection site.26,27 Overall, lipoatrophy development has decreased since the use of recombinant human insulin and analog insulin therapy.28 The decrease is hypothesized to be due to increased subcutaneous tissue absorption rate of human insulin and its analog, decreasing overall adipocyte exposure to localized high insulin concentration.27 Treatments for same-site insulin-derived lipoatrophy include changing injection sites and preparation of insulin.26 When injection into the lipoatrophic site was avoided, glycemic control and lipoatrophy appearance improved.26

Amyloidosis. Amyloidosis indicates the presence of an extracellular bundle of insoluble polymeric protein fibrils in tissues and organs.29 Insulin-induced amyloidosis presents as a hard mass or ball near the injection site.29 Insulin is one of many hormones that can form amyloid fibrils, and there have been several dozen cases reported of amyloid formation at the site of insulin injection.29-31 Although insulin-derived amyloidosis is rare, it may be misdiagnosed as lipohypertrophy due to a lack of histopathologic testing or general awareness of the complication.29

In a case series of 7 patients with amyloidosis, all patients had a mean HbA1c of 9.3% (range, 8.5-10.2%) and averaged 1 IU/kg bodyweight before intervention.30 After the discovery of the mass, participants were instructed to avoid injection into the amyloidoma, and average insulin requirements decreased to 0.48 IU/kg body weight (P = .40).30 Patients with amyloidosis who rotated their injection sites experienced better glycemic control and decreased insulin requirements.30

Pathophysiology of Localized Insulin Resistance

Insulin regulates glucose homeostasis in skeletal muscle and adipose tissue, increases hepatic and adipocyte lipid synthesis, and decreases adipocyte fatty acid release.32 Generalized insulin resistance occurs when target tissues have decreased glucose uptake in response to circulating insulin.32 Insulin resistance increases the amount of free insulin in surrounding tissues. At high concentrations, insulin fosters tissue growth by binding to IGF-1 receptors, stimulating hypertrophy and reproduction of keratinocytes and fibroblasts.33 This pathophysiology helps explain the origin of localized acanthosis nigricans at same-site insulin injections.

Conclusions

Cutaneous complications are a local adverse effect of long-term failure to rotate insulin injection sites. Our case serves as a call to action for HCPs to improve education regarding insulin injection-site rotation, conduct routine injection-site inspection, and actively document cases as they occur to increase public awareness of these important complications.

If a patient with DM presents with unexplained poor glycemic control, consider questioning the patient about injection-site location and how often they are rotating the insulin injection site. Inspect the site for cutaneous complications. Of note, if a patient has a cutaneous complication due to insulin injection, adjust or decrease the insulin dosage when rotating sites to mitigate the risk of hypoglycemic episodes.

Improvement of glycemic control, cosmetic appearance of injection site, and insulin use all begin with skin inspection, injection technique education, and periodic review by a HCP.

1. Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016-2018. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(2):66-72. doi:10.1089/dia.2018.0384

2. Frid AH, Kreugel G, Grassi G, et al. New insulin delivery recommendations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(9):1231-1255. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.010

3. Blanco M, Hernández MT, Strauss KW, Amaya M. Prevalence and risk factors of lipohypertrophy in insulin-injecting patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(5):445-453. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2013.05.006

4. Johansson UB, Amsberg S, Hannerz L, et al. Impaired absorption of insulin aspart from lipohypertrophic injection sites. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):2025-2027. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.8.2025

5. Erickson L, Lipschutz DE, Wrigley W, Kearse WO. A peculiar cutaneous reaction to repeated injections of insulin. JAMA. 1969;209(6):934-935. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03160190056019

6. Fleming MG, Simon SI. Cutaneous insulin reaction resembling acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1001/archderm.1986.01660210104028 7. Gannon D, Ross MW, Mahajan T. Acanthosis nigricans-like plaque and lipohypertrophy in type 1 diabetes. Pract Diabetes International. 2005;22(6).

8. Mailler-Savage EA, Adams BB. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(1):126-127. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2007.27

9. Pachón Burgos A, Chan Aguilar MP. Visual vignette. Hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic cutaneous insulin reaction that resembles acanthosis nigricans with lipohypertrophy. Endocr Pract. 2008;14(4):514. doi:10.4158/EP.14.4.514

10. Buzási K, Sápi Z, Jermendy G. Acanthosis nigricans as a local cutaneous side effect of repeated human insulin injections. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(2):e34-e36. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2011.07.023

11. Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, Mukai K, Chen KR. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;38(1):25-29. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04373.x

12. Brodell JD Jr, Cannella JD, Helms SE. Case report: acanthosis nigricans resulting from repetitive same-site insulin injections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(12):e85-e87.

13. Kanwar A, Sawatkar G, Dogra S, Bhadada S. Acanthosis nigricans—an uncommon cutaneous adverse effect of a common medication: report of two cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(4):553. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.113112

14. Dhingra M, Garg G, Gupta M, Khurana U, Thami GP. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans: could it be a cause of increased insulin requirement? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(1):9. Published 2013 Jan 15.

15. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57(1):127-129. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.130920

16. Yahagi E, Mabuchi T, Nuruki H, et al. Case of exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans caused by insulin injections. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2014;39(1):5-9.

17. Chapman SE, Bandino JP. A verrucous plaque on the abdomen: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(12):e163. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000659

18. Huang Y, Hessami-Booshehri M. Acanthosis nigricans at sites of insulin injection in a man with diabetes. CMAJ. 2018;190(47):E1390. doi:10.1503/cmaj.180705

19. Pal R, Bhattacharjee R, Chatterjee D, Bhadada SK, Bhansali A, Dutta P. Exogenous insulin-induced localized acanthosis nigricans: a rare injection site complication. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44(3):219-221. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2019.08.010

20. Bomar L, Lewallen R, Jorizzo J. Localized acanthosis nigricans at the site of repetitive insulin injections. Cutis. 2020;105(2);E20-E22.

21. Karadağ AS, You Y, Danarti R, Al-Khuzaei S, Chen W. Acanthosis nigricans and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(1):48-53. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.008

22. Kalra S, Kumar A, Gupta Y. Prevention of lipohypertrophy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(7):910-911.

23. Singha A, Bhattarcharjee R, Ghosh S, Chakrabarti SK, Baidya A, Chowdhury S. Concurrence of lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy in children with type 1 diabetes using recombinant human insulin: two case reports. Clin Diabetes. 2016;34(1):51-53. doi:10.2337/diaclin.34.1.51

24. Famulla S, Hövelmann U, Fischer A, et al. Insulin injection into lipohypertrophic tissue: blunted and more variable insulin absorption and action and impaired postprandial glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(9):1486-1492. doi:10.2337/dc16-0610.

25. Reitman ML, Arioglu E, Gavrilova O, Taylor SI. Lipoatrophy revisited. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11(10):410-416. doi:10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00309-x

26. Kondo A, Nakamura A, Takeuchi J, Miyoshi H, Atsumi T. Insulin-Induced Distant Site Lipoatrophy. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(6):e67-e68. doi:10.2337/dc16-2385

27. Jermendy G, Nádas J, Sápi Z. “Lipoblastoma-like” lipoatrophy induced by human insulin: morphological evidence for local dedifferentiation of adipocytes?. Diabetologia. 2000;43(7):955-956. doi:10.1007/s001250051476

28. Mokta JK, Mokta KK, Panda P. Insulin lipodystrophy and lipohypertrophy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(4):773-774. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.113788

29. Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(1):174-177. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.146879

30. Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127(5):450-454. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.029

31. Swift B. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabet Med. 2002;19(10):881-882. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.07581.x

32. Sesti G. Pathophysiology of insulin resistance. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20(4):665-679. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2006.09.007

33. Phiske MM. An approach to acanthosis nigricans. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(3):239-249. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.137765

1. Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016-2018. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(2):66-72. doi:10.1089/dia.2018.0384

2. Frid AH, Kreugel G, Grassi G, et al. New insulin delivery recommendations. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(9):1231-1255. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.06.010

3. Blanco M, Hernández MT, Strauss KW, Amaya M. Prevalence and risk factors of lipohypertrophy in insulin-injecting patients with diabetes. Diabetes Metab. 2013;39(5):445-453. doi:10.1016/j.diabet.2013.05.006

4. Johansson UB, Amsberg S, Hannerz L, et al. Impaired absorption of insulin aspart from lipohypertrophic injection sites. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(8):2025-2027. doi:10.2337/diacare.28.8.2025

5. Erickson L, Lipschutz DE, Wrigley W, Kearse WO. A peculiar cutaneous reaction to repeated injections of insulin. JAMA. 1969;209(6):934-935. doi:10.1001/jama.1969.03160190056019

6. Fleming MG, Simon SI. Cutaneous insulin reaction resembling acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 1986;122(9):1054-1056. doi:10.1001/archderm.1986.01660210104028 7. Gannon D, Ross MW, Mahajan T. Acanthosis nigricans-like plaque and lipohypertrophy in type 1 diabetes. Pract Diabetes International. 2005;22(6).

8. Mailler-Savage EA, Adams BB. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans. Arch Dermatol. 2008;144(1):126-127. doi:10.1001/archdermatol.2007.27

9. Pachón Burgos A, Chan Aguilar MP. Visual vignette. Hyperpigmented hyperkeratotic cutaneous insulin reaction that resembles acanthosis nigricans with lipohypertrophy. Endocr Pract. 2008;14(4):514. doi:10.4158/EP.14.4.514

10. Buzási K, Sápi Z, Jermendy G. Acanthosis nigricans as a local cutaneous side effect of repeated human insulin injections. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;94(2):e34-e36. doi:10.1016/j.diabres.2011.07.023

11. Kudo-Watanuki S, Kurihara E, Yamamoto K, Mukai K, Chen KR. Coexistence of insulin-derived amyloidosis and an overlying acanthosis nigricans-like lesion at the site of insulin injection. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2012;38(1):25-29. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.2012.04373.x

12. Brodell JD Jr, Cannella JD, Helms SE. Case report: acanthosis nigricans resulting from repetitive same-site insulin injections. J Drugs Dermatol. 2012;11(12):e85-e87.

13. Kanwar A, Sawatkar G, Dogra S, Bhadada S. Acanthosis nigricans—an uncommon cutaneous adverse effect of a common medication: report of two cases. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2013;79(4):553. doi:10.4103/0378-6323.113112

14. Dhingra M, Garg G, Gupta M, Khurana U, Thami GP. Exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans: could it be a cause of increased insulin requirement? Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(1):9. Published 2013 Jan 15.

15. Nandeesh BN, Rajalakshmi T, Shubha B. Cutaneous amyloidosis and insulin with coexistence of acanthosis nigricans. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2014;57(1):127-129. doi:10.4103/0377-4929.130920

16. Yahagi E, Mabuchi T, Nuruki H, et al. Case of exogenous insulin-derived acanthosis nigricans caused by insulin injections. Tokai J Exp Clin Med. 2014;39(1):5-9.

17. Chapman SE, Bandino JP. A verrucous plaque on the abdomen: challenge. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39(12):e163. doi:10.1097/DAD.0000000000000659

18. Huang Y, Hessami-Booshehri M. Acanthosis nigricans at sites of insulin injection in a man with diabetes. CMAJ. 2018;190(47):E1390. doi:10.1503/cmaj.180705

19. Pal R, Bhattacharjee R, Chatterjee D, Bhadada SK, Bhansali A, Dutta P. Exogenous insulin-induced localized acanthosis nigricans: a rare injection site complication. Can J Diabetes. 2020;44(3):219-221. doi:10.1016/j.jcjd.2019.08.010

20. Bomar L, Lewallen R, Jorizzo J. Localized acanthosis nigricans at the site of repetitive insulin injections. Cutis. 2020;105(2);E20-E22.

21. Karadağ AS, You Y, Danarti R, Al-Khuzaei S, Chen W. Acanthosis nigricans and the metabolic syndrome. Clin Dermatol. 2018;36(1):48-53. doi:10.1016/j.clindermatol.2017.09.008

22. Kalra S, Kumar A, Gupta Y. Prevention of lipohypertrophy. J Pak Med Assoc. 2016;66(7):910-911.

23. Singha A, Bhattarcharjee R, Ghosh S, Chakrabarti SK, Baidya A, Chowdhury S. Concurrence of lipoatrophy and lipohypertrophy in children with type 1 diabetes using recombinant human insulin: two case reports. Clin Diabetes. 2016;34(1):51-53. doi:10.2337/diaclin.34.1.51

24. Famulla S, Hövelmann U, Fischer A, et al. Insulin injection into lipohypertrophic tissue: blunted and more variable insulin absorption and action and impaired postprandial glucose control. Diabetes Care. 2016;39(9):1486-1492. doi:10.2337/dc16-0610.

25. Reitman ML, Arioglu E, Gavrilova O, Taylor SI. Lipoatrophy revisited. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2000;11(10):410-416. doi:10.1016/s1043-2760(00)00309-x

26. Kondo A, Nakamura A, Takeuchi J, Miyoshi H, Atsumi T. Insulin-Induced Distant Site Lipoatrophy. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(6):e67-e68. doi:10.2337/dc16-2385

27. Jermendy G, Nádas J, Sápi Z. “Lipoblastoma-like” lipoatrophy induced by human insulin: morphological evidence for local dedifferentiation of adipocytes?. Diabetologia. 2000;43(7):955-956. doi:10.1007/s001250051476

28. Mokta JK, Mokta KK, Panda P. Insulin lipodystrophy and lipohypertrophy. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2013;17(4):773-774. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.113788

29. Gupta Y, Singla G, Singla R. Insulin-derived amyloidosis. Indian J Endocrinol Metab. 2015;19(1):174-177. doi:10.4103/2230-8210.146879

30. Nagase T, Iwaya K, Iwaki Y, et al. Insulin-derived amyloidosis and poor glycemic control: a case series. Am J Med. 2014;127(5):450-454. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.10.029

31. Swift B. Examination of insulin injection sites: an unexpected finding of localized amyloidosis. Diabet Med. 2002;19(10):881-882. doi:10.1046/j.1464-5491.2002.07581.x

32. Sesti G. Pathophysiology of insulin resistance. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;20(4):665-679. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2006.09.007

33. Phiske MM. An approach to acanthosis nigricans. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2014;5(3):239-249. doi:10.4103/2229-5178.137765