User login

Malpractice reforms long espoused by Thomas E. Price, MD, Health & Human Services secretary, are fostering debate on whether national fixes are necessary in an improving liability landscape. Claims against health providers have decreased twofold and doctors nationwide have seen their premiums decrease steadily for a decade. But the numbers tell just part of the story, liability experts say.

“Most health policy and medical malpractice scholars would not describe the environment we’re in right now as a state of crisis, at least not compared to what we observed a decade ago,” said Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, health care policy professor at Harvard University, Boston, and a medical liability researcher.“But I would argue that malpractice is still a salient fact for most physicians. What’s much more important than focusing on changes over time is taking a static perspective and understanding the risk that a physician faces when it comes to malpractice.”

During just over 12 years in Congress, Dr. Price (R-Ga.) has consistently advocated for tort reform, proposing legislation that would restructure the lawsuit process. He supports damage caps and has recommended the creation of health care tribunals that would hear cases only after medical review. He has also proposed the development of national practice guidelines for doctors, which if followed could be used defensively.

“From exorbitant malpractice insurance premiums to the remarkably expensive practice of defensive medicine, it is my experience that the current culture of litigation costs patients hundreds of billions of dollars,” Dr. Price wrote in a 2009 commentary about his Empowering Patients First Act. “These costs do nothing to provide better care, but rather serve only as a defense against unyielding personal injury lawyers ...When malpractice suits are brought through specialized courts and viewed through the perspective of medically appropriate care, rather than a lottery mentality, we will see a decline in frivolous lawsuits.”

Data show lawsuits down

Claims data however, show that lawsuits against doctors are on the decline – and have been for more than 10 years. The rate of paid claims against physicians dropped from 18.6 to 9.9 paid claims per 1,000 physicians between 2002 and 2013, according to 2014 study by Michelle Mello of Stanford (Calif.) University and colleagues (JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10705). Another analysis found that claims decreased from 12 claims per 100 doctors in 2003 to 6 per 100 doctors in 2016, according to a study of claims from The Doctors Company database.

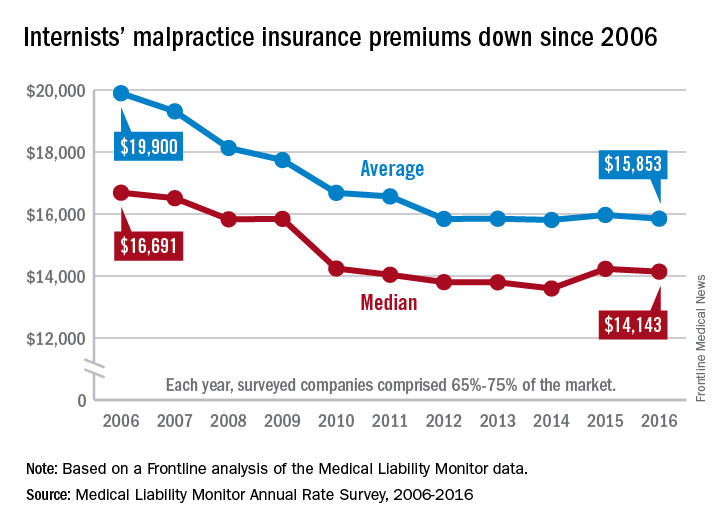

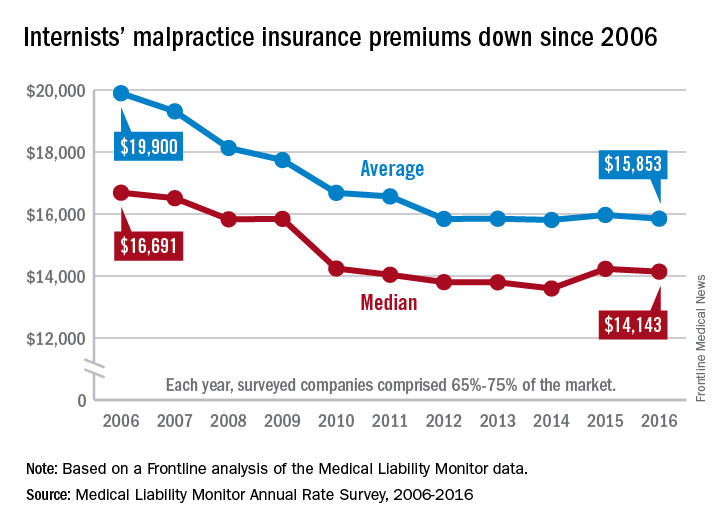

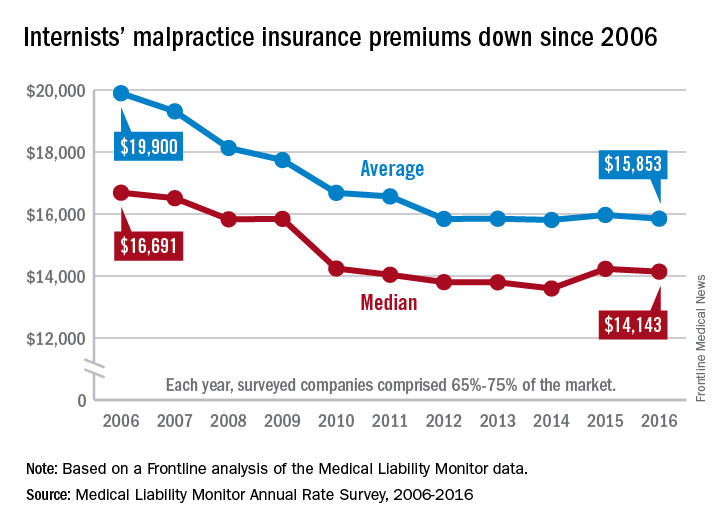

The sharp decline in claims is directly affecting premiums, which have remained nearly unchanged for years, said Michael Matray, editor of the Medical Liability Monitor (MLM), which tracks premium rates. In 2003, rate increases of 49% were commonplace, he noted, with some states reporting rises of 100%. But premiums started to fall in 2006, he said.

“We are in the midst of a 10-year soft market, the longest we’ve ever had,” Mr. Matray said in an interview. “In 2006, we started to soften. We have been soft or flat with no change since. It’s definitely unprecedented.”

In 2016, U.S. internists paid an average premium of $15,853, compared to an average premium payment of $19,900 in 2006 without inflation adjustment, according to this news organization’s analysis of MLM data. General surgeons meanwhile, paid an average of $52,905 in premiums in 2016, compared to a 2006 average of $68,186. Ob.gyns. paid an average premium of $72,999 in 2016, a drop from $93,230 in 2006.

“Generally speaking, it’s great for doctors,” Mr. Matray said. “Even if you remove the inflationary factor, there are some states where they are paying less now than they were 10 years ago.”

But stable premiums do not mean inexpensive insurance, noted Mike Stinson, vice president of government relations and public policy for the PIAA, a national trade association for medical liability insurers.

“They’ve certainly come down over the last few years,” Mr. Stinson said in an interview. “But they certainly are not low.”

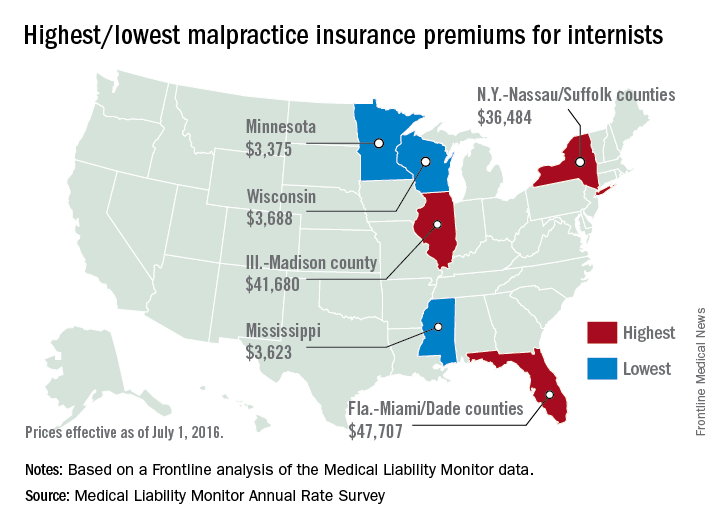

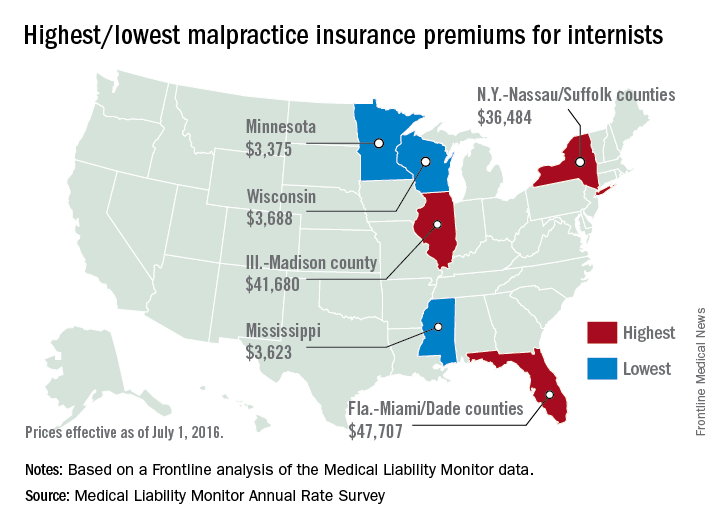

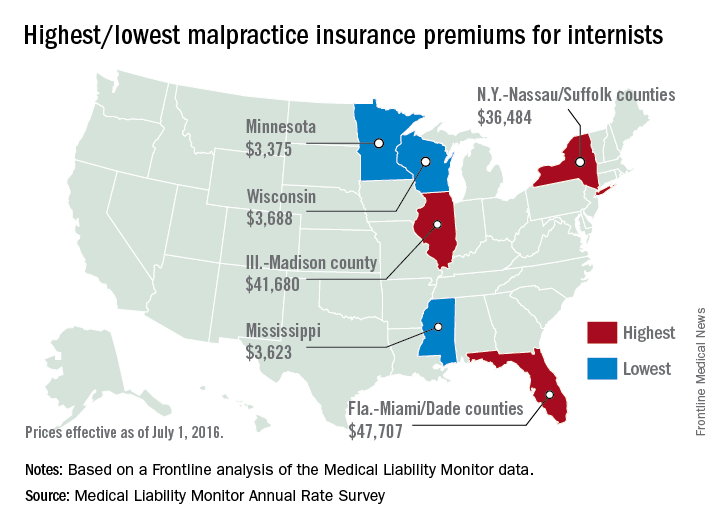

South Florida doctors for example, are paying among the highest premiums in the nation despite an overall drop in the last 10 years. Internists in Dade County, Fla., paid $47,707 for insurance in 2016, $27,000 less than in 2006, according to MLM data. Coverage is still is not affordable, said Jason M. Goldman, MD, an internist in private practice in Coral Springs, Fla., and governor for the American College of Physicians Florida chapter.

The premiums are ridiculous,” he said in an interview. “That’s one of the reasons I went bare. Having medical insurance makes you a target, because lawyers think, ‘We can sue the insurance company and the insurance company is going to pay.’ ”

State reforms driving lawsuit decline

A combination of state reforms and patient safety initiatives are fueling the lawsuit down slide, said Paul A. Greve Jr. senior vice president/senior consultant for Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice and coauthor of the 2016 MLM Survey report.

More than 25 states now have laws that enforce caps on noneconomic damages in medical liability cases, and in the last 15 years, a large majority have upheld such limits, Mr. Greve said. In addition, a number of states require a certificate of merit before suits can move forward, which mandate that a qualified physician verify that a defendant’s actions were likely negligent.

Patient safety programs such as internal patient safety committees, enhanced provider education, safety protocols, and communication and resolution programs, are also making an impact.

“There have been many efforts toward thinking innovatively about how we should be compensating patients more fairly and more quickly,” said Harvard’s Dr. Jena, who practices at Massachusetts General Hospital. “There are early disclosure programs that many hospitals have adopted as a movement toward that goal. The system is evolving.”

The high expense of filing a medical malpractice lawsuit is another factor detouring lawsuits, Mr. Greve added.

“It’s very expensive for [plaintiffs’ attorneys] to pursue these cases,” he said. “They have to invest a large amount of money into them and they can’t afford to take cases that have questionable liability, or they’re going to end up shelling out a lot of money and not getting anything in return.”

Malpractice system remains broken

While lawsuit and premium data paint a positive picture, the medical malpractice system remains dysfunctional for doctors and patients, said PIAA’s Mr. Stinson.

A majority of medical malpractice claims against physicians are determined to be nonmeritorious yet an average lawsuit takes roughly 4 years to resolve, he noted. Suits against doctors are dismissed by the court 54% of the time across all specialties, and among cases that go to trial, 80% end in the physician’s favor, according to a 2012 study by Dr. Jena and colleagues (JAMA Intern Med. 2012 Jun. 11 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2012.1416)

“We think that’s a huge amount of resources both in time and money and human capital to get poured into cases where no payment is ever deemed appropriate,” Mr. Stinson said. “We would like to see [malpractice] reforms in part because we think you can weed out some of these claims in advance, so more of the resources can be used to determine whether or not there was negligence and if so, making that patient whole as fast as possible.”

Regardless of declining claims, most physicians will still be sued in their lifetime, Dr. Jena said. By age 65, 75% of physicians in low-risk specialties have faced a malpractice claim, and 99% of doctors in high-risk specialties have been sued, according to a 2011 study by Dr. Jena and colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug. 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1012370)

“What really matters for physicians is not only whether they win or lose a malpractice suit, but whether they are sued in the first place,” Dr. Jena said. “Lawsuits happen quite often and over the course of a physician’s career they are quite common. So whether or not we’re in a state of malpractice crisis or not, the lifetime risk for physicians is quite real.”

The cost of defending claims continues to rise, noted Richard E. Anderson, MD, chair and CEO of The Doctors Company. At the same time, multi-million dollar malpractice verdicts have become more common.

“There’s still way too much malpractice litigation,” Dr. Anderson said. “The majority of it is fruitless, and the total cost burden borne by physicians has not decreased as much as the frequency because of the ongoing increase in severity.”

“The bottom line is defensive medicine is a huge and growing cost to all Americans,” he said. “We’re all on the hook for America’s rising health care bills. And as my increasingly infirm Baby Boomer generation gets older and weaker and sicker, those bills are going to rise that much faster. So the notion advanced by some so-called experts that we can nonetheless afford to spend a half trillion dollars a year or more on largely unnecessary testing driven in significant part by fear of litigation and giant outlier verdicts seems rather inane, and it suggests perhaps that those experts aren’t so expert.”

What would Dr. Price do?

Opinions are mixed about whether Dr. Price’s proposed reforms are the right changes for the medical liability system.

Expert panels to review claims for validity are a promising suggestion, Dr. Jena said. “Administrative courts to help identify malpractice cases that are truly malpractice early on is a good idea,” he said. “We want to have a system that prevents less meritorious cases from soaking up resources.”

But the idea may be easier said than done, said Dr. Anderson of The Doctors Company. “The devil is always in the details There is a lot of merit in [health courts] and they make a lot of sense. However, the notion of going from where we are today to an untested system, which would have to be a compromise between adversaries, would be a very challenging one.”

National clinical standards for physicians to follow and use as a safeguard could backfire, Mr. Stinson said. Bureaucracy could slow the guidelines from being promptly updated, and the standards could fail to keep up with the latest medical developments. As doctors know, medicine is not a one-size-fits-all approach, he added.

“[Guidelines] could encourage doctors to practice cookbook medicine, where they’re just going to follow the standard along without being given the opportunity to use their training and clinical experience to see whether that’s actually in the patient’s best interest,” Mr. Stinson said. “We certainly wouldn’t want to see a situation where a doctor feels diverting from a guidelines is in a patient’s best interest, but they don’t dare do it because it could subject them to a lawsuit.”

When enacting malpractice reforms, it will be critical to evaluate the intervention first to ensure the right objections are met, Dr. Jena added.

“At the end of the day, if the [legal] environment is such that it’s uncomfortable to practice medicine, that’s going to have implications for who goes into medicine and implications for ordering tests and procedures,” he said. “Any reform that attempts to make the process more efficient is a good idea because it lowers cost to the system and makes the experience better for patients and physicians.”

This article was updated 2/15/17.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Malpractice reforms long espoused by Thomas E. Price, MD, Health & Human Services secretary, are fostering debate on whether national fixes are necessary in an improving liability landscape. Claims against health providers have decreased twofold and doctors nationwide have seen their premiums decrease steadily for a decade. But the numbers tell just part of the story, liability experts say.

“Most health policy and medical malpractice scholars would not describe the environment we’re in right now as a state of crisis, at least not compared to what we observed a decade ago,” said Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, health care policy professor at Harvard University, Boston, and a medical liability researcher.“But I would argue that malpractice is still a salient fact for most physicians. What’s much more important than focusing on changes over time is taking a static perspective and understanding the risk that a physician faces when it comes to malpractice.”

During just over 12 years in Congress, Dr. Price (R-Ga.) has consistently advocated for tort reform, proposing legislation that would restructure the lawsuit process. He supports damage caps and has recommended the creation of health care tribunals that would hear cases only after medical review. He has also proposed the development of national practice guidelines for doctors, which if followed could be used defensively.

“From exorbitant malpractice insurance premiums to the remarkably expensive practice of defensive medicine, it is my experience that the current culture of litigation costs patients hundreds of billions of dollars,” Dr. Price wrote in a 2009 commentary about his Empowering Patients First Act. “These costs do nothing to provide better care, but rather serve only as a defense against unyielding personal injury lawyers ...When malpractice suits are brought through specialized courts and viewed through the perspective of medically appropriate care, rather than a lottery mentality, we will see a decline in frivolous lawsuits.”

Data show lawsuits down

Claims data however, show that lawsuits against doctors are on the decline – and have been for more than 10 years. The rate of paid claims against physicians dropped from 18.6 to 9.9 paid claims per 1,000 physicians between 2002 and 2013, according to 2014 study by Michelle Mello of Stanford (Calif.) University and colleagues (JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10705). Another analysis found that claims decreased from 12 claims per 100 doctors in 2003 to 6 per 100 doctors in 2016, according to a study of claims from The Doctors Company database.

The sharp decline in claims is directly affecting premiums, which have remained nearly unchanged for years, said Michael Matray, editor of the Medical Liability Monitor (MLM), which tracks premium rates. In 2003, rate increases of 49% were commonplace, he noted, with some states reporting rises of 100%. But premiums started to fall in 2006, he said.

“We are in the midst of a 10-year soft market, the longest we’ve ever had,” Mr. Matray said in an interview. “In 2006, we started to soften. We have been soft or flat with no change since. It’s definitely unprecedented.”

In 2016, U.S. internists paid an average premium of $15,853, compared to an average premium payment of $19,900 in 2006 without inflation adjustment, according to this news organization’s analysis of MLM data. General surgeons meanwhile, paid an average of $52,905 in premiums in 2016, compared to a 2006 average of $68,186. Ob.gyns. paid an average premium of $72,999 in 2016, a drop from $93,230 in 2006.

“Generally speaking, it’s great for doctors,” Mr. Matray said. “Even if you remove the inflationary factor, there are some states where they are paying less now than they were 10 years ago.”

But stable premiums do not mean inexpensive insurance, noted Mike Stinson, vice president of government relations and public policy for the PIAA, a national trade association for medical liability insurers.

“They’ve certainly come down over the last few years,” Mr. Stinson said in an interview. “But they certainly are not low.”

South Florida doctors for example, are paying among the highest premiums in the nation despite an overall drop in the last 10 years. Internists in Dade County, Fla., paid $47,707 for insurance in 2016, $27,000 less than in 2006, according to MLM data. Coverage is still is not affordable, said Jason M. Goldman, MD, an internist in private practice in Coral Springs, Fla., and governor for the American College of Physicians Florida chapter.

The premiums are ridiculous,” he said in an interview. “That’s one of the reasons I went bare. Having medical insurance makes you a target, because lawyers think, ‘We can sue the insurance company and the insurance company is going to pay.’ ”

State reforms driving lawsuit decline

A combination of state reforms and patient safety initiatives are fueling the lawsuit down slide, said Paul A. Greve Jr. senior vice president/senior consultant for Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice and coauthor of the 2016 MLM Survey report.

More than 25 states now have laws that enforce caps on noneconomic damages in medical liability cases, and in the last 15 years, a large majority have upheld such limits, Mr. Greve said. In addition, a number of states require a certificate of merit before suits can move forward, which mandate that a qualified physician verify that a defendant’s actions were likely negligent.

Patient safety programs such as internal patient safety committees, enhanced provider education, safety protocols, and communication and resolution programs, are also making an impact.

“There have been many efforts toward thinking innovatively about how we should be compensating patients more fairly and more quickly,” said Harvard’s Dr. Jena, who practices at Massachusetts General Hospital. “There are early disclosure programs that many hospitals have adopted as a movement toward that goal. The system is evolving.”

The high expense of filing a medical malpractice lawsuit is another factor detouring lawsuits, Mr. Greve added.

“It’s very expensive for [plaintiffs’ attorneys] to pursue these cases,” he said. “They have to invest a large amount of money into them and they can’t afford to take cases that have questionable liability, or they’re going to end up shelling out a lot of money and not getting anything in return.”

Malpractice system remains broken

While lawsuit and premium data paint a positive picture, the medical malpractice system remains dysfunctional for doctors and patients, said PIAA’s Mr. Stinson.

A majority of medical malpractice claims against physicians are determined to be nonmeritorious yet an average lawsuit takes roughly 4 years to resolve, he noted. Suits against doctors are dismissed by the court 54% of the time across all specialties, and among cases that go to trial, 80% end in the physician’s favor, according to a 2012 study by Dr. Jena and colleagues (JAMA Intern Med. 2012 Jun. 11 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2012.1416)

“We think that’s a huge amount of resources both in time and money and human capital to get poured into cases where no payment is ever deemed appropriate,” Mr. Stinson said. “We would like to see [malpractice] reforms in part because we think you can weed out some of these claims in advance, so more of the resources can be used to determine whether or not there was negligence and if so, making that patient whole as fast as possible.”

Regardless of declining claims, most physicians will still be sued in their lifetime, Dr. Jena said. By age 65, 75% of physicians in low-risk specialties have faced a malpractice claim, and 99% of doctors in high-risk specialties have been sued, according to a 2011 study by Dr. Jena and colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug. 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1012370)

“What really matters for physicians is not only whether they win or lose a malpractice suit, but whether they are sued in the first place,” Dr. Jena said. “Lawsuits happen quite often and over the course of a physician’s career they are quite common. So whether or not we’re in a state of malpractice crisis or not, the lifetime risk for physicians is quite real.”

The cost of defending claims continues to rise, noted Richard E. Anderson, MD, chair and CEO of The Doctors Company. At the same time, multi-million dollar malpractice verdicts have become more common.

“There’s still way too much malpractice litigation,” Dr. Anderson said. “The majority of it is fruitless, and the total cost burden borne by physicians has not decreased as much as the frequency because of the ongoing increase in severity.”

“The bottom line is defensive medicine is a huge and growing cost to all Americans,” he said. “We’re all on the hook for America’s rising health care bills. And as my increasingly infirm Baby Boomer generation gets older and weaker and sicker, those bills are going to rise that much faster. So the notion advanced by some so-called experts that we can nonetheless afford to spend a half trillion dollars a year or more on largely unnecessary testing driven in significant part by fear of litigation and giant outlier verdicts seems rather inane, and it suggests perhaps that those experts aren’t so expert.”

What would Dr. Price do?

Opinions are mixed about whether Dr. Price’s proposed reforms are the right changes for the medical liability system.

Expert panels to review claims for validity are a promising suggestion, Dr. Jena said. “Administrative courts to help identify malpractice cases that are truly malpractice early on is a good idea,” he said. “We want to have a system that prevents less meritorious cases from soaking up resources.”

But the idea may be easier said than done, said Dr. Anderson of The Doctors Company. “The devil is always in the details There is a lot of merit in [health courts] and they make a lot of sense. However, the notion of going from where we are today to an untested system, which would have to be a compromise between adversaries, would be a very challenging one.”

National clinical standards for physicians to follow and use as a safeguard could backfire, Mr. Stinson said. Bureaucracy could slow the guidelines from being promptly updated, and the standards could fail to keep up with the latest medical developments. As doctors know, medicine is not a one-size-fits-all approach, he added.

“[Guidelines] could encourage doctors to practice cookbook medicine, where they’re just going to follow the standard along without being given the opportunity to use their training and clinical experience to see whether that’s actually in the patient’s best interest,” Mr. Stinson said. “We certainly wouldn’t want to see a situation where a doctor feels diverting from a guidelines is in a patient’s best interest, but they don’t dare do it because it could subject them to a lawsuit.”

When enacting malpractice reforms, it will be critical to evaluate the intervention first to ensure the right objections are met, Dr. Jena added.

“At the end of the day, if the [legal] environment is such that it’s uncomfortable to practice medicine, that’s going to have implications for who goes into medicine and implications for ordering tests and procedures,” he said. “Any reform that attempts to make the process more efficient is a good idea because it lowers cost to the system and makes the experience better for patients and physicians.”

This article was updated 2/15/17.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med

Malpractice reforms long espoused by Thomas E. Price, MD, Health & Human Services secretary, are fostering debate on whether national fixes are necessary in an improving liability landscape. Claims against health providers have decreased twofold and doctors nationwide have seen their premiums decrease steadily for a decade. But the numbers tell just part of the story, liability experts say.

“Most health policy and medical malpractice scholars would not describe the environment we’re in right now as a state of crisis, at least not compared to what we observed a decade ago,” said Anupam B. Jena, MD, PhD, health care policy professor at Harvard University, Boston, and a medical liability researcher.“But I would argue that malpractice is still a salient fact for most physicians. What’s much more important than focusing on changes over time is taking a static perspective and understanding the risk that a physician faces when it comes to malpractice.”

During just over 12 years in Congress, Dr. Price (R-Ga.) has consistently advocated for tort reform, proposing legislation that would restructure the lawsuit process. He supports damage caps and has recommended the creation of health care tribunals that would hear cases only after medical review. He has also proposed the development of national practice guidelines for doctors, which if followed could be used defensively.

“From exorbitant malpractice insurance premiums to the remarkably expensive practice of defensive medicine, it is my experience that the current culture of litigation costs patients hundreds of billions of dollars,” Dr. Price wrote in a 2009 commentary about his Empowering Patients First Act. “These costs do nothing to provide better care, but rather serve only as a defense against unyielding personal injury lawyers ...When malpractice suits are brought through specialized courts and viewed through the perspective of medically appropriate care, rather than a lottery mentality, we will see a decline in frivolous lawsuits.”

Data show lawsuits down

Claims data however, show that lawsuits against doctors are on the decline – and have been for more than 10 years. The rate of paid claims against physicians dropped from 18.6 to 9.9 paid claims per 1,000 physicians between 2002 and 2013, according to 2014 study by Michelle Mello of Stanford (Calif.) University and colleagues (JAMA. 2014;312(20):2146-2155. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.10705). Another analysis found that claims decreased from 12 claims per 100 doctors in 2003 to 6 per 100 doctors in 2016, according to a study of claims from The Doctors Company database.

The sharp decline in claims is directly affecting premiums, which have remained nearly unchanged for years, said Michael Matray, editor of the Medical Liability Monitor (MLM), which tracks premium rates. In 2003, rate increases of 49% were commonplace, he noted, with some states reporting rises of 100%. But premiums started to fall in 2006, he said.

“We are in the midst of a 10-year soft market, the longest we’ve ever had,” Mr. Matray said in an interview. “In 2006, we started to soften. We have been soft or flat with no change since. It’s definitely unprecedented.”

In 2016, U.S. internists paid an average premium of $15,853, compared to an average premium payment of $19,900 in 2006 without inflation adjustment, according to this news organization’s analysis of MLM data. General surgeons meanwhile, paid an average of $52,905 in premiums in 2016, compared to a 2006 average of $68,186. Ob.gyns. paid an average premium of $72,999 in 2016, a drop from $93,230 in 2006.

“Generally speaking, it’s great for doctors,” Mr. Matray said. “Even if you remove the inflationary factor, there are some states where they are paying less now than they were 10 years ago.”

But stable premiums do not mean inexpensive insurance, noted Mike Stinson, vice president of government relations and public policy for the PIAA, a national trade association for medical liability insurers.

“They’ve certainly come down over the last few years,” Mr. Stinson said in an interview. “But they certainly are not low.”

South Florida doctors for example, are paying among the highest premiums in the nation despite an overall drop in the last 10 years. Internists in Dade County, Fla., paid $47,707 for insurance in 2016, $27,000 less than in 2006, according to MLM data. Coverage is still is not affordable, said Jason M. Goldman, MD, an internist in private practice in Coral Springs, Fla., and governor for the American College of Physicians Florida chapter.

The premiums are ridiculous,” he said in an interview. “That’s one of the reasons I went bare. Having medical insurance makes you a target, because lawyers think, ‘We can sue the insurance company and the insurance company is going to pay.’ ”

State reforms driving lawsuit decline

A combination of state reforms and patient safety initiatives are fueling the lawsuit down slide, said Paul A. Greve Jr. senior vice president/senior consultant for Willis Towers Watson Health Care Practice and coauthor of the 2016 MLM Survey report.

More than 25 states now have laws that enforce caps on noneconomic damages in medical liability cases, and in the last 15 years, a large majority have upheld such limits, Mr. Greve said. In addition, a number of states require a certificate of merit before suits can move forward, which mandate that a qualified physician verify that a defendant’s actions were likely negligent.

Patient safety programs such as internal patient safety committees, enhanced provider education, safety protocols, and communication and resolution programs, are also making an impact.

“There have been many efforts toward thinking innovatively about how we should be compensating patients more fairly and more quickly,” said Harvard’s Dr. Jena, who practices at Massachusetts General Hospital. “There are early disclosure programs that many hospitals have adopted as a movement toward that goal. The system is evolving.”

The high expense of filing a medical malpractice lawsuit is another factor detouring lawsuits, Mr. Greve added.

“It’s very expensive for [plaintiffs’ attorneys] to pursue these cases,” he said. “They have to invest a large amount of money into them and they can’t afford to take cases that have questionable liability, or they’re going to end up shelling out a lot of money and not getting anything in return.”

Malpractice system remains broken

While lawsuit and premium data paint a positive picture, the medical malpractice system remains dysfunctional for doctors and patients, said PIAA’s Mr. Stinson.

A majority of medical malpractice claims against physicians are determined to be nonmeritorious yet an average lawsuit takes roughly 4 years to resolve, he noted. Suits against doctors are dismissed by the court 54% of the time across all specialties, and among cases that go to trial, 80% end in the physician’s favor, according to a 2012 study by Dr. Jena and colleagues (JAMA Intern Med. 2012 Jun. 11 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2012.1416)

“We think that’s a huge amount of resources both in time and money and human capital to get poured into cases where no payment is ever deemed appropriate,” Mr. Stinson said. “We would like to see [malpractice] reforms in part because we think you can weed out some of these claims in advance, so more of the resources can be used to determine whether or not there was negligence and if so, making that patient whole as fast as possible.”

Regardless of declining claims, most physicians will still be sued in their lifetime, Dr. Jena said. By age 65, 75% of physicians in low-risk specialties have faced a malpractice claim, and 99% of doctors in high-risk specialties have been sued, according to a 2011 study by Dr. Jena and colleagues (N Engl J Med. 2011 Aug. 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1012370)

“What really matters for physicians is not only whether they win or lose a malpractice suit, but whether they are sued in the first place,” Dr. Jena said. “Lawsuits happen quite often and over the course of a physician’s career they are quite common. So whether or not we’re in a state of malpractice crisis or not, the lifetime risk for physicians is quite real.”

The cost of defending claims continues to rise, noted Richard E. Anderson, MD, chair and CEO of The Doctors Company. At the same time, multi-million dollar malpractice verdicts have become more common.

“There’s still way too much malpractice litigation,” Dr. Anderson said. “The majority of it is fruitless, and the total cost burden borne by physicians has not decreased as much as the frequency because of the ongoing increase in severity.”

“The bottom line is defensive medicine is a huge and growing cost to all Americans,” he said. “We’re all on the hook for America’s rising health care bills. And as my increasingly infirm Baby Boomer generation gets older and weaker and sicker, those bills are going to rise that much faster. So the notion advanced by some so-called experts that we can nonetheless afford to spend a half trillion dollars a year or more on largely unnecessary testing driven in significant part by fear of litigation and giant outlier verdicts seems rather inane, and it suggests perhaps that those experts aren’t so expert.”

What would Dr. Price do?

Opinions are mixed about whether Dr. Price’s proposed reforms are the right changes for the medical liability system.

Expert panels to review claims for validity are a promising suggestion, Dr. Jena said. “Administrative courts to help identify malpractice cases that are truly malpractice early on is a good idea,” he said. “We want to have a system that prevents less meritorious cases from soaking up resources.”

But the idea may be easier said than done, said Dr. Anderson of The Doctors Company. “The devil is always in the details There is a lot of merit in [health courts] and they make a lot of sense. However, the notion of going from where we are today to an untested system, which would have to be a compromise between adversaries, would be a very challenging one.”

National clinical standards for physicians to follow and use as a safeguard could backfire, Mr. Stinson said. Bureaucracy could slow the guidelines from being promptly updated, and the standards could fail to keep up with the latest medical developments. As doctors know, medicine is not a one-size-fits-all approach, he added.

“[Guidelines] could encourage doctors to practice cookbook medicine, where they’re just going to follow the standard along without being given the opportunity to use their training and clinical experience to see whether that’s actually in the patient’s best interest,” Mr. Stinson said. “We certainly wouldn’t want to see a situation where a doctor feels diverting from a guidelines is in a patient’s best interest, but they don’t dare do it because it could subject them to a lawsuit.”

When enacting malpractice reforms, it will be critical to evaluate the intervention first to ensure the right objections are met, Dr. Jena added.

“At the end of the day, if the [legal] environment is such that it’s uncomfortable to practice medicine, that’s going to have implications for who goes into medicine and implications for ordering tests and procedures,” he said. “Any reform that attempts to make the process more efficient is a good idea because it lowers cost to the system and makes the experience better for patients and physicians.”

This article was updated 2/15/17.

[email protected]

On Twitter @legal_med