User login

For patients with acute fulminant liver failure, imaging and histopathologic studies are indicated to reveal the underlying etiology, and metastatic small cell carcinoma should be included in the clinical differential diagnosis when appropriate.

Acute fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is an uncommon but highly fatal condition that results from the massive destruction of liver tissue. Viral hepatitis and drug-induced liver damage predominate in North America and Europe, but the underlying precipitating factors differ around the world.1 In children, indeterminate causes account for more than 50% of cases.2 Other conditions associated with FHF are Budd-Chiari syndrome, vascular hypoperfusion, mushroom poisoning, Wilson disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and fatty liver of pregnancy.3

Neoplastic lesions of the liver, mostly metastatic carcinomas, present with ductular obstruction with occasional mild elevations in aminotransferases. Rarely do space-occupying lesions lead to acute liver failure (ALF) with massive hepatocyte necrosis.

The authors report a case of rapidly progressing ALF due to metastatic small cell carcinoma to the liver. Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) is an aggressive tumor that often presents at an advanced stage. Although liver metastasis is common in this disease, development of FHF is extremely uncommon.

Case Presentation

A 90-year-old African American man presented to the emergency department (ED) of the Brooklyn Campus of the VA New York Harbor Health Care System (VANYHHS), with a persistent cough, worsening of shortness of breath, increasing right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and chronic constipation. He noted that he had smoked 1 pack per day for 40 years but quit 30 years ago. He had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, prostate cancer treated 20 years earlier with external beam radiation therapy and with intramuscular leuprolide every 6 months for the previous 6.5 years, and gout. He was taking no hepatotoxic prescription medications and never used over-the-counter analgesics or abused alcohol. Five days before admission, he was treated for COPD exacerbation in the ED.

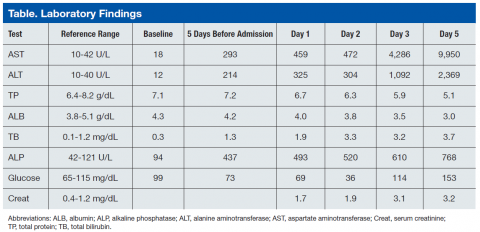

Blood chemistry at the time revealed significantly elevated liver function enzymes, including aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (AST), and total bilirubin compared with baseline levels taken 3 months earlier (Table). Primary care follow-up was recommended. Physical examination on the day of admission was remarkable for normal blood pressure (137/74), emaciated appearance, and a large liver with right upper quadrant tenderness.

Repeat blood chemistries showed a further rise in liver function tests. Acetaminophen level was < 1.0 μg/mL (therapeutic range 10-20 μg/mL). Hepatitis A, B, and C serologic testing was negative. Serum creatinine was elevated at 1.7 mg/dL and steadily increased to 3.2 mg/dL at the end of the hospital course. A chest X-ray and a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed left upper lobe ill-defined infiltrates/opacities. Noncontrast abdominal and pelvic CT revealed hepatomegaly and ascites. Hepatic ultrasound showed that the liver was enlarged, diffusely heterogeneous, and nodular in appearance. The patient was admitted for evaluation.

On day 2 of admission, the patient reported “numbness of digits.” Serum glucose was measured and found to be low (36 mg/dL) (reference range: 70-110 mg/dL). He was subsequently managed for refractory hypoglycemia, which was presumed to be a result of liver disease. On day 3, he was transferred to the intensive care unit for close monitoring and management. On day 4, the patient was still experiencing episodes of hypoglycemia despite glucagon and dextrose administration. He developed altered mental status and metabolic acidosis and was intubated. Repeat laboratory tests showed a significant increase in AST and ALT with an AST:ALT ratio of about 4. Serum ammonia levels also were increased at 198.6 μg/dL (reference range: 17-80 μg/dL). The platelet count decreased to as low as 86 x 103/μL (reference range:150-450 x 103/μL). The prothrombin time (PT) increased continuously to as high as 21.4 sec (reference range: 9.6-12.4 sec) as did the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) to 65.1 sec (reference range: 28-36.3 sec). Afterward, the patient developed multiple organ failure, including hemodynamic instability requiring fluid resuscitation. On day 5, the patient died.

At autopsy, the left upper lobe of the patient’s lung was found to have a tan-white, firm, irregularly shaped 4.8-cm mass. The liver weighed 2,980 g (reference range: 1,400-1,600 g) and was diffusely infiltrated by tan-white masses comprising about 70% of the liver (Figure 1).

Histologic examination of the lung (Figure 2) and liver (Figure 3) masses revealed small, round, blue cells with high nucleocytoplasmic ratios, nuclear molding, and crushing artifact. The tumor cells were found to be positive for chromogranin and synaptophysin. The liver showed diffuse hepatocyte necrosis with few viable hepatocytes present. The autopsy case was signed out as SCLC with diffuse liver metastasis.

Discussion

Acute FHF is a rare condition that often presents with sudden onset in which patients become encephalopathic due to hyperammonemia and exhibit marked elevations in the 2 aminotransferases, AST and ALT. A prior study of this condition reported on 6 patients, 5 of whom succumbed to the condition and 3 of whom were autopsied.4 The study found that both AST and ALT became rapidly elevated markedly such that the AST to ALT ratio was significantly greater than 1 and often exceeding 2, a pattern suggesting mitochondrial damage in hepatocytes resulting in release of intramitochondrial AST in addition to extramitochondrial AST.4

In addition, total protein and albumin were significantly decreased, and serum ammonia levels were markedly increased. All patients were encepaholopathic and were found to have disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Five of the 6 patients had renal failure, including 2 with acute tubular necrosis, and electrolyte abnormalities, including hypernatremia, in one case due to circulating elevated levels of aldosterone. Two of the 6 patients were found to be consistently hypoglycemic, possibly caused by impaired glycogenolysis. Three of these patients were found to have had lactic acidosis. In this study, liver biopsy was unrevealing and showed only minimal changes even during the earlier noted changes in laboratory values. Total hepatocyte necrosis was found only at postmortem examination.

Causes of FHF

Previous studies have identified possible causes of FHF that include alcohol abuse and IV drug abuse giving rise to pan-hepatic hepatitis—both conditions giving rise to cirrhosis; multiple abdominal surgeries; drug (acetaminophen) overdose; fatty liver of pregnancy resulting in microvesicular steatosis of hepatocytes; hypotension (shock liver); and Reye syndrome, mainly in children but also reported in adults, in which there is a viral prodrome with fever followed by treatment with aspirin that progresses to acute FHF.

Metastatic cancer is not generally listed as a potential cause of FHF. Although cancer is a less common cause of this condition, metastasis-induced FHF that has been documented in the literature includes tumors of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, nasopharynx, melanoma, and hematolymphoid malignancies, including leukemia, Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and malignant histiocytosis.5-12

Small Cell Carcinoma as a Cause of FHF

Small cell carcinoma of the lung is a highly malignant neoplasm that often presents at an advanced stage. Most often, metastatic disease to the liver may result in some mild increase in ALT and obstructive symptoms. However, diffuse sinusoidal infiltration of the tumor is most likely to present with hyperacute liver failure.13 A literature review of all small cell carcinomas in the liver presenting with acute FHF shows a consistent morphologic pattern of diffuse parenchymal infiltration,some that initially present with acute hepatic failure with no known history of liver disease.13-25 Imaging studies sometimes are difficult to interpret and may fail to detect infiltration of the tumor because of diffuse involvement of the liver parenchyma. Malignant infiltration of the liver should be one of the considerations in cases of unexplained hepatomegaly.

As found in the authors’ prior study, coagulopathy, renal failure (final creatinine was 3.2 mg/dL) as well as hypoglycemia are oftentimes seen, all of which were found in the patient in this study.4 (Coagulopathy was indicated by the low platelet count and elevated PT and aPTT.) Laboratory findings for FHF include rapid increases in serum ALTs such that the AST:ALT ratio is significantly greater than 1 and in which total protein and albumin are significantly decreased. Often there is hyperammonemia as was present in the current case.

A study has been performed to develop serodiagnostic markers to distinguish malignant from nonmalignant causes of FHF on 4 patients with tumor-induced FHF and 12 patients with FHF due to other causes. It was found that that there was an increase in the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to ALT ratio as well as elevated uric acid levels in the 4 patients with FHF not found in any of the 12 patients with nonmalignant causes of this condition.19 Although LDH was not measured in this case, in view of the patient’s history of gout, the LDH/uric acid ratio may not have been discriminating.

Conclusion

Although rare, metastatic small cell carcinoma should be included in the clinical differential diagnosis of patients presenting with acute FHF with no other obvious medical etiology. Accurate and timely diagnosis is important to better guide management of these patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Hoofnagle JH, Carithers RL Jr, Shapiro C, Ascher N. Fulminant hepatic failure: summary of workshop. Hepatology. 1995;21(1):240-252.

2. D’Agata ID, Balister WF. Pediatric aspects of acute liver failure. In: Lee WM, Williams R, eds. Acute Liver Failure. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997:53-66.

3. Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases position paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology. 2012;55(3):965-967.

4. Sunheimer R, Capaldo G, Kashanian F, et al. Serum analyte pattern characteristic of fulminant hepatic failure. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1994;24(2):101-109.

5. Athanasakis E, Mouloudi E, Prinianakis G, Kostaki M, Tzardi M, Georgopoulos D. Metastatic liver disease and fulminant hepatic failure: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15(11):1235-1240.

6. Preissler G, Graeb C, Steib C, et al. Acute liver failure, rupture and hemorrhagic shock as primary manifestation of advanced metastatic disease. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(8):3449-3454.

7. Alexopoulou A, Koskinas J, Deutsch M, Delladetsima J, Kountouras D, Dourakis SP. Acute liver failure as the initial manifestation of hepatic infiltration by a solid tumor: report of 5 cases and review of the literature. Tumori. 2006;92(4):354-357.

8. Shah KG, Modi PR, Rizvi J. Breast carcinoma metastasizing to the urinary bladder and retroperitoneum presenting as acute renal failure. Indian J Urol. 2011;27(1):135-136.

9. Nazario HE, Lepe R, Trotter JF. Metastatic breast cancer presenting as acute liver failure. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2011;7(1):65-66.

10. Rajvanshi P, Kowdley KV, Hirota WK, Meyers JB, Keeffe EB. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to neoplastic infiltration of the liver. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39(4):339-343.

11. Fairbank WH. Three atypical cases of Hodgkin’s Disease, presenting with liver failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1953;69(3):315-317.

12. Braude S, Portmann B, Gimson AE, Williams R. Fulminant hepatic failure in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Postgrad Med J. 1982;58(679):301-304.

13. Lo AA, Lo EC, Li H, et al. Unique morphologic and clinical features of liver predominant/primary small cell carcinoma—autopsy and biopsy case series. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18(3):151-156.

14. Hwang YT, Shin JW, Lee JH, et al. A case of fulminant hepatic failure secondary to hepatic metastasis of small cell lung carcinoma [in Korean]. Korean J Hepatol. 2007;13(4):565-570.

15. Miyaaki H, Ichikawa T, Taura N, et al. Diffuse liver metastasis of small cell lung cancer causing marked hepatomegaly and fulminant hepatic failure. Intern Med. 2010;49(14):1383-1386.

16. Sato K, Takeyama Y, Tanaka T, Fukui Y, Gonda H, Suzuki R. Fulminant hepatic failure and hepatomegaly caused by diffuse liver metastases from small cell lung carcinoma: 2 autopsy cases. Respir Investig. 2013;51(2):98-102.

17. Galus M. Liver failure due to metastatic small-cell carcinoma of the lung. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(8):791.

18. Kovalev Y, Lurie M, Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Zuckerman E. Metastatic small cell carcinoma presenting as acute hepatic failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(12):3471-3473.

19. McGuire BM, Cherwitz DL, Rabe KM, Ho SB. Small-cell carcinoma of the lung manifesting as acute hepatic failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(2):133-139.

20. Richecoeur M, Massoure MP, Le Coadou G, Lipovac AS, Bronstein JA, Delluc C. Acute hepatic failure as the presenting manifestation of a metastatic lung carcinoma to liver [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2009;30(10):911-913.

21. Valladares Ayerbes MJ, Canadas Garcia de Leon M, Reina Zoilo JJ, Valenzuela Claros JC, Ruiz Borrego M, Barea Bejarano JL. Acute liver failure as presentation form of small cell carcinoma of the lung [in Spanish]. An Med Interna. 1997;14(3):128-130.

22. Gilbert J, Rutledge H, Koch A. Diffuse malignant infiltration of the liver manifesting as a case of acute liver failure. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5(7):405-408.

23. Vaideeswar P, Munot S, Rojekar A, Deodhar K. Hepatic diffuse intra-sinusoidal metastases of pulmonary small-cell carcinoma. J Postgrad Med. 2012;58(3):230-231.

24. Krauss EA, Ludwig PW, Sumner HW. Metastatic carcinoma presenting as fulminant hepatic failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72(6):651-654.

25. Ke E, Gomez JD, Tang K, Sriram KB. Metastatic small-cell lung cancer presenting

as fulminant hepatic failure. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.

For patients with acute fulminant liver failure, imaging and histopathologic studies are indicated to reveal the underlying etiology, and metastatic small cell carcinoma should be included in the clinical differential diagnosis when appropriate.

Acute fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is an uncommon but highly fatal condition that results from the massive destruction of liver tissue. Viral hepatitis and drug-induced liver damage predominate in North America and Europe, but the underlying precipitating factors differ around the world.1 In children, indeterminate causes account for more than 50% of cases.2 Other conditions associated with FHF are Budd-Chiari syndrome, vascular hypoperfusion, mushroom poisoning, Wilson disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and fatty liver of pregnancy.3

Neoplastic lesions of the liver, mostly metastatic carcinomas, present with ductular obstruction with occasional mild elevations in aminotransferases. Rarely do space-occupying lesions lead to acute liver failure (ALF) with massive hepatocyte necrosis.

The authors report a case of rapidly progressing ALF due to metastatic small cell carcinoma to the liver. Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) is an aggressive tumor that often presents at an advanced stage. Although liver metastasis is common in this disease, development of FHF is extremely uncommon.

Case Presentation

A 90-year-old African American man presented to the emergency department (ED) of the Brooklyn Campus of the VA New York Harbor Health Care System (VANYHHS), with a persistent cough, worsening of shortness of breath, increasing right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and chronic constipation. He noted that he had smoked 1 pack per day for 40 years but quit 30 years ago. He had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, prostate cancer treated 20 years earlier with external beam radiation therapy and with intramuscular leuprolide every 6 months for the previous 6.5 years, and gout. He was taking no hepatotoxic prescription medications and never used over-the-counter analgesics or abused alcohol. Five days before admission, he was treated for COPD exacerbation in the ED.

Blood chemistry at the time revealed significantly elevated liver function enzymes, including aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (AST), and total bilirubin compared with baseline levels taken 3 months earlier (Table). Primary care follow-up was recommended. Physical examination on the day of admission was remarkable for normal blood pressure (137/74), emaciated appearance, and a large liver with right upper quadrant tenderness.

Repeat blood chemistries showed a further rise in liver function tests. Acetaminophen level was < 1.0 μg/mL (therapeutic range 10-20 μg/mL). Hepatitis A, B, and C serologic testing was negative. Serum creatinine was elevated at 1.7 mg/dL and steadily increased to 3.2 mg/dL at the end of the hospital course. A chest X-ray and a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed left upper lobe ill-defined infiltrates/opacities. Noncontrast abdominal and pelvic CT revealed hepatomegaly and ascites. Hepatic ultrasound showed that the liver was enlarged, diffusely heterogeneous, and nodular in appearance. The patient was admitted for evaluation.

On day 2 of admission, the patient reported “numbness of digits.” Serum glucose was measured and found to be low (36 mg/dL) (reference range: 70-110 mg/dL). He was subsequently managed for refractory hypoglycemia, which was presumed to be a result of liver disease. On day 3, he was transferred to the intensive care unit for close monitoring and management. On day 4, the patient was still experiencing episodes of hypoglycemia despite glucagon and dextrose administration. He developed altered mental status and metabolic acidosis and was intubated. Repeat laboratory tests showed a significant increase in AST and ALT with an AST:ALT ratio of about 4. Serum ammonia levels also were increased at 198.6 μg/dL (reference range: 17-80 μg/dL). The platelet count decreased to as low as 86 x 103/μL (reference range:150-450 x 103/μL). The prothrombin time (PT) increased continuously to as high as 21.4 sec (reference range: 9.6-12.4 sec) as did the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) to 65.1 sec (reference range: 28-36.3 sec). Afterward, the patient developed multiple organ failure, including hemodynamic instability requiring fluid resuscitation. On day 5, the patient died.

At autopsy, the left upper lobe of the patient’s lung was found to have a tan-white, firm, irregularly shaped 4.8-cm mass. The liver weighed 2,980 g (reference range: 1,400-1,600 g) and was diffusely infiltrated by tan-white masses comprising about 70% of the liver (Figure 1).

Histologic examination of the lung (Figure 2) and liver (Figure 3) masses revealed small, round, blue cells with high nucleocytoplasmic ratios, nuclear molding, and crushing artifact. The tumor cells were found to be positive for chromogranin and synaptophysin. The liver showed diffuse hepatocyte necrosis with few viable hepatocytes present. The autopsy case was signed out as SCLC with diffuse liver metastasis.

Discussion

Acute FHF is a rare condition that often presents with sudden onset in which patients become encephalopathic due to hyperammonemia and exhibit marked elevations in the 2 aminotransferases, AST and ALT. A prior study of this condition reported on 6 patients, 5 of whom succumbed to the condition and 3 of whom were autopsied.4 The study found that both AST and ALT became rapidly elevated markedly such that the AST to ALT ratio was significantly greater than 1 and often exceeding 2, a pattern suggesting mitochondrial damage in hepatocytes resulting in release of intramitochondrial AST in addition to extramitochondrial AST.4

In addition, total protein and albumin were significantly decreased, and serum ammonia levels were markedly increased. All patients were encepaholopathic and were found to have disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Five of the 6 patients had renal failure, including 2 with acute tubular necrosis, and electrolyte abnormalities, including hypernatremia, in one case due to circulating elevated levels of aldosterone. Two of the 6 patients were found to be consistently hypoglycemic, possibly caused by impaired glycogenolysis. Three of these patients were found to have had lactic acidosis. In this study, liver biopsy was unrevealing and showed only minimal changes even during the earlier noted changes in laboratory values. Total hepatocyte necrosis was found only at postmortem examination.

Causes of FHF

Previous studies have identified possible causes of FHF that include alcohol abuse and IV drug abuse giving rise to pan-hepatic hepatitis—both conditions giving rise to cirrhosis; multiple abdominal surgeries; drug (acetaminophen) overdose; fatty liver of pregnancy resulting in microvesicular steatosis of hepatocytes; hypotension (shock liver); and Reye syndrome, mainly in children but also reported in adults, in which there is a viral prodrome with fever followed by treatment with aspirin that progresses to acute FHF.

Metastatic cancer is not generally listed as a potential cause of FHF. Although cancer is a less common cause of this condition, metastasis-induced FHF that has been documented in the literature includes tumors of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, nasopharynx, melanoma, and hematolymphoid malignancies, including leukemia, Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and malignant histiocytosis.5-12

Small Cell Carcinoma as a Cause of FHF

Small cell carcinoma of the lung is a highly malignant neoplasm that often presents at an advanced stage. Most often, metastatic disease to the liver may result in some mild increase in ALT and obstructive symptoms. However, diffuse sinusoidal infiltration of the tumor is most likely to present with hyperacute liver failure.13 A literature review of all small cell carcinomas in the liver presenting with acute FHF shows a consistent morphologic pattern of diffuse parenchymal infiltration,some that initially present with acute hepatic failure with no known history of liver disease.13-25 Imaging studies sometimes are difficult to interpret and may fail to detect infiltration of the tumor because of diffuse involvement of the liver parenchyma. Malignant infiltration of the liver should be one of the considerations in cases of unexplained hepatomegaly.

As found in the authors’ prior study, coagulopathy, renal failure (final creatinine was 3.2 mg/dL) as well as hypoglycemia are oftentimes seen, all of which were found in the patient in this study.4 (Coagulopathy was indicated by the low platelet count and elevated PT and aPTT.) Laboratory findings for FHF include rapid increases in serum ALTs such that the AST:ALT ratio is significantly greater than 1 and in which total protein and albumin are significantly decreased. Often there is hyperammonemia as was present in the current case.

A study has been performed to develop serodiagnostic markers to distinguish malignant from nonmalignant causes of FHF on 4 patients with tumor-induced FHF and 12 patients with FHF due to other causes. It was found that that there was an increase in the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to ALT ratio as well as elevated uric acid levels in the 4 patients with FHF not found in any of the 12 patients with nonmalignant causes of this condition.19 Although LDH was not measured in this case, in view of the patient’s history of gout, the LDH/uric acid ratio may not have been discriminating.

Conclusion

Although rare, metastatic small cell carcinoma should be included in the clinical differential diagnosis of patients presenting with acute FHF with no other obvious medical etiology. Accurate and timely diagnosis is important to better guide management of these patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

For patients with acute fulminant liver failure, imaging and histopathologic studies are indicated to reveal the underlying etiology, and metastatic small cell carcinoma should be included in the clinical differential diagnosis when appropriate.

Acute fulminant hepatic failure (FHF) is an uncommon but highly fatal condition that results from the massive destruction of liver tissue. Viral hepatitis and drug-induced liver damage predominate in North America and Europe, but the underlying precipitating factors differ around the world.1 In children, indeterminate causes account for more than 50% of cases.2 Other conditions associated with FHF are Budd-Chiari syndrome, vascular hypoperfusion, mushroom poisoning, Wilson disease, autoimmune hepatitis, and fatty liver of pregnancy.3

Neoplastic lesions of the liver, mostly metastatic carcinomas, present with ductular obstruction with occasional mild elevations in aminotransferases. Rarely do space-occupying lesions lead to acute liver failure (ALF) with massive hepatocyte necrosis.

The authors report a case of rapidly progressing ALF due to metastatic small cell carcinoma to the liver. Small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC) is an aggressive tumor that often presents at an advanced stage. Although liver metastasis is common in this disease, development of FHF is extremely uncommon.

Case Presentation

A 90-year-old African American man presented to the emergency department (ED) of the Brooklyn Campus of the VA New York Harbor Health Care System (VANYHHS), with a persistent cough, worsening of shortness of breath, increasing right upper quadrant abdominal pain, and chronic constipation. He noted that he had smoked 1 pack per day for 40 years but quit 30 years ago. He had a medical history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), hypertension, prostate cancer treated 20 years earlier with external beam radiation therapy and with intramuscular leuprolide every 6 months for the previous 6.5 years, and gout. He was taking no hepatotoxic prescription medications and never used over-the-counter analgesics or abused alcohol. Five days before admission, he was treated for COPD exacerbation in the ED.

Blood chemistry at the time revealed significantly elevated liver function enzymes, including aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (AST), and total bilirubin compared with baseline levels taken 3 months earlier (Table). Primary care follow-up was recommended. Physical examination on the day of admission was remarkable for normal blood pressure (137/74), emaciated appearance, and a large liver with right upper quadrant tenderness.

Repeat blood chemistries showed a further rise in liver function tests. Acetaminophen level was < 1.0 μg/mL (therapeutic range 10-20 μg/mL). Hepatitis A, B, and C serologic testing was negative. Serum creatinine was elevated at 1.7 mg/dL and steadily increased to 3.2 mg/dL at the end of the hospital course. A chest X-ray and a noncontrast computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest showed left upper lobe ill-defined infiltrates/opacities. Noncontrast abdominal and pelvic CT revealed hepatomegaly and ascites. Hepatic ultrasound showed that the liver was enlarged, diffusely heterogeneous, and nodular in appearance. The patient was admitted for evaluation.

On day 2 of admission, the patient reported “numbness of digits.” Serum glucose was measured and found to be low (36 mg/dL) (reference range: 70-110 mg/dL). He was subsequently managed for refractory hypoglycemia, which was presumed to be a result of liver disease. On day 3, he was transferred to the intensive care unit for close monitoring and management. On day 4, the patient was still experiencing episodes of hypoglycemia despite glucagon and dextrose administration. He developed altered mental status and metabolic acidosis and was intubated. Repeat laboratory tests showed a significant increase in AST and ALT with an AST:ALT ratio of about 4. Serum ammonia levels also were increased at 198.6 μg/dL (reference range: 17-80 μg/dL). The platelet count decreased to as low as 86 x 103/μL (reference range:150-450 x 103/μL). The prothrombin time (PT) increased continuously to as high as 21.4 sec (reference range: 9.6-12.4 sec) as did the activated partial thromboplastin time (aPTT) to 65.1 sec (reference range: 28-36.3 sec). Afterward, the patient developed multiple organ failure, including hemodynamic instability requiring fluid resuscitation. On day 5, the patient died.

At autopsy, the left upper lobe of the patient’s lung was found to have a tan-white, firm, irregularly shaped 4.8-cm mass. The liver weighed 2,980 g (reference range: 1,400-1,600 g) and was diffusely infiltrated by tan-white masses comprising about 70% of the liver (Figure 1).

Histologic examination of the lung (Figure 2) and liver (Figure 3) masses revealed small, round, blue cells with high nucleocytoplasmic ratios, nuclear molding, and crushing artifact. The tumor cells were found to be positive for chromogranin and synaptophysin. The liver showed diffuse hepatocyte necrosis with few viable hepatocytes present. The autopsy case was signed out as SCLC with diffuse liver metastasis.

Discussion

Acute FHF is a rare condition that often presents with sudden onset in which patients become encephalopathic due to hyperammonemia and exhibit marked elevations in the 2 aminotransferases, AST and ALT. A prior study of this condition reported on 6 patients, 5 of whom succumbed to the condition and 3 of whom were autopsied.4 The study found that both AST and ALT became rapidly elevated markedly such that the AST to ALT ratio was significantly greater than 1 and often exceeding 2, a pattern suggesting mitochondrial damage in hepatocytes resulting in release of intramitochondrial AST in addition to extramitochondrial AST.4

In addition, total protein and albumin were significantly decreased, and serum ammonia levels were markedly increased. All patients were encepaholopathic and were found to have disseminated intravascular coagulopathy. Five of the 6 patients had renal failure, including 2 with acute tubular necrosis, and electrolyte abnormalities, including hypernatremia, in one case due to circulating elevated levels of aldosterone. Two of the 6 patients were found to be consistently hypoglycemic, possibly caused by impaired glycogenolysis. Three of these patients were found to have had lactic acidosis. In this study, liver biopsy was unrevealing and showed only minimal changes even during the earlier noted changes in laboratory values. Total hepatocyte necrosis was found only at postmortem examination.

Causes of FHF

Previous studies have identified possible causes of FHF that include alcohol abuse and IV drug abuse giving rise to pan-hepatic hepatitis—both conditions giving rise to cirrhosis; multiple abdominal surgeries; drug (acetaminophen) overdose; fatty liver of pregnancy resulting in microvesicular steatosis of hepatocytes; hypotension (shock liver); and Reye syndrome, mainly in children but also reported in adults, in which there is a viral prodrome with fever followed by treatment with aspirin that progresses to acute FHF.

Metastatic cancer is not generally listed as a potential cause of FHF. Although cancer is a less common cause of this condition, metastasis-induced FHF that has been documented in the literature includes tumors of the breast, gastrointestinal tract, lung, nasopharynx, melanoma, and hematolymphoid malignancies, including leukemia, Hodgkin disease, non-Hodgkin lymphomas, and malignant histiocytosis.5-12

Small Cell Carcinoma as a Cause of FHF

Small cell carcinoma of the lung is a highly malignant neoplasm that often presents at an advanced stage. Most often, metastatic disease to the liver may result in some mild increase in ALT and obstructive symptoms. However, diffuse sinusoidal infiltration of the tumor is most likely to present with hyperacute liver failure.13 A literature review of all small cell carcinomas in the liver presenting with acute FHF shows a consistent morphologic pattern of diffuse parenchymal infiltration,some that initially present with acute hepatic failure with no known history of liver disease.13-25 Imaging studies sometimes are difficult to interpret and may fail to detect infiltration of the tumor because of diffuse involvement of the liver parenchyma. Malignant infiltration of the liver should be one of the considerations in cases of unexplained hepatomegaly.

As found in the authors’ prior study, coagulopathy, renal failure (final creatinine was 3.2 mg/dL) as well as hypoglycemia are oftentimes seen, all of which were found in the patient in this study.4 (Coagulopathy was indicated by the low platelet count and elevated PT and aPTT.) Laboratory findings for FHF include rapid increases in serum ALTs such that the AST:ALT ratio is significantly greater than 1 and in which total protein and albumin are significantly decreased. Often there is hyperammonemia as was present in the current case.

A study has been performed to develop serodiagnostic markers to distinguish malignant from nonmalignant causes of FHF on 4 patients with tumor-induced FHF and 12 patients with FHF due to other causes. It was found that that there was an increase in the lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) to ALT ratio as well as elevated uric acid levels in the 4 patients with FHF not found in any of the 12 patients with nonmalignant causes of this condition.19 Although LDH was not measured in this case, in view of the patient’s history of gout, the LDH/uric acid ratio may not have been discriminating.

Conclusion

Although rare, metastatic small cell carcinoma should be included in the clinical differential diagnosis of patients presenting with acute FHF with no other obvious medical etiology. Accurate and timely diagnosis is important to better guide management of these patients.

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the U.S. Government, or any of its agencies. This article may discuss unlabeled or investigational use of certain drugs. Please review complete prescribing information for specific drugs or drug combinations—including indications, contraindications, warnings, and adverse effects—before administering pharmacologic therapy to patients.

Click here to read the digital edition.

1. Hoofnagle JH, Carithers RL Jr, Shapiro C, Ascher N. Fulminant hepatic failure: summary of workshop. Hepatology. 1995;21(1):240-252.

2. D’Agata ID, Balister WF. Pediatric aspects of acute liver failure. In: Lee WM, Williams R, eds. Acute Liver Failure. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997:53-66.

3. Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases position paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology. 2012;55(3):965-967.

4. Sunheimer R, Capaldo G, Kashanian F, et al. Serum analyte pattern characteristic of fulminant hepatic failure. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1994;24(2):101-109.

5. Athanasakis E, Mouloudi E, Prinianakis G, Kostaki M, Tzardi M, Georgopoulos D. Metastatic liver disease and fulminant hepatic failure: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15(11):1235-1240.

6. Preissler G, Graeb C, Steib C, et al. Acute liver failure, rupture and hemorrhagic shock as primary manifestation of advanced metastatic disease. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(8):3449-3454.

7. Alexopoulou A, Koskinas J, Deutsch M, Delladetsima J, Kountouras D, Dourakis SP. Acute liver failure as the initial manifestation of hepatic infiltration by a solid tumor: report of 5 cases and review of the literature. Tumori. 2006;92(4):354-357.

8. Shah KG, Modi PR, Rizvi J. Breast carcinoma metastasizing to the urinary bladder and retroperitoneum presenting as acute renal failure. Indian J Urol. 2011;27(1):135-136.

9. Nazario HE, Lepe R, Trotter JF. Metastatic breast cancer presenting as acute liver failure. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2011;7(1):65-66.

10. Rajvanshi P, Kowdley KV, Hirota WK, Meyers JB, Keeffe EB. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to neoplastic infiltration of the liver. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39(4):339-343.

11. Fairbank WH. Three atypical cases of Hodgkin’s Disease, presenting with liver failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1953;69(3):315-317.

12. Braude S, Portmann B, Gimson AE, Williams R. Fulminant hepatic failure in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Postgrad Med J. 1982;58(679):301-304.

13. Lo AA, Lo EC, Li H, et al. Unique morphologic and clinical features of liver predominant/primary small cell carcinoma—autopsy and biopsy case series. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18(3):151-156.

14. Hwang YT, Shin JW, Lee JH, et al. A case of fulminant hepatic failure secondary to hepatic metastasis of small cell lung carcinoma [in Korean]. Korean J Hepatol. 2007;13(4):565-570.

15. Miyaaki H, Ichikawa T, Taura N, et al. Diffuse liver metastasis of small cell lung cancer causing marked hepatomegaly and fulminant hepatic failure. Intern Med. 2010;49(14):1383-1386.

16. Sato K, Takeyama Y, Tanaka T, Fukui Y, Gonda H, Suzuki R. Fulminant hepatic failure and hepatomegaly caused by diffuse liver metastases from small cell lung carcinoma: 2 autopsy cases. Respir Investig. 2013;51(2):98-102.

17. Galus M. Liver failure due to metastatic small-cell carcinoma of the lung. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(8):791.

18. Kovalev Y, Lurie M, Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Zuckerman E. Metastatic small cell carcinoma presenting as acute hepatic failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(12):3471-3473.

19. McGuire BM, Cherwitz DL, Rabe KM, Ho SB. Small-cell carcinoma of the lung manifesting as acute hepatic failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(2):133-139.

20. Richecoeur M, Massoure MP, Le Coadou G, Lipovac AS, Bronstein JA, Delluc C. Acute hepatic failure as the presenting manifestation of a metastatic lung carcinoma to liver [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2009;30(10):911-913.

21. Valladares Ayerbes MJ, Canadas Garcia de Leon M, Reina Zoilo JJ, Valenzuela Claros JC, Ruiz Borrego M, Barea Bejarano JL. Acute liver failure as presentation form of small cell carcinoma of the lung [in Spanish]. An Med Interna. 1997;14(3):128-130.

22. Gilbert J, Rutledge H, Koch A. Diffuse malignant infiltration of the liver manifesting as a case of acute liver failure. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5(7):405-408.

23. Vaideeswar P, Munot S, Rojekar A, Deodhar K. Hepatic diffuse intra-sinusoidal metastases of pulmonary small-cell carcinoma. J Postgrad Med. 2012;58(3):230-231.

24. Krauss EA, Ludwig PW, Sumner HW. Metastatic carcinoma presenting as fulminant hepatic failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72(6):651-654.

25. Ke E, Gomez JD, Tang K, Sriram KB. Metastatic small-cell lung cancer presenting

as fulminant hepatic failure. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.

1. Hoofnagle JH, Carithers RL Jr, Shapiro C, Ascher N. Fulminant hepatic failure: summary of workshop. Hepatology. 1995;21(1):240-252.

2. D’Agata ID, Balister WF. Pediatric aspects of acute liver failure. In: Lee WM, Williams R, eds. Acute Liver Failure. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1997:53-66.

3. Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases position paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology. 2012;55(3):965-967.

4. Sunheimer R, Capaldo G, Kashanian F, et al. Serum analyte pattern characteristic of fulminant hepatic failure. Ann Clin Lab Sci. 1994;24(2):101-109.

5. Athanasakis E, Mouloudi E, Prinianakis G, Kostaki M, Tzardi M, Georgopoulos D. Metastatic liver disease and fulminant hepatic failure: presentation of a case and review of the literature. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2003;15(11):1235-1240.

6. Preissler G, Graeb C, Steib C, et al. Acute liver failure, rupture and hemorrhagic shock as primary manifestation of advanced metastatic disease. Anticancer Res. 2012;32(8):3449-3454.

7. Alexopoulou A, Koskinas J, Deutsch M, Delladetsima J, Kountouras D, Dourakis SP. Acute liver failure as the initial manifestation of hepatic infiltration by a solid tumor: report of 5 cases and review of the literature. Tumori. 2006;92(4):354-357.

8. Shah KG, Modi PR, Rizvi J. Breast carcinoma metastasizing to the urinary bladder and retroperitoneum presenting as acute renal failure. Indian J Urol. 2011;27(1):135-136.

9. Nazario HE, Lepe R, Trotter JF. Metastatic breast cancer presenting as acute liver failure. Gastroenterol Hepatol (NY). 2011;7(1):65-66.

10. Rajvanshi P, Kowdley KV, Hirota WK, Meyers JB, Keeffe EB. Fulminant hepatic failure secondary to neoplastic infiltration of the liver. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;39(4):339-343.

11. Fairbank WH. Three atypical cases of Hodgkin’s Disease, presenting with liver failure. Can Med Assoc J. 1953;69(3):315-317.

12. Braude S, Portmann B, Gimson AE, Williams R. Fulminant hepatic failure in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Postgrad Med J. 1982;58(679):301-304.

13. Lo AA, Lo EC, Li H, et al. Unique morphologic and clinical features of liver predominant/primary small cell carcinoma—autopsy and biopsy case series. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2014;18(3):151-156.

14. Hwang YT, Shin JW, Lee JH, et al. A case of fulminant hepatic failure secondary to hepatic metastasis of small cell lung carcinoma [in Korean]. Korean J Hepatol. 2007;13(4):565-570.

15. Miyaaki H, Ichikawa T, Taura N, et al. Diffuse liver metastasis of small cell lung cancer causing marked hepatomegaly and fulminant hepatic failure. Intern Med. 2010;49(14):1383-1386.

16. Sato K, Takeyama Y, Tanaka T, Fukui Y, Gonda H, Suzuki R. Fulminant hepatic failure and hepatomegaly caused by diffuse liver metastases from small cell lung carcinoma: 2 autopsy cases. Respir Investig. 2013;51(2):98-102.

17. Galus M. Liver failure due to metastatic small-cell carcinoma of the lung. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(8):791.

18. Kovalev Y, Lurie M, Naschitz JE, Yeshurun D, Zuckerman E. Metastatic small cell carcinoma presenting as acute hepatic failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(12):3471-3473.

19. McGuire BM, Cherwitz DL, Rabe KM, Ho SB. Small-cell carcinoma of the lung manifesting as acute hepatic failure. Mayo Clin Proc. 1997;72(2):133-139.

20. Richecoeur M, Massoure MP, Le Coadou G, Lipovac AS, Bronstein JA, Delluc C. Acute hepatic failure as the presenting manifestation of a metastatic lung carcinoma to liver [in French]. Rev Med Interne. 2009;30(10):911-913.

21. Valladares Ayerbes MJ, Canadas Garcia de Leon M, Reina Zoilo JJ, Valenzuela Claros JC, Ruiz Borrego M, Barea Bejarano JL. Acute liver failure as presentation form of small cell carcinoma of the lung [in Spanish]. An Med Interna. 1997;14(3):128-130.

22. Gilbert J, Rutledge H, Koch A. Diffuse malignant infiltration of the liver manifesting as a case of acute liver failure. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;5(7):405-408.

23. Vaideeswar P, Munot S, Rojekar A, Deodhar K. Hepatic diffuse intra-sinusoidal metastases of pulmonary small-cell carcinoma. J Postgrad Med. 2012;58(3):230-231.

24. Krauss EA, Ludwig PW, Sumner HW. Metastatic carcinoma presenting as fulminant hepatic failure. Am J Gastroenterol. 1979;72(6):651-654.

25. Ke E, Gomez JD, Tang K, Sriram KB. Metastatic small-cell lung cancer presenting

as fulminant hepatic failure. BMJ Case Rep. 2013;2013.