User login

From Grant Medical Center (Dr. Wasielewski, Dr. Polonia, Ms. Barca, Ms. Cebriak, Ms. Lucki), and OhioHealth Group (Mr. Rogers, Ms. St. John, Dr. Gascon), Columbus, OH.

Abstract

- Background: Organizations participating in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative enter into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care. There is growing evidence that the use of these payment incentives reduces spending for episodes of care while maintaining or improving quality. A recent study of BPCI and quality outcomes in joint replacement episodes found that nearly all the reduction in spending within BPCI hospitals was generated from the reduced use of institutional post-acute care (eg, skilled nursing facilities [SNF], long-term care facilities, and inpatient rehabilitation facilities).

- Objective: To describe a pilot program designed to reduce the utilization of institutional post-acute care for total joint replacement surgical patients.

- Methods: A multidisciplinary intervention team optimized scheduling, preadmission testing, patient communication, and patient education along a total joint replacement care pathway.

- Results: Among Medicare patients, total discharges to a SNF fell from 39.5% (70/177) in the baseline period to 17.7% (34/192) in the performance period. The risk of SNF utilization among patients in the intervention period was nearly half (0.45; 95% confidence interval, 0.314-0.639) that of patients in the baseline period. Using Fisher’s exact test and a 2-tailed test, this reduction was found to be significant (P < 0.0001). The readmission rate was substantially lower than national norms.

- Conclusion: Optimizing patient care throughout the care pathway using the concerted efforts of a multidisciplinary team is possible given a common vision, shared goals, and clearly communicated expectations.

Keywords: arthroplasty; readmissions; Medicare; post-acute care; Bundled Payment for Care Improvement.

Quality improvement in health care is partially dependent upon processes that standardize episodes of care. This is especially true in the post–acute care setting, where efforts to increase patient engagement and care coordination can improve a patient’s recovery process. One framework for optimizing patient care across an episode of care is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative, which links payments for the multiple services patients receive during an episode of care. Organizations participating in the BPCI initiative enter into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care. The BPCI initiative provides a framework for episodes of care across multiple types of facilities and clinicians over periods of time (30-day, 60-day, and 90-day episodes).1-5 Evidence that the use of these payment incentives reduces spending for episodes of care while maintaining or improving quality is accumulating. A recent study of BPCI and quality outcomes in joint replacement episodes found that nearly all the reduction in spending within BPCI hospitals was generated from the reduced use of institutional post-acute care, such as skilled nursing facilities (SNF), long-term care facilities, and inpatient rehabilitation facilities.1

Our hospital, the Grant Medical Center, which is part of the OhioHealth system, had agreed to participate in the CMS BPCI–Advanced Model for major joint replacement of the lower extremity, with a start date of October 1, 2018. Prior to adopting this bundled payment and service delivery model for major joint replacement through the BPCI program, we implemented strategic interventions to improve the efficiency of care delivery and reduce post-acute utilization. Although the BPCI program applied only to Medicare patients, the interventions that were developed, implemented, and evaluated in this quality improvement project, which we describe in this article, were provided to all patients who underwent lower-extremity joint replacement, regardless of payer.

Gap Analysis

Prior to developing and implementing the intervention, a gap analysis was performed to determine differences between Grant Medical Center’s care pathway/processes and evidence-based best practice. A steering committee comprised of physician champions, rehabilitation services, senior leadership from the Bone and Joint Center, and care management was gathered. The gap analysis examined the care paths in the preoperative phase, index admission phase, and the post-acute phase of care. Findings of the gap analysis included an underutilized joint education class, overutilization of SNF placement, and lack of key resources to assess the needs of patients prior to surgery.

The Grant Bone and Joint Center offered a comprehensive joint education class in person, but also gave patients the option of utilizing an online learning source. While both were successful, staff believed the in-person class had a greater impact than the online version. Patients who attended the class completed a preoperative assessment by hand, which included a social assessment for identifying potential challenges prior to admission. However, because class attendance was low (< 10%), this assessment tool was not utilized until the patient’s admission in most cases. The gap analysis also identified that the educational content of the class lacked key points to encourage a home-going plan.

The baseline SNF utilization rate (using data from July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016) within the Medicare population was 39.5% (70/177), with an overall (all payers) rate of 22.9% (192/838). This SNF utilization rate was higher than the national benchmark, underscoring the need to focus on a preoperative “plan for home” message. In addition, review of Medicare fee-for-service data from 2014 to 2016 revealed that Grant Medical Center utilized 83 different SNFs over the course of approximately 2 years. In this context, staff saw an opportunity to develop stronger relationships with fewer SNF partners, as well as OhioHealth Home Care, in order to improve care by standardizing functional recovery in post-acute care management.

In sum, the gap analysis found that a lack of standardization, follow through, and engagement in daily multidisciplinary rounds often led to a plan for SNF discharge instead of home. As such, it was determined that the pilot program would target the preoperative and post-acute phases of care and that its primary endpoint would be the reduction of the SNF discharge rate among Medicare fee-for-service patients.

Literature Review

Targeting the SNF discharge rate as the endpoint was also supported by a recent study that showed that most of the reduction in spending for total joint replacement within BPCI hospitals was linked to reduced use of institutional post-acute care.1 Other studies in the joint replacement literature have delineated the specific aspects of care redesign that allow hospitals to provide more efficient and effective care delivery during an episode of care.6-8 A review of these and similar studies of joint replacement quality improvement interventions yielded a number of actionable findings:

- Engaging and educating patients and families is critical. Families and other caregivers must be identified preoperatively, actively engaged, and committed to helping the patient recover.

- Providers must build the expectation in patients that they will return home as soon as it is safe to do so. This includes working to restore physiologic function, managing pain with oral medication, and restoring the physical capability of adapting to a home environment.

- Relationships must be established with post-acute care providers who are able to demonstrate best practices and be willing partners on performance outcomes.

- Providers need to invest in personnel to coordinate care transitions initiated preoperatively that continue through the post-acute phase of care.

- Providers must promote processes that allow patients to more fully own their recovery through coaching and improved communication.

A total joint replacement initiative undertaken at another hospital within the OhioHealth system, Riverside Methodist Hospital, that incorporated these aspects of care redesign demonstrated a significant reduction in SNF utilization. That success informed the development of the initiative at Grant Medical Center.

Methods

Setting

This pilot project was conducted from July 2017 through July 2018 at the Grant Bone and Joint Center in the Grant Medical Center, an urban hospital in Columbus, Ohio. The Bone and Joint Center performs more than 7400 surgeries each year, of which 12% are total joint replacements. Grant Medical Center is a Level I Trauma Center that has received a fourth designation in Magnet Nursing status and has attained The Joint Commission Disease-Specific Care Certification for its total knee and hip arthroplasty, total shoulder, and hip fracture programs.

Intervention

The findings from the gap analysis were incorporated into a standardized preoperative care pathway at the Center. Standardization of the care pathway required developing relationships between office staff, schedulers, inpatient work teams, and preadmission testing, as well as physician group realignment with the larger organization.

During this time, the steering committee identified the need for a designated full-time pre-habilitation case manager to support patients undergoing hip and knee replacements at the Center. With the addition of a new role, prehab case manager, attention was directed to patient social assessment and communication. After the surgery was scheduled but prior to the preoperative education class, each patient received a screening phone call from the prehab case manager that included an initial social assessment. The electronic health record (EHR) was utilized to communicate the results of the assessment, including barriers to a home-going plan. The phone call allowed the case manager to reinforce the importance of class attendance for the patient and primary caregiver, and also allowed any specific concerns identified to be addressed and resolved prior to surgery.

A work group consisting of the prehab case manager, office staff, and the bone and joint leadership team focused on improving the core preoperative education content, same-day preadmission clearance, and class attendance. To support these efforts, the work group (1) created a scheduling document to align preadmission testing and the preoperative education class so they occurred on the same day, (2) improved prior authorization of the surgery to support the post-surgical care team, (3) clarified expectations and roles among office staff and care management staff to optimize the discharge process, and (4) engaged the physician team to encourage a culture change towards setting patient expectations to be discharged to home or a preferred SNF location. Regarding prior authorization communications, prior to the intervention, communication was insufficient, paper driven, and lacking in continuity. Utilizing the EHR, an EPIC platform, a designated documentation location was created, which increased communication among the office schedulers, preadmission testing, and surgery schedulers. The consistent location for recording prior authorization avoided canceled surgeries and claim denials due to missing pieces of information. In addition to these process changes, the surgical offices were geographically realigned to a new single location, a change that brought the staff together and in turn allowed for role clarification and team building and also allowed the staff to identify opportunities for improvement.

The core content of the education class was redesigned to support patients’ understanding of the procedure and what to expect during the hospital stay and discharge for home. Staff worked first to align all preadmission patient requirements with the content of the class. In pilot studies, patients were asked to provide feedback, and this feedback was incorporated into subsequent revisions. Staff developed multilingual handouts, including a surgery instruction sheet with a preoperative social assessment, in addition to creating opportunities for 1:1 education when it was medically or socially appropriate.

The work group brought the physicians in the care pathway together for a focused conversation and education regarding the need for including class attendance as part of their practice. They worked with the physicians’ support team to coordinate standardized follow-up care in the post-acute setting and encouraged the physicians to create a “home-going” culture and reset expectations for length of stay. Prior to the start of this project, the rehabilitation department began using the 6-Clicks Inpatient Basic Mobility Short Form, a standardized instrument comprised of short forms created from the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) instrument. The AMPAC score is used to help establish the patient’s functional level; patients scoring 18 or higher have a higher probability of a successful return home (rather than an institutional discharge). Physical therapists at the Center adminster the 6-Clicks tool for each therapy patient daily, and document the AM-PAC score in the appropriate flowsheet in the EHR in a manner consistent with best practices.9-11 The group utilized the AMPAC score to determine functional status upon discharge, offering guidance for the correct post-acute discharge plan.

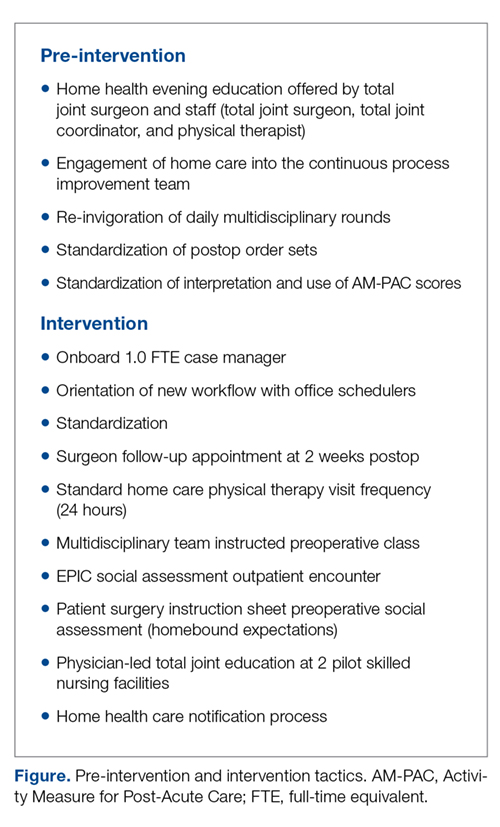

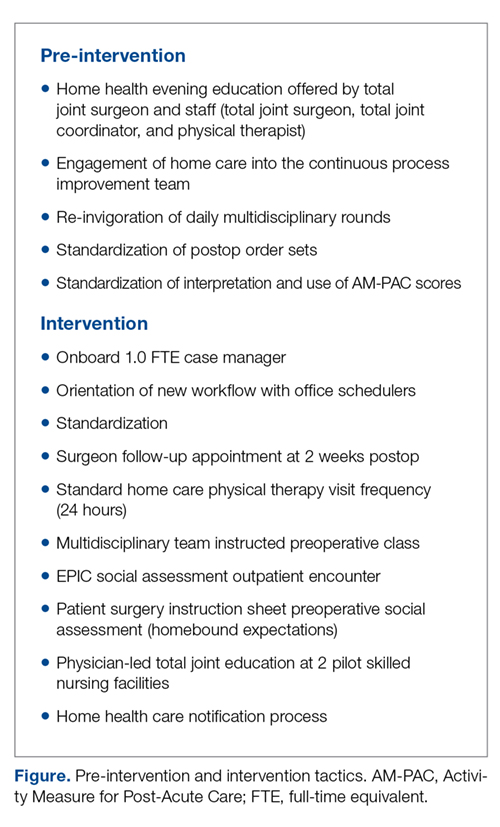

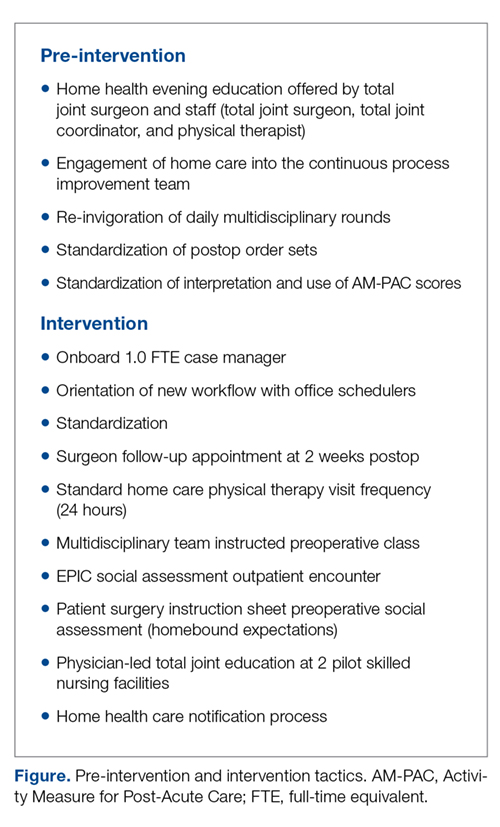

The workgroup also established a relationship with the lead home health care service to develop a standard notification process to set volume and service expectations. Finally, they worked with the lead SNFs to explain the surgical procedure and set expectations for patient recovery at the facilities. These changes are summarized in the Figure.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe patients and metrics in the baseline and performance periods. The difference in the proportion of patients discharged to a SNF in the baseline and performance periods was examined by a Z-test of proportion and change in relative risk. A Z-test of proportion was also used examine differences in the 90-day all-cause readmission rate and in the average length of stay between the 2 periods.

Results

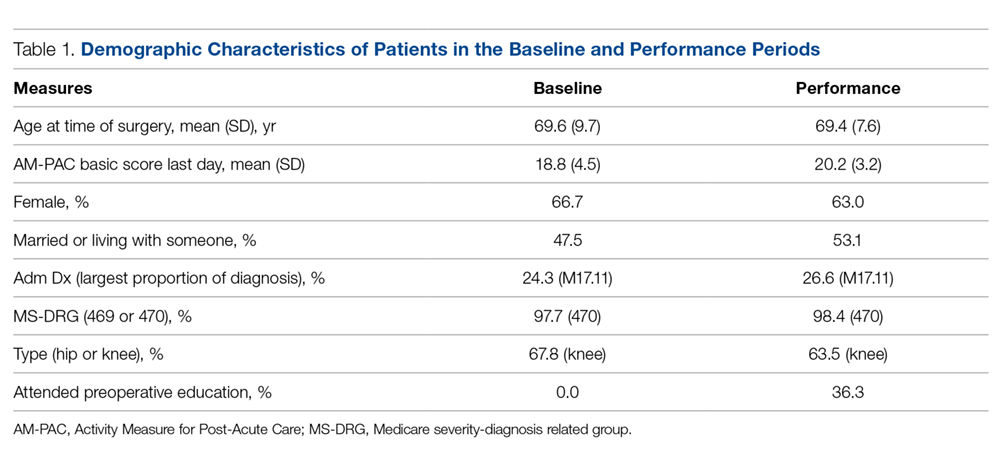

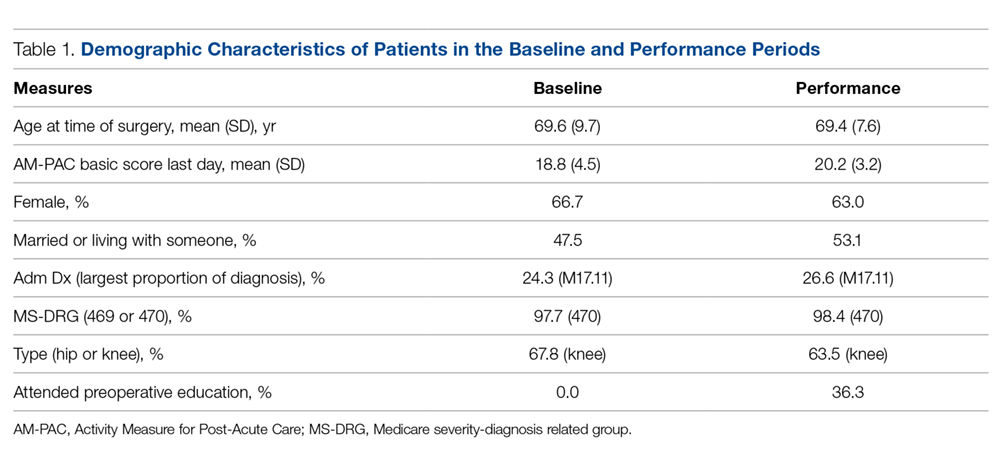

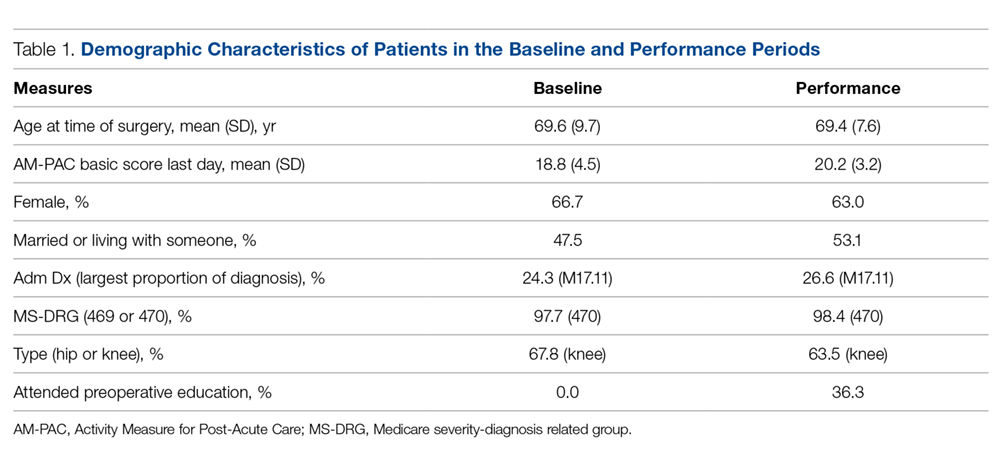

Differences between Medicare fee-for-service patients in the baseline and performance periods are reported in Table 1. While age, sex, diagnoses, and surgical types were similar, AM-PAC scores and the proportion of patients married or living with someone were higher in the performance period. The AM-PAC score in Table 1 represents the last documented score prior to discharge.

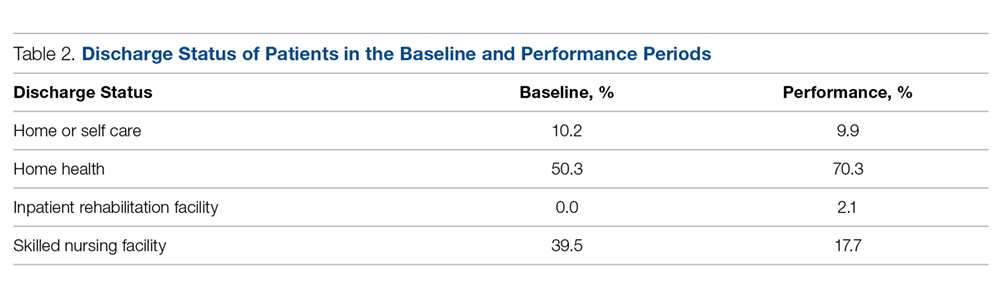

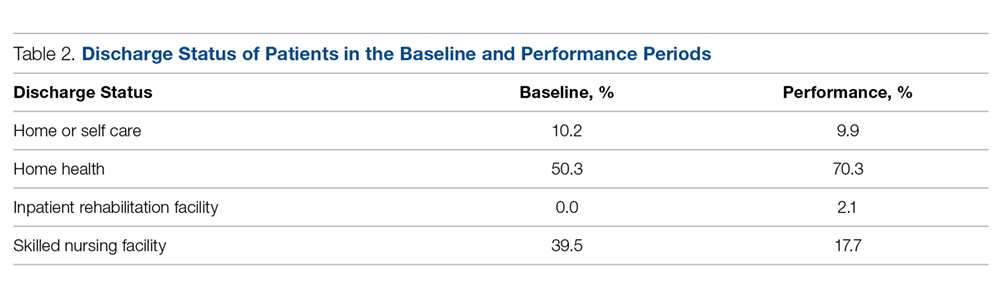

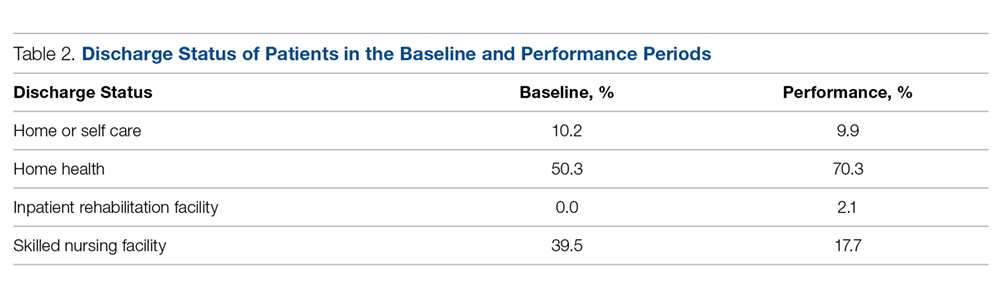

The proportion of Medicare patients discharged to a SNF fell from 39.5% (70/177) in the baseline period to 17.7% (34/192) in the performance period (Table 2). The 21.9% difference was significant at the 0.05 level (Z = 4.6586, P = 0.0001). Medicare patients in the intervention period had nearly half (0.45) the risk (95% confidence interval, 0.314-0.639) of SNF utilization compared with patients in the baseline period. Using Fisher’s exact test and a 2-tailed test, this reduction was found to be significant (P < 0.0001).

Concomitantly, the 90-day all-cause readmission rate among Medicare patients rose from 2.8% (5/177) to 4.7% (9/192), but the difference in proportions was not statistically significant (Z = –0.9356, P = 0.3495). Similarly, the average length of stay for Medicare patients was 2.9 days in both the baseline and performance periods.

Discussion

The intervention was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the SNF discharge rate following total joint replacement. The readmission rate and average length of stay were statistically unchanged. The lack of a statistically significant change in readmissions is important, as previous research has found that total joint replacement patients discharged to a SNF have higher odds of hospital readmission within 90 days than those discharged home.12 Moreover, the readmission rate in the performance period (4.7%) was still substantially lower than the national estimate of 90-day readmission rates associated with total hip arthroplasty (7.7%) and total knee arthroplasty (9.7%).13 For patients, these quality improvements are associated with improved outcomes and lower costs of care.

These outcomes were achieved after a substantial effort at the facility level to onboard new staff; orient them and their colleagues in each step along the care pathway, from scheduling through post-acute care; and build trust among all team members. The critical difference was changing expectations for post-acute recovery and rehabilitation throughout both the new clinical coordination workflow and processes and the existing processes. Orientation of the clinical coordination role was necessary to establish relationships with inpatient team members who were not as intimately involved with the position and expectations. To accomplish this, competing priorities had to be addressed and resolved through standardization efforts developed and implemented by the multidisciplinary team. The team first reviewed reports of such efforts in the initial review of the BPCI literature.1-5 Subsequent analyses of the most germane study3 and related research14 confirmed that a team-based approach to standardization could be successful. The former study used physician and affiliated care teams to build a care pathway that minimized variation in practices across the episode of care, and the latter used a multidisciplinary team approach to develop rapid recovery protocols. Subsequent research has validated the findings that hospital-based multidisciplinary teams have long been associated with improved patient safety, shorter length of stay, and fewer complications.15

Limitations

This quality improvement project was limited to a single facility. As such, adapting the improvements made to Grant Medical Center’s care pathway for implementation throughout the OhioHealth system will take time due to variation of care provided at each campus; scale-up efforts are ongoing. In the Grant facility, the project uncovered instances of unstandardized provider communication pathways, clinical staff workflows, and expectations for patients. Standardization in all 3 instances improved the patient experience. Additionally, data collection requirements for rigorous research and evaluation efforts that had to be done by hand during the project are now being integrated into the EHR.

The improvements described here, which were implemented in anticipation of adopting the CMS BPCI bundled payment model for joint replacement of the lower extremity, were provided to every patient regardless of payer. Patient outcomes varied across payer, as did preoperative education rates and other variables (Table 1). These differences are being tracked and analyzed following the Center’s entry into the CMS BPCI model on October 1, 2018.

Corresponding author: Gregg M. Gascon, PhD, CHDA, OhioHealth Group, 155 E. Broad Street, Suite 1700, Columbus, Ohio 43215; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316:1267-1278.

2. Urdapilleta O, Weinberg D, Pedersen S, et al. Evaluation of the Medicare Acute Care Episodes (ACE) demonstration: final evaluation report. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. May 31, 2013. http://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/ACE-EvaluationReport-Final-5-2-14.pdf.

3. Froemke C, Wang L, DeHart ML, et al. Standardizing care and improving quality under a bundled payment initiative for total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:1676-1682.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. (2015 Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. New Release. January 26, 2015.

5. Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Wild RC, et al. Medicare’s Bundled Payment Initiatives: most hospitals are focused on a few high-volume conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34;371-380.

6. Mechanic RE. Opportunities and challenges for episode-based payment. N Engl J Med. 2011,365:777-779.

7. Mallinson TR, Bateman J, Tseng HY, et al. A comparison of discharge functional status after rehabilitation in skilled nursing, home health, and medical rehabilitation settings for patients after lower-extremity joint replacement surgery. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011:92:712-720.

8. Froimson M, Deadwiller M, Schill M, Cousineau K. Early results of a total joint bundled payment program: the BPCI initiative. Poster No. 2026. Poster presented at Orthopaedic Research Society Annual Meeting; March 15-18, 2014; New Orleans, LA.

9. Haley SM, Coster WJ, Andres PL, et al. Activity outcome measurement for postacute care. Med Care. 2004;42(1 Suppl):S49-S61.

10. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94;379-391.

11. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1252-1261.

12. Bini SA, Fithian DC, Paxton LW, et al. Does discharge disposition after primary total joint arthroplasty affect readmission rates? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:114-117.

13. Ramkumar PN, Chu CT, Harris JD, et al. Causes and rates of unplanned readmissions after elective primary total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthop. 2015;44:397-405.

14. Klingenstein GG, Schoifet SD, Jain RK, et al. Rapid discharge to home after total knee arthroplasty is safe in eligible Medicare patients. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:3308-3313.

15. Epstein NE. Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: A review. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(Suppl 7):S295-S303.

From Grant Medical Center (Dr. Wasielewski, Dr. Polonia, Ms. Barca, Ms. Cebriak, Ms. Lucki), and OhioHealth Group (Mr. Rogers, Ms. St. John, Dr. Gascon), Columbus, OH.

Abstract

- Background: Organizations participating in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative enter into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care. There is growing evidence that the use of these payment incentives reduces spending for episodes of care while maintaining or improving quality. A recent study of BPCI and quality outcomes in joint replacement episodes found that nearly all the reduction in spending within BPCI hospitals was generated from the reduced use of institutional post-acute care (eg, skilled nursing facilities [SNF], long-term care facilities, and inpatient rehabilitation facilities).

- Objective: To describe a pilot program designed to reduce the utilization of institutional post-acute care for total joint replacement surgical patients.

- Methods: A multidisciplinary intervention team optimized scheduling, preadmission testing, patient communication, and patient education along a total joint replacement care pathway.

- Results: Among Medicare patients, total discharges to a SNF fell from 39.5% (70/177) in the baseline period to 17.7% (34/192) in the performance period. The risk of SNF utilization among patients in the intervention period was nearly half (0.45; 95% confidence interval, 0.314-0.639) that of patients in the baseline period. Using Fisher’s exact test and a 2-tailed test, this reduction was found to be significant (P < 0.0001). The readmission rate was substantially lower than national norms.

- Conclusion: Optimizing patient care throughout the care pathway using the concerted efforts of a multidisciplinary team is possible given a common vision, shared goals, and clearly communicated expectations.

Keywords: arthroplasty; readmissions; Medicare; post-acute care; Bundled Payment for Care Improvement.

Quality improvement in health care is partially dependent upon processes that standardize episodes of care. This is especially true in the post–acute care setting, where efforts to increase patient engagement and care coordination can improve a patient’s recovery process. One framework for optimizing patient care across an episode of care is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative, which links payments for the multiple services patients receive during an episode of care. Organizations participating in the BPCI initiative enter into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care. The BPCI initiative provides a framework for episodes of care across multiple types of facilities and clinicians over periods of time (30-day, 60-day, and 90-day episodes).1-5 Evidence that the use of these payment incentives reduces spending for episodes of care while maintaining or improving quality is accumulating. A recent study of BPCI and quality outcomes in joint replacement episodes found that nearly all the reduction in spending within BPCI hospitals was generated from the reduced use of institutional post-acute care, such as skilled nursing facilities (SNF), long-term care facilities, and inpatient rehabilitation facilities.1

Our hospital, the Grant Medical Center, which is part of the OhioHealth system, had agreed to participate in the CMS BPCI–Advanced Model for major joint replacement of the lower extremity, with a start date of October 1, 2018. Prior to adopting this bundled payment and service delivery model for major joint replacement through the BPCI program, we implemented strategic interventions to improve the efficiency of care delivery and reduce post-acute utilization. Although the BPCI program applied only to Medicare patients, the interventions that were developed, implemented, and evaluated in this quality improvement project, which we describe in this article, were provided to all patients who underwent lower-extremity joint replacement, regardless of payer.

Gap Analysis

Prior to developing and implementing the intervention, a gap analysis was performed to determine differences between Grant Medical Center’s care pathway/processes and evidence-based best practice. A steering committee comprised of physician champions, rehabilitation services, senior leadership from the Bone and Joint Center, and care management was gathered. The gap analysis examined the care paths in the preoperative phase, index admission phase, and the post-acute phase of care. Findings of the gap analysis included an underutilized joint education class, overutilization of SNF placement, and lack of key resources to assess the needs of patients prior to surgery.

The Grant Bone and Joint Center offered a comprehensive joint education class in person, but also gave patients the option of utilizing an online learning source. While both were successful, staff believed the in-person class had a greater impact than the online version. Patients who attended the class completed a preoperative assessment by hand, which included a social assessment for identifying potential challenges prior to admission. However, because class attendance was low (< 10%), this assessment tool was not utilized until the patient’s admission in most cases. The gap analysis also identified that the educational content of the class lacked key points to encourage a home-going plan.

The baseline SNF utilization rate (using data from July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016) within the Medicare population was 39.5% (70/177), with an overall (all payers) rate of 22.9% (192/838). This SNF utilization rate was higher than the national benchmark, underscoring the need to focus on a preoperative “plan for home” message. In addition, review of Medicare fee-for-service data from 2014 to 2016 revealed that Grant Medical Center utilized 83 different SNFs over the course of approximately 2 years. In this context, staff saw an opportunity to develop stronger relationships with fewer SNF partners, as well as OhioHealth Home Care, in order to improve care by standardizing functional recovery in post-acute care management.

In sum, the gap analysis found that a lack of standardization, follow through, and engagement in daily multidisciplinary rounds often led to a plan for SNF discharge instead of home. As such, it was determined that the pilot program would target the preoperative and post-acute phases of care and that its primary endpoint would be the reduction of the SNF discharge rate among Medicare fee-for-service patients.

Literature Review

Targeting the SNF discharge rate as the endpoint was also supported by a recent study that showed that most of the reduction in spending for total joint replacement within BPCI hospitals was linked to reduced use of institutional post-acute care.1 Other studies in the joint replacement literature have delineated the specific aspects of care redesign that allow hospitals to provide more efficient and effective care delivery during an episode of care.6-8 A review of these and similar studies of joint replacement quality improvement interventions yielded a number of actionable findings:

- Engaging and educating patients and families is critical. Families and other caregivers must be identified preoperatively, actively engaged, and committed to helping the patient recover.

- Providers must build the expectation in patients that they will return home as soon as it is safe to do so. This includes working to restore physiologic function, managing pain with oral medication, and restoring the physical capability of adapting to a home environment.

- Relationships must be established with post-acute care providers who are able to demonstrate best practices and be willing partners on performance outcomes.

- Providers need to invest in personnel to coordinate care transitions initiated preoperatively that continue through the post-acute phase of care.

- Providers must promote processes that allow patients to more fully own their recovery through coaching and improved communication.

A total joint replacement initiative undertaken at another hospital within the OhioHealth system, Riverside Methodist Hospital, that incorporated these aspects of care redesign demonstrated a significant reduction in SNF utilization. That success informed the development of the initiative at Grant Medical Center.

Methods

Setting

This pilot project was conducted from July 2017 through July 2018 at the Grant Bone and Joint Center in the Grant Medical Center, an urban hospital in Columbus, Ohio. The Bone and Joint Center performs more than 7400 surgeries each year, of which 12% are total joint replacements. Grant Medical Center is a Level I Trauma Center that has received a fourth designation in Magnet Nursing status and has attained The Joint Commission Disease-Specific Care Certification for its total knee and hip arthroplasty, total shoulder, and hip fracture programs.

Intervention

The findings from the gap analysis were incorporated into a standardized preoperative care pathway at the Center. Standardization of the care pathway required developing relationships between office staff, schedulers, inpatient work teams, and preadmission testing, as well as physician group realignment with the larger organization.

During this time, the steering committee identified the need for a designated full-time pre-habilitation case manager to support patients undergoing hip and knee replacements at the Center. With the addition of a new role, prehab case manager, attention was directed to patient social assessment and communication. After the surgery was scheduled but prior to the preoperative education class, each patient received a screening phone call from the prehab case manager that included an initial social assessment. The electronic health record (EHR) was utilized to communicate the results of the assessment, including barriers to a home-going plan. The phone call allowed the case manager to reinforce the importance of class attendance for the patient and primary caregiver, and also allowed any specific concerns identified to be addressed and resolved prior to surgery.

A work group consisting of the prehab case manager, office staff, and the bone and joint leadership team focused on improving the core preoperative education content, same-day preadmission clearance, and class attendance. To support these efforts, the work group (1) created a scheduling document to align preadmission testing and the preoperative education class so they occurred on the same day, (2) improved prior authorization of the surgery to support the post-surgical care team, (3) clarified expectations and roles among office staff and care management staff to optimize the discharge process, and (4) engaged the physician team to encourage a culture change towards setting patient expectations to be discharged to home or a preferred SNF location. Regarding prior authorization communications, prior to the intervention, communication was insufficient, paper driven, and lacking in continuity. Utilizing the EHR, an EPIC platform, a designated documentation location was created, which increased communication among the office schedulers, preadmission testing, and surgery schedulers. The consistent location for recording prior authorization avoided canceled surgeries and claim denials due to missing pieces of information. In addition to these process changes, the surgical offices were geographically realigned to a new single location, a change that brought the staff together and in turn allowed for role clarification and team building and also allowed the staff to identify opportunities for improvement.

The core content of the education class was redesigned to support patients’ understanding of the procedure and what to expect during the hospital stay and discharge for home. Staff worked first to align all preadmission patient requirements with the content of the class. In pilot studies, patients were asked to provide feedback, and this feedback was incorporated into subsequent revisions. Staff developed multilingual handouts, including a surgery instruction sheet with a preoperative social assessment, in addition to creating opportunities for 1:1 education when it was medically or socially appropriate.

The work group brought the physicians in the care pathway together for a focused conversation and education regarding the need for including class attendance as part of their practice. They worked with the physicians’ support team to coordinate standardized follow-up care in the post-acute setting and encouraged the physicians to create a “home-going” culture and reset expectations for length of stay. Prior to the start of this project, the rehabilitation department began using the 6-Clicks Inpatient Basic Mobility Short Form, a standardized instrument comprised of short forms created from the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) instrument. The AMPAC score is used to help establish the patient’s functional level; patients scoring 18 or higher have a higher probability of a successful return home (rather than an institutional discharge). Physical therapists at the Center adminster the 6-Clicks tool for each therapy patient daily, and document the AM-PAC score in the appropriate flowsheet in the EHR in a manner consistent with best practices.9-11 The group utilized the AMPAC score to determine functional status upon discharge, offering guidance for the correct post-acute discharge plan.

The workgroup also established a relationship with the lead home health care service to develop a standard notification process to set volume and service expectations. Finally, they worked with the lead SNFs to explain the surgical procedure and set expectations for patient recovery at the facilities. These changes are summarized in the Figure.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe patients and metrics in the baseline and performance periods. The difference in the proportion of patients discharged to a SNF in the baseline and performance periods was examined by a Z-test of proportion and change in relative risk. A Z-test of proportion was also used examine differences in the 90-day all-cause readmission rate and in the average length of stay between the 2 periods.

Results

Differences between Medicare fee-for-service patients in the baseline and performance periods are reported in Table 1. While age, sex, diagnoses, and surgical types were similar, AM-PAC scores and the proportion of patients married or living with someone were higher in the performance period. The AM-PAC score in Table 1 represents the last documented score prior to discharge.

The proportion of Medicare patients discharged to a SNF fell from 39.5% (70/177) in the baseline period to 17.7% (34/192) in the performance period (Table 2). The 21.9% difference was significant at the 0.05 level (Z = 4.6586, P = 0.0001). Medicare patients in the intervention period had nearly half (0.45) the risk (95% confidence interval, 0.314-0.639) of SNF utilization compared with patients in the baseline period. Using Fisher’s exact test and a 2-tailed test, this reduction was found to be significant (P < 0.0001).

Concomitantly, the 90-day all-cause readmission rate among Medicare patients rose from 2.8% (5/177) to 4.7% (9/192), but the difference in proportions was not statistically significant (Z = –0.9356, P = 0.3495). Similarly, the average length of stay for Medicare patients was 2.9 days in both the baseline and performance periods.

Discussion

The intervention was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the SNF discharge rate following total joint replacement. The readmission rate and average length of stay were statistically unchanged. The lack of a statistically significant change in readmissions is important, as previous research has found that total joint replacement patients discharged to a SNF have higher odds of hospital readmission within 90 days than those discharged home.12 Moreover, the readmission rate in the performance period (4.7%) was still substantially lower than the national estimate of 90-day readmission rates associated with total hip arthroplasty (7.7%) and total knee arthroplasty (9.7%).13 For patients, these quality improvements are associated with improved outcomes and lower costs of care.

These outcomes were achieved after a substantial effort at the facility level to onboard new staff; orient them and their colleagues in each step along the care pathway, from scheduling through post-acute care; and build trust among all team members. The critical difference was changing expectations for post-acute recovery and rehabilitation throughout both the new clinical coordination workflow and processes and the existing processes. Orientation of the clinical coordination role was necessary to establish relationships with inpatient team members who were not as intimately involved with the position and expectations. To accomplish this, competing priorities had to be addressed and resolved through standardization efforts developed and implemented by the multidisciplinary team. The team first reviewed reports of such efforts in the initial review of the BPCI literature.1-5 Subsequent analyses of the most germane study3 and related research14 confirmed that a team-based approach to standardization could be successful. The former study used physician and affiliated care teams to build a care pathway that minimized variation in practices across the episode of care, and the latter used a multidisciplinary team approach to develop rapid recovery protocols. Subsequent research has validated the findings that hospital-based multidisciplinary teams have long been associated with improved patient safety, shorter length of stay, and fewer complications.15

Limitations

This quality improvement project was limited to a single facility. As such, adapting the improvements made to Grant Medical Center’s care pathway for implementation throughout the OhioHealth system will take time due to variation of care provided at each campus; scale-up efforts are ongoing. In the Grant facility, the project uncovered instances of unstandardized provider communication pathways, clinical staff workflows, and expectations for patients. Standardization in all 3 instances improved the patient experience. Additionally, data collection requirements for rigorous research and evaluation efforts that had to be done by hand during the project are now being integrated into the EHR.

The improvements described here, which were implemented in anticipation of adopting the CMS BPCI bundled payment model for joint replacement of the lower extremity, were provided to every patient regardless of payer. Patient outcomes varied across payer, as did preoperative education rates and other variables (Table 1). These differences are being tracked and analyzed following the Center’s entry into the CMS BPCI model on October 1, 2018.

Corresponding author: Gregg M. Gascon, PhD, CHDA, OhioHealth Group, 155 E. Broad Street, Suite 1700, Columbus, Ohio 43215; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

From Grant Medical Center (Dr. Wasielewski, Dr. Polonia, Ms. Barca, Ms. Cebriak, Ms. Lucki), and OhioHealth Group (Mr. Rogers, Ms. St. John, Dr. Gascon), Columbus, OH.

Abstract

- Background: Organizations participating in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative enter into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care. There is growing evidence that the use of these payment incentives reduces spending for episodes of care while maintaining or improving quality. A recent study of BPCI and quality outcomes in joint replacement episodes found that nearly all the reduction in spending within BPCI hospitals was generated from the reduced use of institutional post-acute care (eg, skilled nursing facilities [SNF], long-term care facilities, and inpatient rehabilitation facilities).

- Objective: To describe a pilot program designed to reduce the utilization of institutional post-acute care for total joint replacement surgical patients.

- Methods: A multidisciplinary intervention team optimized scheduling, preadmission testing, patient communication, and patient education along a total joint replacement care pathway.

- Results: Among Medicare patients, total discharges to a SNF fell from 39.5% (70/177) in the baseline period to 17.7% (34/192) in the performance period. The risk of SNF utilization among patients in the intervention period was nearly half (0.45; 95% confidence interval, 0.314-0.639) that of patients in the baseline period. Using Fisher’s exact test and a 2-tailed test, this reduction was found to be significant (P < 0.0001). The readmission rate was substantially lower than national norms.

- Conclusion: Optimizing patient care throughout the care pathway using the concerted efforts of a multidisciplinary team is possible given a common vision, shared goals, and clearly communicated expectations.

Keywords: arthroplasty; readmissions; Medicare; post-acute care; Bundled Payment for Care Improvement.

Quality improvement in health care is partially dependent upon processes that standardize episodes of care. This is especially true in the post–acute care setting, where efforts to increase patient engagement and care coordination can improve a patient’s recovery process. One framework for optimizing patient care across an episode of care is the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Bundled Payment for Care Improvement (BPCI) initiative, which links payments for the multiple services patients receive during an episode of care. Organizations participating in the BPCI initiative enter into payment arrangements that include financial and performance accountability for episodes of care. The BPCI initiative provides a framework for episodes of care across multiple types of facilities and clinicians over periods of time (30-day, 60-day, and 90-day episodes).1-5 Evidence that the use of these payment incentives reduces spending for episodes of care while maintaining or improving quality is accumulating. A recent study of BPCI and quality outcomes in joint replacement episodes found that nearly all the reduction in spending within BPCI hospitals was generated from the reduced use of institutional post-acute care, such as skilled nursing facilities (SNF), long-term care facilities, and inpatient rehabilitation facilities.1

Our hospital, the Grant Medical Center, which is part of the OhioHealth system, had agreed to participate in the CMS BPCI–Advanced Model for major joint replacement of the lower extremity, with a start date of October 1, 2018. Prior to adopting this bundled payment and service delivery model for major joint replacement through the BPCI program, we implemented strategic interventions to improve the efficiency of care delivery and reduce post-acute utilization. Although the BPCI program applied only to Medicare patients, the interventions that were developed, implemented, and evaluated in this quality improvement project, which we describe in this article, were provided to all patients who underwent lower-extremity joint replacement, regardless of payer.

Gap Analysis

Prior to developing and implementing the intervention, a gap analysis was performed to determine differences between Grant Medical Center’s care pathway/processes and evidence-based best practice. A steering committee comprised of physician champions, rehabilitation services, senior leadership from the Bone and Joint Center, and care management was gathered. The gap analysis examined the care paths in the preoperative phase, index admission phase, and the post-acute phase of care. Findings of the gap analysis included an underutilized joint education class, overutilization of SNF placement, and lack of key resources to assess the needs of patients prior to surgery.

The Grant Bone and Joint Center offered a comprehensive joint education class in person, but also gave patients the option of utilizing an online learning source. While both were successful, staff believed the in-person class had a greater impact than the online version. Patients who attended the class completed a preoperative assessment by hand, which included a social assessment for identifying potential challenges prior to admission. However, because class attendance was low (< 10%), this assessment tool was not utilized until the patient’s admission in most cases. The gap analysis also identified that the educational content of the class lacked key points to encourage a home-going plan.

The baseline SNF utilization rate (using data from July 1, 2015–June 30, 2016) within the Medicare population was 39.5% (70/177), with an overall (all payers) rate of 22.9% (192/838). This SNF utilization rate was higher than the national benchmark, underscoring the need to focus on a preoperative “plan for home” message. In addition, review of Medicare fee-for-service data from 2014 to 2016 revealed that Grant Medical Center utilized 83 different SNFs over the course of approximately 2 years. In this context, staff saw an opportunity to develop stronger relationships with fewer SNF partners, as well as OhioHealth Home Care, in order to improve care by standardizing functional recovery in post-acute care management.

In sum, the gap analysis found that a lack of standardization, follow through, and engagement in daily multidisciplinary rounds often led to a plan for SNF discharge instead of home. As such, it was determined that the pilot program would target the preoperative and post-acute phases of care and that its primary endpoint would be the reduction of the SNF discharge rate among Medicare fee-for-service patients.

Literature Review

Targeting the SNF discharge rate as the endpoint was also supported by a recent study that showed that most of the reduction in spending for total joint replacement within BPCI hospitals was linked to reduced use of institutional post-acute care.1 Other studies in the joint replacement literature have delineated the specific aspects of care redesign that allow hospitals to provide more efficient and effective care delivery during an episode of care.6-8 A review of these and similar studies of joint replacement quality improvement interventions yielded a number of actionable findings:

- Engaging and educating patients and families is critical. Families and other caregivers must be identified preoperatively, actively engaged, and committed to helping the patient recover.

- Providers must build the expectation in patients that they will return home as soon as it is safe to do so. This includes working to restore physiologic function, managing pain with oral medication, and restoring the physical capability of adapting to a home environment.

- Relationships must be established with post-acute care providers who are able to demonstrate best practices and be willing partners on performance outcomes.

- Providers need to invest in personnel to coordinate care transitions initiated preoperatively that continue through the post-acute phase of care.

- Providers must promote processes that allow patients to more fully own their recovery through coaching and improved communication.

A total joint replacement initiative undertaken at another hospital within the OhioHealth system, Riverside Methodist Hospital, that incorporated these aspects of care redesign demonstrated a significant reduction in SNF utilization. That success informed the development of the initiative at Grant Medical Center.

Methods

Setting

This pilot project was conducted from July 2017 through July 2018 at the Grant Bone and Joint Center in the Grant Medical Center, an urban hospital in Columbus, Ohio. The Bone and Joint Center performs more than 7400 surgeries each year, of which 12% are total joint replacements. Grant Medical Center is a Level I Trauma Center that has received a fourth designation in Magnet Nursing status and has attained The Joint Commission Disease-Specific Care Certification for its total knee and hip arthroplasty, total shoulder, and hip fracture programs.

Intervention

The findings from the gap analysis were incorporated into a standardized preoperative care pathway at the Center. Standardization of the care pathway required developing relationships between office staff, schedulers, inpatient work teams, and preadmission testing, as well as physician group realignment with the larger organization.

During this time, the steering committee identified the need for a designated full-time pre-habilitation case manager to support patients undergoing hip and knee replacements at the Center. With the addition of a new role, prehab case manager, attention was directed to patient social assessment and communication. After the surgery was scheduled but prior to the preoperative education class, each patient received a screening phone call from the prehab case manager that included an initial social assessment. The electronic health record (EHR) was utilized to communicate the results of the assessment, including barriers to a home-going plan. The phone call allowed the case manager to reinforce the importance of class attendance for the patient and primary caregiver, and also allowed any specific concerns identified to be addressed and resolved prior to surgery.

A work group consisting of the prehab case manager, office staff, and the bone and joint leadership team focused on improving the core preoperative education content, same-day preadmission clearance, and class attendance. To support these efforts, the work group (1) created a scheduling document to align preadmission testing and the preoperative education class so they occurred on the same day, (2) improved prior authorization of the surgery to support the post-surgical care team, (3) clarified expectations and roles among office staff and care management staff to optimize the discharge process, and (4) engaged the physician team to encourage a culture change towards setting patient expectations to be discharged to home or a preferred SNF location. Regarding prior authorization communications, prior to the intervention, communication was insufficient, paper driven, and lacking in continuity. Utilizing the EHR, an EPIC platform, a designated documentation location was created, which increased communication among the office schedulers, preadmission testing, and surgery schedulers. The consistent location for recording prior authorization avoided canceled surgeries and claim denials due to missing pieces of information. In addition to these process changes, the surgical offices were geographically realigned to a new single location, a change that brought the staff together and in turn allowed for role clarification and team building and also allowed the staff to identify opportunities for improvement.

The core content of the education class was redesigned to support patients’ understanding of the procedure and what to expect during the hospital stay and discharge for home. Staff worked first to align all preadmission patient requirements with the content of the class. In pilot studies, patients were asked to provide feedback, and this feedback was incorporated into subsequent revisions. Staff developed multilingual handouts, including a surgery instruction sheet with a preoperative social assessment, in addition to creating opportunities for 1:1 education when it was medically or socially appropriate.

The work group brought the physicians in the care pathway together for a focused conversation and education regarding the need for including class attendance as part of their practice. They worked with the physicians’ support team to coordinate standardized follow-up care in the post-acute setting and encouraged the physicians to create a “home-going” culture and reset expectations for length of stay. Prior to the start of this project, the rehabilitation department began using the 6-Clicks Inpatient Basic Mobility Short Form, a standardized instrument comprised of short forms created from the Activity Measure for Post-Acute Care (AM-PAC) instrument. The AMPAC score is used to help establish the patient’s functional level; patients scoring 18 or higher have a higher probability of a successful return home (rather than an institutional discharge). Physical therapists at the Center adminster the 6-Clicks tool for each therapy patient daily, and document the AM-PAC score in the appropriate flowsheet in the EHR in a manner consistent with best practices.9-11 The group utilized the AMPAC score to determine functional status upon discharge, offering guidance for the correct post-acute discharge plan.

The workgroup also established a relationship with the lead home health care service to develop a standard notification process to set volume and service expectations. Finally, they worked with the lead SNFs to explain the surgical procedure and set expectations for patient recovery at the facilities. These changes are summarized in the Figure.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to describe patients and metrics in the baseline and performance periods. The difference in the proportion of patients discharged to a SNF in the baseline and performance periods was examined by a Z-test of proportion and change in relative risk. A Z-test of proportion was also used examine differences in the 90-day all-cause readmission rate and in the average length of stay between the 2 periods.

Results

Differences between Medicare fee-for-service patients in the baseline and performance periods are reported in Table 1. While age, sex, diagnoses, and surgical types were similar, AM-PAC scores and the proportion of patients married or living with someone were higher in the performance period. The AM-PAC score in Table 1 represents the last documented score prior to discharge.

The proportion of Medicare patients discharged to a SNF fell from 39.5% (70/177) in the baseline period to 17.7% (34/192) in the performance period (Table 2). The 21.9% difference was significant at the 0.05 level (Z = 4.6586, P = 0.0001). Medicare patients in the intervention period had nearly half (0.45) the risk (95% confidence interval, 0.314-0.639) of SNF utilization compared with patients in the baseline period. Using Fisher’s exact test and a 2-tailed test, this reduction was found to be significant (P < 0.0001).

Concomitantly, the 90-day all-cause readmission rate among Medicare patients rose from 2.8% (5/177) to 4.7% (9/192), but the difference in proportions was not statistically significant (Z = –0.9356, P = 0.3495). Similarly, the average length of stay for Medicare patients was 2.9 days in both the baseline and performance periods.

Discussion

The intervention was associated with a statistically significant decrease in the SNF discharge rate following total joint replacement. The readmission rate and average length of stay were statistically unchanged. The lack of a statistically significant change in readmissions is important, as previous research has found that total joint replacement patients discharged to a SNF have higher odds of hospital readmission within 90 days than those discharged home.12 Moreover, the readmission rate in the performance period (4.7%) was still substantially lower than the national estimate of 90-day readmission rates associated with total hip arthroplasty (7.7%) and total knee arthroplasty (9.7%).13 For patients, these quality improvements are associated with improved outcomes and lower costs of care.

These outcomes were achieved after a substantial effort at the facility level to onboard new staff; orient them and their colleagues in each step along the care pathway, from scheduling through post-acute care; and build trust among all team members. The critical difference was changing expectations for post-acute recovery and rehabilitation throughout both the new clinical coordination workflow and processes and the existing processes. Orientation of the clinical coordination role was necessary to establish relationships with inpatient team members who were not as intimately involved with the position and expectations. To accomplish this, competing priorities had to be addressed and resolved through standardization efforts developed and implemented by the multidisciplinary team. The team first reviewed reports of such efforts in the initial review of the BPCI literature.1-5 Subsequent analyses of the most germane study3 and related research14 confirmed that a team-based approach to standardization could be successful. The former study used physician and affiliated care teams to build a care pathway that minimized variation in practices across the episode of care, and the latter used a multidisciplinary team approach to develop rapid recovery protocols. Subsequent research has validated the findings that hospital-based multidisciplinary teams have long been associated with improved patient safety, shorter length of stay, and fewer complications.15

Limitations

This quality improvement project was limited to a single facility. As such, adapting the improvements made to Grant Medical Center’s care pathway for implementation throughout the OhioHealth system will take time due to variation of care provided at each campus; scale-up efforts are ongoing. In the Grant facility, the project uncovered instances of unstandardized provider communication pathways, clinical staff workflows, and expectations for patients. Standardization in all 3 instances improved the patient experience. Additionally, data collection requirements for rigorous research and evaluation efforts that had to be done by hand during the project are now being integrated into the EHR.

The improvements described here, which were implemented in anticipation of adopting the CMS BPCI bundled payment model for joint replacement of the lower extremity, were provided to every patient regardless of payer. Patient outcomes varied across payer, as did preoperative education rates and other variables (Table 1). These differences are being tracked and analyzed following the Center’s entry into the CMS BPCI model on October 1, 2018.

Corresponding author: Gregg M. Gascon, PhD, CHDA, OhioHealth Group, 155 E. Broad Street, Suite 1700, Columbus, Ohio 43215; [email protected].

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316:1267-1278.

2. Urdapilleta O, Weinberg D, Pedersen S, et al. Evaluation of the Medicare Acute Care Episodes (ACE) demonstration: final evaluation report. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. May 31, 2013. http://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/ACE-EvaluationReport-Final-5-2-14.pdf.

3. Froemke C, Wang L, DeHart ML, et al. Standardizing care and improving quality under a bundled payment initiative for total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:1676-1682.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. (2015 Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. New Release. January 26, 2015.

5. Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Wild RC, et al. Medicare’s Bundled Payment Initiatives: most hospitals are focused on a few high-volume conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34;371-380.

6. Mechanic RE. Opportunities and challenges for episode-based payment. N Engl J Med. 2011,365:777-779.

7. Mallinson TR, Bateman J, Tseng HY, et al. A comparison of discharge functional status after rehabilitation in skilled nursing, home health, and medical rehabilitation settings for patients after lower-extremity joint replacement surgery. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011:92:712-720.

8. Froimson M, Deadwiller M, Schill M, Cousineau K. Early results of a total joint bundled payment program: the BPCI initiative. Poster No. 2026. Poster presented at Orthopaedic Research Society Annual Meeting; March 15-18, 2014; New Orleans, LA.

9. Haley SM, Coster WJ, Andres PL, et al. Activity outcome measurement for postacute care. Med Care. 2004;42(1 Suppl):S49-S61.

10. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94;379-391.

11. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1252-1261.

12. Bini SA, Fithian DC, Paxton LW, et al. Does discharge disposition after primary total joint arthroplasty affect readmission rates? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:114-117.

13. Ramkumar PN, Chu CT, Harris JD, et al. Causes and rates of unplanned readmissions after elective primary total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthop. 2015;44:397-405.

14. Klingenstein GG, Schoifet SD, Jain RK, et al. Rapid discharge to home after total knee arthroplasty is safe in eligible Medicare patients. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:3308-3313.

15. Epstein NE. Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: A review. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(Suppl 7):S295-S303.

1. Dummit LA, Kahvecioglu D, Marrufo G, et al. Association between hospital participation in a Medicare bundled payment initiative and payments and quality outcomes for lower extremity joint replacement episodes. JAMA. 2016;316:1267-1278.

2. Urdapilleta O, Weinberg D, Pedersen S, et al. Evaluation of the Medicare Acute Care Episodes (ACE) demonstration: final evaluation report. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. May 31, 2013. http://downloads.cms.gov/files/cmmi/ACE-EvaluationReport-Final-5-2-14.pdf.

3. Froemke C, Wang L, DeHart ML, et al. Standardizing care and improving quality under a bundled payment initiative for total joint arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2015;30:1676-1682.

4. US Department of Health and Human Services. (2015 Better, smarter, healthier: In historic announcement, HHS sets clear goals and timeline for shifting Medicare reimbursements from volume to value. New Release. January 26, 2015.

5. Tsai TC, Joynt KE, Wild RC, et al. Medicare’s Bundled Payment Initiatives: most hospitals are focused on a few high-volume conditions. Health Aff (Millwood). 2015;34;371-380.

6. Mechanic RE. Opportunities and challenges for episode-based payment. N Engl J Med. 2011,365:777-779.

7. Mallinson TR, Bateman J, Tseng HY, et al. A comparison of discharge functional status after rehabilitation in skilled nursing, home health, and medical rehabilitation settings for patients after lower-extremity joint replacement surgery. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011:92:712-720.

8. Froimson M, Deadwiller M, Schill M, Cousineau K. Early results of a total joint bundled payment program: the BPCI initiative. Poster No. 2026. Poster presented at Orthopaedic Research Society Annual Meeting; March 15-18, 2014; New Orleans, LA.

9. Haley SM, Coster WJ, Andres PL, et al. Activity outcome measurement for postacute care. Med Care. 2004;42(1 Suppl):S49-S61.

10. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, et al. Validity of the AM-PAC “6-Clicks” inpatient daily activity and basic mobility short forms. Phys Ther. 2014;94;379-391.

11. Jette DU, Stilphen M, Ranganathan VK, et al. AM-PAC “6-Clicks” functional assessment scores predict acute care hospital discharge destination. Phys Ther. 2014;94:1252-1261.

12. Bini SA, Fithian DC, Paxton LW, et al. Does discharge disposition after primary total joint arthroplasty affect readmission rates? J Arthroplasty. 2010;25:114-117.

13. Ramkumar PN, Chu CT, Harris JD, et al. Causes and rates of unplanned readmissions after elective primary total joint arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Orthop. 2015;44:397-405.

14. Klingenstein GG, Schoifet SD, Jain RK, et al. Rapid discharge to home after total knee arthroplasty is safe in eligible Medicare patients. J Arthroplasty. 2017;32:3308-3313.

15. Epstein NE. Multidisciplinary in-hospital teams improve patient outcomes: A review. Surg Neurol Int. 2014;5(Suppl 7):S295-S303.