User login

The modern term orthopedics stems from the older word orthopedia, which was the title of a book published in 1741 by Nicholas Andry, a professor of medicine at the University of Paris.1 The term orthopedia is a composite of 2 Greek words: orthos, meaning “straight and free from deformity,” and paidios, meaning “child.” Together, orthopedics literally means straight child, suggesting the importance of pediatric injuries and deformities in the development of this field. Interestingly, Andry’s book also depicted a crooked young tree attached to a straight and strong staff, which has become the universal symbol of orthopedic surgery and underscores the focus on correcting deformities in the young (Figure).1

Orthopedic surgery is a rapidly advancing medical field with several recent advances noted within orthopedic subspecialties,2-4 basic science,5 and clinical research.6 It is important to recognize the role of history with regards to innovation and research, especially for young trainees and medical students interested in a particular medical specialty. More specifically, it is important to understand the successes and failures of the past in order to advance research and practice, and ultimately improve patient care and outcomes.

In the recent literature, there is no concise yet comprehensive article focusing on the history of orthopedic surgery. The goal of this review is to provide an overview of the history and development of orthopedic surgery from ancient practices to the modern era.

Ancient Orthopedics

While the evidence is limited, the practice of orthopedics dates back to the primitive man.7 Fossil evidence suggests that the orthopedic pathology of today, such as fractures and traumatic amputations, existed in primitive times.8 The union of fractures in fair alignment has also been observed, which emphasizes the efficacy of nonoperative orthopedics and suggests the early use of splints and rehabilitation practices.8,9 Since procedures such as trepanation and crude amputations occurred during the New Stone Age, it is feasible that sophisticated techniques had also been developed for the treatment of injuries.7-9 However, evidence continues to remain limited.7

Later civilizations also developed creative ways to manage orthopedic injuries. For example, the Shoshone Indians, who were known to exist around 700-2000 BCE, made a splint of fresh rawhide that had been soaked in water.9,10 Similarly, some South Australian tribes made splints of clay, which when dried were as good as plaster of Paris.9 Furthermore, bone-setting or reductions was practiced as a profession in many tribes, underscoring the importance of orthopedic injuries in early civilizations.8,9

Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians seemed to have carried on the practices of splinting. For example, 2 splinted specimens were discovered during the Hearst Egyptian Expedition in 1903.7 More specifically, these specimens included a femur and forearm and dated to approximately 300 BCE.7 Other examples of splints made of bamboo and reed padded with linen have been found on mummies as well.8 Similarly, crutches were also used by this civilization, as depicted on a carving made on an Egyptian tomb in 2830 BCE.8

One of the earliest and most significant documents on medicine was discovered in 1862, known as the Edwin Smith papyrus. This document is thought to have been composed by Imhotep, a prominent Egyptian physician, astrologer, architect, and politician, and it specifically categorizes diseases and treatments. Many scholars recognize this medical document as the oldest surgical textbook.11,12 With regards to orthopedic conditions, this document describes the reduction of a dislocated mandible, signs of spinal or vertebral injuries, description of torticollis, and the treatment of fractures such as clavicle fractures.8 This document also discusses ryt, which refers to the purulent discharge from osteomyelitis.8 The following is an excerpt from this ancient document:9

“Instructions on erring a break in his upper arm…Thou shouldst spread out with his two shoulders in order to stretch apart his upper arm until that break falls into its place. Thou shouldst make for him two splints of linen, and thou shouldst apply for him one of them both on the inside of his arm, and the other of them both on the underside of his arm.”

This account illustrates the methodical and meticulous nature of this textbook, and it highlights some of the essentials of medical practice from diagnosis to medical decision-making to treatment.

There are various other contributions to the field of medicine from the Far East; however, many of these pertain to the fields of plastic surgery and general surgery.9

Greeks and Romans

The Greeks are considered to be the first to systematically employ the scientific approach to medicine.8 In the period between 430 BCE to 330 BCE, the Corpus Hippocrates was compiled, which is a Greek text on medicine. It is named for Hippocrates (460 BCE-370 BCE), the father of medicine, and it contains text that applies specifically to the field of orthopedic surgery. For example, this text discuses shoulder dislocations and describes various reduction maneuvers. Hippocrates had a keen understanding of the principles of traction and countertraction, especially as it pertains to the musculoskeletal system.8 In fact, the Hippocratic method is still used for reducing anterior shoulder dislocations, and its description can be found in several modern orthopedic texts, including recent articles.13 The Corpus Hippocrates also describes the correction of clubfoot deformity, and the treatment of infected open fractures with pitch cerate and wine compresses.8

Hippocrates also described the treatment of fractures, the principles of traction, and the implications of malunions. For example, Hippocrates wrote, “For the arm, when shortened, might be concealed and the mistake will not be great, but a shortened thigh bone will leave a man maimed.”1 In addition, spinal deformities were recognized by the Greeks, and Hippocrates devised an extension bench for the correction of such deformities.1 From their contributions to anatomy and surgical practice, the Greeks have made significant contributions to the field of surgery.9

During the Roman period, another Greek surgeon by the name of Galen described the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. He served as a gladiatorial surgeon in Rome, and today, he is considered to be the father of sports medicine.8 He is also credited with coining the terms scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis to denote the spinal deformities that were first described by Hippocrates.1 In the Roman period, amputations were also performed, and primitive prostheses were developed.9

The Middle Ages

There was relatively little progress in the study of medicine for a thousand years after the fall of the Roman Empire.9 This stagnation was predominantly due to the early Christian Church inhibiting freedom of thought and observation, as well as prohibiting human dissection and the study of anatomy. The first medical school in Europe was established in Salerno, Italy, during the ninth century. This school provided primarily pedantic teaching to its students and perpetuated the theories of the elements and humors. Later on, the University of Bologna became one of the first academic institutions to offer hands-on surgical training.9 One of the most famous surgeons of the Middle Ages was Guy de Chuauliac, who studied at Montpellier and Bologna. He was a leader in the ethical principles of surgery as well as the practice of surgery, and wrote the following with regards to femur fractures:9

“After the application of splints, I attach to the foot a mass of lead as a weight, taking care to pass the cord which supports the weight over a small pulley in such a manner that it shall pull on the leg in a horizontal direction.”

This description is strikingly similar to the modern-day nonoperative management of femur fractures, and underscores the importance of traction, which as mentioned above, was first described by Hippocrates.

Eventually, medicine began to separate from the Church, most likely due to an increase in the complexity of medical theories, the rise of secular universities, and an increase in medical knowledge from Eastern and Middle-Eastern groups.9

The Renaissance and the Foundations of Modern Orthopedics

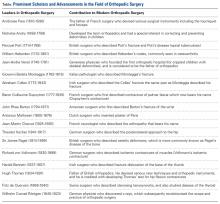

Until the 16th century, the majority of medical theories were heavily influenced by the work of Hippocrates.8 The scientific study of anatomy gained prominence during this time, especially due to the work done by great artists, such as Leonardo Di Vinci.9 The Table

After a period of rapid expansion of the field of orthopedics, and following the Renaissance, many hospitals were built focusing on the sick and disabled, which solidified orthopedics’ position as a major medical specialty.1 For example, in 1863, James Knight founded the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled in New York City. This hospital became the oldest orthopedic hospital in the United States, and it later became known as the Hospital for Special Surgery.14,15 Several additional orthopedic institutions were formed, including the New York Orthopedic Dispensary in 1886 and Hospital for Deformities and Joint Diseases in 1917. Orthopedic surgery residency programs also began to be developed in the late 1800s.14 More specifically, Virgil Gibney at Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled began the first orthopedic training program in the United States in 1888. Young doctors in this program trained for 1 year as junior assistant, senior assistant, and house surgeon, and began to be known as resident doctors.14

The Modern Era

In the 20th century, rapid development continued to better control infections as well as develop and introduce novel technology. For example, the invention of x-ray in 1895 by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen improved our ability to diagnose and manage orthopedic conditions ranging from fractures to avascular necrosis of the femoral head to osteoarthritis.8,14 Spinal surgery also developed rapidly with Russell Hibbs describing a technique for spinal fusion at the New York Orthopedic Hospital.8 Similarly, the World Wars served as a catalyst in the development of the subspecialty of orthopedic trauma, with increasing attention placed on open wounds and proficiency with amputations, internal fixation, and wound care. In 1942, Austin Moore performed the first metal hip arthroplasty, and the field of joint replacement was subsequently advanced by the work of Sir John Charnley in the 1960s.8

Conclusion

Despite its relatively recent specialization, orthopedic surgery has a rich history rooted in ancient practices dating back to the primitive man. Over time, there has been significant development in the field in terms of surgical and nonsurgical treatment of orthopedic pathology and disease. Various cultures have played an instrumental role in developing this field, and it is remarkable to see that several practices have persisted since the time of these ancient civilizations. During the Renaissance, there was a considerable emphasis placed on pediatric deformity, but orthopedic surgeons have now branched out to subspecialty practice ranging from orthopedic trauma to joint replacement to oncology.1 For students of medicine and orthopedics, it is important to learn about the origins of this field and to appreciate its gradual development. Orthopedic surgery is a diverse and fascinating field that will most likely continue to develop with increased subspecialization and improved research at the molecular and population level. With a growing emphasis placed on outcomes and healthcare cost by today’s society, it will be fascinating to see how this field continues to evolve in the future.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E434-E438. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Ponseti IV. History of orthopedic surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 1991;11:59-64.

2. Ninomiya JT, Dean JC, Incavo SJ. What’s new in hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(18):1543-1551.

3. Sabharwal S, Nelson SC, Sontich JK. What’s new in limb lengthening and deformity correction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(16):1375-1384.

4. Ricci WM, Black JC, McAndrew CM, Gardner MJ. What’s new in orthopedic trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(14):1200-1207.

5. Rodeo SA, Sugiguchi F, Fortier LA, Cunningham ME, Maher S. What’s new in orthopedic research. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):2015-2019.

6. Pugley AJ, Martin CT, Harwood J, Ong KL, Bozic KJ, Callaghan JJ. Database and registry research in orthopedic surgery. Part 1: Claims-based data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(15):1278-1287.

7. Colton CL. The history of fracture treatment. In: Browner BD, Jupiter JB, Levine AM, Trafton PG, Krettek C, eds. Skeletal Trauma: Basic Science, Management, and Reconstruction. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:3-32.

8. Brakoulias,V. History of orthopaedics. WorldOrtho Web site. http://pioa.net/documents/Historyoforthopaedics.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2016.

9. Bishop WJ. The Early History of Surgery. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Books; 1995.

10. Watson T. Wyoming site reveals more prehistoric mountain villages. USA Today. October 20, 2013. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/10/20/wyoming-prehistoric-villages/2965263. Accessed October 6, 2016.

11. Minagar A, Ragheb J, Kelley RE. The Edwin Smith surgical papyrus: description and analysis of the earliest case of aphasia. J Med Biogr. 2003;11(2):114-117.

12. Atta HM. Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: the oldest known surgical treatise. Am Surg. 1999;65(12):1190-1192.

13. Sayegh FE, Kenanidis EI, Papavasiliou KA, Potoupnis ME, Kirkos JM, Kapetanos GA. Reduction of acute anterior dislocations: a prospective randomized study comparing a new technique with the Hippocratic and Kocher methods. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(12):2775-2782.

14. Levine DB. Anatomy of a Hospital: Hospital for Special Surgery 1863-2013. New York, NY: Print Mattes; 2013.

15. Wilson PD, Levine DB. Hospital for special surgery. A brief review of its development and current position. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(374):90-106.

The modern term orthopedics stems from the older word orthopedia, which was the title of a book published in 1741 by Nicholas Andry, a professor of medicine at the University of Paris.1 The term orthopedia is a composite of 2 Greek words: orthos, meaning “straight and free from deformity,” and paidios, meaning “child.” Together, orthopedics literally means straight child, suggesting the importance of pediatric injuries and deformities in the development of this field. Interestingly, Andry’s book also depicted a crooked young tree attached to a straight and strong staff, which has become the universal symbol of orthopedic surgery and underscores the focus on correcting deformities in the young (Figure).1

Orthopedic surgery is a rapidly advancing medical field with several recent advances noted within orthopedic subspecialties,2-4 basic science,5 and clinical research.6 It is important to recognize the role of history with regards to innovation and research, especially for young trainees and medical students interested in a particular medical specialty. More specifically, it is important to understand the successes and failures of the past in order to advance research and practice, and ultimately improve patient care and outcomes.

In the recent literature, there is no concise yet comprehensive article focusing on the history of orthopedic surgery. The goal of this review is to provide an overview of the history and development of orthopedic surgery from ancient practices to the modern era.

Ancient Orthopedics

While the evidence is limited, the practice of orthopedics dates back to the primitive man.7 Fossil evidence suggests that the orthopedic pathology of today, such as fractures and traumatic amputations, existed in primitive times.8 The union of fractures in fair alignment has also been observed, which emphasizes the efficacy of nonoperative orthopedics and suggests the early use of splints and rehabilitation practices.8,9 Since procedures such as trepanation and crude amputations occurred during the New Stone Age, it is feasible that sophisticated techniques had also been developed for the treatment of injuries.7-9 However, evidence continues to remain limited.7

Later civilizations also developed creative ways to manage orthopedic injuries. For example, the Shoshone Indians, who were known to exist around 700-2000 BCE, made a splint of fresh rawhide that had been soaked in water.9,10 Similarly, some South Australian tribes made splints of clay, which when dried were as good as plaster of Paris.9 Furthermore, bone-setting or reductions was practiced as a profession in many tribes, underscoring the importance of orthopedic injuries in early civilizations.8,9

Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians seemed to have carried on the practices of splinting. For example, 2 splinted specimens were discovered during the Hearst Egyptian Expedition in 1903.7 More specifically, these specimens included a femur and forearm and dated to approximately 300 BCE.7 Other examples of splints made of bamboo and reed padded with linen have been found on mummies as well.8 Similarly, crutches were also used by this civilization, as depicted on a carving made on an Egyptian tomb in 2830 BCE.8

One of the earliest and most significant documents on medicine was discovered in 1862, known as the Edwin Smith papyrus. This document is thought to have been composed by Imhotep, a prominent Egyptian physician, astrologer, architect, and politician, and it specifically categorizes diseases and treatments. Many scholars recognize this medical document as the oldest surgical textbook.11,12 With regards to orthopedic conditions, this document describes the reduction of a dislocated mandible, signs of spinal or vertebral injuries, description of torticollis, and the treatment of fractures such as clavicle fractures.8 This document also discusses ryt, which refers to the purulent discharge from osteomyelitis.8 The following is an excerpt from this ancient document:9

“Instructions on erring a break in his upper arm…Thou shouldst spread out with his two shoulders in order to stretch apart his upper arm until that break falls into its place. Thou shouldst make for him two splints of linen, and thou shouldst apply for him one of them both on the inside of his arm, and the other of them both on the underside of his arm.”

This account illustrates the methodical and meticulous nature of this textbook, and it highlights some of the essentials of medical practice from diagnosis to medical decision-making to treatment.

There are various other contributions to the field of medicine from the Far East; however, many of these pertain to the fields of plastic surgery and general surgery.9

Greeks and Romans

The Greeks are considered to be the first to systematically employ the scientific approach to medicine.8 In the period between 430 BCE to 330 BCE, the Corpus Hippocrates was compiled, which is a Greek text on medicine. It is named for Hippocrates (460 BCE-370 BCE), the father of medicine, and it contains text that applies specifically to the field of orthopedic surgery. For example, this text discuses shoulder dislocations and describes various reduction maneuvers. Hippocrates had a keen understanding of the principles of traction and countertraction, especially as it pertains to the musculoskeletal system.8 In fact, the Hippocratic method is still used for reducing anterior shoulder dislocations, and its description can be found in several modern orthopedic texts, including recent articles.13 The Corpus Hippocrates also describes the correction of clubfoot deformity, and the treatment of infected open fractures with pitch cerate and wine compresses.8

Hippocrates also described the treatment of fractures, the principles of traction, and the implications of malunions. For example, Hippocrates wrote, “For the arm, when shortened, might be concealed and the mistake will not be great, but a shortened thigh bone will leave a man maimed.”1 In addition, spinal deformities were recognized by the Greeks, and Hippocrates devised an extension bench for the correction of such deformities.1 From their contributions to anatomy and surgical practice, the Greeks have made significant contributions to the field of surgery.9

During the Roman period, another Greek surgeon by the name of Galen described the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. He served as a gladiatorial surgeon in Rome, and today, he is considered to be the father of sports medicine.8 He is also credited with coining the terms scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis to denote the spinal deformities that were first described by Hippocrates.1 In the Roman period, amputations were also performed, and primitive prostheses were developed.9

The Middle Ages

There was relatively little progress in the study of medicine for a thousand years after the fall of the Roman Empire.9 This stagnation was predominantly due to the early Christian Church inhibiting freedom of thought and observation, as well as prohibiting human dissection and the study of anatomy. The first medical school in Europe was established in Salerno, Italy, during the ninth century. This school provided primarily pedantic teaching to its students and perpetuated the theories of the elements and humors. Later on, the University of Bologna became one of the first academic institutions to offer hands-on surgical training.9 One of the most famous surgeons of the Middle Ages was Guy de Chuauliac, who studied at Montpellier and Bologna. He was a leader in the ethical principles of surgery as well as the practice of surgery, and wrote the following with regards to femur fractures:9

“After the application of splints, I attach to the foot a mass of lead as a weight, taking care to pass the cord which supports the weight over a small pulley in such a manner that it shall pull on the leg in a horizontal direction.”

This description is strikingly similar to the modern-day nonoperative management of femur fractures, and underscores the importance of traction, which as mentioned above, was first described by Hippocrates.

Eventually, medicine began to separate from the Church, most likely due to an increase in the complexity of medical theories, the rise of secular universities, and an increase in medical knowledge from Eastern and Middle-Eastern groups.9

The Renaissance and the Foundations of Modern Orthopedics

Until the 16th century, the majority of medical theories were heavily influenced by the work of Hippocrates.8 The scientific study of anatomy gained prominence during this time, especially due to the work done by great artists, such as Leonardo Di Vinci.9 The Table

After a period of rapid expansion of the field of orthopedics, and following the Renaissance, many hospitals were built focusing on the sick and disabled, which solidified orthopedics’ position as a major medical specialty.1 For example, in 1863, James Knight founded the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled in New York City. This hospital became the oldest orthopedic hospital in the United States, and it later became known as the Hospital for Special Surgery.14,15 Several additional orthopedic institutions were formed, including the New York Orthopedic Dispensary in 1886 and Hospital for Deformities and Joint Diseases in 1917. Orthopedic surgery residency programs also began to be developed in the late 1800s.14 More specifically, Virgil Gibney at Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled began the first orthopedic training program in the United States in 1888. Young doctors in this program trained for 1 year as junior assistant, senior assistant, and house surgeon, and began to be known as resident doctors.14

The Modern Era

In the 20th century, rapid development continued to better control infections as well as develop and introduce novel technology. For example, the invention of x-ray in 1895 by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen improved our ability to diagnose and manage orthopedic conditions ranging from fractures to avascular necrosis of the femoral head to osteoarthritis.8,14 Spinal surgery also developed rapidly with Russell Hibbs describing a technique for spinal fusion at the New York Orthopedic Hospital.8 Similarly, the World Wars served as a catalyst in the development of the subspecialty of orthopedic trauma, with increasing attention placed on open wounds and proficiency with amputations, internal fixation, and wound care. In 1942, Austin Moore performed the first metal hip arthroplasty, and the field of joint replacement was subsequently advanced by the work of Sir John Charnley in the 1960s.8

Conclusion

Despite its relatively recent specialization, orthopedic surgery has a rich history rooted in ancient practices dating back to the primitive man. Over time, there has been significant development in the field in terms of surgical and nonsurgical treatment of orthopedic pathology and disease. Various cultures have played an instrumental role in developing this field, and it is remarkable to see that several practices have persisted since the time of these ancient civilizations. During the Renaissance, there was a considerable emphasis placed on pediatric deformity, but orthopedic surgeons have now branched out to subspecialty practice ranging from orthopedic trauma to joint replacement to oncology.1 For students of medicine and orthopedics, it is important to learn about the origins of this field and to appreciate its gradual development. Orthopedic surgery is a diverse and fascinating field that will most likely continue to develop with increased subspecialization and improved research at the molecular and population level. With a growing emphasis placed on outcomes and healthcare cost by today’s society, it will be fascinating to see how this field continues to evolve in the future.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E434-E438. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

The modern term orthopedics stems from the older word orthopedia, which was the title of a book published in 1741 by Nicholas Andry, a professor of medicine at the University of Paris.1 The term orthopedia is a composite of 2 Greek words: orthos, meaning “straight and free from deformity,” and paidios, meaning “child.” Together, orthopedics literally means straight child, suggesting the importance of pediatric injuries and deformities in the development of this field. Interestingly, Andry’s book also depicted a crooked young tree attached to a straight and strong staff, which has become the universal symbol of orthopedic surgery and underscores the focus on correcting deformities in the young (Figure).1

Orthopedic surgery is a rapidly advancing medical field with several recent advances noted within orthopedic subspecialties,2-4 basic science,5 and clinical research.6 It is important to recognize the role of history with regards to innovation and research, especially for young trainees and medical students interested in a particular medical specialty. More specifically, it is important to understand the successes and failures of the past in order to advance research and practice, and ultimately improve patient care and outcomes.

In the recent literature, there is no concise yet comprehensive article focusing on the history of orthopedic surgery. The goal of this review is to provide an overview of the history and development of orthopedic surgery from ancient practices to the modern era.

Ancient Orthopedics

While the evidence is limited, the practice of orthopedics dates back to the primitive man.7 Fossil evidence suggests that the orthopedic pathology of today, such as fractures and traumatic amputations, existed in primitive times.8 The union of fractures in fair alignment has also been observed, which emphasizes the efficacy of nonoperative orthopedics and suggests the early use of splints and rehabilitation practices.8,9 Since procedures such as trepanation and crude amputations occurred during the New Stone Age, it is feasible that sophisticated techniques had also been developed for the treatment of injuries.7-9 However, evidence continues to remain limited.7

Later civilizations also developed creative ways to manage orthopedic injuries. For example, the Shoshone Indians, who were known to exist around 700-2000 BCE, made a splint of fresh rawhide that had been soaked in water.9,10 Similarly, some South Australian tribes made splints of clay, which when dried were as good as plaster of Paris.9 Furthermore, bone-setting or reductions was practiced as a profession in many tribes, underscoring the importance of orthopedic injuries in early civilizations.8,9

Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians seemed to have carried on the practices of splinting. For example, 2 splinted specimens were discovered during the Hearst Egyptian Expedition in 1903.7 More specifically, these specimens included a femur and forearm and dated to approximately 300 BCE.7 Other examples of splints made of bamboo and reed padded with linen have been found on mummies as well.8 Similarly, crutches were also used by this civilization, as depicted on a carving made on an Egyptian tomb in 2830 BCE.8

One of the earliest and most significant documents on medicine was discovered in 1862, known as the Edwin Smith papyrus. This document is thought to have been composed by Imhotep, a prominent Egyptian physician, astrologer, architect, and politician, and it specifically categorizes diseases and treatments. Many scholars recognize this medical document as the oldest surgical textbook.11,12 With regards to orthopedic conditions, this document describes the reduction of a dislocated mandible, signs of spinal or vertebral injuries, description of torticollis, and the treatment of fractures such as clavicle fractures.8 This document also discusses ryt, which refers to the purulent discharge from osteomyelitis.8 The following is an excerpt from this ancient document:9

“Instructions on erring a break in his upper arm…Thou shouldst spread out with his two shoulders in order to stretch apart his upper arm until that break falls into its place. Thou shouldst make for him two splints of linen, and thou shouldst apply for him one of them both on the inside of his arm, and the other of them both on the underside of his arm.”

This account illustrates the methodical and meticulous nature of this textbook, and it highlights some of the essentials of medical practice from diagnosis to medical decision-making to treatment.

There are various other contributions to the field of medicine from the Far East; however, many of these pertain to the fields of plastic surgery and general surgery.9

Greeks and Romans

The Greeks are considered to be the first to systematically employ the scientific approach to medicine.8 In the period between 430 BCE to 330 BCE, the Corpus Hippocrates was compiled, which is a Greek text on medicine. It is named for Hippocrates (460 BCE-370 BCE), the father of medicine, and it contains text that applies specifically to the field of orthopedic surgery. For example, this text discuses shoulder dislocations and describes various reduction maneuvers. Hippocrates had a keen understanding of the principles of traction and countertraction, especially as it pertains to the musculoskeletal system.8 In fact, the Hippocratic method is still used for reducing anterior shoulder dislocations, and its description can be found in several modern orthopedic texts, including recent articles.13 The Corpus Hippocrates also describes the correction of clubfoot deformity, and the treatment of infected open fractures with pitch cerate and wine compresses.8

Hippocrates also described the treatment of fractures, the principles of traction, and the implications of malunions. For example, Hippocrates wrote, “For the arm, when shortened, might be concealed and the mistake will not be great, but a shortened thigh bone will leave a man maimed.”1 In addition, spinal deformities were recognized by the Greeks, and Hippocrates devised an extension bench for the correction of such deformities.1 From their contributions to anatomy and surgical practice, the Greeks have made significant contributions to the field of surgery.9

During the Roman period, another Greek surgeon by the name of Galen described the musculoskeletal and nervous systems. He served as a gladiatorial surgeon in Rome, and today, he is considered to be the father of sports medicine.8 He is also credited with coining the terms scoliosis, kyphosis, and lordosis to denote the spinal deformities that were first described by Hippocrates.1 In the Roman period, amputations were also performed, and primitive prostheses were developed.9

The Middle Ages

There was relatively little progress in the study of medicine for a thousand years after the fall of the Roman Empire.9 This stagnation was predominantly due to the early Christian Church inhibiting freedom of thought and observation, as well as prohibiting human dissection and the study of anatomy. The first medical school in Europe was established in Salerno, Italy, during the ninth century. This school provided primarily pedantic teaching to its students and perpetuated the theories of the elements and humors. Later on, the University of Bologna became one of the first academic institutions to offer hands-on surgical training.9 One of the most famous surgeons of the Middle Ages was Guy de Chuauliac, who studied at Montpellier and Bologna. He was a leader in the ethical principles of surgery as well as the practice of surgery, and wrote the following with regards to femur fractures:9

“After the application of splints, I attach to the foot a mass of lead as a weight, taking care to pass the cord which supports the weight over a small pulley in such a manner that it shall pull on the leg in a horizontal direction.”

This description is strikingly similar to the modern-day nonoperative management of femur fractures, and underscores the importance of traction, which as mentioned above, was first described by Hippocrates.

Eventually, medicine began to separate from the Church, most likely due to an increase in the complexity of medical theories, the rise of secular universities, and an increase in medical knowledge from Eastern and Middle-Eastern groups.9

The Renaissance and the Foundations of Modern Orthopedics

Until the 16th century, the majority of medical theories were heavily influenced by the work of Hippocrates.8 The scientific study of anatomy gained prominence during this time, especially due to the work done by great artists, such as Leonardo Di Vinci.9 The Table

After a period of rapid expansion of the field of orthopedics, and following the Renaissance, many hospitals were built focusing on the sick and disabled, which solidified orthopedics’ position as a major medical specialty.1 For example, in 1863, James Knight founded the Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled in New York City. This hospital became the oldest orthopedic hospital in the United States, and it later became known as the Hospital for Special Surgery.14,15 Several additional orthopedic institutions were formed, including the New York Orthopedic Dispensary in 1886 and Hospital for Deformities and Joint Diseases in 1917. Orthopedic surgery residency programs also began to be developed in the late 1800s.14 More specifically, Virgil Gibney at Hospital for the Ruptured and Crippled began the first orthopedic training program in the United States in 1888. Young doctors in this program trained for 1 year as junior assistant, senior assistant, and house surgeon, and began to be known as resident doctors.14

The Modern Era

In the 20th century, rapid development continued to better control infections as well as develop and introduce novel technology. For example, the invention of x-ray in 1895 by Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen improved our ability to diagnose and manage orthopedic conditions ranging from fractures to avascular necrosis of the femoral head to osteoarthritis.8,14 Spinal surgery also developed rapidly with Russell Hibbs describing a technique for spinal fusion at the New York Orthopedic Hospital.8 Similarly, the World Wars served as a catalyst in the development of the subspecialty of orthopedic trauma, with increasing attention placed on open wounds and proficiency with amputations, internal fixation, and wound care. In 1942, Austin Moore performed the first metal hip arthroplasty, and the field of joint replacement was subsequently advanced by the work of Sir John Charnley in the 1960s.8

Conclusion

Despite its relatively recent specialization, orthopedic surgery has a rich history rooted in ancient practices dating back to the primitive man. Over time, there has been significant development in the field in terms of surgical and nonsurgical treatment of orthopedic pathology and disease. Various cultures have played an instrumental role in developing this field, and it is remarkable to see that several practices have persisted since the time of these ancient civilizations. During the Renaissance, there was a considerable emphasis placed on pediatric deformity, but orthopedic surgeons have now branched out to subspecialty practice ranging from orthopedic trauma to joint replacement to oncology.1 For students of medicine and orthopedics, it is important to learn about the origins of this field and to appreciate its gradual development. Orthopedic surgery is a diverse and fascinating field that will most likely continue to develop with increased subspecialization and improved research at the molecular and population level. With a growing emphasis placed on outcomes and healthcare cost by today’s society, it will be fascinating to see how this field continues to evolve in the future.

Am J Orthop. 2016;45(7):E434-E438. Copyright Frontline Medical Communications Inc. 2016. All rights reserved.

1. Ponseti IV. History of orthopedic surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 1991;11:59-64.

2. Ninomiya JT, Dean JC, Incavo SJ. What’s new in hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(18):1543-1551.

3. Sabharwal S, Nelson SC, Sontich JK. What’s new in limb lengthening and deformity correction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(16):1375-1384.

4. Ricci WM, Black JC, McAndrew CM, Gardner MJ. What’s new in orthopedic trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(14):1200-1207.

5. Rodeo SA, Sugiguchi F, Fortier LA, Cunningham ME, Maher S. What’s new in orthopedic research. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):2015-2019.

6. Pugley AJ, Martin CT, Harwood J, Ong KL, Bozic KJ, Callaghan JJ. Database and registry research in orthopedic surgery. Part 1: Claims-based data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(15):1278-1287.

7. Colton CL. The history of fracture treatment. In: Browner BD, Jupiter JB, Levine AM, Trafton PG, Krettek C, eds. Skeletal Trauma: Basic Science, Management, and Reconstruction. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:3-32.

8. Brakoulias,V. History of orthopaedics. WorldOrtho Web site. http://pioa.net/documents/Historyoforthopaedics.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2016.

9. Bishop WJ. The Early History of Surgery. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Books; 1995.

10. Watson T. Wyoming site reveals more prehistoric mountain villages. USA Today. October 20, 2013. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/10/20/wyoming-prehistoric-villages/2965263. Accessed October 6, 2016.

11. Minagar A, Ragheb J, Kelley RE. The Edwin Smith surgical papyrus: description and analysis of the earliest case of aphasia. J Med Biogr. 2003;11(2):114-117.

12. Atta HM. Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: the oldest known surgical treatise. Am Surg. 1999;65(12):1190-1192.

13. Sayegh FE, Kenanidis EI, Papavasiliou KA, Potoupnis ME, Kirkos JM, Kapetanos GA. Reduction of acute anterior dislocations: a prospective randomized study comparing a new technique with the Hippocratic and Kocher methods. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(12):2775-2782.

14. Levine DB. Anatomy of a Hospital: Hospital for Special Surgery 1863-2013. New York, NY: Print Mattes; 2013.

15. Wilson PD, Levine DB. Hospital for special surgery. A brief review of its development and current position. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(374):90-106.

1. Ponseti IV. History of orthopedic surgery. Iowa Orthop J. 1991;11:59-64.

2. Ninomiya JT, Dean JC, Incavo SJ. What’s new in hip replacement. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(18):1543-1551.

3. Sabharwal S, Nelson SC, Sontich JK. What’s new in limb lengthening and deformity correction. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(16):1375-1384.

4. Ricci WM, Black JC, McAndrew CM, Gardner MJ. What’s new in orthopedic trauma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(14):1200-1207.

5. Rodeo SA, Sugiguchi F, Fortier LA, Cunningham ME, Maher S. What’s new in orthopedic research. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2014;96(23):2015-2019.

6. Pugley AJ, Martin CT, Harwood J, Ong KL, Bozic KJ, Callaghan JJ. Database and registry research in orthopedic surgery. Part 1: Claims-based data. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2015;97(15):1278-1287.

7. Colton CL. The history of fracture treatment. In: Browner BD, Jupiter JB, Levine AM, Trafton PG, Krettek C, eds. Skeletal Trauma: Basic Science, Management, and Reconstruction. 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:3-32.

8. Brakoulias,V. History of orthopaedics. WorldOrtho Web site. http://pioa.net/documents/Historyoforthopaedics.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2016.

9. Bishop WJ. The Early History of Surgery. New York, NY: Barnes & Noble Books; 1995.

10. Watson T. Wyoming site reveals more prehistoric mountain villages. USA Today. October 20, 2013. http://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2013/10/20/wyoming-prehistoric-villages/2965263. Accessed October 6, 2016.

11. Minagar A, Ragheb J, Kelley RE. The Edwin Smith surgical papyrus: description and analysis of the earliest case of aphasia. J Med Biogr. 2003;11(2):114-117.

12. Atta HM. Edwin Smith Surgical Papyrus: the oldest known surgical treatise. Am Surg. 1999;65(12):1190-1192.

13. Sayegh FE, Kenanidis EI, Papavasiliou KA, Potoupnis ME, Kirkos JM, Kapetanos GA. Reduction of acute anterior dislocations: a prospective randomized study comparing a new technique with the Hippocratic and Kocher methods. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2009;91(12):2775-2782.

14. Levine DB. Anatomy of a Hospital: Hospital for Special Surgery 1863-2013. New York, NY: Print Mattes; 2013.

15. Wilson PD, Levine DB. Hospital for special surgery. A brief review of its development and current position. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2000;(374):90-106.