User login

Pathogenic Significance of Serum Syndecan-1 and Syndecan-4 in Psoriasis

Psoriasis, one of the most researched diseases in dermatology, has a complex pathogenesis that is not yet fully understood. One of the most important stages of psoriasis pathogenesis is the proliferation of T helper (Th) 17 cells by IL-23 released from myeloid dendritic cells. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α released from Th1 cells and IL-17 and IL-22 released from Th17 cells are known to induce the proliferation of keratinocytes and the release of chemokines responsible for neutrophil chemotaxis.1

Although secondary messengers such as cytokines and chemokines, which provide cell interaction with the extracellular matrix (ECM), have their own specific receptors, it is known that syndecans (SDCs) play a role in ECM and cell interactions and have receptor or coreceptor functions.2 In humans, 4 types of SDCs have been identified (SDC1-SDC4), which are type I transmembrane proteoglycans found in all nucleated cells. Syndecans consist of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan chains that are structurally linked to a core protein sequence. The molecule has cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and extracellular domains.2,3 While SDCs often are described as coreceptors for integrins and growth factor and hormone receptors, they also are capable of acting as signaling receptors by engaging intracellular messengers, including actin-related proteins and protein kinases.4

Prior research has indicated that the release of heparanase from the lysosomes of leukocytes during infection, inflammation, and endothelial damage causes cleavage of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans from the extracellular domains of SDCs. The peptide chains at the SDC core then are separated by matrix metalloproteinases in a process known as shedding. The shed SDCs may have either a stimulating or a suppressive effect on their receptor activity. Several cytokines are known to cause SDC shedding.5,6 Many studies in recent years have reported that SDCs play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, for which serum levels of soluble SDCs can be biomarkers.7

In this study, we aimed to evaluate and compare serum SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels in patients with psoriasis vs healthy controls. Additionally, by reviewing the literature data, we analyzed whether SDCs can be implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and their potential role in this process.

Methods

The study population consisted of 40 patients with psoriasis and 40 healthy controls. Age and sex characteristics were similar between the 2 groups, but weight distribution was not. The psoriasis group included patients older than 18 years who had received a clinical and/or histologic diagnosis, had no systemic disease other than psoriasis in their medical history, and had not used any systemic treatment or phototherapy for the past 3 months. Healthy patients older than 18 years who had no medical history of inflammatory disease were included in the control group. Participants provided signed consent.

Data such as medical history, laboratory findings, and physical specifications were recorded. A Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 10 or lower was considered mild disease, and a score higher than 10 was considered moderate to severe disease. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels.

The data were evaluated using the IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0 statistical package program. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. The conformity of the data to a normal distribution was examined using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean (SD) and nonnormally distributed variables were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Data were compared between the 2 study groups using either a student t test (normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (nonnormal distribution). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Categorical data were compared using a χ2 test. Associations among SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, IL-17A, and other variables were assessed using Spearman rank correlation. A binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether serum SDC1 and SDC4 levels were independent risk factors for psoriasis.

Results

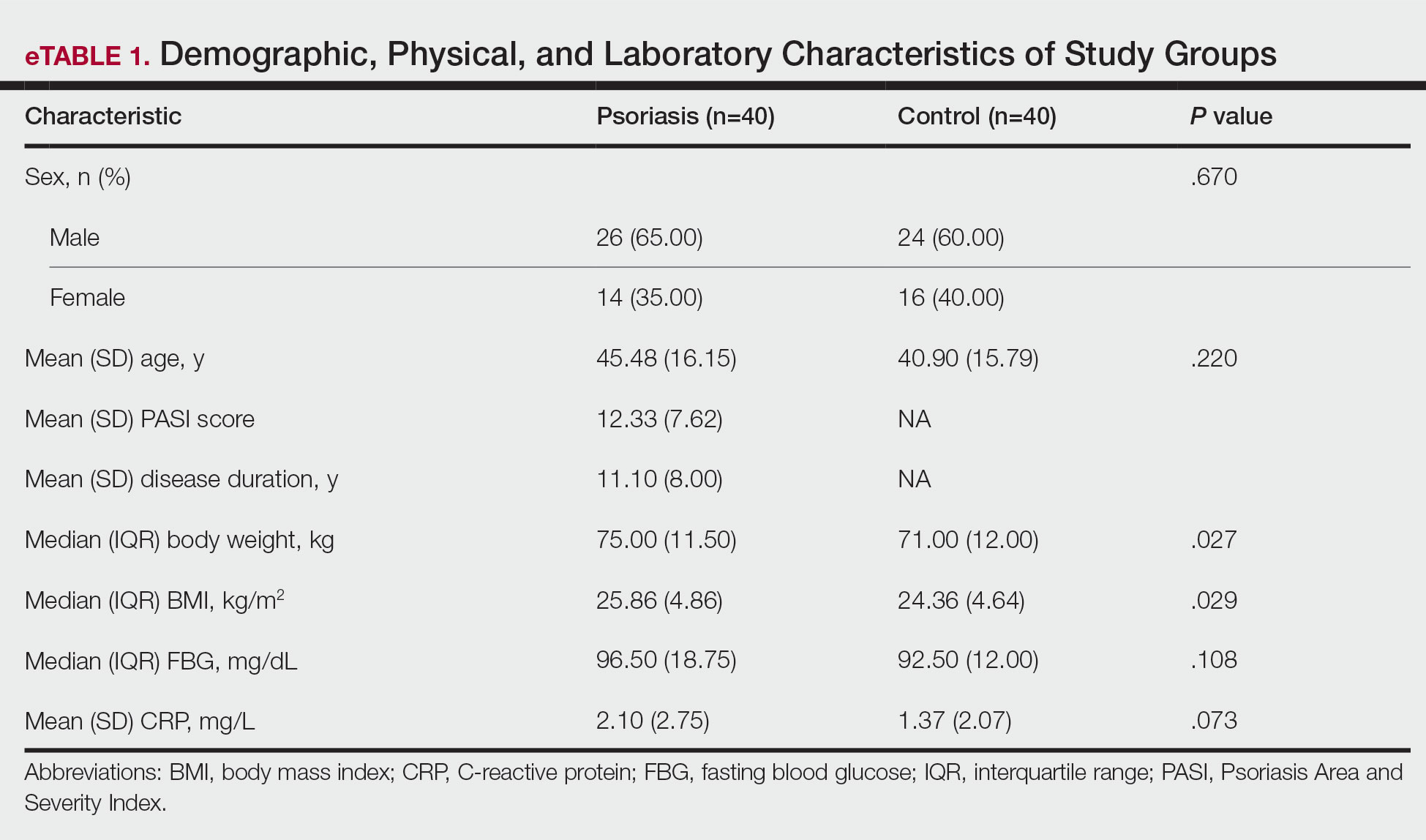

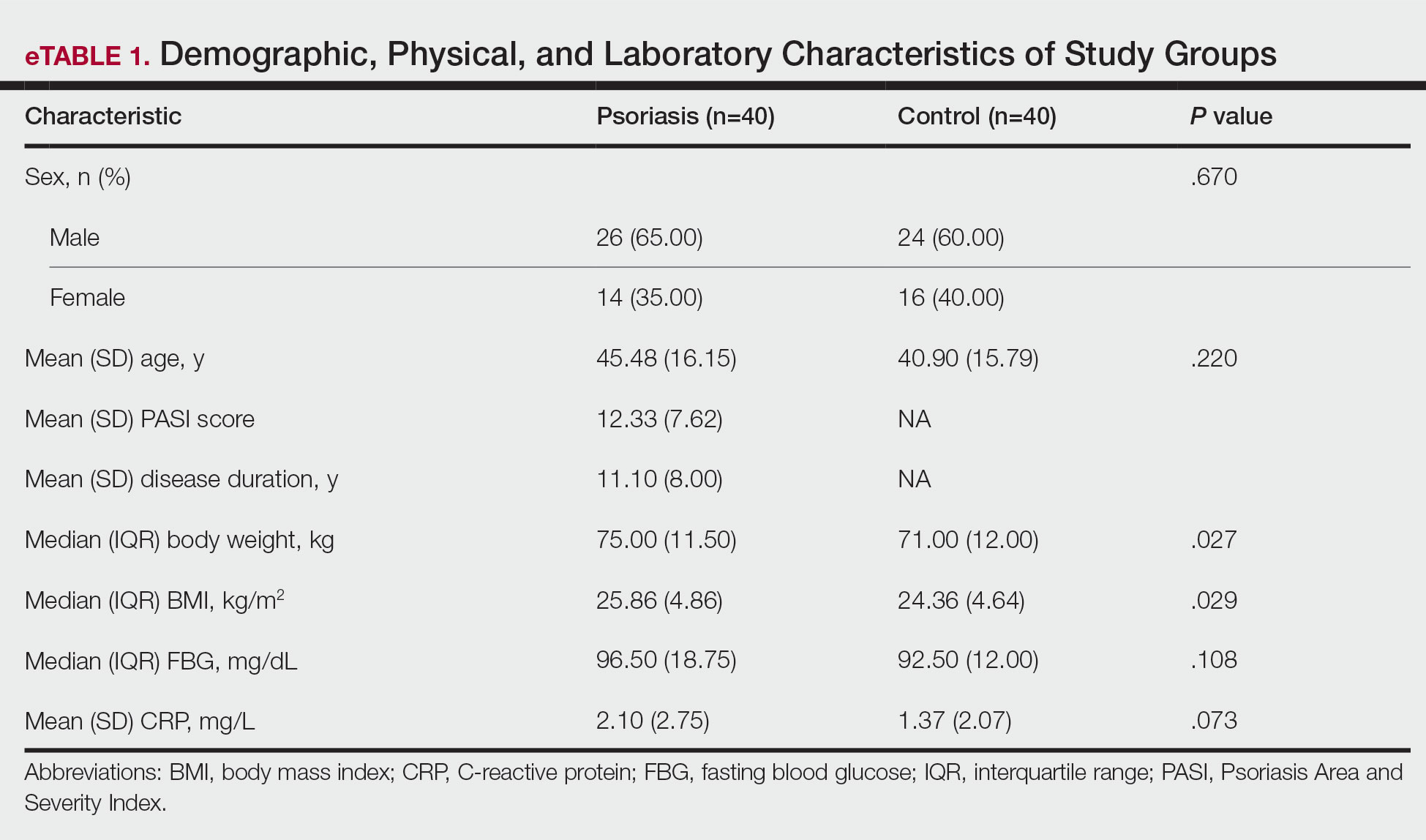

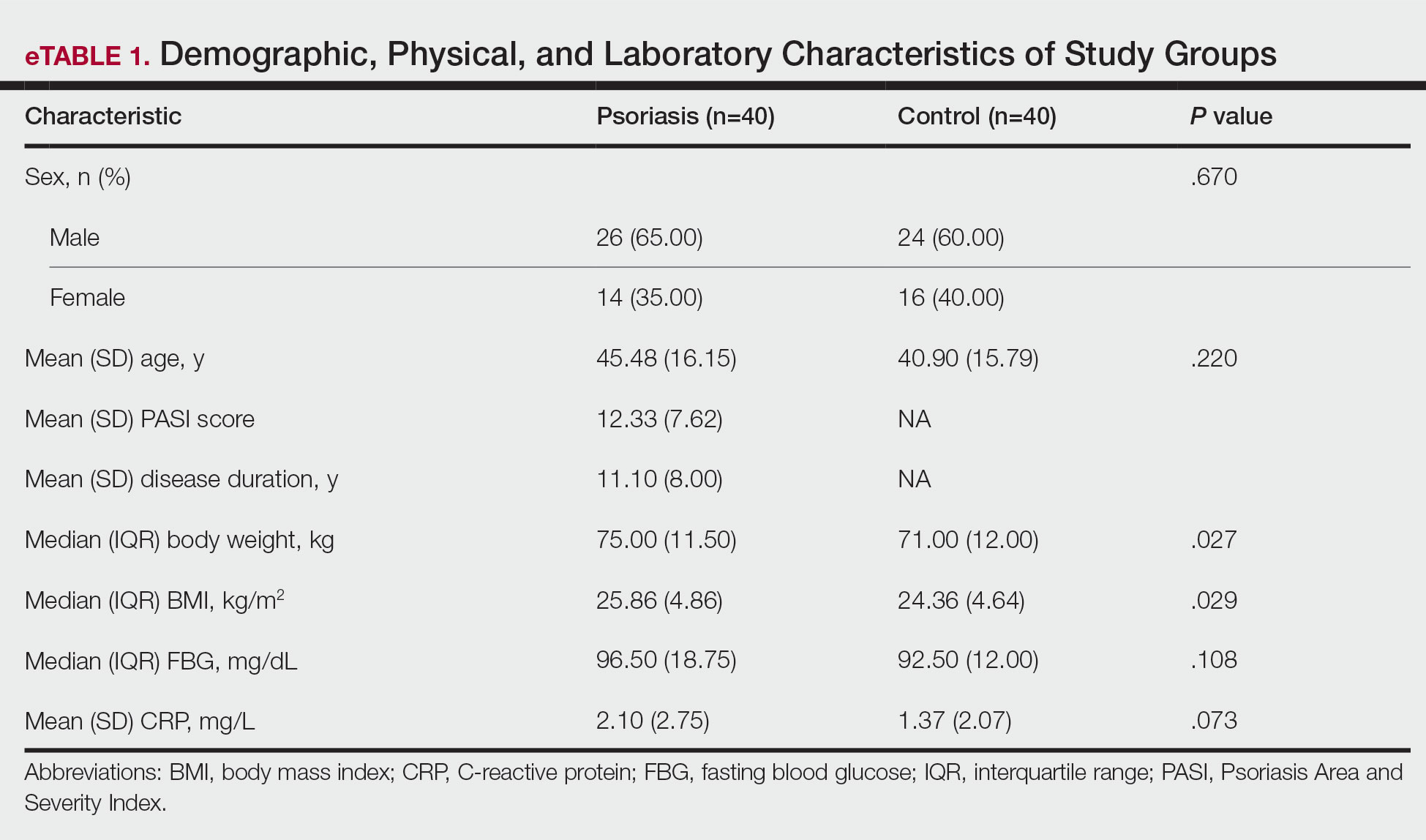

The 2 study groups showed similar demographic characteristics in terms of sex (P=.67) and age (P=.22) distribution. The mean (SD) PASI score in the psoriasis group was 12.33 (7.62); the mean (SD) disease duration was 11.10 (8.00) years. Body weight and BMI were both significantly higher in the psoriasis group (P=.027 and P=.029, respectively) compared with the control group (eTable 1).

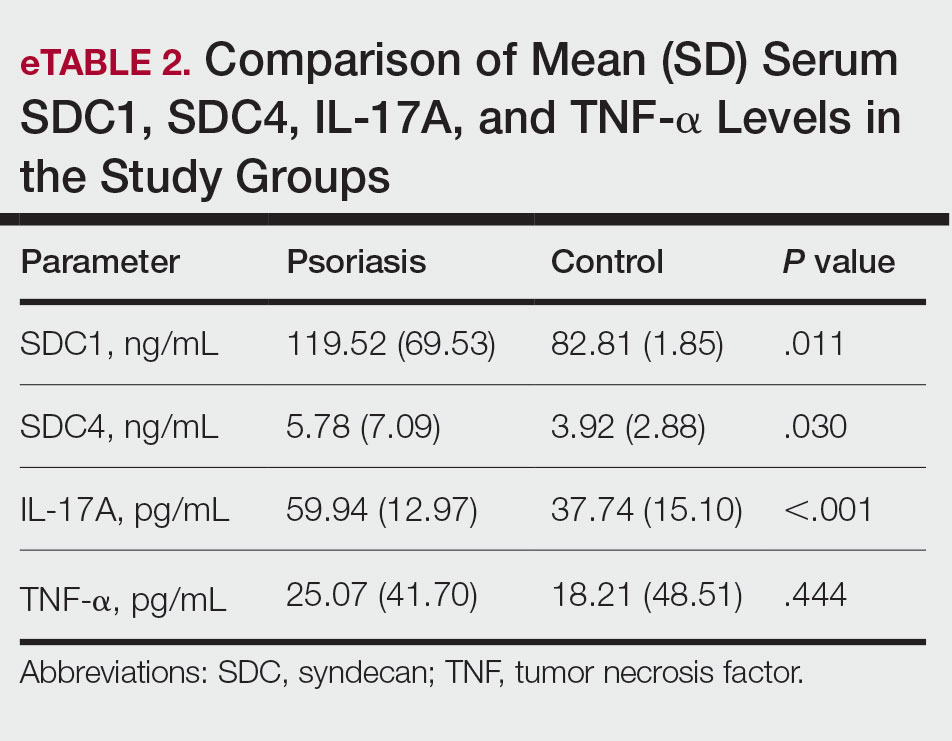

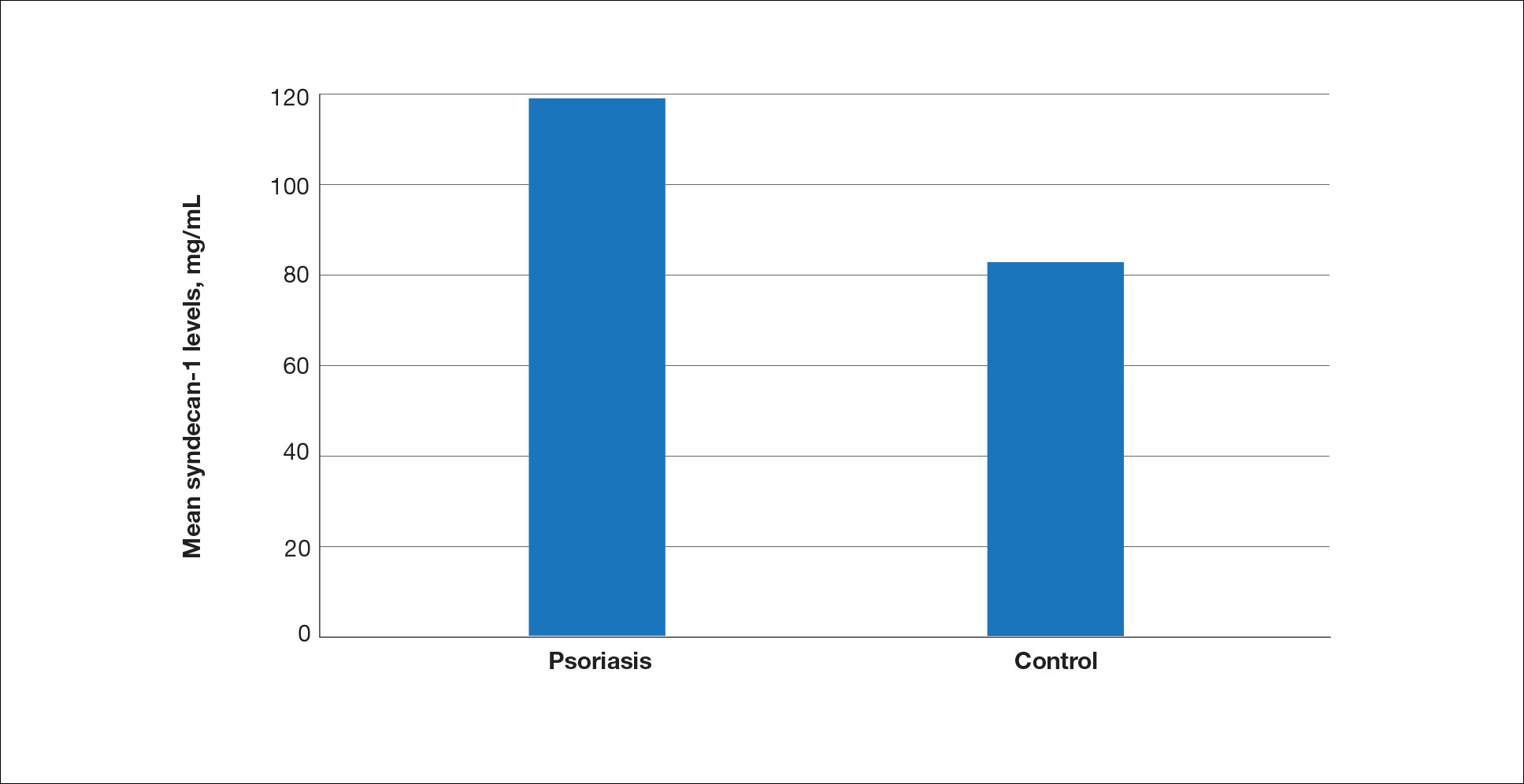

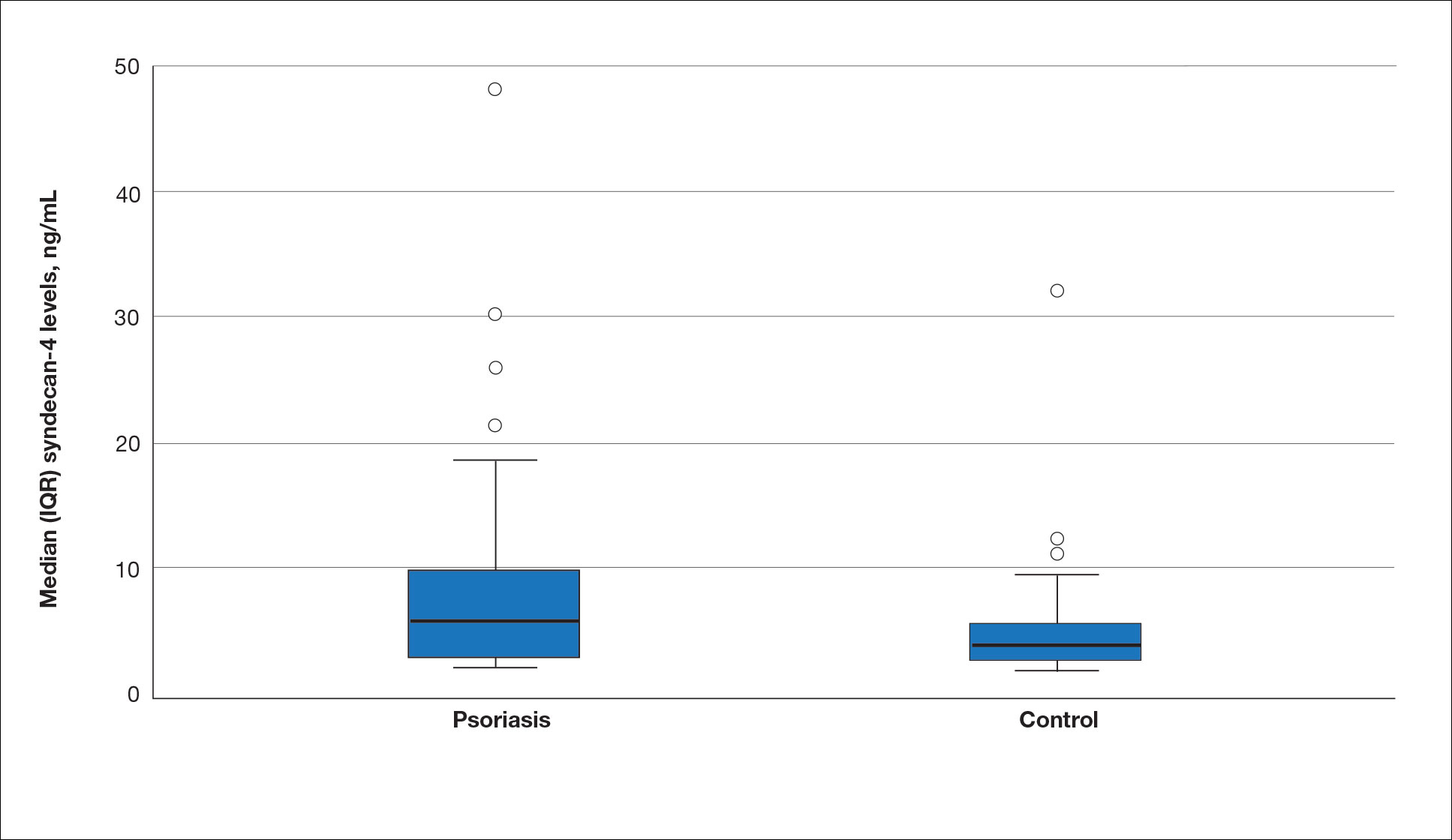

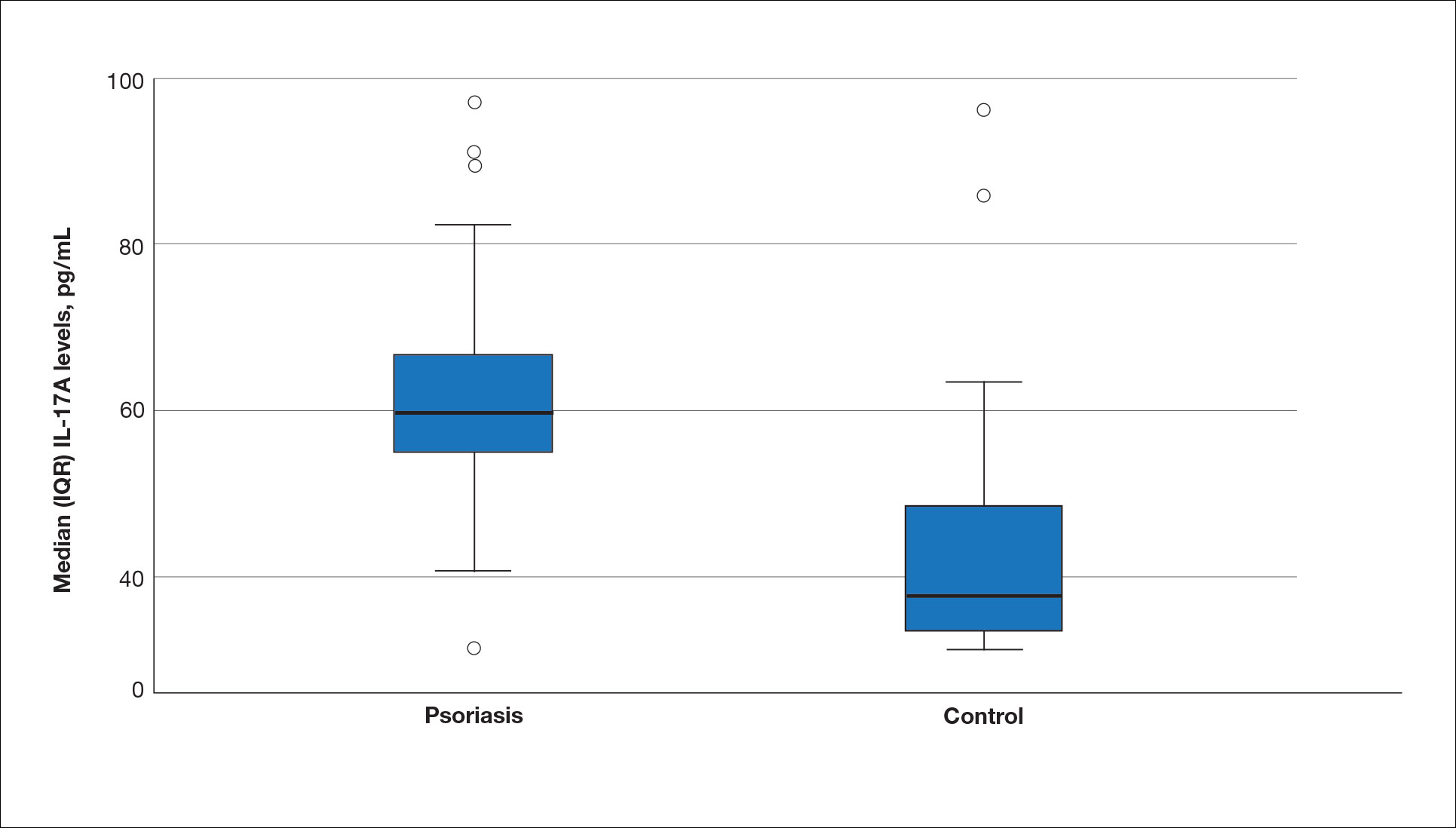

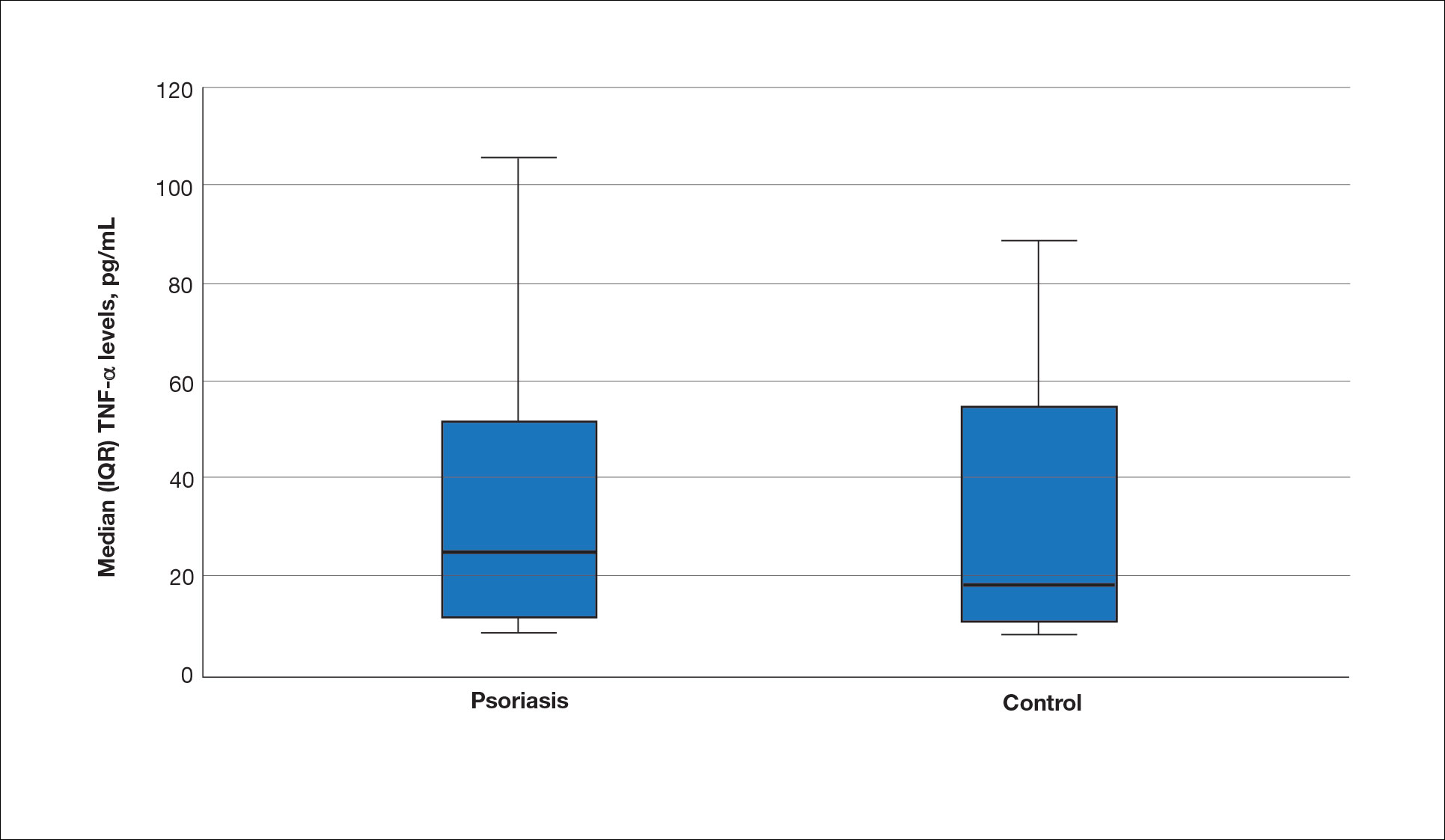

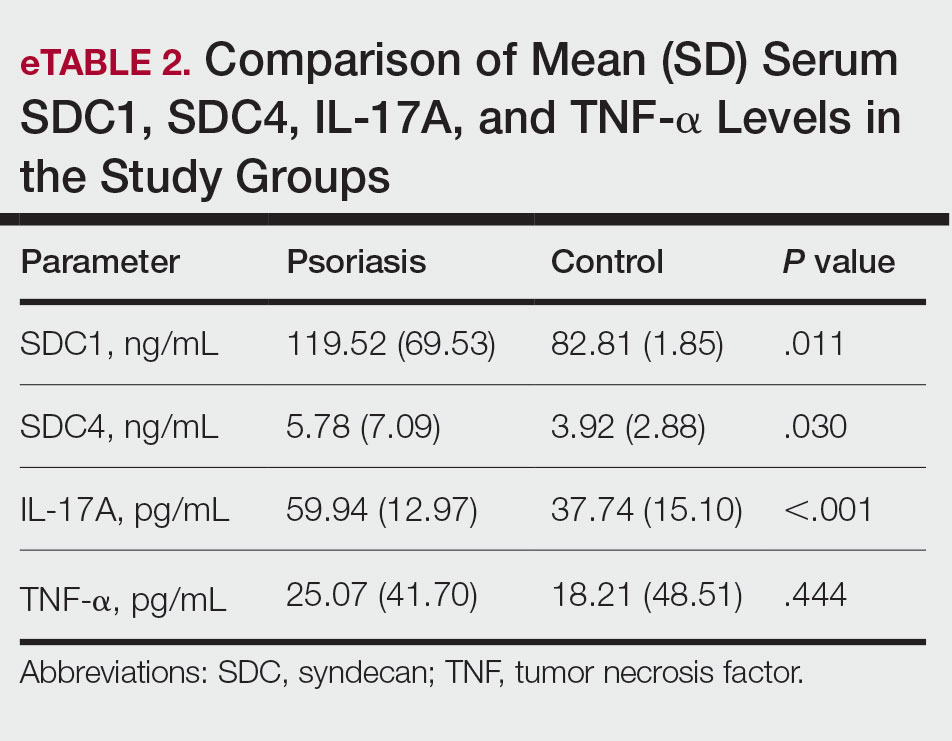

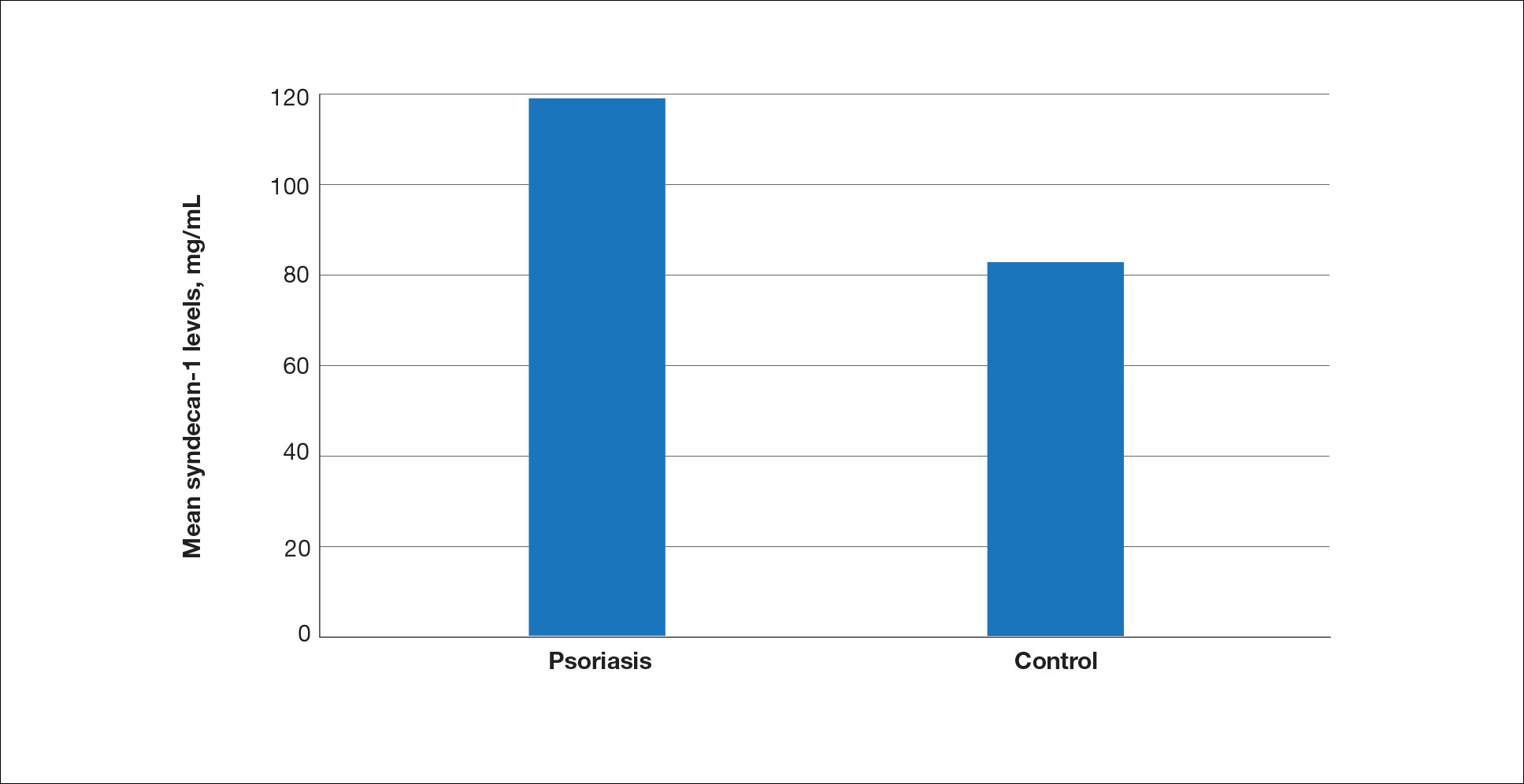

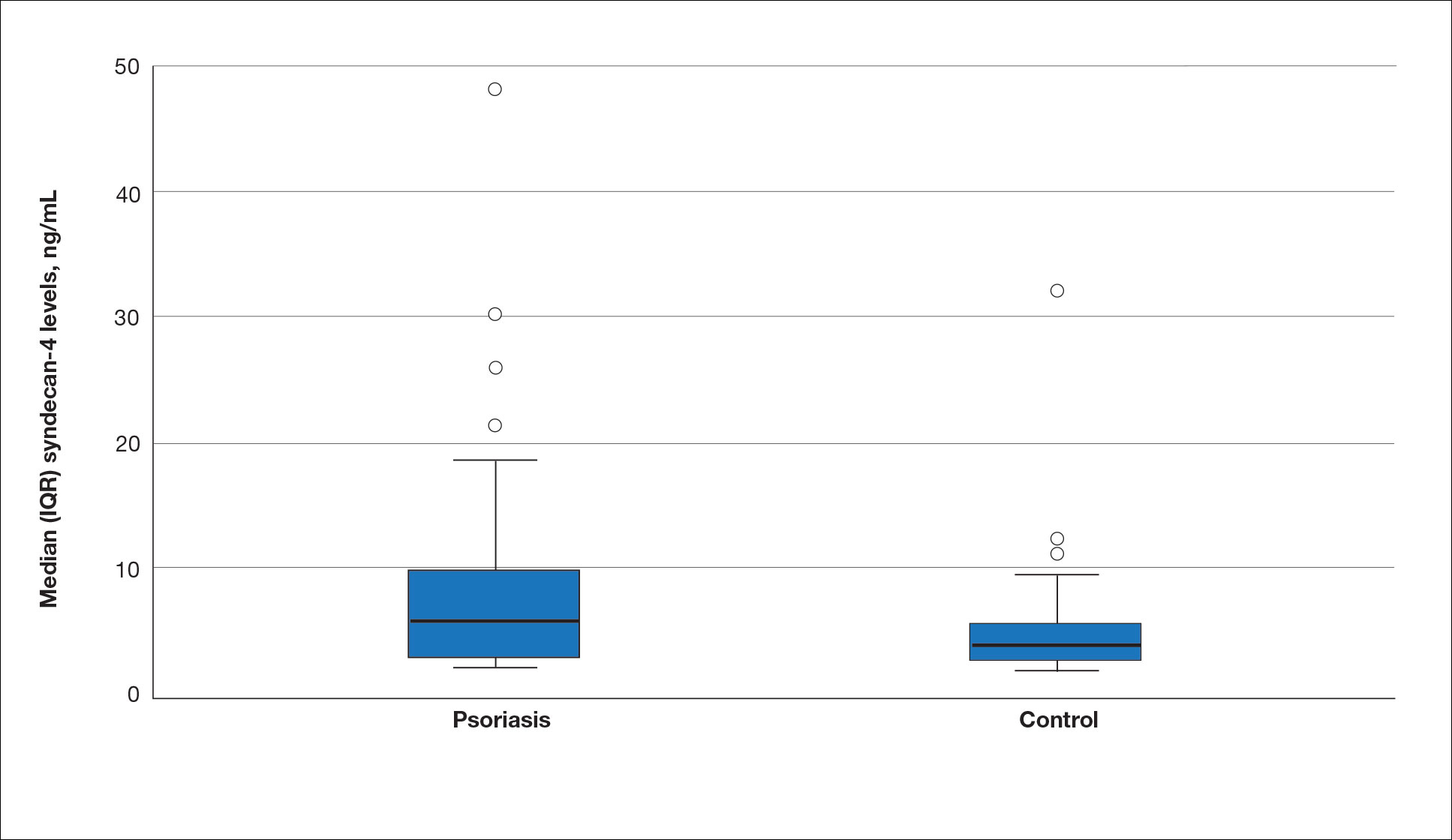

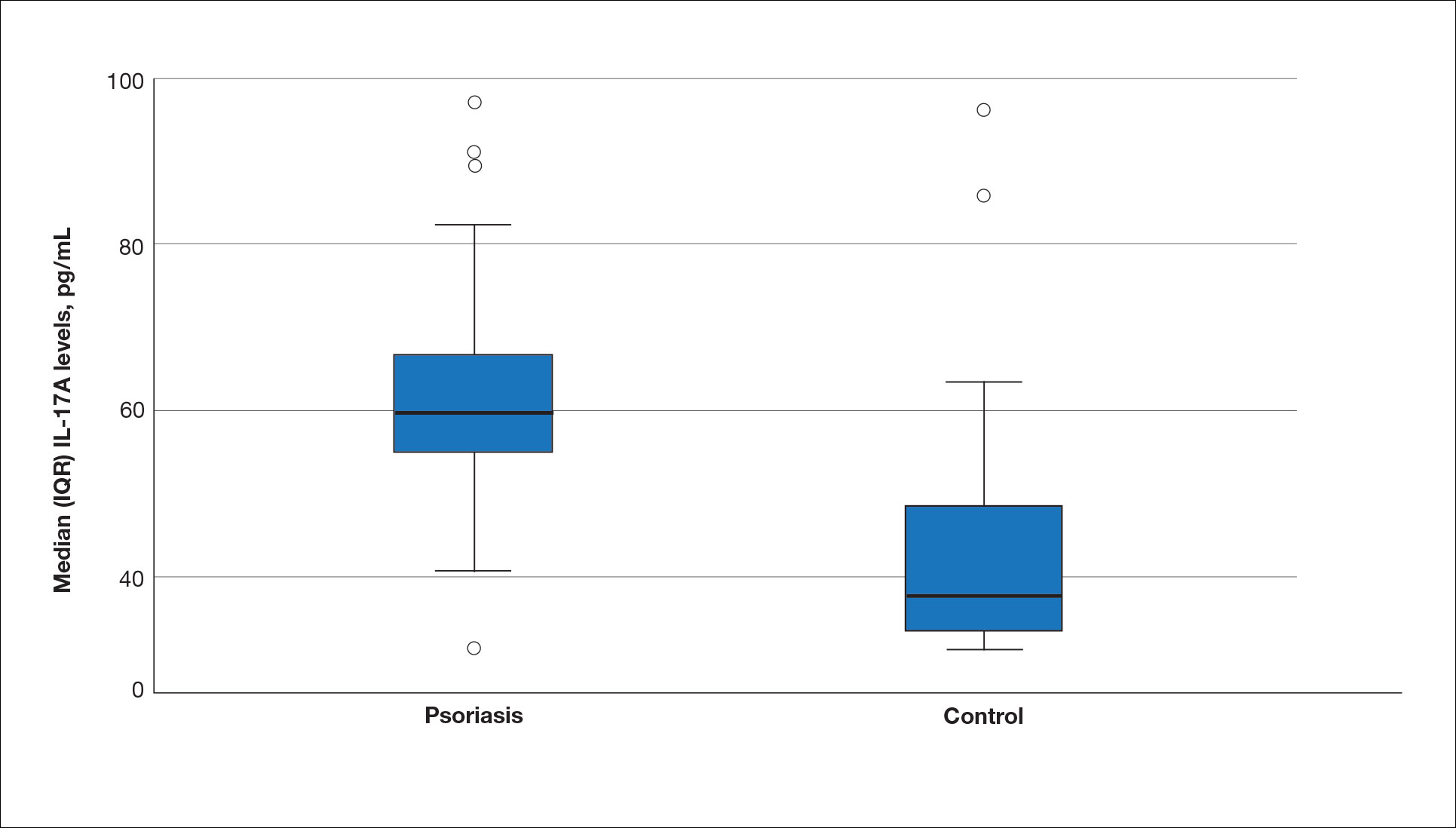

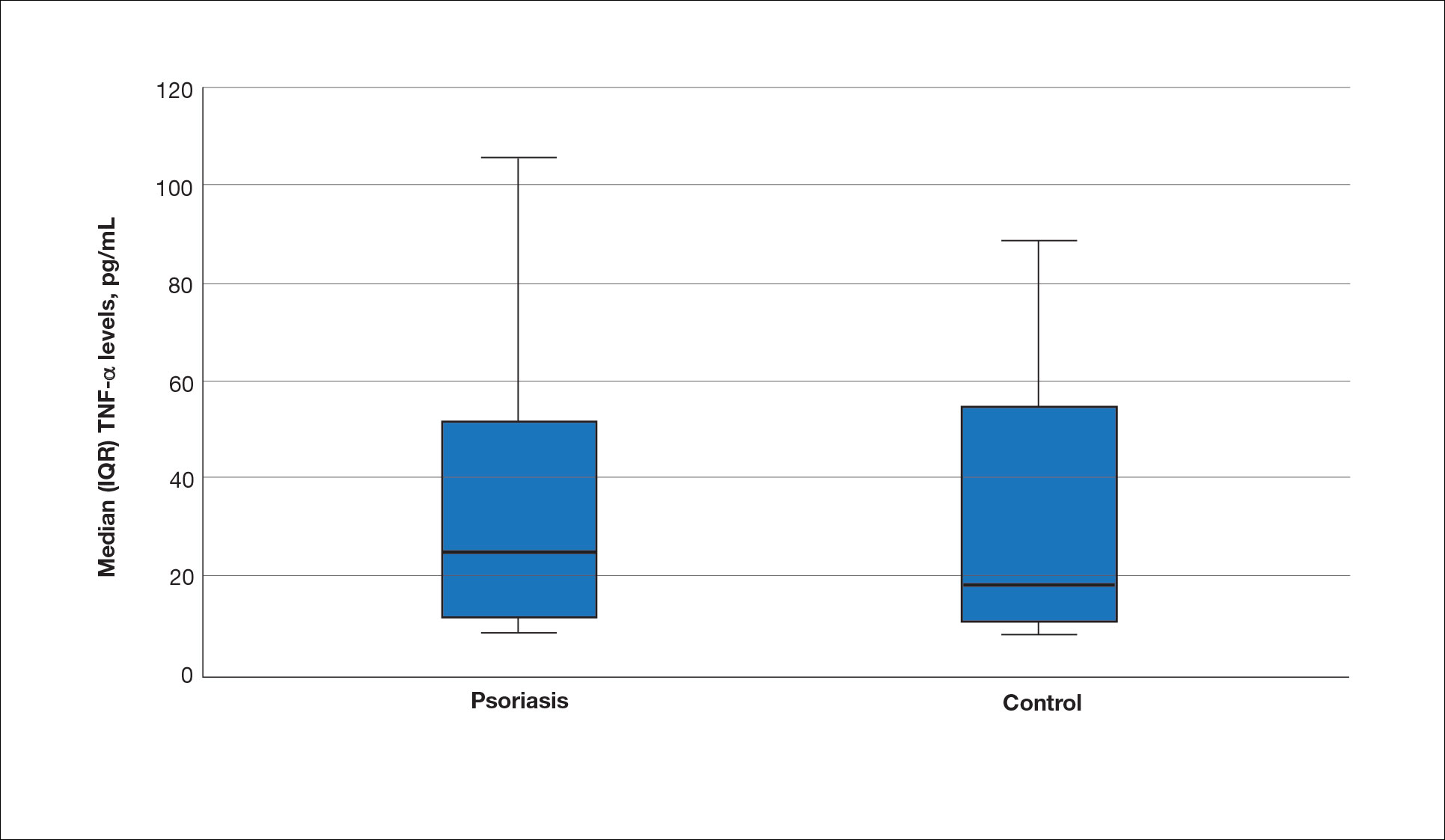

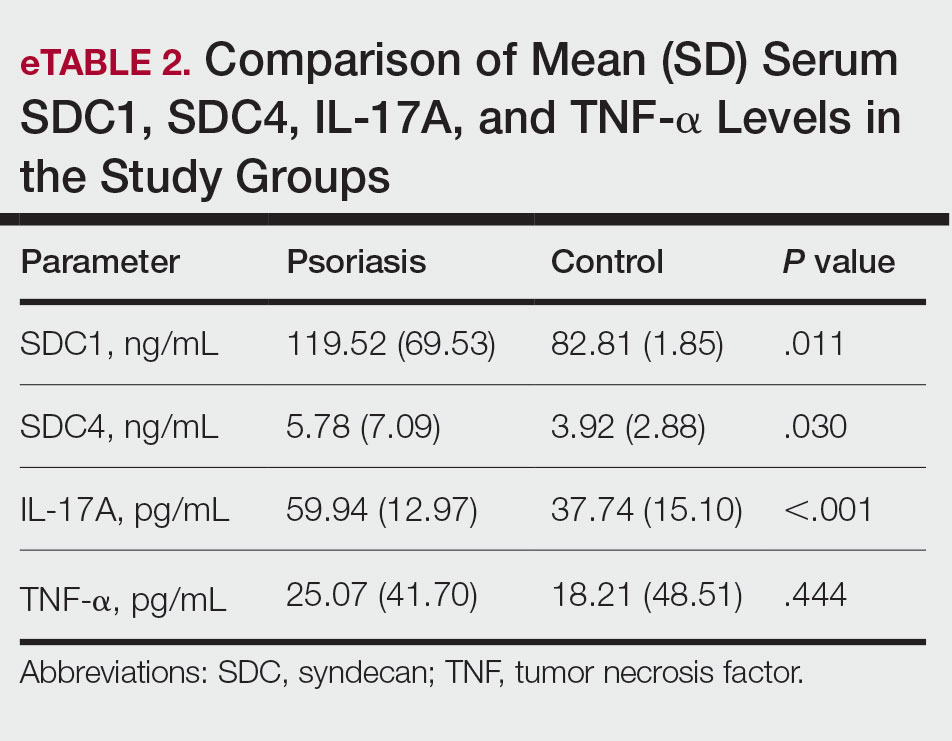

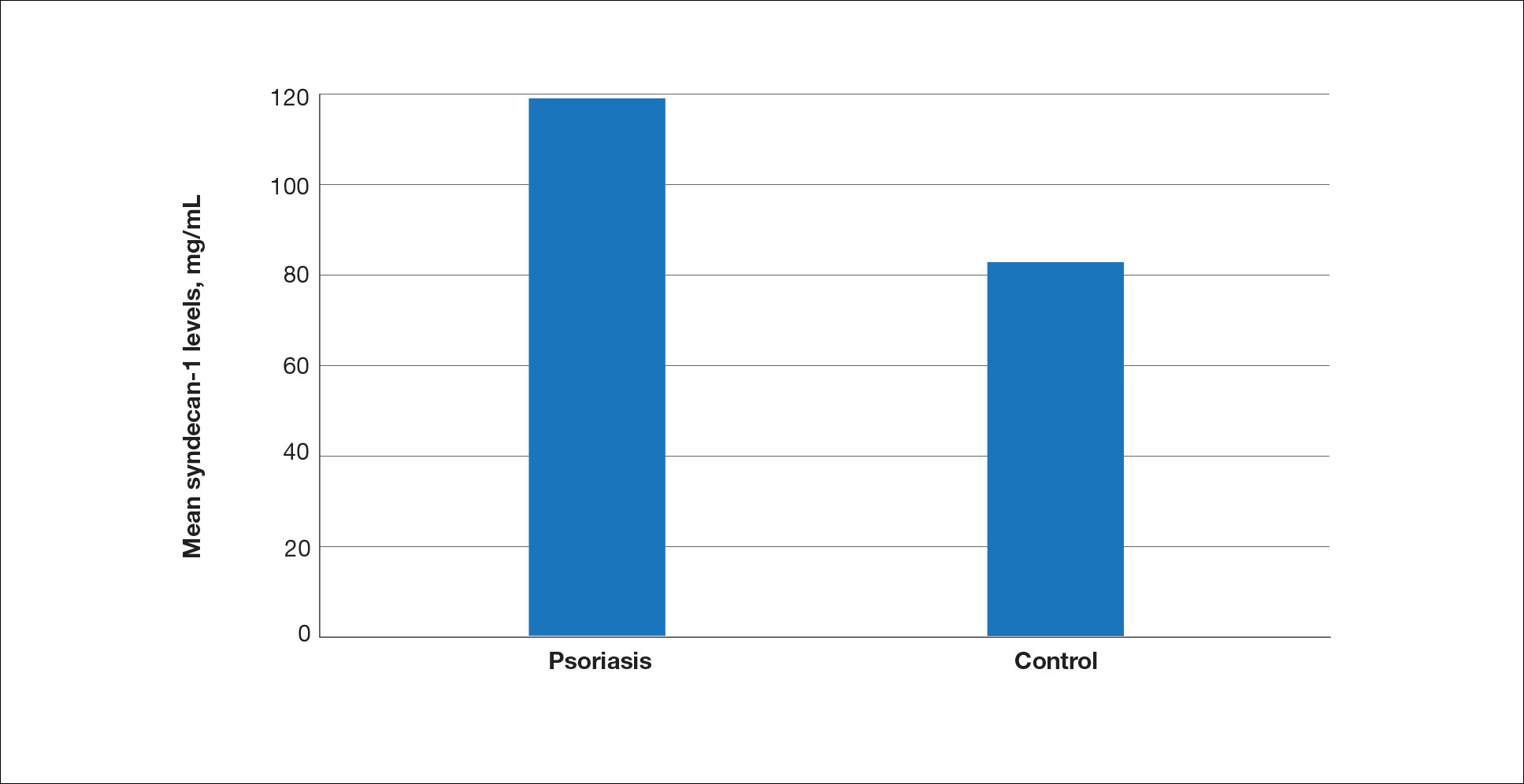

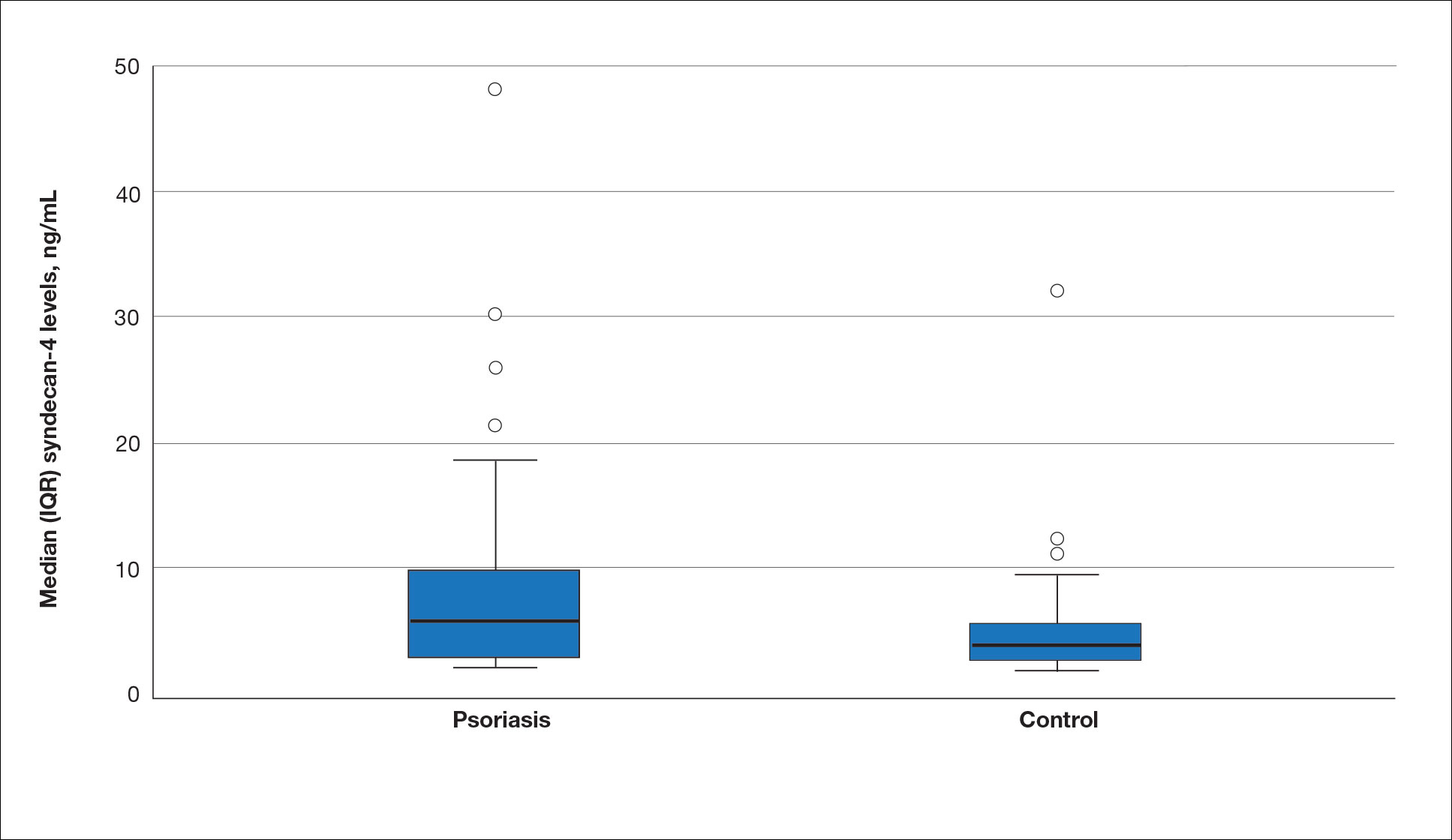

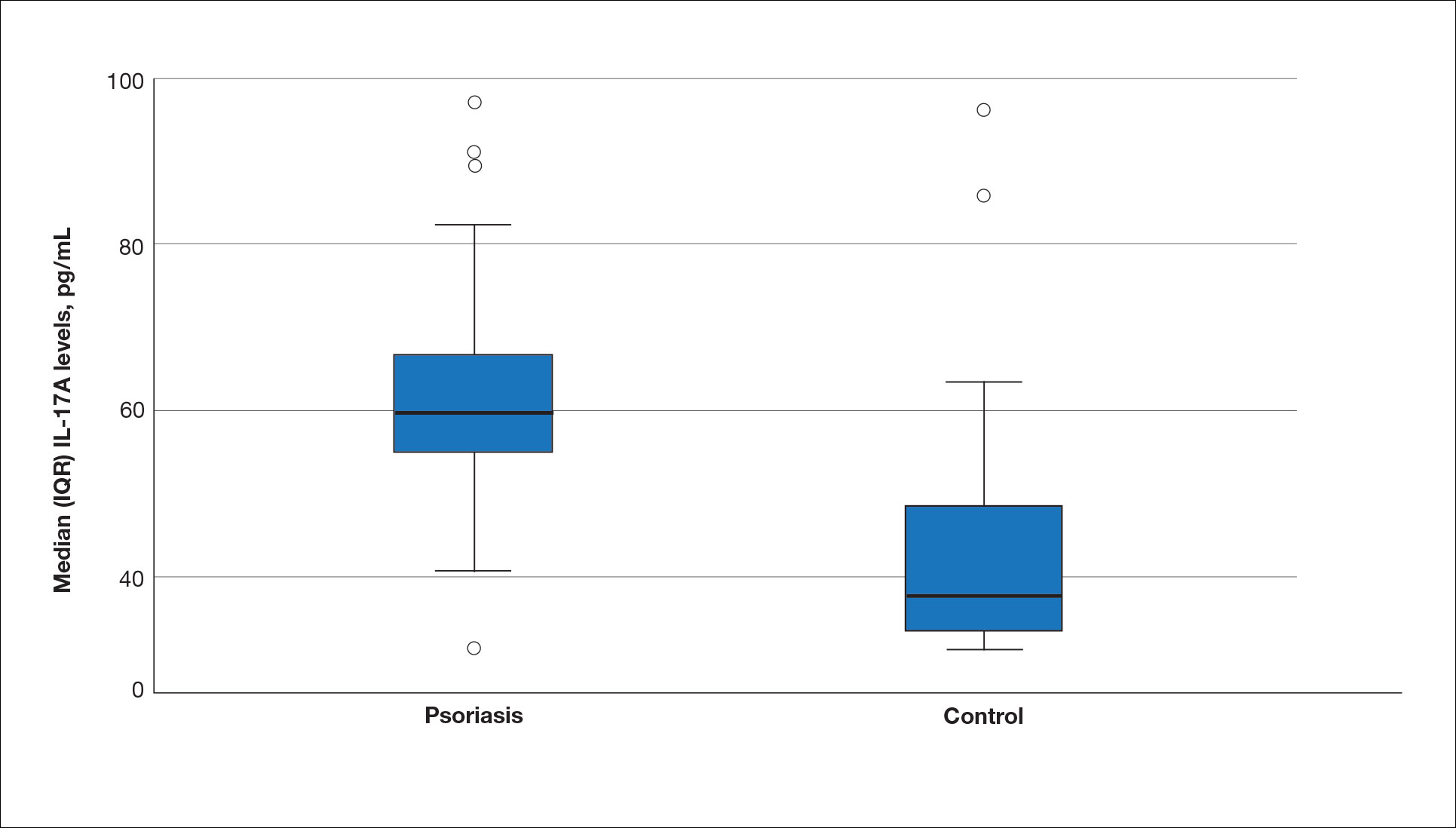

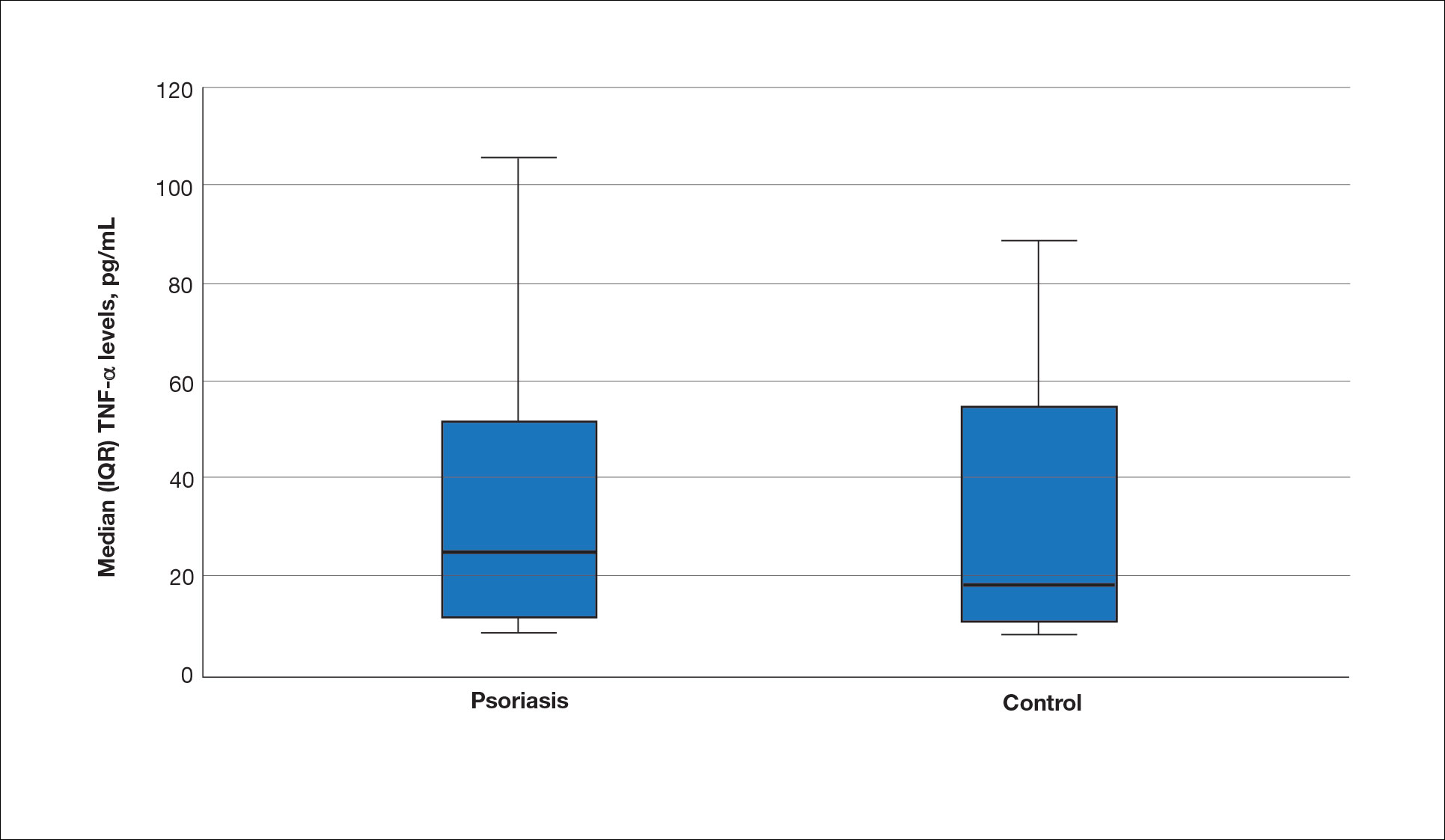

The mean (SD) serum SDC1 level was 119.52 ng/mL (69.53 ng/mL) in the psoriasis group, which was significantly higher than the control group (82.81 ng/mL [51.85 ng/mL])(P=.011)(eTable 2)(eFigure 1). The median (IQR) serum SDC4 level also was significantly higher in the psoriasis group compared with the control group (5.78 ng/mL [7.09 ng/mL] vs 3.92 ng/mL [2.88 ng/mL])(P=.030)(eTable 2)(eFigure 2). The median (IQR) IL-17A value was 59.94 pg/mL (12.97 pg/mL) in the psoriasis group, which was significantly higher than the control group (37.74 pg/mL [15.10 pg/mL])(P<.001)(eTable 2)(eFigure 3). The median (IQR) serum TNF-α level was 25.07 pg/mL (41.70 pg/mL) in the psoriasis group and 18.21 pg/mL (48.51 pg/mL) in the control group; however, the difference was not statistically significance (P=.444)(eTable 2)(eFigure 4).

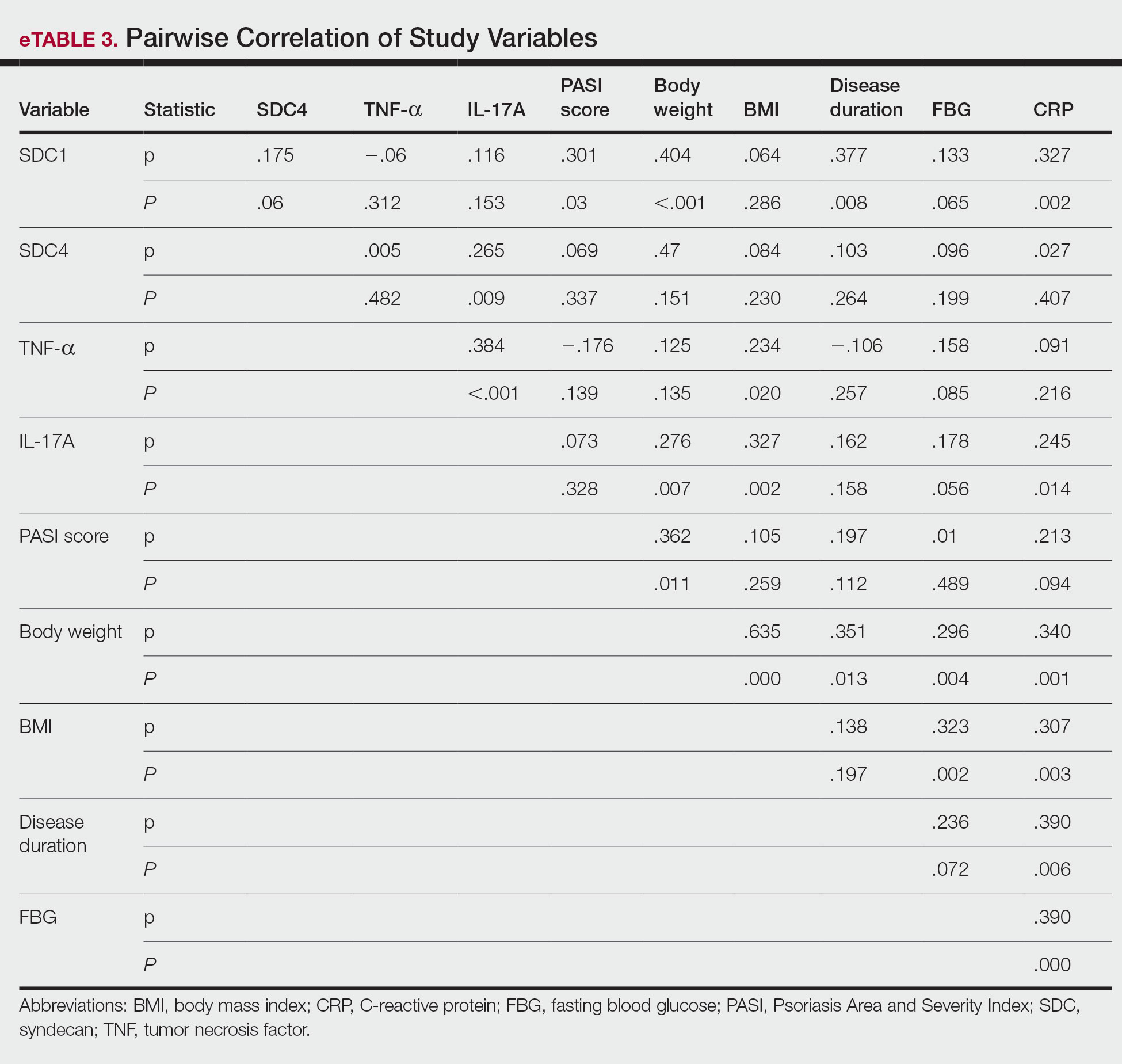

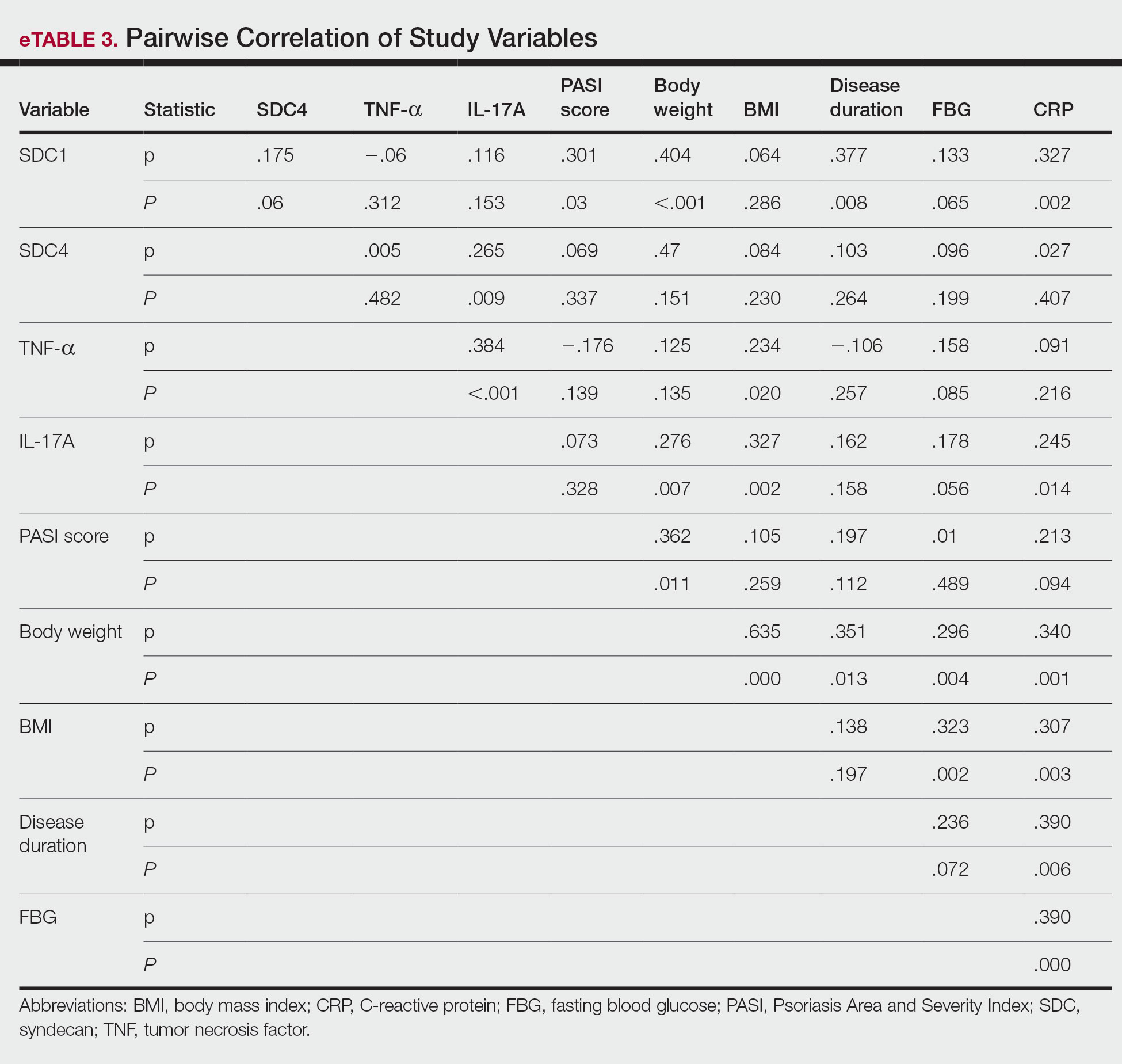

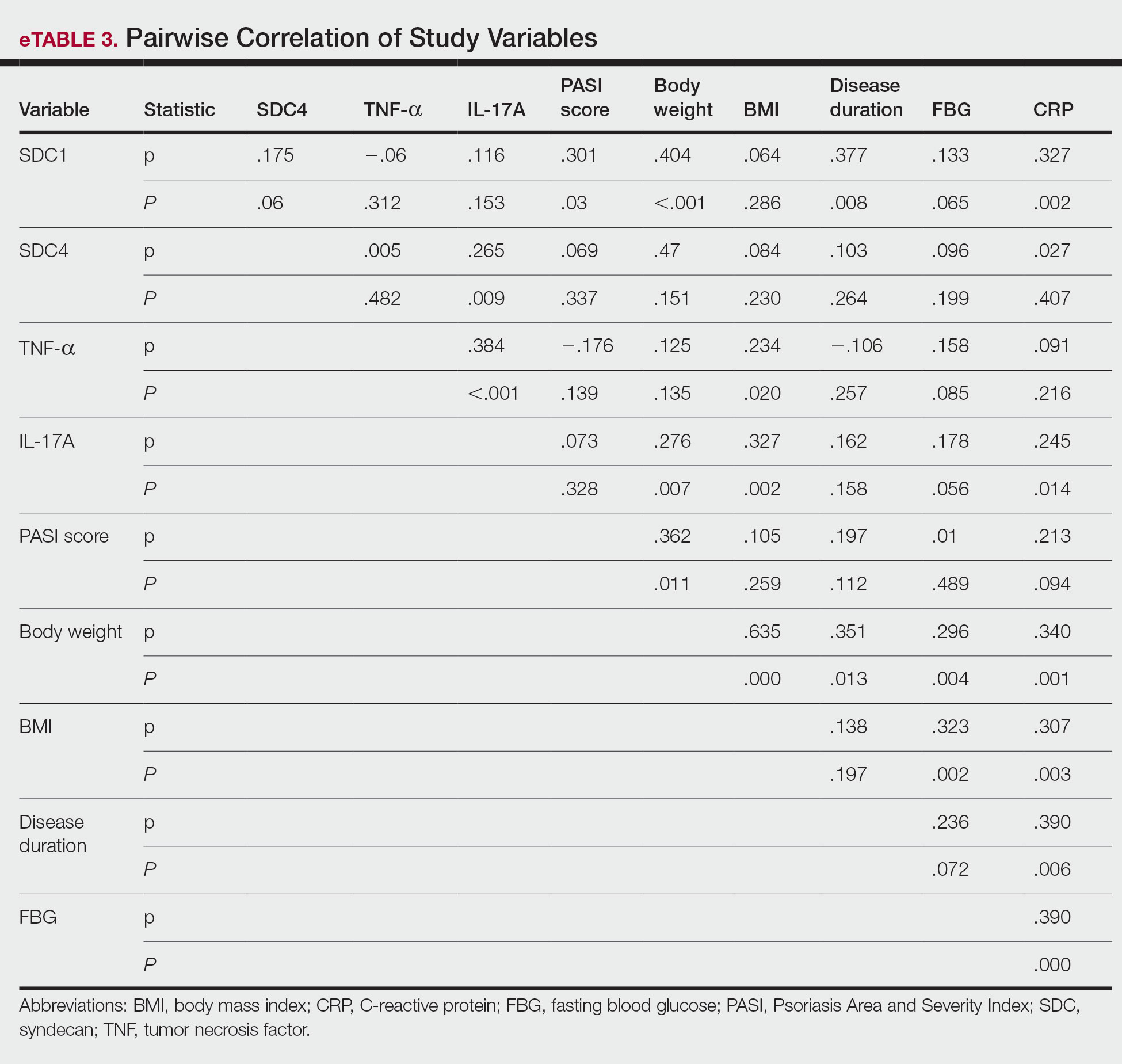

A significant positive correlation was found between serum SDC1 and PASI score (p=0.064; P=.03). Furthermore, significant positive correlations were identified between serum SDC1 and body weight (p=0.404; P<.001), disease duration (p=0.377; P=.008), and C-reactive protein (p=0.327; P=.002). A significant positive correlation also was identified between SDC4 and IL-17A (p=0.265; P=.009). Serum TNF-α was positively correlated with IL-17A (p=0.384; P<.001) and BMI (p=0.234; P=.020)(eTable 3).

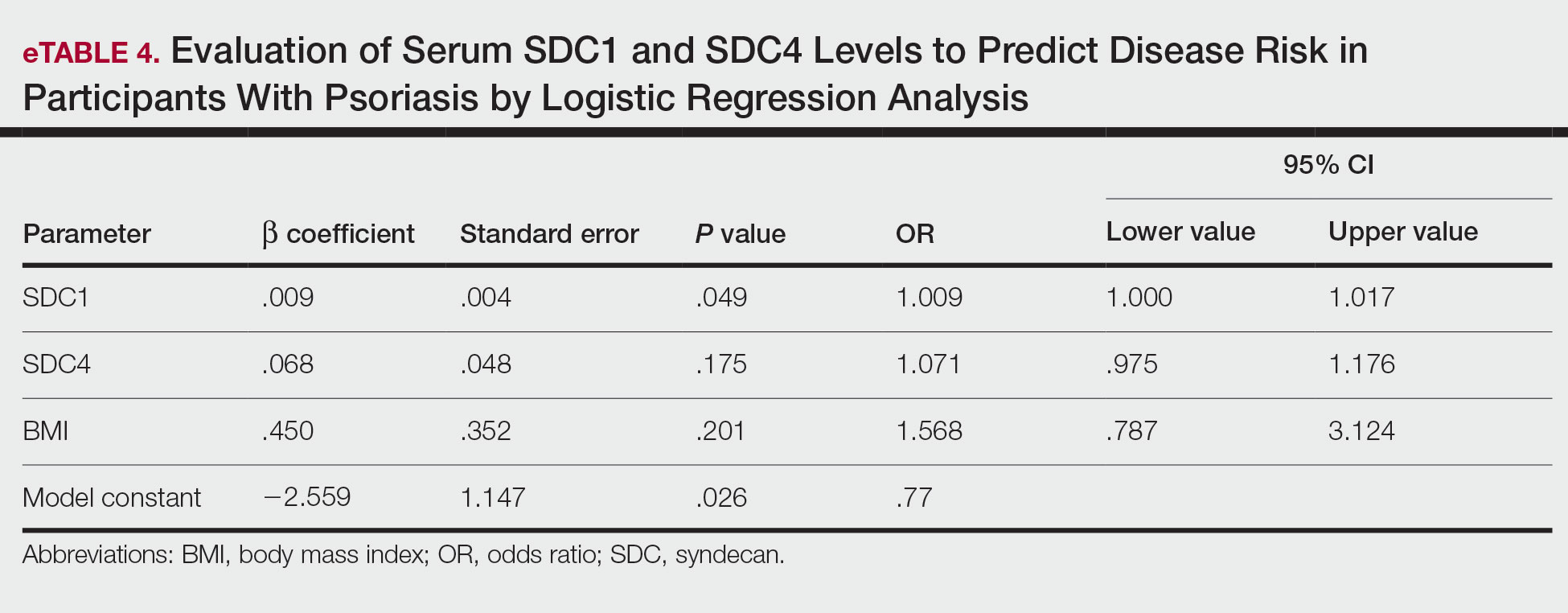

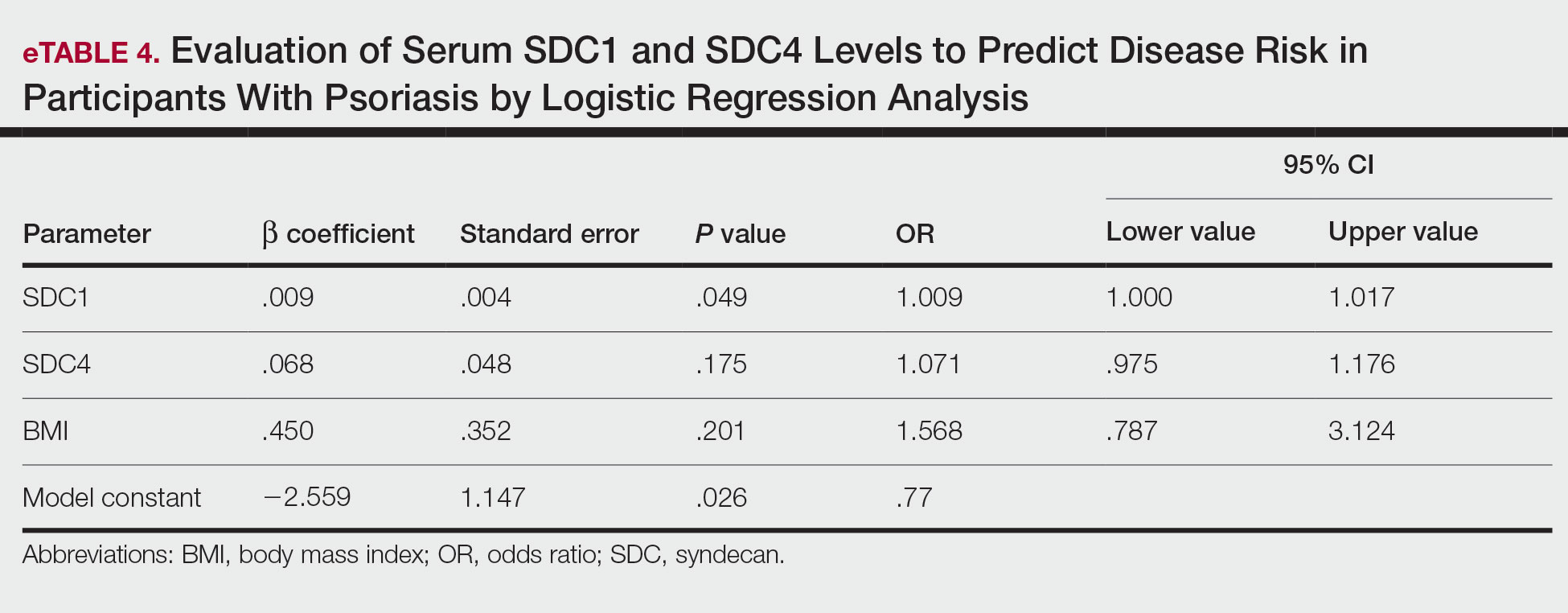

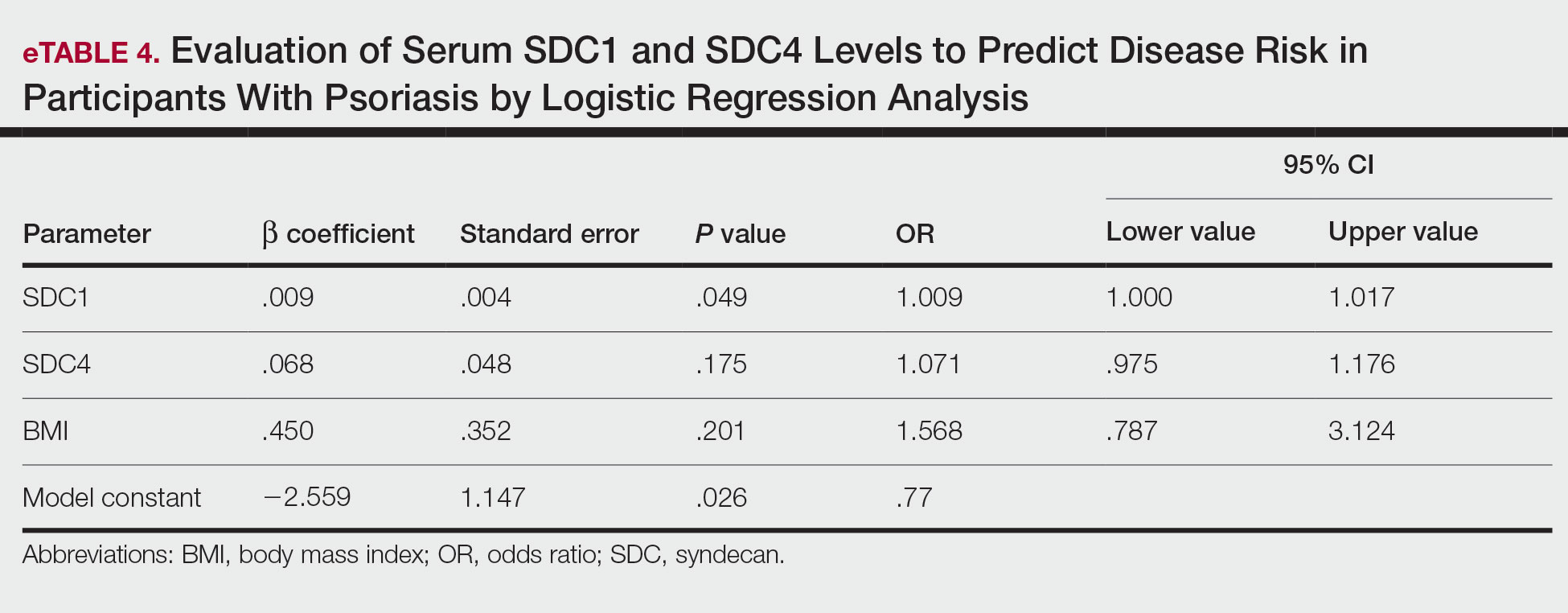

Logistic regression analysis showed that high SDC1 levels were independently associated with the development of psoriasis (odds ratio [OR], 1.009; 95% CI, 1.000-1.017; P=.049)(eTable 4).

Comment

Tumor necrosis factor α and IL-17A are key cytokines whose roles in the pathogenesis of psoriasis are well established. Arican et al,8 Kyriakou et al,9 and Xuan et al10 previously reported a lack of any correlation between TNF-α and IL-17A in the pathogenesis of psoriasis; however, we observed a positive correlation between TNF-α and IL-17A in our study. This finding may be due to the abundant TNF-α production by myeloid dendritic cells involved in the transformation of naive T lymphocytes into IL-17A–secreting Th17 lymphocytes, which can also secrete TNF-α.

After the molecular cloning of SDCs by Saunders et al11 in 1989, SDCs gained attention and have been the focus of many studies for their part in the pathogenesis of conditions such as inflammatory diseases, carcinogenesis, infections, sepsis, and trauma.6,12 Among the inflammatory diseases sharing similar pathogenetic features to psoriasis, serum SDC4 levels are found to be elevated in rheumatoid arthritis and are correlated with disease activity.13 Cekic et al14 reported that serum SDC1 levels were significantly higher in patients with Crohn disease than controls (P=.03). Additionally, serum SDC1 levels were higher in patients with active disease compared with those who were in remission. Correlations between SDC1 and disease severity and C-reactive protein also have been found.14 Serum SDC-1 levels found to be elevated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus were compared to the controls and were correlated with disease activity.15 Nakao et al16 reported that the serum SDC4 levels were significantly higher in patients with atopic dermatitis compared to controls (P<.01); further, SDC4 levels were correlated with severity of the disease.

Jaiswal et al17 reported that SDC1 is abundant on the surface of IL-17A–secreting γδ T lymphocytes (Tγδ17), whose contribution to psoriasis pathogenesis is known. When subjected to treatment with imiquimod, SDC1-suppressed mice displayed increased psoriasiform dermatitis compared with wild-type counterparts. The authors stated that SDC1 may play a role in controlling homeostasis of Tγδ17

In a study examining changes in the ECM in patients with psoriasis, it was observed that the expression of

A study conducted by Koliakou et al20 showed that, in healthy skin, SDC1 was expressed in almost the full thickness of the epidermis, but lowest expression was in the basal-layer keratinocytes. In a psoriatic epidermis, unlike the normal epidermis, SDC1 was found to be more intensely expressed in the keratinocytes of the basal layer, where keratinocyte proliferation occurs. In this study, SDC4 was expressed mainly at lower levels in a healthy epidermis, especially in the spinous and the basal layers. In a psoriatic epidermis, SDC4 was absent from all the layers. In the same study, gelatin-based carriers containing anti–TNF-α and anti–IL-17A were applied to a full-thickness epidermis with psoriatic lesions, after which SDC1 expression was observed to decrease almost completely in the psoriatic epidermis; there was no change in SDC4 expression, which also was not seen in the psoriatic epidermis. The authors claimed the application of these gelatin-based carriers could be a possible treatment modality for psoriasis, and the study provides evidence for the involvement of SDC1 and/or SDC4 in the pathogenesis of psoriasis

Limitations of the current study include small sample size, lack of longitudinal data, lack of tissue testing of these molecules, and lack of external validation.

Conclusion

Overall, research has shown that SDCs play important roles in inflammatory processes, and more widespread inflammation has been associated with increased shedding of these molecules into the ECM and higher serum levels. In our study, serum SDC1, SDC4, and IL-17A levels were increased in patients with psoriasis compared to the healthy controls. A logistic regression analysis indicated that high serum SDC1 levels may be an independent risk factor for development of psoriasis. The increase in serum SDC1 and SDC4 levels and the positive correlation between SDC1 levels and disease severity observed in our study strongly implicate SDCs in the inflammatory disease psoriasis. The precise role of SDCs in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and the implications of targeting these molecules are the subject of more in-depth studies in the future.

Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

Uings IJ, Farrow SN. Cell receptors and cell signaling. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:295-299.

Kirkpatrick CA, Selleck SB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans at a glance.J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1829-1832.

Stepp MA, Pal-Ghosh S, Tadvalkar G, et al. Syndecan-1 and its expanding list of contacts. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4:235-249.

Rangarajan S, Richter JR, Richter RP, et al. Heparanase-enhanced shedding of syndecan-1 and its role in driving disease pathogenesis and progression. J Histochem Cytochem. 2020;68:823-840.

Gopal S, Arokiasamy S, Pataki C, et al. Syndecan receptors: pericellular regulators in development and inflammatory disease. Open Biol. 2021;11:200377.

Bertrand J, Bollmann M. Soluble syndecans: biomarkers for diseases and therapeutic options. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:67-81.

Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

Kyriakou A, Patsatsi A, Vyzantiadis TA, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IL12/23 p40, and IL-17 in psoriatic patients with and without nail psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:508178.

Xuan ML, Lu CJ, Han L, et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines in patients with psoriasis vulgaris of different Chinese medicine syndromes. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21:108-114.

Saunders S, Jalkanen M, O’Farrell S, et al. Molecular cloning of syndecan, an integral membrane proteoglycan. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1547-1556.

Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. FEBS J. 2010;277:3876-3889.

Zhao J, Ye X, Zhang Z. Syndecan-4 is correlated with disease activity and serological characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Rheumatol. 2022;62:21.

Cekic C, Kırcı A, Vatansever S, et al. Serum syndecan-1 levels and its relationship to disease activity in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:850351.

Minowa K, Amano H, Nakano S, et al. Elevated serum level of circulating syndecan-1 (CD138) in active systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:357-362.

Nakao M, Sugaya M, Takahashi N, et al. Increased syndecan-4 expression in sera and skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:655-660.

Jaiswal AK, Sadasivam M, Archer NK, et al. Syndecan-1 regulates psoriasiform dermatitis by controlling homeostasis of IL-17-producing γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2018;201:1651-1661

Wagner MFMG, Theodoro TR, Filho CASM, et al. Extracellular matrix alterations in the skin of patients affected by psoriasis. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:55.

Peters F, Rahn S, Mengel M, et al. Syndecan-1 shedding by meprin β impairs keratinocyte adhesion and differentiation in hyperkeratosis. Matrix Biol. 2021;102:37-69.

Koliakou E, Eleni MM, Koumentakou I, et al. Altered distribution and expression of syndecan-1 and -4 as an additional hallmark in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6511.

Doss RW, El-Rifaie AA, Said AN, et al. Cutaneous syndecan-1 expression before and after phototherapy in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:439-440.

Psoriasis, one of the most researched diseases in dermatology, has a complex pathogenesis that is not yet fully understood. One of the most important stages of psoriasis pathogenesis is the proliferation of T helper (Th) 17 cells by IL-23 released from myeloid dendritic cells. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α released from Th1 cells and IL-17 and IL-22 released from Th17 cells are known to induce the proliferation of keratinocytes and the release of chemokines responsible for neutrophil chemotaxis.1

Although secondary messengers such as cytokines and chemokines, which provide cell interaction with the extracellular matrix (ECM), have their own specific receptors, it is known that syndecans (SDCs) play a role in ECM and cell interactions and have receptor or coreceptor functions.2 In humans, 4 types of SDCs have been identified (SDC1-SDC4), which are type I transmembrane proteoglycans found in all nucleated cells. Syndecans consist of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan chains that are structurally linked to a core protein sequence. The molecule has cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and extracellular domains.2,3 While SDCs often are described as coreceptors for integrins and growth factor and hormone receptors, they also are capable of acting as signaling receptors by engaging intracellular messengers, including actin-related proteins and protein kinases.4

Prior research has indicated that the release of heparanase from the lysosomes of leukocytes during infection, inflammation, and endothelial damage causes cleavage of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans from the extracellular domains of SDCs. The peptide chains at the SDC core then are separated by matrix metalloproteinases in a process known as shedding. The shed SDCs may have either a stimulating or a suppressive effect on their receptor activity. Several cytokines are known to cause SDC shedding.5,6 Many studies in recent years have reported that SDCs play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, for which serum levels of soluble SDCs can be biomarkers.7

In this study, we aimed to evaluate and compare serum SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels in patients with psoriasis vs healthy controls. Additionally, by reviewing the literature data, we analyzed whether SDCs can be implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and their potential role in this process.

Methods

The study population consisted of 40 patients with psoriasis and 40 healthy controls. Age and sex characteristics were similar between the 2 groups, but weight distribution was not. The psoriasis group included patients older than 18 years who had received a clinical and/or histologic diagnosis, had no systemic disease other than psoriasis in their medical history, and had not used any systemic treatment or phototherapy for the past 3 months. Healthy patients older than 18 years who had no medical history of inflammatory disease were included in the control group. Participants provided signed consent.

Data such as medical history, laboratory findings, and physical specifications were recorded. A Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 10 or lower was considered mild disease, and a score higher than 10 was considered moderate to severe disease. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels.

The data were evaluated using the IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0 statistical package program. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. The conformity of the data to a normal distribution was examined using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean (SD) and nonnormally distributed variables were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Data were compared between the 2 study groups using either a student t test (normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (nonnormal distribution). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Categorical data were compared using a χ2 test. Associations among SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, IL-17A, and other variables were assessed using Spearman rank correlation. A binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether serum SDC1 and SDC4 levels were independent risk factors for psoriasis.

Results

The 2 study groups showed similar demographic characteristics in terms of sex (P=.67) and age (P=.22) distribution. The mean (SD) PASI score in the psoriasis group was 12.33 (7.62); the mean (SD) disease duration was 11.10 (8.00) years. Body weight and BMI were both significantly higher in the psoriasis group (P=.027 and P=.029, respectively) compared with the control group (eTable 1).

The mean (SD) serum SDC1 level was 119.52 ng/mL (69.53 ng/mL) in the psoriasis group, which was significantly higher than the control group (82.81 ng/mL [51.85 ng/mL])(P=.011)(eTable 2)(eFigure 1). The median (IQR) serum SDC4 level also was significantly higher in the psoriasis group compared with the control group (5.78 ng/mL [7.09 ng/mL] vs 3.92 ng/mL [2.88 ng/mL])(P=.030)(eTable 2)(eFigure 2). The median (IQR) IL-17A value was 59.94 pg/mL (12.97 pg/mL) in the psoriasis group, which was significantly higher than the control group (37.74 pg/mL [15.10 pg/mL])(P<.001)(eTable 2)(eFigure 3). The median (IQR) serum TNF-α level was 25.07 pg/mL (41.70 pg/mL) in the psoriasis group and 18.21 pg/mL (48.51 pg/mL) in the control group; however, the difference was not statistically significance (P=.444)(eTable 2)(eFigure 4).

A significant positive correlation was found between serum SDC1 and PASI score (p=0.064; P=.03). Furthermore, significant positive correlations were identified between serum SDC1 and body weight (p=0.404; P<.001), disease duration (p=0.377; P=.008), and C-reactive protein (p=0.327; P=.002). A significant positive correlation also was identified between SDC4 and IL-17A (p=0.265; P=.009). Serum TNF-α was positively correlated with IL-17A (p=0.384; P<.001) and BMI (p=0.234; P=.020)(eTable 3).

Logistic regression analysis showed that high SDC1 levels were independently associated with the development of psoriasis (odds ratio [OR], 1.009; 95% CI, 1.000-1.017; P=.049)(eTable 4).

Comment

Tumor necrosis factor α and IL-17A are key cytokines whose roles in the pathogenesis of psoriasis are well established. Arican et al,8 Kyriakou et al,9 and Xuan et al10 previously reported a lack of any correlation between TNF-α and IL-17A in the pathogenesis of psoriasis; however, we observed a positive correlation between TNF-α and IL-17A in our study. This finding may be due to the abundant TNF-α production by myeloid dendritic cells involved in the transformation of naive T lymphocytes into IL-17A–secreting Th17 lymphocytes, which can also secrete TNF-α.

After the molecular cloning of SDCs by Saunders et al11 in 1989, SDCs gained attention and have been the focus of many studies for their part in the pathogenesis of conditions such as inflammatory diseases, carcinogenesis, infections, sepsis, and trauma.6,12 Among the inflammatory diseases sharing similar pathogenetic features to psoriasis, serum SDC4 levels are found to be elevated in rheumatoid arthritis and are correlated with disease activity.13 Cekic et al14 reported that serum SDC1 levels were significantly higher in patients with Crohn disease than controls (P=.03). Additionally, serum SDC1 levels were higher in patients with active disease compared with those who were in remission. Correlations between SDC1 and disease severity and C-reactive protein also have been found.14 Serum SDC-1 levels found to be elevated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus were compared to the controls and were correlated with disease activity.15 Nakao et al16 reported that the serum SDC4 levels were significantly higher in patients with atopic dermatitis compared to controls (P<.01); further, SDC4 levels were correlated with severity of the disease.

Jaiswal et al17 reported that SDC1 is abundant on the surface of IL-17A–secreting γδ T lymphocytes (Tγδ17), whose contribution to psoriasis pathogenesis is known. When subjected to treatment with imiquimod, SDC1-suppressed mice displayed increased psoriasiform dermatitis compared with wild-type counterparts. The authors stated that SDC1 may play a role in controlling homeostasis of Tγδ17

In a study examining changes in the ECM in patients with psoriasis, it was observed that the expression of

A study conducted by Koliakou et al20 showed that, in healthy skin, SDC1 was expressed in almost the full thickness of the epidermis, but lowest expression was in the basal-layer keratinocytes. In a psoriatic epidermis, unlike the normal epidermis, SDC1 was found to be more intensely expressed in the keratinocytes of the basal layer, where keratinocyte proliferation occurs. In this study, SDC4 was expressed mainly at lower levels in a healthy epidermis, especially in the spinous and the basal layers. In a psoriatic epidermis, SDC4 was absent from all the layers. In the same study, gelatin-based carriers containing anti–TNF-α and anti–IL-17A were applied to a full-thickness epidermis with psoriatic lesions, after which SDC1 expression was observed to decrease almost completely in the psoriatic epidermis; there was no change in SDC4 expression, which also was not seen in the psoriatic epidermis. The authors claimed the application of these gelatin-based carriers could be a possible treatment modality for psoriasis, and the study provides evidence for the involvement of SDC1 and/or SDC4 in the pathogenesis of psoriasis

Limitations of the current study include small sample size, lack of longitudinal data, lack of tissue testing of these molecules, and lack of external validation.

Conclusion

Overall, research has shown that SDCs play important roles in inflammatory processes, and more widespread inflammation has been associated with increased shedding of these molecules into the ECM and higher serum levels. In our study, serum SDC1, SDC4, and IL-17A levels were increased in patients with psoriasis compared to the healthy controls. A logistic regression analysis indicated that high serum SDC1 levels may be an independent risk factor for development of psoriasis. The increase in serum SDC1 and SDC4 levels and the positive correlation between SDC1 levels and disease severity observed in our study strongly implicate SDCs in the inflammatory disease psoriasis. The precise role of SDCs in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and the implications of targeting these molecules are the subject of more in-depth studies in the future.

Psoriasis, one of the most researched diseases in dermatology, has a complex pathogenesis that is not yet fully understood. One of the most important stages of psoriasis pathogenesis is the proliferation of T helper (Th) 17 cells by IL-23 released from myeloid dendritic cells. Cytokines such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF) α released from Th1 cells and IL-17 and IL-22 released from Th17 cells are known to induce the proliferation of keratinocytes and the release of chemokines responsible for neutrophil chemotaxis.1

Although secondary messengers such as cytokines and chemokines, which provide cell interaction with the extracellular matrix (ECM), have their own specific receptors, it is known that syndecans (SDCs) play a role in ECM and cell interactions and have receptor or coreceptor functions.2 In humans, 4 types of SDCs have been identified (SDC1-SDC4), which are type I transmembrane proteoglycans found in all nucleated cells. Syndecans consist of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycan chains that are structurally linked to a core protein sequence. The molecule has cytoplasmic, transmembrane, and extracellular domains.2,3 While SDCs often are described as coreceptors for integrins and growth factor and hormone receptors, they also are capable of acting as signaling receptors by engaging intracellular messengers, including actin-related proteins and protein kinases.4

Prior research has indicated that the release of heparanase from the lysosomes of leukocytes during infection, inflammation, and endothelial damage causes cleavage of heparan sulfate glycosaminoglycans from the extracellular domains of SDCs. The peptide chains at the SDC core then are separated by matrix metalloproteinases in a process known as shedding. The shed SDCs may have either a stimulating or a suppressive effect on their receptor activity. Several cytokines are known to cause SDC shedding.5,6 Many studies in recent years have reported that SDCs play a role in the pathogenesis of inflammatory diseases, for which serum levels of soluble SDCs can be biomarkers.7

In this study, we aimed to evaluate and compare serum SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels in patients with psoriasis vs healthy controls. Additionally, by reviewing the literature data, we analyzed whether SDCs can be implicated in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and their potential role in this process.

Methods

The study population consisted of 40 patients with psoriasis and 40 healthy controls. Age and sex characteristics were similar between the 2 groups, but weight distribution was not. The psoriasis group included patients older than 18 years who had received a clinical and/or histologic diagnosis, had no systemic disease other than psoriasis in their medical history, and had not used any systemic treatment or phototherapy for the past 3 months. Healthy patients older than 18 years who had no medical history of inflammatory disease were included in the control group. Participants provided signed consent.

Data such as medical history, laboratory findings, and physical specifications were recorded. A Psoriasis Area and Severity Index (PASI) score of 10 or lower was considered mild disease, and a score higher than 10 was considered moderate to severe disease. An enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay was used to measure SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, and IL-17A levels.

The data were evaluated using the IBM SPSS Statistics V22.0 statistical package program. A P value of <.05 was considered statistically significant. The conformity of the data to a normal distribution was examined using a Shapiro-Wilk test. Normally distributed variables were expressed as mean (SD) and nonnormally distributed variables were expressed as median (interquartile range [IQR]). Data were compared between the 2 study groups using either a student t test (normal distribution) or Mann-Whitney U test (nonnormal distribution). Categorical variables were expressed as numbers and percentages. Categorical data were compared using a χ2 test. Associations among SDC1, SDC4, TNF-α, IL-17A, and other variables were assessed using Spearman rank correlation. A binary logistic regression analysis was used to determine whether serum SDC1 and SDC4 levels were independent risk factors for psoriasis.

Results

The 2 study groups showed similar demographic characteristics in terms of sex (P=.67) and age (P=.22) distribution. The mean (SD) PASI score in the psoriasis group was 12.33 (7.62); the mean (SD) disease duration was 11.10 (8.00) years. Body weight and BMI were both significantly higher in the psoriasis group (P=.027 and P=.029, respectively) compared with the control group (eTable 1).

The mean (SD) serum SDC1 level was 119.52 ng/mL (69.53 ng/mL) in the psoriasis group, which was significantly higher than the control group (82.81 ng/mL [51.85 ng/mL])(P=.011)(eTable 2)(eFigure 1). The median (IQR) serum SDC4 level also was significantly higher in the psoriasis group compared with the control group (5.78 ng/mL [7.09 ng/mL] vs 3.92 ng/mL [2.88 ng/mL])(P=.030)(eTable 2)(eFigure 2). The median (IQR) IL-17A value was 59.94 pg/mL (12.97 pg/mL) in the psoriasis group, which was significantly higher than the control group (37.74 pg/mL [15.10 pg/mL])(P<.001)(eTable 2)(eFigure 3). The median (IQR) serum TNF-α level was 25.07 pg/mL (41.70 pg/mL) in the psoriasis group and 18.21 pg/mL (48.51 pg/mL) in the control group; however, the difference was not statistically significance (P=.444)(eTable 2)(eFigure 4).

A significant positive correlation was found between serum SDC1 and PASI score (p=0.064; P=.03). Furthermore, significant positive correlations were identified between serum SDC1 and body weight (p=0.404; P<.001), disease duration (p=0.377; P=.008), and C-reactive protein (p=0.327; P=.002). A significant positive correlation also was identified between SDC4 and IL-17A (p=0.265; P=.009). Serum TNF-α was positively correlated with IL-17A (p=0.384; P<.001) and BMI (p=0.234; P=.020)(eTable 3).

Logistic regression analysis showed that high SDC1 levels were independently associated with the development of psoriasis (odds ratio [OR], 1.009; 95% CI, 1.000-1.017; P=.049)(eTable 4).

Comment

Tumor necrosis factor α and IL-17A are key cytokines whose roles in the pathogenesis of psoriasis are well established. Arican et al,8 Kyriakou et al,9 and Xuan et al10 previously reported a lack of any correlation between TNF-α and IL-17A in the pathogenesis of psoriasis; however, we observed a positive correlation between TNF-α and IL-17A in our study. This finding may be due to the abundant TNF-α production by myeloid dendritic cells involved in the transformation of naive T lymphocytes into IL-17A–secreting Th17 lymphocytes, which can also secrete TNF-α.

After the molecular cloning of SDCs by Saunders et al11 in 1989, SDCs gained attention and have been the focus of many studies for their part in the pathogenesis of conditions such as inflammatory diseases, carcinogenesis, infections, sepsis, and trauma.6,12 Among the inflammatory diseases sharing similar pathogenetic features to psoriasis, serum SDC4 levels are found to be elevated in rheumatoid arthritis and are correlated with disease activity.13 Cekic et al14 reported that serum SDC1 levels were significantly higher in patients with Crohn disease than controls (P=.03). Additionally, serum SDC1 levels were higher in patients with active disease compared with those who were in remission. Correlations between SDC1 and disease severity and C-reactive protein also have been found.14 Serum SDC-1 levels found to be elevated in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus were compared to the controls and were correlated with disease activity.15 Nakao et al16 reported that the serum SDC4 levels were significantly higher in patients with atopic dermatitis compared to controls (P<.01); further, SDC4 levels were correlated with severity of the disease.

Jaiswal et al17 reported that SDC1 is abundant on the surface of IL-17A–secreting γδ T lymphocytes (Tγδ17), whose contribution to psoriasis pathogenesis is known. When subjected to treatment with imiquimod, SDC1-suppressed mice displayed increased psoriasiform dermatitis compared with wild-type counterparts. The authors stated that SDC1 may play a role in controlling homeostasis of Tγδ17

In a study examining changes in the ECM in patients with psoriasis, it was observed that the expression of

A study conducted by Koliakou et al20 showed that, in healthy skin, SDC1 was expressed in almost the full thickness of the epidermis, but lowest expression was in the basal-layer keratinocytes. In a psoriatic epidermis, unlike the normal epidermis, SDC1 was found to be more intensely expressed in the keratinocytes of the basal layer, where keratinocyte proliferation occurs. In this study, SDC4 was expressed mainly at lower levels in a healthy epidermis, especially in the spinous and the basal layers. In a psoriatic epidermis, SDC4 was absent from all the layers. In the same study, gelatin-based carriers containing anti–TNF-α and anti–IL-17A were applied to a full-thickness epidermis with psoriatic lesions, after which SDC1 expression was observed to decrease almost completely in the psoriatic epidermis; there was no change in SDC4 expression, which also was not seen in the psoriatic epidermis. The authors claimed the application of these gelatin-based carriers could be a possible treatment modality for psoriasis, and the study provides evidence for the involvement of SDC1 and/or SDC4 in the pathogenesis of psoriasis

Limitations of the current study include small sample size, lack of longitudinal data, lack of tissue testing of these molecules, and lack of external validation.

Conclusion

Overall, research has shown that SDCs play important roles in inflammatory processes, and more widespread inflammation has been associated with increased shedding of these molecules into the ECM and higher serum levels. In our study, serum SDC1, SDC4, and IL-17A levels were increased in patients with psoriasis compared to the healthy controls. A logistic regression analysis indicated that high serum SDC1 levels may be an independent risk factor for development of psoriasis. The increase in serum SDC1 and SDC4 levels and the positive correlation between SDC1 levels and disease severity observed in our study strongly implicate SDCs in the inflammatory disease psoriasis. The precise role of SDCs in the pathogenesis of psoriasis and the implications of targeting these molecules are the subject of more in-depth studies in the future.

Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

Uings IJ, Farrow SN. Cell receptors and cell signaling. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:295-299.

Kirkpatrick CA, Selleck SB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans at a glance.J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1829-1832.

Stepp MA, Pal-Ghosh S, Tadvalkar G, et al. Syndecan-1 and its expanding list of contacts. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4:235-249.

Rangarajan S, Richter JR, Richter RP, et al. Heparanase-enhanced shedding of syndecan-1 and its role in driving disease pathogenesis and progression. J Histochem Cytochem. 2020;68:823-840.

Gopal S, Arokiasamy S, Pataki C, et al. Syndecan receptors: pericellular regulators in development and inflammatory disease. Open Biol. 2021;11:200377.

Bertrand J, Bollmann M. Soluble syndecans: biomarkers for diseases and therapeutic options. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:67-81.

Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

Kyriakou A, Patsatsi A, Vyzantiadis TA, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IL12/23 p40, and IL-17 in psoriatic patients with and without nail psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:508178.

Xuan ML, Lu CJ, Han L, et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines in patients with psoriasis vulgaris of different Chinese medicine syndromes. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21:108-114.

Saunders S, Jalkanen M, O’Farrell S, et al. Molecular cloning of syndecan, an integral membrane proteoglycan. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1547-1556.

Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. FEBS J. 2010;277:3876-3889.

Zhao J, Ye X, Zhang Z. Syndecan-4 is correlated with disease activity and serological characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Rheumatol. 2022;62:21.

Cekic C, Kırcı A, Vatansever S, et al. Serum syndecan-1 levels and its relationship to disease activity in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:850351.

Minowa K, Amano H, Nakano S, et al. Elevated serum level of circulating syndecan-1 (CD138) in active systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:357-362.

Nakao M, Sugaya M, Takahashi N, et al. Increased syndecan-4 expression in sera and skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:655-660.

Jaiswal AK, Sadasivam M, Archer NK, et al. Syndecan-1 regulates psoriasiform dermatitis by controlling homeostasis of IL-17-producing γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2018;201:1651-1661

Wagner MFMG, Theodoro TR, Filho CASM, et al. Extracellular matrix alterations in the skin of patients affected by psoriasis. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:55.

Peters F, Rahn S, Mengel M, et al. Syndecan-1 shedding by meprin β impairs keratinocyte adhesion and differentiation in hyperkeratosis. Matrix Biol. 2021;102:37-69.

Koliakou E, Eleni MM, Koumentakou I, et al. Altered distribution and expression of syndecan-1 and -4 as an additional hallmark in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6511.

Doss RW, El-Rifaie AA, Said AN, et al. Cutaneous syndecan-1 expression before and after phototherapy in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:439-440.

Griffiths CEM, Armstrong AW, Gudjonsson JE, et al. Psoriasis. Lancet. 2021;397:1301-1315.

Uings IJ, Farrow SN. Cell receptors and cell signaling. Mol Pathol. 2000;53:295-299.

Kirkpatrick CA, Selleck SB. Heparan sulfate proteoglycans at a glance.J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1829-1832.

Stepp MA, Pal-Ghosh S, Tadvalkar G, et al. Syndecan-1 and its expanding list of contacts. Adv Wound Care (New Rochelle). 2015;4:235-249.

Rangarajan S, Richter JR, Richter RP, et al. Heparanase-enhanced shedding of syndecan-1 and its role in driving disease pathogenesis and progression. J Histochem Cytochem. 2020;68:823-840.

Gopal S, Arokiasamy S, Pataki C, et al. Syndecan receptors: pericellular regulators in development and inflammatory disease. Open Biol. 2021;11:200377.

Bertrand J, Bollmann M. Soluble syndecans: biomarkers for diseases and therapeutic options. Br J Pharmacol. 2019;176:67-81.

Arican O, Aral M, Sasmaz S, et al. Serum levels of TNF-alpha, IFN-gamma, IL-6, IL-8, IL-12, IL-17, and IL-18 in patients with active psoriasis and correlation with disease severity. Mediators Inflamm. 2005;2005:273-279.

Kyriakou A, Patsatsi A, Vyzantiadis TA, et al. Serum levels of TNF-α, IL12/23 p40, and IL-17 in psoriatic patients with and without nail psoriasis: a cross-sectional study. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014;2014:508178.

Xuan ML, Lu CJ, Han L, et al. Circulating levels of inflammatory cytokines in patients with psoriasis vulgaris of different Chinese medicine syndromes. Chin J Integr Med. 2015;21:108-114.

Saunders S, Jalkanen M, O’Farrell S, et al. Molecular cloning of syndecan, an integral membrane proteoglycan. J Cell Biol. 1989;108:1547-1556.

Manon-Jensen T, Itoh Y, Couchman JR. Proteoglycans in health and disease: the multiple roles of syndecan shedding. FEBS J. 2010;277:3876-3889.

Zhao J, Ye X, Zhang Z. Syndecan-4 is correlated with disease activity and serological characteristic of rheumatoid arthritis. Adv Rheumatol. 2022;62:21.

Cekic C, Kırcı A, Vatansever S, et al. Serum syndecan-1 levels and its relationship to disease activity in patients with Crohn’s disease. Gastroenterol Res Pract. 2015;2015:850351.

Minowa K, Amano H, Nakano S, et al. Elevated serum level of circulating syndecan-1 (CD138) in active systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2011;44:357-362.

Nakao M, Sugaya M, Takahashi N, et al. Increased syndecan-4 expression in sera and skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Arch Dermatol Res. 2016;308:655-660.

Jaiswal AK, Sadasivam M, Archer NK, et al. Syndecan-1 regulates psoriasiform dermatitis by controlling homeostasis of IL-17-producing γδ T cells. J Immunol. 2018;201:1651-1661

Wagner MFMG, Theodoro TR, Filho CASM, et al. Extracellular matrix alterations in the skin of patients affected by psoriasis. BMC Mol Cell Biol. 2021;22:55.

Peters F, Rahn S, Mengel M, et al. Syndecan-1 shedding by meprin β impairs keratinocyte adhesion and differentiation in hyperkeratosis. Matrix Biol. 2021;102:37-69.

Koliakou E, Eleni MM, Koumentakou I, et al. Altered distribution and expression of syndecan-1 and -4 as an additional hallmark in psoriasis. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:6511.

Doss RW, El-Rifaie AA, Said AN, et al. Cutaneous syndecan-1 expression before and after phototherapy in psoriasis. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2020;86:439-440.

Pathogenic Significance of Serum Syndecan-1 and Syndecan-4 in Psoriasis

Pathogenic Significance of Serum Syndecan-1 and Syndecan-4 in Psoriasis

PRACTICE POINTS

- Improved understanding of psoriasis pathogenesis has enabled the development of targeted treatments, although the mediators driving the disease have not yet been fully identified.

- Based on the findings of this study and existing literature, we suggest that syndecan-1 and syndecan-4 may play a role in the pathogenesis of psoriasis; however, further studies are needed to elucidate their precise mechanisms of action.