User login

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic disease caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is naturally occurring worldwide but particularly prominent in the Great Lakes, Mississippi, and Ohio River areas of the United States. The disease was first described by Thomas Caspar Gilchrist in 1894 and historically has been referred to as Gilchrist disease, North American blastomycosis, or Chicago disease.1,2 Cutaneous blastomycosis can occur by dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic and pulmonary disease or rarely via direct inoculation of the skin resulting in primary cutaneous disease. Clinically, the lesions are polymorphic and may appear as well-demarcated verrucous plaques containing foci of pustules or ulcerations. Lesions typically heal centrifugally with a cribriform scar.3

We describe an adolescent with a unique history of inoculation 2 weeks prior to the development of a biopsy-confirmed lesion of cutaneous blastomycosis on the left chest wall that clinically resolved following 6 months of itraconazole.

Case Report

A 16-year-old adolescent boy with a history of morbid obesity, asthma, and seasonal allergies presented for evaluation of a painful, slowly enlarging skin lesion on the left chest wall of 2 months’ duration. According to the patient, a “small pimple” appeared at the site of impact 2 weeks following a fall into a muddy flowerbed in Madison, Wisconsin. The patient recalled that although he had soiled his clothing, there was no identifiable puncture of the skin. Despite daily application of hydrogen peroxide and a 1-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, the lesion gradually enlarged. Complete review of systems as well as exposure and travel history were otherwise negative.

Physical examination revealed a 5.0×2.5-cm exophytic, firm, well-circumscribed plaque with a papillated crusted surface on the left side of the chest near the posterior axillary line (Figure 1). There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic workup, including complete blood cell count with differential, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus antibody/antigen testing, interferon-gamma release assay, and chest radiograph were all within normal limits.

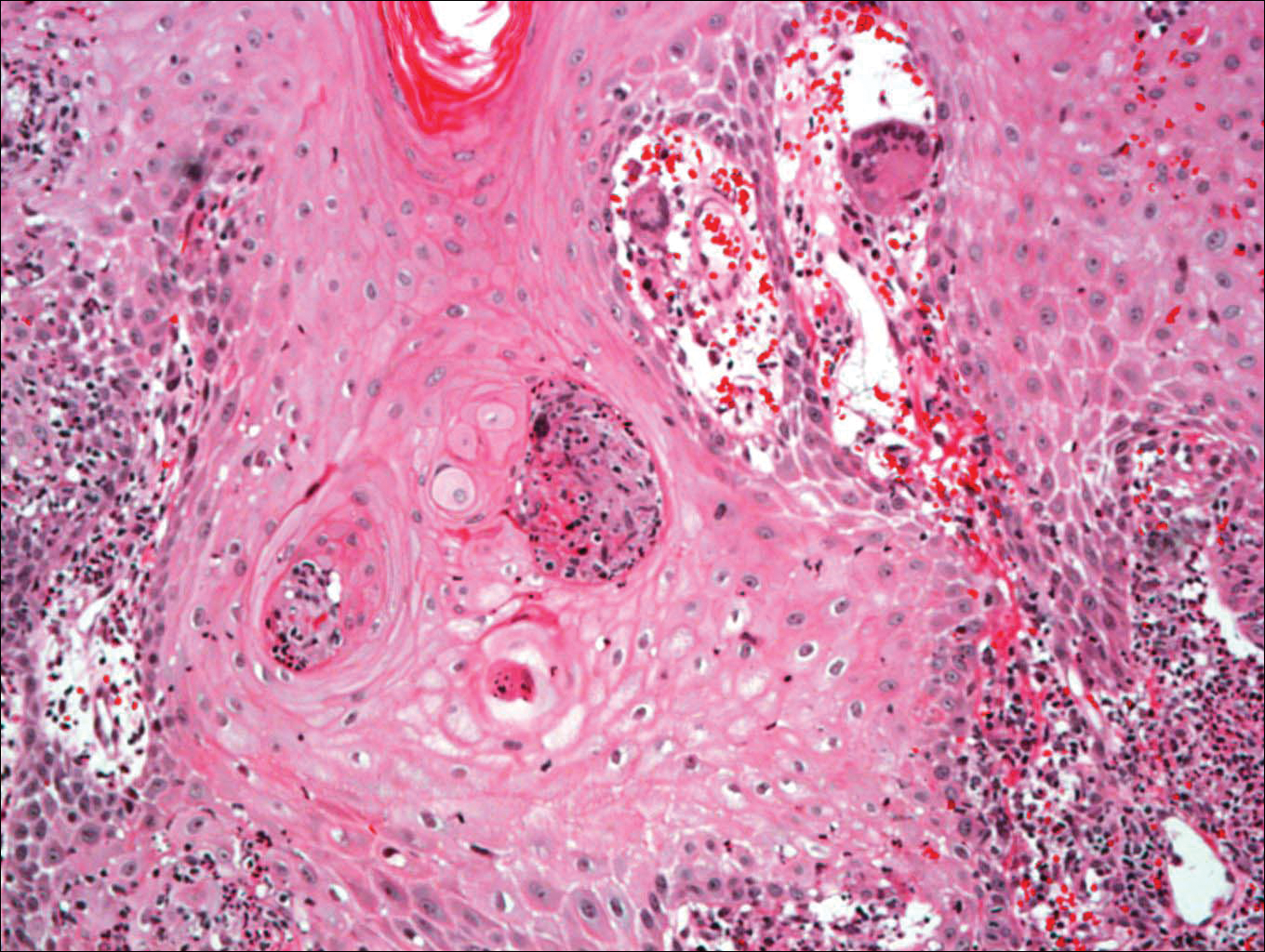

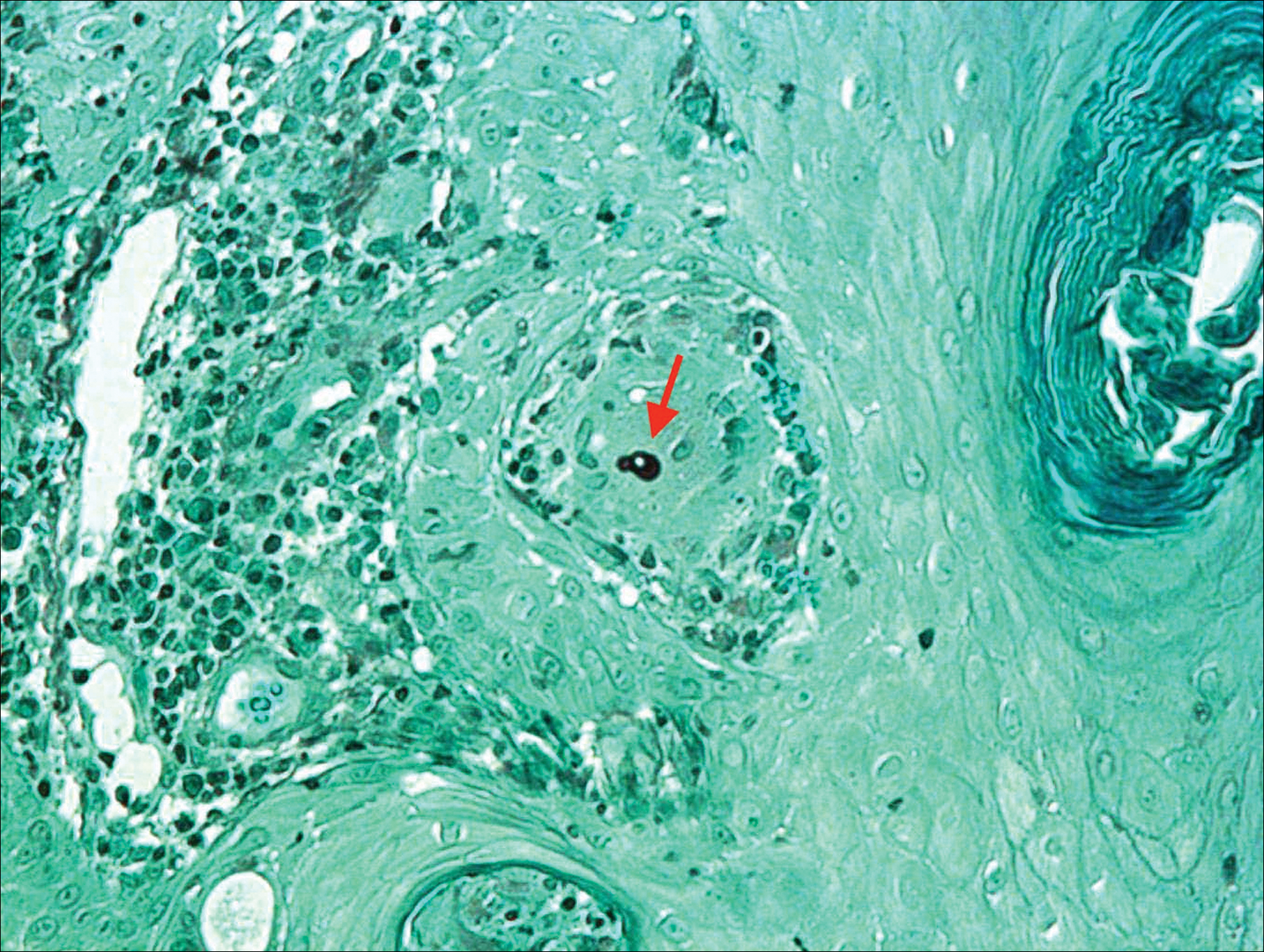

Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with a brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Displayed in Figure 3 is the Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain that highlighted the thick double-contoured wall-budding yeasts.

The patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous blastomycosis. Treatment was initiated with itraconazole 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg 2 times daily for 6 months. Following 3 months of therapy, the lesion had markedly improved with violaceous dyschromia and no residual surface changes. After 5 months of itraconazole, the patient stopped taking the medication for 2 months due to pharmacy issues and then resumed. After 6 total months of therapy, the lesion healed with only residual dyschromia and itraconazole was discontinued.

Comment

Epidemiology

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic pyogranulomatous disease caused by the dimorphic fungus B dermatitidis, naturally occurring in the soil with a worldwide distribution.4 Individuals affected by the disease often reside in locations where the fungus is endemic, specifically in areas that border the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, the Great Lakes, and Canadian provinces near the Saint Lawrence Seaway. More recently there has been an increased incidence of blastomycosis, with the highest proportion found in Wisconsin and Michigan.1,2 Exposures often are associated with recreational and occupational activities near streams or rivers where there may be decaying vegetation.1 Despite the ubiquitous presence of B dermatitidis in regions where the species is endemic, it is likely that many individuals who are exposed to the organism do not develop infection.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis for the development of disease in a particular individual remains unclear. Immunosuppression is not a prerequisite for susceptibility, as evidenced by a review of 123 cases of blastomycosis in which a preceding immunodepressive disorder was present in only 25% of patients. The same study found that it was almost equally common as diabetes mellitus and present in 22% of patients.5 The organism is considered a true pathogen given its ability to affect healthy individuals and the presence of a newly identified novel 120-kD glycoprotein antigen (WI-1) on the cell wall that may confer virulence via extracellular matrix and macrophage binding. Intact cell-mediated immunity that prevents the conversion of conidia (the infectious agent) to yeast (the form that exists at body temperature) plays a key role in conferring natural resistance.6,7

Cutaneous infection may occur by either dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic disease or less commonly via direct inoculation of the skin, resulting in primary cutaneous disease. With respect to systemic disease, infection occurs through inhalation of conidia from moist soil containing organic debris, with an incubation period of 4 to 6 weeks. In the lungs, in a process largely dependent on host cell-mediated immunity, the mold quickly converts to yeast and may then either multiply or be phagocytized.2,6,7 Transmission does not occur from person to person.7 Asymptomatic infection may occur in at least 50% of patients, often leading to a delay in diagnosis. Symptomatic pulmonary disease may range from mild flulike symptoms to overt pneumonia, clinically indistinguishable from community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, other fungal infections, and cancer. Of patients with primary pulmonary disease, 25% to 80% have been reported to develop secondary organ involvement via lymphohematogenous spread most commonly to the skin, followed respectively by the skeletal, genitourinary, and central nervous systems. Currently, there are 54 documented cases of secondary disseminated cutaneous blastomycosis in children reported in the literature.3,8-14

Presentation

Primary cutaneous disease resulting from direct cutaneous inoculation is rare, especially among children.14 Of 28 cases of isolated cutaneous blastomycosis reported in the literature, 12 (42%) were pediatric.3,8-21 Inoculation blastomycosis typically presents as a papule that expands to a well-demarcated verrucous plaque, often up to several centimeters in diameter, and is located on the skin at the site of contact. The lesion may exhibit a myriad of features ranging from pustules or nodules to focal ulcerations, either present centrally or within raised borders that ultimately may communicate via sinus tracking.7 Lesions that are purely pustular in morphology also have been reported. Healing typically begins centrally and expands centrifugally, often with cribriform scarring.2,4,22 Histologic features of primary and secondary blastomycosis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal microabscesses, and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation.4 Classically, broad-based budding yeast are identified with a doubly refractile cell wall that is best visualized on periodic acid–Schiff staining.2

Diagnosis

In approximately 50% of patients with cutaneous blastomycosis resulting from secondary spread, there may be an absence of clinically active pulmonary disease, posing a diagnostic dilemma when differentiating from primary cutaneous disease.1,2,4 Furthermore, the skin findings exhibited in primary and secondary cutaneous blastomycosis cannot be distinguished by clinical inspection.19 To fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of primary cutaneous blastomycosis, there must be an identifiable source of infection from the environment, a lesion at the site of contact, a proven absence of systemic infection, and visualization and/or isolation of fungus from the lesion.4,12 The incubation period of lesions is shorter in primary cutaneous disease (2 weeks) and may aid in its differentiation from secondary disease, which typically is longer with lesions presenting 4 to 6 weeks following initial exposure.4

Treatment

Under the current 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, 6 to 12 months of itraconazole is the treatment recommendation for mild to moderate pulmonary systemic disease without central nervous system involvement.7 Central nervous system disease and moderate to severe pulmonary and systemic disease are treated with intravenous amphotericin B followed by 12 months of oral itraconazole.1,7 Primary cutaneous disease, unlike secondary disease, may self-resolve; however, primary cutaneous disease usually is treated with 6 months of itraconazole, though successful therapy with surgical excision, radiation therapy, and incision and drainage have been reported.19

Unlike secondary cutaneous blastomycosis, primary inoculation disease may be self-limited; however, as treatment with antifungal therapy has become the standard of care, the disease’s propensity to self-resolve has not been well studied.4 Oral itraconazole for 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice for mild to moderate cutaneous disease.1,22 Effective treatment duration may be difficult to definitively assess because of the self-limited nature of the disease. Our patient showed marked improvement after 3 months and resolution of the skin lesion following 6 months of itraconazole therapy. Our findings support the previously documented observation that systemic therapy might potentially be needed only for the time required to eliminate the clinical evidence of cutaneous disease.19 Our patient received the full 6 months of treatment according to current guidelines. Among a review of 22 cases of primary inoculation blastomycosis, the 5 patients who were treated with an azole agent alone showed disease clearance with an average treatment course of 3.2 months, ranging from 1 to 6 months.19 Further studies that assess the time to clearance with antifungal therapy and subsequent recurrence rates may be warranted.

Conclusion

Pediatric primary cutaneous blastomycosis is a rare cutaneous disease. Identifying sources of probable inoculation from the environment for this patient was unique in that the patient fell into a muddy puddle within a flowerbed. Given the patient’s atopic history, a predominance of humoral over cell-mediated immunity may have placed him at risk. He responded well to 6 months of oral itraconazole and there was no ulceration or scar formation. An increased awareness of this infection, particularly in geographic areas where its reported incidence is on the rise, could be helpful in reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenhua Liu, MD (Libertyville, Illinois), for reviewing the pathology and Pravin Muniyappa, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for referring the case.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Smith JA, Riddell Jt, Kauffman CA. Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:440-449.

- Fisher KR, Baselski V, Beard G, et al. Pustular blastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:355-358.

- Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

- Lemos LB, Baliga M, Guo M. Blastomycosis: the great pretender can also be an opportunist. initial clinical diagnosis and underlying diseases in 123 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:194-203.

- Bradsher RW, Chapman SW, Pappas PG. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:21-40, vii.

- Blastomycosis. In: Kimberlin DW, ed. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:263-264.

- Brick KE, Drolet BA, Lyon VB, et al. Cutaneous and disseminated blastomycosis: a pediatric case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:23-28.

- Fanella S, Skinner S, Trepman E, et al. Blastomycosis in children and adolescents: a 30-year experience from Manitoba. Med Mycol. 2011;49:627-632.

- Frost HM, Anderson J, Ivacic L, et al. Blastomycosis in children: an analysis of clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic features. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6:49-56.

- Shukla S, Singh S, Jain M, et al. Paediatric cutaneous blastomycosis: a rare case diagnosed on FNAC. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:119-121.

- Smith RJ, Boos MD, Burnham JM, et al. Atypical cutaneous blastomycosis in a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on infliximab. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1386-E1389.

- Wilson JW, Cawley EP, Weidman FD, et al. Primary cutaneous North American blastomycosis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:39-45.

- Zampogna JC, Hoy MJ, Ramos-Caro FA. Primary cutaneous north american blastomycosis in an immunosuppressed child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:128-130.

- Balasaraswathy P, Theerthanath. Cutaneous blastomycosis presenting as non-healing ulcer and responding to oral ketoconazole. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:19.

- Bonifaz A, Morales D, Morales N, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis. an imported case with good response to itraconazole. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2016;33:51-54.

- Clinton TS, Timko AL. Cutaneous blastomycosis without evidence of pulmonary involvement. Mil Med. 2003;168:651-653.

- Dhamija A, D’Souza P, Salgia P, et al. Blastomycosis presenting as solitary nodule: a rare presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:133-135.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Motswaledi HM, Monyemangene FM, Maloba BR, et al. Blastomycosis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1090-1093.

- Rodríguez-Mena A, Mayorga J, Solís-Ledesma G, et al. Blastomycosis: report of an imported case in Mexico, with only cutaneous lesions [in Spanish]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27:210-212.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic disease caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is naturally occurring worldwide but particularly prominent in the Great Lakes, Mississippi, and Ohio River areas of the United States. The disease was first described by Thomas Caspar Gilchrist in 1894 and historically has been referred to as Gilchrist disease, North American blastomycosis, or Chicago disease.1,2 Cutaneous blastomycosis can occur by dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic and pulmonary disease or rarely via direct inoculation of the skin resulting in primary cutaneous disease. Clinically, the lesions are polymorphic and may appear as well-demarcated verrucous plaques containing foci of pustules or ulcerations. Lesions typically heal centrifugally with a cribriform scar.3

We describe an adolescent with a unique history of inoculation 2 weeks prior to the development of a biopsy-confirmed lesion of cutaneous blastomycosis on the left chest wall that clinically resolved following 6 months of itraconazole.

Case Report

A 16-year-old adolescent boy with a history of morbid obesity, asthma, and seasonal allergies presented for evaluation of a painful, slowly enlarging skin lesion on the left chest wall of 2 months’ duration. According to the patient, a “small pimple” appeared at the site of impact 2 weeks following a fall into a muddy flowerbed in Madison, Wisconsin. The patient recalled that although he had soiled his clothing, there was no identifiable puncture of the skin. Despite daily application of hydrogen peroxide and a 1-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, the lesion gradually enlarged. Complete review of systems as well as exposure and travel history were otherwise negative.

Physical examination revealed a 5.0×2.5-cm exophytic, firm, well-circumscribed plaque with a papillated crusted surface on the left side of the chest near the posterior axillary line (Figure 1). There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic workup, including complete blood cell count with differential, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus antibody/antigen testing, interferon-gamma release assay, and chest radiograph were all within normal limits.

Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with a brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Displayed in Figure 3 is the Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain that highlighted the thick double-contoured wall-budding yeasts.

The patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous blastomycosis. Treatment was initiated with itraconazole 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg 2 times daily for 6 months. Following 3 months of therapy, the lesion had markedly improved with violaceous dyschromia and no residual surface changes. After 5 months of itraconazole, the patient stopped taking the medication for 2 months due to pharmacy issues and then resumed. After 6 total months of therapy, the lesion healed with only residual dyschromia and itraconazole was discontinued.

Comment

Epidemiology

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic pyogranulomatous disease caused by the dimorphic fungus B dermatitidis, naturally occurring in the soil with a worldwide distribution.4 Individuals affected by the disease often reside in locations where the fungus is endemic, specifically in areas that border the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, the Great Lakes, and Canadian provinces near the Saint Lawrence Seaway. More recently there has been an increased incidence of blastomycosis, with the highest proportion found in Wisconsin and Michigan.1,2 Exposures often are associated with recreational and occupational activities near streams or rivers where there may be decaying vegetation.1 Despite the ubiquitous presence of B dermatitidis in regions where the species is endemic, it is likely that many individuals who are exposed to the organism do not develop infection.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis for the development of disease in a particular individual remains unclear. Immunosuppression is not a prerequisite for susceptibility, as evidenced by a review of 123 cases of blastomycosis in which a preceding immunodepressive disorder was present in only 25% of patients. The same study found that it was almost equally common as diabetes mellitus and present in 22% of patients.5 The organism is considered a true pathogen given its ability to affect healthy individuals and the presence of a newly identified novel 120-kD glycoprotein antigen (WI-1) on the cell wall that may confer virulence via extracellular matrix and macrophage binding. Intact cell-mediated immunity that prevents the conversion of conidia (the infectious agent) to yeast (the form that exists at body temperature) plays a key role in conferring natural resistance.6,7

Cutaneous infection may occur by either dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic disease or less commonly via direct inoculation of the skin, resulting in primary cutaneous disease. With respect to systemic disease, infection occurs through inhalation of conidia from moist soil containing organic debris, with an incubation period of 4 to 6 weeks. In the lungs, in a process largely dependent on host cell-mediated immunity, the mold quickly converts to yeast and may then either multiply or be phagocytized.2,6,7 Transmission does not occur from person to person.7 Asymptomatic infection may occur in at least 50% of patients, often leading to a delay in diagnosis. Symptomatic pulmonary disease may range from mild flulike symptoms to overt pneumonia, clinically indistinguishable from community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, other fungal infections, and cancer. Of patients with primary pulmonary disease, 25% to 80% have been reported to develop secondary organ involvement via lymphohematogenous spread most commonly to the skin, followed respectively by the skeletal, genitourinary, and central nervous systems. Currently, there are 54 documented cases of secondary disseminated cutaneous blastomycosis in children reported in the literature.3,8-14

Presentation

Primary cutaneous disease resulting from direct cutaneous inoculation is rare, especially among children.14 Of 28 cases of isolated cutaneous blastomycosis reported in the literature, 12 (42%) were pediatric.3,8-21 Inoculation blastomycosis typically presents as a papule that expands to a well-demarcated verrucous plaque, often up to several centimeters in diameter, and is located on the skin at the site of contact. The lesion may exhibit a myriad of features ranging from pustules or nodules to focal ulcerations, either present centrally or within raised borders that ultimately may communicate via sinus tracking.7 Lesions that are purely pustular in morphology also have been reported. Healing typically begins centrally and expands centrifugally, often with cribriform scarring.2,4,22 Histologic features of primary and secondary blastomycosis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal microabscesses, and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation.4 Classically, broad-based budding yeast are identified with a doubly refractile cell wall that is best visualized on periodic acid–Schiff staining.2

Diagnosis

In approximately 50% of patients with cutaneous blastomycosis resulting from secondary spread, there may be an absence of clinically active pulmonary disease, posing a diagnostic dilemma when differentiating from primary cutaneous disease.1,2,4 Furthermore, the skin findings exhibited in primary and secondary cutaneous blastomycosis cannot be distinguished by clinical inspection.19 To fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of primary cutaneous blastomycosis, there must be an identifiable source of infection from the environment, a lesion at the site of contact, a proven absence of systemic infection, and visualization and/or isolation of fungus from the lesion.4,12 The incubation period of lesions is shorter in primary cutaneous disease (2 weeks) and may aid in its differentiation from secondary disease, which typically is longer with lesions presenting 4 to 6 weeks following initial exposure.4

Treatment

Under the current 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, 6 to 12 months of itraconazole is the treatment recommendation for mild to moderate pulmonary systemic disease without central nervous system involvement.7 Central nervous system disease and moderate to severe pulmonary and systemic disease are treated with intravenous amphotericin B followed by 12 months of oral itraconazole.1,7 Primary cutaneous disease, unlike secondary disease, may self-resolve; however, primary cutaneous disease usually is treated with 6 months of itraconazole, though successful therapy with surgical excision, radiation therapy, and incision and drainage have been reported.19

Unlike secondary cutaneous blastomycosis, primary inoculation disease may be self-limited; however, as treatment with antifungal therapy has become the standard of care, the disease’s propensity to self-resolve has not been well studied.4 Oral itraconazole for 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice for mild to moderate cutaneous disease.1,22 Effective treatment duration may be difficult to definitively assess because of the self-limited nature of the disease. Our patient showed marked improvement after 3 months and resolution of the skin lesion following 6 months of itraconazole therapy. Our findings support the previously documented observation that systemic therapy might potentially be needed only for the time required to eliminate the clinical evidence of cutaneous disease.19 Our patient received the full 6 months of treatment according to current guidelines. Among a review of 22 cases of primary inoculation blastomycosis, the 5 patients who were treated with an azole agent alone showed disease clearance with an average treatment course of 3.2 months, ranging from 1 to 6 months.19 Further studies that assess the time to clearance with antifungal therapy and subsequent recurrence rates may be warranted.

Conclusion

Pediatric primary cutaneous blastomycosis is a rare cutaneous disease. Identifying sources of probable inoculation from the environment for this patient was unique in that the patient fell into a muddy puddle within a flowerbed. Given the patient’s atopic history, a predominance of humoral over cell-mediated immunity may have placed him at risk. He responded well to 6 months of oral itraconazole and there was no ulceration or scar formation. An increased awareness of this infection, particularly in geographic areas where its reported incidence is on the rise, could be helpful in reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenhua Liu, MD (Libertyville, Illinois), for reviewing the pathology and Pravin Muniyappa, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for referring the case.

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic disease caused by the thermally dimorphic fungus Blastomyces dermatitidis, which is naturally occurring worldwide but particularly prominent in the Great Lakes, Mississippi, and Ohio River areas of the United States. The disease was first described by Thomas Caspar Gilchrist in 1894 and historically has been referred to as Gilchrist disease, North American blastomycosis, or Chicago disease.1,2 Cutaneous blastomycosis can occur by dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic and pulmonary disease or rarely via direct inoculation of the skin resulting in primary cutaneous disease. Clinically, the lesions are polymorphic and may appear as well-demarcated verrucous plaques containing foci of pustules or ulcerations. Lesions typically heal centrifugally with a cribriform scar.3

We describe an adolescent with a unique history of inoculation 2 weeks prior to the development of a biopsy-confirmed lesion of cutaneous blastomycosis on the left chest wall that clinically resolved following 6 months of itraconazole.

Case Report

A 16-year-old adolescent boy with a history of morbid obesity, asthma, and seasonal allergies presented for evaluation of a painful, slowly enlarging skin lesion on the left chest wall of 2 months’ duration. According to the patient, a “small pimple” appeared at the site of impact 2 weeks following a fall into a muddy flowerbed in Madison, Wisconsin. The patient recalled that although he had soiled his clothing, there was no identifiable puncture of the skin. Despite daily application of hydrogen peroxide and a 1-week course of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, the lesion gradually enlarged. Complete review of systems as well as exposure and travel history were otherwise negative.

Physical examination revealed a 5.0×2.5-cm exophytic, firm, well-circumscribed plaque with a papillated crusted surface on the left side of the chest near the posterior axillary line (Figure 1). There was no palpable regional lymphadenopathy. Pulmonary examination was unremarkable. Diagnostic workup, including complete blood cell count with differential, hemoglobin A1c, human immunodeficiency virus antibody/antigen testing, interferon-gamma release assay, and chest radiograph were all within normal limits.

Histologic examination of a biopsy specimen showed pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the epidermis with a brisk mixed inflammatory infiltrate (Figure 2). Displayed in Figure 3 is the Grocott-Gomori methenamine-silver stain that highlighted the thick double-contoured wall-budding yeasts.

The patient was diagnosed with primary cutaneous blastomycosis. Treatment was initiated with itraconazole 200 mg 3 times daily for 3 days, followed by 200 mg 2 times daily for 6 months. Following 3 months of therapy, the lesion had markedly improved with violaceous dyschromia and no residual surface changes. After 5 months of itraconazole, the patient stopped taking the medication for 2 months due to pharmacy issues and then resumed. After 6 total months of therapy, the lesion healed with only residual dyschromia and itraconazole was discontinued.

Comment

Epidemiology

Blastomycosis is a polymorphic pyogranulomatous disease caused by the dimorphic fungus B dermatitidis, naturally occurring in the soil with a worldwide distribution.4 Individuals affected by the disease often reside in locations where the fungus is endemic, specifically in areas that border the Mississippi and Ohio rivers, the Great Lakes, and Canadian provinces near the Saint Lawrence Seaway. More recently there has been an increased incidence of blastomycosis, with the highest proportion found in Wisconsin and Michigan.1,2 Exposures often are associated with recreational and occupational activities near streams or rivers where there may be decaying vegetation.1 Despite the ubiquitous presence of B dermatitidis in regions where the species is endemic, it is likely that many individuals who are exposed to the organism do not develop infection.

Pathogenesis

The exact pathogenesis for the development of disease in a particular individual remains unclear. Immunosuppression is not a prerequisite for susceptibility, as evidenced by a review of 123 cases of blastomycosis in which a preceding immunodepressive disorder was present in only 25% of patients. The same study found that it was almost equally common as diabetes mellitus and present in 22% of patients.5 The organism is considered a true pathogen given its ability to affect healthy individuals and the presence of a newly identified novel 120-kD glycoprotein antigen (WI-1) on the cell wall that may confer virulence via extracellular matrix and macrophage binding. Intact cell-mediated immunity that prevents the conversion of conidia (the infectious agent) to yeast (the form that exists at body temperature) plays a key role in conferring natural resistance.6,7

Cutaneous infection may occur by either dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic disease or less commonly via direct inoculation of the skin, resulting in primary cutaneous disease. With respect to systemic disease, infection occurs through inhalation of conidia from moist soil containing organic debris, with an incubation period of 4 to 6 weeks. In the lungs, in a process largely dependent on host cell-mediated immunity, the mold quickly converts to yeast and may then either multiply or be phagocytized.2,6,7 Transmission does not occur from person to person.7 Asymptomatic infection may occur in at least 50% of patients, often leading to a delay in diagnosis. Symptomatic pulmonary disease may range from mild flulike symptoms to overt pneumonia, clinically indistinguishable from community-acquired bacterial pneumonia, tuberculosis, other fungal infections, and cancer. Of patients with primary pulmonary disease, 25% to 80% have been reported to develop secondary organ involvement via lymphohematogenous spread most commonly to the skin, followed respectively by the skeletal, genitourinary, and central nervous systems. Currently, there are 54 documented cases of secondary disseminated cutaneous blastomycosis in children reported in the literature.3,8-14

Presentation

Primary cutaneous disease resulting from direct cutaneous inoculation is rare, especially among children.14 Of 28 cases of isolated cutaneous blastomycosis reported in the literature, 12 (42%) were pediatric.3,8-21 Inoculation blastomycosis typically presents as a papule that expands to a well-demarcated verrucous plaque, often up to several centimeters in diameter, and is located on the skin at the site of contact. The lesion may exhibit a myriad of features ranging from pustules or nodules to focal ulcerations, either present centrally or within raised borders that ultimately may communicate via sinus tracking.7 Lesions that are purely pustular in morphology also have been reported. Healing typically begins centrally and expands centrifugally, often with cribriform scarring.2,4,22 Histologic features of primary and secondary blastomycosis include pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, intraepidermal microabscesses, and dermal suppurative granulomatous inflammation.4 Classically, broad-based budding yeast are identified with a doubly refractile cell wall that is best visualized on periodic acid–Schiff staining.2

Diagnosis

In approximately 50% of patients with cutaneous blastomycosis resulting from secondary spread, there may be an absence of clinically active pulmonary disease, posing a diagnostic dilemma when differentiating from primary cutaneous disease.1,2,4 Furthermore, the skin findings exhibited in primary and secondary cutaneous blastomycosis cannot be distinguished by clinical inspection.19 To fulfill the criteria for diagnosis of primary cutaneous blastomycosis, there must be an identifiable source of infection from the environment, a lesion at the site of contact, a proven absence of systemic infection, and visualization and/or isolation of fungus from the lesion.4,12 The incubation period of lesions is shorter in primary cutaneous disease (2 weeks) and may aid in its differentiation from secondary disease, which typically is longer with lesions presenting 4 to 6 weeks following initial exposure.4

Treatment

Under the current 2015 guidelines from the American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Infectious Diseases, 6 to 12 months of itraconazole is the treatment recommendation for mild to moderate pulmonary systemic disease without central nervous system involvement.7 Central nervous system disease and moderate to severe pulmonary and systemic disease are treated with intravenous amphotericin B followed by 12 months of oral itraconazole.1,7 Primary cutaneous disease, unlike secondary disease, may self-resolve; however, primary cutaneous disease usually is treated with 6 months of itraconazole, though successful therapy with surgical excision, radiation therapy, and incision and drainage have been reported.19

Unlike secondary cutaneous blastomycosis, primary inoculation disease may be self-limited; however, as treatment with antifungal therapy has become the standard of care, the disease’s propensity to self-resolve has not been well studied.4 Oral itraconazole for 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice for mild to moderate cutaneous disease.1,22 Effective treatment duration may be difficult to definitively assess because of the self-limited nature of the disease. Our patient showed marked improvement after 3 months and resolution of the skin lesion following 6 months of itraconazole therapy. Our findings support the previously documented observation that systemic therapy might potentially be needed only for the time required to eliminate the clinical evidence of cutaneous disease.19 Our patient received the full 6 months of treatment according to current guidelines. Among a review of 22 cases of primary inoculation blastomycosis, the 5 patients who were treated with an azole agent alone showed disease clearance with an average treatment course of 3.2 months, ranging from 1 to 6 months.19 Further studies that assess the time to clearance with antifungal therapy and subsequent recurrence rates may be warranted.

Conclusion

Pediatric primary cutaneous blastomycosis is a rare cutaneous disease. Identifying sources of probable inoculation from the environment for this patient was unique in that the patient fell into a muddy puddle within a flowerbed. Given the patient’s atopic history, a predominance of humoral over cell-mediated immunity may have placed him at risk. He responded well to 6 months of oral itraconazole and there was no ulceration or scar formation. An increased awareness of this infection, particularly in geographic areas where its reported incidence is on the rise, could be helpful in reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment.

Acknowledgments

We thank Wenhua Liu, MD (Libertyville, Illinois), for reviewing the pathology and Pravin Muniyappa, MD (Chicago, Illinois), for referring the case.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Smith JA, Riddell Jt, Kauffman CA. Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:440-449.

- Fisher KR, Baselski V, Beard G, et al. Pustular blastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:355-358.

- Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

- Lemos LB, Baliga M, Guo M. Blastomycosis: the great pretender can also be an opportunist. initial clinical diagnosis and underlying diseases in 123 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:194-203.

- Bradsher RW, Chapman SW, Pappas PG. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:21-40, vii.

- Blastomycosis. In: Kimberlin DW, ed. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:263-264.

- Brick KE, Drolet BA, Lyon VB, et al. Cutaneous and disseminated blastomycosis: a pediatric case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:23-28.

- Fanella S, Skinner S, Trepman E, et al. Blastomycosis in children and adolescents: a 30-year experience from Manitoba. Med Mycol. 2011;49:627-632.

- Frost HM, Anderson J, Ivacic L, et al. Blastomycosis in children: an analysis of clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic features. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6:49-56.

- Shukla S, Singh S, Jain M, et al. Paediatric cutaneous blastomycosis: a rare case diagnosed on FNAC. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:119-121.

- Smith RJ, Boos MD, Burnham JM, et al. Atypical cutaneous blastomycosis in a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on infliximab. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1386-E1389.

- Wilson JW, Cawley EP, Weidman FD, et al. Primary cutaneous North American blastomycosis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:39-45.

- Zampogna JC, Hoy MJ, Ramos-Caro FA. Primary cutaneous north american blastomycosis in an immunosuppressed child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:128-130.

- Balasaraswathy P, Theerthanath. Cutaneous blastomycosis presenting as non-healing ulcer and responding to oral ketoconazole. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:19.

- Bonifaz A, Morales D, Morales N, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis. an imported case with good response to itraconazole. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2016;33:51-54.

- Clinton TS, Timko AL. Cutaneous blastomycosis without evidence of pulmonary involvement. Mil Med. 2003;168:651-653.

- Dhamija A, D’Souza P, Salgia P, et al. Blastomycosis presenting as solitary nodule: a rare presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:133-135.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Motswaledi HM, Monyemangene FM, Maloba BR, et al. Blastomycosis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1090-1093.

- Rodríguez-Mena A, Mayorga J, Solís-Ledesma G, et al. Blastomycosis: report of an imported case in Mexico, with only cutaneous lesions [in Spanish]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27:210-212.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

- Chapman SW, Dismukes WE, Proia LA, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for the management of blastomycosis: 2008 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2008;46:1801-1812.

- Smith JA, Riddell Jt, Kauffman CA. Cutaneous manifestations of endemic mycoses. Curr Infect Dis Rep. 2013;15:440-449.

- Fisher KR, Baselski V, Beard G, et al. Pustular blastomycosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;6:355-358.

- Mason AR, Cortes GY, Cook J, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a diagnostic challenge. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:824-830.

- Lemos LB, Baliga M, Guo M. Blastomycosis: the great pretender can also be an opportunist. initial clinical diagnosis and underlying diseases in 123 patients. Ann Diagn Pathol. 2002;6:194-203.

- Bradsher RW, Chapman SW, Pappas PG. Blastomycosis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2003;17:21-40, vii.

- Blastomycosis. In: Kimberlin DW, ed. Red Book: 2015 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 30th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2015:263-264.

- Brick KE, Drolet BA, Lyon VB, et al. Cutaneous and disseminated blastomycosis: a pediatric case series. Pediatr Dermatol. 2013;30:23-28.

- Fanella S, Skinner S, Trepman E, et al. Blastomycosis in children and adolescents: a 30-year experience from Manitoba. Med Mycol. 2011;49:627-632.

- Frost HM, Anderson J, Ivacic L, et al. Blastomycosis in children: an analysis of clinical, epidemiologic, and genetic features. J Pediatr Infect Dis Soc. 2017;6:49-56.

- Shukla S, Singh S, Jain M, et al. Paediatric cutaneous blastomycosis: a rare case diagnosed on FNAC. Diagn Cytopathol. 2009;37:119-121.

- Smith RJ, Boos MD, Burnham JM, et al. Atypical cutaneous blastomycosis in a child with juvenile idiopathic arthritis on infliximab. Pediatrics. 2015;136:E1386-E1389.

- Wilson JW, Cawley EP, Weidman FD, et al. Primary cutaneous North American blastomycosis. AMA Arch Derm. 1955;71:39-45.

- Zampogna JC, Hoy MJ, Ramos-Caro FA. Primary cutaneous north american blastomycosis in an immunosuppressed child. Pediatr Dermatol. 2003;20:128-130.

- Balasaraswathy P, Theerthanath. Cutaneous blastomycosis presenting as non-healing ulcer and responding to oral ketoconazole. Dermatol Online J. 2003;9:19.

- Bonifaz A, Morales D, Morales N, et al. Cutaneous blastomycosis. an imported case with good response to itraconazole. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2016;33:51-54.

- Clinton TS, Timko AL. Cutaneous blastomycosis without evidence of pulmonary involvement. Mil Med. 2003;168:651-653.

- Dhamija A, D’Souza P, Salgia P, et al. Blastomycosis presenting as solitary nodule: a rare presentation. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:133-135.

- Gray NA, Baddour LM. Cutaneous inoculation blastomycosis. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:E44-E49.

- Motswaledi HM, Monyemangene FM, Maloba BR, et al. Blastomycosis: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:1090-1093.

- Rodríguez-Mena A, Mayorga J, Solís-Ledesma G, et al. Blastomycosis: report of an imported case in Mexico, with only cutaneous lesions [in Spanish]. Rev Iberoam Micol. 2010;27:210-212.

- Saccente M, Woods GL. Clinical and laboratory update on blastomycosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2010;23:367-381.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous blastomycosis can occur by dissemination of yeast to the skin from systemic and pulmonary disease or rarely via direct inoculation of the skin, resulting in primary cutaneous disease.

- Exposures often are associated with recreational and occupational activities near streams or rivers where there may be decaying vegetation.

- Oral itraconazole for 6 to 12 months is the treatment of choice for mild to moderate cutaneous disease.

- Increased awareness of this rare infection, particularly in geographic areas where its reported incidence is on the rise, could be helpful in reducing delays in diagnosis and treatment.