User login

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

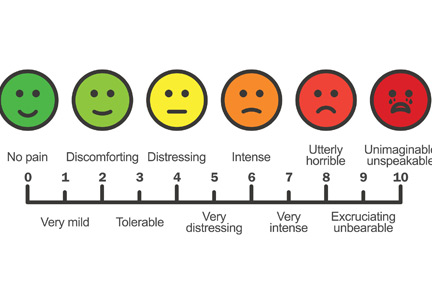

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

Several months ago, we invited readers to submit short personalized commentaries on articles that changed the way they approach a specific clinical problem and the way they take care of patients. In this issue of the Journal, addiction specialist Charles Reznikoff, MD, discusses 3 observational studies that focused on how prescribing opioids for acute pain can lead to chronic opioid use and addiction, and how these studies have influenced his practice.

Although observational studies rank lower on the level-of-evidence scale than randomized controlled trials, they can intellectually stimulate and inform us in ways that lead us to modify how we deliver clinical care.

The initial prescribing of pain medications and the management of patients with chronic pain are currently under intense scrutiny, and are the topic of much discussion in the United States. The opioid epidemic has spilled over into all aspects of daily life, far beyond the medical community. But since we physicians are the only legal and regulated source of narcotics and other pain medications, we are under the microscope—and rightly so.

We, our patients, the pharmaceutical industry, legislators, and the law enforcement community struggle to navigate a complex maze, one with moving walls. Not long ago, physicians were told that we were not attentive enough to our patients’ suffering and needed to do better at relieving it. “Pain” became a vital sign and a recorded metric of quality care. Some excellent changes evolved from this focus, such as increased emphasis on postoperative regional and local pain control. But pain measurements continue to be recorded at every outpatient visit, an almost mindless requirement.

Recently, a patient with lupus nephritis whom I was seeing for blood pressure management reported a pain level of 8 on a scale of 10. I confess that I usually don’t even look at these metrics, but for whatever reason I saw her answer. I asked her about it. She had burned her finger while cooking and said, “I had no idea what number to pick. I picked 8. It’s no big deal.”

But the ongoing emphasis on this metric may lead some patients to expect total pain relief, a problematic expectation in those with chronic pain syndromes such as fibromyalgia. As Dr. Reznikoff points out, a large proportion of patients report they have chronic pain, and many (but clearly not all) suffer from recognized or masked chronic anxiety and depression disorders1 that may well influence how they use pain medications.

Thus, while physicians indeed are on the front lines of offering initial prescriptions for pain medications, we remain betwixt and between in the challenges of responding to the immediate needs of our patients while trying to predict the long-term effects of our prescription on the individual patient and of our prescribing patterns on society in general.

I again welcome your submissions describing how individual publications have affected your personal approach to managing patients and specific diseases. We will publish selected contributions in print and online.

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005

- Tsang A, Von Korff M, Lee S, et al. Common chronic pain conditions in developed and developing countries: gender and age differences and comorbidity with depression-anxiety disorders. J Pain 2008; 9(10):883–891. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.05.005