User login

Bipolar disorder is a prevalent disorder in the primary care setting.1,2 Primary care providers therefore commonly encounter bipolar depression (BD; a major depressive episode in the context of bipolar disorder), which might be (1) an emerging depressive episode in previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder or (2) a recurrent episode during the course of chronic bipolar illness.3,4

A primary care–based collaborative model has been identified as a potential strategy for effective management of chronic mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder.5,6 However, this collaborative treatment model isn’t widely available; many patients with bipolar disorder are, in fact, treated solely by their primary care provider.

Two years ago in this journal,7 we addressed how to precisely identify an episode of BD and differentiate it from major depressive disorder (MDD; also known as unipolar depression). In this review, in addition to advancing clinical knowledge of BD, we provide:

- an overview of treatment options for BD (in contrast to the treatment of unipolar depression)

- the pharmacotherapeutic know-how to initiate and maintain treatment for uncomplicated episodes of BD.

We do not discuss management of manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes of bipolar disorder.

How to identify bipolar depression

Understanding the (sometimes) unclear distinction between bipolar I and bipolar II disorders in an individual patient is key to formulating a therapeutic regimen for BD.

Bipolar I disorder consists of manic episodes, alternating (more often than not) with depressive episodes. Bipolar I usually manifests first with a depressive episode.

Bipolar II disorder manifests with depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes (but never manic episodes).

Continue to: Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders

Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders. Bipolar depression can be seen in the settings of both bipolar I and II disorders. When a patient presents with a manic episode, a history of depressive episodes is common (although not essential) to diagnose bipolar I; alternatively, a history of hypomania (but no prior mania) and depression is needed to make the diagnosis of bipolar II. The natural history of the bipolar disorders is therefore alternating manic and almost always depressive episodes (bipolar I) and alternating hypomanic and always depressive episodes (bipolar II).8

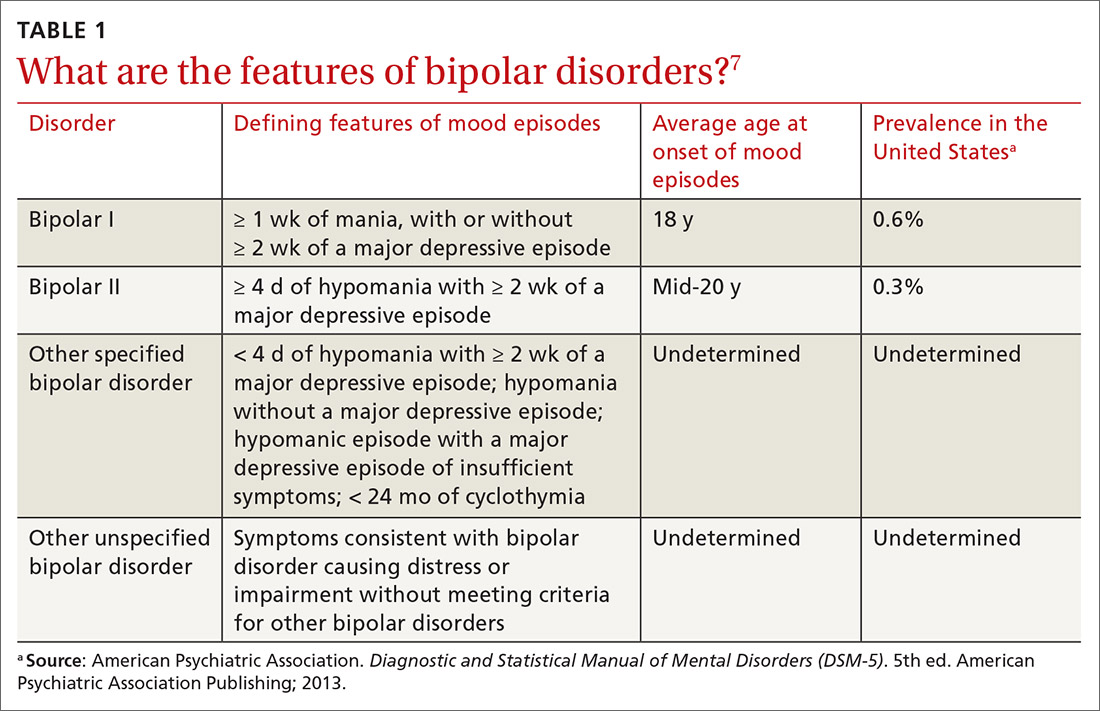

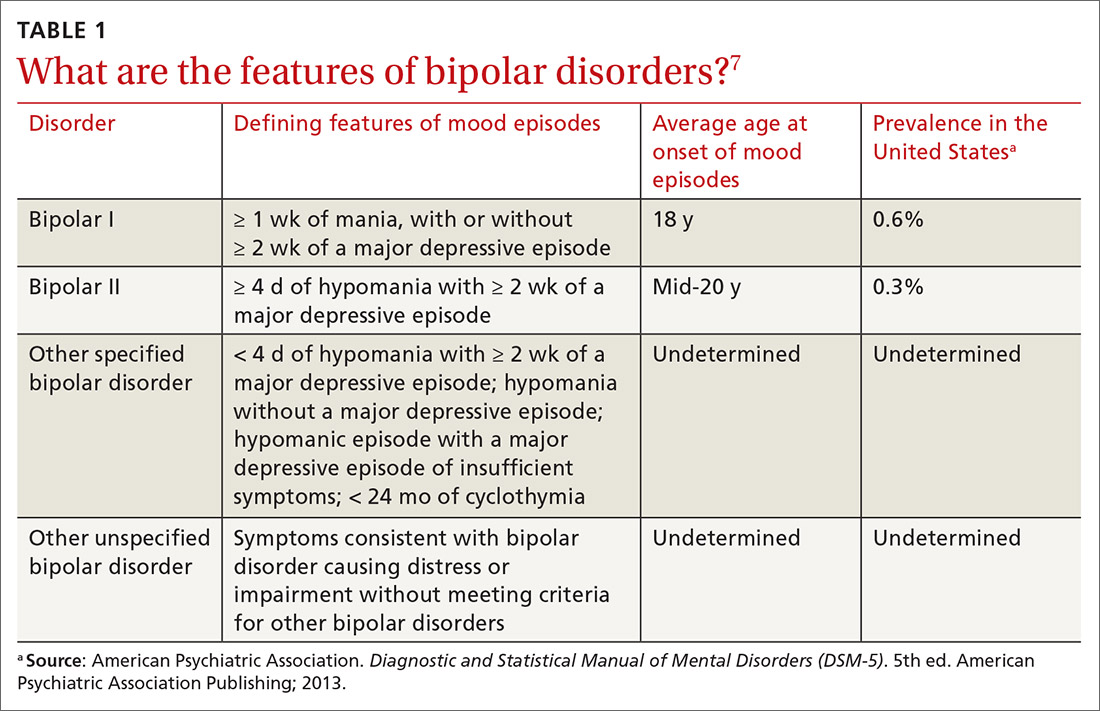

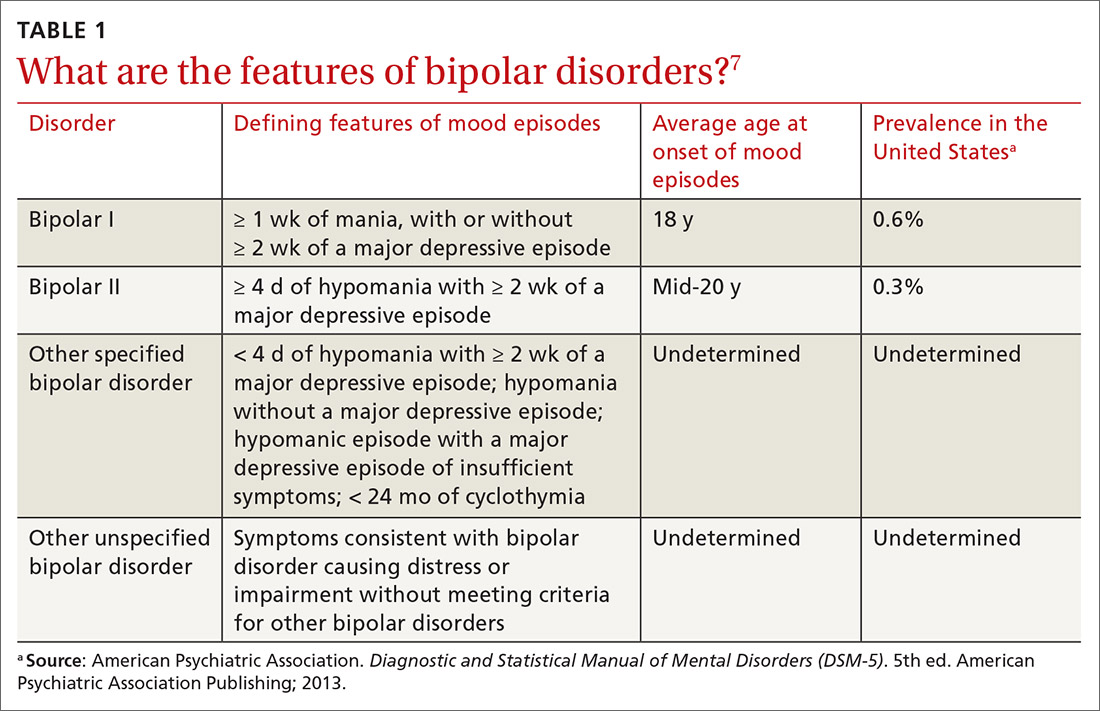

Symptoms of hypomanic episodes are similar to what are seen in manic episodes, but are of shorter duration (≥ 4 days [episodes of mania are at least of 1 week’s duration]), lower intensity (no psychotic symptoms), and not associated with significant functional impairment or hospitalization. Table 17 further describes the differentiating features of bipolar I and bipolar II. A history of an unequivocal manic or hypomanic episode makes the diagnosis of BD relatively easy. However, an unclear history of manic or hypomanic symptoms or episodes frequently leads to misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of BD.

In both bipolar I and II, it is depressive symptoms and episodes that place the greatest burden on patients across the lifespan: They are the most commonly experienced features of the bipolar disorders9,10 and lead to significant distress and functional impairment11; in fact, patients with bipolar disorder spend 3 (or more) times as long in depressive episodes as in manic or hypomanic episodes.12,13 In addition, subthreshold depressive symptoms occur commonly between major mood episodes.

Failure to identify and adequately treat depressive episodes of the bipolar disorders can have serious consequences: Patients are at risk of a worsening course of illness, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, chronic disability, mixed states, rapid cycling of mood episodes, and suicide.

Guidelines for treating bipolar depression

Despite the similarity in presenting symptoms and signs of depressive episodes in bipolar disorders and MDD, treating episodes of BD is significantly different than treating MDD. Antidepressant monotherapy, a mainstay of treatment for MDD, has limited utility in BD (especially depressive episodes of bipolar I) because of its limited efficacy and potential to destabilize mood, lead to rapid cycling, and induce mania or hypomania. Treatment options for BD include pharmacotherapy (the primary modality), psychological intervention (a useful adjunct, described later), and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT; highly worth considering in severe or treatment-resistant cases).

Continue to: For this article...

For this article, we searched PubMed and Google Scholar for guidelines for the management of bipolar disorders in adults that were published between July 2013 (when the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved lurasidone for the treatment of BD) and March 2019. Related guideline-referenced articles and clinical trials were also reviewed.

Our search identified 6 guidelines issued during the search period, developed by the:

- Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD),14

- British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP),15

- Japanese Society of Mood Disorders (JSMD),16

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),17

- International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP),18 and

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.19

How to manage an episode of bipolar depression

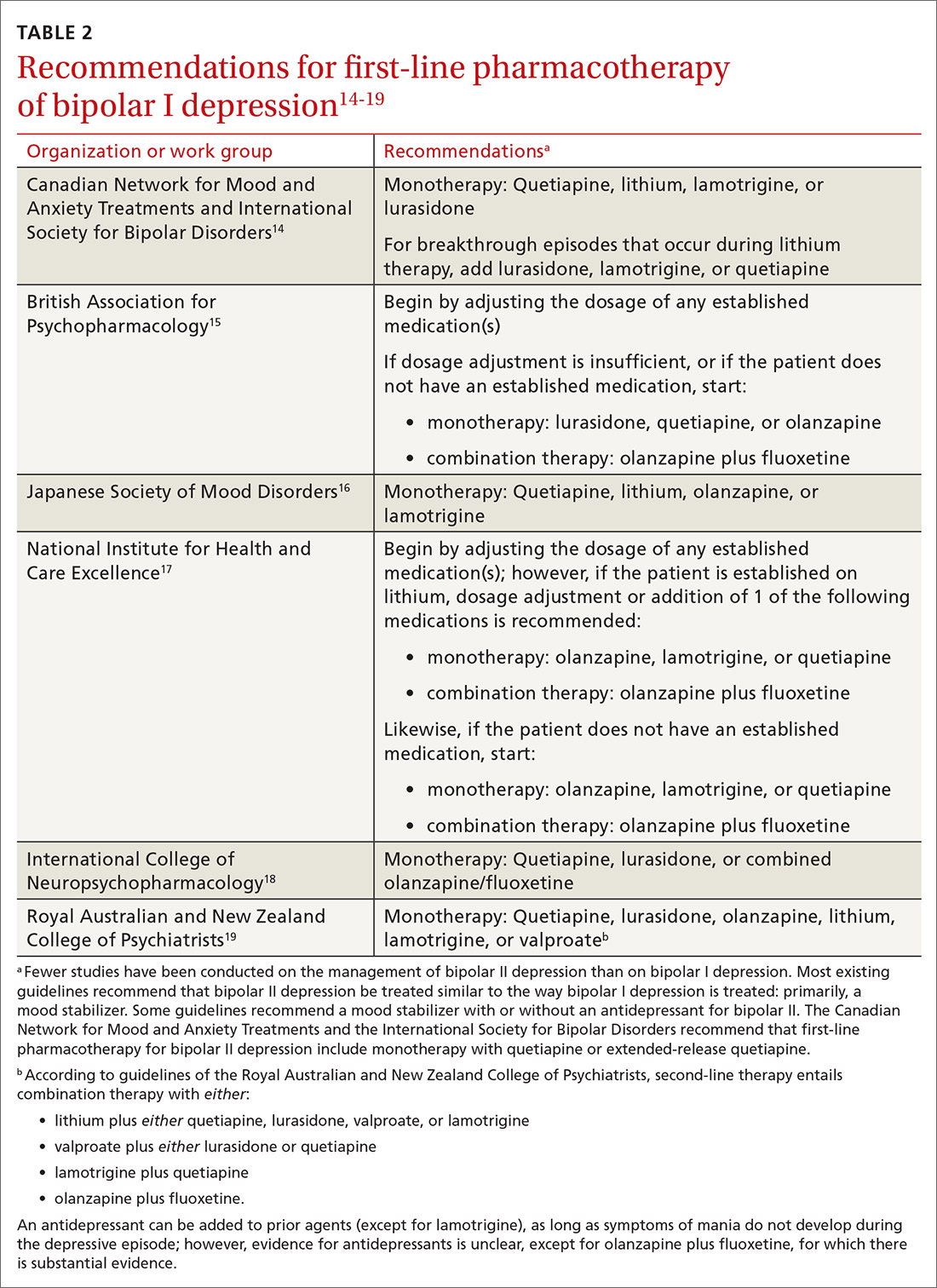

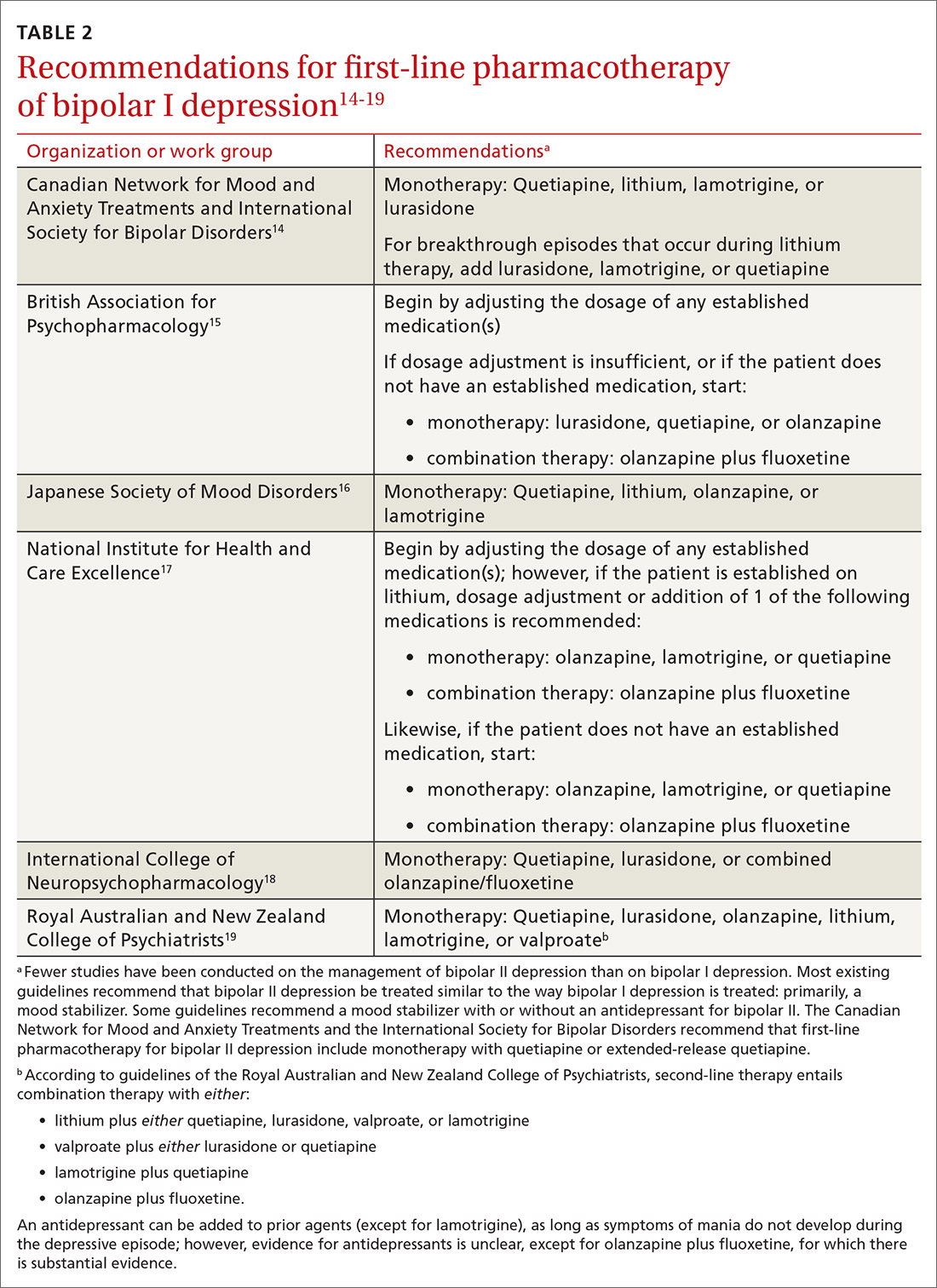

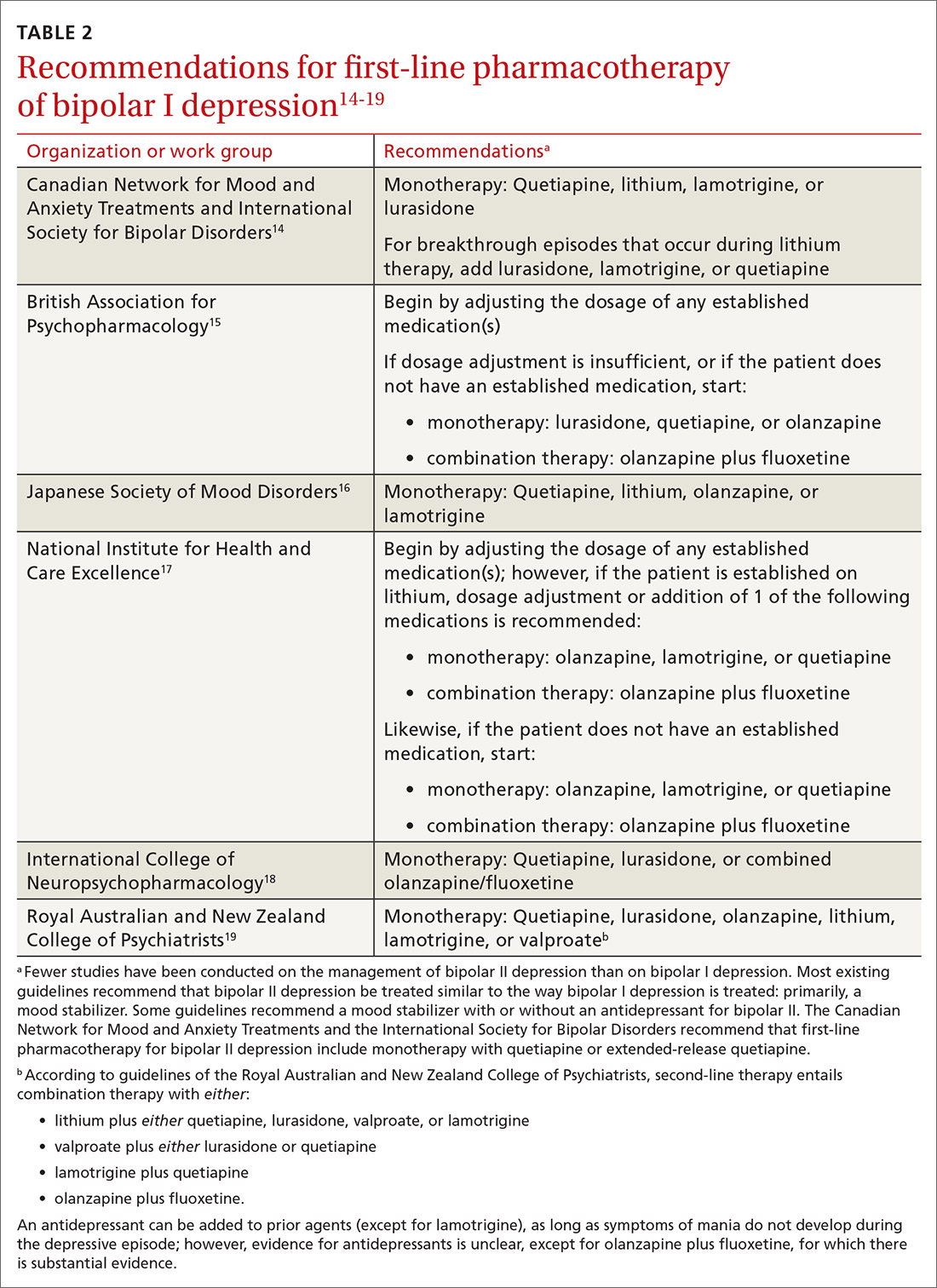

First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the management of BD in acute bipolar I are listed and described in Table 2.4-19 Compared to the number of studies and reports on the management of BD in bipolar I, few studies have been conducted that specifically examine the treatment of BD in acute bipolar II. In practice, evidence from the treatment of BD in bipolar I has been extrapolated to the treatment of bipolar II depression. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend quetiapine as the only first-line therapy for BD in bipolar II; JSMD, CINP, and NICE guidelines do not make distinct recommendations for treating BD in bipolar II.

Patients who have BD can present de novo (ie, not taking any medication for bipolar disorder) or with a breakthrough episode while on maintenance medication(s). In either case, monotherapy for BD is preferred, although combinations of medications (Table 214-19) can be more effective in some cases. Treatment guidelines overlap to a high degree, especially in regard to first-line treatments, but there is variation, especially beyond first-line therapeutics.20

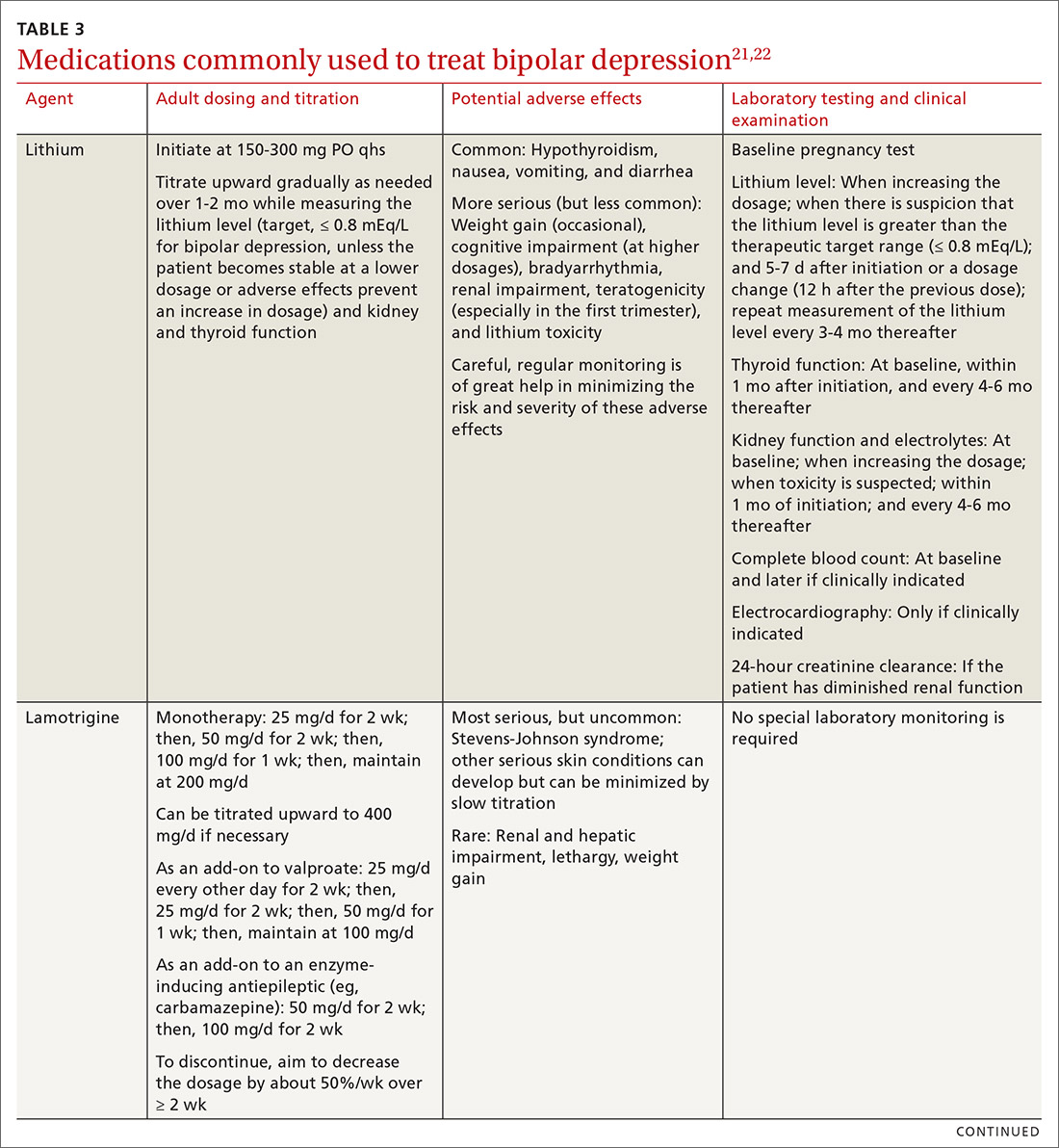

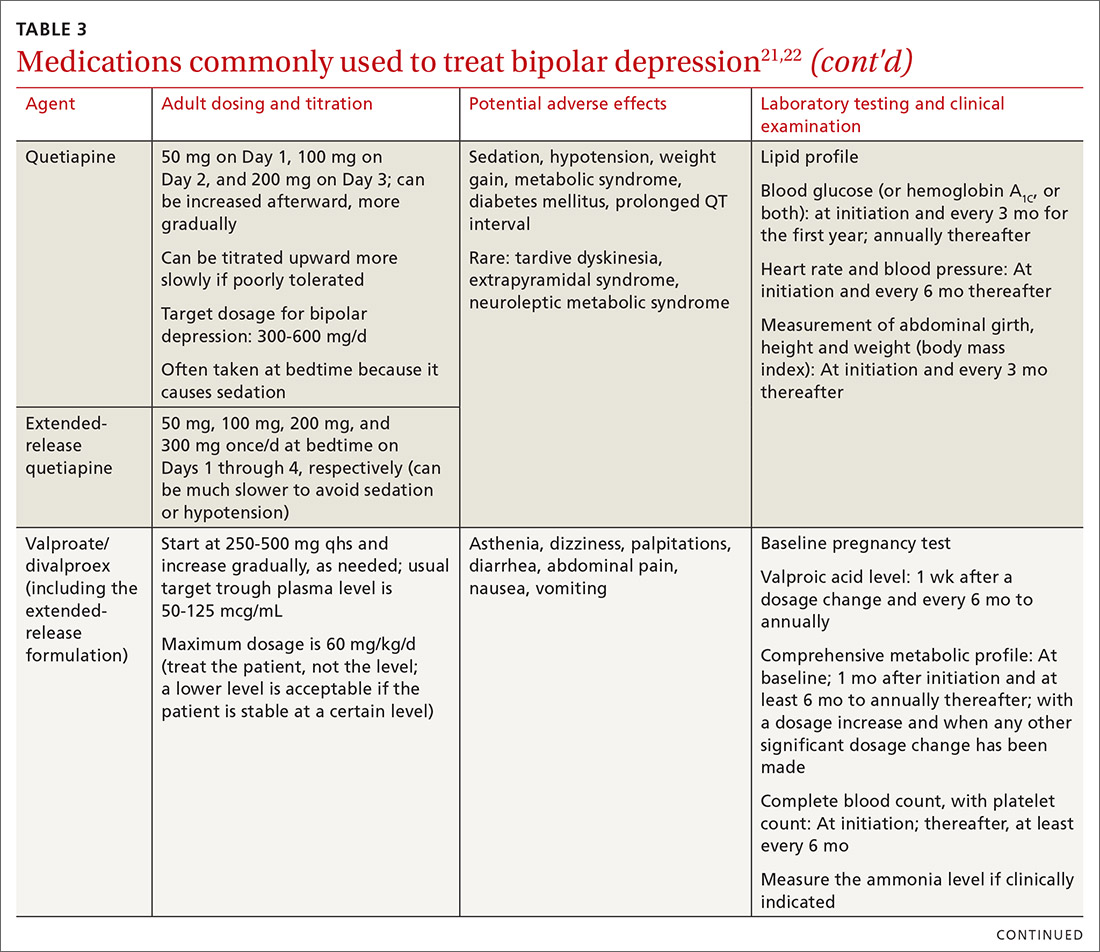

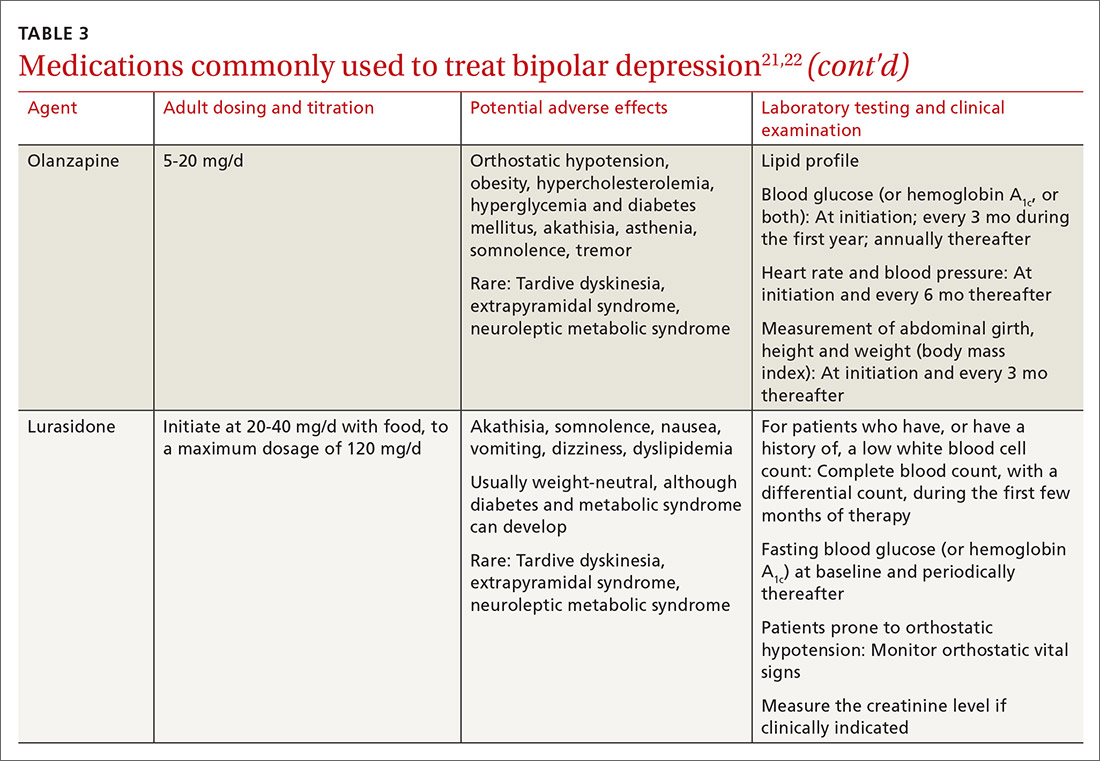

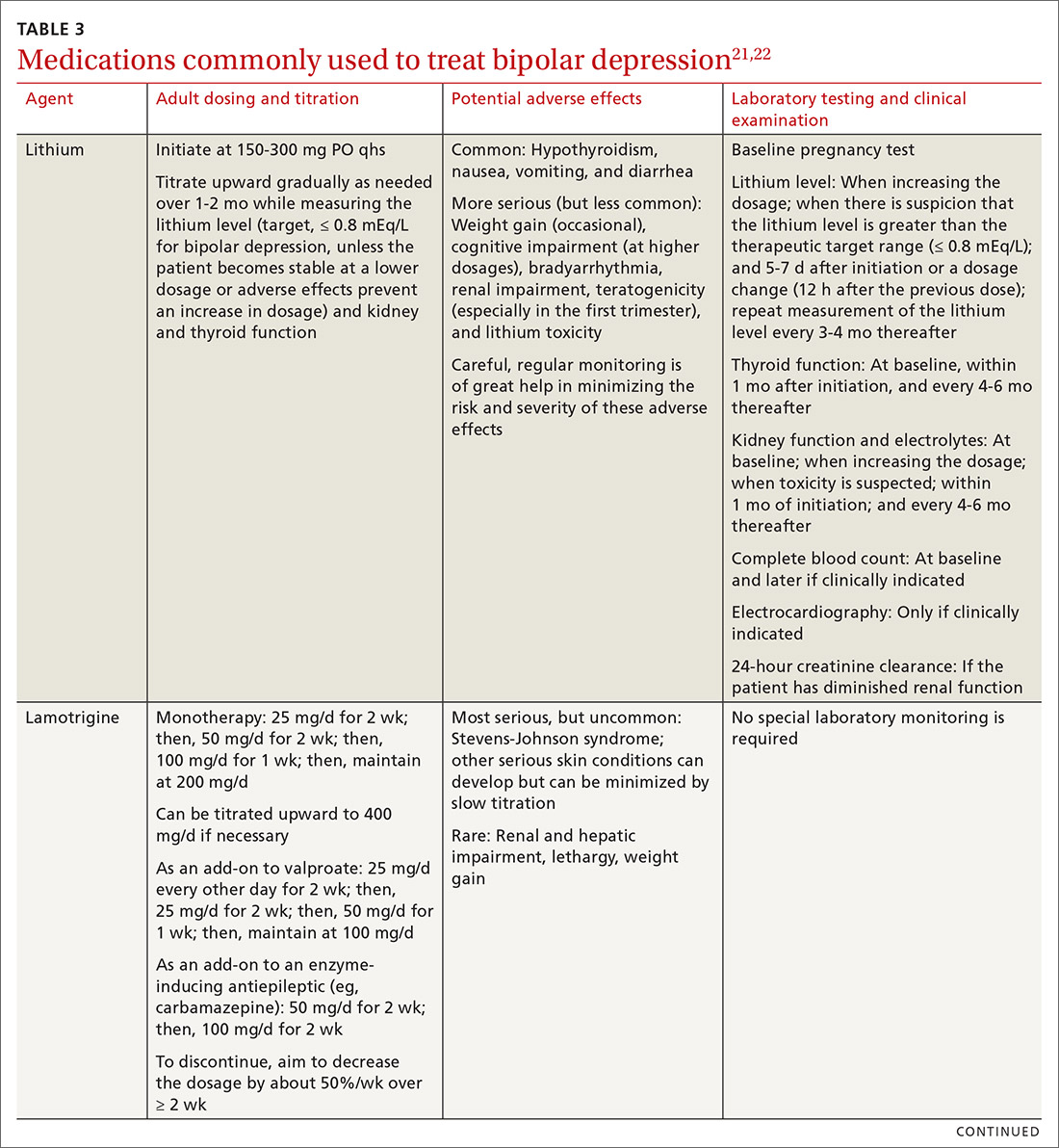

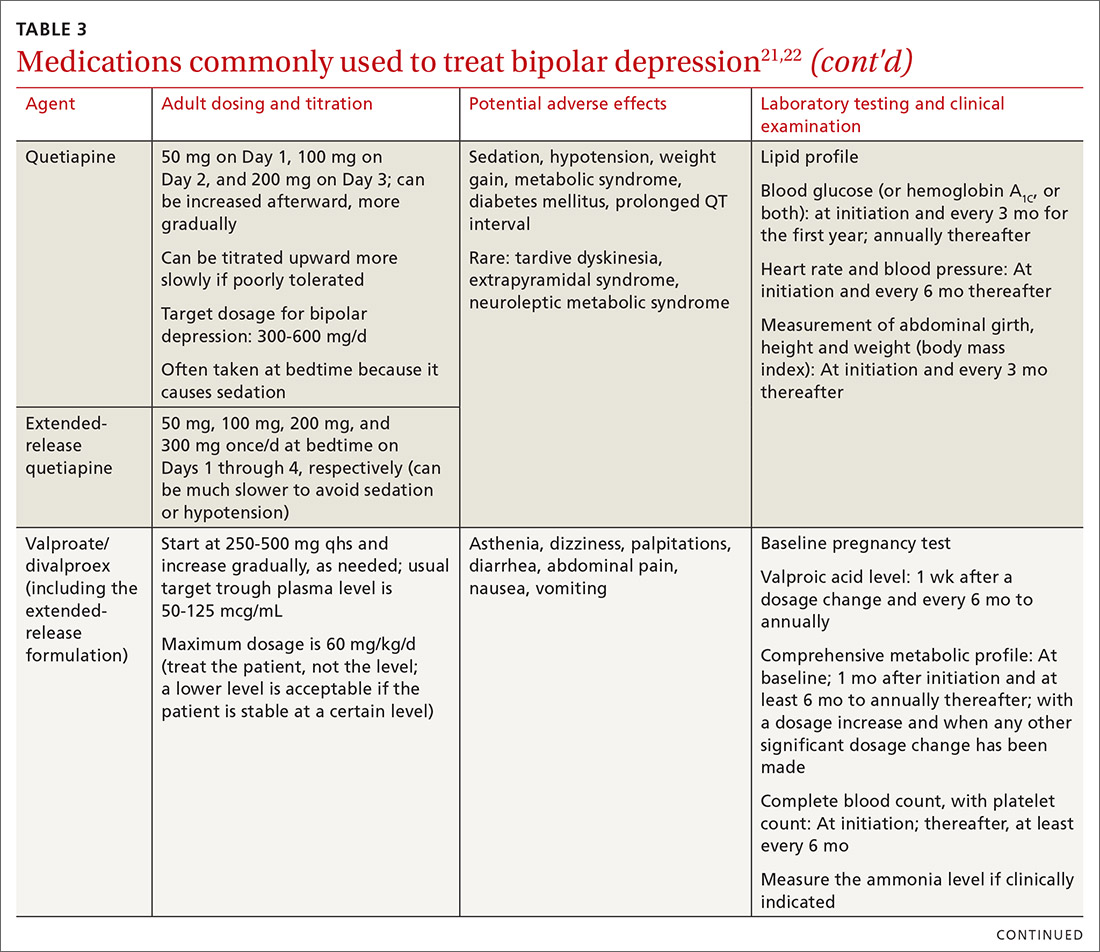

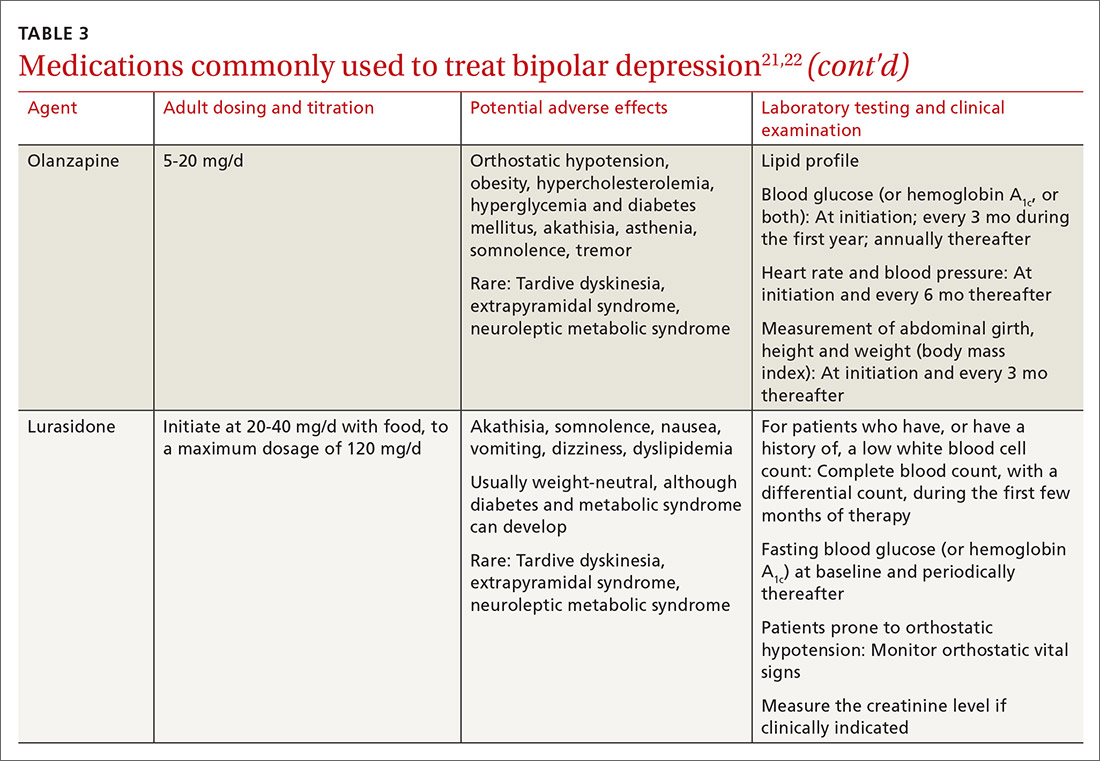

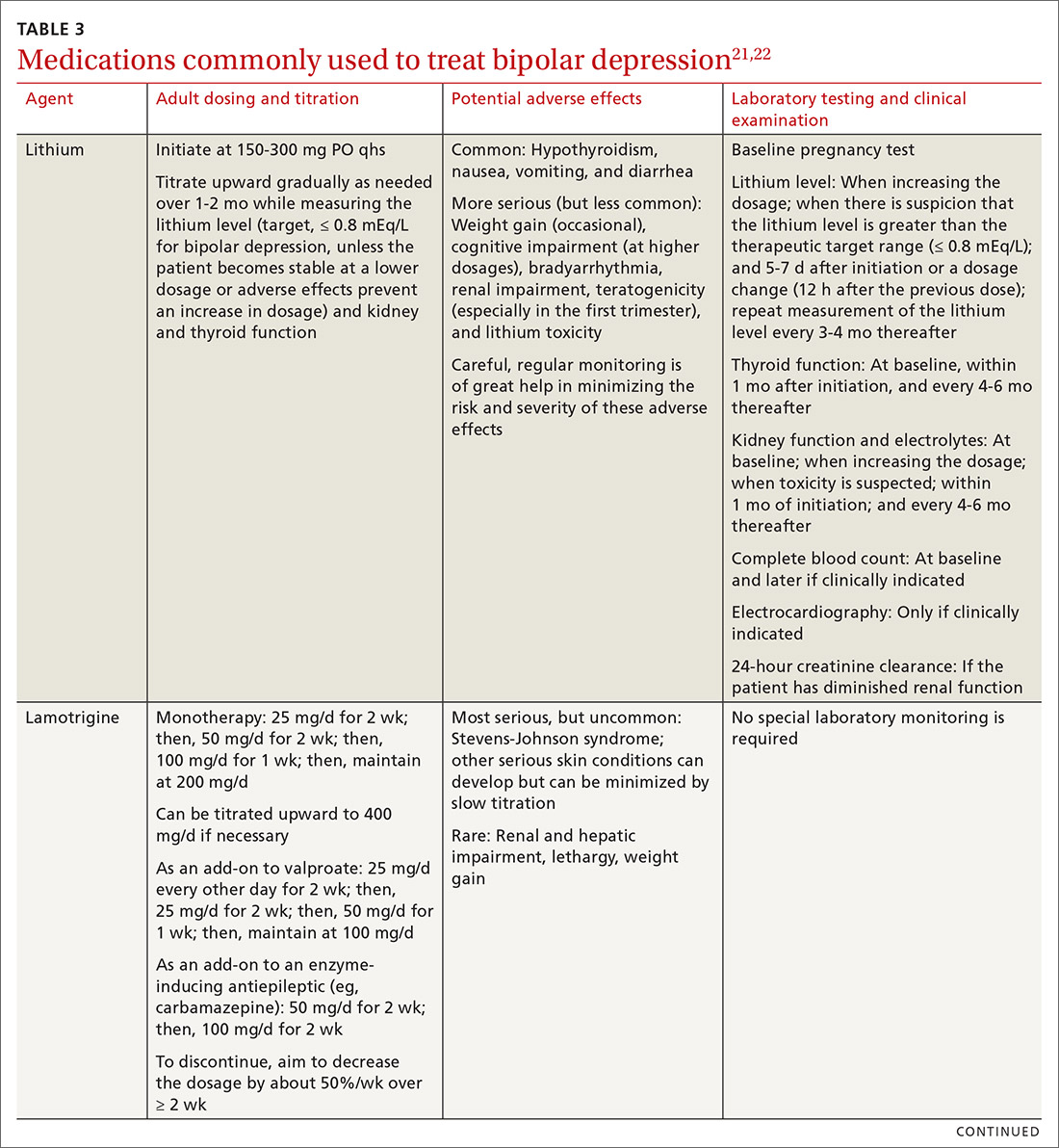

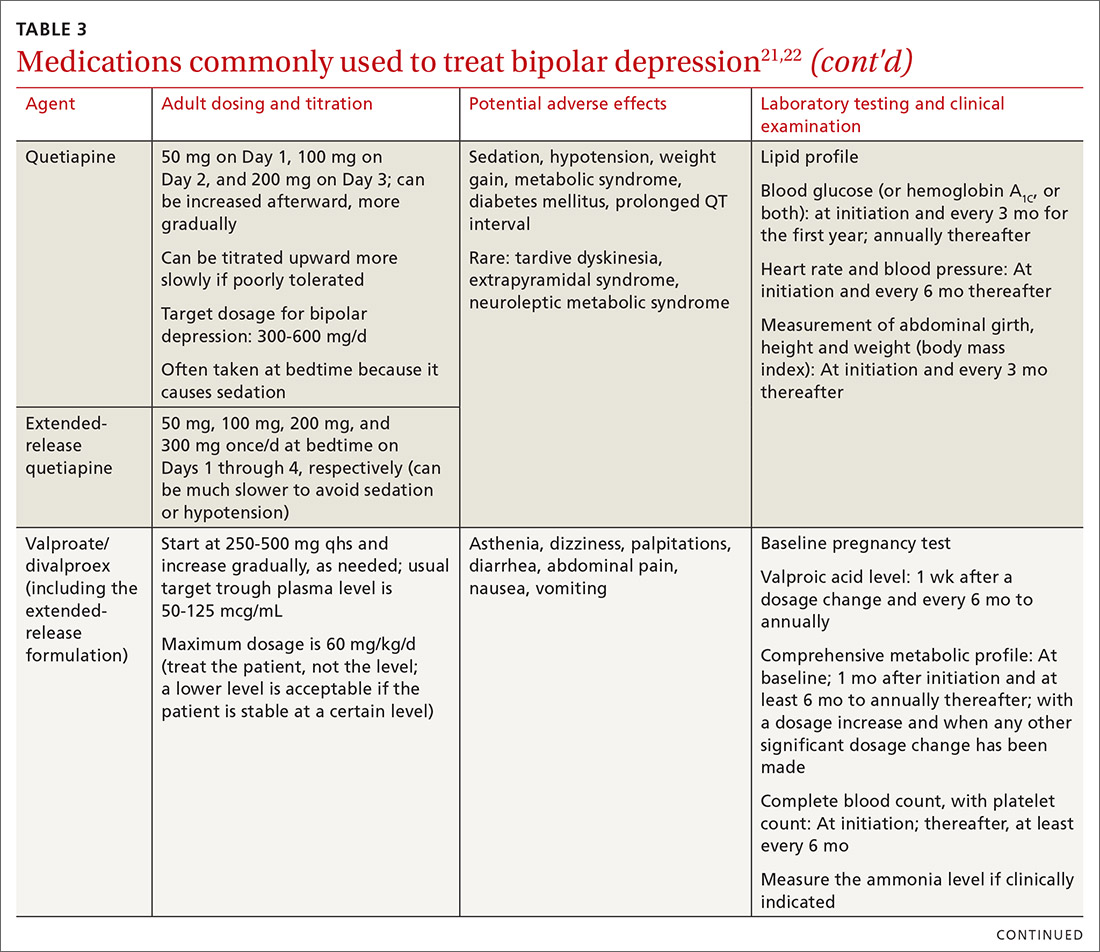

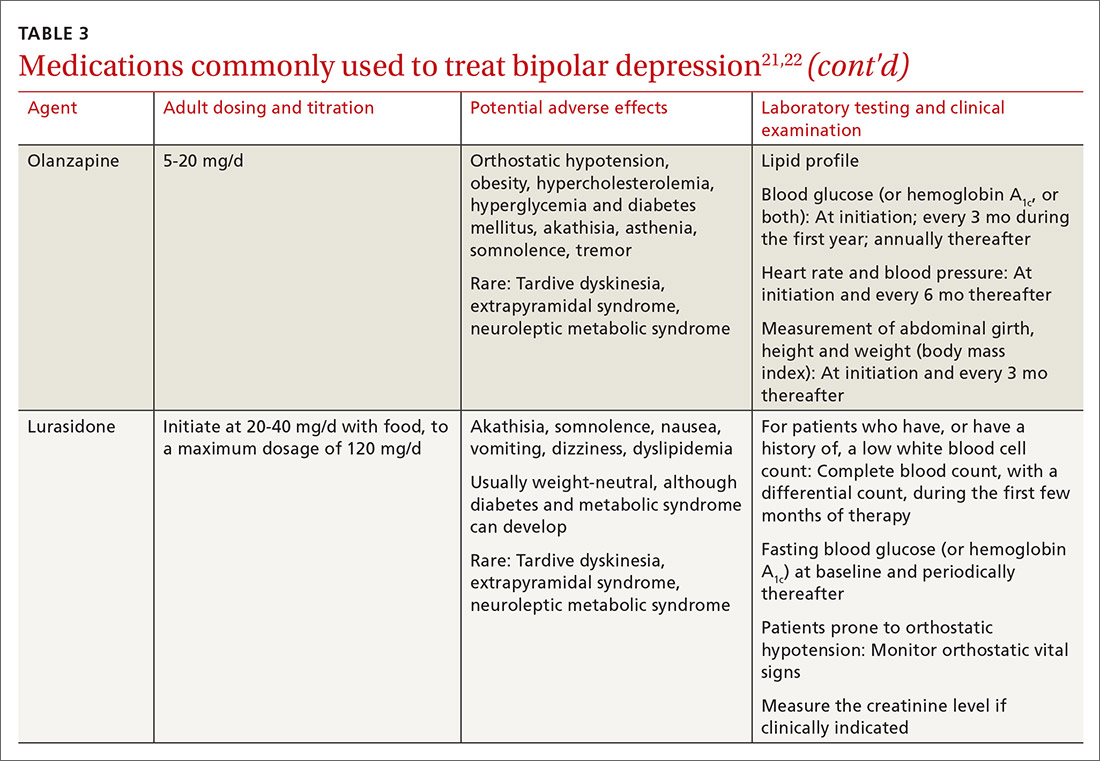

The top recommended medications for BD are lithium, quetiapine, olanzapine, lamotrigine, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. FDA-approved agents for treating acute BD specifically include quetiapine, lurasidone, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. Guidelines generally recommend a first step of adjusting the dosage of medications in any established regimen before changing or adding other agents. If clinical improvement is not seen using any recommended medications, psychiatric referral is recommended. See Table 321,22 for dosing and titration guidance and highlights of both common and rare but serious adverse effects.

Continue to: Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Start with lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, or lurasidone as the first-line medication at the dosages given in Table 3.21,22 Olanzapine alone, or in combination with fluoxetine, can be used when it has been determined that the medications listed above are ineffective.

Note that lithium requires regular blood monitoring (Table 321,22). However, lithium has the advantage of strong supporting evidence of benefit in all mood episodes of bipolar disorders (depressive, manic, hypomanic), as well as maintenance, prevention of recurrence, and anti-suicidal properties.

Also of note: Lurasidone is much more costly than other recommended medications because it is available only by brand name in the United States; the other agents are available as generics. Consider generic equivalents of the recommended agents when cost is an important factor, in part because of the impact that cost has on medication adherence for some patients.

Last, olanzapine should be used later in the treatment algorithm, unless rapid control of symptoms is needed or other first-line medications are ineffective or not tolerated—given the higher propensity of the drug to produce weight gain and cause metabolic problems, including obesity and hyperglycemia.

The importance of maintenance therapy

Almost all patients with BD require maintenance treatment to prevent subsequent episodes, reduce residual symptoms, and restore functioning and quality of life. Maintenance therapy is formulated on the basis of efficacy and tolerability in the individual patient.

Continue to: As a general rule...

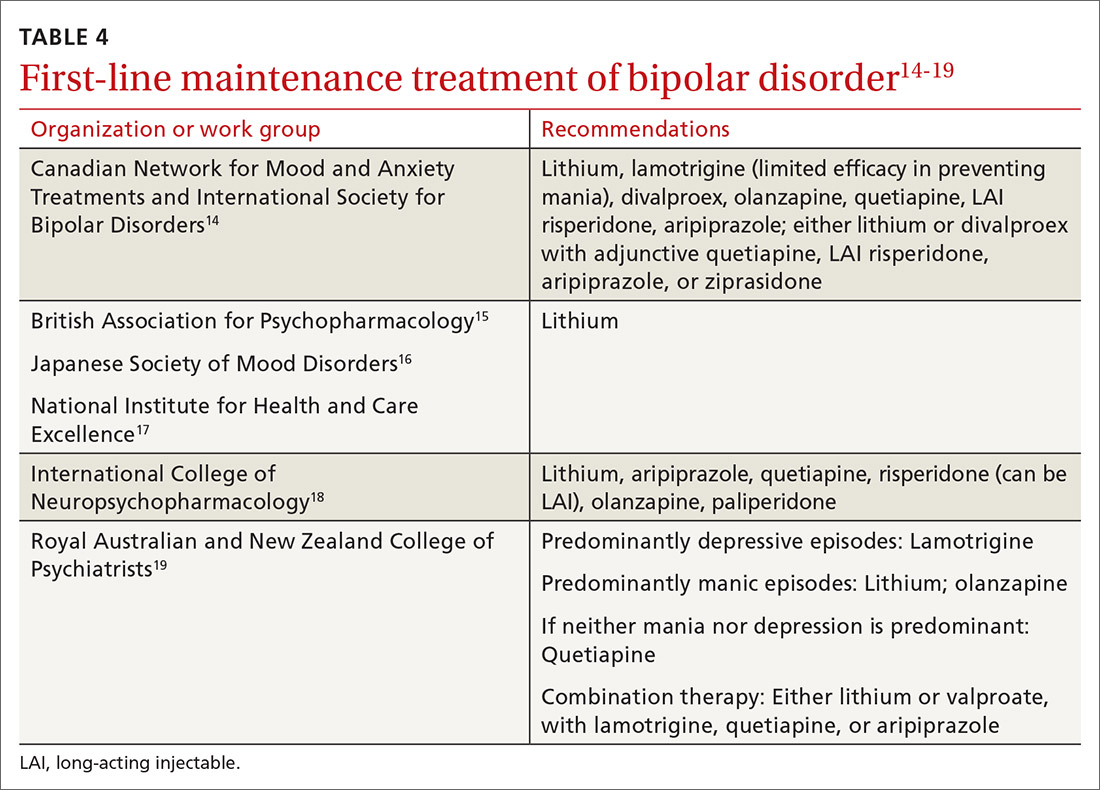

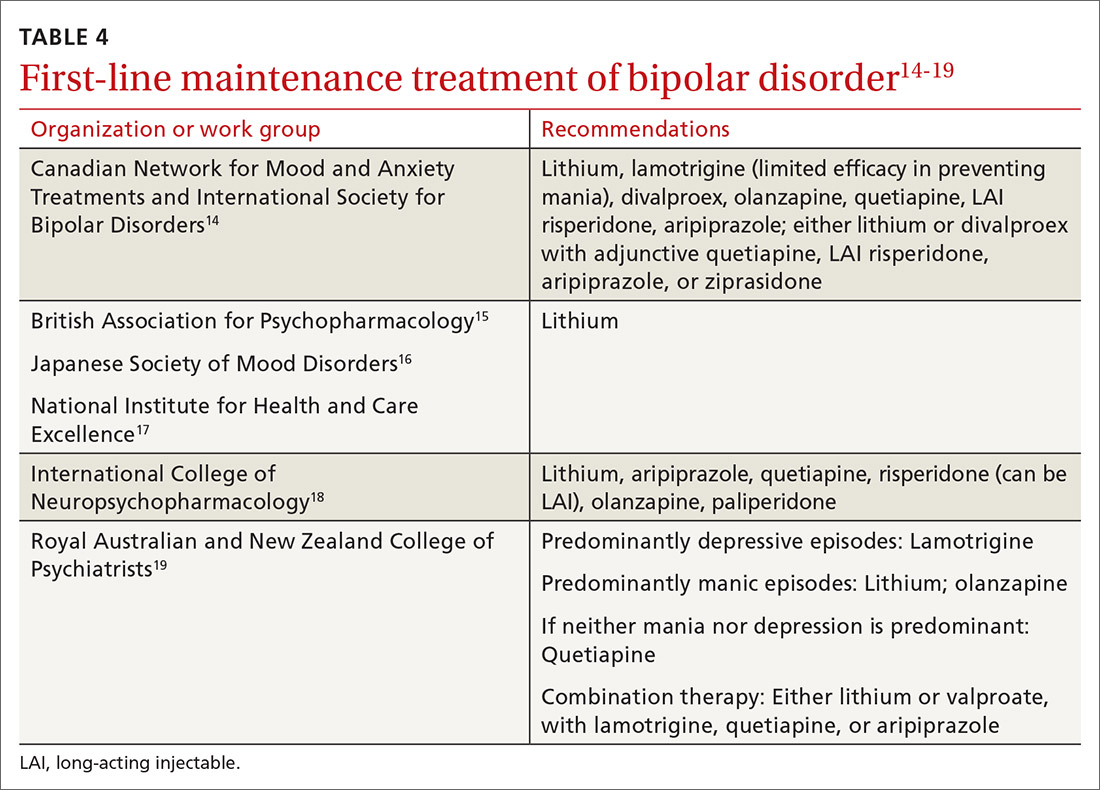

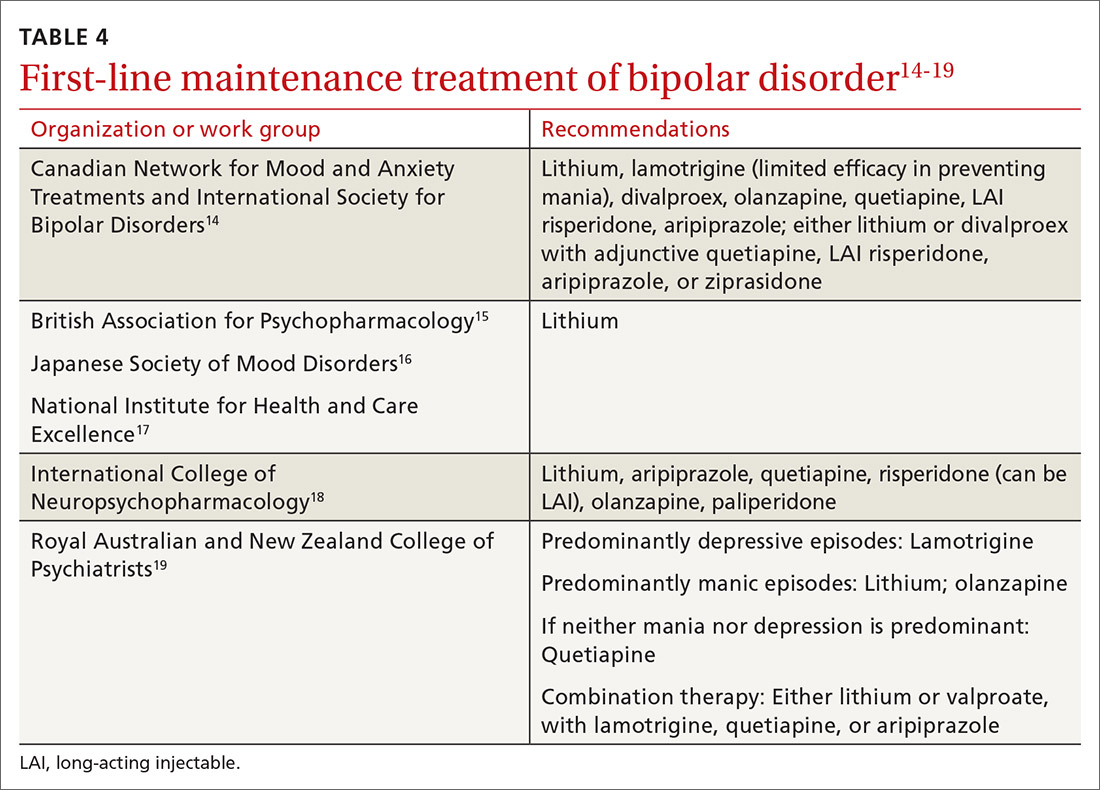

As a general rule, the strongest evidence for preventing recurrent BD episodes favors lithium—and most guidelines therefore support lithium as first-line maintenance therapy. It is important to note, however, that if a medication (or medications) successfully aborted an acute BD episode in a given patient, that agent (or agents) should be continued for maintenance purposes to prevent or minimize future episodes—generally, at the same dosage. First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the maintenance of bipolar disorder, and thus to prevent subsequent episodes of BD, are listed in Table 4.14-19

℞ antidepressantsin bipolar depression?

The use of antidepressants to treat BD remains a topic of ongoing deliberation. Antidepressant treatment of BD has historically raised concern for depressive relapse due to ineffectiveness and the ability of antidepressants to increase (1) the frequency of manic and hypomanic episodes23 and (2) mood instability in the form of induction of mixed states or rapid cycling. Among most authorities, the recommendation against using antidepressants for BD in both bipolar I and II is the same; however, limited evidence allows the use of antidepressant monotherapy in select cases of BD episodes in bipolar II,24,25 although not bipolar I.

The consensus in the field is that medications with mood-stabilizing effects should be considered as monotherapy before adding an antidepressant (if an antidepressant is to be added) to treat BD in bipolar II.26 In other words, if an antidepressant is to be used at all, it should be combined with a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic15,27 and should probably not be used long term. The efficacy of antidepressants in treating BD in bipolar II should be assessed periodically at follow-up.

Nonpharmaceutical treatment options

Although pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment of BD, adjunctive psychotherapy can be useful for treating acute BD episodes that occur during the maintenance phase of the disorder. Psychoeducation (ie, education on psychiatric illness and the importance of medication adherence), alone or in combination with interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT), family-focused therapy (FFT), and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can add to the overall efficacy of pharmacotherapy by lowering the risk of relapse and enhancing psychosocial functioning.28

IPSRT is supported by what is known as the instability model, which specifies that 3 interconnected pathways trigger recurrences of a bipolar episode: stressful life events, medication nonadherence, and social-rhythm disruption. IPSRT also uses principles of interpersonal psychotherapy that are applied in treating MDD, “arguing that improvement in interpersonal relationships can ameliorate affective symptoms and prevent their return.”29,30

Continue to: FFT

FFT focuses on communication styles between patients and their spouses and families. The goal is to improve relationship functioning. FFT is delivered to the patient and the family.

Attention to social factors. For psychotherapy to provide adequate results as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, social stressors (eg, homelessness and financial concerns) might also need to be considered and addressed through social services or a social work consult.

NICE guidelines recommend psychological intervention (in particular, with CBT and FFT) for acute BD. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend either adjunctive psychoeducation, CBT, or FFT during the maintenance phase. Again, medication is the mainstay of treatment for BD in bipolar disorders; psychotherapy has an adjunctive role—unlike the approach to treatment of MDD, in which psychotherapy can be used alone in cases of mild, or even moderate, severity.

Referral for specialty care

In the primary care setting, providers might choose to manage BD by initiating first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents or continuing established treatment regimens with necessary dosage adjustments. These patients should be monitored closely until symptoms remit.

However, it is important for the primary care provider to identify patients who need psychiatric referral. Complex presentations, severe symptoms, and poor treatment response might warrant evaluation and management by a psychiatrist. Furthermore, patients with comorbid psychotic features, catatonia, or severely debilitating depression (with or without suicidality) need referral to the emergency department.

Continue to: Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Patients might also need referral to Psychiatry for ECT, which is recommended by CANMAT–ISBD and JSMD guidelines as a second-line option; by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists as a third-line option; and by BAP for cases that are resistant to conventional treatment, with or without a high risk of suicide; in pregnancy; and in life-threatening situations.15,31,32

Telemedicine. There is a considerable shortage of mental health care professionals.33,34 The fact that nearly all (96%) counties in the United States have an unmet need for prescribers of mental health services (mainly psychiatrists) makes it crucial that primary care physicians be knowledgeable and prepared to manage BD—often with infrequent psychiatry consultation or, even, without psychiatry consultation. For primary care facilities that lack access to psychiatric services, telemedicine can be used as a consultative resource.

Psychiatric consultation using telemedicine technologies has provided significant cost savings for medical centers and decreased the likelihood of hospital admission,35 thereby alleviating health care costs and improving care, as shown in a rural Kansas county study.36 Furthermore, the burden on emergency departments in several states has been significantly reduced with psychiatric consultations via interactive telemedicine technologies.37

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Mark Yassa, BS, provided editing assistance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy Youssef, MD, PhD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; [email protected].

1. Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, et al. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in general primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:19-25.

2. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Solmi M, et al. How common is bipolar disorder in general primary care attendees? A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating prevalence determined according to structured clinical assessments. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:631-639.

3. Carta MG, Norcini-Pala A, Moro MF, et al. Does mood disorder questionnaire identify sub-threshold bipolarity? Evidence studying worsening of quality of life. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:173-178.

4. Fonseca-Pedrero E, Ortuno-Sierra J, Paino M, et al. Screening the risk of bipolar spectrum disorders: validity evidence of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire in adolescents and young adults. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016;9:4-12.

5. Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD009531.

6. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:790-804.

7. Aquadro E, Youssef NA. Combine these screening tools to detect bipolar depression. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:500-503.

8. Bipolar and related disorders. In: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013:123.

9. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J Affect Disord. 2013;73:19-32.

10. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

11. Simon GE, Bauer MS, Ludman EJ, et al. Mood symptoms, functional impairment, and disability in people with bipolar disorder: specific effects of mania and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1237-1245.

12. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, et al. Residual symptom recovery from major affective episodes in bipolar disorders and rapid episode relapse/recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:386-394.

13. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Solomon DA, et al. Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:49-58.

14. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97-170.

15. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:495-553.

16. Kanba S, Kato T, Terao T, et al; Committee for Treatment Guidelines of Mood Disorders, Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012. Guideline for treatment of bipolar disorder by the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:285-300.

17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management. Clinical Guideline CG185. September 24, 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185. Accessed August 17, 2020.

18. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 3: the clinical guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:180-195.

19. Malhi GS, Outhred T, Morris G, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: bipolar disorder summary. Med J Aust. 2018;208:219-225.

20. Hammett S, Youssef NA. Systematic review of recent guidelines for pharmacological treatments of bipolar disorders in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29:266-282.

21. Gabbard GO, ed. Gabbard’s Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2014: chap 12-15.

22. National Health Service. Guidelines for the monitoring of antimanic and prophylactic medication in bipolar disorder. NHT policy number MM-G-023. 2009. http://fac.ksu.edu.sa/sites/default/files/bipolar_disorder_guidelines.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2020.

23. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653-661.

24. Amsterdam JD, Lorenzo-Luaces L, Soeller I, et al. Safety and effectiveness of continuation antidepressant versus mood stabilizer monotherapy for relapse-prevention of bipolar II depression: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:31-37.

25. Parker G, Tully L, Olley A, et al. SSRIs as mood stabilizers for bipolar II disorder? A proof of concept study. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:205-214.

26. Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1249-1262.

27. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for Bipolar Disorder. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:280-305.

28. Chiang K-J, Tsai J-C, Liu D, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176849.

29. de Mello MF, de Jesus Mari J, Bacaltchuk J, et al. A systematic review of research findings on the efficacy of interpersonal therapy for depressive disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:75-82.

30. Zhou X, Teng T, Zhang Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:581-601.

31. Daly JJ, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. ECT in bipolar and unipolar depression: differences in speed of response. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:95-104.

32. Medda P, Perugi G, Zanello S, et al. Response to ECT in bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:55-59.

33. Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Thomas KC, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1315-1322.

34. Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1323-1328.

35. Narasimhan M, Druss BG, Hockenberry JM, et al. Impact of a telepsychiatry program at emergency departments statewide on the quality, utilization, and costs of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:1167-1172.

36. Spaulding R, Belz N, DeLurgio S, et al. Cost savings of telemedicine utilization for child psychiatry in a rural Kansas community. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:867-871.

37. States leverage telepsychiatry solutions to ease ED crowding, accelerate care. ED Manag. 2015;27:13-17.

Bipolar disorder is a prevalent disorder in the primary care setting.1,2 Primary care providers therefore commonly encounter bipolar depression (BD; a major depressive episode in the context of bipolar disorder), which might be (1) an emerging depressive episode in previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder or (2) a recurrent episode during the course of chronic bipolar illness.3,4

A primary care–based collaborative model has been identified as a potential strategy for effective management of chronic mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder.5,6 However, this collaborative treatment model isn’t widely available; many patients with bipolar disorder are, in fact, treated solely by their primary care provider.

Two years ago in this journal,7 we addressed how to precisely identify an episode of BD and differentiate it from major depressive disorder (MDD; also known as unipolar depression). In this review, in addition to advancing clinical knowledge of BD, we provide:

- an overview of treatment options for BD (in contrast to the treatment of unipolar depression)

- the pharmacotherapeutic know-how to initiate and maintain treatment for uncomplicated episodes of BD.

We do not discuss management of manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes of bipolar disorder.

How to identify bipolar depression

Understanding the (sometimes) unclear distinction between bipolar I and bipolar II disorders in an individual patient is key to formulating a therapeutic regimen for BD.

Bipolar I disorder consists of manic episodes, alternating (more often than not) with depressive episodes. Bipolar I usually manifests first with a depressive episode.

Bipolar II disorder manifests with depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes (but never manic episodes).

Continue to: Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders

Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders. Bipolar depression can be seen in the settings of both bipolar I and II disorders. When a patient presents with a manic episode, a history of depressive episodes is common (although not essential) to diagnose bipolar I; alternatively, a history of hypomania (but no prior mania) and depression is needed to make the diagnosis of bipolar II. The natural history of the bipolar disorders is therefore alternating manic and almost always depressive episodes (bipolar I) and alternating hypomanic and always depressive episodes (bipolar II).8

Symptoms of hypomanic episodes are similar to what are seen in manic episodes, but are of shorter duration (≥ 4 days [episodes of mania are at least of 1 week’s duration]), lower intensity (no psychotic symptoms), and not associated with significant functional impairment or hospitalization. Table 17 further describes the differentiating features of bipolar I and bipolar II. A history of an unequivocal manic or hypomanic episode makes the diagnosis of BD relatively easy. However, an unclear history of manic or hypomanic symptoms or episodes frequently leads to misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of BD.

In both bipolar I and II, it is depressive symptoms and episodes that place the greatest burden on patients across the lifespan: They are the most commonly experienced features of the bipolar disorders9,10 and lead to significant distress and functional impairment11; in fact, patients with bipolar disorder spend 3 (or more) times as long in depressive episodes as in manic or hypomanic episodes.12,13 In addition, subthreshold depressive symptoms occur commonly between major mood episodes.

Failure to identify and adequately treat depressive episodes of the bipolar disorders can have serious consequences: Patients are at risk of a worsening course of illness, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, chronic disability, mixed states, rapid cycling of mood episodes, and suicide.

Guidelines for treating bipolar depression

Despite the similarity in presenting symptoms and signs of depressive episodes in bipolar disorders and MDD, treating episodes of BD is significantly different than treating MDD. Antidepressant monotherapy, a mainstay of treatment for MDD, has limited utility in BD (especially depressive episodes of bipolar I) because of its limited efficacy and potential to destabilize mood, lead to rapid cycling, and induce mania or hypomania. Treatment options for BD include pharmacotherapy (the primary modality), psychological intervention (a useful adjunct, described later), and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT; highly worth considering in severe or treatment-resistant cases).

Continue to: For this article...

For this article, we searched PubMed and Google Scholar for guidelines for the management of bipolar disorders in adults that were published between July 2013 (when the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved lurasidone for the treatment of BD) and March 2019. Related guideline-referenced articles and clinical trials were also reviewed.

Our search identified 6 guidelines issued during the search period, developed by the:

- Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD),14

- British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP),15

- Japanese Society of Mood Disorders (JSMD),16

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),17

- International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP),18 and

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.19

How to manage an episode of bipolar depression

First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the management of BD in acute bipolar I are listed and described in Table 2.4-19 Compared to the number of studies and reports on the management of BD in bipolar I, few studies have been conducted that specifically examine the treatment of BD in acute bipolar II. In practice, evidence from the treatment of BD in bipolar I has been extrapolated to the treatment of bipolar II depression. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend quetiapine as the only first-line therapy for BD in bipolar II; JSMD, CINP, and NICE guidelines do not make distinct recommendations for treating BD in bipolar II.

Patients who have BD can present de novo (ie, not taking any medication for bipolar disorder) or with a breakthrough episode while on maintenance medication(s). In either case, monotherapy for BD is preferred, although combinations of medications (Table 214-19) can be more effective in some cases. Treatment guidelines overlap to a high degree, especially in regard to first-line treatments, but there is variation, especially beyond first-line therapeutics.20

The top recommended medications for BD are lithium, quetiapine, olanzapine, lamotrigine, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. FDA-approved agents for treating acute BD specifically include quetiapine, lurasidone, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. Guidelines generally recommend a first step of adjusting the dosage of medications in any established regimen before changing or adding other agents. If clinical improvement is not seen using any recommended medications, psychiatric referral is recommended. See Table 321,22 for dosing and titration guidance and highlights of both common and rare but serious adverse effects.

Continue to: Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Start with lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, or lurasidone as the first-line medication at the dosages given in Table 3.21,22 Olanzapine alone, or in combination with fluoxetine, can be used when it has been determined that the medications listed above are ineffective.

Note that lithium requires regular blood monitoring (Table 321,22). However, lithium has the advantage of strong supporting evidence of benefit in all mood episodes of bipolar disorders (depressive, manic, hypomanic), as well as maintenance, prevention of recurrence, and anti-suicidal properties.

Also of note: Lurasidone is much more costly than other recommended medications because it is available only by brand name in the United States; the other agents are available as generics. Consider generic equivalents of the recommended agents when cost is an important factor, in part because of the impact that cost has on medication adherence for some patients.

Last, olanzapine should be used later in the treatment algorithm, unless rapid control of symptoms is needed or other first-line medications are ineffective or not tolerated—given the higher propensity of the drug to produce weight gain and cause metabolic problems, including obesity and hyperglycemia.

The importance of maintenance therapy

Almost all patients with BD require maintenance treatment to prevent subsequent episodes, reduce residual symptoms, and restore functioning and quality of life. Maintenance therapy is formulated on the basis of efficacy and tolerability in the individual patient.

Continue to: As a general rule...

As a general rule, the strongest evidence for preventing recurrent BD episodes favors lithium—and most guidelines therefore support lithium as first-line maintenance therapy. It is important to note, however, that if a medication (or medications) successfully aborted an acute BD episode in a given patient, that agent (or agents) should be continued for maintenance purposes to prevent or minimize future episodes—generally, at the same dosage. First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the maintenance of bipolar disorder, and thus to prevent subsequent episodes of BD, are listed in Table 4.14-19

℞ antidepressantsin bipolar depression?

The use of antidepressants to treat BD remains a topic of ongoing deliberation. Antidepressant treatment of BD has historically raised concern for depressive relapse due to ineffectiveness and the ability of antidepressants to increase (1) the frequency of manic and hypomanic episodes23 and (2) mood instability in the form of induction of mixed states or rapid cycling. Among most authorities, the recommendation against using antidepressants for BD in both bipolar I and II is the same; however, limited evidence allows the use of antidepressant monotherapy in select cases of BD episodes in bipolar II,24,25 although not bipolar I.

The consensus in the field is that medications with mood-stabilizing effects should be considered as monotherapy before adding an antidepressant (if an antidepressant is to be added) to treat BD in bipolar II.26 In other words, if an antidepressant is to be used at all, it should be combined with a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic15,27 and should probably not be used long term. The efficacy of antidepressants in treating BD in bipolar II should be assessed periodically at follow-up.

Nonpharmaceutical treatment options

Although pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment of BD, adjunctive psychotherapy can be useful for treating acute BD episodes that occur during the maintenance phase of the disorder. Psychoeducation (ie, education on psychiatric illness and the importance of medication adherence), alone or in combination with interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT), family-focused therapy (FFT), and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can add to the overall efficacy of pharmacotherapy by lowering the risk of relapse and enhancing psychosocial functioning.28

IPSRT is supported by what is known as the instability model, which specifies that 3 interconnected pathways trigger recurrences of a bipolar episode: stressful life events, medication nonadherence, and social-rhythm disruption. IPSRT also uses principles of interpersonal psychotherapy that are applied in treating MDD, “arguing that improvement in interpersonal relationships can ameliorate affective symptoms and prevent their return.”29,30

Continue to: FFT

FFT focuses on communication styles between patients and their spouses and families. The goal is to improve relationship functioning. FFT is delivered to the patient and the family.

Attention to social factors. For psychotherapy to provide adequate results as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, social stressors (eg, homelessness and financial concerns) might also need to be considered and addressed through social services or a social work consult.

NICE guidelines recommend psychological intervention (in particular, with CBT and FFT) for acute BD. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend either adjunctive psychoeducation, CBT, or FFT during the maintenance phase. Again, medication is the mainstay of treatment for BD in bipolar disorders; psychotherapy has an adjunctive role—unlike the approach to treatment of MDD, in which psychotherapy can be used alone in cases of mild, or even moderate, severity.

Referral for specialty care

In the primary care setting, providers might choose to manage BD by initiating first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents or continuing established treatment regimens with necessary dosage adjustments. These patients should be monitored closely until symptoms remit.

However, it is important for the primary care provider to identify patients who need psychiatric referral. Complex presentations, severe symptoms, and poor treatment response might warrant evaluation and management by a psychiatrist. Furthermore, patients with comorbid psychotic features, catatonia, or severely debilitating depression (with or without suicidality) need referral to the emergency department.

Continue to: Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Patients might also need referral to Psychiatry for ECT, which is recommended by CANMAT–ISBD and JSMD guidelines as a second-line option; by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists as a third-line option; and by BAP for cases that are resistant to conventional treatment, with or without a high risk of suicide; in pregnancy; and in life-threatening situations.15,31,32

Telemedicine. There is a considerable shortage of mental health care professionals.33,34 The fact that nearly all (96%) counties in the United States have an unmet need for prescribers of mental health services (mainly psychiatrists) makes it crucial that primary care physicians be knowledgeable and prepared to manage BD—often with infrequent psychiatry consultation or, even, without psychiatry consultation. For primary care facilities that lack access to psychiatric services, telemedicine can be used as a consultative resource.

Psychiatric consultation using telemedicine technologies has provided significant cost savings for medical centers and decreased the likelihood of hospital admission,35 thereby alleviating health care costs and improving care, as shown in a rural Kansas county study.36 Furthermore, the burden on emergency departments in several states has been significantly reduced with psychiatric consultations via interactive telemedicine technologies.37

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Mark Yassa, BS, provided editing assistance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy Youssef, MD, PhD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; [email protected].

Bipolar disorder is a prevalent disorder in the primary care setting.1,2 Primary care providers therefore commonly encounter bipolar depression (BD; a major depressive episode in the context of bipolar disorder), which might be (1) an emerging depressive episode in previously undiagnosed bipolar disorder or (2) a recurrent episode during the course of chronic bipolar illness.3,4

A primary care–based collaborative model has been identified as a potential strategy for effective management of chronic mental health conditions such as bipolar disorder.5,6 However, this collaborative treatment model isn’t widely available; many patients with bipolar disorder are, in fact, treated solely by their primary care provider.

Two years ago in this journal,7 we addressed how to precisely identify an episode of BD and differentiate it from major depressive disorder (MDD; also known as unipolar depression). In this review, in addition to advancing clinical knowledge of BD, we provide:

- an overview of treatment options for BD (in contrast to the treatment of unipolar depression)

- the pharmacotherapeutic know-how to initiate and maintain treatment for uncomplicated episodes of BD.

We do not discuss management of manic, hypomanic, and mixed episodes of bipolar disorder.

How to identify bipolar depression

Understanding the (sometimes) unclear distinction between bipolar I and bipolar II disorders in an individual patient is key to formulating a therapeutic regimen for BD.

Bipolar I disorder consists of manic episodes, alternating (more often than not) with depressive episodes. Bipolar I usually manifests first with a depressive episode.

Bipolar II disorder manifests with depressive episodes and hypomanic episodes (but never manic episodes).

Continue to: Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders

Depressive episodes in the bipolar disorders. Bipolar depression can be seen in the settings of both bipolar I and II disorders. When a patient presents with a manic episode, a history of depressive episodes is common (although not essential) to diagnose bipolar I; alternatively, a history of hypomania (but no prior mania) and depression is needed to make the diagnosis of bipolar II. The natural history of the bipolar disorders is therefore alternating manic and almost always depressive episodes (bipolar I) and alternating hypomanic and always depressive episodes (bipolar II).8

Symptoms of hypomanic episodes are similar to what are seen in manic episodes, but are of shorter duration (≥ 4 days [episodes of mania are at least of 1 week’s duration]), lower intensity (no psychotic symptoms), and not associated with significant functional impairment or hospitalization. Table 17 further describes the differentiating features of bipolar I and bipolar II. A history of an unequivocal manic or hypomanic episode makes the diagnosis of BD relatively easy. However, an unclear history of manic or hypomanic symptoms or episodes frequently leads to misdiagnosis or underdiagnosis of BD.

In both bipolar I and II, it is depressive symptoms and episodes that place the greatest burden on patients across the lifespan: They are the most commonly experienced features of the bipolar disorders9,10 and lead to significant distress and functional impairment11; in fact, patients with bipolar disorder spend 3 (or more) times as long in depressive episodes as in manic or hypomanic episodes.12,13 In addition, subthreshold depressive symptoms occur commonly between major mood episodes.

Failure to identify and adequately treat depressive episodes of the bipolar disorders can have serious consequences: Patients are at risk of a worsening course of illness, alcohol use disorder, substance use disorder, chronic disability, mixed states, rapid cycling of mood episodes, and suicide.

Guidelines for treating bipolar depression

Despite the similarity in presenting symptoms and signs of depressive episodes in bipolar disorders and MDD, treating episodes of BD is significantly different than treating MDD. Antidepressant monotherapy, a mainstay of treatment for MDD, has limited utility in BD (especially depressive episodes of bipolar I) because of its limited efficacy and potential to destabilize mood, lead to rapid cycling, and induce mania or hypomania. Treatment options for BD include pharmacotherapy (the primary modality), psychological intervention (a useful adjunct, described later), and electroconvulsive therapy (ECT; highly worth considering in severe or treatment-resistant cases).

Continue to: For this article...

For this article, we searched PubMed and Google Scholar for guidelines for the management of bipolar disorders in adults that were published between July 2013 (when the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] approved lurasidone for the treatment of BD) and March 2019. Related guideline-referenced articles and clinical trials were also reviewed.

Our search identified 6 guidelines issued during the search period, developed by the:

- Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD),14

- British Association for Psychopharmacology (BAP),15

- Japanese Society of Mood Disorders (JSMD),16

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE),17

- International College of Neuropsychopharmacology (CINP),18 and

- Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.19

How to manage an episode of bipolar depression

First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the management of BD in acute bipolar I are listed and described in Table 2.4-19 Compared to the number of studies and reports on the management of BD in bipolar I, few studies have been conducted that specifically examine the treatment of BD in acute bipolar II. In practice, evidence from the treatment of BD in bipolar I has been extrapolated to the treatment of bipolar II depression. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend quetiapine as the only first-line therapy for BD in bipolar II; JSMD, CINP, and NICE guidelines do not make distinct recommendations for treating BD in bipolar II.

Patients who have BD can present de novo (ie, not taking any medication for bipolar disorder) or with a breakthrough episode while on maintenance medication(s). In either case, monotherapy for BD is preferred, although combinations of medications (Table 214-19) can be more effective in some cases. Treatment guidelines overlap to a high degree, especially in regard to first-line treatments, but there is variation, especially beyond first-line therapeutics.20

The top recommended medications for BD are lithium, quetiapine, olanzapine, lamotrigine, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. FDA-approved agents for treating acute BD specifically include quetiapine, lurasidone, and combined olanzapine/fluoxetine. Guidelines generally recommend a first step of adjusting the dosage of medications in any established regimen before changing or adding other agents. If clinical improvement is not seen using any recommended medications, psychiatric referral is recommended. See Table 321,22 for dosing and titration guidance and highlights of both common and rare but serious adverse effects.

Continue to: Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Recommendations, best options for acute bipolar depression

Start with lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, or lurasidone as the first-line medication at the dosages given in Table 3.21,22 Olanzapine alone, or in combination with fluoxetine, can be used when it has been determined that the medications listed above are ineffective.

Note that lithium requires regular blood monitoring (Table 321,22). However, lithium has the advantage of strong supporting evidence of benefit in all mood episodes of bipolar disorders (depressive, manic, hypomanic), as well as maintenance, prevention of recurrence, and anti-suicidal properties.

Also of note: Lurasidone is much more costly than other recommended medications because it is available only by brand name in the United States; the other agents are available as generics. Consider generic equivalents of the recommended agents when cost is an important factor, in part because of the impact that cost has on medication adherence for some patients.

Last, olanzapine should be used later in the treatment algorithm, unless rapid control of symptoms is needed or other first-line medications are ineffective or not tolerated—given the higher propensity of the drug to produce weight gain and cause metabolic problems, including obesity and hyperglycemia.

The importance of maintenance therapy

Almost all patients with BD require maintenance treatment to prevent subsequent episodes, reduce residual symptoms, and restore functioning and quality of life. Maintenance therapy is formulated on the basis of efficacy and tolerability in the individual patient.

Continue to: As a general rule...

As a general rule, the strongest evidence for preventing recurrent BD episodes favors lithium—and most guidelines therefore support lithium as first-line maintenance therapy. It is important to note, however, that if a medication (or medications) successfully aborted an acute BD episode in a given patient, that agent (or agents) should be continued for maintenance purposes to prevent or minimize future episodes—generally, at the same dosage. First-line pharmacotherapeutic agents for the maintenance of bipolar disorder, and thus to prevent subsequent episodes of BD, are listed in Table 4.14-19

℞ antidepressantsin bipolar depression?

The use of antidepressants to treat BD remains a topic of ongoing deliberation. Antidepressant treatment of BD has historically raised concern for depressive relapse due to ineffectiveness and the ability of antidepressants to increase (1) the frequency of manic and hypomanic episodes23 and (2) mood instability in the form of induction of mixed states or rapid cycling. Among most authorities, the recommendation against using antidepressants for BD in both bipolar I and II is the same; however, limited evidence allows the use of antidepressant monotherapy in select cases of BD episodes in bipolar II,24,25 although not bipolar I.

The consensus in the field is that medications with mood-stabilizing effects should be considered as monotherapy before adding an antidepressant (if an antidepressant is to be added) to treat BD in bipolar II.26 In other words, if an antidepressant is to be used at all, it should be combined with a mood stabilizer or atypical antipsychotic15,27 and should probably not be used long term. The efficacy of antidepressants in treating BD in bipolar II should be assessed periodically at follow-up.

Nonpharmaceutical treatment options

Although pharmacotherapy is the mainstay of treatment of BD, adjunctive psychotherapy can be useful for treating acute BD episodes that occur during the maintenance phase of the disorder. Psychoeducation (ie, education on psychiatric illness and the importance of medication adherence), alone or in combination with interpersonal and social rhythm therapy (IPSRT), family-focused therapy (FFT), and cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can add to the overall efficacy of pharmacotherapy by lowering the risk of relapse and enhancing psychosocial functioning.28

IPSRT is supported by what is known as the instability model, which specifies that 3 interconnected pathways trigger recurrences of a bipolar episode: stressful life events, medication nonadherence, and social-rhythm disruption. IPSRT also uses principles of interpersonal psychotherapy that are applied in treating MDD, “arguing that improvement in interpersonal relationships can ameliorate affective symptoms and prevent their return.”29,30

Continue to: FFT

FFT focuses on communication styles between patients and their spouses and families. The goal is to improve relationship functioning. FFT is delivered to the patient and the family.

Attention to social factors. For psychotherapy to provide adequate results as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy, social stressors (eg, homelessness and financial concerns) might also need to be considered and addressed through social services or a social work consult.

NICE guidelines recommend psychological intervention (in particular, with CBT and FFT) for acute BD. CANMAT–ISBD guidelines recommend either adjunctive psychoeducation, CBT, or FFT during the maintenance phase. Again, medication is the mainstay of treatment for BD in bipolar disorders; psychotherapy has an adjunctive role—unlike the approach to treatment of MDD, in which psychotherapy can be used alone in cases of mild, or even moderate, severity.

Referral for specialty care

In the primary care setting, providers might choose to manage BD by initiating first-line pharmacotherapeutic agents or continuing established treatment regimens with necessary dosage adjustments. These patients should be monitored closely until symptoms remit.

However, it is important for the primary care provider to identify patients who need psychiatric referral. Complex presentations, severe symptoms, and poor treatment response might warrant evaluation and management by a psychiatrist. Furthermore, patients with comorbid psychotic features, catatonia, or severely debilitating depression (with or without suicidality) need referral to the emergency department.

Continue to: Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT)

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Patients might also need referral to Psychiatry for ECT, which is recommended by CANMAT–ISBD and JSMD guidelines as a second-line option; by the Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists as a third-line option; and by BAP for cases that are resistant to conventional treatment, with or without a high risk of suicide; in pregnancy; and in life-threatening situations.15,31,32

Telemedicine. There is a considerable shortage of mental health care professionals.33,34 The fact that nearly all (96%) counties in the United States have an unmet need for prescribers of mental health services (mainly psychiatrists) makes it crucial that primary care physicians be knowledgeable and prepared to manage BD—often with infrequent psychiatry consultation or, even, without psychiatry consultation. For primary care facilities that lack access to psychiatric services, telemedicine can be used as a consultative resource.

Psychiatric consultation using telemedicine technologies has provided significant cost savings for medical centers and decreased the likelihood of hospital admission,35 thereby alleviating health care costs and improving care, as shown in a rural Kansas county study.36 Furthermore, the burden on emergency departments in several states has been significantly reduced with psychiatric consultations via interactive telemedicine technologies.37

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

Mark Yassa, BS, provided editing assistance.

CORRESPONDENCE

Nagy Youssef, MD, PhD, Medical College of Georgia at Augusta University, Department of Psychiatry and Health Behavior, 997 St. Sebastian Way, Augusta, GA 30912; [email protected].

1. Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, et al. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in general primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:19-25.

2. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Solmi M, et al. How common is bipolar disorder in general primary care attendees? A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating prevalence determined according to structured clinical assessments. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:631-639.

3. Carta MG, Norcini-Pala A, Moro MF, et al. Does mood disorder questionnaire identify sub-threshold bipolarity? Evidence studying worsening of quality of life. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:173-178.

4. Fonseca-Pedrero E, Ortuno-Sierra J, Paino M, et al. Screening the risk of bipolar spectrum disorders: validity evidence of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire in adolescents and young adults. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016;9:4-12.

5. Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD009531.

6. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:790-804.

7. Aquadro E, Youssef NA. Combine these screening tools to detect bipolar depression. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:500-503.

8. Bipolar and related disorders. In: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013:123.

9. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J Affect Disord. 2013;73:19-32.

10. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

11. Simon GE, Bauer MS, Ludman EJ, et al. Mood symptoms, functional impairment, and disability in people with bipolar disorder: specific effects of mania and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1237-1245.

12. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, et al. Residual symptom recovery from major affective episodes in bipolar disorders and rapid episode relapse/recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:386-394.

13. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Solomon DA, et al. Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:49-58.

14. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97-170.

15. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:495-553.

16. Kanba S, Kato T, Terao T, et al; Committee for Treatment Guidelines of Mood Disorders, Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012. Guideline for treatment of bipolar disorder by the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:285-300.

17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management. Clinical Guideline CG185. September 24, 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185. Accessed August 17, 2020.

18. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 3: the clinical guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:180-195.

19. Malhi GS, Outhred T, Morris G, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: bipolar disorder summary. Med J Aust. 2018;208:219-225.

20. Hammett S, Youssef NA. Systematic review of recent guidelines for pharmacological treatments of bipolar disorders in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29:266-282.

21. Gabbard GO, ed. Gabbard’s Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2014: chap 12-15.

22. National Health Service. Guidelines for the monitoring of antimanic and prophylactic medication in bipolar disorder. NHT policy number MM-G-023. 2009. http://fac.ksu.edu.sa/sites/default/files/bipolar_disorder_guidelines.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2020.

23. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653-661.

24. Amsterdam JD, Lorenzo-Luaces L, Soeller I, et al. Safety and effectiveness of continuation antidepressant versus mood stabilizer monotherapy for relapse-prevention of bipolar II depression: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:31-37.

25. Parker G, Tully L, Olley A, et al. SSRIs as mood stabilizers for bipolar II disorder? A proof of concept study. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:205-214.

26. Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1249-1262.

27. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for Bipolar Disorder. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:280-305.

28. Chiang K-J, Tsai J-C, Liu D, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176849.

29. de Mello MF, de Jesus Mari J, Bacaltchuk J, et al. A systematic review of research findings on the efficacy of interpersonal therapy for depressive disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:75-82.

30. Zhou X, Teng T, Zhang Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:581-601.

31. Daly JJ, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. ECT in bipolar and unipolar depression: differences in speed of response. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:95-104.

32. Medda P, Perugi G, Zanello S, et al. Response to ECT in bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:55-59.

33. Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Thomas KC, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1315-1322.

34. Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1323-1328.

35. Narasimhan M, Druss BG, Hockenberry JM, et al. Impact of a telepsychiatry program at emergency departments statewide on the quality, utilization, and costs of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:1167-1172.

36. Spaulding R, Belz N, DeLurgio S, et al. Cost savings of telemedicine utilization for child psychiatry in a rural Kansas community. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:867-871.

37. States leverage telepsychiatry solutions to ease ED crowding, accelerate care. ED Manag. 2015;27:13-17.

1. Cerimele JM, Chwastiak LA, Dodson S, et al. The prevalence of bipolar disorder in general primary care samples: a systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2014;36:19-25.

2. Stubbs B, Vancampfort D, Solmi M, et al. How common is bipolar disorder in general primary care attendees? A systematic review and meta-analysis investigating prevalence determined according to structured clinical assessments. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50:631-639.

3. Carta MG, Norcini-Pala A, Moro MF, et al. Does mood disorder questionnaire identify sub-threshold bipolarity? Evidence studying worsening of quality of life. J Affect Disord. 2015;183:173-178.

4. Fonseca-Pedrero E, Ortuno-Sierra J, Paino M, et al. Screening the risk of bipolar spectrum disorders: validity evidence of the Mood Disorder Questionnaire in adolescents and young adults. Rev Psiquiatr Salud Ment. 2016;9:4-12.

5. Reilly S, Planner C, Gask L, et al. Collaborative care approaches for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(11):CD009531.

6. Woltmann E, Grogan-Kaylor A, Perron B, et al. Comparative effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for mental health conditions across primary, specialty, and behavioral health care settings: systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:790-804.

7. Aquadro E, Youssef NA. Combine these screening tools to detect bipolar depression. J Fam Pract. 2018;67:500-503.

8. Bipolar and related disorders. In: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2013:123.

9. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The comparative clinical phenotype and long term longitudinal episode course of bipolar I and II: a clinical spectrum or distinct disorders? J Affect Disord. 2013;73:19-32.

10. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530-537.

11. Simon GE, Bauer MS, Ludman EJ, et al. Mood symptoms, functional impairment, and disability in people with bipolar disorder: specific effects of mania and depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2007;68:1237-1245.

12. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Akiskal HS, et al. Residual symptom recovery from major affective episodes in bipolar disorders and rapid episode relapse/recurrence. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:386-394.

13. Judd LL, Schettler PJ, Solomon DA, et al. Psychosocial disability and work role function compared across the long-term course of bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar major depressive disorders. J Affect Disord. 2008;108:49-58.

14. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh S, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97-170.

15. Goodwin GM, Haddad PM, Ferrier IN, et al. Evidence-based guidelines for treating bipolar disorder: revised third edition recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:495-553.

16. Kanba S, Kato T, Terao T, et al; Committee for Treatment Guidelines of Mood Disorders, Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012. Guideline for treatment of bipolar disorder by the Japanese Society of Mood Disorders, 2012. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;67:285-300.

17. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Bipolar disorder: assessment and management. Clinical Guideline CG185. September 24, 2014. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg185. Accessed August 17, 2020.

18. Fountoulakis KN, Grunze H, Vieta E, et al. The International College of Neuro-Psychopharmacology (CINP) Treatment Guidelines for Bipolar Disorder in Adults (CINP-BD-2017), Part 3: the clinical guidelines. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:180-195.

19. Malhi GS, Outhred T, Morris G, et al. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for mood disorders: bipolar disorder summary. Med J Aust. 2018;208:219-225.

20. Hammett S, Youssef NA. Systematic review of recent guidelines for pharmacological treatments of bipolar disorders in adults. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2017;29:266-282.

21. Gabbard GO, ed. Gabbard’s Treatments of Psychiatric Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2014: chap 12-15.

22. National Health Service. Guidelines for the monitoring of antimanic and prophylactic medication in bipolar disorder. NHT policy number MM-G-023. 2009. http://fac.ksu.edu.sa/sites/default/files/bipolar_disorder_guidelines.pdf. Accessed August 17, 2020.

23. Geddes JR, Carney SM, Davies C, et al. Relapse prevention with antidepressant drug treatment in depressive disorders: a systematic review. Lancet. 2003;361:653-661.

24. Amsterdam JD, Lorenzo-Luaces L, Soeller I, et al. Safety and effectiveness of continuation antidepressant versus mood stabilizer monotherapy for relapse-prevention of bipolar II depression: a randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, prospective study. J Affect Disord. 2015;185:31-37.

25. Parker G, Tully L, Olley A, et al. SSRIs as mood stabilizers for bipolar II disorder? A proof of concept study. J Affect Disord. 2006;92:205-214.

26. Pacchiarotti I, Bond DJ, Baldessarini RJ, et al. The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) Task Force report on antidepressant use in bipolar disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1249-1262.

27. Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists Clinical Practice Guidelines Team for Bipolar Disorder. Australian and New Zealand clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of bipolar disorder. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2004;38:280-305.

28. Chiang K-J, Tsai J-C, Liu D, et al. Efficacy of cognitive-behavioral therapy in patients with bipolar disorder: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0176849.

29. de Mello MF, de Jesus Mari J, Bacaltchuk J, et al. A systematic review of research findings on the efficacy of interpersonal therapy for depressive disorders. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255:75-82.

30. Zhou X, Teng T, Zhang Y, et al. Comparative efficacy and acceptability of antidepressants, psychotherapies, and their combination for acute treatment of children and adolescents with depressive disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7:581-601.

31. Daly JJ, Prudic J, Devanand DP, et al. ECT in bipolar and unipolar depression: differences in speed of response. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:95-104.

32. Medda P, Perugi G, Zanello S, et al. Response to ECT in bipolar I, bipolar II and unipolar depression. J Affect Disord. 2009;118:55-59.

33. Ellis AR, Konrad TR, Thomas KC, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional supply in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1315-1322.

34. Thomas KC, Ellis AR, Konrad TR, et al. County-level estimates of mental health professional shortage in the United States. Psychiatr Serv. 2009;60:1323-1328.

35. Narasimhan M, Druss BG, Hockenberry JM, et al. Impact of a telepsychiatry program at emergency departments statewide on the quality, utilization, and costs of mental health services. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66:1167-1172.

36. Spaulding R, Belz N, DeLurgio S, et al. Cost savings of telemedicine utilization for child psychiatry in a rural Kansas community. Telemed J E Health. 2010;16:867-871.

37. States leverage telepsychiatry solutions to ease ED crowding, accelerate care. ED Manag. 2015;27:13-17.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Become knowledgeable in identifying an episode of bipolar depression and differentiating it from major depressive disorder, so as to provide effective treatment for bipolar depression. A

› Begin treatment of bipolar depression with one of the recommended first-line medications, especially lithium, lamotrigine, quetiapine, or lurasidone. A

› Treat bipolar II depression similar to the way bipolar I depression is treated: primarily, using a mood stabilizer alone or, occasionally, using a mood stabilizer plus an antidepressant. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series