User login

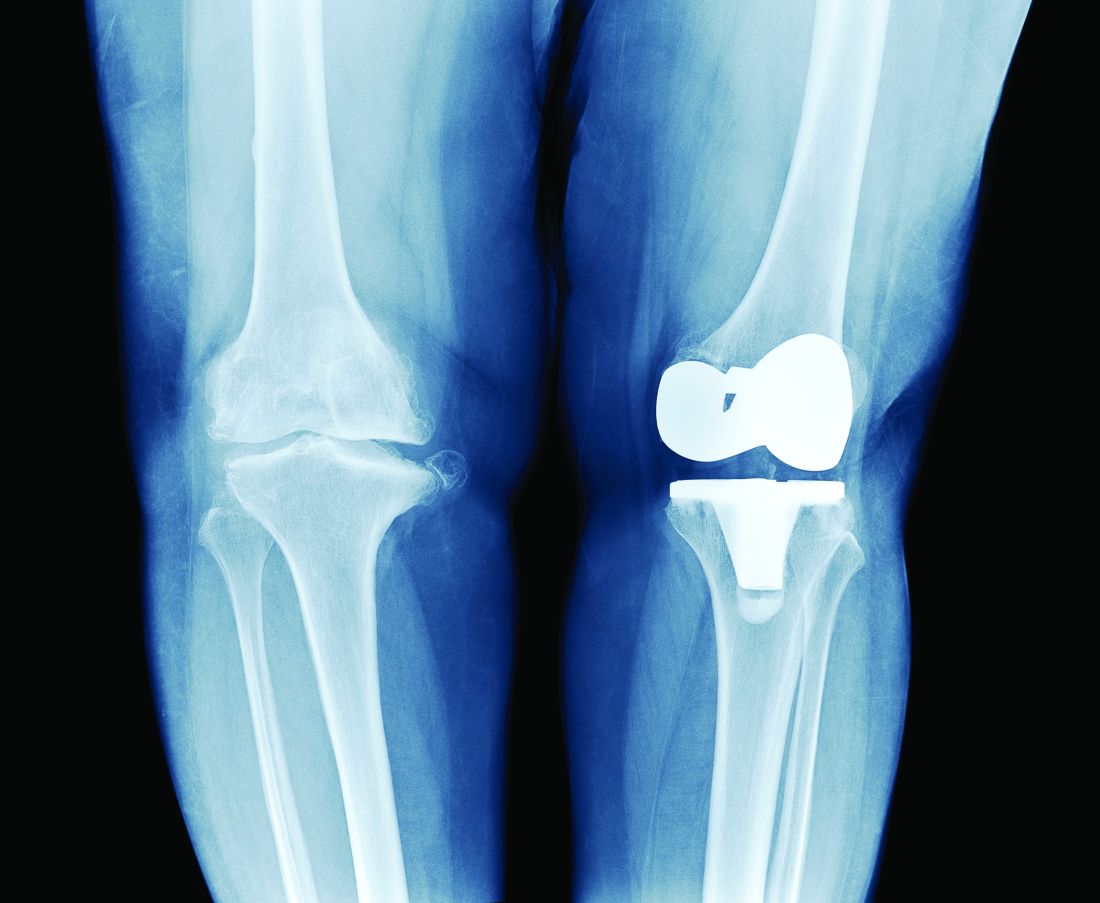

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A new study has found that physical therapy may lead to a reduced risk of long-term opioid use in patients who have undergone total knee replacement (TKR).

“Greater number of PT intervention sessions and earlier initiation of outpatient PT care after TKR were associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use,” authors from Boston University wrote in their report on the study, which was published online Oct. 27 in JAMA Network Open.

“In previous large studies, we’ve seen that physical therapy can reduce pain in people with knee osteoarthritis, which is usually the primary indication for TKR,” study coauthor Deepak Kumar, PT, PhD, said in an interview. “But the association of physical therapy with opioid use in people with knee replacement has not yet been explored.

“The reason we focused on opioid use in these patients is because the number of knee replacement surgeries is going up exponentially,” Dr. Kumar said. “And, depending on which data you look at, from one-third to up to half of people who undergo knee replacement and have used opioids before end up becoming long-term users. Even in people who have not used them before, 5%-8% become long-term users after the surgery.

“Given how many surgeries are happening – and that number is expected to keep going up – the number of people who are becoming long-term opioid users is not trivial,” he said.

Study details

To assess the value of PT in reducing opioid use in this subset of patients, the authors reviewed records from the OptumLabs Data Warehouse insurance claims database to identify 67,322 eligible participants aged 40 or older who underwent TKR from Jan. 1, 2001, to Dec. 31, 2016. Of those patients, 38,408 were opioid naive and 28,914 had taken opioids before. The authors evaluated long-term opioid use – defined as 90 days or more of filled prescriptions – during a 12-month outcome assessment period that varied depending on differences in post-TKR PT start date and duration.

The researchers found a significantly lower likelihood of long-term opioid use associated with receipt of any PT before TKR among patients who had not taken opioids before (adjusted odds ratio [aOR], 0.75; 95% confidence interval, 0.60-0.95) and those who had taken opioids in the past (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.80).

Investigators found that 2.2% of participants in the opioid-naive group and 32.5% of those in the opioid-experienced group used opioids long-term after TKR. Approximately 76% of participants overall received outpatient PT within the 90 days after surgery, and the receipt of post-TKR PT at any point was associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use in the opioid-experienced group (aOR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.70-0.79).

Among the opioid-experienced group, receiving between 6 and 12 PT sessions (aOR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.75-0.90) or ≥ 13 sessions (aOR, 0.71; 95% CI, 0.65-0.77) were both associated with lower odds of long-term opioid use, compared with those who received 1-5 sessions. Beginning PT 31-60 days or 61-90 days after surgery was associated with greater odds of long-term opioid use across both cohorts, compared with those who initiated therapy within 30 days of TKR.

Physical therapy: Underexplored option for pain in knee replacement

One finding caught the researchers slightly off guard: There was no association between active physical therapy and reduced odds of long-term opioid use. “From prior studies, at least in people with knee osteoarthritis, we know that active interventions were more useful than passive interventions,” Dr. Kumar said.

That said, he added that there is still some professional uncertainty regarding “the right type or the right components of physical therapy for managing pain in this population.” Regardless, he believes their study emphasizes the benefits of PT as a pain alleviator in these patients, especially those who have previously used opioids.

“Pharmaceuticals have side effects. Injections are not super effective,” he said. “The idea behind focusing on physical therapy interventions is that it’s widely available, it does you no harm, and it could potentially be lower cost to both the payers and the providers.”

The authors acknowledged their study’s limitations, including not adjusting for opioid use within the 90 days after surgery as well as the different outcome assessment periods for pre-TKR and post-TKR PT exposures. In addition, they admitted that some of the patients who received PT could have been among those less likely to be treated with opioids, and vice versa. “A randomized clinical trial,” they wrote, “would be required to disentangle these issues.”

The study was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. Dr. Kumar reported receiving grants from the National Institutes of Health during the conduct of the study and grants from Pfizer for unrelated projects outside the submitted work. The full list of author disclosures can be found with the original article.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.