User login

For MD-IQ on Family Practice News, but a regular topic for Rheumatology News

Sports Injuries of the Hip in Primary Care

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, how are you feeling about sports injuries?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I’m feeling great, Matt.

Watto: You had a sports injury of the hip. Maybe that’s an overshare, Paul, but we talked about it on a podcast with Dr Carlin Senter (part 1 and part 2).

Williams: I think I’ve shared more than my hip injury, for sure.

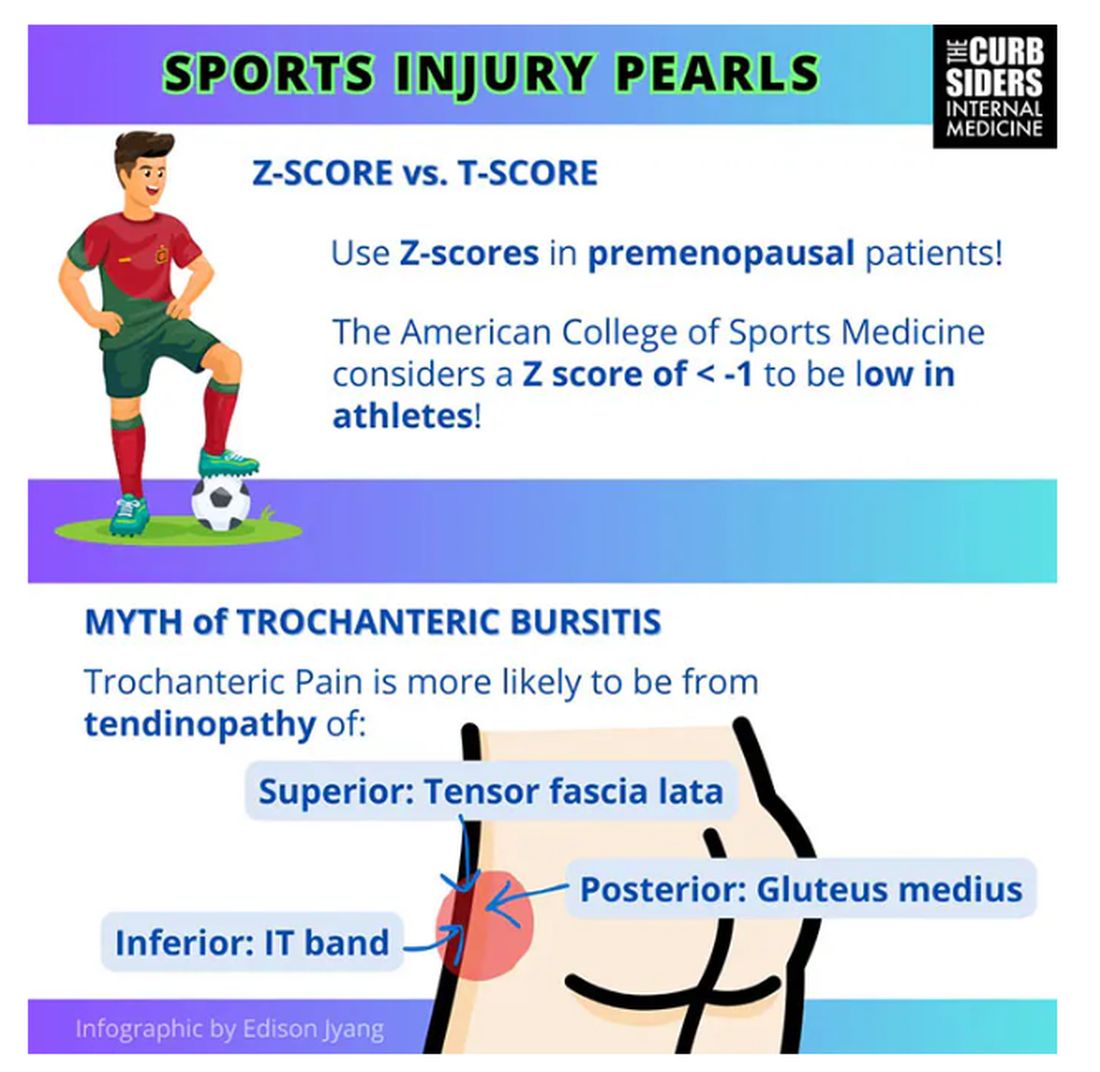

Watto: Whenever a patient presented with hip pain, I used to pray it was trochanteric bursitis, which now I know is not really the right thing to think about. Intra-articular hip pain presents as anterior hip pain, usually in the crease of the hip. Depending on the patient’s age and history, the differential for that type of pain includes iliopsoas tendonitis, FAI syndrome, a labral tear, a bone stress injury of the femoral neck, or osteoarthritis.

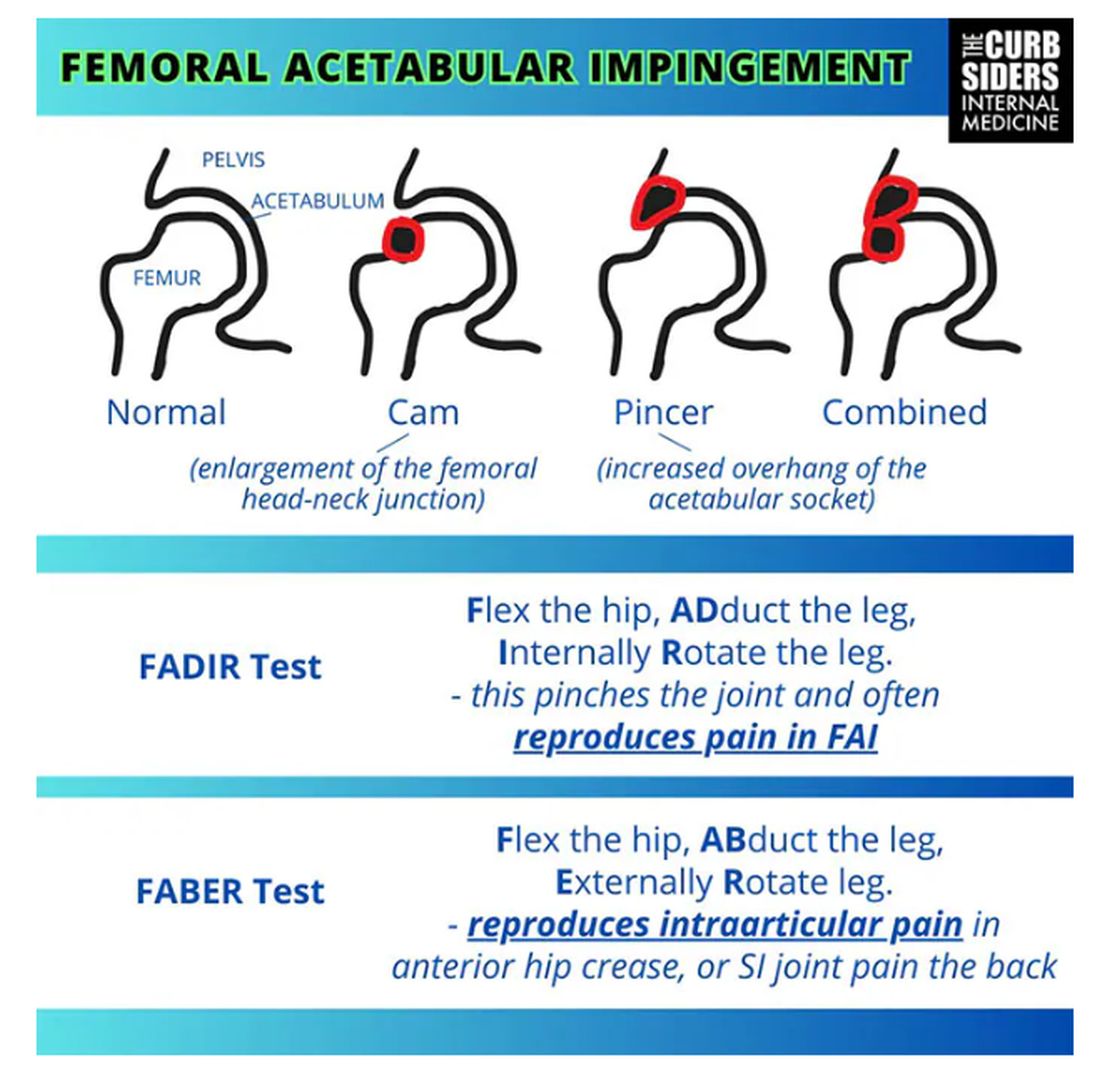

So, what exactly is FAI and how might we diagnose it?

Williams: FAI is what the cool kids call femoral acetabular impingement, and it’s exactly what it sounds like.

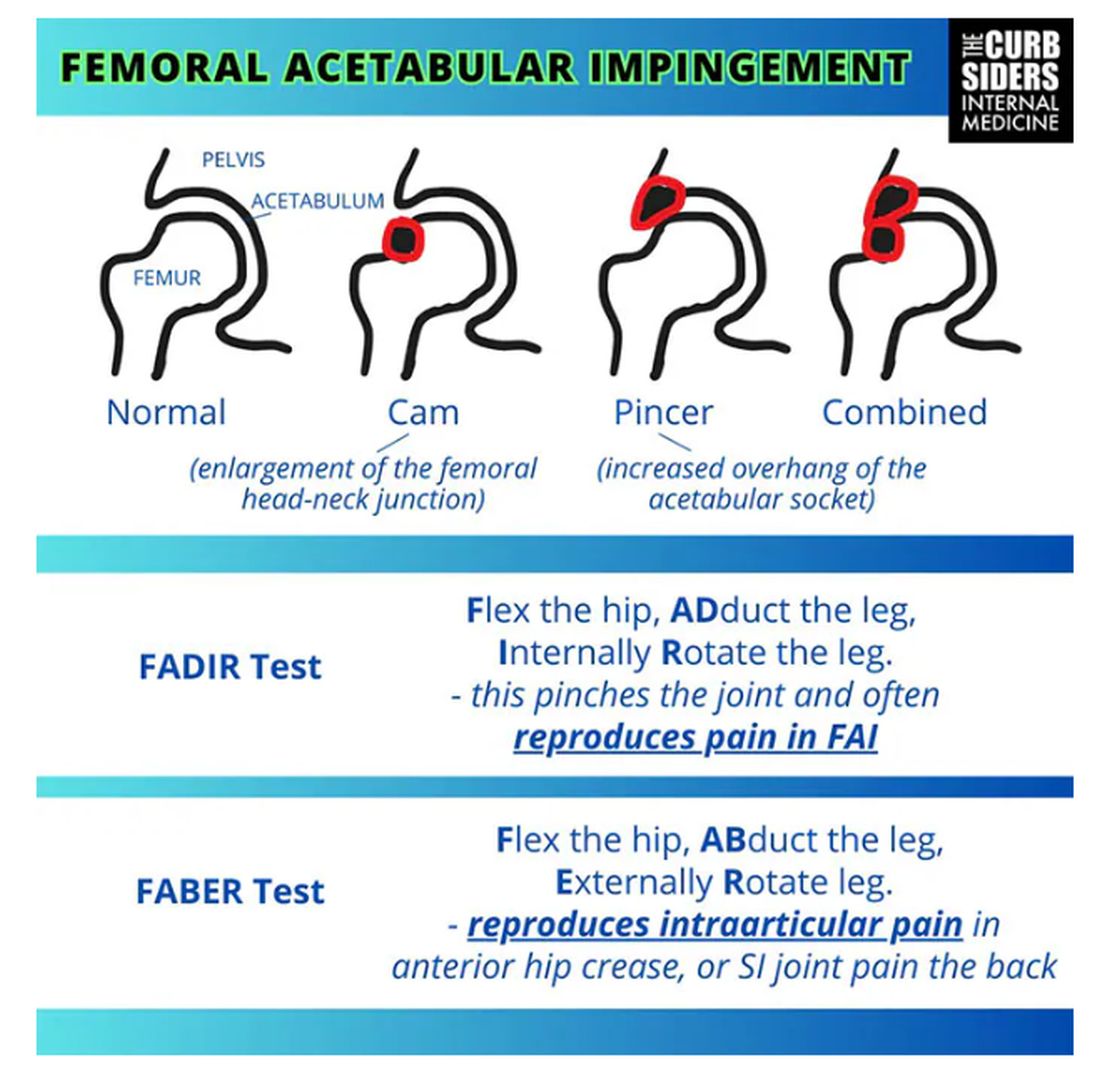

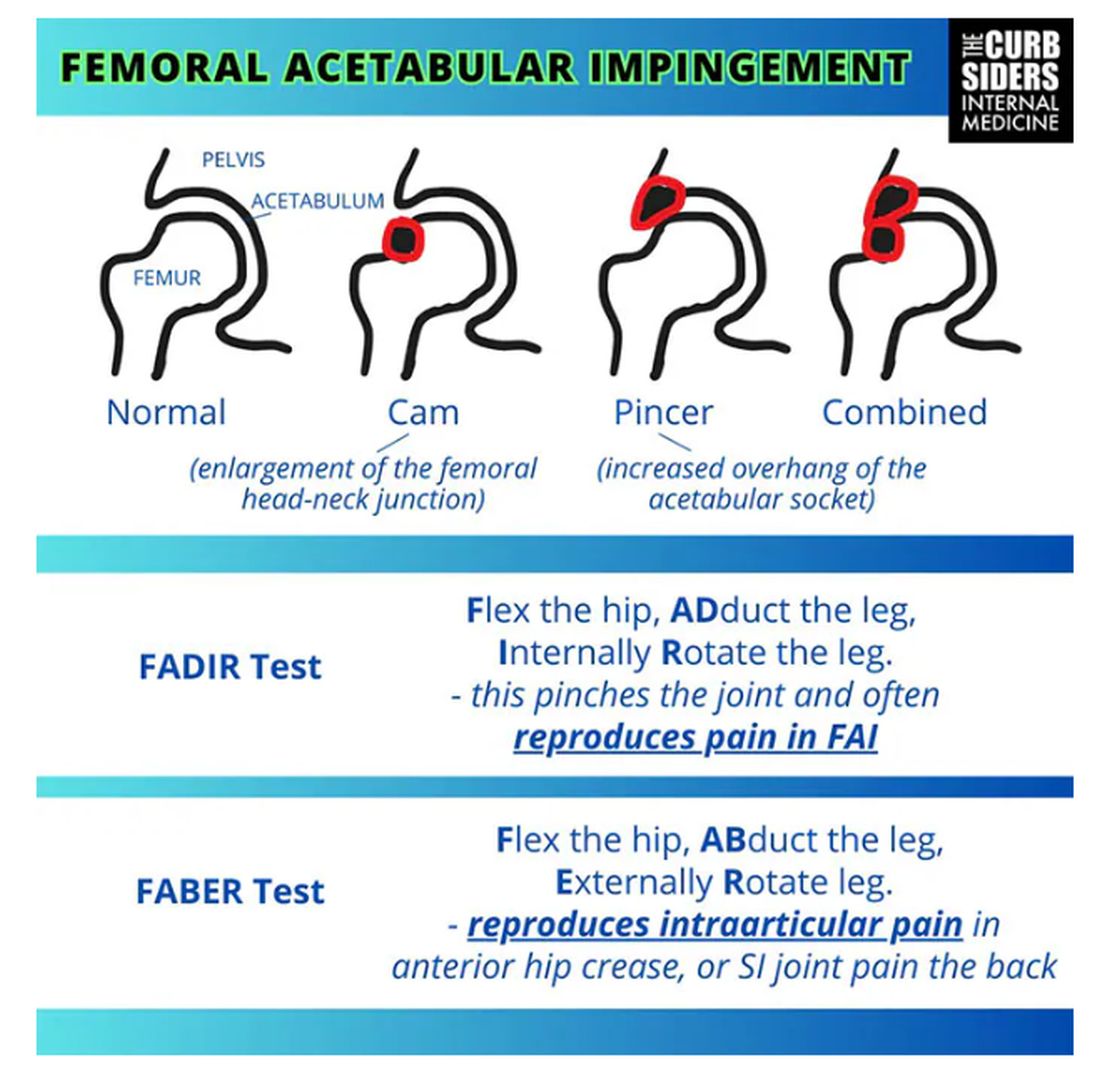

Something is pinching or impinging upon the joint itself and preventing full range of motion. This is a ball-and-socket joint, so it should have tremendous range of motion, able to move in all planes. If it’s impinged, then pain will occur with certain movements. There’s a cam type, which is characterized by enlargement of the femoral head neck junction, or a pincer type, which has more to do with overhang of the acetabulum, and it can also be mixed. In any case, impingement upon the patient’s full range of motion results in pain.

You evaluate this with a couple of tests — the FABER and the FADIR.

The FABER is flexion, abduction, and external rotation, and the FADIR is flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. If you elicit anterior pain with either of those tests, it’s probably one of the intra-articular pathologies, although it is hard to know for sure which one it is because these tests are fairly sensitive but not very specific.

Watto: You can get x-rays to help with the diagnosis. You would order two views of the hip: an AP of the pelvis, which is just a straight-on shot to look for arthritis or fracture. Is there a healthy joint line there? The second is the Dunn view, in which the hip is flexed 90 degrees and abducted about 20 degrees. You are looking for fracture or impingement. You can diagnose FAI based on that view, and you might be able to diagnose a hip stress injury or osteoarthritis.

Unfortunately, you’re not going to see a labral tear, but Dr Senter said that both FAI and labral tears are treated the same way, with physical therapy. Patients with FAI who aren’t getting better might end up going for surgery, so at some point I would refer them to orthopedic surgery. But I feel much more comfortable now diagnosing these conditions with these tests.

Let’s talk a little bit about trochanteric pain syndrome. I used to think it was all bursitis. Why is that not correct?

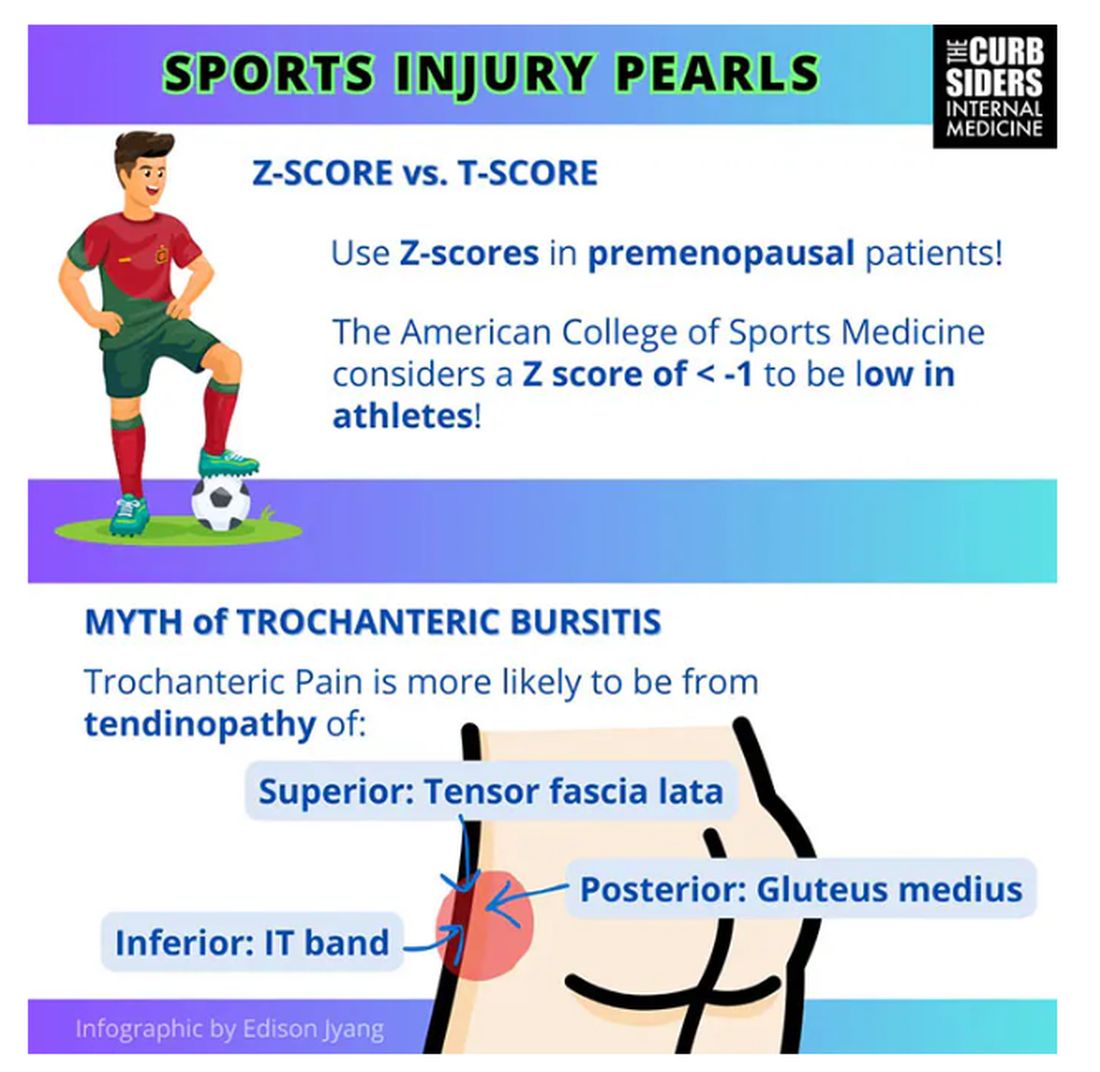

Williams: It’s nice of you to feign ignorance for the purpose of education. It used to be thought of as bursitis, but these days we know it is probably more likely a tendinopathy.

Trochanteric pain syndrome was formerly known as trochanteric bursitis, but the bursa is not typically involved. Trochanteric pain syndrome is a tendinopathy of the surrounding structures: the gluteus medius, the iliotibial band, and the tensor fascia latae. The way these structures relate looks a bit like the face of a clock, as you can see on the infographic. In general, you manage this condition the same way you do with bursitis — physical therapy. You can also give corticosteroid injections. Physical therapy is probably more durable in terms of pain relief and functionality, but in the short term, corticosteroids might provide some degree of analgesia as well.

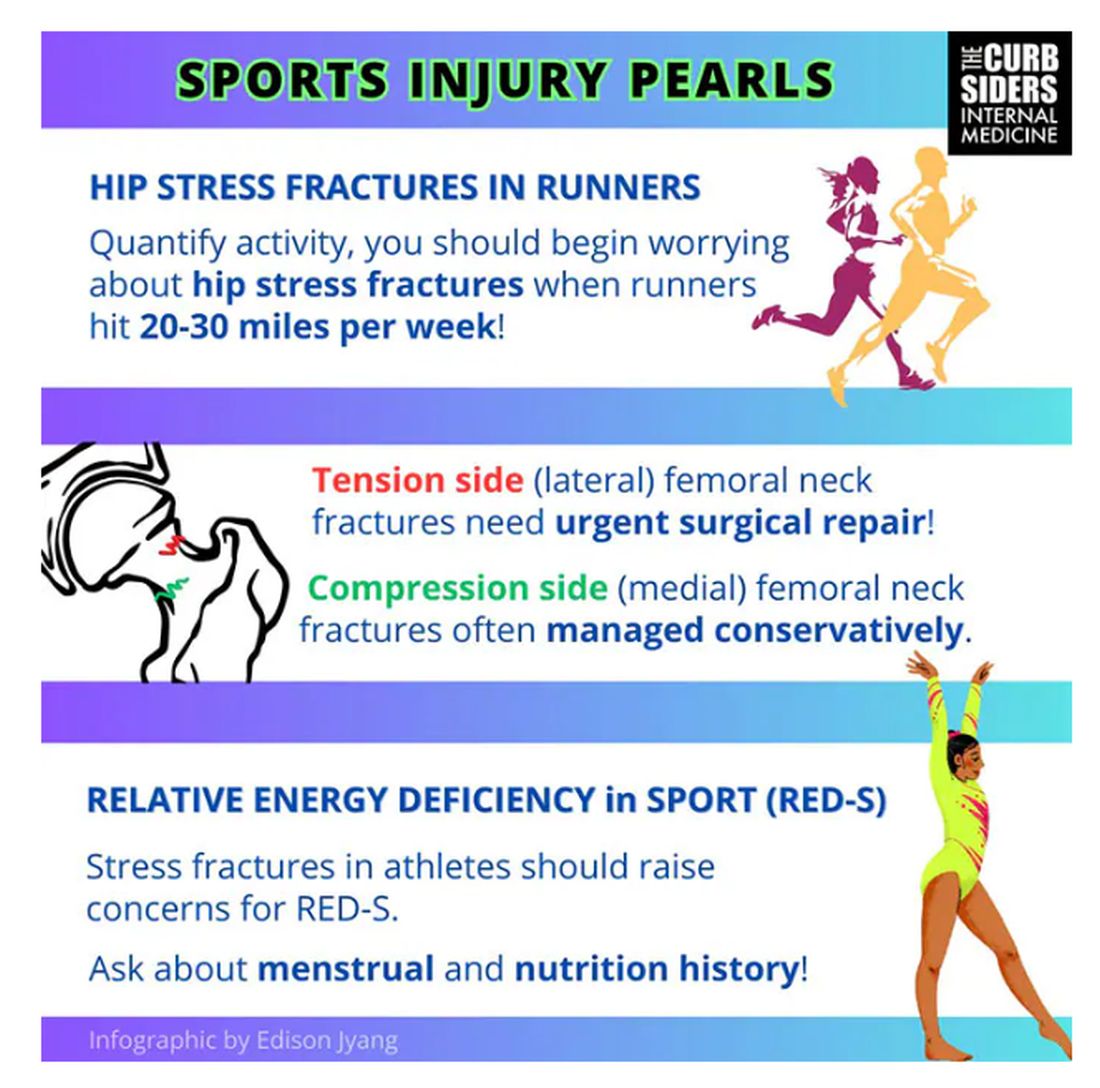

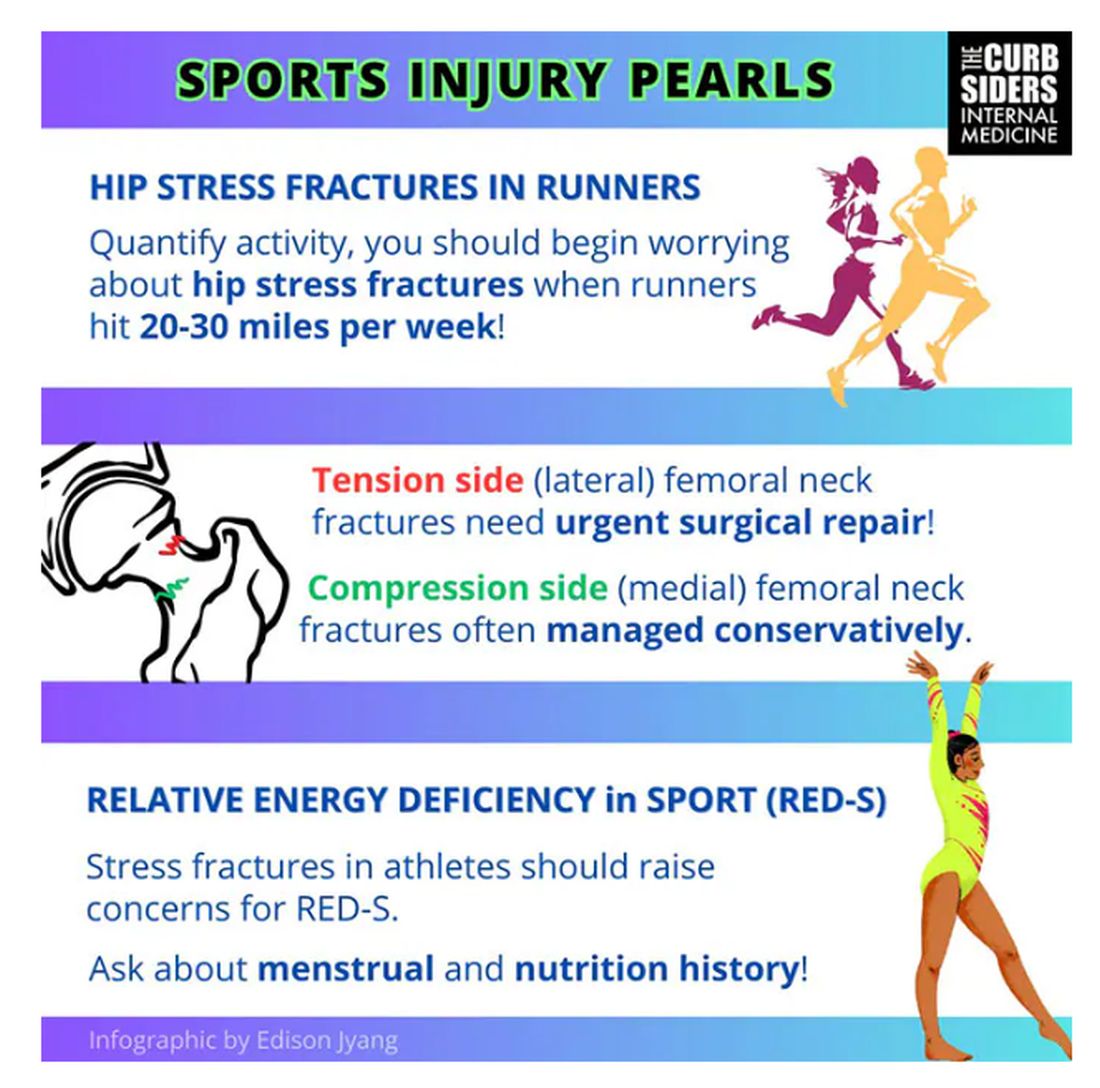

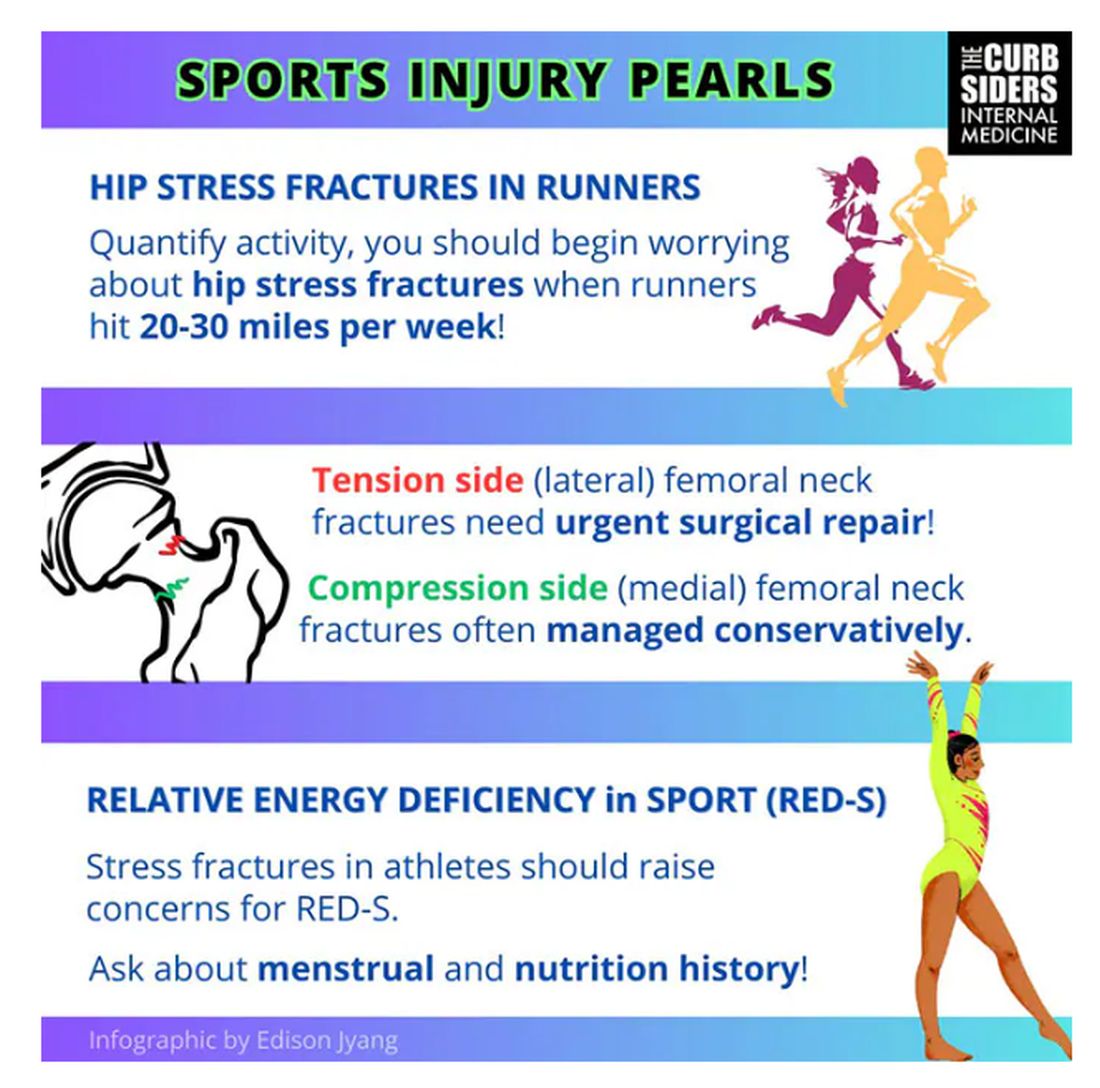

Watto: The last thing we wanted to mention is bone stress injury, which can occur in high-mileage runners (20 miles or more per week). Patients with bone stress injury need to rest, usually non‒weight bearing, for a period of time.

Treatment of a bone stress fracture depends on which side it’s on (top or bottom). If it’s on the top of the femoral neck (the tension side), it has to be fixed. If it’s on the compression side (the bottom side of the femoral neck), it might be able to be managed conservatively, but many patients are going to need surgery. This is a big deal. But it’s a spectrum; in some cases the bone is merely irritated and unhappy, without a break in the cortex. Those patients might not need surgery.

In patients with a fracture of the femoral neck — especially younger, healthier patients — you should think about getting a bone density test and screening for relative energy deficiency in sport. This used to be called the female athlete triad, which includes disrupted menstrual cycles, being underweight, and fracture. We should be screening patients, asking them in a nonjudgmental way about their relationship with food, to make sure they are getting an appropriate number of calories.

They are actually in an energy deficit. They’re not eating enough to maintain a healthy body with so much activity.

Williams: If you’re interested in this topic, you should refer to the full podcast with Dr Senter which is chock-full of helpful information.

Dr Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with The Curbsiders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, how are you feeling about sports injuries?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I’m feeling great, Matt.

Watto: You had a sports injury of the hip. Maybe that’s an overshare, Paul, but we talked about it on a podcast with Dr Carlin Senter (part 1 and part 2).

Williams: I think I’ve shared more than my hip injury, for sure.

Watto: Whenever a patient presented with hip pain, I used to pray it was trochanteric bursitis, which now I know is not really the right thing to think about. Intra-articular hip pain presents as anterior hip pain, usually in the crease of the hip. Depending on the patient’s age and history, the differential for that type of pain includes iliopsoas tendonitis, FAI syndrome, a labral tear, a bone stress injury of the femoral neck, or osteoarthritis.

So, what exactly is FAI and how might we diagnose it?

Williams: FAI is what the cool kids call femoral acetabular impingement, and it’s exactly what it sounds like.

Something is pinching or impinging upon the joint itself and preventing full range of motion. This is a ball-and-socket joint, so it should have tremendous range of motion, able to move in all planes. If it’s impinged, then pain will occur with certain movements. There’s a cam type, which is characterized by enlargement of the femoral head neck junction, or a pincer type, which has more to do with overhang of the acetabulum, and it can also be mixed. In any case, impingement upon the patient’s full range of motion results in pain.

You evaluate this with a couple of tests — the FABER and the FADIR.

The FABER is flexion, abduction, and external rotation, and the FADIR is flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. If you elicit anterior pain with either of those tests, it’s probably one of the intra-articular pathologies, although it is hard to know for sure which one it is because these tests are fairly sensitive but not very specific.

Watto: You can get x-rays to help with the diagnosis. You would order two views of the hip: an AP of the pelvis, which is just a straight-on shot to look for arthritis or fracture. Is there a healthy joint line there? The second is the Dunn view, in which the hip is flexed 90 degrees and abducted about 20 degrees. You are looking for fracture or impingement. You can diagnose FAI based on that view, and you might be able to diagnose a hip stress injury or osteoarthritis.

Unfortunately, you’re not going to see a labral tear, but Dr Senter said that both FAI and labral tears are treated the same way, with physical therapy. Patients with FAI who aren’t getting better might end up going for surgery, so at some point I would refer them to orthopedic surgery. But I feel much more comfortable now diagnosing these conditions with these tests.

Let’s talk a little bit about trochanteric pain syndrome. I used to think it was all bursitis. Why is that not correct?

Williams: It’s nice of you to feign ignorance for the purpose of education. It used to be thought of as bursitis, but these days we know it is probably more likely a tendinopathy.

Trochanteric pain syndrome was formerly known as trochanteric bursitis, but the bursa is not typically involved. Trochanteric pain syndrome is a tendinopathy of the surrounding structures: the gluteus medius, the iliotibial band, and the tensor fascia latae. The way these structures relate looks a bit like the face of a clock, as you can see on the infographic. In general, you manage this condition the same way you do with bursitis — physical therapy. You can also give corticosteroid injections. Physical therapy is probably more durable in terms of pain relief and functionality, but in the short term, corticosteroids might provide some degree of analgesia as well.

Watto: The last thing we wanted to mention is bone stress injury, which can occur in high-mileage runners (20 miles or more per week). Patients with bone stress injury need to rest, usually non‒weight bearing, for a period of time.

Treatment of a bone stress fracture depends on which side it’s on (top or bottom). If it’s on the top of the femoral neck (the tension side), it has to be fixed. If it’s on the compression side (the bottom side of the femoral neck), it might be able to be managed conservatively, but many patients are going to need surgery. This is a big deal. But it’s a spectrum; in some cases the bone is merely irritated and unhappy, without a break in the cortex. Those patients might not need surgery.

In patients with a fracture of the femoral neck — especially younger, healthier patients — you should think about getting a bone density test and screening for relative energy deficiency in sport. This used to be called the female athlete triad, which includes disrupted menstrual cycles, being underweight, and fracture. We should be screening patients, asking them in a nonjudgmental way about their relationship with food, to make sure they are getting an appropriate number of calories.

They are actually in an energy deficit. They’re not eating enough to maintain a healthy body with so much activity.

Williams: If you’re interested in this topic, you should refer to the full podcast with Dr Senter which is chock-full of helpful information.

Dr Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with The Curbsiders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript has been edited for clarity.

Matthew F. Watto, MD: Welcome back to The Curbsiders. I’m Dr Matthew Frank Watto, here with my great friend and America’s primary care physician, Dr Paul Nelson Williams. Paul, how are you feeling about sports injuries?

Paul N. Williams, MD: I’m feeling great, Matt.

Watto: You had a sports injury of the hip. Maybe that’s an overshare, Paul, but we talked about it on a podcast with Dr Carlin Senter (part 1 and part 2).

Williams: I think I’ve shared more than my hip injury, for sure.

Watto: Whenever a patient presented with hip pain, I used to pray it was trochanteric bursitis, which now I know is not really the right thing to think about. Intra-articular hip pain presents as anterior hip pain, usually in the crease of the hip. Depending on the patient’s age and history, the differential for that type of pain includes iliopsoas tendonitis, FAI syndrome, a labral tear, a bone stress injury of the femoral neck, or osteoarthritis.

So, what exactly is FAI and how might we diagnose it?

Williams: FAI is what the cool kids call femoral acetabular impingement, and it’s exactly what it sounds like.

Something is pinching or impinging upon the joint itself and preventing full range of motion. This is a ball-and-socket joint, so it should have tremendous range of motion, able to move in all planes. If it’s impinged, then pain will occur with certain movements. There’s a cam type, which is characterized by enlargement of the femoral head neck junction, or a pincer type, which has more to do with overhang of the acetabulum, and it can also be mixed. In any case, impingement upon the patient’s full range of motion results in pain.

You evaluate this with a couple of tests — the FABER and the FADIR.

The FABER is flexion, abduction, and external rotation, and the FADIR is flexion, adduction, and internal rotation. If you elicit anterior pain with either of those tests, it’s probably one of the intra-articular pathologies, although it is hard to know for sure which one it is because these tests are fairly sensitive but not very specific.

Watto: You can get x-rays to help with the diagnosis. You would order two views of the hip: an AP of the pelvis, which is just a straight-on shot to look for arthritis or fracture. Is there a healthy joint line there? The second is the Dunn view, in which the hip is flexed 90 degrees and abducted about 20 degrees. You are looking for fracture or impingement. You can diagnose FAI based on that view, and you might be able to diagnose a hip stress injury or osteoarthritis.

Unfortunately, you’re not going to see a labral tear, but Dr Senter said that both FAI and labral tears are treated the same way, with physical therapy. Patients with FAI who aren’t getting better might end up going for surgery, so at some point I would refer them to orthopedic surgery. But I feel much more comfortable now diagnosing these conditions with these tests.

Let’s talk a little bit about trochanteric pain syndrome. I used to think it was all bursitis. Why is that not correct?

Williams: It’s nice of you to feign ignorance for the purpose of education. It used to be thought of as bursitis, but these days we know it is probably more likely a tendinopathy.

Trochanteric pain syndrome was formerly known as trochanteric bursitis, but the bursa is not typically involved. Trochanteric pain syndrome is a tendinopathy of the surrounding structures: the gluteus medius, the iliotibial band, and the tensor fascia latae. The way these structures relate looks a bit like the face of a clock, as you can see on the infographic. In general, you manage this condition the same way you do with bursitis — physical therapy. You can also give corticosteroid injections. Physical therapy is probably more durable in terms of pain relief and functionality, but in the short term, corticosteroids might provide some degree of analgesia as well.

Watto: The last thing we wanted to mention is bone stress injury, which can occur in high-mileage runners (20 miles or more per week). Patients with bone stress injury need to rest, usually non‒weight bearing, for a period of time.

Treatment of a bone stress fracture depends on which side it’s on (top or bottom). If it’s on the top of the femoral neck (the tension side), it has to be fixed. If it’s on the compression side (the bottom side of the femoral neck), it might be able to be managed conservatively, but many patients are going to need surgery. This is a big deal. But it’s a spectrum; in some cases the bone is merely irritated and unhappy, without a break in the cortex. Those patients might not need surgery.

In patients with a fracture of the femoral neck — especially younger, healthier patients — you should think about getting a bone density test and screening for relative energy deficiency in sport. This used to be called the female athlete triad, which includes disrupted menstrual cycles, being underweight, and fracture. We should be screening patients, asking them in a nonjudgmental way about their relationship with food, to make sure they are getting an appropriate number of calories.

They are actually in an energy deficit. They’re not eating enough to maintain a healthy body with so much activity.

Williams: If you’re interested in this topic, you should refer to the full podcast with Dr Senter which is chock-full of helpful information.

Dr Watto, Clinical Assistant Professor, Department of Medicine, Perelman School of Medicine at University of Pennsylvania; Internist, Department of Medicine, Hospital Medicine Section, Pennsylvania Hospital, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, has disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr Williams, Associate Professor of Clinical Medicine, Department of General Internal Medicine, Lewis Katz School of Medicine; Staff Physician, Department of General Internal Medicine, Temple Internal Medicine Associates, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, disclosed ties with The Curbsiders.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

Using GLP-1s to Meet BMI Goal for Orthopedic Surgery

The woman, in severe pain from hip and knee osteoarthritis, was confined to a wheelchair and had been told that would likely be for life. To qualify for hip replacement surgery, she needed to lose 100 pounds, a seemingly impossible goal. But she wanted to try.

“We tried a couple of medicines — oral medicines off-label — topiramate, phentermine,” said Leslie Golden, MD, MPH, DABM, a family medicine physician and obesity medicine specialist in Watertown, Wisconsin, 42 miles northeast of Madison.

They weren’t enough. But then Golden turned to glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and they delivered.

“She did lose a significant amount of weight and was able to get the hip replacement,” said Golden.

It took a couple of years. However, seeing her walk into her office, rather than wheel in, “is still one of the joys of my practice,” Golden said. “She’s so grateful. She felt everyone else had written her off.”

As she told Golden: “If I fell and broke my leg today, they would take me to surgery without concern.”

Because her hip replacement was viewed as a nonemergency procedure, the accepted threshold for elective safe surgery was a body mass index (BMI) < 40. That BMI cutoff can vary from provider to provider and medical facility to medical facility but is often required for other surgeries as well, including kidney and lung transplants, gender-affirming surgery, bariatric surgery, hernia surgery, and in vitro fertilization procedures.

She worked with Rajit Chakravarty, MD, an adult reconstructive surgeon who practices in Watertown and nearby Madison, to oversee the weight loss.

High BMIs & Surgery Issues

High BMIs have long been linked with postsurgery complications, poor wound healing, and other issues, although some research now is questioning some of those associations. Even so, surgeons have long stressed weight loss for their patients with obesity before orthopedic and other procedures.

These days, surgeons are more likely to need to have that talk. In the last decade, the age-adjusted prevalence of severe obesity — a BMI of ≥ 40 — has increased from 7.7% to 9.7% of US adults. The number of joint replacements is also rising — more than 700,000 total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and more than 450,000 total hip arthroplasty (THA), according to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. As the population ages, those numbers are expected to increase.

Making the GLP-1 Choice

GLP-1s aren’t the only choice, of course. But they’re often more effective, as Golden found, than other medications. And when his patients with obesity are offered bariatric surgery or GLP-1s, “people definitely want to avoid the bariatric surgery,” Chakravarty said.

With the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of semaglutide (Wegovy) in June 2021 for chronic weight management and then tirzepatide (Zepbound) in November 2023, interest has boomed, he said, among his surgery candidates with a high BMI.

The FDA approved Wegovy based on clinical trials, including one in which participants lost an average of 12.4% of initial body weight compared with those on placebo. It approved Zepbound based on clinical trials, including one in which those on Zepbound lost an average of 18% of their body weight, compared with those on placebo.

The wheelchair-bound woman, now 65, began with a BMI of 63, Golden said. She negotiated a cutoff of 45 with the surgeon and got the go-ahead. Currently, her BMI is 36 as she stayed on the medications.

Beyond the benefit of GLP-1s helping patients meet the BMI cutoff, some research finds fewer postoperative infections and readmissions with their use. This study found the medications did lower both, and another found reduced readmissions and complications.

Growing Partnerships, Increasing Success

Helping patients lose weight isn’t just about lowering the BMI, Chakravarty pointed out. The aim is to improve nutritional health — to teach patients how to eat healthfully for their needs, in turn improving other health barometers. Referring them to an obesity medicine physician helps to meet those goals.

When Daniel Wiznia, MD, a Yale Medicine orthopedic surgeon and codirector of the Avascular Necrosis Program, has a patient who must delay a TKA or THA until they meet a BMI cutoff, he refers that patient to the Yale Medicine Center for Weight Management, New Haven, Connecticut, to learn about weight loss, including the options of anti-obesity medications or bariatric surgery.

Taking the GLP-1s can be a game changer, according to Wiznia and John Morton, MD, MPH, FACS, FASMBS, Yale’s medical director of Bariatric Surgery and professor and vice chair of surgery, who is a physician-director of the center. The program includes other options, such as bariatric surgery, and emphasizes diet and other lifestyle measures. GLP-1s give about a 15% weight loss, Morton said, compared with bariatric surgery providing up to 30%.

Sarah Stombaugh, MD, a family medicine and obesity medicine physician in Charlottesville, Virginia, often gets referrals from two orthopedic surgeons in her community. One recent patient in her early 60s had a BMI of 43.2, too high to qualify for the TKA she needed. On GLP-1s, the initial goal was to decrease a weight of 244 to 225, bringing the BMI to 39.9. The woman did that, then kept losing before her surgery was scheduled, getting to a weight of 210 or a BMI of 37 and staying there for 3 months before the surgery.

She had the TKA, and 5 months out, she is doing well, Stombaugh said. “We do medical weight loss primarily with the GLP-1s because they’re simply the best, the most effective,” Stombaugh said. She does occasionally use oral medications such as naltrexone/bupropion (Contrave).

Stombaugh sees the collaborating trend as still evolving. When she attends obesity medicine conferences, not all her colleagues report they are partnering with surgeons. But she predicts the practice will increase, saying the popularization of what she terms the more effective GLP-1 medications Wegovy and Zepbound is driving it. Partnering with the surgeon requires a conversation at the beginning, when the referral is made, about goals. After that, she sees her patient monthly and sends progress notes to the surgeon.

Golden collaborates with three orthopedic groups in her area, primarily for knee and hip surgeries, but has also helped patients meet the BMI cutoff before spine-related surgeries. She is helping a lung transplant patient now. She has seen several patients who must meet BMI requirements before starting in vitro fertilization, due to the need for conscious sedation for egg retrieval. She has had a few patients who had to meet a BMI cutoff for nonemergency hernia repair.

Insurance Issues

Insurance remains an issue for the pricey medications. “Only about a third of patients are routinely covered with insurance,” Morton said.

However, it’s improving, he said. Golden also finds about a third of private payers cover the medication but tries to use manufacturers’ coupons to help defray the costs (from about $1000 or $1400 to about $500 a month). She has sometimes gotten enough samples to get patients to their BMI goal

Morton consulted for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Olympus, Teleflex, and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The woman, in severe pain from hip and knee osteoarthritis, was confined to a wheelchair and had been told that would likely be for life. To qualify for hip replacement surgery, she needed to lose 100 pounds, a seemingly impossible goal. But she wanted to try.

“We tried a couple of medicines — oral medicines off-label — topiramate, phentermine,” said Leslie Golden, MD, MPH, DABM, a family medicine physician and obesity medicine specialist in Watertown, Wisconsin, 42 miles northeast of Madison.

They weren’t enough. But then Golden turned to glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and they delivered.

“She did lose a significant amount of weight and was able to get the hip replacement,” said Golden.

It took a couple of years. However, seeing her walk into her office, rather than wheel in, “is still one of the joys of my practice,” Golden said. “She’s so grateful. She felt everyone else had written her off.”

As she told Golden: “If I fell and broke my leg today, they would take me to surgery without concern.”

Because her hip replacement was viewed as a nonemergency procedure, the accepted threshold for elective safe surgery was a body mass index (BMI) < 40. That BMI cutoff can vary from provider to provider and medical facility to medical facility but is often required for other surgeries as well, including kidney and lung transplants, gender-affirming surgery, bariatric surgery, hernia surgery, and in vitro fertilization procedures.

She worked with Rajit Chakravarty, MD, an adult reconstructive surgeon who practices in Watertown and nearby Madison, to oversee the weight loss.

High BMIs & Surgery Issues

High BMIs have long been linked with postsurgery complications, poor wound healing, and other issues, although some research now is questioning some of those associations. Even so, surgeons have long stressed weight loss for their patients with obesity before orthopedic and other procedures.

These days, surgeons are more likely to need to have that talk. In the last decade, the age-adjusted prevalence of severe obesity — a BMI of ≥ 40 — has increased from 7.7% to 9.7% of US adults. The number of joint replacements is also rising — more than 700,000 total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and more than 450,000 total hip arthroplasty (THA), according to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. As the population ages, those numbers are expected to increase.

Making the GLP-1 Choice

GLP-1s aren’t the only choice, of course. But they’re often more effective, as Golden found, than other medications. And when his patients with obesity are offered bariatric surgery or GLP-1s, “people definitely want to avoid the bariatric surgery,” Chakravarty said.

With the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of semaglutide (Wegovy) in June 2021 for chronic weight management and then tirzepatide (Zepbound) in November 2023, interest has boomed, he said, among his surgery candidates with a high BMI.

The FDA approved Wegovy based on clinical trials, including one in which participants lost an average of 12.4% of initial body weight compared with those on placebo. It approved Zepbound based on clinical trials, including one in which those on Zepbound lost an average of 18% of their body weight, compared with those on placebo.

The wheelchair-bound woman, now 65, began with a BMI of 63, Golden said. She negotiated a cutoff of 45 with the surgeon and got the go-ahead. Currently, her BMI is 36 as she stayed on the medications.

Beyond the benefit of GLP-1s helping patients meet the BMI cutoff, some research finds fewer postoperative infections and readmissions with their use. This study found the medications did lower both, and another found reduced readmissions and complications.

Growing Partnerships, Increasing Success

Helping patients lose weight isn’t just about lowering the BMI, Chakravarty pointed out. The aim is to improve nutritional health — to teach patients how to eat healthfully for their needs, in turn improving other health barometers. Referring them to an obesity medicine physician helps to meet those goals.

When Daniel Wiznia, MD, a Yale Medicine orthopedic surgeon and codirector of the Avascular Necrosis Program, has a patient who must delay a TKA or THA until they meet a BMI cutoff, he refers that patient to the Yale Medicine Center for Weight Management, New Haven, Connecticut, to learn about weight loss, including the options of anti-obesity medications or bariatric surgery.

Taking the GLP-1s can be a game changer, according to Wiznia and John Morton, MD, MPH, FACS, FASMBS, Yale’s medical director of Bariatric Surgery and professor and vice chair of surgery, who is a physician-director of the center. The program includes other options, such as bariatric surgery, and emphasizes diet and other lifestyle measures. GLP-1s give about a 15% weight loss, Morton said, compared with bariatric surgery providing up to 30%.

Sarah Stombaugh, MD, a family medicine and obesity medicine physician in Charlottesville, Virginia, often gets referrals from two orthopedic surgeons in her community. One recent patient in her early 60s had a BMI of 43.2, too high to qualify for the TKA she needed. On GLP-1s, the initial goal was to decrease a weight of 244 to 225, bringing the BMI to 39.9. The woman did that, then kept losing before her surgery was scheduled, getting to a weight of 210 or a BMI of 37 and staying there for 3 months before the surgery.

She had the TKA, and 5 months out, she is doing well, Stombaugh said. “We do medical weight loss primarily with the GLP-1s because they’re simply the best, the most effective,” Stombaugh said. She does occasionally use oral medications such as naltrexone/bupropion (Contrave).

Stombaugh sees the collaborating trend as still evolving. When she attends obesity medicine conferences, not all her colleagues report they are partnering with surgeons. But she predicts the practice will increase, saying the popularization of what she terms the more effective GLP-1 medications Wegovy and Zepbound is driving it. Partnering with the surgeon requires a conversation at the beginning, when the referral is made, about goals. After that, she sees her patient monthly and sends progress notes to the surgeon.

Golden collaborates with three orthopedic groups in her area, primarily for knee and hip surgeries, but has also helped patients meet the BMI cutoff before spine-related surgeries. She is helping a lung transplant patient now. She has seen several patients who must meet BMI requirements before starting in vitro fertilization, due to the need for conscious sedation for egg retrieval. She has had a few patients who had to meet a BMI cutoff for nonemergency hernia repair.

Insurance Issues

Insurance remains an issue for the pricey medications. “Only about a third of patients are routinely covered with insurance,” Morton said.

However, it’s improving, he said. Golden also finds about a third of private payers cover the medication but tries to use manufacturers’ coupons to help defray the costs (from about $1000 or $1400 to about $500 a month). She has sometimes gotten enough samples to get patients to their BMI goal

Morton consulted for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Olympus, Teleflex, and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

The woman, in severe pain from hip and knee osteoarthritis, was confined to a wheelchair and had been told that would likely be for life. To qualify for hip replacement surgery, she needed to lose 100 pounds, a seemingly impossible goal. But she wanted to try.

“We tried a couple of medicines — oral medicines off-label — topiramate, phentermine,” said Leslie Golden, MD, MPH, DABM, a family medicine physician and obesity medicine specialist in Watertown, Wisconsin, 42 miles northeast of Madison.

They weren’t enough. But then Golden turned to glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists, and they delivered.

“She did lose a significant amount of weight and was able to get the hip replacement,” said Golden.

It took a couple of years. However, seeing her walk into her office, rather than wheel in, “is still one of the joys of my practice,” Golden said. “She’s so grateful. She felt everyone else had written her off.”

As she told Golden: “If I fell and broke my leg today, they would take me to surgery without concern.”

Because her hip replacement was viewed as a nonemergency procedure, the accepted threshold for elective safe surgery was a body mass index (BMI) < 40. That BMI cutoff can vary from provider to provider and medical facility to medical facility but is often required for other surgeries as well, including kidney and lung transplants, gender-affirming surgery, bariatric surgery, hernia surgery, and in vitro fertilization procedures.

She worked with Rajit Chakravarty, MD, an adult reconstructive surgeon who practices in Watertown and nearby Madison, to oversee the weight loss.

High BMIs & Surgery Issues

High BMIs have long been linked with postsurgery complications, poor wound healing, and other issues, although some research now is questioning some of those associations. Even so, surgeons have long stressed weight loss for their patients with obesity before orthopedic and other procedures.

These days, surgeons are more likely to need to have that talk. In the last decade, the age-adjusted prevalence of severe obesity — a BMI of ≥ 40 — has increased from 7.7% to 9.7% of US adults. The number of joint replacements is also rising — more than 700,000 total knee arthroplasty (TKA) and more than 450,000 total hip arthroplasty (THA), according to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. As the population ages, those numbers are expected to increase.

Making the GLP-1 Choice

GLP-1s aren’t the only choice, of course. But they’re often more effective, as Golden found, than other medications. And when his patients with obesity are offered bariatric surgery or GLP-1s, “people definitely want to avoid the bariatric surgery,” Chakravarty said.

With the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval of semaglutide (Wegovy) in June 2021 for chronic weight management and then tirzepatide (Zepbound) in November 2023, interest has boomed, he said, among his surgery candidates with a high BMI.

The FDA approved Wegovy based on clinical trials, including one in which participants lost an average of 12.4% of initial body weight compared with those on placebo. It approved Zepbound based on clinical trials, including one in which those on Zepbound lost an average of 18% of their body weight, compared with those on placebo.

The wheelchair-bound woman, now 65, began with a BMI of 63, Golden said. She negotiated a cutoff of 45 with the surgeon and got the go-ahead. Currently, her BMI is 36 as she stayed on the medications.

Beyond the benefit of GLP-1s helping patients meet the BMI cutoff, some research finds fewer postoperative infections and readmissions with their use. This study found the medications did lower both, and another found reduced readmissions and complications.

Growing Partnerships, Increasing Success

Helping patients lose weight isn’t just about lowering the BMI, Chakravarty pointed out. The aim is to improve nutritional health — to teach patients how to eat healthfully for their needs, in turn improving other health barometers. Referring them to an obesity medicine physician helps to meet those goals.

When Daniel Wiznia, MD, a Yale Medicine orthopedic surgeon and codirector of the Avascular Necrosis Program, has a patient who must delay a TKA or THA until they meet a BMI cutoff, he refers that patient to the Yale Medicine Center for Weight Management, New Haven, Connecticut, to learn about weight loss, including the options of anti-obesity medications or bariatric surgery.

Taking the GLP-1s can be a game changer, according to Wiznia and John Morton, MD, MPH, FACS, FASMBS, Yale’s medical director of Bariatric Surgery and professor and vice chair of surgery, who is a physician-director of the center. The program includes other options, such as bariatric surgery, and emphasizes diet and other lifestyle measures. GLP-1s give about a 15% weight loss, Morton said, compared with bariatric surgery providing up to 30%.

Sarah Stombaugh, MD, a family medicine and obesity medicine physician in Charlottesville, Virginia, often gets referrals from two orthopedic surgeons in her community. One recent patient in her early 60s had a BMI of 43.2, too high to qualify for the TKA she needed. On GLP-1s, the initial goal was to decrease a weight of 244 to 225, bringing the BMI to 39.9. The woman did that, then kept losing before her surgery was scheduled, getting to a weight of 210 or a BMI of 37 and staying there for 3 months before the surgery.

She had the TKA, and 5 months out, she is doing well, Stombaugh said. “We do medical weight loss primarily with the GLP-1s because they’re simply the best, the most effective,” Stombaugh said. She does occasionally use oral medications such as naltrexone/bupropion (Contrave).

Stombaugh sees the collaborating trend as still evolving. When she attends obesity medicine conferences, not all her colleagues report they are partnering with surgeons. But she predicts the practice will increase, saying the popularization of what she terms the more effective GLP-1 medications Wegovy and Zepbound is driving it. Partnering with the surgeon requires a conversation at the beginning, when the referral is made, about goals. After that, she sees her patient monthly and sends progress notes to the surgeon.

Golden collaborates with three orthopedic groups in her area, primarily for knee and hip surgeries, but has also helped patients meet the BMI cutoff before spine-related surgeries. She is helping a lung transplant patient now. She has seen several patients who must meet BMI requirements before starting in vitro fertilization, due to the need for conscious sedation for egg retrieval. She has had a few patients who had to meet a BMI cutoff for nonemergency hernia repair.

Insurance Issues

Insurance remains an issue for the pricey medications. “Only about a third of patients are routinely covered with insurance,” Morton said.

However, it’s improving, he said. Golden also finds about a third of private payers cover the medication but tries to use manufacturers’ coupons to help defray the costs (from about $1000 or $1400 to about $500 a month). She has sometimes gotten enough samples to get patients to their BMI goal

Morton consulted for Novo Nordisk, Eli Lilly, Olympus, Teleflex, and Johnson & Johnson.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

New Test’s Utility in Distinguishing OA From Inflammatory Arthritis Questioned

A new diagnostic test can accurately distinguish osteoarthritis (OA) from inflammatory arthritis using two synovial fluid biomarkers, according to research published in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research on December 18, 2024.

However, experts question whether such a test would be useful.

“The need would seem to be fairly limited, mostly those with single joint involvement and a lack of other systemic features to specify a diagnosis, which is not that common, at least in rheumatology, where there are usually features in the history and physical that can clarify the diagnosis,” said Amanda E. Nelson, MD, MSCR, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She was not involved with the research.

The test uses an algorithm that incorporates concentrations of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) and interleukin 8 (IL-8) in synovial fluid. The researchers hypothesized that a ratio of the two biomarkers could distinguish between primary OA and other inflammatory arthritic diagnoses.

“Primary OA is unlikely when either COMP concentration or COMP/IL‐8 ratio in the synovial fluid is low since these conditions indicate either lack of cartilage degradation or presence of high inflammation,” wrote Daniel Keter and coauthors at CD Diagnostics, Claymont, Delaware, and CD Laboratories, Towson, Maryland. “In contrast, a high COMP concentration result in combination with high COMP/IL‐8 ratio would be suggestive of low inflammation in the setting of cartilage deterioration, which is indicative of primary OA.”

In patients with OA, synovial fluid can be difficult to aspirate in sufficient amounts for testing, Nelson said.

“If synovial fluid is present and able to be aspirated, it is unclear if this test has any benefit over a simple, standard cell count and crystal assessment, which can also distinguish between osteoarthritis and more inflammatory arthritides,” she said.

Differentiating OA

To test this potential diagnostic algorithm, researchers obtained 171 knee synovial fluid samples from approved clinical remnant sample sources and a biovendor. All samples were annotated with an existing arthritic diagnosis, including 54 with primary OA, 57 with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 30 with crystal arthritis (CA), and 30 with native septic arthritis (NSA).

Researchers assigned a CA diagnosis based on the presence of monosodium urate or calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystals in the synovial fluid, and NSA was determined via the Synovasure Alpha Defensin test. OA was confirmed via radiograph as Kellgren‐Lawrence grades 2‐4 with no other arthritic diagnoses. RA samples were purchased via a biovendor, and researchers were not provided with diagnosis‐confirming data.

All samples were randomized and blinded before testing, and researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests for both COMP and IL-8 biomarkers.

Of the 54 OA samples, 47 tested positive for OA using the COMP + COMP/IL-8 ratio algorithm. Of the 117 samples with inflammatory arthritis, 13 tested positive for OA. Overall, the diagnostic algorithm demonstrated a clinical sensitivity of 87.0% and specificity of 88.9%. The positive predictive value was 78.3%, while the negative predictive value was 93.7%.

Unclear Clinical Need

Nelson noted that while this test aims to differentiate between arthritic diagnoses, patients can also have multiple conditions.

“Many individuals with rheumatoid arthritis will develop osteoarthritis, but they can have both, so a yes/no test is of unclear utility,” she said. OA and calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease can often occur together, “but the driver is really the OA, and the CPPD is present but not actively inflammatory,” she continued. “Septic arthritis should be readily distinguishable by cell count alone [and again, can coexist with any of the other conditions], and a thorough history and physical should be able to differentiate in most cases.”

While these results from this study are “reasonably impressive,” more clinical information is needed to interpret these results, added C. Kent Kwoh, MD, director of the University of Arizona Arthritis Center and professor of medicine and medical imaging at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, Arizona.

Because the study is retrospective in nature and researchers obtained specimens from different sources, it was not clear if these patients were being treated when these samples were taken and if their various conditions were controlled or flaring.

“I would say this is a reasonable first step,” Kwoh said. “We would need prospective studies, more clinical characterization, and potentially longitudinal studies to understand when this test may be useful.”

This research was internally funded by Zimmer Biomet. All authors were employees of CD Diagnostics or CD Laboratories, both of which are subsidiaries of Zimmer Biomet. Kwoh reported receiving grants or contracts with AbbVie, Artiva, Eli Lilly and Company, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cumberland, Pfizer, GSK, and Galapagos, and consulting fees from TrialSpark/Formation Bio, Express Scripts, GSK, TLC BioSciences, and AposHealth. He participates on Data Safety Monitoring or Advisory Boards of Moebius Medical, Sun Pharma, Novartis, Xalud, and Kolon TissueGene. Nelson reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A new diagnostic test can accurately distinguish osteoarthritis (OA) from inflammatory arthritis using two synovial fluid biomarkers, according to research published in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research on December 18, 2024.

However, experts question whether such a test would be useful.

“The need would seem to be fairly limited, mostly those with single joint involvement and a lack of other systemic features to specify a diagnosis, which is not that common, at least in rheumatology, where there are usually features in the history and physical that can clarify the diagnosis,” said Amanda E. Nelson, MD, MSCR, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She was not involved with the research.

The test uses an algorithm that incorporates concentrations of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) and interleukin 8 (IL-8) in synovial fluid. The researchers hypothesized that a ratio of the two biomarkers could distinguish between primary OA and other inflammatory arthritic diagnoses.

“Primary OA is unlikely when either COMP concentration or COMP/IL‐8 ratio in the synovial fluid is low since these conditions indicate either lack of cartilage degradation or presence of high inflammation,” wrote Daniel Keter and coauthors at CD Diagnostics, Claymont, Delaware, and CD Laboratories, Towson, Maryland. “In contrast, a high COMP concentration result in combination with high COMP/IL‐8 ratio would be suggestive of low inflammation in the setting of cartilage deterioration, which is indicative of primary OA.”

In patients with OA, synovial fluid can be difficult to aspirate in sufficient amounts for testing, Nelson said.

“If synovial fluid is present and able to be aspirated, it is unclear if this test has any benefit over a simple, standard cell count and crystal assessment, which can also distinguish between osteoarthritis and more inflammatory arthritides,” she said.

Differentiating OA

To test this potential diagnostic algorithm, researchers obtained 171 knee synovial fluid samples from approved clinical remnant sample sources and a biovendor. All samples were annotated with an existing arthritic diagnosis, including 54 with primary OA, 57 with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 30 with crystal arthritis (CA), and 30 with native septic arthritis (NSA).

Researchers assigned a CA diagnosis based on the presence of monosodium urate or calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystals in the synovial fluid, and NSA was determined via the Synovasure Alpha Defensin test. OA was confirmed via radiograph as Kellgren‐Lawrence grades 2‐4 with no other arthritic diagnoses. RA samples were purchased via a biovendor, and researchers were not provided with diagnosis‐confirming data.

All samples were randomized and blinded before testing, and researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests for both COMP and IL-8 biomarkers.

Of the 54 OA samples, 47 tested positive for OA using the COMP + COMP/IL-8 ratio algorithm. Of the 117 samples with inflammatory arthritis, 13 tested positive for OA. Overall, the diagnostic algorithm demonstrated a clinical sensitivity of 87.0% and specificity of 88.9%. The positive predictive value was 78.3%, while the negative predictive value was 93.7%.

Unclear Clinical Need

Nelson noted that while this test aims to differentiate between arthritic diagnoses, patients can also have multiple conditions.

“Many individuals with rheumatoid arthritis will develop osteoarthritis, but they can have both, so a yes/no test is of unclear utility,” she said. OA and calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease can often occur together, “but the driver is really the OA, and the CPPD is present but not actively inflammatory,” she continued. “Septic arthritis should be readily distinguishable by cell count alone [and again, can coexist with any of the other conditions], and a thorough history and physical should be able to differentiate in most cases.”

While these results from this study are “reasonably impressive,” more clinical information is needed to interpret these results, added C. Kent Kwoh, MD, director of the University of Arizona Arthritis Center and professor of medicine and medical imaging at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, Arizona.

Because the study is retrospective in nature and researchers obtained specimens from different sources, it was not clear if these patients were being treated when these samples were taken and if their various conditions were controlled or flaring.

“I would say this is a reasonable first step,” Kwoh said. “We would need prospective studies, more clinical characterization, and potentially longitudinal studies to understand when this test may be useful.”

This research was internally funded by Zimmer Biomet. All authors were employees of CD Diagnostics or CD Laboratories, both of which are subsidiaries of Zimmer Biomet. Kwoh reported receiving grants or contracts with AbbVie, Artiva, Eli Lilly and Company, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cumberland, Pfizer, GSK, and Galapagos, and consulting fees from TrialSpark/Formation Bio, Express Scripts, GSK, TLC BioSciences, and AposHealth. He participates on Data Safety Monitoring or Advisory Boards of Moebius Medical, Sun Pharma, Novartis, Xalud, and Kolon TissueGene. Nelson reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

A new diagnostic test can accurately distinguish osteoarthritis (OA) from inflammatory arthritis using two synovial fluid biomarkers, according to research published in the Journal of Orthopaedic Research on December 18, 2024.

However, experts question whether such a test would be useful.

“The need would seem to be fairly limited, mostly those with single joint involvement and a lack of other systemic features to specify a diagnosis, which is not that common, at least in rheumatology, where there are usually features in the history and physical that can clarify the diagnosis,” said Amanda E. Nelson, MD, MSCR, professor of medicine in the Division of Rheumatology, Allergy, and Immunology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She was not involved with the research.

The test uses an algorithm that incorporates concentrations of cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) and interleukin 8 (IL-8) in synovial fluid. The researchers hypothesized that a ratio of the two biomarkers could distinguish between primary OA and other inflammatory arthritic diagnoses.

“Primary OA is unlikely when either COMP concentration or COMP/IL‐8 ratio in the synovial fluid is low since these conditions indicate either lack of cartilage degradation or presence of high inflammation,” wrote Daniel Keter and coauthors at CD Diagnostics, Claymont, Delaware, and CD Laboratories, Towson, Maryland. “In contrast, a high COMP concentration result in combination with high COMP/IL‐8 ratio would be suggestive of low inflammation in the setting of cartilage deterioration, which is indicative of primary OA.”

In patients with OA, synovial fluid can be difficult to aspirate in sufficient amounts for testing, Nelson said.

“If synovial fluid is present and able to be aspirated, it is unclear if this test has any benefit over a simple, standard cell count and crystal assessment, which can also distinguish between osteoarthritis and more inflammatory arthritides,” she said.

Differentiating OA

To test this potential diagnostic algorithm, researchers obtained 171 knee synovial fluid samples from approved clinical remnant sample sources and a biovendor. All samples were annotated with an existing arthritic diagnosis, including 54 with primary OA, 57 with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), 30 with crystal arthritis (CA), and 30 with native septic arthritis (NSA).

Researchers assigned a CA diagnosis based on the presence of monosodium urate or calcium pyrophosphate dehydrate crystals in the synovial fluid, and NSA was determined via the Synovasure Alpha Defensin test. OA was confirmed via radiograph as Kellgren‐Lawrence grades 2‐4 with no other arthritic diagnoses. RA samples were purchased via a biovendor, and researchers were not provided with diagnosis‐confirming data.

All samples were randomized and blinded before testing, and researchers used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay tests for both COMP and IL-8 biomarkers.

Of the 54 OA samples, 47 tested positive for OA using the COMP + COMP/IL-8 ratio algorithm. Of the 117 samples with inflammatory arthritis, 13 tested positive for OA. Overall, the diagnostic algorithm demonstrated a clinical sensitivity of 87.0% and specificity of 88.9%. The positive predictive value was 78.3%, while the negative predictive value was 93.7%.

Unclear Clinical Need

Nelson noted that while this test aims to differentiate between arthritic diagnoses, patients can also have multiple conditions.

“Many individuals with rheumatoid arthritis will develop osteoarthritis, but they can have both, so a yes/no test is of unclear utility,” she said. OA and calcium pyrophosphate deposition (CPPD) disease can often occur together, “but the driver is really the OA, and the CPPD is present but not actively inflammatory,” she continued. “Septic arthritis should be readily distinguishable by cell count alone [and again, can coexist with any of the other conditions], and a thorough history and physical should be able to differentiate in most cases.”

While these results from this study are “reasonably impressive,” more clinical information is needed to interpret these results, added C. Kent Kwoh, MD, director of the University of Arizona Arthritis Center and professor of medicine and medical imaging at the University of Arizona College of Medicine, Tucson, Arizona.

Because the study is retrospective in nature and researchers obtained specimens from different sources, it was not clear if these patients were being treated when these samples were taken and if their various conditions were controlled or flaring.

“I would say this is a reasonable first step,” Kwoh said. “We would need prospective studies, more clinical characterization, and potentially longitudinal studies to understand when this test may be useful.”

This research was internally funded by Zimmer Biomet. All authors were employees of CD Diagnostics or CD Laboratories, both of which are subsidiaries of Zimmer Biomet. Kwoh reported receiving grants or contracts with AbbVie, Artiva, Eli Lilly and Company, Bristol Myers Squibb, Cumberland, Pfizer, GSK, and Galapagos, and consulting fees from TrialSpark/Formation Bio, Express Scripts, GSK, TLC BioSciences, and AposHealth. He participates on Data Safety Monitoring or Advisory Boards of Moebius Medical, Sun Pharma, Novartis, Xalud, and Kolon TissueGene. Nelson reported no relevant disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM JOURNAL OF ORTHOPAEDIC RESEARCH

Drugs Targeting Osteoarthritis Pain: What’s in Development?

WASHINGTON — Investigational treatments aimed specifically at reducing pain in knee osteoarthritis (OA) are moving forward in parallel with disease-modifying approaches.

“We still have very few treatments for the pain of osteoarthritis…It worries me that people think the only way forward is structure modification. I think while we’re waiting for some drugs to be structure modifying, we still need more pain relief. About 70% of people can’t tolerate or shouldn’t be on a [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug], and that leaves a large number of people with pain,” Philip Conaghan, MBBS, PhD, Chair of Musculoskeletal Medicine at the University of Leeds in England, said in an interview.

At the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Conaghan, who is also honorary consultant rheumatologist for the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, presented new data for two novel approaches, both targeting peripheral nociceptive pain signaling.

In a late-breaking poster, he presented phase 2 trial data on RTX-GRT7039 (resiniferatoxin [RTX]), an agonist of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 that is a driver of OA pain. The trial investigated the efficacy and safety of a single intra-articular injection of RTX-GRT7039 in people with knee OA.

And separately, in a late-breaking oral abstract session, Conaghan presented phase 2 trial safety and efficacy data for another investigational agent called LEVI-04, a first-in-class neurotrophin receptor fusion protein (p75NTR-Fc) that supplements the endogenous protein and provides analgesia via inhibition of NT-3 activity.

“I think both have potential to provide good pain relief, through slightly different mechanisms,” Conaghan said in an interview.

Asked to comment, session moderator Gregory C. Gardner, MD, emeritus professor in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview: “I think the results are really exciting terms of the ability to control pain to a significant degree in patients with osteoarthritis.”

However, Gardner also said, “The molecules can be very expensive ... so who do we give them to? Will insurance companies pay for this simply for OA pain? They improve function ... so clearly, [they] will be a boon to treating osteoarthritis, but do we give them to people with only more advanced forms of osteoarthritis or earlier on?”

Moreover, Gardner said, “One of my concerns about treating osteoarthritis is I don’t want to do too good of a job treating pain in somebody who has a biomechanically abnormal joint. ... You’ve got a knee that’s worn out some of the cartilage, and now you feel like you can go out and play soccer again. That’s not a good thing. That joint will wear out very quickly, even though it doesn’t feel pain.”

Another OA expert, Matlock Jeffries, MD, director of the Arthritis Research Unit at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, said in an interview, “I think we don’t focus nearly enough on pain, and that’s [partly] because the [Food and Drug Administration] has defined endpoints for knee OA trials that are radiographic. ... Patients do not care what their joint space narrowing is. They care what their pain is. And joint space changes and pain do not correlate in knee OA. ... About 20% or 30% of patients who have completely normal x-rays have a lot of pain…I hope that we’ll have some new OA pain therapeutics in the future because that’s what patients actually care about.”

But Jeffries noted that it will be very important to ensure that these agents don’t produce significant side effects, as had been seen previously in several large industry-sponsored trials of drugs targeting nerve growth factors.

“The big concern that we have in the field ... is that the nerve growth factor antibody trials were all stopped because there was a low but persistent risk of rapidly progressive OA in a small percent of patients. I think one of the questions in the field is whether targeting other things having to do with OA pain is going to result in similar bad outcomes. I think the answer is probably not, but that’s one thing that people do worry about, and they never really figured out why the [rapidly progressive OA] was happening.”

‘Potential to Provide Meaningful and Sustained Analgesia’

The phase 2 trial of RTX-GRT7039, funded by manufacturer Grünenthal, enrolled 40 patients with a baseline visual analog pain score (VAS) of > 40 mm on motion for average joint pain in the target knee over the past 2 days with or without analgesic medication and Kellgren-Lawrence grades 2-4.

They were randomized to receive a single intra-articular injection of 2 mg or 4 mg RTX-GRT7039 within 1 minute after receiving 5 mL ropivacaine (0.5%) or 4 mg or 8 mg RTX-GRT7039 administered 15 minutes after 5 mL ropivacaine pretreatment, or equivalent placebo treatments plus ropivacaine.

Plasma samples were collected for up to 2 hours, and VAS pain scores were collected for up to 3 hours post injection.

Reductions in VAS scores from baseline in the treated knee were seen in all RTX treatment groups as early as day 8 post injection and were maintained up to 6 months, while no reductions in VAS pain on motion scores were seen in the placebo group.

At 3 months, the absolute baseline-adjusted reductions in VAS scores were similar for RTX 2 mg (–39.75), RTX 4 mg (–40.20), and RTX 8 mg (–30.25), while the reduction in the placebo group was just –8.50. At 6 months, the mean absolute reduction in VAS score was numerically greater in the RTX 2-mg (–46.49), RTX 4-mg (–43.40), and RTX 8-mg (–38.60) groups vs the group that received RTX 4 mg within 1 minute after receiving ropivacaine (–22.00).

At both 3 and 6 months, a higher proportion of patients receiving any dose of RTX-GRT7039 achieved ≥ 50% and ≥ 70% reduction in pain on motion, compared with those who received placebo. All RTX-GRT7039 treatment groups reported a greater improvement in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) total score than the placebo group at both 3 and 6 months.

Rates of treatment-emergent adverse events were similar between the RTX groups (85.7%-90.9%) and placebo (85.7%) and slightly lower in the group that received RTX 4 mg within 1 minute of receiving ropivacaine (60.0%).

There was a trend toward greater procedural/injection site pain in the RTX treatment groups, compared with placebo, most commonly arthralgia (37.5%), headache (17.5%), and back pain (10%). This tended to peak around 0.5 hours post injection and resolve by 1.5-3.0 hours.

No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred, and no treatment-emergent adverse events led to discontinuation or death.

“This early-phase trial indicates that RTX-GRT7039 has the potential to provide meaningful and sustained analgesia for patients with knee OA pain,” Conaghan and colleagues wrote in their poster.

The drug is now being evaluated in three phase 3 trials (NCT05248386, NCT05449132, and NCT05377489).

LEVI-04: Modulation of NT-3 Appears to Work Safely

LEVI-04 was evaluated in a phase 2, 20-week, 13-center (Europe and Hong Kong) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 518 people with knee OA who had WOMAC pain subscale scores ≥ 20, mean average daily pain numeric rating scale score of 4-9, and radiographic Kellgren-Lawrence grade ≥ 2.

They were randomized to a total of five infusions of placebo or 0.3 mg/kg, 0.1 mg/kg, or 2 mg/kg LEVI-04 from baseline through week 16, with safety follow-up to week 30.

The primary endpoint, change in WOMAC pain from baseline to weeks 5 and 17, was met for all three doses. At 17 weeks, those were –2.79, –2.89, and –3.08 for 0.3 mg, 1.0 mg, and 2 mg, respectively, vs –2.28 for placebo (all P < .05).

Secondary endpoints, including WOMAC physical function, WOMAC stiffness, and Patient Global Assessment, and > 50% pain responders, were also all met at weeks 5 and 17. More than 50% of the LEVI-04–treated patients reported ≥ 50% reduction in pain, and > 25% reported ≥ 75% reduction at weeks 5 and 17.

“So, this modulation of NT-3 is working,” Conaghan commented.

There were no increased incidences of severe adverse events, treatment-emergent adverse events, or joint pathologies, including rapidly progressive OA, compared with placebo.

There were more paresthesias reported with the active drug, 2-4 vs 1 with placebo. “That says to me that the drug is working and that it’s having an effect on peripheral nerves, but luckily these were all mild or moderate and didn’t lead to any study withdrawal or discontinuation,” Conaghan said.

Phase 3 trials are in the planning stages, he noted.

Other Approaches to Treating OA Pain

Other approaches to treating OA pain have included methotrexate, for which Conaghan was also a coauthor on one paper that came out earlier in 2024. “This presumably works by treating inflammation, but it’s not clear if that is within-joint inflammation or systemic inflammation,” he said in an interview.

Another approach, using the weight loss drug semaglutide, was presented in April 2024 at the 2024 World Congress on Osteoarthritis annual meeting and published in October 2024 in The New England Journal of Medicine

The trial involving RTX-GRT7039 was funded by Grünenthal, and some study coauthors are employees of the company. The trial involving LEVI-04 was funded by Levicept, and some study coauthors are employees of the company. Conaghan is a consultant and/or speaker for Eli Lilly, Eupraxia Pharmaceuticals, Formation Bio, Galapagos, Genascence, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kolon TissueGene, Levicept, Medipost, Moebius, Novartis, Pacira, Sandoz, Stryker Corporation, and Takeda. Gardner and Jeffries had no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON — Investigational treatments aimed specifically at reducing pain in knee osteoarthritis (OA) are moving forward in parallel with disease-modifying approaches.

“We still have very few treatments for the pain of osteoarthritis…It worries me that people think the only way forward is structure modification. I think while we’re waiting for some drugs to be structure modifying, we still need more pain relief. About 70% of people can’t tolerate or shouldn’t be on a [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug], and that leaves a large number of people with pain,” Philip Conaghan, MBBS, PhD, Chair of Musculoskeletal Medicine at the University of Leeds in England, said in an interview.

At the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Conaghan, who is also honorary consultant rheumatologist for the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, presented new data for two novel approaches, both targeting peripheral nociceptive pain signaling.

In a late-breaking poster, he presented phase 2 trial data on RTX-GRT7039 (resiniferatoxin [RTX]), an agonist of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 that is a driver of OA pain. The trial investigated the efficacy and safety of a single intra-articular injection of RTX-GRT7039 in people with knee OA.

And separately, in a late-breaking oral abstract session, Conaghan presented phase 2 trial safety and efficacy data for another investigational agent called LEVI-04, a first-in-class neurotrophin receptor fusion protein (p75NTR-Fc) that supplements the endogenous protein and provides analgesia via inhibition of NT-3 activity.

“I think both have potential to provide good pain relief, through slightly different mechanisms,” Conaghan said in an interview.

Asked to comment, session moderator Gregory C. Gardner, MD, emeritus professor in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview: “I think the results are really exciting terms of the ability to control pain to a significant degree in patients with osteoarthritis.”

However, Gardner also said, “The molecules can be very expensive ... so who do we give them to? Will insurance companies pay for this simply for OA pain? They improve function ... so clearly, [they] will be a boon to treating osteoarthritis, but do we give them to people with only more advanced forms of osteoarthritis or earlier on?”

Moreover, Gardner said, “One of my concerns about treating osteoarthritis is I don’t want to do too good of a job treating pain in somebody who has a biomechanically abnormal joint. ... You’ve got a knee that’s worn out some of the cartilage, and now you feel like you can go out and play soccer again. That’s not a good thing. That joint will wear out very quickly, even though it doesn’t feel pain.”

Another OA expert, Matlock Jeffries, MD, director of the Arthritis Research Unit at the Oklahoma Medical Research Foundation, Oklahoma City, said in an interview, “I think we don’t focus nearly enough on pain, and that’s [partly] because the [Food and Drug Administration] has defined endpoints for knee OA trials that are radiographic. ... Patients do not care what their joint space narrowing is. They care what their pain is. And joint space changes and pain do not correlate in knee OA. ... About 20% or 30% of patients who have completely normal x-rays have a lot of pain…I hope that we’ll have some new OA pain therapeutics in the future because that’s what patients actually care about.”

But Jeffries noted that it will be very important to ensure that these agents don’t produce significant side effects, as had been seen previously in several large industry-sponsored trials of drugs targeting nerve growth factors.

“The big concern that we have in the field ... is that the nerve growth factor antibody trials were all stopped because there was a low but persistent risk of rapidly progressive OA in a small percent of patients. I think one of the questions in the field is whether targeting other things having to do with OA pain is going to result in similar bad outcomes. I think the answer is probably not, but that’s one thing that people do worry about, and they never really figured out why the [rapidly progressive OA] was happening.”

‘Potential to Provide Meaningful and Sustained Analgesia’

The phase 2 trial of RTX-GRT7039, funded by manufacturer Grünenthal, enrolled 40 patients with a baseline visual analog pain score (VAS) of > 40 mm on motion for average joint pain in the target knee over the past 2 days with or without analgesic medication and Kellgren-Lawrence grades 2-4.

They were randomized to receive a single intra-articular injection of 2 mg or 4 mg RTX-GRT7039 within 1 minute after receiving 5 mL ropivacaine (0.5%) or 4 mg or 8 mg RTX-GRT7039 administered 15 minutes after 5 mL ropivacaine pretreatment, or equivalent placebo treatments plus ropivacaine.

Plasma samples were collected for up to 2 hours, and VAS pain scores were collected for up to 3 hours post injection.

Reductions in VAS scores from baseline in the treated knee were seen in all RTX treatment groups as early as day 8 post injection and were maintained up to 6 months, while no reductions in VAS pain on motion scores were seen in the placebo group.

At 3 months, the absolute baseline-adjusted reductions in VAS scores were similar for RTX 2 mg (–39.75), RTX 4 mg (–40.20), and RTX 8 mg (–30.25), while the reduction in the placebo group was just –8.50. At 6 months, the mean absolute reduction in VAS score was numerically greater in the RTX 2-mg (–46.49), RTX 4-mg (–43.40), and RTX 8-mg (–38.60) groups vs the group that received RTX 4 mg within 1 minute after receiving ropivacaine (–22.00).

At both 3 and 6 months, a higher proportion of patients receiving any dose of RTX-GRT7039 achieved ≥ 50% and ≥ 70% reduction in pain on motion, compared with those who received placebo. All RTX-GRT7039 treatment groups reported a greater improvement in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) total score than the placebo group at both 3 and 6 months.

Rates of treatment-emergent adverse events were similar between the RTX groups (85.7%-90.9%) and placebo (85.7%) and slightly lower in the group that received RTX 4 mg within 1 minute of receiving ropivacaine (60.0%).

There was a trend toward greater procedural/injection site pain in the RTX treatment groups, compared with placebo, most commonly arthralgia (37.5%), headache (17.5%), and back pain (10%). This tended to peak around 0.5 hours post injection and resolve by 1.5-3.0 hours.

No treatment-related serious adverse events occurred, and no treatment-emergent adverse events led to discontinuation or death.

“This early-phase trial indicates that RTX-GRT7039 has the potential to provide meaningful and sustained analgesia for patients with knee OA pain,” Conaghan and colleagues wrote in their poster.

The drug is now being evaluated in three phase 3 trials (NCT05248386, NCT05449132, and NCT05377489).

LEVI-04: Modulation of NT-3 Appears to Work Safely

LEVI-04 was evaluated in a phase 2, 20-week, 13-center (Europe and Hong Kong) randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in 518 people with knee OA who had WOMAC pain subscale scores ≥ 20, mean average daily pain numeric rating scale score of 4-9, and radiographic Kellgren-Lawrence grade ≥ 2.

They were randomized to a total of five infusions of placebo or 0.3 mg/kg, 0.1 mg/kg, or 2 mg/kg LEVI-04 from baseline through week 16, with safety follow-up to week 30.

The primary endpoint, change in WOMAC pain from baseline to weeks 5 and 17, was met for all three doses. At 17 weeks, those were –2.79, –2.89, and –3.08 for 0.3 mg, 1.0 mg, and 2 mg, respectively, vs –2.28 for placebo (all P < .05).

Secondary endpoints, including WOMAC physical function, WOMAC stiffness, and Patient Global Assessment, and > 50% pain responders, were also all met at weeks 5 and 17. More than 50% of the LEVI-04–treated patients reported ≥ 50% reduction in pain, and > 25% reported ≥ 75% reduction at weeks 5 and 17.

“So, this modulation of NT-3 is working,” Conaghan commented.

There were no increased incidences of severe adverse events, treatment-emergent adverse events, or joint pathologies, including rapidly progressive OA, compared with placebo.

There were more paresthesias reported with the active drug, 2-4 vs 1 with placebo. “That says to me that the drug is working and that it’s having an effect on peripheral nerves, but luckily these were all mild or moderate and didn’t lead to any study withdrawal or discontinuation,” Conaghan said.

Phase 3 trials are in the planning stages, he noted.

Other Approaches to Treating OA Pain

Other approaches to treating OA pain have included methotrexate, for which Conaghan was also a coauthor on one paper that came out earlier in 2024. “This presumably works by treating inflammation, but it’s not clear if that is within-joint inflammation or systemic inflammation,” he said in an interview.

Another approach, using the weight loss drug semaglutide, was presented in April 2024 at the 2024 World Congress on Osteoarthritis annual meeting and published in October 2024 in The New England Journal of Medicine

The trial involving RTX-GRT7039 was funded by Grünenthal, and some study coauthors are employees of the company. The trial involving LEVI-04 was funded by Levicept, and some study coauthors are employees of the company. Conaghan is a consultant and/or speaker for Eli Lilly, Eupraxia Pharmaceuticals, Formation Bio, Galapagos, Genascence, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal, Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Kolon TissueGene, Levicept, Medipost, Moebius, Novartis, Pacira, Sandoz, Stryker Corporation, and Takeda. Gardner and Jeffries had no disclosures.

A version of this article appeared on Medscape.com.

WASHINGTON — Investigational treatments aimed specifically at reducing pain in knee osteoarthritis (OA) are moving forward in parallel with disease-modifying approaches.

“We still have very few treatments for the pain of osteoarthritis…It worries me that people think the only way forward is structure modification. I think while we’re waiting for some drugs to be structure modifying, we still need more pain relief. About 70% of people can’t tolerate or shouldn’t be on a [nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug], and that leaves a large number of people with pain,” Philip Conaghan, MBBS, PhD, Chair of Musculoskeletal Medicine at the University of Leeds in England, said in an interview.

At the annual meeting of the American College of Rheumatology, Conaghan, who is also honorary consultant rheumatologist for the Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust, presented new data for two novel approaches, both targeting peripheral nociceptive pain signaling.

In a late-breaking poster, he presented phase 2 trial data on RTX-GRT7039 (resiniferatoxin [RTX]), an agonist of the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 that is a driver of OA pain. The trial investigated the efficacy and safety of a single intra-articular injection of RTX-GRT7039 in people with knee OA.

And separately, in a late-breaking oral abstract session, Conaghan presented phase 2 trial safety and efficacy data for another investigational agent called LEVI-04, a first-in-class neurotrophin receptor fusion protein (p75NTR-Fc) that supplements the endogenous protein and provides analgesia via inhibition of NT-3 activity.

“I think both have potential to provide good pain relief, through slightly different mechanisms,” Conaghan said in an interview.

Asked to comment, session moderator Gregory C. Gardner, MD, emeritus professor in the Division of Rheumatology at the University of Washington, Seattle, said in an interview: “I think the results are really exciting terms of the ability to control pain to a significant degree in patients with osteoarthritis.”