User login

This transcript from Impact Factor has been edited for clarity.

If you are my age or older, and like me, you are something of a rule follower, then you’re getting screened for various cancers.

Colonoscopies, mammograms, cervical cancer screening, chest CTs for people with a significant smoking history. The tests are done and usually, but not always, they are negative. And if positive, usually, but not always, follow-up tests are negative, and if they aren’t and a new cancer is diagnosed you tell yourself, Well, at least we caught it early. Isn’t it good that I’m a rule follower? My life was just saved.

But it turns out, proving that cancer screening actually saves lives is quite difficult. Is it possible that all this screening is for nothing?

The benefits, risks, or perhaps futility of cancer screening is in the news this week because of this article, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

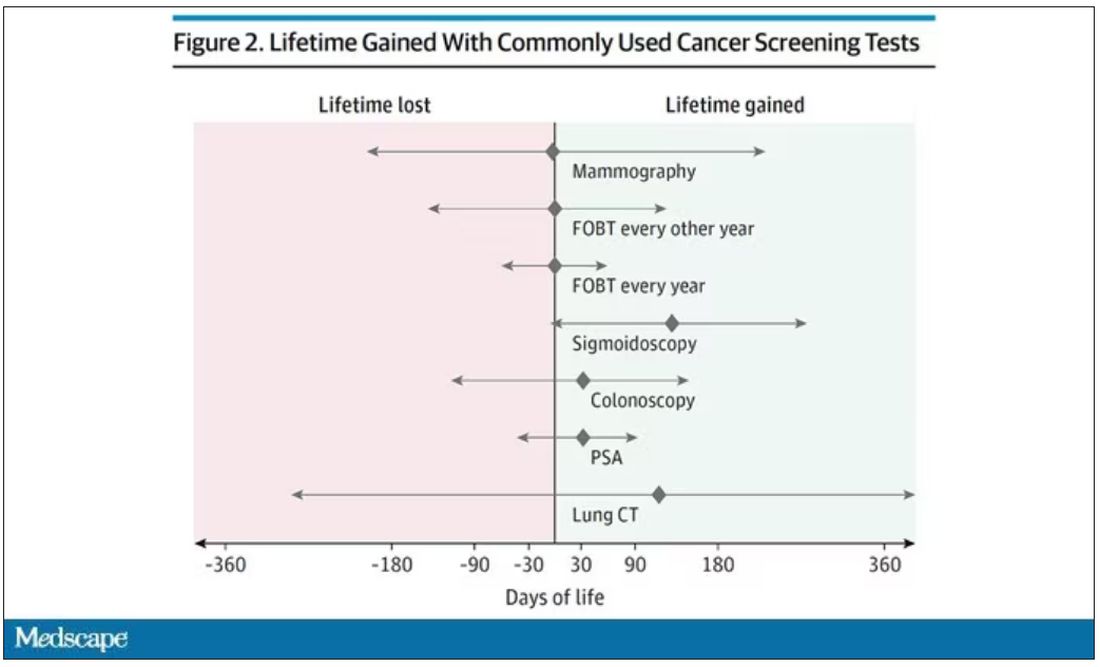

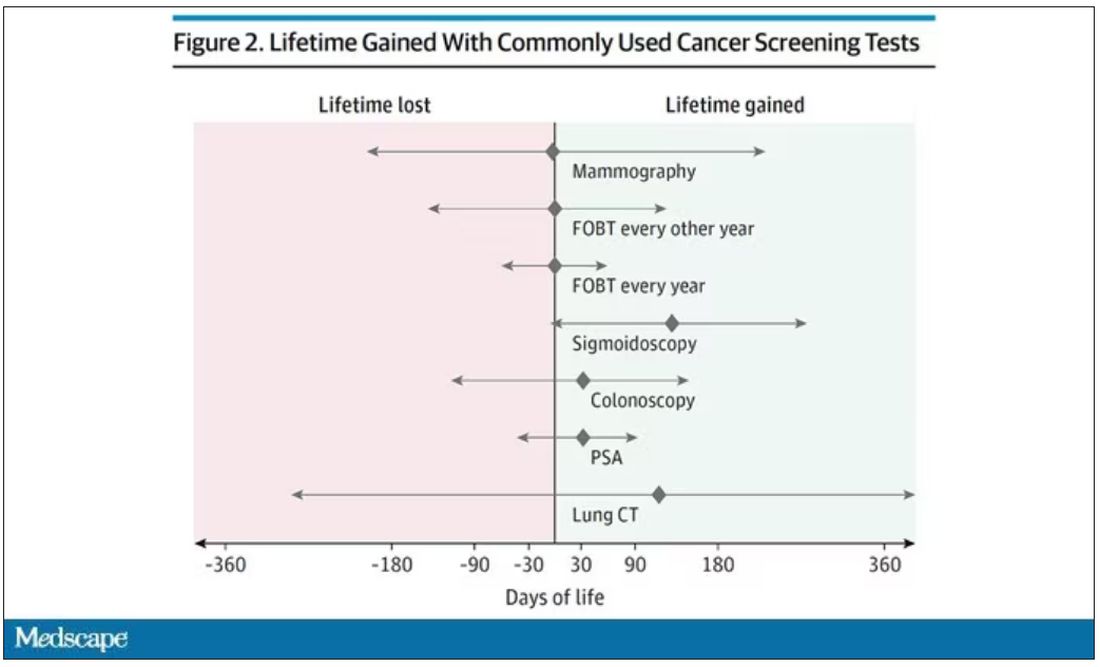

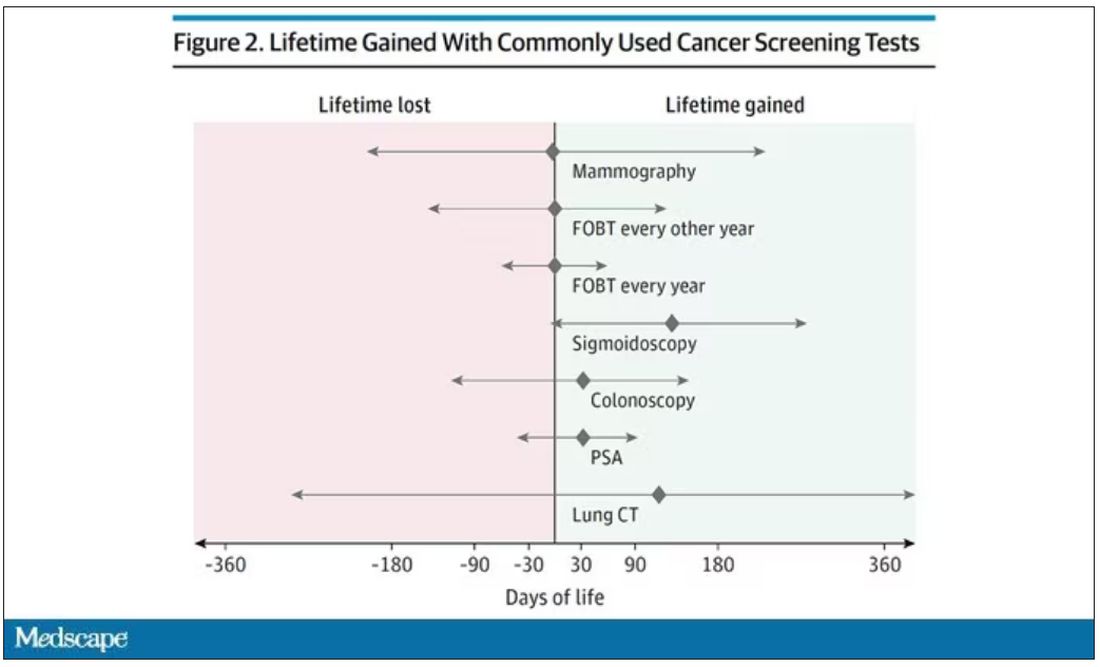

It’s a meta-analysis of very specific randomized trials of cancer screening modalities and concludes that, with the exception of sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, none of them meaningfully change life expectancy.

Now – a bit of inside baseball here – I almost never choose to discuss meta-analyses on Impact Factor. It’s hard enough to dig deep into the methodology of a single study, but with a meta-analysis, you’re sort of obligated to review all the included studies, and, what’s worse, the studies that were not included but might bear on the central question.

In this case, though, the topic is important enough to think about a bit more, and the conclusions have large enough implications for public health that we should question them a bit.

First, let’s run down the study as presented.

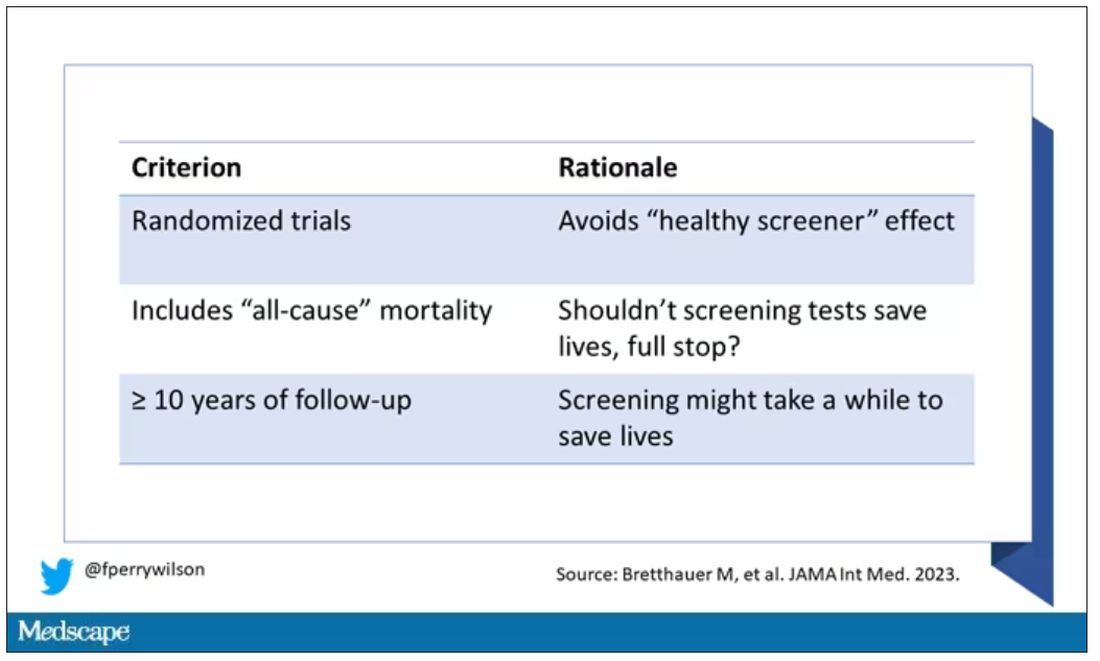

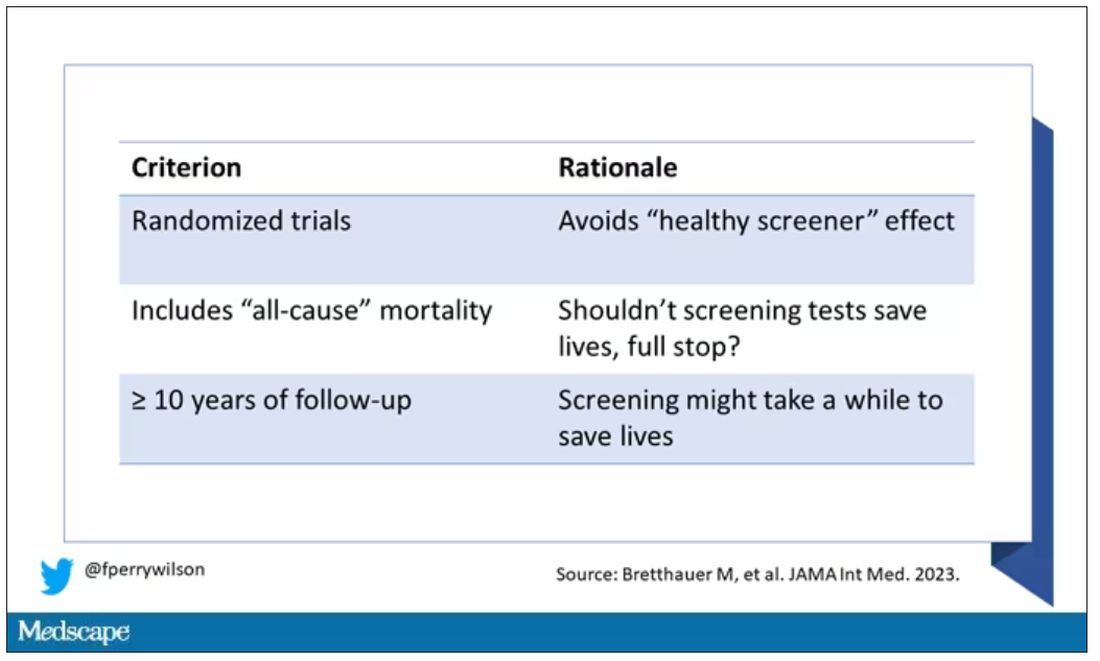

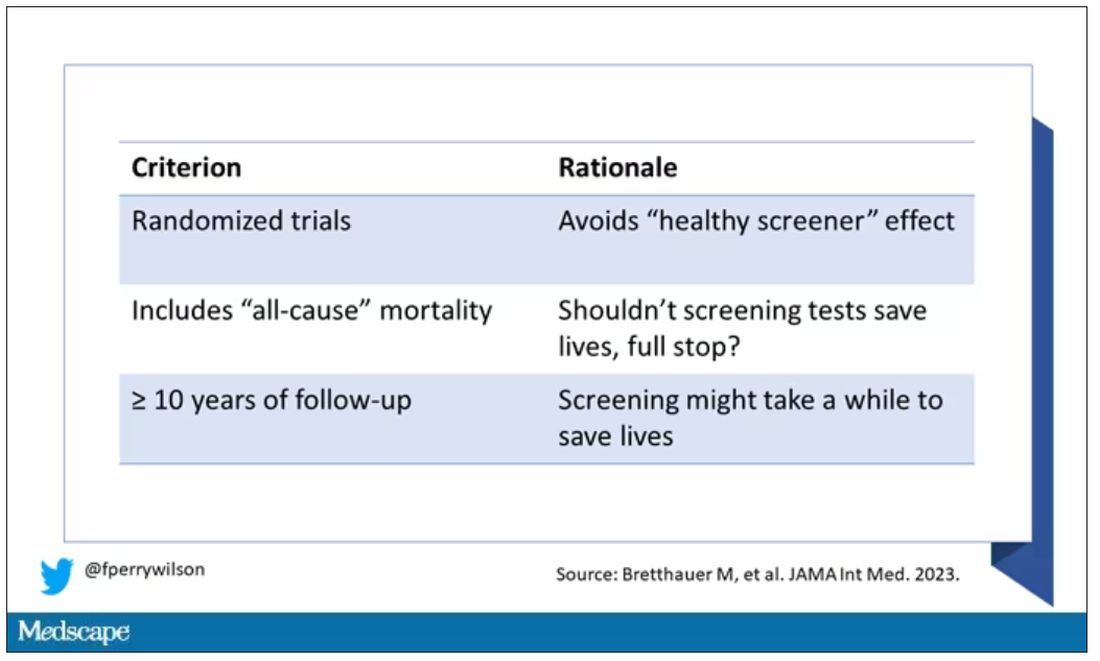

The authors searched for randomized trials of cancer screening modalities. This is important, and I think appropriate. They wanted studies that took some people and assigned them to screening, and some people to no screening – avoiding the confounding that would come from observational data (rule followers like me tend to live longer owing to a variety of healthful behaviors, not just cancer screening).

They didn’t stop at just randomized trials, though. They wanted trials that reported on all-cause, not cancer-specific, mortality. We’ll dig into the distinction in a sec. Finally, they wanted trials with at least 10 years of follow-up time.

These are pretty strict criteria – and after applying that filter, we are left with a grand total of 18 studies to analyze. Most were in the colon cancer space; only two studies met criteria for mammography screening.

Right off the bat, this raises concerns to me. In the universe of high-quality studies of cancer screening modalities, this is just the tip of the iceberg. And the results of meta-analyses are always dependent on the included studies – definitionally.

The results as presented are compelling.

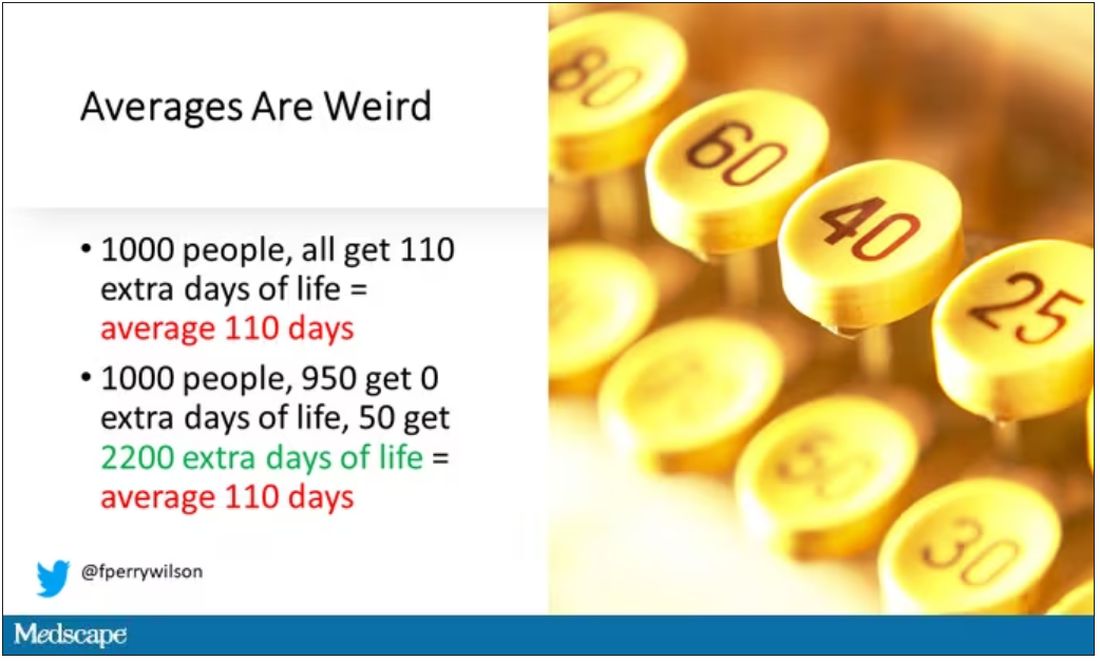

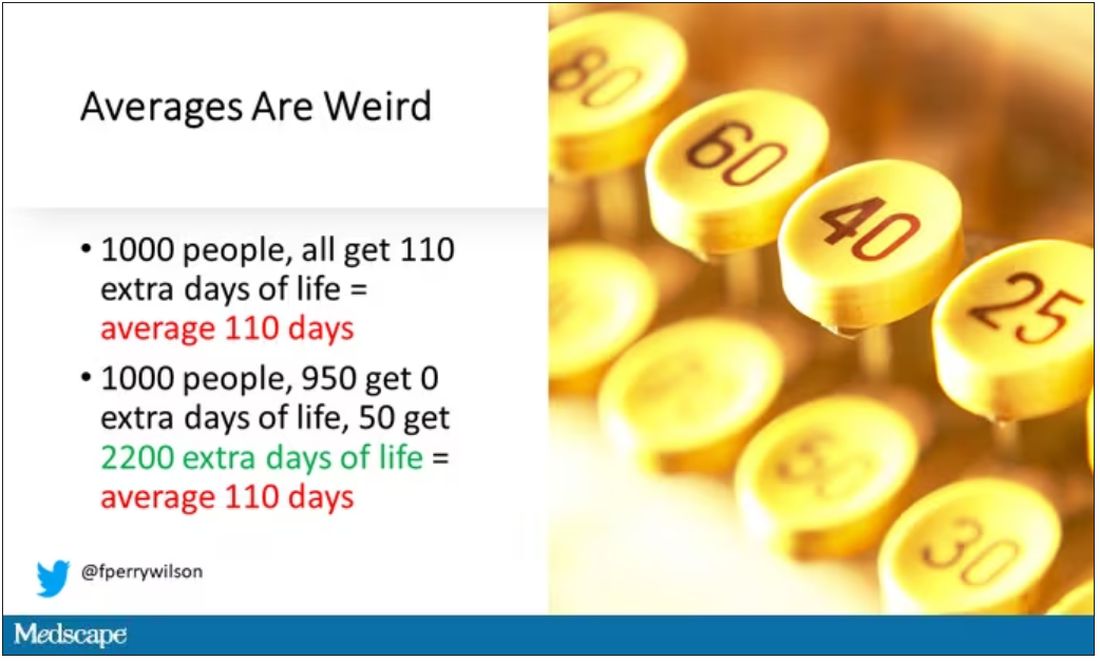

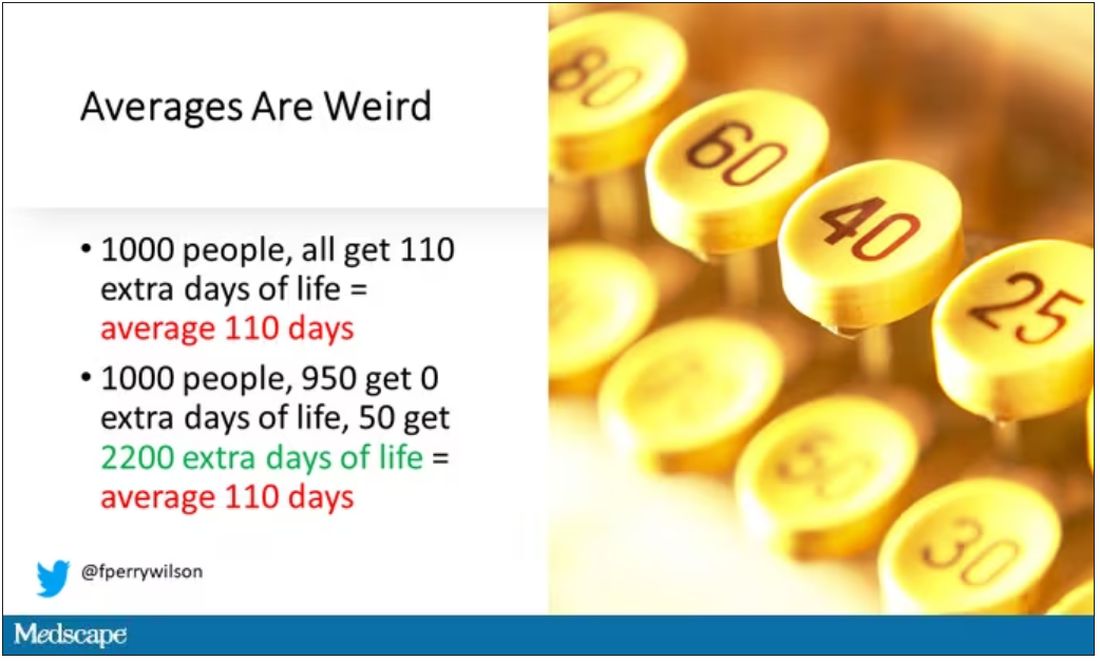

(Side note: Averages are tricky here. It’s not like everyone who gets screened gets 110 extra days. Most people get nothing, and some people – those whose colon cancer was detected early – get a bunch of extra days.)

And a thing about meta-analysis: Meeting the criteria to be included in a meta-analysis does not necessarily mean the study was a good one. For example, one of the two mammography screening studies included is this one, from Miller and colleagues.

On the surface, it looks good – a large randomized trial of mammography screening in Canada, with long-term follow-up including all-cause mortality. Showing, by the way, no effect of screening on either breast cancer–specific or all-cause mortality.

But that study came under a lot of criticism owing to allegations that randomization was broken and women with palpable breast masses were preferentially put into the mammography group, making those outcomes worse.

The authors of the current meta-analysis don’t mention this. Indeed, they state that they don’t perform any assessments of the quality of the included studies.

But I don’t want to criticize all the included studies. Let’s think bigger picture.

Randomized trials of screening for cancers like colon, breast, and lung cancer in smokers have generally shown that those randomized to screening had lower target-cancer–specific mortality. Across all the randomized mammography studies, for example, women randomized to mammography were about 20% less likely to die of breast cancer than were those who were randomized to not be screened – particularly among those above age 50.

But it’s true that all-cause mortality, on the whole, has not differed statistically between those randomized to mammography vs. no mammography. What’s the deal?

Well, the authors of the meta-analysis engage in some zero-sum thinking here. They say that if it is true that screening tests reduce cancer-specific deaths, but all-cause mortality is not different, screening tests must increase mortality due to other causes. How? They cite colonic perforation during colonoscopy as an example of a harm that could lead to earlier death, which makes some sense. For mammogram and other less invasive screening modalities, they suggest that the stress and anxiety associated with screening might increase the risk for death – this is a bit harder for me to defend.

The thing is, statistics really isn’t a zero-sum game. It’s a question of signal vs. noise. Take breast cancer, for example. Without screening, about 3.2% of women in this country would die of breast cancer. With screening, 2.8% would die (that’s a 20% reduction on the relative scale). The truth is, most women don’t die of breast cancer. Most people don’t die of colon cancer. Even most smokers don’t die of lung cancer. Most people die of heart disease. And then cancer – but there are a lot of cancers out there, and only a handful have decent screening tests.

In other words, the screening tests are unlikely to help most people because most people will not die of the particular type of cancer being screened for. But it will help some small number of those people being screened a lot, potentially saving their lives. If we knew who those people were in advance, it would be great, but then I suppose we wouldn’t need the screening test in the first place.

It’s not fair, then, to say that mammography increases non–breast cancer causes of death. In reality, it’s just that the impact of mammography on all-cause mortality is washed out by the random noise inherent to studying a sample of individuals rather than the entire population.

I’m reminded of that old story about the girl on the beach after a storm, throwing beached starfish back into the water. Someone comes by and says, “Why are you doing that? There are millions of starfish here – it doesn’t matter if you throw a few back.” And she says, “It matters for this one.”

There are other issues with aggregating data like these and concluding that there is no effect on all-cause mortality. For one, it assumes the people randomized to no screening never got screening. Most of these studies lasted 5-10 years, some with longer follow-up, but many people in the no-screening arm may have been screened as recommendations have changed. That would tend to bias the results against screening because the so-called control group, well, isn’t.

It also fails to acknowledge the reality that screening for disease can be thought of as a package deal. Instead of asking whether screening for breast cancer, and colon cancer, and lung cancer individually saves lives, the real relevant question is whether a policy of screening for cancer in general saves lives. And that hasn’t been studied very broadly, except in one trial looking at screening for four cancers. That study is in this meta-analysis and, interestingly, seems to suggest that the policy does extend life – by 123 days. Again, be careful how you think about that average.

I don’t want to be an absolutist here. Whether these screening tests are a good idea or not is actually a moving target. As treatment for cancer gets better, detecting cancer early may not be as important. As new screening modalities emerge, older ones may not be preferable any longer. Better testing, genetic or otherwise, might allow us to tailor screening more narrowly than the population-based approach we have now.

But I worry that a meta-analysis like this, which concludes that screening doesn’t help on the basis of a handful of studies – without acknowledgment of the signal-to-noise problem, without accounting for screening in the control group, without acknowledging that screening should be thought of as a package – will lead some people to make the decision to forgo screening. for, say, 49 out of 50 of them, that may be fine. But for 1 out of 50 or so, well, it matters for that one.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript from Impact Factor has been edited for clarity.

If you are my age or older, and like me, you are something of a rule follower, then you’re getting screened for various cancers.

Colonoscopies, mammograms, cervical cancer screening, chest CTs for people with a significant smoking history. The tests are done and usually, but not always, they are negative. And if positive, usually, but not always, follow-up tests are negative, and if they aren’t and a new cancer is diagnosed you tell yourself, Well, at least we caught it early. Isn’t it good that I’m a rule follower? My life was just saved.

But it turns out, proving that cancer screening actually saves lives is quite difficult. Is it possible that all this screening is for nothing?

The benefits, risks, or perhaps futility of cancer screening is in the news this week because of this article, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

It’s a meta-analysis of very specific randomized trials of cancer screening modalities and concludes that, with the exception of sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, none of them meaningfully change life expectancy.

Now – a bit of inside baseball here – I almost never choose to discuss meta-analyses on Impact Factor. It’s hard enough to dig deep into the methodology of a single study, but with a meta-analysis, you’re sort of obligated to review all the included studies, and, what’s worse, the studies that were not included but might bear on the central question.

In this case, though, the topic is important enough to think about a bit more, and the conclusions have large enough implications for public health that we should question them a bit.

First, let’s run down the study as presented.

The authors searched for randomized trials of cancer screening modalities. This is important, and I think appropriate. They wanted studies that took some people and assigned them to screening, and some people to no screening – avoiding the confounding that would come from observational data (rule followers like me tend to live longer owing to a variety of healthful behaviors, not just cancer screening).

They didn’t stop at just randomized trials, though. They wanted trials that reported on all-cause, not cancer-specific, mortality. We’ll dig into the distinction in a sec. Finally, they wanted trials with at least 10 years of follow-up time.

These are pretty strict criteria – and after applying that filter, we are left with a grand total of 18 studies to analyze. Most were in the colon cancer space; only two studies met criteria for mammography screening.

Right off the bat, this raises concerns to me. In the universe of high-quality studies of cancer screening modalities, this is just the tip of the iceberg. And the results of meta-analyses are always dependent on the included studies – definitionally.

The results as presented are compelling.

(Side note: Averages are tricky here. It’s not like everyone who gets screened gets 110 extra days. Most people get nothing, and some people – those whose colon cancer was detected early – get a bunch of extra days.)

And a thing about meta-analysis: Meeting the criteria to be included in a meta-analysis does not necessarily mean the study was a good one. For example, one of the two mammography screening studies included is this one, from Miller and colleagues.

On the surface, it looks good – a large randomized trial of mammography screening in Canada, with long-term follow-up including all-cause mortality. Showing, by the way, no effect of screening on either breast cancer–specific or all-cause mortality.

But that study came under a lot of criticism owing to allegations that randomization was broken and women with palpable breast masses were preferentially put into the mammography group, making those outcomes worse.

The authors of the current meta-analysis don’t mention this. Indeed, they state that they don’t perform any assessments of the quality of the included studies.

But I don’t want to criticize all the included studies. Let’s think bigger picture.

Randomized trials of screening for cancers like colon, breast, and lung cancer in smokers have generally shown that those randomized to screening had lower target-cancer–specific mortality. Across all the randomized mammography studies, for example, women randomized to mammography were about 20% less likely to die of breast cancer than were those who were randomized to not be screened – particularly among those above age 50.

But it’s true that all-cause mortality, on the whole, has not differed statistically between those randomized to mammography vs. no mammography. What’s the deal?

Well, the authors of the meta-analysis engage in some zero-sum thinking here. They say that if it is true that screening tests reduce cancer-specific deaths, but all-cause mortality is not different, screening tests must increase mortality due to other causes. How? They cite colonic perforation during colonoscopy as an example of a harm that could lead to earlier death, which makes some sense. For mammogram and other less invasive screening modalities, they suggest that the stress and anxiety associated with screening might increase the risk for death – this is a bit harder for me to defend.

The thing is, statistics really isn’t a zero-sum game. It’s a question of signal vs. noise. Take breast cancer, for example. Without screening, about 3.2% of women in this country would die of breast cancer. With screening, 2.8% would die (that’s a 20% reduction on the relative scale). The truth is, most women don’t die of breast cancer. Most people don’t die of colon cancer. Even most smokers don’t die of lung cancer. Most people die of heart disease. And then cancer – but there are a lot of cancers out there, and only a handful have decent screening tests.

In other words, the screening tests are unlikely to help most people because most people will not die of the particular type of cancer being screened for. But it will help some small number of those people being screened a lot, potentially saving their lives. If we knew who those people were in advance, it would be great, but then I suppose we wouldn’t need the screening test in the first place.

It’s not fair, then, to say that mammography increases non–breast cancer causes of death. In reality, it’s just that the impact of mammography on all-cause mortality is washed out by the random noise inherent to studying a sample of individuals rather than the entire population.

I’m reminded of that old story about the girl on the beach after a storm, throwing beached starfish back into the water. Someone comes by and says, “Why are you doing that? There are millions of starfish here – it doesn’t matter if you throw a few back.” And she says, “It matters for this one.”

There are other issues with aggregating data like these and concluding that there is no effect on all-cause mortality. For one, it assumes the people randomized to no screening never got screening. Most of these studies lasted 5-10 years, some with longer follow-up, but many people in the no-screening arm may have been screened as recommendations have changed. That would tend to bias the results against screening because the so-called control group, well, isn’t.

It also fails to acknowledge the reality that screening for disease can be thought of as a package deal. Instead of asking whether screening for breast cancer, and colon cancer, and lung cancer individually saves lives, the real relevant question is whether a policy of screening for cancer in general saves lives. And that hasn’t been studied very broadly, except in one trial looking at screening for four cancers. That study is in this meta-analysis and, interestingly, seems to suggest that the policy does extend life – by 123 days. Again, be careful how you think about that average.

I don’t want to be an absolutist here. Whether these screening tests are a good idea or not is actually a moving target. As treatment for cancer gets better, detecting cancer early may not be as important. As new screening modalities emerge, older ones may not be preferable any longer. Better testing, genetic or otherwise, might allow us to tailor screening more narrowly than the population-based approach we have now.

But I worry that a meta-analysis like this, which concludes that screening doesn’t help on the basis of a handful of studies – without acknowledgment of the signal-to-noise problem, without accounting for screening in the control group, without acknowledging that screening should be thought of as a package – will lead some people to make the decision to forgo screening. for, say, 49 out of 50 of them, that may be fine. But for 1 out of 50 or so, well, it matters for that one.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

This transcript from Impact Factor has been edited for clarity.

If you are my age or older, and like me, you are something of a rule follower, then you’re getting screened for various cancers.

Colonoscopies, mammograms, cervical cancer screening, chest CTs for people with a significant smoking history. The tests are done and usually, but not always, they are negative. And if positive, usually, but not always, follow-up tests are negative, and if they aren’t and a new cancer is diagnosed you tell yourself, Well, at least we caught it early. Isn’t it good that I’m a rule follower? My life was just saved.

But it turns out, proving that cancer screening actually saves lives is quite difficult. Is it possible that all this screening is for nothing?

The benefits, risks, or perhaps futility of cancer screening is in the news this week because of this article, appearing in JAMA Internal Medicine.

It’s a meta-analysis of very specific randomized trials of cancer screening modalities and concludes that, with the exception of sigmoidoscopy for colon cancer screening, none of them meaningfully change life expectancy.

Now – a bit of inside baseball here – I almost never choose to discuss meta-analyses on Impact Factor. It’s hard enough to dig deep into the methodology of a single study, but with a meta-analysis, you’re sort of obligated to review all the included studies, and, what’s worse, the studies that were not included but might bear on the central question.

In this case, though, the topic is important enough to think about a bit more, and the conclusions have large enough implications for public health that we should question them a bit.

First, let’s run down the study as presented.

The authors searched for randomized trials of cancer screening modalities. This is important, and I think appropriate. They wanted studies that took some people and assigned them to screening, and some people to no screening – avoiding the confounding that would come from observational data (rule followers like me tend to live longer owing to a variety of healthful behaviors, not just cancer screening).

They didn’t stop at just randomized trials, though. They wanted trials that reported on all-cause, not cancer-specific, mortality. We’ll dig into the distinction in a sec. Finally, they wanted trials with at least 10 years of follow-up time.

These are pretty strict criteria – and after applying that filter, we are left with a grand total of 18 studies to analyze. Most were in the colon cancer space; only two studies met criteria for mammography screening.

Right off the bat, this raises concerns to me. In the universe of high-quality studies of cancer screening modalities, this is just the tip of the iceberg. And the results of meta-analyses are always dependent on the included studies – definitionally.

The results as presented are compelling.

(Side note: Averages are tricky here. It’s not like everyone who gets screened gets 110 extra days. Most people get nothing, and some people – those whose colon cancer was detected early – get a bunch of extra days.)

And a thing about meta-analysis: Meeting the criteria to be included in a meta-analysis does not necessarily mean the study was a good one. For example, one of the two mammography screening studies included is this one, from Miller and colleagues.

On the surface, it looks good – a large randomized trial of mammography screening in Canada, with long-term follow-up including all-cause mortality. Showing, by the way, no effect of screening on either breast cancer–specific or all-cause mortality.

But that study came under a lot of criticism owing to allegations that randomization was broken and women with palpable breast masses were preferentially put into the mammography group, making those outcomes worse.

The authors of the current meta-analysis don’t mention this. Indeed, they state that they don’t perform any assessments of the quality of the included studies.

But I don’t want to criticize all the included studies. Let’s think bigger picture.

Randomized trials of screening for cancers like colon, breast, and lung cancer in smokers have generally shown that those randomized to screening had lower target-cancer–specific mortality. Across all the randomized mammography studies, for example, women randomized to mammography were about 20% less likely to die of breast cancer than were those who were randomized to not be screened – particularly among those above age 50.

But it’s true that all-cause mortality, on the whole, has not differed statistically between those randomized to mammography vs. no mammography. What’s the deal?

Well, the authors of the meta-analysis engage in some zero-sum thinking here. They say that if it is true that screening tests reduce cancer-specific deaths, but all-cause mortality is not different, screening tests must increase mortality due to other causes. How? They cite colonic perforation during colonoscopy as an example of a harm that could lead to earlier death, which makes some sense. For mammogram and other less invasive screening modalities, they suggest that the stress and anxiety associated with screening might increase the risk for death – this is a bit harder for me to defend.

The thing is, statistics really isn’t a zero-sum game. It’s a question of signal vs. noise. Take breast cancer, for example. Without screening, about 3.2% of women in this country would die of breast cancer. With screening, 2.8% would die (that’s a 20% reduction on the relative scale). The truth is, most women don’t die of breast cancer. Most people don’t die of colon cancer. Even most smokers don’t die of lung cancer. Most people die of heart disease. And then cancer – but there are a lot of cancers out there, and only a handful have decent screening tests.

In other words, the screening tests are unlikely to help most people because most people will not die of the particular type of cancer being screened for. But it will help some small number of those people being screened a lot, potentially saving their lives. If we knew who those people were in advance, it would be great, but then I suppose we wouldn’t need the screening test in the first place.

It’s not fair, then, to say that mammography increases non–breast cancer causes of death. In reality, it’s just that the impact of mammography on all-cause mortality is washed out by the random noise inherent to studying a sample of individuals rather than the entire population.

I’m reminded of that old story about the girl on the beach after a storm, throwing beached starfish back into the water. Someone comes by and says, “Why are you doing that? There are millions of starfish here – it doesn’t matter if you throw a few back.” And she says, “It matters for this one.”

There are other issues with aggregating data like these and concluding that there is no effect on all-cause mortality. For one, it assumes the people randomized to no screening never got screening. Most of these studies lasted 5-10 years, some with longer follow-up, but many people in the no-screening arm may have been screened as recommendations have changed. That would tend to bias the results against screening because the so-called control group, well, isn’t.

It also fails to acknowledge the reality that screening for disease can be thought of as a package deal. Instead of asking whether screening for breast cancer, and colon cancer, and lung cancer individually saves lives, the real relevant question is whether a policy of screening for cancer in general saves lives. And that hasn’t been studied very broadly, except in one trial looking at screening for four cancers. That study is in this meta-analysis and, interestingly, seems to suggest that the policy does extend life – by 123 days. Again, be careful how you think about that average.

I don’t want to be an absolutist here. Whether these screening tests are a good idea or not is actually a moving target. As treatment for cancer gets better, detecting cancer early may not be as important. As new screening modalities emerge, older ones may not be preferable any longer. Better testing, genetic or otherwise, might allow us to tailor screening more narrowly than the population-based approach we have now.

But I worry that a meta-analysis like this, which concludes that screening doesn’t help on the basis of a handful of studies – without acknowledgment of the signal-to-noise problem, without accounting for screening in the control group, without acknowledging that screening should be thought of as a package – will lead some people to make the decision to forgo screening. for, say, 49 out of 50 of them, that may be fine. But for 1 out of 50 or so, well, it matters for that one.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. His science communication work can be found in the Huffington Post, on NPR, and on Medscape. He tweets @fperrywilson and his new book, How Medicine Works and When It Doesn’t, is available now. He has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.