User login

A 73-year-old male veteran with a history of ischemic stroke with left-sided deficits and edema, falls, poorly controlled hypertension, active tobacco use, obesity, and prediabetes was assessed on a routine visit by our home-based primary care team and found to have a new, unilateral, asymptomatic rash. He reported feeling no pain in the affected area or any significant increase in the baseline left lower extremity edema and weakness resulting from his stroke 2 years prior.

On the left lateral leg from mid-thigh to mid-calf, there was a nontender, flat, reticulated rash with pigmentary alteration ranging from light brown to dark brown (Figure).

On further questioning, the patient reported regular use of a space heater because his gas furnace had been destroyed in an earthquake more than 20 years before. He would place this heater close to his left leg when using the computer or while sleeping in his wheelchair.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Our Diagnosis

Erythema ab igne, also called hot water bottle rash, is a clinical diagnosis based on characteristic cutaneous findings and a clear history of chronic, moderate heat or infrared exposure.1 Although exposure to space heaters, open fire, radiators, hot water bottles, and heating pads are the classic causes, recently there have been reports of laptop computers, cell phones, infrared food lamps, automobile seat heaters, and heated recliners causing the same type of skin reaction.2

With chronic moderate heat or infrared exposure, the rash usually progresses over days to months. It begins as a mild, transient, reticulated, erythematous rash, which follows the pattern of the cutaneous venous plexus and resolves minutes to hours after removal of the offending source as vasodilation resolves. After months of continued exposure, the dermis around the affected vasculature eventually becomes hyperpigmented due to the deposition of melanin and sometimes hemosiderin.

The rash is usually asymptomatic but has been associated with pain, pruritis, and/or tingling. Once the diagnosis is made, treatment involves removal of the offending source. The discoloration may resolve over months to years, but permanent hyperpigmentation is not uncommon. There are a few case reports on treatment using Nd-Yag laser therapy, topical hydroquinone and tretinoin, 5-fluorouracil, and systemic mesoglycan with topical bioflavonoids.2-4

While the prognosis of erythema ab igne is excellent if detected early, failure to recognize this condition and remove the offending source can lead to sequalae, such as squamous cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma.5-8 Development of malignancy typically has a latency period of > 30 years. Patients should have periodic surveillance of their skin and any suspicious lesion in the involved area should be considered for biopsy.

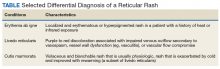

Rashes may represent systemic or more localized pathology (Table). In contrast to erythema ab igne, the rash associated with a vasculitic process (autoimmune, drug-induced, or infectious) tends to be more generalized and bilateral but still follows the pattern of the cutaneous venous plexus. An example of this would be livedo reticularis. Although this rash is reticular, it is not hyperpigmented.9 A variant of livedo reticularis is cutis marmorata, which develops in response to cold exposure, particularly in infants or in the setting of hypothyroidism.Cutis marmorata is erythematous, blanchable, and reversible with rewarming. Unlike erythema ab igne, there is no hyperpigmentation and tends to be more diffuse.10

When evaluating a reticular rash, consider local and systemic etiologies. If more localized and hyperpigmented, ask about heat or infrared exposure. This may point to a diagnosis of erythema ab igne.

1. Page EH, Shear NH. Temperature-dependent skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(5, pt 1):1003-1019.

2. Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162(1):77-78.

3. Kim HW, Kim EJ, Park HC, Ko JY, Ro YS, Kim JE. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with low fluenced 1,064-nm Q-switched Neodymium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16(3):147-148.

4. Gianfaldoni S, Gianfaldoni R, Tchernev G, Lotti J, Wollina U, Lotti T. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with mesoglycan and bioflavonoids: a case-report. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(4):432-435.

5. Arrington JH 3rd, Lockman DS. Thermal keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma in situ associated with erythema ab igne. AMA Arch Derm. 1979;115(10):1226-1228.

6. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, Sangueza O, Sheehan DJ. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35(6):676-678

7. Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, Sheehan DJ. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):1080-1081.

8. Jones CS. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(1):110-113.

9. Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, Pandit AM. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(5):315-321.

10. O’Connor NR, McLaughlin MR, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I. Common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):47-52.

A 73-year-old male veteran with a history of ischemic stroke with left-sided deficits and edema, falls, poorly controlled hypertension, active tobacco use, obesity, and prediabetes was assessed on a routine visit by our home-based primary care team and found to have a new, unilateral, asymptomatic rash. He reported feeling no pain in the affected area or any significant increase in the baseline left lower extremity edema and weakness resulting from his stroke 2 years prior.

On the left lateral leg from mid-thigh to mid-calf, there was a nontender, flat, reticulated rash with pigmentary alteration ranging from light brown to dark brown (Figure).

On further questioning, the patient reported regular use of a space heater because his gas furnace had been destroyed in an earthquake more than 20 years before. He would place this heater close to his left leg when using the computer or while sleeping in his wheelchair.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Our Diagnosis

Erythema ab igne, also called hot water bottle rash, is a clinical diagnosis based on characteristic cutaneous findings and a clear history of chronic, moderate heat or infrared exposure.1 Although exposure to space heaters, open fire, radiators, hot water bottles, and heating pads are the classic causes, recently there have been reports of laptop computers, cell phones, infrared food lamps, automobile seat heaters, and heated recliners causing the same type of skin reaction.2

With chronic moderate heat or infrared exposure, the rash usually progresses over days to months. It begins as a mild, transient, reticulated, erythematous rash, which follows the pattern of the cutaneous venous plexus and resolves minutes to hours after removal of the offending source as vasodilation resolves. After months of continued exposure, the dermis around the affected vasculature eventually becomes hyperpigmented due to the deposition of melanin and sometimes hemosiderin.

The rash is usually asymptomatic but has been associated with pain, pruritis, and/or tingling. Once the diagnosis is made, treatment involves removal of the offending source. The discoloration may resolve over months to years, but permanent hyperpigmentation is not uncommon. There are a few case reports on treatment using Nd-Yag laser therapy, topical hydroquinone and tretinoin, 5-fluorouracil, and systemic mesoglycan with topical bioflavonoids.2-4

While the prognosis of erythema ab igne is excellent if detected early, failure to recognize this condition and remove the offending source can lead to sequalae, such as squamous cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma.5-8 Development of malignancy typically has a latency period of > 30 years. Patients should have periodic surveillance of their skin and any suspicious lesion in the involved area should be considered for biopsy.

Rashes may represent systemic or more localized pathology (Table). In contrast to erythema ab igne, the rash associated with a vasculitic process (autoimmune, drug-induced, or infectious) tends to be more generalized and bilateral but still follows the pattern of the cutaneous venous plexus. An example of this would be livedo reticularis. Although this rash is reticular, it is not hyperpigmented.9 A variant of livedo reticularis is cutis marmorata, which develops in response to cold exposure, particularly in infants or in the setting of hypothyroidism.Cutis marmorata is erythematous, blanchable, and reversible with rewarming. Unlike erythema ab igne, there is no hyperpigmentation and tends to be more diffuse.10

When evaluating a reticular rash, consider local and systemic etiologies. If more localized and hyperpigmented, ask about heat or infrared exposure. This may point to a diagnosis of erythema ab igne.

A 73-year-old male veteran with a history of ischemic stroke with left-sided deficits and edema, falls, poorly controlled hypertension, active tobacco use, obesity, and prediabetes was assessed on a routine visit by our home-based primary care team and found to have a new, unilateral, asymptomatic rash. He reported feeling no pain in the affected area or any significant increase in the baseline left lower extremity edema and weakness resulting from his stroke 2 years prior.

On the left lateral leg from mid-thigh to mid-calf, there was a nontender, flat, reticulated rash with pigmentary alteration ranging from light brown to dark brown (Figure).

On further questioning, the patient reported regular use of a space heater because his gas furnace had been destroyed in an earthquake more than 20 years before. He would place this heater close to his left leg when using the computer or while sleeping in his wheelchair.

- What is your diagnosis?

- How would you treat this patient?

Our Diagnosis

Erythema ab igne, also called hot water bottle rash, is a clinical diagnosis based on characteristic cutaneous findings and a clear history of chronic, moderate heat or infrared exposure.1 Although exposure to space heaters, open fire, radiators, hot water bottles, and heating pads are the classic causes, recently there have been reports of laptop computers, cell phones, infrared food lamps, automobile seat heaters, and heated recliners causing the same type of skin reaction.2

With chronic moderate heat or infrared exposure, the rash usually progresses over days to months. It begins as a mild, transient, reticulated, erythematous rash, which follows the pattern of the cutaneous venous plexus and resolves minutes to hours after removal of the offending source as vasodilation resolves. After months of continued exposure, the dermis around the affected vasculature eventually becomes hyperpigmented due to the deposition of melanin and sometimes hemosiderin.

The rash is usually asymptomatic but has been associated with pain, pruritis, and/or tingling. Once the diagnosis is made, treatment involves removal of the offending source. The discoloration may resolve over months to years, but permanent hyperpigmentation is not uncommon. There are a few case reports on treatment using Nd-Yag laser therapy, topical hydroquinone and tretinoin, 5-fluorouracil, and systemic mesoglycan with topical bioflavonoids.2-4

While the prognosis of erythema ab igne is excellent if detected early, failure to recognize this condition and remove the offending source can lead to sequalae, such as squamous cell carcinoma, poorly differentiated carcinoma, cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma, and Merkel cell carcinoma.5-8 Development of malignancy typically has a latency period of > 30 years. Patients should have periodic surveillance of their skin and any suspicious lesion in the involved area should be considered for biopsy.

Rashes may represent systemic or more localized pathology (Table). In contrast to erythema ab igne, the rash associated with a vasculitic process (autoimmune, drug-induced, or infectious) tends to be more generalized and bilateral but still follows the pattern of the cutaneous venous plexus. An example of this would be livedo reticularis. Although this rash is reticular, it is not hyperpigmented.9 A variant of livedo reticularis is cutis marmorata, which develops in response to cold exposure, particularly in infants or in the setting of hypothyroidism.Cutis marmorata is erythematous, blanchable, and reversible with rewarming. Unlike erythema ab igne, there is no hyperpigmentation and tends to be more diffuse.10

When evaluating a reticular rash, consider local and systemic etiologies. If more localized and hyperpigmented, ask about heat or infrared exposure. This may point to a diagnosis of erythema ab igne.

1. Page EH, Shear NH. Temperature-dependent skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(5, pt 1):1003-1019.

2. Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162(1):77-78.

3. Kim HW, Kim EJ, Park HC, Ko JY, Ro YS, Kim JE. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with low fluenced 1,064-nm Q-switched Neodymium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16(3):147-148.

4. Gianfaldoni S, Gianfaldoni R, Tchernev G, Lotti J, Wollina U, Lotti T. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with mesoglycan and bioflavonoids: a case-report. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(4):432-435.

5. Arrington JH 3rd, Lockman DS. Thermal keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma in situ associated with erythema ab igne. AMA Arch Derm. 1979;115(10):1226-1228.

6. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, Sangueza O, Sheehan DJ. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35(6):676-678

7. Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, Sheehan DJ. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):1080-1081.

8. Jones CS. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(1):110-113.

9. Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, Pandit AM. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(5):315-321.

10. O’Connor NR, McLaughlin MR, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I. Common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):47-52.

1. Page EH, Shear NH. Temperature-dependent skin disorders. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1988;18(5, pt 1):1003-1019.

2. Tan S, Bertucci V. Erythema ab igne: an old condition new again. CMAJ. 2000;162(1):77-78.

3. Kim HW, Kim EJ, Park HC, Ko JY, Ro YS, Kim JE. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with low fluenced 1,064-nm Q-switched Neodymium-Doped Yttrium Aluminum Garnet laser. J Cosmet Laser Ther. 2014;16(3):147-148.

4. Gianfaldoni S, Gianfaldoni R, Tchernev G, Lotti J, Wollina U, Lotti T. Erythema ab igne successfully treated with mesoglycan and bioflavonoids: a case-report. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(4):432-435.

5. Arrington JH 3rd, Lockman DS. Thermal keratoses and squamous cell carcinoma in situ associated with erythema ab igne. AMA Arch Derm. 1979;115(10):1226-1228.

6. Sigmon JR, Cantrell J, Teague D, Sangueza O, Sheehan DJ. Poorly differentiated carcinoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. Am J Dermatopathol. 2013;35(6):676-678

7. Wharton J, Roffwarg D, Miller J, Sheehan DJ. Cutaneous marginal zone lymphoma arising in the setting of erythema ab igne. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2010;62(6):1080-1081.

8. Jones CS. Development of neuroendocrine (Merkel cell) carcinoma mixed with squamous cell carcinoma in erythema ab igne. Arch Dermatol. 1988;124(1):110-113.

9. Sajjan VV, Lunge S, Swamy MB, Pandit AM. Livedo reticularis: a review of the literature. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6(5):315-321.

10. O’Connor NR, McLaughlin MR, Ham P. Newborn skin: part I. Common rashes. Am Fam Physician. 2008;77(1):47-52.