User login

› Require athletes who sustain a concussion to wait a minimum of 7 to 10 days before returning to full unrestricted activity. C

› Ensure that any player diagnosed with concussion follows a guided return-to-play progression, supervised by an athletic trainer or physical therapist experienced in post-concussion care. C

› Advise patients who are old enough to drive not to do so for at least 24 hours after a concussion. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Each year in the United States, more than 44 million young people participate in sports activities.1 Yet the number of concussions incurred annually by children and adolescents engaged in sports and recreational play has been underestimated for years, and largely unknown.1,2

Some estimates were based solely on the number of young athletes treated in emergency departments or sports concussion clinics. Others focused only on team players of middle school or high school age, excluding younger children who were hit in the head on playgrounds or during other recreational activities. What’s more, large numbers of concussions—as many as 4 in 10 incurred by high school athletes—were never reported to a coach or medical professional.3

In a new study published in the journal Pediatrics in June, researchers used national databases and current literature to provide what they believe to be “the most accurate and precise estimate of youth concussion” thus far: Between 1.1 and 1.9 million sports- and recreation-related concussions occur among US youth ages 18 or younger annually.1

Among young people playing team sports, concussions are between 2 and 7 times more likely to occur during competitive games than in practice sessions.4-7 Boys on football and ice hockey teams have the highest rates of concussion in young athletes.For overall number of concussions, however, girls on soccer teams are second only to football players.4 Female soccer players are more likely than male soccer players to sustain concussions during equal number of hours of play.4,7

An increase in incidence. The incidence of concussion among young athletes appears to have increased in the past decade, a likely result of greater involvement in team sports, an increasing focus on safeguarding young people from the potential dangers associated with a blow to the brain, and better diagnostic techniques.4,8-10 And a recent study based on data from electronic medical records at a large regional pediatric health care network found that more than three-quarters of young people with sports-related concussions were first seen in a primary care setting.2

With this in mind, we present a comprehensive update of the evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of sport-related concussion. The recommendations we include are consistent with professional association guidelines.8-10 Although we focus on concussion in children and adolescents involved in athletic activities, the principles generally apply to patients of all ages and to concussions that may not be sports related.

Removal from play: A vital first step

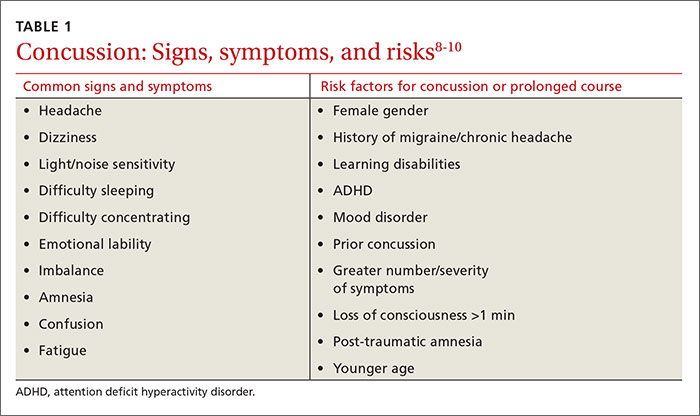

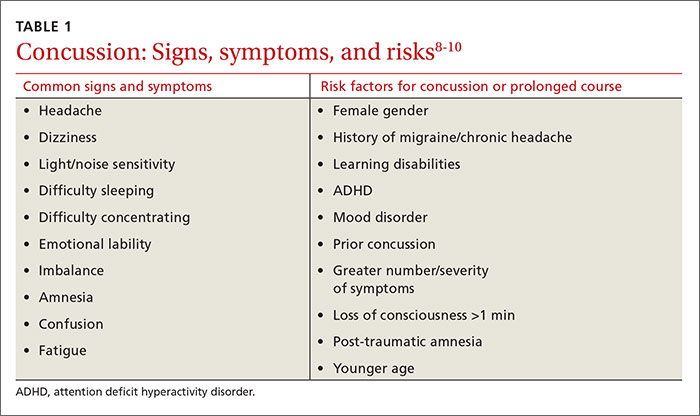

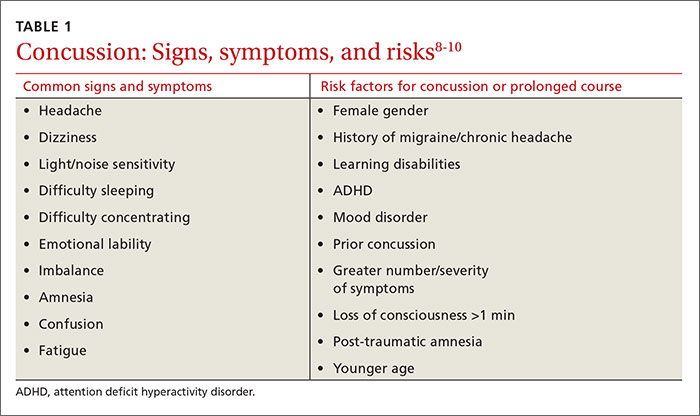

Whenever you conduct a physical exam for a young athlete, remind him or her—and the patient’s parents—that after a blow to the head, immediate removal from play is critical. Concussion is caused by a direct or indirect force to the brain that results in a transient disturbance in brain function,8-10 manifested by alterations in neurocognitive and motor function. While the signs and symptoms (TABLE 1)8-10 resolve within 10 days of injury in about 90% of cases, those who incur additional head impact within 24 hours have a higher symptom burden and prolonged recovery period.11 Even without repetitive impact, younger athletes may take longer to recover.8-10

The initial assessment

A child or adolescent who sustains a suspected concussion should be seen by a physician within 24 to 48 hours. Whether the initial assessment occurs in your office or on the sidelines of a game, it is important to confirm the time the incident occurred and the mechanism of injury.

Concussion is diagnosed by a combination of history, physical exam, and objective testing when symptoms or exam findings associated with mild brain trauma—headache, dizziness, light and/or noise sensitivity, among others—closely follow a head injury.8-10 Certain maneuvers—assessing eye movements by asking the athlete to look in various directions, for instance, then to follow a pen or finger as you move it closer to his or her face—may provoke dizziness, headache, or other symptoms of concussion that were not apparent initially.

The differential diagnosis includes cervical musculoskeletal injury, craniofacial injury, epidural and subdural hematoma, heat-related illness, uncomplicated headache and migraine, upper respiratory infection, and vertigo.8-10

Tools aid in diagnosis

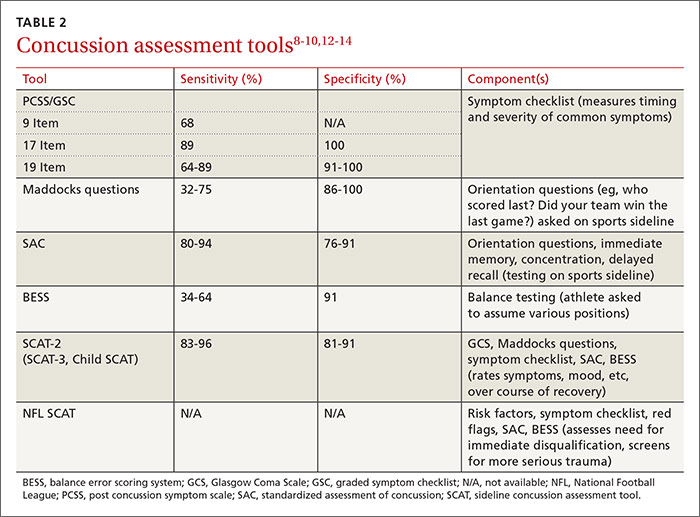

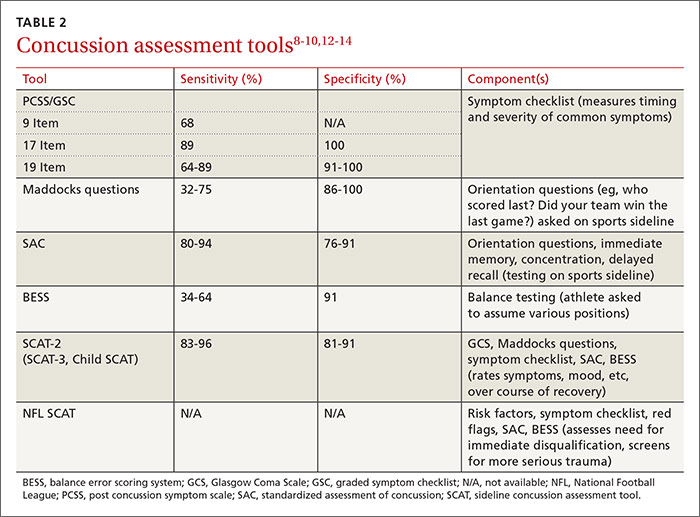

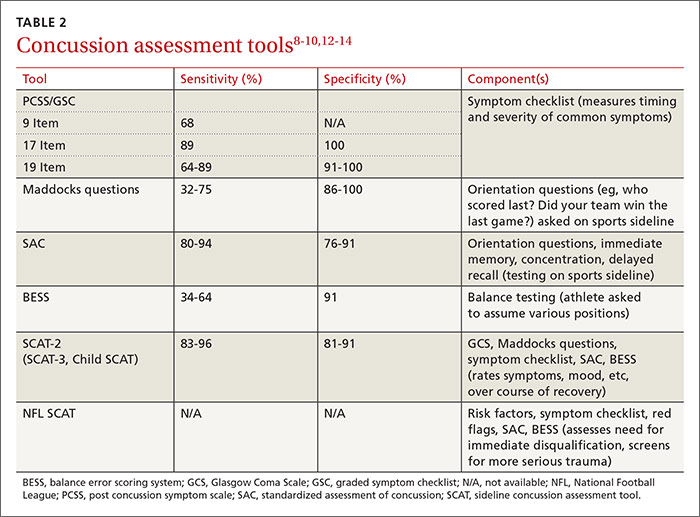

Many clinical assessment tools exist to aid in the diagnosis of concussion (TABLE 2).8-10,12-14 Any one of these tools, many of which use combinations of symptom checklists, balance exams, and cognitive assessments, may be included in your evaluation. No single tool has been found to be superior to any other.8-10 A combination of tools may improve diagnostic accuracy, but assessment tools should not be the sole basis used to diagnose or rule out concussion.

Any child or adolescent who had a blow to the head and at least one sign or symptom of concussion should be evaluated as soon as possible and assessed again later that day or the next day if any reason for concern remains.

Neuropsychological (NP) testing may involve computerized tests developed specifically for athletes. Patients may be required to react to objects that appear on a screen, for example, in a way that tests memory, performance, and reaction time. Because cognitive recovery often lags behind symptom resolution, NP testing may identify subtle brain deficits even in athletes who are asymptomatic at rest or with exercise. In general, NP testing has a sensitivity of 71% to 88% for athletes with concussion,10 but it is most beneficial when baseline test results are available. Interpretation of NP testing should be done only by qualified clinicians.

While NP testing may provide additional prognostic information, it should not alter the management of athletes who are symptomatic either at rest or with exercise.15 Nor is NP testing vital, as concussion can be accurately diagnosed and adequately managed without it.

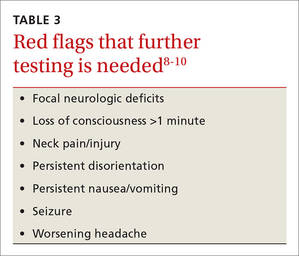

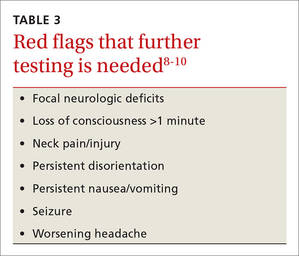

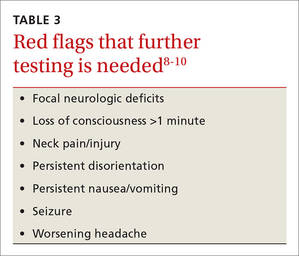

Neuroimaging, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is often used unnecessarily in the initial assessment of a patient who sustained a possible concussion.8-10 In fact, neuroimaging should be reserved for cases in which it is necessary to rule out more serious pathology: intracranial or subdural hematoma or a craniofacial injury, for example, in patients with clinical findings that are red flags. These red flags include focal neurologic deficits, continuing nausea/vomiting, or persistent disorientation (TABLE 3),8-10 or symptoms that worsen or persist beyond a few weeks. In such cases, further evaluation—with MRI of the brain, formal NP testing, and/or referral to a neurologist, physiatrist, or other physician who specializes in concussion care—is indicated.

Concussion management: Rest is key

While there is a dearth of high-quality studies on the management of sport-related concussion across all age groups, standardized protocols for both children and adults have been adopted in most clinical settings.8-10,16,17 The protocols provide a framework for an individualized treatment plan. Yet their use among primary care physicians is inconsistent.18-20

Traditionally, concussion management begins with relative physical and cognitive rest to allow the brain time to recover.8-10 Recent randomized controlled trials have challenged this premise by suggesting that mild to moderate physical activity for post-concussion patients who are mildly symptomatic does not adversely affect recovery.21,22 These studies have significant limitations, however, and further research is needed to provide specific guidance on this aspect of concussion management before it is adopted.

Physical restrictions include organized sports, recreational activity, recess, and physical education classes. Walking is permitted unless it exacerbates symptoms. These restrictions should continue until the patient is symptom-free.

Cognitive restrictions include modifications at school and at home. Once an athlete is able to concentrate and tolerate visual and auditory stimuli, he or she may return to school. But classroom modifications should be considered, possibly including shortened school days, extra time for testing and homework, help with note taking, and restrictions from classes likely to provoke symptoms, such as computer science or music. Limiting use of mobile devices, television viewing, noisy environments, and other possible provocations may help speed symptom resolution. These restrictions, too, should remain in place until the patient is symptom-free.

Driving is often not addressed by physicians managing the care of athletes with concussion, but evidence suggests it should be. A study of patients presenting to the emergency department found that within 24 hours of a concussion diagnosis, individuals had an impaired response to traffic hazards.23,24 And Canadian clinical practice guidelines recommend that athletes with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) avoid driving within the first 24 hours.25

While American guidelines are silent on the question of driving for this patient population, we recommend that athletes with concussion be restricted from driving and engaging in other risky complex tasks, such as welding or shop class, for at least 24 hours. For many athletes diagnosed with concussion, driving restrictions of longer duration may be necessary based on their symptom profile and neurocognitive test results. Continued dizziness or visual deficits would pose a greater risk than fatigue or short-term memory loss, for example.

Overseeing the return to play

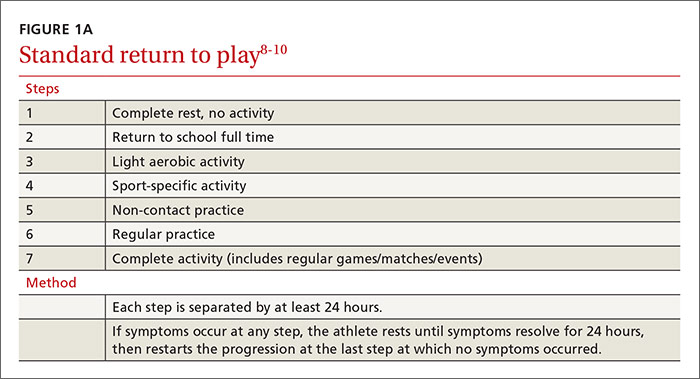

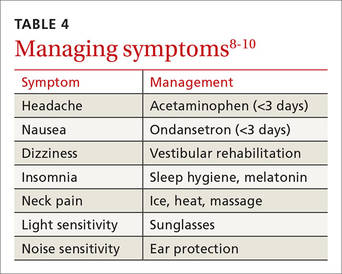

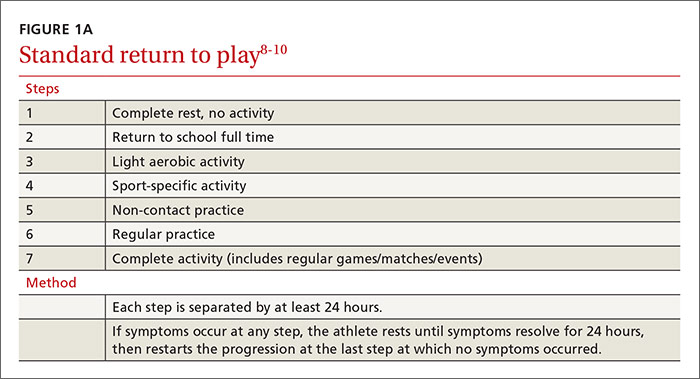

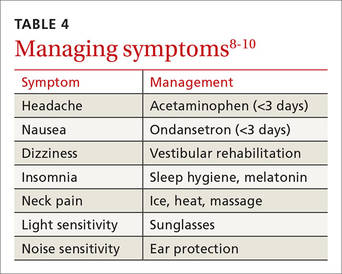

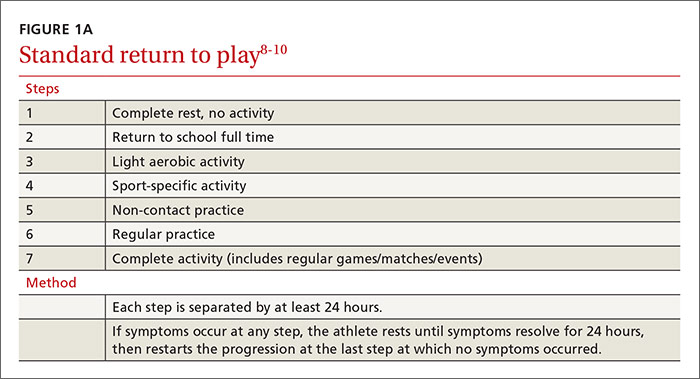

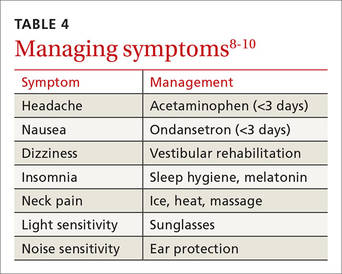

Return-to-activity progression follows a stepwise protocol, with 6 steps that the injured athlete must complete before resuming full activity (FIGURE 1A).8-10 This stepwise progression begins only when athletes are symptom free, even during provocative maneuvers; have had a normal neurologic exam, are back to school full time with no restriction; are off any medications prescribed for concussion symptoms (TABLE 4),8-10 and when neurocognitive testing, if performed, is back to baseline. If an athlete develops symptoms at any stage of the progression, rest is required until he or she remains asymptomatic for at least 24 hours. The progression is then restarted at the last stage at which the patient was symptom free.

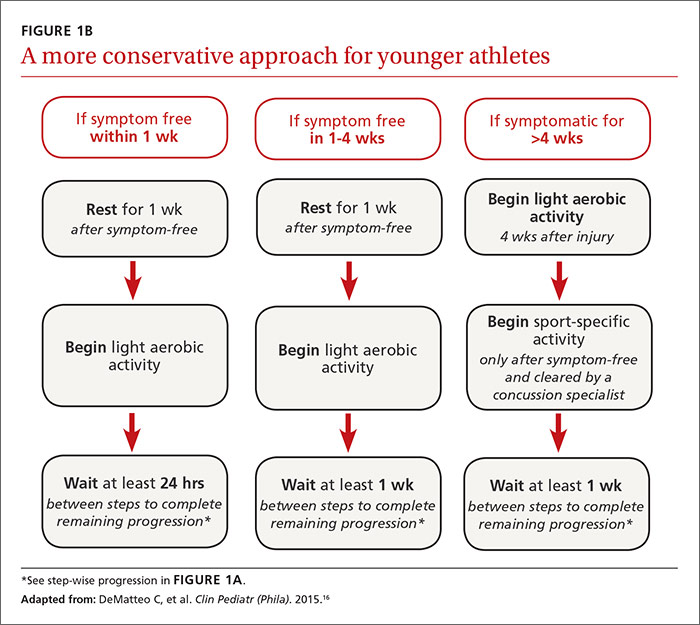

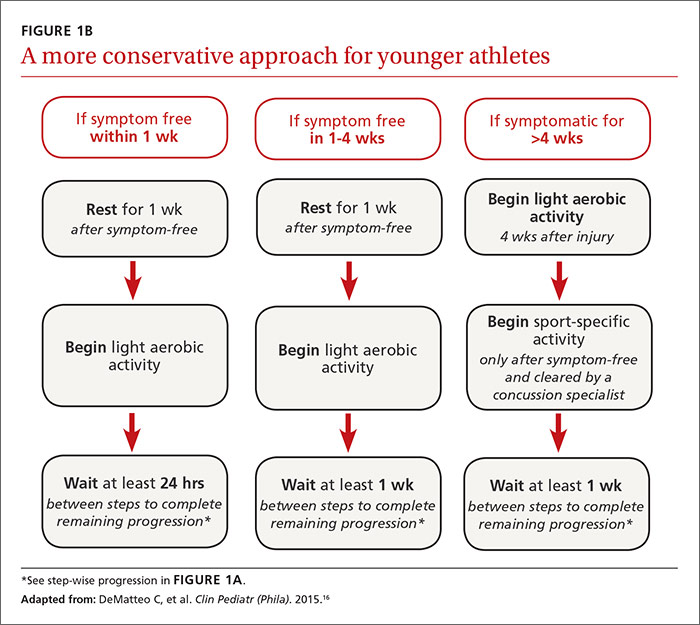

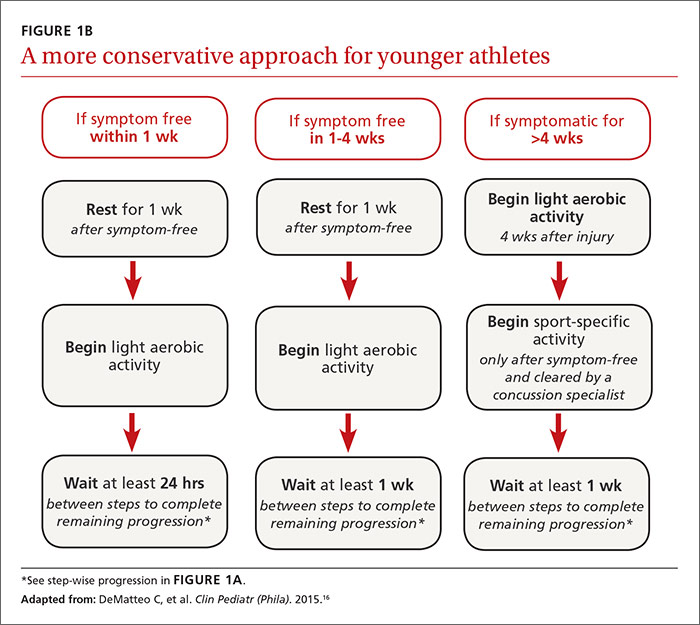

Some individualization, of course, is recommended here, too. Younger athletes and those with a prior history of concussion may require 10 days or more to complete all the steps, allowing an extra day at various steps. Neurologic maturation affects recovery time, and for younger individuals, a more conservative return-to-play protocol based on initial concussion symptom duration has been proposed (FIGURE 1B).16

Return to activity is often supervised by a certified athletic trainer at the athlete’s school. In the event that no athletic trainer is available, patients may be referred to physical therapists with experience in monitoring injured athletes.26 Anyone involved in the patient’s care, including the athlete himself, may use a symptom checklist to monitor recovery.

Although there is no evidence that the ongoing use of a symptom checklist affects the course of recovery, its use is often helpful in identifying specific symptoms that can be managed by means other than physical and cognitive rest—a sleep hygiene program for an individual with lingering difficulty sleeping, for example, or the continued application of ice, heat, and massage for persistent neck pain.

Checklist monitoring may be especially helpful for athletes whose symptoms extend beyond 10 days or who have multiple symptoms. Final clearance once all the steps have been completed requires follow-up with a health care provider.

Is a symptom-free waiting period necessary?

There is no evidence suggesting a need for a symptom-free waiting period before starting the return-to-play protocol.10,27 Because a repeat concussion is most likely within 7 to 10 days of the initial injury,8,9 however, most athletes should not return to contact play during that time frame, regardless of symptom resolution.

It is helpful to have asymptomatic athletes participate in non-contact activity before the 7 to 10 days are up, however. Doing so can help prevent deconditioning and injury upon return to contact sport, as there is evidence of increased risk of lower-extremity injury in the 90 days after concussion.28

What to tell athletes—and parents—about repetitive head trauma

There is growing concern about the long-term risks of concussion and repetitive head impact that may manifest as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and chronic neurocognitive impairment (CNI) later in life. Indeed, some data strongly suggest—but do not definitively prove—a relationship between repetitive head injury and chronic neurodegenerative disease.8-10 You can tell worried patients or parents, however, that the majority of research on CTE and CNI has been based on professional football players.

Studies of long-term effects of soccer heading have shown conflicting results, with some finding cognitive impairment, altered postural control, and anatomic changes of the brain, while others found no effect on encephalopathy, concussion symptoms, or neurocognitive performance.29-36Here, too, most studies showing negative effects of soccer heading involved professional athletes.

Repetitive sub-concussive impact in high school football athletes has been found to induce biochemical changes to the brain,37 but the long-term effects are unknown. And, while concussion in high school athletes has been associated with short-term cognitive impairment, altered neurochemistry, and evidence of increased symptoms on baseline neurocognitive testing,8-10,38 no studies have linked concussion during middle school or high school with CNI. What’s more, a long-term (50-year) follow-up study of individuals who played football in high school found no difference in rates of neurodegenerative disease compared with age-matched controls.39

A new study of high school and college football players (mean age: 17.4 years) presented at the American Academy of Neurology 2016 Sports Concussion Conference in Chicago in July, however, found significant alterations in white matter 6 months post injury.40 The researchers compared 17 athletes with sport-related concussion with matched controls, using diffusion tensor imaging and diffusion kurtosis tensor imaging as biomarkers of brain recovery. The concussed athletes underwent MRI and symptom assessment at 24 hours, 8 days, and 6 months. The controls followed identical protocols.

At the 6-month assessment, there were no differences between the concussed group and the controls in terms of self-reported concussion symptoms, cognition, or balance. However, the concussed athletes had widespread decreased mean diffusivity compared with the controls. Despite the lack of clinical symptoms, the concussed athletes showed significant alterations in white matter “that were related to initial symptom severity ratings,” the authors concluded. These findings have implications both for determination of recovery from concussion and concussion management, they added.40

Although there is no way to eliminate all concussions, limited evidence suggests that improving athletic technique, limiting contact at practices, better enforcement of game rules, and rule changes regarding physical contact may decrease concussion risk.41-43 Many youth sports organizations have developed policies placing restrictions on head impact during practices and games. Studies are ongoing, too, to see if better headgear—or requiring helmets for soccer players—makes a difference.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Sprouse, MD, CAQSM, 203 East Fourth Avenue, Ranson, WV 25438; [email protected].

1. Bryan MA, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Comstock RD, et al. Sports- and recreation-related concussions in US youth. Pediatrics. 2016; June 20 [Epub ahead of print].

2. Arbogast KB, Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, et al. Point of health care entry for youth with concussion within a large pediatric care network. JAMA Pediatr. 2016; May 31 [Epub ahead of print].

3. Mihalik JK, Guskiewicz KM, Valovich McLeod TC, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and concussion-reporting behaviors among high school athletes: a preliminary study. J Ath Tr. 2013;48:645-653.

4. Marar M, McIlvain NM, Fields SK, et al. Epidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sports. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:747.

5. Kontos AP, Elbin RJ, Fazio-Sumrock VC. Incidence of sports-related concussion among youth football players aged 8-12 years. J Pediatr. 2013;163:717-720.

6. Dompier TP, Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, et al. Incidence of concussion during practice and games in youth, high school, and collegiate American football players. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:659-665.

7. Comstock RD, Currie DW, Pierpont LA, et al. An evidence-based discussion of heading the ball and concussions in high school soccer. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:830-837.

8. Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Gammons M, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:15-26.

9. McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:250-258.

10. Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of the evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80:2250-2257.

11. Terwilliger VK, Pratson L, Vaughan CG, et al. Additional post-concussion impact exposure may affect recovery in adolescent athletes. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:761-765.

12. Putukian M, Echemendia R, Dettwiler-Danspeckgruber A. Prospective clinical assessment using Sideline Concussion Assessment Tool-2 testing in the evaluation of sport-related concussion in college athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:36-42.

13. Broglio SP, Macciocchi SN, Ferrara MS. Sensitivity of the concussion assessment battery. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:1050-1057.

14. Randolph C, McCrea M, Barr WB. Is neuropsychological testing useful in the management of sport-related concussion? J Athl Train. 2005;40:139-152.

15. Shrier I. Neuropsychological testing and concussions: a reasoned approach. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:211-213.

16. DeMatteo C, Stazyk K, Singh SK, et al. Development of a conservative protocol to return children and youth to activity following concussive injury. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54:152-163.

17. Broglio SP, Cantu RC, Gioia GA, et al. National Athletic Trainers Association position statement: management of sport concussion. J Athl Train. 2014;49:245-265.

18. Stoller J, Carson JD, Garel A, et al. Do family physicians, emergency department physicians, and pediatricians give consistent sport-related concussion management advice? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:548, 550-552.

19. Lebrun CM, Mrazik M, Prasad AS, et al. Sport concussion knowledge base, clinical practices and needs for continuing medical education: a survey of family physicians and cross-border comparison. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:54-59.

20. Zemek R, Eady K, Moreau K, et al. Knowledge of paediatric concussion among front-line primary care providers. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:475-480.

21. Maerlender A, Rieman W, Lichtenstein J, et al. Programmed physical exertion in recovery from sports-related concussion: a randomized pilot study. Dev Neuropsychol. 2015;40:273-278.

22. Buckley TA, Munkasy BA, Clouse BP. Acute cognitive and physical rest may not improve concussion recovery time. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015; July 24 [Epub ahead of print].

23. Preece MH, Horswill MS, Langlois JA, et al. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375-378.

24. Baker A, Unsworth CA, Lannin NA. Fitness-to-drive after mild traumatic brain injury: mapping the time trajectory of recovery in the acute stages post injury. Accid Anal Prev. 2015;79:50-55.

25. Marshall S, Bayley M, McCullagh S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for mild traumatic brain injury and persistent symptoms. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:257-267.

26. Yorke AM, Littleton S, Alsalaheen BA. Concussion attitudes and beliefs, knowledge, and clinical practice: a survey of physical therapists. Phys Ther. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140598. Accessed January 21, 2016.

27. McCrea M, Guskiewicz K, Randolph C, et al. Effects of a symptom-free waiting period on clinical outcome and risk of reinjury after sport-related concussion. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:876-883.

28. Brooks MA, Peterson K, Biese K, et al. Concussion increases odds of sustaining a lower extremity musculoskeletal injury after return to play among collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:742-747.

29. Witol AD, Webbe FM. Soccer heading frequency predicts neuropsychological deficits. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18:397-417.

30. Haran FJ, Tierney R, Wright WG, et al. Acute changes in postural control after soccer heading. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34:350-354.

31. Lipton ML, Kim N, Zimmerman ME, et al. Soccer heading is associated with white matter microstructural and cognitive abnormalities. Radiology. 2013;268:850-857.

32. Jordan SE, Green GA, Galanty HL, et al. Acute and chronic brain injury in United States national team soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:205-210.

33. Kontos AP, Dolese A, Elbin RJ, et al. Relationship of soccer heading to computerized neurocognitive performance and symptoms among female and male youth soccer players. Brain Inj. 2011;25:1234-1241.

34. Straume-Naesheim TM, Andersen TE, Dvorak J, et al. Effects of heading exposure and previous concussions on neuropsychological performance among Norwegian elite footballers. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:70-77.

35. Stephens R, Rutherford A, Potter D, et al. Neuropsychological impairment as a consequence of football (soccer) play and football heading: a preliminary analysis and report on school students (13-16 years). Child Neuropsychol. 2005;11:513-526.

36. Stephens R, Rutherford A, Potter D, et al. Neuropsychological consequence of soccer play in adolescent UK school team soccer players. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22:295-303.

37. Poole VN, Breedlove EL, Shenk TE, et al. Sub-concussive hit characteristics predict deviant brain metabolism in football athletes. Dev Neuropsychol. 2015;40:12-17.

38. Mannix R, Iverson GL, Maxwell B, et al. Multiple prior concussions are associated with symptoms in high school athletes. Ann Clin Trans Neurol. 2014;1:433-438.

39. Savica R, Parisi JE, Wold LE, et al. High school football and risk of neurodegeneration: a community-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:335-340.

40. Lancaster M, Muftuler T, Olson D, et al. Chronic white matter changes following sport-related concussion measured by diffusion tensor and diffusion kurtosis imaging. Paper presented at: American Academy of Neurology 2016 Sports Concussion Conference; July 8-10, 2016; Chicago, Ill.

41. Kerr ZY, Yeargin SW, Valovich McLeod TC, et al. Comprehensive coach education reduces head impact exposures in American youth football. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(ecollection):e232596711561545.

42. Black AM, Macpherson AK, Hagel BE, et al. Policy change eliminating body checking in non-elite ice hockey leads to a threefold reduction in injury and concussion risk in 11- and 12-year-old players. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:55-61.

43. Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Tackling in youth football. Policy Statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1419-e1430.

› Require athletes who sustain a concussion to wait a minimum of 7 to 10 days before returning to full unrestricted activity. C

› Ensure that any player diagnosed with concussion follows a guided return-to-play progression, supervised by an athletic trainer or physical therapist experienced in post-concussion care. C

› Advise patients who are old enough to drive not to do so for at least 24 hours after a concussion. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Each year in the United States, more than 44 million young people participate in sports activities.1 Yet the number of concussions incurred annually by children and adolescents engaged in sports and recreational play has been underestimated for years, and largely unknown.1,2

Some estimates were based solely on the number of young athletes treated in emergency departments or sports concussion clinics. Others focused only on team players of middle school or high school age, excluding younger children who were hit in the head on playgrounds or during other recreational activities. What’s more, large numbers of concussions—as many as 4 in 10 incurred by high school athletes—were never reported to a coach or medical professional.3

In a new study published in the journal Pediatrics in June, researchers used national databases and current literature to provide what they believe to be “the most accurate and precise estimate of youth concussion” thus far: Between 1.1 and 1.9 million sports- and recreation-related concussions occur among US youth ages 18 or younger annually.1

Among young people playing team sports, concussions are between 2 and 7 times more likely to occur during competitive games than in practice sessions.4-7 Boys on football and ice hockey teams have the highest rates of concussion in young athletes.For overall number of concussions, however, girls on soccer teams are second only to football players.4 Female soccer players are more likely than male soccer players to sustain concussions during equal number of hours of play.4,7

An increase in incidence. The incidence of concussion among young athletes appears to have increased in the past decade, a likely result of greater involvement in team sports, an increasing focus on safeguarding young people from the potential dangers associated with a blow to the brain, and better diagnostic techniques.4,8-10 And a recent study based on data from electronic medical records at a large regional pediatric health care network found that more than three-quarters of young people with sports-related concussions were first seen in a primary care setting.2

With this in mind, we present a comprehensive update of the evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of sport-related concussion. The recommendations we include are consistent with professional association guidelines.8-10 Although we focus on concussion in children and adolescents involved in athletic activities, the principles generally apply to patients of all ages and to concussions that may not be sports related.

Removal from play: A vital first step

Whenever you conduct a physical exam for a young athlete, remind him or her—and the patient’s parents—that after a blow to the head, immediate removal from play is critical. Concussion is caused by a direct or indirect force to the brain that results in a transient disturbance in brain function,8-10 manifested by alterations in neurocognitive and motor function. While the signs and symptoms (TABLE 1)8-10 resolve within 10 days of injury in about 90% of cases, those who incur additional head impact within 24 hours have a higher symptom burden and prolonged recovery period.11 Even without repetitive impact, younger athletes may take longer to recover.8-10

The initial assessment

A child or adolescent who sustains a suspected concussion should be seen by a physician within 24 to 48 hours. Whether the initial assessment occurs in your office or on the sidelines of a game, it is important to confirm the time the incident occurred and the mechanism of injury.

Concussion is diagnosed by a combination of history, physical exam, and objective testing when symptoms or exam findings associated with mild brain trauma—headache, dizziness, light and/or noise sensitivity, among others—closely follow a head injury.8-10 Certain maneuvers—assessing eye movements by asking the athlete to look in various directions, for instance, then to follow a pen or finger as you move it closer to his or her face—may provoke dizziness, headache, or other symptoms of concussion that were not apparent initially.

The differential diagnosis includes cervical musculoskeletal injury, craniofacial injury, epidural and subdural hematoma, heat-related illness, uncomplicated headache and migraine, upper respiratory infection, and vertigo.8-10

Tools aid in diagnosis

Many clinical assessment tools exist to aid in the diagnosis of concussion (TABLE 2).8-10,12-14 Any one of these tools, many of which use combinations of symptom checklists, balance exams, and cognitive assessments, may be included in your evaluation. No single tool has been found to be superior to any other.8-10 A combination of tools may improve diagnostic accuracy, but assessment tools should not be the sole basis used to diagnose or rule out concussion.

Any child or adolescent who had a blow to the head and at least one sign or symptom of concussion should be evaluated as soon as possible and assessed again later that day or the next day if any reason for concern remains.

Neuropsychological (NP) testing may involve computerized tests developed specifically for athletes. Patients may be required to react to objects that appear on a screen, for example, in a way that tests memory, performance, and reaction time. Because cognitive recovery often lags behind symptom resolution, NP testing may identify subtle brain deficits even in athletes who are asymptomatic at rest or with exercise. In general, NP testing has a sensitivity of 71% to 88% for athletes with concussion,10 but it is most beneficial when baseline test results are available. Interpretation of NP testing should be done only by qualified clinicians.

While NP testing may provide additional prognostic information, it should not alter the management of athletes who are symptomatic either at rest or with exercise.15 Nor is NP testing vital, as concussion can be accurately diagnosed and adequately managed without it.

Neuroimaging, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is often used unnecessarily in the initial assessment of a patient who sustained a possible concussion.8-10 In fact, neuroimaging should be reserved for cases in which it is necessary to rule out more serious pathology: intracranial or subdural hematoma or a craniofacial injury, for example, in patients with clinical findings that are red flags. These red flags include focal neurologic deficits, continuing nausea/vomiting, or persistent disorientation (TABLE 3),8-10 or symptoms that worsen or persist beyond a few weeks. In such cases, further evaluation—with MRI of the brain, formal NP testing, and/or referral to a neurologist, physiatrist, or other physician who specializes in concussion care—is indicated.

Concussion management: Rest is key

While there is a dearth of high-quality studies on the management of sport-related concussion across all age groups, standardized protocols for both children and adults have been adopted in most clinical settings.8-10,16,17 The protocols provide a framework for an individualized treatment plan. Yet their use among primary care physicians is inconsistent.18-20

Traditionally, concussion management begins with relative physical and cognitive rest to allow the brain time to recover.8-10 Recent randomized controlled trials have challenged this premise by suggesting that mild to moderate physical activity for post-concussion patients who are mildly symptomatic does not adversely affect recovery.21,22 These studies have significant limitations, however, and further research is needed to provide specific guidance on this aspect of concussion management before it is adopted.

Physical restrictions include organized sports, recreational activity, recess, and physical education classes. Walking is permitted unless it exacerbates symptoms. These restrictions should continue until the patient is symptom-free.

Cognitive restrictions include modifications at school and at home. Once an athlete is able to concentrate and tolerate visual and auditory stimuli, he or she may return to school. But classroom modifications should be considered, possibly including shortened school days, extra time for testing and homework, help with note taking, and restrictions from classes likely to provoke symptoms, such as computer science or music. Limiting use of mobile devices, television viewing, noisy environments, and other possible provocations may help speed symptom resolution. These restrictions, too, should remain in place until the patient is symptom-free.

Driving is often not addressed by physicians managing the care of athletes with concussion, but evidence suggests it should be. A study of patients presenting to the emergency department found that within 24 hours of a concussion diagnosis, individuals had an impaired response to traffic hazards.23,24 And Canadian clinical practice guidelines recommend that athletes with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) avoid driving within the first 24 hours.25

While American guidelines are silent on the question of driving for this patient population, we recommend that athletes with concussion be restricted from driving and engaging in other risky complex tasks, such as welding or shop class, for at least 24 hours. For many athletes diagnosed with concussion, driving restrictions of longer duration may be necessary based on their symptom profile and neurocognitive test results. Continued dizziness or visual deficits would pose a greater risk than fatigue or short-term memory loss, for example.

Overseeing the return to play

Return-to-activity progression follows a stepwise protocol, with 6 steps that the injured athlete must complete before resuming full activity (FIGURE 1A).8-10 This stepwise progression begins only when athletes are symptom free, even during provocative maneuvers; have had a normal neurologic exam, are back to school full time with no restriction; are off any medications prescribed for concussion symptoms (TABLE 4),8-10 and when neurocognitive testing, if performed, is back to baseline. If an athlete develops symptoms at any stage of the progression, rest is required until he or she remains asymptomatic for at least 24 hours. The progression is then restarted at the last stage at which the patient was symptom free.

Some individualization, of course, is recommended here, too. Younger athletes and those with a prior history of concussion may require 10 days or more to complete all the steps, allowing an extra day at various steps. Neurologic maturation affects recovery time, and for younger individuals, a more conservative return-to-play protocol based on initial concussion symptom duration has been proposed (FIGURE 1B).16

Return to activity is often supervised by a certified athletic trainer at the athlete’s school. In the event that no athletic trainer is available, patients may be referred to physical therapists with experience in monitoring injured athletes.26 Anyone involved in the patient’s care, including the athlete himself, may use a symptom checklist to monitor recovery.

Although there is no evidence that the ongoing use of a symptom checklist affects the course of recovery, its use is often helpful in identifying specific symptoms that can be managed by means other than physical and cognitive rest—a sleep hygiene program for an individual with lingering difficulty sleeping, for example, or the continued application of ice, heat, and massage for persistent neck pain.

Checklist monitoring may be especially helpful for athletes whose symptoms extend beyond 10 days or who have multiple symptoms. Final clearance once all the steps have been completed requires follow-up with a health care provider.

Is a symptom-free waiting period necessary?

There is no evidence suggesting a need for a symptom-free waiting period before starting the return-to-play protocol.10,27 Because a repeat concussion is most likely within 7 to 10 days of the initial injury,8,9 however, most athletes should not return to contact play during that time frame, regardless of symptom resolution.

It is helpful to have asymptomatic athletes participate in non-contact activity before the 7 to 10 days are up, however. Doing so can help prevent deconditioning and injury upon return to contact sport, as there is evidence of increased risk of lower-extremity injury in the 90 days after concussion.28

What to tell athletes—and parents—about repetitive head trauma

There is growing concern about the long-term risks of concussion and repetitive head impact that may manifest as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and chronic neurocognitive impairment (CNI) later in life. Indeed, some data strongly suggest—but do not definitively prove—a relationship between repetitive head injury and chronic neurodegenerative disease.8-10 You can tell worried patients or parents, however, that the majority of research on CTE and CNI has been based on professional football players.

Studies of long-term effects of soccer heading have shown conflicting results, with some finding cognitive impairment, altered postural control, and anatomic changes of the brain, while others found no effect on encephalopathy, concussion symptoms, or neurocognitive performance.29-36Here, too, most studies showing negative effects of soccer heading involved professional athletes.

Repetitive sub-concussive impact in high school football athletes has been found to induce biochemical changes to the brain,37 but the long-term effects are unknown. And, while concussion in high school athletes has been associated with short-term cognitive impairment, altered neurochemistry, and evidence of increased symptoms on baseline neurocognitive testing,8-10,38 no studies have linked concussion during middle school or high school with CNI. What’s more, a long-term (50-year) follow-up study of individuals who played football in high school found no difference in rates of neurodegenerative disease compared with age-matched controls.39

A new study of high school and college football players (mean age: 17.4 years) presented at the American Academy of Neurology 2016 Sports Concussion Conference in Chicago in July, however, found significant alterations in white matter 6 months post injury.40 The researchers compared 17 athletes with sport-related concussion with matched controls, using diffusion tensor imaging and diffusion kurtosis tensor imaging as biomarkers of brain recovery. The concussed athletes underwent MRI and symptom assessment at 24 hours, 8 days, and 6 months. The controls followed identical protocols.

At the 6-month assessment, there were no differences between the concussed group and the controls in terms of self-reported concussion symptoms, cognition, or balance. However, the concussed athletes had widespread decreased mean diffusivity compared with the controls. Despite the lack of clinical symptoms, the concussed athletes showed significant alterations in white matter “that were related to initial symptom severity ratings,” the authors concluded. These findings have implications both for determination of recovery from concussion and concussion management, they added.40

Although there is no way to eliminate all concussions, limited evidence suggests that improving athletic technique, limiting contact at practices, better enforcement of game rules, and rule changes regarding physical contact may decrease concussion risk.41-43 Many youth sports organizations have developed policies placing restrictions on head impact during practices and games. Studies are ongoing, too, to see if better headgear—or requiring helmets for soccer players—makes a difference.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Sprouse, MD, CAQSM, 203 East Fourth Avenue, Ranson, WV 25438; [email protected].

› Require athletes who sustain a concussion to wait a minimum of 7 to 10 days before returning to full unrestricted activity. C

› Ensure that any player diagnosed with concussion follows a guided return-to-play progression, supervised by an athletic trainer or physical therapist experienced in post-concussion care. C

› Advise patients who are old enough to drive not to do so for at least 24 hours after a concussion. B

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Each year in the United States, more than 44 million young people participate in sports activities.1 Yet the number of concussions incurred annually by children and adolescents engaged in sports and recreational play has been underestimated for years, and largely unknown.1,2

Some estimates were based solely on the number of young athletes treated in emergency departments or sports concussion clinics. Others focused only on team players of middle school or high school age, excluding younger children who were hit in the head on playgrounds or during other recreational activities. What’s more, large numbers of concussions—as many as 4 in 10 incurred by high school athletes—were never reported to a coach or medical professional.3

In a new study published in the journal Pediatrics in June, researchers used national databases and current literature to provide what they believe to be “the most accurate and precise estimate of youth concussion” thus far: Between 1.1 and 1.9 million sports- and recreation-related concussions occur among US youth ages 18 or younger annually.1

Among young people playing team sports, concussions are between 2 and 7 times more likely to occur during competitive games than in practice sessions.4-7 Boys on football and ice hockey teams have the highest rates of concussion in young athletes.For overall number of concussions, however, girls on soccer teams are second only to football players.4 Female soccer players are more likely than male soccer players to sustain concussions during equal number of hours of play.4,7

An increase in incidence. The incidence of concussion among young athletes appears to have increased in the past decade, a likely result of greater involvement in team sports, an increasing focus on safeguarding young people from the potential dangers associated with a blow to the brain, and better diagnostic techniques.4,8-10 And a recent study based on data from electronic medical records at a large regional pediatric health care network found that more than three-quarters of young people with sports-related concussions were first seen in a primary care setting.2

With this in mind, we present a comprehensive update of the evidence regarding the diagnosis and management of sport-related concussion. The recommendations we include are consistent with professional association guidelines.8-10 Although we focus on concussion in children and adolescents involved in athletic activities, the principles generally apply to patients of all ages and to concussions that may not be sports related.

Removal from play: A vital first step

Whenever you conduct a physical exam for a young athlete, remind him or her—and the patient’s parents—that after a blow to the head, immediate removal from play is critical. Concussion is caused by a direct or indirect force to the brain that results in a transient disturbance in brain function,8-10 manifested by alterations in neurocognitive and motor function. While the signs and symptoms (TABLE 1)8-10 resolve within 10 days of injury in about 90% of cases, those who incur additional head impact within 24 hours have a higher symptom burden and prolonged recovery period.11 Even without repetitive impact, younger athletes may take longer to recover.8-10

The initial assessment

A child or adolescent who sustains a suspected concussion should be seen by a physician within 24 to 48 hours. Whether the initial assessment occurs in your office or on the sidelines of a game, it is important to confirm the time the incident occurred and the mechanism of injury.

Concussion is diagnosed by a combination of history, physical exam, and objective testing when symptoms or exam findings associated with mild brain trauma—headache, dizziness, light and/or noise sensitivity, among others—closely follow a head injury.8-10 Certain maneuvers—assessing eye movements by asking the athlete to look in various directions, for instance, then to follow a pen or finger as you move it closer to his or her face—may provoke dizziness, headache, or other symptoms of concussion that were not apparent initially.

The differential diagnosis includes cervical musculoskeletal injury, craniofacial injury, epidural and subdural hematoma, heat-related illness, uncomplicated headache and migraine, upper respiratory infection, and vertigo.8-10

Tools aid in diagnosis

Many clinical assessment tools exist to aid in the diagnosis of concussion (TABLE 2).8-10,12-14 Any one of these tools, many of which use combinations of symptom checklists, balance exams, and cognitive assessments, may be included in your evaluation. No single tool has been found to be superior to any other.8-10 A combination of tools may improve diagnostic accuracy, but assessment tools should not be the sole basis used to diagnose or rule out concussion.

Any child or adolescent who had a blow to the head and at least one sign or symptom of concussion should be evaluated as soon as possible and assessed again later that day or the next day if any reason for concern remains.

Neuropsychological (NP) testing may involve computerized tests developed specifically for athletes. Patients may be required to react to objects that appear on a screen, for example, in a way that tests memory, performance, and reaction time. Because cognitive recovery often lags behind symptom resolution, NP testing may identify subtle brain deficits even in athletes who are asymptomatic at rest or with exercise. In general, NP testing has a sensitivity of 71% to 88% for athletes with concussion,10 but it is most beneficial when baseline test results are available. Interpretation of NP testing should be done only by qualified clinicians.

While NP testing may provide additional prognostic information, it should not alter the management of athletes who are symptomatic either at rest or with exercise.15 Nor is NP testing vital, as concussion can be accurately diagnosed and adequately managed without it.

Neuroimaging, including computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), is often used unnecessarily in the initial assessment of a patient who sustained a possible concussion.8-10 In fact, neuroimaging should be reserved for cases in which it is necessary to rule out more serious pathology: intracranial or subdural hematoma or a craniofacial injury, for example, in patients with clinical findings that are red flags. These red flags include focal neurologic deficits, continuing nausea/vomiting, or persistent disorientation (TABLE 3),8-10 or symptoms that worsen or persist beyond a few weeks. In such cases, further evaluation—with MRI of the brain, formal NP testing, and/or referral to a neurologist, physiatrist, or other physician who specializes in concussion care—is indicated.

Concussion management: Rest is key

While there is a dearth of high-quality studies on the management of sport-related concussion across all age groups, standardized protocols for both children and adults have been adopted in most clinical settings.8-10,16,17 The protocols provide a framework for an individualized treatment plan. Yet their use among primary care physicians is inconsistent.18-20

Traditionally, concussion management begins with relative physical and cognitive rest to allow the brain time to recover.8-10 Recent randomized controlled trials have challenged this premise by suggesting that mild to moderate physical activity for post-concussion patients who are mildly symptomatic does not adversely affect recovery.21,22 These studies have significant limitations, however, and further research is needed to provide specific guidance on this aspect of concussion management before it is adopted.

Physical restrictions include organized sports, recreational activity, recess, and physical education classes. Walking is permitted unless it exacerbates symptoms. These restrictions should continue until the patient is symptom-free.

Cognitive restrictions include modifications at school and at home. Once an athlete is able to concentrate and tolerate visual and auditory stimuli, he or she may return to school. But classroom modifications should be considered, possibly including shortened school days, extra time for testing and homework, help with note taking, and restrictions from classes likely to provoke symptoms, such as computer science or music. Limiting use of mobile devices, television viewing, noisy environments, and other possible provocations may help speed symptom resolution. These restrictions, too, should remain in place until the patient is symptom-free.

Driving is often not addressed by physicians managing the care of athletes with concussion, but evidence suggests it should be. A study of patients presenting to the emergency department found that within 24 hours of a concussion diagnosis, individuals had an impaired response to traffic hazards.23,24 And Canadian clinical practice guidelines recommend that athletes with mild traumatic brain injury (TBI) avoid driving within the first 24 hours.25

While American guidelines are silent on the question of driving for this patient population, we recommend that athletes with concussion be restricted from driving and engaging in other risky complex tasks, such as welding or shop class, for at least 24 hours. For many athletes diagnosed with concussion, driving restrictions of longer duration may be necessary based on their symptom profile and neurocognitive test results. Continued dizziness or visual deficits would pose a greater risk than fatigue or short-term memory loss, for example.

Overseeing the return to play

Return-to-activity progression follows a stepwise protocol, with 6 steps that the injured athlete must complete before resuming full activity (FIGURE 1A).8-10 This stepwise progression begins only when athletes are symptom free, even during provocative maneuvers; have had a normal neurologic exam, are back to school full time with no restriction; are off any medications prescribed for concussion symptoms (TABLE 4),8-10 and when neurocognitive testing, if performed, is back to baseline. If an athlete develops symptoms at any stage of the progression, rest is required until he or she remains asymptomatic for at least 24 hours. The progression is then restarted at the last stage at which the patient was symptom free.

Some individualization, of course, is recommended here, too. Younger athletes and those with a prior history of concussion may require 10 days or more to complete all the steps, allowing an extra day at various steps. Neurologic maturation affects recovery time, and for younger individuals, a more conservative return-to-play protocol based on initial concussion symptom duration has been proposed (FIGURE 1B).16

Return to activity is often supervised by a certified athletic trainer at the athlete’s school. In the event that no athletic trainer is available, patients may be referred to physical therapists with experience in monitoring injured athletes.26 Anyone involved in the patient’s care, including the athlete himself, may use a symptom checklist to monitor recovery.

Although there is no evidence that the ongoing use of a symptom checklist affects the course of recovery, its use is often helpful in identifying specific symptoms that can be managed by means other than physical and cognitive rest—a sleep hygiene program for an individual with lingering difficulty sleeping, for example, or the continued application of ice, heat, and massage for persistent neck pain.

Checklist monitoring may be especially helpful for athletes whose symptoms extend beyond 10 days or who have multiple symptoms. Final clearance once all the steps have been completed requires follow-up with a health care provider.

Is a symptom-free waiting period necessary?

There is no evidence suggesting a need for a symptom-free waiting period before starting the return-to-play protocol.10,27 Because a repeat concussion is most likely within 7 to 10 days of the initial injury,8,9 however, most athletes should not return to contact play during that time frame, regardless of symptom resolution.

It is helpful to have asymptomatic athletes participate in non-contact activity before the 7 to 10 days are up, however. Doing so can help prevent deconditioning and injury upon return to contact sport, as there is evidence of increased risk of lower-extremity injury in the 90 days after concussion.28

What to tell athletes—and parents—about repetitive head trauma

There is growing concern about the long-term risks of concussion and repetitive head impact that may manifest as chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) and chronic neurocognitive impairment (CNI) later in life. Indeed, some data strongly suggest—but do not definitively prove—a relationship between repetitive head injury and chronic neurodegenerative disease.8-10 You can tell worried patients or parents, however, that the majority of research on CTE and CNI has been based on professional football players.

Studies of long-term effects of soccer heading have shown conflicting results, with some finding cognitive impairment, altered postural control, and anatomic changes of the brain, while others found no effect on encephalopathy, concussion symptoms, or neurocognitive performance.29-36Here, too, most studies showing negative effects of soccer heading involved professional athletes.

Repetitive sub-concussive impact in high school football athletes has been found to induce biochemical changes to the brain,37 but the long-term effects are unknown. And, while concussion in high school athletes has been associated with short-term cognitive impairment, altered neurochemistry, and evidence of increased symptoms on baseline neurocognitive testing,8-10,38 no studies have linked concussion during middle school or high school with CNI. What’s more, a long-term (50-year) follow-up study of individuals who played football in high school found no difference in rates of neurodegenerative disease compared with age-matched controls.39

A new study of high school and college football players (mean age: 17.4 years) presented at the American Academy of Neurology 2016 Sports Concussion Conference in Chicago in July, however, found significant alterations in white matter 6 months post injury.40 The researchers compared 17 athletes with sport-related concussion with matched controls, using diffusion tensor imaging and diffusion kurtosis tensor imaging as biomarkers of brain recovery. The concussed athletes underwent MRI and symptom assessment at 24 hours, 8 days, and 6 months. The controls followed identical protocols.

At the 6-month assessment, there were no differences between the concussed group and the controls in terms of self-reported concussion symptoms, cognition, or balance. However, the concussed athletes had widespread decreased mean diffusivity compared with the controls. Despite the lack of clinical symptoms, the concussed athletes showed significant alterations in white matter “that were related to initial symptom severity ratings,” the authors concluded. These findings have implications both for determination of recovery from concussion and concussion management, they added.40

Although there is no way to eliminate all concussions, limited evidence suggests that improving athletic technique, limiting contact at practices, better enforcement of game rules, and rule changes regarding physical contact may decrease concussion risk.41-43 Many youth sports organizations have developed policies placing restrictions on head impact during practices and games. Studies are ongoing, too, to see if better headgear—or requiring helmets for soccer players—makes a difference.

CORRESPONDENCE

Ryan A. Sprouse, MD, CAQSM, 203 East Fourth Avenue, Ranson, WV 25438; [email protected].

1. Bryan MA, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Comstock RD, et al. Sports- and recreation-related concussions in US youth. Pediatrics. 2016; June 20 [Epub ahead of print].

2. Arbogast KB, Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, et al. Point of health care entry for youth with concussion within a large pediatric care network. JAMA Pediatr. 2016; May 31 [Epub ahead of print].

3. Mihalik JK, Guskiewicz KM, Valovich McLeod TC, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and concussion-reporting behaviors among high school athletes: a preliminary study. J Ath Tr. 2013;48:645-653.

4. Marar M, McIlvain NM, Fields SK, et al. Epidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sports. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:747.

5. Kontos AP, Elbin RJ, Fazio-Sumrock VC. Incidence of sports-related concussion among youth football players aged 8-12 years. J Pediatr. 2013;163:717-720.

6. Dompier TP, Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, et al. Incidence of concussion during practice and games in youth, high school, and collegiate American football players. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:659-665.

7. Comstock RD, Currie DW, Pierpont LA, et al. An evidence-based discussion of heading the ball and concussions in high school soccer. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:830-837.

8. Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Gammons M, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:15-26.

9. McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:250-258.

10. Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of the evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80:2250-2257.

11. Terwilliger VK, Pratson L, Vaughan CG, et al. Additional post-concussion impact exposure may affect recovery in adolescent athletes. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:761-765.

12. Putukian M, Echemendia R, Dettwiler-Danspeckgruber A. Prospective clinical assessment using Sideline Concussion Assessment Tool-2 testing in the evaluation of sport-related concussion in college athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:36-42.

13. Broglio SP, Macciocchi SN, Ferrara MS. Sensitivity of the concussion assessment battery. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:1050-1057.

14. Randolph C, McCrea M, Barr WB. Is neuropsychological testing useful in the management of sport-related concussion? J Athl Train. 2005;40:139-152.

15. Shrier I. Neuropsychological testing and concussions: a reasoned approach. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:211-213.

16. DeMatteo C, Stazyk K, Singh SK, et al. Development of a conservative protocol to return children and youth to activity following concussive injury. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54:152-163.

17. Broglio SP, Cantu RC, Gioia GA, et al. National Athletic Trainers Association position statement: management of sport concussion. J Athl Train. 2014;49:245-265.

18. Stoller J, Carson JD, Garel A, et al. Do family physicians, emergency department physicians, and pediatricians give consistent sport-related concussion management advice? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:548, 550-552.

19. Lebrun CM, Mrazik M, Prasad AS, et al. Sport concussion knowledge base, clinical practices and needs for continuing medical education: a survey of family physicians and cross-border comparison. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:54-59.

20. Zemek R, Eady K, Moreau K, et al. Knowledge of paediatric concussion among front-line primary care providers. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:475-480.

21. Maerlender A, Rieman W, Lichtenstein J, et al. Programmed physical exertion in recovery from sports-related concussion: a randomized pilot study. Dev Neuropsychol. 2015;40:273-278.

22. Buckley TA, Munkasy BA, Clouse BP. Acute cognitive and physical rest may not improve concussion recovery time. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015; July 24 [Epub ahead of print].

23. Preece MH, Horswill MS, Langlois JA, et al. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375-378.

24. Baker A, Unsworth CA, Lannin NA. Fitness-to-drive after mild traumatic brain injury: mapping the time trajectory of recovery in the acute stages post injury. Accid Anal Prev. 2015;79:50-55.

25. Marshall S, Bayley M, McCullagh S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for mild traumatic brain injury and persistent symptoms. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:257-267.

26. Yorke AM, Littleton S, Alsalaheen BA. Concussion attitudes and beliefs, knowledge, and clinical practice: a survey of physical therapists. Phys Ther. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140598. Accessed January 21, 2016.

27. McCrea M, Guskiewicz K, Randolph C, et al. Effects of a symptom-free waiting period on clinical outcome and risk of reinjury after sport-related concussion. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:876-883.

28. Brooks MA, Peterson K, Biese K, et al. Concussion increases odds of sustaining a lower extremity musculoskeletal injury after return to play among collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:742-747.

29. Witol AD, Webbe FM. Soccer heading frequency predicts neuropsychological deficits. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18:397-417.

30. Haran FJ, Tierney R, Wright WG, et al. Acute changes in postural control after soccer heading. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34:350-354.

31. Lipton ML, Kim N, Zimmerman ME, et al. Soccer heading is associated with white matter microstructural and cognitive abnormalities. Radiology. 2013;268:850-857.

32. Jordan SE, Green GA, Galanty HL, et al. Acute and chronic brain injury in United States national team soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:205-210.

33. Kontos AP, Dolese A, Elbin RJ, et al. Relationship of soccer heading to computerized neurocognitive performance and symptoms among female and male youth soccer players. Brain Inj. 2011;25:1234-1241.

34. Straume-Naesheim TM, Andersen TE, Dvorak J, et al. Effects of heading exposure and previous concussions on neuropsychological performance among Norwegian elite footballers. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:70-77.

35. Stephens R, Rutherford A, Potter D, et al. Neuropsychological impairment as a consequence of football (soccer) play and football heading: a preliminary analysis and report on school students (13-16 years). Child Neuropsychol. 2005;11:513-526.

36. Stephens R, Rutherford A, Potter D, et al. Neuropsychological consequence of soccer play in adolescent UK school team soccer players. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22:295-303.

37. Poole VN, Breedlove EL, Shenk TE, et al. Sub-concussive hit characteristics predict deviant brain metabolism in football athletes. Dev Neuropsychol. 2015;40:12-17.

38. Mannix R, Iverson GL, Maxwell B, et al. Multiple prior concussions are associated with symptoms in high school athletes. Ann Clin Trans Neurol. 2014;1:433-438.

39. Savica R, Parisi JE, Wold LE, et al. High school football and risk of neurodegeneration: a community-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:335-340.

40. Lancaster M, Muftuler T, Olson D, et al. Chronic white matter changes following sport-related concussion measured by diffusion tensor and diffusion kurtosis imaging. Paper presented at: American Academy of Neurology 2016 Sports Concussion Conference; July 8-10, 2016; Chicago, Ill.

41. Kerr ZY, Yeargin SW, Valovich McLeod TC, et al. Comprehensive coach education reduces head impact exposures in American youth football. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(ecollection):e232596711561545.

42. Black AM, Macpherson AK, Hagel BE, et al. Policy change eliminating body checking in non-elite ice hockey leads to a threefold reduction in injury and concussion risk in 11- and 12-year-old players. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:55-61.

43. Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Tackling in youth football. Policy Statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1419-e1430.

1. Bryan MA, Rowhani-Rahbar A, Comstock RD, et al. Sports- and recreation-related concussions in US youth. Pediatrics. 2016; June 20 [Epub ahead of print].

2. Arbogast KB, Curry AE, Pfeiffer MR, et al. Point of health care entry for youth with concussion within a large pediatric care network. JAMA Pediatr. 2016; May 31 [Epub ahead of print].

3. Mihalik JK, Guskiewicz KM, Valovich McLeod TC, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and concussion-reporting behaviors among high school athletes: a preliminary study. J Ath Tr. 2013;48:645-653.

4. Marar M, McIlvain NM, Fields SK, et al. Epidemiology of concussions among United States high school athletes in 20 sports. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:747.

5. Kontos AP, Elbin RJ, Fazio-Sumrock VC. Incidence of sports-related concussion among youth football players aged 8-12 years. J Pediatr. 2013;163:717-720.

6. Dompier TP, Kerr ZY, Marshall SW, et al. Incidence of concussion during practice and games in youth, high school, and collegiate American football players. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:659-665.

7. Comstock RD, Currie DW, Pierpont LA, et al. An evidence-based discussion of heading the ball and concussions in high school soccer. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:830-837.

8. Harmon KG, Drezner JA, Gammons M, et al. American Medical Society for Sports Medicine position statement: concussion in sport. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:15-26.

9. McCrory P, Meeuwisse WH, Aubry M, et al. Consensus statement on concussion in sport: the 4th International Conference on Concussion in Sport held in Zurich, November 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:250-258.

10. Giza CC, Kutcher JS, Ashwal S, et al. Summary of the evidence-based guideline update: evaluation and management of concussion in sports: report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2013;80:2250-2257.

11. Terwilliger VK, Pratson L, Vaughan CG, et al. Additional post-concussion impact exposure may affect recovery in adolescent athletes. J Neurotrauma. 2016;33:761-765.

12. Putukian M, Echemendia R, Dettwiler-Danspeckgruber A. Prospective clinical assessment using Sideline Concussion Assessment Tool-2 testing in the evaluation of sport-related concussion in college athletes. Clin J Sport Med. 2015;25:36-42.

13. Broglio SP, Macciocchi SN, Ferrara MS. Sensitivity of the concussion assessment battery. Neurosurgery. 2007;60:1050-1057.

14. Randolph C, McCrea M, Barr WB. Is neuropsychological testing useful in the management of sport-related concussion? J Athl Train. 2005;40:139-152.

15. Shrier I. Neuropsychological testing and concussions: a reasoned approach. Clin J Sport Med. 2012;22:211-213.

16. DeMatteo C, Stazyk K, Singh SK, et al. Development of a conservative protocol to return children and youth to activity following concussive injury. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2015;54:152-163.

17. Broglio SP, Cantu RC, Gioia GA, et al. National Athletic Trainers Association position statement: management of sport concussion. J Athl Train. 2014;49:245-265.

18. Stoller J, Carson JD, Garel A, et al. Do family physicians, emergency department physicians, and pediatricians give consistent sport-related concussion management advice? Can Fam Physician. 2014;60:548, 550-552.

19. Lebrun CM, Mrazik M, Prasad AS, et al. Sport concussion knowledge base, clinical practices and needs for continuing medical education: a survey of family physicians and cross-border comparison. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:54-59.

20. Zemek R, Eady K, Moreau K, et al. Knowledge of paediatric concussion among front-line primary care providers. Paediatr Child Health. 2014;19:475-480.

21. Maerlender A, Rieman W, Lichtenstein J, et al. Programmed physical exertion in recovery from sports-related concussion: a randomized pilot study. Dev Neuropsychol. 2015;40:273-278.

22. Buckley TA, Munkasy BA, Clouse BP. Acute cognitive and physical rest may not improve concussion recovery time. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2015; July 24 [Epub ahead of print].

23. Preece MH, Horswill MS, Langlois JA, et al. The epidemiology and impact of traumatic brain injury: a brief overview. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2006;21:375-378.

24. Baker A, Unsworth CA, Lannin NA. Fitness-to-drive after mild traumatic brain injury: mapping the time trajectory of recovery in the acute stages post injury. Accid Anal Prev. 2015;79:50-55.

25. Marshall S, Bayley M, McCullagh S, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for mild traumatic brain injury and persistent symptoms. Can Fam Physician. 2012;58:257-267.

26. Yorke AM, Littleton S, Alsalaheen BA. Concussion attitudes and beliefs, knowledge, and clinical practice: a survey of physical therapists. Phys Ther. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.2522/ptj.20140598. Accessed January 21, 2016.

27. McCrea M, Guskiewicz K, Randolph C, et al. Effects of a symptom-free waiting period on clinical outcome and risk of reinjury after sport-related concussion. Neurosurgery. 2009;65:876-883.

28. Brooks MA, Peterson K, Biese K, et al. Concussion increases odds of sustaining a lower extremity musculoskeletal injury after return to play among collegiate athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44:742-747.

29. Witol AD, Webbe FM. Soccer heading frequency predicts neuropsychological deficits. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2003;18:397-417.

30. Haran FJ, Tierney R, Wright WG, et al. Acute changes in postural control after soccer heading. Int J Sports Med. 2013;34:350-354.

31. Lipton ML, Kim N, Zimmerman ME, et al. Soccer heading is associated with white matter microstructural and cognitive abnormalities. Radiology. 2013;268:850-857.

32. Jordan SE, Green GA, Galanty HL, et al. Acute and chronic brain injury in United States national team soccer players. Am J Sports Med. 1996;24:205-210.

33. Kontos AP, Dolese A, Elbin RJ, et al. Relationship of soccer heading to computerized neurocognitive performance and symptoms among female and male youth soccer players. Brain Inj. 2011;25:1234-1241.

34. Straume-Naesheim TM, Andersen TE, Dvorak J, et al. Effects of heading exposure and previous concussions on neuropsychological performance among Norwegian elite footballers. Br J Sports Med. 2005;39:70-77.

35. Stephens R, Rutherford A, Potter D, et al. Neuropsychological impairment as a consequence of football (soccer) play and football heading: a preliminary analysis and report on school students (13-16 years). Child Neuropsychol. 2005;11:513-526.

36. Stephens R, Rutherford A, Potter D, et al. Neuropsychological consequence of soccer play in adolescent UK school team soccer players. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2010;22:295-303.

37. Poole VN, Breedlove EL, Shenk TE, et al. Sub-concussive hit characteristics predict deviant brain metabolism in football athletes. Dev Neuropsychol. 2015;40:12-17.

38. Mannix R, Iverson GL, Maxwell B, et al. Multiple prior concussions are associated with symptoms in high school athletes. Ann Clin Trans Neurol. 2014;1:433-438.

39. Savica R, Parisi JE, Wold LE, et al. High school football and risk of neurodegeneration: a community-based study. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87:335-340.

40. Lancaster M, Muftuler T, Olson D, et al. Chronic white matter changes following sport-related concussion measured by diffusion tensor and diffusion kurtosis imaging. Paper presented at: American Academy of Neurology 2016 Sports Concussion Conference; July 8-10, 2016; Chicago, Ill.

41. Kerr ZY, Yeargin SW, Valovich McLeod TC, et al. Comprehensive coach education reduces head impact exposures in American youth football. Orthop J Sports Med. 2015;3(ecollection):e232596711561545.

42. Black AM, Macpherson AK, Hagel BE, et al. Policy change eliminating body checking in non-elite ice hockey leads to a threefold reduction in injury and concussion risk in 11- and 12-year-old players. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:55-61.

43. Council on Sports Medicine and Fitness. Tackling in youth football. Policy Statement of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2015;136:e1419-e1430.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2016;65(8):538-544,546.