User login

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common childhood neurodevelopmental disorder, affecting 8% to 12% of school-aged children in the United States1-3 with significant impairments that often persist into adulthood.4-8 Current guidelines recommend stimulant medication and/or behavioral therapies as first-line treatments for ADHD.9,10 There is a wealth of evidence on the efficacy of stimulants in ADHD, with the most significant effects noted on core ADHD symptoms.11,12 Additional evidence links stimulants to decreased long-term negative outcomes, including reduced school absences and grade retention,13 as well as modestly but significantly improved reading and math scores.14 Other studies have reported that individuals with ADHD who receive medication have decreased criminality,15,16 motor vehicle accidents,17,18 injuries,19 substance abuse,20-22 and risk for subsequent and concurrent depression.23 Therefore, the evidence suggests that consistent medication treatment helps improve outcomes for individuals with ADHD.

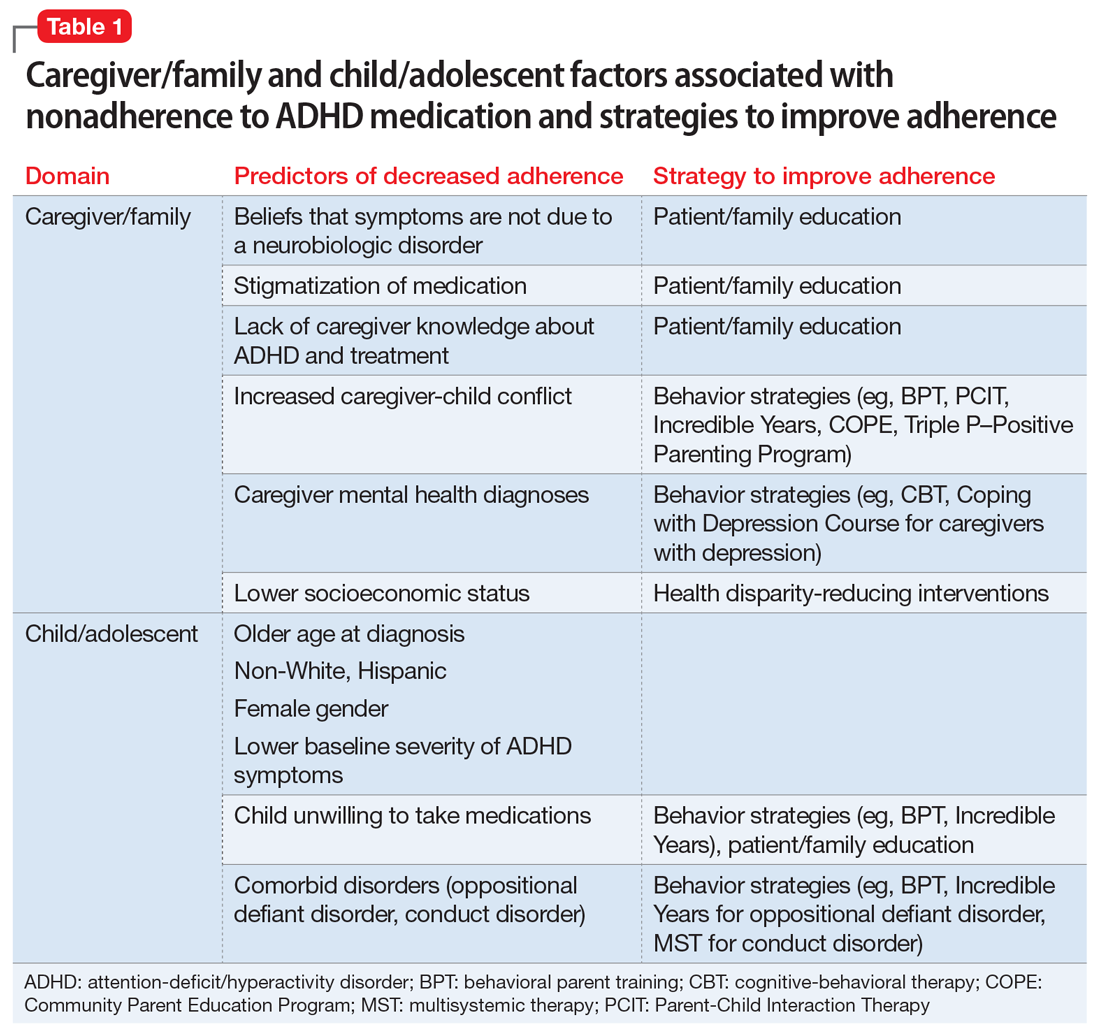

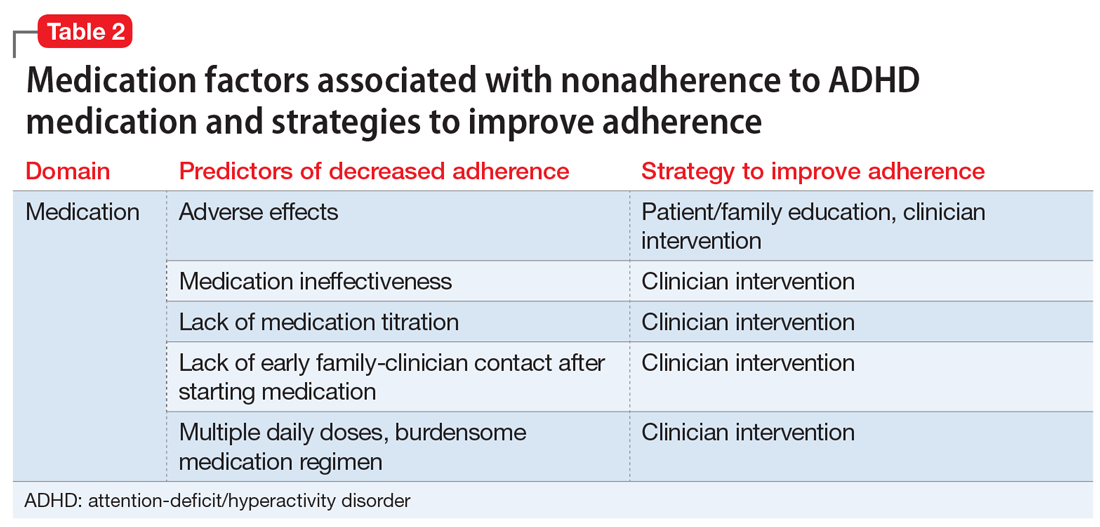

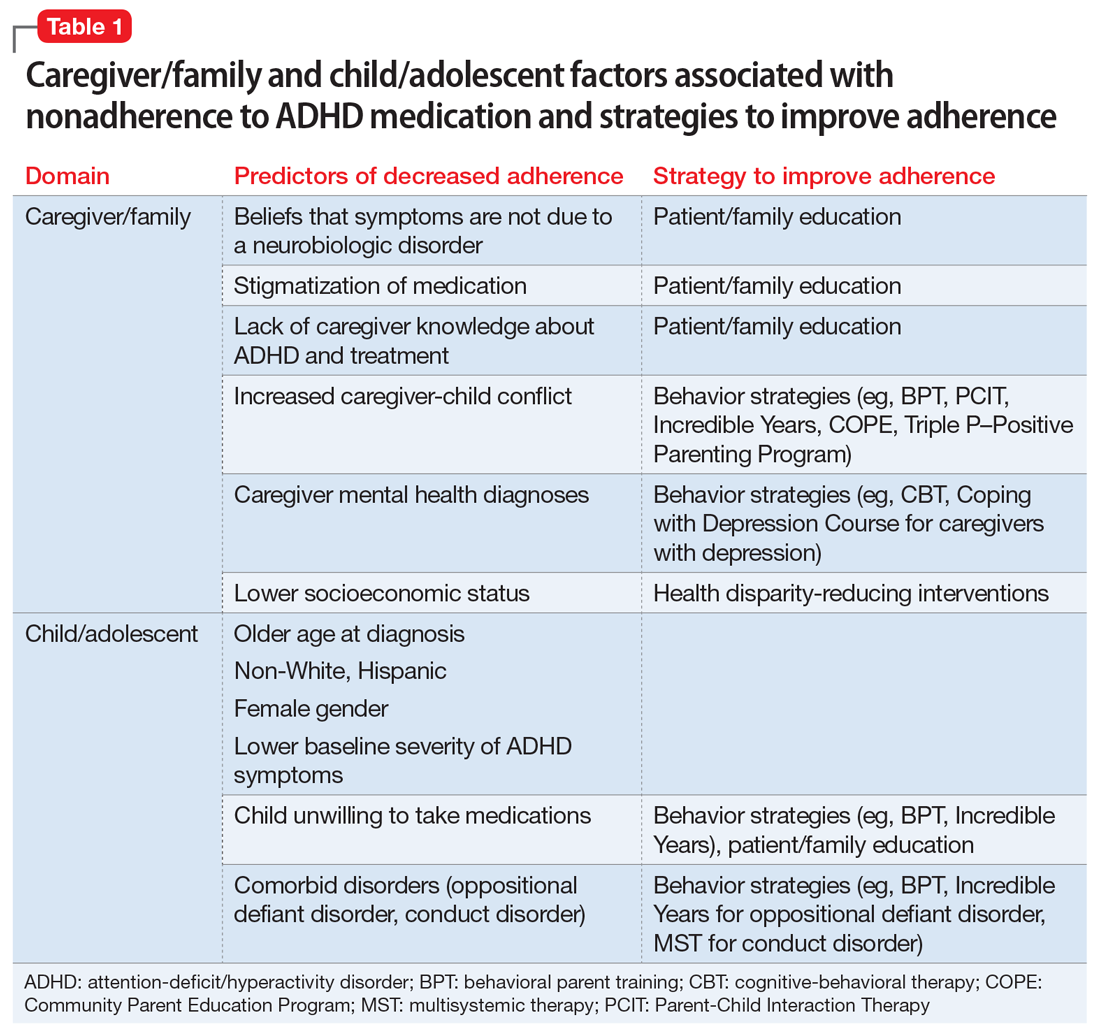

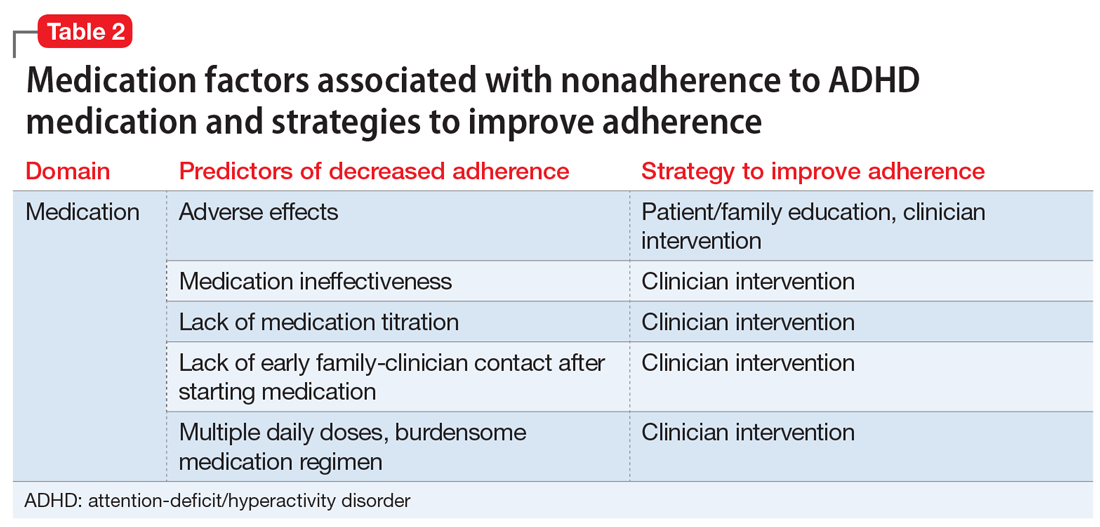

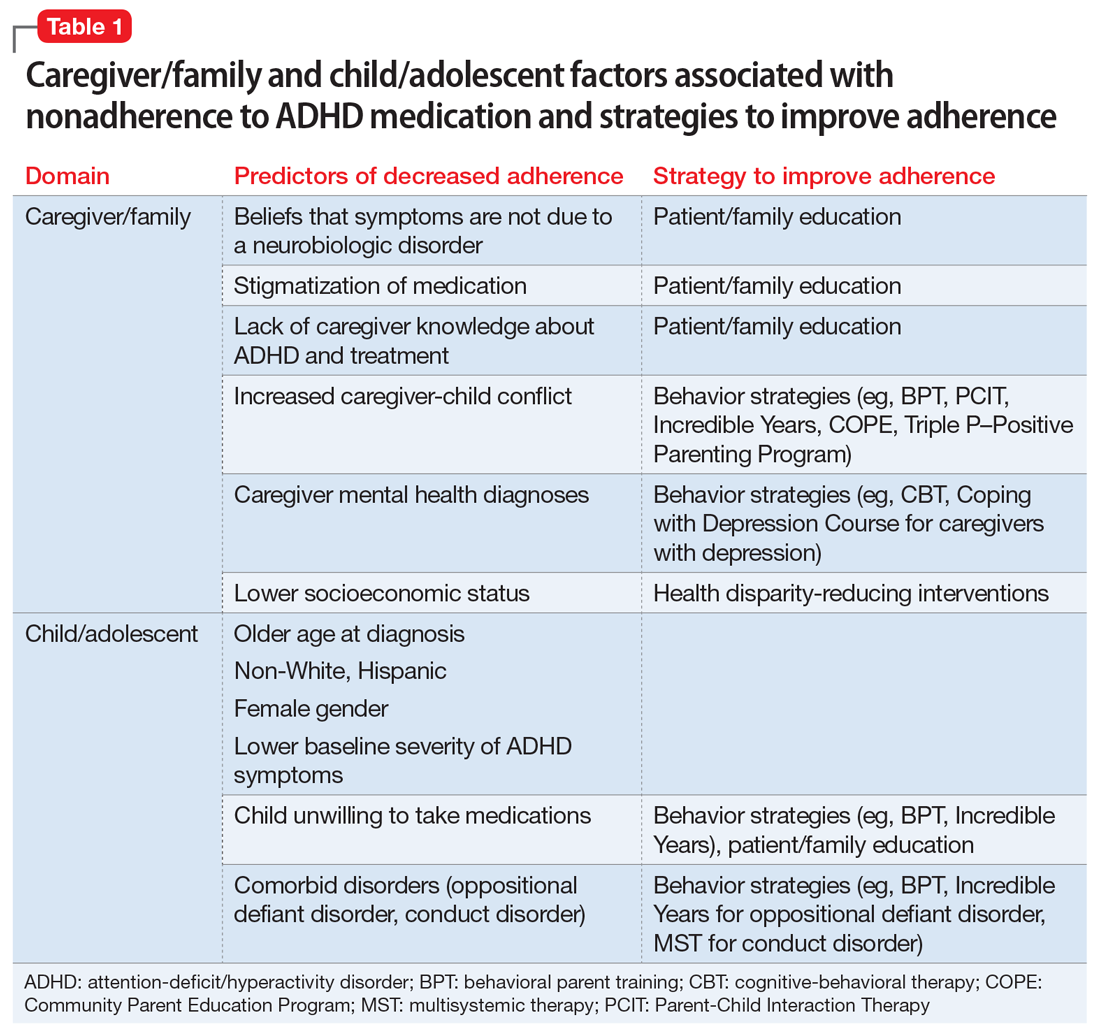

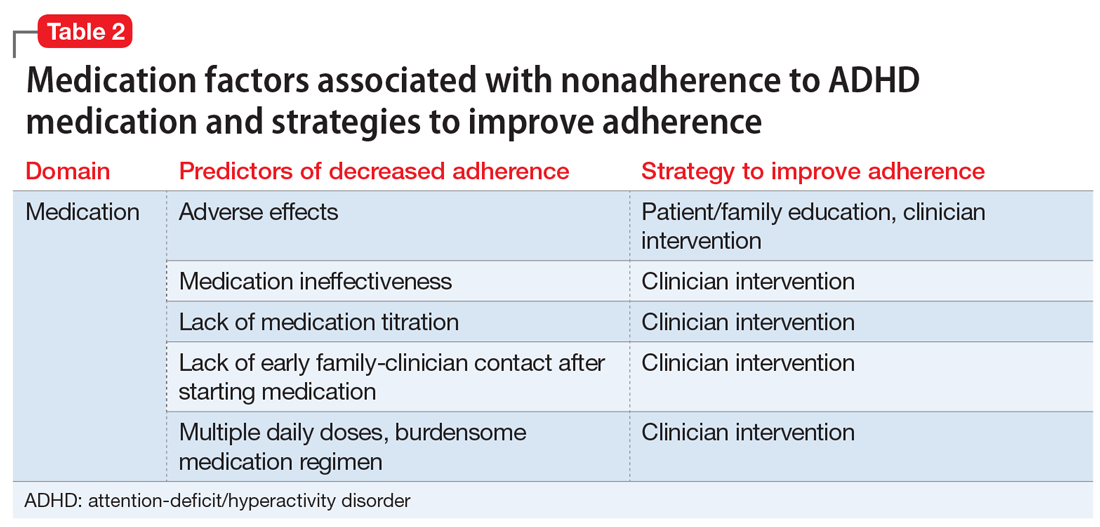

Adherence is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behavior (eg, taking medication) corresponds with agreed recommendations from a clinician.”24 Unfortunately, pediatric ADHD medication adherence has been found to be poor (approximately 64%).25-30 Nonadherence to ADHD medication has been linked to multiple factors, including caregiver/family and child/adolescent factors (Table 1), medication-related factors (Table 2), and health care/system factors (Table 3). Understanding and addressing these factors is essential to maximizing long-term outcomes. In this article, we review the factors associated with nonadherence to ADHD medication, and outline strategies to improve adherence.

Caregiver/family characteristics

Caregiver beliefs about ADHD and their attitudes toward treatment have been associated with the initiation of and adherence to ADHD medication. For example, caregivers who view a child’s difficulties as a medical disorder that requires a biologic intervention are more likely to accept and adhere to medication.31 Similarly, caregivers who perceive ADHD medication as safe, effective, and socially acceptable are more likely to be treatment-adherent.32-35

- increased caregiver knowledge about ADHD33

- receiving an ADHD diagnosis based on a thorough diagnostic process (ie, comprehensive psychological testing)36

- satisfaction with information about medicine

- comfort with the treatment plan.34

Socioeconomic status, family functioning, and caregiver mental health diagnoses (eg, ADHD, depression) have also been linked to ADHD medication adherence. Several studies, including the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD,11 a landmark study of stimulant medication for children with ADHD, have found an association between low income and decreased likelihood of receiving ADHD medication.2,37-39 Further, Gau et al40 found that negative caregiver-child relationships and family dysfunction were associated with poor medication adherence in children with ADHD.9 Prior studies have also shown that mothers of children with ADHD are more likely to have depression and/or anxiety,41,42 and that caregivers with a history of mental health diagnoses are more accepting of initiating medication treatment for their children.43 However, additional studies have found that caregiver mental health diagnoses decreased the likelihood of ADHD medication adherence.40,44

Child characteristics

Child characteristics associated with decreased ADHD medication adherence include older age (eg, adolescents vs school-aged children),29,30,34,40,45-47 non-White race, Hispanic ethnicity,29,33,48-51 female gender,29,33,52 lower baseline ADHD symptom severity,30,37 and child unwillingness to take medications.34 However, prior studies have not been completely consistent about the relationship between child comorbid conditions (eg, oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], conduct disorder) and ADHD medication adherence. A few studies found that child comorbid conditions, especially ODD, mediate poor ADHD medication adherence, possibly secondary to an increased caregiver-child conflict.30,53,54 However, other studies have reported that the presence of comorbid ODD, depression, and anxiety predicted increased adherence to ADHD medications.37,46

Medication-related factors

Adverse effects of medications are the most commonly cited reason for ADHD medication nonadherence

On the other hand, increased ADHD medication effectiveness has been associated with improved medication adherence.5,34,54-56 Medication titration and dosing factors have also been shown to affect adherence. Specifically, adherence has been improved when ADHD medications are titrated in a systematic manner soon after starting treatment, and when families have an early first contact with a physician after starting medication (within 3 months).28 In addition, use of a simplified dose regimen has been linked to better adherence: patients who are prescribed long-acting stimulants are more likely to adhere to treatment compared with patients who take short-acting formulations.26,40,49,61-63 It is possible that long-acting stimulants increase adherence because they produce more even and sustained effects on ADHD symptoms throughout the day, compared with short-acting formulations.64 Furthermore, the inconvenience of taking multiple doses throughout the day, as well as the potential social stigma of mid-school day dosing, may negatively impact adherence to short-acting formulations.10

Continue to: Health care/system factors

Health care/system factors

Several studies have investigated the influence of health services factors on ADHD medication adherence. Specifically, limited transportation services and lack of mental health providers in the community have been linked to decreased ADHD medication adherence.47,65,66 Furthermore, limited insurance coverage and higher costs of ADHD medications, which lead to substantial out-of-pocket payments for families, have been associated with decreased likelihood of ADHD medication adherence.29,67

Clinician-related factors also can affect ADHD medication adherence. For example, a clinician’s lack knowledge of ADHD care can negatively impact ADHD medication adherence.68 Two studies have documented improved ADHD medication adherence when treatment is provided by specialists (eg, child psychiatrists) rather than by community primary care providers, possibly because specialists are more likely to provide close stimulant titration and monitoring (ie, ≥ 3 visits in the first 90 days) and use higher maximum doses.62,69 Furthermore, ADHD medication initiation and adherence are increased when patients have a strong working alliance with their clinician and trust the health care system,31,34,35 as well as when there is a match between the caregiver’s and clinician’s perception of the cause, course, and best treatment practices for a child’s ADHD.65

Strategies to improve medication adherence

A number of strategies to improve ADHD medication adherence can be derived from our knowledge of the factors that influence adherence.

Patient/family education. Unanswered questions about ADHD diagnosis, etiology, and medication adverse effects can negatively impact the ADHD treatment process. Therefore, patient/family education regarding ADHD and its management is necessary to improve medication adherence, because it helps families attain the knowledge, confidence, and motivation to manage their child’s condition.

Clinicians have an important role in educating patients about70:

- the medications they are taking

- why they are taking them

- what the medications look like

- the time of medication administration

- the potential adverse effects

- what to do if adverse effects occur

- what regular testing/monitoring is necessary.

Clinicians can provide appropriate psychoeducation by sharing written materials and trusted websites with families (see Related Resources).

Behavioral strategies. Behavioral interventions have been among the most effective strategies for improving medication adherence in other chronic conditions.71 Behavioral strategies are likely to be particularly important for families of children with ADHD and comorbid conditions such as ODD because these families experience considerable caregiver-child conflict.72 Moreover, parents of children with ADHD are at higher risk for having ADHD and depression themselves,73 both of which may interfere with a parent’s ability to obtain and administer medications consistently. Thus, for these families, using a combination of psychoeducation and behavioral strategies will be necessary to affect change in attitude and behavior. Behavioral strategies that can be used to improve medication adherence include:

- Technology-based interventions can reduce the impact of environmental barriers to adherence. For example, pharmacy automatic prescription renewal systems can reduce the likelihood of families failing to obtain ADHD medication refills. Pill reminder boxes, smartphone alerts, and setting various alarms can effectively prompt caregivers/patients to administer medication. In particular, these methods can be crucial in families for which multiple members have ADHD and its attendant difficulties with organization and task completion.

- Caregiver training may assist families in developing specific behavioral management skills that support adherence. This training can be as straightforward as instructing caregivers on the use of positive reinforcement when teaching their children to swallow pills. It may also encompass structured behavioral interventions aimed at training caregivers to utilize rewards and consequences in order to maximize medication adherence.74

Continue to: Clinician interventions

Clinician interventions. Clinicians can use decision aids to help inform families about treatment options, promote shared decision making, and decrease uncertainty about the treatment plan75 (see Related Resources). Early titration of ADHD medications and early first contact (within months of starting medication treatment) between caregivers and clinicians, whether via in-person visit, telephone, or email, have also been related to improved adherence.28 Furthermore, clinicians can improve adherence by prescribing a simplified medication regimen (ie, long-acting formulations that provide full-day coverage). To address the negative impact of high out-of-pocket ADHD medication costs on adherence, clinicians can also prescribe generic preparations and/or “preferred” medications options on an individual patient’s formulary.

Because clinician knowledge and expertise in ADHD care has been linked to improved patient medication adherence,68 clinicians are encouraged to use the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline for diagnosis and treatment of ADHD, which includes a supplemental process of care algorithm (last published in 2011,10 with an updated guideline anticipated in 2019), as well as the AAP/National Institute for Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ) ADHD Toolkit,76 which includes items helpful for ADHD diagnosis and treatment. The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics is also developing a clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of complex ADHD (ie, ADHD complicated by coexisting mental health, developmental, and/or psychosocial conditions or issues), with publication anticipated in 2019. Primary care providers can also improve their expertise in ADHD care by pursuing additional mental health–related trainings (such as those conducted by the REACH Institute).77

Because receiving ADHD care from a specialist has been shown to improve medication initiation and adherence,62,69 other strategies to address the short supply of child psychiatrists include offering incentives to medical students to pursue a career in child psychiatry (eg, loan forgiveness). Telepsychiatry and co-location of mental health specialists and primary care providers are additional innovative ways in which ADHD specialty care can be delivered to more patients.64

Finally, providing culturally-sensitive care can strengthen the clinician-caregiver relationship and promote adherence to treatment. For example, clinicians can partner with local groups to increase their understanding of how different racial/ethnic groups perceive ADHD and its treatment.64

Peer support models. Peers are credible role models who have a valued role in facilitating the use of mental health services by empowering families and enhancing service satisfaction.78 In several communities in the United States, peer models using family advocates have been introduced.79 Family advocates are typically caregivers of children who have special needs or have been involved in the mental health system. Their perspective—as peers and first-hand consumers of the health care and/or mental health system—can make them powerful and effective coaches to families of children with ADHD. By helping families to navigate ADHD care systems successfully, family advocates can play an important role in enhancing ADHD medication adherence, although further investigation is needed. In addition, the stigma around ADHD medication use, which adversely impacts adherence, can be mitigated if caregivers participate in organized ADHD-related support groups (eg, Children and Adults with ADHD [CHADD]).

Continue to: Health disparity-reducing interventions

Health disparity-reducing interventions. Successful health disparity-reducing interventions—such as those developed to enhance care of other chronic disorders including asthma and diabetes—can be applied to improve ADHD care. These interventions, which include medical-legal partnerships (eg, between clinicians, social workers, legal advocates, and community partners) in primary care centers, have been shown to improve health insurance coverage and therefore health care access.80,81 Although some hardships linked to nonadherence (eg, low socioeconomic status) may not be amenable to health care–related interventions, screening for these hardships can identify children who are most at risk for poor adherence. This would alert clinicians to proactively identify barriers to adherence and implement mitigation strategies. This might include developing more streamlined, easier-to-follow management plans for these patients, such as those that can be delivered through pharmacist-physician collaborative programs82 and school-based therapy programs.83-85

Bottom Line

Suboptimal adherence to medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be addressed through patient/family education, behavioral strategies, clinician interventions, peer support models, and health disparity-reducing interventions. By improving ADHD treatment adherence, these interventions have the potential to maximize long-term outcomes.

Related Resources

- Cohen Children’s Medical Center Northwell Health. The ADHD Medication Guide. www.ADHDMedicationGuide.com. Revised December 31, 2017.

- Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in practice. www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/j/anderson-center/ evidence-based-care/decision-aids.

- CHADD. Children and Adults with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. www.chadd.org.

Drug Brand Name

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

1. Froehlich TE, Lanphear BP, Epstein JN, et al. Prevalence, recognition, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a national sample of US children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(9):857-864.

2. Visser SN, Lesesne CA, Perou R. National estimates and factors associated with medication treatment for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2007;119 (Suppl 1):S99-S106.

3. Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, et al. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(2):199-212.

4. Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, et al. The MTA at 8 years: prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(5):484-500.

5. Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effectiveness of treatment in at-risk preschoolers; long-term effectiveness in all ages; and variability in prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK82368/.

6. Wehmeier PM, Schacht A, Barkley RA. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):209-217.

7. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, et al. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(2):192-202.

8. Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(6):631-642.

9. Pliszka S, the AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):894-921.

10. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007-1022.

11. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The MTA Cooperative Group. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(12):1073-1086.

12. Abikoff H, Hechtman L, Klein RG, et al. Symptomatic improvement in children with ADHD treated with long-term methylphenidate and multimodal psychosocial treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(7):802-811.

13. Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. Long-term school outcomes for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based perspective. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(4):265-273.

14. Scheffler RM, Brown TT, Fulton BD, et al. Positive association between attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder medication use and academic achievement during elementary school. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):1273-1279.

15. Dalsgaard S, Nielsen HS, Simonsen M. Five-fold increase in national prevalence rates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and other psychiatric disorders: a Danish register-based study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013;23(7):432-439.

16. Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, Zetterqvist J, et al. Medication for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):2006-2014.

17. Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, D’Onofrio BM, et al. Serious transport accidents in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the effect of medication: a population-based study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(3):319-325.

18. Chang Z, Quinn PD, Hur K, et al. Association between medication use for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk of motor vehicle crashes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):597-603.

19. Dalsgaard S, Leckman JF, Mortensen PB, et al. Effect of drugs on the risk of injuries in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(8):702-709.

20. Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, et al. Stimulant ADHD medication and risk for substance abuse. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(8):878-885.

21. Fischer M, Barkley RA. Childhood stimulant treatment and risk for later substance abuse. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 11):19-23.

22. Biederman J. Pharmacotherapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) decreases the risk for substance abuse: findings from a longitudinal follow-up of youths with and without ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 11):3-8.

23. Chang Z, D’Onofrio BM, Quinn PD, et al. Medicationfor attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk for depression: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(12):916-922.

24. World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf?ua=1. Published 2003. Accessed July 22, 2019.

25. Perwien A, Hall J, Swensen A, et al. Stimulant treatment patterns and compliance in children and adults with newly treated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10(2):122-129.

26. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Zimmerman B. An analysis of patient adherence to treatment during a 1-year, open-label study of OROS methylphenidate in children with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2007;11(2):157-166.

27. Barner JC, Khoza S, Oladapo A. ADHD medication use, adherence, persistence and cost among Texas Medicaid children. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(Suppl 2):13-22.

28. Brinkman WB, Baum R, Kelleher KJ, et al. Relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder care and medication continuity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):289-294.

29. Bokhari FAS, Heiland F, Levine P, et al. Risk factors for discontinuing drug therapy among children with ADHD. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2008;8(3):134-158.

30. Thiruchelvam D, Charach A, Schachar RJ. Moderators and mediators of long-term adherence to stimulant treatment in children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):922-928.

31. DosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Evans-Lacko SE, et al. The meaning of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication and parents’ initiation and continuity of treatment for their child. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(4):377-383.

32. dosReis S, Myers MA. Parental attitudes and involvement in psychopharmacological treatment for ADHD: a conceptual model. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20(2):135-141.

33. Bussing R, Koro-Ljungberg M, Noguchi K, et al. Willingness to use ADHD treatments: a mixed methods study of perceptions by adolescents, parents, health professionals and teachers. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(1):92-100.

34. Brinkman WB, Sucharew H, Majcher JH, et al. Predictors of medication continuity in children with ADHD. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2580.

35. Coletti DJ, Pappadopulos E, Katsiotas NJ, et al. Parent perspectives on the decision to initiate medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(3):226-237.

36. Bussing R, Gary FA. Practice guidelines and parental ADHD treatment evaluations: friends or foes? Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9(5):223-233.

37. Charach A, Gajaria A. Improving psychostimulant adherence in children with ADHD. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(10):1563-1571.

38. Rieppi R, Greenhill LL, Ford RE, et al. Socioeconomic status as a moderator of ADHD treatment outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(3):269-277.

39. Swanson JM, Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE, et al. Secondary evaluations of MTA 36-month outcomes: propensity score and growth mixture model analyses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(8):1003-1014.

40. Gau SS, Shen HY, Chou MC, et al. Determinants of adherence to methylphenidate and the impact of poor adherence on maternal and family measures. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(3):286-297.

41. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock C, et al. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria--III. Mother-child interactions, family conflicts and maternal psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1991;32(2):233-255.

42. Kashdan TB, Jacob RG, Pelham WE, et al. Depression and anxiety in parents of children with ADHD and varying levels of oppositional defiant behaviors: modeling relationships with family functioning. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33(1):169-181.

43. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Bailey K, et al. Parental opinions regarding treatment for social anxiety disorder in youth. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(5):315-322.

44. Leslie LK, Aarons GA, Haine RA, et al. Caregiver depression and medication use by youths with ADHD who receive services in the public sector. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(1):131-134.

45. Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. Long-term stimulant medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a population-based study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(1):1-10.

46. Atzori P, Usala T, Carucci S, et al. Predictive factors for persistent use and compliance of immediate-release methylphenidate: a 36-month naturalistic study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(6):673-681.

47. Chen CY, Yeh HH, Chen KH, et al. Differential effects of predictors on methylphenidate initiation and discontinuation among young people with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(3):265-273.

48. Winterstein AG, Gerhard T, Shuster J, et al. Utilization of pharmacologic treatment in youths with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Medicaid database. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(1):24-31.

49. Marcus SC, Wan GJ, Kemner JE, et al. Continuity of methylphenidate treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(6):572-578.

50. Cummings JR JX, Allen L, Lally C, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in ADHD treatment quality among Medicaid-enrolled youth. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e2016-e2044.

51. Hudson JL, Miller GE, Kirby JB. Explaining racial and ethnic differences in children’s use of stimulant medications. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1068-1075.

52. van den Ban E, Souverein PC, Swaab H, et al. Less discontinuation of ADHD drug use since the availability of long-acting ADHD medication in children, adolescents and adults under the age of 45 years in the Netherlands. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2010;2(4):213-220.

53. Charach A, Ickowicz A, Schachar R. Stimulant treatment over five years: adherence, effectiveness, and adverse effects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(5):559-567.

54. Toomey SL, Sox CM, Rusinak D, et al. Why do children with ADHD discontinue their medication? Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(8):763-769.

55. Brinkman WB, Simon JO, Epstein JN. Reasons why children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder stop and restart taking medicine. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(3):273-280.

56. Wehmeier PM, Dittmann RW, Banaschewski T. Treatment compliance or medication adherence in children and adolescents on ADHD medication in clinical practice: results from the COMPLY observational study. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2015;7(2):165-174.

57. Frank E, Ozon C, Nair V, et al. Examining why patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder lack adherence to medication over the long term: a review and analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1459-e1468.

58. Pozzi M, Carnovale C, Peeters G, et al. Adverse drug events related to mood and emotion in paediatric patients treated for ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;238:161-178.

59. Stuckelman ZD, Mulqueen JM, Ferracioli-Oda E, et al. Risk of irritability with psychostimulant treatment in children with ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(6):e648-e655.

60. Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):727-738.

61. Lawson KA, Johnsrud M, Hodgkins P, et al. Utilization patterns of stimulants in ADHD in the Medicaid population: a retrospective analysis of data from the Texas Medicaid program. Clin Ther. 2012;34(4):944-956 e944.

62. Olfson M, Marcus S, Wan G. Stimulant dosing for children with ADHD: a medical claims analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(1):51-59.

63. Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. 3-year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(8):989-1002.

64. Van Cleave J, Leslie LK. Approaching ADHD as a chronic condition: implications for long-term adherence. Pediatr Ann. 2008;37(1):19-26.

65. Leslie LK, Plemmons D, Monn AR, et al. Investigating ADHD treatment trajectories: listening to families’ stories about medication use. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(3):179-188.

66. Fiks AG, Mayne S, Localio AR, et al. Shared decision making and behavioral impairment: a national study among children with special health care needs. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:153.

67. Stevens J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Race/ethnicity and insurance status as factors associated with ADHD treatment patterns. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(1):88-96.

68. Charach A, Skyba A, Cook L, et al. Using stimulant medication for children with ADHD: what do parents say? A brief report. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(2):75-83.

69. Chen CY, Gerhard T, Winterstein AG. Determinants of initial pharmacological treatment for youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolescent Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(2):187-195.

70. National Council on Patient Information and Education. Enhancing prescription medication adherence: a national action plan. http://www.bemedwise.org/docs/enhancingprescriptionmedicineadherence.pdf. Published August 2007. Accessed July 22, 2019.

71. Kahana S, Drotar D, Frazier T. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote adherence to treatment in pediatric chronic health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(6):590-611.

72. Johnston C, Mash EJ. Families of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review and recommendations for future research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001;4(3):183-207.

73. Chronis AM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE Jr., et al. Psychopathology and substance abuse in parents of young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(12):1424-1432.

74. Chacko A, Newcorn JH, Feirsen N, et al. Improving medication adherence in chronic pediatric health conditions: a focus on ADHD in youth. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(22):2416-2423.

75. Brinkman WB, Hartl Majcher J, Polling LM, et al. Shared decision-making to improve attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder care. Patient Educ Couns. 2013;93(1):95-101.

76. American Academy of Pediatrics. Caring for children with ADHD: a resource toolkit for clinicians. 2nd ed. https://www.aap.org/en-us/pubserv/adhd2/Pages/default.aspx. Published 2011. Accessed July 22, 2019.

77. The REACH Institute. Course dates and registration. http://www.thereachinstitute.org/services/for-primary-care-practitioners/training-dates-and-registration. Accessed July 22, 2019.

78. Sells D, Davidson L, Jewell C, et al. The treatment relationship in peer-based and regular case management for clients with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2006;57(8):1179-1184.

79. Hoagwood KE, Green E, Kelleher K, et al. Family advocacy, support and education in children’s mental health: results of a national survey. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2008;35(1-2):73-83.

80. Klein MD, Beck AF, Henize AW, et al. Doctors and lawyers collaborating to HeLP children—outcomes from a successful partnership between professions. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(3):1063-1073.

81. Weintraub D, Rodgers MA, Botcheva L, et al. Pilot study of medical-legal partnership to address social and legal needs of patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2010;21(Suppl 2):157-168.

82. Bradley CL, Luder HR, Beck AF, et al. Pediatric asthma medication therapy management through community pharmacy and primary care collaboration. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2016;56(4):455-460.

83. Noyes K, Bajorska A, Fisher S, et al. Cost-effectiveness of the school-based asthma therapy (SBAT) program. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e709-e717.

84. Halterman JS, Fagnano M, Montes G, et al. The school-based preventive asthma care trial: results of a pilot study. J Pediatr. 2012;161(6):1109-1115.

85. Halterman JS, Szilagyi PG, Fisher SG, et al. Randomized controlled trial to improve care for urban children with asthma: results of the school-based asthma therapy trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(3):262-268.

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common childhood neurodevelopmental disorder, affecting 8% to 12% of school-aged children in the United States1-3 with significant impairments that often persist into adulthood.4-8 Current guidelines recommend stimulant medication and/or behavioral therapies as first-line treatments for ADHD.9,10 There is a wealth of evidence on the efficacy of stimulants in ADHD, with the most significant effects noted on core ADHD symptoms.11,12 Additional evidence links stimulants to decreased long-term negative outcomes, including reduced school absences and grade retention,13 as well as modestly but significantly improved reading and math scores.14 Other studies have reported that individuals with ADHD who receive medication have decreased criminality,15,16 motor vehicle accidents,17,18 injuries,19 substance abuse,20-22 and risk for subsequent and concurrent depression.23 Therefore, the evidence suggests that consistent medication treatment helps improve outcomes for individuals with ADHD.

Adherence is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behavior (eg, taking medication) corresponds with agreed recommendations from a clinician.”24 Unfortunately, pediatric ADHD medication adherence has been found to be poor (approximately 64%).25-30 Nonadherence to ADHD medication has been linked to multiple factors, including caregiver/family and child/adolescent factors (Table 1), medication-related factors (Table 2), and health care/system factors (Table 3). Understanding and addressing these factors is essential to maximizing long-term outcomes. In this article, we review the factors associated with nonadherence to ADHD medication, and outline strategies to improve adherence.

Caregiver/family characteristics

Caregiver beliefs about ADHD and their attitudes toward treatment have been associated with the initiation of and adherence to ADHD medication. For example, caregivers who view a child’s difficulties as a medical disorder that requires a biologic intervention are more likely to accept and adhere to medication.31 Similarly, caregivers who perceive ADHD medication as safe, effective, and socially acceptable are more likely to be treatment-adherent.32-35

- increased caregiver knowledge about ADHD33

- receiving an ADHD diagnosis based on a thorough diagnostic process (ie, comprehensive psychological testing)36

- satisfaction with information about medicine

- comfort with the treatment plan.34

Socioeconomic status, family functioning, and caregiver mental health diagnoses (eg, ADHD, depression) have also been linked to ADHD medication adherence. Several studies, including the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD,11 a landmark study of stimulant medication for children with ADHD, have found an association between low income and decreased likelihood of receiving ADHD medication.2,37-39 Further, Gau et al40 found that negative caregiver-child relationships and family dysfunction were associated with poor medication adherence in children with ADHD.9 Prior studies have also shown that mothers of children with ADHD are more likely to have depression and/or anxiety,41,42 and that caregivers with a history of mental health diagnoses are more accepting of initiating medication treatment for their children.43 However, additional studies have found that caregiver mental health diagnoses decreased the likelihood of ADHD medication adherence.40,44

Child characteristics

Child characteristics associated with decreased ADHD medication adherence include older age (eg, adolescents vs school-aged children),29,30,34,40,45-47 non-White race, Hispanic ethnicity,29,33,48-51 female gender,29,33,52 lower baseline ADHD symptom severity,30,37 and child unwillingness to take medications.34 However, prior studies have not been completely consistent about the relationship between child comorbid conditions (eg, oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], conduct disorder) and ADHD medication adherence. A few studies found that child comorbid conditions, especially ODD, mediate poor ADHD medication adherence, possibly secondary to an increased caregiver-child conflict.30,53,54 However, other studies have reported that the presence of comorbid ODD, depression, and anxiety predicted increased adherence to ADHD medications.37,46

Medication-related factors

Adverse effects of medications are the most commonly cited reason for ADHD medication nonadherence

On the other hand, increased ADHD medication effectiveness has been associated with improved medication adherence.5,34,54-56 Medication titration and dosing factors have also been shown to affect adherence. Specifically, adherence has been improved when ADHD medications are titrated in a systematic manner soon after starting treatment, and when families have an early first contact with a physician after starting medication (within 3 months).28 In addition, use of a simplified dose regimen has been linked to better adherence: patients who are prescribed long-acting stimulants are more likely to adhere to treatment compared with patients who take short-acting formulations.26,40,49,61-63 It is possible that long-acting stimulants increase adherence because they produce more even and sustained effects on ADHD symptoms throughout the day, compared with short-acting formulations.64 Furthermore, the inconvenience of taking multiple doses throughout the day, as well as the potential social stigma of mid-school day dosing, may negatively impact adherence to short-acting formulations.10

Continue to: Health care/system factors

Health care/system factors

Several studies have investigated the influence of health services factors on ADHD medication adherence. Specifically, limited transportation services and lack of mental health providers in the community have been linked to decreased ADHD medication adherence.47,65,66 Furthermore, limited insurance coverage and higher costs of ADHD medications, which lead to substantial out-of-pocket payments for families, have been associated with decreased likelihood of ADHD medication adherence.29,67

Clinician-related factors also can affect ADHD medication adherence. For example, a clinician’s lack knowledge of ADHD care can negatively impact ADHD medication adherence.68 Two studies have documented improved ADHD medication adherence when treatment is provided by specialists (eg, child psychiatrists) rather than by community primary care providers, possibly because specialists are more likely to provide close stimulant titration and monitoring (ie, ≥ 3 visits in the first 90 days) and use higher maximum doses.62,69 Furthermore, ADHD medication initiation and adherence are increased when patients have a strong working alliance with their clinician and trust the health care system,31,34,35 as well as when there is a match between the caregiver’s and clinician’s perception of the cause, course, and best treatment practices for a child’s ADHD.65

Strategies to improve medication adherence

A number of strategies to improve ADHD medication adherence can be derived from our knowledge of the factors that influence adherence.

Patient/family education. Unanswered questions about ADHD diagnosis, etiology, and medication adverse effects can negatively impact the ADHD treatment process. Therefore, patient/family education regarding ADHD and its management is necessary to improve medication adherence, because it helps families attain the knowledge, confidence, and motivation to manage their child’s condition.

Clinicians have an important role in educating patients about70:

- the medications they are taking

- why they are taking them

- what the medications look like

- the time of medication administration

- the potential adverse effects

- what to do if adverse effects occur

- what regular testing/monitoring is necessary.

Clinicians can provide appropriate psychoeducation by sharing written materials and trusted websites with families (see Related Resources).

Behavioral strategies. Behavioral interventions have been among the most effective strategies for improving medication adherence in other chronic conditions.71 Behavioral strategies are likely to be particularly important for families of children with ADHD and comorbid conditions such as ODD because these families experience considerable caregiver-child conflict.72 Moreover, parents of children with ADHD are at higher risk for having ADHD and depression themselves,73 both of which may interfere with a parent’s ability to obtain and administer medications consistently. Thus, for these families, using a combination of psychoeducation and behavioral strategies will be necessary to affect change in attitude and behavior. Behavioral strategies that can be used to improve medication adherence include:

- Technology-based interventions can reduce the impact of environmental barriers to adherence. For example, pharmacy automatic prescription renewal systems can reduce the likelihood of families failing to obtain ADHD medication refills. Pill reminder boxes, smartphone alerts, and setting various alarms can effectively prompt caregivers/patients to administer medication. In particular, these methods can be crucial in families for which multiple members have ADHD and its attendant difficulties with organization and task completion.

- Caregiver training may assist families in developing specific behavioral management skills that support adherence. This training can be as straightforward as instructing caregivers on the use of positive reinforcement when teaching their children to swallow pills. It may also encompass structured behavioral interventions aimed at training caregivers to utilize rewards and consequences in order to maximize medication adherence.74

Continue to: Clinician interventions

Clinician interventions. Clinicians can use decision aids to help inform families about treatment options, promote shared decision making, and decrease uncertainty about the treatment plan75 (see Related Resources). Early titration of ADHD medications and early first contact (within months of starting medication treatment) between caregivers and clinicians, whether via in-person visit, telephone, or email, have also been related to improved adherence.28 Furthermore, clinicians can improve adherence by prescribing a simplified medication regimen (ie, long-acting formulations that provide full-day coverage). To address the negative impact of high out-of-pocket ADHD medication costs on adherence, clinicians can also prescribe generic preparations and/or “preferred” medications options on an individual patient’s formulary.

Because clinician knowledge and expertise in ADHD care has been linked to improved patient medication adherence,68 clinicians are encouraged to use the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline for diagnosis and treatment of ADHD, which includes a supplemental process of care algorithm (last published in 2011,10 with an updated guideline anticipated in 2019), as well as the AAP/National Institute for Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ) ADHD Toolkit,76 which includes items helpful for ADHD diagnosis and treatment. The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics is also developing a clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of complex ADHD (ie, ADHD complicated by coexisting mental health, developmental, and/or psychosocial conditions or issues), with publication anticipated in 2019. Primary care providers can also improve their expertise in ADHD care by pursuing additional mental health–related trainings (such as those conducted by the REACH Institute).77

Because receiving ADHD care from a specialist has been shown to improve medication initiation and adherence,62,69 other strategies to address the short supply of child psychiatrists include offering incentives to medical students to pursue a career in child psychiatry (eg, loan forgiveness). Telepsychiatry and co-location of mental health specialists and primary care providers are additional innovative ways in which ADHD specialty care can be delivered to more patients.64

Finally, providing culturally-sensitive care can strengthen the clinician-caregiver relationship and promote adherence to treatment. For example, clinicians can partner with local groups to increase their understanding of how different racial/ethnic groups perceive ADHD and its treatment.64

Peer support models. Peers are credible role models who have a valued role in facilitating the use of mental health services by empowering families and enhancing service satisfaction.78 In several communities in the United States, peer models using family advocates have been introduced.79 Family advocates are typically caregivers of children who have special needs or have been involved in the mental health system. Their perspective—as peers and first-hand consumers of the health care and/or mental health system—can make them powerful and effective coaches to families of children with ADHD. By helping families to navigate ADHD care systems successfully, family advocates can play an important role in enhancing ADHD medication adherence, although further investigation is needed. In addition, the stigma around ADHD medication use, which adversely impacts adherence, can be mitigated if caregivers participate in organized ADHD-related support groups (eg, Children and Adults with ADHD [CHADD]).

Continue to: Health disparity-reducing interventions

Health disparity-reducing interventions. Successful health disparity-reducing interventions—such as those developed to enhance care of other chronic disorders including asthma and diabetes—can be applied to improve ADHD care. These interventions, which include medical-legal partnerships (eg, between clinicians, social workers, legal advocates, and community partners) in primary care centers, have been shown to improve health insurance coverage and therefore health care access.80,81 Although some hardships linked to nonadherence (eg, low socioeconomic status) may not be amenable to health care–related interventions, screening for these hardships can identify children who are most at risk for poor adherence. This would alert clinicians to proactively identify barriers to adherence and implement mitigation strategies. This might include developing more streamlined, easier-to-follow management plans for these patients, such as those that can be delivered through pharmacist-physician collaborative programs82 and school-based therapy programs.83-85

Bottom Line

Suboptimal adherence to medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be addressed through patient/family education, behavioral strategies, clinician interventions, peer support models, and health disparity-reducing interventions. By improving ADHD treatment adherence, these interventions have the potential to maximize long-term outcomes.

Related Resources

- Cohen Children’s Medical Center Northwell Health. The ADHD Medication Guide. www.ADHDMedicationGuide.com. Revised December 31, 2017.

- Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in practice. www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/j/anderson-center/ evidence-based-care/decision-aids.

- CHADD. Children and Adults with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. www.chadd.org.

Drug Brand Name

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common childhood neurodevelopmental disorder, affecting 8% to 12% of school-aged children in the United States1-3 with significant impairments that often persist into adulthood.4-8 Current guidelines recommend stimulant medication and/or behavioral therapies as first-line treatments for ADHD.9,10 There is a wealth of evidence on the efficacy of stimulants in ADHD, with the most significant effects noted on core ADHD symptoms.11,12 Additional evidence links stimulants to decreased long-term negative outcomes, including reduced school absences and grade retention,13 as well as modestly but significantly improved reading and math scores.14 Other studies have reported that individuals with ADHD who receive medication have decreased criminality,15,16 motor vehicle accidents,17,18 injuries,19 substance abuse,20-22 and risk for subsequent and concurrent depression.23 Therefore, the evidence suggests that consistent medication treatment helps improve outcomes for individuals with ADHD.

Adherence is defined as “the extent to which a person’s behavior (eg, taking medication) corresponds with agreed recommendations from a clinician.”24 Unfortunately, pediatric ADHD medication adherence has been found to be poor (approximately 64%).25-30 Nonadherence to ADHD medication has been linked to multiple factors, including caregiver/family and child/adolescent factors (Table 1), medication-related factors (Table 2), and health care/system factors (Table 3). Understanding and addressing these factors is essential to maximizing long-term outcomes. In this article, we review the factors associated with nonadherence to ADHD medication, and outline strategies to improve adherence.

Caregiver/family characteristics

Caregiver beliefs about ADHD and their attitudes toward treatment have been associated with the initiation of and adherence to ADHD medication. For example, caregivers who view a child’s difficulties as a medical disorder that requires a biologic intervention are more likely to accept and adhere to medication.31 Similarly, caregivers who perceive ADHD medication as safe, effective, and socially acceptable are more likely to be treatment-adherent.32-35

- increased caregiver knowledge about ADHD33

- receiving an ADHD diagnosis based on a thorough diagnostic process (ie, comprehensive psychological testing)36

- satisfaction with information about medicine

- comfort with the treatment plan.34

Socioeconomic status, family functioning, and caregiver mental health diagnoses (eg, ADHD, depression) have also been linked to ADHD medication adherence. Several studies, including the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD,11 a landmark study of stimulant medication for children with ADHD, have found an association between low income and decreased likelihood of receiving ADHD medication.2,37-39 Further, Gau et al40 found that negative caregiver-child relationships and family dysfunction were associated with poor medication adherence in children with ADHD.9 Prior studies have also shown that mothers of children with ADHD are more likely to have depression and/or anxiety,41,42 and that caregivers with a history of mental health diagnoses are more accepting of initiating medication treatment for their children.43 However, additional studies have found that caregiver mental health diagnoses decreased the likelihood of ADHD medication adherence.40,44

Child characteristics

Child characteristics associated with decreased ADHD medication adherence include older age (eg, adolescents vs school-aged children),29,30,34,40,45-47 non-White race, Hispanic ethnicity,29,33,48-51 female gender,29,33,52 lower baseline ADHD symptom severity,30,37 and child unwillingness to take medications.34 However, prior studies have not been completely consistent about the relationship between child comorbid conditions (eg, oppositional defiant disorder [ODD], conduct disorder) and ADHD medication adherence. A few studies found that child comorbid conditions, especially ODD, mediate poor ADHD medication adherence, possibly secondary to an increased caregiver-child conflict.30,53,54 However, other studies have reported that the presence of comorbid ODD, depression, and anxiety predicted increased adherence to ADHD medications.37,46

Medication-related factors

Adverse effects of medications are the most commonly cited reason for ADHD medication nonadherence

On the other hand, increased ADHD medication effectiveness has been associated with improved medication adherence.5,34,54-56 Medication titration and dosing factors have also been shown to affect adherence. Specifically, adherence has been improved when ADHD medications are titrated in a systematic manner soon after starting treatment, and when families have an early first contact with a physician after starting medication (within 3 months).28 In addition, use of a simplified dose regimen has been linked to better adherence: patients who are prescribed long-acting stimulants are more likely to adhere to treatment compared with patients who take short-acting formulations.26,40,49,61-63 It is possible that long-acting stimulants increase adherence because they produce more even and sustained effects on ADHD symptoms throughout the day, compared with short-acting formulations.64 Furthermore, the inconvenience of taking multiple doses throughout the day, as well as the potential social stigma of mid-school day dosing, may negatively impact adherence to short-acting formulations.10

Continue to: Health care/system factors

Health care/system factors

Several studies have investigated the influence of health services factors on ADHD medication adherence. Specifically, limited transportation services and lack of mental health providers in the community have been linked to decreased ADHD medication adherence.47,65,66 Furthermore, limited insurance coverage and higher costs of ADHD medications, which lead to substantial out-of-pocket payments for families, have been associated with decreased likelihood of ADHD medication adherence.29,67

Clinician-related factors also can affect ADHD medication adherence. For example, a clinician’s lack knowledge of ADHD care can negatively impact ADHD medication adherence.68 Two studies have documented improved ADHD medication adherence when treatment is provided by specialists (eg, child psychiatrists) rather than by community primary care providers, possibly because specialists are more likely to provide close stimulant titration and monitoring (ie, ≥ 3 visits in the first 90 days) and use higher maximum doses.62,69 Furthermore, ADHD medication initiation and adherence are increased when patients have a strong working alliance with their clinician and trust the health care system,31,34,35 as well as when there is a match between the caregiver’s and clinician’s perception of the cause, course, and best treatment practices for a child’s ADHD.65

Strategies to improve medication adherence

A number of strategies to improve ADHD medication adherence can be derived from our knowledge of the factors that influence adherence.

Patient/family education. Unanswered questions about ADHD diagnosis, etiology, and medication adverse effects can negatively impact the ADHD treatment process. Therefore, patient/family education regarding ADHD and its management is necessary to improve medication adherence, because it helps families attain the knowledge, confidence, and motivation to manage their child’s condition.

Clinicians have an important role in educating patients about70:

- the medications they are taking

- why they are taking them

- what the medications look like

- the time of medication administration

- the potential adverse effects

- what to do if adverse effects occur

- what regular testing/monitoring is necessary.

Clinicians can provide appropriate psychoeducation by sharing written materials and trusted websites with families (see Related Resources).

Behavioral strategies. Behavioral interventions have been among the most effective strategies for improving medication adherence in other chronic conditions.71 Behavioral strategies are likely to be particularly important for families of children with ADHD and comorbid conditions such as ODD because these families experience considerable caregiver-child conflict.72 Moreover, parents of children with ADHD are at higher risk for having ADHD and depression themselves,73 both of which may interfere with a parent’s ability to obtain and administer medications consistently. Thus, for these families, using a combination of psychoeducation and behavioral strategies will be necessary to affect change in attitude and behavior. Behavioral strategies that can be used to improve medication adherence include:

- Technology-based interventions can reduce the impact of environmental barriers to adherence. For example, pharmacy automatic prescription renewal systems can reduce the likelihood of families failing to obtain ADHD medication refills. Pill reminder boxes, smartphone alerts, and setting various alarms can effectively prompt caregivers/patients to administer medication. In particular, these methods can be crucial in families for which multiple members have ADHD and its attendant difficulties with organization and task completion.

- Caregiver training may assist families in developing specific behavioral management skills that support adherence. This training can be as straightforward as instructing caregivers on the use of positive reinforcement when teaching their children to swallow pills. It may also encompass structured behavioral interventions aimed at training caregivers to utilize rewards and consequences in order to maximize medication adherence.74

Continue to: Clinician interventions

Clinician interventions. Clinicians can use decision aids to help inform families about treatment options, promote shared decision making, and decrease uncertainty about the treatment plan75 (see Related Resources). Early titration of ADHD medications and early first contact (within months of starting medication treatment) between caregivers and clinicians, whether via in-person visit, telephone, or email, have also been related to improved adherence.28 Furthermore, clinicians can improve adherence by prescribing a simplified medication regimen (ie, long-acting formulations that provide full-day coverage). To address the negative impact of high out-of-pocket ADHD medication costs on adherence, clinicians can also prescribe generic preparations and/or “preferred” medications options on an individual patient’s formulary.

Because clinician knowledge and expertise in ADHD care has been linked to improved patient medication adherence,68 clinicians are encouraged to use the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline for diagnosis and treatment of ADHD, which includes a supplemental process of care algorithm (last published in 2011,10 with an updated guideline anticipated in 2019), as well as the AAP/National Institute for Children’s Health Quality (NICHQ) ADHD Toolkit,76 which includes items helpful for ADHD diagnosis and treatment. The Society for Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics is also developing a clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis and treatment of complex ADHD (ie, ADHD complicated by coexisting mental health, developmental, and/or psychosocial conditions or issues), with publication anticipated in 2019. Primary care providers can also improve their expertise in ADHD care by pursuing additional mental health–related trainings (such as those conducted by the REACH Institute).77

Because receiving ADHD care from a specialist has been shown to improve medication initiation and adherence,62,69 other strategies to address the short supply of child psychiatrists include offering incentives to medical students to pursue a career in child psychiatry (eg, loan forgiveness). Telepsychiatry and co-location of mental health specialists and primary care providers are additional innovative ways in which ADHD specialty care can be delivered to more patients.64

Finally, providing culturally-sensitive care can strengthen the clinician-caregiver relationship and promote adherence to treatment. For example, clinicians can partner with local groups to increase their understanding of how different racial/ethnic groups perceive ADHD and its treatment.64

Peer support models. Peers are credible role models who have a valued role in facilitating the use of mental health services by empowering families and enhancing service satisfaction.78 In several communities in the United States, peer models using family advocates have been introduced.79 Family advocates are typically caregivers of children who have special needs or have been involved in the mental health system. Their perspective—as peers and first-hand consumers of the health care and/or mental health system—can make them powerful and effective coaches to families of children with ADHD. By helping families to navigate ADHD care systems successfully, family advocates can play an important role in enhancing ADHD medication adherence, although further investigation is needed. In addition, the stigma around ADHD medication use, which adversely impacts adherence, can be mitigated if caregivers participate in organized ADHD-related support groups (eg, Children and Adults with ADHD [CHADD]).

Continue to: Health disparity-reducing interventions

Health disparity-reducing interventions. Successful health disparity-reducing interventions—such as those developed to enhance care of other chronic disorders including asthma and diabetes—can be applied to improve ADHD care. These interventions, which include medical-legal partnerships (eg, between clinicians, social workers, legal advocates, and community partners) in primary care centers, have been shown to improve health insurance coverage and therefore health care access.80,81 Although some hardships linked to nonadherence (eg, low socioeconomic status) may not be amenable to health care–related interventions, screening for these hardships can identify children who are most at risk for poor adherence. This would alert clinicians to proactively identify barriers to adherence and implement mitigation strategies. This might include developing more streamlined, easier-to-follow management plans for these patients, such as those that can be delivered through pharmacist-physician collaborative programs82 and school-based therapy programs.83-85

Bottom Line

Suboptimal adherence to medications for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) can be addressed through patient/family education, behavioral strategies, clinician interventions, peer support models, and health disparity-reducing interventions. By improving ADHD treatment adherence, these interventions have the potential to maximize long-term outcomes.

Related Resources

- Cohen Children’s Medical Center Northwell Health. The ADHD Medication Guide. www.ADHDMedicationGuide.com. Revised December 31, 2017.

- Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Decision aids to facilitate shared decision making in practice. www.cincinnatichildrens.org/service/j/anderson-center/ evidence-based-care/decision-aids.

- CHADD. Children and Adults with attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. www.chadd.org.

Drug Brand Name

Methylphenidate • Concerta, Ritalin

1. Froehlich TE, Lanphear BP, Epstein JN, et al. Prevalence, recognition, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a national sample of US children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(9):857-864.

2. Visser SN, Lesesne CA, Perou R. National estimates and factors associated with medication treatment for childhood attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatrics. 2007;119 (Suppl 1):S99-S106.

3. Danielson ML, Bitsko RH, Ghandour RM, et al. Prevalence of parent-reported ADHD diagnosis and associated treatment among U.S. children and adolescents, 2016. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2018;47(2):199-212.

4. Molina BS, Hinshaw SP, Swanson JM, et al. The MTA at 8 years: prospective follow-up of children treated for combined-type ADHD in a multisite study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(5):484-500.

5. Charach A, Dashti B, Carson P, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: effectiveness of treatment in at-risk preschoolers; long-term effectiveness in all ages; and variability in prevalence, diagnosis, and treatment. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2011. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK82368/.

6. Wehmeier PM, Schacht A, Barkley RA. Social and emotional impairment in children and adolescents with ADHD and the impact on quality of life. J Adolesc Health. 2010;46(3):209-217.

7. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Smallish L, et al. Young adult outcome of hyperactive children: adaptive functioning in major life activities. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;45(2):192-202.

8. Spencer TJ, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: diagnosis, lifespan, comorbidities, and neurobiology. J Pediatr Psychol. 2007;32(6):631-642.

9. Pliszka S, the AACAP Work Group on Quality Issues. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(7):894-921.

10. Subcommittee on Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder; Steering Committee on Quality Improvement and Management. ADHD: clinical practice guideline for the diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and adolescents. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):1007-1022.

11. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. The MTA Cooperative Group. Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56(12):1073-1086.

12. Abikoff H, Hechtman L, Klein RG, et al. Symptomatic improvement in children with ADHD treated with long-term methylphenidate and multimodal psychosocial treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(7):802-811.

13. Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. Long-term school outcomes for children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a population-based perspective. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(4):265-273.

14. Scheffler RM, Brown TT, Fulton BD, et al. Positive association between attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder medication use and academic achievement during elementary school. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):1273-1279.

15. Dalsgaard S, Nielsen HS, Simonsen M. Five-fold increase in national prevalence rates of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications for children and adolescents with autism spectrum disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and other psychiatric disorders: a Danish register-based study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2013;23(7):432-439.

16. Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, Zetterqvist J, et al. Medication for attention deficit-hyperactivity disorder and criminality. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(21):2006-2014.

17. Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, D’Onofrio BM, et al. Serious transport accidents in adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the effect of medication: a population-based study. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(3):319-325.

18. Chang Z, Quinn PD, Hur K, et al. Association between medication use for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk of motor vehicle crashes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):597-603.

19. Dalsgaard S, Leckman JF, Mortensen PB, et al. Effect of drugs on the risk of injuries in children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(8):702-709.

20. Chang Z, Lichtenstein P, Halldner L, et al. Stimulant ADHD medication and risk for substance abuse. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2014;55(8):878-885.

21. Fischer M, Barkley RA. Childhood stimulant treatment and risk for later substance abuse. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 11):19-23.

22. Biederman J. Pharmacotherapy for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) decreases the risk for substance abuse: findings from a longitudinal follow-up of youths with and without ADHD. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(Suppl 11):3-8.

23. Chang Z, D’Onofrio BM, Quinn PD, et al. Medicationfor attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and risk for depression: a nationwide longitudinal cohort study. Biol Psychiatry. 2016;80(12):916-922.

24. World Health Organization. Adherence to long-term therapies: evidence for action. https://www.who.int/chp/knowledge/publications/adherence_full_report.pdf?ua=1. Published 2003. Accessed July 22, 2019.

25. Perwien A, Hall J, Swensen A, et al. Stimulant treatment patterns and compliance in children and adults with newly treated attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Manag Care Pharm. 2004;10(2):122-129.

26. Faraone SV, Biederman J, Zimmerman B. An analysis of patient adherence to treatment during a 1-year, open-label study of OROS methylphenidate in children with ADHD. J Atten Disord. 2007;11(2):157-166.

27. Barner JC, Khoza S, Oladapo A. ADHD medication use, adherence, persistence and cost among Texas Medicaid children. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(Suppl 2):13-22.

28. Brinkman WB, Baum R, Kelleher KJ, et al. Relationship between attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder care and medication continuity. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016;55(4):289-294.

29. Bokhari FAS, Heiland F, Levine P, et al. Risk factors for discontinuing drug therapy among children with ADHD. Health Services and Outcomes Research Methodology. 2008;8(3):134-158.

30. Thiruchelvam D, Charach A, Schachar RJ. Moderators and mediators of long-term adherence to stimulant treatment in children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(8):922-928.

31. DosReis S, Mychailyszyn MP, Evans-Lacko SE, et al. The meaning of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medication and parents’ initiation and continuity of treatment for their child. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(4):377-383.

32. dosReis S, Myers MA. Parental attitudes and involvement in psychopharmacological treatment for ADHD: a conceptual model. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2008;20(2):135-141.

33. Bussing R, Koro-Ljungberg M, Noguchi K, et al. Willingness to use ADHD treatments: a mixed methods study of perceptions by adolescents, parents, health professionals and teachers. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(1):92-100.

34. Brinkman WB, Sucharew H, Majcher JH, et al. Predictors of medication continuity in children with ADHD. Pediatrics. 2018;141(6). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-2580.

35. Coletti DJ, Pappadopulos E, Katsiotas NJ, et al. Parent perspectives on the decision to initiate medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(3):226-237.

36. Bussing R, Gary FA. Practice guidelines and parental ADHD treatment evaluations: friends or foes? Harv Rev Psychiatry. 2001;9(5):223-233.

37. Charach A, Gajaria A. Improving psychostimulant adherence in children with ADHD. Expert Rev Neurother. 2008;8(10):1563-1571.

38. Rieppi R, Greenhill LL, Ford RE, et al. Socioeconomic status as a moderator of ADHD treatment outcomes. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41(3):269-277.

39. Swanson JM, Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE, et al. Secondary evaluations of MTA 36-month outcomes: propensity score and growth mixture model analyses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(8):1003-1014.

40. Gau SS, Shen HY, Chou MC, et al. Determinants of adherence to methylphenidate and the impact of poor adherence on maternal and family measures. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2006;16(3):286-297.

41. Barkley RA, Fischer M, Edelbrock C, et al. The adolescent outcome of hyperactive children diagnosed by research criteria--III. Mother-child interactions, family conflicts and maternal psychopathology. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1991;32(2):233-255.

42. Kashdan TB, Jacob RG, Pelham WE, et al. Depression and anxiety in parents of children with ADHD and varying levels of oppositional defiant behaviors: modeling relationships with family functioning. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33(1):169-181.

43. Chavira DA, Stein MB, Bailey K, et al. Parental opinions regarding treatment for social anxiety disorder in youth. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2003;24(5):315-322.

44. Leslie LK, Aarons GA, Haine RA, et al. Caregiver depression and medication use by youths with ADHD who receive services in the public sector. Psychiatr Serv. 2007;58(1):131-134.

45. Barbaresi WJ, Katusic SK, Colligan RC, et al. Long-term stimulant medication treatment of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: results from a population-based study. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2006;27(1):1-10.

46. Atzori P, Usala T, Carucci S, et al. Predictive factors for persistent use and compliance of immediate-release methylphenidate: a 36-month naturalistic study. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(6):673-681.

47. Chen CY, Yeh HH, Chen KH, et al. Differential effects of predictors on methylphenidate initiation and discontinuation among young people with newly diagnosed attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2011;21(3):265-273.

48. Winterstein AG, Gerhard T, Shuster J, et al. Utilization of pharmacologic treatment in youths with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder in Medicaid database. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42(1):24-31.

49. Marcus SC, Wan GJ, Kemner JE, et al. Continuity of methylphenidate treatment for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(6):572-578.

50. Cummings JR JX, Allen L, Lally C, et al. Racial and ethnic differences in ADHD treatment quality among Medicaid-enrolled youth. Pediatrics. 2017;139(6):e2016-e2044.

51. Hudson JL, Miller GE, Kirby JB. Explaining racial and ethnic differences in children’s use of stimulant medications. Med Care. 2007;45(11):1068-1075.

52. van den Ban E, Souverein PC, Swaab H, et al. Less discontinuation of ADHD drug use since the availability of long-acting ADHD medication in children, adolescents and adults under the age of 45 years in the Netherlands. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2010;2(4):213-220.

53. Charach A, Ickowicz A, Schachar R. Stimulant treatment over five years: adherence, effectiveness, and adverse effects. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(5):559-567.

54. Toomey SL, Sox CM, Rusinak D, et al. Why do children with ADHD discontinue their medication? Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2012;51(8):763-769.

55. Brinkman WB, Simon JO, Epstein JN. Reasons why children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder stop and restart taking medicine. Acad Pediatr. 2018;18(3):273-280.

56. Wehmeier PM, Dittmann RW, Banaschewski T. Treatment compliance or medication adherence in children and adolescents on ADHD medication in clinical practice: results from the COMPLY observational study. Atten Defic Hyperact Disord. 2015;7(2):165-174.

57. Frank E, Ozon C, Nair V, et al. Examining why patients with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder lack adherence to medication over the long term: a review and analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1459-e1468.

58. Pozzi M, Carnovale C, Peeters G, et al. Adverse drug events related to mood and emotion in paediatric patients treated for ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Affect Disord. 2018;238:161-178.

59. Stuckelman ZD, Mulqueen JM, Ferracioli-Oda E, et al. Risk of irritability with psychostimulant treatment in children with ADHD: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(6):e648-e655.

60. Cortese S, Adamo N, Del Giovane C, et al. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of medications for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in children, adolescents, and adults: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5(9):727-738.

61. Lawson KA, Johnsrud M, Hodgkins P, et al. Utilization patterns of stimulants in ADHD in the Medicaid population: a retrospective analysis of data from the Texas Medicaid program. Clin Ther. 2012;34(4):944-956 e944.

62. Olfson M, Marcus S, Wan G. Stimulant dosing for children with ADHD: a medical claims analysis. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(1):51-59.

63. Jensen PS, Arnold LE, Swanson JM, et al. 3-year follow-up of the NIMH MTA study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2007;46(8):989-1002.

64. Van Cleave J, Leslie LK. Approaching ADHD as a chronic condition: implications for long-term adherence. Pediatr Ann. 2008;37(1):19-26.

65. Leslie LK, Plemmons D, Monn AR, et al. Investigating ADHD treatment trajectories: listening to families’ stories about medication use. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2007;28(3):179-188.

66. Fiks AG, Mayne S, Localio AR, et al. Shared decision making and behavioral impairment: a national study among children with special health care needs. BMC Pediatr. 2012;12:153.

67. Stevens J, Harman JS, Kelleher KJ. Race/ethnicity and insurance status as factors associated with ADHD treatment patterns. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15(1):88-96.

68. Charach A, Skyba A, Cook L, et al. Using stimulant medication for children with ADHD: what do parents say? A brief report. J Can Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2006;15(2):75-83.

69. Chen CY, Gerhard T, Winterstein AG. Determinants of initial pharmacological treatment for youths with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Child Adolescent Psychopharmacol. 2009;19(2):187-195.

70. National Council on Patient Information and Education. Enhancing prescription medication adherence: a national action plan. http://www.bemedwise.org/docs/enhancingprescriptionmedicineadherence.pdf. Published August 2007. Accessed July 22, 2019.

71. Kahana S, Drotar D, Frazier T. Meta-analysis of psychological interventions to promote adherence to treatment in pediatric chronic health conditions. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33(6):590-611.

72. Johnston C, Mash EJ. Families of children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: review and recommendations for future research. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2001;4(3):183-207.

73. Chronis AM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE Jr., et al. Psychopathology and substance abuse in parents of young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2003;42(12):1424-1432.

74. Chacko A, Newcorn JH, Feirsen N, et al. Improving medication adherence in chronic pediatric health conditions: a focus on ADHD in youth. Curr Pharm Des. 2010;16(22):2416-2423.