User login

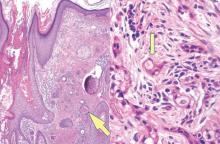

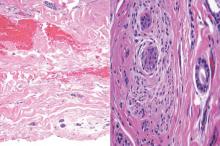

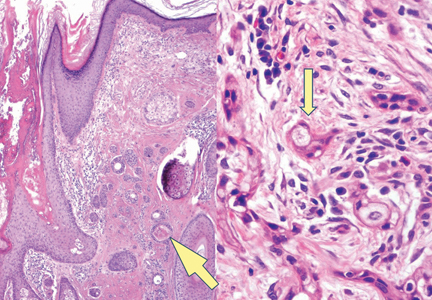

Syringoid eccrine carcinoma is a rare malignant adnexal tumor with eccrine differentiation that histologically resembles a syringoma.1 Originally described as eccrine epithelioma by Freeman and Winklemann2 in 1969, syringoid eccrine carcinoma has been reported in the literature as eccrine carcinoma, eccrine syringomatous carcinoma, and sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma.3 Clinically, syringoid eccrine carcinoma most commonly presents as a tender plaque or nodule on the scalp, and histologic examination generally reveals a dermal-based lesion that rarely shows epidermal connection. It demonstrates syringomalike tadpole morphology (epithelial strands with lumen formation) composed of basaloid epithelium with uniform hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). There usually is an infiltrative growth pattern to the subcutis (Figure 2 [left]) or skeletal muscle as well as remarkable perineural invasion (Figure 2 [right]). Mitotic activity is minimal to absent. The tumor cells of syringoid eccrine carcinoma typically show positive immuno-staining for high- and low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, while the lumina are highlighted by epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen.4 However, immunohistochemistry often is not contributory in diagnosing primary eccrine carcinomas.

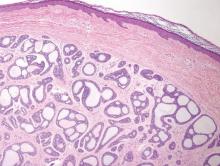

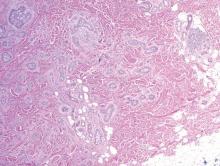

The differential diagnosis of syringoid eccrine carcinoma includes cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma, sclerosing basal cell carcinoma, and syringoma. Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare, slow-growing, flesh-colored tumor that consists of lobules, islands, and cords of basaloid cells with prominent cystic cribriforming (Figure 3). The tumor cells typically are small, cuboidal, and monomorphic. Metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma, such as from a primary tumor of the salivary glands or breasts, must be excluded before rendering a diagnosis of primary cutaneous disease.

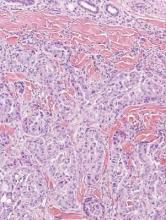

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin usually presents in patients with a clinical history of preexisting disease. The breasts, colon, stomach, and ovaries are common origins of metastases. The histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings depend on the particular site of origin of the metastasis. Compared with primary eccrine carcinomas, metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin generally are high-grade lesions with prominent atypia, mitosis, and necrosis (Figure 4).

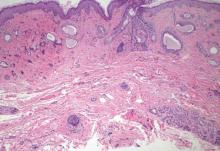

Sclerosing basal cell carcinoma shows basaloid tumor cells with deep infiltration. Unlike syringoid eccrine carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma is an epidermal tumor that does not have true lumen formation. Furthermore, other variants of basal cell carcinoma, including nodular, micronodular, or superficial multicentric tumors, often coexist with the sclerosing variant in the same lesion and constitute a useful diagnostic clue (Figure 5). Staining for epithelial membrane antigen may be useful in identifying the absence of lumen formation, and Ber-EP4 highlights the epidermal origin of the lesion.5

Syringomas most commonly present as multiple small flesh-colored papules on the eyelids. On histology, syringomas present as small superficial dermal lesions composed of small ducts that may form tadpolelike structures in a fibrotic stroma (Figure 6). The ducts are lined by benign cuboidal cells. In contrast to syringoid eccrine carcinomas, syringomas usually present as multiple lesions that are microscopically superficial without perineural involvement.

1. Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

2. Freeman RG, Winklemann RK. Basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiations (eccrine epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:234-242.

3. Nishizawa A, Nakanishi Y, Sasajima Y, et al. Syringoid carcinoma with apparently aggressive transformation: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1218-1221.

4. Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, et al. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:498-505.

5. Cassarino D. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys Publishing Inc; 2012.

Syringoid eccrine carcinoma is a rare malignant adnexal tumor with eccrine differentiation that histologically resembles a syringoma.1 Originally described as eccrine epithelioma by Freeman and Winklemann2 in 1969, syringoid eccrine carcinoma has been reported in the literature as eccrine carcinoma, eccrine syringomatous carcinoma, and sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma.3 Clinically, syringoid eccrine carcinoma most commonly presents as a tender plaque or nodule on the scalp, and histologic examination generally reveals a dermal-based lesion that rarely shows epidermal connection. It demonstrates syringomalike tadpole morphology (epithelial strands with lumen formation) composed of basaloid epithelium with uniform hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). There usually is an infiltrative growth pattern to the subcutis (Figure 2 [left]) or skeletal muscle as well as remarkable perineural invasion (Figure 2 [right]). Mitotic activity is minimal to absent. The tumor cells of syringoid eccrine carcinoma typically show positive immuno-staining for high- and low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, while the lumina are highlighted by epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen.4 However, immunohistochemistry often is not contributory in diagnosing primary eccrine carcinomas.

The differential diagnosis of syringoid eccrine carcinoma includes cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma, sclerosing basal cell carcinoma, and syringoma. Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare, slow-growing, flesh-colored tumor that consists of lobules, islands, and cords of basaloid cells with prominent cystic cribriforming (Figure 3). The tumor cells typically are small, cuboidal, and monomorphic. Metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma, such as from a primary tumor of the salivary glands or breasts, must be excluded before rendering a diagnosis of primary cutaneous disease.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin usually presents in patients with a clinical history of preexisting disease. The breasts, colon, stomach, and ovaries are common origins of metastases. The histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings depend on the particular site of origin of the metastasis. Compared with primary eccrine carcinomas, metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin generally are high-grade lesions with prominent atypia, mitosis, and necrosis (Figure 4).

Sclerosing basal cell carcinoma shows basaloid tumor cells with deep infiltration. Unlike syringoid eccrine carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma is an epidermal tumor that does not have true lumen formation. Furthermore, other variants of basal cell carcinoma, including nodular, micronodular, or superficial multicentric tumors, often coexist with the sclerosing variant in the same lesion and constitute a useful diagnostic clue (Figure 5). Staining for epithelial membrane antigen may be useful in identifying the absence of lumen formation, and Ber-EP4 highlights the epidermal origin of the lesion.5

Syringomas most commonly present as multiple small flesh-colored papules on the eyelids. On histology, syringomas present as small superficial dermal lesions composed of small ducts that may form tadpolelike structures in a fibrotic stroma (Figure 6). The ducts are lined by benign cuboidal cells. In contrast to syringoid eccrine carcinomas, syringomas usually present as multiple lesions that are microscopically superficial without perineural involvement.

Syringoid eccrine carcinoma is a rare malignant adnexal tumor with eccrine differentiation that histologically resembles a syringoma.1 Originally described as eccrine epithelioma by Freeman and Winklemann2 in 1969, syringoid eccrine carcinoma has been reported in the literature as eccrine carcinoma, eccrine syringomatous carcinoma, and sclerosing sweat duct carcinoma.3 Clinically, syringoid eccrine carcinoma most commonly presents as a tender plaque or nodule on the scalp, and histologic examination generally reveals a dermal-based lesion that rarely shows epidermal connection. It demonstrates syringomalike tadpole morphology (epithelial strands with lumen formation) composed of basaloid epithelium with uniform hyperchromatic nuclei (Figure 1). There usually is an infiltrative growth pattern to the subcutis (Figure 2 [left]) or skeletal muscle as well as remarkable perineural invasion (Figure 2 [right]). Mitotic activity is minimal to absent. The tumor cells of syringoid eccrine carcinoma typically show positive immuno-staining for high- and low-molecular-weight cytokeratin, while the lumina are highlighted by epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen.4 However, immunohistochemistry often is not contributory in diagnosing primary eccrine carcinomas.

The differential diagnosis of syringoid eccrine carcinoma includes cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma, metastatic adenocarcinoma, sclerosing basal cell carcinoma, and syringoma. Cutaneous adenoid cystic carcinoma is a rare, slow-growing, flesh-colored tumor that consists of lobules, islands, and cords of basaloid cells with prominent cystic cribriforming (Figure 3). The tumor cells typically are small, cuboidal, and monomorphic. Metastatic adenoid cystic carcinoma, such as from a primary tumor of the salivary glands or breasts, must be excluded before rendering a diagnosis of primary cutaneous disease.

Metastatic adenocarcinoma of the skin usually presents in patients with a clinical history of preexisting disease. The breasts, colon, stomach, and ovaries are common origins of metastases. The histopathologic and immunohistochemical findings depend on the particular site of origin of the metastasis. Compared with primary eccrine carcinomas, metastatic adenocarcinomas of the skin generally are high-grade lesions with prominent atypia, mitosis, and necrosis (Figure 4).

Sclerosing basal cell carcinoma shows basaloid tumor cells with deep infiltration. Unlike syringoid eccrine carcinoma, basal cell carcinoma is an epidermal tumor that does not have true lumen formation. Furthermore, other variants of basal cell carcinoma, including nodular, micronodular, or superficial multicentric tumors, often coexist with the sclerosing variant in the same lesion and constitute a useful diagnostic clue (Figure 5). Staining for epithelial membrane antigen may be useful in identifying the absence of lumen formation, and Ber-EP4 highlights the epidermal origin of the lesion.5

Syringomas most commonly present as multiple small flesh-colored papules on the eyelids. On histology, syringomas present as small superficial dermal lesions composed of small ducts that may form tadpolelike structures in a fibrotic stroma (Figure 6). The ducts are lined by benign cuboidal cells. In contrast to syringoid eccrine carcinomas, syringomas usually present as multiple lesions that are microscopically superficial without perineural involvement.

1. Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

2. Freeman RG, Winklemann RK. Basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiations (eccrine epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:234-242.

3. Nishizawa A, Nakanishi Y, Sasajima Y, et al. Syringoid carcinoma with apparently aggressive transformation: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1218-1221.

4. Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, et al. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:498-505.

5. Cassarino D. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys Publishing Inc; 2012.

1. Sidiropoulos M, Sade S, Al-Habeeb A, et al. Syringoid eccrine carcinoma: a clinicopathological and immunohistochemical study of four cases. J Clin Pathol. 2011;64:788-792.

2. Freeman RG, Winklemann RK. Basal cell tumor with eccrine differentiations (eccrine epithelioma). Arch Dermatol. 1969;100:234-242.

3. Nishizawa A, Nakanishi Y, Sasajima Y, et al. Syringoid carcinoma with apparently aggressive transformation: case report and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2006;45:1218-1221.

4. Urso C, Bondi R, Paglierani M, et al. Carcinomas of sweat glands: report of 60 cases. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2001;125:498-505.

5. Cassarino D. Diagnostic Pathology: Neoplastic Dermatopathology. Salt Lake City, UT: Amirsys Publishing Inc; 2012.