User login

CHICAGO – Systematic implementation of a comprehensive telephone CPR bundle of care targeting EMS dispatch services resulted in substantial improvements in rates of survival to hospital discharge with good neurologic outcomes in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in a major Arizona statewide public health initiative.

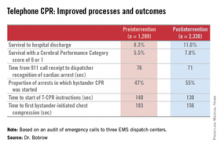

How big was the intervention’s impact? The rate of survival to hospital discharge showed a 33% relative increase compared to preintervention, and survival with a favorable Cerebral Performance Category score of 0 or 1 increased by 42%, Dr. Bentley J. Bobrow reported at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“These results suggest that when deliberately implemented and measured, telephone CPR is a targeted, effective method to increase bystander CPR and survival on a vast scale with minimal capital expense. This is why we believe telephone CPR along with public training may be the most efficient way to move the needle on cardiac arrest survival,” declared Dr. Bobrow, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix Campus and chair of the AHA Basic Life Support Subcommittee.

Telephone CPR (T-CPR) entails the provision of CPR instruction to bystanders who have called 911 regarding an out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). It’s well established that bystander CPR commenced before EMS personnel arrive on the scene doubles or even triples OHCA survival, but it is provided in only about one-third of OHCA events. And while T-CPR is independently associated with increased rates of bystander CPR as well as patient survival, its utilization varies widely throughout the country and few EMS services measure performance.

Dr. Bobrow reported on an ambitious undertaking that involved systematic training in T-CPR for dispatchers, 911 managers, and medical directors at all nine of the regional emergency dispatch centers in Arizona, which together with 190 EMS agencies and 40 cardiac care hospitals participate in a statewide resuscitation program.

The training was designed to implement the latest AHA guidelines on T-CPR (Circulation 2012;125:648-55). The program entailed a half-day in-person training session plus completion of a 1-hour web-based interactive video. The protocol emphasizes asking two key questions of the 911 caller: “Is the patient conscious?” and “Is the patient breathing normally?” If the response is no to both, the dispatcher is to start issuing bystander CPR instructions without delay – no further questions – and continue the coaching until EMS personnel arrive on the scene to take over.

A core aspect of the T-CPR bundle is performance measurement for quality improvement, with auditing of 911 calls to learn the time from the start of the call to the bystander’s first chest compression and five other key performance metrics. Feedback is provided to the 911 call center regarding system- and case-level performance reports in a continuing education, quality improvement process. Individual dispatchers are singled out for exemplary performance, Dr. Bobrow explained.

He presented a prospective before-and-after study conducted at the three EMS dispatch centers serving Arizona’s Maricopa County, home to two-thirds of the state’s population. The study entailed auditing nearly 6,000 911 calls, each averaging 6.5 minutes in length. After excluding calls where CPR wasn’t indicated or the OHCA involved a patient less than 8 years old, investigators were left with two groups for comparison comprised of 1,289 pre- and 2,330 post-intervention events.

The improvements in process and clinical outcomes were dramatic. In 2012, after introduction of the T-CPR training program, the bystander CPR rate crossed the 50% threshold for the first time ever in Maricopa County. The rate of survival of OHCA to hospital discharge improved from 8.3% to 11%, a highly statistically significant 33% relative increase. Survival with a Cerebral Performance Category score of 0 or 1 climbed from 5.5% to 7.8%, a 42% relative increase. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the adjusted odds ratio for survival of OHCA was 2.25-fold greater for all cases after implementation of the T-CPR program and similarly increased for arrests of cardiac origin.

Dr. Bobrow observed that this was not a randomized trial, which he considered would be both unethical and impractical.

“We controlled for known risk factors and confounders, and while we cannot prove that better outcomes resulted directly from the process improvements, the two are independently associated in this controlled study,” said the emergency physician, who is medical director of the Bureau of Emergency Medical Services and Trauma Systems at the Arizona Dept. of Health Services.

Audience members rose to praise the “fantastic” achievements in Arizona and ask why they’re not having similar success rates in their own districts, given that the AHA guidelines are readily available.

“A lot of places say they’re doing this,” Dr. Bobrow replied, “but when they realize what ‘this’ is, they understand that they really weren’t doing it in this type of depth. When we showed them the data on how marginal their performance was, I think that really made the difference.”

“I think that once most dispatch centers really understand the issues and their importance and the power that they have, and you can engage them, I’m confident that people would see the same changes,” he added.

His study was honored as the best oral abstract presentation at the AHA resuscitation science symposium.

Dr. Bobrow reported serving as co-principal investigator of the HeartRescue Project, funded by Medtronic Philanthropy.

CHICAGO – Systematic implementation of a comprehensive telephone CPR bundle of care targeting EMS dispatch services resulted in substantial improvements in rates of survival to hospital discharge with good neurologic outcomes in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in a major Arizona statewide public health initiative.

How big was the intervention’s impact? The rate of survival to hospital discharge showed a 33% relative increase compared to preintervention, and survival with a favorable Cerebral Performance Category score of 0 or 1 increased by 42%, Dr. Bentley J. Bobrow reported at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“These results suggest that when deliberately implemented and measured, telephone CPR is a targeted, effective method to increase bystander CPR and survival on a vast scale with minimal capital expense. This is why we believe telephone CPR along with public training may be the most efficient way to move the needle on cardiac arrest survival,” declared Dr. Bobrow, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix Campus and chair of the AHA Basic Life Support Subcommittee.

Telephone CPR (T-CPR) entails the provision of CPR instruction to bystanders who have called 911 regarding an out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). It’s well established that bystander CPR commenced before EMS personnel arrive on the scene doubles or even triples OHCA survival, but it is provided in only about one-third of OHCA events. And while T-CPR is independently associated with increased rates of bystander CPR as well as patient survival, its utilization varies widely throughout the country and few EMS services measure performance.

Dr. Bobrow reported on an ambitious undertaking that involved systematic training in T-CPR for dispatchers, 911 managers, and medical directors at all nine of the regional emergency dispatch centers in Arizona, which together with 190 EMS agencies and 40 cardiac care hospitals participate in a statewide resuscitation program.

The training was designed to implement the latest AHA guidelines on T-CPR (Circulation 2012;125:648-55). The program entailed a half-day in-person training session plus completion of a 1-hour web-based interactive video. The protocol emphasizes asking two key questions of the 911 caller: “Is the patient conscious?” and “Is the patient breathing normally?” If the response is no to both, the dispatcher is to start issuing bystander CPR instructions without delay – no further questions – and continue the coaching until EMS personnel arrive on the scene to take over.

A core aspect of the T-CPR bundle is performance measurement for quality improvement, with auditing of 911 calls to learn the time from the start of the call to the bystander’s first chest compression and five other key performance metrics. Feedback is provided to the 911 call center regarding system- and case-level performance reports in a continuing education, quality improvement process. Individual dispatchers are singled out for exemplary performance, Dr. Bobrow explained.

He presented a prospective before-and-after study conducted at the three EMS dispatch centers serving Arizona’s Maricopa County, home to two-thirds of the state’s population. The study entailed auditing nearly 6,000 911 calls, each averaging 6.5 minutes in length. After excluding calls where CPR wasn’t indicated or the OHCA involved a patient less than 8 years old, investigators were left with two groups for comparison comprised of 1,289 pre- and 2,330 post-intervention events.

The improvements in process and clinical outcomes were dramatic. In 2012, after introduction of the T-CPR training program, the bystander CPR rate crossed the 50% threshold for the first time ever in Maricopa County. The rate of survival of OHCA to hospital discharge improved from 8.3% to 11%, a highly statistically significant 33% relative increase. Survival with a Cerebral Performance Category score of 0 or 1 climbed from 5.5% to 7.8%, a 42% relative increase. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the adjusted odds ratio for survival of OHCA was 2.25-fold greater for all cases after implementation of the T-CPR program and similarly increased for arrests of cardiac origin.

Dr. Bobrow observed that this was not a randomized trial, which he considered would be both unethical and impractical.

“We controlled for known risk factors and confounders, and while we cannot prove that better outcomes resulted directly from the process improvements, the two are independently associated in this controlled study,” said the emergency physician, who is medical director of the Bureau of Emergency Medical Services and Trauma Systems at the Arizona Dept. of Health Services.

Audience members rose to praise the “fantastic” achievements in Arizona and ask why they’re not having similar success rates in their own districts, given that the AHA guidelines are readily available.

“A lot of places say they’re doing this,” Dr. Bobrow replied, “but when they realize what ‘this’ is, they understand that they really weren’t doing it in this type of depth. When we showed them the data on how marginal their performance was, I think that really made the difference.”

“I think that once most dispatch centers really understand the issues and their importance and the power that they have, and you can engage them, I’m confident that people would see the same changes,” he added.

His study was honored as the best oral abstract presentation at the AHA resuscitation science symposium.

Dr. Bobrow reported serving as co-principal investigator of the HeartRescue Project, funded by Medtronic Philanthropy.

CHICAGO – Systematic implementation of a comprehensive telephone CPR bundle of care targeting EMS dispatch services resulted in substantial improvements in rates of survival to hospital discharge with good neurologic outcomes in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest in a major Arizona statewide public health initiative.

How big was the intervention’s impact? The rate of survival to hospital discharge showed a 33% relative increase compared to preintervention, and survival with a favorable Cerebral Performance Category score of 0 or 1 increased by 42%, Dr. Bentley J. Bobrow reported at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“These results suggest that when deliberately implemented and measured, telephone CPR is a targeted, effective method to increase bystander CPR and survival on a vast scale with minimal capital expense. This is why we believe telephone CPR along with public training may be the most efficient way to move the needle on cardiac arrest survival,” declared Dr. Bobrow, professor of emergency medicine at the University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix Campus and chair of the AHA Basic Life Support Subcommittee.

Telephone CPR (T-CPR) entails the provision of CPR instruction to bystanders who have called 911 regarding an out of hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA). It’s well established that bystander CPR commenced before EMS personnel arrive on the scene doubles or even triples OHCA survival, but it is provided in only about one-third of OHCA events. And while T-CPR is independently associated with increased rates of bystander CPR as well as patient survival, its utilization varies widely throughout the country and few EMS services measure performance.

Dr. Bobrow reported on an ambitious undertaking that involved systematic training in T-CPR for dispatchers, 911 managers, and medical directors at all nine of the regional emergency dispatch centers in Arizona, which together with 190 EMS agencies and 40 cardiac care hospitals participate in a statewide resuscitation program.

The training was designed to implement the latest AHA guidelines on T-CPR (Circulation 2012;125:648-55). The program entailed a half-day in-person training session plus completion of a 1-hour web-based interactive video. The protocol emphasizes asking two key questions of the 911 caller: “Is the patient conscious?” and “Is the patient breathing normally?” If the response is no to both, the dispatcher is to start issuing bystander CPR instructions without delay – no further questions – and continue the coaching until EMS personnel arrive on the scene to take over.

A core aspect of the T-CPR bundle is performance measurement for quality improvement, with auditing of 911 calls to learn the time from the start of the call to the bystander’s first chest compression and five other key performance metrics. Feedback is provided to the 911 call center regarding system- and case-level performance reports in a continuing education, quality improvement process. Individual dispatchers are singled out for exemplary performance, Dr. Bobrow explained.

He presented a prospective before-and-after study conducted at the three EMS dispatch centers serving Arizona’s Maricopa County, home to two-thirds of the state’s population. The study entailed auditing nearly 6,000 911 calls, each averaging 6.5 minutes in length. After excluding calls where CPR wasn’t indicated or the OHCA involved a patient less than 8 years old, investigators were left with two groups for comparison comprised of 1,289 pre- and 2,330 post-intervention events.

The improvements in process and clinical outcomes were dramatic. In 2012, after introduction of the T-CPR training program, the bystander CPR rate crossed the 50% threshold for the first time ever in Maricopa County. The rate of survival of OHCA to hospital discharge improved from 8.3% to 11%, a highly statistically significant 33% relative increase. Survival with a Cerebral Performance Category score of 0 or 1 climbed from 5.5% to 7.8%, a 42% relative increase. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for potential confounders, the adjusted odds ratio for survival of OHCA was 2.25-fold greater for all cases after implementation of the T-CPR program and similarly increased for arrests of cardiac origin.

Dr. Bobrow observed that this was not a randomized trial, which he considered would be both unethical and impractical.

“We controlled for known risk factors and confounders, and while we cannot prove that better outcomes resulted directly from the process improvements, the two are independently associated in this controlled study,” said the emergency physician, who is medical director of the Bureau of Emergency Medical Services and Trauma Systems at the Arizona Dept. of Health Services.

Audience members rose to praise the “fantastic” achievements in Arizona and ask why they’re not having similar success rates in their own districts, given that the AHA guidelines are readily available.

“A lot of places say they’re doing this,” Dr. Bobrow replied, “but when they realize what ‘this’ is, they understand that they really weren’t doing it in this type of depth. When we showed them the data on how marginal their performance was, I think that really made the difference.”

“I think that once most dispatch centers really understand the issues and their importance and the power that they have, and you can engage them, I’m confident that people would see the same changes,” he added.

His study was honored as the best oral abstract presentation at the AHA resuscitation science symposium.

Dr. Bobrow reported serving as co-principal investigator of the HeartRescue Project, funded by Medtronic Philanthropy.

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: Adoption of the most recent AHA guidelines on telephone CPR by EMS dispatchers will lead to vast improvement in survival for patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest.

Major finding: Following implementation of an Arizona statewide program to improve telephone CPR by 911 dispatchers to bystanders at the scene of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest, survival to hospital discharge climbed from 8.3% to 11.0%.

Data source: This was a prospective study comparing the outcomes of 1,289 calls to Arizona 911 centers regarding out-of-hospital cardiac arrests before introduction of a comprehensive statewide telephone CPR program to 2,330 calls received post-intervention.

Disclosures: The study was financially supported by Medtronic Philanthropy as part of the HeartRescue Project. The presenter is co-principal investigator of the project.