User login

From the Jewish Family and Children’s Service, Phoenix, AZ (Dr. Henderson) and Consult-Stat, Macungie, PA (Ms. Wasser, Dr. Wasser).

Abstract

- Background: The reliability and validity of the Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument (CASII) as a tool to help determine needed level of care for children with behavioral health needs has previously been established.

- Objective: To determine the utility of the CASII as an outcome measure.

- Methods: A sample consisting of all clients (n = 8465) admitted to service at an outpatient beha

vioral health facility from 2013 through 2016 were studied. CASII was administered at admission and discharge and ratings were compared with paired t-tests within demographic and diagnosis groups. - Results: Mean CASII composite ratings decreased between admission and discharge in the entire cohort as well as within gender, age group, and multiple diagnosis groups tested.

- Conclusion: CASII was useful as an outcome measure in our relatively low to moderate acuity population.

Keywords: outcomes, evidence based practice, child psychology, outpatient research.

The primary goal of mental health services is to provide interventions that result in a reduction of problematic symptomatology [1]; therefore, evaluation of those interventions is important for both the client as well as the stakeholders of the organization providing them. Health care payment reforms require tracking quality measures, and such measures directly influence the development, administration, and monitoring of mental health programs as well as specific treatment modalities [2,3]. Organizations are more likely to benefit when outcomes measures are relayed quantitatively [4]. In addition, clients are becoming more informed regarding the quality of care, and outcomes assessments can inform clients that programs are delivering the most efficacious therapies based on current evidence-based practice standards.

Developing outcomes assessments in behavioral health is challenging [5–7]. There are numerous potential outcome domains that can be assessed as well as different ways of measuring them. Futher, evaluating treatment can be expensive, with components including developing a tool, training staff to administer the tool, ensuring the necessary technical support to store and process the data, interpretation of the data, compiling reports, and communicating results to clients and providers [5]. Being mindful of these components and their associated costs, our organization considered whether a tool we currently use to assess the appropriate intensity of service needed for an individual could also be used as an outcome measure.

Therapeutic methods for children in our organization consist of a “system of care” approach designed by a treatment team that incorporates varied methods depending on the needs of the child. The primary goal is to prevent children with traumatic-based disorders from developing continuing disorders associated with their experiences, such as substance use and chronic health and mental health disorders. Our organization currently uses the CASII (Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument) to assess the appropriate level of intensity of service needed by the child. The CASII incorporates holistic information on the child, within the context of his/her family and social ecology, assessing across 6 dimensions: risk of harm (including trauma issues), functional status, co-occurring conditions, recovery environment, resiliency/response to services, and involvement in services.

In order to comply with the call to consider outcomes measurement and evidence based practice as an integral component of children’s mental health services, this study was performed. It examines the use of the CASII as an outcomes measure based on the rationale that a decreased level of care upon discharge would correlate with a positive outcome by proxy.

Methods

CASII Instrument

The CASII is a decision support tool to help the service provider determine the intensity of services that a child should have to adequately address their behavioral health needs. The CASII has a strong evidence base supporting its reliability and validity [8], and has gained wide usage in a range of health care settings over the past 13 years [9–11].

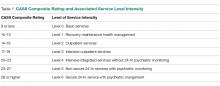

As mentioned, the CASII assesses the client across 6 key dimensions: risk of harm (including trauma issues), functional status, co-occurring conditions, recovery environment, resiliency/response to services, and involvement in services. Each dimension is scored along a 5-point rating scale, and a total or composite rating is calculated by adding the scores for each dimension. The composite rating corresponds with the level of service intensity needed. There are 7 levels of service intensity, ranging from Level 0 (corresponding with a composite rating of 9 or less) to Level 6 (corresponding with a composite rating of 28 or more) (Table 1).

Study Sample

The sample consisted of all clients (n = 8465) admitted to service from 2013 through 2016 to our facility. Our facility is an outpatient facility offering counseling, mental health assessment and treatment, early childhood trauma assessment, child crisis interventions and rehabilitation for domestic violence, child abuse and neglect, and substance abuse. All clients between the ages of 6 and 17 are assessed with the CASII on admission and then at 6-month intervals until discharge from the program. Being discharged from the program of care prompts the completion of the discharge CASII. If the client had been rated within the 30 days prior to discharge the most recent CASII is used as the discharge measure.

Data Analysis

Data for all admissions from 2013 and 2016 were extracted from the organization’s computer system into an Excel file. The data collected included gender, calendar year of admission to the program, age, and diagnosis group based on the discharge diagnosis given by the mental health team, and whether the client was a participant in the Youth in Transition (YIT) program (program for older clients that includes life skills training in addition to standard therapy). The CASII composite rating at baseline and discharge as well as ratings for each of the 6 dimensions assessed with the CASII were also collected.

We used SPSS (v25.01) software for statistical analysis. Analysis included paired (pre-post) t-tests that were applied to the entire cohort as well as within gender, age group, participation in the YIT program, and diagnosis groups. Diagnosis groups were included only if the frequency of cases within the group was large enough to meet the sample size requirements of central limit theorem (in general, n > 25), with 2 exceptions: schizophrenia spectrum was included because of the rarity of the diagnosis (n = 11) and neurodevelopmental disorders (also n = 11) was included because there was no violation of the equal variance assumption as well as interest to the investigators. In addition to the paired analysis, we used group t tests to determine if there were severity differences between groups at baseline. Lastly, we assessed change from admission to discharge for each of the 6 dimensions that make up the composite rating.

We designated the 7 levels of care defined by the CASII as continuous in nature, and therefore computations of means and standard deviations (SD) are appropriate for assessment. The interpretation of the CASII composite rating and the level of care as a continuous variable has also been reported in the literature [11,12].

The research and analysis was viewed as exploratory in nature and a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. There was no correction for multiple comparisons applied to the data in order to not mask any observed differences in the data. All analyses were 2-tailed. If any individual had a missing value for either an admission or discharge CASII assessment they were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Results

There were 8465 clients admitted from 2013 and 2016. The sample was predominantly male (54.5%), and the majority fell into the older 12–17 year old cohort (54.0%). Admissions were evenly distributed across the 4 years that we studied, with the lowest percentage in 2013 at 23.4% and the highest in 2014 at 26.0%. Discharge diagnosis was available for the majority of the cohort. The top 5 most frequent diagnosis groups were adjustment disorders (n = 807, 18.3%), ADHD (n = 798, 18.1%), child neglect (n = 775, 17.6%), mood disorders (n = 602, 13.6%), and impulse disorders (n = 262, 5.9%). There were 232 (2.7%) clients that participated in the YIT program. Table 2

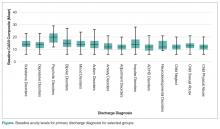

At admission, several groups had higher mean composite ratings. Males had higher ratings (in need of higher level of service intensity) than females (P < 0.001), 12–17 year olds had a significantly higher acuity level than 6–11 year olds (P < 0.001), and clients in the YIT program had a higher acuity level than those not in the YIT program (P = 0.001). Baseline acuity levels for primary discharge diagnosis for selected groups are shown in the Figure.

When analyzing the entire cohort for which data were available (n = 6944), the mean CASII composite rating dropped from 13.23 (± 4.35 SD) to 12.04 (± 3.84 SD), P < 0.001. Excluding youth that participated in YIT, the mean CASII score dropped from 13.21 (± 4.33) at admission to 13.17 (± 4.52) at discharge. Mean composite rating for clients participating in the YIT program dropped from 14.31 (± 5.12) at admission to 13.17 (± 4.52) at discharge (P = 0.022). For diagnosis groups, statistically significant reduction in mean CASII composite rating was observed for all groups except neurodevelopmentall disorders (P = 0.166). The results for all groups and diagnosis cohorts can be found in Table 3.

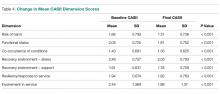

As noted, the CASII assesses the client across 6 dimensions, each of which is scored along a 5-point rating scale, and the composite rating is calculated by adding the scores for each dimension. Table 4 shows the change in mean dimension scores from baseline to discharge for these dimensions. Mean scores improved significantly (all P < 0.001).

Discussion

Organizations that provide mental health services are burdened with a complicated milieu of providing the best care possible in a complicated system of assessment, reimbursement, admissions/discharges, and a variety of other tasks. Using multiple measures complicates assessment and increases costs because of training staff, developing and interpreting the tool results, data storage and more comprehensive analysis and communication of results back to stakeholders and staff. Complicated measures are often times not understood by the staff and those responsible for care, nor are measures understood by the clients and their families. While a wide array of psychometric assessment tools exist, most are applicable to only specific diagnosis groups or illnesses.

Our study showed that the CASII may be used to monitor progress and reassess the level of service intensity needed, and therefore may be useful as an outcome measure. There are benefits in having a single score as an outcome measure. A single score for each client is quick and easy to understand by board members, staff of the organization as well as clients outside of the organization such as funders, client, press etc. Also the use of a single score is cost effective as costs for interpretation, training and communication within and outside of the organization are reduced.

A number of limitations must be mentioned. Although a change in score represents a change in client condition, this change in condition can have a wide variety of explanations. Change can be related to the therapy received, to changes in the client’s environment, support services, and many other factors. Our research did not allow us to discern what aspects of care may have reduced level of service intensity needed at discharge. In addition, our study involved clients of low and moderate acuity. The study does not address if CASII would be sensitive to change in upper acuity ranges. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable in these settings.

Tolan and Dodge [10] called for the enhancement or an elevation in the assessment of psychology as a matter of public policy. An approach that involves all levels of scientific inquiry including economics, political science and other sciences is desperately needed. Assessment of the type presented in this article, even if instruments such as the CASII are not used, can help to shape that policy by providing unquestionably accurate assessment of a client’s condition which demonstrates the need for that support. Further research looking at specific attributes of therapy and the client’s condition and environment may be helpful in applying CASII composite ratings and dimension scores as outcome measures.

Corresponding author: Dr. Lorrie Henderson, Jewish Family and Children’s Service, 4747 North 7th St., Suite 100, Phoenix, AZ 850142.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Thornicroft G, Slade M. New trends in assessing the outcomes of mental health interventions. World Psychiatry 2014;13:118.

2. England MJ, Butler AS, Gonzalez ML, editors. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Committee on Developing Evidence-Based Standards for Psychosocial Interventions for Mental Disorders; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2015 Sep 18.

3. Schurer Coldiron J, Hensley SW, Bruns EJ, Paragoris R. Putting the outcomes‐based principle into action part one: a guide for wraparound care coordinators; The National Technical Assistance Network for Children’s Behavioral Health. 2016. Available at: https://nwi.pdx.edu/pdf/Putting-the-Outcomes-Based-Principle-Into-Action.pdf.

4. Lachar D, Randle S, Harper R, et al. The brief psychiatric rating scale for children (BPRS-C): Validity and reliability of an anchored version. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry 2001;40:333–40.

5. Sperry L, Brill PL, Howard KI, Grissom GR. Treatment outcomes in psychotherapy and psychiatric interventions. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1996.

6. Burlingame GM, Lambert MJ, Reisinger CW, et al. Pragmatics of tracking mental health outcomes in a managed care setting. J Ment Health Adm 1995;22:226–36.

7. Henderson L, McIlhaney K, Wasser T. Measuring outcomes of multiple diagnosis groups in residential treatment using the brief psychiatric rating scale for children (BPRS-C). Children Youth Serv Rev 2008:24:243–59.

8. Fallon T Jr, Pumariega A, Sowers W, et al. A level of care instrument for children’s systems of care: Construction, reliability and validity. J Child Fam Studies 2006:15:143–155.

9. Minnesota Department of Human Services announcement. DHS updates requirement for standardized outcome measures for children’s mental health. #17-53-01. 27 Feb 2017.

10. Tolan P, Dodge K. Children’s mental health as a primary care and concern: a system for comprehensive support and service. Am Psychol 2005;60:601–14.

11. Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument (CASII) Overview for Anthem Connecticut Members. Accessed at www11.anthem.com/provider/ct/f3/s9/t1/pw_e205607.pdf?refer=ahpprovider.

12. Chenven M, Dominguez E, Grimes K, et al. CASII: Child and adolescent Service Intensity Instrument Background information and Initial Data Analysis. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Work Group June 2001.

From the Jewish Family and Children’s Service, Phoenix, AZ (Dr. Henderson) and Consult-Stat, Macungie, PA (Ms. Wasser, Dr. Wasser).

Abstract

- Background: The reliability and validity of the Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument (CASII) as a tool to help determine needed level of care for children with behavioral health needs has previously been established.

- Objective: To determine the utility of the CASII as an outcome measure.

- Methods: A sample consisting of all clients (n = 8465) admitted to service at an outpatient beha

vioral health facility from 2013 through 2016 were studied. CASII was administered at admission and discharge and ratings were compared with paired t-tests within demographic and diagnosis groups. - Results: Mean CASII composite ratings decreased between admission and discharge in the entire cohort as well as within gender, age group, and multiple diagnosis groups tested.

- Conclusion: CASII was useful as an outcome measure in our relatively low to moderate acuity population.

Keywords: outcomes, evidence based practice, child psychology, outpatient research.

The primary goal of mental health services is to provide interventions that result in a reduction of problematic symptomatology [1]; therefore, evaluation of those interventions is important for both the client as well as the stakeholders of the organization providing them. Health care payment reforms require tracking quality measures, and such measures directly influence the development, administration, and monitoring of mental health programs as well as specific treatment modalities [2,3]. Organizations are more likely to benefit when outcomes measures are relayed quantitatively [4]. In addition, clients are becoming more informed regarding the quality of care, and outcomes assessments can inform clients that programs are delivering the most efficacious therapies based on current evidence-based practice standards.

Developing outcomes assessments in behavioral health is challenging [5–7]. There are numerous potential outcome domains that can be assessed as well as different ways of measuring them. Futher, evaluating treatment can be expensive, with components including developing a tool, training staff to administer the tool, ensuring the necessary technical support to store and process the data, interpretation of the data, compiling reports, and communicating results to clients and providers [5]. Being mindful of these components and their associated costs, our organization considered whether a tool we currently use to assess the appropriate intensity of service needed for an individual could also be used as an outcome measure.

Therapeutic methods for children in our organization consist of a “system of care” approach designed by a treatment team that incorporates varied methods depending on the needs of the child. The primary goal is to prevent children with traumatic-based disorders from developing continuing disorders associated with their experiences, such as substance use and chronic health and mental health disorders. Our organization currently uses the CASII (Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument) to assess the appropriate level of intensity of service needed by the child. The CASII incorporates holistic information on the child, within the context of his/her family and social ecology, assessing across 6 dimensions: risk of harm (including trauma issues), functional status, co-occurring conditions, recovery environment, resiliency/response to services, and involvement in services.

In order to comply with the call to consider outcomes measurement and evidence based practice as an integral component of children’s mental health services, this study was performed. It examines the use of the CASII as an outcomes measure based on the rationale that a decreased level of care upon discharge would correlate with a positive outcome by proxy.

Methods

CASII Instrument

The CASII is a decision support tool to help the service provider determine the intensity of services that a child should have to adequately address their behavioral health needs. The CASII has a strong evidence base supporting its reliability and validity [8], and has gained wide usage in a range of health care settings over the past 13 years [9–11].

As mentioned, the CASII assesses the client across 6 key dimensions: risk of harm (including trauma issues), functional status, co-occurring conditions, recovery environment, resiliency/response to services, and involvement in services. Each dimension is scored along a 5-point rating scale, and a total or composite rating is calculated by adding the scores for each dimension. The composite rating corresponds with the level of service intensity needed. There are 7 levels of service intensity, ranging from Level 0 (corresponding with a composite rating of 9 or less) to Level 6 (corresponding with a composite rating of 28 or more) (Table 1).

Study Sample

The sample consisted of all clients (n = 8465) admitted to service from 2013 through 2016 to our facility. Our facility is an outpatient facility offering counseling, mental health assessment and treatment, early childhood trauma assessment, child crisis interventions and rehabilitation for domestic violence, child abuse and neglect, and substance abuse. All clients between the ages of 6 and 17 are assessed with the CASII on admission and then at 6-month intervals until discharge from the program. Being discharged from the program of care prompts the completion of the discharge CASII. If the client had been rated within the 30 days prior to discharge the most recent CASII is used as the discharge measure.

Data Analysis

Data for all admissions from 2013 and 2016 were extracted from the organization’s computer system into an Excel file. The data collected included gender, calendar year of admission to the program, age, and diagnosis group based on the discharge diagnosis given by the mental health team, and whether the client was a participant in the Youth in Transition (YIT) program (program for older clients that includes life skills training in addition to standard therapy). The CASII composite rating at baseline and discharge as well as ratings for each of the 6 dimensions assessed with the CASII were also collected.

We used SPSS (v25.01) software for statistical analysis. Analysis included paired (pre-post) t-tests that were applied to the entire cohort as well as within gender, age group, participation in the YIT program, and diagnosis groups. Diagnosis groups were included only if the frequency of cases within the group was large enough to meet the sample size requirements of central limit theorem (in general, n > 25), with 2 exceptions: schizophrenia spectrum was included because of the rarity of the diagnosis (n = 11) and neurodevelopmental disorders (also n = 11) was included because there was no violation of the equal variance assumption as well as interest to the investigators. In addition to the paired analysis, we used group t tests to determine if there were severity differences between groups at baseline. Lastly, we assessed change from admission to discharge for each of the 6 dimensions that make up the composite rating.

We designated the 7 levels of care defined by the CASII as continuous in nature, and therefore computations of means and standard deviations (SD) are appropriate for assessment. The interpretation of the CASII composite rating and the level of care as a continuous variable has also been reported in the literature [11,12].

The research and analysis was viewed as exploratory in nature and a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. There was no correction for multiple comparisons applied to the data in order to not mask any observed differences in the data. All analyses were 2-tailed. If any individual had a missing value for either an admission or discharge CASII assessment they were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Results

There were 8465 clients admitted from 2013 and 2016. The sample was predominantly male (54.5%), and the majority fell into the older 12–17 year old cohort (54.0%). Admissions were evenly distributed across the 4 years that we studied, with the lowest percentage in 2013 at 23.4% and the highest in 2014 at 26.0%. Discharge diagnosis was available for the majority of the cohort. The top 5 most frequent diagnosis groups were adjustment disorders (n = 807, 18.3%), ADHD (n = 798, 18.1%), child neglect (n = 775, 17.6%), mood disorders (n = 602, 13.6%), and impulse disorders (n = 262, 5.9%). There were 232 (2.7%) clients that participated in the YIT program. Table 2

At admission, several groups had higher mean composite ratings. Males had higher ratings (in need of higher level of service intensity) than females (P < 0.001), 12–17 year olds had a significantly higher acuity level than 6–11 year olds (P < 0.001), and clients in the YIT program had a higher acuity level than those not in the YIT program (P = 0.001). Baseline acuity levels for primary discharge diagnosis for selected groups are shown in the Figure.

When analyzing the entire cohort for which data were available (n = 6944), the mean CASII composite rating dropped from 13.23 (± 4.35 SD) to 12.04 (± 3.84 SD), P < 0.001. Excluding youth that participated in YIT, the mean CASII score dropped from 13.21 (± 4.33) at admission to 13.17 (± 4.52) at discharge. Mean composite rating for clients participating in the YIT program dropped from 14.31 (± 5.12) at admission to 13.17 (± 4.52) at discharge (P = 0.022). For diagnosis groups, statistically significant reduction in mean CASII composite rating was observed for all groups except neurodevelopmentall disorders (P = 0.166). The results for all groups and diagnosis cohorts can be found in Table 3.

As noted, the CASII assesses the client across 6 dimensions, each of which is scored along a 5-point rating scale, and the composite rating is calculated by adding the scores for each dimension. Table 4 shows the change in mean dimension scores from baseline to discharge for these dimensions. Mean scores improved significantly (all P < 0.001).

Discussion

Organizations that provide mental health services are burdened with a complicated milieu of providing the best care possible in a complicated system of assessment, reimbursement, admissions/discharges, and a variety of other tasks. Using multiple measures complicates assessment and increases costs because of training staff, developing and interpreting the tool results, data storage and more comprehensive analysis and communication of results back to stakeholders and staff. Complicated measures are often times not understood by the staff and those responsible for care, nor are measures understood by the clients and their families. While a wide array of psychometric assessment tools exist, most are applicable to only specific diagnosis groups or illnesses.

Our study showed that the CASII may be used to monitor progress and reassess the level of service intensity needed, and therefore may be useful as an outcome measure. There are benefits in having a single score as an outcome measure. A single score for each client is quick and easy to understand by board members, staff of the organization as well as clients outside of the organization such as funders, client, press etc. Also the use of a single score is cost effective as costs for interpretation, training and communication within and outside of the organization are reduced.

A number of limitations must be mentioned. Although a change in score represents a change in client condition, this change in condition can have a wide variety of explanations. Change can be related to the therapy received, to changes in the client’s environment, support services, and many other factors. Our research did not allow us to discern what aspects of care may have reduced level of service intensity needed at discharge. In addition, our study involved clients of low and moderate acuity. The study does not address if CASII would be sensitive to change in upper acuity ranges. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable in these settings.

Tolan and Dodge [10] called for the enhancement or an elevation in the assessment of psychology as a matter of public policy. An approach that involves all levels of scientific inquiry including economics, political science and other sciences is desperately needed. Assessment of the type presented in this article, even if instruments such as the CASII are not used, can help to shape that policy by providing unquestionably accurate assessment of a client’s condition which demonstrates the need for that support. Further research looking at specific attributes of therapy and the client’s condition and environment may be helpful in applying CASII composite ratings and dimension scores as outcome measures.

Corresponding author: Dr. Lorrie Henderson, Jewish Family and Children’s Service, 4747 North 7th St., Suite 100, Phoenix, AZ 850142.

Financial disclosures: None.

From the Jewish Family and Children’s Service, Phoenix, AZ (Dr. Henderson) and Consult-Stat, Macungie, PA (Ms. Wasser, Dr. Wasser).

Abstract

- Background: The reliability and validity of the Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument (CASII) as a tool to help determine needed level of care for children with behavioral health needs has previously been established.

- Objective: To determine the utility of the CASII as an outcome measure.

- Methods: A sample consisting of all clients (n = 8465) admitted to service at an outpatient beha

vioral health facility from 2013 through 2016 were studied. CASII was administered at admission and discharge and ratings were compared with paired t-tests within demographic and diagnosis groups. - Results: Mean CASII composite ratings decreased between admission and discharge in the entire cohort as well as within gender, age group, and multiple diagnosis groups tested.

- Conclusion: CASII was useful as an outcome measure in our relatively low to moderate acuity population.

Keywords: outcomes, evidence based practice, child psychology, outpatient research.

The primary goal of mental health services is to provide interventions that result in a reduction of problematic symptomatology [1]; therefore, evaluation of those interventions is important for both the client as well as the stakeholders of the organization providing them. Health care payment reforms require tracking quality measures, and such measures directly influence the development, administration, and monitoring of mental health programs as well as specific treatment modalities [2,3]. Organizations are more likely to benefit when outcomes measures are relayed quantitatively [4]. In addition, clients are becoming more informed regarding the quality of care, and outcomes assessments can inform clients that programs are delivering the most efficacious therapies based on current evidence-based practice standards.

Developing outcomes assessments in behavioral health is challenging [5–7]. There are numerous potential outcome domains that can be assessed as well as different ways of measuring them. Futher, evaluating treatment can be expensive, with components including developing a tool, training staff to administer the tool, ensuring the necessary technical support to store and process the data, interpretation of the data, compiling reports, and communicating results to clients and providers [5]. Being mindful of these components and their associated costs, our organization considered whether a tool we currently use to assess the appropriate intensity of service needed for an individual could also be used as an outcome measure.

Therapeutic methods for children in our organization consist of a “system of care” approach designed by a treatment team that incorporates varied methods depending on the needs of the child. The primary goal is to prevent children with traumatic-based disorders from developing continuing disorders associated with their experiences, such as substance use and chronic health and mental health disorders. Our organization currently uses the CASII (Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument) to assess the appropriate level of intensity of service needed by the child. The CASII incorporates holistic information on the child, within the context of his/her family and social ecology, assessing across 6 dimensions: risk of harm (including trauma issues), functional status, co-occurring conditions, recovery environment, resiliency/response to services, and involvement in services.

In order to comply with the call to consider outcomes measurement and evidence based practice as an integral component of children’s mental health services, this study was performed. It examines the use of the CASII as an outcomes measure based on the rationale that a decreased level of care upon discharge would correlate with a positive outcome by proxy.

Methods

CASII Instrument

The CASII is a decision support tool to help the service provider determine the intensity of services that a child should have to adequately address their behavioral health needs. The CASII has a strong evidence base supporting its reliability and validity [8], and has gained wide usage in a range of health care settings over the past 13 years [9–11].

As mentioned, the CASII assesses the client across 6 key dimensions: risk of harm (including trauma issues), functional status, co-occurring conditions, recovery environment, resiliency/response to services, and involvement in services. Each dimension is scored along a 5-point rating scale, and a total or composite rating is calculated by adding the scores for each dimension. The composite rating corresponds with the level of service intensity needed. There are 7 levels of service intensity, ranging from Level 0 (corresponding with a composite rating of 9 or less) to Level 6 (corresponding with a composite rating of 28 or more) (Table 1).

Study Sample

The sample consisted of all clients (n = 8465) admitted to service from 2013 through 2016 to our facility. Our facility is an outpatient facility offering counseling, mental health assessment and treatment, early childhood trauma assessment, child crisis interventions and rehabilitation for domestic violence, child abuse and neglect, and substance abuse. All clients between the ages of 6 and 17 are assessed with the CASII on admission and then at 6-month intervals until discharge from the program. Being discharged from the program of care prompts the completion of the discharge CASII. If the client had been rated within the 30 days prior to discharge the most recent CASII is used as the discharge measure.

Data Analysis

Data for all admissions from 2013 and 2016 were extracted from the organization’s computer system into an Excel file. The data collected included gender, calendar year of admission to the program, age, and diagnosis group based on the discharge diagnosis given by the mental health team, and whether the client was a participant in the Youth in Transition (YIT) program (program for older clients that includes life skills training in addition to standard therapy). The CASII composite rating at baseline and discharge as well as ratings for each of the 6 dimensions assessed with the CASII were also collected.

We used SPSS (v25.01) software for statistical analysis. Analysis included paired (pre-post) t-tests that were applied to the entire cohort as well as within gender, age group, participation in the YIT program, and diagnosis groups. Diagnosis groups were included only if the frequency of cases within the group was large enough to meet the sample size requirements of central limit theorem (in general, n > 25), with 2 exceptions: schizophrenia spectrum was included because of the rarity of the diagnosis (n = 11) and neurodevelopmental disorders (also n = 11) was included because there was no violation of the equal variance assumption as well as interest to the investigators. In addition to the paired analysis, we used group t tests to determine if there were severity differences between groups at baseline. Lastly, we assessed change from admission to discharge for each of the 6 dimensions that make up the composite rating.

We designated the 7 levels of care defined by the CASII as continuous in nature, and therefore computations of means and standard deviations (SD) are appropriate for assessment. The interpretation of the CASII composite rating and the level of care as a continuous variable has also been reported in the literature [11,12].

The research and analysis was viewed as exploratory in nature and a P value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. There was no correction for multiple comparisons applied to the data in order to not mask any observed differences in the data. All analyses were 2-tailed. If any individual had a missing value for either an admission or discharge CASII assessment they were excluded from the statistical analysis.

Results

There were 8465 clients admitted from 2013 and 2016. The sample was predominantly male (54.5%), and the majority fell into the older 12–17 year old cohort (54.0%). Admissions were evenly distributed across the 4 years that we studied, with the lowest percentage in 2013 at 23.4% and the highest in 2014 at 26.0%. Discharge diagnosis was available for the majority of the cohort. The top 5 most frequent diagnosis groups were adjustment disorders (n = 807, 18.3%), ADHD (n = 798, 18.1%), child neglect (n = 775, 17.6%), mood disorders (n = 602, 13.6%), and impulse disorders (n = 262, 5.9%). There were 232 (2.7%) clients that participated in the YIT program. Table 2

At admission, several groups had higher mean composite ratings. Males had higher ratings (in need of higher level of service intensity) than females (P < 0.001), 12–17 year olds had a significantly higher acuity level than 6–11 year olds (P < 0.001), and clients in the YIT program had a higher acuity level than those not in the YIT program (P = 0.001). Baseline acuity levels for primary discharge diagnosis for selected groups are shown in the Figure.

When analyzing the entire cohort for which data were available (n = 6944), the mean CASII composite rating dropped from 13.23 (± 4.35 SD) to 12.04 (± 3.84 SD), P < 0.001. Excluding youth that participated in YIT, the mean CASII score dropped from 13.21 (± 4.33) at admission to 13.17 (± 4.52) at discharge. Mean composite rating for clients participating in the YIT program dropped from 14.31 (± 5.12) at admission to 13.17 (± 4.52) at discharge (P = 0.022). For diagnosis groups, statistically significant reduction in mean CASII composite rating was observed for all groups except neurodevelopmentall disorders (P = 0.166). The results for all groups and diagnosis cohorts can be found in Table 3.

As noted, the CASII assesses the client across 6 dimensions, each of which is scored along a 5-point rating scale, and the composite rating is calculated by adding the scores for each dimension. Table 4 shows the change in mean dimension scores from baseline to discharge for these dimensions. Mean scores improved significantly (all P < 0.001).

Discussion

Organizations that provide mental health services are burdened with a complicated milieu of providing the best care possible in a complicated system of assessment, reimbursement, admissions/discharges, and a variety of other tasks. Using multiple measures complicates assessment and increases costs because of training staff, developing and interpreting the tool results, data storage and more comprehensive analysis and communication of results back to stakeholders and staff. Complicated measures are often times not understood by the staff and those responsible for care, nor are measures understood by the clients and their families. While a wide array of psychometric assessment tools exist, most are applicable to only specific diagnosis groups or illnesses.

Our study showed that the CASII may be used to monitor progress and reassess the level of service intensity needed, and therefore may be useful as an outcome measure. There are benefits in having a single score as an outcome measure. A single score for each client is quick and easy to understand by board members, staff of the organization as well as clients outside of the organization such as funders, client, press etc. Also the use of a single score is cost effective as costs for interpretation, training and communication within and outside of the organization are reduced.

A number of limitations must be mentioned. Although a change in score represents a change in client condition, this change in condition can have a wide variety of explanations. Change can be related to the therapy received, to changes in the client’s environment, support services, and many other factors. Our research did not allow us to discern what aspects of care may have reduced level of service intensity needed at discharge. In addition, our study involved clients of low and moderate acuity. The study does not address if CASII would be sensitive to change in upper acuity ranges. Therefore, our findings may not be generalizable in these settings.

Tolan and Dodge [10] called for the enhancement or an elevation in the assessment of psychology as a matter of public policy. An approach that involves all levels of scientific inquiry including economics, political science and other sciences is desperately needed. Assessment of the type presented in this article, even if instruments such as the CASII are not used, can help to shape that policy by providing unquestionably accurate assessment of a client’s condition which demonstrates the need for that support. Further research looking at specific attributes of therapy and the client’s condition and environment may be helpful in applying CASII composite ratings and dimension scores as outcome measures.

Corresponding author: Dr. Lorrie Henderson, Jewish Family and Children’s Service, 4747 North 7th St., Suite 100, Phoenix, AZ 850142.

Financial disclosures: None.

1. Thornicroft G, Slade M. New trends in assessing the outcomes of mental health interventions. World Psychiatry 2014;13:118.

2. England MJ, Butler AS, Gonzalez ML, editors. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Committee on Developing Evidence-Based Standards for Psychosocial Interventions for Mental Disorders; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2015 Sep 18.

3. Schurer Coldiron J, Hensley SW, Bruns EJ, Paragoris R. Putting the outcomes‐based principle into action part one: a guide for wraparound care coordinators; The National Technical Assistance Network for Children’s Behavioral Health. 2016. Available at: https://nwi.pdx.edu/pdf/Putting-the-Outcomes-Based-Principle-Into-Action.pdf.

4. Lachar D, Randle S, Harper R, et al. The brief psychiatric rating scale for children (BPRS-C): Validity and reliability of an anchored version. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry 2001;40:333–40.

5. Sperry L, Brill PL, Howard KI, Grissom GR. Treatment outcomes in psychotherapy and psychiatric interventions. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1996.

6. Burlingame GM, Lambert MJ, Reisinger CW, et al. Pragmatics of tracking mental health outcomes in a managed care setting. J Ment Health Adm 1995;22:226–36.

7. Henderson L, McIlhaney K, Wasser T. Measuring outcomes of multiple diagnosis groups in residential treatment using the brief psychiatric rating scale for children (BPRS-C). Children Youth Serv Rev 2008:24:243–59.

8. Fallon T Jr, Pumariega A, Sowers W, et al. A level of care instrument for children’s systems of care: Construction, reliability and validity. J Child Fam Studies 2006:15:143–155.

9. Minnesota Department of Human Services announcement. DHS updates requirement for standardized outcome measures for children’s mental health. #17-53-01. 27 Feb 2017.

10. Tolan P, Dodge K. Children’s mental health as a primary care and concern: a system for comprehensive support and service. Am Psychol 2005;60:601–14.

11. Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument (CASII) Overview for Anthem Connecticut Members. Accessed at www11.anthem.com/provider/ct/f3/s9/t1/pw_e205607.pdf?refer=ahpprovider.

12. Chenven M, Dominguez E, Grimes K, et al. CASII: Child and adolescent Service Intensity Instrument Background information and Initial Data Analysis. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Work Group June 2001.

1. Thornicroft G, Slade M. New trends in assessing the outcomes of mental health interventions. World Psychiatry 2014;13:118.

2. England MJ, Butler AS, Gonzalez ML, editors. Psychosocial interventions for mental and substance use disorders: a framework for establishing evidence-based standards. Committee on Developing Evidence-Based Standards for Psychosocial Interventions for Mental Disorders; Board on Health Sciences Policy; Institute of Medicine. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2015 Sep 18.

3. Schurer Coldiron J, Hensley SW, Bruns EJ, Paragoris R. Putting the outcomes‐based principle into action part one: a guide for wraparound care coordinators; The National Technical Assistance Network for Children’s Behavioral Health. 2016. Available at: https://nwi.pdx.edu/pdf/Putting-the-Outcomes-Based-Principle-Into-Action.pdf.

4. Lachar D, Randle S, Harper R, et al. The brief psychiatric rating scale for children (BPRS-C): Validity and reliability of an anchored version. J Am Acad Child Adol Psychiatry 2001;40:333–40.

5. Sperry L, Brill PL, Howard KI, Grissom GR. Treatment outcomes in psychotherapy and psychiatric interventions. Philadelphia: Brunner/Mazel; 1996.

6. Burlingame GM, Lambert MJ, Reisinger CW, et al. Pragmatics of tracking mental health outcomes in a managed care setting. J Ment Health Adm 1995;22:226–36.

7. Henderson L, McIlhaney K, Wasser T. Measuring outcomes of multiple diagnosis groups in residential treatment using the brief psychiatric rating scale for children (BPRS-C). Children Youth Serv Rev 2008:24:243–59.

8. Fallon T Jr, Pumariega A, Sowers W, et al. A level of care instrument for children’s systems of care: Construction, reliability and validity. J Child Fam Studies 2006:15:143–155.

9. Minnesota Department of Human Services announcement. DHS updates requirement for standardized outcome measures for children’s mental health. #17-53-01. 27 Feb 2017.

10. Tolan P, Dodge K. Children’s mental health as a primary care and concern: a system for comprehensive support and service. Am Psychol 2005;60:601–14.

11. Child and Adolescent Service Intensity Instrument (CASII) Overview for Anthem Connecticut Members. Accessed at www11.anthem.com/provider/ct/f3/s9/t1/pw_e205607.pdf?refer=ahpprovider.

12. Chenven M, Dominguez E, Grimes K, et al. CASII: Child and adolescent Service Intensity Instrument Background information and Initial Data Analysis. American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Work Group June 2001.