User login

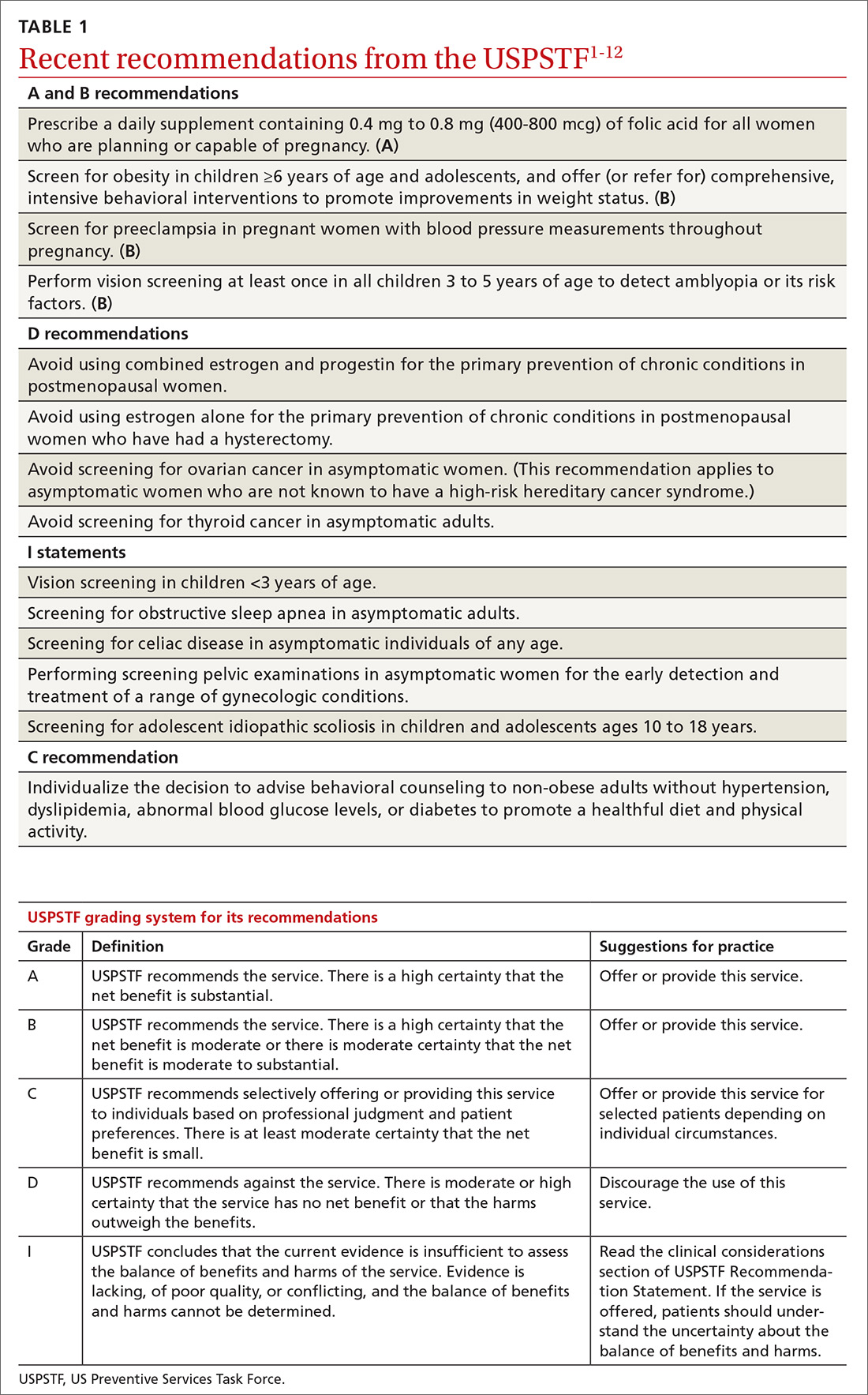

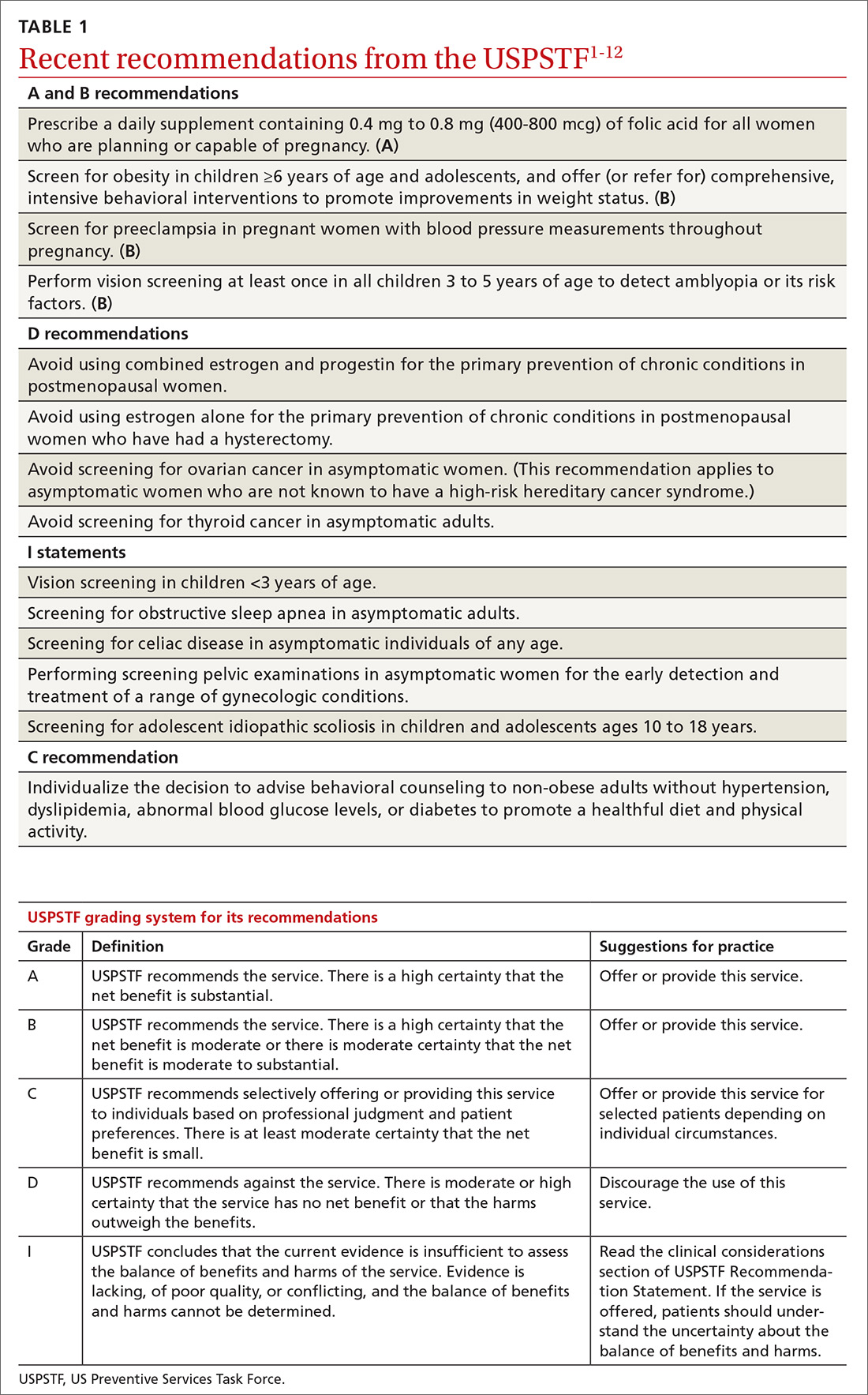

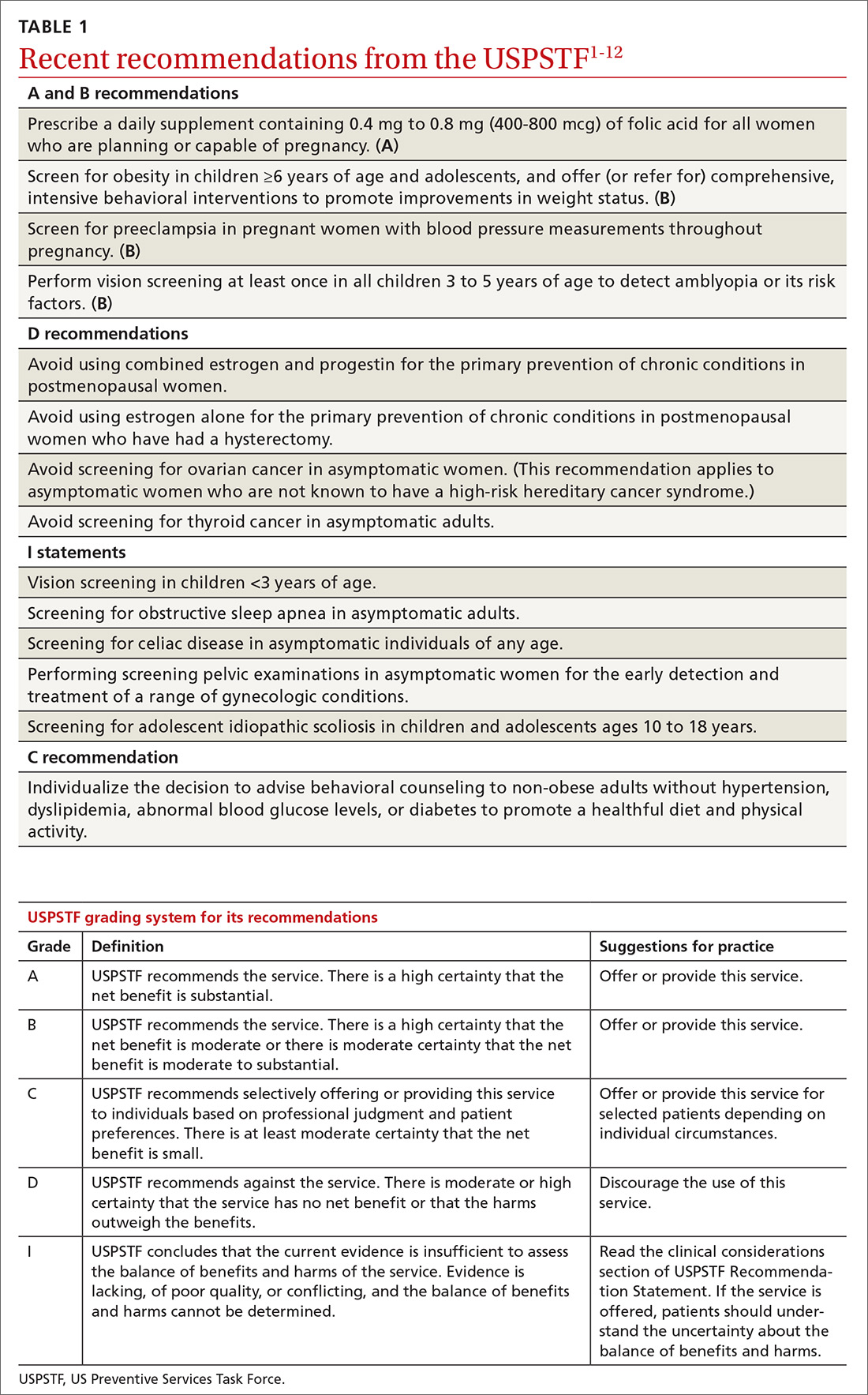

Over the past year the US Preventive Services Task Force made 14 recommendations on 12 conditions (TABLE 11-12). One of these pronouncements was the unusual reversal of a previous “D” recommendation against screening for scoliosis in adolescents, changing it to an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).

Affirmative recommendations

Four interventions were given an “A” or “B” recommendation this past year. Both grades signify a recommendation to perform the service, with “A” reflecting a higher level of certainty or a higher level of net benefit than “B.”

Recommend folic acid to prevent neural tube defects (A)

The evidence is very strong that folic acid intake prevents neural tube defects. In 2009 the Task Force recommended folic acid supplementation for women of childbearing age. In 2017 this recommendation was updated and slightly reworded to advise that all women who are planning a pregnancy or capable of becoming pregnant take a daily supplement containing 0.4 mg to 0.8 mg (400-800 mcg) of folic acid.

In the United States many grain products have been fortified with folic acid since 1996. This step has reduced the prevalence of neural tube defects from 10.7 cases per 10,000 live births to 7 cases per 10,000 live births in 2011.1 However, in spite of food fortification, most women in the United States do not consume the recommended daily amount of 0.4 mg (400 mcg) of folic acid. This supplementation is most important from one month before conception through the first 3 months of pregnancy.

Screen for obesity in children and adolescents (B)

Nearly 17% of children and adolescents ages 2 to 19 years in the United States are obese, and almost 32% are overweight or obese.2 Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile, based on year-2000 growth charts published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight is defined as a BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles.

Obesity in children and adolescents is associated with many physical problems, including obstructive sleep apnea, orthopedic problems, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, as well as psychological harms from being teased and bullied. Obesity that continues into adulthood is associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and orthopedic problems.

The Task Force found that intensive behavioral interventions for obesity in children ≥6 years of age and in adolescents can lead to moderate improvements in weight status for up to 12 months. Intensive behavioral interventions need to include at least 26 contact hours over 2 to 12 months. The recommendation statement includes a more detailed description of the types of programs that have evidence to support them.2

The Task Force did not recommend the use of either metformin or orlistat because of inadequate evidence on the harmful effects of metformin and because of sound evidence that orlistat causes moderate harms, such as abdominal pain, cramping, incontinence, and flatus.

Screen for preeclampsia (B), but dipstick testing is unreliable

Preeclampsia occurs in a little more than 3% of pregnancies in the United States.13 For the mother, this condition can lead to stroke, eclampsia, organ failure, and death; for the fetus, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm birth, low birth weight, and still birth. Preeclampsia is a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide. Adverse health outcomes can be prevented by early detection of preeclampsia and by managing it appropriately.3

In 1996 the Task Force recommended screening for preeclampsia during pregnancy, and it reaffirmed that recommendation last year. The Task Force recommends taking blood pressure measurements at every prenatal visit, but does not recommend testing for urine protein with a dipstick because of the technique’s low accuracy.

Since 2014 the Task Force has also recommended using low-dose aspirin after Week 12 of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia in women who are at high risk.14

Conduct vision screening in all children ages 3 to 5 years (B)

One of the more nuanced recommendations involves vision screening in children. The Task Force recently reaffirmed its 2011 recommendation to perform vision screening at least once in all children ages 3 to 5 years to detect amblyopia or its risk factors. But it found insufficient evidence to test children <3 years of age.

Amblyopia is a “functional reduction in visual acuity characterized by abnormal processing of visual images; [it is] established by the brain during a critical period of vision development.”4 Risk factors associated with the development of amblyopia include strabismus (ocular misalignment); vision loss caused by cataracts; refractive errors such as near and far sightedness, astigmatism (“blurred vision at any distance due to abnormal curvature of the cornea or lens”); and anisometropia (“asymmetric refractive error between the … eyes that causes image suppression in the eye with the larger error”). 4

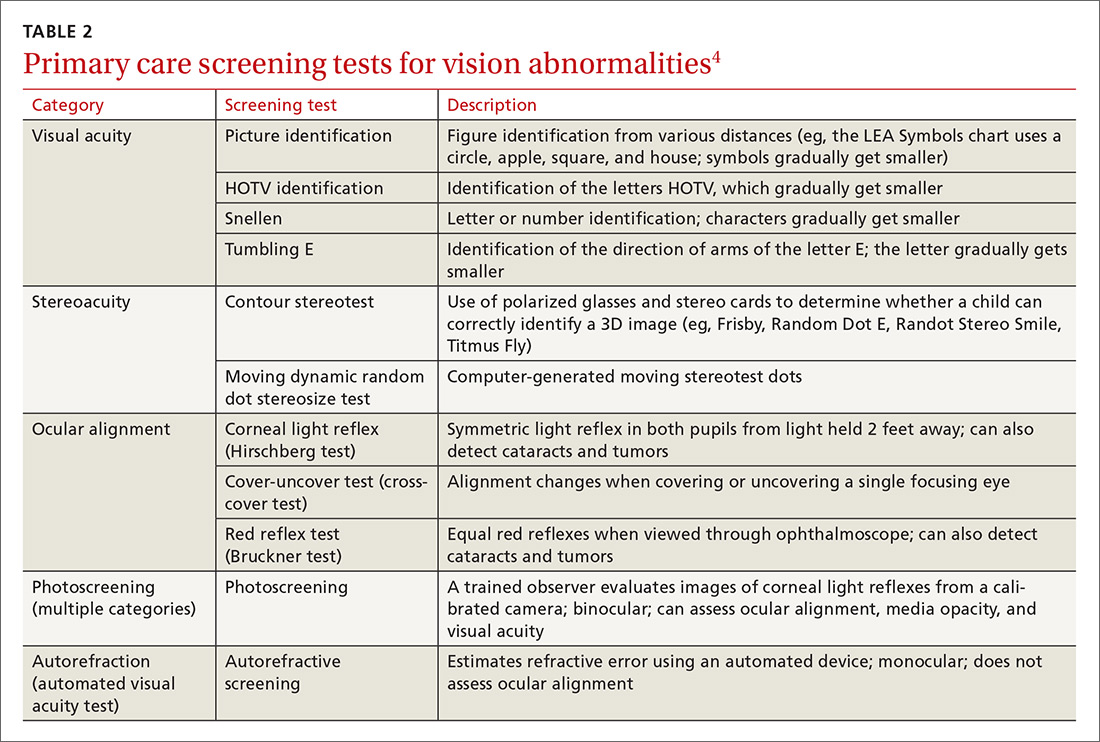

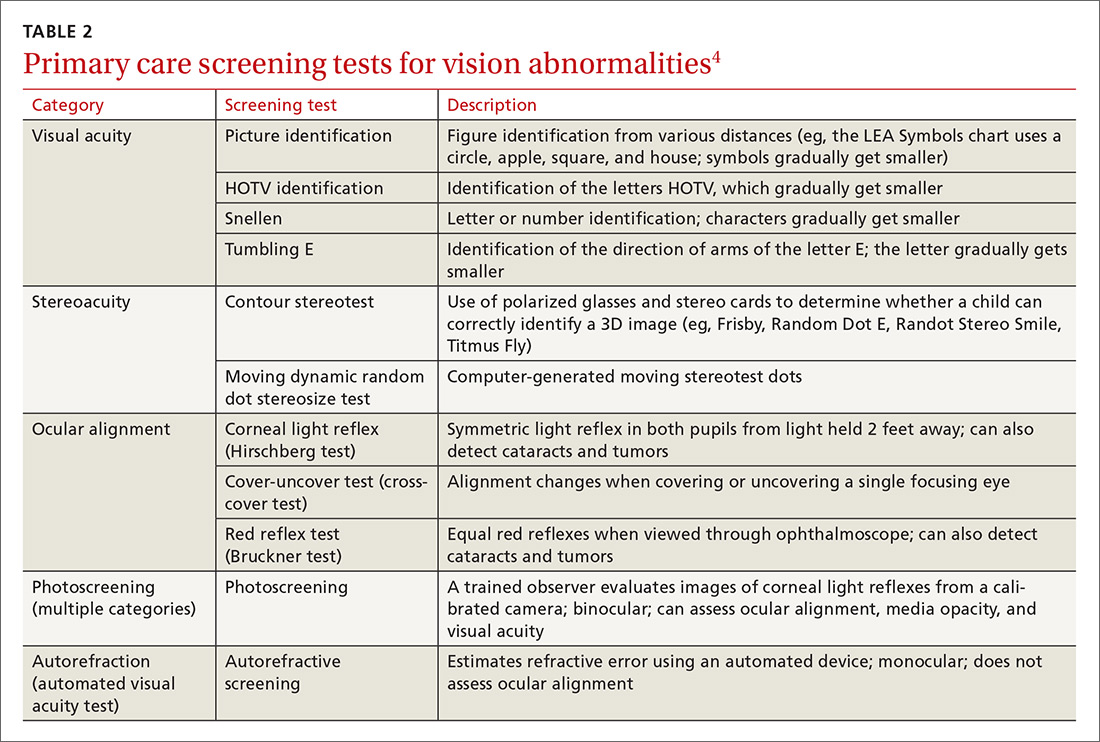

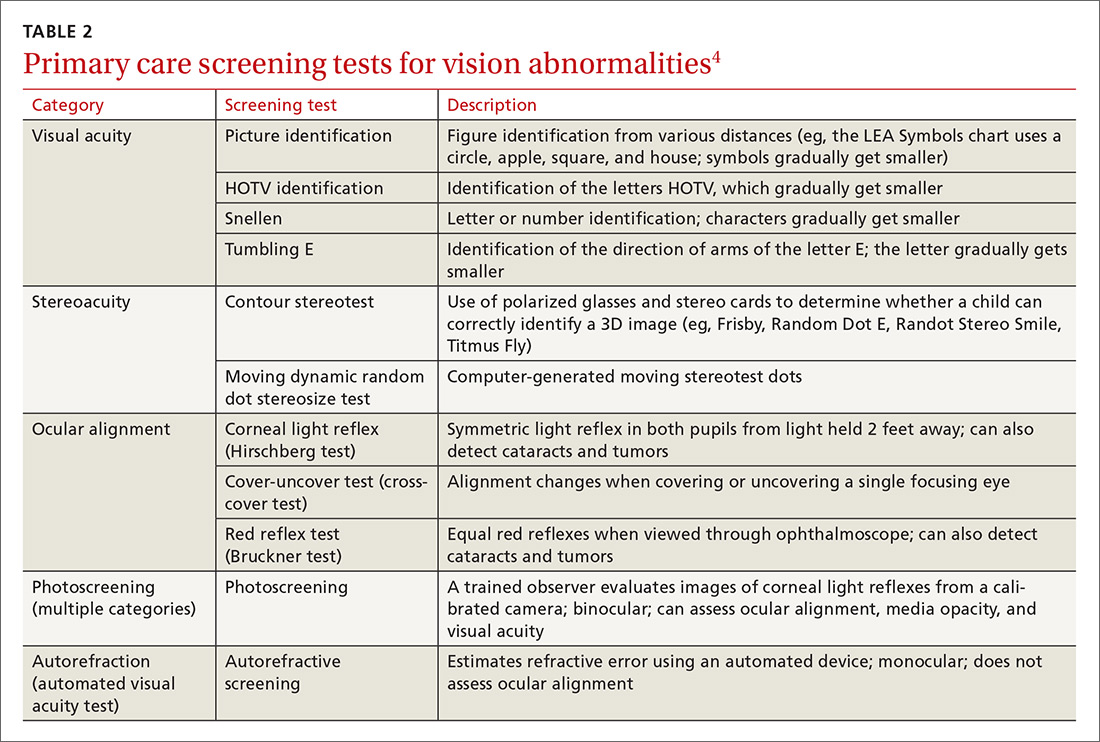

Physical exam- and machine-based screening tests are available in the primary care setting (TABLE 2).4

At first glance it appears that the Task Force recommends screening only for amblyopia, but the addition of “risk factors” implies a more comprehensive vision evaluation that would include visual acuity. This interpretation more closely aligns the Task Force recommendation with that of a joint report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Certified Orthoptists, and American Academy of Ophthalmology, which recommends testing for a variety of vision problems in children.15 Nevertheless, the Task Force maintains that the evidence of benefit in testing more extensively before age 3 is insufficient, while the other organizations recommend starting testing at age 6 months.

Negative “D” recommendations

Equally as important as affirmative recommendations for effective interventions are the “D” recommendations advising against interventions that are ineffective or cause more harm than benefits. This past year, the Task Force recommended against 4 interventions. Two pertain to the use of estrogen or combined estrogen and progestin for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women.5 This topic has been discussed in a recent JFP audiocast. Also receiving “D” recommendations were screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women,6 discussed in another JFP audiocast, and screening for thyroid cancer in asymptomatic adults.7

The “D” recommendation for thyroid cancer screening was based on the low incidence of thyroid cancer, the evidence showing no change in mortality after the introduction of population-based screening, and the likelihood of overdiagnosis and overtreatment that would result from screening. The screening tests considered by the Task Force included neck palpation and ultrasound.7

Insufficient evidence

In addition to the previously mentioned “I” statement on vision screening for children <3 years of age,4 4 other interventions lacked sufficient evidence that the Task Force could use in determining relative levels of harms and benefits. These interventions were screening for obstructive sleep apnea in asymptomatic adults,8 screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic patients of all ages,9 screening with a pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,10 and screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents ages 10 to 18 years.11

The lack of evidence regarding the value of a routine pelvic exam for asymptomatic women is surprising given how often this procedure is performed. The Task Force defined a pelvic exam as an “assessment of the external genitalia, internal speculum examination, bimanual palpation, and rectovaginal examination.”10 The Task Force found very little evidence on the accuracy and effectiveness of this exam for a range of gynecologic conditions other than cervical cancer, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, for which screening is recommended.10

The “I” statement on screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents is an unusual revision of a “D” recommendation from 2004. At that time, the Task Force found that treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis leads to health benefits in only a small proportion of individuals and that there are harms of treatment such as unnecessary bracing and referral to specialty care. For the most recent evidence report, the Task Force used a new methodology to assess treatment harms and concluded that the evidence is now inadequate. That finding, along with new evidence that “suggests that brace treatment can interrupt or slow scoliosis progression” led the Task Force to move away from a “D” recommendation.11

The enigmatic “C” recommendation

Perhaps the most difficult recommendation category to understand and implement is the “C” recommendation. With a “C” intervention, there is moderate certainty that the net benefit of universal implementation would be very small; but there are some individuals who might benefit from it, and physicians should offer it selectively.

The Task Force made one “C” recommendation over the past year: for adults who are not obese and who do not have other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks, the net gain in referring them to behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity is small. However, the harms from such referrals are also small. Counseling interventions can result in healthier habits and in small improvements in intermediate outcomes, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight. The effect on overall CVD mortality, though, has been minimal.12 The Task Force concluded that “[those] who are interested and ready to make behavioral changes may be most likely to benefit from behavioral counseling.”

1. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

2. USPSTF. Obesity in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/obesity-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

3. USPSTF. Preeclampsia: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/preeclampsia-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

4. USPSTF. Vision in children ages 6 months to 5 years: Screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/vision-in-children-ages-6-months-to-5-years-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

5. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

6. USPSTF. Ovarian cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/ovarian-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

7. USPSTF. Thyroid cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/thyroid-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

8. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

9. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 24, 2018.

10. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2018.

11. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

12. USPSTF. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/healthful-diet-and-physical-activity-for-cardiovascular-disease-prevention-in-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling. Accessed March 22, 2018.

13. Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6564.

14. USPSTF. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

15. Donahue SP, Baker CN; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137.2015-3597.

Over the past year the US Preventive Services Task Force made 14 recommendations on 12 conditions (TABLE 11-12). One of these pronouncements was the unusual reversal of a previous “D” recommendation against screening for scoliosis in adolescents, changing it to an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).

Affirmative recommendations

Four interventions were given an “A” or “B” recommendation this past year. Both grades signify a recommendation to perform the service, with “A” reflecting a higher level of certainty or a higher level of net benefit than “B.”

Recommend folic acid to prevent neural tube defects (A)

The evidence is very strong that folic acid intake prevents neural tube defects. In 2009 the Task Force recommended folic acid supplementation for women of childbearing age. In 2017 this recommendation was updated and slightly reworded to advise that all women who are planning a pregnancy or capable of becoming pregnant take a daily supplement containing 0.4 mg to 0.8 mg (400-800 mcg) of folic acid.

In the United States many grain products have been fortified with folic acid since 1996. This step has reduced the prevalence of neural tube defects from 10.7 cases per 10,000 live births to 7 cases per 10,000 live births in 2011.1 However, in spite of food fortification, most women in the United States do not consume the recommended daily amount of 0.4 mg (400 mcg) of folic acid. This supplementation is most important from one month before conception through the first 3 months of pregnancy.

Screen for obesity in children and adolescents (B)

Nearly 17% of children and adolescents ages 2 to 19 years in the United States are obese, and almost 32% are overweight or obese.2 Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile, based on year-2000 growth charts published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight is defined as a BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles.

Obesity in children and adolescents is associated with many physical problems, including obstructive sleep apnea, orthopedic problems, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, as well as psychological harms from being teased and bullied. Obesity that continues into adulthood is associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and orthopedic problems.

The Task Force found that intensive behavioral interventions for obesity in children ≥6 years of age and in adolescents can lead to moderate improvements in weight status for up to 12 months. Intensive behavioral interventions need to include at least 26 contact hours over 2 to 12 months. The recommendation statement includes a more detailed description of the types of programs that have evidence to support them.2

The Task Force did not recommend the use of either metformin or orlistat because of inadequate evidence on the harmful effects of metformin and because of sound evidence that orlistat causes moderate harms, such as abdominal pain, cramping, incontinence, and flatus.

Screen for preeclampsia (B), but dipstick testing is unreliable

Preeclampsia occurs in a little more than 3% of pregnancies in the United States.13 For the mother, this condition can lead to stroke, eclampsia, organ failure, and death; for the fetus, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm birth, low birth weight, and still birth. Preeclampsia is a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide. Adverse health outcomes can be prevented by early detection of preeclampsia and by managing it appropriately.3

In 1996 the Task Force recommended screening for preeclampsia during pregnancy, and it reaffirmed that recommendation last year. The Task Force recommends taking blood pressure measurements at every prenatal visit, but does not recommend testing for urine protein with a dipstick because of the technique’s low accuracy.

Since 2014 the Task Force has also recommended using low-dose aspirin after Week 12 of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia in women who are at high risk.14

Conduct vision screening in all children ages 3 to 5 years (B)

One of the more nuanced recommendations involves vision screening in children. The Task Force recently reaffirmed its 2011 recommendation to perform vision screening at least once in all children ages 3 to 5 years to detect amblyopia or its risk factors. But it found insufficient evidence to test children <3 years of age.

Amblyopia is a “functional reduction in visual acuity characterized by abnormal processing of visual images; [it is] established by the brain during a critical period of vision development.”4 Risk factors associated with the development of amblyopia include strabismus (ocular misalignment); vision loss caused by cataracts; refractive errors such as near and far sightedness, astigmatism (“blurred vision at any distance due to abnormal curvature of the cornea or lens”); and anisometropia (“asymmetric refractive error between the … eyes that causes image suppression in the eye with the larger error”). 4

Physical exam- and machine-based screening tests are available in the primary care setting (TABLE 2).4

At first glance it appears that the Task Force recommends screening only for amblyopia, but the addition of “risk factors” implies a more comprehensive vision evaluation that would include visual acuity. This interpretation more closely aligns the Task Force recommendation with that of a joint report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Certified Orthoptists, and American Academy of Ophthalmology, which recommends testing for a variety of vision problems in children.15 Nevertheless, the Task Force maintains that the evidence of benefit in testing more extensively before age 3 is insufficient, while the other organizations recommend starting testing at age 6 months.

Negative “D” recommendations

Equally as important as affirmative recommendations for effective interventions are the “D” recommendations advising against interventions that are ineffective or cause more harm than benefits. This past year, the Task Force recommended against 4 interventions. Two pertain to the use of estrogen or combined estrogen and progestin for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women.5 This topic has been discussed in a recent JFP audiocast. Also receiving “D” recommendations were screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women,6 discussed in another JFP audiocast, and screening for thyroid cancer in asymptomatic adults.7

The “D” recommendation for thyroid cancer screening was based on the low incidence of thyroid cancer, the evidence showing no change in mortality after the introduction of population-based screening, and the likelihood of overdiagnosis and overtreatment that would result from screening. The screening tests considered by the Task Force included neck palpation and ultrasound.7

Insufficient evidence

In addition to the previously mentioned “I” statement on vision screening for children <3 years of age,4 4 other interventions lacked sufficient evidence that the Task Force could use in determining relative levels of harms and benefits. These interventions were screening for obstructive sleep apnea in asymptomatic adults,8 screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic patients of all ages,9 screening with a pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,10 and screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents ages 10 to 18 years.11

The lack of evidence regarding the value of a routine pelvic exam for asymptomatic women is surprising given how often this procedure is performed. The Task Force defined a pelvic exam as an “assessment of the external genitalia, internal speculum examination, bimanual palpation, and rectovaginal examination.”10 The Task Force found very little evidence on the accuracy and effectiveness of this exam for a range of gynecologic conditions other than cervical cancer, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, for which screening is recommended.10

The “I” statement on screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents is an unusual revision of a “D” recommendation from 2004. At that time, the Task Force found that treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis leads to health benefits in only a small proportion of individuals and that there are harms of treatment such as unnecessary bracing and referral to specialty care. For the most recent evidence report, the Task Force used a new methodology to assess treatment harms and concluded that the evidence is now inadequate. That finding, along with new evidence that “suggests that brace treatment can interrupt or slow scoliosis progression” led the Task Force to move away from a “D” recommendation.11

The enigmatic “C” recommendation

Perhaps the most difficult recommendation category to understand and implement is the “C” recommendation. With a “C” intervention, there is moderate certainty that the net benefit of universal implementation would be very small; but there are some individuals who might benefit from it, and physicians should offer it selectively.

The Task Force made one “C” recommendation over the past year: for adults who are not obese and who do not have other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks, the net gain in referring them to behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity is small. However, the harms from such referrals are also small. Counseling interventions can result in healthier habits and in small improvements in intermediate outcomes, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight. The effect on overall CVD mortality, though, has been minimal.12 The Task Force concluded that “[those] who are interested and ready to make behavioral changes may be most likely to benefit from behavioral counseling.”

Over the past year the US Preventive Services Task Force made 14 recommendations on 12 conditions (TABLE 11-12). One of these pronouncements was the unusual reversal of a previous “D” recommendation against screening for scoliosis in adolescents, changing it to an “I” statement (insufficient evidence).

Affirmative recommendations

Four interventions were given an “A” or “B” recommendation this past year. Both grades signify a recommendation to perform the service, with “A” reflecting a higher level of certainty or a higher level of net benefit than “B.”

Recommend folic acid to prevent neural tube defects (A)

The evidence is very strong that folic acid intake prevents neural tube defects. In 2009 the Task Force recommended folic acid supplementation for women of childbearing age. In 2017 this recommendation was updated and slightly reworded to advise that all women who are planning a pregnancy or capable of becoming pregnant take a daily supplement containing 0.4 mg to 0.8 mg (400-800 mcg) of folic acid.

In the United States many grain products have been fortified with folic acid since 1996. This step has reduced the prevalence of neural tube defects from 10.7 cases per 10,000 live births to 7 cases per 10,000 live births in 2011.1 However, in spite of food fortification, most women in the United States do not consume the recommended daily amount of 0.4 mg (400 mcg) of folic acid. This supplementation is most important from one month before conception through the first 3 months of pregnancy.

Screen for obesity in children and adolescents (B)

Nearly 17% of children and adolescents ages 2 to 19 years in the United States are obese, and almost 32% are overweight or obese.2 Obesity is defined as a body mass index (BMI) ≥95th percentile, based on year-2000 growth charts published by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Overweight is defined as a BMI between the 85th and 94th percentiles.

Obesity in children and adolescents is associated with many physical problems, including obstructive sleep apnea, orthopedic problems, high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes, as well as psychological harms from being teased and bullied. Obesity that continues into adulthood is associated with diabetes, cardiovascular disease, and orthopedic problems.

The Task Force found that intensive behavioral interventions for obesity in children ≥6 years of age and in adolescents can lead to moderate improvements in weight status for up to 12 months. Intensive behavioral interventions need to include at least 26 contact hours over 2 to 12 months. The recommendation statement includes a more detailed description of the types of programs that have evidence to support them.2

The Task Force did not recommend the use of either metformin or orlistat because of inadequate evidence on the harmful effects of metformin and because of sound evidence that orlistat causes moderate harms, such as abdominal pain, cramping, incontinence, and flatus.

Screen for preeclampsia (B), but dipstick testing is unreliable

Preeclampsia occurs in a little more than 3% of pregnancies in the United States.13 For the mother, this condition can lead to stroke, eclampsia, organ failure, and death; for the fetus, intrauterine growth retardation, preterm birth, low birth weight, and still birth. Preeclampsia is a leading cause of maternal mortality worldwide. Adverse health outcomes can be prevented by early detection of preeclampsia and by managing it appropriately.3

In 1996 the Task Force recommended screening for preeclampsia during pregnancy, and it reaffirmed that recommendation last year. The Task Force recommends taking blood pressure measurements at every prenatal visit, but does not recommend testing for urine protein with a dipstick because of the technique’s low accuracy.

Since 2014 the Task Force has also recommended using low-dose aspirin after Week 12 of pregnancy to prevent preeclampsia in women who are at high risk.14

Conduct vision screening in all children ages 3 to 5 years (B)

One of the more nuanced recommendations involves vision screening in children. The Task Force recently reaffirmed its 2011 recommendation to perform vision screening at least once in all children ages 3 to 5 years to detect amblyopia or its risk factors. But it found insufficient evidence to test children <3 years of age.

Amblyopia is a “functional reduction in visual acuity characterized by abnormal processing of visual images; [it is] established by the brain during a critical period of vision development.”4 Risk factors associated with the development of amblyopia include strabismus (ocular misalignment); vision loss caused by cataracts; refractive errors such as near and far sightedness, astigmatism (“blurred vision at any distance due to abnormal curvature of the cornea or lens”); and anisometropia (“asymmetric refractive error between the … eyes that causes image suppression in the eye with the larger error”). 4

Physical exam- and machine-based screening tests are available in the primary care setting (TABLE 2).4

At first glance it appears that the Task Force recommends screening only for amblyopia, but the addition of “risk factors” implies a more comprehensive vision evaluation that would include visual acuity. This interpretation more closely aligns the Task Force recommendation with that of a joint report by the American Academy of Pediatrics, American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus, American Academy of Certified Orthoptists, and American Academy of Ophthalmology, which recommends testing for a variety of vision problems in children.15 Nevertheless, the Task Force maintains that the evidence of benefit in testing more extensively before age 3 is insufficient, while the other organizations recommend starting testing at age 6 months.

Negative “D” recommendations

Equally as important as affirmative recommendations for effective interventions are the “D” recommendations advising against interventions that are ineffective or cause more harm than benefits. This past year, the Task Force recommended against 4 interventions. Two pertain to the use of estrogen or combined estrogen and progestin for the primary prevention of chronic conditions in postmenopausal women.5 This topic has been discussed in a recent JFP audiocast. Also receiving “D” recommendations were screening for ovarian cancer in asymptomatic women,6 discussed in another JFP audiocast, and screening for thyroid cancer in asymptomatic adults.7

The “D” recommendation for thyroid cancer screening was based on the low incidence of thyroid cancer, the evidence showing no change in mortality after the introduction of population-based screening, and the likelihood of overdiagnosis and overtreatment that would result from screening. The screening tests considered by the Task Force included neck palpation and ultrasound.7

Insufficient evidence

In addition to the previously mentioned “I” statement on vision screening for children <3 years of age,4 4 other interventions lacked sufficient evidence that the Task Force could use in determining relative levels of harms and benefits. These interventions were screening for obstructive sleep apnea in asymptomatic adults,8 screening for celiac disease in asymptomatic patients of all ages,9 screening with a pelvic examination in asymptomatic women,10 and screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents ages 10 to 18 years.11

The lack of evidence regarding the value of a routine pelvic exam for asymptomatic women is surprising given how often this procedure is performed. The Task Force defined a pelvic exam as an “assessment of the external genitalia, internal speculum examination, bimanual palpation, and rectovaginal examination.”10 The Task Force found very little evidence on the accuracy and effectiveness of this exam for a range of gynecologic conditions other than cervical cancer, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, for which screening is recommended.10

The “I” statement on screening for adolescent idiopathic scoliosis in children and adolescents is an unusual revision of a “D” recommendation from 2004. At that time, the Task Force found that treatment of adolescent idiopathic scoliosis leads to health benefits in only a small proportion of individuals and that there are harms of treatment such as unnecessary bracing and referral to specialty care. For the most recent evidence report, the Task Force used a new methodology to assess treatment harms and concluded that the evidence is now inadequate. That finding, along with new evidence that “suggests that brace treatment can interrupt or slow scoliosis progression” led the Task Force to move away from a “D” recommendation.11

The enigmatic “C” recommendation

Perhaps the most difficult recommendation category to understand and implement is the “C” recommendation. With a “C” intervention, there is moderate certainty that the net benefit of universal implementation would be very small; but there are some individuals who might benefit from it, and physicians should offer it selectively.

The Task Force made one “C” recommendation over the past year: for adults who are not obese and who do not have other cardiovascular disease (CVD) risks, the net gain in referring them to behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity is small. However, the harms from such referrals are also small. Counseling interventions can result in healthier habits and in small improvements in intermediate outcomes, such as blood pressure, cholesterol levels, and weight. The effect on overall CVD mortality, though, has been minimal.12 The Task Force concluded that “[those] who are interested and ready to make behavioral changes may be most likely to benefit from behavioral counseling.”

1. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

2. USPSTF. Obesity in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/obesity-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

3. USPSTF. Preeclampsia: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/preeclampsia-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

4. USPSTF. Vision in children ages 6 months to 5 years: Screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/vision-in-children-ages-6-months-to-5-years-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

5. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

6. USPSTF. Ovarian cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/ovarian-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

7. USPSTF. Thyroid cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/thyroid-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

8. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

9. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 24, 2018.

10. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2018.

11. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

12. USPSTF. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/healthful-diet-and-physical-activity-for-cardiovascular-disease-prevention-in-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling. Accessed March 22, 2018.

13. Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6564.

14. USPSTF. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

15. Donahue SP, Baker CN; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137.2015-3597.

1. USPSTF. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neural-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

2. USPSTF. Obesity in children and adolescents: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/obesity-in-children-and-adolescents-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

3. USPSTF. Preeclampsia: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/preeclampsia-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

4. USPSTF. Vision in children ages 6 months to 5 years: Screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/vision-in-children-ages-6-months-to-5-years-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

5. USPSTF. Hormone therapy in postmenopausal women: primary prevention of chronic conditions. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/menopausal-hormone-therapy-preventive-medication1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

6. USPSTF. Ovarian cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/ovarian-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 24, 2018.

7. USPSTF. Thyroid cancer: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/thyroid-cancer-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

8. USPSTF. Obstructive sleep apnea in adults: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/obstructive-sleep-apnea-in-adults-screening. Accessed March 22, 2018.

9. USPSTF. Celiac disease: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/celiac-disease-screening. Accessed March 24, 2018.

10. USPSTF. Gynecological conditions: periodic screening with the pelvic examination. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/gynecological-conditions-screening-with-the-pelvic-examination. Accessed March 22, 2018.

11. USPSTF. Adolescent idiopathic scoliosis: screening. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/adolescent-idiopathic-scoliosis-screening1. Accessed March 22, 2018.

12. USPSTF. Healthful diet and physical activity for cardiovascular disease prevention in adults without known risk factors: behavioral counseling. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/healthful-diet-and-physical-activity-for-cardiovascular-disease-prevention-in-adults-without-known-risk-factors-behavioral-counseling. Accessed March 22, 2018.

13. Ananth CV, Keyes KM, Wapner RJ. Pre-eclampsia rates in the United States, 1980-2010: age-period-cohort analysis. BMJ. 2013;347:f6564.

14. USPSTF. Low-dose aspirin use for the prevention of morbidity and mortality from preeclampsia: preventive medication. Available at: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/low-dose-aspirin-use-for-the-prevention-of-morbidity-and-mortality-from-preeclampsia-preventive-medication. Accessed March 22, 2018.

15. Donahue SP, Baker CN; Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine, American Academy of Pediatrics; Section on Ophthalmology, American Academy of Pediatrics; American Association of Certified Orthoptists; American Association for Pediatric Ophthalmology and Strabismus; American Academy of Ophthalmology. Procedures for the evaluation of the visual system by pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2016;137.2015-3597.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2018;67(5):294-296,298-299.