User login

Verrucous Nodule on the Cheek

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pilomatrix Carcinoma

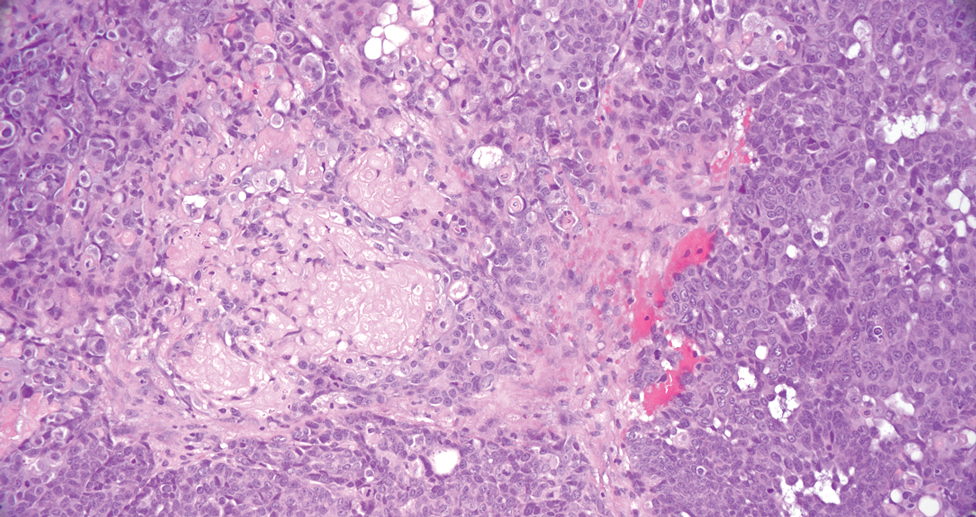

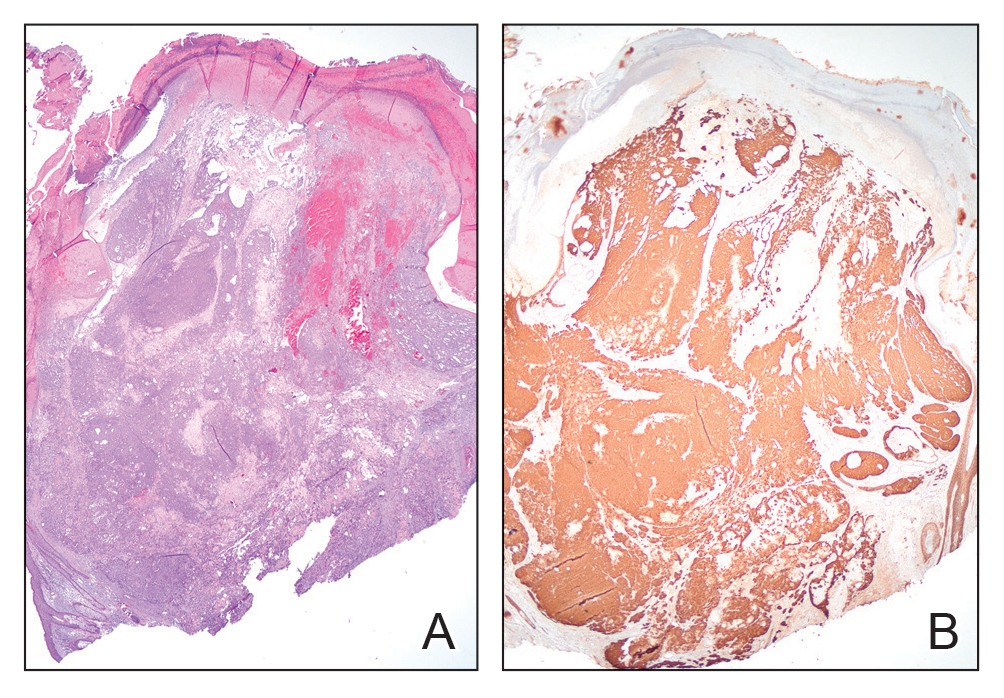

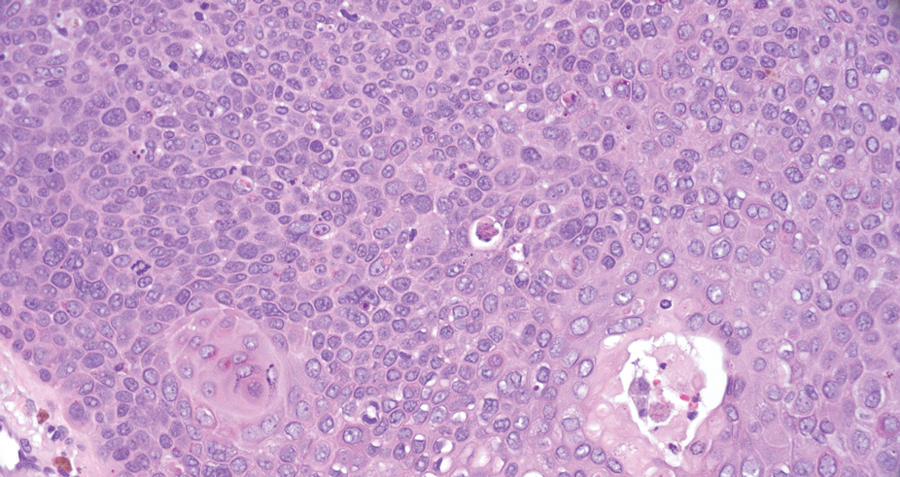

Histopathology revealed poorly circumscribed dermal nodules composed of large pleomorphic and highly atypical basaloid cells as well as increased mitoses. Foci of central necrosis admixed with keratinized cells containing pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and faint nuclear outlines without nuclei also were present. Immunohistochemistry for p63 was positive, while adipophilin, BerEP4, cytokeratin 20, and carcinoembryonic antigen were negative. Tumor cells also demonstrated strong and diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin staining, leading to a diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma (PC). The tumor was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Pilomatrix carcinoma, historically known as calcifying epitheliocarcinoma of Malherbe, is a rare, locally aggressive, low-grade adnexal tumor of germinative hair follicle matrix cell origin. Similar to its benign pilomatrixoma counterpart, malignant PC manifests as a firm, nontender, asymptomatic nodule most commonly (but not exclusively) manifesting in the head and neck region; however, in contrast to benign pilomatrixoma, PC is a rapidly growing tumor with a high rate of local recurrence after surgical excision and has the potential to become metastatic.1

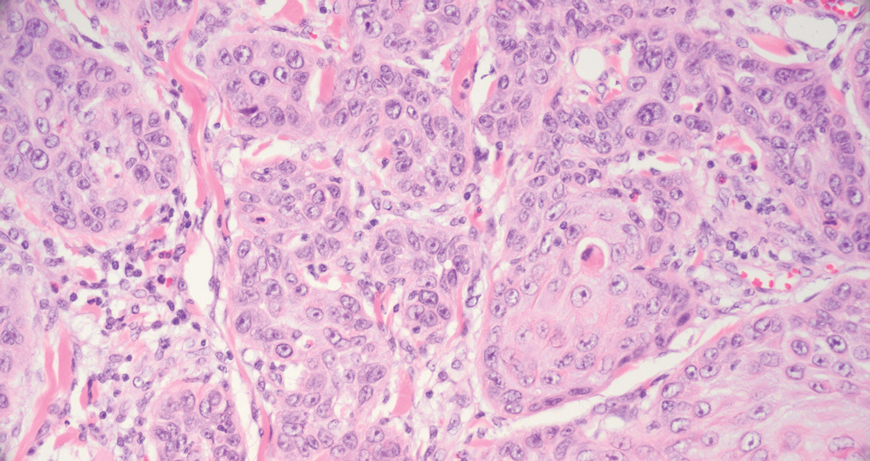

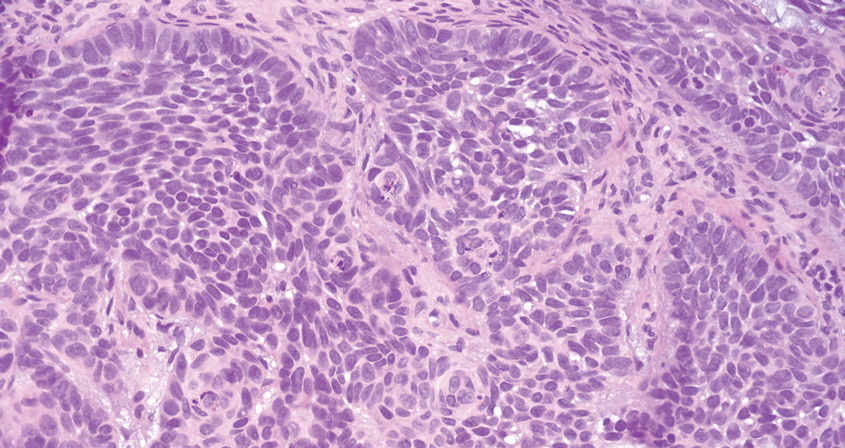

Pilomatrix carcinoma occurs most often in the fifth through seventh decades of life, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.3:1.1 Due to its rarity, PC management guidelines are not well defined. Histologically, PC will show asymmetry, poor circumscription, and an infiltrative growth pattern at low power. Pilomatrix carcinoma is further characterized by the presence of nodules of atypical basaloid cells demonstrating pleomorphism and nuclear hyperchromatism, increased mitotic index, and the presence of ghost cells (Figure 1).2 Ghost cells are evidence of matrical differentiation. The transition from basaloid to ghost cells may be abrupt. Intralesional calcification is possible but less common.2,3 The tumor nodules can be surrounded by a dense desmoplastic stroma with a predominantly lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2 Immunohistochemical stains that support a PC diagnosis include lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1), Ki-67, β-catenin, and p53. Although not specific for malignancy, nuclear LEF1 helps confirm matrical (hair matrix) differentiation.4 Pilomatrix carcinomas show a markedly elevated Ki-67 proliferation marker, reflecting high mitotic activity.5 While benign pilomatricoma may show patchy or minimal p53 staining, PC can demonstrate diffuse strong p53 positivity, consistent with the p53 pathway dysregulation seen in malignant matrical neoplasms.6 Most classically, PC stains strongly positive for nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin. Aberrant β-catenin disrupting normal Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf-Lef pathway regulation, which ultimately promotes cellular differentiation and division, is proposed to play a role in tumorigenesis.6,7

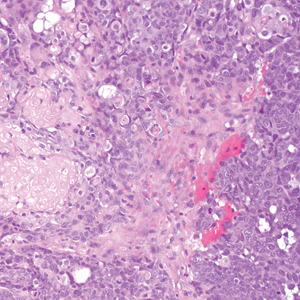

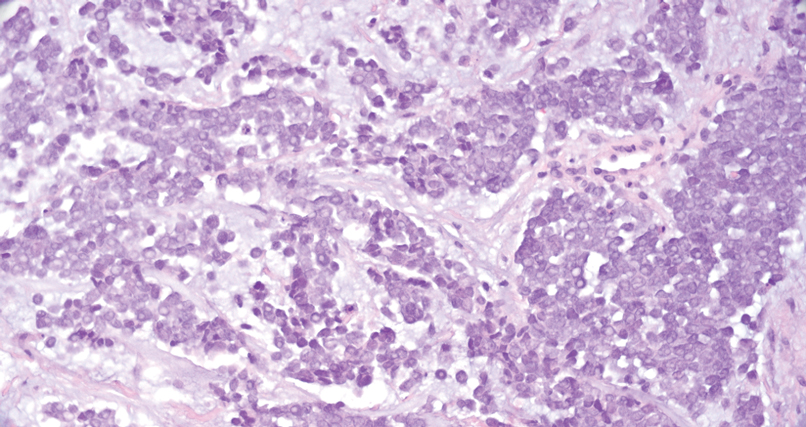

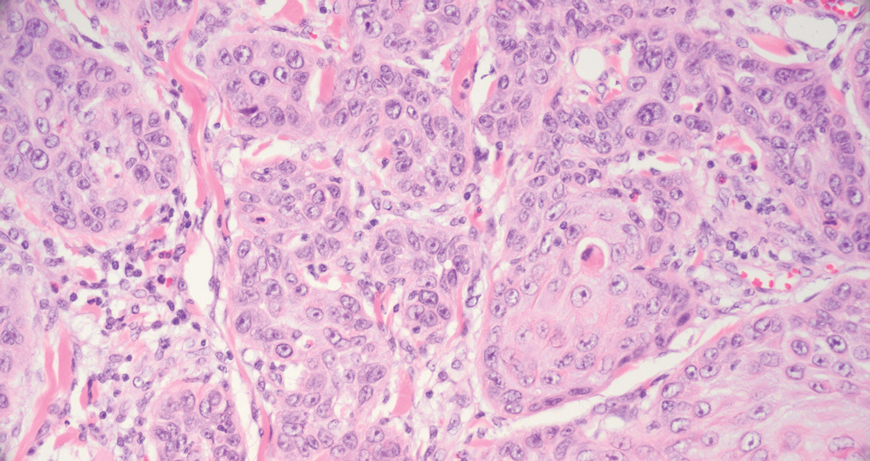

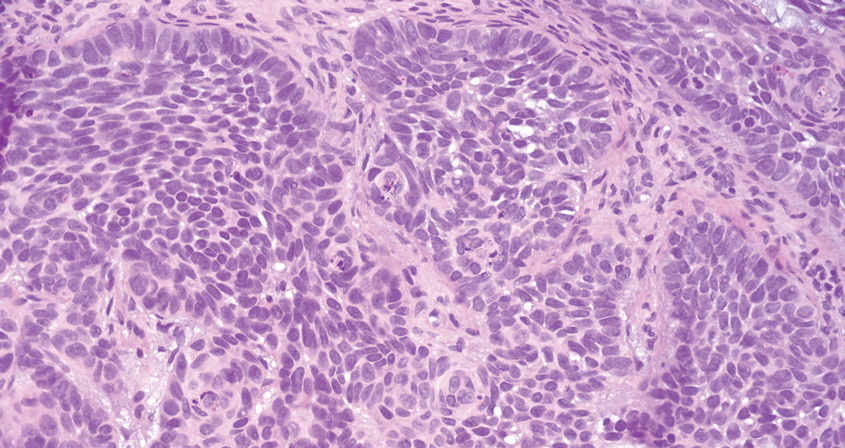

The differential diagnoses for PC include basal cell carcinoma (BCC), Merkel cell carcinoma, moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, and porocarcinoma. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor occurring on the head and neck regions that typically manifests as a slow-growing, flesh-colored, pink or pigmented papule, plaque, or nodule. Spontaneous bleeding or ulceration can sometimes occur. Basal cell carcinoma has various histologic subtypes, with tumors potentially exhibiting more than one histologic pattern. Common features of BCC include basaloid nodules arising from the epidermis, peripheral palisading, clefting artifacts, and a myxoid stroma (Figure 2).8 These features help distinguish BCC from PC histologically, although there is a rare matrical BCC subtype with a handful of reported cases expressing features of both.9 Staining can be a helpful differentiator as pancellular staining for LEF1, and β-catenin is exclusively observed in the pilomatrixoma and PC, in contrast to BCC, which shows staining confined to focal germinative matrix cell nests.10

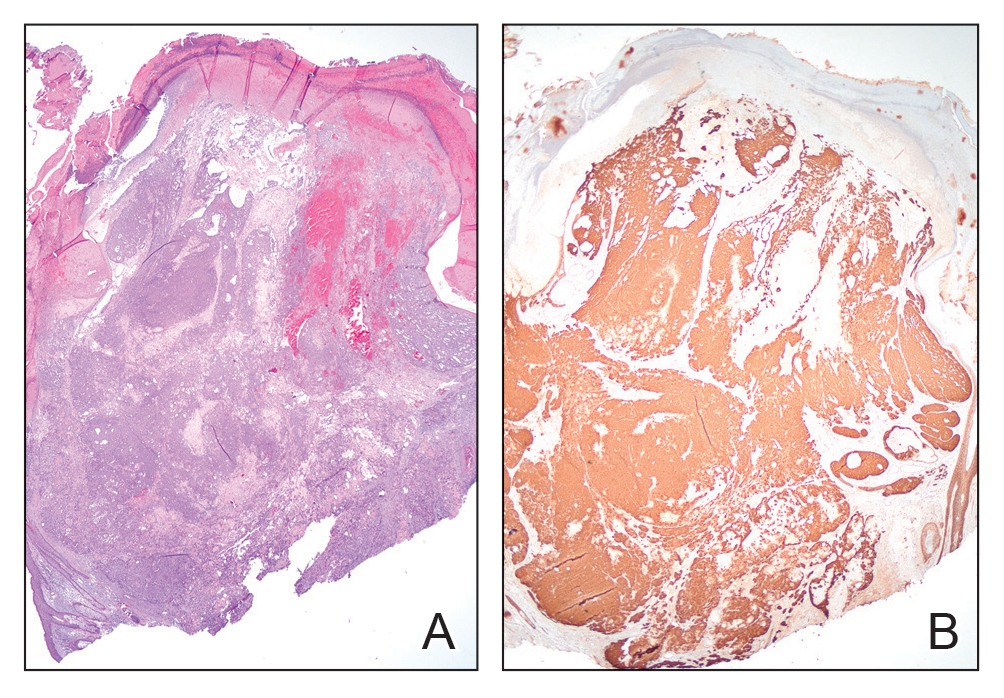

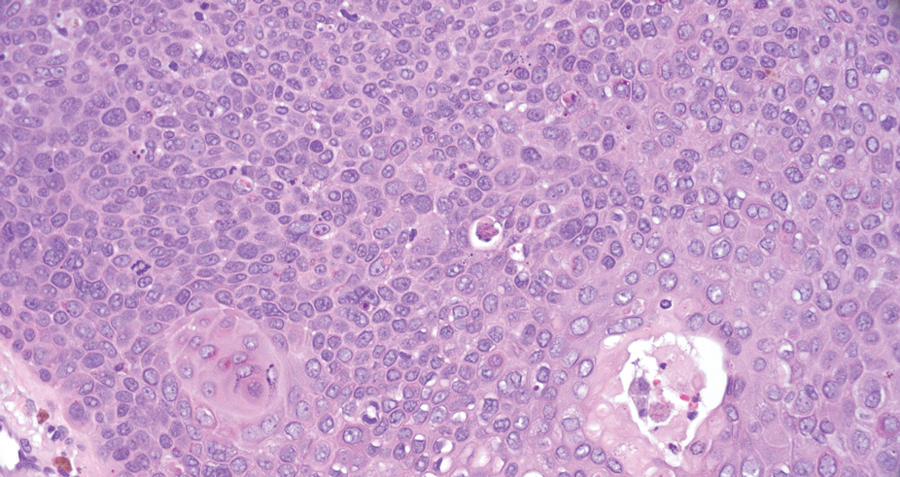

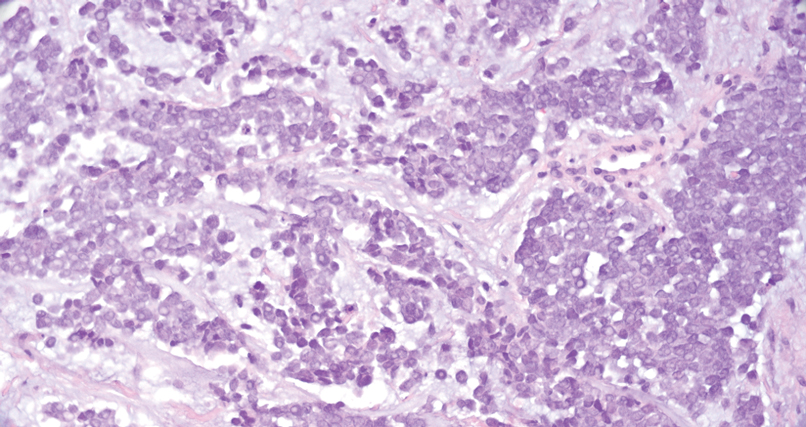

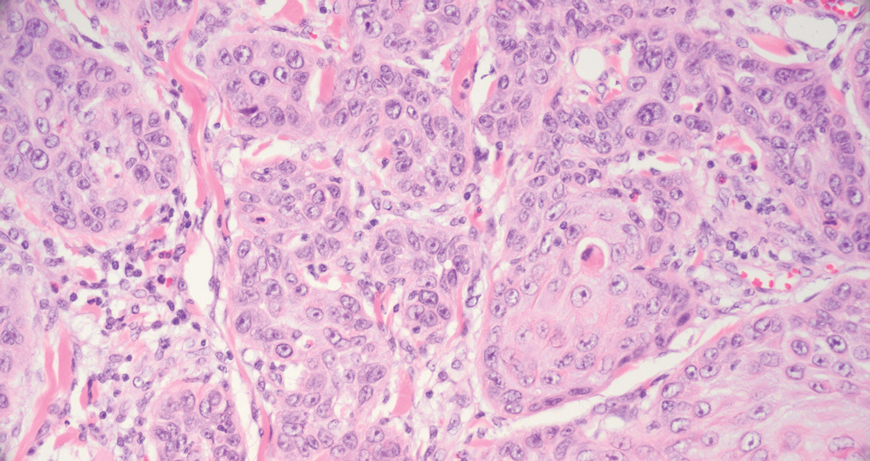

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) also commonly manifests clinically in the head and neck region and is associated with sun damage. Squamous cell carcinoma can be histologically graded based on cellular differentiation, from well differentiated to poorly differentiated subtypes. Moderately differentiated SCC is characterized histologically by reduced keratinization, frequent loss of intercellular bridges, and enlarged pleomorphic cells demonstrating a high degree of atypia and frequent abnormal mitoses (Figure 3).11 Similar to PC, moderately differentiated SCC also may comprise basaloid cells but lacks shadow cells. Further distinction from PC can be made through immunohistochemistry. Expression of p63, p40, MNF116, and CK903 expression help identify the squamous origin of the tumor and are useful in the diagnosis of less-differentiated SCC.12 In addition, SCC does not show matrical differentiation (ghost cells).

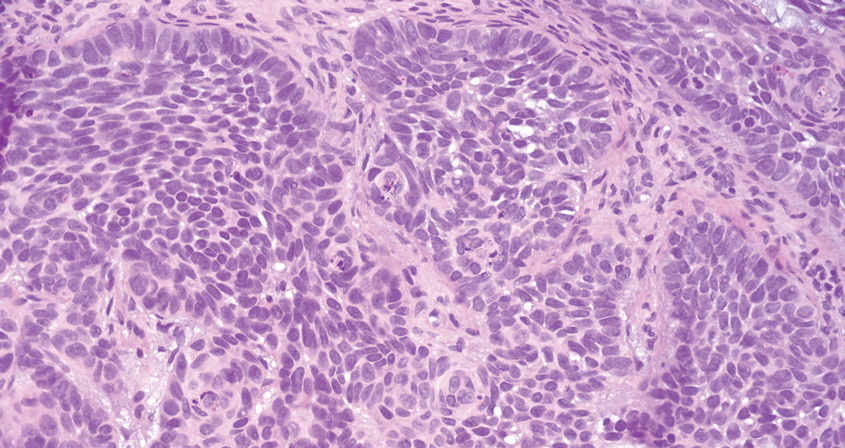

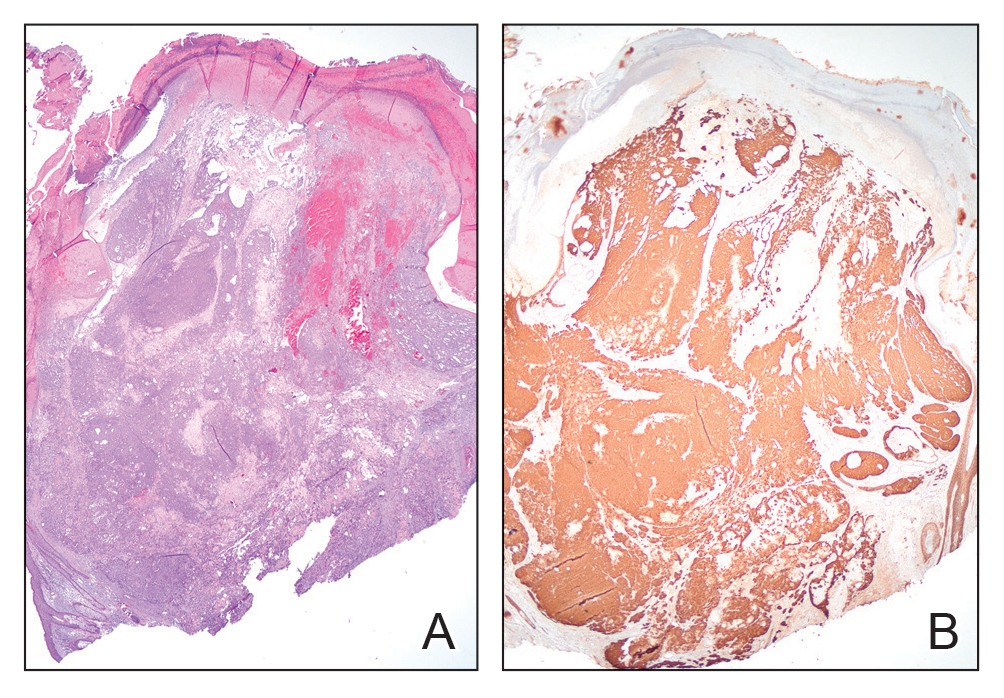

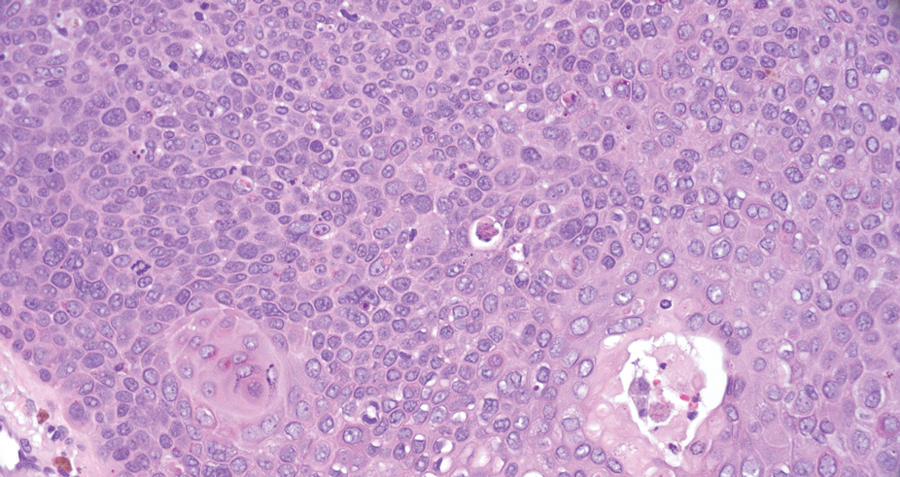

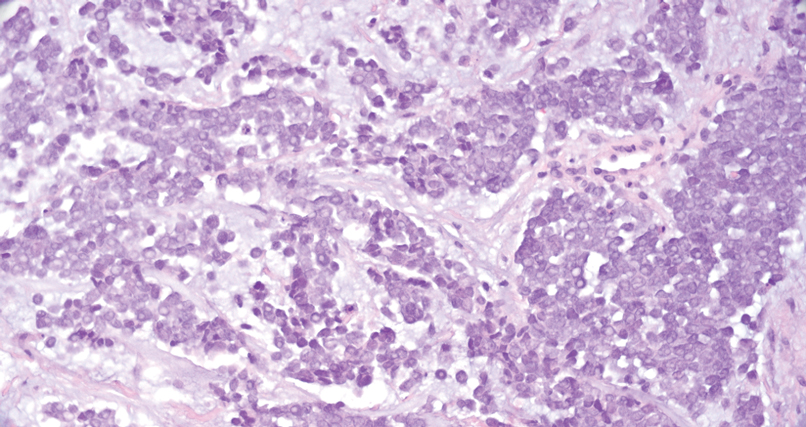

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare and aggressive skin cancer that manifests as a rapidly growing, sometimes ulcerating nodule or plaque with a predilection for sun‐exposed areas of the skin. Merkel cell carcinoma is characterized by neuroendocrine differentiation. The gold standard diagnostic modalities are histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Characteristic histopathologic findings include diffuse atypical blue cells with large nuclei, minimal cytoplasm, and frequent mitoses (Figure 4).13,14 Staining with cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin and chromogranin A on immunohistochemistry supports the diagnosis, as does positive AE1/3; neuron-specific enolase and epithelial membrane antigen; and negative S100, carcinoembryonic antigen, and leukocyte common antigen staining.13,14

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignant growth arising from the cutaneous intraepidermal ducts of the sweat glands. Porocarcinomas may originate from benign eccrine poromas, but the etiology remains poorly understood. Clinically, porocarcinoma manifests as a flesh-colored, erythematous, or violaceous firm, single, dome-shaped papule or nodule that can ulcerate and may be asymptomatic, itchy, or painful.15 Porocarcinoma poses a diagnostic challenge due to the variability of both its clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. The histology often resembles that of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or poroma. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, porocarcinoma is characterized by poromatous basaloid cells with cytologic atypia and ductal differentiation. Common histopathologic features include formation of mature ducts lined with cuboidal epithelial cells, foci of necrosis, intracytoplasmic lumina, and squamous differentiation (Figure 5).15 Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunohistochemical staining to identify ductal structures may help to distinguish porocarcinoma from other tumors. Cluster of Differentiation 117/c-KIT, cytokeratin 19, and BerEP4 positivity also have been shown to be useful in diagnosing porocarcinoma. CD117/c-KIT highlights eccrine ductal differentiation16; CK19 supports adnexal ductal differentiation and often is increased in malignant poroid neoplasms17; and BerEP4, although classically used for BCC diagnosis, also may be positive in porocarcinoma, particularly in ductal areas, and can support the diagnosis.18

- Toffoli L, Bazzacco G, Conforti C, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: report of two cases of the head and review of the literature. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:1426-1438. doi:10.3390/curroncol30020109

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.E2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.042

- Jones C, Twoon M, Ho W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 12-year experience and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:33-38. doi:10.1111/cup.13046

- Reymundo-Jiménez A, Martos-Cabrera L, Muñoz-Hernández P, et al. Usefulness of LEF-1 immunostaining for the diagnosis of matricoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T907-T910. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.08.003

- Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Pilomatrix carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2491-2498. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930415)71:8<2491 ::aid-cncr2820710811>3.0.co;2-i

- Lazar AJF, Calonje E, Grayson W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinomas contain mutations in CTNNB1, the gene encoding β-catenin. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:148-157. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00267.x

- Abula A, Ma SQ, Wang S, et al. Case report: Pilomatrix carcinoma with PDL1 expression and CDKN2A aberrant. Front Immunol. 2024;15. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1337400

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

- Kanitakis J, Ducroux E, Hoelt P, et al. Basal-cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation: report of a new case in a renal-transplant recipient and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:E115-E118. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000001146

- White C, Farsi M, Esguerra D, et al. Not your average skin cancer: a rare case of pilomatrix carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020; 13:40-42.

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2010;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Balas¸escu E, Gheorghe AC, Moroianu A, et al. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis and staging of cutaneous squamouscell carcinomas (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:383. doi:10.3892 /etm.2022.11308

- Zhang Z, Shi W, Zhang R. Facial Merkel cell carcinoma in a 92-year-old man: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:E9523. doi:10.1002/ccr3.9523

- Rapini R. Practical Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2021.

- Miyamoto K, Yanagi T, Maeda T, et al. Diagnosis and management of porocarcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14:5232. doi:10.3390 /cancers14215232

- Goto K. Immunohistochemistry for CD117 (KIT) is effective in distinguishing cutaneous adnexal tumors with apocrine/eccrine or sebaceous differentiation from other epithelial tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:480-488. doi:10.1111/cup.12492

- Requena L, Sangüeza O. General principles for the histopathologic diagnosis of neoplasms with eccrine and apocrine differentiation. Classification and histopathologic criteria for eccrine and apocrine differentiation. In: Requena L, Sangüeza O, eds. Cutaneous Adnexal Neoplasms. Springer International Publishing; 2017:19-24. doi:10.1007/978- 3-319-45704-8_2

- Huet P, Dandurand M, Pignodel C, et al. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:860-864. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90105-x

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pilomatrix Carcinoma

Histopathology revealed poorly circumscribed dermal nodules composed of large pleomorphic and highly atypical basaloid cells as well as increased mitoses. Foci of central necrosis admixed with keratinized cells containing pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and faint nuclear outlines without nuclei also were present. Immunohistochemistry for p63 was positive, while adipophilin, BerEP4, cytokeratin 20, and carcinoembryonic antigen were negative. Tumor cells also demonstrated strong and diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin staining, leading to a diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma (PC). The tumor was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Pilomatrix carcinoma, historically known as calcifying epitheliocarcinoma of Malherbe, is a rare, locally aggressive, low-grade adnexal tumor of germinative hair follicle matrix cell origin. Similar to its benign pilomatrixoma counterpart, malignant PC manifests as a firm, nontender, asymptomatic nodule most commonly (but not exclusively) manifesting in the head and neck region; however, in contrast to benign pilomatrixoma, PC is a rapidly growing tumor with a high rate of local recurrence after surgical excision and has the potential to become metastatic.1

Pilomatrix carcinoma occurs most often in the fifth through seventh decades of life, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.3:1.1 Due to its rarity, PC management guidelines are not well defined. Histologically, PC will show asymmetry, poor circumscription, and an infiltrative growth pattern at low power. Pilomatrix carcinoma is further characterized by the presence of nodules of atypical basaloid cells demonstrating pleomorphism and nuclear hyperchromatism, increased mitotic index, and the presence of ghost cells (Figure 1).2 Ghost cells are evidence of matrical differentiation. The transition from basaloid to ghost cells may be abrupt. Intralesional calcification is possible but less common.2,3 The tumor nodules can be surrounded by a dense desmoplastic stroma with a predominantly lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2 Immunohistochemical stains that support a PC diagnosis include lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1), Ki-67, β-catenin, and p53. Although not specific for malignancy, nuclear LEF1 helps confirm matrical (hair matrix) differentiation.4 Pilomatrix carcinomas show a markedly elevated Ki-67 proliferation marker, reflecting high mitotic activity.5 While benign pilomatricoma may show patchy or minimal p53 staining, PC can demonstrate diffuse strong p53 positivity, consistent with the p53 pathway dysregulation seen in malignant matrical neoplasms.6 Most classically, PC stains strongly positive for nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin. Aberrant β-catenin disrupting normal Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf-Lef pathway regulation, which ultimately promotes cellular differentiation and division, is proposed to play a role in tumorigenesis.6,7

The differential diagnoses for PC include basal cell carcinoma (BCC), Merkel cell carcinoma, moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, and porocarcinoma. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor occurring on the head and neck regions that typically manifests as a slow-growing, flesh-colored, pink or pigmented papule, plaque, or nodule. Spontaneous bleeding or ulceration can sometimes occur. Basal cell carcinoma has various histologic subtypes, with tumors potentially exhibiting more than one histologic pattern. Common features of BCC include basaloid nodules arising from the epidermis, peripheral palisading, clefting artifacts, and a myxoid stroma (Figure 2).8 These features help distinguish BCC from PC histologically, although there is a rare matrical BCC subtype with a handful of reported cases expressing features of both.9 Staining can be a helpful differentiator as pancellular staining for LEF1, and β-catenin is exclusively observed in the pilomatrixoma and PC, in contrast to BCC, which shows staining confined to focal germinative matrix cell nests.10

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) also commonly manifests clinically in the head and neck region and is associated with sun damage. Squamous cell carcinoma can be histologically graded based on cellular differentiation, from well differentiated to poorly differentiated subtypes. Moderately differentiated SCC is characterized histologically by reduced keratinization, frequent loss of intercellular bridges, and enlarged pleomorphic cells demonstrating a high degree of atypia and frequent abnormal mitoses (Figure 3).11 Similar to PC, moderately differentiated SCC also may comprise basaloid cells but lacks shadow cells. Further distinction from PC can be made through immunohistochemistry. Expression of p63, p40, MNF116, and CK903 expression help identify the squamous origin of the tumor and are useful in the diagnosis of less-differentiated SCC.12 In addition, SCC does not show matrical differentiation (ghost cells).

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare and aggressive skin cancer that manifests as a rapidly growing, sometimes ulcerating nodule or plaque with a predilection for sun‐exposed areas of the skin. Merkel cell carcinoma is characterized by neuroendocrine differentiation. The gold standard diagnostic modalities are histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Characteristic histopathologic findings include diffuse atypical blue cells with large nuclei, minimal cytoplasm, and frequent mitoses (Figure 4).13,14 Staining with cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin and chromogranin A on immunohistochemistry supports the diagnosis, as does positive AE1/3; neuron-specific enolase and epithelial membrane antigen; and negative S100, carcinoembryonic antigen, and leukocyte common antigen staining.13,14

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignant growth arising from the cutaneous intraepidermal ducts of the sweat glands. Porocarcinomas may originate from benign eccrine poromas, but the etiology remains poorly understood. Clinically, porocarcinoma manifests as a flesh-colored, erythematous, or violaceous firm, single, dome-shaped papule or nodule that can ulcerate and may be asymptomatic, itchy, or painful.15 Porocarcinoma poses a diagnostic challenge due to the variability of both its clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. The histology often resembles that of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or poroma. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, porocarcinoma is characterized by poromatous basaloid cells with cytologic atypia and ductal differentiation. Common histopathologic features include formation of mature ducts lined with cuboidal epithelial cells, foci of necrosis, intracytoplasmic lumina, and squamous differentiation (Figure 5).15 Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunohistochemical staining to identify ductal structures may help to distinguish porocarcinoma from other tumors. Cluster of Differentiation 117/c-KIT, cytokeratin 19, and BerEP4 positivity also have been shown to be useful in diagnosing porocarcinoma. CD117/c-KIT highlights eccrine ductal differentiation16; CK19 supports adnexal ductal differentiation and often is increased in malignant poroid neoplasms17; and BerEP4, although classically used for BCC diagnosis, also may be positive in porocarcinoma, particularly in ductal areas, and can support the diagnosis.18

THE DIAGNOSIS: Pilomatrix Carcinoma

Histopathology revealed poorly circumscribed dermal nodules composed of large pleomorphic and highly atypical basaloid cells as well as increased mitoses. Foci of central necrosis admixed with keratinized cells containing pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and faint nuclear outlines without nuclei also were present. Immunohistochemistry for p63 was positive, while adipophilin, BerEP4, cytokeratin 20, and carcinoembryonic antigen were negative. Tumor cells also demonstrated strong and diffuse nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin staining, leading to a diagnosis of pilomatrix carcinoma (PC). The tumor was treated with Mohs micrographic surgery, and the patient was subsequently lost to follow-up.

Pilomatrix carcinoma, historically known as calcifying epitheliocarcinoma of Malherbe, is a rare, locally aggressive, low-grade adnexal tumor of germinative hair follicle matrix cell origin. Similar to its benign pilomatrixoma counterpart, malignant PC manifests as a firm, nontender, asymptomatic nodule most commonly (but not exclusively) manifesting in the head and neck region; however, in contrast to benign pilomatrixoma, PC is a rapidly growing tumor with a high rate of local recurrence after surgical excision and has the potential to become metastatic.1

Pilomatrix carcinoma occurs most often in the fifth through seventh decades of life, with a male-to-female ratio of approximately 1.3:1.1 Due to its rarity, PC management guidelines are not well defined. Histologically, PC will show asymmetry, poor circumscription, and an infiltrative growth pattern at low power. Pilomatrix carcinoma is further characterized by the presence of nodules of atypical basaloid cells demonstrating pleomorphism and nuclear hyperchromatism, increased mitotic index, and the presence of ghost cells (Figure 1).2 Ghost cells are evidence of matrical differentiation. The transition from basaloid to ghost cells may be abrupt. Intralesional calcification is possible but less common.2,3 The tumor nodules can be surrounded by a dense desmoplastic stroma with a predominantly lymphohistiocytic infiltrate.2 Immunohistochemical stains that support a PC diagnosis include lymphoid enhancer-binding factor 1 (LEF1), Ki-67, β-catenin, and p53. Although not specific for malignancy, nuclear LEF1 helps confirm matrical (hair matrix) differentiation.4 Pilomatrix carcinomas show a markedly elevated Ki-67 proliferation marker, reflecting high mitotic activity.5 While benign pilomatricoma may show patchy or minimal p53 staining, PC can demonstrate diffuse strong p53 positivity, consistent with the p53 pathway dysregulation seen in malignant matrical neoplasms.6 Most classically, PC stains strongly positive for nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin. Aberrant β-catenin disrupting normal Wnt/β-catenin/Tcf-Lef pathway regulation, which ultimately promotes cellular differentiation and division, is proposed to play a role in tumorigenesis.6,7

The differential diagnoses for PC include basal cell carcinoma (BCC), Merkel cell carcinoma, moderately differentiated squamous cell carcinoma, and porocarcinoma. Basal cell carcinoma is a common tumor occurring on the head and neck regions that typically manifests as a slow-growing, flesh-colored, pink or pigmented papule, plaque, or nodule. Spontaneous bleeding or ulceration can sometimes occur. Basal cell carcinoma has various histologic subtypes, with tumors potentially exhibiting more than one histologic pattern. Common features of BCC include basaloid nodules arising from the epidermis, peripheral palisading, clefting artifacts, and a myxoid stroma (Figure 2).8 These features help distinguish BCC from PC histologically, although there is a rare matrical BCC subtype with a handful of reported cases expressing features of both.9 Staining can be a helpful differentiator as pancellular staining for LEF1, and β-catenin is exclusively observed in the pilomatrixoma and PC, in contrast to BCC, which shows staining confined to focal germinative matrix cell nests.10

Squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) also commonly manifests clinically in the head and neck region and is associated with sun damage. Squamous cell carcinoma can be histologically graded based on cellular differentiation, from well differentiated to poorly differentiated subtypes. Moderately differentiated SCC is characterized histologically by reduced keratinization, frequent loss of intercellular bridges, and enlarged pleomorphic cells demonstrating a high degree of atypia and frequent abnormal mitoses (Figure 3).11 Similar to PC, moderately differentiated SCC also may comprise basaloid cells but lacks shadow cells. Further distinction from PC can be made through immunohistochemistry. Expression of p63, p40, MNF116, and CK903 expression help identify the squamous origin of the tumor and are useful in the diagnosis of less-differentiated SCC.12 In addition, SCC does not show matrical differentiation (ghost cells).

Merkel cell carcinoma is a rare and aggressive skin cancer that manifests as a rapidly growing, sometimes ulcerating nodule or plaque with a predilection for sun‐exposed areas of the skin. Merkel cell carcinoma is characterized by neuroendocrine differentiation. The gold standard diagnostic modalities are histopathology and immunohistochemistry. Characteristic histopathologic findings include diffuse atypical blue cells with large nuclei, minimal cytoplasm, and frequent mitoses (Figure 4).13,14 Staining with cytokeratin 20 and neuroendocrine markers such as synaptophysin and chromogranin A on immunohistochemistry supports the diagnosis, as does positive AE1/3; neuron-specific enolase and epithelial membrane antigen; and negative S100, carcinoembryonic antigen, and leukocyte common antigen staining.13,14

Porocarcinoma is a rare malignant growth arising from the cutaneous intraepidermal ducts of the sweat glands. Porocarcinomas may originate from benign eccrine poromas, but the etiology remains poorly understood. Clinically, porocarcinoma manifests as a flesh-colored, erythematous, or violaceous firm, single, dome-shaped papule or nodule that can ulcerate and may be asymptomatic, itchy, or painful.15 Porocarcinoma poses a diagnostic challenge due to the variability of both its clinical presentation and histopathologic findings. The histology often resembles that of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma or poroma. On hematoxylin and eosin staining, porocarcinoma is characterized by poromatous basaloid cells with cytologic atypia and ductal differentiation. Common histopathologic features include formation of mature ducts lined with cuboidal epithelial cells, foci of necrosis, intracytoplasmic lumina, and squamous differentiation (Figure 5).15 Carcinoembryonic antigen and epithelial membrane antigen immunohistochemical staining to identify ductal structures may help to distinguish porocarcinoma from other tumors. Cluster of Differentiation 117/c-KIT, cytokeratin 19, and BerEP4 positivity also have been shown to be useful in diagnosing porocarcinoma. CD117/c-KIT highlights eccrine ductal differentiation16; CK19 supports adnexal ductal differentiation and often is increased in malignant poroid neoplasms17; and BerEP4, although classically used for BCC diagnosis, also may be positive in porocarcinoma, particularly in ductal areas, and can support the diagnosis.18

- Toffoli L, Bazzacco G, Conforti C, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: report of two cases of the head and review of the literature. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:1426-1438. doi:10.3390/curroncol30020109

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.E2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.042

- Jones C, Twoon M, Ho W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 12-year experience and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:33-38. doi:10.1111/cup.13046

- Reymundo-Jiménez A, Martos-Cabrera L, Muñoz-Hernández P, et al. Usefulness of LEF-1 immunostaining for the diagnosis of matricoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T907-T910. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.08.003

- Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Pilomatrix carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2491-2498. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930415)71:8<2491 ::aid-cncr2820710811>3.0.co;2-i

- Lazar AJF, Calonje E, Grayson W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinomas contain mutations in CTNNB1, the gene encoding β-catenin. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:148-157. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00267.x

- Abula A, Ma SQ, Wang S, et al. Case report: Pilomatrix carcinoma with PDL1 expression and CDKN2A aberrant. Front Immunol. 2024;15. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1337400

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

- Kanitakis J, Ducroux E, Hoelt P, et al. Basal-cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation: report of a new case in a renal-transplant recipient and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:E115-E118. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000001146

- White C, Farsi M, Esguerra D, et al. Not your average skin cancer: a rare case of pilomatrix carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020; 13:40-42.

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2010;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Balas¸escu E, Gheorghe AC, Moroianu A, et al. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis and staging of cutaneous squamouscell carcinomas (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:383. doi:10.3892 /etm.2022.11308

- Zhang Z, Shi W, Zhang R. Facial Merkel cell carcinoma in a 92-year-old man: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:E9523. doi:10.1002/ccr3.9523

- Rapini R. Practical Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2021.

- Miyamoto K, Yanagi T, Maeda T, et al. Diagnosis and management of porocarcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14:5232. doi:10.3390 /cancers14215232

- Goto K. Immunohistochemistry for CD117 (KIT) is effective in distinguishing cutaneous adnexal tumors with apocrine/eccrine or sebaceous differentiation from other epithelial tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:480-488. doi:10.1111/cup.12492

- Requena L, Sangüeza O. General principles for the histopathologic diagnosis of neoplasms with eccrine and apocrine differentiation. Classification and histopathologic criteria for eccrine and apocrine differentiation. In: Requena L, Sangüeza O, eds. Cutaneous Adnexal Neoplasms. Springer International Publishing; 2017:19-24. doi:10.1007/978- 3-319-45704-8_2

- Huet P, Dandurand M, Pignodel C, et al. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:860-864. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90105-x

- Toffoli L, Bazzacco G, Conforti C, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: report of two cases of the head and review of the literature. Curr Oncol. 2023;30:1426-1438. doi:10.3390/curroncol30020109

- Herrmann JL, Allan A, Trapp KM, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 13 new cases and review of the literature with emphasis on predictors of metastasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:38-43.E2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2014.02.042

- Jones C, Twoon M, Ho W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinoma: 12-year experience and review of the literature. J Cutan Pathol. 2018;45:33-38. doi:10.1111/cup.13046

- Reymundo-Jiménez A, Martos-Cabrera L, Muñoz-Hernández P, et al. Usefulness of LEF-1 immunostaining for the diagnosis of matricoma. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2022;113:T907-T910. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2022.08.003

- Sau P, Lupton GP, Graham JH. Pilomatrix carcinoma. Cancer. 1993;71:2491-2498. doi:10.1002/1097-0142(19930415)71:8<2491 ::aid-cncr2820710811>3.0.co;2-i

- Lazar AJF, Calonje E, Grayson W, et al. Pilomatrix carcinomas contain mutations in CTNNB1, the gene encoding β-catenin. J Cutan Pathol. 2005;32:148-157. doi:10.1111/j.0303-6987.2005.00267.x

- Abula A, Ma SQ, Wang S, et al. Case report: Pilomatrix carcinoma with PDL1 expression and CDKN2A aberrant. Front Immunol. 2024;15. doi:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1337400

- Cameron MC, Lee E, Hibler BP, et al. Basal cell carcinoma: epidemiology; pathophysiology; clinical and histological subtypes; and disease associations. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:303-317. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2018.03.060

- Kanitakis J, Ducroux E, Hoelt P, et al. Basal-cell carcinoma with matrical differentiation: report of a new case in a renal-transplant recipient and literature review. Am J Dermatopathol. 2018;40:E115-E118. doi:10.1097 /DAD.0000000000001146

- White C, Farsi M, Esguerra D, et al. Not your average skin cancer: a rare case of pilomatrix carcinoma. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2020; 13:40-42.

- Yanofsky VR, Mercer SE, Phelps RG. Histopathological variants of cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: a review. J Skin Cancer. 2010;2011:210813. doi:10.1155/2011/210813

- Balas¸escu E, Gheorghe AC, Moroianu A, et al. Role of immunohistochemistry in the diagnosis and staging of cutaneous squamouscell carcinomas (review). Exp Ther Med. 2022;23:383. doi:10.3892 /etm.2022.11308

- Zhang Z, Shi W, Zhang R. Facial Merkel cell carcinoma in a 92-year-old man: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:E9523. doi:10.1002/ccr3.9523

- Rapini R. Practical Dermatopathology. 3rd ed. Elsevier; 2021.

- Miyamoto K, Yanagi T, Maeda T, et al. Diagnosis and management of porocarcinoma. Cancers. 2022;14:5232. doi:10.3390 /cancers14215232

- Goto K. Immunohistochemistry for CD117 (KIT) is effective in distinguishing cutaneous adnexal tumors with apocrine/eccrine or sebaceous differentiation from other epithelial tumors of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2015;42:480-488. doi:10.1111/cup.12492

- Requena L, Sangüeza O. General principles for the histopathologic diagnosis of neoplasms with eccrine and apocrine differentiation. Classification and histopathologic criteria for eccrine and apocrine differentiation. In: Requena L, Sangüeza O, eds. Cutaneous Adnexal Neoplasms. Springer International Publishing; 2017:19-24. doi:10.1007/978- 3-319-45704-8_2

- Huet P, Dandurand M, Pignodel C, et al. Metastasizing eccrine porocarcinoma: report of a case and review of the literature. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35:860-864. doi:10.1016/s0190-9622(96)90105-x

Verrucous Nodule on the Cheek

Verrucous Nodule on the Cheek

A 73-year-old man presented to the dermatology department for evaluation of an asymptomatic verrucous brown nodule on the right superior malar cheek of a few months’ duration. The patient reported a history of hyperlipidemia and hypertension and no prior treatment at the site of the nodule. A biopsy of the lesion was performed.