User login

The best evidence about the diagnostic evaluation of resting tachycardias in adults is currently outlined by practice guidelines.1 Initial evaluation includes clinical history, physical examination, and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). If the initial evaluation suggests a sinus tachycardia with narrow QRS complexes and no identifiable secondary cause, a 24-hour Holter monitor is usually recommended (strength of recommendation: C, based on expert opinion).

Wide-complex tachycardias and irregular heartbeats should be urgently managed

Laurel Woods, MD

Group Health Family Medicine Residency Program, Seattle, Wash

This Clinical Inquiry organizes a rational approach to tachycardia, which is frequently an incidental and asymptomatic finding on patient intake. The recommendation of evaluating a 12-lead ECG for sinus vs non-sinus tachycardia, then further investigating underlying causes, helps frame the workup in an approachable manner. Particularly helpful is the pointer that the wide-complex tachycardias and irregular heartbeats should be urgently managed, whereas the rest can be assessed at a more relaxed pace. For nonurgent cases it is important to keep in mind the differential diagnosis and rationally evaluate the likely causes. In my patient population, I tend to see sinus tachycardias in young healthy patients in whom no secondary cause aside from anxiety is identified. Oftentimes I follow up after initiating treatment for anxiety or its underlying cause and find that the tachycardia has resolved. In these cases, I have been less aggressive about ordering a 24-hour Holter monitor.

Evidence Summary

Heart rate varies by age; however, tachycardia in adults is usually defined as a rate exceeding 100 beats/minute.1 Tachycardia at rest requires a diagnostic evaluation. However, our search found no systematic reviews, randomized trials, or prospective cohort studies relevant to this question. The highest level of evidence we located was an international practice guideline developed by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines.1

This joint guideline recommends that the diagnostic evaluation of a hemodynamically stable patient should begin with a clinical history, physical examination with relevant labs, and 12-lead ECG.1 Many patients with tachycardia are asymptomatic; however, common symptoms and complaints include palpitations, fatigue, lightheadedness, chest discomfort, dyspnea, presyncope, or syncope.1 If the patient has experienced symptoms, it is of crucial importance to obtain a clinical history describing the pattern in terms of the number of episodes, duration, frequency, mode of onset, and possible triggers.1

The main goals of the physical examination, labs, and the 12-lead ECG are to determine if the patient has a sinus or non-sinus tachycardia and to look for other findings that may suggest either a cause for the tachycardia or any complications resulting from the tachycardia.

First, determine if the patient’s heartbeat is regular or irregular. Atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation are common causes of an irregular heartbeat that can easily be diagnosed with a 12-lead ECG. Second, determine the width of the QRS interval: narrow QRS complex tachycardias are supraventricular (from the sinus node, the atria, and the atrioventricular junction) in origin, and wide QRS complex tachycardias are usually ventricular (from all sites below the AV junction).2,3 If an irregular heartbeat or wide-complex tachycardia is detected, appropriate management (including possible urgent referrals) should begin immediately.1 A stable patient with a regular rhythm and a narrow QRS complex can be further investigated at a more relaxed pace.

Refer to the TABLE for a listing of common secondary causes for sinus tachycardia, which should direct lab investigations. If no secondary cause is easily identifiable, a 24-hour monitor is recommended as the next step.

TABLE

Potential secondary causes of resting sinus tachycardia5-7

| Hyperthyroidism |

| Fever |

| Sepsis |

| Anxiety |

| Pheochromocytoma |

| Anemia |

| Hypotension and shock |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Acute coronary ischemia and myocardial infarction |

| Heart failure |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

| Hypoxia exposure to medications, stimulants, or illicit drugs |

| Malignancy |

| Pregnancy |

Recommendations from others

Textbook chapters and other review articles regarding this topic describe a similar initial evaluation and provide further details about interpreting the 12-lead ECG.2-7 The most relevant and recent review article suggests that further investigation of narrow QRS complex tachycardias with a regular rate currently involves 4 diagnostic categories: normal sinus tachycardia (ie, secondary cause can be identified), inappropriate sinus tachycardia (IST), postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and sinus node reentry tachycardia (SNRT).4

If a secondary cause is identified, it should be treated appropriately. If no underlying cause is discovered, a 24-hour Holter monitor is recommended.

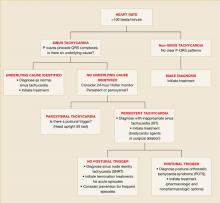

Persistent sinus tachycardia (sometimes with nocturnal normalization of heart rate) is diagnosed as IST.4 If the monitor shows paroxysmal episodes of sinus tachycardia, determine if they are triggered by orthostasis and relieved by recumbency (confirm with head upright tilt test) to make the diagnosis of POTS. If it is not POTS, the recordings from the 24-hour Holter monitor help make the diagnosis of SNRT, which consists of sudden, paroxysmal, and usually nonsustained tachycardia.4 The FIGURE shows an algorithm of one common diagnostic strategy for evaluation of tachycardia.2-7

FIGURE

Diagnostic algorithm for evaluating tachycardias4

1. American College of Cardiology/American Heart association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ESC). ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with surpraventricular arrythmias-executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1493-1531.

2. Yusuf S, Camm JA. Deciphering the sinus tachycardias. Clin Cardiol 2005;28:267-276.

3. Martin DT. Arrhythmias. In: Noble J, Greene HL, eds. Textbook of Primary Care Medicine. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2001:528–537.

4. Stoenescu ML, Kowey PR. Tachycardias. In: Rakel RE, ed. Conn’s Current Therapy. 57th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2005;354-355.

5. Olgin JE, Zipes DP. Specific arrhythmias: diagnosis and treatment. In: Braunwald E, ed. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2005;803-806.

6. Castellanos A, Moleiro F, Chakko S, et al. Heart rate variability in inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:531-534.

7. Krahn AD, yee R, Klein GJ, Morillo C. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia: evaluation and treatment. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1995;6:1124-1128.

The best evidence about the diagnostic evaluation of resting tachycardias in adults is currently outlined by practice guidelines.1 Initial evaluation includes clinical history, physical examination, and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). If the initial evaluation suggests a sinus tachycardia with narrow QRS complexes and no identifiable secondary cause, a 24-hour Holter monitor is usually recommended (strength of recommendation: C, based on expert opinion).

Wide-complex tachycardias and irregular heartbeats should be urgently managed

Laurel Woods, MD

Group Health Family Medicine Residency Program, Seattle, Wash

This Clinical Inquiry organizes a rational approach to tachycardia, which is frequently an incidental and asymptomatic finding on patient intake. The recommendation of evaluating a 12-lead ECG for sinus vs non-sinus tachycardia, then further investigating underlying causes, helps frame the workup in an approachable manner. Particularly helpful is the pointer that the wide-complex tachycardias and irregular heartbeats should be urgently managed, whereas the rest can be assessed at a more relaxed pace. For nonurgent cases it is important to keep in mind the differential diagnosis and rationally evaluate the likely causes. In my patient population, I tend to see sinus tachycardias in young healthy patients in whom no secondary cause aside from anxiety is identified. Oftentimes I follow up after initiating treatment for anxiety or its underlying cause and find that the tachycardia has resolved. In these cases, I have been less aggressive about ordering a 24-hour Holter monitor.

Evidence Summary

Heart rate varies by age; however, tachycardia in adults is usually defined as a rate exceeding 100 beats/minute.1 Tachycardia at rest requires a diagnostic evaluation. However, our search found no systematic reviews, randomized trials, or prospective cohort studies relevant to this question. The highest level of evidence we located was an international practice guideline developed by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines.1

This joint guideline recommends that the diagnostic evaluation of a hemodynamically stable patient should begin with a clinical history, physical examination with relevant labs, and 12-lead ECG.1 Many patients with tachycardia are asymptomatic; however, common symptoms and complaints include palpitations, fatigue, lightheadedness, chest discomfort, dyspnea, presyncope, or syncope.1 If the patient has experienced symptoms, it is of crucial importance to obtain a clinical history describing the pattern in terms of the number of episodes, duration, frequency, mode of onset, and possible triggers.1

The main goals of the physical examination, labs, and the 12-lead ECG are to determine if the patient has a sinus or non-sinus tachycardia and to look for other findings that may suggest either a cause for the tachycardia or any complications resulting from the tachycardia.

First, determine if the patient’s heartbeat is regular or irregular. Atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation are common causes of an irregular heartbeat that can easily be diagnosed with a 12-lead ECG. Second, determine the width of the QRS interval: narrow QRS complex tachycardias are supraventricular (from the sinus node, the atria, and the atrioventricular junction) in origin, and wide QRS complex tachycardias are usually ventricular (from all sites below the AV junction).2,3 If an irregular heartbeat or wide-complex tachycardia is detected, appropriate management (including possible urgent referrals) should begin immediately.1 A stable patient with a regular rhythm and a narrow QRS complex can be further investigated at a more relaxed pace.

Refer to the TABLE for a listing of common secondary causes for sinus tachycardia, which should direct lab investigations. If no secondary cause is easily identifiable, a 24-hour monitor is recommended as the next step.

TABLE

Potential secondary causes of resting sinus tachycardia5-7

| Hyperthyroidism |

| Fever |

| Sepsis |

| Anxiety |

| Pheochromocytoma |

| Anemia |

| Hypotension and shock |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Acute coronary ischemia and myocardial infarction |

| Heart failure |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

| Hypoxia exposure to medications, stimulants, or illicit drugs |

| Malignancy |

| Pregnancy |

Recommendations from others

Textbook chapters and other review articles regarding this topic describe a similar initial evaluation and provide further details about interpreting the 12-lead ECG.2-7 The most relevant and recent review article suggests that further investigation of narrow QRS complex tachycardias with a regular rate currently involves 4 diagnostic categories: normal sinus tachycardia (ie, secondary cause can be identified), inappropriate sinus tachycardia (IST), postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and sinus node reentry tachycardia (SNRT).4

If a secondary cause is identified, it should be treated appropriately. If no underlying cause is discovered, a 24-hour Holter monitor is recommended.

Persistent sinus tachycardia (sometimes with nocturnal normalization of heart rate) is diagnosed as IST.4 If the monitor shows paroxysmal episodes of sinus tachycardia, determine if they are triggered by orthostasis and relieved by recumbency (confirm with head upright tilt test) to make the diagnosis of POTS. If it is not POTS, the recordings from the 24-hour Holter monitor help make the diagnosis of SNRT, which consists of sudden, paroxysmal, and usually nonsustained tachycardia.4 The FIGURE shows an algorithm of one common diagnostic strategy for evaluation of tachycardia.2-7

FIGURE

Diagnostic algorithm for evaluating tachycardias4

The best evidence about the diagnostic evaluation of resting tachycardias in adults is currently outlined by practice guidelines.1 Initial evaluation includes clinical history, physical examination, and 12-lead electrocardiogram (ECG). If the initial evaluation suggests a sinus tachycardia with narrow QRS complexes and no identifiable secondary cause, a 24-hour Holter monitor is usually recommended (strength of recommendation: C, based on expert opinion).

Wide-complex tachycardias and irregular heartbeats should be urgently managed

Laurel Woods, MD

Group Health Family Medicine Residency Program, Seattle, Wash

This Clinical Inquiry organizes a rational approach to tachycardia, which is frequently an incidental and asymptomatic finding on patient intake. The recommendation of evaluating a 12-lead ECG for sinus vs non-sinus tachycardia, then further investigating underlying causes, helps frame the workup in an approachable manner. Particularly helpful is the pointer that the wide-complex tachycardias and irregular heartbeats should be urgently managed, whereas the rest can be assessed at a more relaxed pace. For nonurgent cases it is important to keep in mind the differential diagnosis and rationally evaluate the likely causes. In my patient population, I tend to see sinus tachycardias in young healthy patients in whom no secondary cause aside from anxiety is identified. Oftentimes I follow up after initiating treatment for anxiety or its underlying cause and find that the tachycardia has resolved. In these cases, I have been less aggressive about ordering a 24-hour Holter monitor.

Evidence Summary

Heart rate varies by age; however, tachycardia in adults is usually defined as a rate exceeding 100 beats/minute.1 Tachycardia at rest requires a diagnostic evaluation. However, our search found no systematic reviews, randomized trials, or prospective cohort studies relevant to this question. The highest level of evidence we located was an international practice guideline developed by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines.1

This joint guideline recommends that the diagnostic evaluation of a hemodynamically stable patient should begin with a clinical history, physical examination with relevant labs, and 12-lead ECG.1 Many patients with tachycardia are asymptomatic; however, common symptoms and complaints include palpitations, fatigue, lightheadedness, chest discomfort, dyspnea, presyncope, or syncope.1 If the patient has experienced symptoms, it is of crucial importance to obtain a clinical history describing the pattern in terms of the number of episodes, duration, frequency, mode of onset, and possible triggers.1

The main goals of the physical examination, labs, and the 12-lead ECG are to determine if the patient has a sinus or non-sinus tachycardia and to look for other findings that may suggest either a cause for the tachycardia or any complications resulting from the tachycardia.

First, determine if the patient’s heartbeat is regular or irregular. Atrial flutter and atrial fibrillation are common causes of an irregular heartbeat that can easily be diagnosed with a 12-lead ECG. Second, determine the width of the QRS interval: narrow QRS complex tachycardias are supraventricular (from the sinus node, the atria, and the atrioventricular junction) in origin, and wide QRS complex tachycardias are usually ventricular (from all sites below the AV junction).2,3 If an irregular heartbeat or wide-complex tachycardia is detected, appropriate management (including possible urgent referrals) should begin immediately.1 A stable patient with a regular rhythm and a narrow QRS complex can be further investigated at a more relaxed pace.

Refer to the TABLE for a listing of common secondary causes for sinus tachycardia, which should direct lab investigations. If no secondary cause is easily identifiable, a 24-hour monitor is recommended as the next step.

TABLE

Potential secondary causes of resting sinus tachycardia5-7

| Hyperthyroidism |

| Fever |

| Sepsis |

| Anxiety |

| Pheochromocytoma |

| Anemia |

| Hypotension and shock |

| Pulmonary embolism |

| Acute coronary ischemia and myocardial infarction |

| Heart failure |

| Chronic pulmonary disease |

| Hypoxia exposure to medications, stimulants, or illicit drugs |

| Malignancy |

| Pregnancy |

Recommendations from others

Textbook chapters and other review articles regarding this topic describe a similar initial evaluation and provide further details about interpreting the 12-lead ECG.2-7 The most relevant and recent review article suggests that further investigation of narrow QRS complex tachycardias with a regular rate currently involves 4 diagnostic categories: normal sinus tachycardia (ie, secondary cause can be identified), inappropriate sinus tachycardia (IST), postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), and sinus node reentry tachycardia (SNRT).4

If a secondary cause is identified, it should be treated appropriately. If no underlying cause is discovered, a 24-hour Holter monitor is recommended.

Persistent sinus tachycardia (sometimes with nocturnal normalization of heart rate) is diagnosed as IST.4 If the monitor shows paroxysmal episodes of sinus tachycardia, determine if they are triggered by orthostasis and relieved by recumbency (confirm with head upright tilt test) to make the diagnosis of POTS. If it is not POTS, the recordings from the 24-hour Holter monitor help make the diagnosis of SNRT, which consists of sudden, paroxysmal, and usually nonsustained tachycardia.4 The FIGURE shows an algorithm of one common diagnostic strategy for evaluation of tachycardia.2-7

FIGURE

Diagnostic algorithm for evaluating tachycardias4

1. American College of Cardiology/American Heart association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ESC). ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with surpraventricular arrythmias-executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1493-1531.

2. Yusuf S, Camm JA. Deciphering the sinus tachycardias. Clin Cardiol 2005;28:267-276.

3. Martin DT. Arrhythmias. In: Noble J, Greene HL, eds. Textbook of Primary Care Medicine. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2001:528–537.

4. Stoenescu ML, Kowey PR. Tachycardias. In: Rakel RE, ed. Conn’s Current Therapy. 57th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2005;354-355.

5. Olgin JE, Zipes DP. Specific arrhythmias: diagnosis and treatment. In: Braunwald E, ed. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2005;803-806.

6. Castellanos A, Moleiro F, Chakko S, et al. Heart rate variability in inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:531-534.

7. Krahn AD, yee R, Klein GJ, Morillo C. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia: evaluation and treatment. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1995;6:1124-1128.

1. American College of Cardiology/American Heart association Task Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (ACC/AHA/ESC). ACC/AHA/ESC guidelines for the management of patients with surpraventricular arrythmias-executive summary. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:1493-1531.

2. Yusuf S, Camm JA. Deciphering the sinus tachycardias. Clin Cardiol 2005;28:267-276.

3. Martin DT. Arrhythmias. In: Noble J, Greene HL, eds. Textbook of Primary Care Medicine. 3rd ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby; 2001:528–537.

4. Stoenescu ML, Kowey PR. Tachycardias. In: Rakel RE, ed. Conn’s Current Therapy. 57th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2005;354-355.

5. Olgin JE, Zipes DP. Specific arrhythmias: diagnosis and treatment. In: Braunwald E, ed. Braunwald’s Heart Disease: A Textbook of Cardiovascular Medicine. Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders; 2005;803-806.

6. Castellanos A, Moleiro F, Chakko S, et al. Heart rate variability in inappropriate sinus tachycardia. Am J Cardiol 1998;82:531-534.

7. Krahn AD, yee R, Klein GJ, Morillo C. Inappropriate sinus tachycardia: evaluation and treatment. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 1995;6:1124-1128.

Evidence-based answers from the Family Physicians Inquiries Network