User login

CASE A difficult withdrawal

Three days after he stops drinking alcohol, Mr. G, age 49, presents to a detoxification center with his wife, who drove him there because she was concerned about his condition. She says her husband had been drinking alcohol every night for as long as she can remember. Despite numerous admissions to rehabilitation centers, Mr. G usually would resume drinking soon after he was discharged. Three days ago, Mr. G’s wife had told him she “could not take it anymore,” so he got rid of all his alcohol and stopped drinking. Mr. G’s wife felt he was doing fine the first day, but his condition increasingly worsened the second and third days. The triage nurse who attempts to interview Mr. G finds him tremulous, vomiting, and sweating. She notices that he seems preoccupied with pulling at his shirt, appearing to pick at things that are not there.

HISTORY Untreated depression, other comorbidities

Mr. G’s wife says he has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or exhibited suicidal behavior. Mr. G previously received care from a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with major depressive disorder (MDD) and prescribed an antidepressant, though his wife cannot recall which specific medication. She shares it has been “a long time” since Mr. G has taken the antidepressant and the last time he received treatment for his MDD was 5 years ago. Mr. G’s wife says her husband had once abstained from alcohol use for >6 months following one of his stints at a rehabilitation center. She is not able to share many other details about Mr. G’s previous stays at rehabilitation centers, but says he always had “a rough time.”

She says Mr. G had been drinking an average of 10 drinks each night, usually within 4 hours. He has no history of nicotine or illicit substance use and has held a corporate job for the last 18 years. Several years ago, a physician had diagnosed Mr. G with hypertension and high cholesterol, but he did not follow up for treatment. Mr. G’s wife also recalls a physician told her husband he had a fatty liver. His family history includes heart disease and cancer.

[polldaddy:12041618]

The author’s observations

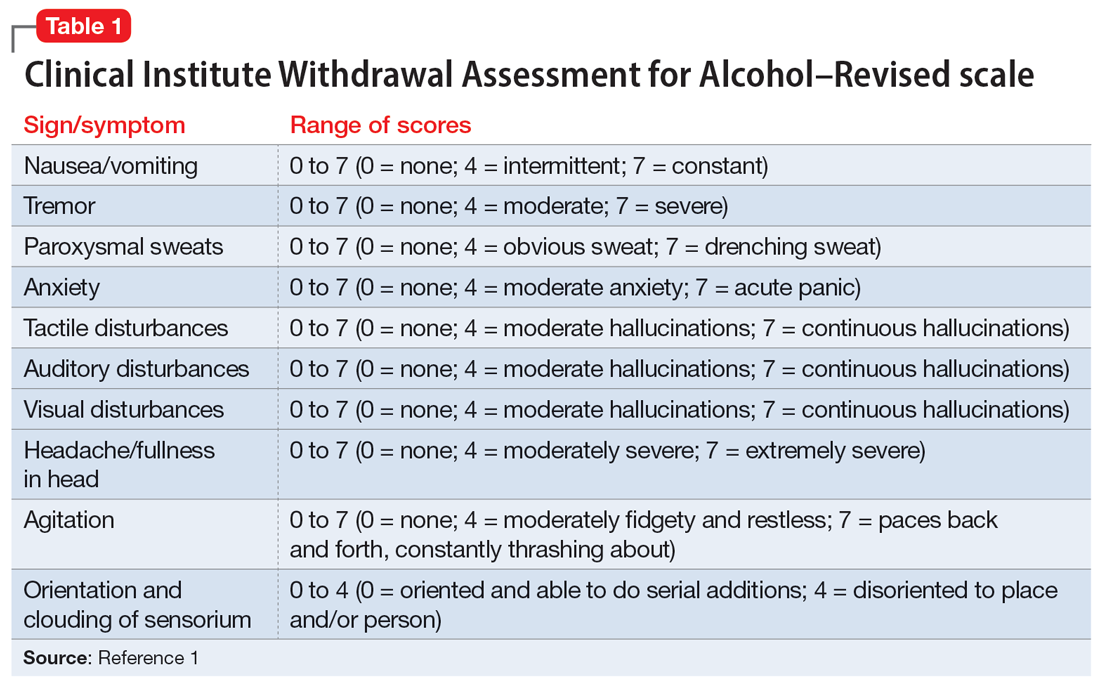

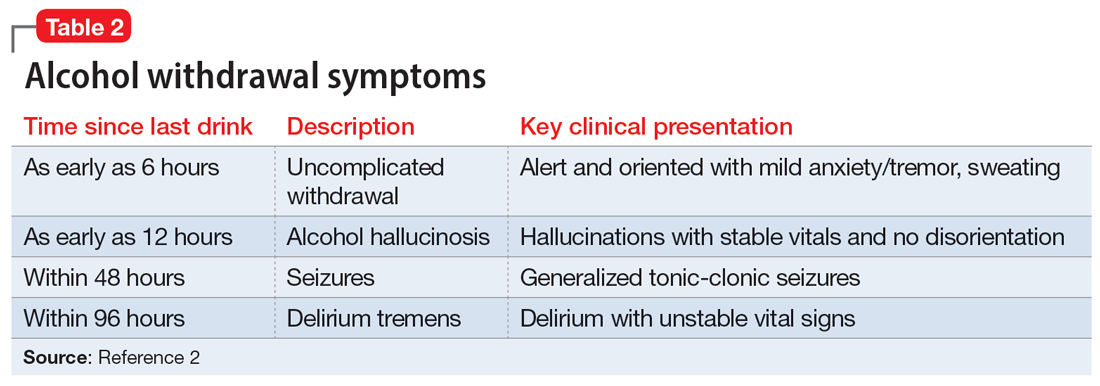

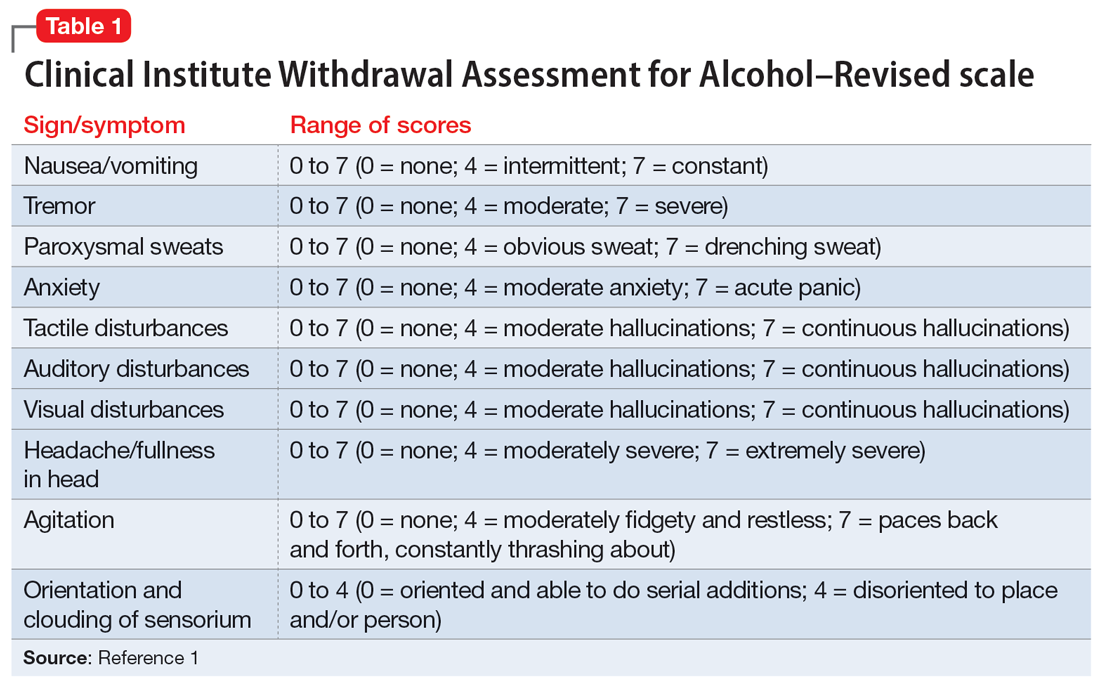

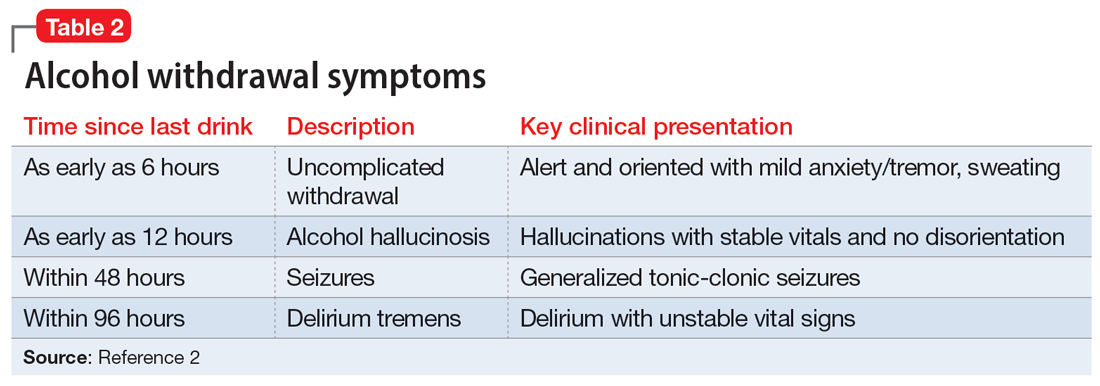

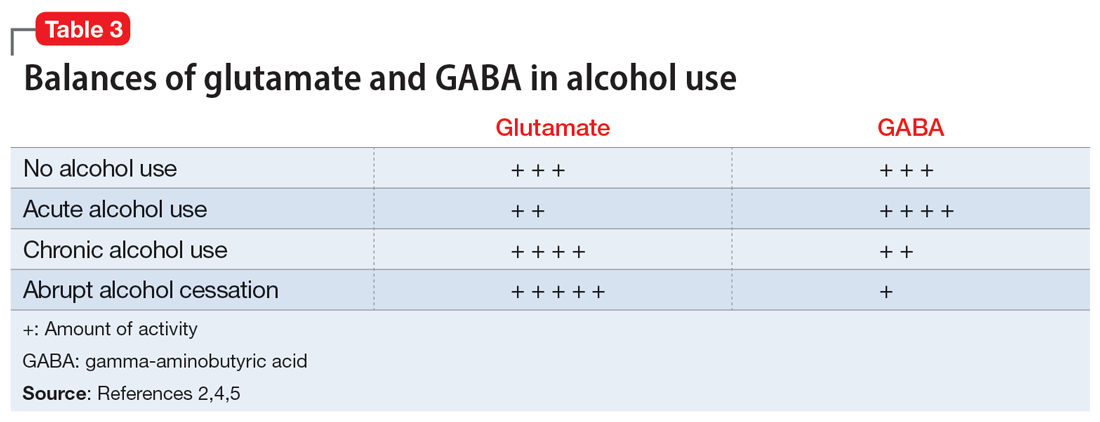

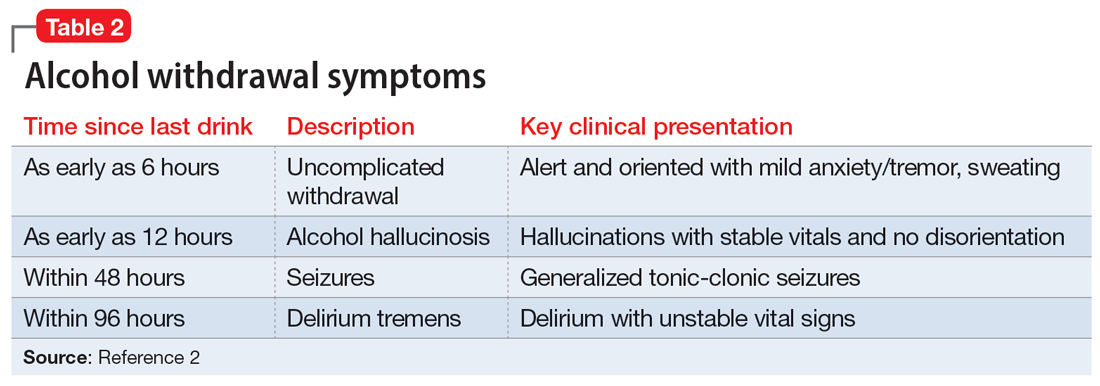

The treatment team observed several elements of alcohol withdrawal and classified Mr. G as a priority patient. If the team had completed the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised scale (CIWA-Ar) (Table 11), Mr. G would score ≥10. While the protocol for initiating treatment for patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal varies by institution, patients with moderate to severe scores on the CIWA-Ar when experiencing withdrawal typically are managed with pharmacotherapy to address their symptoms.1 Given the timeline of his last drink as reported by his wife, Mr. G is on the brink of experiencing a cascade of symptoms concerning for delirium tremens (DTs).2 Table 22 provides a timeline and symptoms related to alcohol withdrawal. To prevent further exacerbation of symptoms, which could lead to DTs, Mr. G’s treatment team will likely initiate a benzodiazepine, using either scheduled or symptom-driven dosing.3

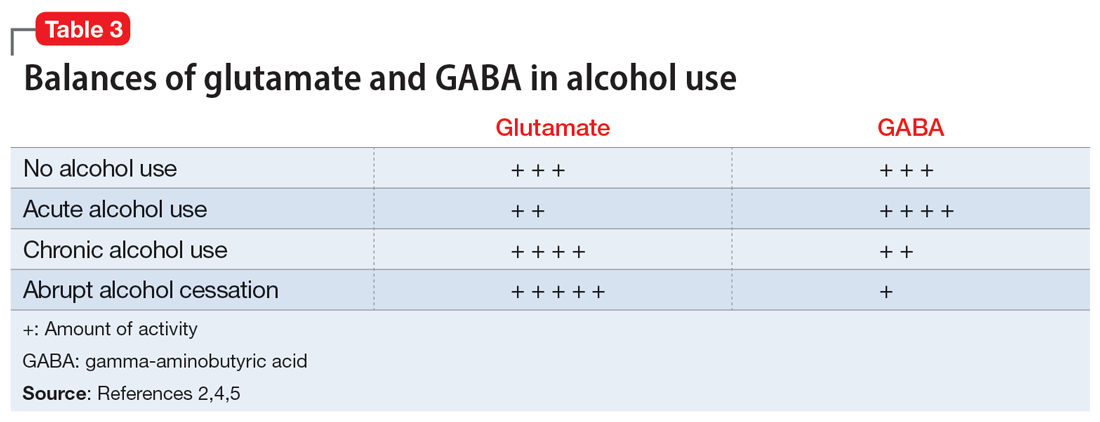

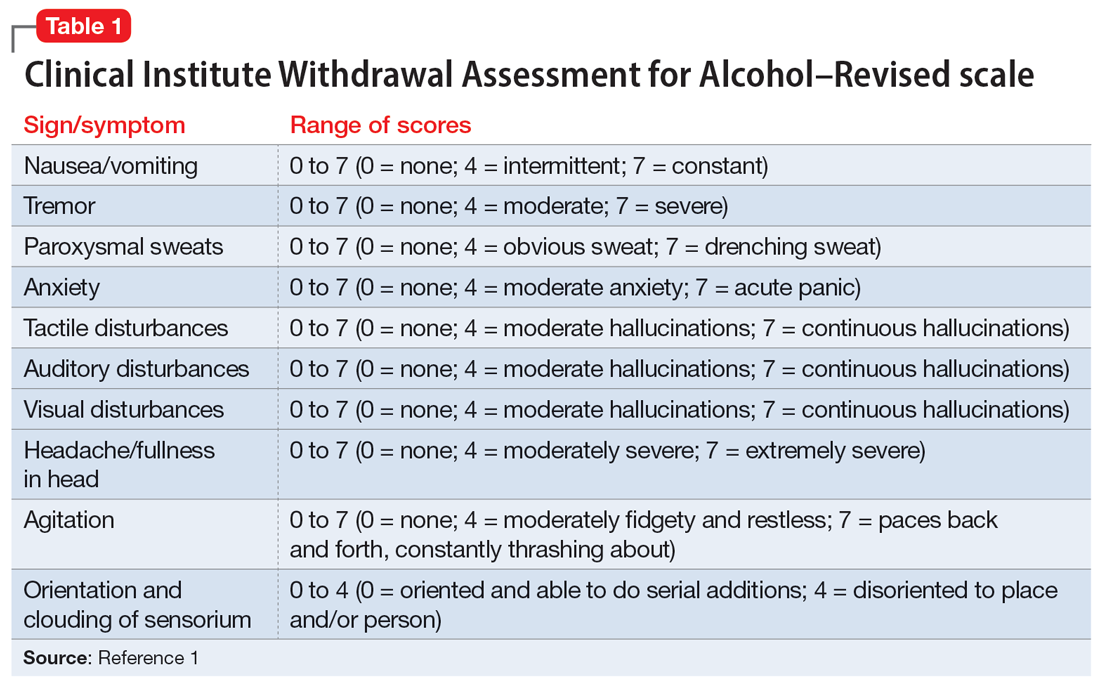

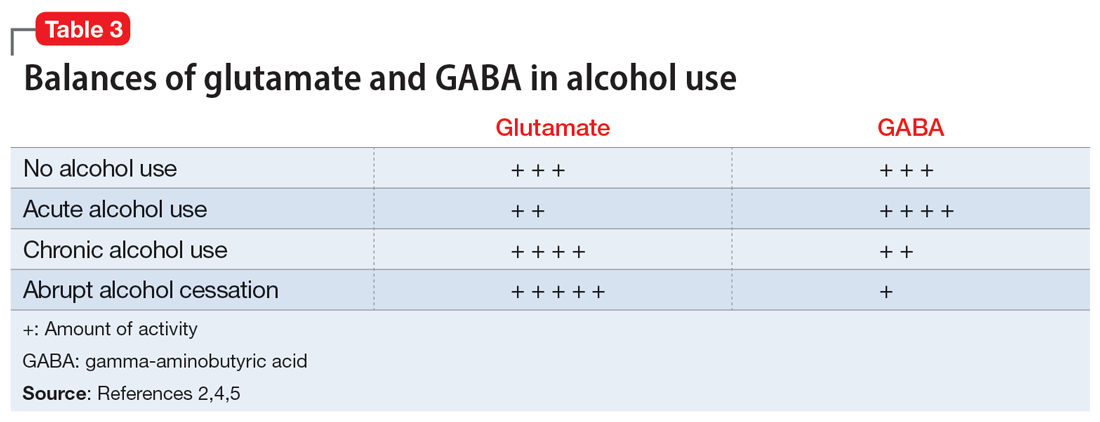

Two neurotransmitters that play a role in DTs are glutamate (excitatory) and GABA (inhibitory). In a normal state, the competing actions of these neurotransmitters balance each other. Acute alcohol intake causes a shift in the excitatory and inhibitory levels, with more inhibition taking place, thus causing disequilibrium. If chronic alcohol use continues, the amount of GABA inhibition reduction is related to downregulation of receptors.2,4 Excitation increases by way of upregulation of the N-methyl-

If alcohol is suddenly removed following chronic use, there is unchecked glutamate excitation related to a blunted GABA state. This added increase in the excitation of glutamate leads to withdrawal symptoms.2,4 Table 32,4,5 depicts the neurotransmitter equilibrium of GABA and glutamate relative to alcohol use.

EVALUATION Bleeding gums and bruising

The treatment team admits Mr. G to the triage bay and contacts the addiction psychiatrist. The physician orders laboratory tests to assess nutritional deficits and electrolyte abnormalities. Mr. G is also placed on routine assessments with symptom-triggered therapy. An assessment reveals bleeding gums and bruises, which are believed to be a result of thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count).

[polldaddy:12041627]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Though regular clinical assessment of PEth varies, it is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity to detect alcohol use.6 When ethanol is present, the phospholipase D enzyme acts upon phosphatidylcholine, forming a direct biomarker, PEth, on the surface of the red blood cell.6,7 PEth’s half-life ranges from 4.5 to 12 days,6 and it can be detected in blood for 3 to 4 weeks after alcohol ingestion.6,7 A PEth value <20 ng/mL indicates light or no alcohol consumption; 20 to 199 ng/mL indicates significant consumption; and >200 ng/mL indicates heavy consumption.7 Since Mr. G has a history of chronic alcohol use, his PEth level is expected to be >200 ng/mL.

AST/ALT and MCV are indirect biomarkers, meaning the tests are not alcohol-specific and the role of alcohol is instead observed by the damage to the body with excessive use over time.7 The expected AST:ALT ratio is 2:1. This is related to 3 mechanisms. The first is a decrease in ALT usually relative to B6 deficiency in individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Another mechanism is related to alcohol’s propensity to affect mitochondria, which is a source for AST. Additionally, AST is also found in higher proportions in the kidneys, heart, and muscles.8

An MCV <100 fL would be within the normal range (80 to 100 fL) for red blood cells. While the reasons for an enlarged red blood cell (or macrocyte) are extensive, alcohol can be a factor once other causes are excluded. Additional laboratory tests and a peripheral blood smear test can help in this investigation. Alcohol disrupts the complete maturation of red blood cells.9,10 If the cause of the macrocyte is alcohol-related and alcohol use is terminated, those enlarged cells can resolve in an average of 3 months.9

Vitamin B1 levels >200 nmol/L would be within normal range (74 to 222 nmol/L). Mr. G’s chronic alcohol use would likely cause him to be vitamin B1–deficient. The deficiency is usually related to diet, malabsorption, and the cells’ impaired ability to utilize vitamin B1. A consequence of vitamin B1 deficiency is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.11

Due to his chronic alcohol use, Mr. G’s magnesium stores most likely would be below normal range (1.7 to 2.2 mg/dL). Acting as a diuretic, alcohol depletes magnesium and other electrolytes. The intracellular shift that occurs to balance the deficit causes the body to use its normal stores of magnesium, which leads to further magnesium depletion. Other common causes include nutritional deficiency and decreased gastrointestinal absorption.12 The bleeding the physician suspected was a result of drinking likely occurred through direct and indirect mechanisms that affect platelets.9,13 Platelets can show improvement 1 week after drinking cessation. Some evidence suggests the risk of seizure or DTs increases significantly with a platelet count <119,000 µL per unit of blood.13

Continue to: TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

As Mr. G’s condition starts to stabilize, he discusses treatment options for AUD with his physician. At the end of the discussion, Mr. G expresses an interest in starting a medication. The doctor reviews his laboratory results and available treatment options.

[polldaddy:12041630]

The author’s observations

Of the 3 FDA-approved medications for treating AUD (disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone), naltrexone has been shown to decrease heavy drinking days5,14 and comes in oral and injectable forms. Reducing drinking is achieved by reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol5,14 and alcohol cravings.5 Disulfiram often has poor adherence, and like acamprosate it may be more helpful for maintenance of abstinence. Neither topiramate nor gabapentin are FDA-approved for AUD but may be used for their affects on GABA.5 Gabapentin may also help patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal syndrome.5,15 Mr. G did not have any concomitant medications or comorbid medical conditions, but these factors as well as any renal or hepatic dysfunction must be considered before initiating any medications.

OUTCOME Improved well-being

Mr. G’s treatment team initiates oral naltrexone 50 mg/d, which he tolerates well without complications. He stops drinking entirely and expresses an interest in transitioning to an injectable form of naltrexone in the future. In addition to taking medication, Mr. G wants to participate in psychotherapy. Mr. G thanks his team for the care he received in the hospital, telling them, “You all saved my life.” As he discusses his past issues with alcohol, Mr. G asks his physician how he could get involved to make changes to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community (Box5,15-21).

Box

Alcohol use disorder is undertreated5,15-17 and excessive alcohol use accounts for 1 in 5 deaths in individuals within Mr. G’s age range.18 An April 2011 report from the Community Preventive Services Task Force19 did not recommend privatization of retail alcohol sales as an intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption, because it would instead lead to an increase in alcohol consumption per capita, a known gateway to excessive alcohol consumption.20

The Task Force was established in 1996 by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Its objective is to identify scientifically proven interventions to save lives, increase lifespans, and improve quality of life. Recommendations are based on systematic reviews to inform lawmakers, health departments, and other organizations and agencies.21 The Task Force’s recommendations were divided into interventions that have strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence. If Mr. G wanted to have the greatest impact in his efforts to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community, the strongest evidence supporting change focuses on electronic screening and brief intervention, maintaining limits on days of alcohol sale, increasing taxes on alcohol, and establishing dram shop liability (laws that hold retail establishments that sell alcohol liable for the injuries or harms caused by their intoxicated or underage customers).19

Bottom Line

Patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal can present with several layers of complexity. Failure to achieve acute stabilization may be life-threatening. After providing critical care, promptly start alcohol use disorder treatment for patients who expresses a desire to change.

Related Resources

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone (injection) • Vivitrol

Naltrexone (oral) • ReVia

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakis IL, et al. Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22(1):61-66.

3. Holleck JL, Merchant N, Gunderson CG. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):1018-1024.

4. Clapp P, Bhave SV, Hoffman PL. How adaptation of the brain to alcohol leads to dependence: a pharmacological perspective. Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(4):310-339.

5. Burnette EM, Nieto SJ, Grodin EN, et al. Novel agents for the pharmacological treatment of alcohol use disorder. Drugs. 2022;82(3):251-274.

6. Selim R, Zhou Y, Rupp LB, et al. Availability of PEth testing is associated with reduced eligibility for liver transplant among patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(5):e14595.

7. Ulwelling W, Smith K. The PEth blood test in the security environment: what it is; why it is important; and interpretative guidelines. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63(6):1634-1640.

8. Botros M, Sikaris KA. The de ritis ratio: the test of time. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34(3):117-130.

9. Ballard HS. The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21(1):42-52.

10. Kaferle J, Strzoda CE. Evaluation of macrocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(3):203-208.

11. Martin PR, Singleton CK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(2):134-142.

12. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Electrolyte disturbances in patients with chronic alcohol-use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1368-1377.

13. Silczuk A, Habrat B. Alcohol-induced thrombocytopenia: current review. Alcohol. 2020;86:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.02.166

14. Pettinati HM, Rabinowitz AR. New pharmacotherapies for treating the neurobiology of alcohol and drug addiction. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(5):14-16.

15. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736.

16. Chockalingam L, Burnham EL, Jolley SE. Medication prescribing for alcohol use disorders during alcohol-related encounters in a Colorado regional healthcare system. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(6):1094-1102.

17. Mintz CM, Hartz SM, Fisher SL, et al. A cascade of care for alcohol use disorder: using 2015-2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data to identify gaps in past 12-month care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45(6):1276-1286.

18. Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among US adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2239485. doi:10.1001/jamanet workopen.2022.39485

19. The Community Guide. CPSTF Findings for Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/task-force-findings-excessive-alcohol-consumption.html

20. The Community Guide. Alcohol Excessive Consumption: Privatization of Retail Alcohol Sales. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-privatization-retail-alcohol-sales.html

21. The Community Guide. What is the CPSTF? Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/what-is-the-cpstf.html

CASE A difficult withdrawal

Three days after he stops drinking alcohol, Mr. G, age 49, presents to a detoxification center with his wife, who drove him there because she was concerned about his condition. She says her husband had been drinking alcohol every night for as long as she can remember. Despite numerous admissions to rehabilitation centers, Mr. G usually would resume drinking soon after he was discharged. Three days ago, Mr. G’s wife had told him she “could not take it anymore,” so he got rid of all his alcohol and stopped drinking. Mr. G’s wife felt he was doing fine the first day, but his condition increasingly worsened the second and third days. The triage nurse who attempts to interview Mr. G finds him tremulous, vomiting, and sweating. She notices that he seems preoccupied with pulling at his shirt, appearing to pick at things that are not there.

HISTORY Untreated depression, other comorbidities

Mr. G’s wife says he has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or exhibited suicidal behavior. Mr. G previously received care from a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with major depressive disorder (MDD) and prescribed an antidepressant, though his wife cannot recall which specific medication. She shares it has been “a long time” since Mr. G has taken the antidepressant and the last time he received treatment for his MDD was 5 years ago. Mr. G’s wife says her husband had once abstained from alcohol use for >6 months following one of his stints at a rehabilitation center. She is not able to share many other details about Mr. G’s previous stays at rehabilitation centers, but says he always had “a rough time.”

She says Mr. G had been drinking an average of 10 drinks each night, usually within 4 hours. He has no history of nicotine or illicit substance use and has held a corporate job for the last 18 years. Several years ago, a physician had diagnosed Mr. G with hypertension and high cholesterol, but he did not follow up for treatment. Mr. G’s wife also recalls a physician told her husband he had a fatty liver. His family history includes heart disease and cancer.

[polldaddy:12041618]

The author’s observations

The treatment team observed several elements of alcohol withdrawal and classified Mr. G as a priority patient. If the team had completed the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised scale (CIWA-Ar) (Table 11), Mr. G would score ≥10. While the protocol for initiating treatment for patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal varies by institution, patients with moderate to severe scores on the CIWA-Ar when experiencing withdrawal typically are managed with pharmacotherapy to address their symptoms.1 Given the timeline of his last drink as reported by his wife, Mr. G is on the brink of experiencing a cascade of symptoms concerning for delirium tremens (DTs).2 Table 22 provides a timeline and symptoms related to alcohol withdrawal. To prevent further exacerbation of symptoms, which could lead to DTs, Mr. G’s treatment team will likely initiate a benzodiazepine, using either scheduled or symptom-driven dosing.3

Two neurotransmitters that play a role in DTs are glutamate (excitatory) and GABA (inhibitory). In a normal state, the competing actions of these neurotransmitters balance each other. Acute alcohol intake causes a shift in the excitatory and inhibitory levels, with more inhibition taking place, thus causing disequilibrium. If chronic alcohol use continues, the amount of GABA inhibition reduction is related to downregulation of receptors.2,4 Excitation increases by way of upregulation of the N-methyl-

If alcohol is suddenly removed following chronic use, there is unchecked glutamate excitation related to a blunted GABA state. This added increase in the excitation of glutamate leads to withdrawal symptoms.2,4 Table 32,4,5 depicts the neurotransmitter equilibrium of GABA and glutamate relative to alcohol use.

EVALUATION Bleeding gums and bruising

The treatment team admits Mr. G to the triage bay and contacts the addiction psychiatrist. The physician orders laboratory tests to assess nutritional deficits and electrolyte abnormalities. Mr. G is also placed on routine assessments with symptom-triggered therapy. An assessment reveals bleeding gums and bruises, which are believed to be a result of thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count).

[polldaddy:12041627]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Though regular clinical assessment of PEth varies, it is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity to detect alcohol use.6 When ethanol is present, the phospholipase D enzyme acts upon phosphatidylcholine, forming a direct biomarker, PEth, on the surface of the red blood cell.6,7 PEth’s half-life ranges from 4.5 to 12 days,6 and it can be detected in blood for 3 to 4 weeks after alcohol ingestion.6,7 A PEth value <20 ng/mL indicates light or no alcohol consumption; 20 to 199 ng/mL indicates significant consumption; and >200 ng/mL indicates heavy consumption.7 Since Mr. G has a history of chronic alcohol use, his PEth level is expected to be >200 ng/mL.

AST/ALT and MCV are indirect biomarkers, meaning the tests are not alcohol-specific and the role of alcohol is instead observed by the damage to the body with excessive use over time.7 The expected AST:ALT ratio is 2:1. This is related to 3 mechanisms. The first is a decrease in ALT usually relative to B6 deficiency in individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Another mechanism is related to alcohol’s propensity to affect mitochondria, which is a source for AST. Additionally, AST is also found in higher proportions in the kidneys, heart, and muscles.8

An MCV <100 fL would be within the normal range (80 to 100 fL) for red blood cells. While the reasons for an enlarged red blood cell (or macrocyte) are extensive, alcohol can be a factor once other causes are excluded. Additional laboratory tests and a peripheral blood smear test can help in this investigation. Alcohol disrupts the complete maturation of red blood cells.9,10 If the cause of the macrocyte is alcohol-related and alcohol use is terminated, those enlarged cells can resolve in an average of 3 months.9

Vitamin B1 levels >200 nmol/L would be within normal range (74 to 222 nmol/L). Mr. G’s chronic alcohol use would likely cause him to be vitamin B1–deficient. The deficiency is usually related to diet, malabsorption, and the cells’ impaired ability to utilize vitamin B1. A consequence of vitamin B1 deficiency is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.11

Due to his chronic alcohol use, Mr. G’s magnesium stores most likely would be below normal range (1.7 to 2.2 mg/dL). Acting as a diuretic, alcohol depletes magnesium and other electrolytes. The intracellular shift that occurs to balance the deficit causes the body to use its normal stores of magnesium, which leads to further magnesium depletion. Other common causes include nutritional deficiency and decreased gastrointestinal absorption.12 The bleeding the physician suspected was a result of drinking likely occurred through direct and indirect mechanisms that affect platelets.9,13 Platelets can show improvement 1 week after drinking cessation. Some evidence suggests the risk of seizure or DTs increases significantly with a platelet count <119,000 µL per unit of blood.13

Continue to: TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

As Mr. G’s condition starts to stabilize, he discusses treatment options for AUD with his physician. At the end of the discussion, Mr. G expresses an interest in starting a medication. The doctor reviews his laboratory results and available treatment options.

[polldaddy:12041630]

The author’s observations

Of the 3 FDA-approved medications for treating AUD (disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone), naltrexone has been shown to decrease heavy drinking days5,14 and comes in oral and injectable forms. Reducing drinking is achieved by reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol5,14 and alcohol cravings.5 Disulfiram often has poor adherence, and like acamprosate it may be more helpful for maintenance of abstinence. Neither topiramate nor gabapentin are FDA-approved for AUD but may be used for their affects on GABA.5 Gabapentin may also help patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal syndrome.5,15 Mr. G did not have any concomitant medications or comorbid medical conditions, but these factors as well as any renal or hepatic dysfunction must be considered before initiating any medications.

OUTCOME Improved well-being

Mr. G’s treatment team initiates oral naltrexone 50 mg/d, which he tolerates well without complications. He stops drinking entirely and expresses an interest in transitioning to an injectable form of naltrexone in the future. In addition to taking medication, Mr. G wants to participate in psychotherapy. Mr. G thanks his team for the care he received in the hospital, telling them, “You all saved my life.” As he discusses his past issues with alcohol, Mr. G asks his physician how he could get involved to make changes to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community (Box5,15-21).

Box

Alcohol use disorder is undertreated5,15-17 and excessive alcohol use accounts for 1 in 5 deaths in individuals within Mr. G’s age range.18 An April 2011 report from the Community Preventive Services Task Force19 did not recommend privatization of retail alcohol sales as an intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption, because it would instead lead to an increase in alcohol consumption per capita, a known gateway to excessive alcohol consumption.20

The Task Force was established in 1996 by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Its objective is to identify scientifically proven interventions to save lives, increase lifespans, and improve quality of life. Recommendations are based on systematic reviews to inform lawmakers, health departments, and other organizations and agencies.21 The Task Force’s recommendations were divided into interventions that have strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence. If Mr. G wanted to have the greatest impact in his efforts to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community, the strongest evidence supporting change focuses on electronic screening and brief intervention, maintaining limits on days of alcohol sale, increasing taxes on alcohol, and establishing dram shop liability (laws that hold retail establishments that sell alcohol liable for the injuries or harms caused by their intoxicated or underage customers).19

Bottom Line

Patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal can present with several layers of complexity. Failure to achieve acute stabilization may be life-threatening. After providing critical care, promptly start alcohol use disorder treatment for patients who expresses a desire to change.

Related Resources

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone (injection) • Vivitrol

Naltrexone (oral) • ReVia

Topiramate • Topamax

CASE A difficult withdrawal

Three days after he stops drinking alcohol, Mr. G, age 49, presents to a detoxification center with his wife, who drove him there because she was concerned about his condition. She says her husband had been drinking alcohol every night for as long as she can remember. Despite numerous admissions to rehabilitation centers, Mr. G usually would resume drinking soon after he was discharged. Three days ago, Mr. G’s wife had told him she “could not take it anymore,” so he got rid of all his alcohol and stopped drinking. Mr. G’s wife felt he was doing fine the first day, but his condition increasingly worsened the second and third days. The triage nurse who attempts to interview Mr. G finds him tremulous, vomiting, and sweating. She notices that he seems preoccupied with pulling at his shirt, appearing to pick at things that are not there.

HISTORY Untreated depression, other comorbidities

Mr. G’s wife says he has never been psychiatrically hospitalized or exhibited suicidal behavior. Mr. G previously received care from a psychiatrist, who diagnosed him with major depressive disorder (MDD) and prescribed an antidepressant, though his wife cannot recall which specific medication. She shares it has been “a long time” since Mr. G has taken the antidepressant and the last time he received treatment for his MDD was 5 years ago. Mr. G’s wife says her husband had once abstained from alcohol use for >6 months following one of his stints at a rehabilitation center. She is not able to share many other details about Mr. G’s previous stays at rehabilitation centers, but says he always had “a rough time.”

She says Mr. G had been drinking an average of 10 drinks each night, usually within 4 hours. He has no history of nicotine or illicit substance use and has held a corporate job for the last 18 years. Several years ago, a physician had diagnosed Mr. G with hypertension and high cholesterol, but he did not follow up for treatment. Mr. G’s wife also recalls a physician told her husband he had a fatty liver. His family history includes heart disease and cancer.

[polldaddy:12041618]

The author’s observations

The treatment team observed several elements of alcohol withdrawal and classified Mr. G as a priority patient. If the team had completed the Clinical Institute Withdrawal Assessment for Alcohol–Revised scale (CIWA-Ar) (Table 11), Mr. G would score ≥10. While the protocol for initiating treatment for patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal varies by institution, patients with moderate to severe scores on the CIWA-Ar when experiencing withdrawal typically are managed with pharmacotherapy to address their symptoms.1 Given the timeline of his last drink as reported by his wife, Mr. G is on the brink of experiencing a cascade of symptoms concerning for delirium tremens (DTs).2 Table 22 provides a timeline and symptoms related to alcohol withdrawal. To prevent further exacerbation of symptoms, which could lead to DTs, Mr. G’s treatment team will likely initiate a benzodiazepine, using either scheduled or symptom-driven dosing.3

Two neurotransmitters that play a role in DTs are glutamate (excitatory) and GABA (inhibitory). In a normal state, the competing actions of these neurotransmitters balance each other. Acute alcohol intake causes a shift in the excitatory and inhibitory levels, with more inhibition taking place, thus causing disequilibrium. If chronic alcohol use continues, the amount of GABA inhibition reduction is related to downregulation of receptors.2,4 Excitation increases by way of upregulation of the N-methyl-

If alcohol is suddenly removed following chronic use, there is unchecked glutamate excitation related to a blunted GABA state. This added increase in the excitation of glutamate leads to withdrawal symptoms.2,4 Table 32,4,5 depicts the neurotransmitter equilibrium of GABA and glutamate relative to alcohol use.

EVALUATION Bleeding gums and bruising

The treatment team admits Mr. G to the triage bay and contacts the addiction psychiatrist. The physician orders laboratory tests to assess nutritional deficits and electrolyte abnormalities. Mr. G is also placed on routine assessments with symptom-triggered therapy. An assessment reveals bleeding gums and bruises, which are believed to be a result of thrombocytopenia (low blood platelet count).

[polldaddy:12041627]

Continue to: The author's observations

The author’s observations

Though regular clinical assessment of PEth varies, it is considered to have high sensitivity and specificity to detect alcohol use.6 When ethanol is present, the phospholipase D enzyme acts upon phosphatidylcholine, forming a direct biomarker, PEth, on the surface of the red blood cell.6,7 PEth’s half-life ranges from 4.5 to 12 days,6 and it can be detected in blood for 3 to 4 weeks after alcohol ingestion.6,7 A PEth value <20 ng/mL indicates light or no alcohol consumption; 20 to 199 ng/mL indicates significant consumption; and >200 ng/mL indicates heavy consumption.7 Since Mr. G has a history of chronic alcohol use, his PEth level is expected to be >200 ng/mL.

AST/ALT and MCV are indirect biomarkers, meaning the tests are not alcohol-specific and the role of alcohol is instead observed by the damage to the body with excessive use over time.7 The expected AST:ALT ratio is 2:1. This is related to 3 mechanisms. The first is a decrease in ALT usually relative to B6 deficiency in individuals with alcohol use disorder (AUD). Another mechanism is related to alcohol’s propensity to affect mitochondria, which is a source for AST. Additionally, AST is also found in higher proportions in the kidneys, heart, and muscles.8

An MCV <100 fL would be within the normal range (80 to 100 fL) for red blood cells. While the reasons for an enlarged red blood cell (or macrocyte) are extensive, alcohol can be a factor once other causes are excluded. Additional laboratory tests and a peripheral blood smear test can help in this investigation. Alcohol disrupts the complete maturation of red blood cells.9,10 If the cause of the macrocyte is alcohol-related and alcohol use is terminated, those enlarged cells can resolve in an average of 3 months.9

Vitamin B1 levels >200 nmol/L would be within normal range (74 to 222 nmol/L). Mr. G’s chronic alcohol use would likely cause him to be vitamin B1–deficient. The deficiency is usually related to diet, malabsorption, and the cells’ impaired ability to utilize vitamin B1. A consequence of vitamin B1 deficiency is Wernicke-Korsakoff syndrome.11

Due to his chronic alcohol use, Mr. G’s magnesium stores most likely would be below normal range (1.7 to 2.2 mg/dL). Acting as a diuretic, alcohol depletes magnesium and other electrolytes. The intracellular shift that occurs to balance the deficit causes the body to use its normal stores of magnesium, which leads to further magnesium depletion. Other common causes include nutritional deficiency and decreased gastrointestinal absorption.12 The bleeding the physician suspected was a result of drinking likely occurred through direct and indirect mechanisms that affect platelets.9,13 Platelets can show improvement 1 week after drinking cessation. Some evidence suggests the risk of seizure or DTs increases significantly with a platelet count <119,000 µL per unit of blood.13

Continue to: TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

TREATMENT Pharmacotherapy for alcohol use disorder

As Mr. G’s condition starts to stabilize, he discusses treatment options for AUD with his physician. At the end of the discussion, Mr. G expresses an interest in starting a medication. The doctor reviews his laboratory results and available treatment options.

[polldaddy:12041630]

The author’s observations

Of the 3 FDA-approved medications for treating AUD (disulfiram, acamprosate, and naltrexone), naltrexone has been shown to decrease heavy drinking days5,14 and comes in oral and injectable forms. Reducing drinking is achieved by reducing the rewarding effects of alcohol5,14 and alcohol cravings.5 Disulfiram often has poor adherence, and like acamprosate it may be more helpful for maintenance of abstinence. Neither topiramate nor gabapentin are FDA-approved for AUD but may be used for their affects on GABA.5 Gabapentin may also help patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal syndrome.5,15 Mr. G did not have any concomitant medications or comorbid medical conditions, but these factors as well as any renal or hepatic dysfunction must be considered before initiating any medications.

OUTCOME Improved well-being

Mr. G’s treatment team initiates oral naltrexone 50 mg/d, which he tolerates well without complications. He stops drinking entirely and expresses an interest in transitioning to an injectable form of naltrexone in the future. In addition to taking medication, Mr. G wants to participate in psychotherapy. Mr. G thanks his team for the care he received in the hospital, telling them, “You all saved my life.” As he discusses his past issues with alcohol, Mr. G asks his physician how he could get involved to make changes to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community (Box5,15-21).

Box

Alcohol use disorder is undertreated5,15-17 and excessive alcohol use accounts for 1 in 5 deaths in individuals within Mr. G’s age range.18 An April 2011 report from the Community Preventive Services Task Force19 did not recommend privatization of retail alcohol sales as an intervention to reduce excessive alcohol consumption, because it would instead lead to an increase in alcohol consumption per capita, a known gateway to excessive alcohol consumption.20

The Task Force was established in 1996 by the US Department of Health and Human Services. Its objective is to identify scientifically proven interventions to save lives, increase lifespans, and improve quality of life. Recommendations are based on systematic reviews to inform lawmakers, health departments, and other organizations and agencies.21 The Task Force’s recommendations were divided into interventions that have strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence. If Mr. G wanted to have the greatest impact in his efforts to reduce excessive alcohol consumption in his community, the strongest evidence supporting change focuses on electronic screening and brief intervention, maintaining limits on days of alcohol sale, increasing taxes on alcohol, and establishing dram shop liability (laws that hold retail establishments that sell alcohol liable for the injuries or harms caused by their intoxicated or underage customers).19

Bottom Line

Patients experiencing alcohol withdrawal can present with several layers of complexity. Failure to achieve acute stabilization may be life-threatening. After providing critical care, promptly start alcohol use disorder treatment for patients who expresses a desire to change.

Related Resources

- American Society of Addiction Medicine. The ASAM Clinical Practice Guideline on Alcohol Withdrawal Management. https://www.asam.org/quality-care/clinical-guidelines/alcohol-withdrawal-management-guideline

- American Psychiatric Association. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the Pharmacological Treatment of Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2018.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Naltrexone (injection) • Vivitrol

Naltrexone (oral) • ReVia

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakis IL, et al. Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22(1):61-66.

3. Holleck JL, Merchant N, Gunderson CG. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):1018-1024.

4. Clapp P, Bhave SV, Hoffman PL. How adaptation of the brain to alcohol leads to dependence: a pharmacological perspective. Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(4):310-339.

5. Burnette EM, Nieto SJ, Grodin EN, et al. Novel agents for the pharmacological treatment of alcohol use disorder. Drugs. 2022;82(3):251-274.

6. Selim R, Zhou Y, Rupp LB, et al. Availability of PEth testing is associated with reduced eligibility for liver transplant among patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(5):e14595.

7. Ulwelling W, Smith K. The PEth blood test in the security environment: what it is; why it is important; and interpretative guidelines. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63(6):1634-1640.

8. Botros M, Sikaris KA. The de ritis ratio: the test of time. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34(3):117-130.

9. Ballard HS. The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21(1):42-52.

10. Kaferle J, Strzoda CE. Evaluation of macrocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(3):203-208.

11. Martin PR, Singleton CK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(2):134-142.

12. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Electrolyte disturbances in patients with chronic alcohol-use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1368-1377.

13. Silczuk A, Habrat B. Alcohol-induced thrombocytopenia: current review. Alcohol. 2020;86:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.02.166

14. Pettinati HM, Rabinowitz AR. New pharmacotherapies for treating the neurobiology of alcohol and drug addiction. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(5):14-16.

15. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736.

16. Chockalingam L, Burnham EL, Jolley SE. Medication prescribing for alcohol use disorders during alcohol-related encounters in a Colorado regional healthcare system. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(6):1094-1102.

17. Mintz CM, Hartz SM, Fisher SL, et al. A cascade of care for alcohol use disorder: using 2015-2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data to identify gaps in past 12-month care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45(6):1276-1286.

18. Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among US adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2239485. doi:10.1001/jamanet workopen.2022.39485

19. The Community Guide. CPSTF Findings for Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/task-force-findings-excessive-alcohol-consumption.html

20. The Community Guide. Alcohol Excessive Consumption: Privatization of Retail Alcohol Sales. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-privatization-retail-alcohol-sales.html

21. The Community Guide. What is the CPSTF? Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/what-is-the-cpstf.html

1. Sullivan JT, Sykora K, Schneiderman J, et al. Assessment of alcohol withdrawal: the revised clinical institute withdrawal assessment for alcohol scale (CIWA-Ar). Br J Addict. 1989;84(11):1353-1357.

2. Trevisan LA, Boutros N, Petrakis IL, et al. Complications of alcohol withdrawal: pathophysiological insights. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22(1):61-66.

3. Holleck JL, Merchant N, Gunderson CG. Symptom-triggered therapy for alcohol withdrawal syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(6):1018-1024.

4. Clapp P, Bhave SV, Hoffman PL. How adaptation of the brain to alcohol leads to dependence: a pharmacological perspective. Alcohol Res Health. 2008;31(4):310-339.

5. Burnette EM, Nieto SJ, Grodin EN, et al. Novel agents for the pharmacological treatment of alcohol use disorder. Drugs. 2022;82(3):251-274.

6. Selim R, Zhou Y, Rupp LB, et al. Availability of PEth testing is associated with reduced eligibility for liver transplant among patients with alcohol-related liver disease. Clin Transplant. 2022;36(5):e14595.

7. Ulwelling W, Smith K. The PEth blood test in the security environment: what it is; why it is important; and interpretative guidelines. J Forensic Sci. 2018;63(6):1634-1640.

8. Botros M, Sikaris KA. The de ritis ratio: the test of time. Clin Biochem Rev. 2013;34(3):117-130.

9. Ballard HS. The hematological complications of alcoholism. Alcohol Health Res World. 1997;21(1):42-52.

10. Kaferle J, Strzoda CE. Evaluation of macrocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 2009;79(3):203-208.

11. Martin PR, Singleton CK, Hiller-Sturmhöfel S. The role of thiamine deficiency in alcoholic brain disease. Alcohol Res Health. 2003;27(2):134-142.

12. Palmer BF, Clegg DJ. Electrolyte disturbances in patients with chronic alcohol-use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(14):1368-1377.

13. Silczuk A, Habrat B. Alcohol-induced thrombocytopenia: current review. Alcohol. 2020;86:9-16. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2020.02.166

14. Pettinati HM, Rabinowitz AR. New pharmacotherapies for treating the neurobiology of alcohol and drug addiction. Psychiatry (Edgmont). 2006;3(5):14-16.

15. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736.

16. Chockalingam L, Burnham EL, Jolley SE. Medication prescribing for alcohol use disorders during alcohol-related encounters in a Colorado regional healthcare system. Alcoholism Clin Exp Res. 2022;46(6):1094-1102.

17. Mintz CM, Hartz SM, Fisher SL, et al. A cascade of care for alcohol use disorder: using 2015-2019 National Survey on Drug Use and Health data to identify gaps in past 12-month care. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2021;45(6):1276-1286.

18. Esser MB, Leung G, Sherk A, et al. Estimated deaths attributable to excessive alcohol use among US adults aged 20 to 64 years, 2015 to 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(11):e2239485. doi:10.1001/jamanet workopen.2022.39485

19. The Community Guide. CPSTF Findings for Excessive Alcohol Consumption. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/task-force-findings-excessive-alcohol-consumption.html

20. The Community Guide. Alcohol Excessive Consumption: Privatization of Retail Alcohol Sales. Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/findings/alcohol-excessive-consumption-privatization-retail-alcohol-sales.html

21. The Community Guide. What is the CPSTF? Updated June 27, 2022. Accessed December 1, 2022. https://www.thecommunityguide.org/pages/what-is-the-cpstf.html