User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Ending a physician/patient relationship

HIV: How to provide compassionate care

The prevalence of HIV in persons with untreated psychiatric illness may be 10 to 20 times that of the general population.1 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended HIV screening of all persons age 15 to 65 because 20% to 25% of individuals with HIV infection are unaware that they are HIV-positive.2 Because >20% of new HIV infections in the United States are undiagnosed,3 it is crucial to educate patients with mental illness about HIV prevention, make condoms available, and offer HIV testing.

As psychiatrists, we have a unique role in caring for patients at risk for or infected with HIV because in addition to comprehensive medical and psychiatric histories, we routinely take histories of substance use, sexual activities, relationships, and trauma, including childhood neglect and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. We develop long-term, trusting relationships and work with individuals to change behaviors and maximize life potential.

Increasing awareness of stigma, discrimination, and psychiatric factors involved with the HIV pandemic can lead to decreased transmission of HIV infection and early diagnosis and treatment. Compassionate medical and psychiatric care can mitigate suffering in persons at risk for, infected with, or affected by HIV.

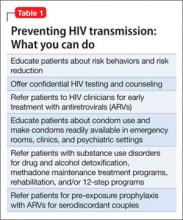

Preventing HIV transmission

AIDS differs from other complex, severe illnesses in 2 ways that are relevant to psychiatrists:

• it is almost entirely preventable

• HIV and AIDS are associated with sex, drugs, and AIDS-associated stigma and discrimination (“AIDSism”).4-6

Unsafe exposure of mucosal surfaces to the virus—primarily from exchanging body fluids in unprotected sexual encounters—accounts for 80% of new HIV infections.7 HIV transmission via sexual encounters is preventable with condoms. Percutaneous or intravenous infection with HIV—primarily from sharing needles in injection drug use—accounts for 20% of new infections.7 Use of alcohol or other substances can lead to sexual coercion, unprotected sex, and exchange of sex for drugs or money. Hence, treating substance use disorders can prevent HIV transmission.

Early diagnosis of HIV can lead to appropriate medical care, quicker onset of antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and better outcomes. Recent research has shown that pre-exposure prophylaxis with ARV treatment can prevent transmission of HIV8; therefore, becoming aware of risk behaviors and prevention can be lifesaving for serodiscordant couples.

One of the most important ways to prevent HIV’s impact on the brain and CNS is to diagnose HIV shortly after transmission at onset of acute infection. If HIV is diagnosed very early—preferably as soon as possible after inoculation with HIV or at onset of the first flu-like symptoms—and treated with ARVs, the brain has less of an opportunity to act as an independent reservoir for HIV-infected cells and therefore to develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.9,10Table 1 outlines steps psychiatrists can take to help prevent HIV transmission.

Psychiatric disorders and HIV

Psychiatric disorders and distress play a significant role in transmission of, exposure to, and infection with HIV (Table 2).4-6,11 They are relevant for prevention, clinical care, and adherence throughout every aspect of illness.

Comprehensive, compassionate, nonjudgmental care of persons at risk for or infected with HIV begins with a thorough psychiatric evaluation designed to provide an ego-supportive, sensitive, and comprehensive assessment that can guide other clinicians in providing care.12 Setting the tone and demonstrating compassion and respect includes shaking hands, which takes on special relevance in the context of AIDSism and stigma. Assessing the impact of HIV seropositivity or AIDS is best done by asking about the individual’s understanding of his or her diagnosis or illness and its impact. For some persons with HIV, verbalizing this understanding can be relieving as well as revealing. It is a chance for the patient to reveal painful experiences encountered in the home, school, camp, workplace, or community and the anguish of AIDSism and stigma.

Pay attention to sensitive and sometimes painful issues related to sexual history and sexuality. Questions related to sexual history and sexuality in heterosexual men and women as well as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals—such as “What is your sexual function like since you have been ill?” “Do feelings about your sexual identity play a role in your current level of distress?” and “What kind of barrier contraception are you using?”—are included in the comprehensive assessment described by Cohen et al.12

Comprehensive psychiatric evaluations can provide diagnoses, inform treatment, and mitigate anguish, distress, depression, anxiety, and substance use in persons with HIV and AIDS.12 A thorough and comprehensive assessment is crucial because HIV has an affinity for brain and neural tissue and can cause CNS complications such as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), even in otherwise healthy HIV-seropositive individuals. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a discussion of HAND and delirium in patients with HIV.

Some persons with HIV and AIDS do not have a psychiatric disorder, while others have multiple complex psychiatric disorders that are responses to illness or treatments or are associated with HIV/AIDS (such as HAND) or other medical illnesses and treatments (such as hepatitis C, cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, HIV nephropathy, end-stage renal disease, anemia, coronary artery disease, and cancer). See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for case studies of HIV patients with delirium, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance dependence.

Mood disorders. Depression is common among persons with HIV. Demoralization and bereavement may masquerade as depression and can complicate diagnosis and treatment. Depression and other mood disorders may be related to stigma and AIDSism as well as to biologic, psychological, social, and genetic factors. Because suicide is prevalent among persons with HIV and AIDS,13 every patient with HIV should be evaluated for depression and suicidal ideation.

PTSD is prevalent among persons with HIV. It is a risky diagnosis because it is associated with a sense of a foreshortened future, which leads to a lack of adequate self-care, poor adherence to medical care, risky behaviors, and comorbid substance dependence to help numb the pain of trauma.14,15 Persons with PTSD may have difficulty trusting clinicians and other authority figures if their trauma was a high-betrayal trauma, such as incest or military trauma.14,15

In patients with HIV, PTSD often is overlooked because it may be overshadowed by other psychiatric diagnoses. Intimate partner violence, history of childhood trauma, and childhood sexual abuse are risk factors for HIV infection and PTSD. Increased severity of HIV-related PTSD symptoms is associated with having a greater number of HIV-related physical symptoms, history of pre-HIV trauma, decreased social support, increased perception of stigma, and negative life events.

PTSD also is associated with nonadherence to risk reduction strategies and medical care.14,15 Diagnosis is further complicated by repression or retrograde amnesia of traumatic events and difficulties forming trusting relationships and disclosing HIV status to sexual partners or potential sexual partners because of fear of rejection.

Substance use disorders. Dependence on alcohol and other drugs complicates and perpetuates the HIV pandemic. Sharing needles and other drug paraphernalia is instrumental in HIV transmission. The indirect effects of alcohol and substance abuse include:

• the impact of intimate partner violence, child abuse, neglect, and/or abandonment

• development of PTSD in adults, with early childhood trauma leading to repeating their own history

• lack of self-care

• unhealthy partner choices

• use of drugs and alcohol to numb the pain associated with trauma.

Persons who are using alcohol or other drugs may have difficulty attending to their health, and substance dependence may prevent persons at risk from seeking HIV testing.

Intoxication from alcohol and drug use frequently leads to inappropriate partner choice, violent and coercive sexual behaviors, and lack of condom use. Substance dependence also may lead individuals to exchange sex for drugs and to fail to adhere to safer sexual practices or use sterile drug paraphernalia.

Treating persons with HIV/AIDS

Several organizations publish evidence-based clinical guidelines for treating depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other psychiatric disorders in patients with HIV/AIDS. One such set of guidelines is available from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute at www.hivguidelines.org. As is the case with patients who do not have HIV, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are common first-line treatments.

Psychotherapy. Patients with HIV/AIDS with psychiatric comorbidities generally respond well to psychotherapeutic treatments.16,17 The choice of therapy needs to be tailored to the needs of individuals, couples, and families coping with AIDS. Options include:

• individual, couple, family, and group psychotherapy

• crisis intervention

• 12-step programs (Alcohol Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, etc.)

• adult survivors of child abuse programs (www.ascasupport.org), groups, and workbooks

• palliative psychiatry

• bereavement therapy

• spiritual support

• relaxation response

• wellness interventions such as exercise, yoga, keeping a journal, writing a life narrative, reading, artwork, movement therapy, listening to music or books on tape, and working on crossword puzzles and jigsaw puzzles.

Psychopharmacotherapy. Accurate diagnosis and awareness of drug-drug and drug-illness interactions are important when treating patients with HIV/AIDS; consult resources in the literature18 and online resources that are updated regularly (see Related Resources). Because persons with AIDS are particularly vulnerable to extrapyramidal and anticholinergic side effects of psychotropics, the principle start very low and go very slow is critical. For patients who are opioid-dependent, be cautious when prescribing medications that are cytochrome P450 3A4 inducers—such as carbamazepine, efavirenz, nevirapine, and ritonavir—because these medications can lower methadone levels in persons receiving agonist treatment and might lead to opioid withdrawal symptoms, discontinuation of ARVs, or relapse to opioids.18 When a person with AIDS is experiencing pain and is on a maintenance dose of methadone for heroin withdrawal, pain should be treated as a separate problem with additional opioids. Methadone for relapse prevention will target opioid tolerance needs and prevent withdrawal but will not provide analgesia for pain.

HIV through the life cycle

From prevention of prenatal transmission to the care of children with HIV to reproductive issues in serodiscordant couples, HIV complicates patients’ development. Table 3 outlines concerns regarding HIV transmission and treatment at different stages of a patient’s life.

Bottom Line

HIV transmission and effective treatment are complicated by a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, including depression and other mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and cognitive disorders. With an increased understanding of the issues faced by patients at risk for or infected with HIV, psychiatrists can help prevent HIV transmission, improve adherence to medical care, and diminish suffering, morbidity, and mortality.

Related Resources

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine HIV/AIDS Psychiatry Special Interest Group. www.apm.org/sigs/oap.

- New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. HIV Clinical Resource. www.hivguidelines.org.

- University of Liverpool. HIV drug interactions list. www.hiv-druginteractions.org.

- Toronto General Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic. Drug interactions tables. www.hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_interact.html.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Nevirapine • Viramune

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol, others

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ritonavir • Norvir

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Disclosure

Dr. Cohen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Blank MB, Mandell DS, Aiken L, et al. Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):868-873.

2.Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement [published online April 30, 2013]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645.

3. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520-529.

4. Cohen MA. AIDSism, a new form of discrimination. Am Med News. 1989;32:43.

5. Cohen MA, Gorman JM. Comprehensive textbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

6. Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global HIV/AIDS response. Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. Progress report 2011. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/

contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/

20111130_UA_Report_en.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2013.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586-589.

9. Cysique LA, Murray JM, Dunbar M, et al. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Med. 2010;11(10):642-649.

10. Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1243-1250.

11. Cohen M, Hoffman RG, Cromwell C, et al. The prevalence of distress in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):10-15.

12. Cohen MA, Batista SM, Lux JZ. A biopsychosocial approach to psychiatric consultation in persons with HIV and AIDS. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:33-60.

13. Carrico AW. Elevated suicide rate among HIV-positive persons despite benefits of antiretroviral therapy: implications for a stress and coping model of suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):117-119.

14. Cohen MA, Alfonso CA, Hoffman RG, et al. The impact of PTSD on treatment adherence in persons with HIV infection. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(5):294-296.

15. Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, et al. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253-261.

16. Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Ghebremichael M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a coping group intervention for adults with HIV who are AIDS bereaved: longitudinal effects on grief. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):563-570.

17. Cohen MA. Psychodynamic psychotherapy in an AIDS nursing home. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1999;27(1):121-133.

18. Cozza KL, Goforth HW, Batista SM. Psychopharmacologic treatment issues in AIDS psychiatry. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:147-199.

The prevalence of HIV in persons with untreated psychiatric illness may be 10 to 20 times that of the general population.1 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended HIV screening of all persons age 15 to 65 because 20% to 25% of individuals with HIV infection are unaware that they are HIV-positive.2 Because >20% of new HIV infections in the United States are undiagnosed,3 it is crucial to educate patients with mental illness about HIV prevention, make condoms available, and offer HIV testing.

As psychiatrists, we have a unique role in caring for patients at risk for or infected with HIV because in addition to comprehensive medical and psychiatric histories, we routinely take histories of substance use, sexual activities, relationships, and trauma, including childhood neglect and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. We develop long-term, trusting relationships and work with individuals to change behaviors and maximize life potential.

Increasing awareness of stigma, discrimination, and psychiatric factors involved with the HIV pandemic can lead to decreased transmission of HIV infection and early diagnosis and treatment. Compassionate medical and psychiatric care can mitigate suffering in persons at risk for, infected with, or affected by HIV.

Preventing HIV transmission

AIDS differs from other complex, severe illnesses in 2 ways that are relevant to psychiatrists:

• it is almost entirely preventable

• HIV and AIDS are associated with sex, drugs, and AIDS-associated stigma and discrimination (“AIDSism”).4-6

Unsafe exposure of mucosal surfaces to the virus—primarily from exchanging body fluids in unprotected sexual encounters—accounts for 80% of new HIV infections.7 HIV transmission via sexual encounters is preventable with condoms. Percutaneous or intravenous infection with HIV—primarily from sharing needles in injection drug use—accounts for 20% of new infections.7 Use of alcohol or other substances can lead to sexual coercion, unprotected sex, and exchange of sex for drugs or money. Hence, treating substance use disorders can prevent HIV transmission.

Early diagnosis of HIV can lead to appropriate medical care, quicker onset of antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and better outcomes. Recent research has shown that pre-exposure prophylaxis with ARV treatment can prevent transmission of HIV8; therefore, becoming aware of risk behaviors and prevention can be lifesaving for serodiscordant couples.

One of the most important ways to prevent HIV’s impact on the brain and CNS is to diagnose HIV shortly after transmission at onset of acute infection. If HIV is diagnosed very early—preferably as soon as possible after inoculation with HIV or at onset of the first flu-like symptoms—and treated with ARVs, the brain has less of an opportunity to act as an independent reservoir for HIV-infected cells and therefore to develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.9,10Table 1 outlines steps psychiatrists can take to help prevent HIV transmission.

Psychiatric disorders and HIV

Psychiatric disorders and distress play a significant role in transmission of, exposure to, and infection with HIV (Table 2).4-6,11 They are relevant for prevention, clinical care, and adherence throughout every aspect of illness.

Comprehensive, compassionate, nonjudgmental care of persons at risk for or infected with HIV begins with a thorough psychiatric evaluation designed to provide an ego-supportive, sensitive, and comprehensive assessment that can guide other clinicians in providing care.12 Setting the tone and demonstrating compassion and respect includes shaking hands, which takes on special relevance in the context of AIDSism and stigma. Assessing the impact of HIV seropositivity or AIDS is best done by asking about the individual’s understanding of his or her diagnosis or illness and its impact. For some persons with HIV, verbalizing this understanding can be relieving as well as revealing. It is a chance for the patient to reveal painful experiences encountered in the home, school, camp, workplace, or community and the anguish of AIDSism and stigma.

Pay attention to sensitive and sometimes painful issues related to sexual history and sexuality. Questions related to sexual history and sexuality in heterosexual men and women as well as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals—such as “What is your sexual function like since you have been ill?” “Do feelings about your sexual identity play a role in your current level of distress?” and “What kind of barrier contraception are you using?”—are included in the comprehensive assessment described by Cohen et al.12

Comprehensive psychiatric evaluations can provide diagnoses, inform treatment, and mitigate anguish, distress, depression, anxiety, and substance use in persons with HIV and AIDS.12 A thorough and comprehensive assessment is crucial because HIV has an affinity for brain and neural tissue and can cause CNS complications such as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), even in otherwise healthy HIV-seropositive individuals. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a discussion of HAND and delirium in patients with HIV.

Some persons with HIV and AIDS do not have a psychiatric disorder, while others have multiple complex psychiatric disorders that are responses to illness or treatments or are associated with HIV/AIDS (such as HAND) or other medical illnesses and treatments (such as hepatitis C, cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, HIV nephropathy, end-stage renal disease, anemia, coronary artery disease, and cancer). See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for case studies of HIV patients with delirium, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance dependence.

Mood disorders. Depression is common among persons with HIV. Demoralization and bereavement may masquerade as depression and can complicate diagnosis and treatment. Depression and other mood disorders may be related to stigma and AIDSism as well as to biologic, psychological, social, and genetic factors. Because suicide is prevalent among persons with HIV and AIDS,13 every patient with HIV should be evaluated for depression and suicidal ideation.

PTSD is prevalent among persons with HIV. It is a risky diagnosis because it is associated with a sense of a foreshortened future, which leads to a lack of adequate self-care, poor adherence to medical care, risky behaviors, and comorbid substance dependence to help numb the pain of trauma.14,15 Persons with PTSD may have difficulty trusting clinicians and other authority figures if their trauma was a high-betrayal trauma, such as incest or military trauma.14,15

In patients with HIV, PTSD often is overlooked because it may be overshadowed by other psychiatric diagnoses. Intimate partner violence, history of childhood trauma, and childhood sexual abuse are risk factors for HIV infection and PTSD. Increased severity of HIV-related PTSD symptoms is associated with having a greater number of HIV-related physical symptoms, history of pre-HIV trauma, decreased social support, increased perception of stigma, and negative life events.

PTSD also is associated with nonadherence to risk reduction strategies and medical care.14,15 Diagnosis is further complicated by repression or retrograde amnesia of traumatic events and difficulties forming trusting relationships and disclosing HIV status to sexual partners or potential sexual partners because of fear of rejection.

Substance use disorders. Dependence on alcohol and other drugs complicates and perpetuates the HIV pandemic. Sharing needles and other drug paraphernalia is instrumental in HIV transmission. The indirect effects of alcohol and substance abuse include:

• the impact of intimate partner violence, child abuse, neglect, and/or abandonment

• development of PTSD in adults, with early childhood trauma leading to repeating their own history

• lack of self-care

• unhealthy partner choices

• use of drugs and alcohol to numb the pain associated with trauma.

Persons who are using alcohol or other drugs may have difficulty attending to their health, and substance dependence may prevent persons at risk from seeking HIV testing.

Intoxication from alcohol and drug use frequently leads to inappropriate partner choice, violent and coercive sexual behaviors, and lack of condom use. Substance dependence also may lead individuals to exchange sex for drugs and to fail to adhere to safer sexual practices or use sterile drug paraphernalia.

Treating persons with HIV/AIDS

Several organizations publish evidence-based clinical guidelines for treating depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other psychiatric disorders in patients with HIV/AIDS. One such set of guidelines is available from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute at www.hivguidelines.org. As is the case with patients who do not have HIV, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are common first-line treatments.

Psychotherapy. Patients with HIV/AIDS with psychiatric comorbidities generally respond well to psychotherapeutic treatments.16,17 The choice of therapy needs to be tailored to the needs of individuals, couples, and families coping with AIDS. Options include:

• individual, couple, family, and group psychotherapy

• crisis intervention

• 12-step programs (Alcohol Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, etc.)

• adult survivors of child abuse programs (www.ascasupport.org), groups, and workbooks

• palliative psychiatry

• bereavement therapy

• spiritual support

• relaxation response

• wellness interventions such as exercise, yoga, keeping a journal, writing a life narrative, reading, artwork, movement therapy, listening to music or books on tape, and working on crossword puzzles and jigsaw puzzles.

Psychopharmacotherapy. Accurate diagnosis and awareness of drug-drug and drug-illness interactions are important when treating patients with HIV/AIDS; consult resources in the literature18 and online resources that are updated regularly (see Related Resources). Because persons with AIDS are particularly vulnerable to extrapyramidal and anticholinergic side effects of psychotropics, the principle start very low and go very slow is critical. For patients who are opioid-dependent, be cautious when prescribing medications that are cytochrome P450 3A4 inducers—such as carbamazepine, efavirenz, nevirapine, and ritonavir—because these medications can lower methadone levels in persons receiving agonist treatment and might lead to opioid withdrawal symptoms, discontinuation of ARVs, or relapse to opioids.18 When a person with AIDS is experiencing pain and is on a maintenance dose of methadone for heroin withdrawal, pain should be treated as a separate problem with additional opioids. Methadone for relapse prevention will target opioid tolerance needs and prevent withdrawal but will not provide analgesia for pain.

HIV through the life cycle

From prevention of prenatal transmission to the care of children with HIV to reproductive issues in serodiscordant couples, HIV complicates patients’ development. Table 3 outlines concerns regarding HIV transmission and treatment at different stages of a patient’s life.

Bottom Line

HIV transmission and effective treatment are complicated by a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, including depression and other mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and cognitive disorders. With an increased understanding of the issues faced by patients at risk for or infected with HIV, psychiatrists can help prevent HIV transmission, improve adherence to medical care, and diminish suffering, morbidity, and mortality.

Related Resources

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine HIV/AIDS Psychiatry Special Interest Group. www.apm.org/sigs/oap.

- New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. HIV Clinical Resource. www.hivguidelines.org.

- University of Liverpool. HIV drug interactions list. www.hiv-druginteractions.org.

- Toronto General Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic. Drug interactions tables. www.hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_interact.html.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Nevirapine • Viramune

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol, others

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ritonavir • Norvir

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Disclosure

Dr. Cohen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Blank MB, Mandell DS, Aiken L, et al. Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):868-873.

2.Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement [published online April 30, 2013]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645.

3. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520-529.

4. Cohen MA. AIDSism, a new form of discrimination. Am Med News. 1989;32:43.

5. Cohen MA, Gorman JM. Comprehensive textbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

6. Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global HIV/AIDS response. Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. Progress report 2011. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/

contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/

20111130_UA_Report_en.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2013.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586-589.

9. Cysique LA, Murray JM, Dunbar M, et al. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Med. 2010;11(10):642-649.

10. Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1243-1250.

11. Cohen M, Hoffman RG, Cromwell C, et al. The prevalence of distress in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):10-15.

12. Cohen MA, Batista SM, Lux JZ. A biopsychosocial approach to psychiatric consultation in persons with HIV and AIDS. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:33-60.

13. Carrico AW. Elevated suicide rate among HIV-positive persons despite benefits of antiretroviral therapy: implications for a stress and coping model of suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):117-119.

14. Cohen MA, Alfonso CA, Hoffman RG, et al. The impact of PTSD on treatment adherence in persons with HIV infection. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(5):294-296.

15. Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, et al. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253-261.

16. Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Ghebremichael M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a coping group intervention for adults with HIV who are AIDS bereaved: longitudinal effects on grief. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):563-570.

17. Cohen MA. Psychodynamic psychotherapy in an AIDS nursing home. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1999;27(1):121-133.

18. Cozza KL, Goforth HW, Batista SM. Psychopharmacologic treatment issues in AIDS psychiatry. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:147-199.

The prevalence of HIV in persons with untreated psychiatric illness may be 10 to 20 times that of the general population.1 The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has recommended HIV screening of all persons age 15 to 65 because 20% to 25% of individuals with HIV infection are unaware that they are HIV-positive.2 Because >20% of new HIV infections in the United States are undiagnosed,3 it is crucial to educate patients with mental illness about HIV prevention, make condoms available, and offer HIV testing.

As psychiatrists, we have a unique role in caring for patients at risk for or infected with HIV because in addition to comprehensive medical and psychiatric histories, we routinely take histories of substance use, sexual activities, relationships, and trauma, including childhood neglect and emotional, physical, and sexual abuse. We develop long-term, trusting relationships and work with individuals to change behaviors and maximize life potential.

Increasing awareness of stigma, discrimination, and psychiatric factors involved with the HIV pandemic can lead to decreased transmission of HIV infection and early diagnosis and treatment. Compassionate medical and psychiatric care can mitigate suffering in persons at risk for, infected with, or affected by HIV.

Preventing HIV transmission

AIDS differs from other complex, severe illnesses in 2 ways that are relevant to psychiatrists:

• it is almost entirely preventable

• HIV and AIDS are associated with sex, drugs, and AIDS-associated stigma and discrimination (“AIDSism”).4-6

Unsafe exposure of mucosal surfaces to the virus—primarily from exchanging body fluids in unprotected sexual encounters—accounts for 80% of new HIV infections.7 HIV transmission via sexual encounters is preventable with condoms. Percutaneous or intravenous infection with HIV—primarily from sharing needles in injection drug use—accounts for 20% of new infections.7 Use of alcohol or other substances can lead to sexual coercion, unprotected sex, and exchange of sex for drugs or money. Hence, treating substance use disorders can prevent HIV transmission.

Early diagnosis of HIV can lead to appropriate medical care, quicker onset of antiretroviral (ARV) treatment, and better outcomes. Recent research has shown that pre-exposure prophylaxis with ARV treatment can prevent transmission of HIV8; therefore, becoming aware of risk behaviors and prevention can be lifesaving for serodiscordant couples.

One of the most important ways to prevent HIV’s impact on the brain and CNS is to diagnose HIV shortly after transmission at onset of acute infection. If HIV is diagnosed very early—preferably as soon as possible after inoculation with HIV or at onset of the first flu-like symptoms—and treated with ARVs, the brain has less of an opportunity to act as an independent reservoir for HIV-infected cells and therefore to develop HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders.9,10Table 1 outlines steps psychiatrists can take to help prevent HIV transmission.

Psychiatric disorders and HIV

Psychiatric disorders and distress play a significant role in transmission of, exposure to, and infection with HIV (Table 2).4-6,11 They are relevant for prevention, clinical care, and adherence throughout every aspect of illness.

Comprehensive, compassionate, nonjudgmental care of persons at risk for or infected with HIV begins with a thorough psychiatric evaluation designed to provide an ego-supportive, sensitive, and comprehensive assessment that can guide other clinicians in providing care.12 Setting the tone and demonstrating compassion and respect includes shaking hands, which takes on special relevance in the context of AIDSism and stigma. Assessing the impact of HIV seropositivity or AIDS is best done by asking about the individual’s understanding of his or her diagnosis or illness and its impact. For some persons with HIV, verbalizing this understanding can be relieving as well as revealing. It is a chance for the patient to reveal painful experiences encountered in the home, school, camp, workplace, or community and the anguish of AIDSism and stigma.

Pay attention to sensitive and sometimes painful issues related to sexual history and sexuality. Questions related to sexual history and sexuality in heterosexual men and women as well as gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender individuals—such as “What is your sexual function like since you have been ill?” “Do feelings about your sexual identity play a role in your current level of distress?” and “What kind of barrier contraception are you using?”—are included in the comprehensive assessment described by Cohen et al.12

Comprehensive psychiatric evaluations can provide diagnoses, inform treatment, and mitigate anguish, distress, depression, anxiety, and substance use in persons with HIV and AIDS.12 A thorough and comprehensive assessment is crucial because HIV has an affinity for brain and neural tissue and can cause CNS complications such as HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders (HAND), even in otherwise healthy HIV-seropositive individuals. See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for a discussion of HAND and delirium in patients with HIV.

Some persons with HIV and AIDS do not have a psychiatric disorder, while others have multiple complex psychiatric disorders that are responses to illness or treatments or are associated with HIV/AIDS (such as HAND) or other medical illnesses and treatments (such as hepatitis C, cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease, HIV nephropathy, end-stage renal disease, anemia, coronary artery disease, and cancer). See this article at CurrentPsychiatry.com for case studies of HIV patients with delirium, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and substance dependence.

Mood disorders. Depression is common among persons with HIV. Demoralization and bereavement may masquerade as depression and can complicate diagnosis and treatment. Depression and other mood disorders may be related to stigma and AIDSism as well as to biologic, psychological, social, and genetic factors. Because suicide is prevalent among persons with HIV and AIDS,13 every patient with HIV should be evaluated for depression and suicidal ideation.

PTSD is prevalent among persons with HIV. It is a risky diagnosis because it is associated with a sense of a foreshortened future, which leads to a lack of adequate self-care, poor adherence to medical care, risky behaviors, and comorbid substance dependence to help numb the pain of trauma.14,15 Persons with PTSD may have difficulty trusting clinicians and other authority figures if their trauma was a high-betrayal trauma, such as incest or military trauma.14,15

In patients with HIV, PTSD often is overlooked because it may be overshadowed by other psychiatric diagnoses. Intimate partner violence, history of childhood trauma, and childhood sexual abuse are risk factors for HIV infection and PTSD. Increased severity of HIV-related PTSD symptoms is associated with having a greater number of HIV-related physical symptoms, history of pre-HIV trauma, decreased social support, increased perception of stigma, and negative life events.

PTSD also is associated with nonadherence to risk reduction strategies and medical care.14,15 Diagnosis is further complicated by repression or retrograde amnesia of traumatic events and difficulties forming trusting relationships and disclosing HIV status to sexual partners or potential sexual partners because of fear of rejection.

Substance use disorders. Dependence on alcohol and other drugs complicates and perpetuates the HIV pandemic. Sharing needles and other drug paraphernalia is instrumental in HIV transmission. The indirect effects of alcohol and substance abuse include:

• the impact of intimate partner violence, child abuse, neglect, and/or abandonment

• development of PTSD in adults, with early childhood trauma leading to repeating their own history

• lack of self-care

• unhealthy partner choices

• use of drugs and alcohol to numb the pain associated with trauma.

Persons who are using alcohol or other drugs may have difficulty attending to their health, and substance dependence may prevent persons at risk from seeking HIV testing.

Intoxication from alcohol and drug use frequently leads to inappropriate partner choice, violent and coercive sexual behaviors, and lack of condom use. Substance dependence also may lead individuals to exchange sex for drugs and to fail to adhere to safer sexual practices or use sterile drug paraphernalia.

Treating persons with HIV/AIDS

Several organizations publish evidence-based clinical guidelines for treating depression, anxiety, substance abuse, and other psychiatric disorders in patients with HIV/AIDS. One such set of guidelines is available from the New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute at www.hivguidelines.org. As is the case with patients who do not have HIV, psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy are common first-line treatments.

Psychotherapy. Patients with HIV/AIDS with psychiatric comorbidities generally respond well to psychotherapeutic treatments.16,17 The choice of therapy needs to be tailored to the needs of individuals, couples, and families coping with AIDS. Options include:

• individual, couple, family, and group psychotherapy

• crisis intervention

• 12-step programs (Alcohol Anonymous, Narcotics Anonymous, etc.)

• adult survivors of child abuse programs (www.ascasupport.org), groups, and workbooks

• palliative psychiatry

• bereavement therapy

• spiritual support

• relaxation response

• wellness interventions such as exercise, yoga, keeping a journal, writing a life narrative, reading, artwork, movement therapy, listening to music or books on tape, and working on crossword puzzles and jigsaw puzzles.

Psychopharmacotherapy. Accurate diagnosis and awareness of drug-drug and drug-illness interactions are important when treating patients with HIV/AIDS; consult resources in the literature18 and online resources that are updated regularly (see Related Resources). Because persons with AIDS are particularly vulnerable to extrapyramidal and anticholinergic side effects of psychotropics, the principle start very low and go very slow is critical. For patients who are opioid-dependent, be cautious when prescribing medications that are cytochrome P450 3A4 inducers—such as carbamazepine, efavirenz, nevirapine, and ritonavir—because these medications can lower methadone levels in persons receiving agonist treatment and might lead to opioid withdrawal symptoms, discontinuation of ARVs, or relapse to opioids.18 When a person with AIDS is experiencing pain and is on a maintenance dose of methadone for heroin withdrawal, pain should be treated as a separate problem with additional opioids. Methadone for relapse prevention will target opioid tolerance needs and prevent withdrawal but will not provide analgesia for pain.

HIV through the life cycle

From prevention of prenatal transmission to the care of children with HIV to reproductive issues in serodiscordant couples, HIV complicates patients’ development. Table 3 outlines concerns regarding HIV transmission and treatment at different stages of a patient’s life.

Bottom Line

HIV transmission and effective treatment are complicated by a high prevalence of psychiatric comorbidities, including depression and other mood disorders, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance use disorders, and cognitive disorders. With an increased understanding of the issues faced by patients at risk for or infected with HIV, psychiatrists can help prevent HIV transmission, improve adherence to medical care, and diminish suffering, morbidity, and mortality.

Related Resources

- Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine HIV/AIDS Psychiatry Special Interest Group. www.apm.org/sigs/oap.

- New York State Department of Health AIDS Institute. HIV Clinical Resource. www.hivguidelines.org.

- University of Liverpool. HIV drug interactions list. www.hiv-druginteractions.org.

- Toronto General Hospital Immunodeficiency Clinic. Drug interactions tables. www.hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_interact.html.

Drug Brand Names

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Nevirapine • Viramune

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol, others

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Clonazepam • Klonopin

Ritonavir • Norvir

Efavirenz • Sustiva

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Disclosure

Dr. Cohen reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Blank MB, Mandell DS, Aiken L, et al. Co-occurrence of HIV and serious mental illness among Medicaid recipients. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):868-873.

2.Moyer VA, on behalf of the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for HIV: U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement [published online April 30, 2013]. Ann Intern Med. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-159-1-201307020-00645.

3. Hall HI, Song R, Rhodes P, et al. Estimation of HIV incidence in the United States. JAMA. 2008;300(5):520-529.

4. Cohen MA. AIDSism, a new form of discrimination. Am Med News. 1989;32:43.

5. Cohen MA, Gorman JM. Comprehensive textbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2008.

6. Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010.

7. World Health Organization, United Nations Children’s Fund, Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS. Global HIV/AIDS response. Epidemic update and health sector progress towards universal access. Progress report 2011. http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/

contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2011/

20111130_UA_Report_en.pdf. Accessed April 25, 2013.

8. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Interim guidance for clinicians considering the use of preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection in heterosexually active adults. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(31):586-589.

9. Cysique LA, Murray JM, Dunbar M, et al. A screening algorithm for HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders. HIV Med. 2010;11(10):642-649.

10. Simioni S, Cavassini M, Annoni JM, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in HIV patients despite long-standing suppression of viremia. AIDS. 2010;24(9):1243-1250.

11. Cohen M, Hoffman RG, Cromwell C, et al. The prevalence of distress in persons with human immunodeficiency virus infection. Psychosomatics. 2002;43(1):10-15.

12. Cohen MA, Batista SM, Lux JZ. A biopsychosocial approach to psychiatric consultation in persons with HIV and AIDS. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:33-60.

13. Carrico AW. Elevated suicide rate among HIV-positive persons despite benefits of antiretroviral therapy: implications for a stress and coping model of suicide. Am J Psychiatry. 2010;167(2):117-119.

14. Cohen MA, Alfonso CA, Hoffman RG, et al. The impact of PTSD on treatment adherence in persons with HIV infection. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2001;23(5):294-296.

15. Boarts JM, Sledjeski EM, Bogart LM, et al. The differential impact of PTSD and depression on HIV disease markers and adherence to HAART in people living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(3):253-261.

16. Sikkema KJ, Hansen NB, Ghebremichael M, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a coping group intervention for adults with HIV who are AIDS bereaved: longitudinal effects on grief. Health Psychol. 2006;25(5):563-570.

17. Cohen MA. Psychodynamic psychotherapy in an AIDS nursing home. J Am Acad Psychoanal. 1999;27(1):121-133.

18. Cozza KL, Goforth HW, Batista SM. Psychopharmacologic treatment issues in AIDS psychiatry. In: Cohen MA, Goforth HW, Lux JZ, et al, eds. Handbook of AIDS psychiatry. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2010:147-199.

Evaluating psychotic patients' risk of violence

Understanding psychosis

PSYCHIATRY UPDATE 2014

Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists welcomed more than 550 psychiatric practitioners from across the United States and abroad to this annual conference, which was headed by Meeting Chair Richard Balon, MD, and Co-chairs Donald W. Black, MD, and Nagy Youssef, MD, March 27-29, 2014 at the Hilton Chicago in Chicago, Illinois. Attendees earned as many as 10 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™.

Thursday, March 27, 2014

MORNING SESSION

Obsessive-compulsive disorder can be misdiagnosed as psychosis, anxiety, or a sexual disorder. In addition to contamination, patients can present with pathologic doubt, somatic obsessions, or obsessions about taboo or symmetry. Among FDA-approved medications, clomipramine might be more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Exposure response prevention therapy shows better response than pharmacotherapy, but best outcomes are seen with combination therapy. Jon E. Grant, JD, MD, MPH, University of Chicago, also discussed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, hoarding, trichotillomania, and excoriation disorder—as well as changes in DSM-5 that cover this group of disorders.

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk of death from cardiac and pulmonary disease than the general population. The quality of care of patients with psychosis generally is poor, because of lack of recognition, time, and resources, as well as systematic barriers to accessing health care. Questions about weight gain, lethargy, infections, and sexual functioning can help the practitioner assess a patient’s general health. When appropriate, Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, St. Louis University School of Medicine, recommends, consider switching antipsychotics, which might reverse adverse metabolic events.

Nonpharmacologic treatment goals include improving sleep, educating patients, providing them with tools for improving sleep, and creating an opportunity for patient-practitioner discussion. Stimulus control and sleep restriction are primary therapeutic techniques to improve sleep quality and reduce non-sleeping time in bed. Thomas Roth, PhD, Henry Ford Hospital, also discussed how to modify sleep hygiene techniques for pediatric, adolescent, and geriatric patients.

Donald W. Black, MD, University of Iowa, says that work groups for DSM-5 were asked to consider dimensionality and culture and gender issues. New diagnostic categories include obsessive-compulsive and related disorders and trauma and stressor-related disorders. Some diagnoses were reformulated or introduced, including autism spectrum disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. The multi-axial system was discontinued in DSM-5. He also reviewed coding issues.

In a sponsored symposium, Prakash S. Masand, MD, Global Medical Education, Inc., looked at the clinical challenges of addressing all 3 symptom domains that characterize depression (emotional, physical, and cognitive) as an introduction to reviewing the efficacy, mechanism of action, and side effects of vortioxetine (Brintellix), a new serotonergic agent for treating major depressive disorder (MDD). In all studies submitted to the FDA, vortioxetine was found to be superior to placebo, in at least 1 dosage group, for alleviating depressive symptoms and for reducing the risk of depressive recurrence.

AFTERNOON SESSION

Oppositional defiant disorder is more common in boys (onset at age 6 to 10) and is associated with inconsistent and neglectful parenting. Treatment modalities, including educational training, anticonvulsants, and lithium, do not have a strong evidence base. Intermittent explosive disorder is characterized by short-lived but frequent behavioral outbursts and often begins in adolescence. Dr. Grant also reviewed the evidence on conduct disorder, pyromania, and kleptomania.

Cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia often appear before psychotic symptoms and remain stable across the lifespan. There are no pharmacologic treatments for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia; however, Dr. Nasrallah listed tactics to improve cognitive function, including regular aerobic exercise. These cognitive deficits can be categorized as neurocognitive (memory, learning, executive function) and social (social skills, theory of mind, social cues) and contribute to functional decline and often prevent patients from working and going to school. Dr. Nasrallah described how bipolar disorder (BD) overlaps with schizophrenia in terms of cognitive dysfunction.

Henry Nasrallah, MD

Psychiatric disorders exhibit specific sleep/ wake impairments. Sleep disorders can mimic psychiatric symptoms, such as fatigue, cognitive problems, and depression. Sleep disturbances, including insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, and decreased need for sleep, often coexist with depression, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and BD, and insomnia is associated with a greater risk of suicide. With antidepressant treatment, sleep in depressed patients improves but does not normalize. Dr. Roth also reviewed pharmacotherapeutic options and non-drug modalities to improve patients’ sleep.

Antidepressants have no efficacy in treating acute episodes of bipolar depression, and using such agents might yield a poor long-term outcome in BD, according to Robert M. Post, MD, George Washington University School of Medicine, Michael J. Ostacher, MD, MPH, MMSc, Stanford University, and Vivek Singh, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, in an interactive faculty discussion. For patients with bipolar I disorder, lithium monotherapy or the combination of lithium and valproate is more effective than valproate alone; evidence does not support valproate as a maintenance treatment. When a patient with BD shows partial response, attendees at this sponsored symposium were advised, consider adding psychotherapy and psycho-education. Combining a mood stabilizer and an antipsychotic might be more effective than monotherapy and safer, by allowing lower dosages. The only 3 treatments FDA-approved for bipolar depression are the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, quetiapine, and lurasidone.

Boaz Levy, PhD, (left) receives the 2014 George Winokur Research Award from Carol S. North, MD, for his article on recovery of cognitive function in patients with co-occuring bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence.

Friday, March 28, 2014

MORNING SESSION

Carmen Pinto, MD, at a sponsored symposium, reviewed the utility and safety of

long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics for treating schizophrenia, with a focus on LAI aripiprazole, a partial HT-receptor agonist/partial HT-receptor antagonist. Four monthly injections (400 mg/injection) of the drug are needed to reach steady state; each injection reaches peak level in 5 to 7 days. LAI aripiprazole has been shown to delay time to relapse due to nonadherence and onset of nonresponse to the drug, and has high patient acceptance—even in those who already stable. Safety and side effects with LAI aripiprazole are the same as seen with the oral formulation.

In multimodal therapy for chronic pain, psychiatrists have a role in assessing

psychiatric comorbidities, coping ability, social functioning, and other life functions, including work and personal relationships. Cognitive-behavioral therapy can be particularly useful for chronic pain by helping patients reframe their pain experiences. Raphael J. Leo, MA, MD, FAPM, University at Buffalo, reviewed non-opioid co-analgesics that can be used for patients with comorbid pain and a substance use disorder. If opioids are necessary, consider “weak” or long-acting opioids. Monitor patients for aberrant, drug-seeking behavior.

In the second part of his overview, Dr. Black highlighted specific changes to DSM-5 of particular concern to clinicians. New chapters were created and disorders were consolidated, he explained, such as autism spectrum disorder, somatic symptom disorder, and major neurocognitive disorder. New diagnoses include hoarding disorder and binge eating disorder. Subtypes of schizophrenia were dropped. Pathologic gambling was renamed gambling disorder and gender dysphoria is now called gender identity disorder. The bereavement exclusion of a major depressive episode was dropped.

Antidepressants are effective in mitigating pain in neuropathy, headache, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain, and have been advocated for other pain syndromes. Selection of an antidepressant depends on the type of pain condition, comorbid depression or anxiety, tolerability, and medical comorbidities. Dr. Leo presented prescribing strategies for tricyclics, serotoninnorepinephrine

reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs, and other antidepressants.

Treating of BD in geriatric patients becomes complicated because therapeutic choices are narrowed and response to therapy is less successful with age, according to George T. Grossberg, MD, St. Louis University. Rapid cycling tends to be the norm in geriatric BD patients. Look for agitation and irritability, rather than full-blown mania; grandiose delusions; psychiatric comorbidity, especially anxiety disorder; and sexually inappropriate behavior. Pharmacotherapeutic options include: mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics, and antidepressants (specifically, bupropion and SSRIs—not TCAs, venlafaxine, or duloxetine—and over the short term only). Consider divalproex for mania and hypomania, used cautiously because of its adverse side-effect potential.

George T. Grossberg, MD

AFTERNOON SESSION

Often, BD is misdiagnosed as unipolar depression, or the correct diagnosis of BD is delayed, according to Gustavo Alva, MD, ATP Clinical Research. Comorbid substance use disorder or an anxiety disorder is common. Comorbid cardiovascular disease brings a greater risk of mortality in patients with BD than suicide. Approximately two-thirds of patients with BD are taking adjunctive medications; however, antidepressants are no more effective than placebo in treating bipolar depression. At this sponsored symposium, Vladimir Maletic, MD, University of South Carolina, described a 6-week trial in which lurasidone plus lithium or divalporex was more effective in reducing depression, as measured by MADRS, than placebo plus lithium or akathisia, somnolence, and extrapyramidal symptoms.

When assessing an older patient with psychosis, first establish the cause of the symptoms, such as Alzheimer’s disease, affective disorder, substance use, or hallucinations associated with grief. Older patients with schizophrenia who have been taking typical antipsychotics for years might benefit from a switch to an atypical or a dosage reduction. Dr. Grossberg recommends considering antipsychotics for older patients when symptoms cause severe emotional distress that does not respond to other interventions or an acute episode that poses a safety risk for patients or others. Choose an antipsychotic based on side effects, and “start low and go slow,” when possible. The goal is to reduce agitation and distress—not necessarily to resolve psychotic symptoms.

Anita H. Clayton, MD, University of Virginia Health System, provided a review of sexual function from puberty through midlife and older years. Social factors play a role in sexual satisfaction, such as gender expectations, religious beliefs, and the influence of reporting in the media. Sexual dysfunction becomes worse in men after age 29; in women, the rate of sexual dysfunction appears to be consistent across the lifespan. Cardiovascular disease is a significant risk factor for sexual dysfunction in men, but not in women. Sexual function and depression have a bidirectional relationship; sexual dysfunction may be a symptom or cause of depression and antidepressants may affect desire and function. Medications, including psychotropics, oral contraceptives, and opioids, can cause sexual dysfunction.

Providers often are reluctant to bring up sexual issues with their patients, Dr. Clayton says, but patients often want to talk about their sexual problems. In reproductive-age women, look for hypoactive sexual desire disorder and pain. In men, assess for erectile dysfunction or premature ejaculation. Inquire about every phase of the sexual response cycle. When managing sexual dysfunction, aim to minimize contributing factors such as illness or medication, consider FDA-approved medications, encourage a healthy lifestyle, and employ psychological interventions when appropriate. In patients with antidepressant-associated sexual dysfunction, consider switching medications or adding an antidote, such as bupropion, buspirone, or sildenafil.

Saturday, March 29, 2014

MORNING SESSION

Because of the lack of double-blind, placebo-controlled trials, the risks of untreated depression vs the risks of antidepressant use in pregnancy are unclear. Marlene P. Freeman, MD, Massachusetts General Hospital, described the limited, long-term data on tricyclics and fluoxetine. Some studies have shown a small risk of birth defects with SSRIs; others did not find an association. For moderate or severe depression, use antidepressants at the lowest dosage and try non-medication options, such as psychotherapy and complementary and alternative medicine. During the third trimester, women may need a higher dosage to maintain therapeutic drug levels. Data indicates that folic acid use during pregnancy is associated with a decreased risk of autism and schizophrenia.

James W. Jefferson, MD, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, recommends ruling out medical conditions, such as cancer, that might be causing your patients’ fatigue or depression. Many medications, including over-the-counter agents and supplements, can cause fatigue. Bupropion was more effective than placebo and SSRIs in treating depressed patients with sleepiness and fatigue. Adding a psychostimulant to an SSRI does not have a significantly better effect than placebo on depressive symptoms. Adjunctive modafanil may improve depression and fatigue. Data for dopamine agonists are limited.

Lithium should be used with caution in pregnant women because of the risk of congenital malformations. Dr. Freeman also discussed the potential risks to the fetus with the mother’s use of valproate and lamotrigine (with the latter, a small increase in oral clefting). High-potency typical antipsychotics are considered safe; low-potency drugs have a higher risk of major malformations. For atypicals, the risk of malformations appears minimal; newborns might display extrapyramidal effects and withdrawal symptoms. Infants exposed to psychostimulants may have lower birth weight, but are not at increased risk of birth defects.

Dr. Jefferson reviewed the efficacy, pharmacokinetics, and adverse effects of vilazodone, levomilnacipran, and vortioxetine, which are antidepressants new to the market. Dr. Jefferson recommends reading package inserts to become familiar with new drugs. He also described studies of medications that were not FDA-approved, including edivoxetine, quetiapine XR monotherapy for MDD, and agomelatine. Agents under investigation include onabotulinumtoxin A injections, ketamine, and lanicemine.

Katherine E. Burdick, PhD, Mount Sinai School of Medicine, defined cognitive domains. First-episode MDD patients perform worse in psychomotor speed and attention than healthy controls. Late-onset depression (after age 60) is associated with worse performance on processing speed and verbal memory. Cognitive deficits in depressed patients range from mild to moderate and are influenced by symptom status and duration of illness. Treating cognitive deficits begins with prevention. Cholinesterase inhibitors are not effective for improving cognition in MDD. Antidepressants, including SSRIs, do not adequately treat cognitive deficits, Roger S. McIntyre, MD, FRCPC, University of Toronto, explained.

Current Psychiatry and the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists welcomed more than 550 psychiatric practitioners from across the United States and abroad to this annual conference, which was headed by Meeting Chair Richard Balon, MD, and Co-chairs Donald W. Black, MD, and Nagy Youssef, MD, March 27-29, 2014 at the Hilton Chicago in Chicago, Illinois. Attendees earned as many as 10 AMA PRA Category 1 Credits™.

Thursday, March 27, 2014

MORNING SESSION

Obsessive-compulsive disorder can be misdiagnosed as psychosis, anxiety, or a sexual disorder. In addition to contamination, patients can present with pathologic doubt, somatic obsessions, or obsessions about taboo or symmetry. Among FDA-approved medications, clomipramine might be more effective than selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Exposure response prevention therapy shows better response than pharmacotherapy, but best outcomes are seen with combination therapy. Jon E. Grant, JD, MD, MPH, University of Chicago, also discussed obsessive-compulsive personality disorder, body dysmorphic disorder, hoarding, trichotillomania, and excoriation disorder—as well as changes in DSM-5 that cover this group of disorders.

Patients with schizophrenia are at higher risk of death from cardiac and pulmonary disease than the general population. The quality of care of patients with psychosis generally is poor, because of lack of recognition, time, and resources, as well as systematic barriers to accessing health care. Questions about weight gain, lethargy, infections, and sexual functioning can help the practitioner assess a patient’s general health. When appropriate, Henry A. Nasrallah, MD, St. Louis University School of Medicine, recommends, consider switching antipsychotics, which might reverse adverse metabolic events.

Nonpharmacologic treatment goals include improving sleep, educating patients, providing them with tools for improving sleep, and creating an opportunity for patient-practitioner discussion. Stimulus control and sleep restriction are primary therapeutic techniques to improve sleep quality and reduce non-sleeping time in bed. Thomas Roth, PhD, Henry Ford Hospital, also discussed how to modify sleep hygiene techniques for pediatric, adolescent, and geriatric patients.

Donald W. Black, MD, University of Iowa, says that work groups for DSM-5 were asked to consider dimensionality and culture and gender issues. New diagnostic categories include obsessive-compulsive and related disorders and trauma and stressor-related disorders. Some diagnoses were reformulated or introduced, including autism spectrum disorder and disruptive mood dysregulation disorder. The multi-axial system was discontinued in DSM-5. He also reviewed coding issues.

In a sponsored symposium, Prakash S. Masand, MD, Global Medical Education, Inc., looked at the clinical challenges of addressing all 3 symptom domains that characterize depression (emotional, physical, and cognitive) as an introduction to reviewing the efficacy, mechanism of action, and side effects of vortioxetine (Brintellix), a new serotonergic agent for treating major depressive disorder (MDD). In all studies submitted to the FDA, vortioxetine was found to be superior to placebo, in at least 1 dosage group, for alleviating depressive symptoms and for reducing the risk of depressive recurrence.

AFTERNOON SESSION

Oppositional defiant disorder is more common in boys (onset at age 6 to 10) and is associated with inconsistent and neglectful parenting. Treatment modalities, including educational training, anticonvulsants, and lithium, do not have a strong evidence base. Intermittent explosive disorder is characterized by short-lived but frequent behavioral outbursts and often begins in adolescence. Dr. Grant also reviewed the evidence on conduct disorder, pyromania, and kleptomania.

Cognitive symptoms of schizophrenia often appear before psychotic symptoms and remain stable across the lifespan. There are no pharmacologic treatments for cognitive deficits in schizophrenia; however, Dr. Nasrallah listed tactics to improve cognitive function, including regular aerobic exercise. These cognitive deficits can be categorized as neurocognitive (memory, learning, executive function) and social (social skills, theory of mind, social cues) and contribute to functional decline and often prevent patients from working and going to school. Dr. Nasrallah described how bipolar disorder (BD) overlaps with schizophrenia in terms of cognitive dysfunction.

Henry Nasrallah, MD

Psychiatric disorders exhibit specific sleep/ wake impairments. Sleep disorders can mimic psychiatric symptoms, such as fatigue, cognitive problems, and depression. Sleep disturbances, including insomnia, obstructive sleep apnea, and decreased need for sleep, often coexist with depression, generalized anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and BD, and insomnia is associated with a greater risk of suicide. With antidepressant treatment, sleep in depressed patients improves but does not normalize. Dr. Roth also reviewed pharmacotherapeutic options and non-drug modalities to improve patients’ sleep.

Antidepressants have no efficacy in treating acute episodes of bipolar depression, and using such agents might yield a poor long-term outcome in BD, according to Robert M. Post, MD, George Washington University School of Medicine, Michael J. Ostacher, MD, MPH, MMSc, Stanford University, and Vivek Singh, MD, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, in an interactive faculty discussion. For patients with bipolar I disorder, lithium monotherapy or the combination of lithium and valproate is more effective than valproate alone; evidence does not support valproate as a maintenance treatment. When a patient with BD shows partial response, attendees at this sponsored symposium were advised, consider adding psychotherapy and psycho-education. Combining a mood stabilizer and an antipsychotic might be more effective than monotherapy and safer, by allowing lower dosages. The only 3 treatments FDA-approved for bipolar depression are the olanzapine-fluoxetine combination, quetiapine, and lurasidone.

Boaz Levy, PhD, (left) receives the 2014 George Winokur Research Award from Carol S. North, MD, for his article on recovery of cognitive function in patients with co-occuring bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence.

Friday, March 28, 2014

MORNING SESSION

Carmen Pinto, MD, at a sponsored symposium, reviewed the utility and safety of

long-acting injectable (LAI) antipsychotics for treating schizophrenia, with a focus on LAI aripiprazole, a partial HT-receptor agonist/partial HT-receptor antagonist. Four monthly injections (400 mg/injection) of the drug are needed to reach steady state; each injection reaches peak level in 5 to 7 days. LAI aripiprazole has been shown to delay time to relapse due to nonadherence and onset of nonresponse to the drug, and has high patient acceptance—even in those who already stable. Safety and side effects with LAI aripiprazole are the same as seen with the oral formulation.

In multimodal therapy for chronic pain, psychiatrists have a role in assessing

psychiatric comorbidities, coping ability, social functioning, and other life functions, including work and personal relationships. Cognitive-behavioral therapy can be particularly useful for chronic pain by helping patients reframe their pain experiences. Raphael J. Leo, MA, MD, FAPM, University at Buffalo, reviewed non-opioid co-analgesics that can be used for patients with comorbid pain and a substance use disorder. If opioids are necessary, consider “weak” or long-acting opioids. Monitor patients for aberrant, drug-seeking behavior.

In the second part of his overview, Dr. Black highlighted specific changes to DSM-5 of particular concern to clinicians. New chapters were created and disorders were consolidated, he explained, such as autism spectrum disorder, somatic symptom disorder, and major neurocognitive disorder. New diagnoses include hoarding disorder and binge eating disorder. Subtypes of schizophrenia were dropped. Pathologic gambling was renamed gambling disorder and gender dysphoria is now called gender identity disorder. The bereavement exclusion of a major depressive episode was dropped.

Antidepressants are effective in mitigating pain in neuropathy, headache, fibromyalgia, and chronic musculoskeletal pain, and have been advocated for other pain syndromes. Selection of an antidepressant depends on the type of pain condition, comorbid depression or anxiety, tolerability, and medical comorbidities. Dr. Leo presented prescribing strategies for tricyclics, serotoninnorepinephrine

reuptake inhibitors, SSRIs, and other antidepressants.

Treating of BD in geriatric patients becomes complicated because therapeutic choices are narrowed and response to therapy is less successful with age, according to George T. Grossberg, MD, St. Louis University. Rapid cycling tends to be the norm in geriatric BD patients. Look for agitation and irritability, rather than full-blown mania; grandiose delusions; psychiatric comorbidity, especially anxiety disorder; and sexually inappropriate behavior. Pharmacotherapeutic options include: mood stabilizers, atypical antipsychotics, and antidepressants (specifically, bupropion and SSRIs—not TCAs, venlafaxine, or duloxetine—and over the short term only). Consider divalproex for mania and hypomania, used cautiously because of its adverse side-effect potential.

George T. Grossberg, MD

AFTERNOON SESSION

Often, BD is misdiagnosed as unipolar depression, or the correct diagnosis of BD is delayed, according to Gustavo Alva, MD, ATP Clinical Research. Comorbid substance use disorder or an anxiety disorder is common. Comorbid cardiovascular disease brings a greater risk of mortality in patients with BD than suicide. Approximately two-thirds of patients with BD are taking adjunctive medications; however, antidepressants are no more effective than placebo in treating bipolar depression. At this sponsored symposium, Vladimir Maletic, MD, University of South Carolina, described a 6-week trial in which lurasidone plus lithium or divalporex was more effective in reducing depression, as measured by MADRS, than placebo plus lithium or akathisia, somnolence, and extrapyramidal symptoms.

When assessing an older patient with psychosis, first establish the cause of the symptoms, such as Alzheimer’s disease, affective disorder, substance use, or hallucinations associated with grief. Older patients with schizophrenia who have been taking typical antipsychotics for years might benefit from a switch to an atypical or a dosage reduction. Dr. Grossberg recommends considering antipsychotics for older patients when symptoms cause severe emotional distress that does not respond to other interventions or an acute episode that poses a safety risk for patients or others. Choose an antipsychotic based on side effects, and “start low and go slow,” when possible. The goal is to reduce agitation and distress—not necessarily to resolve psychotic symptoms.

Anita H. Clayton, MD, University of Virginia Health System, provided a review of sexual function from puberty through midlife and older years. Social factors play a role in sexual satisfaction, such as gender expectations, religious beliefs, and the influence of reporting in the media. Sexual dysfunction becomes worse in men after age 29; in women, the rate of sexual dysfunction appears to be consistent across the lifespan. Cardiovascular disease is a significant risk factor for sexual dysfunction in men, but not in women. Sexual function and depression have a bidirectional relationship; sexual dysfunction may be a symptom or cause of depression and antidepressants may affect desire and function. Medications, including psychotropics, oral contraceptives, and opioids, can cause sexual dysfunction.