User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Sleep terrors in adults: How to help control this potentially dangerous condition

Sleep terrors (STs)—also known as night terrors—are characterized by sudden arousal accompanied by a piercing scream or cry in the first few hours after falling asleep. These parasomnias arise out of slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4 of nonrapid eye movement [non-REM] sleep) and affect approximately 5% of adults.1 The condition is twice as common in men than women, and usually affects children but may not develop until adulthood.1

During STs, a patient may act scared, afraid, agitated, anxious, or panicky without being fully aware of his or her surroundings. The episode may last 30 seconds to 5 minutes; most patients don’t remember the event the next morning. STs may leave individuals feeling exhausted and perplexed the next day. Verbalization during the episode is incoherent and a patient’s perception of the environment seems altered. Tachycardia, tachypnea, sweating, flushed skin, or mydriasis are prominent. When ST patients walk, they may do so violently and can cause harm to themselves or others.

The differential diagnosis of STs includes posttraumatic stress disorder; nocturnal seizures characterized by excessive motor activity and organic CNS lesions; REM sleep behavior disorder; sleep choking syndrome; and nocturnal panic attacks. Patients with STs report high rates of stressful events—eg, divorce or bereavement—in the previous year. They are more likely to have a history of mood and anxiety disorders and high levels of depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive and phobic traits. One study found patients with STs were 4.3 times more likely to have had a car accident in the past year.2

Evaluating and treating STs

Rule out comorbid conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder. Encourage your patient to improve his or her sleep hygiene by maintaining a regular sleep/wake cycle, exercising, and limiting caffeine and alcohol and exposure to bright light before bedtime.

Self-help techniques. To avoid injury, encourage your patient to remove dangerous objects from their sleeping area. Suggest locking the doors to the room or home, and putting medications in a secure place. Patients also may consider keeping their mattress close to the floor to limit the risk of injury.

Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Along with counseling and support, your patient may benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, or hypnosis.3 Anticipatory arousal therapy may help by interrupting the altered underlying electrophysiology of partial arousal.

If your patient is concerned about physical injury during STs, consider prescribing clonazepam, temazepam, or diazepam.4 Trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine5 also have been used to treat STs.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Crisp AH. The sleepwalking/night terrors syndrome in adults. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72(852):599-604.

2. Oudiette D, Leu S, Pottier M, et al. Dreamlike mentations during sleepwalking and sleep terrors in adults. Sleep. 2009;32(12):1621-1627.

3. Lowe P, Humphreys C, Williams SJ. Night terrors: women’s experiences of (not) sleeping where there is domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(6):549-561.

4. Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Long-term nightly benzodiazepine treatment of injurious parasomnias and other disorders of disrupted nocturnal sleep in 170 adults. Am J Med. 1996;100(3):333-337.

5. Lillywhite AR, Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ. Successful treatment of night terrors and somnambulism with paroxetine. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(4):551-554.

Sleep terrors (STs)—also known as night terrors—are characterized by sudden arousal accompanied by a piercing scream or cry in the first few hours after falling asleep. These parasomnias arise out of slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4 of nonrapid eye movement [non-REM] sleep) and affect approximately 5% of adults.1 The condition is twice as common in men than women, and usually affects children but may not develop until adulthood.1

During STs, a patient may act scared, afraid, agitated, anxious, or panicky without being fully aware of his or her surroundings. The episode may last 30 seconds to 5 minutes; most patients don’t remember the event the next morning. STs may leave individuals feeling exhausted and perplexed the next day. Verbalization during the episode is incoherent and a patient’s perception of the environment seems altered. Tachycardia, tachypnea, sweating, flushed skin, or mydriasis are prominent. When ST patients walk, they may do so violently and can cause harm to themselves or others.

The differential diagnosis of STs includes posttraumatic stress disorder; nocturnal seizures characterized by excessive motor activity and organic CNS lesions; REM sleep behavior disorder; sleep choking syndrome; and nocturnal panic attacks. Patients with STs report high rates of stressful events—eg, divorce or bereavement—in the previous year. They are more likely to have a history of mood and anxiety disorders and high levels of depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive and phobic traits. One study found patients with STs were 4.3 times more likely to have had a car accident in the past year.2

Evaluating and treating STs

Rule out comorbid conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder. Encourage your patient to improve his or her sleep hygiene by maintaining a regular sleep/wake cycle, exercising, and limiting caffeine and alcohol and exposure to bright light before bedtime.

Self-help techniques. To avoid injury, encourage your patient to remove dangerous objects from their sleeping area. Suggest locking the doors to the room or home, and putting medications in a secure place. Patients also may consider keeping their mattress close to the floor to limit the risk of injury.

Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Along with counseling and support, your patient may benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, or hypnosis.3 Anticipatory arousal therapy may help by interrupting the altered underlying electrophysiology of partial arousal.

If your patient is concerned about physical injury during STs, consider prescribing clonazepam, temazepam, or diazepam.4 Trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine5 also have been used to treat STs.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Sleep terrors (STs)—also known as night terrors—are characterized by sudden arousal accompanied by a piercing scream or cry in the first few hours after falling asleep. These parasomnias arise out of slow-wave sleep (stages 3 and 4 of nonrapid eye movement [non-REM] sleep) and affect approximately 5% of adults.1 The condition is twice as common in men than women, and usually affects children but may not develop until adulthood.1

During STs, a patient may act scared, afraid, agitated, anxious, or panicky without being fully aware of his or her surroundings. The episode may last 30 seconds to 5 minutes; most patients don’t remember the event the next morning. STs may leave individuals feeling exhausted and perplexed the next day. Verbalization during the episode is incoherent and a patient’s perception of the environment seems altered. Tachycardia, tachypnea, sweating, flushed skin, or mydriasis are prominent. When ST patients walk, they may do so violently and can cause harm to themselves or others.

The differential diagnosis of STs includes posttraumatic stress disorder; nocturnal seizures characterized by excessive motor activity and organic CNS lesions; REM sleep behavior disorder; sleep choking syndrome; and nocturnal panic attacks. Patients with STs report high rates of stressful events—eg, divorce or bereavement—in the previous year. They are more likely to have a history of mood and anxiety disorders and high levels of depression, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive and phobic traits. One study found patients with STs were 4.3 times more likely to have had a car accident in the past year.2

Evaluating and treating STs

Rule out comorbid conditions such as obstructive sleep apnea and periodic limb movement disorder. Encourage your patient to improve his or her sleep hygiene by maintaining a regular sleep/wake cycle, exercising, and limiting caffeine and alcohol and exposure to bright light before bedtime.

Self-help techniques. To avoid injury, encourage your patient to remove dangerous objects from their sleeping area. Suggest locking the doors to the room or home, and putting medications in a secure place. Patients also may consider keeping their mattress close to the floor to limit the risk of injury.

Pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy. Along with counseling and support, your patient may benefit from cognitive-behavioral therapy, relaxation therapy, or hypnosis.3 Anticipatory arousal therapy may help by interrupting the altered underlying electrophysiology of partial arousal.

If your patient is concerned about physical injury during STs, consider prescribing clonazepam, temazepam, or diazepam.4 Trazodone and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors such as paroxetine5 also have been used to treat STs.

Disclosure

Dr. Jain reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Crisp AH. The sleepwalking/night terrors syndrome in adults. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72(852):599-604.

2. Oudiette D, Leu S, Pottier M, et al. Dreamlike mentations during sleepwalking and sleep terrors in adults. Sleep. 2009;32(12):1621-1627.

3. Lowe P, Humphreys C, Williams SJ. Night terrors: women’s experiences of (not) sleeping where there is domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(6):549-561.

4. Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Long-term nightly benzodiazepine treatment of injurious parasomnias and other disorders of disrupted nocturnal sleep in 170 adults. Am J Med. 1996;100(3):333-337.

5. Lillywhite AR, Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ. Successful treatment of night terrors and somnambulism with paroxetine. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(4):551-554.

1. Crisp AH. The sleepwalking/night terrors syndrome in adults. Postgrad Med J. 1996;72(852):599-604.

2. Oudiette D, Leu S, Pottier M, et al. Dreamlike mentations during sleepwalking and sleep terrors in adults. Sleep. 2009;32(12):1621-1627.

3. Lowe P, Humphreys C, Williams SJ. Night terrors: women’s experiences of (not) sleeping where there is domestic violence. Violence Against Women. 2007;13(6):549-561.

4. Schenck CH, Mahowald MW. Long-term nightly benzodiazepine treatment of injurious parasomnias and other disorders of disrupted nocturnal sleep in 170 adults. Am J Med. 1996;100(3):333-337.

5. Lillywhite AR, Wilson SJ, Nutt DJ. Successful treatment of night terrors and somnambulism with paroxetine. Br J Psychiatry. 1994;164(4):551-554.

Omega-3 fatty acids for psychiatric illness

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Epidemiologic data suggest that people who consume diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids (FAs)—long-chain polyunsaturated FAs such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)—have a decreased risk of major depressive disorder (MDD), postpartum depression, and bipolar disorder (BD).1-5 Omega-3 FA concentration may impact serotonin and dopamine transmission via effects on cell membrane fluidity.6 Therefore, decreased intake may increase the risk of several psychiatric disorders. As the average Western diet has changed over the last 2 centuries, omega-3 FA consumption has decreased.7 Omega-3 FAs cannot be synthesized by the body and must come from exogenous sources, such as fish and nuts. For a discussion of different types of dietary fats, see Box 1.8

Should we advise our patients to increase their omega-3 FA consumption? The American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommend omega-3 FA consumption for the general population and in some cases, supplementation for specific disorders (Box 2).9-12 New data has been published since Current Psychiatry last reviewed the evidence for using omega-3 FAs for psychiatric conditions in 2004.8 This article looks at the latest evidence on the use of omega-3 FAs to treat mood disorders, schizophrenia, dementia, and other psychiatric conditions.

Dietary fat is saturated or unsaturated. Unsaturated fats are further categorized as monounsaturated or polyunsaturated (PUFA). PUFAs contain a hydrocarbon chain with ≥2 double bonds.8 The position of this double bond relative to the methyl end carbon—or “omega” carbon—groups the PUFAs into 2 categories:8

- omega-6 fatty acids, including arachidonic acid (AA) and linoleic acid (LA)

- omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). ALA is a metabolic precursor to EPA and DHA.

PUFAs—in particular AA and DHA—are thought to contribute to cell membrane fluidity, modulation of neurotransmitters, and signal transduction pathways. As precursors to eicosanoids and cytokines, PUFAs may affect anti-inflammatory response systems.

Consumption of omega-3 fatty acids (FAs) reduces risk for arrhythmia, thrombosis, and atherosclerotic plaque, according to American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines. Omega-3 FA intake also may improve endothelial function, slightly lower blood pressure, and reduce inflammatory response. Replacing dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat reduces coronary heart disease risk by 19%.9 The AHA recommends that all adults eat fish, particularly oily fish such as salmon or tuna, ≥2 times per week. Patients with documented coronary heart disease should consume 1 g/d eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) combined10 either via oily fish or omega-3 FA capsules. Side effects of omega-3 FA supplements are minor and include mild gastrointestinal discomfort, mostly burping or an unpleasant aftertaste; no cases of bleeding have been reported.11

For patients with hypertriglyceridemia, 2 to 4 g/d may be useful. Because of a theoretical risk of bleeding, doses >3 g/d should be supervised by a physician.

Because psychiatric illnesses and cardiovascular disease may be comorbid, the Omega-3 FA Subcommittee of the American Psychiatric Association supports the AHA’s guidelines regarding fish consumption, and further recommends that patients with mood, impulse control, or psychotic disorders consume ≥1 g/d of combined EPA and DHA.12

Limitations of the data

Reviewing the literature on omega-3 FAs to treat psychiatric disorders is hampered by several difficulties:13

- studies may evaluate the use of EPA alone, EPA combined with DHA, or DHA alone

- the doses of EPA and DHA and ratio of EPA to DHA of the supplements used in clinical trials varies greatly

- patients’ dietary consumption of omega-3 FAs is difficult to control

- DSM diagnostic criteria, as well as severity of illness, differ within studies.

In addition, studies may use omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or as adjuncts. All of these factors lead to difficulty interpreting the literature, as well as trouble in extracting data for meta-analysis.

Omega-3 FAs for mood disorders

MDD and other depressive diagnoses. Several meta-analyses examining the use of omega-3 FAs for treating depressive disorders have had equivocal findings. Variability in results might be partially explained by differences in the severity of baseline depression among diverse study populations, diagnostic variation, differing omega-3 supplementation protocols, or other issues.13 In addition, publication bias also may affect results.

In a 2011 literature review and meta-analysis of omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or an adjunct to antidepressants to treat MDD, Bloch and Hannestad6 concluded that omega-3 FAs offer a small but nonsignificant benefit in treating MDD. This review suggested that omega-3 FAs may be more effective in patients with more severe depression. The effects of varying levels of EPA vs DHA were not examined.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Appleton et al14 concluded that omega-3 FA supplements have little beneficial effect on depressed mood in individuals who do not have a depressive illness diagnosis (eg, MDD). However, this study did not consider the differential effects of EPA vs DHA on treatment response. Patients diagnosed with a depressive illness received greater benefits from omega-3 FA supplementation, although the patients in this study were heterogeneous. Similar to Bloch and Hannestad, Appleton et al14 found that omega-3 FA supplementation may be most beneficial for depressed patients with more severe symptoms, but is unlikely to help those with mild-to-moderate symptoms or individuals without symptoms who aim to prevent depression.

A meta-analysis by Martins15 looked at EPA vs DHA to treat depressive illness and found that only supplements that were mostly or completely EPA effectively treated depressive symptoms. Martins also found that severity of illness is key for positive treatment outcomes; there was a significant relationship between higher baseline depression levels and efficacy.15 Martins noted that omega-3 FA therapy was more effective as a treatment than a preventive strategy, and that adding omega-3 FAs to antidepressants was more efficacious than omega-3 FAs alone.15

A meta-analysis of clinical trials of omega-3 FAs for depressive illness suggested EPA should be ≥60% of total EPA + DHA.16

BD. A recent meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that adding omega-3 supplements to mood stabilizers in patients with BD was associated with a statistically significant reduction of depressive symptoms, but was not effective for treating mania.17 The authors suggested patients with BD—especially those with comorbid cardiovascular or metabolic conditions— increase their dietary consumption of foods containing omega-3 FAs (Table)18 and, if necessary, take a supplement of 1 to 1.5 g/d of mixed EPA and DHA, with a higher ratio of EPA.19 See Box 3 for a box on how to read omega-3 supplement labels.

In a small RCT of 51 children and adolescents (age 6 to 17) with symptomatic bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, supplementation with flax oil (alpha-linolenic acid, a polyunsaturated omega-3 FA that is a precursor to EPA and DHA) did not affect symptoms as measured by several rating scales.20

Perinatal and postpartum depression. Omega-3 FAs are considered a safe treatment for depressive disorders during pregnancy because they provide neurodevelopmental benefits for neonates and have few contraindications during pregnancy.21 RCTs of omega-3 FA monotherapy for perinatal depression have been small (≤51 patients) and produced mixed findings.21 A pilot study (N = 16) of patients with postpartum depression found a significant decrease in depressive symptoms with EPA treatment.22 More research is needed before omega-3 FA supplementation can be recommended during pregnancy.

Table

Foods with healthy fats: From best to worst

| Polyunsaturated fats | Omega-3 | Fish-based: oily fish, including salmon, tuna, mackerel, lake trout, herring, and sardines Plant-based: tofu and other forms of soybeans; walnuts and flaxseed and their oils, and canola oil |

| Omega-6 | Only available in plant-based form: corn, soy, and safflower oil | |

| Monosaturated fats | Olive and peanut oil | |

| Saturated fats | Red meats, high-fat dairy, and partially hydrogenated oils | |

| Source: Reference 18 | ||

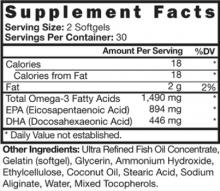

Because nutritional supplements vary, advise patients to look at the supplement facts on the back of a bottle of omega-3 fatty acids. The American Psychiatric Association recommends patients take a total eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) of 1 g/d; EPA should be ≥60% of total EPA + DHA.

This image is an example of a label that would meet the appropriate criteria. Total EPA + DHA = 1,490 mg and EPA is 60% of this combined total.

Source: Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1577-1584

Schizophrenia

In a Cochrane review of 8 studies of patients with schizophrenia, adjunctive treatment with omega-3 FAs led to >25% reduction in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, but this improvement was not statistically significant.23 Omega-3 FAs did not decrease tardive dyskinesia symptoms as measured by the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. The authors stated that results were inconclusive, and use of omega-3 FAs in patients with schizophrenia remains experimental. In a separate meta-analysis that included 335 patients with schizophrenia, EPA augmentation had no beneficial effect on psychotic symptoms.24

In a double-blind RCT of 81 adolescents and young adults (age 13 to 25) at ultra-high risk of psychotic illness, 5% of patients who received 1.2 g/d of omega-3 FAs developed a psychotic disorder compared with 28% of patients receiving placebo.25 The authors concluded that supplementation with omega-3 FAs may be a safe and effective strategy for young patients with subthreshold psychotic symptoms.

Dementia

Studies evaluating the relationship between omega-3 FAs and dementia risk have revealed mixed findings.26,27 In a pilot study of 10 geriatric patients with moderately severe dementia related to thrombotic cerebrovascular disorder, DHA supplementation led to improved Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores compared with controls.28 In another study, administering EPA to 64 patients with Alzheimer’s disease significantly improved MMSE scores, with maximum improvement at 3 months, but this benefit dissipated after 6 months of treatment.29 In a study of 22 patients with various types of dementia, Suzuki et al30 found that DHA supplementation improved scores on a Japanese dementia scale. These studies show promise, but more evidence is necessary before recommendations can be made.

Other psychiatric disorders

Omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or an adjunct to psychostimulants does not seem to improve symptoms in children who meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).31-33 Studies of omega-3 FAs as treatment for anxiety and personality disorders are limited. To date, omega-3 FAs as adjunctive treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and monotherapy in borderline personality disorder have not shown efficacy.34,35

Using omega-3 FAs in practice

Based on new data and several recent meta-analyses, clinical recommendations have emerged. Sarris et al17 suggested patients with BD increase dietary intake of omega-3 FAs or take a supplement with 1 to 1.5 g/d of mixed EPA and DHA (with a higher ratio of EPA). In MDD, the type of omega-3 FA supplementation seems to be important; EPA seems to be the primary component for efficacy.15,19 Additionally, the more severe the depression, the more likely symptoms will respond to omega-3 FAs.6,14,15 Omega-3 FAs are not effective at preventing depression14,15 and evidence is equivocal for treating perinatal depression.21 Omega-3 FA supplementation has not shown efficacy for patients with schizophrenia,23,24 although it may prevent transition to psychosis in adolescents and young adults at ultra-high risk for a psychotic disorder.25 Data examining omega-3 FA supplementation in postpartum depression22 and dementia28,29 are limited but show promise. Omega-3 FAs appear to lack efficacy in ADHD,31-33 OCD,34 and borderline personality disorder.35

Related Resources

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Omega-3 fatty acids. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/omega3.

- National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. Working group report: Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. http://ods.od.nih.gov/Health_Information/omega_3_fatty_acids.aspx.

Disclosure

Dr. Morreale reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hibbeln JR. Fish consumption and major depression. Lancet. 1998;351(9110):1213.-

2. Tanskanen A, Hibbeln JR, Tuomilehto J, et al. Fish consumption and depressive symptoms in the general population in Finland. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(4):529-531.

3. Silvers KM, Scott KM. Fish consumption and self-reported physical and mental health status. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(3):427-431.

4. Timonen M, Horrobin DF, Jokelaienen J, et al. Fish consumption and depression: the northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(3):447-452.

5. Freeman MP, Rapaport MH. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: from cellular mechanisms to clinical care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(2):258-259.

6. Bloch MH, Hannestad J. Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of depression: systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print September 20 2011]. Mol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.100.

7. Parker G, Gibson NA, Brotchie H, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):969-978.

8. Martinez JM, Marangell LB. Omega-3 fatty acids: do ‘fish oils’ have a therapeutic role in psychiatry? Current Psychiatry. 2004;3(1):25-52.

9. Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects of coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000252.-

10. Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. AHA Nutrition Committee. American Heart Association. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: new recommendations from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(2):151-152.

11. Freeman MP, Fava M, Lake J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in major depressive disorder: the American Psychiatric Association Task Force report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):669-681.

12. Freeman MP, Hibbeln J, Wisner KL, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence basis for treatment and future research in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(12):1954-1967.

13. Mischoulon D. The impact of omega-3 fatty acids on depressive disorders and suicidality: can we reconcile 2 studies with seemingly contradictory results? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1574-1576.

14. Appleton KM, Rogers PJ, Andrew RN. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on depressed mood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(31):757-770.

15. Martins JG. EPA but not DHA appears to be responsible for the efficacy of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28(5):525-542.

16. Young G, Conquer J. Omega-3 fatty acids and neuropsychiatric disorders. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2005;45(1):1-28.

17. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

18. Sacks F. Ask the expert: omega-3 fatty acids. The Nutrition Source.http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/questions/omega-3/index.html. Accessed July 23 2012.

19. Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1577-1584.

20. Gracious BL, Chirieac MC, Costescu S, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of flax oil in pediatric bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(2):142-154.

21. Freeman MP. Omega-3 fatty acids in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 5):7-11.

22. Freeman MP, Hibbeln JR, Wisner KL, et al. Randomized dose-ranging pilot trial of omega-3 fatty acids for postpartum depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):31-35.

23. Joy CB, Mumby-Croft R, Joy LA. Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD001257.-

24. Fusar-Poli P, Berger G. Eicosapentaenoic acid interventions in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(2):179-185.

25. Amminger GP, Schäfer MR, Papageorgiou K, et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):146-154.

26. Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, et al. Consumption of fish and n-3 fatty acids and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(7):940-946.

27. Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, et al. Diet and risk of dementia: does fat matter? The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1915-1921.

28. Terano T, Fujishiro S, Ban T, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation improves the moderately severe dementia from thrombotic cerebrovascular diseases. Lipids. 1999;34 suppl:S345-S346.

29. Otsuka M. Analysis of dietary factors in Alzheimer’s disease: clinical use of nutritional intervention for prevention and treatment of dementia [in Japanese]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2000;37(12):970-973.

30. Suzuki H, Morikawa Y, Takahashi H. Effect of DHA oil supplementation in intelligence and visual acuity in the elderly. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2001;88:68-71.

31. Joshi K, Lad S, Kale M, et al. Supplementation with flax oil and vitamin C improves the outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;74(1):17-21.

32. Voigt RG, Llorente AM, Jensen CL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr. 2001;139(2):189-196.

33. Hirayama S, Hamazaki T, Terasawa K. Effect of docosahexaenoic acid-containing food administration on symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(3):467-473.

34. Fux M, Benjamin J, Nemets B. A placebo-controlled cross-over trial of adjunctive EPA in OCD. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38(3):323-325.

35. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Omega-3 Fatty acid treatment of women with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):167-169.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Epidemiologic data suggest that people who consume diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids (FAs)—long-chain polyunsaturated FAs such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)—have a decreased risk of major depressive disorder (MDD), postpartum depression, and bipolar disorder (BD).1-5 Omega-3 FA concentration may impact serotonin and dopamine transmission via effects on cell membrane fluidity.6 Therefore, decreased intake may increase the risk of several psychiatric disorders. As the average Western diet has changed over the last 2 centuries, omega-3 FA consumption has decreased.7 Omega-3 FAs cannot be synthesized by the body and must come from exogenous sources, such as fish and nuts. For a discussion of different types of dietary fats, see Box 1.8

Should we advise our patients to increase their omega-3 FA consumption? The American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommend omega-3 FA consumption for the general population and in some cases, supplementation for specific disorders (Box 2).9-12 New data has been published since Current Psychiatry last reviewed the evidence for using omega-3 FAs for psychiatric conditions in 2004.8 This article looks at the latest evidence on the use of omega-3 FAs to treat mood disorders, schizophrenia, dementia, and other psychiatric conditions.

Dietary fat is saturated or unsaturated. Unsaturated fats are further categorized as monounsaturated or polyunsaturated (PUFA). PUFAs contain a hydrocarbon chain with ≥2 double bonds.8 The position of this double bond relative to the methyl end carbon—or “omega” carbon—groups the PUFAs into 2 categories:8

- omega-6 fatty acids, including arachidonic acid (AA) and linoleic acid (LA)

- omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). ALA is a metabolic precursor to EPA and DHA.

PUFAs—in particular AA and DHA—are thought to contribute to cell membrane fluidity, modulation of neurotransmitters, and signal transduction pathways. As precursors to eicosanoids and cytokines, PUFAs may affect anti-inflammatory response systems.

Consumption of omega-3 fatty acids (FAs) reduces risk for arrhythmia, thrombosis, and atherosclerotic plaque, according to American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines. Omega-3 FA intake also may improve endothelial function, slightly lower blood pressure, and reduce inflammatory response. Replacing dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat reduces coronary heart disease risk by 19%.9 The AHA recommends that all adults eat fish, particularly oily fish such as salmon or tuna, ≥2 times per week. Patients with documented coronary heart disease should consume 1 g/d eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) combined10 either via oily fish or omega-3 FA capsules. Side effects of omega-3 FA supplements are minor and include mild gastrointestinal discomfort, mostly burping or an unpleasant aftertaste; no cases of bleeding have been reported.11

For patients with hypertriglyceridemia, 2 to 4 g/d may be useful. Because of a theoretical risk of bleeding, doses >3 g/d should be supervised by a physician.

Because psychiatric illnesses and cardiovascular disease may be comorbid, the Omega-3 FA Subcommittee of the American Psychiatric Association supports the AHA’s guidelines regarding fish consumption, and further recommends that patients with mood, impulse control, or psychotic disorders consume ≥1 g/d of combined EPA and DHA.12

Limitations of the data

Reviewing the literature on omega-3 FAs to treat psychiatric disorders is hampered by several difficulties:13

- studies may evaluate the use of EPA alone, EPA combined with DHA, or DHA alone

- the doses of EPA and DHA and ratio of EPA to DHA of the supplements used in clinical trials varies greatly

- patients’ dietary consumption of omega-3 FAs is difficult to control

- DSM diagnostic criteria, as well as severity of illness, differ within studies.

In addition, studies may use omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or as adjuncts. All of these factors lead to difficulty interpreting the literature, as well as trouble in extracting data for meta-analysis.

Omega-3 FAs for mood disorders

MDD and other depressive diagnoses. Several meta-analyses examining the use of omega-3 FAs for treating depressive disorders have had equivocal findings. Variability in results might be partially explained by differences in the severity of baseline depression among diverse study populations, diagnostic variation, differing omega-3 supplementation protocols, or other issues.13 In addition, publication bias also may affect results.

In a 2011 literature review and meta-analysis of omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or an adjunct to antidepressants to treat MDD, Bloch and Hannestad6 concluded that omega-3 FAs offer a small but nonsignificant benefit in treating MDD. This review suggested that omega-3 FAs may be more effective in patients with more severe depression. The effects of varying levels of EPA vs DHA were not examined.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Appleton et al14 concluded that omega-3 FA supplements have little beneficial effect on depressed mood in individuals who do not have a depressive illness diagnosis (eg, MDD). However, this study did not consider the differential effects of EPA vs DHA on treatment response. Patients diagnosed with a depressive illness received greater benefits from omega-3 FA supplementation, although the patients in this study were heterogeneous. Similar to Bloch and Hannestad, Appleton et al14 found that omega-3 FA supplementation may be most beneficial for depressed patients with more severe symptoms, but is unlikely to help those with mild-to-moderate symptoms or individuals without symptoms who aim to prevent depression.

A meta-analysis by Martins15 looked at EPA vs DHA to treat depressive illness and found that only supplements that were mostly or completely EPA effectively treated depressive symptoms. Martins also found that severity of illness is key for positive treatment outcomes; there was a significant relationship between higher baseline depression levels and efficacy.15 Martins noted that omega-3 FA therapy was more effective as a treatment than a preventive strategy, and that adding omega-3 FAs to antidepressants was more efficacious than omega-3 FAs alone.15

A meta-analysis of clinical trials of omega-3 FAs for depressive illness suggested EPA should be ≥60% of total EPA + DHA.16

BD. A recent meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that adding omega-3 supplements to mood stabilizers in patients with BD was associated with a statistically significant reduction of depressive symptoms, but was not effective for treating mania.17 The authors suggested patients with BD—especially those with comorbid cardiovascular or metabolic conditions— increase their dietary consumption of foods containing omega-3 FAs (Table)18 and, if necessary, take a supplement of 1 to 1.5 g/d of mixed EPA and DHA, with a higher ratio of EPA.19 See Box 3 for a box on how to read omega-3 supplement labels.

In a small RCT of 51 children and adolescents (age 6 to 17) with symptomatic bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, supplementation with flax oil (alpha-linolenic acid, a polyunsaturated omega-3 FA that is a precursor to EPA and DHA) did not affect symptoms as measured by several rating scales.20

Perinatal and postpartum depression. Omega-3 FAs are considered a safe treatment for depressive disorders during pregnancy because they provide neurodevelopmental benefits for neonates and have few contraindications during pregnancy.21 RCTs of omega-3 FA monotherapy for perinatal depression have been small (≤51 patients) and produced mixed findings.21 A pilot study (N = 16) of patients with postpartum depression found a significant decrease in depressive symptoms with EPA treatment.22 More research is needed before omega-3 FA supplementation can be recommended during pregnancy.

Table

Foods with healthy fats: From best to worst

| Polyunsaturated fats | Omega-3 | Fish-based: oily fish, including salmon, tuna, mackerel, lake trout, herring, and sardines Plant-based: tofu and other forms of soybeans; walnuts and flaxseed and their oils, and canola oil |

| Omega-6 | Only available in plant-based form: corn, soy, and safflower oil | |

| Monosaturated fats | Olive and peanut oil | |

| Saturated fats | Red meats, high-fat dairy, and partially hydrogenated oils | |

| Source: Reference 18 | ||

Because nutritional supplements vary, advise patients to look at the supplement facts on the back of a bottle of omega-3 fatty acids. The American Psychiatric Association recommends patients take a total eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) of 1 g/d; EPA should be ≥60% of total EPA + DHA.

This image is an example of a label that would meet the appropriate criteria. Total EPA + DHA = 1,490 mg and EPA is 60% of this combined total.

Source: Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1577-1584

Schizophrenia

In a Cochrane review of 8 studies of patients with schizophrenia, adjunctive treatment with omega-3 FAs led to >25% reduction in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, but this improvement was not statistically significant.23 Omega-3 FAs did not decrease tardive dyskinesia symptoms as measured by the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. The authors stated that results were inconclusive, and use of omega-3 FAs in patients with schizophrenia remains experimental. In a separate meta-analysis that included 335 patients with schizophrenia, EPA augmentation had no beneficial effect on psychotic symptoms.24

In a double-blind RCT of 81 adolescents and young adults (age 13 to 25) at ultra-high risk of psychotic illness, 5% of patients who received 1.2 g/d of omega-3 FAs developed a psychotic disorder compared with 28% of patients receiving placebo.25 The authors concluded that supplementation with omega-3 FAs may be a safe and effective strategy for young patients with subthreshold psychotic symptoms.

Dementia

Studies evaluating the relationship between omega-3 FAs and dementia risk have revealed mixed findings.26,27 In a pilot study of 10 geriatric patients with moderately severe dementia related to thrombotic cerebrovascular disorder, DHA supplementation led to improved Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores compared with controls.28 In another study, administering EPA to 64 patients with Alzheimer’s disease significantly improved MMSE scores, with maximum improvement at 3 months, but this benefit dissipated after 6 months of treatment.29 In a study of 22 patients with various types of dementia, Suzuki et al30 found that DHA supplementation improved scores on a Japanese dementia scale. These studies show promise, but more evidence is necessary before recommendations can be made.

Other psychiatric disorders

Omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or an adjunct to psychostimulants does not seem to improve symptoms in children who meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).31-33 Studies of omega-3 FAs as treatment for anxiety and personality disorders are limited. To date, omega-3 FAs as adjunctive treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and monotherapy in borderline personality disorder have not shown efficacy.34,35

Using omega-3 FAs in practice

Based on new data and several recent meta-analyses, clinical recommendations have emerged. Sarris et al17 suggested patients with BD increase dietary intake of omega-3 FAs or take a supplement with 1 to 1.5 g/d of mixed EPA and DHA (with a higher ratio of EPA). In MDD, the type of omega-3 FA supplementation seems to be important; EPA seems to be the primary component for efficacy.15,19 Additionally, the more severe the depression, the more likely symptoms will respond to omega-3 FAs.6,14,15 Omega-3 FAs are not effective at preventing depression14,15 and evidence is equivocal for treating perinatal depression.21 Omega-3 FA supplementation has not shown efficacy for patients with schizophrenia,23,24 although it may prevent transition to psychosis in adolescents and young adults at ultra-high risk for a psychotic disorder.25 Data examining omega-3 FA supplementation in postpartum depression22 and dementia28,29 are limited but show promise. Omega-3 FAs appear to lack efficacy in ADHD,31-33 OCD,34 and borderline personality disorder.35

Related Resources

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Omega-3 fatty acids. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/omega3.

- National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. Working group report: Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. http://ods.od.nih.gov/Health_Information/omega_3_fatty_acids.aspx.

Disclosure

Dr. Morreale reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Epidemiologic data suggest that people who consume diets rich in omega-3 fatty acids (FAs)—long-chain polyunsaturated FAs such as eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)—have a decreased risk of major depressive disorder (MDD), postpartum depression, and bipolar disorder (BD).1-5 Omega-3 FA concentration may impact serotonin and dopamine transmission via effects on cell membrane fluidity.6 Therefore, decreased intake may increase the risk of several psychiatric disorders. As the average Western diet has changed over the last 2 centuries, omega-3 FA consumption has decreased.7 Omega-3 FAs cannot be synthesized by the body and must come from exogenous sources, such as fish and nuts. For a discussion of different types of dietary fats, see Box 1.8

Should we advise our patients to increase their omega-3 FA consumption? The American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the American Heart Association (AHA) recommend omega-3 FA consumption for the general population and in some cases, supplementation for specific disorders (Box 2).9-12 New data has been published since Current Psychiatry last reviewed the evidence for using omega-3 FAs for psychiatric conditions in 2004.8 This article looks at the latest evidence on the use of omega-3 FAs to treat mood disorders, schizophrenia, dementia, and other psychiatric conditions.

Dietary fat is saturated or unsaturated. Unsaturated fats are further categorized as monounsaturated or polyunsaturated (PUFA). PUFAs contain a hydrocarbon chain with ≥2 double bonds.8 The position of this double bond relative to the methyl end carbon—or “omega” carbon—groups the PUFAs into 2 categories:8

- omega-6 fatty acids, including arachidonic acid (AA) and linoleic acid (LA)

- omega-3 fatty acids, including eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and alpha-linolenic acid (ALA). ALA is a metabolic precursor to EPA and DHA.

PUFAs—in particular AA and DHA—are thought to contribute to cell membrane fluidity, modulation of neurotransmitters, and signal transduction pathways. As precursors to eicosanoids and cytokines, PUFAs may affect anti-inflammatory response systems.

Consumption of omega-3 fatty acids (FAs) reduces risk for arrhythmia, thrombosis, and atherosclerotic plaque, according to American Heart Association (AHA) guidelines. Omega-3 FA intake also may improve endothelial function, slightly lower blood pressure, and reduce inflammatory response. Replacing dietary saturated fat with polyunsaturated fat reduces coronary heart disease risk by 19%.9 The AHA recommends that all adults eat fish, particularly oily fish such as salmon or tuna, ≥2 times per week. Patients with documented coronary heart disease should consume 1 g/d eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) combined10 either via oily fish or omega-3 FA capsules. Side effects of omega-3 FA supplements are minor and include mild gastrointestinal discomfort, mostly burping or an unpleasant aftertaste; no cases of bleeding have been reported.11

For patients with hypertriglyceridemia, 2 to 4 g/d may be useful. Because of a theoretical risk of bleeding, doses >3 g/d should be supervised by a physician.

Because psychiatric illnesses and cardiovascular disease may be comorbid, the Omega-3 FA Subcommittee of the American Psychiatric Association supports the AHA’s guidelines regarding fish consumption, and further recommends that patients with mood, impulse control, or psychotic disorders consume ≥1 g/d of combined EPA and DHA.12

Limitations of the data

Reviewing the literature on omega-3 FAs to treat psychiatric disorders is hampered by several difficulties:13

- studies may evaluate the use of EPA alone, EPA combined with DHA, or DHA alone

- the doses of EPA and DHA and ratio of EPA to DHA of the supplements used in clinical trials varies greatly

- patients’ dietary consumption of omega-3 FAs is difficult to control

- DSM diagnostic criteria, as well as severity of illness, differ within studies.

In addition, studies may use omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or as adjuncts. All of these factors lead to difficulty interpreting the literature, as well as trouble in extracting data for meta-analysis.

Omega-3 FAs for mood disorders

MDD and other depressive diagnoses. Several meta-analyses examining the use of omega-3 FAs for treating depressive disorders have had equivocal findings. Variability in results might be partially explained by differences in the severity of baseline depression among diverse study populations, diagnostic variation, differing omega-3 supplementation protocols, or other issues.13 In addition, publication bias also may affect results.

In a 2011 literature review and meta-analysis of omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or an adjunct to antidepressants to treat MDD, Bloch and Hannestad6 concluded that omega-3 FAs offer a small but nonsignificant benefit in treating MDD. This review suggested that omega-3 FAs may be more effective in patients with more severe depression. The effects of varying levels of EPA vs DHA were not examined.

In a systematic review and meta-analysis, Appleton et al14 concluded that omega-3 FA supplements have little beneficial effect on depressed mood in individuals who do not have a depressive illness diagnosis (eg, MDD). However, this study did not consider the differential effects of EPA vs DHA on treatment response. Patients diagnosed with a depressive illness received greater benefits from omega-3 FA supplementation, although the patients in this study were heterogeneous. Similar to Bloch and Hannestad, Appleton et al14 found that omega-3 FA supplementation may be most beneficial for depressed patients with more severe symptoms, but is unlikely to help those with mild-to-moderate symptoms or individuals without symptoms who aim to prevent depression.

A meta-analysis by Martins15 looked at EPA vs DHA to treat depressive illness and found that only supplements that were mostly or completely EPA effectively treated depressive symptoms. Martins also found that severity of illness is key for positive treatment outcomes; there was a significant relationship between higher baseline depression levels and efficacy.15 Martins noted that omega-3 FA therapy was more effective as a treatment than a preventive strategy, and that adding omega-3 FAs to antidepressants was more efficacious than omega-3 FAs alone.15

A meta-analysis of clinical trials of omega-3 FAs for depressive illness suggested EPA should be ≥60% of total EPA + DHA.16

BD. A recent meta-analysis of 6 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) found that adding omega-3 supplements to mood stabilizers in patients with BD was associated with a statistically significant reduction of depressive symptoms, but was not effective for treating mania.17 The authors suggested patients with BD—especially those with comorbid cardiovascular or metabolic conditions— increase their dietary consumption of foods containing omega-3 FAs (Table)18 and, if necessary, take a supplement of 1 to 1.5 g/d of mixed EPA and DHA, with a higher ratio of EPA.19 See Box 3 for a box on how to read omega-3 supplement labels.

In a small RCT of 51 children and adolescents (age 6 to 17) with symptomatic bipolar I or bipolar II disorder, supplementation with flax oil (alpha-linolenic acid, a polyunsaturated omega-3 FA that is a precursor to EPA and DHA) did not affect symptoms as measured by several rating scales.20

Perinatal and postpartum depression. Omega-3 FAs are considered a safe treatment for depressive disorders during pregnancy because they provide neurodevelopmental benefits for neonates and have few contraindications during pregnancy.21 RCTs of omega-3 FA monotherapy for perinatal depression have been small (≤51 patients) and produced mixed findings.21 A pilot study (N = 16) of patients with postpartum depression found a significant decrease in depressive symptoms with EPA treatment.22 More research is needed before omega-3 FA supplementation can be recommended during pregnancy.

Table

Foods with healthy fats: From best to worst

| Polyunsaturated fats | Omega-3 | Fish-based: oily fish, including salmon, tuna, mackerel, lake trout, herring, and sardines Plant-based: tofu and other forms of soybeans; walnuts and flaxseed and their oils, and canola oil |

| Omega-6 | Only available in plant-based form: corn, soy, and safflower oil | |

| Monosaturated fats | Olive and peanut oil | |

| Saturated fats | Red meats, high-fat dairy, and partially hydrogenated oils | |

| Source: Reference 18 | ||

Because nutritional supplements vary, advise patients to look at the supplement facts on the back of a bottle of omega-3 fatty acids. The American Psychiatric Association recommends patients take a total eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) + docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) of 1 g/d; EPA should be ≥60% of total EPA + DHA.

This image is an example of a label that would meet the appropriate criteria. Total EPA + DHA = 1,490 mg and EPA is 60% of this combined total.

Source: Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1577-1584

Schizophrenia

In a Cochrane review of 8 studies of patients with schizophrenia, adjunctive treatment with omega-3 FAs led to >25% reduction in the Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale, but this improvement was not statistically significant.23 Omega-3 FAs did not decrease tardive dyskinesia symptoms as measured by the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale. The authors stated that results were inconclusive, and use of omega-3 FAs in patients with schizophrenia remains experimental. In a separate meta-analysis that included 335 patients with schizophrenia, EPA augmentation had no beneficial effect on psychotic symptoms.24

In a double-blind RCT of 81 adolescents and young adults (age 13 to 25) at ultra-high risk of psychotic illness, 5% of patients who received 1.2 g/d of omega-3 FAs developed a psychotic disorder compared with 28% of patients receiving placebo.25 The authors concluded that supplementation with omega-3 FAs may be a safe and effective strategy for young patients with subthreshold psychotic symptoms.

Dementia

Studies evaluating the relationship between omega-3 FAs and dementia risk have revealed mixed findings.26,27 In a pilot study of 10 geriatric patients with moderately severe dementia related to thrombotic cerebrovascular disorder, DHA supplementation led to improved Hamilton Depression Rating Scale and Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) scores compared with controls.28 In another study, administering EPA to 64 patients with Alzheimer’s disease significantly improved MMSE scores, with maximum improvement at 3 months, but this benefit dissipated after 6 months of treatment.29 In a study of 22 patients with various types of dementia, Suzuki et al30 found that DHA supplementation improved scores on a Japanese dementia scale. These studies show promise, but more evidence is necessary before recommendations can be made.

Other psychiatric disorders

Omega-3 FAs as monotherapy or an adjunct to psychostimulants does not seem to improve symptoms in children who meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).31-33 Studies of omega-3 FAs as treatment for anxiety and personality disorders are limited. To date, omega-3 FAs as adjunctive treatment in obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and monotherapy in borderline personality disorder have not shown efficacy.34,35

Using omega-3 FAs in practice

Based on new data and several recent meta-analyses, clinical recommendations have emerged. Sarris et al17 suggested patients with BD increase dietary intake of omega-3 FAs or take a supplement with 1 to 1.5 g/d of mixed EPA and DHA (with a higher ratio of EPA). In MDD, the type of omega-3 FA supplementation seems to be important; EPA seems to be the primary component for efficacy.15,19 Additionally, the more severe the depression, the more likely symptoms will respond to omega-3 FAs.6,14,15 Omega-3 FAs are not effective at preventing depression14,15 and evidence is equivocal for treating perinatal depression.21 Omega-3 FA supplementation has not shown efficacy for patients with schizophrenia,23,24 although it may prevent transition to psychosis in adolescents and young adults at ultra-high risk for a psychotic disorder.25 Data examining omega-3 FA supplementation in postpartum depression22 and dementia28,29 are limited but show promise. Omega-3 FAs appear to lack efficacy in ADHD,31-33 OCD,34 and borderline personality disorder.35

Related Resources

- National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine. Omega-3 fatty acids. http://nccam.nih.gov/health/omega3.

- National Institutes of Health. Office of Dietary Supplements. Working group report: Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease. http://ods.od.nih.gov/Health_Information/omega_3_fatty_acids.aspx.

Disclosure

Dr. Morreale reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Hibbeln JR. Fish consumption and major depression. Lancet. 1998;351(9110):1213.-

2. Tanskanen A, Hibbeln JR, Tuomilehto J, et al. Fish consumption and depressive symptoms in the general population in Finland. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(4):529-531.

3. Silvers KM, Scott KM. Fish consumption and self-reported physical and mental health status. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(3):427-431.

4. Timonen M, Horrobin DF, Jokelaienen J, et al. Fish consumption and depression: the northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(3):447-452.

5. Freeman MP, Rapaport MH. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: from cellular mechanisms to clinical care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(2):258-259.

6. Bloch MH, Hannestad J. Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of depression: systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print September 20 2011]. Mol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.100.

7. Parker G, Gibson NA, Brotchie H, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):969-978.

8. Martinez JM, Marangell LB. Omega-3 fatty acids: do ‘fish oils’ have a therapeutic role in psychiatry? Current Psychiatry. 2004;3(1):25-52.

9. Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects of coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000252.-

10. Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. AHA Nutrition Committee. American Heart Association. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: new recommendations from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(2):151-152.

11. Freeman MP, Fava M, Lake J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in major depressive disorder: the American Psychiatric Association Task Force report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):669-681.

12. Freeman MP, Hibbeln J, Wisner KL, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence basis for treatment and future research in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(12):1954-1967.

13. Mischoulon D. The impact of omega-3 fatty acids on depressive disorders and suicidality: can we reconcile 2 studies with seemingly contradictory results? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1574-1576.

14. Appleton KM, Rogers PJ, Andrew RN. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on depressed mood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(31):757-770.

15. Martins JG. EPA but not DHA appears to be responsible for the efficacy of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28(5):525-542.

16. Young G, Conquer J. Omega-3 fatty acids and neuropsychiatric disorders. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2005;45(1):1-28.

17. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

18. Sacks F. Ask the expert: omega-3 fatty acids. The Nutrition Source.http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/questions/omega-3/index.html. Accessed July 23 2012.

19. Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1577-1584.

20. Gracious BL, Chirieac MC, Costescu S, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of flax oil in pediatric bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(2):142-154.

21. Freeman MP. Omega-3 fatty acids in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 5):7-11.

22. Freeman MP, Hibbeln JR, Wisner KL, et al. Randomized dose-ranging pilot trial of omega-3 fatty acids for postpartum depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):31-35.

23. Joy CB, Mumby-Croft R, Joy LA. Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD001257.-

24. Fusar-Poli P, Berger G. Eicosapentaenoic acid interventions in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(2):179-185.

25. Amminger GP, Schäfer MR, Papageorgiou K, et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):146-154.

26. Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, et al. Consumption of fish and n-3 fatty acids and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(7):940-946.

27. Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, et al. Diet and risk of dementia: does fat matter? The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1915-1921.

28. Terano T, Fujishiro S, Ban T, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation improves the moderately severe dementia from thrombotic cerebrovascular diseases. Lipids. 1999;34 suppl:S345-S346.

29. Otsuka M. Analysis of dietary factors in Alzheimer’s disease: clinical use of nutritional intervention for prevention and treatment of dementia [in Japanese]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2000;37(12):970-973.

30. Suzuki H, Morikawa Y, Takahashi H. Effect of DHA oil supplementation in intelligence and visual acuity in the elderly. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2001;88:68-71.

31. Joshi K, Lad S, Kale M, et al. Supplementation with flax oil and vitamin C improves the outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;74(1):17-21.

32. Voigt RG, Llorente AM, Jensen CL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr. 2001;139(2):189-196.

33. Hirayama S, Hamazaki T, Terasawa K. Effect of docosahexaenoic acid-containing food administration on symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(3):467-473.

34. Fux M, Benjamin J, Nemets B. A placebo-controlled cross-over trial of adjunctive EPA in OCD. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38(3):323-325.

35. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Omega-3 Fatty acid treatment of women with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):167-169.

1. Hibbeln JR. Fish consumption and major depression. Lancet. 1998;351(9110):1213.-

2. Tanskanen A, Hibbeln JR, Tuomilehto J, et al. Fish consumption and depressive symptoms in the general population in Finland. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52(4):529-531.

3. Silvers KM, Scott KM. Fish consumption and self-reported physical and mental health status. Public Health Nutr. 2002;5(3):427-431.

4. Timonen M, Horrobin DF, Jokelaienen J, et al. Fish consumption and depression: the northern Finland 1966 birth cohort study. J Affect Disord. 2004;82(3):447-452.

5. Freeman MP, Rapaport MH. Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: from cellular mechanisms to clinical care. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(2):258-259.

6. Bloch MH, Hannestad J. Omega-3 fatty acids for the treatment of depression: systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print September 20 2011]. Mol Psychiatry. doi: 10.1038/mp.2011.100.

7. Parker G, Gibson NA, Brotchie H, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids and mood disorders. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(6):969-978.

8. Martinez JM, Marangell LB. Omega-3 fatty acids: do ‘fish oils’ have a therapeutic role in psychiatry? Current Psychiatry. 2004;3(1):25-52.

9. Mozaffarian D, Micha R, Wallace S. Effects of coronary heart disease of increasing polyunsaturated fat in place of saturated fat: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS Med. 2010;7(3):e1000252.-

10. Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ. AHA Nutrition Committee. American Heart Association. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular disease: new recommendations from the American Heart Association. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23(2):151-152.

11. Freeman MP, Fava M, Lake J, et al. Complementary and alternative medicine in major depressive disorder: the American Psychiatric Association Task Force report. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(6):669-681.

12. Freeman MP, Hibbeln J, Wisner KL, et al. Omega-3 fatty acids: evidence basis for treatment and future research in psychiatry. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(12):1954-1967.

13. Mischoulon D. The impact of omega-3 fatty acids on depressive disorders and suicidality: can we reconcile 2 studies with seemingly contradictory results? J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1574-1576.

14. Appleton KM, Rogers PJ, Andrew RN. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of n-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids on depressed mood. Am J Clin Nutr. 2010;91(31):757-770.

15. Martins JG. EPA but not DHA appears to be responsible for the efficacy of omega-3 long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation in depression: evidence from a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Am Coll Nutr. 2009;28(5):525-542.

16. Young G, Conquer J. Omega-3 fatty acids and neuropsychiatric disorders. Reprod Nutr Dev. 2005;45(1):1-28.

17. Sarris J, Mischoulon D, Schweitzer I. Omega-3 for bipolar disorder: meta-analyses of use in mania and bipolar depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2012;73(1):81-86.

18. Sacks F. Ask the expert: omega-3 fatty acids. The Nutrition Source.http://www.hsph.harvard.edu/nutritionsource/questions/omega-3/index.html. Accessed July 23 2012.

19. Sublette ME, Ellis SP, Geant AL, et al. Meta-analysis of the effects of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) in clinical trials in depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(12):1577-1584.

20. Gracious BL, Chirieac MC, Costescu S, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of flax oil in pediatric bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2010;12(2):142-154.

21. Freeman MP. Omega-3 fatty acids in major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 5):7-11.

22. Freeman MP, Hibbeln JR, Wisner KL, et al. Randomized dose-ranging pilot trial of omega-3 fatty acids for postpartum depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2006;113(1):31-35.

23. Joy CB, Mumby-Croft R, Joy LA. Polyunsaturated fatty acid supplementation for schizophrenia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD001257.-

24. Fusar-Poli P, Berger G. Eicosapentaenoic acid interventions in schizophrenia: meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled studies. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;32(2):179-185.

25. Amminger GP, Schäfer MR, Papageorgiou K, et al. Long-chain omega-3 fatty acids for indicated prevention of psychotic disorders: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010;67(2):146-154.

26. Morris MC, Evans DA, Bienias JL, et al. Consumption of fish and n-3 fatty acids and risk of incident Alzheimer disease. Arch Neurol. 2003;60(7):940-946.

27. Engelhart MJ, Geerlings MI, Ruitenberg A, et al. Diet and risk of dementia: does fat matter? The Rotterdam Study. Neurology. 2002;59(12):1915-1921.

28. Terano T, Fujishiro S, Ban T, et al. Docosahexaenoic acid supplementation improves the moderately severe dementia from thrombotic cerebrovascular diseases. Lipids. 1999;34 suppl:S345-S346.

29. Otsuka M. Analysis of dietary factors in Alzheimer’s disease: clinical use of nutritional intervention for prevention and treatment of dementia [in Japanese]. Nihon Ronen Igakkai Zasshi. 2000;37(12):970-973.

30. Suzuki H, Morikawa Y, Takahashi H. Effect of DHA oil supplementation in intelligence and visual acuity in the elderly. World Rev Nutr Diet. 2001;88:68-71.

31. Joshi K, Lad S, Kale M, et al. Supplementation with flax oil and vitamin C improves the outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty Acids. 2006;74(1):17-21.

32. Voigt RG, Llorente AM, Jensen CL, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of docosahexaenoic acid supplementation in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Pediatr. 2001;139(2):189-196.

33. Hirayama S, Hamazaki T, Terasawa K. Effect of docosahexaenoic acid-containing food administration on symptoms of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder - a placebo-controlled double-blind study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2004;58(3):467-473.

34. Fux M, Benjamin J, Nemets B. A placebo-controlled cross-over trial of adjunctive EPA in OCD. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38(3):323-325.

35. Zanarini MC, Frankenburg FR. Omega-3 Fatty acid treatment of women with borderline personality disorder: a double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):167-169.

How to target psychiatric symptoms of Huntington’s disease

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

Psychiatric symptoms are a common and debilitating manifestation of Huntington’s disease (HD), a progressive, inherited neurodegenerative disorder also characterized by chorea (involuntary, nonrepetitive movements) and cognitive decline. The prevalence of HD is 4 to 8 patients per 100,000 persons in most populations of European descent, with lower prevalence among non-Europeans.1 HD is caused by an abnormal expansion of a trinucleotide (CAG) repeat sequence on chromosome 4, and is inherited in an autosomal dominant fashion, meaning a HD patient’s child has a 50% chance of inheriting the mutation. The expansion is located in the gene that encodes the “huntingtin” protein, the normal function of which is not well understood.

There’s no cure for HD, and treatments primarily are directed at symptom control. Psychiatric symptoms include depression, apathy, anxiety, and psychosis (Table).2-4 Treating patients with HD can be challenging because most psychiatrists will see only a handful of patients with this multifaceted illness during their careers. See Box 1 for a case study of a patient with HD.

Table

Psychiatric symptoms of HD

| Anxiety |

| Apathy |

| Delusions |

| Disinhibitions, impulsivity, aggressive behavior |

| Dysphoria |

| Euphoria |

| Hallucinations |

| Irritability |

| Obsessions and compulsions |

| HD: Huntington’s disease Source: References 2-4 |

Mr. M, age 50, was diagnosed with Huntington’s disease (HD) 1 year ago. He returns to our psychiatric clinic for treatment of depressive symptoms and temper. Previously, he was prescribed citalopram, 40 mg/d; eventually low-dose olanzapine, 2.5 mg at night, was added. Mr. M reported better temper control, but his low mood, irritability, hopelessness, and amotivation were not significantly improved.

Mr. M left his job at a software company because he had difficulty completing tasks as the result of mood and cognitive changes. He wants to return to work, but feels that he would be unable to complete his job duties.

He begins a trial of bupropion, 150 mg/d, to improve the vegetative component of his mood symptoms to help him return to work. Mr. M now complains of worsening chorea, irritability, and insomnia, with continued difficulty completing tasks. He is intermittently tearful throughout the interview.

Mr. M continues to struggle with mood symptoms that likely are related to the stressful experience of declining function and the intrinsic evolution of HD. His chorea worsens on bupropion; this agent is discontinued and replaced with mirtazapine, 15 mg at night, for his depressive symptoms and insomnia. Citalopram and olanzapine are unchanged. Mr. M is advised to follow up with our HD psychiatry team in 1 month, and is referred for brief psychotherapy. We remind him—as we do for all of our HD patients—to call the HD clinic or 911 if he becomes suicidal. Ongoing treatment efforts likely will be complex, given the multifaceted and progressive nature of his disease.

Psychiatric sequelae

In general, psychiatric symptoms of HD become increasingly prevalent over time (Box 2).3,5 In a 2001 study of 52 HD patients by Paulsen et al,2 51 patients had ≥1 psychiatric symptom, such as dysphoria (69.2%), agitation (67.3%), irritability (65.4%), apathy (55.8%), and anxiety (51.9%); delusions (11.5%) and hallucinations (1.9%) were less prevalent.2 Similarly, Thompson et al3 followed 111 HD patients for ≥3 years and all experienced psychiatric symptoms.

According to Thompson et al,3 the presence and severity of apathy, irritability, and depression trend differently across the course of Huntington’s disease (HD). Apathy worsens with disease progression, closely following cognitive and motor symptoms. Irritability increases significantly, but this effect seems confined to early stages of HD. Depressive symptoms appear to decline slightly as HD advances, although it is unclear if this is because of antidepressants’ effects, increasing emotional blunting, and waning insight in later stages of HD, or another unknown factor.3 This study did not examine psychotic symptoms over time because few patients were experiencing delusions or hallucinations.

Similar to Thompson et al, Naarding et al5 found that apathy and depression in HD follow distinct time courses. Depression is a feature of early HD and apathy worsens with overall disease progression.

Depressed mood and functional ability—not cognitive or motor symptoms6—are the 2 most critical factors linked to health-related quality of life in HD. Hamilton et al7 found that apathy or executive dysfunction in HD patients is strongly related to decline in ability to complete activities of daily living, and may be severely debilitating.

Apathy. Often mistaken for a symptom of depression, apathy’s presentation may resemble anhedonia or fatigue; however, research suggests that depression and apathy are distinct conditions. Naarding et al

5 noted that apathy is more common than depressive symptoms in HD patients and may be a hallmark symptom of HD.

Depression affects most HD patients, and often is most severe early in the disease course. Hubers et al8 found that 20% of 100 HD patients had suicidal ideation. The strongest predictor was depressed mood.

Sleep disturbances and daytime somnolence are common among HD patients, and patients with comorbid depression report more disturbed sleep. Managing disturbed sleep and daytime somnolence in HD, with emphasis on comorbid depression, may improve the quality of life of patients and their caregivers.9

Anxiety was present in >50% of HD patients in a study by Paulsen et al2 and 37% evaluated by Craufurd et al.10 Craufurd et al10 also reported that 61% of patients were “physically tense and unable to relax.”

Among HD patients, 5% report obsessions and 10% report compulsive behaviors; these symptoms appear to become increasingly common as HD progresses.4,10

Impulsivity and disinhibition. Craufurd et al10 found that 71% of HD patients experienced poor judgment and self-monitoring, 40% had poor temper control and verbal outbursts, 22% exhibited threatening behavior or violence, and 6% had disinhibited or inappropriate sexual behavior.10

Recent studies have shown higher rates of disinhibition in “presymptomatic” gene-positive subjects vs gene-negative controls, suggesting that these symptoms may arise early in HD.11 Further, researchers demonstrated that patients lack symptom awareness and rate themselves as less impaired than their caregivers do.11