User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

People who live in ethical ‘glass houses’

Psychiatrists often have to deal with “ethically challenged” entities or individuals. This can be of concern because, ultimately, unethical policies or behavior can harm our patients. However, psychiatrists recognize that what may appear to be unethical to them may not be considered as such by nonpsychiatrists.

Ethics (from Ethos, which means customs) is defined as the standards and rules of conduct that govern a set of human actions by a specific group, profession, or culture. Thus, there are medical ethics, corporate ethics, Christian ethics, student ethics, fishing ethics, etc. Ethics is, therefore, not an absolute standard and may exist only “in the eye of the beholder.” For example, psychiatry as a medical specialty has its own rigorous ethical code that other medical specialties do not uphold (such as prohibiting socializing with patients).

Who are the entities whose ethical transgressions may affect psychiatrists’ work? Consider the following examples:

Insurance companies. Some of their business practices outrage psychiatrists, including:

- vehemently opposing parity for psychiatric brain disorders with other medical disorders

- refusing to cover preexisting conditions

- the preauthorization farce, which costs psychiatrists a large amount of uncompensated time and effort (essentially an unfunded mandate)

- low reimbursement rate for psychiatric care and a bias against coverage for psychotherapy

- forcing stable patients to switch to a cheaper medication that may not work as well, thus potentially destabilizing the patient.

Pharmaceutical companies. Because of intense scrutiny by regulatory and compliance bodies, pharmaceutical companies have largely discontinued questionable practices such as:

- not publishing unfavorable drug data

- minimizing serious side effects such as obesity and diabetes until after their drug is widely used.

However, some companies continue to disconcert psychiatrists and trigger their umbrage by:

- abandoning psychiatric drug development despite the tremendous unmet need and shifting resources to more profitable therapeutic areas

- direct-to-consumer advertising that disrupts the doctor-patient relationship and undermines psychiatrists’ clinical judgment.

The FDA. This key government agency plays an important role in protecting the public, but its policies occasionally spawn ethical dilemmas.

For example, why does it insist that new psychiatric medications be indicated for a DSM “diagnosis” instead of common “symptoms” such as agitation, depression, delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, or impulsivity? DSM diagnoses are arbitrary, committee-created constructs that may change drastically from edition to edition. There is extensive evidence for overlapping symptoms of many psychiatric “diagnoses,” which implies that a drug approved and deemed safe and effective for 1 psychiatric syndrome (eg, psychosis, depression) can help other disorders that share symptoms.

Why doesn’t the FDA channel the billions of dollars in penalties they have imposed on pharmaceutical companies to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) instead of to the government’s general fund? These valuable funds are being siphoned from research; ethically, from a public health perspective, they should be kept in research. These billions can help one of the NIH institutes such the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) establish a psychiatric drug development section to translate biologic discoveries into novel treatments. No such capability exists at the NIMH due to lack of funds.

Legislators. There generally is considerable cynicism about the ethical conduct of politicians, but from psychiatry’s point of view, consider the following:

- Why not use the force of law to enforce parity in insurance coverage?

- Why are legislators willing to appropriate funds to build prisons but not long-term psychiatric hospitals? Is it ethical to criminalize mental illness and incarcerate persons with brain disorders side-by-side with hardened criminals instead of providing them with a dignified and safe medical facility?

- Why don’t legislators fix the broken public mental health system that is underfunded, ineffective, and too bureaucratic for patients and families to navigate?

The media. Although significant improvement has taken place in portraying mental illness compared with a few decades ago, the following unacceptable patterns continue:

- depicting the mentally ill as dangerous killers and “psychos”

- continuing to mock mental illness and addictions as character frailties rather than view them as legitimate illnesses

- failing to expose the injustices that afflict persons with psychiatric brain disorders, including stigma, neglect of physical health needs, inadequate treatment resources (such as availability of inpatient psychiatric beds), or imprisonment in lieu of hospitalization.

Communities. It is regrettable that the negative attitude toward mental illness still is intense enough to perpetuate the vociferous “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) opposition to mental health clinics, residential facilities, or halfway houses. Although the NIMBY syndrome is driven by lack of education and/or understanding of mental illness, ignorance is a poor excuse for ethical shortcomings.

Non-psychiatric physicians. It is quite disheartening to see how prejudiced some internists and surgeons can be toward mentally ill individuals. Most developed a distorted view of psychiatry from being trained decades ago, before the momentous neuroscience advances in psychiatry. But more worrisome are the barriers mentally ill persons face in health care1-4 that lead to underutilization of routine primary care5 and underdiagnosis of serious health conditions.2,6 Psychiatric patients are less likely to undergo coronary revascularization procedures after a myocardial infarction7 or to be properly treated for chronic conditions such as arthritis.8 Limited or inadequate medical care has led to early mortality.9,10 But there is good news from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, where psychiatric patients with diabetes receive as good care as veterans without mental illness11 and have no barriers to nutrition and exercise counseling.12

What about our own ethical conduct?

Finally, perhaps psychiatrists should think twice before throwing stones because we, too, may live in ethical “glass houses.” Although we try to adhere to our ethical standards, some of us occasionally may commit ethical peccadilloes, such as:

- continuing to use haloperidol, a 45-year-old drug that has been shown to be neurotoxic in >20 studies over the past decade13

- ignoring tier I evidence-based treatments and using unproven modalities that may delay illness resolution

- not regularly monitoring patients for metabolic complications of antipsychotics14

- not using depot antipsychotics for patients who exhibit violent behavior each time they relapse due to nonadherence

- requiring a drug company representative to bring lunch to the entire clinic staff in return for access to the prescriber.

The quandary with ethics is that they can be too nuanced, enabling almost anyone who breaches an ethical boundary to find a justification. The most unambiguous ethical standards have long been moved from a moral philosophy to codified and legally enforced laws (robbery, assault, rape, homicide, etc.). Psychiatry deals with many groups that have their own version of an “ethics compass.” We psychiatrists have our own ethics standards, which we always aspire to uphold. However, are we so ethically infallible that we can smugly throw stones at people who live in ethical “glass houses?” Doesn’t our ethical “brick house” have glass windows?

Reference

1. Druss BG. The mental health/primary care interface in the United States: history structure, and context. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(4):197-202.

2. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Use of medical services by veterans with mental disorders. Psychosomatics. 1997;38(5):451-458.

3. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(12):1775-1777.

4. Levinson Miller C, Druss BG, Dombrowski EA, et al. Barriers to primary medical care among patients at a community mental health center. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(8):1158-1160.

5. Bosworth HB, Calhoun PS, Stechuchak KM, et al. Use of psychiatric and medical health care by veterans with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(6):708-710.

6. Cradock-O’Leary J, Young AS, Yano EM, et al. Use of general medical services by VA patients with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):874-878.

7. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283(4):506-511.

8. Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(21):1516-1520.

9. Casey DE, Hansen TE. Excessive mortality and morbidity associated with schizophrenia. In: Meyer JM Nasrallah HA, eds. Medical illness and schizophrenia. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008;17-35.

10. Enger C, Weatherby L, Reynolds RF, et al. Serious cardiovascular events and mortality among patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(1):19-27.

11. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al. Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1584-1590.

12. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al. Receipt of nutrition and exercise counseling among medical outpatients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(7):556-560.

13. Nasrallah HA. Invisible tattoos: the stigmata of psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(9):18-19.

14. Buckley PF, Miller DD, Singer B, et al. Clinicians’ recognition of the metabolic adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(2-3):281-288.

Psychiatrists often have to deal with “ethically challenged” entities or individuals. This can be of concern because, ultimately, unethical policies or behavior can harm our patients. However, psychiatrists recognize that what may appear to be unethical to them may not be considered as such by nonpsychiatrists.

Ethics (from Ethos, which means customs) is defined as the standards and rules of conduct that govern a set of human actions by a specific group, profession, or culture. Thus, there are medical ethics, corporate ethics, Christian ethics, student ethics, fishing ethics, etc. Ethics is, therefore, not an absolute standard and may exist only “in the eye of the beholder.” For example, psychiatry as a medical specialty has its own rigorous ethical code that other medical specialties do not uphold (such as prohibiting socializing with patients).

Who are the entities whose ethical transgressions may affect psychiatrists’ work? Consider the following examples:

Insurance companies. Some of their business practices outrage psychiatrists, including:

- vehemently opposing parity for psychiatric brain disorders with other medical disorders

- refusing to cover preexisting conditions

- the preauthorization farce, which costs psychiatrists a large amount of uncompensated time and effort (essentially an unfunded mandate)

- low reimbursement rate for psychiatric care and a bias against coverage for psychotherapy

- forcing stable patients to switch to a cheaper medication that may not work as well, thus potentially destabilizing the patient.

Pharmaceutical companies. Because of intense scrutiny by regulatory and compliance bodies, pharmaceutical companies have largely discontinued questionable practices such as:

- not publishing unfavorable drug data

- minimizing serious side effects such as obesity and diabetes until after their drug is widely used.

However, some companies continue to disconcert psychiatrists and trigger their umbrage by:

- abandoning psychiatric drug development despite the tremendous unmet need and shifting resources to more profitable therapeutic areas

- direct-to-consumer advertising that disrupts the doctor-patient relationship and undermines psychiatrists’ clinical judgment.

The FDA. This key government agency plays an important role in protecting the public, but its policies occasionally spawn ethical dilemmas.

For example, why does it insist that new psychiatric medications be indicated for a DSM “diagnosis” instead of common “symptoms” such as agitation, depression, delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, or impulsivity? DSM diagnoses are arbitrary, committee-created constructs that may change drastically from edition to edition. There is extensive evidence for overlapping symptoms of many psychiatric “diagnoses,” which implies that a drug approved and deemed safe and effective for 1 psychiatric syndrome (eg, psychosis, depression) can help other disorders that share symptoms.

Why doesn’t the FDA channel the billions of dollars in penalties they have imposed on pharmaceutical companies to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) instead of to the government’s general fund? These valuable funds are being siphoned from research; ethically, from a public health perspective, they should be kept in research. These billions can help one of the NIH institutes such the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) establish a psychiatric drug development section to translate biologic discoveries into novel treatments. No such capability exists at the NIMH due to lack of funds.

Legislators. There generally is considerable cynicism about the ethical conduct of politicians, but from psychiatry’s point of view, consider the following:

- Why not use the force of law to enforce parity in insurance coverage?

- Why are legislators willing to appropriate funds to build prisons but not long-term psychiatric hospitals? Is it ethical to criminalize mental illness and incarcerate persons with brain disorders side-by-side with hardened criminals instead of providing them with a dignified and safe medical facility?

- Why don’t legislators fix the broken public mental health system that is underfunded, ineffective, and too bureaucratic for patients and families to navigate?

The media. Although significant improvement has taken place in portraying mental illness compared with a few decades ago, the following unacceptable patterns continue:

- depicting the mentally ill as dangerous killers and “psychos”

- continuing to mock mental illness and addictions as character frailties rather than view them as legitimate illnesses

- failing to expose the injustices that afflict persons with psychiatric brain disorders, including stigma, neglect of physical health needs, inadequate treatment resources (such as availability of inpatient psychiatric beds), or imprisonment in lieu of hospitalization.

Communities. It is regrettable that the negative attitude toward mental illness still is intense enough to perpetuate the vociferous “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) opposition to mental health clinics, residential facilities, or halfway houses. Although the NIMBY syndrome is driven by lack of education and/or understanding of mental illness, ignorance is a poor excuse for ethical shortcomings.

Non-psychiatric physicians. It is quite disheartening to see how prejudiced some internists and surgeons can be toward mentally ill individuals. Most developed a distorted view of psychiatry from being trained decades ago, before the momentous neuroscience advances in psychiatry. But more worrisome are the barriers mentally ill persons face in health care1-4 that lead to underutilization of routine primary care5 and underdiagnosis of serious health conditions.2,6 Psychiatric patients are less likely to undergo coronary revascularization procedures after a myocardial infarction7 or to be properly treated for chronic conditions such as arthritis.8 Limited or inadequate medical care has led to early mortality.9,10 But there is good news from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, where psychiatric patients with diabetes receive as good care as veterans without mental illness11 and have no barriers to nutrition and exercise counseling.12

What about our own ethical conduct?

Finally, perhaps psychiatrists should think twice before throwing stones because we, too, may live in ethical “glass houses.” Although we try to adhere to our ethical standards, some of us occasionally may commit ethical peccadilloes, such as:

- continuing to use haloperidol, a 45-year-old drug that has been shown to be neurotoxic in >20 studies over the past decade13

- ignoring tier I evidence-based treatments and using unproven modalities that may delay illness resolution

- not regularly monitoring patients for metabolic complications of antipsychotics14

- not using depot antipsychotics for patients who exhibit violent behavior each time they relapse due to nonadherence

- requiring a drug company representative to bring lunch to the entire clinic staff in return for access to the prescriber.

The quandary with ethics is that they can be too nuanced, enabling almost anyone who breaches an ethical boundary to find a justification. The most unambiguous ethical standards have long been moved from a moral philosophy to codified and legally enforced laws (robbery, assault, rape, homicide, etc.). Psychiatry deals with many groups that have their own version of an “ethics compass.” We psychiatrists have our own ethics standards, which we always aspire to uphold. However, are we so ethically infallible that we can smugly throw stones at people who live in ethical “glass houses?” Doesn’t our ethical “brick house” have glass windows?

Psychiatrists often have to deal with “ethically challenged” entities or individuals. This can be of concern because, ultimately, unethical policies or behavior can harm our patients. However, psychiatrists recognize that what may appear to be unethical to them may not be considered as such by nonpsychiatrists.

Ethics (from Ethos, which means customs) is defined as the standards and rules of conduct that govern a set of human actions by a specific group, profession, or culture. Thus, there are medical ethics, corporate ethics, Christian ethics, student ethics, fishing ethics, etc. Ethics is, therefore, not an absolute standard and may exist only “in the eye of the beholder.” For example, psychiatry as a medical specialty has its own rigorous ethical code that other medical specialties do not uphold (such as prohibiting socializing with patients).

Who are the entities whose ethical transgressions may affect psychiatrists’ work? Consider the following examples:

Insurance companies. Some of their business practices outrage psychiatrists, including:

- vehemently opposing parity for psychiatric brain disorders with other medical disorders

- refusing to cover preexisting conditions

- the preauthorization farce, which costs psychiatrists a large amount of uncompensated time and effort (essentially an unfunded mandate)

- low reimbursement rate for psychiatric care and a bias against coverage for psychotherapy

- forcing stable patients to switch to a cheaper medication that may not work as well, thus potentially destabilizing the patient.

Pharmaceutical companies. Because of intense scrutiny by regulatory and compliance bodies, pharmaceutical companies have largely discontinued questionable practices such as:

- not publishing unfavorable drug data

- minimizing serious side effects such as obesity and diabetes until after their drug is widely used.

However, some companies continue to disconcert psychiatrists and trigger their umbrage by:

- abandoning psychiatric drug development despite the tremendous unmet need and shifting resources to more profitable therapeutic areas

- direct-to-consumer advertising that disrupts the doctor-patient relationship and undermines psychiatrists’ clinical judgment.

The FDA. This key government agency plays an important role in protecting the public, but its policies occasionally spawn ethical dilemmas.

For example, why does it insist that new psychiatric medications be indicated for a DSM “diagnosis” instead of common “symptoms” such as agitation, depression, delusions, hallucinations, anxiety, or impulsivity? DSM diagnoses are arbitrary, committee-created constructs that may change drastically from edition to edition. There is extensive evidence for overlapping symptoms of many psychiatric “diagnoses,” which implies that a drug approved and deemed safe and effective for 1 psychiatric syndrome (eg, psychosis, depression) can help other disorders that share symptoms.

Why doesn’t the FDA channel the billions of dollars in penalties they have imposed on pharmaceutical companies to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) instead of to the government’s general fund? These valuable funds are being siphoned from research; ethically, from a public health perspective, they should be kept in research. These billions can help one of the NIH institutes such the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) establish a psychiatric drug development section to translate biologic discoveries into novel treatments. No such capability exists at the NIMH due to lack of funds.

Legislators. There generally is considerable cynicism about the ethical conduct of politicians, but from psychiatry’s point of view, consider the following:

- Why not use the force of law to enforce parity in insurance coverage?

- Why are legislators willing to appropriate funds to build prisons but not long-term psychiatric hospitals? Is it ethical to criminalize mental illness and incarcerate persons with brain disorders side-by-side with hardened criminals instead of providing them with a dignified and safe medical facility?

- Why don’t legislators fix the broken public mental health system that is underfunded, ineffective, and too bureaucratic for patients and families to navigate?

The media. Although significant improvement has taken place in portraying mental illness compared with a few decades ago, the following unacceptable patterns continue:

- depicting the mentally ill as dangerous killers and “psychos”

- continuing to mock mental illness and addictions as character frailties rather than view them as legitimate illnesses

- failing to expose the injustices that afflict persons with psychiatric brain disorders, including stigma, neglect of physical health needs, inadequate treatment resources (such as availability of inpatient psychiatric beds), or imprisonment in lieu of hospitalization.

Communities. It is regrettable that the negative attitude toward mental illness still is intense enough to perpetuate the vociferous “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) opposition to mental health clinics, residential facilities, or halfway houses. Although the NIMBY syndrome is driven by lack of education and/or understanding of mental illness, ignorance is a poor excuse for ethical shortcomings.

Non-psychiatric physicians. It is quite disheartening to see how prejudiced some internists and surgeons can be toward mentally ill individuals. Most developed a distorted view of psychiatry from being trained decades ago, before the momentous neuroscience advances in psychiatry. But more worrisome are the barriers mentally ill persons face in health care1-4 that lead to underutilization of routine primary care5 and underdiagnosis of serious health conditions.2,6 Psychiatric patients are less likely to undergo coronary revascularization procedures after a myocardial infarction7 or to be properly treated for chronic conditions such as arthritis.8 Limited or inadequate medical care has led to early mortality.9,10 But there is good news from the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs, where psychiatric patients with diabetes receive as good care as veterans without mental illness11 and have no barriers to nutrition and exercise counseling.12

What about our own ethical conduct?

Finally, perhaps psychiatrists should think twice before throwing stones because we, too, may live in ethical “glass houses.” Although we try to adhere to our ethical standards, some of us occasionally may commit ethical peccadilloes, such as:

- continuing to use haloperidol, a 45-year-old drug that has been shown to be neurotoxic in >20 studies over the past decade13

- ignoring tier I evidence-based treatments and using unproven modalities that may delay illness resolution

- not regularly monitoring patients for metabolic complications of antipsychotics14

- not using depot antipsychotics for patients who exhibit violent behavior each time they relapse due to nonadherence

- requiring a drug company representative to bring lunch to the entire clinic staff in return for access to the prescriber.

The quandary with ethics is that they can be too nuanced, enabling almost anyone who breaches an ethical boundary to find a justification. The most unambiguous ethical standards have long been moved from a moral philosophy to codified and legally enforced laws (robbery, assault, rape, homicide, etc.). Psychiatry deals with many groups that have their own version of an “ethics compass.” We psychiatrists have our own ethics standards, which we always aspire to uphold. However, are we so ethically infallible that we can smugly throw stones at people who live in ethical “glass houses?” Doesn’t our ethical “brick house” have glass windows?

Reference

1. Druss BG. The mental health/primary care interface in the United States: history structure, and context. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(4):197-202.

2. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Use of medical services by veterans with mental disorders. Psychosomatics. 1997;38(5):451-458.

3. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(12):1775-1777.

4. Levinson Miller C, Druss BG, Dombrowski EA, et al. Barriers to primary medical care among patients at a community mental health center. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(8):1158-1160.

5. Bosworth HB, Calhoun PS, Stechuchak KM, et al. Use of psychiatric and medical health care by veterans with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(6):708-710.

6. Cradock-O’Leary J, Young AS, Yano EM, et al. Use of general medical services by VA patients with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):874-878.

7. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283(4):506-511.

8. Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(21):1516-1520.

9. Casey DE, Hansen TE. Excessive mortality and morbidity associated with schizophrenia. In: Meyer JM Nasrallah HA, eds. Medical illness and schizophrenia. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008;17-35.

10. Enger C, Weatherby L, Reynolds RF, et al. Serious cardiovascular events and mortality among patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(1):19-27.

11. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al. Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1584-1590.

12. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al. Receipt of nutrition and exercise counseling among medical outpatients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(7):556-560.

13. Nasrallah HA. Invisible tattoos: the stigmata of psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(9):18-19.

14. Buckley PF, Miller DD, Singer B, et al. Clinicians’ recognition of the metabolic adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(2-3):281-288.

Reference

1. Druss BG. The mental health/primary care interface in the United States: history structure, and context. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2002;24(4):197-202.

2. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Use of medical services by veterans with mental disorders. Psychosomatics. 1997;38(5):451-458.

3. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA. Mental disorders and access to medical care in the United States. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(12):1775-1777.

4. Levinson Miller C, Druss BG, Dombrowski EA, et al. Barriers to primary medical care among patients at a community mental health center. Psychiatr Serv. 2003;54(8):1158-1160.

5. Bosworth HB, Calhoun PS, Stechuchak KM, et al. Use of psychiatric and medical health care by veterans with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(6):708-710.

6. Cradock-O’Leary J, Young AS, Yano EM, et al. Use of general medical services by VA patients with psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Serv. 2002;53(7):874-878.

7. Druss BG, Bradford DW, Rosenheck RA, et al. Mental disorders and use of cardiovascular procedures after myocardial infarction. JAMA. 2000;283(4):506-511.

8. Redelmeier DA, Tan SH, Booth GL. The treatment of unrelated disorders in patients with chronic medical diseases. N Engl J Med. 1998;338(21):1516-1520.

9. Casey DE, Hansen TE. Excessive mortality and morbidity associated with schizophrenia. In: Meyer JM Nasrallah HA, eds. Medical illness and schizophrenia. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2008;17-35.

10. Enger C, Weatherby L, Reynolds RF, et al. Serious cardiovascular events and mortality among patients with schizophrenia. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2004;192(1):19-27.

11. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al. Mental disorders and quality of diabetes care in the veterans health administration. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159(9):1584-1590.

12. Desai MM, Rosenheck RA, Druss BG, et al. Receipt of nutrition and exercise counseling among medical outpatients with psychiatric and substance use disorders. J Gen Intern Med. 2002;17(7):556-560.

13. Nasrallah HA. Invisible tattoos: the stigmata of psychiatry. Current Psychiatry. 2011;10(9):18-19.

14. Buckley PF, Miller DD, Singer B, et al. Clinicians’ recognition of the metabolic adverse effects of antipsychotic medications. Schizophr Res. 2005;79(2-3):281-288.

Personalizing depression treatment: 2 clinical tools

Approximately one-half of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) will have partial or nonresponse to first-line antidepressant monotherapy, despite receiving an adequate dosage and sufficient duration of treatment.1 This has led to the definition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) as a depressive episode that has shown insufficient response to ≥1 trial of an antidepressant that has demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials.1 Depressed patients should be treated to full remission because absence of complete remission is associated with:

- a more recurrent and chronic illness course2,3

- increased medical and psychiatric comorbidities

- greater functional burden

- increased social and economic costs linked with impaired social functioning.4

Clinicians need to properly identify MDD and treatment resistance to guide optimal treatment choices. Additional tools are necessary to accurately identify, document, and communicate about symptoms commonly experienced by depressed patients but not fully characterized by DSM-IV-TR MDD criteria.5 Finally, in many cases, trait or situational factors might obfuscate accurate diagnosis and the natural course of illness, and tools that can be implemented practically will help identify patients with MDD.

Our group has created and implemented 2 clinician-administered tools—the SAFER Interview and the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ)—to enrich the qualitative assessment of MDD and treatment resistance.

SAFER: Assessing the diagnosis, symptom severity

The SAFER interview refines the diagnosis of depressed patients by assessing the state vs trait nature of the symptoms, their assessability, their face and ecological validity, and if they pass the rule of the 3 Ps: pervasiveness, persistence, and pathological nature of the current MDD episode (Table 1 and Table 2).6 This reliable assessment of the patient’s diagnosis and symptom severity is made in a way that reflects the illness in a real-world setting.

Clinical application of SAFER. Implementing SAFER in clinical settings promotes a personalized, dimensional approach by taking into account a varying degree of symptom severity in depressed patients, in contrast to relying on symptom lists as found in the DSM-IV-TR. Using the SAFER interview deepens the typical psychiatric diagnostic process, allows for a more precise understanding of the patient’s situation, and may help clinicians select effective treatments that target specific symptoms, thus resulting in more rapid alleviation of MDD.6

Table 1

The SAFER interview: Assessing depression in a real-world setting

State vs trait nature of the symptoms

|

Assessability

|

Face validity

|

Ecological validity

|

Rule of the 3 Ps

|

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

Table 2

The SAFER criteria: Rule of the 3 Ps

| Pervasive—Do the major symptoms affect the patient across multiple arenas of life (work, relationships, school, chores, etc.)? |

| Persistent—Do the main symptoms occur most days, most of the day during the current episode? |

| Pathological—Do the symptoms of the present episode interfere with functioning? |

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

CASE REPORT: Worsening symptoms

Ms. Y, age 53, has been depressed for 30 years. She hardly remembers a time in her life when she felt good for more than a few days. However, 2 months ago she noted her symptoms got worse. She presents with many MDD symptoms as assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, eg, ongoing depressive mood, feelings of guilt, major sleep disturbances, and work impairments.

Using SAFER to evaluate Ms. Y, a clinician would ask: Does she have symptoms that are present primarily during an episode of acute illness? Does the episode constitute a measurable exacerbation of preexisting symptoms? This clinical vignette illustrates the importance of the first SAFER criterion, state vs trait nature of the symptoms. Ms. Y is a SAFER “pass”—meaning consistent with a major depressive episode—because exacerbation of preexisting symptoms is measurable. However, if her symptoms represented a chronic, long-standing trait, she would be a SAFER “fail” based on this criterion, and her symptoms likely would not improve during a brief pharmacologic intervention. For such patients, SAFER would have oriented the clinician toward alternative therapies such as psychotherapy or a combination of longer, more complex pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy.

By helping clinicians refine MDD diagnoses, SAFER draws attention to specific depression entities (eg, MDD or dysthymia) and directs them toward appropriate guidelines, treatment algorithms, and precautions (eg, when treated with pharmacotherapy, dysthymic patients are particularly sensitive to unwanted effects and adherence is a serious issue).7 The SAFER interview also can help identify when what appears to be a depressive episode clearly is precipitated by situational factors, and is more likely to be influenced by changes in the patient’s life than by treatment. For such patients, first consider nonpharmacologic interventions to avoid unnecessary medication exposure.

ATRQ: Efficacy and adequacy

The ATRQ examines the efficacy (improvement from 0% [not improved at all] to 100% [completely improved]), and adequacy (adequate duration and dose) of any antidepressant treatment in a step-by-step procedure.1,8,9 For a copy of the ATRQ, click here.

While conducting the interview, clinicians ask about treatment adherence to each medication trial. A treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, from monotherapy to combination to augmentation.10 For each trial, the ATRQ systematically reviews 4 strategies to enhance treatment response:

- increasing the initial antidepressant dosage11

- combining the initial antidepressant with another antidepressant, typically from another class12

- augmenting the initial antidepressant with a nonantidepressant12

- switching from the initial antidepressant to another antidepressant.13

These strategies also are applied in cases of lost sustained antidepressant efficacy or depressive relapse/recurrence, although empirical evidence supporting these strategies is lacking, with the possible exception of dose increase.14,15

In the convention our group adopted, an adequate antidepressant trial must be ≥6 weeks in total length, with a dose within an adequate range as specified in the medication’s package insert. In addition, for the purposes of conducting TRD trials, we have considered a patient treatment-resistant if response to adequate dose and duration is <50%. On the ATRQ, 50% improvement refers to 50% symptom reduction from baseline without achieving remission. In an initial clinical trial that lasts ≥6 weeks, any dose increase (for ≥4 weeks) represents optimization and is not considered a new or separate trial, whereas augmentation or combination therapy (for ≥3 weeks) or a switch to another antidepressant (for ≥6 weeks) are considered new trials/treatments.

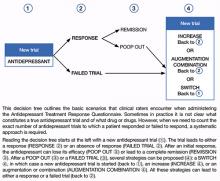

Decision tree for ATRQ. Because antidepressant treatment always is constrained by personal (eg, adherence, insurance coverage, etc.) and clinical (eg, contraindications due to comorbid conditions, side effects, etc.) considerations, we propose a decision tree to help clinicians determine the number of failed antidepressant trials their patient experienced (Figure). Although this tree does not represent all treatment scenarios, we hope it could help clinicians implement TRD treatment strategies because it highlights proper assessment of treatment duration, dosage, and changes before applying a TRD diagnosis.

The ATRQ meticulously examines patients’ antidepressant history to identify:

- pseudo-resistance, to guide adequate dosing and/or duration, and

- resistance, to propose next-step treatment.

Pseudo-resistance refers to treatment failures that can be attributed to factors such as inadequate treatment dosing or duration, atypical pharmacokinetics that reduce agents’ effectiveness, patient nonadherence (eg, due to adverse effects), or misdiagnosis of the primary disorder (ie, other mood disorders or depressive subsets such as dysthymia or minor depression mistreated as unipolar depression).16,17 Studies show that many patients with MDD referred to specialty settings are undertreated and receive inadequate antidepressant doses,18 which suggests that many referrals for TRD are in fact pseudo-resistance.19 Despite the lack of consensus on criteria for TRD,1 standardization of what constitutes treatment adequacy during antidepressant trials (eg, adherence, dose, duration) is indispensable.

Clinical application of the ATRQ. Because TRD may require specific interventions, we first need to properly identify treatment resistance. Also, systematic use of a classification system enhances the ability of clinicians and patients to provide meaningful descriptions of antidepressant resistance.

In clinical practice, choice of treatment strategy is based on factors that include partial or nonresponse, tolerability, avoiding withdrawal symptoms, the need to target side effects of a current antidepressant by administering another drug, cost, avoiding drug-drug interactions, and patient preference. Because a treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, it is essential to obtain information about all treatments to determine the number of failed clinical trials a patient may have had for the current MDD episode and lifetime episodes. The importance of asking about adherence to each trial cannot be overemphasized.

Figure: Using the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire: A decision tree

CASE REPORT: Limited improvement

Mr. T, age 45, reported that his current depressive episode started several years ago. The first antidepressant trial he received, sertraline, 100 mg/d for 3 months, resulted in 0% improvement. Next he received citalopram, 20 mg/d, for 1 month, without any improvement. The next trial, venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, for 7 weeks, resulted in a 30% response. More recently Mr. B tried duloxetine, up to 90 mg/d, for 2 years with an 80% improvement during the first 3 months and then a decrease of response to <40%. He then received aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, in combination with duloxetine for approximately 4 weeks with no response.

Using the ATRQ to evaluate Mr. B, a clinician would consider the sertraline trial as a failed trial. The citalopram treatment would not be considered an adequate trial because it was too short. The venlafaxine course wouldn’t count as an adequate trial because the dosage was too low. The trial with duloxetine would count as a response (80% improvement) followed by a “poop out” or tachyphylaxis (40% improvement). The fifth trial with the combination of duloxetine and aripiprazole would count as a failed trial. The ATRQ highlights which drugs have been used for too short a duration or at too low a dosage. In Mr. B’s case, using the ATRQ revealed that of 5 trials, only 2 showed antidepressant resistance.

The ATRQ and decision tree are meant to provide clinicians with user-friendly tools to more precisely determine the number of failed antidepressant trials a patient experienced. By assessing if an antidepressant trial had an adequate dose and duration, the ATRQ can help suggest the next treatment options. For example, if a trial was inadequate in dose and/or duration but the patient tolerated the medication, then optimizing treatment with the current drug would be a logical next step. If a patient does not respond to an adequate trial, clinicians have several options, such as switching to another antidepressant, using a combination of medications or an augmentation strategy, or increasing the dose of the original antidepressant.

Limitations of the ATRQ. Historical rating of treatment is not as accurate as a prospective trial. Another limitation of the ATRQ is that the minimum effective dose is accepted as adequate; many clinicians would suggest that such a dose is inadequate. Also, the duration specified for augmentation, dose increase, and monotherapy are based on expert consensus1 rather than systematic research. Nonetheless, this method of documenting prior trials and treatment adequacy is an important advance.

The ATRQ lacks a place to indicate discontinuation due to intolerance. Knowing if adverse events caused treatment nonadherence or discontinuation is relevant to selecting treatment.

The ATRQ considers only pharmacotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy. Comprehensive assessment of treatment resistance requires asking about depression-specific, evidence-based psychotherapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. Another precaution is that the ATRQ and SAFER should be used in conjunction with structured or semi-structured clinical interviews and other clinical tools to rule out other primary diagnoses (eg, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or surreptitious substance abuse).20

Using SAFER and ATRQ allows clinicians to make a proper MDD diagnosis with an accurate, reliable assessment of symptom severity and a precise count of antidepressant trials of adequate duration and dose. SAFER helps differentiate MDD from other depressive disorders and can be used to separate MDD from a similar presentation of a reaction to external circumstances that may remit if these circumstances change.

These 2 clinical tools focus on MDD and TRD. Compared with treatment resistance in MDD, treatment resistance in other forms of depression, such as minor depressive disorder or dysthymia, has been inadequately researched21,22 and should be addressed in large studies. However, to help patients achieve remission of depressive disorders—especially MDD—clinicians should use patient information gathered via measurement-based care in combination with algorithm recommendations.23 Persistence of clinical care of MDD is essential because several treatment steps might be necessary for some patients to achieve remission. Throughout treatment, patients’ symptoms, adverse events secondary to ongoing treatment, and medication adherence should be assessed with appropriate tools. ATRQ and SAFER offer a clinician support in assessing treatment resistance history and a patient’s likelihood to respond to pharmacologic treatment.

Related Resources

- Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ). J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

- Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

- Depression Clinical and Research Program. www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/services/dcrp_home.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Desseilles was supported by the National Funds for Scientific Research of Belgium. Additional support came from the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

Dr. Fava receives grant/research support from, is a consultant to, and/or is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Adamed, Advanced Meeting Partners, Affectis Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Amarin Pharma, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Belvoir Media Group, Best Practice Project Management, BioMarin, BioResearch, Biovail, Boehringer Ingelheim, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon, Clinical Trials Solutions, Clintara, CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, CNS Response, Compellis Pharmaceuticals, Covance, Covidien, Cypress Pharmaceutical, DiagnoSearch Life Sciences, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, ePharmaSolutions, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Euthymics Bioscience, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Ganeden Biotech, GenOmind, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal GmbH, Icon Clinical Research, Imedex, i3 Innovus/Ingenix, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Labopharm, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier, MSI Methylation Sciences, National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institute of Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, Naurex, Neuronetics, NextWave Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Orexigen Therapeutics, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Pharmavite®, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Photothera, Precision Human Biolaboratory, Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Puretech Ventures, PsychoGenics, Psylin Neurosciences, RCT Logic, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, sanofi-aventis US, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier Laboratories, Shire, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Synthelabo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tal Medical, Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, TransForm Pharmaceuticals, United BioSource, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories.

Over the past year, Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from the Bowman Family Foundation, FisherWallace, Ganeden, and Nordic Naturals. He has received honoraria for speaking from Nordic Naturals. He has received royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins for the book Natural medications for psychiatric disorders: Considering the alternatives. No payment has exceeded $10,000.

Dr. Freeman has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Laboratories, and GlaxoSmithKline, and served on a one-time advisory board to Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Janet Witte, MD, MPH, Trina E. Chang, MD, MPH, Nadia Iovieno, MD, PhD, Christina Dording, MD, Heidi Ashih, MD, PhD, Maren Nyer, PhD, and Marasha-Fiona De Jong, MD from the Clinical Trials Network and Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

1. Fava M. Diagnosis and definition of treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53(8):649-659.

2. Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Maser JD, et al. Major depressive disorder: a prospective study of residual subthreshold depressive symptoms as predictor of rapid relapse. J Affect Disord. 1998;50(2-3):97-108.

3. Van Londen L, Molenaar RP, Goekoop JG, et al. Three- to 5-year prospective follow-up of outcome in major depression. Psychol Med. 1998;28(3):731-735.

4. Paykel ES. Achieving gains beyond response. Acta Psychiatr Scand Suppl. 2002;(415):12-17.

5. Cassano P, Fava M. Depression and public health: an overview. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53(4):849-857.

6. Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

7. Versiani M, Nardi AE, Figueira I. Pharmacotherapy of dysthymia: review and new findings. Eur Psychiatry. 1998;13(4):203-209.

8. Chandler GM, Iosifescu DV, Pollack MH, et al. RESEARCH: validation of the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire (ATRQ). CNS Neurosci Ther. 2010;16(5):322-325.

9. Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the antidepressant treatment response questionnaire. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

10. Fava M. Augmentation and combination strategies for complicated depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(11):e40.-

11. Adli M, Baethge C, Heinz A, et al. Is dose escalation of antidepressants a rational strategy after a medium-dose treatment has failed? A systematic review. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2005;255(6):387-400.

12. Fava M, Rush AJ. Current status of augmentation and combination treatments for major depressive disorder: a literature review and a proposal for a novel approach to improve practice. Psychother Psychosom. 2006;75(3):139-153.

13. Wohlreich MM, Mallinckrodt CH, Watkin JG, et al. Immediate switching of antidepressant therapy: results from a clinical trial of duloxetine. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2005;17(4):259-268.

14. Schmidt ME, Fava M, Zhang S, et al. Treatment approaches to major depressive disorder relapse. Part 1: dose increase. Psychother Psychosom. 2002;71(4):190-194.

15. Fava M, Detke MJ, Balestrieri M, et al. Management of depression relapse: re-initiation of duloxetine treatment or dose increase. J Psychiatr Res. 2006;40(4):328-336.

16. Kornstein SG, Schneider RK. Clinical features of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):18-25.

17. Souery D, Papakostas GI, Trivedi MH. Treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(suppl 6):16-22.

18. Hirschfeld RM, Keller MB, Panico S, et al. The National Depressive and Manic-Depressive Association consensus statement on the undertreatment of depression. JAMA. 1997;277(4):333-340.

19. Sackeim HA. The definition and meaning of treatment-resistant depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62(suppl 16):10-17.

20. Parker G, Malhi GS, Crawford JG, et al. Identifying “paradigm failures” contributing to treatment-resistant depression. J Affect Disord. 2005;87(2-3):185-191.

21. Harris SJ, Parent M. Patient with chronic and apparently treatment-resistant dysthymia. Am J Psychiatry. 1986;143(2):260-261.

22. Amsterdam J, Hornig M, Nierenberg AA. Treatment-resistant mood disorders. Cambridge United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

23. Trivedi MH. Tools and strategies for ongoing assessment of depression: a measurement-based approach to remission. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70(suppl 6):26-31.

Approximately one-half of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) will have partial or nonresponse to first-line antidepressant monotherapy, despite receiving an adequate dosage and sufficient duration of treatment.1 This has led to the definition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) as a depressive episode that has shown insufficient response to ≥1 trial of an antidepressant that has demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials.1 Depressed patients should be treated to full remission because absence of complete remission is associated with:

- a more recurrent and chronic illness course2,3

- increased medical and psychiatric comorbidities

- greater functional burden

- increased social and economic costs linked with impaired social functioning.4

Clinicians need to properly identify MDD and treatment resistance to guide optimal treatment choices. Additional tools are necessary to accurately identify, document, and communicate about symptoms commonly experienced by depressed patients but not fully characterized by DSM-IV-TR MDD criteria.5 Finally, in many cases, trait or situational factors might obfuscate accurate diagnosis and the natural course of illness, and tools that can be implemented practically will help identify patients with MDD.

Our group has created and implemented 2 clinician-administered tools—the SAFER Interview and the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ)—to enrich the qualitative assessment of MDD and treatment resistance.

SAFER: Assessing the diagnosis, symptom severity

The SAFER interview refines the diagnosis of depressed patients by assessing the state vs trait nature of the symptoms, their assessability, their face and ecological validity, and if they pass the rule of the 3 Ps: pervasiveness, persistence, and pathological nature of the current MDD episode (Table 1 and Table 2).6 This reliable assessment of the patient’s diagnosis and symptom severity is made in a way that reflects the illness in a real-world setting.

Clinical application of SAFER. Implementing SAFER in clinical settings promotes a personalized, dimensional approach by taking into account a varying degree of symptom severity in depressed patients, in contrast to relying on symptom lists as found in the DSM-IV-TR. Using the SAFER interview deepens the typical psychiatric diagnostic process, allows for a more precise understanding of the patient’s situation, and may help clinicians select effective treatments that target specific symptoms, thus resulting in more rapid alleviation of MDD.6

Table 1

The SAFER interview: Assessing depression in a real-world setting

State vs trait nature of the symptoms

|

Assessability

|

Face validity

|

Ecological validity

|

Rule of the 3 Ps

|

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

Table 2

The SAFER criteria: Rule of the 3 Ps

| Pervasive—Do the major symptoms affect the patient across multiple arenas of life (work, relationships, school, chores, etc.)? |

| Persistent—Do the main symptoms occur most days, most of the day during the current episode? |

| Pathological—Do the symptoms of the present episode interfere with functioning? |

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

CASE REPORT: Worsening symptoms

Ms. Y, age 53, has been depressed for 30 years. She hardly remembers a time in her life when she felt good for more than a few days. However, 2 months ago she noted her symptoms got worse. She presents with many MDD symptoms as assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, eg, ongoing depressive mood, feelings of guilt, major sleep disturbances, and work impairments.

Using SAFER to evaluate Ms. Y, a clinician would ask: Does she have symptoms that are present primarily during an episode of acute illness? Does the episode constitute a measurable exacerbation of preexisting symptoms? This clinical vignette illustrates the importance of the first SAFER criterion, state vs trait nature of the symptoms. Ms. Y is a SAFER “pass”—meaning consistent with a major depressive episode—because exacerbation of preexisting symptoms is measurable. However, if her symptoms represented a chronic, long-standing trait, she would be a SAFER “fail” based on this criterion, and her symptoms likely would not improve during a brief pharmacologic intervention. For such patients, SAFER would have oriented the clinician toward alternative therapies such as psychotherapy or a combination of longer, more complex pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy.

By helping clinicians refine MDD diagnoses, SAFER draws attention to specific depression entities (eg, MDD or dysthymia) and directs them toward appropriate guidelines, treatment algorithms, and precautions (eg, when treated with pharmacotherapy, dysthymic patients are particularly sensitive to unwanted effects and adherence is a serious issue).7 The SAFER interview also can help identify when what appears to be a depressive episode clearly is precipitated by situational factors, and is more likely to be influenced by changes in the patient’s life than by treatment. For such patients, first consider nonpharmacologic interventions to avoid unnecessary medication exposure.

ATRQ: Efficacy and adequacy

The ATRQ examines the efficacy (improvement from 0% [not improved at all] to 100% [completely improved]), and adequacy (adequate duration and dose) of any antidepressant treatment in a step-by-step procedure.1,8,9 For a copy of the ATRQ, click here.

While conducting the interview, clinicians ask about treatment adherence to each medication trial. A treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, from monotherapy to combination to augmentation.10 For each trial, the ATRQ systematically reviews 4 strategies to enhance treatment response:

- increasing the initial antidepressant dosage11

- combining the initial antidepressant with another antidepressant, typically from another class12

- augmenting the initial antidepressant with a nonantidepressant12

- switching from the initial antidepressant to another antidepressant.13

These strategies also are applied in cases of lost sustained antidepressant efficacy or depressive relapse/recurrence, although empirical evidence supporting these strategies is lacking, with the possible exception of dose increase.14,15

In the convention our group adopted, an adequate antidepressant trial must be ≥6 weeks in total length, with a dose within an adequate range as specified in the medication’s package insert. In addition, for the purposes of conducting TRD trials, we have considered a patient treatment-resistant if response to adequate dose and duration is <50%. On the ATRQ, 50% improvement refers to 50% symptom reduction from baseline without achieving remission. In an initial clinical trial that lasts ≥6 weeks, any dose increase (for ≥4 weeks) represents optimization and is not considered a new or separate trial, whereas augmentation or combination therapy (for ≥3 weeks) or a switch to another antidepressant (for ≥6 weeks) are considered new trials/treatments.

Decision tree for ATRQ. Because antidepressant treatment always is constrained by personal (eg, adherence, insurance coverage, etc.) and clinical (eg, contraindications due to comorbid conditions, side effects, etc.) considerations, we propose a decision tree to help clinicians determine the number of failed antidepressant trials their patient experienced (Figure). Although this tree does not represent all treatment scenarios, we hope it could help clinicians implement TRD treatment strategies because it highlights proper assessment of treatment duration, dosage, and changes before applying a TRD diagnosis.

The ATRQ meticulously examines patients’ antidepressant history to identify:

- pseudo-resistance, to guide adequate dosing and/or duration, and

- resistance, to propose next-step treatment.

Pseudo-resistance refers to treatment failures that can be attributed to factors such as inadequate treatment dosing or duration, atypical pharmacokinetics that reduce agents’ effectiveness, patient nonadherence (eg, due to adverse effects), or misdiagnosis of the primary disorder (ie, other mood disorders or depressive subsets such as dysthymia or minor depression mistreated as unipolar depression).16,17 Studies show that many patients with MDD referred to specialty settings are undertreated and receive inadequate antidepressant doses,18 which suggests that many referrals for TRD are in fact pseudo-resistance.19 Despite the lack of consensus on criteria for TRD,1 standardization of what constitutes treatment adequacy during antidepressant trials (eg, adherence, dose, duration) is indispensable.

Clinical application of the ATRQ. Because TRD may require specific interventions, we first need to properly identify treatment resistance. Also, systematic use of a classification system enhances the ability of clinicians and patients to provide meaningful descriptions of antidepressant resistance.

In clinical practice, choice of treatment strategy is based on factors that include partial or nonresponse, tolerability, avoiding withdrawal symptoms, the need to target side effects of a current antidepressant by administering another drug, cost, avoiding drug-drug interactions, and patient preference. Because a treatment-resistant patient may go through many types of trials, it is essential to obtain information about all treatments to determine the number of failed clinical trials a patient may have had for the current MDD episode and lifetime episodes. The importance of asking about adherence to each trial cannot be overemphasized.

Figure: Using the Massachusetts General Hospital Antidepressant Treatment History Questionnaire: A decision tree

CASE REPORT: Limited improvement

Mr. T, age 45, reported that his current depressive episode started several years ago. The first antidepressant trial he received, sertraline, 100 mg/d for 3 months, resulted in 0% improvement. Next he received citalopram, 20 mg/d, for 1 month, without any improvement. The next trial, venlafaxine, 75 mg/d, for 7 weeks, resulted in a 30% response. More recently Mr. B tried duloxetine, up to 90 mg/d, for 2 years with an 80% improvement during the first 3 months and then a decrease of response to <40%. He then received aripiprazole, 10 mg/d, in combination with duloxetine for approximately 4 weeks with no response.

Using the ATRQ to evaluate Mr. B, a clinician would consider the sertraline trial as a failed trial. The citalopram treatment would not be considered an adequate trial because it was too short. The venlafaxine course wouldn’t count as an adequate trial because the dosage was too low. The trial with duloxetine would count as a response (80% improvement) followed by a “poop out” or tachyphylaxis (40% improvement). The fifth trial with the combination of duloxetine and aripiprazole would count as a failed trial. The ATRQ highlights which drugs have been used for too short a duration or at too low a dosage. In Mr. B’s case, using the ATRQ revealed that of 5 trials, only 2 showed antidepressant resistance.

The ATRQ and decision tree are meant to provide clinicians with user-friendly tools to more precisely determine the number of failed antidepressant trials a patient experienced. By assessing if an antidepressant trial had an adequate dose and duration, the ATRQ can help suggest the next treatment options. For example, if a trial was inadequate in dose and/or duration but the patient tolerated the medication, then optimizing treatment with the current drug would be a logical next step. If a patient does not respond to an adequate trial, clinicians have several options, such as switching to another antidepressant, using a combination of medications or an augmentation strategy, or increasing the dose of the original antidepressant.

Limitations of the ATRQ. Historical rating of treatment is not as accurate as a prospective trial. Another limitation of the ATRQ is that the minimum effective dose is accepted as adequate; many clinicians would suggest that such a dose is inadequate. Also, the duration specified for augmentation, dose increase, and monotherapy are based on expert consensus1 rather than systematic research. Nonetheless, this method of documenting prior trials and treatment adequacy is an important advance.

The ATRQ lacks a place to indicate discontinuation due to intolerance. Knowing if adverse events caused treatment nonadherence or discontinuation is relevant to selecting treatment.

The ATRQ considers only pharmacotherapy and electroconvulsive therapy. Comprehensive assessment of treatment resistance requires asking about depression-specific, evidence-based psychotherapies, including cognitive-behavioral therapy and interpersonal therapy. Another precaution is that the ATRQ and SAFER should be used in conjunction with structured or semi-structured clinical interviews and other clinical tools to rule out other primary diagnoses (eg, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, or surreptitious substance abuse).20

Using SAFER and ATRQ allows clinicians to make a proper MDD diagnosis with an accurate, reliable assessment of symptom severity and a precise count of antidepressant trials of adequate duration and dose. SAFER helps differentiate MDD from other depressive disorders and can be used to separate MDD from a similar presentation of a reaction to external circumstances that may remit if these circumstances change.

These 2 clinical tools focus on MDD and TRD. Compared with treatment resistance in MDD, treatment resistance in other forms of depression, such as minor depressive disorder or dysthymia, has been inadequately researched21,22 and should be addressed in large studies. However, to help patients achieve remission of depressive disorders—especially MDD—clinicians should use patient information gathered via measurement-based care in combination with algorithm recommendations.23 Persistence of clinical care of MDD is essential because several treatment steps might be necessary for some patients to achieve remission. Throughout treatment, patients’ symptoms, adverse events secondary to ongoing treatment, and medication adherence should be assessed with appropriate tools. ATRQ and SAFER offer a clinician support in assessing treatment resistance history and a patient’s likelihood to respond to pharmacologic treatment.

Related Resources

- Desseilles M, Witte J, Chang TE, et al. Assessing the adequacy of past antidepressant trials: a clinician’s guide to the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ). J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(8):1152-1154.

- Targum SD, Pollack MH, Fava M. Redefining affective disorders: relevance for drug development. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14(1):2-9.

- Depression Clinical and Research Program. www.massgeneral.org/psychiatry/services/dcrp_home.aspx.

Drug Brand Names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Duloxetine • Cymbalta

- Sertraline • Zoloft

- Venlafaxine • Effexor

Disclosures

Dr. Desseilles was supported by the National Funds for Scientific Research of Belgium. Additional support came from the Belgian American Educational Foundation.

Dr. Fava receives grant/research support from, is a consultant to, and/or is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, Adamed, Advanced Meeting Partners, Affectis Pharmaceuticals, Alkermes, Amarin Pharma, American Psychiatric Association, American Society of Clinical Psychopharmacology, Aspect Medical Systems, AstraZeneca, Auspex Pharmaceuticals, Bayer, Belvoir Media Group, Best Practice Project Management, BioMarin, BioResearch, Biovail, Boehringer Ingelheim, BrainCells, Bristol-Myers Squibb, CeNeRx BioPharma, Cephalon, Clinical Trials Solutions, Clintara, CME Institute/Physicians Postgraduate Press, CNS Response, Compellis Pharmaceuticals, Covance, Covidien, Cypress Pharmaceutical, DiagnoSearch Life Sciences, Dainippon Sumitomo Pharma, Dov Pharmaceuticals, Edgemont Pharmaceuticals, Eisai, Eli Lilly and Company, EnVivo Pharmaceuticals, ePharmaSolutions, EPIX Pharmaceuticals, Euthymics Bioscience, Fabre-Kramer Pharmaceuticals, Forest Pharmaceuticals, Ganeden Biotech, GenOmind, GlaxoSmithKline, Grünenthal GmbH, Icon Clinical Research, Imedex, i3 Innovus/Ingenix, Janssen Pharmaceutica, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Knoll Pharmaceuticals, Labopharm, Lichtwer Pharma GmbH, Lorex Pharmaceuticals, Lundbeck, MedAvante, Merck, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Primedia, MGH Psychiatry Academy/Reed Elsevier, MSI Methylation Sciences, National Alliance for Research on Schizophrenia & Depression, National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, National Institute of Drug Abuse, National Institute of Mental Health, Naurex, Neuronetics, NextWave Pharmaceuticals, Novartis, Nutrition 21, Orexigen Therapeutics, Organon Pharmaceuticals, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals, PamLab, Pfizer, PharmaStar, Pharmavite®, PharmoRx Therapeutics, Photothera, Precision Human Biolaboratory, Prexa Pharmaceuticals, Puretech Ventures, PsychoGenics, Psylin Neurosciences, RCT Logic, Rexahn Pharmaceuticals, Ridge Diagnostics, Roche Pharmaceuticals, sanofi-aventis US, Schering-Plough, Sepracor, Servier Laboratories, Shire, Solvay Pharmaceuticals, Somaxon Pharmaceuticals, Somerset Pharmaceuticals, Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Supernus Pharmaceuticals, Synthelabo, Takeda Pharmaceutical, Tal Medical, Tetragenex Pharmaceuticals, Transcept Pharmaceuticals, TransForm Pharmaceuticals, United BioSource, Vanda Pharmaceuticals, and Wyeth-Ayerst Laboratories.

Over the past year, Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from the Bowman Family Foundation, FisherWallace, Ganeden, and Nordic Naturals. He has received honoraria for speaking from Nordic Naturals. He has received royalties from Lippincott Williams & Wilkins for the book Natural medications for psychiatric disorders: Considering the alternatives. No payment has exceeded $10,000.

Dr. Freeman has received research support from Eli Lilly and Company, Forest Laboratories, and GlaxoSmithKline, and served on a one-time advisory board to Bristol-Myers Squibb.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge Janet Witte, MD, MPH, Trina E. Chang, MD, MPH, Nadia Iovieno, MD, PhD, Christina Dording, MD, Heidi Ashih, MD, PhD, Maren Nyer, PhD, and Marasha-Fiona De Jong, MD from the Clinical Trials Network and Institute at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA.

Approximately one-half of patients with major depressive disorder (MDD) will have partial or nonresponse to first-line antidepressant monotherapy, despite receiving an adequate dosage and sufficient duration of treatment.1 This has led to the definition of treatment-resistant depression (TRD) as a depressive episode that has shown insufficient response to ≥1 trial of an antidepressant that has demonstrated efficacy in clinical trials.1 Depressed patients should be treated to full remission because absence of complete remission is associated with:

- a more recurrent and chronic illness course2,3

- increased medical and psychiatric comorbidities

- greater functional burden

- increased social and economic costs linked with impaired social functioning.4

Clinicians need to properly identify MDD and treatment resistance to guide optimal treatment choices. Additional tools are necessary to accurately identify, document, and communicate about symptoms commonly experienced by depressed patients but not fully characterized by DSM-IV-TR MDD criteria.5 Finally, in many cases, trait or situational factors might obfuscate accurate diagnosis and the natural course of illness, and tools that can be implemented practically will help identify patients with MDD.

Our group has created and implemented 2 clinician-administered tools—the SAFER Interview and the Antidepressant Treatment Response Questionnaire (ATRQ)—to enrich the qualitative assessment of MDD and treatment resistance.

SAFER: Assessing the diagnosis, symptom severity

The SAFER interview refines the diagnosis of depressed patients by assessing the state vs trait nature of the symptoms, their assessability, their face and ecological validity, and if they pass the rule of the 3 Ps: pervasiveness, persistence, and pathological nature of the current MDD episode (Table 1 and Table 2).6 This reliable assessment of the patient’s diagnosis and symptom severity is made in a way that reflects the illness in a real-world setting.

Clinical application of SAFER. Implementing SAFER in clinical settings promotes a personalized, dimensional approach by taking into account a varying degree of symptom severity in depressed patients, in contrast to relying on symptom lists as found in the DSM-IV-TR. Using the SAFER interview deepens the typical psychiatric diagnostic process, allows for a more precise understanding of the patient’s situation, and may help clinicians select effective treatments that target specific symptoms, thus resulting in more rapid alleviation of MDD.6

Table 1

The SAFER interview: Assessing depression in a real-world setting

State vs trait nature of the symptoms

|

Assessability

|

Face validity

|

Ecological validity

|

Rule of the 3 Ps

|

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

Table 2

The SAFER criteria: Rule of the 3 Ps

| Pervasive—Do the major symptoms affect the patient across multiple arenas of life (work, relationships, school, chores, etc.)? |

| Persistent—Do the main symptoms occur most days, most of the day during the current episode? |

| Pathological—Do the symptoms of the present episode interfere with functioning? |

| © Massachusetts General Hospital Source: Reference 6 |

CASE REPORT: Worsening symptoms

Ms. Y, age 53, has been depressed for 30 years. She hardly remembers a time in her life when she felt good for more than a few days. However, 2 months ago she noted her symptoms got worse. She presents with many MDD symptoms as assessed by the Hamilton Depression Rating Scale, eg, ongoing depressive mood, feelings of guilt, major sleep disturbances, and work impairments.

Using SAFER to evaluate Ms. Y, a clinician would ask: Does she have symptoms that are present primarily during an episode of acute illness? Does the episode constitute a measurable exacerbation of preexisting symptoms? This clinical vignette illustrates the importance of the first SAFER criterion, state vs trait nature of the symptoms. Ms. Y is a SAFER “pass”—meaning consistent with a major depressive episode—because exacerbation of preexisting symptoms is measurable. However, if her symptoms represented a chronic, long-standing trait, she would be a SAFER “fail” based on this criterion, and her symptoms likely would not improve during a brief pharmacologic intervention. For such patients, SAFER would have oriented the clinician toward alternative therapies such as psychotherapy or a combination of longer, more complex pharmacologic treatment and psychotherapy.

By helping clinicians refine MDD diagnoses, SAFER draws attention to specific depression entities (eg, MDD or dysthymia) and directs them toward appropriate guidelines, treatment algorithms, and precautions (eg, when treated with pharmacotherapy, dysthymic patients are particularly sensitive to unwanted effects and adherence is a serious issue).7 The SAFER interview also can help identify when what appears to be a depressive episode clearly is precipitated by situational factors, and is more likely to be influenced by changes in the patient’s life than by treatment. For such patients, first consider nonpharmacologic interventions to avoid unnecessary medication exposure.

ATRQ: Efficacy and adequacy