User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Beyond psychiatry’s reach: Fringe behaviors that defy treatment

Human nature is amazingly diverse. It is replete with behavioral quirks, oddities, eccentricities, and foibles. Most of these are idiosyncrasies that are outside the realm of psychopathology.

Frankly, the world would be a rather boring place without them. Contrary to the allegations that psychiatry medicalizes too many human behaviors that are in the “normal” range, only a small fraction of behavioral deviations are included in axis II of DSM-IV-TR. Unlike common peculiarities, the enduring personality disorders that psychiatrists diagnose and valiantly attempt to treat (no effective pharmacologic treatment has been approved for any of them) usually are significantly maladaptive and could lead to social or vocational dysfunction.

Many individuals exhibit “deplorable” behaviors that generally are frowned upon as a source of concern or are unlawful. Consider greed, bullying, chauvinism, fanaticism, extortion, demagoguery, or corruption. Very few, if any, of those who exhibit such fringe behaviors would consider seeking psychiatric help, although persons irked or injured by them wish they would. And what about bribery, power-seeking, malice, infidelity, laziness, mendacity, cheating, cruelty, narrow-mindedness, ruthlessness, and deceptiveness? Everyone has friends or relatives who exhibit such traits and flaunt them openly as a personal “brand.” Few such individuals would ever regard themselves as truly “flawed” or in need of change or professional help. In fact, those afflicted with such behavioral aberrations that are well outside the socially acceptable norms often are “successful” individuals who occupy prominent business or community roles despite their unendearing, even loathsome conduct. It sometimes appears that they have thrived despite their glaring lack of desirable social traits such as empathy, honesty, generosity, selflessness, and kindness.

Sometimes, it is not the oddities of behavior but extremes of political beliefs that can be most intriguing. They are reminiscent of delusions although they do not meet the DSM definition of delusional thinking (a fixed false belief inconsistent with one’s ethnic, cultural, educational, or religious background). Although real delusions are treatable with medications, para-delusional beliefs are not! A good example is the escalating prevalence of political fanaticism that has permeated society and dominated much of what used to be civilized discourse, even though most of the population continues to uphold middle-of-the-road political beliefs. The ideological polarization has even “infected” some media outlets, especially the free-wheeling blogosphere, where potentially venomous ideas are continuously spawned and instantly disseminated. Those who take diametrically opposite views often extend their conflicts over beliefs and ideas to personal hostilities and ad hominem attacks on “the other side.” This is an excellent example of how the entrenchment of beliefs and attitudes can directly shape behavior and transform an opinion into an “article of faith.”

Fanaticism is a long-standing human trait that has sparked wars and perpetuated prejudice and discrimination. Europe was ravaged by century-long wars instigated and fueled by religious fanaticism, proving that extreme beliefs can not only disrupt individual behavior but can impact cities, countries, and even the world, as depicted by World War II. Interestingly, when bizarre and fringe beliefs and behaviors are manifested on a large scale, it is regarded as political rather than psychopathological. Similarly, when religious beliefs become extreme, as sometimes happens in persons with acute bipolar mania, the unusual verbal output is regarded as a variant of religious exuberance rather than a psychiatric condition, which may delay medical treatment. It seems that in an age of intensifying secularism in developed western countries, political zealotry is the new religion!

Homo sapiens (wise man) is the only species that develops and harbors beliefs and whose behavior is inevitably guided, shaped, and determined by those beliefs. Obviously, some of our species’ beliefs are not consistently “wise,” but tenets can be vital to the health and survival of human individuals and communities. Émile Durkheim, the famous French sociologist, proposed in 1897 that “anomie,” or the lack of norms, values, and beliefs, is the main underpinning of suicide.1 On the other hand, psychiatrists generally attribute suicide to multiple other factors and anomie rarely is mentioned. However, Durkheim, like all humans, is entitled to his idiosyncratic belief!

Reference

1. Durkheim É. Le suicide; étude de sociologie. Paris, France: F. Alcan; 1897.

Human nature is amazingly diverse. It is replete with behavioral quirks, oddities, eccentricities, and foibles. Most of these are idiosyncrasies that are outside the realm of psychopathology.

Frankly, the world would be a rather boring place without them. Contrary to the allegations that psychiatry medicalizes too many human behaviors that are in the “normal” range, only a small fraction of behavioral deviations are included in axis II of DSM-IV-TR. Unlike common peculiarities, the enduring personality disorders that psychiatrists diagnose and valiantly attempt to treat (no effective pharmacologic treatment has been approved for any of them) usually are significantly maladaptive and could lead to social or vocational dysfunction.

Many individuals exhibit “deplorable” behaviors that generally are frowned upon as a source of concern or are unlawful. Consider greed, bullying, chauvinism, fanaticism, extortion, demagoguery, or corruption. Very few, if any, of those who exhibit such fringe behaviors would consider seeking psychiatric help, although persons irked or injured by them wish they would. And what about bribery, power-seeking, malice, infidelity, laziness, mendacity, cheating, cruelty, narrow-mindedness, ruthlessness, and deceptiveness? Everyone has friends or relatives who exhibit such traits and flaunt them openly as a personal “brand.” Few such individuals would ever regard themselves as truly “flawed” or in need of change or professional help. In fact, those afflicted with such behavioral aberrations that are well outside the socially acceptable norms often are “successful” individuals who occupy prominent business or community roles despite their unendearing, even loathsome conduct. It sometimes appears that they have thrived despite their glaring lack of desirable social traits such as empathy, honesty, generosity, selflessness, and kindness.

Sometimes, it is not the oddities of behavior but extremes of political beliefs that can be most intriguing. They are reminiscent of delusions although they do not meet the DSM definition of delusional thinking (a fixed false belief inconsistent with one’s ethnic, cultural, educational, or religious background). Although real delusions are treatable with medications, para-delusional beliefs are not! A good example is the escalating prevalence of political fanaticism that has permeated society and dominated much of what used to be civilized discourse, even though most of the population continues to uphold middle-of-the-road political beliefs. The ideological polarization has even “infected” some media outlets, especially the free-wheeling blogosphere, where potentially venomous ideas are continuously spawned and instantly disseminated. Those who take diametrically opposite views often extend their conflicts over beliefs and ideas to personal hostilities and ad hominem attacks on “the other side.” This is an excellent example of how the entrenchment of beliefs and attitudes can directly shape behavior and transform an opinion into an “article of faith.”

Fanaticism is a long-standing human trait that has sparked wars and perpetuated prejudice and discrimination. Europe was ravaged by century-long wars instigated and fueled by religious fanaticism, proving that extreme beliefs can not only disrupt individual behavior but can impact cities, countries, and even the world, as depicted by World War II. Interestingly, when bizarre and fringe beliefs and behaviors are manifested on a large scale, it is regarded as political rather than psychopathological. Similarly, when religious beliefs become extreme, as sometimes happens in persons with acute bipolar mania, the unusual verbal output is regarded as a variant of religious exuberance rather than a psychiatric condition, which may delay medical treatment. It seems that in an age of intensifying secularism in developed western countries, political zealotry is the new religion!

Homo sapiens (wise man) is the only species that develops and harbors beliefs and whose behavior is inevitably guided, shaped, and determined by those beliefs. Obviously, some of our species’ beliefs are not consistently “wise,” but tenets can be vital to the health and survival of human individuals and communities. Émile Durkheim, the famous French sociologist, proposed in 1897 that “anomie,” or the lack of norms, values, and beliefs, is the main underpinning of suicide.1 On the other hand, psychiatrists generally attribute suicide to multiple other factors and anomie rarely is mentioned. However, Durkheim, like all humans, is entitled to his idiosyncratic belief!

Human nature is amazingly diverse. It is replete with behavioral quirks, oddities, eccentricities, and foibles. Most of these are idiosyncrasies that are outside the realm of psychopathology.

Frankly, the world would be a rather boring place without them. Contrary to the allegations that psychiatry medicalizes too many human behaviors that are in the “normal” range, only a small fraction of behavioral deviations are included in axis II of DSM-IV-TR. Unlike common peculiarities, the enduring personality disorders that psychiatrists diagnose and valiantly attempt to treat (no effective pharmacologic treatment has been approved for any of them) usually are significantly maladaptive and could lead to social or vocational dysfunction.

Many individuals exhibit “deplorable” behaviors that generally are frowned upon as a source of concern or are unlawful. Consider greed, bullying, chauvinism, fanaticism, extortion, demagoguery, or corruption. Very few, if any, of those who exhibit such fringe behaviors would consider seeking psychiatric help, although persons irked or injured by them wish they would. And what about bribery, power-seeking, malice, infidelity, laziness, mendacity, cheating, cruelty, narrow-mindedness, ruthlessness, and deceptiveness? Everyone has friends or relatives who exhibit such traits and flaunt them openly as a personal “brand.” Few such individuals would ever regard themselves as truly “flawed” or in need of change or professional help. In fact, those afflicted with such behavioral aberrations that are well outside the socially acceptable norms often are “successful” individuals who occupy prominent business or community roles despite their unendearing, even loathsome conduct. It sometimes appears that they have thrived despite their glaring lack of desirable social traits such as empathy, honesty, generosity, selflessness, and kindness.

Sometimes, it is not the oddities of behavior but extremes of political beliefs that can be most intriguing. They are reminiscent of delusions although they do not meet the DSM definition of delusional thinking (a fixed false belief inconsistent with one’s ethnic, cultural, educational, or religious background). Although real delusions are treatable with medications, para-delusional beliefs are not! A good example is the escalating prevalence of political fanaticism that has permeated society and dominated much of what used to be civilized discourse, even though most of the population continues to uphold middle-of-the-road political beliefs. The ideological polarization has even “infected” some media outlets, especially the free-wheeling blogosphere, where potentially venomous ideas are continuously spawned and instantly disseminated. Those who take diametrically opposite views often extend their conflicts over beliefs and ideas to personal hostilities and ad hominem attacks on “the other side.” This is an excellent example of how the entrenchment of beliefs and attitudes can directly shape behavior and transform an opinion into an “article of faith.”

Fanaticism is a long-standing human trait that has sparked wars and perpetuated prejudice and discrimination. Europe was ravaged by century-long wars instigated and fueled by religious fanaticism, proving that extreme beliefs can not only disrupt individual behavior but can impact cities, countries, and even the world, as depicted by World War II. Interestingly, when bizarre and fringe beliefs and behaviors are manifested on a large scale, it is regarded as political rather than psychopathological. Similarly, when religious beliefs become extreme, as sometimes happens in persons with acute bipolar mania, the unusual verbal output is regarded as a variant of religious exuberance rather than a psychiatric condition, which may delay medical treatment. It seems that in an age of intensifying secularism in developed western countries, political zealotry is the new religion!

Homo sapiens (wise man) is the only species that develops and harbors beliefs and whose behavior is inevitably guided, shaped, and determined by those beliefs. Obviously, some of our species’ beliefs are not consistently “wise,” but tenets can be vital to the health and survival of human individuals and communities. Émile Durkheim, the famous French sociologist, proposed in 1897 that “anomie,” or the lack of norms, values, and beliefs, is the main underpinning of suicide.1 On the other hand, psychiatrists generally attribute suicide to multiple other factors and anomie rarely is mentioned. However, Durkheim, like all humans, is entitled to his idiosyncratic belief!

Reference

1. Durkheim É. Le suicide; étude de sociologie. Paris, France: F. Alcan; 1897.

Reference

1. Durkheim É. Le suicide; étude de sociologie. Paris, France: F. Alcan; 1897.

A paranoid, violent teenager

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Sleepless and paranoid

Ms. V, age 16, is referred to our psychiatric hospital from a juvenile detention center after she is charged with killing her sister with a hammer. She reports paranoid delusions, including believing that her sister was poisoning her food. Ms. V’s troubling behavior increased in the 6 months before the murder. She began to ask her mother to smell her food for possible poison. Her school grades dropped and she experienced decreased sleep and appetite. According to her mother, Ms. V’s insomnia worsened recently because of her paranoid thinking, which was evident when she noticed that her daughter slept with a hammer. Ms. V stopped socializing with her peers and no longer went to the gym.

Ms. V’s mother describes her daughter’s negative symptoms as consisting of social isolation and a flat affect. There was no evidence of auditory or visual hallucinations. After noticing the change in her daughter’s behavior, Ms. V’s mother attempted to schedule an appointment with a mental health professional, but there was a 2-month waiting list.

Ms. V cleaned her room before the murder, which was uncharacteristic of her routine behavior. On the day of the murder, Ms. V approached her sister while she was sleeping on the sofa and struck her on the head several times with a hammer. After the sister died, neighbors spotted Ms. V washing blood off her hands in their backyard with a sprinkler. Soaked in blood, she approached one of the neighbors and said that someone had been killed in the house. The neighbors called the police and Ms. V was arrested. She did not express remorse. She did not exhibit physical aggression toward others before the murder. Ms. V’s sense of entitlement and grandiosity persisted after the murder.

The authors’ observations

Paranoid delusions are fixed false beliefs with severe fears of others that may impair functioning at school or work, in personal relationships, and in other social dimensions. Paranoid thinking can have diverse presentations, ranging from social concerns such as fear of rejection to severe threat perceptions of people trying to cause substantial physical harm.1 Paranoid thoughts can be a result of misinterpretation of language, a personality disorder, anxiety, or psychosis.

Feelings of low self-esteem2 and anger1 may develop in a patient experiencing paranoid ideations. When anger begins to escalate, it may erupt into violent behavior. In Ms. V’s case, her paranoid ideations increased until she killed her younger sister. Ms. V’s case is similar to a mass shooting near Tucson, AZ on January 8, 2011 in that it possibly could have been prevented with earlier psychiatric intervention (Box).3-6

On January 8, 2011, a mass shooting occurred near Tucson, AZ that killed 6 and wounded 13. The suspect, 22-year-old Jared Lee Loughner, refused to cooperate with authorities by invoking his right to remain silent.3 Although the motives behind this crime remain undisclosed, mental illness appears to be a contributing factor.

Reports indicate that Mr. Loughner was abusing drugs and those close to him had noticed personality changes.4,5 The college he was attending advised Mr. Loughner to undergo a mental health evaluation, but he refused and dropped out of school.4,5 While in custody after the shooting, Mr. Loughner was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, deemed incompetent to stand trial, and ordered to receive psychiatric treatment.6

This tragic mass shooting and similar incidents have led to questions regarding the adequacy of the mental health care infrastructure in United States. Experts suggest that this tragedy could have been prevented with more aggressive psychiatric prevention and intervention. Critical analysis of similar recent cases and expert opinions are needed to address this problem effectively.

EVALUATION: Remorseless

At admission, Ms. V’s affect is restricted and, at times, inappropriate. She is guarded about discussing the homicide but describes paranoid thoughts about her sister poisoning her. She is eager to learn if the police had found poison in her food. Her speech is soft with good articulation. Based on her presentation, her intelligence is average. She shows no evidence of remorse and is preoccupied with her sister poisoning her.

The Rorschach Inkblot Technique reveals positive evidence for a severe thought disorder. Ms. V’s thinking seems regressed. Ms. V’s medical workup, including MRI, electroencephalogram, and laboratory tests, are all within normal limits.

In the 5th grade, Ms. V’s primary care provider prescribed amphetamine and dextroamphetamine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but she discontinued the drug after 1 year. Ms. V has never been hospitalized for psychiatric illness. She had no chronic medical conditions and no developmental delays.

Ms. V also has a history of periodic temper problems characterized by verbal aggression such as threatening the assistant principal at her school, and throwing her cellphone at her mother a few weeks before the murder, but no other aggressive episodes. Ms. V’s history does not suggest conduct disorder. She has no history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Ms. V has used alcohol since age 15, but her mother reports that she was not a heavy or frequent user. Her last reported alcohol use was 10 days before the murder. A maternal uncle had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Before the murder, Ms. V lived with her sister and mother. Her parents were divorced. At age 9, Ms. V was sexually abused by a soccer coach; however, she denied symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder related to the sexual abuse. She had no criminal history before the murder.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. V’s presentation and history, schizophrenia, paranoid type seems to be the most likely diagnosis because of her negative symptoms, including affective flattening, positive family history for schizophrenia, and paranoid delusions leading to dysfunction (Table).7 Delusional disorder seems less likely because Ms. V is young and has negative symptoms. Because she is generally healthy and her medical workup is negative, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition is ruled out. She does not appear to be over-reporting, malingering, or exaggerating symptoms. In the context of psychosis, adolescent psychopathy does not seem likely even though there is evidence of grandiosity and a lack of remorse.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia

A. Characteristic symptoms: ≥2 of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period:

|

| B. Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, ≥1 major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset |

| C. Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms that meet Criterion A and may include periods of prodromal or residual symptoms |

| D. Schizoaffective and mood disorder exclusion: Schizoaffective disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out because either (1) no major depressive, manic, or mixed episodes have occurred concurrently with the active-phase symptoms; or (2) if mood episodes have occurred during active-phase symptoms, their total duration has been brief relative to the duration of the active and residual periods |

| E. Substance/general medical condition exclusion: The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition |

| F. Relationship to a pervasive developmental disorder: If there is a history of autistic disorder or another pervasive developmental disorder, the additional diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present for at least 1 month |

| Diagnostic criteria for paranoid type: A type of schizophrenia in which the following criteria are met: A. Preoccupation with ≥1 delusions or frequent auditory hallucinations B. None of the following are prominent: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or flat or inappropriate affect |

| Source: Reference 7 |

The authors’ observations

Various treatments can be used for paranoia with aggression, but the severity of the paranoia should be assessed before initiating treatment. Although categorizing paranoid ideations as mild, moderate, and severe is mainly a clinical judgment, Freeman et al1 have attempted to design a paranoia hierarchy from social concerns to severe threats. CBT8 and antipsychotic medication may help reduce mild to moderate paranoid delusions, particularly those associated with schizophrenia or mood disorders. For severe paranoia, hospitalization should carefully be considered.

When a patient exhibits moderate paranoia, the probability of progressing to severe symptoms or improving to mild symptoms depends on several variables. Pharmacologic treatment, family insight, and social support may be important variables in such circumstances. Psychoeducation for the family is vital.

In patients experiencing paranoia, violence may be prevented by proper assessment and treatment. The patient’s family should be educated about paranoid ideation and the need for treatment to improve symptoms and ensure safety. The long-term effects of untreated paranoia and types of treatment modalities available should be discussed with the family and the patient. During these teaching sessions, focus on improving the overall insight of the family and the patient about the psychotic illness to improve treatment adherence.9 This step may be challenging if the family is resistant to the patient receiving mental health treatment.

Gaining a detailed clinical history of a patient’s paranoia is important. A clinician should look for changes in behavior, such as the patient becoming quieter or more hostile, and impaired academic or social functioning. After gathering sufficient evidence contrary to the delusion, clinicians can help patients improve their reality testing.

Rule out medical and neurologic conditions that may be contributing to paranoia and aggression.

TREATMENT: Some improvement

Ms. V is started on risperidone, 1 mg/d, which leads to a partial response. She starts interacting more with staff and her peers on the unit, but her delusions of her sister poisioning her persist. Given the severity of the crime, Ms. V is sent to adult court, where she is found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a state hospital.

The authors’ observations

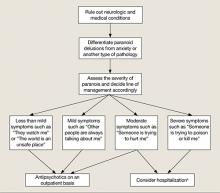

New-onset paranoia is a serious symptom that requires immediate evaluation and treatment. We recommend an approach presened in a flowchart (Figure) that highlights the importance of early intervention and aggressive treatment.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study10 indicated that a “suspicious” attitude toward others can be a precipitating cause for increased violence in some cases. In light of ongoing controversy regarding the link between violence and mental illnesses such as schizophrenia,10-12 addressing an individual’s psychiatric illness early is preferable to prevent possible complications such as violent crimes. Because patients with paranoid ideations may have severely impaired ego control, they may be at risk for acting out aggressive and/or destructive urges. Therefore, new-onset paranoia should be thought of as a medical emergency similar to chest pain. Although accurately predicting and preventing violence may be impossible, in Ms. V’s case, earlier mental health treatment and intervention may have been able to prevent a murder.

Figure: Paranoia: A suggested approach to treatment

aBased on clinical judgment and extent of social support

Symptoms may become less severe or more severe (bidirectional). Strong social support has a positive effect on all levels and complements therapy. Regular counseling sessions and enhanced family insight about the patient’s paranoia helps strengthen social support

- Marneros A, Pillmann F, Wustmann T. Delusional disorders—are they simply paranoid schizophrenia? [published online ahead of print November 15, 2010]. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq125.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Personal and clinical details of this case were altered to maintain patient confidentiality.

1. Freeman D, Garety PA, Bebbington PE, et al. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:427-435.

2. Kendler KS, Hays P. Paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder) and schizophrenia. A family history study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):547-551.

3. CNN Wire Staff. Police “actively pursuing” second person in Tucson shooting. CNN. http://us.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/01/08/arizona.shooting. Published January 9 2011. Accessed January 9, 2012.

4. Lipton E, Savage C, Shane S. Arizona suspect’s recent acts offer hints of alienation. The New York Times. January 8 2011:A8. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/us/politics/09shooter.html. Accessed January 10, 2012.

5. Berger J. Mental health warnings preceded rampage as Arizona gunman likely went untreated. http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/01/10/mental-health-warnings-preceded-arizona-rampage-evidence-gunman-sought. Published January 10, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2012.

6. Lacey M. Suspect in shooting of Giffords ruled unfit for trial. The New York Times. May 25 2011:A1. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/26/us/26loughner.html. Accessed January 5, 2012.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

8. Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):365-373.

9. Smith CM, Barzman DH, Pristach CA. Effect of patient and family insight on compliance of schizophrenic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(2):147-154.

10. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):566-572.

11. Mullen PE. A reassessment of the link between mental disorder and violent behaviour and its implications for clinical practice. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(1):3-11.

12. Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, et al. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000120.-

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Sleepless and paranoid

Ms. V, age 16, is referred to our psychiatric hospital from a juvenile detention center after she is charged with killing her sister with a hammer. She reports paranoid delusions, including believing that her sister was poisoning her food. Ms. V’s troubling behavior increased in the 6 months before the murder. She began to ask her mother to smell her food for possible poison. Her school grades dropped and she experienced decreased sleep and appetite. According to her mother, Ms. V’s insomnia worsened recently because of her paranoid thinking, which was evident when she noticed that her daughter slept with a hammer. Ms. V stopped socializing with her peers and no longer went to the gym.

Ms. V’s mother describes her daughter’s negative symptoms as consisting of social isolation and a flat affect. There was no evidence of auditory or visual hallucinations. After noticing the change in her daughter’s behavior, Ms. V’s mother attempted to schedule an appointment with a mental health professional, but there was a 2-month waiting list.

Ms. V cleaned her room before the murder, which was uncharacteristic of her routine behavior. On the day of the murder, Ms. V approached her sister while she was sleeping on the sofa and struck her on the head several times with a hammer. After the sister died, neighbors spotted Ms. V washing blood off her hands in their backyard with a sprinkler. Soaked in blood, she approached one of the neighbors and said that someone had been killed in the house. The neighbors called the police and Ms. V was arrested. She did not express remorse. She did not exhibit physical aggression toward others before the murder. Ms. V’s sense of entitlement and grandiosity persisted after the murder.

The authors’ observations

Paranoid delusions are fixed false beliefs with severe fears of others that may impair functioning at school or work, in personal relationships, and in other social dimensions. Paranoid thinking can have diverse presentations, ranging from social concerns such as fear of rejection to severe threat perceptions of people trying to cause substantial physical harm.1 Paranoid thoughts can be a result of misinterpretation of language, a personality disorder, anxiety, or psychosis.

Feelings of low self-esteem2 and anger1 may develop in a patient experiencing paranoid ideations. When anger begins to escalate, it may erupt into violent behavior. In Ms. V’s case, her paranoid ideations increased until she killed her younger sister. Ms. V’s case is similar to a mass shooting near Tucson, AZ on January 8, 2011 in that it possibly could have been prevented with earlier psychiatric intervention (Box).3-6

On January 8, 2011, a mass shooting occurred near Tucson, AZ that killed 6 and wounded 13. The suspect, 22-year-old Jared Lee Loughner, refused to cooperate with authorities by invoking his right to remain silent.3 Although the motives behind this crime remain undisclosed, mental illness appears to be a contributing factor.

Reports indicate that Mr. Loughner was abusing drugs and those close to him had noticed personality changes.4,5 The college he was attending advised Mr. Loughner to undergo a mental health evaluation, but he refused and dropped out of school.4,5 While in custody after the shooting, Mr. Loughner was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, deemed incompetent to stand trial, and ordered to receive psychiatric treatment.6

This tragic mass shooting and similar incidents have led to questions regarding the adequacy of the mental health care infrastructure in United States. Experts suggest that this tragedy could have been prevented with more aggressive psychiatric prevention and intervention. Critical analysis of similar recent cases and expert opinions are needed to address this problem effectively.

EVALUATION: Remorseless

At admission, Ms. V’s affect is restricted and, at times, inappropriate. She is guarded about discussing the homicide but describes paranoid thoughts about her sister poisoning her. She is eager to learn if the police had found poison in her food. Her speech is soft with good articulation. Based on her presentation, her intelligence is average. She shows no evidence of remorse and is preoccupied with her sister poisoning her.

The Rorschach Inkblot Technique reveals positive evidence for a severe thought disorder. Ms. V’s thinking seems regressed. Ms. V’s medical workup, including MRI, electroencephalogram, and laboratory tests, are all within normal limits.

In the 5th grade, Ms. V’s primary care provider prescribed amphetamine and dextroamphetamine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but she discontinued the drug after 1 year. Ms. V has never been hospitalized for psychiatric illness. She had no chronic medical conditions and no developmental delays.

Ms. V also has a history of periodic temper problems characterized by verbal aggression such as threatening the assistant principal at her school, and throwing her cellphone at her mother a few weeks before the murder, but no other aggressive episodes. Ms. V’s history does not suggest conduct disorder. She has no history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Ms. V has used alcohol since age 15, but her mother reports that she was not a heavy or frequent user. Her last reported alcohol use was 10 days before the murder. A maternal uncle had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Before the murder, Ms. V lived with her sister and mother. Her parents were divorced. At age 9, Ms. V was sexually abused by a soccer coach; however, she denied symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder related to the sexual abuse. She had no criminal history before the murder.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. V’s presentation and history, schizophrenia, paranoid type seems to be the most likely diagnosis because of her negative symptoms, including affective flattening, positive family history for schizophrenia, and paranoid delusions leading to dysfunction (Table).7 Delusional disorder seems less likely because Ms. V is young and has negative symptoms. Because she is generally healthy and her medical workup is negative, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition is ruled out. She does not appear to be over-reporting, malingering, or exaggerating symptoms. In the context of psychosis, adolescent psychopathy does not seem likely even though there is evidence of grandiosity and a lack of remorse.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia

A. Characteristic symptoms: ≥2 of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period:

|

| B. Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, ≥1 major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset |

| C. Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms that meet Criterion A and may include periods of prodromal or residual symptoms |

| D. Schizoaffective and mood disorder exclusion: Schizoaffective disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out because either (1) no major depressive, manic, or mixed episodes have occurred concurrently with the active-phase symptoms; or (2) if mood episodes have occurred during active-phase symptoms, their total duration has been brief relative to the duration of the active and residual periods |

| E. Substance/general medical condition exclusion: The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition |

| F. Relationship to a pervasive developmental disorder: If there is a history of autistic disorder or another pervasive developmental disorder, the additional diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present for at least 1 month |

| Diagnostic criteria for paranoid type: A type of schizophrenia in which the following criteria are met: A. Preoccupation with ≥1 delusions or frequent auditory hallucinations B. None of the following are prominent: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or flat or inappropriate affect |

| Source: Reference 7 |

The authors’ observations

Various treatments can be used for paranoia with aggression, but the severity of the paranoia should be assessed before initiating treatment. Although categorizing paranoid ideations as mild, moderate, and severe is mainly a clinical judgment, Freeman et al1 have attempted to design a paranoia hierarchy from social concerns to severe threats. CBT8 and antipsychotic medication may help reduce mild to moderate paranoid delusions, particularly those associated with schizophrenia or mood disorders. For severe paranoia, hospitalization should carefully be considered.

When a patient exhibits moderate paranoia, the probability of progressing to severe symptoms or improving to mild symptoms depends on several variables. Pharmacologic treatment, family insight, and social support may be important variables in such circumstances. Psychoeducation for the family is vital.

In patients experiencing paranoia, violence may be prevented by proper assessment and treatment. The patient’s family should be educated about paranoid ideation and the need for treatment to improve symptoms and ensure safety. The long-term effects of untreated paranoia and types of treatment modalities available should be discussed with the family and the patient. During these teaching sessions, focus on improving the overall insight of the family and the patient about the psychotic illness to improve treatment adherence.9 This step may be challenging if the family is resistant to the patient receiving mental health treatment.

Gaining a detailed clinical history of a patient’s paranoia is important. A clinician should look for changes in behavior, such as the patient becoming quieter or more hostile, and impaired academic or social functioning. After gathering sufficient evidence contrary to the delusion, clinicians can help patients improve their reality testing.

Rule out medical and neurologic conditions that may be contributing to paranoia and aggression.

TREATMENT: Some improvement

Ms. V is started on risperidone, 1 mg/d, which leads to a partial response. She starts interacting more with staff and her peers on the unit, but her delusions of her sister poisioning her persist. Given the severity of the crime, Ms. V is sent to adult court, where she is found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a state hospital.

The authors’ observations

New-onset paranoia is a serious symptom that requires immediate evaluation and treatment. We recommend an approach presened in a flowchart (Figure) that highlights the importance of early intervention and aggressive treatment.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study10 indicated that a “suspicious” attitude toward others can be a precipitating cause for increased violence in some cases. In light of ongoing controversy regarding the link between violence and mental illnesses such as schizophrenia,10-12 addressing an individual’s psychiatric illness early is preferable to prevent possible complications such as violent crimes. Because patients with paranoid ideations may have severely impaired ego control, they may be at risk for acting out aggressive and/or destructive urges. Therefore, new-onset paranoia should be thought of as a medical emergency similar to chest pain. Although accurately predicting and preventing violence may be impossible, in Ms. V’s case, earlier mental health treatment and intervention may have been able to prevent a murder.

Figure: Paranoia: A suggested approach to treatment

aBased on clinical judgment and extent of social support

Symptoms may become less severe or more severe (bidirectional). Strong social support has a positive effect on all levels and complements therapy. Regular counseling sessions and enhanced family insight about the patient’s paranoia helps strengthen social support

- Marneros A, Pillmann F, Wustmann T. Delusional disorders—are they simply paranoid schizophrenia? [published online ahead of print November 15, 2010]. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq125.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Personal and clinical details of this case were altered to maintain patient confidentiality.

Discuss this article at www.facebook.com/CurrentPsychiatry

CASE: Sleepless and paranoid

Ms. V, age 16, is referred to our psychiatric hospital from a juvenile detention center after she is charged with killing her sister with a hammer. She reports paranoid delusions, including believing that her sister was poisoning her food. Ms. V’s troubling behavior increased in the 6 months before the murder. She began to ask her mother to smell her food for possible poison. Her school grades dropped and she experienced decreased sleep and appetite. According to her mother, Ms. V’s insomnia worsened recently because of her paranoid thinking, which was evident when she noticed that her daughter slept with a hammer. Ms. V stopped socializing with her peers and no longer went to the gym.

Ms. V’s mother describes her daughter’s negative symptoms as consisting of social isolation and a flat affect. There was no evidence of auditory or visual hallucinations. After noticing the change in her daughter’s behavior, Ms. V’s mother attempted to schedule an appointment with a mental health professional, but there was a 2-month waiting list.

Ms. V cleaned her room before the murder, which was uncharacteristic of her routine behavior. On the day of the murder, Ms. V approached her sister while she was sleeping on the sofa and struck her on the head several times with a hammer. After the sister died, neighbors spotted Ms. V washing blood off her hands in their backyard with a sprinkler. Soaked in blood, she approached one of the neighbors and said that someone had been killed in the house. The neighbors called the police and Ms. V was arrested. She did not express remorse. She did not exhibit physical aggression toward others before the murder. Ms. V’s sense of entitlement and grandiosity persisted after the murder.

The authors’ observations

Paranoid delusions are fixed false beliefs with severe fears of others that may impair functioning at school or work, in personal relationships, and in other social dimensions. Paranoid thinking can have diverse presentations, ranging from social concerns such as fear of rejection to severe threat perceptions of people trying to cause substantial physical harm.1 Paranoid thoughts can be a result of misinterpretation of language, a personality disorder, anxiety, or psychosis.

Feelings of low self-esteem2 and anger1 may develop in a patient experiencing paranoid ideations. When anger begins to escalate, it may erupt into violent behavior. In Ms. V’s case, her paranoid ideations increased until she killed her younger sister. Ms. V’s case is similar to a mass shooting near Tucson, AZ on January 8, 2011 in that it possibly could have been prevented with earlier psychiatric intervention (Box).3-6

On January 8, 2011, a mass shooting occurred near Tucson, AZ that killed 6 and wounded 13. The suspect, 22-year-old Jared Lee Loughner, refused to cooperate with authorities by invoking his right to remain silent.3 Although the motives behind this crime remain undisclosed, mental illness appears to be a contributing factor.

Reports indicate that Mr. Loughner was abusing drugs and those close to him had noticed personality changes.4,5 The college he was attending advised Mr. Loughner to undergo a mental health evaluation, but he refused and dropped out of school.4,5 While in custody after the shooting, Mr. Loughner was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia, deemed incompetent to stand trial, and ordered to receive psychiatric treatment.6

This tragic mass shooting and similar incidents have led to questions regarding the adequacy of the mental health care infrastructure in United States. Experts suggest that this tragedy could have been prevented with more aggressive psychiatric prevention and intervention. Critical analysis of similar recent cases and expert opinions are needed to address this problem effectively.

EVALUATION: Remorseless

At admission, Ms. V’s affect is restricted and, at times, inappropriate. She is guarded about discussing the homicide but describes paranoid thoughts about her sister poisoning her. She is eager to learn if the police had found poison in her food. Her speech is soft with good articulation. Based on her presentation, her intelligence is average. She shows no evidence of remorse and is preoccupied with her sister poisoning her.

The Rorschach Inkblot Technique reveals positive evidence for a severe thought disorder. Ms. V’s thinking seems regressed. Ms. V’s medical workup, including MRI, electroencephalogram, and laboratory tests, are all within normal limits.

In the 5th grade, Ms. V’s primary care provider prescribed amphetamine and dextroamphetamine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, but she discontinued the drug after 1 year. Ms. V has never been hospitalized for psychiatric illness. She had no chronic medical conditions and no developmental delays.

Ms. V also has a history of periodic temper problems characterized by verbal aggression such as threatening the assistant principal at her school, and throwing her cellphone at her mother a few weeks before the murder, but no other aggressive episodes. Ms. V’s history does not suggest conduct disorder. She has no history of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts. Ms. V has used alcohol since age 15, but her mother reports that she was not a heavy or frequent user. Her last reported alcohol use was 10 days before the murder. A maternal uncle had been diagnosed with schizophrenia.

Before the murder, Ms. V lived with her sister and mother. Her parents were divorced. At age 9, Ms. V was sexually abused by a soccer coach; however, she denied symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder related to the sexual abuse. She had no criminal history before the murder.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. V’s presentation and history, schizophrenia, paranoid type seems to be the most likely diagnosis because of her negative symptoms, including affective flattening, positive family history for schizophrenia, and paranoid delusions leading to dysfunction (Table).7 Delusional disorder seems less likely because Ms. V is young and has negative symptoms. Because she is generally healthy and her medical workup is negative, psychotic disorder due to a general medical condition is ruled out. She does not appear to be over-reporting, malingering, or exaggerating symptoms. In the context of psychosis, adolescent psychopathy does not seem likely even though there is evidence of grandiosity and a lack of remorse.

Table

DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia

A. Characteristic symptoms: ≥2 of the following, each present for a significant portion of time during a 1-month period:

|

| B. Social/occupational dysfunction: For a significant portion of the time since the onset of the disturbance, ≥1 major areas of functioning such as work, interpersonal relations, or self-care are markedly below the level achieved prior to the onset |

| C. Duration: Continuous signs of the disturbance persist for at least 6 months. This 6-month period must include at least 1 month of symptoms that meet Criterion A and may include periods of prodromal or residual symptoms |

| D. Schizoaffective and mood disorder exclusion: Schizoaffective disorder and mood disorder with psychotic features have been ruled out because either (1) no major depressive, manic, or mixed episodes have occurred concurrently with the active-phase symptoms; or (2) if mood episodes have occurred during active-phase symptoms, their total duration has been brief relative to the duration of the active and residual periods |

| E. Substance/general medical condition exclusion: The disturbance is not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance or a general medical condition |

| F. Relationship to a pervasive developmental disorder: If there is a history of autistic disorder or another pervasive developmental disorder, the additional diagnosis of schizophrenia is made only if prominent delusions or hallucinations are also present for at least 1 month |

| Diagnostic criteria for paranoid type: A type of schizophrenia in which the following criteria are met: A. Preoccupation with ≥1 delusions or frequent auditory hallucinations B. None of the following are prominent: disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or flat or inappropriate affect |

| Source: Reference 7 |

The authors’ observations

Various treatments can be used for paranoia with aggression, but the severity of the paranoia should be assessed before initiating treatment. Although categorizing paranoid ideations as mild, moderate, and severe is mainly a clinical judgment, Freeman et al1 have attempted to design a paranoia hierarchy from social concerns to severe threats. CBT8 and antipsychotic medication may help reduce mild to moderate paranoid delusions, particularly those associated with schizophrenia or mood disorders. For severe paranoia, hospitalization should carefully be considered.

When a patient exhibits moderate paranoia, the probability of progressing to severe symptoms or improving to mild symptoms depends on several variables. Pharmacologic treatment, family insight, and social support may be important variables in such circumstances. Psychoeducation for the family is vital.

In patients experiencing paranoia, violence may be prevented by proper assessment and treatment. The patient’s family should be educated about paranoid ideation and the need for treatment to improve symptoms and ensure safety. The long-term effects of untreated paranoia and types of treatment modalities available should be discussed with the family and the patient. During these teaching sessions, focus on improving the overall insight of the family and the patient about the psychotic illness to improve treatment adherence.9 This step may be challenging if the family is resistant to the patient receiving mental health treatment.

Gaining a detailed clinical history of a patient’s paranoia is important. A clinician should look for changes in behavior, such as the patient becoming quieter or more hostile, and impaired academic or social functioning. After gathering sufficient evidence contrary to the delusion, clinicians can help patients improve their reality testing.

Rule out medical and neurologic conditions that may be contributing to paranoia and aggression.

TREATMENT: Some improvement

Ms. V is started on risperidone, 1 mg/d, which leads to a partial response. She starts interacting more with staff and her peers on the unit, but her delusions of her sister poisioning her persist. Given the severity of the crime, Ms. V is sent to adult court, where she is found not guilty by reason of insanity and committed to a state hospital.

The authors’ observations

New-onset paranoia is a serious symptom that requires immediate evaluation and treatment. We recommend an approach presened in a flowchart (Figure) that highlights the importance of early intervention and aggressive treatment.

The MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study10 indicated that a “suspicious” attitude toward others can be a precipitating cause for increased violence in some cases. In light of ongoing controversy regarding the link between violence and mental illnesses such as schizophrenia,10-12 addressing an individual’s psychiatric illness early is preferable to prevent possible complications such as violent crimes. Because patients with paranoid ideations may have severely impaired ego control, they may be at risk for acting out aggressive and/or destructive urges. Therefore, new-onset paranoia should be thought of as a medical emergency similar to chest pain. Although accurately predicting and preventing violence may be impossible, in Ms. V’s case, earlier mental health treatment and intervention may have been able to prevent a murder.

Figure: Paranoia: A suggested approach to treatment

aBased on clinical judgment and extent of social support

Symptoms may become less severe or more severe (bidirectional). Strong social support has a positive effect on all levels and complements therapy. Regular counseling sessions and enhanced family insight about the patient’s paranoia helps strengthen social support

- Marneros A, Pillmann F, Wustmann T. Delusional disorders—are they simply paranoid schizophrenia? [published online ahead of print November 15, 2010]. Schizophr Bull. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbq125.

Drug Brand Names

Amphetamine and dextroamphetamine • Adderall

Risperidone • Risperdal

Disclosures

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Personal and clinical details of this case were altered to maintain patient confidentiality.

1. Freeman D, Garety PA, Bebbington PE, et al. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:427-435.

2. Kendler KS, Hays P. Paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder) and schizophrenia. A family history study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):547-551.

3. CNN Wire Staff. Police “actively pursuing” second person in Tucson shooting. CNN. http://us.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/01/08/arizona.shooting. Published January 9 2011. Accessed January 9, 2012.

4. Lipton E, Savage C, Shane S. Arizona suspect’s recent acts offer hints of alienation. The New York Times. January 8 2011:A8. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/us/politics/09shooter.html. Accessed January 10, 2012.

5. Berger J. Mental health warnings preceded rampage as Arizona gunman likely went untreated. http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/01/10/mental-health-warnings-preceded-arizona-rampage-evidence-gunman-sought. Published January 10, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2012.

6. Lacey M. Suspect in shooting of Giffords ruled unfit for trial. The New York Times. May 25 2011:A1. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/26/us/26loughner.html. Accessed January 5, 2012.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

8. Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):365-373.

9. Smith CM, Barzman DH, Pristach CA. Effect of patient and family insight on compliance of schizophrenic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(2):147-154.

10. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):566-572.

11. Mullen PE. A reassessment of the link between mental disorder and violent behaviour and its implications for clinical practice. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(1):3-11.

12. Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, et al. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000120.-

1. Freeman D, Garety PA, Bebbington PE, et al. Psychological investigation of the structure of paranoia in a non-clinical population. Br J Psychiatry. 2005;186:427-435.

2. Kendler KS, Hays P. Paranoid psychosis (delusional disorder) and schizophrenia. A family history study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1981;38(5):547-551.

3. CNN Wire Staff. Police “actively pursuing” second person in Tucson shooting. CNN. http://us.cnn.com/2011/CRIME/01/08/arizona.shooting. Published January 9 2011. Accessed January 9, 2012.

4. Lipton E, Savage C, Shane S. Arizona suspect’s recent acts offer hints of alienation. The New York Times. January 8 2011:A8. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/01/09/us/politics/09shooter.html. Accessed January 10, 2012.

5. Berger J. Mental health warnings preceded rampage as Arizona gunman likely went untreated. http://www.foxnews.com/us/2011/01/10/mental-health-warnings-preceded-arizona-rampage-evidence-gunman-sought. Published January 10, 2011. Accessed January 11, 2012.

6. Lacey M. Suspect in shooting of Giffords ruled unfit for trial. The New York Times. May 25 2011:A1. http://www.nytimes.com/2011/05/26/us/26loughner.html. Accessed January 5, 2012.

7. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

8. Turkington D, Kingdon D, Weiden PJ. Cognitive behavior therapy for schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(3):365-373.

9. Smith CM, Barzman DH, Pristach CA. Effect of patient and family insight on compliance of schizophrenic patients. J Clin Pharmacol. 1997;37(2):147-154.

10. Appelbaum PS, Robbins PC, Monahan J. Violence and delusions: data from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157(4):566-572.

11. Mullen PE. A reassessment of the link between mental disorder and violent behaviour and its implications for clinical practice. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 1997;31(1):3-11.

12. Fazel S, Gulati G, Linsell L, et al. Schizophrenia and violence: systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS Med. 2009;6(8):e1000120.-

Identifying and treating factors that put patients at risk for suicide

Enhancing psychiatric care: A decade of progress

One of the greatest challenges for busy clinicians, such as Current Psychiatry readers, is keeping up with advances in the field of psychiatry in our limited available time. Because psychiatry is one of the most rapidly expanding medical specialties, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, and other mental health clinicians recognize the importance of ongoing self-driven learning to make sure they are practicing the latest standards of care in diagnosis and treatment.

Although continuously acquiring new knowledge that can improve patient care is stimulating and necessary, it also may be intimidating because most medical journals are packed with studies with arcane methodology, complicated designs, complex statistics, dense tables, and busy figures. Wading through the literature can be time-consuming—and even exhausting—for a busy clinician with limited time to learn the latest research findings, and this approach is not always guaranteed to provide the relevant “take-home nuggets” that can enhance clinical practice.

Enter Current Psychiatry. Established in 2002 as the brainchild of former University of Cincinnati Department of Psychiatry Chair Randy Hillard, MD (now Editor-in-Chief Emeritus) and publisher Thomas Pizor, Current Psychiatry was designed precisely to fill this vital unmet need for busy clinical psychiatrists.1 Current Psychiatry provides practical, peer-reviewed, evidence-based reviews that are highly relevant to the realities of clinical psychiatric practice. Nationally recognized experts write articles about topics identified as “valued” by practitioners based on systematic surveys of clinicians in various community settings. A diverse editorial board of prominent academic teachers and researchers provides an ongoing stream of diverse articles and perspectives that distill the emerging science and practice of psychiatry into immediately useful applications.

From our first issue, Current Psychiatry has presented information that readers could use to care for their patients, in articles such as:

- Using antipsychotics in patients with dementia (Kasckow JW, et al; February 2004)

- How to reduce mania risk when prescribing stimulants (Dubovsky SL, et al; October 2005)

- Hypnotics and driving: FDA action, clinical trials show need for precautions (Freeman B, et al; April 2007)

- Fibromyalgia: Psychiatric drugs target CNS-linked symptoms (Stanford SB; March 2009)

- The re-emerging role of therapeutic neuromodulation (Janicak PG, et al; November 2010)

The impact has been spectacular. As Current Psychiatry celebrates its 10th anniversary this month, we can relish its remarkable growth and success. In independent readership surveys, Current Psychiatry has grown to become the most widely read non-tabloid psychiatry journal.2 As Editor-in-Chief, I derive great satisfaction from the rave reviews I receive from my colleagues around the country about how they regard Current Psychiatry as their number 1 resource for clinical updates. Stellar feedback such as this indicates that Current Psychiatry clearly meets clinicians’ educational needs.

However, we are not resting on our laurels. Current Psychiatry has continued to innovate and develop new approaches to ongoing self-education by growing its online presence. The offerings at CurrentPsychiatry.com have steadily increased to include the following features:

Online-exclusive content. CurrentPsychiatry.com provides additional resources such as tables, boxes, algorithms, and/or figures related to articles from the printed edition. Later this year, as our 10th anniversary initiative for you, our readers, Current Psychiatry will offer complete online-exclusive articles that will be listed on the table of contents but published only on CurrentPsychiatry.com.

Multimedia library. Every month, the author of 1 article is invited to participate in a brief (5- to 10-minute) audiocast in which he or she provides additional commentary on clinical topics related to the article. This library currently houses nearly 50 audiocasts. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages.asp?id=6412.

Continuing Medical Education (CME). This section of our Web site provides peer-reviewed education programs that offer visitors the opportunity to earn free CME credits on a range of clinical topics, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and more. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages_cme.asp.

Supplements. Recent topics covered in these peer-reviewed, non-CME programs include managing schizophrenia, transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression, and more. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages_supplement.asp.

Going beyond our printed and online content, Current Psychiatry serves our readers’ educational needs through CME meetings such as the annual Psychiatry Update, which is hosted in conjunction with the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. The next meeting will take place March 29 to 31, 2012 in Chicago, IL and will offer a maximum of 18 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM (For more information, click here.). In addition, Current Psychiatry co-sponsors the University of Cincinnati’s Annual Psychopharmacology Update, which is scheduled for October 20, 2012 in Cincinnati, OH, offering AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM.

One of the gratifying aspects of producing a highly relevant educational vehicle such as Current Psychiatry is that my trainees at the University of Cincinnati tell me how useful they find it for their clinical practice. I am glad that they already have developed the good habit of reading Current Psychiatry from cover to cover during their training!

On behalf of Current Psychiatry’s Deputy Editor, Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, our Editorial Consultants, Section Editors, Associate Editors, editorial staff, and publishing staff, we thank you, our loyal readers, for valuing what we do and using the knowledge provided by Current Psychiatry to manage various psychiatric populations with the latest nosological and therapeutic advances. We invite you to continue interacting with us in person, by e-mail, or via CurrentPsychiatry.com and tell us how we can continue to meet your educational needs. We find it very rewarding to hear from you.

1. Hillard JR. Here is why we do need a new psychiatry journal. Current Psychiatry. 2002;1(1):7. -http://www.currentpsychiatry.com/article_pages.asp?AID=465&UID=44140

2. Kantar Media. June 2011 Medical/Surgical Readership Study. Psychiatry. New York, NY: Kantar Media; 2011.

One of the greatest challenges for busy clinicians, such as Current Psychiatry readers, is keeping up with advances in the field of psychiatry in our limited available time. Because psychiatry is one of the most rapidly expanding medical specialties, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, and other mental health clinicians recognize the importance of ongoing self-driven learning to make sure they are practicing the latest standards of care in diagnosis and treatment.

Although continuously acquiring new knowledge that can improve patient care is stimulating and necessary, it also may be intimidating because most medical journals are packed with studies with arcane methodology, complicated designs, complex statistics, dense tables, and busy figures. Wading through the literature can be time-consuming—and even exhausting—for a busy clinician with limited time to learn the latest research findings, and this approach is not always guaranteed to provide the relevant “take-home nuggets” that can enhance clinical practice.

Enter Current Psychiatry. Established in 2002 as the brainchild of former University of Cincinnati Department of Psychiatry Chair Randy Hillard, MD (now Editor-in-Chief Emeritus) and publisher Thomas Pizor, Current Psychiatry was designed precisely to fill this vital unmet need for busy clinical psychiatrists.1 Current Psychiatry provides practical, peer-reviewed, evidence-based reviews that are highly relevant to the realities of clinical psychiatric practice. Nationally recognized experts write articles about topics identified as “valued” by practitioners based on systematic surveys of clinicians in various community settings. A diverse editorial board of prominent academic teachers and researchers provides an ongoing stream of diverse articles and perspectives that distill the emerging science and practice of psychiatry into immediately useful applications.

From our first issue, Current Psychiatry has presented information that readers could use to care for their patients, in articles such as:

- Using antipsychotics in patients with dementia (Kasckow JW, et al; February 2004)

- How to reduce mania risk when prescribing stimulants (Dubovsky SL, et al; October 2005)

- Hypnotics and driving: FDA action, clinical trials show need for precautions (Freeman B, et al; April 2007)

- Fibromyalgia: Psychiatric drugs target CNS-linked symptoms (Stanford SB; March 2009)

- The re-emerging role of therapeutic neuromodulation (Janicak PG, et al; November 2010)

The impact has been spectacular. As Current Psychiatry celebrates its 10th anniversary this month, we can relish its remarkable growth and success. In independent readership surveys, Current Psychiatry has grown to become the most widely read non-tabloid psychiatry journal.2 As Editor-in-Chief, I derive great satisfaction from the rave reviews I receive from my colleagues around the country about how they regard Current Psychiatry as their number 1 resource for clinical updates. Stellar feedback such as this indicates that Current Psychiatry clearly meets clinicians’ educational needs.

However, we are not resting on our laurels. Current Psychiatry has continued to innovate and develop new approaches to ongoing self-education by growing its online presence. The offerings at CurrentPsychiatry.com have steadily increased to include the following features:

Online-exclusive content. CurrentPsychiatry.com provides additional resources such as tables, boxes, algorithms, and/or figures related to articles from the printed edition. Later this year, as our 10th anniversary initiative for you, our readers, Current Psychiatry will offer complete online-exclusive articles that will be listed on the table of contents but published only on CurrentPsychiatry.com.

Multimedia library. Every month, the author of 1 article is invited to participate in a brief (5- to 10-minute) audiocast in which he or she provides additional commentary on clinical topics related to the article. This library currently houses nearly 50 audiocasts. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages.asp?id=6412.

Continuing Medical Education (CME). This section of our Web site provides peer-reviewed education programs that offer visitors the opportunity to earn free CME credits on a range of clinical topics, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and more. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages_cme.asp.

Supplements. Recent topics covered in these peer-reviewed, non-CME programs include managing schizophrenia, transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression, and more. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages_supplement.asp.

Going beyond our printed and online content, Current Psychiatry serves our readers’ educational needs through CME meetings such as the annual Psychiatry Update, which is hosted in conjunction with the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists. The next meeting will take place March 29 to 31, 2012 in Chicago, IL and will offer a maximum of 18 AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM (For more information, click here.). In addition, Current Psychiatry co-sponsors the University of Cincinnati’s Annual Psychopharmacology Update, which is scheduled for October 20, 2012 in Cincinnati, OH, offering AMA PRA Category 1 CreditsTM.

One of the gratifying aspects of producing a highly relevant educational vehicle such as Current Psychiatry is that my trainees at the University of Cincinnati tell me how useful they find it for their clinical practice. I am glad that they already have developed the good habit of reading Current Psychiatry from cover to cover during their training!

On behalf of Current Psychiatry’s Deputy Editor, Joseph F. Goldberg, MD, our Editorial Consultants, Section Editors, Associate Editors, editorial staff, and publishing staff, we thank you, our loyal readers, for valuing what we do and using the knowledge provided by Current Psychiatry to manage various psychiatric populations with the latest nosological and therapeutic advances. We invite you to continue interacting with us in person, by e-mail, or via CurrentPsychiatry.com and tell us how we can continue to meet your educational needs. We find it very rewarding to hear from you.

One of the greatest challenges for busy clinicians, such as Current Psychiatry readers, is keeping up with advances in the field of psychiatry in our limited available time. Because psychiatry is one of the most rapidly expanding medical specialties, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurse practitioners, and other mental health clinicians recognize the importance of ongoing self-driven learning to make sure they are practicing the latest standards of care in diagnosis and treatment.

Although continuously acquiring new knowledge that can improve patient care is stimulating and necessary, it also may be intimidating because most medical journals are packed with studies with arcane methodology, complicated designs, complex statistics, dense tables, and busy figures. Wading through the literature can be time-consuming—and even exhausting—for a busy clinician with limited time to learn the latest research findings, and this approach is not always guaranteed to provide the relevant “take-home nuggets” that can enhance clinical practice.

Enter Current Psychiatry. Established in 2002 as the brainchild of former University of Cincinnati Department of Psychiatry Chair Randy Hillard, MD (now Editor-in-Chief Emeritus) and publisher Thomas Pizor, Current Psychiatry was designed precisely to fill this vital unmet need for busy clinical psychiatrists.1 Current Psychiatry provides practical, peer-reviewed, evidence-based reviews that are highly relevant to the realities of clinical psychiatric practice. Nationally recognized experts write articles about topics identified as “valued” by practitioners based on systematic surveys of clinicians in various community settings. A diverse editorial board of prominent academic teachers and researchers provides an ongoing stream of diverse articles and perspectives that distill the emerging science and practice of psychiatry into immediately useful applications.

From our first issue, Current Psychiatry has presented information that readers could use to care for their patients, in articles such as:

- Using antipsychotics in patients with dementia (Kasckow JW, et al; February 2004)

- How to reduce mania risk when prescribing stimulants (Dubovsky SL, et al; October 2005)

- Hypnotics and driving: FDA action, clinical trials show need for precautions (Freeman B, et al; April 2007)

- Fibromyalgia: Psychiatric drugs target CNS-linked symptoms (Stanford SB; March 2009)

- The re-emerging role of therapeutic neuromodulation (Janicak PG, et al; November 2010)

The impact has been spectacular. As Current Psychiatry celebrates its 10th anniversary this month, we can relish its remarkable growth and success. In independent readership surveys, Current Psychiatry has grown to become the most widely read non-tabloid psychiatry journal.2 As Editor-in-Chief, I derive great satisfaction from the rave reviews I receive from my colleagues around the country about how they regard Current Psychiatry as their number 1 resource for clinical updates. Stellar feedback such as this indicates that Current Psychiatry clearly meets clinicians’ educational needs.

However, we are not resting on our laurels. Current Psychiatry has continued to innovate and develop new approaches to ongoing self-education by growing its online presence. The offerings at CurrentPsychiatry.com have steadily increased to include the following features:

Online-exclusive content. CurrentPsychiatry.com provides additional resources such as tables, boxes, algorithms, and/or figures related to articles from the printed edition. Later this year, as our 10th anniversary initiative for you, our readers, Current Psychiatry will offer complete online-exclusive articles that will be listed on the table of contents but published only on CurrentPsychiatry.com.

Multimedia library. Every month, the author of 1 article is invited to participate in a brief (5- to 10-minute) audiocast in which he or she provides additional commentary on clinical topics related to the article. This library currently houses nearly 50 audiocasts. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages.asp?id=6412.

Continuing Medical Education (CME). This section of our Web site provides peer-reviewed education programs that offer visitors the opportunity to earn free CME credits on a range of clinical topics, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, depression, and more. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages_cme.asp.

Supplements. Recent topics covered in these peer-reviewed, non-CME programs include managing schizophrenia, transcranial magnetic stimulation for depression, and more. Available at CurrentPsychiatry.com/pages_supplement.asp.