User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

When clozapine is not an option

History: ‘leaving town’

Mr. S, age 58, escaped repeatedly from his group home over 4 weeks. During one episode, he removed mail from neighbors’ mailboxes and tried to direct midday traffic. He would disappear for a few hours, sometimes overnight, before returning or being brought back by police.

The patient—who has had schizophrenia with catatonic features for 30 years—offered assorted explanations for escaping, most of them based on delusional beliefs, such as “I’m leaving town to get married” or “I’m late for engineering class.”

Since his last escape 3 weeks ago, Mr. S has remained in the group home without incident but has not been reporting for his usual outpatient psychiatric care. One day, he finally presents to us at the group home sponsor’s urging.

On evaluation, Mr. S shows stereotyped speech, staring, posturing, speech-prompt mutism, and odd mannerisms such as saluting. He has not been bathing or sleeping and smiles inappropriately. He speaks only when spoken to and answers with short phrases punctuated with ”By the grace of the good Lord.”

The authors’ observations

DSM-IV-TR requires at least two features to diagnose catatonic schizophrenia:

- peculiar voluntary movements

- extreme negativism

- excessive motor activity

- echolalia or echopraxia

- motoric immobility.1

Catatonia is common among the chronic mentally ill,2 yet it often goes undiagnosed.3 As a form of psychosis, catatonia might lead to greater functional impairment if not treated.

Treatment: time to try clozapine?

Over 10 years, numerous antipsychotic regimens plus adjunctive valproic acid, 500 mg tid, or lorazepam, up to 2 mg tid, have not lessened Mr. S’ psychosis and impulsivity. We start clozapine, 400 mg/d, and order twice-monthly blood tests to check for clozapine-induced agranulocytosis.

After nearly 6 months, some catatonic features improve gradually based on clinical interview. Serum clozapine is 363 ng/mL.

poll here

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are favored over first-generation antipsychotics to treat schizophrenia with catatonic features (Table),4,5 but no drug in either class has worked for Mr. S.

ECT can alleviate catatonic schizophrenia,4,6 but this option often is not available because the clinician fears a negative outcome would prompt legal action, or the guardian or next of kin do not consent to the procedure.3 We considered referring Mr. S to an ECT provider, but he has no legal guardian to provide consent. The group home sponsor also objected to ECT because Mr. S would have been sent out of town for treatment.

Catatonia patients who are immobile, physically compromised, and refuse food and drink typically are considered ECT candidates. Mr. S eats and drinks regularly and is physically able.

Lorazepam can produce rapid response, but it can be addictive.2 Also, an adjunctive 2 mg/d dosage showed no effect.

Clozapine monotherapy has shown effectiveness in catatonic schizophrenia7 and might be an option after other antipsychotics have failed.

Table 1

Treatments for catatonia: risks and benefits

| Medication | Use | Rationale | Benefits | Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) | Often used for schizophrenia | Control positive symptoms | Well-established | Catatonia might be difficult to distinguish from NMS |

| Less expensive than other medications | ||||

| Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) | Beneficial in catatonia | Less likely than FGAs to worsen catatonia because of low D2 blockade | Some studies suggest greater efficacy than with FGAs | Metabolic syndrome, agranulocytosis with clozapine |

| Benzodiazepines | Lorazepam helpful in acute catatonia | Can be added to any antipsychotic | Safe, first-line treatment for catatonia | Respiratory compromise, incoordination, sedation, potential for abuse |

| Electroconvulsive therapy | ||||

| Electroconvulsive therapy | Beneficial in malignant catatonia | Effective in catatonia, NMS | Useful for treatment-refractory catatonia | Concerns with anesthesia, informed consent, availability |

| Rapid onset of action | ||||

| NMS: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | ||||

Complication: agranulocytosis, then nms

Six months after starting clozapine, Mr. S starts having diaphoresis and night sweats, suggesting neutropenia. Blood testing shows a white blood cell count (WBC) of 3.6/μL, down from 4.6/μL 2 weeks before (normal range, 4.6 to 11/μL).

One week later, Mr. S’ WBC is 1.6/μL with a 46% relative neutrophil value (normal range, 50% to 70%) and an absolute neutrophil count of 736 (normal range, 2,500 to 7,000).

We diagnose agranulocytosis and stop clozapine, but Mr. S’ WBC continues to fall over 2 weeks to 0.8/μL with a 16% relative and 128 absolute neutrophil count. After 1 more week, his WBC increases to 2.6/μL and returns to normal 1 week later—4 weeks after stopping clozapine

We then target Mr. S’ catatonia with intramuscular haloperidol, 100 mg/d for 4 weeks, and ziprasidone, 80 mg bid with food. He tolerates this combination but gradually develops tremor and rigidity. Six weeks later, we add levodopa/carbidopa, 25/250 mg bid for his movement problems.

Two weeks later, Mr. S is sweating profusely, disoriented, rigid, and febrile (104.6°F). We diagnose neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), stop both antipsychotics, and admit him for treatment. We start lorazepam, 1 mg tid for catatonia; bromocriptine, 250 mg bid for rigidity; and continue levodopa/carbidopa at the same dosage. We also add dantrolene, 25 mg tid for 5 days for fever and rigidity, and provide a cooling blanket for hyperthermia.

Mr. S’ fever, autonomic changes, and diaphoresis diminish within 3 days. Rigidity and mental status improve gradually over 2 weeks. We discharge him after 10 days.

poll here

The author’s observations

Catatonia is a recognized risk factor for NMS. White and Robins8 described 17 patients with a catatonic syndrome that developed into NMS within 5 to 96 hours of starting a neuroleptic. Sachdev developed an NMS rating scale that includes catatonic symptoms.9

Northoff,10 however, associates NMS with D2 receptor blockage in the basal ganglia and relates catatonia to a frontocortical gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) dysfunction. Based on this theory, haloperidol—which offers a higher D2 blockade than do SGAs such as ziprasidone—might have contributed to Mr. S’ NMS.

Some evidence suggests that lorazepam—which works on gamma-aminobutyric acid ionotropic type A (GABAA) receptors—helps treat catatonia in NMS and improves rigidity, hyperthermia, and autonomic signs.11

Treatment: which agents will work?

Three weeks after his discharge, we restart ziprasidone, 40 mg bid for Mr. S’ catatonic schizophrenia. He remains free of NMS symptoms but still has mannerisms (posturing, staring, immobility, stereotypic scratching on his face).

Over 1 year, Mr. S is hospitalized repeatedly because of persistent impulsivity and delusions. He has failed numerous antipsychotic regimens lasting 1 month or longer, including olanzapine, up to 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 300 mg tid; and risperidone, 2 mg tid. Adding a first-generation antipsychotic either does not help (as with perphenazine, 12 mg/d) or diminishes his memory (as with chlorpromazine, 250 mg/d). The anticholinergic benztropine, 2 mg bid, also is ineffective.

Combination quetiapine, 300 mg/d, and the antiviral amantadine, 100 mg tid, improve Mr. S’ stereotypy at first, but his delusions intensify within 1 week. His Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale scores range from 9 (indicating moderate catatonia) to 16 (persistent catatonic features).12

poll here

The authors’ observations

Catatonic schizophrenia’s pathophysiology and response to medication might differ compared with other schizophrenia forms.13 Dopamine D2 hypoactivity, glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) hyperactivity, or GABAA hypoactivity are believed to cause catatonia.3,6,7 GABA agonists, anticonvulsants, dopamine agonists, SGAs, and NMDA antagonists target these pathophysiologies, but patients with a catatonia subtype often respond to only one type of medication.

Lorazepam exerts an anticatatonic effect by binding to GABAA receptors and increasing GABA activity. Lorazepam can help some patients with schizophrenia but has not shown benefit when added to an antipsychotic for chronic catatonia.6,14

SGAs can provide marked improvement in patients with catatonic schizophrenia.5

Salokangas et al15 note that “atypicals” pass more dopamine to the D2 receptor when dopamine is low in the basal ganglia. This suggests that SGAs with low D2 binding—such as clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine—are more beneficial than other SGAs for catatonia. Serotonin binding or other mechanisms might add to these drugs’ anticatatonic effect.7

Anticonvulsants. Adjunctive anticonvulsant therapy might alleviate catatonia by increasing GABA activity or by causing a modest antiglutaminergic effect, as reported with carbamazepine or valproic acid.16 Anticholinergics also might help treat neuroleptic-induced catatonia.17

Amantadine—FDA-approved to treat Parkinson’s disease and extrapyramidal disease—can alleviate catatonia by blocking hyperglutamatergic excitotoxicity in neurons, thus blocking NMDA receptors.18 As with Mr. S, however, amantadine can worsen psychosis by increasing dopamine release.

Memantine—an NMDA receptor antagonist indicated for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease—also blocks hyperglutamatergic excitotoxicity in neurons. The medication has shown effectiveness for treating catatonic schizophrenia in case reports,19-21 but 3 patients have reported memantine-induced psychosis and seizures.21

Some might argue that Mr. S’ delusions are predominant and more compelling than his catatonia, but these did not hamper his ability to live in a group home. His catatonia-related negativism, impulsivity, and inability to cooperate are what led to frequent hospitalization.

Follow-up: treatment change

We stop amantadine, add memantine, 10 mg bid, and titrate quetiapine over 2 weeks to 900 mg/d. Mr. S’ catatonia improves but some delusions persist. We add olanzapine, 7.5 mg bid, and within 2 weeks Mr. S is less delusional and more cooperative.

We discharge Mr. S on the above medications, plus:

- lorazepam, 1 mg each morning and 2 mg nightly, which he has been taking for catatonia for about 1 year

- trazodone, 150 mg bid, which we added 6 months ago to help him sleep and reduce psychomotor excitement

- ranitidine, 150 mg bid, for gastroesophageal reflux disorder

- and levothyroxine, 0.5 mg/d, for comobrid hypothyroidism. His thyroid-stimulating hormone level is normal.

We see Mr. S monthly. He is still impulsive at times, occasionally collecting his neighbors’ newspapers and mail despite instructions from group home staff not to do so. Yet his sponsors say Mr. S is “like a new person.” He talks spontaneously, interacts, and is cooperative. He has not been hospitalized for more than 1 year.

The authors’ observations

Mr. S responded favorably to clozapine but cannot tolerate it. With a combination of two other SGAs, a patient might gain the benefits of clozapine without the need for frequent blood draws or the risk of agranulocytosis, other side effects, or interactions between clozapine and other drugs. Adding memantine was necessary to improve the catatonic features that prevented his return to the group home.

Related resources

- World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. www.wfsbp.com.

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Information Service. www.nmsis.org.

- Mann SC, Caroff SN, Keck PE Jr, Lazarus A. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and related conditions, 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press; 2003:1-44.

- Ungvari GS (ed). Catatonia-an anthology of classical contributions. Hong Kong: Scientific Communications International; 2006.

- Amantadine • Symmetrel

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Bromocriptine • Parlodel

- Carbamazepine • Equetro, others

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Dantrolene • Dantrium

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Levodopa/carbidopa • Sinemet

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Ranitidine • Zantac

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Valproic acid • Depakene

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Dr. Carroll is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers-Squibb Co., Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer.

Dr. Thomas receives grant support from Pfizer and is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer.

Dr. Tugrul is a consultant to and speaker for Bristol Myers-Squibb Co. and Eli Lilly and Co.

Dr. Jayanti reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Francisco José Appiani, MD, chairman, psychiatry department, Military Hospital of Campo de Mayo, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Vijay Jayanti, BS, medical student, The Ohio State University, Columbus, for their help with this article.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:204.

2. Ungvari GS, Leung SK, Ng FS, et al. Schizophrenia with prominent catatonic features (“catatonic schizophrenia”) I. Demographic and clinical correlates in the chronic phase. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005;29:27-38.

3. Dhossche D, Wing L, Ohta M, Neumarker K (eds). Catatonia in autism spectrum disorders. International review of neurobiology, vol. 72. San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2006.

4. Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J. WFSBP guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1. Acute treatment of schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry 2005;6:32-91.

5. Van Dalfsen F, Van Hecke J, Van Dalfsen A, et al. The use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of catatonia. Eur Psychiatry 2005;20:422-9.

6. Rosebush PI, Hildebrand AM, Furlong BG, Mazurek MF. Catatonic syndrome in a general psychiatric inpatient population: frequency, clinical presentation, and response to lorazepam. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:357-62.

7. Dursun SM, Hallak JE, Haddad P, et al. Clozapine monotherapy for catatonic schizophrenia: should clozapine be the treatment of choice, with catatonia rather than psychosis as the main therapeutic index? J Psychopharmacol 2005;19:432-3.

8. White DAC, Robbins AH. An analysis of 17 catatonic patients diagnosed with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. CNS Spectrums 2000;5:58-65.

9. Sachdev PS. A rating scale for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatry Res 2005;135:249-56.

10. Northoff G. Catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: psychopathology and pathophysiology. J Neural Transm 2002;109:1453-67.

11. Francis A, Chandragiri S, Rizvi S, et al. Is lorazepam a treatment for neuroleptic malignant syndrome? CNS Spectrums 2000;5:54-7.

12. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides, et al. Catatonia I: Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:129-36.

13. Carroll BT, Thomas C, Jayanti K, et al. Schizophrenia with catatonic features deserves further study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2005;6(4):267-8.

14. Ungvari GS, Chie HFK, Chow LY, et al. Lorazepam for chronic catatonia: A random, double blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:393-8.

15. Salokangas R, Honkonen T, Stengard E, et al. Negative symptoms and neuroleptics in catatonic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003;59:73-6.

16. Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: a clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

17. Franz M, Gallhofer B, Kanzow WT. Treatment of catatonia with intravenous biperidine. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:847-8.

18. Northoff G, Eckert J, Fritze J. Glutamatergic dysfunction in catatonia? Successful treatment of three acute akinetic catatonic patients with the NMDA antagonist amantadine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;62:404-6.

19. Thomas C, Carroll BT, Maley JT, et al. Memantine in catatonic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:656.

20. Carroll BT, Thomas C, Jayanti K. Amantadine and memantine in catatonic schizophrenia. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2006;18:133-4.

21. Carpenter SS, Hatchett AD, Fuller MA. Catatonic schizophrenia and the use of memantine. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:344-6.

History: ‘leaving town’

Mr. S, age 58, escaped repeatedly from his group home over 4 weeks. During one episode, he removed mail from neighbors’ mailboxes and tried to direct midday traffic. He would disappear for a few hours, sometimes overnight, before returning or being brought back by police.

The patient—who has had schizophrenia with catatonic features for 30 years—offered assorted explanations for escaping, most of them based on delusional beliefs, such as “I’m leaving town to get married” or “I’m late for engineering class.”

Since his last escape 3 weeks ago, Mr. S has remained in the group home without incident but has not been reporting for his usual outpatient psychiatric care. One day, he finally presents to us at the group home sponsor’s urging.

On evaluation, Mr. S shows stereotyped speech, staring, posturing, speech-prompt mutism, and odd mannerisms such as saluting. He has not been bathing or sleeping and smiles inappropriately. He speaks only when spoken to and answers with short phrases punctuated with ”By the grace of the good Lord.”

The authors’ observations

DSM-IV-TR requires at least two features to diagnose catatonic schizophrenia:

- peculiar voluntary movements

- extreme negativism

- excessive motor activity

- echolalia or echopraxia

- motoric immobility.1

Catatonia is common among the chronic mentally ill,2 yet it often goes undiagnosed.3 As a form of psychosis, catatonia might lead to greater functional impairment if not treated.

Treatment: time to try clozapine?

Over 10 years, numerous antipsychotic regimens plus adjunctive valproic acid, 500 mg tid, or lorazepam, up to 2 mg tid, have not lessened Mr. S’ psychosis and impulsivity. We start clozapine, 400 mg/d, and order twice-monthly blood tests to check for clozapine-induced agranulocytosis.

After nearly 6 months, some catatonic features improve gradually based on clinical interview. Serum clozapine is 363 ng/mL.

poll here

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are favored over first-generation antipsychotics to treat schizophrenia with catatonic features (Table),4,5 but no drug in either class has worked for Mr. S.

ECT can alleviate catatonic schizophrenia,4,6 but this option often is not available because the clinician fears a negative outcome would prompt legal action, or the guardian or next of kin do not consent to the procedure.3 We considered referring Mr. S to an ECT provider, but he has no legal guardian to provide consent. The group home sponsor also objected to ECT because Mr. S would have been sent out of town for treatment.

Catatonia patients who are immobile, physically compromised, and refuse food and drink typically are considered ECT candidates. Mr. S eats and drinks regularly and is physically able.

Lorazepam can produce rapid response, but it can be addictive.2 Also, an adjunctive 2 mg/d dosage showed no effect.

Clozapine monotherapy has shown effectiveness in catatonic schizophrenia7 and might be an option after other antipsychotics have failed.

Table 1

Treatments for catatonia: risks and benefits

| Medication | Use | Rationale | Benefits | Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) | Often used for schizophrenia | Control positive symptoms | Well-established | Catatonia might be difficult to distinguish from NMS |

| Less expensive than other medications | ||||

| Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) | Beneficial in catatonia | Less likely than FGAs to worsen catatonia because of low D2 blockade | Some studies suggest greater efficacy than with FGAs | Metabolic syndrome, agranulocytosis with clozapine |

| Benzodiazepines | Lorazepam helpful in acute catatonia | Can be added to any antipsychotic | Safe, first-line treatment for catatonia | Respiratory compromise, incoordination, sedation, potential for abuse |

| Electroconvulsive therapy | ||||

| Electroconvulsive therapy | Beneficial in malignant catatonia | Effective in catatonia, NMS | Useful for treatment-refractory catatonia | Concerns with anesthesia, informed consent, availability |

| Rapid onset of action | ||||

| NMS: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | ||||

Complication: agranulocytosis, then nms

Six months after starting clozapine, Mr. S starts having diaphoresis and night sweats, suggesting neutropenia. Blood testing shows a white blood cell count (WBC) of 3.6/μL, down from 4.6/μL 2 weeks before (normal range, 4.6 to 11/μL).

One week later, Mr. S’ WBC is 1.6/μL with a 46% relative neutrophil value (normal range, 50% to 70%) and an absolute neutrophil count of 736 (normal range, 2,500 to 7,000).

We diagnose agranulocytosis and stop clozapine, but Mr. S’ WBC continues to fall over 2 weeks to 0.8/μL with a 16% relative and 128 absolute neutrophil count. After 1 more week, his WBC increases to 2.6/μL and returns to normal 1 week later—4 weeks after stopping clozapine

We then target Mr. S’ catatonia with intramuscular haloperidol, 100 mg/d for 4 weeks, and ziprasidone, 80 mg bid with food. He tolerates this combination but gradually develops tremor and rigidity. Six weeks later, we add levodopa/carbidopa, 25/250 mg bid for his movement problems.

Two weeks later, Mr. S is sweating profusely, disoriented, rigid, and febrile (104.6°F). We diagnose neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), stop both antipsychotics, and admit him for treatment. We start lorazepam, 1 mg tid for catatonia; bromocriptine, 250 mg bid for rigidity; and continue levodopa/carbidopa at the same dosage. We also add dantrolene, 25 mg tid for 5 days for fever and rigidity, and provide a cooling blanket for hyperthermia.

Mr. S’ fever, autonomic changes, and diaphoresis diminish within 3 days. Rigidity and mental status improve gradually over 2 weeks. We discharge him after 10 days.

poll here

The author’s observations

Catatonia is a recognized risk factor for NMS. White and Robins8 described 17 patients with a catatonic syndrome that developed into NMS within 5 to 96 hours of starting a neuroleptic. Sachdev developed an NMS rating scale that includes catatonic symptoms.9

Northoff,10 however, associates NMS with D2 receptor blockage in the basal ganglia and relates catatonia to a frontocortical gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) dysfunction. Based on this theory, haloperidol—which offers a higher D2 blockade than do SGAs such as ziprasidone—might have contributed to Mr. S’ NMS.

Some evidence suggests that lorazepam—which works on gamma-aminobutyric acid ionotropic type A (GABAA) receptors—helps treat catatonia in NMS and improves rigidity, hyperthermia, and autonomic signs.11

Treatment: which agents will work?

Three weeks after his discharge, we restart ziprasidone, 40 mg bid for Mr. S’ catatonic schizophrenia. He remains free of NMS symptoms but still has mannerisms (posturing, staring, immobility, stereotypic scratching on his face).

Over 1 year, Mr. S is hospitalized repeatedly because of persistent impulsivity and delusions. He has failed numerous antipsychotic regimens lasting 1 month or longer, including olanzapine, up to 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 300 mg tid; and risperidone, 2 mg tid. Adding a first-generation antipsychotic either does not help (as with perphenazine, 12 mg/d) or diminishes his memory (as with chlorpromazine, 250 mg/d). The anticholinergic benztropine, 2 mg bid, also is ineffective.

Combination quetiapine, 300 mg/d, and the antiviral amantadine, 100 mg tid, improve Mr. S’ stereotypy at first, but his delusions intensify within 1 week. His Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale scores range from 9 (indicating moderate catatonia) to 16 (persistent catatonic features).12

poll here

The authors’ observations

Catatonic schizophrenia’s pathophysiology and response to medication might differ compared with other schizophrenia forms.13 Dopamine D2 hypoactivity, glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) hyperactivity, or GABAA hypoactivity are believed to cause catatonia.3,6,7 GABA agonists, anticonvulsants, dopamine agonists, SGAs, and NMDA antagonists target these pathophysiologies, but patients with a catatonia subtype often respond to only one type of medication.

Lorazepam exerts an anticatatonic effect by binding to GABAA receptors and increasing GABA activity. Lorazepam can help some patients with schizophrenia but has not shown benefit when added to an antipsychotic for chronic catatonia.6,14

SGAs can provide marked improvement in patients with catatonic schizophrenia.5

Salokangas et al15 note that “atypicals” pass more dopamine to the D2 receptor when dopamine is low in the basal ganglia. This suggests that SGAs with low D2 binding—such as clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine—are more beneficial than other SGAs for catatonia. Serotonin binding or other mechanisms might add to these drugs’ anticatatonic effect.7

Anticonvulsants. Adjunctive anticonvulsant therapy might alleviate catatonia by increasing GABA activity or by causing a modest antiglutaminergic effect, as reported with carbamazepine or valproic acid.16 Anticholinergics also might help treat neuroleptic-induced catatonia.17

Amantadine—FDA-approved to treat Parkinson’s disease and extrapyramidal disease—can alleviate catatonia by blocking hyperglutamatergic excitotoxicity in neurons, thus blocking NMDA receptors.18 As with Mr. S, however, amantadine can worsen psychosis by increasing dopamine release.

Memantine—an NMDA receptor antagonist indicated for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease—also blocks hyperglutamatergic excitotoxicity in neurons. The medication has shown effectiveness for treating catatonic schizophrenia in case reports,19-21 but 3 patients have reported memantine-induced psychosis and seizures.21

Some might argue that Mr. S’ delusions are predominant and more compelling than his catatonia, but these did not hamper his ability to live in a group home. His catatonia-related negativism, impulsivity, and inability to cooperate are what led to frequent hospitalization.

Follow-up: treatment change

We stop amantadine, add memantine, 10 mg bid, and titrate quetiapine over 2 weeks to 900 mg/d. Mr. S’ catatonia improves but some delusions persist. We add olanzapine, 7.5 mg bid, and within 2 weeks Mr. S is less delusional and more cooperative.

We discharge Mr. S on the above medications, plus:

- lorazepam, 1 mg each morning and 2 mg nightly, which he has been taking for catatonia for about 1 year

- trazodone, 150 mg bid, which we added 6 months ago to help him sleep and reduce psychomotor excitement

- ranitidine, 150 mg bid, for gastroesophageal reflux disorder

- and levothyroxine, 0.5 mg/d, for comobrid hypothyroidism. His thyroid-stimulating hormone level is normal.

We see Mr. S monthly. He is still impulsive at times, occasionally collecting his neighbors’ newspapers and mail despite instructions from group home staff not to do so. Yet his sponsors say Mr. S is “like a new person.” He talks spontaneously, interacts, and is cooperative. He has not been hospitalized for more than 1 year.

The authors’ observations

Mr. S responded favorably to clozapine but cannot tolerate it. With a combination of two other SGAs, a patient might gain the benefits of clozapine without the need for frequent blood draws or the risk of agranulocytosis, other side effects, or interactions between clozapine and other drugs. Adding memantine was necessary to improve the catatonic features that prevented his return to the group home.

Related resources

- World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. www.wfsbp.com.

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Information Service. www.nmsis.org.

- Mann SC, Caroff SN, Keck PE Jr, Lazarus A. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and related conditions, 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press; 2003:1-44.

- Ungvari GS (ed). Catatonia-an anthology of classical contributions. Hong Kong: Scientific Communications International; 2006.

- Amantadine • Symmetrel

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Bromocriptine • Parlodel

- Carbamazepine • Equetro, others

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Dantrolene • Dantrium

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Levodopa/carbidopa • Sinemet

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Ranitidine • Zantac

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Valproic acid • Depakene

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Dr. Carroll is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers-Squibb Co., Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer.

Dr. Thomas receives grant support from Pfizer and is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer.

Dr. Tugrul is a consultant to and speaker for Bristol Myers-Squibb Co. and Eli Lilly and Co.

Dr. Jayanti reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Francisco José Appiani, MD, chairman, psychiatry department, Military Hospital of Campo de Mayo, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Vijay Jayanti, BS, medical student, The Ohio State University, Columbus, for their help with this article.

History: ‘leaving town’

Mr. S, age 58, escaped repeatedly from his group home over 4 weeks. During one episode, he removed mail from neighbors’ mailboxes and tried to direct midday traffic. He would disappear for a few hours, sometimes overnight, before returning or being brought back by police.

The patient—who has had schizophrenia with catatonic features for 30 years—offered assorted explanations for escaping, most of them based on delusional beliefs, such as “I’m leaving town to get married” or “I’m late for engineering class.”

Since his last escape 3 weeks ago, Mr. S has remained in the group home without incident but has not been reporting for his usual outpatient psychiatric care. One day, he finally presents to us at the group home sponsor’s urging.

On evaluation, Mr. S shows stereotyped speech, staring, posturing, speech-prompt mutism, and odd mannerisms such as saluting. He has not been bathing or sleeping and smiles inappropriately. He speaks only when spoken to and answers with short phrases punctuated with ”By the grace of the good Lord.”

The authors’ observations

DSM-IV-TR requires at least two features to diagnose catatonic schizophrenia:

- peculiar voluntary movements

- extreme negativism

- excessive motor activity

- echolalia or echopraxia

- motoric immobility.1

Catatonia is common among the chronic mentally ill,2 yet it often goes undiagnosed.3 As a form of psychosis, catatonia might lead to greater functional impairment if not treated.

Treatment: time to try clozapine?

Over 10 years, numerous antipsychotic regimens plus adjunctive valproic acid, 500 mg tid, or lorazepam, up to 2 mg tid, have not lessened Mr. S’ psychosis and impulsivity. We start clozapine, 400 mg/d, and order twice-monthly blood tests to check for clozapine-induced agranulocytosis.

After nearly 6 months, some catatonic features improve gradually based on clinical interview. Serum clozapine is 363 ng/mL.

poll here

The authors’ observations

Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) are favored over first-generation antipsychotics to treat schizophrenia with catatonic features (Table),4,5 but no drug in either class has worked for Mr. S.

ECT can alleviate catatonic schizophrenia,4,6 but this option often is not available because the clinician fears a negative outcome would prompt legal action, or the guardian or next of kin do not consent to the procedure.3 We considered referring Mr. S to an ECT provider, but he has no legal guardian to provide consent. The group home sponsor also objected to ECT because Mr. S would have been sent out of town for treatment.

Catatonia patients who are immobile, physically compromised, and refuse food and drink typically are considered ECT candidates. Mr. S eats and drinks regularly and is physically able.

Lorazepam can produce rapid response, but it can be addictive.2 Also, an adjunctive 2 mg/d dosage showed no effect.

Clozapine monotherapy has shown effectiveness in catatonic schizophrenia7 and might be an option after other antipsychotics have failed.

Table 1

Treatments for catatonia: risks and benefits

| Medication | Use | Rationale | Benefits | Risks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) | Often used for schizophrenia | Control positive symptoms | Well-established | Catatonia might be difficult to distinguish from NMS |

| Less expensive than other medications | ||||

| Second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) | Beneficial in catatonia | Less likely than FGAs to worsen catatonia because of low D2 blockade | Some studies suggest greater efficacy than with FGAs | Metabolic syndrome, agranulocytosis with clozapine |

| Benzodiazepines | Lorazepam helpful in acute catatonia | Can be added to any antipsychotic | Safe, first-line treatment for catatonia | Respiratory compromise, incoordination, sedation, potential for abuse |

| Electroconvulsive therapy | ||||

| Electroconvulsive therapy | Beneficial in malignant catatonia | Effective in catatonia, NMS | Useful for treatment-refractory catatonia | Concerns with anesthesia, informed consent, availability |

| Rapid onset of action | ||||

| NMS: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome | ||||

Complication: agranulocytosis, then nms

Six months after starting clozapine, Mr. S starts having diaphoresis and night sweats, suggesting neutropenia. Blood testing shows a white blood cell count (WBC) of 3.6/μL, down from 4.6/μL 2 weeks before (normal range, 4.6 to 11/μL).

One week later, Mr. S’ WBC is 1.6/μL with a 46% relative neutrophil value (normal range, 50% to 70%) and an absolute neutrophil count of 736 (normal range, 2,500 to 7,000).

We diagnose agranulocytosis and stop clozapine, but Mr. S’ WBC continues to fall over 2 weeks to 0.8/μL with a 16% relative and 128 absolute neutrophil count. After 1 more week, his WBC increases to 2.6/μL and returns to normal 1 week later—4 weeks after stopping clozapine

We then target Mr. S’ catatonia with intramuscular haloperidol, 100 mg/d for 4 weeks, and ziprasidone, 80 mg bid with food. He tolerates this combination but gradually develops tremor and rigidity. Six weeks later, we add levodopa/carbidopa, 25/250 mg bid for his movement problems.

Two weeks later, Mr. S is sweating profusely, disoriented, rigid, and febrile (104.6°F). We diagnose neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), stop both antipsychotics, and admit him for treatment. We start lorazepam, 1 mg tid for catatonia; bromocriptine, 250 mg bid for rigidity; and continue levodopa/carbidopa at the same dosage. We also add dantrolene, 25 mg tid for 5 days for fever and rigidity, and provide a cooling blanket for hyperthermia.

Mr. S’ fever, autonomic changes, and diaphoresis diminish within 3 days. Rigidity and mental status improve gradually over 2 weeks. We discharge him after 10 days.

poll here

The author’s observations

Catatonia is a recognized risk factor for NMS. White and Robins8 described 17 patients with a catatonic syndrome that developed into NMS within 5 to 96 hours of starting a neuroleptic. Sachdev developed an NMS rating scale that includes catatonic symptoms.9

Northoff,10 however, associates NMS with D2 receptor blockage in the basal ganglia and relates catatonia to a frontocortical gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) dysfunction. Based on this theory, haloperidol—which offers a higher D2 blockade than do SGAs such as ziprasidone—might have contributed to Mr. S’ NMS.

Some evidence suggests that lorazepam—which works on gamma-aminobutyric acid ionotropic type A (GABAA) receptors—helps treat catatonia in NMS and improves rigidity, hyperthermia, and autonomic signs.11

Treatment: which agents will work?

Three weeks after his discharge, we restart ziprasidone, 40 mg bid for Mr. S’ catatonic schizophrenia. He remains free of NMS symptoms but still has mannerisms (posturing, staring, immobility, stereotypic scratching on his face).

Over 1 year, Mr. S is hospitalized repeatedly because of persistent impulsivity and delusions. He has failed numerous antipsychotic regimens lasting 1 month or longer, including olanzapine, up to 30 mg/d; quetiapine, 300 mg tid; and risperidone, 2 mg tid. Adding a first-generation antipsychotic either does not help (as with perphenazine, 12 mg/d) or diminishes his memory (as with chlorpromazine, 250 mg/d). The anticholinergic benztropine, 2 mg bid, also is ineffective.

Combination quetiapine, 300 mg/d, and the antiviral amantadine, 100 mg tid, improve Mr. S’ stereotypy at first, but his delusions intensify within 1 week. His Bush-Francis Catatonia Rating Scale scores range from 9 (indicating moderate catatonia) to 16 (persistent catatonic features).12

poll here

The authors’ observations

Catatonic schizophrenia’s pathophysiology and response to medication might differ compared with other schizophrenia forms.13 Dopamine D2 hypoactivity, glutamate N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) hyperactivity, or GABAA hypoactivity are believed to cause catatonia.3,6,7 GABA agonists, anticonvulsants, dopamine agonists, SGAs, and NMDA antagonists target these pathophysiologies, but patients with a catatonia subtype often respond to only one type of medication.

Lorazepam exerts an anticatatonic effect by binding to GABAA receptors and increasing GABA activity. Lorazepam can help some patients with schizophrenia but has not shown benefit when added to an antipsychotic for chronic catatonia.6,14

SGAs can provide marked improvement in patients with catatonic schizophrenia.5

Salokangas et al15 note that “atypicals” pass more dopamine to the D2 receptor when dopamine is low in the basal ganglia. This suggests that SGAs with low D2 binding—such as clozapine, olanzapine, and quetiapine—are more beneficial than other SGAs for catatonia. Serotonin binding or other mechanisms might add to these drugs’ anticatatonic effect.7

Anticonvulsants. Adjunctive anticonvulsant therapy might alleviate catatonia by increasing GABA activity or by causing a modest antiglutaminergic effect, as reported with carbamazepine or valproic acid.16 Anticholinergics also might help treat neuroleptic-induced catatonia.17

Amantadine—FDA-approved to treat Parkinson’s disease and extrapyramidal disease—can alleviate catatonia by blocking hyperglutamatergic excitotoxicity in neurons, thus blocking NMDA receptors.18 As with Mr. S, however, amantadine can worsen psychosis by increasing dopamine release.

Memantine—an NMDA receptor antagonist indicated for moderate to severe Alzheimer’s disease—also blocks hyperglutamatergic excitotoxicity in neurons. The medication has shown effectiveness for treating catatonic schizophrenia in case reports,19-21 but 3 patients have reported memantine-induced psychosis and seizures.21

Some might argue that Mr. S’ delusions are predominant and more compelling than his catatonia, but these did not hamper his ability to live in a group home. His catatonia-related negativism, impulsivity, and inability to cooperate are what led to frequent hospitalization.

Follow-up: treatment change

We stop amantadine, add memantine, 10 mg bid, and titrate quetiapine over 2 weeks to 900 mg/d. Mr. S’ catatonia improves but some delusions persist. We add olanzapine, 7.5 mg bid, and within 2 weeks Mr. S is less delusional and more cooperative.

We discharge Mr. S on the above medications, plus:

- lorazepam, 1 mg each morning and 2 mg nightly, which he has been taking for catatonia for about 1 year

- trazodone, 150 mg bid, which we added 6 months ago to help him sleep and reduce psychomotor excitement

- ranitidine, 150 mg bid, for gastroesophageal reflux disorder

- and levothyroxine, 0.5 mg/d, for comobrid hypothyroidism. His thyroid-stimulating hormone level is normal.

We see Mr. S monthly. He is still impulsive at times, occasionally collecting his neighbors’ newspapers and mail despite instructions from group home staff not to do so. Yet his sponsors say Mr. S is “like a new person.” He talks spontaneously, interacts, and is cooperative. He has not been hospitalized for more than 1 year.

The authors’ observations

Mr. S responded favorably to clozapine but cannot tolerate it. With a combination of two other SGAs, a patient might gain the benefits of clozapine without the need for frequent blood draws or the risk of agranulocytosis, other side effects, or interactions between clozapine and other drugs. Adding memantine was necessary to improve the catatonic features that prevented his return to the group home.

Related resources

- World Federation of Societies of Biological Psychiatry. www.wfsbp.com.

- Neuroleptic Malignant Syndrome Information Service. www.nmsis.org.

- Mann SC, Caroff SN, Keck PE Jr, Lazarus A. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and related conditions, 2nd ed. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Press; 2003:1-44.

- Ungvari GS (ed). Catatonia-an anthology of classical contributions. Hong Kong: Scientific Communications International; 2006.

- Amantadine • Symmetrel

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Bromocriptine • Parlodel

- Carbamazepine • Equetro, others

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Dantrolene • Dantrium

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Levodopa/carbidopa • Sinemet

- Levothyroxine • Synthroid

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Memantine • Namenda

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Perphenazine • Trilafon

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Ranitidine • Zantac

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Valproic acid • Depakene

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Dr. Carroll is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, Bristol Myers-Squibb Co., Forest Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceutica, and Pfizer.

Dr. Thomas receives grant support from Pfizer and is a speaker for Abbott Laboratories, AstraZeneca Pharmaceuticals, and Pfizer.

Dr. Tugrul is a consultant to and speaker for Bristol Myers-Squibb Co. and Eli Lilly and Co.

Dr. Jayanti reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Francisco José Appiani, MD, chairman, psychiatry department, Military Hospital of Campo de Mayo, Buenos Aires, Argentina, and Vijay Jayanti, BS, medical student, The Ohio State University, Columbus, for their help with this article.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:204.

2. Ungvari GS, Leung SK, Ng FS, et al. Schizophrenia with prominent catatonic features (“catatonic schizophrenia”) I. Demographic and clinical correlates in the chronic phase. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005;29:27-38.

3. Dhossche D, Wing L, Ohta M, Neumarker K (eds). Catatonia in autism spectrum disorders. International review of neurobiology, vol. 72. San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2006.

4. Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J. WFSBP guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1. Acute treatment of schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry 2005;6:32-91.

5. Van Dalfsen F, Van Hecke J, Van Dalfsen A, et al. The use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of catatonia. Eur Psychiatry 2005;20:422-9.

6. Rosebush PI, Hildebrand AM, Furlong BG, Mazurek MF. Catatonic syndrome in a general psychiatric inpatient population: frequency, clinical presentation, and response to lorazepam. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:357-62.

7. Dursun SM, Hallak JE, Haddad P, et al. Clozapine monotherapy for catatonic schizophrenia: should clozapine be the treatment of choice, with catatonia rather than psychosis as the main therapeutic index? J Psychopharmacol 2005;19:432-3.

8. White DAC, Robbins AH. An analysis of 17 catatonic patients diagnosed with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. CNS Spectrums 2000;5:58-65.

9. Sachdev PS. A rating scale for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatry Res 2005;135:249-56.

10. Northoff G. Catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: psychopathology and pathophysiology. J Neural Transm 2002;109:1453-67.

11. Francis A, Chandragiri S, Rizvi S, et al. Is lorazepam a treatment for neuroleptic malignant syndrome? CNS Spectrums 2000;5:54-7.

12. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides, et al. Catatonia I: Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:129-36.

13. Carroll BT, Thomas C, Jayanti K, et al. Schizophrenia with catatonic features deserves further study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2005;6(4):267-8.

14. Ungvari GS, Chie HFK, Chow LY, et al. Lorazepam for chronic catatonia: A random, double blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:393-8.

15. Salokangas R, Honkonen T, Stengard E, et al. Negative symptoms and neuroleptics in catatonic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003;59:73-6.

16. Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: a clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

17. Franz M, Gallhofer B, Kanzow WT. Treatment of catatonia with intravenous biperidine. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:847-8.

18. Northoff G, Eckert J, Fritze J. Glutamatergic dysfunction in catatonia? Successful treatment of three acute akinetic catatonic patients with the NMDA antagonist amantadine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;62:404-6.

19. Thomas C, Carroll BT, Maley JT, et al. Memantine in catatonic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:656.

20. Carroll BT, Thomas C, Jayanti K. Amantadine and memantine in catatonic schizophrenia. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2006;18:133-4.

21. Carpenter SS, Hatchett AD, Fuller MA. Catatonic schizophrenia and the use of memantine. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:344-6.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000:204.

2. Ungvari GS, Leung SK, Ng FS, et al. Schizophrenia with prominent catatonic features (“catatonic schizophrenia”) I. Demographic and clinical correlates in the chronic phase. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2005;29:27-38.

3. Dhossche D, Wing L, Ohta M, Neumarker K (eds). Catatonia in autism spectrum disorders. International review of neurobiology, vol. 72. San Diego: Elsevier/Academic Press; 2006.

4. Falkai P, Wobrock T, Lieberman J. WFSBP guidelines for biological treatment of schizophrenia, part 1. Acute treatment of schizophrenia. World J Biol Psychiatry 2005;6:32-91.

5. Van Dalfsen F, Van Hecke J, Van Dalfsen A, et al. The use of atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of catatonia. Eur Psychiatry 2005;20:422-9.

6. Rosebush PI, Hildebrand AM, Furlong BG, Mazurek MF. Catatonic syndrome in a general psychiatric inpatient population: frequency, clinical presentation, and response to lorazepam. J Clin Psychiatry 1990;51:357-62.

7. Dursun SM, Hallak JE, Haddad P, et al. Clozapine monotherapy for catatonic schizophrenia: should clozapine be the treatment of choice, with catatonia rather than psychosis as the main therapeutic index? J Psychopharmacol 2005;19:432-3.

8. White DAC, Robbins AH. An analysis of 17 catatonic patients diagnosed with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. CNS Spectrums 2000;5:58-65.

9. Sachdev PS. A rating scale for neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatry Res 2005;135:249-56.

10. Northoff G. Catatonia and neuroleptic malignant syndrome: psychopathology and pathophysiology. J Neural Transm 2002;109:1453-67.

11. Francis A, Chandragiri S, Rizvi S, et al. Is lorazepam a treatment for neuroleptic malignant syndrome? CNS Spectrums 2000;5:54-7.

12. Bush G, Fink M, Petrides, et al. Catatonia I: Rating scale and standardized examination. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1996;93:129-36.

13. Carroll BT, Thomas C, Jayanti K, et al. Schizophrenia with catatonic features deserves further study. World J Biol Psychiatry 2005;6(4):267-8.

14. Ungvari GS, Chie HFK, Chow LY, et al. Lorazepam for chronic catatonia: A random, double blind, placebo-controlled cross-over study. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:393-8.

15. Salokangas R, Honkonen T, Stengard E, et al. Negative symptoms and neuroleptics in catatonic schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2003;59:73-6.

16. Fink M, Taylor MA. Catatonia: a clinician’s guide to diagnosis and treatment. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2003.

17. Franz M, Gallhofer B, Kanzow WT. Treatment of catatonia with intravenous biperidine. Br J Psychiatry 1994;164:847-8.

18. Northoff G, Eckert J, Fritze J. Glutamatergic dysfunction in catatonia? Successful treatment of three acute akinetic catatonic patients with the NMDA antagonist amantadine. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1997;62:404-6.

19. Thomas C, Carroll BT, Maley JT, et al. Memantine in catatonic schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:656.

20. Carroll BT, Thomas C, Jayanti K. Amantadine and memantine in catatonic schizophrenia. Ann Clin Psychiatry 2006;18:133-4.

21. Carpenter SS, Hatchett AD, Fuller MA. Catatonic schizophrenia and the use of memantine. Ann Pharmacother 2006;40:344-6.

Making an IMPACT on late-life depression

Few depressed older adults seek help from psychiatrists. Those who receive mental health treatment most likely do so in primary care settings. Yet primary care physicians (PCPs) often are ill-equipped to effectively treat depression while managing older patients’ numerous acute and chronic medical conditions.

If depressed older patients won’t go to a psychiatrist, why not bring the psychiatrist to the patients? This article describes a clinically tested approach called project IMPACT that links psychiatrists to primary care teams and dramatically improves depression treatment in older adults.

Untreated geriatric depression

Preference for primary care. Major depression is rare in community-living older adults (1% to 3% prevalence), but:

- 5% to 10% of older primary care patients meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depression1

- approximately one-half of depressed older adults report a primary care visit when a mental health problem was addressed during the past year.2

- Prefer treatment in primary care instead of mental health settings

- Only 50% follow through on mental health referrals

- Only 20% improve when treated in primary care without a team approach

- Chronic medical illnesses often complicate diagnosis and treatment

- Often complain of somatic symptoms of depression

- May believe depression is a ‘normal’ part of aging

- May receive subtherapeutic antidepressant dosages because of physician concerns about side effects

Source: References 2-4

Depression is rarely the only illness an older adult is experiencing:

- 10% to 25% of adults with chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes or heart disease have major depression.

- Medical illness is associated with increased rates of depression, and depression is associated with poorer physical health.6

Depression diminishes self-care, which is key to managing chronic medical illnesses in late life. Depressed patients have higher rates of obesity and smoking. They are less likely to exercise, eat well, or adhere to complex treatment regimens with oral hypoglycemics, antihypertensives, and lipid-lowering drugs.7

Depression also substantially increases total health care costs among older adults.8

Only 8% of depressed older adults visit a mental health specialist in a given year, compared with 25% of depressed younger adults.2 Even when PCPs refer older patients to a mental health specialist, only 50% follow through (Box 1).3,4

Barriers to effective care. Depression diagnosis and treatment by PCPs has improved, but a recent survey suggests that with usual treatment:

- only 1 in 5 depressed older adults treated in a primary care practice experiences substantial improvement over 12 months

- only 1 in 10 becomes symptom-free.5

Many depressed older adults do not realize they have depression and visit their PCPs complaining of physical symptoms (Box 2).6-8 Their limited knowledge about depression or fear of being labeled “mentally ill” deters them from disclosing a depressed mood. They and their PCPs may think depression is inevitable with aging.

PCPs also may lack training to differentiate mood disorders, transitory reactions to life-events, or depression caused by medical illness. Their busy schedules limit time to address and prioritize patient concerns about acute and chronic medical problems (Box 3). Thus depression “falls through the cracks.”

Prescribing concerns. PCPs who feel uncomfortable prescribing antidepressants to older patients may be concerned about side effects and maintain dosages at low starting levels instead of titrating up to a therapeutic range.

Collaborative care

One way to overcome these barriers is to integrate mental health providers into primary care to support and augment PCP-prescribed depression treatment. Collaborative care can become an effective, efficient way to provide high-quality depression care to older patients who might otherwise go untreated.9

- Concerns about discussing a socially stigmatized condition with older adults

- Buying into the fallacy that depression is ‘normal’ in late life

- Missing the diagnosis because of medical comorbidity and older adults’ focus on physical versus emotional symptoms

- Unfamiliarity with how to prescribe antidepressants, particularly for patients with complex medical comorbidity

- Time constraints may discourage opening ‘Pandora’s box’ of depression

Project IMPACT. One such model—project IMPACT (Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment for Late-life Depression)—was developed with support from the John A. Hartford Foundation and California Healthcare Foundation. At its heart is a depression care manager or depression clinical specialist—typically a nurse, social worker, or psychologist—who works in a primary care practice. Other team members include the patient’s PCP, the patient, and a consulting psychiatrist.

The care manager works closely with the PCP by:

- educating patients about depression

- coaching patients in pleasant events scheduling/behavioral activation

- supporting the PCP’s antidepressant management

- offering patients a brief course of evidence-based counseling, such as Problem Solving Treatment in Primary Care10

- measuring patients’ depressive symptoms at treatment onset and regularly thereafter with a tool such as the 9-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).11

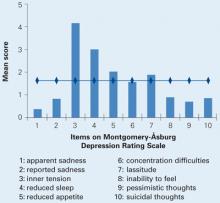

Consulting psychiatrist’s role. If a patient is not sufficiently improved after 8 to 10 weeks, the care manager works with the PCP and psychiatrist to change treatment according to an evidence-based algorithm (Figure).12 In large health care systems, the psychiatrist meets weekly with the care manager to review treatment plans for approximately 100 depressed older adults, with particular attention to those who are not improving. Psychiatrists may see patients in person or facilitate other specialty mental health treatment, as indicated.

Patients are encouraged to choose an antidepressant prescribed by their PCP, psychotherapy provided by the care manager in the primary care setting, or both. The patient and PCP make treatment decisions with support from the care manager and psychiatrist.

After depressive symptoms remit, the care manager completes a relapse prevention plan with the patient. This includes:

- steps the patient can take to prevent a relapse

- identifying relapse warning signs

- an action plan if depressive symptoms recur.

Training for clinicians in the IMPACT model is available at workshops and on the Internet (see Related resources). Successful implementation requires addressing operational and financing issues, and potential funding sources for primary care-based management have been described.13

Figure 3-step IMPACT intervention for a typical older patient with depression

PST-PC: Problem Solving Treatment in Primary Care

ECT: Electroconvulsive therapy

Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Unützer J, Katon WJ, Williams JW, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multi-center randomized trial. Medical Care 2001;39:785.

How impact was tested

The IMPACT team care model has been tested in a randomized trial with 1,801 depressed older adults from 18 primary care clinics in 8 U.S. health care organizations. These included feefor-service plans, health maintenance organizations, and Veterans Affairs clinics with more than 450 PCPs in rural and urban settings.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive IMPACT care for 12 months or care as usual (in usual care, the patient and provider were informed that the patient met diagnostic criteria for major depression or dysthymia). Patients assigned to usual care could engage in any depression treatment the provider normally used, including referral to specialty mental health services.14

Result: Better outcomes. IMPACT was more effective than usual care for late-life depression in all 8 organizations over 2 years.15,16 Overall, IMPACT doubled the effect of usual care. IMPACT patients:

- experienced >100 additional depression-free days17

- showed substantial improvements in physical and social functioning15,17 and quality of life,15 even 12 months after IMPACT resources were withdrawn18

- experienced less pain and pain-related functional impairment19

- had significantly less suicidal ideation.20

IMPACT care also was more cost-effective than usual care for depression in older adults with and without comorbid medical illnesses.17

From research to practice

Based on the robust study outcomes, researchers received a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation to provide materials, training, and technical assistance to organizations interested in adopting IMPACT. More than 20 health care organizations have used IMPACT, and several have completed program evaluations showing outcomes matching the original IMPACT trial’s.

Kaiser Permanente of Southern California serves 3 million members. Before adopting collaborative care for depression, Kaiser conducted a pilot study of the project IMPACT model modified to fit its health care system. Adaptations included:

- expanding the program to serve depressed adults of all ages

- adding medical assistants to the care team to help with patient follow-up

- adding a “depression class” to offer group-based patient education

- providing psychiatric consultation to the care manager and primary care providers by telephone.

Kaiser investigators compared the outcomes of 300 patients who experienced the adapted program with outcomes in 140 usual-care patients and 140 intervention patients in the original IMPACT study. The effects on depression symptoms were equal to those achieved in the original IMPACT study, with 68% of depressed older adults showing substantial improvement (at least a 50% reduction in depression symptoms) at 6 months.21

- Project IMPACT. www.impact-uw.org.

- American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry. www.aagpgpa.org.

- Positive Aging Resource Center. http://positiveaging.org.

Acknowledgment

This paper is based on a presentation by Dr. Unützer for the Distinguished Scientist Award at the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry annual meeting in Puerto Rico, March 10, 2006.

1. Lyness JM, Caine ED, King DA, et al. Psychiatric disorders in older primary care patients. J Gen Intern Med 1999;14(4):249-54.

2. Klap R, Unroe KT, Unützer J. Caring for mental illness in the United States: a focus on older adults. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry 2003;11(5):517-24.

3. Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Dittus RS, et al. Improving treatment of late life depression in primary care: a randomized clinical trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 1994;42(8):839-46.

4. Bartels SJ, Coakley EH, Zubritsky C, et al. Improving access to geriatric mental health services: a randomized trial comparing treatment engagement with integrated versus enhanced referral care for depression, anxiety, and at-risk alcohol use. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161(8):1455-62.

5. Crystal S, Sambamoorthi U, Walkup JT, et al. Diagnosis and treatment of depression in the elderly medicare population: predictors, disparities, and trends. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51(12):1718-28.

6. Katon WJ. Clinical and health services relationships between major depression, depressive symptoms, and general medical illness. Biol Psychiatry 2003;54(3):216-26.

7. Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Relationship of depression and diabetes self-care, medication adherence, and preventive care. Diabetes Care 2004;27(9):2154-60.

8. Unützer J, Patrick DL, Simon G, et al. Depressive symptoms and the cost of health services in HMO patients aged 65 years and older. A 4-year prospective study. JAMA 1997;277(20):1618-23.

9. Oxman TE, Dietrich AJ, Schulberg HC. Evidence-based models of integrated management of depression in primary care. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2005;28(4):1061-77.

10. Hegel MT, Dietrich AJ, Seville JL, et al. Training residents in problem-solving treatment of depression: a pilot feasibility and impact study. Fam Med 2004;36(3):204-8.

11. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med 2001;16(9):606-13.

12. Unützer J, Katon WJ, Williams JW, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multi-center randomized trial. Medical Care 2001;39:785.-

13. Bachman J, Pincus HA, Houtsinger JK, Unützer J. Funding mechanisms for depression care management: opportunities and challenges. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28(4):278-88.

14. Unützer J, Katon W, Williams JW, Jr, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multicenter randomized trial. Med Care 2001;39(8):785-99.

15. Unützer J, Katon W, Callahan CM, et al. Collaborative care management of late-life depression in the primary care setting: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2002;288(22):2836-45.

16. Unützer J, Powers D, Katon W, et al. From establishing an evidence-based practice to implementation in real-world settings: IMPACT as a case study. Psychiatr Clin North Am 2005;28(4):1079-92.

17. Katon WJ, Schoenbaum M, Fan MY, et al. Cost-effectiveness of improving primary care treatment of late-life depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62(12):1313-20.

18. Hunkeler EM, Katon W, Tang L, et al. Long term outcomes from the IMPACT randomised trial for depressed elderly patients in primary care. BMJ 2006;332(7536):259-63.

19. Lin EH, Katon W, Von Korff M, et al. Effect of improving depression care on pain and functional outcomes among older adults with arthritis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2003;290(18):2428-9.

20. Bruce ML, Ten Have TR, Reynolds CF, 3rd, et al. Reducing suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms in depressed older primary care patients: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA 2004;291(9):1081-91.

21. Grypma L, Haverkamp R, Little S, et al. Taking an evidence-based model of depression care from research to practice: making lemonade out of depression. Gen Hosp Psychiatry 2006;28(2):101-7.

Few depressed older adults seek help from psychiatrists. Those who receive mental health treatment most likely do so in primary care settings. Yet primary care physicians (PCPs) often are ill-equipped to effectively treat depression while managing older patients’ numerous acute and chronic medical conditions.

If depressed older patients won’t go to a psychiatrist, why not bring the psychiatrist to the patients? This article describes a clinically tested approach called project IMPACT that links psychiatrists to primary care teams and dramatically improves depression treatment in older adults.

Untreated geriatric depression

Preference for primary care. Major depression is rare in community-living older adults (1% to 3% prevalence), but:

- 5% to 10% of older primary care patients meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depression1

- approximately one-half of depressed older adults report a primary care visit when a mental health problem was addressed during the past year.2

- Prefer treatment in primary care instead of mental health settings

- Only 50% follow through on mental health referrals

- Only 20% improve when treated in primary care without a team approach

- Chronic medical illnesses often complicate diagnosis and treatment

- Often complain of somatic symptoms of depression

- May believe depression is a ‘normal’ part of aging

- May receive subtherapeutic antidepressant dosages because of physician concerns about side effects

Source: References 2-4

Depression is rarely the only illness an older adult is experiencing:

- 10% to 25% of adults with chronic medical illnesses such as diabetes or heart disease have major depression.

- Medical illness is associated with increased rates of depression, and depression is associated with poorer physical health.6

Depression diminishes self-care, which is key to managing chronic medical illnesses in late life. Depressed patients have higher rates of obesity and smoking. They are less likely to exercise, eat well, or adhere to complex treatment regimens with oral hypoglycemics, antihypertensives, and lipid-lowering drugs.7

Depression also substantially increases total health care costs among older adults.8

Only 8% of depressed older adults visit a mental health specialist in a given year, compared with 25% of depressed younger adults.2 Even when PCPs refer older patients to a mental health specialist, only 50% follow through (Box 1).3,4

Barriers to effective care. Depression diagnosis and treatment by PCPs has improved, but a recent survey suggests that with usual treatment:

- only 1 in 5 depressed older adults treated in a primary care practice experiences substantial improvement over 12 months

- only 1 in 10 becomes symptom-free.5

Many depressed older adults do not realize they have depression and visit their PCPs complaining of physical symptoms (Box 2).6-8 Their limited knowledge about depression or fear of being labeled “mentally ill” deters them from disclosing a depressed mood. They and their PCPs may think depression is inevitable with aging.

PCPs also may lack training to differentiate mood disorders, transitory reactions to life-events, or depression caused by medical illness. Their busy schedules limit time to address and prioritize patient concerns about acute and chronic medical problems (Box 3). Thus depression “falls through the cracks.”

Prescribing concerns. PCPs who feel uncomfortable prescribing antidepressants to older patients may be concerned about side effects and maintain dosages at low starting levels instead of titrating up to a therapeutic range.

Collaborative care

One way to overcome these barriers is to integrate mental health providers into primary care to support and augment PCP-prescribed depression treatment. Collaborative care can become an effective, efficient way to provide high-quality depression care to older patients who might otherwise go untreated.9

- Concerns about discussing a socially stigmatized condition with older adults

- Buying into the fallacy that depression is ‘normal’ in late life

- Missing the diagnosis because of medical comorbidity and older adults’ focus on physical versus emotional symptoms

- Unfamiliarity with how to prescribe antidepressants, particularly for patients with complex medical comorbidity

- Time constraints may discourage opening ‘Pandora’s box’ of depression

Project IMPACT. One such model—project IMPACT (Improving Mood: Promoting Access to Collaborative Treatment for Late-life Depression)—was developed with support from the John A. Hartford Foundation and California Healthcare Foundation. At its heart is a depression care manager or depression clinical specialist—typically a nurse, social worker, or psychologist—who works in a primary care practice. Other team members include the patient’s PCP, the patient, and a consulting psychiatrist.

The care manager works closely with the PCP by:

- educating patients about depression

- coaching patients in pleasant events scheduling/behavioral activation

- supporting the PCP’s antidepressant management

- offering patients a brief course of evidence-based counseling, such as Problem Solving Treatment in Primary Care10

- measuring patients’ depressive symptoms at treatment onset and regularly thereafter with a tool such as the 9-item depression scale of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9).11

Consulting psychiatrist’s role. If a patient is not sufficiently improved after 8 to 10 weeks, the care manager works with the PCP and psychiatrist to change treatment according to an evidence-based algorithm (Figure).12 In large health care systems, the psychiatrist meets weekly with the care manager to review treatment plans for approximately 100 depressed older adults, with particular attention to those who are not improving. Psychiatrists may see patients in person or facilitate other specialty mental health treatment, as indicated.

Patients are encouraged to choose an antidepressant prescribed by their PCP, psychotherapy provided by the care manager in the primary care setting, or both. The patient and PCP make treatment decisions with support from the care manager and psychiatrist.

After depressive symptoms remit, the care manager completes a relapse prevention plan with the patient. This includes:

- steps the patient can take to prevent a relapse

- identifying relapse warning signs

- an action plan if depressive symptoms recur.

Training for clinicians in the IMPACT model is available at workshops and on the Internet (see Related resources). Successful implementation requires addressing operational and financing issues, and potential funding sources for primary care-based management have been described.13

Figure 3-step IMPACT intervention for a typical older patient with depression

PST-PC: Problem Solving Treatment in Primary Care

ECT: Electroconvulsive therapy

Source: Adapted and reprinted with permission from Unützer J, Katon WJ, Williams JW, et al. Improving primary care for depression in late life: the design of a multi-center randomized trial. Medical Care 2001;39:785.

How impact was tested

The IMPACT team care model has been tested in a randomized trial with 1,801 depressed older adults from 18 primary care clinics in 8 U.S. health care organizations. These included feefor-service plans, health maintenance organizations, and Veterans Affairs clinics with more than 450 PCPs in rural and urban settings.

Patients were randomly assigned to receive IMPACT care for 12 months or care as usual (in usual care, the patient and provider were informed that the patient met diagnostic criteria for major depression or dysthymia). Patients assigned to usual care could engage in any depression treatment the provider normally used, including referral to specialty mental health services.14

Result: Better outcomes. IMPACT was more effective than usual care for late-life depression in all 8 organizations over 2 years.15,16 Overall, IMPACT doubled the effect of usual care. IMPACT patients:

- experienced >100 additional depression-free days17

- showed substantial improvements in physical and social functioning15,17 and quality of life,15 even 12 months after IMPACT resources were withdrawn18

- experienced less pain and pain-related functional impairment19

- had significantly less suicidal ideation.20

IMPACT care also was more cost-effective than usual care for depression in older adults with and without comorbid medical illnesses.17

From research to practice

Based on the robust study outcomes, researchers received a grant from the John A. Hartford Foundation to provide materials, training, and technical assistance to organizations interested in adopting IMPACT. More than 20 health care organizations have used IMPACT, and several have completed program evaluations showing outcomes matching the original IMPACT trial’s.

Kaiser Permanente of Southern California serves 3 million members. Before adopting collaborative care for depression, Kaiser conducted a pilot study of the project IMPACT model modified to fit its health care system. Adaptations included:

- expanding the program to serve depressed adults of all ages

- adding medical assistants to the care team to help with patient follow-up

- adding a “depression class” to offer group-based patient education

- providing psychiatric consultation to the care manager and primary care providers by telephone.

Kaiser investigators compared the outcomes of 300 patients who experienced the adapted program with outcomes in 140 usual-care patients and 140 intervention patients in the original IMPACT study. The effects on depression symptoms were equal to those achieved in the original IMPACT study, with 68% of depressed older adults showing substantial improvement (at least a 50% reduction in depression symptoms) at 6 months.21

- Project IMPACT. www.impact-uw.org.

- American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry. www.aagpgpa.org.

- Positive Aging Resource Center. http://positiveaging.org.

Acknowledgment

This paper is based on a presentation by Dr. Unützer for the Distinguished Scientist Award at the American Association of Geriatric Psychiatry annual meeting in Puerto Rico, March 10, 2006.

Few depressed older adults seek help from psychiatrists. Those who receive mental health treatment most likely do so in primary care settings. Yet primary care physicians (PCPs) often are ill-equipped to effectively treat depression while managing older patients’ numerous acute and chronic medical conditions.

If depressed older patients won’t go to a psychiatrist, why not bring the psychiatrist to the patients? This article describes a clinically tested approach called project IMPACT that links psychiatrists to primary care teams and dramatically improves depression treatment in older adults.

Untreated geriatric depression

Preference for primary care. Major depression is rare in community-living older adults (1% to 3% prevalence), but:

- 5% to 10% of older primary care patients meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for major depression1

- approximately one-half of depressed older adults report a primary care visit when a mental health problem was addressed during the past year.2

- Prefer treatment in primary care instead of mental health settings

- Only 50% follow through on mental health referrals

- Only 20% improve when treated in primary care without a team approach

- Chronic medical illnesses often complicate diagnosis and treatment