User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Can virtual reality help your patients?

Imagine helping your patient overcome acrophobia by sending her “up” to the 80th floor, or telling a patient to get “behind the wheel” to see if he can drive safely.

The ability to simulate real situations with virtual reality (VR) technology has shown promise for treating phobias, assessing patient function, diagnosing anxiety disorders, and other psychiatric clinical applications. Though used predominantly in academic settings, technological advances have made VR less expensive and more “realistic.”

VR’s early promise

In 1991, psychiatrists were introduced to VR at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. By donning a headset and cyber glove, exhibit hall passers-by could tour the optic nerve.

The experience revealed VR’s promise and limitations. The head-mounted display (HMD) was heavy, graphics were rudimentary, and distracting delays between user movements and visuals plagued the tracking system. Also, the system cost about $50,000. Even so, this glimpse of a burgeoning technology wowed participants. I was sure that VR would become commonplace within a few years.

Fifteen years later, however, VR remains on the cutting edge, mostly because no VR application has been popular enough to drive its use. Consumer demand for more-intuitive and interactive electronic games has pushed computer development in many areas, but most gamers consider VR too awkward and nausea producing to justify the expense.

VR Advances

Some industries—particularly aerospace and the military—took interest in simulating objects and environments and spearheaded gradual improvements to VR technology. HMDs are lighter, graphic displays and sounds are more realistic, and touch, smell, and other sensory inputs can be added. Many VR systems run on today’s faster personal computers.

Virtually Better, a corporation formed in 2000 by researchers at Georgia Tech’s Graphics Visualization and Usability (GVU) Center, develops applications for VR systems and licenses and supports the hardware and software for psychiatric clinical uses.

Virtually Better has improved VR technology and greatly broadened the situations targeted for desensitization—from airplane flights, storms, and combat, to job interviews, public speaking, and environments that cue substance use. The GVU center uses VR to simulate a skyscraper and elevator, and VR systems can create a virtual Vietnam, World Trade Center, or “crack house.”

VR in psychiatric care

Exposure therapy. The GVU Center uses VR to expose patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and various phobias to feared stimuli.1 The center uses a virtual skyscraper and elevator to treat acrophobia, for example.

Assessing patient function. The ability to create controlled, predictable conditions that mimic real-world situations could also help assess patient function:

- Rizzo et al have shown that the current battery of tests used to gauge ability to drive2 does not adequately predict real-world driver safety. His team is experimenting with driving simulators as being more accurate than routine cognitive testing and safer than a real road test.

- Zhang et al3 used a virtual kitchen to assess patients’ functioning after a brain injury. Two assessments 7 to 10 days apart showed the patients were less able than non-injured controls to process information, identify logical sequencing, and complete the assessment. The findings suggest that a virtual environment can supplement traditional rehabilitation assessment.

Diagnosis. VR could be used to diagnose and treat primary psychiatric disorders. By “creating” people and environments, psychiatrists could invent standardized interpersonal interactions that would be difficult to duplicate in the real world.

Freeman et al4 created a neutral virtual environment (a library) populated by computer-generated characters. The investigators used a Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE) system to project images on the walls while subjects wore 3-D glasses, allowing them to walk through the environment. The subjects, college students without psychiatric disorders, then recorded their thoughts after interacting with the characters. Though most experiences were positive, some reported ideas of reference and persecutory thoughts. These students were more likely than those without such thoughts to report anxiety and high interpersonal sensitivity.

Although the study was devised to investigate how persecutory thoughts originate, it also showed how VR convincingly replicates human interaction, suggesting endless treatment possibilities.

Further research will determine whether:

- VR offers a tangible advantage over more-traditional techniques

- that advantage would justify the expense of a VR system.

Can VR help your patients?

VR system prices, though still substantial, have decreased considerably over 15 years. Depending on configuration, hardware/software systems supported by Virtually Better cost $5,500 to $7,000.

Third-party payers generally have been covering VR, and some VR therapists are “preferred providers” for major insurers in their areas. Some providers bill the insurer, while others request payment up front and require the patient to seek reimbursement.

Related resources

HPCCV Publications. The CAVE: A virtual reality theater. http://www.evl.uic.edu/pape/CAVE/oldCAVE/CAVE.html

Georgia Institute of Technology. Graphics Visualization & Usability (GVU) Center. http://www-static.cc.gatech.edu/gvu

Virtually Better www.virtuallybetter.com

Disclosure

Dr. Boland report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products. The opinions he expresses in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

1. Luo JL. In a virtual world, games can be therapeutic. Current Psychiatry 2002;1(9). Available at: http://www.currentpsychiatry.com/article_pages.asp?AID=549&UID=14468. Accessed February 22, 2006.

2. Carroll L. Better methods needed to determine driver safety in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology Today 2004;4(10):1,14-16.

3. Zhang L, Abreu BC, Masel B, et al. Virtual reality in the assessment of selected cognitive function after brain injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001;80:597-604

4. Freeman D, Slater M, Bebbington PE, et al. Can virtual reality be used to investigate persecutory ideation? J Nerv Ment Dis 2003;191:509-14.

Imagine helping your patient overcome acrophobia by sending her “up” to the 80th floor, or telling a patient to get “behind the wheel” to see if he can drive safely.

The ability to simulate real situations with virtual reality (VR) technology has shown promise for treating phobias, assessing patient function, diagnosing anxiety disorders, and other psychiatric clinical applications. Though used predominantly in academic settings, technological advances have made VR less expensive and more “realistic.”

VR’s early promise

In 1991, psychiatrists were introduced to VR at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. By donning a headset and cyber glove, exhibit hall passers-by could tour the optic nerve.

The experience revealed VR’s promise and limitations. The head-mounted display (HMD) was heavy, graphics were rudimentary, and distracting delays between user movements and visuals plagued the tracking system. Also, the system cost about $50,000. Even so, this glimpse of a burgeoning technology wowed participants. I was sure that VR would become commonplace within a few years.

Fifteen years later, however, VR remains on the cutting edge, mostly because no VR application has been popular enough to drive its use. Consumer demand for more-intuitive and interactive electronic games has pushed computer development in many areas, but most gamers consider VR too awkward and nausea producing to justify the expense.

VR Advances

Some industries—particularly aerospace and the military—took interest in simulating objects and environments and spearheaded gradual improvements to VR technology. HMDs are lighter, graphic displays and sounds are more realistic, and touch, smell, and other sensory inputs can be added. Many VR systems run on today’s faster personal computers.

Virtually Better, a corporation formed in 2000 by researchers at Georgia Tech’s Graphics Visualization and Usability (GVU) Center, develops applications for VR systems and licenses and supports the hardware and software for psychiatric clinical uses.

Virtually Better has improved VR technology and greatly broadened the situations targeted for desensitization—from airplane flights, storms, and combat, to job interviews, public speaking, and environments that cue substance use. The GVU center uses VR to simulate a skyscraper and elevator, and VR systems can create a virtual Vietnam, World Trade Center, or “crack house.”

VR in psychiatric care

Exposure therapy. The GVU Center uses VR to expose patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and various phobias to feared stimuli.1 The center uses a virtual skyscraper and elevator to treat acrophobia, for example.

Assessing patient function. The ability to create controlled, predictable conditions that mimic real-world situations could also help assess patient function:

- Rizzo et al have shown that the current battery of tests used to gauge ability to drive2 does not adequately predict real-world driver safety. His team is experimenting with driving simulators as being more accurate than routine cognitive testing and safer than a real road test.

- Zhang et al3 used a virtual kitchen to assess patients’ functioning after a brain injury. Two assessments 7 to 10 days apart showed the patients were less able than non-injured controls to process information, identify logical sequencing, and complete the assessment. The findings suggest that a virtual environment can supplement traditional rehabilitation assessment.

Diagnosis. VR could be used to diagnose and treat primary psychiatric disorders. By “creating” people and environments, psychiatrists could invent standardized interpersonal interactions that would be difficult to duplicate in the real world.

Freeman et al4 created a neutral virtual environment (a library) populated by computer-generated characters. The investigators used a Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE) system to project images on the walls while subjects wore 3-D glasses, allowing them to walk through the environment. The subjects, college students without psychiatric disorders, then recorded their thoughts after interacting with the characters. Though most experiences were positive, some reported ideas of reference and persecutory thoughts. These students were more likely than those without such thoughts to report anxiety and high interpersonal sensitivity.

Although the study was devised to investigate how persecutory thoughts originate, it also showed how VR convincingly replicates human interaction, suggesting endless treatment possibilities.

Further research will determine whether:

- VR offers a tangible advantage over more-traditional techniques

- that advantage would justify the expense of a VR system.

Can VR help your patients?

VR system prices, though still substantial, have decreased considerably over 15 years. Depending on configuration, hardware/software systems supported by Virtually Better cost $5,500 to $7,000.

Third-party payers generally have been covering VR, and some VR therapists are “preferred providers” for major insurers in their areas. Some providers bill the insurer, while others request payment up front and require the patient to seek reimbursement.

Related resources

HPCCV Publications. The CAVE: A virtual reality theater. http://www.evl.uic.edu/pape/CAVE/oldCAVE/CAVE.html

Georgia Institute of Technology. Graphics Visualization & Usability (GVU) Center. http://www-static.cc.gatech.edu/gvu

Virtually Better www.virtuallybetter.com

Disclosure

Dr. Boland report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products. The opinions he expresses in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

Imagine helping your patient overcome acrophobia by sending her “up” to the 80th floor, or telling a patient to get “behind the wheel” to see if he can drive safely.

The ability to simulate real situations with virtual reality (VR) technology has shown promise for treating phobias, assessing patient function, diagnosing anxiety disorders, and other psychiatric clinical applications. Though used predominantly in academic settings, technological advances have made VR less expensive and more “realistic.”

VR’s early promise

In 1991, psychiatrists were introduced to VR at the American Psychiatric Association annual meeting. By donning a headset and cyber glove, exhibit hall passers-by could tour the optic nerve.

The experience revealed VR’s promise and limitations. The head-mounted display (HMD) was heavy, graphics were rudimentary, and distracting delays between user movements and visuals plagued the tracking system. Also, the system cost about $50,000. Even so, this glimpse of a burgeoning technology wowed participants. I was sure that VR would become commonplace within a few years.

Fifteen years later, however, VR remains on the cutting edge, mostly because no VR application has been popular enough to drive its use. Consumer demand for more-intuitive and interactive electronic games has pushed computer development in many areas, but most gamers consider VR too awkward and nausea producing to justify the expense.

VR Advances

Some industries—particularly aerospace and the military—took interest in simulating objects and environments and spearheaded gradual improvements to VR technology. HMDs are lighter, graphic displays and sounds are more realistic, and touch, smell, and other sensory inputs can be added. Many VR systems run on today’s faster personal computers.

Virtually Better, a corporation formed in 2000 by researchers at Georgia Tech’s Graphics Visualization and Usability (GVU) Center, develops applications for VR systems and licenses and supports the hardware and software for psychiatric clinical uses.

Virtually Better has improved VR technology and greatly broadened the situations targeted for desensitization—from airplane flights, storms, and combat, to job interviews, public speaking, and environments that cue substance use. The GVU center uses VR to simulate a skyscraper and elevator, and VR systems can create a virtual Vietnam, World Trade Center, or “crack house.”

VR in psychiatric care

Exposure therapy. The GVU Center uses VR to expose patients with posttraumatic stress disorder and various phobias to feared stimuli.1 The center uses a virtual skyscraper and elevator to treat acrophobia, for example.

Assessing patient function. The ability to create controlled, predictable conditions that mimic real-world situations could also help assess patient function:

- Rizzo et al have shown that the current battery of tests used to gauge ability to drive2 does not adequately predict real-world driver safety. His team is experimenting with driving simulators as being more accurate than routine cognitive testing and safer than a real road test.

- Zhang et al3 used a virtual kitchen to assess patients’ functioning after a brain injury. Two assessments 7 to 10 days apart showed the patients were less able than non-injured controls to process information, identify logical sequencing, and complete the assessment. The findings suggest that a virtual environment can supplement traditional rehabilitation assessment.

Diagnosis. VR could be used to diagnose and treat primary psychiatric disorders. By “creating” people and environments, psychiatrists could invent standardized interpersonal interactions that would be difficult to duplicate in the real world.

Freeman et al4 created a neutral virtual environment (a library) populated by computer-generated characters. The investigators used a Cave Automatic Virtual Environment (CAVE) system to project images on the walls while subjects wore 3-D glasses, allowing them to walk through the environment. The subjects, college students without psychiatric disorders, then recorded their thoughts after interacting with the characters. Though most experiences were positive, some reported ideas of reference and persecutory thoughts. These students were more likely than those without such thoughts to report anxiety and high interpersonal sensitivity.

Although the study was devised to investigate how persecutory thoughts originate, it also showed how VR convincingly replicates human interaction, suggesting endless treatment possibilities.

Further research will determine whether:

- VR offers a tangible advantage over more-traditional techniques

- that advantage would justify the expense of a VR system.

Can VR help your patients?

VR system prices, though still substantial, have decreased considerably over 15 years. Depending on configuration, hardware/software systems supported by Virtually Better cost $5,500 to $7,000.

Third-party payers generally have been covering VR, and some VR therapists are “preferred providers” for major insurers in their areas. Some providers bill the insurer, while others request payment up front and require the patient to seek reimbursement.

Related resources

HPCCV Publications. The CAVE: A virtual reality theater. http://www.evl.uic.edu/pape/CAVE/oldCAVE/CAVE.html

Georgia Institute of Technology. Graphics Visualization & Usability (GVU) Center. http://www-static.cc.gatech.edu/gvu

Virtually Better www.virtuallybetter.com

Disclosure

Dr. Boland report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products. The opinions he expresses in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

1. Luo JL. In a virtual world, games can be therapeutic. Current Psychiatry 2002;1(9). Available at: http://www.currentpsychiatry.com/article_pages.asp?AID=549&UID=14468. Accessed February 22, 2006.

2. Carroll L. Better methods needed to determine driver safety in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology Today 2004;4(10):1,14-16.

3. Zhang L, Abreu BC, Masel B, et al. Virtual reality in the assessment of selected cognitive function after brain injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001;80:597-604

4. Freeman D, Slater M, Bebbington PE, et al. Can virtual reality be used to investigate persecutory ideation? J Nerv Ment Dis 2003;191:509-14.

1. Luo JL. In a virtual world, games can be therapeutic. Current Psychiatry 2002;1(9). Available at: http://www.currentpsychiatry.com/article_pages.asp?AID=549&UID=14468. Accessed February 22, 2006.

2. Carroll L. Better methods needed to determine driver safety in early Alzheimer disease. Neurology Today 2004;4(10):1,14-16.

3. Zhang L, Abreu BC, Masel B, et al. Virtual reality in the assessment of selected cognitive function after brain injury. Am J Phys Med Rehabil 2001;80:597-604

4. Freeman D, Slater M, Bebbington PE, et al. Can virtual reality be used to investigate persecutory ideation? J Nerv Ment Dis 2003;191:509-14.

5-step ‘listen therapy’ for somatic complaints

Patients referred to you with somatic complaints are frustrated that no one understands how they feel. Suggesting a psychological cause for their symptoms often triggers disbelief, resistance, or denial.

Hearing these patient’s feelings affirms that you are not dismissing their concerns. We have found the following 5-step, systematized approach helpful for validating somatic symptoms. Supportive psychotherapy1 also can help patients develop coping mechanisms or recall skills learned elsewhere.

STEP 1

Give patients an opportunity to outline their physical symptoms. Listen to their complaints without interrupting—except for clarification—or offering solutions. Emphasize that all illnesses have a physical basis and ask about prior workups.

STEP 2

Acknowledge how difficult it must be to have these symptoms. Be nonverbally attentive: maintain good eye contact, show concern, display a relaxed posture and demeanor, and give undivided attention. Keep your phone and beeper off or turned down if possible.

STEP 3

Encourage patients to devise solutions, or help them acknowledge ways they have coped with the problem previously. Discuss responses and support the use of constructive strategies.

If patients say nothing has worked for them, ask what they have tried and whether these “trials” were adequate. Some patients, such as those with personality disorders, may naysay suggestions or be unwilling to find solutions. Empathize again with their frustration, and go to step 4.

STEP 4

Present a tentative suggestion, but leave it to patients to implement when they are ready. For example, recommend that a patient complaining of light-headedness get up from bed slowly to decrease dizziness. Ask whether your suggestion sounds reasonable and how difficult it would be to do.

STEP 5

Patients who are not receptive to suggested interventions might inadvertently convey what they want—such as a referral to a specialist or to see you more frequently. Again, start with what patients present as solutions and discuss their feasibility.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Alan D. Schmetzer, MD, for his contributions to this article.

Reference

1. Pinsker H. The supportive component of psychotherapy. Psychiatric Times 1998;15(11). Available at: http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/p981160.html. Accessed March 1, 2006.

Dr. Bhagar is assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, and staff psychiatrist, Larue Carter Hospital, Indianapolis, IN.

Dr. Pisano is assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, and staff psychologist, Larue Carter Hospital.

Patients referred to you with somatic complaints are frustrated that no one understands how they feel. Suggesting a psychological cause for their symptoms often triggers disbelief, resistance, or denial.

Hearing these patient’s feelings affirms that you are not dismissing their concerns. We have found the following 5-step, systematized approach helpful for validating somatic symptoms. Supportive psychotherapy1 also can help patients develop coping mechanisms or recall skills learned elsewhere.

STEP 1

Give patients an opportunity to outline their physical symptoms. Listen to their complaints without interrupting—except for clarification—or offering solutions. Emphasize that all illnesses have a physical basis and ask about prior workups.

STEP 2

Acknowledge how difficult it must be to have these symptoms. Be nonverbally attentive: maintain good eye contact, show concern, display a relaxed posture and demeanor, and give undivided attention. Keep your phone and beeper off or turned down if possible.

STEP 3

Encourage patients to devise solutions, or help them acknowledge ways they have coped with the problem previously. Discuss responses and support the use of constructive strategies.

If patients say nothing has worked for them, ask what they have tried and whether these “trials” were adequate. Some patients, such as those with personality disorders, may naysay suggestions or be unwilling to find solutions. Empathize again with their frustration, and go to step 4.

STEP 4

Present a tentative suggestion, but leave it to patients to implement when they are ready. For example, recommend that a patient complaining of light-headedness get up from bed slowly to decrease dizziness. Ask whether your suggestion sounds reasonable and how difficult it would be to do.

STEP 5

Patients who are not receptive to suggested interventions might inadvertently convey what they want—such as a referral to a specialist or to see you more frequently. Again, start with what patients present as solutions and discuss their feasibility.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Alan D. Schmetzer, MD, for his contributions to this article.

Patients referred to you with somatic complaints are frustrated that no one understands how they feel. Suggesting a psychological cause for their symptoms often triggers disbelief, resistance, or denial.

Hearing these patient’s feelings affirms that you are not dismissing their concerns. We have found the following 5-step, systematized approach helpful for validating somatic symptoms. Supportive psychotherapy1 also can help patients develop coping mechanisms or recall skills learned elsewhere.

STEP 1

Give patients an opportunity to outline their physical symptoms. Listen to their complaints without interrupting—except for clarification—or offering solutions. Emphasize that all illnesses have a physical basis and ask about prior workups.

STEP 2

Acknowledge how difficult it must be to have these symptoms. Be nonverbally attentive: maintain good eye contact, show concern, display a relaxed posture and demeanor, and give undivided attention. Keep your phone and beeper off or turned down if possible.

STEP 3

Encourage patients to devise solutions, or help them acknowledge ways they have coped with the problem previously. Discuss responses and support the use of constructive strategies.

If patients say nothing has worked for them, ask what they have tried and whether these “trials” were adequate. Some patients, such as those with personality disorders, may naysay suggestions or be unwilling to find solutions. Empathize again with their frustration, and go to step 4.

STEP 4

Present a tentative suggestion, but leave it to patients to implement when they are ready. For example, recommend that a patient complaining of light-headedness get up from bed slowly to decrease dizziness. Ask whether your suggestion sounds reasonable and how difficult it would be to do.

STEP 5

Patients who are not receptive to suggested interventions might inadvertently convey what they want—such as a referral to a specialist or to see you more frequently. Again, start with what patients present as solutions and discuss their feasibility.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Alan D. Schmetzer, MD, for his contributions to this article.

Reference

1. Pinsker H. The supportive component of psychotherapy. Psychiatric Times 1998;15(11). Available at: http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/p981160.html. Accessed March 1, 2006.

Dr. Bhagar is assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, and staff psychiatrist, Larue Carter Hospital, Indianapolis, IN.

Dr. Pisano is assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, and staff psychologist, Larue Carter Hospital.

Reference

1. Pinsker H. The supportive component of psychotherapy. Psychiatric Times 1998;15(11). Available at: http://www.psychiatrictimes.com/p981160.html. Accessed March 1, 2006.

Dr. Bhagar is assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, and staff psychiatrist, Larue Carter Hospital, Indianapolis, IN.

Dr. Pisano is assistant professor of clinical psychiatry, Indiana University School of Medicine, and staff psychologist, Larue Carter Hospital.

Learning from lab-rat love

What’s a woman to do when sexual encounters become difficult or less satisfying?

- Vascularly directed sexual dysfunction treatments for men are not the answer; phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as sildenafil did no better than placebo among 800 women with various sexual problems.1

- The testosterone patch increases sexual interest for some women but failed to win FDA approval because of long-term safety concerns.

Even more frustrating, libido loss is a common side effect with some widely prescribed psychotropics—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. But an agent shown to boost libido in female rats may give women with sexual dysfunction a pharmaceutical option.

From sunscreen to aphrodisiac

Approximately 10 years ago, University of Arizona researchers studied a melanocortin-stimulating hormone analogue while trying to develop a product to allow light-skinned persons to tan without ultraviolet ray exposure. The product indeed darkened skin, but it also triggered spontaneous erections in all 3 men in the pilot study.2 A modified version of the erection-inducing peptide—now called bremelanotide—is being tested in phase 3 clinical trials as a prospective erectile dysfunction treatment.3

Unlike its predecessors, bremelanotide works directly on neural pathways that control sexual function, rather than on the vascular system. But its highest-interest feature may be its effect on female sexual desire—at least in rats.

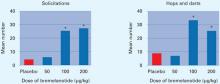

Behavioral neurologist James Pfaus, PhD, identified behaviors female rats use to arouse males—what might be called the rodent equivalent of flirtation. These behaviors include solicitations (meeting head to head with males, then abruptly fleeing), pacing, hops, and darts.

His group then tested the effect of various doses of subcutaneous bremelanotide on 40 ovariectomized female rats primed with estradiol and progesterone.4 Researchers paired each female with a male for 30 minutes and recorded their behaviors. Compared with females who received placebo or low-dose bremelanotide, high-dose bremelanotide females performed significantly more “flirtatious” behaviors (Figure). The researchers attributed this difference to increased sexual desire.

The drug’s mechanism of action remains in question, but it appears to act centrally. Injecting it directly into female rats’ ventricles produced similar behaviors when they were paired with receptive males. Also, markers of neuronal activity have been found in the anterior aspect of the hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens—areas associated with sexual activity and pleasure.

FigureBremelanotide increases sexually solicitous behaviors in female rats

Source: Reference 4. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2004, National Academy of Sciences, USA.

Pilot study in women

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial suggests that bremelanotide as a nasal spray might increase desire in women with female sexual dysfunction (FSD).5 When 18 perimenopausal women with FSD were given bremelanotide or placebo, the bremelanotide group reported greater sexual desire and genital arousal while watching a sexually explicit video.

Specifically, this pilot study—part of the drug’s phase 2 trials in women—found that:

- 72% of women who took bremelanotide reported feelings of genital arousal, compared with 39% in the placebo group

- 67% of treated women experienced sexual desire versus 22% of controls.

Is fsd a pathology?

Some clinicians worry that FSD is a “disease” made up by pharmaceutical industry marketers. They argue that hypoactive sexual desire is not a disorder but an adaptive response to physical changes or relationship difficulties.6

On the other hand, a national survey of 1,749 women and 1,410 men ages 18 to 59 found sexual difficulties to be more prevalent in women than in men:7

- 43% of women reported sexual dysfunction, compared with 31% of men.

- 26% of women reported inability to achieve orgasm compared with 8% of men.

An effective and safe medication targeted at improving women’s sexual desire might help some patients, such as peri- or postmenopausal women, in otherwise healthy relationships.

1. Basson R, McInnes R, Smith MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. J Womens Health Gen Based Med 2002;11(4):367-77.

2. Dorr RT, Lines R, Levine N, et al. Evaluation of melanotan-II, a superpotent cyclic melanotropic peptide in a pilot phase-I clinical study. Life Sci 1996;58(20):1777-84.

3. Molinoff PB, Shadiack AM, Earle D, et al. PT-141: A melanocortin agonist for the treatment of sexual dysfunction. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003;994:96-102.

4. Pfaus JG, Shadiack A, Van Soest T, et al. Selective facilitation of sexual solicitation in the female rat by a melanocortin receptor agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101(27):10201-4.

5. Perelman MA, Diamond LE, Earle DC, et al. The potential role of bremelanotide (PT-141) as a pharmacologic intervention for FSD. Poster presented at: International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health annual meeting; March 10, 2006; Lisbon, Portugal.

6. Moynihan R. The marketing of a disease: female sexual dysfunction. BMJ 2005;330(7484):192-4.

7. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281(6):537-44.

What’s a woman to do when sexual encounters become difficult or less satisfying?

- Vascularly directed sexual dysfunction treatments for men are not the answer; phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as sildenafil did no better than placebo among 800 women with various sexual problems.1

- The testosterone patch increases sexual interest for some women but failed to win FDA approval because of long-term safety concerns.

Even more frustrating, libido loss is a common side effect with some widely prescribed psychotropics—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. But an agent shown to boost libido in female rats may give women with sexual dysfunction a pharmaceutical option.

From sunscreen to aphrodisiac

Approximately 10 years ago, University of Arizona researchers studied a melanocortin-stimulating hormone analogue while trying to develop a product to allow light-skinned persons to tan without ultraviolet ray exposure. The product indeed darkened skin, but it also triggered spontaneous erections in all 3 men in the pilot study.2 A modified version of the erection-inducing peptide—now called bremelanotide—is being tested in phase 3 clinical trials as a prospective erectile dysfunction treatment.3

Unlike its predecessors, bremelanotide works directly on neural pathways that control sexual function, rather than on the vascular system. But its highest-interest feature may be its effect on female sexual desire—at least in rats.

Behavioral neurologist James Pfaus, PhD, identified behaviors female rats use to arouse males—what might be called the rodent equivalent of flirtation. These behaviors include solicitations (meeting head to head with males, then abruptly fleeing), pacing, hops, and darts.

His group then tested the effect of various doses of subcutaneous bremelanotide on 40 ovariectomized female rats primed with estradiol and progesterone.4 Researchers paired each female with a male for 30 minutes and recorded their behaviors. Compared with females who received placebo or low-dose bremelanotide, high-dose bremelanotide females performed significantly more “flirtatious” behaviors (Figure). The researchers attributed this difference to increased sexual desire.

The drug’s mechanism of action remains in question, but it appears to act centrally. Injecting it directly into female rats’ ventricles produced similar behaviors when they were paired with receptive males. Also, markers of neuronal activity have been found in the anterior aspect of the hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens—areas associated with sexual activity and pleasure.

FigureBremelanotide increases sexually solicitous behaviors in female rats

Source: Reference 4. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2004, National Academy of Sciences, USA.

Pilot study in women

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial suggests that bremelanotide as a nasal spray might increase desire in women with female sexual dysfunction (FSD).5 When 18 perimenopausal women with FSD were given bremelanotide or placebo, the bremelanotide group reported greater sexual desire and genital arousal while watching a sexually explicit video.

Specifically, this pilot study—part of the drug’s phase 2 trials in women—found that:

- 72% of women who took bremelanotide reported feelings of genital arousal, compared with 39% in the placebo group

- 67% of treated women experienced sexual desire versus 22% of controls.

Is fsd a pathology?

Some clinicians worry that FSD is a “disease” made up by pharmaceutical industry marketers. They argue that hypoactive sexual desire is not a disorder but an adaptive response to physical changes or relationship difficulties.6

On the other hand, a national survey of 1,749 women and 1,410 men ages 18 to 59 found sexual difficulties to be more prevalent in women than in men:7

- 43% of women reported sexual dysfunction, compared with 31% of men.

- 26% of women reported inability to achieve orgasm compared with 8% of men.

An effective and safe medication targeted at improving women’s sexual desire might help some patients, such as peri- or postmenopausal women, in otherwise healthy relationships.

What’s a woman to do when sexual encounters become difficult or less satisfying?

- Vascularly directed sexual dysfunction treatments for men are not the answer; phosphodiesterase inhibitors such as sildenafil did no better than placebo among 800 women with various sexual problems.1

- The testosterone patch increases sexual interest for some women but failed to win FDA approval because of long-term safety concerns.

Even more frustrating, libido loss is a common side effect with some widely prescribed psychotropics—such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors. But an agent shown to boost libido in female rats may give women with sexual dysfunction a pharmaceutical option.

From sunscreen to aphrodisiac

Approximately 10 years ago, University of Arizona researchers studied a melanocortin-stimulating hormone analogue while trying to develop a product to allow light-skinned persons to tan without ultraviolet ray exposure. The product indeed darkened skin, but it also triggered spontaneous erections in all 3 men in the pilot study.2 A modified version of the erection-inducing peptide—now called bremelanotide—is being tested in phase 3 clinical trials as a prospective erectile dysfunction treatment.3

Unlike its predecessors, bremelanotide works directly on neural pathways that control sexual function, rather than on the vascular system. But its highest-interest feature may be its effect on female sexual desire—at least in rats.

Behavioral neurologist James Pfaus, PhD, identified behaviors female rats use to arouse males—what might be called the rodent equivalent of flirtation. These behaviors include solicitations (meeting head to head with males, then abruptly fleeing), pacing, hops, and darts.

His group then tested the effect of various doses of subcutaneous bremelanotide on 40 ovariectomized female rats primed with estradiol and progesterone.4 Researchers paired each female with a male for 30 minutes and recorded their behaviors. Compared with females who received placebo or low-dose bremelanotide, high-dose bremelanotide females performed significantly more “flirtatious” behaviors (Figure). The researchers attributed this difference to increased sexual desire.

The drug’s mechanism of action remains in question, but it appears to act centrally. Injecting it directly into female rats’ ventricles produced similar behaviors when they were paired with receptive males. Also, markers of neuronal activity have been found in the anterior aspect of the hypothalamus and nucleus accumbens—areas associated with sexual activity and pleasure.

FigureBremelanotide increases sexually solicitous behaviors in female rats

Source: Reference 4. Reprinted with permission. Copyright 2004, National Academy of Sciences, USA.

Pilot study in women

A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover trial suggests that bremelanotide as a nasal spray might increase desire in women with female sexual dysfunction (FSD).5 When 18 perimenopausal women with FSD were given bremelanotide or placebo, the bremelanotide group reported greater sexual desire and genital arousal while watching a sexually explicit video.

Specifically, this pilot study—part of the drug’s phase 2 trials in women—found that:

- 72% of women who took bremelanotide reported feelings of genital arousal, compared with 39% in the placebo group

- 67% of treated women experienced sexual desire versus 22% of controls.

Is fsd a pathology?

Some clinicians worry that FSD is a “disease” made up by pharmaceutical industry marketers. They argue that hypoactive sexual desire is not a disorder but an adaptive response to physical changes or relationship difficulties.6

On the other hand, a national survey of 1,749 women and 1,410 men ages 18 to 59 found sexual difficulties to be more prevalent in women than in men:7

- 43% of women reported sexual dysfunction, compared with 31% of men.

- 26% of women reported inability to achieve orgasm compared with 8% of men.

An effective and safe medication targeted at improving women’s sexual desire might help some patients, such as peri- or postmenopausal women, in otherwise healthy relationships.

1. Basson R, McInnes R, Smith MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. J Womens Health Gen Based Med 2002;11(4):367-77.

2. Dorr RT, Lines R, Levine N, et al. Evaluation of melanotan-II, a superpotent cyclic melanotropic peptide in a pilot phase-I clinical study. Life Sci 1996;58(20):1777-84.

3. Molinoff PB, Shadiack AM, Earle D, et al. PT-141: A melanocortin agonist for the treatment of sexual dysfunction. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003;994:96-102.

4. Pfaus JG, Shadiack A, Van Soest T, et al. Selective facilitation of sexual solicitation in the female rat by a melanocortin receptor agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101(27):10201-4.

5. Perelman MA, Diamond LE, Earle DC, et al. The potential role of bremelanotide (PT-141) as a pharmacologic intervention for FSD. Poster presented at: International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health annual meeting; March 10, 2006; Lisbon, Portugal.

6. Moynihan R. The marketing of a disease: female sexual dysfunction. BMJ 2005;330(7484):192-4.

7. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281(6):537-44.

1. Basson R, McInnes R, Smith MD, et al. Efficacy and safety of sildenafil citrate in women with sexual dysfunction associated with female sexual arousal disorder. J Womens Health Gen Based Med 2002;11(4):367-77.

2. Dorr RT, Lines R, Levine N, et al. Evaluation of melanotan-II, a superpotent cyclic melanotropic peptide in a pilot phase-I clinical study. Life Sci 1996;58(20):1777-84.

3. Molinoff PB, Shadiack AM, Earle D, et al. PT-141: A melanocortin agonist for the treatment of sexual dysfunction. Ann NY Acad Sci 2003;994:96-102.

4. Pfaus JG, Shadiack A, Van Soest T, et al. Selective facilitation of sexual solicitation in the female rat by a melanocortin receptor agonist. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101(27):10201-4.

5. Perelman MA, Diamond LE, Earle DC, et al. The potential role of bremelanotide (PT-141) as a pharmacologic intervention for FSD. Poster presented at: International Society for the Study of Women’s Sexual Health annual meeting; March 10, 2006; Lisbon, Portugal.

6. Moynihan R. The marketing of a disease: female sexual dysfunction. BMJ 2005;330(7484):192-4.

7. Laumann EO, Paik A, Rosen RC. Sexual dysfunction in the United States: prevalence and predictors. JAMA 1999;281(6):537-44.

Correction

In the figure that accompanied “Out of the Pipeline: Intramuscular naltrexone“ (Current Psychiatry, March 2006,), median heavy drinking days per month should have been listed without percent signs.

In the figure that accompanied “Out of the Pipeline: Intramuscular naltrexone“ (Current Psychiatry, March 2006,), median heavy drinking days per month should have been listed without percent signs.

In the figure that accompanied “Out of the Pipeline: Intramuscular naltrexone“ (Current Psychiatry, March 2006,), median heavy drinking days per month should have been listed without percent signs.

Schizophrenia: a diagnosis of exclusion

There are two ways to diagnose a disorder: List the symptoms and history, or observe response to treatment. If the patient appears to have schizophrenia but responds exceptionally well to lithium, we would naturally suspect bipolar disorder.

I once proposed studying patients who appear to have schizophrenia—as defined by the leading researchers of the disorder—while treating them with anything but a neuroleptic. The study, if successful, would show similar remission rates (without neuroleptics) among patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. A certain number of patients with bipolar disorder require neuroleptics for stability.

In any case, I believe that true schizophrenia is quite rare and should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion. (Current Psychiatry, March 2006) Most patients diagnosed with schizophrenia have some combination of bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit disorder, panic disorder, and/or seizure disorder. Treating these patients correctly requires much sophistication and creativity while considering all psychotropics with or without neuroleptics.

David Corwin, MD

Paramus, NJ

There are two ways to diagnose a disorder: List the symptoms and history, or observe response to treatment. If the patient appears to have schizophrenia but responds exceptionally well to lithium, we would naturally suspect bipolar disorder.

I once proposed studying patients who appear to have schizophrenia—as defined by the leading researchers of the disorder—while treating them with anything but a neuroleptic. The study, if successful, would show similar remission rates (without neuroleptics) among patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. A certain number of patients with bipolar disorder require neuroleptics for stability.

In any case, I believe that true schizophrenia is quite rare and should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion. (Current Psychiatry, March 2006) Most patients diagnosed with schizophrenia have some combination of bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit disorder, panic disorder, and/or seizure disorder. Treating these patients correctly requires much sophistication and creativity while considering all psychotropics with or without neuroleptics.

David Corwin, MD

Paramus, NJ

There are two ways to diagnose a disorder: List the symptoms and history, or observe response to treatment. If the patient appears to have schizophrenia but responds exceptionally well to lithium, we would naturally suspect bipolar disorder.

I once proposed studying patients who appear to have schizophrenia—as defined by the leading researchers of the disorder—while treating them with anything but a neuroleptic. The study, if successful, would show similar remission rates (without neuroleptics) among patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. A certain number of patients with bipolar disorder require neuroleptics for stability.

In any case, I believe that true schizophrenia is quite rare and should be considered a diagnosis of exclusion. (Current Psychiatry, March 2006) Most patients diagnosed with schizophrenia have some combination of bipolar disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, attention-deficit disorder, panic disorder, and/or seizure disorder. Treating these patients correctly requires much sophistication and creativity while considering all psychotropics with or without neuroleptics.

David Corwin, MD

Paramus, NJ

‘Wrong-headed nosology’

Interepisode phenomenology of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are qualitatively different (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Printing Drs. Lake and Hurwitz’ wrong-headed nosology disserves patients because impressionable residents and students reading about it might take it as truth and adopt it unexamined.

I also fear that the authors have been swayed by the idea that DSM-IV-TR is necessarily valid. DSM-IV ensures that all disorders are called by the same names but may or may not represent valid conceptions of mental life and its disorders.

I do agree in part with rejecting the notion of “schizoaffective disorder,” as the term is grossly overused. I think “schizoaffective” is often an easy shorthand for “bad mental illness” and is too frequently used without considering the psychopathologic phenomenology evident over the course of the patient’s life.

Mark Mollenhauer, MD

Mental Illness—Substance Abuse Program

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD

Interepisode phenomenology of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are qualitatively different (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Printing Drs. Lake and Hurwitz’ wrong-headed nosology disserves patients because impressionable residents and students reading about it might take it as truth and adopt it unexamined.

I also fear that the authors have been swayed by the idea that DSM-IV-TR is necessarily valid. DSM-IV ensures that all disorders are called by the same names but may or may not represent valid conceptions of mental life and its disorders.

I do agree in part with rejecting the notion of “schizoaffective disorder,” as the term is grossly overused. I think “schizoaffective” is often an easy shorthand for “bad mental illness” and is too frequently used without considering the psychopathologic phenomenology evident over the course of the patient’s life.

Mark Mollenhauer, MD

Mental Illness—Substance Abuse Program

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD

Interepisode phenomenology of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are qualitatively different (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Printing Drs. Lake and Hurwitz’ wrong-headed nosology disserves patients because impressionable residents and students reading about it might take it as truth and adopt it unexamined.

I also fear that the authors have been swayed by the idea that DSM-IV-TR is necessarily valid. DSM-IV ensures that all disorders are called by the same names but may or may not represent valid conceptions of mental life and its disorders.

I do agree in part with rejecting the notion of “schizoaffective disorder,” as the term is grossly overused. I think “schizoaffective” is often an easy shorthand for “bad mental illness” and is too frequently used without considering the psychopathologic phenomenology evident over the course of the patient’s life.

Mark Mollenhauer, MD

Mental Illness—Substance Abuse Program

Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, Baltimore, MD

‘Fuzzy’ diagnostic boundaries

Kudos to Drs. Lake and Hurwitz for bringing to the fore an issue that deserves much more attention than it gets in psychiatry’s academic circles (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Their opinion remains in the minority not because their argument is invalid, but because:

1) We find it difficult to accept that the boundaries between psychiatric disorders are much fuzzier than what DSM-IV-TR suggests. We fear that doing so will cost us our hard-earned ostensive legitimacy as a medical discipline.

2) As most atypical antipsychotics are indicated for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, one can justify use of any atypical for either disorder, even if the diagnosis is not entirely accurate.

Questioning the validity of a diagnostic construct (not a disease) should not be considered a “scientific transgression,” as Dr. Nasrallah puts it. After all, we still have not reached an international consensus on how long symptoms must be present before we diagnose schizophrenia (DSM-IV-TR says 6 months, ICD-10 says 1 month).

Jatinder P. Babbar, MD

Carilion University of Virginia

Roanoke Valley Program, University of Virginia

Salem, VA

Kudos to Drs. Lake and Hurwitz for bringing to the fore an issue that deserves much more attention than it gets in psychiatry’s academic circles (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Their opinion remains in the minority not because their argument is invalid, but because:

1) We find it difficult to accept that the boundaries between psychiatric disorders are much fuzzier than what DSM-IV-TR suggests. We fear that doing so will cost us our hard-earned ostensive legitimacy as a medical discipline.

2) As most atypical antipsychotics are indicated for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, one can justify use of any atypical for either disorder, even if the diagnosis is not entirely accurate.

Questioning the validity of a diagnostic construct (not a disease) should not be considered a “scientific transgression,” as Dr. Nasrallah puts it. After all, we still have not reached an international consensus on how long symptoms must be present before we diagnose schizophrenia (DSM-IV-TR says 6 months, ICD-10 says 1 month).

Jatinder P. Babbar, MD

Carilion University of Virginia

Roanoke Valley Program, University of Virginia

Salem, VA

Kudos to Drs. Lake and Hurwitz for bringing to the fore an issue that deserves much more attention than it gets in psychiatry’s academic circles (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Their opinion remains in the minority not because their argument is invalid, but because:

1) We find it difficult to accept that the boundaries between psychiatric disorders are much fuzzier than what DSM-IV-TR suggests. We fear that doing so will cost us our hard-earned ostensive legitimacy as a medical discipline.

2) As most atypical antipsychotics are indicated for both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, one can justify use of any atypical for either disorder, even if the diagnosis is not entirely accurate.

Questioning the validity of a diagnostic construct (not a disease) should not be considered a “scientific transgression,” as Dr. Nasrallah puts it. After all, we still have not reached an international consensus on how long symptoms must be present before we diagnose schizophrenia (DSM-IV-TR says 6 months, ICD-10 says 1 month).

Jatinder P. Babbar, MD

Carilion University of Virginia

Roanoke Valley Program, University of Virginia

Salem, VA

Sample patient was clearly bipolar

Drs. Lake and Hurwitz’ sample patient’s symptoms were clearly consistent with bipolar illness, with evidence of catatonia more commonly seen in bipolar illness (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Many patients with schizophrenia, however, present with no evidence of current or past affective components. Dissecting such a case would have been more helpful. It is also unclear where the authors got their data regarding increased risk of suicide with neuroleptics.

Blindly diagnosing schizophrenia based on Bleuler’s and Kraepelin’s early 1900s descriptions is not the standard of care. We can thus remind ourselves that psychiatry is an evolving art and science, and that we have much to learn about the dynamics of behavior, mood, and thinking.

Danielle Skirchak, MD

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City

Drs. Lake and Hurwitz respond

Dr. Henry Nasrallah is correct that the “2 names, 1 disease” concept is polarizing (Commentary, Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Schizophrenia, conceived almost 100 years ago, has been so widely accepted and has accumulated such a “massive body of evidence” that we keep endorsing it without question.

Schizophrenia is defined by hallucinations, delusions, and a chronic, deteriorating course, but these supposedly disease-specific features readily occur in psychotic mood disorders.1,2 Classic bipolar patients can suffer chronic, deteriorating courses without remission, and severe psychotic symptoms can obscure mood symptoms.1,2 The idea that “interepisode phenomenology,” “chronic persistent psychosis,” and “between-episode interpersonal skills” differentiate schizophrenia from severe mood disorder is obsolete.1,2

More-recent phenotypic and genotypic similarities—and overlap from basic science, neuroradiologic, epidemiologic, and genetic studies—support the “one disease” hypothesis.3,4 Moreover, 8 of 11 susceptibility loci identified for schizophrenia and bipolar overlap.4

In his table, Dr. Nasrallah presents the traditional justifications for considering schizophrenia a separate disorder: that auditory hallucinations, negative symptoms, and the most bizarre delusions are “more common” in schizophrenia, and that paranoia is “more systematized.”

However, nearly all severely manic patients have these features as well as “disorganized and derailed thoughts.” All patients with severe depression have “negative symptoms” that can lack “affective cyclicity.” The “racing thoughts and flight of ideas,” specific to mania, actually derail and disorganize thoughts and behavior.

Continuing to consider schizophrenia a separate disease based on “a massive body of evidence,” and on certain symptoms being “more common” or “more severe” in schizophrenia than in bipolar disorder, puts psychiatry in the category of “art,” not science, and opens us for criticism from antipsychiatry groups such as the Scientologists.

The broad spectrum of symptoms and chronicity of course, initially unrecognized in psychotic mood, might account for differences in comparative studies. This spectrum likely encompasses other variances across mood disorders that have been cited as evidence for a separate disorder. Further, the longstanding tradition of separating bipolar disorder and schizophrenia may influence interpretation of comparative studies.

Concerning Dr. Skirchak’s remarks, psychotic major depressive disorder misdiagnosed as schizophrenia and treated only with neuroleptics explains “a risk of suicide with neuroleptics.” Also, continued use of neuroleptics in remitted, misdiagnosed manic patients can increase cycling, typically to a depressed episode.5

Regarding the queries of Drs. Green and Skirchak, our sample patient presented “without evident current or past mood symptoms.” No mood symptoms were obvious or elicited at presentation because attention focused on psychotic symptoms and not mood symptoms, leading to misdiagnosis and mistreatment. A temporary diagnosis of psychotic disorder NOS is appropriate in some cases while obscure mood and organic causes are explored.

Should the “one disease” concept prevail, Kraepelin would rest easily because his later concept was accurate; Bleuler—who could have renamed and promoted manic-depressive insanity instead of dementia praecox—and those invested in schizophrenia—clinicians, professors, researchers, grantees, editors, and some in the pharmaceutical industry—would incur discomfort.

C. Raymond Lake, MD, PhD

University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City

Nathaniel Hurwitz, MD

Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

1. Pope HG, Lipinski JF. Diagnosis in schizophrenia and manic-depressive illness, a reassessment of the specificity of “schizophrenic” symptoms in the light of current research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978;35:811-28.

2. Post RM. Transduction of psychosocial stress into the neurobiology of recurrent affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:999-1010.

3. Schulze TG, Ohlraun S, Czerski P, et al. Genotype-phenotype studies in bipolar disorder showing association between the DAOA/G30 locus and persecutory delusions: a first step toward a molecular genetic classification of psychiatric phenotypes. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:2101-8.

4. Fawcett J. What do we know for sure about bipolar disorder? Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1-2.

5. Zarate CA, Tohen M. Double-blind comparison of the continued use of antipsychotic treatment versus its discontinuation in remitted manic patients. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:169-71.

Drs. Lake and Hurwitz’ sample patient’s symptoms were clearly consistent with bipolar illness, with evidence of catatonia more commonly seen in bipolar illness (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Many patients with schizophrenia, however, present with no evidence of current or past affective components. Dissecting such a case would have been more helpful. It is also unclear where the authors got their data regarding increased risk of suicide with neuroleptics.

Blindly diagnosing schizophrenia based on Bleuler’s and Kraepelin’s early 1900s descriptions is not the standard of care. We can thus remind ourselves that psychiatry is an evolving art and science, and that we have much to learn about the dynamics of behavior, mood, and thinking.

Danielle Skirchak, MD

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City

Drs. Lake and Hurwitz respond

Dr. Henry Nasrallah is correct that the “2 names, 1 disease” concept is polarizing (Commentary, Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Schizophrenia, conceived almost 100 years ago, has been so widely accepted and has accumulated such a “massive body of evidence” that we keep endorsing it without question.

Schizophrenia is defined by hallucinations, delusions, and a chronic, deteriorating course, but these supposedly disease-specific features readily occur in psychotic mood disorders.1,2 Classic bipolar patients can suffer chronic, deteriorating courses without remission, and severe psychotic symptoms can obscure mood symptoms.1,2 The idea that “interepisode phenomenology,” “chronic persistent psychosis,” and “between-episode interpersonal skills” differentiate schizophrenia from severe mood disorder is obsolete.1,2

More-recent phenotypic and genotypic similarities—and overlap from basic science, neuroradiologic, epidemiologic, and genetic studies—support the “one disease” hypothesis.3,4 Moreover, 8 of 11 susceptibility loci identified for schizophrenia and bipolar overlap.4

In his table, Dr. Nasrallah presents the traditional justifications for considering schizophrenia a separate disorder: that auditory hallucinations, negative symptoms, and the most bizarre delusions are “more common” in schizophrenia, and that paranoia is “more systematized.”

However, nearly all severely manic patients have these features as well as “disorganized and derailed thoughts.” All patients with severe depression have “negative symptoms” that can lack “affective cyclicity.” The “racing thoughts and flight of ideas,” specific to mania, actually derail and disorganize thoughts and behavior.

Continuing to consider schizophrenia a separate disease based on “a massive body of evidence,” and on certain symptoms being “more common” or “more severe” in schizophrenia than in bipolar disorder, puts psychiatry in the category of “art,” not science, and opens us for criticism from antipsychiatry groups such as the Scientologists.

The broad spectrum of symptoms and chronicity of course, initially unrecognized in psychotic mood, might account for differences in comparative studies. This spectrum likely encompasses other variances across mood disorders that have been cited as evidence for a separate disorder. Further, the longstanding tradition of separating bipolar disorder and schizophrenia may influence interpretation of comparative studies.

Concerning Dr. Skirchak’s remarks, psychotic major depressive disorder misdiagnosed as schizophrenia and treated only with neuroleptics explains “a risk of suicide with neuroleptics.” Also, continued use of neuroleptics in remitted, misdiagnosed manic patients can increase cycling, typically to a depressed episode.5

Regarding the queries of Drs. Green and Skirchak, our sample patient presented “without evident current or past mood symptoms.” No mood symptoms were obvious or elicited at presentation because attention focused on psychotic symptoms and not mood symptoms, leading to misdiagnosis and mistreatment. A temporary diagnosis of psychotic disorder NOS is appropriate in some cases while obscure mood and organic causes are explored.

Should the “one disease” concept prevail, Kraepelin would rest easily because his later concept was accurate; Bleuler—who could have renamed and promoted manic-depressive insanity instead of dementia praecox—and those invested in schizophrenia—clinicians, professors, researchers, grantees, editors, and some in the pharmaceutical industry—would incur discomfort.

C. Raymond Lake, MD, PhD

University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City

Nathaniel Hurwitz, MD

Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

Drs. Lake and Hurwitz’ sample patient’s symptoms were clearly consistent with bipolar illness, with evidence of catatonia more commonly seen in bipolar illness (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Many patients with schizophrenia, however, present with no evidence of current or past affective components. Dissecting such a case would have been more helpful. It is also unclear where the authors got their data regarding increased risk of suicide with neuroleptics.

Blindly diagnosing schizophrenia based on Bleuler’s and Kraepelin’s early 1900s descriptions is not the standard of care. We can thus remind ourselves that psychiatry is an evolving art and science, and that we have much to learn about the dynamics of behavior, mood, and thinking.

Danielle Skirchak, MD

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences

University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City

Drs. Lake and Hurwitz respond

Dr. Henry Nasrallah is correct that the “2 names, 1 disease” concept is polarizing (Commentary, Current Psychiatry, March 2006). Schizophrenia, conceived almost 100 years ago, has been so widely accepted and has accumulated such a “massive body of evidence” that we keep endorsing it without question.

Schizophrenia is defined by hallucinations, delusions, and a chronic, deteriorating course, but these supposedly disease-specific features readily occur in psychotic mood disorders.1,2 Classic bipolar patients can suffer chronic, deteriorating courses without remission, and severe psychotic symptoms can obscure mood symptoms.1,2 The idea that “interepisode phenomenology,” “chronic persistent psychosis,” and “between-episode interpersonal skills” differentiate schizophrenia from severe mood disorder is obsolete.1,2

More-recent phenotypic and genotypic similarities—and overlap from basic science, neuroradiologic, epidemiologic, and genetic studies—support the “one disease” hypothesis.3,4 Moreover, 8 of 11 susceptibility loci identified for schizophrenia and bipolar overlap.4

In his table, Dr. Nasrallah presents the traditional justifications for considering schizophrenia a separate disorder: that auditory hallucinations, negative symptoms, and the most bizarre delusions are “more common” in schizophrenia, and that paranoia is “more systematized.”

However, nearly all severely manic patients have these features as well as “disorganized and derailed thoughts.” All patients with severe depression have “negative symptoms” that can lack “affective cyclicity.” The “racing thoughts and flight of ideas,” specific to mania, actually derail and disorganize thoughts and behavior.

Continuing to consider schizophrenia a separate disease based on “a massive body of evidence,” and on certain symptoms being “more common” or “more severe” in schizophrenia than in bipolar disorder, puts psychiatry in the category of “art,” not science, and opens us for criticism from antipsychiatry groups such as the Scientologists.

The broad spectrum of symptoms and chronicity of course, initially unrecognized in psychotic mood, might account for differences in comparative studies. This spectrum likely encompasses other variances across mood disorders that have been cited as evidence for a separate disorder. Further, the longstanding tradition of separating bipolar disorder and schizophrenia may influence interpretation of comparative studies.

Concerning Dr. Skirchak’s remarks, psychotic major depressive disorder misdiagnosed as schizophrenia and treated only with neuroleptics explains “a risk of suicide with neuroleptics.” Also, continued use of neuroleptics in remitted, misdiagnosed manic patients can increase cycling, typically to a depressed episode.5

Regarding the queries of Drs. Green and Skirchak, our sample patient presented “without evident current or past mood symptoms.” No mood symptoms were obvious or elicited at presentation because attention focused on psychotic symptoms and not mood symptoms, leading to misdiagnosis and mistreatment. A temporary diagnosis of psychotic disorder NOS is appropriate in some cases while obscure mood and organic causes are explored.

Should the “one disease” concept prevail, Kraepelin would rest easily because his later concept was accurate; Bleuler—who could have renamed and promoted manic-depressive insanity instead of dementia praecox—and those invested in schizophrenia—clinicians, professors, researchers, grantees, editors, and some in the pharmaceutical industry—would incur discomfort.

C. Raymond Lake, MD, PhD

University of Kansas School of Medicine, Kansas City

Nathaniel Hurwitz, MD

Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT

1. Pope HG, Lipinski JF. Diagnosis in schizophrenia and manic-depressive illness, a reassessment of the specificity of “schizophrenic” symptoms in the light of current research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978;35:811-28.

2. Post RM. Transduction of psychosocial stress into the neurobiology of recurrent affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:999-1010.

3. Schulze TG, Ohlraun S, Czerski P, et al. Genotype-phenotype studies in bipolar disorder showing association between the DAOA/G30 locus and persecutory delusions: a first step toward a molecular genetic classification of psychiatric phenotypes. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:2101-8.

4. Fawcett J. What do we know for sure about bipolar disorder? Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1-2.

5. Zarate CA, Tohen M. Double-blind comparison of the continued use of antipsychotic treatment versus its discontinuation in remitted manic patients. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:169-71.

1. Pope HG, Lipinski JF. Diagnosis in schizophrenia and manic-depressive illness, a reassessment of the specificity of “schizophrenic” symptoms in the light of current research. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1978;35:811-28.

2. Post RM. Transduction of psychosocial stress into the neurobiology of recurrent affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry 1992;149:999-1010.

3. Schulze TG, Ohlraun S, Czerski P, et al. Genotype-phenotype studies in bipolar disorder showing association between the DAOA/G30 locus and persecutory delusions: a first step toward a molecular genetic classification of psychiatric phenotypes. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:2101-8.

4. Fawcett J. What do we know for sure about bipolar disorder? Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1-2.

5. Zarate CA, Tohen M. Double-blind comparison of the continued use of antipsychotic treatment versus its discontinuation in remitted manic patients. Am J Psychiatry 2004;161:169-71.

Schizophrenia: no mood disorder

Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are two distinct disorders (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). True, many bipolar patients are misdiagnosed as having schizophrenia, and some patients have overlapping symptoms of both disorders. Many patients with schizophrenia, however, have chronic persistent psychosis and negative symptoms with no mood disorder.

Also, how can the authors say that misdiagnosing bipolar disorder as schizophrenia would unnecessarily expose patients to antipsychotics instead of needed mood stabilizers? Many atypical antipsychotics work as mood stabilizers, sometimes more effectively than lithium, divalproex, or other old standards. It sounded like the authors were turning back the clock to when many bipolar patients were misdiagnosed with schizophrenia and placed on long-term haloperidol or another conventional antipsychotic.

Anthony Green, MD

Aberdeen, NJ

Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are two distinct disorders (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). True, many bipolar patients are misdiagnosed as having schizophrenia, and some patients have overlapping symptoms of both disorders. Many patients with schizophrenia, however, have chronic persistent psychosis and negative symptoms with no mood disorder.

Also, how can the authors say that misdiagnosing bipolar disorder as schizophrenia would unnecessarily expose patients to antipsychotics instead of needed mood stabilizers? Many atypical antipsychotics work as mood stabilizers, sometimes more effectively than lithium, divalproex, or other old standards. It sounded like the authors were turning back the clock to when many bipolar patients were misdiagnosed with schizophrenia and placed on long-term haloperidol or another conventional antipsychotic.

Anthony Green, MD

Aberdeen, NJ

Bipolar disorder and schizophrenia are two distinct disorders (Current Psychiatry, March 2006). True, many bipolar patients are misdiagnosed as having schizophrenia, and some patients have overlapping symptoms of both disorders. Many patients with schizophrenia, however, have chronic persistent psychosis and negative symptoms with no mood disorder.

Also, how can the authors say that misdiagnosing bipolar disorder as schizophrenia would unnecessarily expose patients to antipsychotics instead of needed mood stabilizers? Many atypical antipsychotics work as mood stabilizers, sometimes more effectively than lithium, divalproex, or other old standards. It sounded like the authors were turning back the clock to when many bipolar patients were misdiagnosed with schizophrenia and placed on long-term haloperidol or another conventional antipsychotic.

Anthony Green, MD

Aberdeen, NJ

Bipolar disorder: One name doesn’t fit all

I commend Drs. Lake and Hurwitz for their out-of-the-box thinking about bipolar disorder (Current Psychiatry, March 2006), but their argument is the weakest I have seen in a scholarly article. One misdiagnosis does not prove that every patient labeled as schizophrenic has been misdiagnosed.

The authors describe Mr. C’s initial presentation but offer few details on his behavior and symptoms, saying only, “within 2 weeks, Mr. C. switches from depression to a mixed, dysphoric mania.” What does that mean? What signs and symptoms were present?

The only evidence the authors present to support their conclusion is Pope and Lipinski’s 1978 paper.1 Drs. Lake and Hurwitz barely address the controversy surrounding these findings, saying, “We concur…that psychotic bipolar disorder includes patient populations typically diagnosed as having schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder.”

Note that the authors did not write, “We believe that these findings indicate that patients who meet DSM-IV-TR criteria for schizophrenia really have a form of bipolar disorder.” This reversal is merely sleight of hand.

Worse, Drs. Lake and Hurwitz fail to note that a set of diagnostic labels and criteria such as DSM-IV-TR facilitates communication among clinicians and researchers. This way, when a new patient’s chart indicates a schizophrenia diagnosis, you know what to expect (psychotic symptoms, auditory hallucinations, downward spiral, etc.).

In practice, however, I have seen patients with nearly every psychiatric disorder who have been misdiagnosed with bipolar disorder, usually with little or no evidence of past hypomania or mania. One provider closed his clinic and referred his patients to me; each came with an (incorrect) bipolar disorder diagnosis.

I no longer know what to expect when I see a patient who has been labeled as “bipolar,” “manic,” or “mixed manic.” The diagnosis has been distorted to the point of clinical uselessness.

Lumping schizophrenia into this rubric would further cloud bipolar disorder diagnosis. Should we next lump in panic disorder? Social phobia? Vascular dementia? Cocaine dependence? While these suggestions are patently ridiculous, I have seen patients with each of these diagnoses labeled by another clinician as “bipolar.”

Maybe DSM-V should list a separate axis for mood dysfunction, which would fit the construct of a “bipolar spectrum.”