User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Understanding dreams: Tapping a rich resource

Dreams are a rich resource for understanding how the mind integrates waking experience into older memory networks. Any psychiatrist who doubts dreams’ therapeutic value has probably not attended closely to his or her own dreams or become aware of exciting new evidence.

Recent understandings of how memory is processed during sleep are bringing dreams back into clinical importance. Patients can gather clinically useful data while sleeping—not in laboratories but in their own beds. Detecting and interpreting patterns in that data can help you treat patients not responding adequately to other therapies.

CHARTING DREAM SEQUENCES

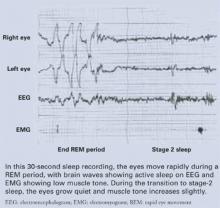

The rate at which the eyes move during rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep (Figure) has been associated with memory consolidation. Eye movements increase during REM sleep, and waking performance improves after intensive learning periods. When eye movements are sparse, patients report dreams with less visual imagery and blander emotional content.1

Though all sleep stages contribute to learning and memory, REM sleep appears to allow wider, easier access to memories2 than does slow-wave sleep or waking. In other words, dreams are far from meaningless. They constitute a continuing mental operation that allows us to modify memory networks of emotional importance to us.

Dreams’ emotional tone tends to shift from negative to positive as the night goes on:3

- Dream-to-dream down-regulation of negative feelings is seen when a person’s waking concerns are strong but not overwhelming.

- Conversely, a dream sequence may show no progress within the night4—and the last dream may be as negative as the first—if the person has reached a point of resignation while awake.

This “sequential hypothesis”5 holds that knowledge of dreams as they occur—one after the other within the night—is a valuable resource for observing how a person is relating waking experience to the past. Dreams thus can give the therapist a “heads up” about a patient’s progress in organizing troublesome feelings.

Figure REM sleep: Dreaming’s prime time

CASE EXAMPLE: NIGHTMARES FOR 13 YEARS

Ms. R, a newlywed at age 30, presents for help with repetitive nightmares that prevent her from sharing a bed with her husband. She was raped at age 17 and has suffered nightmares since then. Once or more nightly she dreams of being attacked and awakens in terror, with profuse sweating. She usually has to change her nightclothes and sometimes the sheets.

Her therapist gives Ms. R four rules—the RISC method6—for shifting her dreams from negative to positive:

- Recognize that the dream is not going well.

- Identify what about it is frightening.

- Stop the dream, even if she must force her eyes open.

- Change the action to something positive.

At the third therapy session, Ms. R reports she had a successful dream. She was lying on her back on an open elevator platform. The elevator was rising dangerously high over the cityscape. She realized she was afraid and got up to see what was happening. As she arose, the elevator walls rose up to protect her. The patient says she learned if she “stands up for herself” all would be well.

After two more sessions with successful practice of this skill, she terminates therapy. When called 1 year later, she says she is expecting a child and has only an occasional nightmare, which she feels she can handle.

CLINICAL USES OF DREAM THERAPY

Dream interpretation may help us understand emotional programs that underlie patients’ unsatisfactory waking behavior. For example:

- Victims of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as Ms. R may suffer repetitive nightmares with recurrent themes and excessive negative feelings. We can encourage them to shift their dream scripts from negative to positive.7

- Uninsightful, alexythymic patients, who often leave treatment before deriving any benefit, may learn to understand themselves by becoming aware of their dreams.8

- Severely depressed patientsoften have limited dream recall during sleep studies—even when every REM period is interrupted. They may be taught to improve their dream recall.9

Rules for improving dream recall are few, simple, and effective when the sleeper is motivated to remember them (Box). Just as one can learn to awaken before the morning alarm clock goes off, patients can learn to awaken to recall a dream.

After you have enough of a patient’s dreams to work from—20 is a good start—look for repeated dimensions that are the dreams’ building blocks.5 Look for polar opposites—such as safe-at risk, foolish-clever, exposed-hidden, strong-weak, attractive-ugly—that describe major characteristics of the self figure. Each has a positive or negative emotional value that can be explored.

Go to sleep intending to remember a dream as you awaken.

Sleep until you wake up naturally.* Spontaneous awakening is likely to be from REM sleep, which is dominant in the last third of the night.

Once awake, lie perfectly still. Do not jump up or open your eyes. This preserves a REM-like state when attention is focused inward, not on outside stimuli, and motor tone is profoundly reduced.

Rehearse the recalled images, and give the theme a title (“I left my briefcase on the train” or “My husband returned from a trip unexpectedly”), which makes dream details easier to recall.

Write or tape record all that you can remember, noting the date and time of the report.

Add a note about anything the dream brings to mind about your thoughts before sleep.

* To allow spontaneous awakening, practice dream recall when you do not have to wake up to an alarm clock, such as on weekends.

WHAT TURNED US OFF ABOUT DREAMS

Prolonged therapy. Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams 10 was a major influence on how therapists used dreams to understand their patients in the early 20th century. Freud concluded that dreams —however strange—represent hallucinated fulfillment of repressed early wishes and tie up psychic energy to conceal unacceptable desires.

From this point of view, dreams provide a road map to understand persistent, nonrational, sometimes self-defeating behaviors that bring patients to therapy. The map, however, was more maze than speedway, full of detours and requiring much time to navigate the boulevards of associations that lead from one dream element to the next. Erik Erickson11 suggested that dreams fell into disuse as therapeutic tools in the 1930s because psychoanalysis in general—and dream interpretation in particular—did not fit the American value of “the faster the better.”

In retrospect, the unconscious mind’s defenses may not have been what prolonged efforts to understand dream meaning. Rather, it may have been that the analyst had to work from whatever scraps the patient could remember of past dreams, to say nothing of new ones that occurred since the last appointment. That one dream could occupy many treatment hours did not trouble the Freudians, however, as—they argued—any-thing the patient does remember is proof of its importance.

Sleep research dealt the worst blow to the pursuit of dreams’ meaning and function.12,13 Contrary to Freud’s view, dreams are not elusive if caught in the act. They can be reliably retrieved from REM episodes, which occur three to five times nightly with great regularity.

After REM sleep was found to initiate from the “unthinking pons,” dreams were proclaimed to have no inherent meaning worthy of serious effort. At best, they were explained as the result of random stimuli producing images to which we add meaning as we awaken. Thus, they offer no unique contribution to understanding psychic life. This “activation-synthesis” hypothesis14 wiped out dream research funding.

Medications. The pharmacologic revolution allowed more-rapid relief of anxiety and depression symptoms than did dream interpretation. Clinicians may feel that “we can forget about dreams because we now have better options.” This ignores research showing that psychiatric medication plus psychotherapy is more effective for a longer time than either alone.15

Evidence-based medicine. Dream content is inherently subjective and not open to objective observation, the heart of scientific methods. Only the dreamer can say what was dreamed.

WHAT BROUGHT DREAMS BACK

Better methods and more-sophisticated models renewed dream interpretation as a useful adjunct to other psychotherapies. In addition to research in memory processing, imaging methods and neuropsychological testing have changed our understanding of brain activity during sleep.

Brain imaging. Early sleep study was limited to recordings from the scalp surface. Now positron emission tomography and functional magnetic imagery allow researchers to see changes in brain activity and to study patterns during waking, non-REM sleep, and REM sleep and among clinical groups. Nofzinger et al,16 for example, showed differences in areas of high and low brain activation in persons with major depression, compared with normal controls.

Neuropsychological testing. Solms2 used neuropsychological testing and interviewing to identify waking cognitive deficits and changes in dream experience in persons with brain damage from surgery or accident. Contrary to the “activation-synthesis” model, he concluded that dreams “are both generated and represented by some of the highest mental mechanisms.” He also argued that although dreams often coincide with the REM state, they also occur beyond REM.

COMING SOON: AT-HOME SLEEP MONITORS

In a sleep laboratory, awakening sleepers during REM periods and asking them to tell what they remember is the classic method for examining the relation among a night’s dreams.17-19 This cumbersome and expensive procedure is being simplified for home use.

Computer-linked monitors are being developed that awaken the sleeper after a pre-set number of rapid eye movements and start a tape recorder to which the person can tell his or her dream. This system, which preserves the dream story from memory loss or distortion,20,21 can easily record three or four dreams each night.

Translating this sensory data into verbal reports remains difficult. Although repeated elements give clues to dream structure, a repeated theme within a night might be an artifact induced by waking the sleeper to ask for a report. If a sleeper reports dreaming about being in an accident, for example, he may be influenced to continue that line of thought as he is falling back to sleep. This, in turn, may influence the next dream.

What else can we do? Because dream recall is ephemeral at best, patients may need training before a therapist has a sample large enough to extract repeating elements and be confident of its reliability.

Related resources

- Schneider A, Domhoff GW. Psychology department, University of California, Santa Cruz. Web site for collecting dream reports. www.DreamBank.net.

- American Psychological Association. Dreaming. Quarterly multidisciplinary journal. www.apa.org/journals/drm/.

Disclosures

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pivik R. Tonic states and phasic events in relation to sleep mentation. In: Ellman S, Antrobus J (eds). The mind in sleep. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1991;214-47.

2. Solms M. The neuropsychology of dreams. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997.

3. Cartwright R, Luten A, Young M, et al. Role of REM sleep and dream affect in overnight mood regulation: a study of normals. Psychiatry Res 1998a;81:1-8.

4. Cartwright R, Young M, Mercer P, Bears M. Role of REM sleep and dream variables in the prediction of remission from depression. Psychiatry Res 1998b;80:249-55.

5. Giuditta A, Mandile P, Montagnese P, et al. The role of sleep in memory processing: the sequential hypothesis. In: Maquet P, Smith C, Stickgold R (eds). Sleep and brain plasticity. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003.

6. Cartwright R, Lamberg L. Crisis dreaming. New York: Harper Collins; 1993;42-51.

7. Armitage R, Rochlen A, Fitch T, et al. Dream recall and major depression: a preliminary report. Dreaming 1995;5:189-98.

8. Cartwright R, Tipton L, Wicklund J. Focusing on dreams: a preparation program for psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980;37:275-7.

9. Riemann D, Wiegand M, Majer-Trendal K, et al. Dream recall and dream content in depressive patients, patients with anorexia nervosa and normal controls. In: Koella W, Obal F, Schulz H, Viss P (eds). Sleep ’86. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer; 1988;373-6.

10. Freud S. The interpretation of dreams. New York: Basic Books; 1955.

11. Erickson E. The dream specimen in psychoanalysis. In: Knight R, Friedman C (eds). Psychoanalytic psychiatry and psychology. New York: International Press; 1954.

12. Aserinsky E, Kleitman N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility and concomitant phenomena during sleep. Science 1953;118:273.-

13. Dement W, Kleitman N. Relation of eye movements during sleep to dream activity: objective method for the study of dreaming. J Exper Psychol 1957;53:339-46.

14. Hobson JA, McCarley R. The brain as a dream state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. Am J Psychiatry 1977;134:1335-48.

15. Weissman M, Klerman G, Prusoff B, et al. Depressed outpatients one year after treatment with drugs and/or interpersonal psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:51-5.

16. Nofzinger E, Buysse D, Germain A, et al. Increased activation of anterior paralimbic and executive cortex from waking to rapid eye movement sleep in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:695-702.

17. Rechtschaffen A, Vogel G, Shaikun G. Interrelatedness of mental activity during sleep. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1963;9:536-47.

18. Verdone P. Temporal reference of manifest dream content. Percept Motor Skills 1965;20:1253.-

18. Cartwright R. Night life: explorations in dreaming. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977;18-31.

20. Mamelak A, Hobson JA. Nightcap: a home-based sleep monitoring system. Sleep 1989;12:157-66.

21. Lloyd S, Cartwright R. The collection of home and laboratory dreams by means of an instrumental response technique. Dreaming 1995;5:63-73.

Dreams are a rich resource for understanding how the mind integrates waking experience into older memory networks. Any psychiatrist who doubts dreams’ therapeutic value has probably not attended closely to his or her own dreams or become aware of exciting new evidence.

Recent understandings of how memory is processed during sleep are bringing dreams back into clinical importance. Patients can gather clinically useful data while sleeping—not in laboratories but in their own beds. Detecting and interpreting patterns in that data can help you treat patients not responding adequately to other therapies.

CHARTING DREAM SEQUENCES

The rate at which the eyes move during rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep (Figure) has been associated with memory consolidation. Eye movements increase during REM sleep, and waking performance improves after intensive learning periods. When eye movements are sparse, patients report dreams with less visual imagery and blander emotional content.1

Though all sleep stages contribute to learning and memory, REM sleep appears to allow wider, easier access to memories2 than does slow-wave sleep or waking. In other words, dreams are far from meaningless. They constitute a continuing mental operation that allows us to modify memory networks of emotional importance to us.

Dreams’ emotional tone tends to shift from negative to positive as the night goes on:3

- Dream-to-dream down-regulation of negative feelings is seen when a person’s waking concerns are strong but not overwhelming.

- Conversely, a dream sequence may show no progress within the night4—and the last dream may be as negative as the first—if the person has reached a point of resignation while awake.

This “sequential hypothesis”5 holds that knowledge of dreams as they occur—one after the other within the night—is a valuable resource for observing how a person is relating waking experience to the past. Dreams thus can give the therapist a “heads up” about a patient’s progress in organizing troublesome feelings.

Figure REM sleep: Dreaming’s prime time

CASE EXAMPLE: NIGHTMARES FOR 13 YEARS

Ms. R, a newlywed at age 30, presents for help with repetitive nightmares that prevent her from sharing a bed with her husband. She was raped at age 17 and has suffered nightmares since then. Once or more nightly she dreams of being attacked and awakens in terror, with profuse sweating. She usually has to change her nightclothes and sometimes the sheets.

Her therapist gives Ms. R four rules—the RISC method6—for shifting her dreams from negative to positive:

- Recognize that the dream is not going well.

- Identify what about it is frightening.

- Stop the dream, even if she must force her eyes open.

- Change the action to something positive.

At the third therapy session, Ms. R reports she had a successful dream. She was lying on her back on an open elevator platform. The elevator was rising dangerously high over the cityscape. She realized she was afraid and got up to see what was happening. As she arose, the elevator walls rose up to protect her. The patient says she learned if she “stands up for herself” all would be well.

After two more sessions with successful practice of this skill, she terminates therapy. When called 1 year later, she says she is expecting a child and has only an occasional nightmare, which she feels she can handle.

CLINICAL USES OF DREAM THERAPY

Dream interpretation may help us understand emotional programs that underlie patients’ unsatisfactory waking behavior. For example:

- Victims of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as Ms. R may suffer repetitive nightmares with recurrent themes and excessive negative feelings. We can encourage them to shift their dream scripts from negative to positive.7

- Uninsightful, alexythymic patients, who often leave treatment before deriving any benefit, may learn to understand themselves by becoming aware of their dreams.8

- Severely depressed patientsoften have limited dream recall during sleep studies—even when every REM period is interrupted. They may be taught to improve their dream recall.9

Rules for improving dream recall are few, simple, and effective when the sleeper is motivated to remember them (Box). Just as one can learn to awaken before the morning alarm clock goes off, patients can learn to awaken to recall a dream.

After you have enough of a patient’s dreams to work from—20 is a good start—look for repeated dimensions that are the dreams’ building blocks.5 Look for polar opposites—such as safe-at risk, foolish-clever, exposed-hidden, strong-weak, attractive-ugly—that describe major characteristics of the self figure. Each has a positive or negative emotional value that can be explored.

Go to sleep intending to remember a dream as you awaken.

Sleep until you wake up naturally.* Spontaneous awakening is likely to be from REM sleep, which is dominant in the last third of the night.

Once awake, lie perfectly still. Do not jump up or open your eyes. This preserves a REM-like state when attention is focused inward, not on outside stimuli, and motor tone is profoundly reduced.

Rehearse the recalled images, and give the theme a title (“I left my briefcase on the train” or “My husband returned from a trip unexpectedly”), which makes dream details easier to recall.

Write or tape record all that you can remember, noting the date and time of the report.

Add a note about anything the dream brings to mind about your thoughts before sleep.

* To allow spontaneous awakening, practice dream recall when you do not have to wake up to an alarm clock, such as on weekends.

WHAT TURNED US OFF ABOUT DREAMS

Prolonged therapy. Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams 10 was a major influence on how therapists used dreams to understand their patients in the early 20th century. Freud concluded that dreams —however strange—represent hallucinated fulfillment of repressed early wishes and tie up psychic energy to conceal unacceptable desires.

From this point of view, dreams provide a road map to understand persistent, nonrational, sometimes self-defeating behaviors that bring patients to therapy. The map, however, was more maze than speedway, full of detours and requiring much time to navigate the boulevards of associations that lead from one dream element to the next. Erik Erickson11 suggested that dreams fell into disuse as therapeutic tools in the 1930s because psychoanalysis in general—and dream interpretation in particular—did not fit the American value of “the faster the better.”

In retrospect, the unconscious mind’s defenses may not have been what prolonged efforts to understand dream meaning. Rather, it may have been that the analyst had to work from whatever scraps the patient could remember of past dreams, to say nothing of new ones that occurred since the last appointment. That one dream could occupy many treatment hours did not trouble the Freudians, however, as—they argued—any-thing the patient does remember is proof of its importance.

Sleep research dealt the worst blow to the pursuit of dreams’ meaning and function.12,13 Contrary to Freud’s view, dreams are not elusive if caught in the act. They can be reliably retrieved from REM episodes, which occur three to five times nightly with great regularity.

After REM sleep was found to initiate from the “unthinking pons,” dreams were proclaimed to have no inherent meaning worthy of serious effort. At best, they were explained as the result of random stimuli producing images to which we add meaning as we awaken. Thus, they offer no unique contribution to understanding psychic life. This “activation-synthesis” hypothesis14 wiped out dream research funding.

Medications. The pharmacologic revolution allowed more-rapid relief of anxiety and depression symptoms than did dream interpretation. Clinicians may feel that “we can forget about dreams because we now have better options.” This ignores research showing that psychiatric medication plus psychotherapy is more effective for a longer time than either alone.15

Evidence-based medicine. Dream content is inherently subjective and not open to objective observation, the heart of scientific methods. Only the dreamer can say what was dreamed.

WHAT BROUGHT DREAMS BACK

Better methods and more-sophisticated models renewed dream interpretation as a useful adjunct to other psychotherapies. In addition to research in memory processing, imaging methods and neuropsychological testing have changed our understanding of brain activity during sleep.

Brain imaging. Early sleep study was limited to recordings from the scalp surface. Now positron emission tomography and functional magnetic imagery allow researchers to see changes in brain activity and to study patterns during waking, non-REM sleep, and REM sleep and among clinical groups. Nofzinger et al,16 for example, showed differences in areas of high and low brain activation in persons with major depression, compared with normal controls.

Neuropsychological testing. Solms2 used neuropsychological testing and interviewing to identify waking cognitive deficits and changes in dream experience in persons with brain damage from surgery or accident. Contrary to the “activation-synthesis” model, he concluded that dreams “are both generated and represented by some of the highest mental mechanisms.” He also argued that although dreams often coincide with the REM state, they also occur beyond REM.

COMING SOON: AT-HOME SLEEP MONITORS

In a sleep laboratory, awakening sleepers during REM periods and asking them to tell what they remember is the classic method for examining the relation among a night’s dreams.17-19 This cumbersome and expensive procedure is being simplified for home use.

Computer-linked monitors are being developed that awaken the sleeper after a pre-set number of rapid eye movements and start a tape recorder to which the person can tell his or her dream. This system, which preserves the dream story from memory loss or distortion,20,21 can easily record three or four dreams each night.

Translating this sensory data into verbal reports remains difficult. Although repeated elements give clues to dream structure, a repeated theme within a night might be an artifact induced by waking the sleeper to ask for a report. If a sleeper reports dreaming about being in an accident, for example, he may be influenced to continue that line of thought as he is falling back to sleep. This, in turn, may influence the next dream.

What else can we do? Because dream recall is ephemeral at best, patients may need training before a therapist has a sample large enough to extract repeating elements and be confident of its reliability.

Related resources

- Schneider A, Domhoff GW. Psychology department, University of California, Santa Cruz. Web site for collecting dream reports. www.DreamBank.net.

- American Psychological Association. Dreaming. Quarterly multidisciplinary journal. www.apa.org/journals/drm/.

Disclosures

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Dreams are a rich resource for understanding how the mind integrates waking experience into older memory networks. Any psychiatrist who doubts dreams’ therapeutic value has probably not attended closely to his or her own dreams or become aware of exciting new evidence.

Recent understandings of how memory is processed during sleep are bringing dreams back into clinical importance. Patients can gather clinically useful data while sleeping—not in laboratories but in their own beds. Detecting and interpreting patterns in that data can help you treat patients not responding adequately to other therapies.

CHARTING DREAM SEQUENCES

The rate at which the eyes move during rapid-eye movement (REM) sleep (Figure) has been associated with memory consolidation. Eye movements increase during REM sleep, and waking performance improves after intensive learning periods. When eye movements are sparse, patients report dreams with less visual imagery and blander emotional content.1

Though all sleep stages contribute to learning and memory, REM sleep appears to allow wider, easier access to memories2 than does slow-wave sleep or waking. In other words, dreams are far from meaningless. They constitute a continuing mental operation that allows us to modify memory networks of emotional importance to us.

Dreams’ emotional tone tends to shift from negative to positive as the night goes on:3

- Dream-to-dream down-regulation of negative feelings is seen when a person’s waking concerns are strong but not overwhelming.

- Conversely, a dream sequence may show no progress within the night4—and the last dream may be as negative as the first—if the person has reached a point of resignation while awake.

This “sequential hypothesis”5 holds that knowledge of dreams as they occur—one after the other within the night—is a valuable resource for observing how a person is relating waking experience to the past. Dreams thus can give the therapist a “heads up” about a patient’s progress in organizing troublesome feelings.

Figure REM sleep: Dreaming’s prime time

CASE EXAMPLE: NIGHTMARES FOR 13 YEARS

Ms. R, a newlywed at age 30, presents for help with repetitive nightmares that prevent her from sharing a bed with her husband. She was raped at age 17 and has suffered nightmares since then. Once or more nightly she dreams of being attacked and awakens in terror, with profuse sweating. She usually has to change her nightclothes and sometimes the sheets.

Her therapist gives Ms. R four rules—the RISC method6—for shifting her dreams from negative to positive:

- Recognize that the dream is not going well.

- Identify what about it is frightening.

- Stop the dream, even if she must force her eyes open.

- Change the action to something positive.

At the third therapy session, Ms. R reports she had a successful dream. She was lying on her back on an open elevator platform. The elevator was rising dangerously high over the cityscape. She realized she was afraid and got up to see what was happening. As she arose, the elevator walls rose up to protect her. The patient says she learned if she “stands up for herself” all would be well.

After two more sessions with successful practice of this skill, she terminates therapy. When called 1 year later, she says she is expecting a child and has only an occasional nightmare, which she feels she can handle.

CLINICAL USES OF DREAM THERAPY

Dream interpretation may help us understand emotional programs that underlie patients’ unsatisfactory waking behavior. For example:

- Victims of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) such as Ms. R may suffer repetitive nightmares with recurrent themes and excessive negative feelings. We can encourage them to shift their dream scripts from negative to positive.7

- Uninsightful, alexythymic patients, who often leave treatment before deriving any benefit, may learn to understand themselves by becoming aware of their dreams.8

- Severely depressed patientsoften have limited dream recall during sleep studies—even when every REM period is interrupted. They may be taught to improve their dream recall.9

Rules for improving dream recall are few, simple, and effective when the sleeper is motivated to remember them (Box). Just as one can learn to awaken before the morning alarm clock goes off, patients can learn to awaken to recall a dream.

After you have enough of a patient’s dreams to work from—20 is a good start—look for repeated dimensions that are the dreams’ building blocks.5 Look for polar opposites—such as safe-at risk, foolish-clever, exposed-hidden, strong-weak, attractive-ugly—that describe major characteristics of the self figure. Each has a positive or negative emotional value that can be explored.

Go to sleep intending to remember a dream as you awaken.

Sleep until you wake up naturally.* Spontaneous awakening is likely to be from REM sleep, which is dominant in the last third of the night.

Once awake, lie perfectly still. Do not jump up or open your eyes. This preserves a REM-like state when attention is focused inward, not on outside stimuli, and motor tone is profoundly reduced.

Rehearse the recalled images, and give the theme a title (“I left my briefcase on the train” or “My husband returned from a trip unexpectedly”), which makes dream details easier to recall.

Write or tape record all that you can remember, noting the date and time of the report.

Add a note about anything the dream brings to mind about your thoughts before sleep.

* To allow spontaneous awakening, practice dream recall when you do not have to wake up to an alarm clock, such as on weekends.

WHAT TURNED US OFF ABOUT DREAMS

Prolonged therapy. Freud’s The Interpretation of Dreams 10 was a major influence on how therapists used dreams to understand their patients in the early 20th century. Freud concluded that dreams —however strange—represent hallucinated fulfillment of repressed early wishes and tie up psychic energy to conceal unacceptable desires.

From this point of view, dreams provide a road map to understand persistent, nonrational, sometimes self-defeating behaviors that bring patients to therapy. The map, however, was more maze than speedway, full of detours and requiring much time to navigate the boulevards of associations that lead from one dream element to the next. Erik Erickson11 suggested that dreams fell into disuse as therapeutic tools in the 1930s because psychoanalysis in general—and dream interpretation in particular—did not fit the American value of “the faster the better.”

In retrospect, the unconscious mind’s defenses may not have been what prolonged efforts to understand dream meaning. Rather, it may have been that the analyst had to work from whatever scraps the patient could remember of past dreams, to say nothing of new ones that occurred since the last appointment. That one dream could occupy many treatment hours did not trouble the Freudians, however, as—they argued—any-thing the patient does remember is proof of its importance.

Sleep research dealt the worst blow to the pursuit of dreams’ meaning and function.12,13 Contrary to Freud’s view, dreams are not elusive if caught in the act. They can be reliably retrieved from REM episodes, which occur three to five times nightly with great regularity.

After REM sleep was found to initiate from the “unthinking pons,” dreams were proclaimed to have no inherent meaning worthy of serious effort. At best, they were explained as the result of random stimuli producing images to which we add meaning as we awaken. Thus, they offer no unique contribution to understanding psychic life. This “activation-synthesis” hypothesis14 wiped out dream research funding.

Medications. The pharmacologic revolution allowed more-rapid relief of anxiety and depression symptoms than did dream interpretation. Clinicians may feel that “we can forget about dreams because we now have better options.” This ignores research showing that psychiatric medication plus psychotherapy is more effective for a longer time than either alone.15

Evidence-based medicine. Dream content is inherently subjective and not open to objective observation, the heart of scientific methods. Only the dreamer can say what was dreamed.

WHAT BROUGHT DREAMS BACK

Better methods and more-sophisticated models renewed dream interpretation as a useful adjunct to other psychotherapies. In addition to research in memory processing, imaging methods and neuropsychological testing have changed our understanding of brain activity during sleep.

Brain imaging. Early sleep study was limited to recordings from the scalp surface. Now positron emission tomography and functional magnetic imagery allow researchers to see changes in brain activity and to study patterns during waking, non-REM sleep, and REM sleep and among clinical groups. Nofzinger et al,16 for example, showed differences in areas of high and low brain activation in persons with major depression, compared with normal controls.

Neuropsychological testing. Solms2 used neuropsychological testing and interviewing to identify waking cognitive deficits and changes in dream experience in persons with brain damage from surgery or accident. Contrary to the “activation-synthesis” model, he concluded that dreams “are both generated and represented by some of the highest mental mechanisms.” He also argued that although dreams often coincide with the REM state, they also occur beyond REM.

COMING SOON: AT-HOME SLEEP MONITORS

In a sleep laboratory, awakening sleepers during REM periods and asking them to tell what they remember is the classic method for examining the relation among a night’s dreams.17-19 This cumbersome and expensive procedure is being simplified for home use.

Computer-linked monitors are being developed that awaken the sleeper after a pre-set number of rapid eye movements and start a tape recorder to which the person can tell his or her dream. This system, which preserves the dream story from memory loss or distortion,20,21 can easily record three or four dreams each night.

Translating this sensory data into verbal reports remains difficult. Although repeated elements give clues to dream structure, a repeated theme within a night might be an artifact induced by waking the sleeper to ask for a report. If a sleeper reports dreaming about being in an accident, for example, he may be influenced to continue that line of thought as he is falling back to sleep. This, in turn, may influence the next dream.

What else can we do? Because dream recall is ephemeral at best, patients may need training before a therapist has a sample large enough to extract repeating elements and be confident of its reliability.

Related resources

- Schneider A, Domhoff GW. Psychology department, University of California, Santa Cruz. Web site for collecting dream reports. www.DreamBank.net.

- American Psychological Association. Dreaming. Quarterly multidisciplinary journal. www.apa.org/journals/drm/.

Disclosures

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Pivik R. Tonic states and phasic events in relation to sleep mentation. In: Ellman S, Antrobus J (eds). The mind in sleep. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1991;214-47.

2. Solms M. The neuropsychology of dreams. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997.

3. Cartwright R, Luten A, Young M, et al. Role of REM sleep and dream affect in overnight mood regulation: a study of normals. Psychiatry Res 1998a;81:1-8.

4. Cartwright R, Young M, Mercer P, Bears M. Role of REM sleep and dream variables in the prediction of remission from depression. Psychiatry Res 1998b;80:249-55.

5. Giuditta A, Mandile P, Montagnese P, et al. The role of sleep in memory processing: the sequential hypothesis. In: Maquet P, Smith C, Stickgold R (eds). Sleep and brain plasticity. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003.

6. Cartwright R, Lamberg L. Crisis dreaming. New York: Harper Collins; 1993;42-51.

7. Armitage R, Rochlen A, Fitch T, et al. Dream recall and major depression: a preliminary report. Dreaming 1995;5:189-98.

8. Cartwright R, Tipton L, Wicklund J. Focusing on dreams: a preparation program for psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980;37:275-7.

9. Riemann D, Wiegand M, Majer-Trendal K, et al. Dream recall and dream content in depressive patients, patients with anorexia nervosa and normal controls. In: Koella W, Obal F, Schulz H, Viss P (eds). Sleep ’86. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer; 1988;373-6.

10. Freud S. The interpretation of dreams. New York: Basic Books; 1955.

11. Erickson E. The dream specimen in psychoanalysis. In: Knight R, Friedman C (eds). Psychoanalytic psychiatry and psychology. New York: International Press; 1954.

12. Aserinsky E, Kleitman N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility and concomitant phenomena during sleep. Science 1953;118:273.-

13. Dement W, Kleitman N. Relation of eye movements during sleep to dream activity: objective method for the study of dreaming. J Exper Psychol 1957;53:339-46.

14. Hobson JA, McCarley R. The brain as a dream state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. Am J Psychiatry 1977;134:1335-48.

15. Weissman M, Klerman G, Prusoff B, et al. Depressed outpatients one year after treatment with drugs and/or interpersonal psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:51-5.

16. Nofzinger E, Buysse D, Germain A, et al. Increased activation of anterior paralimbic and executive cortex from waking to rapid eye movement sleep in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:695-702.

17. Rechtschaffen A, Vogel G, Shaikun G. Interrelatedness of mental activity during sleep. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1963;9:536-47.

18. Verdone P. Temporal reference of manifest dream content. Percept Motor Skills 1965;20:1253.-

18. Cartwright R. Night life: explorations in dreaming. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977;18-31.

20. Mamelak A, Hobson JA. Nightcap: a home-based sleep monitoring system. Sleep 1989;12:157-66.

21. Lloyd S, Cartwright R. The collection of home and laboratory dreams by means of an instrumental response technique. Dreaming 1995;5:63-73.

1. Pivik R. Tonic states and phasic events in relation to sleep mentation. In: Ellman S, Antrobus J (eds). The mind in sleep. New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1991;214-47.

2. Solms M. The neuropsychology of dreams. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1997.

3. Cartwright R, Luten A, Young M, et al. Role of REM sleep and dream affect in overnight mood regulation: a study of normals. Psychiatry Res 1998a;81:1-8.

4. Cartwright R, Young M, Mercer P, Bears M. Role of REM sleep and dream variables in the prediction of remission from depression. Psychiatry Res 1998b;80:249-55.

5. Giuditta A, Mandile P, Montagnese P, et al. The role of sleep in memory processing: the sequential hypothesis. In: Maquet P, Smith C, Stickgold R (eds). Sleep and brain plasticity. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2003.

6. Cartwright R, Lamberg L. Crisis dreaming. New York: Harper Collins; 1993;42-51.

7. Armitage R, Rochlen A, Fitch T, et al. Dream recall and major depression: a preliminary report. Dreaming 1995;5:189-98.

8. Cartwright R, Tipton L, Wicklund J. Focusing on dreams: a preparation program for psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1980;37:275-7.

9. Riemann D, Wiegand M, Majer-Trendal K, et al. Dream recall and dream content in depressive patients, patients with anorexia nervosa and normal controls. In: Koella W, Obal F, Schulz H, Viss P (eds). Sleep ’86. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer; 1988;373-6.

10. Freud S. The interpretation of dreams. New York: Basic Books; 1955.

11. Erickson E. The dream specimen in psychoanalysis. In: Knight R, Friedman C (eds). Psychoanalytic psychiatry and psychology. New York: International Press; 1954.

12. Aserinsky E, Kleitman N. Regularly occurring periods of eye motility and concomitant phenomena during sleep. Science 1953;118:273.-

13. Dement W, Kleitman N. Relation of eye movements during sleep to dream activity: objective method for the study of dreaming. J Exper Psychol 1957;53:339-46.

14. Hobson JA, McCarley R. The brain as a dream state generator: An activation-synthesis hypothesis of the dream process. Am J Psychiatry 1977;134:1335-48.

15. Weissman M, Klerman G, Prusoff B, et al. Depressed outpatients one year after treatment with drugs and/or interpersonal psychotherapy. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:51-5.

16. Nofzinger E, Buysse D, Germain A, et al. Increased activation of anterior paralimbic and executive cortex from waking to rapid eye movement sleep in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2004;61:695-702.

17. Rechtschaffen A, Vogel G, Shaikun G. Interrelatedness of mental activity during sleep. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1963;9:536-47.

18. Verdone P. Temporal reference of manifest dream content. Percept Motor Skills 1965;20:1253.-

18. Cartwright R. Night life: explorations in dreaming. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1977;18-31.

20. Mamelak A, Hobson JA. Nightcap: a home-based sleep monitoring system. Sleep 1989;12:157-66.

21. Lloyd S, Cartwright R. The collection of home and laboratory dreams by means of an instrumental response technique. Dreaming 1995;5:63-73.

When treatment spells trouble

HISTORY: ‘THEY’RE TRYING TO KILL ME’

For the past 7 months Ms. G, age 47, has had worsening paranoid thoughts and sleep disturbances. She sleeps 4 hours or less a night, and her appetite and energy are diminished.

Her mother reports that Ms. G, who lives in an extended-care facility, believes the staff has injected embalming fluid into her body and is plotting to kill her. She says her daughter also has “fits” during which she hears a deafening noise that sounds like a vacuum cleaner, followed by a feeling of being pushed to the ground. Ms. G tells us that someone or something invisible is trying to control her.

Ms. G was diagnosed 2 years ago as having Parkinson’s disease and has chronically high liver transaminase enzymes. She also has moderate mental retardation secondary to cerebral palsy. She fears she will be harmed if she stays at the extendedcare facility, but we find no evidence that she has been abused or mistreated there.

Three months before presenting to us, Ms. G was hospitalized for 3 days to treat symptoms that suggested neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) but were apparently caused by her inadvertently stopping her antiparkinson agents.

One month later, Ms. G was hospitalized again, this time for acute psychosis. Quetiapine, which she had been taking for antiparkinson medication-induced psychosis, was increased from 100 mg nightly to 75 mg bid, with reportedly good effect.

Shortly afterward, however, Ms. G’s paranoia worsened. At the facility, she has called 911 several times to report imagined threats from staff members. After referral from her primary care physician, we evaluate Ms. G and admit her to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit.

At intake, Ms. G is anxious and uncomfortable with notable muscle spasticity and twitching of her arms and legs. Mostly wheelchair-bound, she has longstanding physical abnormalities (shuffling gait; dystonia; drooling; slowed, dysarthric speech) secondary to comorbid Parkinson’s and cerebral palsy. She is agitated at first but grows calmer and cooperative.

Mental status examination shows a disorganized, tangential thought process and evidence of paranoid delusions and auditory hallucinations, but she denies visual hallucinations. She has poor insight into her illness but is oriented to time, place, and person. She can recall two of three objects after 3 minutes of distraction. Attention and concentration are intact.

Ms. G denies depressed mood, anhedonia, mania, or suicidal or homicidal thoughts. Her mother says no stressors other than the imagined threats to her life have affected her daughter.

The patient ’s temperature at admission is 98.0°F, her pulse is 108 beats per minute, and her blood pressure is 150/88 mm Hg. Laboratory workup shows a white blood cell count of 10,100/mm3 (normal range: 4,000 to 10,000/mm3), sodium level of 132 mEq/L (normal range: 135 to 145 mEq/L), and aspartate (AST) and alanine (ALT) transaminase levels of 611 U/L and 79 U/L, respectively (normal range for each: 0 to 35 U/L).

Aside from quetiapine, Ms. G also has been taking carbidopa/levodopa, seven 25/100-mg tablets daily, and pramipexole, 3 mg/d, for parkinsonism; citalopram, 20 mg/d, for depression; trazodone, 300 mg nightly, and lorazepam, 0.5 mg nightly, for insomnia; lopressor, 25 mg every 12 hours, for hypertension; and tolterodine, 1 mg bid, for urinary incontinence.

The authors’ observations

Parkinsonism typically responds to dopaminergic treatment. Excess dopamine agonism is believed to contribute to medication-induced psychosis, a common and often disabling complication of Parkinson’s disease1,2 that often necessitates nursing home placement and may increase mortality.2,3

Paranoia occurs in approximately 8% of patients treated for drug-induced Parkinson’s psychosis, and hallucinations (typically visual) may occur in as many as 30%.2 Quetiapine, 50 to 225 mg/d, is considered a good first-line treatment for psychosis in Parkinson’s, although the agent has been tested for this use only in open-label trials.2,3

Mental retardation and pre-existing parkinsonism, however, may increase Ms. G’s risk for NMS, a rare but potentially fatal reaction to antipsychotics believed to be caused by a sudden D2 dopamine receptor blockade.4,5 Signs include autonomic instability, extrapyramidal symptoms, hyperpyrexia, and altered mental status.

Of 68 patients with NMS studied by Ananth et al,4 13.2% were mentally retarded, and uncontrolled studies6 have proposed mental retardation as a potential risk factor (Table 1). A 2003 case control study6 found a higher incidence of NMS among mentally retarded patients than among nonretarded persons, but the difference was not statistically significant. There are no known links between specific causes of mental retardation and NMS.

Even so, Ms. G’s psychosis is compromising her already diminished quality of life. We will increase her quetiapine dosage slightly and watch for early signs of NMS, including fever, confusion, and increased muscle rigidity.

Table 1

Factors that increase risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome*

| Abrupt antipsychotic cessation |

| Ambient heat |

| Catatonia |

| Dehydration |

| Exhaustion |

| Genetic predisposition |

| Greater dosage increases |

| Higher neuroleptic doses, especially with typical and atypical IM agents |

| Low serum iron |

| Malnutrition |

| Mental retardation |

| Pre-existing EPS or parkinsonism |

| Previous NMS episode |

| Psychomotor agitation |

| * Infection or concurrent organic brain disease are predisposing factors, but their association with NMS is less clear. |

| EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms |

| Source: References: 4-7, 14-15. |

TREATMENT: MEDICATION CHANGE

Upon admission, quetiapine is increased to 75 mg in the morning and 125 mg at bedtime—still well below the dosage at which quetiapine increases the risk of NMS (Table 2). Trazodone is decreased to 100 mg/d because of quetiapine’s sedating properties. Citalopram and tolterodine are stopped for fear that either agent would aggravate her psychosis. We continue all other drugs as previously prescribed. Her paranoia begins to subside.

Three days later, Ms. G’s is increasingly confused and agitated, and her temperature rises to 101.3°F. Physical exam shows increased muscle rigidity. She is given lorazepam, 1 mg, and transferred to the emergency room for evaluation.

In the ER, Ms. G’s temperature rises to 102.3°F. Other vital signs include:

- heart rate, 112 to 120 beats per minute

- respiratory rate, 18 to 20 breaths per minute

- oxygen saturation, 98% in room air

- blood pressure, 131/61 mm Hg while seated and 92/58 mm Hg while standing.

CNS or systemic infection and myocardial infarction are considered less likely because of her reactive pupils, lack of nuchal rigidity, troponin 3. Additionally, CSF shows normal glucose and protein levels, ALT and AST are 217 and 261 U/L, respectively, and chest x-ray shows no acute cardiopulmonary abnormality.

Ms. G is admitted to the medical intensive care unit and given IV fluids. All psychotropic and antiparkinson medications are stopped for 12 hours. Ms. G is then transferred to the general medical service for continued observation and IV hydration.

Six hours later, lorazepam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours, is resumed to control Ms. G’s anxiety. Carbidopa/levodopa is resumed at the previous dosage; all other medications remain on hold.

Renal damage is not apparent, but repeat chest x-ray taken 2 days after admission to the ER shows right middle lobe pneumonia, which resolved with antibiotics.

Six days after entering the medical unit, Ms. G is no longer agitated or paranoid. She is discharged that day and continued on lorazepam, 1 mg every 8 hours as needed to control her anxiety and prevent paranoia, and carbidopa/levidopa 8-1/2 25/100-mg tablets daily for her parkinsonism. Trazodone, 100 mg nightly, is continued for 3 days to help her sleep, as is amoxicillin/clavulanate, 500 mg every 8 hours, in case an underlying infection exists. Quetiapine, citalopram, and tolterodine are discontinued; all other medications are resumed as previously prescribed.

Table 2

Antipsychotic-related NMS risk increases at these dosages

| Agent | Dosage (mg/d) |

|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | >30 |

| Chlorpromazine | >400 |

| Clozapine | 318+/-299 |

| Olanzapine | 9.7+/-2.3 |

| Quetiapine | 412.5+/-317 |

| Risperidone | 4.3+/-3.1 |

| Ziprasidone | >20 |

| Source: References 4, 6, and 15. | |

The authors’ observations

Ms. G’s NMS symptoms surfaced 3 days after her quetiapine dosage was increased, suggesting that the antipsychotic may have caused this episode.

We ruled out antiparkinson agent withdrawal malignant syndrome—usually caused by abrupt cessation of Parkinson’s medications. Ms. G’s carbidopa/levodopa had not been adjusted before the symptoms emerged, and she did not worsen after the agent was stopped temporarily. Her brief pneumonia episode, however, could have caused symptoms that mimicked this withdrawal syndrome.

Antiparkinson agent withdrawal malignant syndrome symptoms resemble those of NMS.9,10 Worsening parkinsonism, dehydration, and infection increase the risk.10 Some research suggests that leukocytosis or elevated inflammation-related cytokines may accelerate withdrawal syndrome.10

The authors’ observations

Ms. G’s case illustrates the difficulty of treating psychosis in a patient at risk for NMS.

Of the 68 patients in the Ananth et al study with atypical antipsychotic-induced NMS, 11 were rechallenged after an NMS episode with the same agent and 8 were switched to another atypical. NMS recurred in 4 of these 19 patients.4

Ms. G was stable on lorazepam at discharge, but we would consider rechallenging with quetiapine or another antipsychotic if necessary. NMS recurs in 30% to 50%11 of patients after antipsychotic rechallenge, but waiting 2 weeks to resume antipsychotic therapy appears to reduce this risk.12 Benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy are acceptable—though unproven—second-line therapies if antipsychotic rechallenge is deemed too risky,11,13 such as in some patients with a previous severe NMS episode; evidence of stroke, Parkinson’s or other neurodegenerative disease; or multiple acute medical problems.

CONTINUED TREATMENT: A RELAPSE

Three months later, Ms. G is readmitted to the neurology service for 3 weeks after being diagnosed with elevated CK, possibly caused by NMS or rhabdomyolysis secondary to persistent dyskinesia. We believe an inadvertent decrease in her carbidopa/levodopa caused the episode, as she had taken no neuroleptics between hospitalizations.

Ms. G is discharged on quetiapine, 25 mg nightly, along with her other medications. Her current psychiatric and neurologic status is unknown.

The authors’ observations

Detecting NMS symptoms early is critical to preventing mortality. Although NMS risk with atypical and typical antipsychotics is similar,4 fewer deaths from NMS have been reported after use of atypicals (3 deaths among 68 cases) than typical neuroleptics (30% mortality rate in the 1960s and 70s, and 10% mortality from 1980-87).14 Earlier recognition and treatment may be decreasing NMS-related mortality.4

Consider NMS in the differential diagnosis when the patient’s mental status changes.

Related resources

- Emedicine: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. www.emedicine.com/med/topic2614.htm.

- Bhanushali MJ, Tuite PJ. The evaluation and management of patients with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Neurol Clin 2004;22:389-411.

- Susman VL. Clinical management of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatr Q 2001;72:325-36.

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Lopressor • Toprol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Tolterodine • Detrol

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Robert B. Milstein, MD, PhD, and Benjamin Zigun, MD, JD, for their help in preparing this article for publication.

This project is supported by funds from the Division of State, Community, and Public Health, Bureau of Health Professions (BHPr), Health Resources and Services Administration (HSRA), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) under grant number 1 K01 HP 00071-02 and Geriatric Academic Career Award ($58,009). The content and conclusion are those of Dr. Tampi and are not the official position or policy of, nor should be any endorsements be inferred by, the Bureau of Health Professions, HRSA, DHHS or the United States Government.

1. Samii A, Nutt JG, Ransom BR. Parkinson’s disease Lancet 2004;363(9423):1783-93.

2. Reddy S, Factor SA, Molho ES, Feustel PJ. The effect of quetiapine on psychosis and motor function in parkinsonian patients with and without dementia. Movement Disord 2002;17:676-81.

3. Kang GA, Bronstein JM. Psychosis in nursing home patients with Parkinson’s disease. J Am Med Dir Assoc 2004;5:167-73.

4. Ananth J, Parameswaran S, Gunatilake S, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and atypical antipsychotic drugs. J Clin Psychiatry 2004;65:464-70.

5. Mann SC, Caroff SN, Keck PE, Jr, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. In: Mann SC, Caroff SN, Keck PE Jr, et al. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome and related conditions (2nd ed). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2003;1:44.-

6. Viejo LF, Morales V, Punal P, et al. Risk factors in neuroleptic malignant syndrome. A case-control study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 2003;107:45-9.

7. Adnet P, Lestavel P, Krivosic-Horber R. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome Br J Anaesthesia 2000;85:129-35.

8. Takubo H, Shimoda-Matsubayashi S, Mizuno Y. Serum creatine kinase is elevated in patients with Parkinson’s disease: a case controlled study. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2003;9 suppl 1:S43-S46.

9. Mizuno Y, Takubo H, Mizuta E, Kuno S. Malignant syndrome in Parkinson’s disease: concept and review of the literature. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2003;9 suppl 1:S3-S9.

10. Hashimoto T, Tokuda T, Hanyu N, et al. Withdrawal of levodopa and other risk factors for malignant syndrome in Parkinson’s disease. Parkinsonism Relat Disord 2003;9 suppl 1:S25-S30.

11. Bhanushali MJ, Tuite PJ. The evaluation and management of patients with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Neurol Clin 2004;22:389-411.

12. Rosebush P, Stewart T. A prospective analysis of 24 episodes of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Am J Psychiatry 1989;146:717-25.

13. Susman VL. Clinical management of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatr Q 2001;72:325-36.

14. Caroff S, Mann SC. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Med Clin North Am 1993;77:185-202.

15. Woods SW. Chlorpromazine equivalent doses for the newer atypical antipsychotics. J Clin Psychiatry 2003;64:663-7.

HISTORY: ‘THEY’RE TRYING TO KILL ME’

For the past 7 months Ms. G, age 47, has had worsening paranoid thoughts and sleep disturbances. She sleeps 4 hours or less a night, and her appetite and energy are diminished.

Her mother reports that Ms. G, who lives in an extended-care facility, believes the staff has injected embalming fluid into her body and is plotting to kill her. She says her daughter also has “fits” during which she hears a deafening noise that sounds like a vacuum cleaner, followed by a feeling of being pushed to the ground. Ms. G tells us that someone or something invisible is trying to control her.

Ms. G was diagnosed 2 years ago as having Parkinson’s disease and has chronically high liver transaminase enzymes. She also has moderate mental retardation secondary to cerebral palsy. She fears she will be harmed if she stays at the extendedcare facility, but we find no evidence that she has been abused or mistreated there.

Three months before presenting to us, Ms. G was hospitalized for 3 days to treat symptoms that suggested neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) but were apparently caused by her inadvertently stopping her antiparkinson agents.

One month later, Ms. G was hospitalized again, this time for acute psychosis. Quetiapine, which she had been taking for antiparkinson medication-induced psychosis, was increased from 100 mg nightly to 75 mg bid, with reportedly good effect.

Shortly afterward, however, Ms. G’s paranoia worsened. At the facility, she has called 911 several times to report imagined threats from staff members. After referral from her primary care physician, we evaluate Ms. G and admit her to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit.

At intake, Ms. G is anxious and uncomfortable with notable muscle spasticity and twitching of her arms and legs. Mostly wheelchair-bound, she has longstanding physical abnormalities (shuffling gait; dystonia; drooling; slowed, dysarthric speech) secondary to comorbid Parkinson’s and cerebral palsy. She is agitated at first but grows calmer and cooperative.

Mental status examination shows a disorganized, tangential thought process and evidence of paranoid delusions and auditory hallucinations, but she denies visual hallucinations. She has poor insight into her illness but is oriented to time, place, and person. She can recall two of three objects after 3 minutes of distraction. Attention and concentration are intact.

Ms. G denies depressed mood, anhedonia, mania, or suicidal or homicidal thoughts. Her mother says no stressors other than the imagined threats to her life have affected her daughter.

The patient ’s temperature at admission is 98.0°F, her pulse is 108 beats per minute, and her blood pressure is 150/88 mm Hg. Laboratory workup shows a white blood cell count of 10,100/mm3 (normal range: 4,000 to 10,000/mm3), sodium level of 132 mEq/L (normal range: 135 to 145 mEq/L), and aspartate (AST) and alanine (ALT) transaminase levels of 611 U/L and 79 U/L, respectively (normal range for each: 0 to 35 U/L).

Aside from quetiapine, Ms. G also has been taking carbidopa/levodopa, seven 25/100-mg tablets daily, and pramipexole, 3 mg/d, for parkinsonism; citalopram, 20 mg/d, for depression; trazodone, 300 mg nightly, and lorazepam, 0.5 mg nightly, for insomnia; lopressor, 25 mg every 12 hours, for hypertension; and tolterodine, 1 mg bid, for urinary incontinence.

The authors’ observations

Parkinsonism typically responds to dopaminergic treatment. Excess dopamine agonism is believed to contribute to medication-induced psychosis, a common and often disabling complication of Parkinson’s disease1,2 that often necessitates nursing home placement and may increase mortality.2,3

Paranoia occurs in approximately 8% of patients treated for drug-induced Parkinson’s psychosis, and hallucinations (typically visual) may occur in as many as 30%.2 Quetiapine, 50 to 225 mg/d, is considered a good first-line treatment for psychosis in Parkinson’s, although the agent has been tested for this use only in open-label trials.2,3

Mental retardation and pre-existing parkinsonism, however, may increase Ms. G’s risk for NMS, a rare but potentially fatal reaction to antipsychotics believed to be caused by a sudden D2 dopamine receptor blockade.4,5 Signs include autonomic instability, extrapyramidal symptoms, hyperpyrexia, and altered mental status.

Of 68 patients with NMS studied by Ananth et al,4 13.2% were mentally retarded, and uncontrolled studies6 have proposed mental retardation as a potential risk factor (Table 1). A 2003 case control study6 found a higher incidence of NMS among mentally retarded patients than among nonretarded persons, but the difference was not statistically significant. There are no known links between specific causes of mental retardation and NMS.

Even so, Ms. G’s psychosis is compromising her already diminished quality of life. We will increase her quetiapine dosage slightly and watch for early signs of NMS, including fever, confusion, and increased muscle rigidity.

Table 1

Factors that increase risk of neuroleptic malignant syndrome*

| Abrupt antipsychotic cessation |

| Ambient heat |

| Catatonia |

| Dehydration |

| Exhaustion |

| Genetic predisposition |

| Greater dosage increases |

| Higher neuroleptic doses, especially with typical and atypical IM agents |

| Low serum iron |

| Malnutrition |

| Mental retardation |

| Pre-existing EPS or parkinsonism |

| Previous NMS episode |

| Psychomotor agitation |

| * Infection or concurrent organic brain disease are predisposing factors, but their association with NMS is less clear. |

| EPS: extrapyramidal symptoms |

| Source: References: 4-7, 14-15. |

TREATMENT: MEDICATION CHANGE

Upon admission, quetiapine is increased to 75 mg in the morning and 125 mg at bedtime—still well below the dosage at which quetiapine increases the risk of NMS (Table 2). Trazodone is decreased to 100 mg/d because of quetiapine’s sedating properties. Citalopram and tolterodine are stopped for fear that either agent would aggravate her psychosis. We continue all other drugs as previously prescribed. Her paranoia begins to subside.

Three days later, Ms. G’s is increasingly confused and agitated, and her temperature rises to 101.3°F. Physical exam shows increased muscle rigidity. She is given lorazepam, 1 mg, and transferred to the emergency room for evaluation.

In the ER, Ms. G’s temperature rises to 102.3°F. Other vital signs include:

- heart rate, 112 to 120 beats per minute

- respiratory rate, 18 to 20 breaths per minute

- oxygen saturation, 98% in room air

- blood pressure, 131/61 mm Hg while seated and 92/58 mm Hg while standing.

CNS or systemic infection and myocardial infarction are considered less likely because of her reactive pupils, lack of nuchal rigidity, troponin 3. Additionally, CSF shows normal glucose and protein levels, ALT and AST are 217 and 261 U/L, respectively, and chest x-ray shows no acute cardiopulmonary abnormality.

Ms. G is admitted to the medical intensive care unit and given IV fluids. All psychotropic and antiparkinson medications are stopped for 12 hours. Ms. G is then transferred to the general medical service for continued observation and IV hydration.

Six hours later, lorazepam, 0.5 mg every 8 hours, is resumed to control Ms. G’s anxiety. Carbidopa/levodopa is resumed at the previous dosage; all other medications remain on hold.

Renal damage is not apparent, but repeat chest x-ray taken 2 days after admission to the ER shows right middle lobe pneumonia, which resolved with antibiotics.

Six days after entering the medical unit, Ms. G is no longer agitated or paranoid. She is discharged that day and continued on lorazepam, 1 mg every 8 hours as needed to control her anxiety and prevent paranoia, and carbidopa/levidopa 8-1/2 25/100-mg tablets daily for her parkinsonism. Trazodone, 100 mg nightly, is continued for 3 days to help her sleep, as is amoxicillin/clavulanate, 500 mg every 8 hours, in case an underlying infection exists. Quetiapine, citalopram, and tolterodine are discontinued; all other medications are resumed as previously prescribed.

Table 2

Antipsychotic-related NMS risk increases at these dosages

| Agent | Dosage (mg/d) |

|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | >30 |

| Chlorpromazine | >400 |

| Clozapine | 318+/-299 |

| Olanzapine | 9.7+/-2.3 |

| Quetiapine | 412.5+/-317 |

| Risperidone | 4.3+/-3.1 |

| Ziprasidone | >20 |

| Source: References 4, 6, and 15. | |

The authors’ observations

Ms. G’s NMS symptoms surfaced 3 days after her quetiapine dosage was increased, suggesting that the antipsychotic may have caused this episode.

We ruled out antiparkinson agent withdrawal malignant syndrome—usually caused by abrupt cessation of Parkinson’s medications. Ms. G’s carbidopa/levodopa had not been adjusted before the symptoms emerged, and she did not worsen after the agent was stopped temporarily. Her brief pneumonia episode, however, could have caused symptoms that mimicked this withdrawal syndrome.

Antiparkinson agent withdrawal malignant syndrome symptoms resemble those of NMS.9,10 Worsening parkinsonism, dehydration, and infection increase the risk.10 Some research suggests that leukocytosis or elevated inflammation-related cytokines may accelerate withdrawal syndrome.10

The authors’ observations

Ms. G’s case illustrates the difficulty of treating psychosis in a patient at risk for NMS.

Of the 68 patients in the Ananth et al study with atypical antipsychotic-induced NMS, 11 were rechallenged after an NMS episode with the same agent and 8 were switched to another atypical. NMS recurred in 4 of these 19 patients.4

Ms. G was stable on lorazepam at discharge, but we would consider rechallenging with quetiapine or another antipsychotic if necessary. NMS recurs in 30% to 50%11 of patients after antipsychotic rechallenge, but waiting 2 weeks to resume antipsychotic therapy appears to reduce this risk.12 Benzodiazepines and electroconvulsive therapy are acceptable—though unproven—second-line therapies if antipsychotic rechallenge is deemed too risky,11,13 such as in some patients with a previous severe NMS episode; evidence of stroke, Parkinson’s or other neurodegenerative disease; or multiple acute medical problems.

CONTINUED TREATMENT: A RELAPSE

Three months later, Ms. G is readmitted to the neurology service for 3 weeks after being diagnosed with elevated CK, possibly caused by NMS or rhabdomyolysis secondary to persistent dyskinesia. We believe an inadvertent decrease in her carbidopa/levodopa caused the episode, as she had taken no neuroleptics between hospitalizations.

Ms. G is discharged on quetiapine, 25 mg nightly, along with her other medications. Her current psychiatric and neurologic status is unknown.

The authors’ observations

Detecting NMS symptoms early is critical to preventing mortality. Although NMS risk with atypical and typical antipsychotics is similar,4 fewer deaths from NMS have been reported after use of atypicals (3 deaths among 68 cases) than typical neuroleptics (30% mortality rate in the 1960s and 70s, and 10% mortality from 1980-87).14 Earlier recognition and treatment may be decreasing NMS-related mortality.4

Consider NMS in the differential diagnosis when the patient’s mental status changes.

Related resources

- Emedicine: Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. www.emedicine.com/med/topic2614.htm.

- Bhanushali MJ, Tuite PJ. The evaluation and management of patients with neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Neurol Clin 2004;22:389-411.

- Susman VL. Clinical management of neuroleptic malignant syndrome. Psychiatr Q 2001;72:325-36.

- Amoxicillin/clavulanate • Augmentin

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Carbidopa/levodopa • Sinemet

- Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

- Citalopram • Celexa

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Lopressor • Toprol

- Lorazepam • Ativan

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Pramipexole • Mirapex

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Tolterodine • Detrol

- Trazodone • Desyrel

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

The authors report no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Robert B. Milstein, MD, PhD, and Benjamin Zigun, MD, JD, for their help in preparing this article for publication.

This project is supported by funds from the Division of State, Community, and Public Health, Bureau of Health Professions (BHPr), Health Resources and Services Administration (HSRA), Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) under grant number 1 K01 HP 00071-02 and Geriatric Academic Career Award ($58,009). The content and conclusion are those of Dr. Tampi and are not the official position or policy of, nor should be any endorsements be inferred by, the Bureau of Health Professions, HRSA, DHHS or the United States Government.

HISTORY: ‘THEY’RE TRYING TO KILL ME’

For the past 7 months Ms. G, age 47, has had worsening paranoid thoughts and sleep disturbances. She sleeps 4 hours or less a night, and her appetite and energy are diminished.

Her mother reports that Ms. G, who lives in an extended-care facility, believes the staff has injected embalming fluid into her body and is plotting to kill her. She says her daughter also has “fits” during which she hears a deafening noise that sounds like a vacuum cleaner, followed by a feeling of being pushed to the ground. Ms. G tells us that someone or something invisible is trying to control her.

Ms. G was diagnosed 2 years ago as having Parkinson’s disease and has chronically high liver transaminase enzymes. She also has moderate mental retardation secondary to cerebral palsy. She fears she will be harmed if she stays at the extendedcare facility, but we find no evidence that she has been abused or mistreated there.

Three months before presenting to us, Ms. G was hospitalized for 3 days to treat symptoms that suggested neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS) but were apparently caused by her inadvertently stopping her antiparkinson agents.

One month later, Ms. G was hospitalized again, this time for acute psychosis. Quetiapine, which she had been taking for antiparkinson medication-induced psychosis, was increased from 100 mg nightly to 75 mg bid, with reportedly good effect.

Shortly afterward, however, Ms. G’s paranoia worsened. At the facility, she has called 911 several times to report imagined threats from staff members. After referral from her primary care physician, we evaluate Ms. G and admit her to the adult inpatient psychiatric unit.

At intake, Ms. G is anxious and uncomfortable with notable muscle spasticity and twitching of her arms and legs. Mostly wheelchair-bound, she has longstanding physical abnormalities (shuffling gait; dystonia; drooling; slowed, dysarthric speech) secondary to comorbid Parkinson’s and cerebral palsy. She is agitated at first but grows calmer and cooperative.

Mental status examination shows a disorganized, tangential thought process and evidence of paranoid delusions and auditory hallucinations, but she denies visual hallucinations. She has poor insight into her illness but is oriented to time, place, and person. She can recall two of three objects after 3 minutes of distraction. Attention and concentration are intact.

Ms. G denies depressed mood, anhedonia, mania, or suicidal or homicidal thoughts. Her mother says no stressors other than the imagined threats to her life have affected her daughter.

The patient ’s temperature at admission is 98.0°F, her pulse is 108 beats per minute, and her blood pressure is 150/88 mm Hg. Laboratory workup shows a white blood cell count of 10,100/mm3 (normal range: 4,000 to 10,000/mm3), sodium level of 132 mEq/L (normal range: 135 to 145 mEq/L), and aspartate (AST) and alanine (ALT) transaminase levels of 611 U/L and 79 U/L, respectively (normal range for each: 0 to 35 U/L).

Aside from quetiapine, Ms. G also has been taking carbidopa/levodopa, seven 25/100-mg tablets daily, and pramipexole, 3 mg/d, for parkinsonism; citalopram, 20 mg/d, for depression; trazodone, 300 mg nightly, and lorazepam, 0.5 mg nightly, for insomnia; lopressor, 25 mg every 12 hours, for hypertension; and tolterodine, 1 mg bid, for urinary incontinence.

The authors’ observations

Parkinsonism typically responds to dopaminergic treatment. Excess dopamine agonism is believed to contribute to medication-induced psychosis, a common and often disabling complication of Parkinson’s disease1,2 that often necessitates nursing home placement and may increase mortality.2,3

Paranoia occurs in approximately 8% of patients treated for drug-induced Parkinson’s psychosis, and hallucinations (typically visual) may occur in as many as 30%.2 Quetiapine, 50 to 225 mg/d, is considered a good first-line treatment for psychosis in Parkinson’s, although the agent has been tested for this use only in open-label trials.2,3

Mental retardation and pre-existing parkinsonism, however, may increase Ms. G’s risk for NMS, a rare but potentially fatal reaction to antipsychotics believed to be caused by a sudden D2 dopamine receptor blockade.4,5 Signs include autonomic instability, extrapyramidal symptoms, hyperpyrexia, and altered mental status.

Of 68 patients with NMS studied by Ananth et al,4 13.2% were mentally retarded, and uncontrolled studies6 have proposed mental retardation as a potential risk factor (Table 1). A 2003 case control study6 found a higher incidence of NMS among mentally retarded patients than among nonretarded persons, but the difference was not statistically significant. There are no known links between specific causes of mental retardation and NMS.