User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Recovery from schizophrenia: Fact or fiction?

Is it realistic for patients with schizophrenia to believe they can recover? Recent observational studies show that some do,1 even though all DSM editions have defined schizophrenia as a chronic disease with a poor outcome.2

Our understanding of schizophrenia is changing as we gain new insights into:

- mechanism of recovery

- efficacy of combined psychotherapeutic, psychosocial, and drug therapies for sustaining remission and recovery

- the value of long-term aftercare. This article examines evidence on:

- achieving recovery from schizophrenia

- factors associated with remission

- treatments that may help prevent relapse and lead to stable, lasting recovery.

What is ‘recovery’?

Diagnostic criteria. Recovery from schizophrenia has social, occupational, symptomatic, and psychostructural dimensions. For clinical practice, Liberman et al3 developed a useful set of 10 criteria for recovery (Table 1) by analyzing the literature and cases of 23 schizophrenia patients who returned to work or school with their symptoms under control.

Table 1

Recovery from schizophrenia: 10 clinical criteria

| Criteria | Characteristics of recovered patients* |

|---|---|

| Family relationships | 70% reported good or very good family relationships |

| Substance abuse | None reported illicit drug use in the past year, and two reported occasional alcohol consumption |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | Only 13% reported >1 year delay between symptom onset and treatment |

| Initial response to medication | 87% reported effective symptom control with their first antipsychotic medication |

| Adherence to treatment | All reported adherence to psychiatric care and medication regimens |

| Supportive therapy | 91% reported ongoing psychotherapy, and 78% reported that accessible and supportive psychiatrists and therapists aided their recovery |

| Cognitive abilities | Normal or near-normal functioning on tests of flexibility in solving problems, verbal working memory, and perceptual skills |

| Social skills | None showed more than very mild negative symptoms |

| Personal history | 70% graduated from college, 13% completed 2 years of college, and 3 of remaining 4 worked full time before becoming ill |

| Access to care | 91% received antipsychotics and psychotherapy, 48% social skills training, 57% family participation, 26% vocational rehabilitation, and 61% self-help groups |

| * Based on a study of 23 schizophrenia patients who returned to work or school with their symptoms under control. | |

| Source: Reference 3 | |

Recovery is not a smooth, linear progression. Even when patients attain remission, they often find it hard to make up for “lost life” during years of disability.4 Recovery also can be defined as social, emotional, and biological maturation. This definition considers recovery not as an end-state or cure but as a process of personal growth.5

Several groups proposed recently that recovery from schizophrenia includes four processes:

- finding hope

- re-establishing identity

- taking responsibility for recovery

- finding meaning6 and “getting on with life”7 (Box).

Long-tem vs short-term

Recovery has been studied in many populations, but the evidence is difficult to compare. Data quality is compromised by poorly-defined cohorts, weak study designs, and lack of clear definitions of recovery and its diagnostic criteria. Moreover, empirical evidence is lacking on recovery’s multidimensional nature, including psychosocial, biochemical, genetic, environmental, cultural, and ethnic correlates.

Long-term recovery. Recently, three studies of American populations diagnosed with schizophrenia detected trends toward long-term (>5 years) recovery.

U.S. populations. Modestin et al8 in 2003 re-evaluated diagnoses of 208 patients in Swiss psychiatrist Manfred Bleuler’s influential 1972 study on schizophrenia’s long-term course. Using DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) criteria, the authors excluded about 30% of the original patients (most rediagnosed with schizoaffective disorder). Among those remaining, 12% to 15% showed long-term recovery and one-half had an undulating course with remissions.

In 1997, Stephens et al9 examined hospital records from 1913 to 1940 of 484 patients, mean age 27, hospitalized with schizophrenia. Using >5 years of follow-up data and DSM-IV criteria, the authors rated 13% as recovered and 58% unimproved.

Also in 1997, Harrow et al10 evaluated 74 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia by DSM-IV criteria at 2, 4.5, and 7.5 years. In this longitudinal study, one-third (32%) showed complete remission at one follow-up session, compared with 5% at all three evaluations.

This study suggested that schizophrenia patients show relatively poor functioning, compared with other psychotic patients. Over time, however, the likelihood of long-term remission appeared to increase. A similar pattern was seen in a sample of 658 Americans age >65 with schizophrenia diagnosed by DSM-III criteria. As these patients aged, 15% developed long-lasting remission.11

Elsewhere, empirical findings across 15 years from three Norwegian studies indicate that lasting recovery from schizophrenia—with symptom improvement and psychosocial adjustment—is rare (3% to 5% of patients).3 Similarly, only 4% of a Scandinavian sample of 301 patients attained complete, long-term remission during 3 to 39 years of follow-up.12

Across cultures, an international study13 evaluated 15- and 25-year outcomes in 1,633 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Approximately 50% had favorable outcomes—stable work, independent from support, no imprisonment, no substance abuse, no rehospitalization, improved social life—but heterogeneity was marked.

Ms J, 48, is in recovery from schizophrenia. She has a stable job as a Web designer, is married, and has learned to build and maintain social relationships. Much of her life, however, has been very different.

At age 15 she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid psychotic type, with occasional comorbid bipolar symptoms. Over the next 20 years, she was admitted to psychiatric hospitals six times for treatment. At age 36, she was hospitalized with psychosis, depressive symptoms, and insomnia. At that point, she was taking carbamazepine, 500 mg/d, for mood stabilization, and haloperidol, 50 mg/d.

Changing medications. Her psychiatriststarted olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and tapered off haloperidol, which appeared to be gradually becoming less effective while causing mood-related side effects. Ms. J’s psychosis persisted, however, with no response to olanzapine.

Her psychiatrist then tapered carbamazepine to 175 mg/d while starting lamotrigine, 150 to 300 mg/d. The rationale for switching mood stabilizers was that lamotrigine may be more effective than carbamazepine in controlling mixed bipolar states, provide a greater antidepressant effect, and cause fewer side effects.

Intensive treatment. Within 10 days, Ms J’s thought form and composition improved, and her psychiatrist immediately started psychotherapy and psychosocial guidance. Carbamazepine was withdrawn 3 months later, but Ms. J remained on olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 300 mg/d. With these medications, the paranoid psychosis went into remission.

After 5 months of intensive treatment, Ms. J was discharged. Outpatient treatment included weekly psychotherapy plus psychosocial guidance and social and coping training 6 times per month. These therapies —along with olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and carbamazepine, 300 mg/d—continue today.

Ms. J’s mental and emotional condition stabilized, and her cognitive abilities improved. Education and therapy helped reduce stress within her family. She has not been rehospitalized or suffered a serious relapse in 12 years.

Table 2

Psychosocial interventions for patients in recovery from schizophrenia*

|

| * Psychosocial interventions are most effective when combined with antipsychotic therapy and individualized psychotherapy |

Short-term course predicted long-term outcome, and local environment played a significant role in determining symptoms and social disability. The authors concluded that adequate early treatment and an optimum environment might lead to favorable long-term outcome.

In the United Kingdom, 14% of a sample of patients diagnosed by ICD-10 criteria achieved remission across a mean 8.5 years.14 In a study of Czechoslovakian patients (70 men, 50 women) with early-onset schizophrenia diagnosed by DSM-III-R criteria, 10% recovered during 13 to 42 years of follow-up.15

Short-term recovery. The McLean-Harvard first-episode project examined outcomes 6 months after schizophrenia diagnosis in 102 patients (55 men, 47 women). Sixty-five percent attained syndromal recovery (significant reduction of diagnostic features), whereas only 33% achieved functional recovery (increased social-emotional, vocational, and coping abilities).16

In Japan, 62 patients (33 men, 29 women; mean age 25) were followed for 13 years after a first hospitalization for schizophrenia. The authors reported an undulating course with recovery or a mild end-state in 53%, and a simple course of recovery and a moderate or severe end-state in 28%.17

Conclusions. The evidence suggests that early and lasting treatment of schizophrenic symptoms—even in recovered patients—might prevent frequent rehospitalizations. Thus, patients with schizophrenia must be followed carefully during and after recovery. Health care professionals, colleagues, friends, and relatives can help patients sustain recovery by watching for the earliest signs of deterioration and intervening before relapse occurs.

Strategies for recovery

Therapeutic factors. Many studies suggest psychosocial interventions (Table 2), psychotherapy, and medication are most effective in combination for stabilizing patients with schizophrenia and continuing their recovery. Other patient factors that may contribute to recovery include:

- quality of relationships with family, friends, and professional caregivers

- ability and motivation to use resources and take responsibility for one’s life

- spiritual and religious activities

- awareness that recovery is possible.

Sells et al18 noted that attempting to make new contacts outside of their former spheres (“positive withdrawal”) may allow schizophrenia patients to reconsider and ultimately recover a durable sense of self.

We at the W. Kahn Institute19 find that all these treatment strategies may be useful and even necessary to continue and stabilize recovery from schizophrenia. We feel they merit the attention of all professionals involved in recovered patients’ aftercare and guidance.

Table 3

Suggested antipsychotic dosages during schizophrenia recovery*

| Drug | Dosage (mg/d) | Potential side effects | Positive effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | 10 to 30 | Headache, anxiety, insomnia, lightheadedness | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Clozapine | 300 to 900 | Withdrawal, blunted emotions, seizures, lack of motivation | Reduced positive symptoms |

| Haloperidol | 30 to 100 | Tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonian symptoms, insomnia, depressive reactions, confusion, drowsiness, hypertension | Reduced mania, hyperactivity, agitation |

| Olanzapine | 5 to 10 | Drowsiness, agitation, weight gain, involuntary movements, restlessness | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Quetiapine | 25 to 100 | Dizziness, hypotension, increased cholesterol, weight gain | Reduced positive symptoms |

| Risperidone | 2.5 to 5 | Anxiety, nervousness, back pain, bleeding, dizziness, irregular blood pressure | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Ziprasidone | 10 to 200 | Heart-rhythm irregularity, loss of consciousness, restlessness, weakness, drowsiness | Reduced positive symptoms |

| * Dosages are individualized and may vary among patients and situations, but most will be gradually reduced to minimum levels during remission. | |||

Social/vocational network. Family, friends, neighbors, and social workers play an important role in the patient’s development during recovery. They provide positive stimulation (such as physical activities and social or vocational engagements) and support.

To equip the patient’s network for this responsible task, provide them with training (such as in acceptance, empathy, feedback, and communication), education, and guidance. Support groups can enhance the social networks of patients whose own networks are too small to prevent social isolation or overburdening of members.

Vocational training and mediation also may be stabilizing. Religious activities are central to self-understanding and recovery for many psychiatric patients and may improve outcomes.20

Patient skills. To achieve stabilization and continue their recovery, patients must develop social interaction skills and coping strategies. Conversation training, for example, seems to help improve social interaction. Patients in remission must learn to:

- find or create low-stress, positively stimulating environments in which their recovery can flourish

- tolerate discomfort and stress

- overcome internalized stigma about recovery.

Patients also need to learn when and how to withdraw from hectic, stressful environments and from people who are overly emotional, patronizing, or hold unrealistic expectations about them.

Pharmacotherapy. Sound pharmacotherapy underlies rehabilitation and psychosocial treatment of patients in remission from schizophrenia.21 Healthy neurobiological functioning and equilibrium may help normalize social-emotional behavior and create opportunities to improve all life dimensions via psychotherapy, psychosocial guidance, education, and training.

Dosages often can be reduced during recovery, titrating gradually downward to reduce the risk of relapse. Suggested antipsychotic dosages during recovery are listed in Table 3. Be patient and consistent when adjusting dosages, guided by information in package inserts, from clinical trials, and in recent articles on specific medications. When introducing a medication, start with the lowest dosage and increase in small steps until symptoms are reduced and side effects are minimal.

Discontinuing antipsychotics. Is it therapeutically reasonable to discontinue antipsychotics after recovery? Probably not.

Relapse rates in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia appear extremely high—perhaps 8 or 9 out of 10 cases—even during remission. By comparison, relapse rates appear very low—perhaps 3 or 4 out of 10 cases—for remitted patients who remain on antipsychotics. Atypical antipsychotics or low doses of conventional agents are generally well-tolerated and safe in the long term.22

Patient monitoring. Patients in remission from schizophrenia benefit from:

- 24-hour phone lines to call for guidance, treatment, and quick interventions

- central, alert treatment coordination among psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, therapists, vocational experts, and activity counselors.

Psychiatrists in solo or small-group settings may need to seek out these resources in their communities. The goal of this team approach—in cooperation with the patient’s social network—is to help the patient develop employment and social activities appropriate to his or her needs and capabilities.

Related resources

- Ascher-Svanuw H, Kraus A. Psychoeducational groups for patients with schizophrenia: a guide for practitioners. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 1991.

- Suzuki T, Uchida H, Tanaka KF, et al. Revising polypharmacy to a single antipsychotic regimen for patients with chronic schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004;7(2):133-42.

- American Psychiatric Association. Schizophrenia (patient/family information). www.psych.org/public_info/schizo.cfm

- Schizophrenia.com. Nonprofit Web community providing information, support, and education. www.schizophrenia.com

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Davidson L. Living outside mental illness: qualitative studies of recovery in schizophrenia. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

2. Kruger A. Schizophrenia: Recovery and hope. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2000;24(1):29-37.

3. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):256-72.

4. Torgalsboen AK, Rund BR. Lessons learned from three studies of recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):312-17.

5. Boone EC. A qualitative investigation of the process of recovery in people experiencing schizophrenia. Dissert Abstr Int 1996;57 (5-B):3402.-

6. Andresen R, Oades L, Caputi P. The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003;37(5):586-94.

7. Noordsy D, Torrey W, Mueser K, et al. Recovery from severe mental illness: an interpersonal and functional outcome definition. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):318-26.

8. Modestin J, Huber A, Satirli E, et al. Long-term course of schizophrenic illness: Bleuler’s study reconsidered. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(12):2202-8.

9. Stephens JH, Richard P, McHugh PR. Long-term follow-up of patients hospitalized for schizophrenia, 1913 to1940. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997;185(12):715-21.

10. Harrow M, Sands JR, Silverstein ML, Goldberg JF. Course and outcome for schizophrenia versus other psychotic patients: a longitudinal study. Schizophr Bull 1997;23:287-303.

11. Craig TJ, Bregman Z. Late-onset schizophrenia-like illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36(2):104-7.

12. Opjordsmoen S. Long-term course and outcome in unipolar affective and schizoaffective psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;79(4):317-26.

13. Harris G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

14. Kiriakakis V, Bhatia KP, Quinn NP, Marsden CD. The natural history of tardive dystonia. A long-term follow-up study of 107 cases. Brain 1998;121(Pt 11):2053-66.

15. Mala E. Early onset schizophrenia. Cesk Slov Psychiatry 1993;89(5):259-71.

16. Tohen M, Strakowski SM, Zarate C, et al. The McLean-Harvard first episode project: 6-month symptomatic and functional outcome in affective and non-affective psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48(6):467-76.

17. Kobayashi T. Course types of first admission schizophrenia: A mean 13-year follow back study. Seishin Igaku Clin Psychiatry 2002;44(2):161-8.

18. Sells DJ, Stayner DA, Davidson L. Recovering the self in schizophrenia: An integrative review of qualitative studies. Psychiatr Q. 2004;75(1):87-97.

19. Martens WHJ, Kahn W, Oppenheimer C. Predictors and prevalence of recovery in schizophrenia. W. Kahn Institute of Theoretical Psychiatry and Neuroscience (WKITPN) Publication 36, 2001(5):113-26.

20. Fallot RD. The place of spirituality and religion in mental health services. In: Lamb HR (ed). Best of new directions for mental health services, 1979-2001. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2001:79-88.

21. Kane JM. Long-term treatment of schizophrenia: Moving from a relapse-prevention model to a recovery model. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1384-5.

22. Tauscher-Wisniewski S, Zipursky RB. The role of maintenance pharmacotherapy in achieving recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2002;14(4):284-92.

Is it realistic for patients with schizophrenia to believe they can recover? Recent observational studies show that some do,1 even though all DSM editions have defined schizophrenia as a chronic disease with a poor outcome.2

Our understanding of schizophrenia is changing as we gain new insights into:

- mechanism of recovery

- efficacy of combined psychotherapeutic, psychosocial, and drug therapies for sustaining remission and recovery

- the value of long-term aftercare. This article examines evidence on:

- achieving recovery from schizophrenia

- factors associated with remission

- treatments that may help prevent relapse and lead to stable, lasting recovery.

What is ‘recovery’?

Diagnostic criteria. Recovery from schizophrenia has social, occupational, symptomatic, and psychostructural dimensions. For clinical practice, Liberman et al3 developed a useful set of 10 criteria for recovery (Table 1) by analyzing the literature and cases of 23 schizophrenia patients who returned to work or school with their symptoms under control.

Table 1

Recovery from schizophrenia: 10 clinical criteria

| Criteria | Characteristics of recovered patients* |

|---|---|

| Family relationships | 70% reported good or very good family relationships |

| Substance abuse | None reported illicit drug use in the past year, and two reported occasional alcohol consumption |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | Only 13% reported >1 year delay between symptom onset and treatment |

| Initial response to medication | 87% reported effective symptom control with their first antipsychotic medication |

| Adherence to treatment | All reported adherence to psychiatric care and medication regimens |

| Supportive therapy | 91% reported ongoing psychotherapy, and 78% reported that accessible and supportive psychiatrists and therapists aided their recovery |

| Cognitive abilities | Normal or near-normal functioning on tests of flexibility in solving problems, verbal working memory, and perceptual skills |

| Social skills | None showed more than very mild negative symptoms |

| Personal history | 70% graduated from college, 13% completed 2 years of college, and 3 of remaining 4 worked full time before becoming ill |

| Access to care | 91% received antipsychotics and psychotherapy, 48% social skills training, 57% family participation, 26% vocational rehabilitation, and 61% self-help groups |

| * Based on a study of 23 schizophrenia patients who returned to work or school with their symptoms under control. | |

| Source: Reference 3 | |

Recovery is not a smooth, linear progression. Even when patients attain remission, they often find it hard to make up for “lost life” during years of disability.4 Recovery also can be defined as social, emotional, and biological maturation. This definition considers recovery not as an end-state or cure but as a process of personal growth.5

Several groups proposed recently that recovery from schizophrenia includes four processes:

- finding hope

- re-establishing identity

- taking responsibility for recovery

- finding meaning6 and “getting on with life”7 (Box).

Long-tem vs short-term

Recovery has been studied in many populations, but the evidence is difficult to compare. Data quality is compromised by poorly-defined cohorts, weak study designs, and lack of clear definitions of recovery and its diagnostic criteria. Moreover, empirical evidence is lacking on recovery’s multidimensional nature, including psychosocial, biochemical, genetic, environmental, cultural, and ethnic correlates.

Long-term recovery. Recently, three studies of American populations diagnosed with schizophrenia detected trends toward long-term (>5 years) recovery.

U.S. populations. Modestin et al8 in 2003 re-evaluated diagnoses of 208 patients in Swiss psychiatrist Manfred Bleuler’s influential 1972 study on schizophrenia’s long-term course. Using DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) criteria, the authors excluded about 30% of the original patients (most rediagnosed with schizoaffective disorder). Among those remaining, 12% to 15% showed long-term recovery and one-half had an undulating course with remissions.

In 1997, Stephens et al9 examined hospital records from 1913 to 1940 of 484 patients, mean age 27, hospitalized with schizophrenia. Using >5 years of follow-up data and DSM-IV criteria, the authors rated 13% as recovered and 58% unimproved.

Also in 1997, Harrow et al10 evaluated 74 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia by DSM-IV criteria at 2, 4.5, and 7.5 years. In this longitudinal study, one-third (32%) showed complete remission at one follow-up session, compared with 5% at all three evaluations.

This study suggested that schizophrenia patients show relatively poor functioning, compared with other psychotic patients. Over time, however, the likelihood of long-term remission appeared to increase. A similar pattern was seen in a sample of 658 Americans age >65 with schizophrenia diagnosed by DSM-III criteria. As these patients aged, 15% developed long-lasting remission.11

Elsewhere, empirical findings across 15 years from three Norwegian studies indicate that lasting recovery from schizophrenia—with symptom improvement and psychosocial adjustment—is rare (3% to 5% of patients).3 Similarly, only 4% of a Scandinavian sample of 301 patients attained complete, long-term remission during 3 to 39 years of follow-up.12

Across cultures, an international study13 evaluated 15- and 25-year outcomes in 1,633 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Approximately 50% had favorable outcomes—stable work, independent from support, no imprisonment, no substance abuse, no rehospitalization, improved social life—but heterogeneity was marked.

Ms J, 48, is in recovery from schizophrenia. She has a stable job as a Web designer, is married, and has learned to build and maintain social relationships. Much of her life, however, has been very different.

At age 15 she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid psychotic type, with occasional comorbid bipolar symptoms. Over the next 20 years, she was admitted to psychiatric hospitals six times for treatment. At age 36, she was hospitalized with psychosis, depressive symptoms, and insomnia. At that point, she was taking carbamazepine, 500 mg/d, for mood stabilization, and haloperidol, 50 mg/d.

Changing medications. Her psychiatriststarted olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and tapered off haloperidol, which appeared to be gradually becoming less effective while causing mood-related side effects. Ms. J’s psychosis persisted, however, with no response to olanzapine.

Her psychiatrist then tapered carbamazepine to 175 mg/d while starting lamotrigine, 150 to 300 mg/d. The rationale for switching mood stabilizers was that lamotrigine may be more effective than carbamazepine in controlling mixed bipolar states, provide a greater antidepressant effect, and cause fewer side effects.

Intensive treatment. Within 10 days, Ms J’s thought form and composition improved, and her psychiatrist immediately started psychotherapy and psychosocial guidance. Carbamazepine was withdrawn 3 months later, but Ms. J remained on olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 300 mg/d. With these medications, the paranoid psychosis went into remission.

After 5 months of intensive treatment, Ms. J was discharged. Outpatient treatment included weekly psychotherapy plus psychosocial guidance and social and coping training 6 times per month. These therapies —along with olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and carbamazepine, 300 mg/d—continue today.

Ms. J’s mental and emotional condition stabilized, and her cognitive abilities improved. Education and therapy helped reduce stress within her family. She has not been rehospitalized or suffered a serious relapse in 12 years.

Table 2

Psychosocial interventions for patients in recovery from schizophrenia*

|

| * Psychosocial interventions are most effective when combined with antipsychotic therapy and individualized psychotherapy |

Short-term course predicted long-term outcome, and local environment played a significant role in determining symptoms and social disability. The authors concluded that adequate early treatment and an optimum environment might lead to favorable long-term outcome.

In the United Kingdom, 14% of a sample of patients diagnosed by ICD-10 criteria achieved remission across a mean 8.5 years.14 In a study of Czechoslovakian patients (70 men, 50 women) with early-onset schizophrenia diagnosed by DSM-III-R criteria, 10% recovered during 13 to 42 years of follow-up.15

Short-term recovery. The McLean-Harvard first-episode project examined outcomes 6 months after schizophrenia diagnosis in 102 patients (55 men, 47 women). Sixty-five percent attained syndromal recovery (significant reduction of diagnostic features), whereas only 33% achieved functional recovery (increased social-emotional, vocational, and coping abilities).16

In Japan, 62 patients (33 men, 29 women; mean age 25) were followed for 13 years after a first hospitalization for schizophrenia. The authors reported an undulating course with recovery or a mild end-state in 53%, and a simple course of recovery and a moderate or severe end-state in 28%.17

Conclusions. The evidence suggests that early and lasting treatment of schizophrenic symptoms—even in recovered patients—might prevent frequent rehospitalizations. Thus, patients with schizophrenia must be followed carefully during and after recovery. Health care professionals, colleagues, friends, and relatives can help patients sustain recovery by watching for the earliest signs of deterioration and intervening before relapse occurs.

Strategies for recovery

Therapeutic factors. Many studies suggest psychosocial interventions (Table 2), psychotherapy, and medication are most effective in combination for stabilizing patients with schizophrenia and continuing their recovery. Other patient factors that may contribute to recovery include:

- quality of relationships with family, friends, and professional caregivers

- ability and motivation to use resources and take responsibility for one’s life

- spiritual and religious activities

- awareness that recovery is possible.

Sells et al18 noted that attempting to make new contacts outside of their former spheres (“positive withdrawal”) may allow schizophrenia patients to reconsider and ultimately recover a durable sense of self.

We at the W. Kahn Institute19 find that all these treatment strategies may be useful and even necessary to continue and stabilize recovery from schizophrenia. We feel they merit the attention of all professionals involved in recovered patients’ aftercare and guidance.

Table 3

Suggested antipsychotic dosages during schizophrenia recovery*

| Drug | Dosage (mg/d) | Potential side effects | Positive effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | 10 to 30 | Headache, anxiety, insomnia, lightheadedness | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Clozapine | 300 to 900 | Withdrawal, blunted emotions, seizures, lack of motivation | Reduced positive symptoms |

| Haloperidol | 30 to 100 | Tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonian symptoms, insomnia, depressive reactions, confusion, drowsiness, hypertension | Reduced mania, hyperactivity, agitation |

| Olanzapine | 5 to 10 | Drowsiness, agitation, weight gain, involuntary movements, restlessness | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Quetiapine | 25 to 100 | Dizziness, hypotension, increased cholesterol, weight gain | Reduced positive symptoms |

| Risperidone | 2.5 to 5 | Anxiety, nervousness, back pain, bleeding, dizziness, irregular blood pressure | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Ziprasidone | 10 to 200 | Heart-rhythm irregularity, loss of consciousness, restlessness, weakness, drowsiness | Reduced positive symptoms |

| * Dosages are individualized and may vary among patients and situations, but most will be gradually reduced to minimum levels during remission. | |||

Social/vocational network. Family, friends, neighbors, and social workers play an important role in the patient’s development during recovery. They provide positive stimulation (such as physical activities and social or vocational engagements) and support.

To equip the patient’s network for this responsible task, provide them with training (such as in acceptance, empathy, feedback, and communication), education, and guidance. Support groups can enhance the social networks of patients whose own networks are too small to prevent social isolation or overburdening of members.

Vocational training and mediation also may be stabilizing. Religious activities are central to self-understanding and recovery for many psychiatric patients and may improve outcomes.20

Patient skills. To achieve stabilization and continue their recovery, patients must develop social interaction skills and coping strategies. Conversation training, for example, seems to help improve social interaction. Patients in remission must learn to:

- find or create low-stress, positively stimulating environments in which their recovery can flourish

- tolerate discomfort and stress

- overcome internalized stigma about recovery.

Patients also need to learn when and how to withdraw from hectic, stressful environments and from people who are overly emotional, patronizing, or hold unrealistic expectations about them.

Pharmacotherapy. Sound pharmacotherapy underlies rehabilitation and psychosocial treatment of patients in remission from schizophrenia.21 Healthy neurobiological functioning and equilibrium may help normalize social-emotional behavior and create opportunities to improve all life dimensions via psychotherapy, psychosocial guidance, education, and training.

Dosages often can be reduced during recovery, titrating gradually downward to reduce the risk of relapse. Suggested antipsychotic dosages during recovery are listed in Table 3. Be patient and consistent when adjusting dosages, guided by information in package inserts, from clinical trials, and in recent articles on specific medications. When introducing a medication, start with the lowest dosage and increase in small steps until symptoms are reduced and side effects are minimal.

Discontinuing antipsychotics. Is it therapeutically reasonable to discontinue antipsychotics after recovery? Probably not.

Relapse rates in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia appear extremely high—perhaps 8 or 9 out of 10 cases—even during remission. By comparison, relapse rates appear very low—perhaps 3 or 4 out of 10 cases—for remitted patients who remain on antipsychotics. Atypical antipsychotics or low doses of conventional agents are generally well-tolerated and safe in the long term.22

Patient monitoring. Patients in remission from schizophrenia benefit from:

- 24-hour phone lines to call for guidance, treatment, and quick interventions

- central, alert treatment coordination among psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, therapists, vocational experts, and activity counselors.

Psychiatrists in solo or small-group settings may need to seek out these resources in their communities. The goal of this team approach—in cooperation with the patient’s social network—is to help the patient develop employment and social activities appropriate to his or her needs and capabilities.

Related resources

- Ascher-Svanuw H, Kraus A. Psychoeducational groups for patients with schizophrenia: a guide for practitioners. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 1991.

- Suzuki T, Uchida H, Tanaka KF, et al. Revising polypharmacy to a single antipsychotic regimen for patients with chronic schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004;7(2):133-42.

- American Psychiatric Association. Schizophrenia (patient/family information). www.psych.org/public_info/schizo.cfm

- Schizophrenia.com. Nonprofit Web community providing information, support, and education. www.schizophrenia.com

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

Is it realistic for patients with schizophrenia to believe they can recover? Recent observational studies show that some do,1 even though all DSM editions have defined schizophrenia as a chronic disease with a poor outcome.2

Our understanding of schizophrenia is changing as we gain new insights into:

- mechanism of recovery

- efficacy of combined psychotherapeutic, psychosocial, and drug therapies for sustaining remission and recovery

- the value of long-term aftercare. This article examines evidence on:

- achieving recovery from schizophrenia

- factors associated with remission

- treatments that may help prevent relapse and lead to stable, lasting recovery.

What is ‘recovery’?

Diagnostic criteria. Recovery from schizophrenia has social, occupational, symptomatic, and psychostructural dimensions. For clinical practice, Liberman et al3 developed a useful set of 10 criteria for recovery (Table 1) by analyzing the literature and cases of 23 schizophrenia patients who returned to work or school with their symptoms under control.

Table 1

Recovery from schizophrenia: 10 clinical criteria

| Criteria | Characteristics of recovered patients* |

|---|---|

| Family relationships | 70% reported good or very good family relationships |

| Substance abuse | None reported illicit drug use in the past year, and two reported occasional alcohol consumption |

| Duration of untreated psychosis | Only 13% reported >1 year delay between symptom onset and treatment |

| Initial response to medication | 87% reported effective symptom control with their first antipsychotic medication |

| Adherence to treatment | All reported adherence to psychiatric care and medication regimens |

| Supportive therapy | 91% reported ongoing psychotherapy, and 78% reported that accessible and supportive psychiatrists and therapists aided their recovery |

| Cognitive abilities | Normal or near-normal functioning on tests of flexibility in solving problems, verbal working memory, and perceptual skills |

| Social skills | None showed more than very mild negative symptoms |

| Personal history | 70% graduated from college, 13% completed 2 years of college, and 3 of remaining 4 worked full time before becoming ill |

| Access to care | 91% received antipsychotics and psychotherapy, 48% social skills training, 57% family participation, 26% vocational rehabilitation, and 61% self-help groups |

| * Based on a study of 23 schizophrenia patients who returned to work or school with their symptoms under control. | |

| Source: Reference 3 | |

Recovery is not a smooth, linear progression. Even when patients attain remission, they often find it hard to make up for “lost life” during years of disability.4 Recovery also can be defined as social, emotional, and biological maturation. This definition considers recovery not as an end-state or cure but as a process of personal growth.5

Several groups proposed recently that recovery from schizophrenia includes four processes:

- finding hope

- re-establishing identity

- taking responsibility for recovery

- finding meaning6 and “getting on with life”7 (Box).

Long-tem vs short-term

Recovery has been studied in many populations, but the evidence is difficult to compare. Data quality is compromised by poorly-defined cohorts, weak study designs, and lack of clear definitions of recovery and its diagnostic criteria. Moreover, empirical evidence is lacking on recovery’s multidimensional nature, including psychosocial, biochemical, genetic, environmental, cultural, and ethnic correlates.

Long-term recovery. Recently, three studies of American populations diagnosed with schizophrenia detected trends toward long-term (>5 years) recovery.

U.S. populations. Modestin et al8 in 2003 re-evaluated diagnoses of 208 patients in Swiss psychiatrist Manfred Bleuler’s influential 1972 study on schizophrenia’s long-term course. Using DSM-III-R, DSM-IV, and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD-10) criteria, the authors excluded about 30% of the original patients (most rediagnosed with schizoaffective disorder). Among those remaining, 12% to 15% showed long-term recovery and one-half had an undulating course with remissions.

In 1997, Stephens et al9 examined hospital records from 1913 to 1940 of 484 patients, mean age 27, hospitalized with schizophrenia. Using >5 years of follow-up data and DSM-IV criteria, the authors rated 13% as recovered and 58% unimproved.

Also in 1997, Harrow et al10 evaluated 74 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia by DSM-IV criteria at 2, 4.5, and 7.5 years. In this longitudinal study, one-third (32%) showed complete remission at one follow-up session, compared with 5% at all three evaluations.

This study suggested that schizophrenia patients show relatively poor functioning, compared with other psychotic patients. Over time, however, the likelihood of long-term remission appeared to increase. A similar pattern was seen in a sample of 658 Americans age >65 with schizophrenia diagnosed by DSM-III criteria. As these patients aged, 15% developed long-lasting remission.11

Elsewhere, empirical findings across 15 years from three Norwegian studies indicate that lasting recovery from schizophrenia—with symptom improvement and psychosocial adjustment—is rare (3% to 5% of patients).3 Similarly, only 4% of a Scandinavian sample of 301 patients attained complete, long-term remission during 3 to 39 years of follow-up.12

Across cultures, an international study13 evaluated 15- and 25-year outcomes in 1,633 patients diagnosed with schizophrenia. Approximately 50% had favorable outcomes—stable work, independent from support, no imprisonment, no substance abuse, no rehospitalization, improved social life—but heterogeneity was marked.

Ms J, 48, is in recovery from schizophrenia. She has a stable job as a Web designer, is married, and has learned to build and maintain social relationships. Much of her life, however, has been very different.

At age 15 she was diagnosed with schizophrenia, paranoid psychotic type, with occasional comorbid bipolar symptoms. Over the next 20 years, she was admitted to psychiatric hospitals six times for treatment. At age 36, she was hospitalized with psychosis, depressive symptoms, and insomnia. At that point, she was taking carbamazepine, 500 mg/d, for mood stabilization, and haloperidol, 50 mg/d.

Changing medications. Her psychiatriststarted olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and tapered off haloperidol, which appeared to be gradually becoming less effective while causing mood-related side effects. Ms. J’s psychosis persisted, however, with no response to olanzapine.

Her psychiatrist then tapered carbamazepine to 175 mg/d while starting lamotrigine, 150 to 300 mg/d. The rationale for switching mood stabilizers was that lamotrigine may be more effective than carbamazepine in controlling mixed bipolar states, provide a greater antidepressant effect, and cause fewer side effects.

Intensive treatment. Within 10 days, Ms J’s thought form and composition improved, and her psychiatrist immediately started psychotherapy and psychosocial guidance. Carbamazepine was withdrawn 3 months later, but Ms. J remained on olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and lamotrigine, 300 mg/d. With these medications, the paranoid psychosis went into remission.

After 5 months of intensive treatment, Ms. J was discharged. Outpatient treatment included weekly psychotherapy plus psychosocial guidance and social and coping training 6 times per month. These therapies —along with olanzapine, 5 mg/d, and carbamazepine, 300 mg/d—continue today.

Ms. J’s mental and emotional condition stabilized, and her cognitive abilities improved. Education and therapy helped reduce stress within her family. She has not been rehospitalized or suffered a serious relapse in 12 years.

Table 2

Psychosocial interventions for patients in recovery from schizophrenia*

|

| * Psychosocial interventions are most effective when combined with antipsychotic therapy and individualized psychotherapy |

Short-term course predicted long-term outcome, and local environment played a significant role in determining symptoms and social disability. The authors concluded that adequate early treatment and an optimum environment might lead to favorable long-term outcome.

In the United Kingdom, 14% of a sample of patients diagnosed by ICD-10 criteria achieved remission across a mean 8.5 years.14 In a study of Czechoslovakian patients (70 men, 50 women) with early-onset schizophrenia diagnosed by DSM-III-R criteria, 10% recovered during 13 to 42 years of follow-up.15

Short-term recovery. The McLean-Harvard first-episode project examined outcomes 6 months after schizophrenia diagnosis in 102 patients (55 men, 47 women). Sixty-five percent attained syndromal recovery (significant reduction of diagnostic features), whereas only 33% achieved functional recovery (increased social-emotional, vocational, and coping abilities).16

In Japan, 62 patients (33 men, 29 women; mean age 25) were followed for 13 years after a first hospitalization for schizophrenia. The authors reported an undulating course with recovery or a mild end-state in 53%, and a simple course of recovery and a moderate or severe end-state in 28%.17

Conclusions. The evidence suggests that early and lasting treatment of schizophrenic symptoms—even in recovered patients—might prevent frequent rehospitalizations. Thus, patients with schizophrenia must be followed carefully during and after recovery. Health care professionals, colleagues, friends, and relatives can help patients sustain recovery by watching for the earliest signs of deterioration and intervening before relapse occurs.

Strategies for recovery

Therapeutic factors. Many studies suggest psychosocial interventions (Table 2), psychotherapy, and medication are most effective in combination for stabilizing patients with schizophrenia and continuing their recovery. Other patient factors that may contribute to recovery include:

- quality of relationships with family, friends, and professional caregivers

- ability and motivation to use resources and take responsibility for one’s life

- spiritual and religious activities

- awareness that recovery is possible.

Sells et al18 noted that attempting to make new contacts outside of their former spheres (“positive withdrawal”) may allow schizophrenia patients to reconsider and ultimately recover a durable sense of self.

We at the W. Kahn Institute19 find that all these treatment strategies may be useful and even necessary to continue and stabilize recovery from schizophrenia. We feel they merit the attention of all professionals involved in recovered patients’ aftercare and guidance.

Table 3

Suggested antipsychotic dosages during schizophrenia recovery*

| Drug | Dosage (mg/d) | Potential side effects | Positive effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aripiprazole | 10 to 30 | Headache, anxiety, insomnia, lightheadedness | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Clozapine | 300 to 900 | Withdrawal, blunted emotions, seizures, lack of motivation | Reduced positive symptoms |

| Haloperidol | 30 to 100 | Tardive dyskinesia, parkinsonian symptoms, insomnia, depressive reactions, confusion, drowsiness, hypertension | Reduced mania, hyperactivity, agitation |

| Olanzapine | 5 to 10 | Drowsiness, agitation, weight gain, involuntary movements, restlessness | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Quetiapine | 25 to 100 | Dizziness, hypotension, increased cholesterol, weight gain | Reduced positive symptoms |

| Risperidone | 2.5 to 5 | Anxiety, nervousness, back pain, bleeding, dizziness, irregular blood pressure | Reduced positive, negative symptoms |

| Ziprasidone | 10 to 200 | Heart-rhythm irregularity, loss of consciousness, restlessness, weakness, drowsiness | Reduced positive symptoms |

| * Dosages are individualized and may vary among patients and situations, but most will be gradually reduced to minimum levels during remission. | |||

Social/vocational network. Family, friends, neighbors, and social workers play an important role in the patient’s development during recovery. They provide positive stimulation (such as physical activities and social or vocational engagements) and support.

To equip the patient’s network for this responsible task, provide them with training (such as in acceptance, empathy, feedback, and communication), education, and guidance. Support groups can enhance the social networks of patients whose own networks are too small to prevent social isolation or overburdening of members.

Vocational training and mediation also may be stabilizing. Religious activities are central to self-understanding and recovery for many psychiatric patients and may improve outcomes.20

Patient skills. To achieve stabilization and continue their recovery, patients must develop social interaction skills and coping strategies. Conversation training, for example, seems to help improve social interaction. Patients in remission must learn to:

- find or create low-stress, positively stimulating environments in which their recovery can flourish

- tolerate discomfort and stress

- overcome internalized stigma about recovery.

Patients also need to learn when and how to withdraw from hectic, stressful environments and from people who are overly emotional, patronizing, or hold unrealistic expectations about them.

Pharmacotherapy. Sound pharmacotherapy underlies rehabilitation and psychosocial treatment of patients in remission from schizophrenia.21 Healthy neurobiological functioning and equilibrium may help normalize social-emotional behavior and create opportunities to improve all life dimensions via psychotherapy, psychosocial guidance, education, and training.

Dosages often can be reduced during recovery, titrating gradually downward to reduce the risk of relapse. Suggested antipsychotic dosages during recovery are listed in Table 3. Be patient and consistent when adjusting dosages, guided by information in package inserts, from clinical trials, and in recent articles on specific medications. When introducing a medication, start with the lowest dosage and increase in small steps until symptoms are reduced and side effects are minimal.

Discontinuing antipsychotics. Is it therapeutically reasonable to discontinue antipsychotics after recovery? Probably not.

Relapse rates in unmedicated patients with schizophrenia appear extremely high—perhaps 8 or 9 out of 10 cases—even during remission. By comparison, relapse rates appear very low—perhaps 3 or 4 out of 10 cases—for remitted patients who remain on antipsychotics. Atypical antipsychotics or low doses of conventional agents are generally well-tolerated and safe in the long term.22

Patient monitoring. Patients in remission from schizophrenia benefit from:

- 24-hour phone lines to call for guidance, treatment, and quick interventions

- central, alert treatment coordination among psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, therapists, vocational experts, and activity counselors.

Psychiatrists in solo or small-group settings may need to seek out these resources in their communities. The goal of this team approach—in cooperation with the patient’s social network—is to help the patient develop employment and social activities appropriate to his or her needs and capabilities.

Related resources

- Ascher-Svanuw H, Kraus A. Psychoeducational groups for patients with schizophrenia: a guide for practitioners. Gaithersburg, MD: Aspen Publishers, 1991.

- Suzuki T, Uchida H, Tanaka KF, et al. Revising polypharmacy to a single antipsychotic regimen for patients with chronic schizophrenia. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol 2004;7(2):133-42.

- American Psychiatric Association. Schizophrenia (patient/family information). www.psych.org/public_info/schizo.cfm

- Schizophrenia.com. Nonprofit Web community providing information, support, and education. www.schizophrenia.com

Drug brand names

- Aripiprazole • Abilify

- Carbamazepine • Tegretol

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Haloperidol • Haldol

- Lamotrigine • Lamictal

- Olanzapine • Zyprexa

- Quetiapine • Seroquel

- Risperidone • Risperdal

- Ziprasidone • Geodon

Disclosure

The author reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Davidson L. Living outside mental illness: qualitative studies of recovery in schizophrenia. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

2. Kruger A. Schizophrenia: Recovery and hope. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2000;24(1):29-37.

3. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):256-72.

4. Torgalsboen AK, Rund BR. Lessons learned from three studies of recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):312-17.

5. Boone EC. A qualitative investigation of the process of recovery in people experiencing schizophrenia. Dissert Abstr Int 1996;57 (5-B):3402.-

6. Andresen R, Oades L, Caputi P. The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003;37(5):586-94.

7. Noordsy D, Torrey W, Mueser K, et al. Recovery from severe mental illness: an interpersonal and functional outcome definition. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):318-26.

8. Modestin J, Huber A, Satirli E, et al. Long-term course of schizophrenic illness: Bleuler’s study reconsidered. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(12):2202-8.

9. Stephens JH, Richard P, McHugh PR. Long-term follow-up of patients hospitalized for schizophrenia, 1913 to1940. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997;185(12):715-21.

10. Harrow M, Sands JR, Silverstein ML, Goldberg JF. Course and outcome for schizophrenia versus other psychotic patients: a longitudinal study. Schizophr Bull 1997;23:287-303.

11. Craig TJ, Bregman Z. Late-onset schizophrenia-like illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36(2):104-7.

12. Opjordsmoen S. Long-term course and outcome in unipolar affective and schizoaffective psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;79(4):317-26.

13. Harris G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

14. Kiriakakis V, Bhatia KP, Quinn NP, Marsden CD. The natural history of tardive dystonia. A long-term follow-up study of 107 cases. Brain 1998;121(Pt 11):2053-66.

15. Mala E. Early onset schizophrenia. Cesk Slov Psychiatry 1993;89(5):259-71.

16. Tohen M, Strakowski SM, Zarate C, et al. The McLean-Harvard first episode project: 6-month symptomatic and functional outcome in affective and non-affective psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48(6):467-76.

17. Kobayashi T. Course types of first admission schizophrenia: A mean 13-year follow back study. Seishin Igaku Clin Psychiatry 2002;44(2):161-8.

18. Sells DJ, Stayner DA, Davidson L. Recovering the self in schizophrenia: An integrative review of qualitative studies. Psychiatr Q. 2004;75(1):87-97.

19. Martens WHJ, Kahn W, Oppenheimer C. Predictors and prevalence of recovery in schizophrenia. W. Kahn Institute of Theoretical Psychiatry and Neuroscience (WKITPN) Publication 36, 2001(5):113-26.

20. Fallot RD. The place of spirituality and religion in mental health services. In: Lamb HR (ed). Best of new directions for mental health services, 1979-2001. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2001:79-88.

21. Kane JM. Long-term treatment of schizophrenia: Moving from a relapse-prevention model to a recovery model. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1384-5.

22. Tauscher-Wisniewski S, Zipursky RB. The role of maintenance pharmacotherapy in achieving recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2002;14(4):284-92.

1. Davidson L. Living outside mental illness: qualitative studies of recovery in schizophrenia. New York: New York University Press, 2003.

2. Kruger A. Schizophrenia: Recovery and hope. Psychiatr Rehabil J 2000;24(1):29-37.

3. Liberman RP, Kopelowicz A, Ventura J, Gutkind D. Operational criteria and factors related to recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):256-72.

4. Torgalsboen AK, Rund BR. Lessons learned from three studies of recovery from schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):312-17.

5. Boone EC. A qualitative investigation of the process of recovery in people experiencing schizophrenia. Dissert Abstr Int 1996;57 (5-B):3402.-

6. Andresen R, Oades L, Caputi P. The experience of recovery from schizophrenia: towards an empirically validated stage model. Aust NZ J Psychiatry 2003;37(5):586-94.

7. Noordsy D, Torrey W, Mueser K, et al. Recovery from severe mental illness: an interpersonal and functional outcome definition. Int Rev Psychiatry 2002;14(4):318-26.

8. Modestin J, Huber A, Satirli E, et al. Long-term course of schizophrenic illness: Bleuler’s study reconsidered. Am J Psychiatry 2003;160(12):2202-8.

9. Stephens JH, Richard P, McHugh PR. Long-term follow-up of patients hospitalized for schizophrenia, 1913 to1940. J Nerv Ment Dis 1997;185(12):715-21.

10. Harrow M, Sands JR, Silverstein ML, Goldberg JF. Course and outcome for schizophrenia versus other psychotic patients: a longitudinal study. Schizophr Bull 1997;23:287-303.

11. Craig TJ, Bregman Z. Late-onset schizophrenia-like illness. J Am Geriatr Soc 1988;36(2):104-7.

12. Opjordsmoen S. Long-term course and outcome in unipolar affective and schizoaffective psychoses. Acta Psychiatr Scand 1989;79(4):317-26.

13. Harris G, Hopper K, Craig T, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: a 15- and 25-year international follow up study. Br J Psychiatry 2001;178:506-17.

14. Kiriakakis V, Bhatia KP, Quinn NP, Marsden CD. The natural history of tardive dystonia. A long-term follow-up study of 107 cases. Brain 1998;121(Pt 11):2053-66.

15. Mala E. Early onset schizophrenia. Cesk Slov Psychiatry 1993;89(5):259-71.

16. Tohen M, Strakowski SM, Zarate C, et al. The McLean-Harvard first episode project: 6-month symptomatic and functional outcome in affective and non-affective psychosis. Biol Psychiatry 2000;48(6):467-76.

17. Kobayashi T. Course types of first admission schizophrenia: A mean 13-year follow back study. Seishin Igaku Clin Psychiatry 2002;44(2):161-8.

18. Sells DJ, Stayner DA, Davidson L. Recovering the self in schizophrenia: An integrative review of qualitative studies. Psychiatr Q. 2004;75(1):87-97.

19. Martens WHJ, Kahn W, Oppenheimer C. Predictors and prevalence of recovery in schizophrenia. W. Kahn Institute of Theoretical Psychiatry and Neuroscience (WKITPN) Publication 36, 2001(5):113-26.

20. Fallot RD. The place of spirituality and religion in mental health services. In: Lamb HR (ed). Best of new directions for mental health services, 1979-2001. San Francisco: Jossey Bass, 2001:79-88.

21. Kane JM. Long-term treatment of schizophrenia: Moving from a relapse-prevention model to a recovery model. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64(11):1384-5.

22. Tauscher-Wisniewski S, Zipursky RB. The role of maintenance pharmacotherapy in achieving recovery from a first episode of schizophrenia. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2002;14(4):284-92.

To upgrade or not to upgrade?

Personal digital assistants (PDA) are in a state of flux. Thanks to a flurry of hardware and operating system improvements over the last 18 months, PDAs that were cutting-edge last year pale in comparison to newer models.

Should you buy a new PDA now, or stick with your current model and wait for still more innovations? This article can help you decide.

Why upgrade?

Pros. Today’s PDAs are more versatile and intuitive. For example, many combination PDA/mobile phones have newer operating systems, more memory, and greater software compatibility than earlier devices.

A frequent PDA user who craves more speed or added features might want to upgrade now. Likewise, users who are constantly on the road might want a new combination PDA/global positioning system.

Cons. PDA operating systems are updated frequently, reflecting continuing improvements in handheld hardware. Microsoft late last year upgraded its Pocket PC operating system and changed its name to Windows Mobile.

Although frequent users will rejoice in the opportunity to do more, others might not want to spend $300 or more to get the latest features—only to see their new device become outmoded in a few months.

Hardware advances

Processors. The processor, the heart of a PDA, has also seen much change. Newer Palm and Pocket PC devices are based on the strongARM microprocessor produced by Intel under the Xscale brand. Each new processor has more speed, better multimedia, an improved camera interface, and lower power consumption than previous processors.

Smartphones, which reached the market in 2002, are geared to physicians who rely mostly on email and calendar functions and have little need for mobile medical information.

A Windows Mobile smartphone typically looks like a mobile phone but has basic Pocket PC capabilities, such as viewing mail, a calendar, to-do list, and notes.

Windows Mobile smartphones, however, are compatible only with smartphone-specific programs, not with general Pocket PC software. This means that drug reference guides, DSM-IV-TR, and other commonly used medical programs cannot be viewed on a smartphone. If you love the idea of a smartphone but want a specialized program, check out www.smartphone.net.

Pocket PC phone. By contrast, the Pocket PC phone looks and works more like a PDA than a phone. Because it is connected to the cellular network, the device has wider Internet access than does a WiFi-enabled Pocket PC3. At 3.5-by-3.5 inches, the screen size is about twice that of the smartphone’s screen. The device also is compatible with all Pocket PC software.

Pocket PC phones typically have more main memory than smartphones. Smartphones are limited to secure digital-based external memory, but Pocket PC phones have infrared and other connectivity options.

Palm-based smartphones can run most Palm software, depending upon operating system compatibility. Previous Palm smartphones were more limited because of an older operating system and lack of external memory cards.

The palmOne Treo 600, based on the new Palm Version 5 operating system, offers an external memory slot, built-in digital camera, and text messaging. palmOne offers a GSM (global system for mobile communication) protocol version for the T-Mobile, Cingular, and AT&T networks, and a CDMA (code-division multiple access) protocol version for the Sprint network.

Operating system improvements

Palm Source has released version 6 of its operating system—code named “Cobalt”—to hardware developers. This versatile new version—with higher resolution, Word and JPEG file support, simultaneous multiple communications, and other features—could reach the market around the winter holiday.

Microsoft has released Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition. With certain devices, the operating system will help users read text or browse the Web by using more of the screen. With larger screen resolutions packed into a smaller area, fonts are smaller and hard to read. Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition provides additional font-size controls to compensate for this change.

The new Windows Mobile version also features a start menu that displays frequently used applications, and WiFi security is improved compared with the previous version.

The future

Tiquit, OQO, and FlipStart plan to release fully operable handheld computers later this year.

These new devices will run on Windows XP and other operating systems and will feature full central processing units, hard disks, liquid crystal display panels, USB connectivity, and built-in QWERTY keyboards. It remains to be seen if these computers will supersede Palm and Windows Mobile PDAs.

Sony’s new Vaio U70 handheld computer, recently released in Japan, is available in the United States via specialty retailers such as dynamism.com.

Personal digital assistants (PDA) are in a state of flux. Thanks to a flurry of hardware and operating system improvements over the last 18 months, PDAs that were cutting-edge last year pale in comparison to newer models.

Should you buy a new PDA now, or stick with your current model and wait for still more innovations? This article can help you decide.

Why upgrade?

Pros. Today’s PDAs are more versatile and intuitive. For example, many combination PDA/mobile phones have newer operating systems, more memory, and greater software compatibility than earlier devices.

A frequent PDA user who craves more speed or added features might want to upgrade now. Likewise, users who are constantly on the road might want a new combination PDA/global positioning system.

Cons. PDA operating systems are updated frequently, reflecting continuing improvements in handheld hardware. Microsoft late last year upgraded its Pocket PC operating system and changed its name to Windows Mobile.

Although frequent users will rejoice in the opportunity to do more, others might not want to spend $300 or more to get the latest features—only to see their new device become outmoded in a few months.

Hardware advances

Processors. The processor, the heart of a PDA, has also seen much change. Newer Palm and Pocket PC devices are based on the strongARM microprocessor produced by Intel under the Xscale brand. Each new processor has more speed, better multimedia, an improved camera interface, and lower power consumption than previous processors.

Smartphones, which reached the market in 2002, are geared to physicians who rely mostly on email and calendar functions and have little need for mobile medical information.

A Windows Mobile smartphone typically looks like a mobile phone but has basic Pocket PC capabilities, such as viewing mail, a calendar, to-do list, and notes.

Windows Mobile smartphones, however, are compatible only with smartphone-specific programs, not with general Pocket PC software. This means that drug reference guides, DSM-IV-TR, and other commonly used medical programs cannot be viewed on a smartphone. If you love the idea of a smartphone but want a specialized program, check out www.smartphone.net.

Pocket PC phone. By contrast, the Pocket PC phone looks and works more like a PDA than a phone. Because it is connected to the cellular network, the device has wider Internet access than does a WiFi-enabled Pocket PC3. At 3.5-by-3.5 inches, the screen size is about twice that of the smartphone’s screen. The device also is compatible with all Pocket PC software.

Pocket PC phones typically have more main memory than smartphones. Smartphones are limited to secure digital-based external memory, but Pocket PC phones have infrared and other connectivity options.

Palm-based smartphones can run most Palm software, depending upon operating system compatibility. Previous Palm smartphones were more limited because of an older operating system and lack of external memory cards.

The palmOne Treo 600, based on the new Palm Version 5 operating system, offers an external memory slot, built-in digital camera, and text messaging. palmOne offers a GSM (global system for mobile communication) protocol version for the T-Mobile, Cingular, and AT&T networks, and a CDMA (code-division multiple access) protocol version for the Sprint network.

Operating system improvements

Palm Source has released version 6 of its operating system—code named “Cobalt”—to hardware developers. This versatile new version—with higher resolution, Word and JPEG file support, simultaneous multiple communications, and other features—could reach the market around the winter holiday.

Microsoft has released Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition. With certain devices, the operating system will help users read text or browse the Web by using more of the screen. With larger screen resolutions packed into a smaller area, fonts are smaller and hard to read. Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition provides additional font-size controls to compensate for this change.

The new Windows Mobile version also features a start menu that displays frequently used applications, and WiFi security is improved compared with the previous version.

The future

Tiquit, OQO, and FlipStart plan to release fully operable handheld computers later this year.

These new devices will run on Windows XP and other operating systems and will feature full central processing units, hard disks, liquid crystal display panels, USB connectivity, and built-in QWERTY keyboards. It remains to be seen if these computers will supersede Palm and Windows Mobile PDAs.

Sony’s new Vaio U70 handheld computer, recently released in Japan, is available in the United States via specialty retailers such as dynamism.com.

Personal digital assistants (PDA) are in a state of flux. Thanks to a flurry of hardware and operating system improvements over the last 18 months, PDAs that were cutting-edge last year pale in comparison to newer models.

Should you buy a new PDA now, or stick with your current model and wait for still more innovations? This article can help you decide.

Why upgrade?

Pros. Today’s PDAs are more versatile and intuitive. For example, many combination PDA/mobile phones have newer operating systems, more memory, and greater software compatibility than earlier devices.

A frequent PDA user who craves more speed or added features might want to upgrade now. Likewise, users who are constantly on the road might want a new combination PDA/global positioning system.

Cons. PDA operating systems are updated frequently, reflecting continuing improvements in handheld hardware. Microsoft late last year upgraded its Pocket PC operating system and changed its name to Windows Mobile.

Although frequent users will rejoice in the opportunity to do more, others might not want to spend $300 or more to get the latest features—only to see their new device become outmoded in a few months.

Hardware advances

Processors. The processor, the heart of a PDA, has also seen much change. Newer Palm and Pocket PC devices are based on the strongARM microprocessor produced by Intel under the Xscale brand. Each new processor has more speed, better multimedia, an improved camera interface, and lower power consumption than previous processors.

Smartphones, which reached the market in 2002, are geared to physicians who rely mostly on email and calendar functions and have little need for mobile medical information.

A Windows Mobile smartphone typically looks like a mobile phone but has basic Pocket PC capabilities, such as viewing mail, a calendar, to-do list, and notes.

Windows Mobile smartphones, however, are compatible only with smartphone-specific programs, not with general Pocket PC software. This means that drug reference guides, DSM-IV-TR, and other commonly used medical programs cannot be viewed on a smartphone. If you love the idea of a smartphone but want a specialized program, check out www.smartphone.net.

Pocket PC phone. By contrast, the Pocket PC phone looks and works more like a PDA than a phone. Because it is connected to the cellular network, the device has wider Internet access than does a WiFi-enabled Pocket PC3. At 3.5-by-3.5 inches, the screen size is about twice that of the smartphone’s screen. The device also is compatible with all Pocket PC software.

Pocket PC phones typically have more main memory than smartphones. Smartphones are limited to secure digital-based external memory, but Pocket PC phones have infrared and other connectivity options.

Palm-based smartphones can run most Palm software, depending upon operating system compatibility. Previous Palm smartphones were more limited because of an older operating system and lack of external memory cards.

The palmOne Treo 600, based on the new Palm Version 5 operating system, offers an external memory slot, built-in digital camera, and text messaging. palmOne offers a GSM (global system for mobile communication) protocol version for the T-Mobile, Cingular, and AT&T networks, and a CDMA (code-division multiple access) protocol version for the Sprint network.

Operating system improvements

Palm Source has released version 6 of its operating system—code named “Cobalt”—to hardware developers. This versatile new version—with higher resolution, Word and JPEG file support, simultaneous multiple communications, and other features—could reach the market around the winter holiday.

Microsoft has released Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition. With certain devices, the operating system will help users read text or browse the Web by using more of the screen. With larger screen resolutions packed into a smaller area, fonts are smaller and hard to read. Windows Mobile 2003 Second Edition provides additional font-size controls to compensate for this change.

The new Windows Mobile version also features a start menu that displays frequently used applications, and WiFi security is improved compared with the previous version.

The future

Tiquit, OQO, and FlipStart plan to release fully operable handheld computers later this year.

These new devices will run on Windows XP and other operating systems and will feature full central processing units, hard disks, liquid crystal display panels, USB connectivity, and built-in QWERTY keyboards. It remains to be seen if these computers will supersede Palm and Windows Mobile PDAs.

Sony’s new Vaio U70 handheld computer, recently released in Japan, is available in the United States via specialty retailers such as dynamism.com.

Bipolar depression dilemma: Continue antidepressants after remission—or not?

Psychiatrists in the trenches are not alone in being unsure how to treat breakthrough bipolar depression. No panelist or other expert attending a recent American College of Neuropsychopharmacology symposium could definitively recommend:

- when to add an antidepressant to mood-stabilizer therapy

- whether to discontinue antidepressants after bipolar depression is stabilized.

Until controlled trials address these issues, we must use limited evidence to treat patients with bipolar depression. To help you meet this challenge, this article offers provisional suggestions based on recent published and unpublished reports.

Evidence for continuing

No published, randomized studies have examined how long to continue antidepressants after bipolar depression has stabilized. Until recently, conventional wisdom has been to discontinue antidepressants as soon as possible because of worries about antidepressant-induced mania. Then two case-controlled studies—one retrospective and one prospective—challenged that assumption.

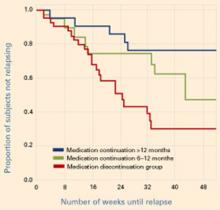

Figure Reduced relapse rates in patients whose antidepressants were continued

In a prospective case-controlled study, patients with bipolar disorder who continued antidepressant treatment for 6 to 12 months or >12 months after depressive episode remission had lower relapse rates than those who discontinued antidepressants within 6 months.