User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Wireless Internet 101

Wireless fidelity, or “Wi-Fi,” is gaining popularity in the medical profession and elsewhere. Some medical professionals are using Wi-Fi’s anytime, anywhere Internet connectivity to access electronic medical information during hospital rounds and to immediately enter demographic information when admitting patients.

What it is-and how it works

Wi-Fi is a certification given by the Wi-Fi Alliance, a nonprofit international trade organization that tests 802.11-based wireless Internet products. The “Wi-Fi Certified” logo signals to purchasers that the product has met rigorous interoperability testing requirements and is compatible with products from different vendors.

Today, the term “Wi-Fi” also commonly describes wireless Internet. Technically speaking, Wi-Fi is the use of radio technology to provide Ethernet connectivity in the unlicensed 2.4 and 5 GHz radio frequencies. By contrast, Internet access provided by wireless modems is based on technology used in cellular phones.

802.11 is the standard protocol ratified by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. 802.11b is the most commonly used standard; 802.11a and 802.11g are other options (Table).

Why Wi-Fi?

Wireless Internet access via the 802.11 protocol offers:

- freedom to surf the Internet in your office, back yard, or elsewhere

- the ability to avoid using unsightly wires to connect computers in a local area network (LAN)

- significantly faster access than wireless modems and higher connection speeds than are available via telephone lines or electrical outlets.

Hitting the hot spots

Aside from office and home, Wi-Fi can be used at “hot spots”-public access points at cafes, restaurants, coffee shops, hotels, airports, downtown business districts, malls, and retail stores. Some retailers provide free access to attract business,1 while others pay to partner with wireless Internet service providers such as T-Mobile 2 and Boingo.3

It helps to check online for hot spots before heading out (visit the T- Mobile or Boingo sites or try the Wi-Fi FreeSpot Directory or other Web site guide). Because most network connections are automatic, however, you can turn on your notebook computer anytime and find out in seconds if a wireless Internet service is available. An indication usually appears on the screen if you are connected to a wireless LAN with Windows XP or Mac OS X, but older operating systems may require additional software. A Wi-Fi signal does not guarantee Internet access because many Wi-Fi providers require the user to log in.

An alternative is to look for ‘warchalking’-a series of sidewalk symbols that appear on your screen to indicate nearby wireless access4 (click here to view warchalking symbols). Warchalking has raised legal and moral issues, though to my knowledge this tracking method is seldom used.

Getting started

Several components are necessary for wireless Internet in the home or office. First, broadband Internet access via a cable modem, digital subscriber line (DSL), or satellite must be established. Connecting via a dial-up modem is another option, but its connection rate is too slow to be shared among several computers.

A wireless access point, which serves as the ‘base station,’ is then connected to the modem. Access points often are sold in combination with a built-in router, which delivers network information to the appropriate destination.

Each computer connecting to the access point must have a wireless network adapter. For desktop computers, this can either be a peripheral component interconnect (PCI) card or a Universal Serial Bus (USB) device. Many notebook computers come with a built-in wireless network adapter but can also use a PCI card or USB device.

Once these devices are installed, the wireless network must be set up so that each device can communicate. Most network setups are automatically established and require little user intervention; however, the user must decide which wireless channel to use and whether a security key is required.

Security risks

Wireless network use poses one major drawback: lack of security.

All wireless LANs have built-in wired equivalent privacy security, which uses a security key to limit access. In 2001, researchers at the University of California at Berkeley discovered flaws in the encryption algorithm designed to protect wireless LANs.5 Software has since been designed to exploit this flaw and identify the security key in the wireless traffic, rendering this level of security useless.6

In health care, this risk raises the issue of whether wireless networking is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Medical Records Institute Executive Director C. Peter Waegeman n indicates that access via 802.11b is clearly not HIPAA-compliant7 and that other standards such as 802.11a or 802.11g should be used. Most healthcare systems, however, continue to use 802.11b because it is widely available and economical.

Making your network secure

Although the 802.11b standard is extremely insecure, several practical issues ameliorate the security risk. For one, finding the security key provides access to the wireless network but does not guarantee access to private information. Disabling shared access to network computers offers additional security but will eliminate the benefit of sharing information over a network.

Several hardware and software innovations aimed at increasing remote network security are scheduled to be launched in the coming weeks.8 Until these products reach the mainstream, you can prevent unauthorized network access by:

- Choosing an access point that restricts media access control (MAC). The MAC address is the hardware address of a node in the network, such as a network adapter. By designating which MAC addresses have wireless access, unauthorized access is eliminated.

- Setting up the access point to stop broadcasting its Service Set Identifier (SSID). The SSID is part of the automated connection process that tells network adapters which 802.11b network it is joining. Only authorized users will know the SSID and security key, which are needed to establish a connection.

Internet communications that implement the secure socket layer (SSL) protocol will be encrypted, thus ensuring that the information is sent, unchanged, only to the intended server. Online shopping sites and banks use SSL technology to safeguard sensitive information.

Table

Current Wi-Fi standards

| Standard | Frequency | Theoretical transmission rate/typical rate (megabytes per second) | Range (meters/feet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 802.11b | 2.4 GHz | 11/4-6 | 30/1000 |

| 802.11a | 5 GHz | 54/20-25 | 25/75 |

| 802.11g (compatible with 802.11b) | 2.4 GHz | 54/6-24 | 30/1000 |

Related Resources

Wi-Fi Alliance: Wi-Fi Overview. Available at: http://www.weca.net/OpenSection/why_Wi-Fi.asp?TID=2. Accessed Nov. 18, 2003

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected].

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

(All URLs accessed Dec. 2, 2003)

1. Wi-Fi FreeSpot Directory. http://www.wififreespot.com/

2. T-Mobile HotSpot. http://www.t-mobile.com/hotspot/default.asp?nav=hm

3. Boingo Wireless: 5,000 HotSpots. http://www.boingo.com

4. Warchalking http://www.warchalking.org

5. Borisov N, Goldberg I, Wagner D. Security of the WEP Algorithm. Available at: http://www.isaac.cs.berkeley.edu/isaac/wep-faq.html

6. AirSnort. http://airsnort.shmoo.com/

7. Wireless networks. Does Wi-Fi Run Afoul of HIPAA? Mobile Health Data Sept. 7, 2003. Available at: http://www.mobilehealthdata.com/article.cfm?articleId=451

8. Nobel C. Wi-Fi to get big extensions. eWeek Dec. 1, 2003. Available at: http://www.eweek.com/article2/0,4149,1400188,00.asp

Wireless fidelity, or “Wi-Fi,” is gaining popularity in the medical profession and elsewhere. Some medical professionals are using Wi-Fi’s anytime, anywhere Internet connectivity to access electronic medical information during hospital rounds and to immediately enter demographic information when admitting patients.

What it is-and how it works

Wi-Fi is a certification given by the Wi-Fi Alliance, a nonprofit international trade organization that tests 802.11-based wireless Internet products. The “Wi-Fi Certified” logo signals to purchasers that the product has met rigorous interoperability testing requirements and is compatible with products from different vendors.

Today, the term “Wi-Fi” also commonly describes wireless Internet. Technically speaking, Wi-Fi is the use of radio technology to provide Ethernet connectivity in the unlicensed 2.4 and 5 GHz radio frequencies. By contrast, Internet access provided by wireless modems is based on technology used in cellular phones.

802.11 is the standard protocol ratified by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. 802.11b is the most commonly used standard; 802.11a and 802.11g are other options (Table).

Why Wi-Fi?

Wireless Internet access via the 802.11 protocol offers:

- freedom to surf the Internet in your office, back yard, or elsewhere

- the ability to avoid using unsightly wires to connect computers in a local area network (LAN)

- significantly faster access than wireless modems and higher connection speeds than are available via telephone lines or electrical outlets.

Hitting the hot spots

Aside from office and home, Wi-Fi can be used at “hot spots”-public access points at cafes, restaurants, coffee shops, hotels, airports, downtown business districts, malls, and retail stores. Some retailers provide free access to attract business,1 while others pay to partner with wireless Internet service providers such as T-Mobile 2 and Boingo.3

It helps to check online for hot spots before heading out (visit the T- Mobile or Boingo sites or try the Wi-Fi FreeSpot Directory or other Web site guide). Because most network connections are automatic, however, you can turn on your notebook computer anytime and find out in seconds if a wireless Internet service is available. An indication usually appears on the screen if you are connected to a wireless LAN with Windows XP or Mac OS X, but older operating systems may require additional software. A Wi-Fi signal does not guarantee Internet access because many Wi-Fi providers require the user to log in.

An alternative is to look for ‘warchalking’-a series of sidewalk symbols that appear on your screen to indicate nearby wireless access4 (click here to view warchalking symbols). Warchalking has raised legal and moral issues, though to my knowledge this tracking method is seldom used.

Getting started

Several components are necessary for wireless Internet in the home or office. First, broadband Internet access via a cable modem, digital subscriber line (DSL), or satellite must be established. Connecting via a dial-up modem is another option, but its connection rate is too slow to be shared among several computers.

A wireless access point, which serves as the ‘base station,’ is then connected to the modem. Access points often are sold in combination with a built-in router, which delivers network information to the appropriate destination.

Each computer connecting to the access point must have a wireless network adapter. For desktop computers, this can either be a peripheral component interconnect (PCI) card or a Universal Serial Bus (USB) device. Many notebook computers come with a built-in wireless network adapter but can also use a PCI card or USB device.

Once these devices are installed, the wireless network must be set up so that each device can communicate. Most network setups are automatically established and require little user intervention; however, the user must decide which wireless channel to use and whether a security key is required.

Security risks

Wireless network use poses one major drawback: lack of security.

All wireless LANs have built-in wired equivalent privacy security, which uses a security key to limit access. In 2001, researchers at the University of California at Berkeley discovered flaws in the encryption algorithm designed to protect wireless LANs.5 Software has since been designed to exploit this flaw and identify the security key in the wireless traffic, rendering this level of security useless.6

In health care, this risk raises the issue of whether wireless networking is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Medical Records Institute Executive Director C. Peter Waegeman n indicates that access via 802.11b is clearly not HIPAA-compliant7 and that other standards such as 802.11a or 802.11g should be used. Most healthcare systems, however, continue to use 802.11b because it is widely available and economical.

Making your network secure

Although the 802.11b standard is extremely insecure, several practical issues ameliorate the security risk. For one, finding the security key provides access to the wireless network but does not guarantee access to private information. Disabling shared access to network computers offers additional security but will eliminate the benefit of sharing information over a network.

Several hardware and software innovations aimed at increasing remote network security are scheduled to be launched in the coming weeks.8 Until these products reach the mainstream, you can prevent unauthorized network access by:

- Choosing an access point that restricts media access control (MAC). The MAC address is the hardware address of a node in the network, such as a network adapter. By designating which MAC addresses have wireless access, unauthorized access is eliminated.

- Setting up the access point to stop broadcasting its Service Set Identifier (SSID). The SSID is part of the automated connection process that tells network adapters which 802.11b network it is joining. Only authorized users will know the SSID and security key, which are needed to establish a connection.

Internet communications that implement the secure socket layer (SSL) protocol will be encrypted, thus ensuring that the information is sent, unchanged, only to the intended server. Online shopping sites and banks use SSL technology to safeguard sensitive information.

Table

Current Wi-Fi standards

| Standard | Frequency | Theoretical transmission rate/typical rate (megabytes per second) | Range (meters/feet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 802.11b | 2.4 GHz | 11/4-6 | 30/1000 |

| 802.11a | 5 GHz | 54/20-25 | 25/75 |

| 802.11g (compatible with 802.11b) | 2.4 GHz | 54/6-24 | 30/1000 |

Related Resources

Wi-Fi Alliance: Wi-Fi Overview. Available at: http://www.weca.net/OpenSection/why_Wi-Fi.asp?TID=2. Accessed Nov. 18, 2003

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected].

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

Wireless fidelity, or “Wi-Fi,” is gaining popularity in the medical profession and elsewhere. Some medical professionals are using Wi-Fi’s anytime, anywhere Internet connectivity to access electronic medical information during hospital rounds and to immediately enter demographic information when admitting patients.

What it is-and how it works

Wi-Fi is a certification given by the Wi-Fi Alliance, a nonprofit international trade organization that tests 802.11-based wireless Internet products. The “Wi-Fi Certified” logo signals to purchasers that the product has met rigorous interoperability testing requirements and is compatible with products from different vendors.

Today, the term “Wi-Fi” also commonly describes wireless Internet. Technically speaking, Wi-Fi is the use of radio technology to provide Ethernet connectivity in the unlicensed 2.4 and 5 GHz radio frequencies. By contrast, Internet access provided by wireless modems is based on technology used in cellular phones.

802.11 is the standard protocol ratified by the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. 802.11b is the most commonly used standard; 802.11a and 802.11g are other options (Table).

Why Wi-Fi?

Wireless Internet access via the 802.11 protocol offers:

- freedom to surf the Internet in your office, back yard, or elsewhere

- the ability to avoid using unsightly wires to connect computers in a local area network (LAN)

- significantly faster access than wireless modems and higher connection speeds than are available via telephone lines or electrical outlets.

Hitting the hot spots

Aside from office and home, Wi-Fi can be used at “hot spots”-public access points at cafes, restaurants, coffee shops, hotels, airports, downtown business districts, malls, and retail stores. Some retailers provide free access to attract business,1 while others pay to partner with wireless Internet service providers such as T-Mobile 2 and Boingo.3

It helps to check online for hot spots before heading out (visit the T- Mobile or Boingo sites or try the Wi-Fi FreeSpot Directory or other Web site guide). Because most network connections are automatic, however, you can turn on your notebook computer anytime and find out in seconds if a wireless Internet service is available. An indication usually appears on the screen if you are connected to a wireless LAN with Windows XP or Mac OS X, but older operating systems may require additional software. A Wi-Fi signal does not guarantee Internet access because many Wi-Fi providers require the user to log in.

An alternative is to look for ‘warchalking’-a series of sidewalk symbols that appear on your screen to indicate nearby wireless access4 (click here to view warchalking symbols). Warchalking has raised legal and moral issues, though to my knowledge this tracking method is seldom used.

Getting started

Several components are necessary for wireless Internet in the home or office. First, broadband Internet access via a cable modem, digital subscriber line (DSL), or satellite must be established. Connecting via a dial-up modem is another option, but its connection rate is too slow to be shared among several computers.

A wireless access point, which serves as the ‘base station,’ is then connected to the modem. Access points often are sold in combination with a built-in router, which delivers network information to the appropriate destination.

Each computer connecting to the access point must have a wireless network adapter. For desktop computers, this can either be a peripheral component interconnect (PCI) card or a Universal Serial Bus (USB) device. Many notebook computers come with a built-in wireless network adapter but can also use a PCI card or USB device.

Once these devices are installed, the wireless network must be set up so that each device can communicate. Most network setups are automatically established and require little user intervention; however, the user must decide which wireless channel to use and whether a security key is required.

Security risks

Wireless network use poses one major drawback: lack of security.

All wireless LANs have built-in wired equivalent privacy security, which uses a security key to limit access. In 2001, researchers at the University of California at Berkeley discovered flaws in the encryption algorithm designed to protect wireless LANs.5 Software has since been designed to exploit this flaw and identify the security key in the wireless traffic, rendering this level of security useless.6

In health care, this risk raises the issue of whether wireless networking is compliant with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA). Medical Records Institute Executive Director C. Peter Waegeman n indicates that access via 802.11b is clearly not HIPAA-compliant7 and that other standards such as 802.11a or 802.11g should be used. Most healthcare systems, however, continue to use 802.11b because it is widely available and economical.

Making your network secure

Although the 802.11b standard is extremely insecure, several practical issues ameliorate the security risk. For one, finding the security key provides access to the wireless network but does not guarantee access to private information. Disabling shared access to network computers offers additional security but will eliminate the benefit of sharing information over a network.

Several hardware and software innovations aimed at increasing remote network security are scheduled to be launched in the coming weeks.8 Until these products reach the mainstream, you can prevent unauthorized network access by:

- Choosing an access point that restricts media access control (MAC). The MAC address is the hardware address of a node in the network, such as a network adapter. By designating which MAC addresses have wireless access, unauthorized access is eliminated.

- Setting up the access point to stop broadcasting its Service Set Identifier (SSID). The SSID is part of the automated connection process that tells network adapters which 802.11b network it is joining. Only authorized users will know the SSID and security key, which are needed to establish a connection.

Internet communications that implement the secure socket layer (SSL) protocol will be encrypted, thus ensuring that the information is sent, unchanged, only to the intended server. Online shopping sites and banks use SSL technology to safeguard sensitive information.

Table

Current Wi-Fi standards

| Standard | Frequency | Theoretical transmission rate/typical rate (megabytes per second) | Range (meters/feet) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 802.11b | 2.4 GHz | 11/4-6 | 30/1000 |

| 802.11a | 5 GHz | 54/20-25 | 25/75 |

| 802.11g (compatible with 802.11b) | 2.4 GHz | 54/6-24 | 30/1000 |

Related Resources

Wi-Fi Alliance: Wi-Fi Overview. Available at: http://www.weca.net/OpenSection/why_Wi-Fi.asp?TID=2. Accessed Nov. 18, 2003

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected].

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

(All URLs accessed Dec. 2, 2003)

1. Wi-Fi FreeSpot Directory. http://www.wififreespot.com/

2. T-Mobile HotSpot. http://www.t-mobile.com/hotspot/default.asp?nav=hm

3. Boingo Wireless: 5,000 HotSpots. http://www.boingo.com

4. Warchalking http://www.warchalking.org

5. Borisov N, Goldberg I, Wagner D. Security of the WEP Algorithm. Available at: http://www.isaac.cs.berkeley.edu/isaac/wep-faq.html

6. AirSnort. http://airsnort.shmoo.com/

7. Wireless networks. Does Wi-Fi Run Afoul of HIPAA? Mobile Health Data Sept. 7, 2003. Available at: http://www.mobilehealthdata.com/article.cfm?articleId=451

8. Nobel C. Wi-Fi to get big extensions. eWeek Dec. 1, 2003. Available at: http://www.eweek.com/article2/0,4149,1400188,00.asp

(All URLs accessed Dec. 2, 2003)

1. Wi-Fi FreeSpot Directory. http://www.wififreespot.com/

2. T-Mobile HotSpot. http://www.t-mobile.com/hotspot/default.asp?nav=hm

3. Boingo Wireless: 5,000 HotSpots. http://www.boingo.com

4. Warchalking http://www.warchalking.org

5. Borisov N, Goldberg I, Wagner D. Security of the WEP Algorithm. Available at: http://www.isaac.cs.berkeley.edu/isaac/wep-faq.html

6. AirSnort. http://airsnort.shmoo.com/

7. Wireless networks. Does Wi-Fi Run Afoul of HIPAA? Mobile Health Data Sept. 7, 2003. Available at: http://www.mobilehealthdata.com/article.cfm?articleId=451

8. Nobel C. Wi-Fi to get big extensions. eWeek Dec. 1, 2003. Available at: http://www.eweek.com/article2/0,4149,1400188,00.asp

How to remedy excessive salivation in patients taking clozapine

Hypersalivation caused by clozapine can lead to sleep deprivation, salivary gland swelling,1 and aspiration pneumonia.2 Its socially stigmatizing effects can also deter patients with psychotic illnesses from taking clozapine.

It is not clear at what dosage clozapine causes sialorrhea, but the higher the dosage the more severe the problem. Hypersalivation usually resolves with continued clozapine therapy. Until that happens, the following agents may help.

Drug management

- Benztropine, an acetylcholine antagonist used in Parkinson’s disease, can be started at 1 mg at night, when hypersalivation is most troublesome. If needed, increase to 2 mg qhs or 1 mg bid. Benztropine can cause dose-dependent anticholinergic effects ranging from peripheral (dry mouth, blurring of vision, tachycardia, urinary retention, constipation) to central (memory disturbance, restlessness, disorientation, delirium).

- Scopolamine, a transdermal used to prevent motion sickness, significantly reduced disabling hypersalivation in patients who wore a 1-mg patch behind the ear for 72 hours.3 The agent may irritate skin, so reserve it for severe cases.

- Terazocin, an alpha 1 receptor antagonist for hypertension, is effective at 2 mg qhs. Because the agent can cause hypotension, start at 1 mg/d for 1 week, then increase the dosage and monitor blood pressure at each visit.

Atropine, ipratropium bromide, and clonidine also have shown benefit in small studies.4-6

Other strategies

Lowering the clozapine dosage while maintaining its antipsychotic effect may also help reduce salivation. You might also advise the patient to:

- suck or chew sugarless candy or gum to increase swallowing

- place a towel on the pillowcase to prevent soaking the pillow overnight.

Drug brand names

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Ipratropium • Atrovent

- Scopolamine • Transderm-Scop

1. Brodkin ES, Pelton GH, Price LH. Treatment of clozapine-induced parotid gland swelling. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:445.-

2. Hinkes R, Quesada TV, Currier MB, et al. Aspiration pneumonia possibly secondary to clozapine induced sialorrhea. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:462-3.

3. McKane JP, Hall C, Akram G. Hyoscine patches in clozapine induced hypersalivation. Psychiatr Bull 2001;25:277.-

4. Antonello C, Tessier P. Clozapine and sialorrhea: a new intervention for this bothersome and potentially dangerous side effect. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1999;24:250.

5. Calderon J, Robin E, Sobota WL. Potential use of ipratropium bromide for the treatment of clozapine induced hypersalivation: a preliminary report. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;15:49-52.

6. Grabowski J. Clonidine treatment of clozapine induced hypersalivation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992;12:69-70.

Dr. Maju Mathews is a resident, department of psychiatry, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Manu Mathews is a staff psychiatrist, East Surrey Hospital, Redhill, UK.

Dr. Joanne Mathews is a staff psychiatrist, West Suffolk Hospital, Bury’s St. Edmonds, UK.

Hypersalivation caused by clozapine can lead to sleep deprivation, salivary gland swelling,1 and aspiration pneumonia.2 Its socially stigmatizing effects can also deter patients with psychotic illnesses from taking clozapine.

It is not clear at what dosage clozapine causes sialorrhea, but the higher the dosage the more severe the problem. Hypersalivation usually resolves with continued clozapine therapy. Until that happens, the following agents may help.

Drug management

- Benztropine, an acetylcholine antagonist used in Parkinson’s disease, can be started at 1 mg at night, when hypersalivation is most troublesome. If needed, increase to 2 mg qhs or 1 mg bid. Benztropine can cause dose-dependent anticholinergic effects ranging from peripheral (dry mouth, blurring of vision, tachycardia, urinary retention, constipation) to central (memory disturbance, restlessness, disorientation, delirium).

- Scopolamine, a transdermal used to prevent motion sickness, significantly reduced disabling hypersalivation in patients who wore a 1-mg patch behind the ear for 72 hours.3 The agent may irritate skin, so reserve it for severe cases.

- Terazocin, an alpha 1 receptor antagonist for hypertension, is effective at 2 mg qhs. Because the agent can cause hypotension, start at 1 mg/d for 1 week, then increase the dosage and monitor blood pressure at each visit.

Atropine, ipratropium bromide, and clonidine also have shown benefit in small studies.4-6

Other strategies

Lowering the clozapine dosage while maintaining its antipsychotic effect may also help reduce salivation. You might also advise the patient to:

- suck or chew sugarless candy or gum to increase swallowing

- place a towel on the pillowcase to prevent soaking the pillow overnight.

Drug brand names

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Ipratropium • Atrovent

- Scopolamine • Transderm-Scop

Hypersalivation caused by clozapine can lead to sleep deprivation, salivary gland swelling,1 and aspiration pneumonia.2 Its socially stigmatizing effects can also deter patients with psychotic illnesses from taking clozapine.

It is not clear at what dosage clozapine causes sialorrhea, but the higher the dosage the more severe the problem. Hypersalivation usually resolves with continued clozapine therapy. Until that happens, the following agents may help.

Drug management

- Benztropine, an acetylcholine antagonist used in Parkinson’s disease, can be started at 1 mg at night, when hypersalivation is most troublesome. If needed, increase to 2 mg qhs or 1 mg bid. Benztropine can cause dose-dependent anticholinergic effects ranging from peripheral (dry mouth, blurring of vision, tachycardia, urinary retention, constipation) to central (memory disturbance, restlessness, disorientation, delirium).

- Scopolamine, a transdermal used to prevent motion sickness, significantly reduced disabling hypersalivation in patients who wore a 1-mg patch behind the ear for 72 hours.3 The agent may irritate skin, so reserve it for severe cases.

- Terazocin, an alpha 1 receptor antagonist for hypertension, is effective at 2 mg qhs. Because the agent can cause hypotension, start at 1 mg/d for 1 week, then increase the dosage and monitor blood pressure at each visit.

Atropine, ipratropium bromide, and clonidine also have shown benefit in small studies.4-6

Other strategies

Lowering the clozapine dosage while maintaining its antipsychotic effect may also help reduce salivation. You might also advise the patient to:

- suck or chew sugarless candy or gum to increase swallowing

- place a towel on the pillowcase to prevent soaking the pillow overnight.

Drug brand names

- Benztropine • Cogentin

- Clonidine • Catapres

- Clozapine • Clozaril

- Ipratropium • Atrovent

- Scopolamine • Transderm-Scop

1. Brodkin ES, Pelton GH, Price LH. Treatment of clozapine-induced parotid gland swelling. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:445.-

2. Hinkes R, Quesada TV, Currier MB, et al. Aspiration pneumonia possibly secondary to clozapine induced sialorrhea. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:462-3.

3. McKane JP, Hall C, Akram G. Hyoscine patches in clozapine induced hypersalivation. Psychiatr Bull 2001;25:277.-

4. Antonello C, Tessier P. Clozapine and sialorrhea: a new intervention for this bothersome and potentially dangerous side effect. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1999;24:250.

5. Calderon J, Robin E, Sobota WL. Potential use of ipratropium bromide for the treatment of clozapine induced hypersalivation: a preliminary report. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;15:49-52.

6. Grabowski J. Clonidine treatment of clozapine induced hypersalivation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992;12:69-70.

Dr. Maju Mathews is a resident, department of psychiatry, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Manu Mathews is a staff psychiatrist, East Surrey Hospital, Redhill, UK.

Dr. Joanne Mathews is a staff psychiatrist, West Suffolk Hospital, Bury’s St. Edmonds, UK.

1. Brodkin ES, Pelton GH, Price LH. Treatment of clozapine-induced parotid gland swelling. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:445.-

2. Hinkes R, Quesada TV, Currier MB, et al. Aspiration pneumonia possibly secondary to clozapine induced sialorrhea. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1996;16:462-3.

3. McKane JP, Hall C, Akram G. Hyoscine patches in clozapine induced hypersalivation. Psychiatr Bull 2001;25:277.-

4. Antonello C, Tessier P. Clozapine and sialorrhea: a new intervention for this bothersome and potentially dangerous side effect. J Psychiatry Neurosci 1999;24:250.

5. Calderon J, Robin E, Sobota WL. Potential use of ipratropium bromide for the treatment of clozapine induced hypersalivation: a preliminary report. Int Clin Psychopharmacol 2000;15:49-52.

6. Grabowski J. Clonidine treatment of clozapine induced hypersalivation. J Clin Psychopharmacol 1992;12:69-70.

Dr. Maju Mathews is a resident, department of psychiatry, Drexel University College of Medicine, Philadelphia, PA.

Dr. Manu Mathews is a staff psychiatrist, East Surrey Hospital, Redhill, UK.

Dr. Joanne Mathews is a staff psychiatrist, West Suffolk Hospital, Bury’s St. Edmonds, UK.

Christmas depression: The data may surprise you

In 1981, I wrote an article called, “Christmas and psychopathology” (Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38[Dec]:1377-81). In the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature, I found 103 magazine articles across 8 years under “Depression, Mental.” Sixteen dealt with Christmas depression.

This week, I did a Google search for “Christmas” (13,700,000 hits) and “depression” (237,000 hits). This weighty body of Web lore suggests that the popular press assumes many people get depressed before Christmas.

Why is there such an interest in Christmas depression? I think it’s because few of us feel as happy as we think we ought to over the holidays. Given the stresses of shopping, family obligations, and emotional baggage from previous years, I’m surprised that more people do not get depressed.

The fact is, however, that fewer people report to psychiatric emergency rooms just before Christmas than at other times of the year. My study in 1981 and most similar studies show that hospital admissions, suicide attempts and completions, and even letters to advice columnists go down just before Christmas, then go back up immediately afterwards. When you average the pre- and post-holiday statistics, Christmas is not one of the busiest seasons for psychiatric emergencies.

Maybe depression doesn’t increase before Christmas because people use their best coping strategies to get through the holiday. And maybe there is a little Christmas magic after all.

In 1981, I wrote an article called, “Christmas and psychopathology” (Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38[Dec]:1377-81). In the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature, I found 103 magazine articles across 8 years under “Depression, Mental.” Sixteen dealt with Christmas depression.

This week, I did a Google search for “Christmas” (13,700,000 hits) and “depression” (237,000 hits). This weighty body of Web lore suggests that the popular press assumes many people get depressed before Christmas.

Why is there such an interest in Christmas depression? I think it’s because few of us feel as happy as we think we ought to over the holidays. Given the stresses of shopping, family obligations, and emotional baggage from previous years, I’m surprised that more people do not get depressed.

The fact is, however, that fewer people report to psychiatric emergency rooms just before Christmas than at other times of the year. My study in 1981 and most similar studies show that hospital admissions, suicide attempts and completions, and even letters to advice columnists go down just before Christmas, then go back up immediately afterwards. When you average the pre- and post-holiday statistics, Christmas is not one of the busiest seasons for psychiatric emergencies.

Maybe depression doesn’t increase before Christmas because people use their best coping strategies to get through the holiday. And maybe there is a little Christmas magic after all.

In 1981, I wrote an article called, “Christmas and psychopathology” (Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38[Dec]:1377-81). In the Readers’ Guide to Periodical Literature, I found 103 magazine articles across 8 years under “Depression, Mental.” Sixteen dealt with Christmas depression.

This week, I did a Google search for “Christmas” (13,700,000 hits) and “depression” (237,000 hits). This weighty body of Web lore suggests that the popular press assumes many people get depressed before Christmas.

Why is there such an interest in Christmas depression? I think it’s because few of us feel as happy as we think we ought to over the holidays. Given the stresses of shopping, family obligations, and emotional baggage from previous years, I’m surprised that more people do not get depressed.

The fact is, however, that fewer people report to psychiatric emergency rooms just before Christmas than at other times of the year. My study in 1981 and most similar studies show that hospital admissions, suicide attempts and completions, and even letters to advice columnists go down just before Christmas, then go back up immediately afterwards. When you average the pre- and post-holiday statistics, Christmas is not one of the busiest seasons for psychiatric emergencies.

Maybe depression doesn’t increase before Christmas because people use their best coping strategies to get through the holiday. And maybe there is a little Christmas magic after all.

Hypochondriasis prevalence

Suzanne Feinstein, PhD, and Brian Fallon, MD, MPH, note that “In psychiatric or medical clinics, women (have) hypochondriasis three to four times more often than menSeptember 2003).

DSM-IV-TR,2 however, reports equal incidence of hypochondriasis in men and women, as do Tasman, Kay & Lieberman.3

Researchers have distinguished between the incidence and prevalence of hypochondriasis in the general and medical populations. DSM-IV-TR places hypochondriasis prevalence at 1 to 5% in the general population and 2 to 7% in the medical population. Martin & Yutzy’s4 estimate of 3 to 13% prevalence in the medical population jibes with Dr. Feinstein’s and Dr. Fallon’s article.

To my knowledge, however, data on hypochondriasis prevalence among psychiatric outpatients are lacking. Extrapolating this information from the general medical population and implying a similar prevalence among psychiatric outpatients may not be correct.

Jessica Bright, MD

Child psychiatry fellow

Department of psychiatry and human behavior

Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed-text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

- Barsky AJ, Wyshak G, Klerman GL, Latham KS. The prevalence of hypochondriasis in medical outpatients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1990;25(2):89–94.

- Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman, JA (eds). Psychiatry, Vol. 2 (1st ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

- Martin RL, Yutzy SH. Somatoform disorders. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA (eds). Psychiatry (1st ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997:1144–8.

Suzanne Feinstein, PhD, and Brian Fallon, MD, MPH, note that “In psychiatric or medical clinics, women (have) hypochondriasis three to four times more often than menSeptember 2003).

DSM-IV-TR,2 however, reports equal incidence of hypochondriasis in men and women, as do Tasman, Kay & Lieberman.3

Researchers have distinguished between the incidence and prevalence of hypochondriasis in the general and medical populations. DSM-IV-TR places hypochondriasis prevalence at 1 to 5% in the general population and 2 to 7% in the medical population. Martin & Yutzy’s4 estimate of 3 to 13% prevalence in the medical population jibes with Dr. Feinstein’s and Dr. Fallon’s article.

To my knowledge, however, data on hypochondriasis prevalence among psychiatric outpatients are lacking. Extrapolating this information from the general medical population and implying a similar prevalence among psychiatric outpatients may not be correct.

Jessica Bright, MD

Child psychiatry fellow

Department of psychiatry and human behavior

Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed-text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

- Barsky AJ, Wyshak G, Klerman GL, Latham KS. The prevalence of hypochondriasis in medical outpatients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1990;25(2):89–94.

- Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman, JA (eds). Psychiatry, Vol. 2 (1st ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

- Martin RL, Yutzy SH. Somatoform disorders. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA (eds). Psychiatry (1st ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997:1144–8.

Suzanne Feinstein, PhD, and Brian Fallon, MD, MPH, note that “In psychiatric or medical clinics, women (have) hypochondriasis three to four times more often than menSeptember 2003).

DSM-IV-TR,2 however, reports equal incidence of hypochondriasis in men and women, as do Tasman, Kay & Lieberman.3

Researchers have distinguished between the incidence and prevalence of hypochondriasis in the general and medical populations. DSM-IV-TR places hypochondriasis prevalence at 1 to 5% in the general population and 2 to 7% in the medical population. Martin & Yutzy’s4 estimate of 3 to 13% prevalence in the medical population jibes with Dr. Feinstein’s and Dr. Fallon’s article.

To my knowledge, however, data on hypochondriasis prevalence among psychiatric outpatients are lacking. Extrapolating this information from the general medical population and implying a similar prevalence among psychiatric outpatients may not be correct.

Jessica Bright, MD

Child psychiatry fellow

Department of psychiatry and human behavior

Thomas Jefferson University, Philadelphia, PA

- Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed-text revision). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association, 2000.

- Barsky AJ, Wyshak G, Klerman GL, Latham KS. The prevalence of hypochondriasis in medical outpatients. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 1990;25(2):89–94.

- Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman, JA (eds). Psychiatry, Vol. 2 (1st ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997.

- Martin RL, Yutzy SH. Somatoform disorders. In: Tasman A, Kay J, Lieberman JA (eds). Psychiatry (1st ed). Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1997:1144–8.

Using lithium in bipolar disorder

“Tips for Using Lithium in Bipolar Disorder” by West B. Magnon, MD, (Pearls, Current Psychiatry, September 2003) had some “do not try this at home” aspects to it.

For example, when Dr. Magnon said “Lithium, 900 mg/d, works fine,” I believe he was referring to 900 mg/d of lithium carbonate, because 900 mg of lithium is equivalent to 4,791 mg of lithium carbonate, a generally toxic dose. Also, to suggest that one dosage fits all flies in the face of decades of research.

More important, to say that “Gauging lithium blood levels is a waste of time, assuming you have checked for kidney disease” is a dangerous statement. Numerous examples exist of lithium toxicity induced by drug interactions or dehydration in patients without kidney disease.

James W. Jefferson, MD

Distinguished senior scientist, Madison Institute of Medicine

Clinical professor of psychiatry,

University of Wisconsin Medical School

Dr. Magnon responds

Dr. Jefferson’s comments reflect the standard thinking about use of lithium carbonate.

My points are:

- I have not seen these so-called extensive studies about lithium toxicity

- When given in reasonable, effective dosages, the patient responds without toxic effects.

Lithium does have some unpleasant side effects, such as tremor, and weight gain is common in some patients, especially women. Continuous lab testing is just not necessary, however.

West B. Magnon, MD Bradenton, FL

“Tips for Using Lithium in Bipolar Disorder” by West B. Magnon, MD, (Pearls, Current Psychiatry, September 2003) had some “do not try this at home” aspects to it.

For example, when Dr. Magnon said “Lithium, 900 mg/d, works fine,” I believe he was referring to 900 mg/d of lithium carbonate, because 900 mg of lithium is equivalent to 4,791 mg of lithium carbonate, a generally toxic dose. Also, to suggest that one dosage fits all flies in the face of decades of research.

More important, to say that “Gauging lithium blood levels is a waste of time, assuming you have checked for kidney disease” is a dangerous statement. Numerous examples exist of lithium toxicity induced by drug interactions or dehydration in patients without kidney disease.

James W. Jefferson, MD

Distinguished senior scientist, Madison Institute of Medicine

Clinical professor of psychiatry,

University of Wisconsin Medical School

Dr. Magnon responds

Dr. Jefferson’s comments reflect the standard thinking about use of lithium carbonate.

My points are:

- I have not seen these so-called extensive studies about lithium toxicity

- When given in reasonable, effective dosages, the patient responds without toxic effects.

Lithium does have some unpleasant side effects, such as tremor, and weight gain is common in some patients, especially women. Continuous lab testing is just not necessary, however.

West B. Magnon, MD Bradenton, FL

“Tips for Using Lithium in Bipolar Disorder” by West B. Magnon, MD, (Pearls, Current Psychiatry, September 2003) had some “do not try this at home” aspects to it.

For example, when Dr. Magnon said “Lithium, 900 mg/d, works fine,” I believe he was referring to 900 mg/d of lithium carbonate, because 900 mg of lithium is equivalent to 4,791 mg of lithium carbonate, a generally toxic dose. Also, to suggest that one dosage fits all flies in the face of decades of research.

More important, to say that “Gauging lithium blood levels is a waste of time, assuming you have checked for kidney disease” is a dangerous statement. Numerous examples exist of lithium toxicity induced by drug interactions or dehydration in patients without kidney disease.

James W. Jefferson, MD

Distinguished senior scientist, Madison Institute of Medicine

Clinical professor of psychiatry,

University of Wisconsin Medical School

Dr. Magnon responds

Dr. Jefferson’s comments reflect the standard thinking about use of lithium carbonate.

My points are:

- I have not seen these so-called extensive studies about lithium toxicity

- When given in reasonable, effective dosages, the patient responds without toxic effects.

Lithium does have some unpleasant side effects, such as tremor, and weight gain is common in some patients, especially women. Continuous lab testing is just not necessary, however.

West B. Magnon, MD Bradenton, FL

Scheduling: Time to take control

Like many doctors, you often feel the need to be two places at once.

The trick is to avoid scheduling two commitments at the same time. Anyone who has had to manage a busy practice schedule and remember his or her child’s soccer practice knows this can be challenging.

If you’re looking to organize your schedule, the Internet or your personal digital assistant (PDA) may hold the answer. This article will review scheduling solutions and help you decide which is right for your practice.

PDA scheduling-pros and cons

Both Palm and Pocket PC devices offer very good scheduling capabilities; your choice of operating system depends upon whether you need to use Microsoft Outlook. In my view, Palm is simpler and more reliable, whereas I have had more trouble connecting a Pocket PC device to my desktop computer.

Keeping a calendar in a handheld computer can be quite handy. Simply pull out the PDA, click once or twice, and view your daily schedule. Used properly, this can help prevent scheduling conflicts.

This feature, however, may be less helpful if your office staff maintains your schedule. For one, no one else can access the PDA while you’re carrying it. Second, if you do not regularly synchronize your PDA to the office computer, the staffer can make in-office schedule changes that are not recorded on the PDA version, possibly leading to double booking.

To prevent such mixups, assign one office assistant to update your schedule, and allow only that staffer to make changes. Also, be sure to double check the schedule before booking an appointment on your own.

Many major personal information managers such as Microsoft Outlook and Lotus Notes can be synchronized to a handheld. This allows your staff to view and simultaneously edit your schedule in the office, which is then synchronized onto the handheld. What’s more, users who cannot access your computer but have the proper privileges to your information can still connect to your schedule.

If a significant other uses a Palm OS device and you need to coordinate your schedule with his or hers, WeSync provides a solution that synchronizes both schedules via an online server and displays them side by side on your Palm OS PDA. Although WeSync no longer provides tech support for it, the software and service (which PalmOne owns) is still available.

Schedule synchronization between Pocket PC users is tricky: It cannot be done via an Internet server because each device has a one-to-one relationship with Microsoft Outlook, the desktop schedule software.

ManyPartners overcomes this limitation by allowing users to connect two Pocket PC devices to the same desktop scheduling software. Both users then must share information on one profile in Microsoft Outlook and must enter information in a way that avoids confusion, such as “John: doctor’s appointment” and “Mary: lecture on Monday.”)

Making your days colorful

Third-party software can make your calendar easier to use by employing color and icons to designate types of appointments (Table). This software also provides quick access to other information, such as task lists and notes.

For Palm OS devices, products such as Agendus, DateBk5, and Beyond Contacts provide a different and enhanced way to view your data. Similar software for the Pocket PC or Windows Mobile 2003 devices include Ulti-Planner, Pocket Informant, and Agenda Fusion and Agenda Today from DeveloperOne.

Some programs use the PDA’s built-in database while others have a proprietary database. This difference is important because it affects your ability to “beam” information from one device to another. For example, a proprietary database can facilitate data exchange, but only if the user to whom you are sending the data also uses a device with a proprietary database.

Online scheduling

Internet-based scheduling programs can also prevent double-booking. The user enters prospective meeting dates into the online form; the software then checks the dates against the calendar for conflicts and selects the best date. These schedules can also be synchronized to a PDA.

One drawback: changes to the online and PDA schedules must be entered separately, creating the potential for double booking. To avoid this:

- assign one staff member to make schedule changes

- or use a wireless PDA or one with a built-in cellular phone to allow instant schedule updates and prevent miscommunication.

Appointmentquest.com and scheduling.com-two services geared toward health care providers-provide online schedules, can handle multiple service locations and personnel, and will generate reminders for patients. Scheduling.com also can track multiple types of insurance and can provide billing systems with patient registration information to generate statements.

Schedule enhancement software options

| SOLUTION | WEBSITE URL | OS | COST |

|---|---|---|---|

| WeSync | www.wesync.com | Palm | Free |

| Beyond Contacts | www.dataviz.com | Palm | $49.95 |

| Agendus | www.iambic.com | Palm | $25.95 standard $39.95 professional |

| DateBK5 | www.pimlicosoftware.com | Palm | $24.95 |

| Agenda Fusion | www.developerone.com | Pocket PC | $29.95 |

| Pocket Informant | www.pocketinformant.com | Pocket PC | $24.95 |

| Ulti-Planner | www.uglybass.com/ultiplanner | Pocket PC | $14.95 |

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected] .

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

Like many doctors, you often feel the need to be two places at once.

The trick is to avoid scheduling two commitments at the same time. Anyone who has had to manage a busy practice schedule and remember his or her child’s soccer practice knows this can be challenging.

If you’re looking to organize your schedule, the Internet or your personal digital assistant (PDA) may hold the answer. This article will review scheduling solutions and help you decide which is right for your practice.

PDA scheduling-pros and cons

Both Palm and Pocket PC devices offer very good scheduling capabilities; your choice of operating system depends upon whether you need to use Microsoft Outlook. In my view, Palm is simpler and more reliable, whereas I have had more trouble connecting a Pocket PC device to my desktop computer.

Keeping a calendar in a handheld computer can be quite handy. Simply pull out the PDA, click once or twice, and view your daily schedule. Used properly, this can help prevent scheduling conflicts.

This feature, however, may be less helpful if your office staff maintains your schedule. For one, no one else can access the PDA while you’re carrying it. Second, if you do not regularly synchronize your PDA to the office computer, the staffer can make in-office schedule changes that are not recorded on the PDA version, possibly leading to double booking.

To prevent such mixups, assign one office assistant to update your schedule, and allow only that staffer to make changes. Also, be sure to double check the schedule before booking an appointment on your own.

Many major personal information managers such as Microsoft Outlook and Lotus Notes can be synchronized to a handheld. This allows your staff to view and simultaneously edit your schedule in the office, which is then synchronized onto the handheld. What’s more, users who cannot access your computer but have the proper privileges to your information can still connect to your schedule.

If a significant other uses a Palm OS device and you need to coordinate your schedule with his or hers, WeSync provides a solution that synchronizes both schedules via an online server and displays them side by side on your Palm OS PDA. Although WeSync no longer provides tech support for it, the software and service (which PalmOne owns) is still available.

Schedule synchronization between Pocket PC users is tricky: It cannot be done via an Internet server because each device has a one-to-one relationship with Microsoft Outlook, the desktop schedule software.

ManyPartners overcomes this limitation by allowing users to connect two Pocket PC devices to the same desktop scheduling software. Both users then must share information on one profile in Microsoft Outlook and must enter information in a way that avoids confusion, such as “John: doctor’s appointment” and “Mary: lecture on Monday.”)

Making your days colorful

Third-party software can make your calendar easier to use by employing color and icons to designate types of appointments (Table). This software also provides quick access to other information, such as task lists and notes.

For Palm OS devices, products such as Agendus, DateBk5, and Beyond Contacts provide a different and enhanced way to view your data. Similar software for the Pocket PC or Windows Mobile 2003 devices include Ulti-Planner, Pocket Informant, and Agenda Fusion and Agenda Today from DeveloperOne.

Some programs use the PDA’s built-in database while others have a proprietary database. This difference is important because it affects your ability to “beam” information from one device to another. For example, a proprietary database can facilitate data exchange, but only if the user to whom you are sending the data also uses a device with a proprietary database.

Online scheduling

Internet-based scheduling programs can also prevent double-booking. The user enters prospective meeting dates into the online form; the software then checks the dates against the calendar for conflicts and selects the best date. These schedules can also be synchronized to a PDA.

One drawback: changes to the online and PDA schedules must be entered separately, creating the potential for double booking. To avoid this:

- assign one staff member to make schedule changes

- or use a wireless PDA or one with a built-in cellular phone to allow instant schedule updates and prevent miscommunication.

Appointmentquest.com and scheduling.com-two services geared toward health care providers-provide online schedules, can handle multiple service locations and personnel, and will generate reminders for patients. Scheduling.com also can track multiple types of insurance and can provide billing systems with patient registration information to generate statements.

Schedule enhancement software options

| SOLUTION | WEBSITE URL | OS | COST |

|---|---|---|---|

| WeSync | www.wesync.com | Palm | Free |

| Beyond Contacts | www.dataviz.com | Palm | $49.95 |

| Agendus | www.iambic.com | Palm | $25.95 standard $39.95 professional |

| DateBK5 | www.pimlicosoftware.com | Palm | $24.95 |

| Agenda Fusion | www.developerone.com | Pocket PC | $29.95 |

| Pocket Informant | www.pocketinformant.com | Pocket PC | $24.95 |

| Ulti-Planner | www.uglybass.com/ultiplanner | Pocket PC | $14.95 |

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected] .

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

Like many doctors, you often feel the need to be two places at once.

The trick is to avoid scheduling two commitments at the same time. Anyone who has had to manage a busy practice schedule and remember his or her child’s soccer practice knows this can be challenging.

If you’re looking to organize your schedule, the Internet or your personal digital assistant (PDA) may hold the answer. This article will review scheduling solutions and help you decide which is right for your practice.

PDA scheduling-pros and cons

Both Palm and Pocket PC devices offer very good scheduling capabilities; your choice of operating system depends upon whether you need to use Microsoft Outlook. In my view, Palm is simpler and more reliable, whereas I have had more trouble connecting a Pocket PC device to my desktop computer.

Keeping a calendar in a handheld computer can be quite handy. Simply pull out the PDA, click once or twice, and view your daily schedule. Used properly, this can help prevent scheduling conflicts.

This feature, however, may be less helpful if your office staff maintains your schedule. For one, no one else can access the PDA while you’re carrying it. Second, if you do not regularly synchronize your PDA to the office computer, the staffer can make in-office schedule changes that are not recorded on the PDA version, possibly leading to double booking.

To prevent such mixups, assign one office assistant to update your schedule, and allow only that staffer to make changes. Also, be sure to double check the schedule before booking an appointment on your own.

Many major personal information managers such as Microsoft Outlook and Lotus Notes can be synchronized to a handheld. This allows your staff to view and simultaneously edit your schedule in the office, which is then synchronized onto the handheld. What’s more, users who cannot access your computer but have the proper privileges to your information can still connect to your schedule.

If a significant other uses a Palm OS device and you need to coordinate your schedule with his or hers, WeSync provides a solution that synchronizes both schedules via an online server and displays them side by side on your Palm OS PDA. Although WeSync no longer provides tech support for it, the software and service (which PalmOne owns) is still available.

Schedule synchronization between Pocket PC users is tricky: It cannot be done via an Internet server because each device has a one-to-one relationship with Microsoft Outlook, the desktop schedule software.

ManyPartners overcomes this limitation by allowing users to connect two Pocket PC devices to the same desktop scheduling software. Both users then must share information on one profile in Microsoft Outlook and must enter information in a way that avoids confusion, such as “John: doctor’s appointment” and “Mary: lecture on Monday.”)

Making your days colorful

Third-party software can make your calendar easier to use by employing color and icons to designate types of appointments (Table). This software also provides quick access to other information, such as task lists and notes.

For Palm OS devices, products such as Agendus, DateBk5, and Beyond Contacts provide a different and enhanced way to view your data. Similar software for the Pocket PC or Windows Mobile 2003 devices include Ulti-Planner, Pocket Informant, and Agenda Fusion and Agenda Today from DeveloperOne.

Some programs use the PDA’s built-in database while others have a proprietary database. This difference is important because it affects your ability to “beam” information from one device to another. For example, a proprietary database can facilitate data exchange, but only if the user to whom you are sending the data also uses a device with a proprietary database.

Online scheduling

Internet-based scheduling programs can also prevent double-booking. The user enters prospective meeting dates into the online form; the software then checks the dates against the calendar for conflicts and selects the best date. These schedules can also be synchronized to a PDA.

One drawback: changes to the online and PDA schedules must be entered separately, creating the potential for double booking. To avoid this:

- assign one staff member to make schedule changes

- or use a wireless PDA or one with a built-in cellular phone to allow instant schedule updates and prevent miscommunication.

Appointmentquest.com and scheduling.com-two services geared toward health care providers-provide online schedules, can handle multiple service locations and personnel, and will generate reminders for patients. Scheduling.com also can track multiple types of insurance and can provide billing systems with patient registration information to generate statements.

Schedule enhancement software options

| SOLUTION | WEBSITE URL | OS | COST |

|---|---|---|---|

| WeSync | www.wesync.com | Palm | Free |

| Beyond Contacts | www.dataviz.com | Palm | $49.95 |

| Agendus | www.iambic.com | Palm | $25.95 standard $39.95 professional |

| DateBK5 | www.pimlicosoftware.com | Palm | $24.95 |

| Agenda Fusion | www.developerone.com | Pocket PC | $29.95 |

| Pocket Informant | www.pocketinformant.com | Pocket PC | $24.95 |

| Ulti-Planner | www.uglybass.com/ultiplanner | Pocket PC | $14.95 |

If you have any questions about these products or comments about Psyber Psychiatry, click here to contact Dr. Luo or send an e-mail to [email protected] .

Disclosure

Dr. Luo reports no financial relationship with any company whose products are mentioned in this article. The opinions expressed by Dr. Luo in this column are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of Current Psychiatry.

Depressed patients won’t exercise? 7 ways to get them started

Exercise has been shown to significantly reduce depressive symptoms and decrease the chances of relapse.1

If you’re having trouble getting a depressed patient for whom exercise is not contraindicated to take that first step on the road to fitness, the following motivational tips can help:

- Explain how exercise can decrease mild to moderate depressive symptoms and improve overall health.2

- Ask patients to document the time they spend watching television, sitting in traffic, or lying on the couch, and to compare this with time spent doing physical activity. By keeping this record, patients often discover they are not exercising nearly enough.

- Emphasize that yoga, t’ai chi, aerobics, and walking are all effective types of exercise. Patients often associate “exercise” with weightlifting or long-distance running and do not consider less-strenuous options.

- Tell unmotivated patients that getting started is the hardest part. The more a patient exercises, the more motivated he or she will feel.

Keys to safe exercise

Once the patient decides to begin exercising, tell him or her to:

- Start with a light-intensity workout and gradually increase the regimen’s intensity. Encourage the patient to start with at least a once-weekly routine and advise him or her that overexertion can lead to injury.

Have a physical therapist or exercise trainer devise the program. For older or medically ill patients, clearance from an internist or family physician may be necessary.

- Exercise where the patient feels most comfortable. For example, patients who are obese or are self-conscious in public settings may prefer to work out at home.

- Keep exercising regularly and in moderation to guard against exercise addiction, “burnout,” or overtraining. Warn patients that stopping regular exercise can lead to rebound depression, anxiety, and insomnia.3 These pitfalls—which could occur as early as 2 weeks after stopping—can derail a fitness regimen and obstruct future attempts at exercise.

1. Martinsen EW, Hoffart A, Solberg O. Comparing aerobic with nonaerobic forms of exercise in the treatment of clinical depression: a randomized trial. Compr Psychiatry 1989;30:324-31.

2. Penninx BW, Rejeski WJ, Pandya J, et al. Exercise and depressive symptoms. A comparison of aerobic and resistance exercise effects on emotional and physical function in older persons with high and low depressive symptomatology. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57:124-32.

3. Morris M, Steinberg H, Sykes EA. Effects of temporary withdrawal from regular running. J Psychosom Res 1990;34:493-500.

Dr. Pillay is assistant neuroscientist at McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, and an instructor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

Exercise has been shown to significantly reduce depressive symptoms and decrease the chances of relapse.1

If you’re having trouble getting a depressed patient for whom exercise is not contraindicated to take that first step on the road to fitness, the following motivational tips can help:

- Explain how exercise can decrease mild to moderate depressive symptoms and improve overall health.2

- Ask patients to document the time they spend watching television, sitting in traffic, or lying on the couch, and to compare this with time spent doing physical activity. By keeping this record, patients often discover they are not exercising nearly enough.

- Emphasize that yoga, t’ai chi, aerobics, and walking are all effective types of exercise. Patients often associate “exercise” with weightlifting or long-distance running and do not consider less-strenuous options.

- Tell unmotivated patients that getting started is the hardest part. The more a patient exercises, the more motivated he or she will feel.

Keys to safe exercise

Once the patient decides to begin exercising, tell him or her to:

- Start with a light-intensity workout and gradually increase the regimen’s intensity. Encourage the patient to start with at least a once-weekly routine and advise him or her that overexertion can lead to injury.

Have a physical therapist or exercise trainer devise the program. For older or medically ill patients, clearance from an internist or family physician may be necessary.

- Exercise where the patient feels most comfortable. For example, patients who are obese or are self-conscious in public settings may prefer to work out at home.

- Keep exercising regularly and in moderation to guard against exercise addiction, “burnout,” or overtraining. Warn patients that stopping regular exercise can lead to rebound depression, anxiety, and insomnia.3 These pitfalls—which could occur as early as 2 weeks after stopping—can derail a fitness regimen and obstruct future attempts at exercise.

Exercise has been shown to significantly reduce depressive symptoms and decrease the chances of relapse.1

If you’re having trouble getting a depressed patient for whom exercise is not contraindicated to take that first step on the road to fitness, the following motivational tips can help:

- Explain how exercise can decrease mild to moderate depressive symptoms and improve overall health.2

- Ask patients to document the time they spend watching television, sitting in traffic, or lying on the couch, and to compare this with time spent doing physical activity. By keeping this record, patients often discover they are not exercising nearly enough.

- Emphasize that yoga, t’ai chi, aerobics, and walking are all effective types of exercise. Patients often associate “exercise” with weightlifting or long-distance running and do not consider less-strenuous options.

- Tell unmotivated patients that getting started is the hardest part. The more a patient exercises, the more motivated he or she will feel.

Keys to safe exercise

Once the patient decides to begin exercising, tell him or her to:

- Start with a light-intensity workout and gradually increase the regimen’s intensity. Encourage the patient to start with at least a once-weekly routine and advise him or her that overexertion can lead to injury.

Have a physical therapist or exercise trainer devise the program. For older or medically ill patients, clearance from an internist or family physician may be necessary.

- Exercise where the patient feels most comfortable. For example, patients who are obese or are self-conscious in public settings may prefer to work out at home.

- Keep exercising regularly and in moderation to guard against exercise addiction, “burnout,” or overtraining. Warn patients that stopping regular exercise can lead to rebound depression, anxiety, and insomnia.3 These pitfalls—which could occur as early as 2 weeks after stopping—can derail a fitness regimen and obstruct future attempts at exercise.

1. Martinsen EW, Hoffart A, Solberg O. Comparing aerobic with nonaerobic forms of exercise in the treatment of clinical depression: a randomized trial. Compr Psychiatry 1989;30:324-31.

2. Penninx BW, Rejeski WJ, Pandya J, et al. Exercise and depressive symptoms. A comparison of aerobic and resistance exercise effects on emotional and physical function in older persons with high and low depressive symptomatology. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57:124-32.

3. Morris M, Steinberg H, Sykes EA. Effects of temporary withdrawal from regular running. J Psychosom Res 1990;34:493-500.

Dr. Pillay is assistant neuroscientist at McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, and an instructor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

1. Martinsen EW, Hoffart A, Solberg O. Comparing aerobic with nonaerobic forms of exercise in the treatment of clinical depression: a randomized trial. Compr Psychiatry 1989;30:324-31.

2. Penninx BW, Rejeski WJ, Pandya J, et al. Exercise and depressive symptoms. A comparison of aerobic and resistance exercise effects on emotional and physical function in older persons with high and low depressive symptomatology. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci 2002;57:124-32.

3. Morris M, Steinberg H, Sykes EA. Effects of temporary withdrawal from regular running. J Psychosom Res 1990;34:493-500.

Dr. Pillay is assistant neuroscientist at McLean Hospital, Belmont, MA, and an instructor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School, Boston.

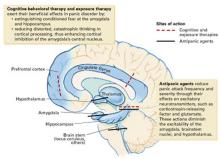

Break the ‘fear circuit’ in resistant panic disorder

When initial therapy fails to control a patient’s panic attacks, a neuroanatomic model of anxiety disorders may help. This model proposes that panic sufferers have an abnormally sensitive brain “fear circuit.”1 It suggests why both medications and cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) are effective for treating panic disorder (PD) and can be used as a guide to more successful treatment.

This article explains the fear circuit model and describes how to determine whether initial drug treatment of panic symptoms has been adequate. It offers evidence-and experience-based dosing ranges, augmentation strategies, tips for antidepressant titration, and solutions to the most common inadequate response problems.

HOW THE FEAR CIRCUIT WORKS

Panic disorder may occur with or without agoraphobia. The diagnosis requires recurrent, unexpected panic attacks (Table 1), with at least one attack followed by 1 month or more of:

- persistent concern about having additional attacks

- worry about the implications of the attack

- or significant change in behavior related to the attack.

Panic disorder is usually accompanied by phobic avoidance and anticipatory anxiety, and it often coexists with other psychiatric disorders. Anxiety disorders may share a common genetic vulnerability. Childhood experiences, gender, and life events may increase or decrease the probability that a biologically vulnerable individual will develop an anxiety disorder or depression.1

Table 1

Panic attacks: The core symptom of panic disorder

| A panic attack is a discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which four (or more) of the following symptoms develop abruptly and peak within 10 minutes: |

|

| Source: DSM-IV-TR |

Fear circuit model. PD’s pathophysiology is not completely understood, but evidence suggests that an overactive brain alarm network may increase vulnerability for PD (Box).1,2 Individual patients require different intensities of treatment to normalize their panic symptoms:

Mild to moderate PD (characterized by little or no avoidance and no comorbid disorders) often responds to either medication or CBT. A single intervention—such as using CBT to enhance the cortical inhibitory effects or using medication to reduce the amygdala’s reactivity—may suffice for symptomatic relief.

Severe or complicated PD (characterized by frequent panic attacks, significant agoraphobia, and comorbid anxiety disorders or depression) may require high medication dosages, intense CBT/exposure therapy, or both to normalize more severely disrupted communication among the fear circuit’s components.

ASSESSING TREATMENT OUTCOME