User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

Recognizing and treating ketamine abuse

The N-methyl-

Physicians need to be aware, however, that many patients use illicit ketamine, either for recreational purposes or as self-treatment to control depressive symptoms. To help clinicians identify the signs of ketamine abuse, we discuss the adverse effects of illicit use, and suggest treatment approaches.

Ad

Ketamine can be consumed in various ways; snorting it in a powder form is a preferred route for recreational use.2 The primary disadvantage of oral use is that it increases the likelihood of nausea and vomiting.2

While ketamine is generally safe in a supervised clinical setting, approximately 2.5 million individuals use various illicit forms of ketamine—which is known as Special K and by other names—in recreational settings (eg, dance clubs) where it might be used with other substances.3 Alcohol, in particular, compounds the sedative effects of ketamine and can lead to death by overdose.

At a subanesthetic dose, ketamine can induce dissociative and/or transcendental states that are particularly attractive to those intrigued by mystical experiences, pronounced changes in perception, or euphoria.4 High doses of ketamine—relative to a commonly used recreational dose—can produce a unique “K-hole” state in which a user is unable to control his/her body and could lose consciousness.5 A K-hole state may trigger a cycle of delirium that warrants immediate clinical attention.3

Researchers have postulated that NMDA antagonism may negatively impact memory consolidation.3,6 Even more troubling is the potential for systemic injuries because illicit ketamine use may contribute to ulcerative cystitis, severely disturbed kidney function (eg, hydronephrosis), or epigastric pain.3 Chronic abuse tends to result in more systemic sequelae, affecting the bladder, kidneys, and heart. Adverse effects that require emergent care include blood in urine, changes in vision (eg, nystagmus), chest discomfort, labored breathing, agitation, seizures, and/or altered consciousness.6

Treating ketamine abuse

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s symptoms. If the patient presents with “K-bladder” (ie, ketamine bladder syndrome), he/she may need surgical intervention or a cystectomy.4,7 Therapeutic management of K-bladder entails recognizing bladder symptoms that are specific to ketamine use, such as interstitial or ulcerative cystitis and lower urinary tract symptoms.7 Clinicians should monitor patients for increased voiding episodes during the day, voiding urgency, or a general sense of bladder fullness. Patients with K-bladder also may complain of suprapubic pain or blood in the urine.7

Continue to: Consider referring patients to...

Consider referring patients to an individualized, ketamine-specific rehabilitation program that is modeled after other substance-specific rehabilitation programs. It is critical to address withdrawal symptoms (eg, anorexia, fatigue, tremors, chills, tachycardia, nightmares, etc.). Patients undergoing ketamine withdrawal may develop anxiety and depression, with or without suicidal ideation, that might persist during a 4- to 5-day withdrawal period.8

‘Self-medicating’ ketamine users

Clinicians need to be particularly vigilant for situations in which a patient has used ketamine in an attempt to control his/her depressive symptoms. Some researchers have described ketamine as a revolutionary drug for TRD, and it is reasonable to suspect that some patients with depressive symptoms may have consulted Internet sources to learn how to self-medicate using ketamine. Patients who have consumed smaller doses of ketamine recreationally may have developed a tolerance in which the receptors are no longer responsive to the effects at that dose, and therefore might not respond when given ketamine in a clinical setting. Proper history taking and patient education are essential for these users, and clinicians may need to develop a personalized therapeutic plan for ketamine administration. If, on the other hand, a patient has a history of chronic ketamine use (perhaps at high doses), depression may occur secondary to this type of ketamine abuse. For such patients, clinicians should explore alternative treatment modalities, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation.

1. Kurdi MS, Theerth KA, Deva RS. Ketamine: current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8(3):283-290.

2. Davis K. What are the uses of ketamine? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/302663.php. Updated October 12, 2017. Published October 11, 2019.

3. Chaverneff F. Ketamine: mechanisms of action, uses in pain medicine, and side effects. Clinical Pain Advisor. https://www.clinicalpainadvisor.com/home/conference-highlights/painweek-2018/ketamine-mechanisms-of-action-uses-in-pain-medicine-and-side-effects/. Published 2018. Accessed October 11, 2019.

4. Gao M, Rejaei D, Liu H. Ketamine use in current clinical practice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):865-872.

5. Orhurhu VJ, Claus LE, Cohen SP. Ketamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541087. Updated April 11, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019.

6. Pai A, Heining M. Ketamine. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 20071;7(2):59-63.

7. Logan K. Addressing ketamine bladder syndrome. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/medicine-management/addressing-ketamine-bladder-syndrome-19-06-2011/. Published June 19, 2011. Accessed October 11, 2019.

8. Lin PC, Lane HY, Lin CH. Spontaneous remission of ketamine withdrawal-related depression. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39(1):51-52.

The N-methyl-

Physicians need to be aware, however, that many patients use illicit ketamine, either for recreational purposes or as self-treatment to control depressive symptoms. To help clinicians identify the signs of ketamine abuse, we discuss the adverse effects of illicit use, and suggest treatment approaches.

Ad

Ketamine can be consumed in various ways; snorting it in a powder form is a preferred route for recreational use.2 The primary disadvantage of oral use is that it increases the likelihood of nausea and vomiting.2

While ketamine is generally safe in a supervised clinical setting, approximately 2.5 million individuals use various illicit forms of ketamine—which is known as Special K and by other names—in recreational settings (eg, dance clubs) where it might be used with other substances.3 Alcohol, in particular, compounds the sedative effects of ketamine and can lead to death by overdose.

At a subanesthetic dose, ketamine can induce dissociative and/or transcendental states that are particularly attractive to those intrigued by mystical experiences, pronounced changes in perception, or euphoria.4 High doses of ketamine—relative to a commonly used recreational dose—can produce a unique “K-hole” state in which a user is unable to control his/her body and could lose consciousness.5 A K-hole state may trigger a cycle of delirium that warrants immediate clinical attention.3

Researchers have postulated that NMDA antagonism may negatively impact memory consolidation.3,6 Even more troubling is the potential for systemic injuries because illicit ketamine use may contribute to ulcerative cystitis, severely disturbed kidney function (eg, hydronephrosis), or epigastric pain.3 Chronic abuse tends to result in more systemic sequelae, affecting the bladder, kidneys, and heart. Adverse effects that require emergent care include blood in urine, changes in vision (eg, nystagmus), chest discomfort, labored breathing, agitation, seizures, and/or altered consciousness.6

Treating ketamine abuse

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s symptoms. If the patient presents with “K-bladder” (ie, ketamine bladder syndrome), he/she may need surgical intervention or a cystectomy.4,7 Therapeutic management of K-bladder entails recognizing bladder symptoms that are specific to ketamine use, such as interstitial or ulcerative cystitis and lower urinary tract symptoms.7 Clinicians should monitor patients for increased voiding episodes during the day, voiding urgency, or a general sense of bladder fullness. Patients with K-bladder also may complain of suprapubic pain or blood in the urine.7

Continue to: Consider referring patients to...

Consider referring patients to an individualized, ketamine-specific rehabilitation program that is modeled after other substance-specific rehabilitation programs. It is critical to address withdrawal symptoms (eg, anorexia, fatigue, tremors, chills, tachycardia, nightmares, etc.). Patients undergoing ketamine withdrawal may develop anxiety and depression, with or without suicidal ideation, that might persist during a 4- to 5-day withdrawal period.8

‘Self-medicating’ ketamine users

Clinicians need to be particularly vigilant for situations in which a patient has used ketamine in an attempt to control his/her depressive symptoms. Some researchers have described ketamine as a revolutionary drug for TRD, and it is reasonable to suspect that some patients with depressive symptoms may have consulted Internet sources to learn how to self-medicate using ketamine. Patients who have consumed smaller doses of ketamine recreationally may have developed a tolerance in which the receptors are no longer responsive to the effects at that dose, and therefore might not respond when given ketamine in a clinical setting. Proper history taking and patient education are essential for these users, and clinicians may need to develop a personalized therapeutic plan for ketamine administration. If, on the other hand, a patient has a history of chronic ketamine use (perhaps at high doses), depression may occur secondary to this type of ketamine abuse. For such patients, clinicians should explore alternative treatment modalities, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation.

The N-methyl-

Physicians need to be aware, however, that many patients use illicit ketamine, either for recreational purposes or as self-treatment to control depressive symptoms. To help clinicians identify the signs of ketamine abuse, we discuss the adverse effects of illicit use, and suggest treatment approaches.

Ad

Ketamine can be consumed in various ways; snorting it in a powder form is a preferred route for recreational use.2 The primary disadvantage of oral use is that it increases the likelihood of nausea and vomiting.2

While ketamine is generally safe in a supervised clinical setting, approximately 2.5 million individuals use various illicit forms of ketamine—which is known as Special K and by other names—in recreational settings (eg, dance clubs) where it might be used with other substances.3 Alcohol, in particular, compounds the sedative effects of ketamine and can lead to death by overdose.

At a subanesthetic dose, ketamine can induce dissociative and/or transcendental states that are particularly attractive to those intrigued by mystical experiences, pronounced changes in perception, or euphoria.4 High doses of ketamine—relative to a commonly used recreational dose—can produce a unique “K-hole” state in which a user is unable to control his/her body and could lose consciousness.5 A K-hole state may trigger a cycle of delirium that warrants immediate clinical attention.3

Researchers have postulated that NMDA antagonism may negatively impact memory consolidation.3,6 Even more troubling is the potential for systemic injuries because illicit ketamine use may contribute to ulcerative cystitis, severely disturbed kidney function (eg, hydronephrosis), or epigastric pain.3 Chronic abuse tends to result in more systemic sequelae, affecting the bladder, kidneys, and heart. Adverse effects that require emergent care include blood in urine, changes in vision (eg, nystagmus), chest discomfort, labored breathing, agitation, seizures, and/or altered consciousness.6

Treating ketamine abuse

Treatment should be tailored to the patient’s symptoms. If the patient presents with “K-bladder” (ie, ketamine bladder syndrome), he/she may need surgical intervention or a cystectomy.4,7 Therapeutic management of K-bladder entails recognizing bladder symptoms that are specific to ketamine use, such as interstitial or ulcerative cystitis and lower urinary tract symptoms.7 Clinicians should monitor patients for increased voiding episodes during the day, voiding urgency, or a general sense of bladder fullness. Patients with K-bladder also may complain of suprapubic pain or blood in the urine.7

Continue to: Consider referring patients to...

Consider referring patients to an individualized, ketamine-specific rehabilitation program that is modeled after other substance-specific rehabilitation programs. It is critical to address withdrawal symptoms (eg, anorexia, fatigue, tremors, chills, tachycardia, nightmares, etc.). Patients undergoing ketamine withdrawal may develop anxiety and depression, with or without suicidal ideation, that might persist during a 4- to 5-day withdrawal period.8

‘Self-medicating’ ketamine users

Clinicians need to be particularly vigilant for situations in which a patient has used ketamine in an attempt to control his/her depressive symptoms. Some researchers have described ketamine as a revolutionary drug for TRD, and it is reasonable to suspect that some patients with depressive symptoms may have consulted Internet sources to learn how to self-medicate using ketamine. Patients who have consumed smaller doses of ketamine recreationally may have developed a tolerance in which the receptors are no longer responsive to the effects at that dose, and therefore might not respond when given ketamine in a clinical setting. Proper history taking and patient education are essential for these users, and clinicians may need to develop a personalized therapeutic plan for ketamine administration. If, on the other hand, a patient has a history of chronic ketamine use (perhaps at high doses), depression may occur secondary to this type of ketamine abuse. For such patients, clinicians should explore alternative treatment modalities, such as transcranial magnetic stimulation.

1. Kurdi MS, Theerth KA, Deva RS. Ketamine: current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8(3):283-290.

2. Davis K. What are the uses of ketamine? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/302663.php. Updated October 12, 2017. Published October 11, 2019.

3. Chaverneff F. Ketamine: mechanisms of action, uses in pain medicine, and side effects. Clinical Pain Advisor. https://www.clinicalpainadvisor.com/home/conference-highlights/painweek-2018/ketamine-mechanisms-of-action-uses-in-pain-medicine-and-side-effects/. Published 2018. Accessed October 11, 2019.

4. Gao M, Rejaei D, Liu H. Ketamine use in current clinical practice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):865-872.

5. Orhurhu VJ, Claus LE, Cohen SP. Ketamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541087. Updated April 11, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019.

6. Pai A, Heining M. Ketamine. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 20071;7(2):59-63.

7. Logan K. Addressing ketamine bladder syndrome. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/medicine-management/addressing-ketamine-bladder-syndrome-19-06-2011/. Published June 19, 2011. Accessed October 11, 2019.

8. Lin PC, Lane HY, Lin CH. Spontaneous remission of ketamine withdrawal-related depression. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39(1):51-52.

1. Kurdi MS, Theerth KA, Deva RS. Ketamine: current applications in anesthesia, pain, and critical care. Anesth Essays Res. 2014;8(3):283-290.

2. Davis K. What are the uses of ketamine? Medical News Today. https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/302663.php. Updated October 12, 2017. Published October 11, 2019.

3. Chaverneff F. Ketamine: mechanisms of action, uses in pain medicine, and side effects. Clinical Pain Advisor. https://www.clinicalpainadvisor.com/home/conference-highlights/painweek-2018/ketamine-mechanisms-of-action-uses-in-pain-medicine-and-side-effects/. Published 2018. Accessed October 11, 2019.

4. Gao M, Rejaei D, Liu H. Ketamine use in current clinical practice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):865-872.

5. Orhurhu VJ, Claus LE, Cohen SP. Ketamine toxicity. StatPearls Publishing. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541087. Updated April 11, 2019. Accessed October 18, 2019.

6. Pai A, Heining M. Ketamine. Continuing Education in Anaesthesia Critical Care & Pain. 20071;7(2):59-63.

7. Logan K. Addressing ketamine bladder syndrome. Nursing Times. https://www.nursingtimes.net/clinical-archive/medicine-management/addressing-ketamine-bladder-syndrome-19-06-2011/. Published June 19, 2011. Accessed October 11, 2019.

8. Lin PC, Lane HY, Lin CH. Spontaneous remission of ketamine withdrawal-related depression. Clin Neuropharmacol. 2016;39(1):51-52.

Neuropsychological testing: A useful but underutilized resource

We have all treated a patient for whom you know you had the diagnosis correct, the medication regimen was working, and the patient adhered to treatment, but something was still “off.” There was something cognitively that wasn’t right, and you had identified subtle (and some overt) errors in the standard psychiatric cognitive assessment that didn’t seem amenable to psychotropic medications. Perhaps what was needed was neuropsychological testing, one of the most useful but underutilized resources available to help fine-tune diagnosis and treatment. Finding a neuropsychologist who is sensitive to the unique needs of patients with psychiatric disorders, and knowing what and how to communicate the clinical picture and need for the referral, can be challenging due to the limited availability, time, and cost of a full battery of standardized tests.

This article describes the purpose of neuropsychological testing, why it is an important part of psychiatry, and how to make the best use of it.

What is neuropsychological testing?

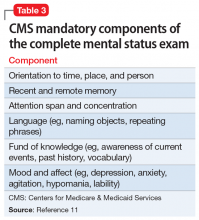

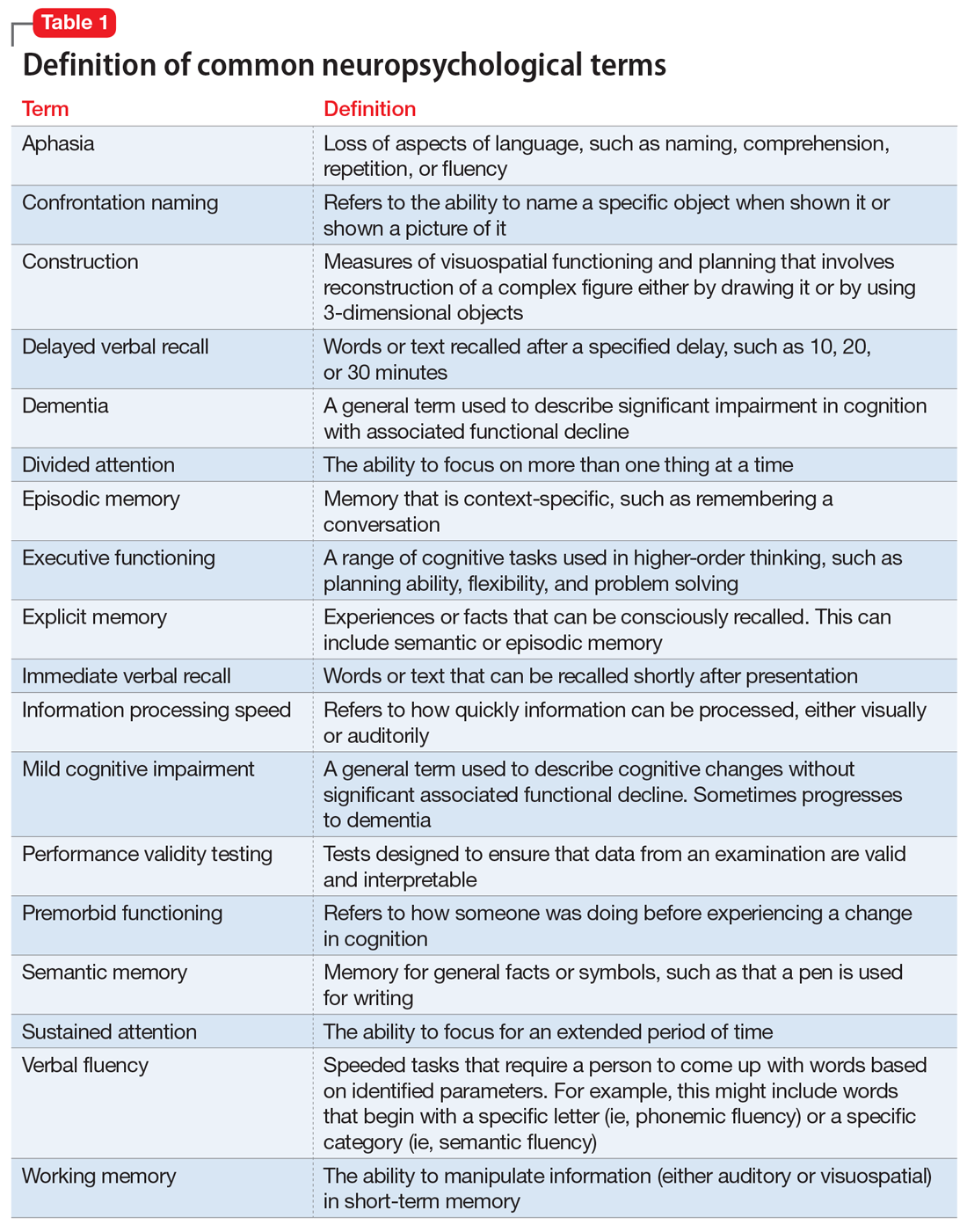

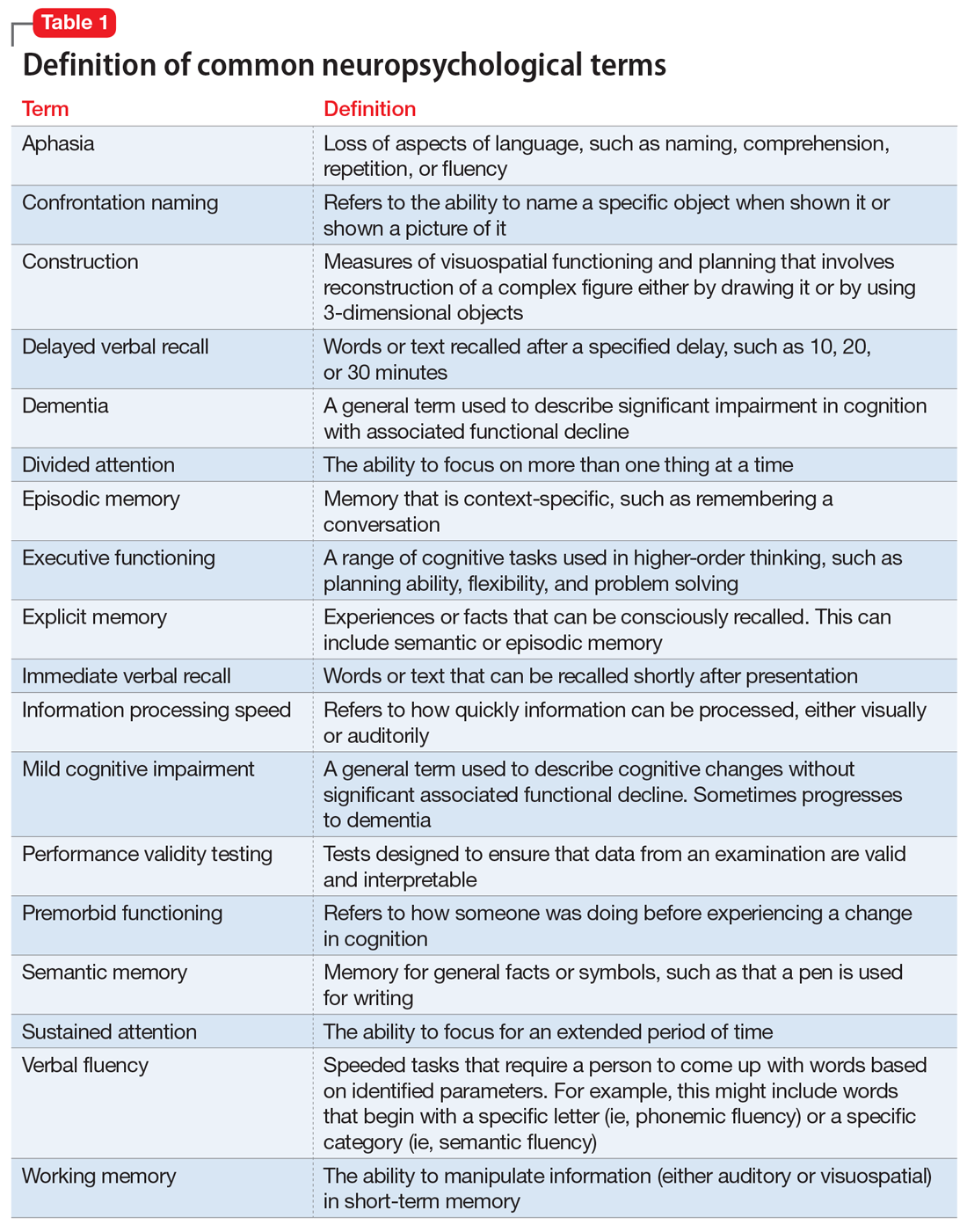

Neuropsychological testing is a comprehensive evaluation designed to assess cognitive functioning, such as attention, language, learning, memory, and visuospatial and executive functioning. Neuropsychology has its own vocabulary and lexicon that are important for psychiatric clinicians to understand. Some terms, such as aphasia, working memory, and dementia, are familiar to many clinicians. However, others, such as information processing speed, performance validity testing, and semantic memory, might not be. Common neuropsychological terms are defined in Table 1.

The neuropsychologist’s role

A neuropsychologist is a psychologist with advanced training in brain-behavior relationships who can help determine if cognitive problems are related to neurologic, medical, or psychiatric factors. A neuropsychological evaluation can identify the etiology of a patient’s cognitive difficulties, such as stroke, poorly controlled diabetes, or mental health symptoms, to help guide treatment. It can be difficult to determine if a patient who is experiencing significant cognitive, functional, or behavioral changes has an underlying cognitive disorder (eg, dementia or major neurocognitive disorder) or something else, such as a psychiatric condition. Indeed, many psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and major depressive disorder (MDD), can present with significant cognitive difficulties. Thus, when patients report an increase in forgetfulness or changes in their ability to care for themselves, neuropsychological testing can help determine the cause.

How to refer to a neuropsychologist

Developing a referral network with a neuropsychologist should be a component of establishing a psychiatric practice. A neuropsychologist can help identify deficits that may interfere with the patient’s ability to adhere to a treatment plan, monitor medications, or actively participate in treatment and therapy. When making a referral for neuropsychological testing, it is important to be clear about the specific concerns so the neuropsychologist knows how to best evaluate the patient. A psychiatric clinician does not order specific neuropsychological tests, but thoroughly describes the problem so the neuropsychologist can determine the appropriate tests after interviewing the patient. For example, if a patient reports memory problems, it is essential to give the neuropsychologist specific clinical data so he/she can determine if the symptoms are due to a neurodegenerative or psychiatric condition. Then, after interviewing the patient (and, possibly, a family member), the neuropsychologist can construct a battery of tests to best answer the question.

Which neuropsychological tests are available?

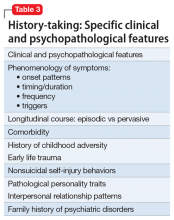

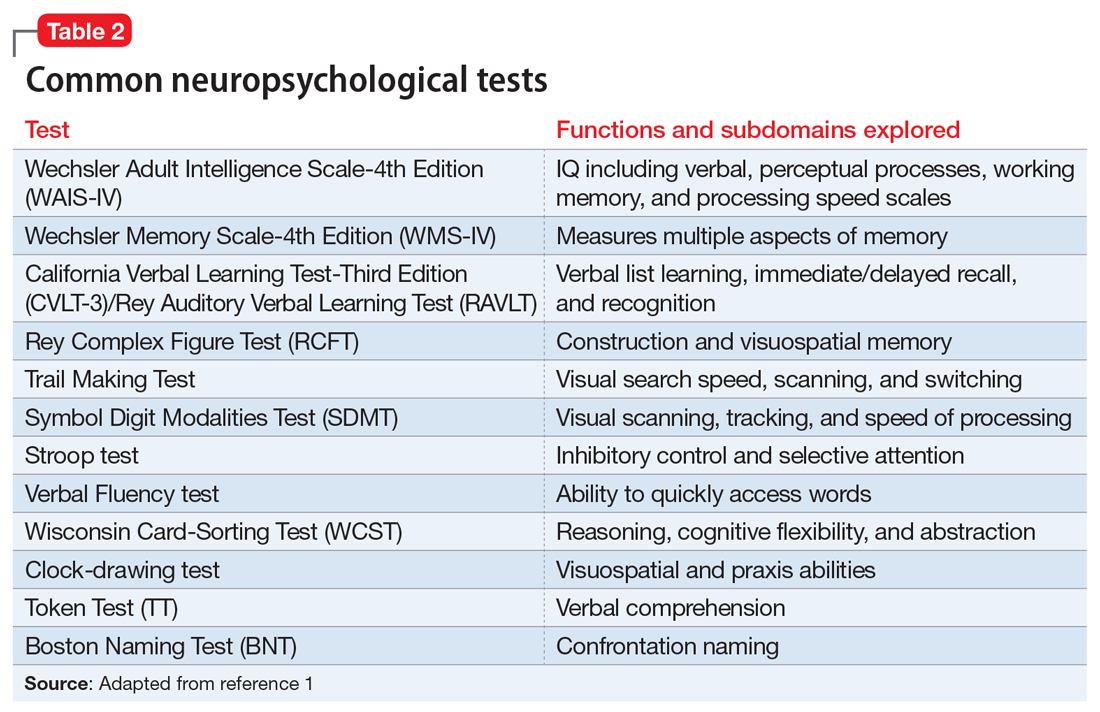

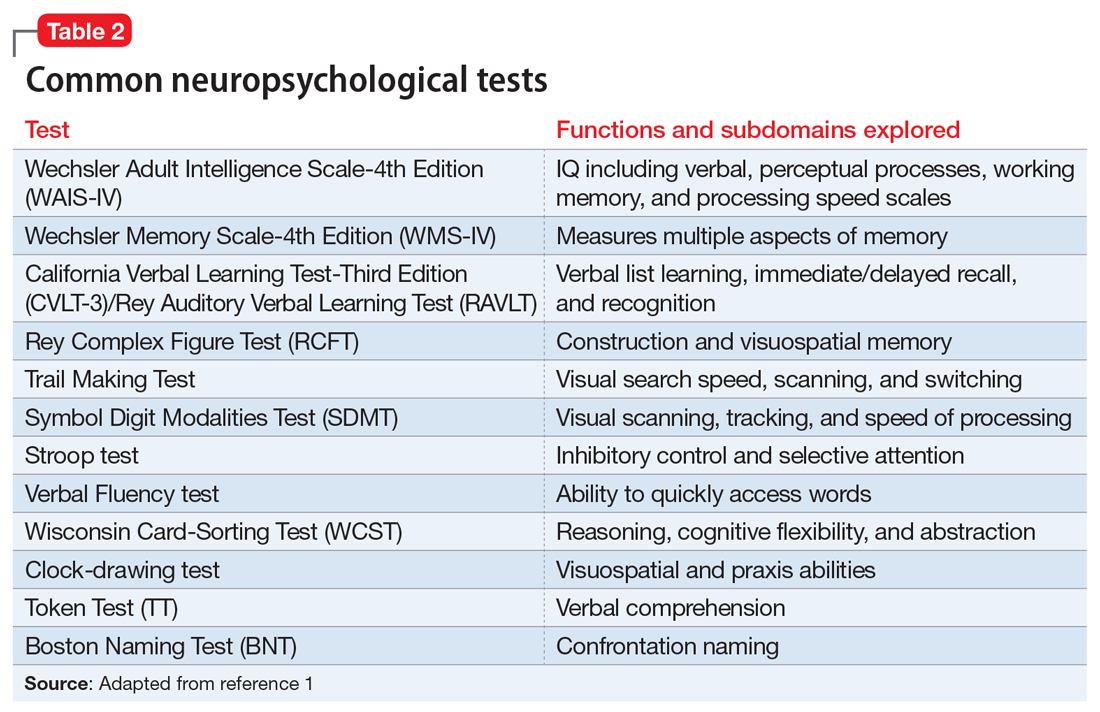

There is a large battery of neuropsychological tests that require a licensed psychologist to administer and interpret.1 Those commonly used in research and practice to differentiate neurologically-based cognitive deficits associated with psychiatric disorders include the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-4th edition (WAIS-IV) for assessing intelligence, the California Verbal Learning Test-Third Edition (CVLT-3) for verbal memory and learning, the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised for visual memory, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) for executive functions, and the Ruff 2&7 Selective Attention Test for sustained attention.2 These and other commonly used tests are described in Table 2.1

Neuropsychological testing vs psychological testing

The neuropsychologist will use psychometric properties (such as the validity and reliability of the test) and available normative data to pick the most appropriate tests. To date, there are no specific tests that clearly delineate psychiatric from nonpsychiatric etiologies, although the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP)3 was developed in 2013 to explore cognitive abilities in the functional psychoses; it is beginning to be used in other studies.4,5 The neuropsychologist will consider the patient’s current concerns, the onset and progression of these concerns, and the pattern in testing behavior to help determine if psychiatric conditions are the most likely etiology.

Continue to: In addition to cognitive tests...

In addition to cognitive tests, the neuropsychologist might also administer psychological tests. These might include commonly used screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)6 or Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),7 or more comprehensive objective personality measures, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Format (MMPI-2-RF)8 or Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI).9 These tests, along with a thorough clinical history, can help identify if a psychiatric condition is present. In addition, for the more extensive tests such as the MMPI-2-RF or PAI, there are certain neuropsychological profiles that are consistent with a psychiatric etiology for cognitive difficulties. These profiles are formulated based on specific test scores in combination with complex patient variables.

Understanding the report

While there will be stylistic differences in reports depending on the neuropsychologist’s setting, referral source, and personal preferences, most will include discussion of why the patient was referred for evaluation and a description of the onset and progression of the problem.10 Reports often also include pertinent medical and psychiatric history, substance use history, and family medical history. A section on social history is important to help establish premorbid functioning, and might include information about prenatal/birth complications, developmental milestones, educational history, and occupational history. Information about current psychosocial support or stressors, including marital status or current/past legal issues, can be helpful. In addition to this history, there is often a section on behavioral observations, especially if anything stood out or might have affected the validity of the data.

There are also objective measures of validity that the neuropsychologist might administer to evaluate whether the results are valid. Issues of validity are monitored through the evaluation, and are used to determine if the results are consistent with known neurologic patterns. If the results are deemed not valid, then low scores cannot be reliably interpreted as evidence of impairment. This is akin to an arm moving during an X-ray, thereby blurring the results. If valid, the results of objective testing are include in the neuropsychologist’s report; this can range from providing raw scores, standard scores, and/or percentiles to a general description of how the patient did on testing.

The section that is usually of most interest to psychiatric clinicians is the summary, which explains the results, might offer a diagnosis, and discusses possible etiologies. This might be where the neuropsychologist discusses if the findings are due to a neurologic or psychiatric condition. From this comes the neuropsychologist’s recommendations. When a psychiatric condition is determined to be the underlying etiology, the neuropsychologist might recommend psychotherapy or some other psychiatric treatment.

Why is neuropsychological testing important?

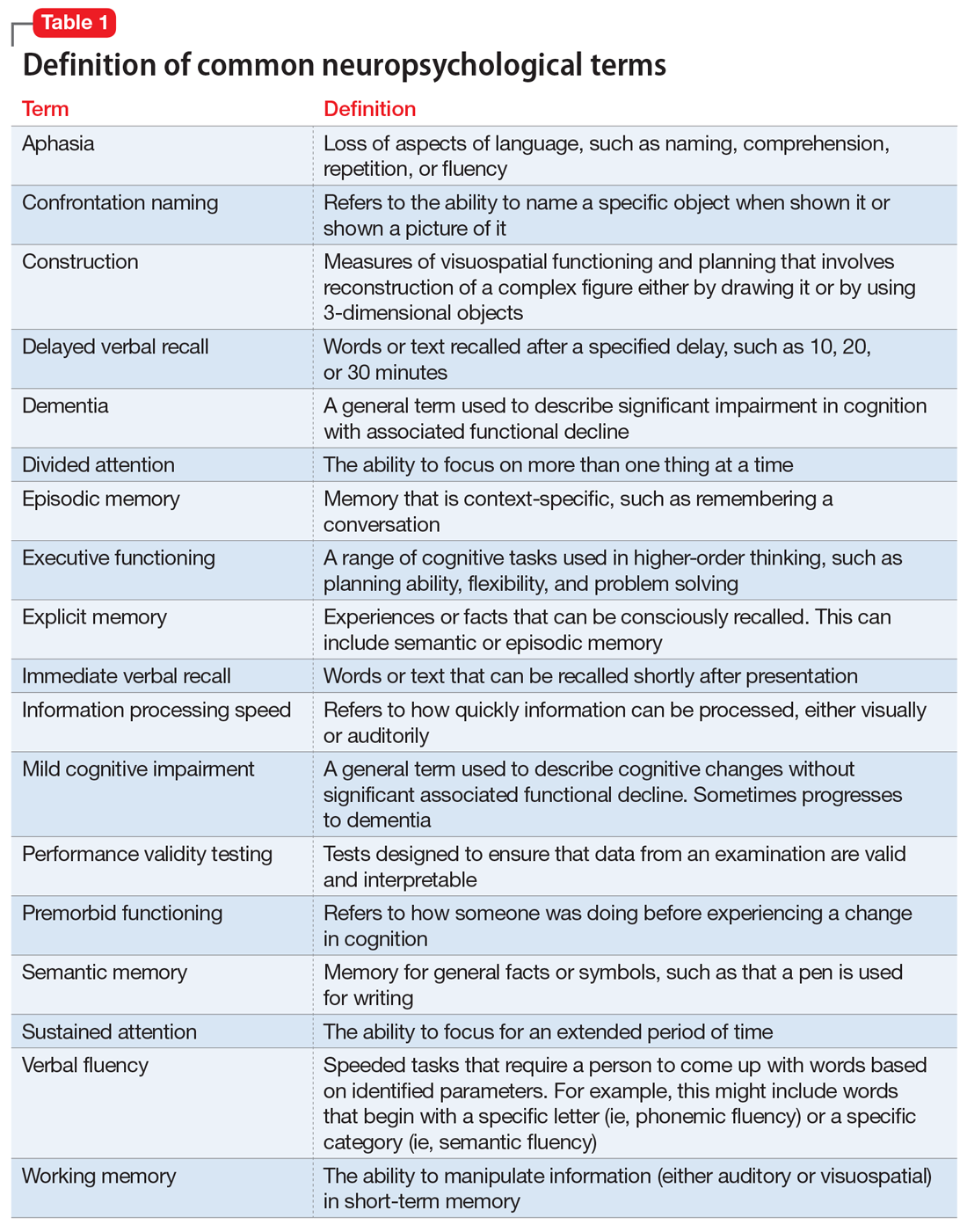

Schizophrenia, MDD, bipolar disorder, and PTSD produce significant neurobiologic changes that often result in deterioration of a patient’s global cognitive function. Increased emphasis and attention in psychiatric research have yielded more clues to the neurobiology of cognition. However, even though many psychiatric clinicians are trained in cognitive assessments, such as the “clock test,” “serial sevens,” “numbers forward and backward,” “proverb,” and “word recall,” and common scenarios to evaluate judgment and insight, such as “mailing a letter” and “smoke in a movie theatre,” most of these components are not completed during a standard psychiatric evaluation. Because the time allotted to completing a psychiatric evaluation continues to be shortened, it is sometimes difficult to complete the “6 bullets” required by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as part of the mental status exam (Table 311).

Continue to: To date, the best evidence...

To date, the best evidence for neuropsychological deficits exists for patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and PTSD.12,13 The Box2,14-24 describes the findings of studies of neuropsychological deficits in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Box

Patients with schizophrenia have been the subjects of neuropsychological testing for decades. The results have shown deficits on many standardized tests, including those of attention, memory, and executive functioning, although some patients might perform within normal limits.15

A federal initiative through the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) known as MATRICS (Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia) was developed in the late 1990s to develop consensus on the underlying cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. MATRICS was created with the hopes that it would allow the FDA to approve treatments for those cognitive deficits independent of psychosis because current psychotropic medications have minimal efficacy on cognition.16,17 The MATRICS group identified working memory, attention/vigilance, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, speed of processing, reasoning and problem solving, and social cognition as the key cognitive domains most affected in schizophrenia.14 The initial program has since evolved into 3 distinct NIMH programs: CNTRICS18 (Cognitive Neuroscience Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia), TURNS19 (Treatment Units for Research on Neurocognition in Schizophrenia), and TENETS20 (Treatment and Evaluation Network for Trials in Schizophrenia). The combination of neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging has led to the conceptualization of schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Individuals at risk for psychosis

As clinicians, we have long heard from parents of children with schizophrenia a standard trajectory of functional decline: early premorbid changes, a fairly measurable prodromal period marked by subtle deterioration in cognitive functioning, followed by the actual illness trajectory. In a recent meta-analysis, researchers compared the results of 60 neuropsychological tests comprising 9 domains in people who were at clinical high risk for psychosis who eventually converted to a psychotic disorder (CHR-P), those at clinical high risk who did not convert to psychosis (CHR-NP), and healthy controls.21 They found that neuropsychological performance deficits were greater in CHR-P individuals than in those in the CHR-NP group, and both had greater deficits than healthy controls.

For many patients with schizophrenia, full cognitive maturation is never reached.22 In general, decreased motivation in schizophrenia has been correlated with neurocognitive deficits.23

Schizophrenia vs bipolar disorder

In a study comparing neuropsychological functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychotic features (BP-P), researchers found greater deficits in schizophrenia, including immediate verbal recall, working memory, processing speed, and verbal fluency.22 Patients with BP-P demonstrated impairment consistent with generalized impairment in verbal learning and memory, working memory, and processing speed.22

Children/adolescents

In a recent study comparing child and adolescent offspring of patients with schizophrenia (n = 41) and bipolar disorder (n = 90), researchers identified neuropsychological deficits in visual memory for both groups, suggesting common genetic linkages. The schizophrenia offspring scored lower in verbal memory and word memory, while bipolar offspring scored lower on the processing speed index and visual memory.2

Information processing

Another study compared the results of neuropsychological testing and the P300 component of auditory event-related potential (an electrophysiological measure) in 30 patients with schizophrenia, siblings without illness, and normal controls.24 The battery of neuropsychological tests included the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Digit Vigilance Test, Trail Making Test-B, and Stroop test. The P300 is well correlated with information processing. Researchers found decreased P300 amplitude and latency in the patients and normal levels in the controls; siblings scored somewhere in between.24 Scores on the neuropsychological tests were consistently below normal in both patients and their siblings, with patients scoring the lowest.24

Continue to: Neuropsychological testing

Neuropsychological testing: 2 Case studies

The following 2 cases illustrate the pivotal role of neuropsychological testing in formulating an accurate differential diagnosis, and facilitating improved outcomes.

Case 1

A veteran with PTSD and memory complaints

Mr. J, age 70, is a married man who spent his career in the military, including combat service in the Vietnam War. His service in Vietnam included an event in which he couldn’t save platoon members from an ambush and death in a firefight, after which he developed PTSD. He retired after 25 years of service.

Mr. J’s psychiatrist refers him to a neuropsychologist for complaints of memory difficulties, including a fear that he’s developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Because of the concern for AD, he undergoes tests of learning and memory, such as the CVLT-3, the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised, and the Logical Memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale–4th Edition. Other tests include a measure of confrontation naming, verbal fluency (phonemic and semantic fluency), construction, attention, processing speed, and problem solving. In addition, a measure of psychiatric and emotional functioning is also administered (the MMPI-2-RF).

The results determined that Mr. J’s subjective experience of recall deficits is better explained by anxiety resulting from the cumulative impact of day-to-day emotional stress in the setting of chronic PTSD.25 Mr. J was experiencing cognitive sequelae from a complicated emotional dynamic, comprised of situational stress, amplified by coping difficulties that were rooted in older posttraumatic symptoms. These emotions, and the cognitive load they generated, interfered with the normal processes of attention and organization necessary for the encoding of information to be remembered.26 He described being visibly angered by the clutter in his home (the result of multiple people living there, including a young grandchild), having his efforts to get things done interrupted by the needs of others, and a perceived loss of control gradually generalized to even mundane circumstances, as often occurs with traumatic responses. In short, he was chronically overwhelmed and not experiencing the beginnings of dementia.

For Mr. J, neuropsychological testing helped define the focus and course of therapy. If he had been diagnosed with a major neurocognitive disorder, therapy might have taken a more acceptance and grief-based approach, to help him adjust to a chronic, potentially life-limiting condition. Because this diagnosis was ruled out, and his cognitive complaints were determined to be secondary to a core diagnosis of PTSD, therapy instead focused on treating PTSD.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2

A 55-year-old with bipolar I disorder

Mr. S, age 55, is taken to the emergency department (ED) because of his complaints of a severe headache. While undergoing brain MRI, Mr. S becomes highly agitated and aggressive to the radiology staff and is transferred to the psychiatric inpatient unit. He has a history of bipolar disorder that was treated with lithium approximately 20 years ago. Due to continued agitation, he is transferred to the state hospital and prescribed multiple medications, including an unspecified first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) that results in drooling and causes him to stoop and shuffle.

Mr. S’s wife contacts a community psychiatrist after becoming frustrated by her inability to communicate with the staff at the state hospital. During a 1-hour consult, she reveals that Mr. S was a competitive speedboat racer and had suffered numerous concussions due to accidents; at least 3 of these concussions that occurred when he was in his 20s and 30s had included a loss of consciousness. Mr. S had always been treated in the ED, and never required hospitalization. He had a previous marriage, was estranged from his ex-wife and 3 children, and has a history of alcohol abuse.

The MRI taken in the ED reveals numerous patches of scar tissue throughout the cortex, most notably in the striatum areas. The psychiatrist suspects that Mr. S’s agitation and irritation were related to focal seizure activity. He encourages Mr. S’s wife to speak with the attending psychiatrist at the state hospital and ask for him to be discharged home under her care.

Eventually, Mr. S is referred for a neurologic consult and neuropsychological testing. The testing included measures of attention and working, learning and memory, and executive functioning. The results reveal numerous deficits that Mr. S had been able to compensate for when he was younger, including problems with recall of newly learned information and difficulty modifying his behavior according to feedback. Mr. S is weaned from high doses of the FGA and is stabilized on 2 antiepileptic agents, sertraline, and low-dose olanzapine. A rehabilitation plan is developed, and Mr. S remains out of the hospital.

A team-based approach

Psychiatric clinicians need to recognize the subtle as well as overt cognitive deficits present in patients with many of the illnesses that we treat on a daily basis. In this era of performance- and value-based care, it is important to understand the common neuropsychological tests available to assist in providing patient-centered care tailored to specific cognitive deficits. Including a neuropsychologist is essential to implementing a team-based approach.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Neuropsychological testing can help pinpoint key cognitive deficits that interfere with the potential for optimal patient outcomes. Psychiatric clinicians need to be knowledgeable about the common tests used and how to incorporate the results into their diagnosis and treatment plans.

Related Resources

- The American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology. www.theaacn.org.

- Schwarz L. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Zucchella C, Federico A, Martini A, et al. Neuropsychological testing: how to understand it. Practical Neurology. 2018;18(3):227-237.

2. de la Serna E, Sugranyes G, Sanchez-Gistau V, et al. Neuropsychological characteristics of child and adolescent offspring of patients with schizophrenia or bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2017;183:110-115.

3. Gómez-Benito J, Guilera G, Pino Ó, et al. The screen for cognitive impairment in psychiatry: diagnostic-specific standardization in psychiatric ill patients. BMC Psychiatry. 2013;13:127.

4. Fuente-Tomas L, Arranz B, Safont G, et al. Classification of patients with bipolar disorder using k-means clustering. PLoS One. 2019;14(1):e0210314.

5. Kronbichler L, Stelzig-Schöler R, Pearce BG, et al. Schizophrenia and category-selectivity in the brain: Normal for faces but abnormal for houses. Front Psychiatry. 2018;9:47.

6. Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(9):606-613.

7. Yesavage A, Brink TL, Rose TL, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale: a preliminary report. J Psychiatr Res. 1983;17(1):37-49.

8. Ben-Porath YS, Tellegen A. Minnesota multi-phasic personality inventory-2 restructured form: MMPI-2-RF. San Antonio, TX: NCS Pearson; 2008.

9. Morey LC. Personality assessment inventory. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources; 1991.

10. Donder J, ed. Neuropsychological report writing. New York, NY: The Guilford Press; 2016.

11. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Evaluation and management services. https://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/Downloads/eval-mgmt-serv-guide-ICN006764.pdf. Published August 2017. Accessed October 10, 2019.

12. Hunt S, Root JC, Bascetta BL. Effort testing in schizophrenia and schizoaffective disorder: validity indicator profile and test of memory malingering performance characteristics. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2014;29(2):164-172.

13. Gorlyn M, Keilp J, Burke A, et al. Treatment-related improvement in neuropsychological functioning in suicidal depressed patients: paroxetine vs. bupropion. Psychiatry Res. 2015;225(3):407-412.

14. Pettersson R, Söderström S, Nilsson KW. Diagnosing ADHD in adults: an examination of the discriminative validity of neuropsychological tests and diagnostic assessment instruments. J Atten Disord. 2018;22(11):1019-1031.

15. Urfer-Parnas, A, Mortensen EL, Parnas J. Core of schizophrenia: estrangement, dementia or neurocognitive disorder? Psychopathology. 2010;43(5):300-311.

16. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, Gold JM, et al. Approaching a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials in schizophrenia: the NIMH-MATRICS conference to select cognitive domains and test criteria. Biolog Psych. 2004;56(5):301-307.

17. Green MF, Nuechterlein KH. The MATRICS initiative: developing a consensus cognitive battery for clinical trials. Schizophr Res. 2004;72(1):1-3.

18. Kern RS, Green MF, Nuechterlein KH, et al. NIMH-MATRICS survey on assessment of neurocognition in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2004;72(1):11-19.

19. Carter CS, Barch DM. Cognitive neuroscience-based approaches to measuring and improving treatment effects on cognition in schizophrenia: the CNTRICS initiative. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(5):1131-1137.

20. Geyer M. New opportunities in the treatment of cognitive impairments associated with schizophrenia. Curr Dir Psych Sci. 2010;19(4):264-269.

21. Hauser M, Zhang JP, Sheridan EM, et al. Neuropsychological test performance to enhance identification of subjects at clinical high risk for psychosis and to be most promising for predictive algorithms for conversion to psychosis: a meta-analysis. J Clin Psych. 2017;78(1):e28-e40. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15r10197.

22. Menkes MW, Armstrong K, Blackford JU, et al. Neuropsychological functioning in early and chronic stages of schizophrenia and psychotic bipolar disorder. Schizophr Res. 2019;206:413-419.

23. Najas-Garcia A, Gomez-Benito J, Hueda-Medina T. The relationship of motivation and neurocognition with functionality in schizophrenia: a meta-analytic review. Community Ment Health J. 2018;54(7):1019-1049.

24. Raghavan DV, Shanmugiah A, Bharathi P, et al. P300 and neuropsychological measurements in patients with schizophrenia and their healthy biological siblings. Indian J Psychiatry. 2016;58(4):454-458.

25. Mozzambani A, Fuso S, Malta S, et al. Long-term follow-up of attentional and executive functions of PTSD patients. Psychol Neurosci. 2017;10(2):215-224.

26. Woon F, Farrer T, Braman C, et al A meta-analysis of the relationship between symptom severity of posttraumatic stress disorder and executive function. Cogn Neuropsychiatry. 2017;22(1):1-16.

We have all treated a patient for whom you know you had the diagnosis correct, the medication regimen was working, and the patient adhered to treatment, but something was still “off.” There was something cognitively that wasn’t right, and you had identified subtle (and some overt) errors in the standard psychiatric cognitive assessment that didn’t seem amenable to psychotropic medications. Perhaps what was needed was neuropsychological testing, one of the most useful but underutilized resources available to help fine-tune diagnosis and treatment. Finding a neuropsychologist who is sensitive to the unique needs of patients with psychiatric disorders, and knowing what and how to communicate the clinical picture and need for the referral, can be challenging due to the limited availability, time, and cost of a full battery of standardized tests.

This article describes the purpose of neuropsychological testing, why it is an important part of psychiatry, and how to make the best use of it.

What is neuropsychological testing?

Neuropsychological testing is a comprehensive evaluation designed to assess cognitive functioning, such as attention, language, learning, memory, and visuospatial and executive functioning. Neuropsychology has its own vocabulary and lexicon that are important for psychiatric clinicians to understand. Some terms, such as aphasia, working memory, and dementia, are familiar to many clinicians. However, others, such as information processing speed, performance validity testing, and semantic memory, might not be. Common neuropsychological terms are defined in Table 1.

The neuropsychologist’s role

A neuropsychologist is a psychologist with advanced training in brain-behavior relationships who can help determine if cognitive problems are related to neurologic, medical, or psychiatric factors. A neuropsychological evaluation can identify the etiology of a patient’s cognitive difficulties, such as stroke, poorly controlled diabetes, or mental health symptoms, to help guide treatment. It can be difficult to determine if a patient who is experiencing significant cognitive, functional, or behavioral changes has an underlying cognitive disorder (eg, dementia or major neurocognitive disorder) or something else, such as a psychiatric condition. Indeed, many psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and major depressive disorder (MDD), can present with significant cognitive difficulties. Thus, when patients report an increase in forgetfulness or changes in their ability to care for themselves, neuropsychological testing can help determine the cause.

How to refer to a neuropsychologist

Developing a referral network with a neuropsychologist should be a component of establishing a psychiatric practice. A neuropsychologist can help identify deficits that may interfere with the patient’s ability to adhere to a treatment plan, monitor medications, or actively participate in treatment and therapy. When making a referral for neuropsychological testing, it is important to be clear about the specific concerns so the neuropsychologist knows how to best evaluate the patient. A psychiatric clinician does not order specific neuropsychological tests, but thoroughly describes the problem so the neuropsychologist can determine the appropriate tests after interviewing the patient. For example, if a patient reports memory problems, it is essential to give the neuropsychologist specific clinical data so he/she can determine if the symptoms are due to a neurodegenerative or psychiatric condition. Then, after interviewing the patient (and, possibly, a family member), the neuropsychologist can construct a battery of tests to best answer the question.

Which neuropsychological tests are available?

There is a large battery of neuropsychological tests that require a licensed psychologist to administer and interpret.1 Those commonly used in research and practice to differentiate neurologically-based cognitive deficits associated with psychiatric disorders include the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-4th edition (WAIS-IV) for assessing intelligence, the California Verbal Learning Test-Third Edition (CVLT-3) for verbal memory and learning, the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised for visual memory, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) for executive functions, and the Ruff 2&7 Selective Attention Test for sustained attention.2 These and other commonly used tests are described in Table 2.1

Neuropsychological testing vs psychological testing

The neuropsychologist will use psychometric properties (such as the validity and reliability of the test) and available normative data to pick the most appropriate tests. To date, there are no specific tests that clearly delineate psychiatric from nonpsychiatric etiologies, although the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP)3 was developed in 2013 to explore cognitive abilities in the functional psychoses; it is beginning to be used in other studies.4,5 The neuropsychologist will consider the patient’s current concerns, the onset and progression of these concerns, and the pattern in testing behavior to help determine if psychiatric conditions are the most likely etiology.

Continue to: In addition to cognitive tests...

In addition to cognitive tests, the neuropsychologist might also administer psychological tests. These might include commonly used screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)6 or Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),7 or more comprehensive objective personality measures, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Format (MMPI-2-RF)8 or Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI).9 These tests, along with a thorough clinical history, can help identify if a psychiatric condition is present. In addition, for the more extensive tests such as the MMPI-2-RF or PAI, there are certain neuropsychological profiles that are consistent with a psychiatric etiology for cognitive difficulties. These profiles are formulated based on specific test scores in combination with complex patient variables.

Understanding the report

While there will be stylistic differences in reports depending on the neuropsychologist’s setting, referral source, and personal preferences, most will include discussion of why the patient was referred for evaluation and a description of the onset and progression of the problem.10 Reports often also include pertinent medical and psychiatric history, substance use history, and family medical history. A section on social history is important to help establish premorbid functioning, and might include information about prenatal/birth complications, developmental milestones, educational history, and occupational history. Information about current psychosocial support or stressors, including marital status or current/past legal issues, can be helpful. In addition to this history, there is often a section on behavioral observations, especially if anything stood out or might have affected the validity of the data.

There are also objective measures of validity that the neuropsychologist might administer to evaluate whether the results are valid. Issues of validity are monitored through the evaluation, and are used to determine if the results are consistent with known neurologic patterns. If the results are deemed not valid, then low scores cannot be reliably interpreted as evidence of impairment. This is akin to an arm moving during an X-ray, thereby blurring the results. If valid, the results of objective testing are include in the neuropsychologist’s report; this can range from providing raw scores, standard scores, and/or percentiles to a general description of how the patient did on testing.

The section that is usually of most interest to psychiatric clinicians is the summary, which explains the results, might offer a diagnosis, and discusses possible etiologies. This might be where the neuropsychologist discusses if the findings are due to a neurologic or psychiatric condition. From this comes the neuropsychologist’s recommendations. When a psychiatric condition is determined to be the underlying etiology, the neuropsychologist might recommend psychotherapy or some other psychiatric treatment.

Why is neuropsychological testing important?

Schizophrenia, MDD, bipolar disorder, and PTSD produce significant neurobiologic changes that often result in deterioration of a patient’s global cognitive function. Increased emphasis and attention in psychiatric research have yielded more clues to the neurobiology of cognition. However, even though many psychiatric clinicians are trained in cognitive assessments, such as the “clock test,” “serial sevens,” “numbers forward and backward,” “proverb,” and “word recall,” and common scenarios to evaluate judgment and insight, such as “mailing a letter” and “smoke in a movie theatre,” most of these components are not completed during a standard psychiatric evaluation. Because the time allotted to completing a psychiatric evaluation continues to be shortened, it is sometimes difficult to complete the “6 bullets” required by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as part of the mental status exam (Table 311).

Continue to: To date, the best evidence...

To date, the best evidence for neuropsychological deficits exists for patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and PTSD.12,13 The Box2,14-24 describes the findings of studies of neuropsychological deficits in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Box

Patients with schizophrenia have been the subjects of neuropsychological testing for decades. The results have shown deficits on many standardized tests, including those of attention, memory, and executive functioning, although some patients might perform within normal limits.15

A federal initiative through the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) known as MATRICS (Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia) was developed in the late 1990s to develop consensus on the underlying cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. MATRICS was created with the hopes that it would allow the FDA to approve treatments for those cognitive deficits independent of psychosis because current psychotropic medications have minimal efficacy on cognition.16,17 The MATRICS group identified working memory, attention/vigilance, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, speed of processing, reasoning and problem solving, and social cognition as the key cognitive domains most affected in schizophrenia.14 The initial program has since evolved into 3 distinct NIMH programs: CNTRICS18 (Cognitive Neuroscience Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia), TURNS19 (Treatment Units for Research on Neurocognition in Schizophrenia), and TENETS20 (Treatment and Evaluation Network for Trials in Schizophrenia). The combination of neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging has led to the conceptualization of schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Individuals at risk for psychosis

As clinicians, we have long heard from parents of children with schizophrenia a standard trajectory of functional decline: early premorbid changes, a fairly measurable prodromal period marked by subtle deterioration in cognitive functioning, followed by the actual illness trajectory. In a recent meta-analysis, researchers compared the results of 60 neuropsychological tests comprising 9 domains in people who were at clinical high risk for psychosis who eventually converted to a psychotic disorder (CHR-P), those at clinical high risk who did not convert to psychosis (CHR-NP), and healthy controls.21 They found that neuropsychological performance deficits were greater in CHR-P individuals than in those in the CHR-NP group, and both had greater deficits than healthy controls.

For many patients with schizophrenia, full cognitive maturation is never reached.22 In general, decreased motivation in schizophrenia has been correlated with neurocognitive deficits.23

Schizophrenia vs bipolar disorder

In a study comparing neuropsychological functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychotic features (BP-P), researchers found greater deficits in schizophrenia, including immediate verbal recall, working memory, processing speed, and verbal fluency.22 Patients with BP-P demonstrated impairment consistent with generalized impairment in verbal learning and memory, working memory, and processing speed.22

Children/adolescents

In a recent study comparing child and adolescent offspring of patients with schizophrenia (n = 41) and bipolar disorder (n = 90), researchers identified neuropsychological deficits in visual memory for both groups, suggesting common genetic linkages. The schizophrenia offspring scored lower in verbal memory and word memory, while bipolar offspring scored lower on the processing speed index and visual memory.2

Information processing

Another study compared the results of neuropsychological testing and the P300 component of auditory event-related potential (an electrophysiological measure) in 30 patients with schizophrenia, siblings without illness, and normal controls.24 The battery of neuropsychological tests included the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Digit Vigilance Test, Trail Making Test-B, and Stroop test. The P300 is well correlated with information processing. Researchers found decreased P300 amplitude and latency in the patients and normal levels in the controls; siblings scored somewhere in between.24 Scores on the neuropsychological tests were consistently below normal in both patients and their siblings, with patients scoring the lowest.24

Continue to: Neuropsychological testing

Neuropsychological testing: 2 Case studies

The following 2 cases illustrate the pivotal role of neuropsychological testing in formulating an accurate differential diagnosis, and facilitating improved outcomes.

Case 1

A veteran with PTSD and memory complaints

Mr. J, age 70, is a married man who spent his career in the military, including combat service in the Vietnam War. His service in Vietnam included an event in which he couldn’t save platoon members from an ambush and death in a firefight, after which he developed PTSD. He retired after 25 years of service.

Mr. J’s psychiatrist refers him to a neuropsychologist for complaints of memory difficulties, including a fear that he’s developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Because of the concern for AD, he undergoes tests of learning and memory, such as the CVLT-3, the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised, and the Logical Memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale–4th Edition. Other tests include a measure of confrontation naming, verbal fluency (phonemic and semantic fluency), construction, attention, processing speed, and problem solving. In addition, a measure of psychiatric and emotional functioning is also administered (the MMPI-2-RF).

The results determined that Mr. J’s subjective experience of recall deficits is better explained by anxiety resulting from the cumulative impact of day-to-day emotional stress in the setting of chronic PTSD.25 Mr. J was experiencing cognitive sequelae from a complicated emotional dynamic, comprised of situational stress, amplified by coping difficulties that were rooted in older posttraumatic symptoms. These emotions, and the cognitive load they generated, interfered with the normal processes of attention and organization necessary for the encoding of information to be remembered.26 He described being visibly angered by the clutter in his home (the result of multiple people living there, including a young grandchild), having his efforts to get things done interrupted by the needs of others, and a perceived loss of control gradually generalized to even mundane circumstances, as often occurs with traumatic responses. In short, he was chronically overwhelmed and not experiencing the beginnings of dementia.

For Mr. J, neuropsychological testing helped define the focus and course of therapy. If he had been diagnosed with a major neurocognitive disorder, therapy might have taken a more acceptance and grief-based approach, to help him adjust to a chronic, potentially life-limiting condition. Because this diagnosis was ruled out, and his cognitive complaints were determined to be secondary to a core diagnosis of PTSD, therapy instead focused on treating PTSD.

Continue to: Case 2

Case 2

A 55-year-old with bipolar I disorder

Mr. S, age 55, is taken to the emergency department (ED) because of his complaints of a severe headache. While undergoing brain MRI, Mr. S becomes highly agitated and aggressive to the radiology staff and is transferred to the psychiatric inpatient unit. He has a history of bipolar disorder that was treated with lithium approximately 20 years ago. Due to continued agitation, he is transferred to the state hospital and prescribed multiple medications, including an unspecified first-generation antipsychotic (FGA) that results in drooling and causes him to stoop and shuffle.

Mr. S’s wife contacts a community psychiatrist after becoming frustrated by her inability to communicate with the staff at the state hospital. During a 1-hour consult, she reveals that Mr. S was a competitive speedboat racer and had suffered numerous concussions due to accidents; at least 3 of these concussions that occurred when he was in his 20s and 30s had included a loss of consciousness. Mr. S had always been treated in the ED, and never required hospitalization. He had a previous marriage, was estranged from his ex-wife and 3 children, and has a history of alcohol abuse.

The MRI taken in the ED reveals numerous patches of scar tissue throughout the cortex, most notably in the striatum areas. The psychiatrist suspects that Mr. S’s agitation and irritation were related to focal seizure activity. He encourages Mr. S’s wife to speak with the attending psychiatrist at the state hospital and ask for him to be discharged home under her care.

Eventually, Mr. S is referred for a neurologic consult and neuropsychological testing. The testing included measures of attention and working, learning and memory, and executive functioning. The results reveal numerous deficits that Mr. S had been able to compensate for when he was younger, including problems with recall of newly learned information and difficulty modifying his behavior according to feedback. Mr. S is weaned from high doses of the FGA and is stabilized on 2 antiepileptic agents, sertraline, and low-dose olanzapine. A rehabilitation plan is developed, and Mr. S remains out of the hospital.

A team-based approach

Psychiatric clinicians need to recognize the subtle as well as overt cognitive deficits present in patients with many of the illnesses that we treat on a daily basis. In this era of performance- and value-based care, it is important to understand the common neuropsychological tests available to assist in providing patient-centered care tailored to specific cognitive deficits. Including a neuropsychologist is essential to implementing a team-based approach.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Neuropsychological testing can help pinpoint key cognitive deficits that interfere with the potential for optimal patient outcomes. Psychiatric clinicians need to be knowledgeable about the common tests used and how to incorporate the results into their diagnosis and treatment plans.

Related Resources

- The American Academy of Clinical Neuropsychology. www.theaacn.org.

- Schwarz L. Answers to 7 questions about using neuropsychological testing in your practice. Current Psychiatry. 2014;13(3):33-39.

Drug Brand Names

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Sertraline • Zoloft

We have all treated a patient for whom you know you had the diagnosis correct, the medication regimen was working, and the patient adhered to treatment, but something was still “off.” There was something cognitively that wasn’t right, and you had identified subtle (and some overt) errors in the standard psychiatric cognitive assessment that didn’t seem amenable to psychotropic medications. Perhaps what was needed was neuropsychological testing, one of the most useful but underutilized resources available to help fine-tune diagnosis and treatment. Finding a neuropsychologist who is sensitive to the unique needs of patients with psychiatric disorders, and knowing what and how to communicate the clinical picture and need for the referral, can be challenging due to the limited availability, time, and cost of a full battery of standardized tests.

This article describes the purpose of neuropsychological testing, why it is an important part of psychiatry, and how to make the best use of it.

What is neuropsychological testing?

Neuropsychological testing is a comprehensive evaluation designed to assess cognitive functioning, such as attention, language, learning, memory, and visuospatial and executive functioning. Neuropsychology has its own vocabulary and lexicon that are important for psychiatric clinicians to understand. Some terms, such as aphasia, working memory, and dementia, are familiar to many clinicians. However, others, such as information processing speed, performance validity testing, and semantic memory, might not be. Common neuropsychological terms are defined in Table 1.

The neuropsychologist’s role

A neuropsychologist is a psychologist with advanced training in brain-behavior relationships who can help determine if cognitive problems are related to neurologic, medical, or psychiatric factors. A neuropsychological evaluation can identify the etiology of a patient’s cognitive difficulties, such as stroke, poorly controlled diabetes, or mental health symptoms, to help guide treatment. It can be difficult to determine if a patient who is experiencing significant cognitive, functional, or behavioral changes has an underlying cognitive disorder (eg, dementia or major neurocognitive disorder) or something else, such as a psychiatric condition. Indeed, many psychiatric conditions, including schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and major depressive disorder (MDD), can present with significant cognitive difficulties. Thus, when patients report an increase in forgetfulness or changes in their ability to care for themselves, neuropsychological testing can help determine the cause.

How to refer to a neuropsychologist

Developing a referral network with a neuropsychologist should be a component of establishing a psychiatric practice. A neuropsychologist can help identify deficits that may interfere with the patient’s ability to adhere to a treatment plan, monitor medications, or actively participate in treatment and therapy. When making a referral for neuropsychological testing, it is important to be clear about the specific concerns so the neuropsychologist knows how to best evaluate the patient. A psychiatric clinician does not order specific neuropsychological tests, but thoroughly describes the problem so the neuropsychologist can determine the appropriate tests after interviewing the patient. For example, if a patient reports memory problems, it is essential to give the neuropsychologist specific clinical data so he/she can determine if the symptoms are due to a neurodegenerative or psychiatric condition. Then, after interviewing the patient (and, possibly, a family member), the neuropsychologist can construct a battery of tests to best answer the question.

Which neuropsychological tests are available?

There is a large battery of neuropsychological tests that require a licensed psychologist to administer and interpret.1 Those commonly used in research and practice to differentiate neurologically-based cognitive deficits associated with psychiatric disorders include the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-4th edition (WAIS-IV) for assessing intelligence, the California Verbal Learning Test-Third Edition (CVLT-3) for verbal memory and learning, the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised for visual memory, the Wisconsin Card Sorting Test (WCST) for executive functions, and the Ruff 2&7 Selective Attention Test for sustained attention.2 These and other commonly used tests are described in Table 2.1

Neuropsychological testing vs psychological testing

The neuropsychologist will use psychometric properties (such as the validity and reliability of the test) and available normative data to pick the most appropriate tests. To date, there are no specific tests that clearly delineate psychiatric from nonpsychiatric etiologies, although the Screen for Cognitive Impairment in Psychiatry (SCIP)3 was developed in 2013 to explore cognitive abilities in the functional psychoses; it is beginning to be used in other studies.4,5 The neuropsychologist will consider the patient’s current concerns, the onset and progression of these concerns, and the pattern in testing behavior to help determine if psychiatric conditions are the most likely etiology.

Continue to: In addition to cognitive tests...

In addition to cognitive tests, the neuropsychologist might also administer psychological tests. These might include commonly used screening tools such as the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9)6 or Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS),7 or more comprehensive objective personality measures, such as the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory-2-Restructured Format (MMPI-2-RF)8 or Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI).9 These tests, along with a thorough clinical history, can help identify if a psychiatric condition is present. In addition, for the more extensive tests such as the MMPI-2-RF or PAI, there are certain neuropsychological profiles that are consistent with a psychiatric etiology for cognitive difficulties. These profiles are formulated based on specific test scores in combination with complex patient variables.

Understanding the report

While there will be stylistic differences in reports depending on the neuropsychologist’s setting, referral source, and personal preferences, most will include discussion of why the patient was referred for evaluation and a description of the onset and progression of the problem.10 Reports often also include pertinent medical and psychiatric history, substance use history, and family medical history. A section on social history is important to help establish premorbid functioning, and might include information about prenatal/birth complications, developmental milestones, educational history, and occupational history. Information about current psychosocial support or stressors, including marital status or current/past legal issues, can be helpful. In addition to this history, there is often a section on behavioral observations, especially if anything stood out or might have affected the validity of the data.

There are also objective measures of validity that the neuropsychologist might administer to evaluate whether the results are valid. Issues of validity are monitored through the evaluation, and are used to determine if the results are consistent with known neurologic patterns. If the results are deemed not valid, then low scores cannot be reliably interpreted as evidence of impairment. This is akin to an arm moving during an X-ray, thereby blurring the results. If valid, the results of objective testing are include in the neuropsychologist’s report; this can range from providing raw scores, standard scores, and/or percentiles to a general description of how the patient did on testing.

The section that is usually of most interest to psychiatric clinicians is the summary, which explains the results, might offer a diagnosis, and discusses possible etiologies. This might be where the neuropsychologist discusses if the findings are due to a neurologic or psychiatric condition. From this comes the neuropsychologist’s recommendations. When a psychiatric condition is determined to be the underlying etiology, the neuropsychologist might recommend psychotherapy or some other psychiatric treatment.

Why is neuropsychological testing important?

Schizophrenia, MDD, bipolar disorder, and PTSD produce significant neurobiologic changes that often result in deterioration of a patient’s global cognitive function. Increased emphasis and attention in psychiatric research have yielded more clues to the neurobiology of cognition. However, even though many psychiatric clinicians are trained in cognitive assessments, such as the “clock test,” “serial sevens,” “numbers forward and backward,” “proverb,” and “word recall,” and common scenarios to evaluate judgment and insight, such as “mailing a letter” and “smoke in a movie theatre,” most of these components are not completed during a standard psychiatric evaluation. Because the time allotted to completing a psychiatric evaluation continues to be shortened, it is sometimes difficult to complete the “6 bullets” required by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services as part of the mental status exam (Table 311).

Continue to: To date, the best evidence...

To date, the best evidence for neuropsychological deficits exists for patients with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, MDD, and PTSD.12,13 The Box2,14-24 describes the findings of studies of neuropsychological deficits in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder.

Box

Patients with schizophrenia have been the subjects of neuropsychological testing for decades. The results have shown deficits on many standardized tests, including those of attention, memory, and executive functioning, although some patients might perform within normal limits.15

A federal initiative through the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) known as MATRICS (Measurement and Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia) was developed in the late 1990s to develop consensus on the underlying cognitive deficits in schizophrenia. MATRICS was created with the hopes that it would allow the FDA to approve treatments for those cognitive deficits independent of psychosis because current psychotropic medications have minimal efficacy on cognition.16,17 The MATRICS group identified working memory, attention/vigilance, verbal learning and memory, visual learning and memory, speed of processing, reasoning and problem solving, and social cognition as the key cognitive domains most affected in schizophrenia.14 The initial program has since evolved into 3 distinct NIMH programs: CNTRICS18 (Cognitive Neuroscience Treatment Research to Improve Cognition in Schizophrenia), TURNS19 (Treatment Units for Research on Neurocognition in Schizophrenia), and TENETS20 (Treatment and Evaluation Network for Trials in Schizophrenia). The combination of neuropsychological testing and neuroimaging has led to the conceptualization of schizophrenia as a neurodevelopmental disorder.

Individuals at risk for psychosis

As clinicians, we have long heard from parents of children with schizophrenia a standard trajectory of functional decline: early premorbid changes, a fairly measurable prodromal period marked by subtle deterioration in cognitive functioning, followed by the actual illness trajectory. In a recent meta-analysis, researchers compared the results of 60 neuropsychological tests comprising 9 domains in people who were at clinical high risk for psychosis who eventually converted to a psychotic disorder (CHR-P), those at clinical high risk who did not convert to psychosis (CHR-NP), and healthy controls.21 They found that neuropsychological performance deficits were greater in CHR-P individuals than in those in the CHR-NP group, and both had greater deficits than healthy controls.

For many patients with schizophrenia, full cognitive maturation is never reached.22 In general, decreased motivation in schizophrenia has been correlated with neurocognitive deficits.23

Schizophrenia vs bipolar disorder

In a study comparing neuropsychological functioning in patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder with psychotic features (BP-P), researchers found greater deficits in schizophrenia, including immediate verbal recall, working memory, processing speed, and verbal fluency.22 Patients with BP-P demonstrated impairment consistent with generalized impairment in verbal learning and memory, working memory, and processing speed.22

Children/adolescents

In a recent study comparing child and adolescent offspring of patients with schizophrenia (n = 41) and bipolar disorder (n = 90), researchers identified neuropsychological deficits in visual memory for both groups, suggesting common genetic linkages. The schizophrenia offspring scored lower in verbal memory and word memory, while bipolar offspring scored lower on the processing speed index and visual memory.2

Information processing

Another study compared the results of neuropsychological testing and the P300 component of auditory event-related potential (an electrophysiological measure) in 30 patients with schizophrenia, siblings without illness, and normal controls.24 The battery of neuropsychological tests included the Digit Symbol Substitution Test, Digit Vigilance Test, Trail Making Test-B, and Stroop test. The P300 is well correlated with information processing. Researchers found decreased P300 amplitude and latency in the patients and normal levels in the controls; siblings scored somewhere in between.24 Scores on the neuropsychological tests were consistently below normal in both patients and their siblings, with patients scoring the lowest.24

Continue to: Neuropsychological testing

Neuropsychological testing: 2 Case studies

The following 2 cases illustrate the pivotal role of neuropsychological testing in formulating an accurate differential diagnosis, and facilitating improved outcomes.

Case 1

A veteran with PTSD and memory complaints

Mr. J, age 70, is a married man who spent his career in the military, including combat service in the Vietnam War. His service in Vietnam included an event in which he couldn’t save platoon members from an ambush and death in a firefight, after which he developed PTSD. He retired after 25 years of service.

Mr. J’s psychiatrist refers him to a neuropsychologist for complaints of memory difficulties, including a fear that he’s developing Alzheimer’s disease (AD). Because of the concern for AD, he undergoes tests of learning and memory, such as the CVLT-3, the Brief Visuospatial Memory Test-Revised, and the Logical Memory subtest from the Wechsler Memory Scale–4th Edition. Other tests include a measure of confrontation naming, verbal fluency (phonemic and semantic fluency), construction, attention, processing speed, and problem solving. In addition, a measure of psychiatric and emotional functioning is also administered (the MMPI-2-RF).