User login

Welcome to Current Psychiatry, a leading source of information, online and in print, for practitioners of psychiatry and its related subspecialties, including addiction psychiatry, child and adolescent psychiatry, and geriatric psychiatry. This Web site contains evidence-based reviews of the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of mental illness and psychological disorders; case reports; updates on psychopharmacology; news about the specialty of psychiatry; pearls for practice; and other topics of interest and use to this audience.

Dear Drupal User: You're seeing this because you're logged in to Drupal, and not redirected to MDedge.com/psychiatry.

Depression

adolescent depression

adolescent major depressive disorder

adolescent schizophrenia

adolescent with major depressive disorder

animals

autism

baby

brexpiprazole

child

child bipolar

child depression

child schizophrenia

children with bipolar disorder

children with depression

children with major depressive disorder

compulsive behaviors

cure

elderly bipolar

elderly depression

elderly major depressive disorder

elderly schizophrenia

elderly with dementia

first break

first episode

gambling

gaming

geriatric depression

geriatric major depressive disorder

geriatric schizophrenia

infant

kid

major depressive disorder

major depressive disorder in adolescents

major depressive disorder in children

parenting

pediatric

pediatric bipolar

pediatric depression

pediatric major depressive disorder

pediatric schizophrenia

pregnancy

pregnant

rexulti

skin care

teen

wine

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-current-psychiatry')]

div[contains(@class, 'panel-panel-inner')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-node-field-article-topics')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

2019 Peer Reviewers

Aparna Atluru, MD

Stanford Medicine

Anjan Bhattacharyya, MD

Saint Louis University

Caroline Bonham, MD

The University of New Mexico

Catherine Crone, MD

Inova Health System

Sheila Dowd, PhD

Rush Medical College

Ahmed Z. Elmaadawi, MD

Indiana University School of Medicine

Donald Gilbert, MD, MS

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Mark Gold, MD

Washington University in St. Louis

Elana Harris, MD, PhD

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Susan Hatters-Friedman, MD

Case Western Reserve University

Faisal Islam, MD, MBA

Greenvale, New York

Kaustubh G. Joshi, MD

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

Rita Khoury, MD

Saint George Hospital University Medical Center

Suneeta Kumari, MD, MPH

Howard University Hospital

Michelle Magid, MD

Austin PsychCare PA

Michael Maksimowski, MD

Wayne State University

Jose Maldonado, MD

Stanford University

Thomas W. Meeks, MD

Portland VA Medical Center

John Miller, MD

University of South Florida

Armando Morera-Fumero, MD, PhD

Universidad de La Laguna

Mary K. Morreale, MD

Wayne State University

Philip Muskin, MD

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Katharine Nelson, MD

University of Minnesota

Carol North, MD

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas

Douglas Opler, MD

Rutgers University School of Medicine

Joseph Pierre, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

Jerrold Pollak, PhD, ABN, ABPP

Seacoast Mental Health Center

Edwin Raffi, MD, MPH

Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health

Y. Pritham Raj, MD

Oregon Health and Science University

Jeffrey Rakofsky, MD

Emory University School of Medicine

Laura Ramsey, PhD

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Erica Rapp, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Abhishek Reddy, MD

The University of Alabama at Birmingham

Eduardo Rueda Vasquez, MD

Williamsport, Pennsylvania

Stephen Saklad, PharmD, BCPP

The University of Texas at Austin

Lauren Schwarz, PhD, ABPP-CN

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

Andreas Sidiropoulos, MD

University of Michigan

Shirshendu Sinha, MD

Mayo Clinic Health System and Mayo Clinic

Cornel Stanciu, MD

Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine

Jeffrey Sung, MD

University of Washington

Thida Thant, MD

University of Colorado at Denver

Adele Viguera, MD

Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine

Aparna Atluru, MD

Stanford Medicine

Anjan Bhattacharyya, MD

Saint Louis University

Caroline Bonham, MD

The University of New Mexico

Catherine Crone, MD

Inova Health System

Sheila Dowd, PhD

Rush Medical College

Ahmed Z. Elmaadawi, MD

Indiana University School of Medicine

Donald Gilbert, MD, MS

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Mark Gold, MD

Washington University in St. Louis

Elana Harris, MD, PhD

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Susan Hatters-Friedman, MD

Case Western Reserve University

Faisal Islam, MD, MBA

Greenvale, New York

Kaustubh G. Joshi, MD

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

Rita Khoury, MD

Saint George Hospital University Medical Center

Suneeta Kumari, MD, MPH

Howard University Hospital

Michelle Magid, MD

Austin PsychCare PA

Michael Maksimowski, MD

Wayne State University

Jose Maldonado, MD

Stanford University

Thomas W. Meeks, MD

Portland VA Medical Center

John Miller, MD

University of South Florida

Armando Morera-Fumero, MD, PhD

Universidad de La Laguna

Mary K. Morreale, MD

Wayne State University

Philip Muskin, MD

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Katharine Nelson, MD

University of Minnesota

Carol North, MD

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas

Douglas Opler, MD

Rutgers University School of Medicine

Joseph Pierre, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

Jerrold Pollak, PhD, ABN, ABPP

Seacoast Mental Health Center

Edwin Raffi, MD, MPH

Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health

Y. Pritham Raj, MD

Oregon Health and Science University

Jeffrey Rakofsky, MD

Emory University School of Medicine

Laura Ramsey, PhD

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Erica Rapp, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Abhishek Reddy, MD

The University of Alabama at Birmingham

Eduardo Rueda Vasquez, MD

Williamsport, Pennsylvania

Stephen Saklad, PharmD, BCPP

The University of Texas at Austin

Lauren Schwarz, PhD, ABPP-CN

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

Andreas Sidiropoulos, MD

University of Michigan

Shirshendu Sinha, MD

Mayo Clinic Health System and Mayo Clinic

Cornel Stanciu, MD

Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine

Jeffrey Sung, MD

University of Washington

Thida Thant, MD

University of Colorado at Denver

Adele Viguera, MD

Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine

Aparna Atluru, MD

Stanford Medicine

Anjan Bhattacharyya, MD

Saint Louis University

Caroline Bonham, MD

The University of New Mexico

Catherine Crone, MD

Inova Health System

Sheila Dowd, PhD

Rush Medical College

Ahmed Z. Elmaadawi, MD

Indiana University School of Medicine

Donald Gilbert, MD, MS

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Mark Gold, MD

Washington University in St. Louis

Elana Harris, MD, PhD

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital

Susan Hatters-Friedman, MD

Case Western Reserve University

Faisal Islam, MD, MBA

Greenvale, New York

Kaustubh G. Joshi, MD

University of South Carolina School of Medicine

Rita Khoury, MD

Saint George Hospital University Medical Center

Suneeta Kumari, MD, MPH

Howard University Hospital

Michelle Magid, MD

Austin PsychCare PA

Michael Maksimowski, MD

Wayne State University

Jose Maldonado, MD

Stanford University

Thomas W. Meeks, MD

Portland VA Medical Center

John Miller, MD

University of South Florida

Armando Morera-Fumero, MD, PhD

Universidad de La Laguna

Mary K. Morreale, MD

Wayne State University

Philip Muskin, MD

Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons

Katharine Nelson, MD

University of Minnesota

Carol North, MD

University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center at Dallas

Douglas Opler, MD

Rutgers University School of Medicine

Joseph Pierre, MD

University of California, Los Angeles

Jerrold Pollak, PhD, ABN, ABPP

Seacoast Mental Health Center

Edwin Raffi, MD, MPH

Massachusetts General Hospital Center for Women’s Mental Health

Y. Pritham Raj, MD

Oregon Health and Science University

Jeffrey Rakofsky, MD

Emory University School of Medicine

Laura Ramsey, PhD

Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center

Erica Rapp, MD

University of Colorado School of Medicine

Abhishek Reddy, MD

The University of Alabama at Birmingham

Eduardo Rueda Vasquez, MD

Williamsport, Pennsylvania

Stephen Saklad, PharmD, BCPP

The University of Texas at Austin

Lauren Schwarz, PhD, ABPP-CN

Saint Louis University School of Medicine

Andreas Sidiropoulos, MD

University of Michigan

Shirshendu Sinha, MD

Mayo Clinic Health System and Mayo Clinic

Cornel Stanciu, MD

Dartmouth’s Geisel School of Medicine

Jeffrey Sung, MD

University of Washington

Thida Thant, MD

University of Colorado at Denver

Adele Viguera, MD

Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine

AI and machine learning

Recent advances in neuroscience and genetics are providing a new view of brain function in health and disease.1 As discussed in Drs. Hripsime Kalanderian and Henry Nasrallah’s article “Artificial intelligence in psychiatry” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

In a 2016 article, Dr. Arshya Vahabzadeh2 wrote, “In the near term, humans will continue to make the majority of psychiatric diagnoses and provide treatment.” He predicted that data science—specifically machine learning—will help revolutionize how we diagnose, treat, and monitor depression. He foresees a future where AI machines or learning machines will more accurately diagnose and treat depression.

These predictions remind us of the promises made with the introduction of psychoactive drugs to the practice of psychiatry. In the 1970s, the increased emphasis on neurotransmitters led to new biologic models of mental illness and the expansion of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The increased use of psychoactive medications relegated the practice of psychotherapy to other mental health professionals. Psychiatry became a “drug-intensive” specialty, and psychiatrists saw themselves as psychopharmacologists.3 During this time, psychiatry became progressively dominated by the pharmaceutical industry. The deregulation of the markets and the for-profit ideology of the pharmaceutical industry resulted in an economically and mutually beneficial alliance between pharmaceutical companies, academic faculty, and individual psychiatrists.

Using the same for-profit ideology and ethics of the pharmaceutical industry, technology-based corporations are making massive investments in the application of these technologies in neuroscience research and clinical practice. The “promise” that AI will diagnose and treat depression more accurately than clinicians will again radically change the psychiatrist’s role. Most of a psychiatrist’s clinical work eventually will be replicated by machine learning and technicians. The human-to-human encounter that is at core of the profession will be replaced by the machine-to-human encounter.4

From the social economic perspective, the American health care system is designed to increase profit and maximize the earnings of the industries.5 Unless social policy changes, expensive new technologies will increase the cost and limit accessibility to health care, benefiting the few at the expense of the majority of people. These technologies will produce a robust return on investment, but the wealth they create will benefit fewer and fewer people.

Several writers have called attention to the social, economic, and ethical consequences of these advances and recommended that the academics and technologists who support AI and machine learning in medicine must “receive sufficient training in ethics” and gain exposure to social and economic issues.6 Darcy et al7 warns of the risks of introducing these advanced technologies in medicine: “As machine learning enters the state-of-the-art clinical practice, medicine thus has the immense obligation to ensure that this technology is harnessed for societal and individual good, fulfilling the ethical basis of the profession.… Ethical design thinking is essential at every stage of development and application of machine learning in advancing health. Toward this

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, Private Practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bargeman CI. How the new neuroscience will advance medicine. JAMA. 2015;314(3):221-222.

2. Vahabzadeh A. Can machine learning decode depression? Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.4a3. Published April 11, 2016. Accessed October 16, 2019.

3. Angell M. The illusions of psychiatry. The New York Review. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2011/07/14/illusions-of-psychiatry/. Published July 14, 2011. Accessed October 16, 2019.

4. Heath I, Nessa J. Objectification of physicians and loss of therapeutic power. Lancet. 2007;369(9565):886-888.

5. Wang D. Health care, American style: how did we arrive? Where will we go? Psychiatric Annals. 2014;44(7):342-348.

6. Nourbakhsh IR. The coming robot dystopia. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2015-06-16/coming-robot-dystopia. Published July 2015. Accessed October 16, 2019.

7. Darcy AM, Louie AK, Roberts LW. Machine learning and the profession of medicine. JAMA. 2016;315(6):551-552.

Recent advances in neuroscience and genetics are providing a new view of brain function in health and disease.1 As discussed in Drs. Hripsime Kalanderian and Henry Nasrallah’s article “Artificial intelligence in psychiatry” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

In a 2016 article, Dr. Arshya Vahabzadeh2 wrote, “In the near term, humans will continue to make the majority of psychiatric diagnoses and provide treatment.” He predicted that data science—specifically machine learning—will help revolutionize how we diagnose, treat, and monitor depression. He foresees a future where AI machines or learning machines will more accurately diagnose and treat depression.

These predictions remind us of the promises made with the introduction of psychoactive drugs to the practice of psychiatry. In the 1970s, the increased emphasis on neurotransmitters led to new biologic models of mental illness and the expansion of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The increased use of psychoactive medications relegated the practice of psychotherapy to other mental health professionals. Psychiatry became a “drug-intensive” specialty, and psychiatrists saw themselves as psychopharmacologists.3 During this time, psychiatry became progressively dominated by the pharmaceutical industry. The deregulation of the markets and the for-profit ideology of the pharmaceutical industry resulted in an economically and mutually beneficial alliance between pharmaceutical companies, academic faculty, and individual psychiatrists.

Using the same for-profit ideology and ethics of the pharmaceutical industry, technology-based corporations are making massive investments in the application of these technologies in neuroscience research and clinical practice. The “promise” that AI will diagnose and treat depression more accurately than clinicians will again radically change the psychiatrist’s role. Most of a psychiatrist’s clinical work eventually will be replicated by machine learning and technicians. The human-to-human encounter that is at core of the profession will be replaced by the machine-to-human encounter.4

From the social economic perspective, the American health care system is designed to increase profit and maximize the earnings of the industries.5 Unless social policy changes, expensive new technologies will increase the cost and limit accessibility to health care, benefiting the few at the expense of the majority of people. These technologies will produce a robust return on investment, but the wealth they create will benefit fewer and fewer people.

Several writers have called attention to the social, economic, and ethical consequences of these advances and recommended that the academics and technologists who support AI and machine learning in medicine must “receive sufficient training in ethics” and gain exposure to social and economic issues.6 Darcy et al7 warns of the risks of introducing these advanced technologies in medicine: “As machine learning enters the state-of-the-art clinical practice, medicine thus has the immense obligation to ensure that this technology is harnessed for societal and individual good, fulfilling the ethical basis of the profession.… Ethical design thinking is essential at every stage of development and application of machine learning in advancing health. Toward this

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, Private Practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

Recent advances in neuroscience and genetics are providing a new view of brain function in health and disease.1 As discussed in Drs. Hripsime Kalanderian and Henry Nasrallah’s article “Artificial intelligence in psychiatry” (Evidence-Based Reviews,

In a 2016 article, Dr. Arshya Vahabzadeh2 wrote, “In the near term, humans will continue to make the majority of psychiatric diagnoses and provide treatment.” He predicted that data science—specifically machine learning—will help revolutionize how we diagnose, treat, and monitor depression. He foresees a future where AI machines or learning machines will more accurately diagnose and treat depression.

These predictions remind us of the promises made with the introduction of psychoactive drugs to the practice of psychiatry. In the 1970s, the increased emphasis on neurotransmitters led to new biologic models of mental illness and the expansion of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. The increased use of psychoactive medications relegated the practice of psychotherapy to other mental health professionals. Psychiatry became a “drug-intensive” specialty, and psychiatrists saw themselves as psychopharmacologists.3 During this time, psychiatry became progressively dominated by the pharmaceutical industry. The deregulation of the markets and the for-profit ideology of the pharmaceutical industry resulted in an economically and mutually beneficial alliance between pharmaceutical companies, academic faculty, and individual psychiatrists.

Using the same for-profit ideology and ethics of the pharmaceutical industry, technology-based corporations are making massive investments in the application of these technologies in neuroscience research and clinical practice. The “promise” that AI will diagnose and treat depression more accurately than clinicians will again radically change the psychiatrist’s role. Most of a psychiatrist’s clinical work eventually will be replicated by machine learning and technicians. The human-to-human encounter that is at core of the profession will be replaced by the machine-to-human encounter.4

From the social economic perspective, the American health care system is designed to increase profit and maximize the earnings of the industries.5 Unless social policy changes, expensive new technologies will increase the cost and limit accessibility to health care, benefiting the few at the expense of the majority of people. These technologies will produce a robust return on investment, but the wealth they create will benefit fewer and fewer people.

Several writers have called attention to the social, economic, and ethical consequences of these advances and recommended that the academics and technologists who support AI and machine learning in medicine must “receive sufficient training in ethics” and gain exposure to social and economic issues.6 Darcy et al7 warns of the risks of introducing these advanced technologies in medicine: “As machine learning enters the state-of-the-art clinical practice, medicine thus has the immense obligation to ensure that this technology is harnessed for societal and individual good, fulfilling the ethical basis of the profession.… Ethical design thinking is essential at every stage of development and application of machine learning in advancing health. Toward this

Marco T. Carpio, MD

Psychiatrist, Private Practice

Lynbrook, New York

Disclosure: The author reports no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

1. Bargeman CI. How the new neuroscience will advance medicine. JAMA. 2015;314(3):221-222.

2. Vahabzadeh A. Can machine learning decode depression? Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.4a3. Published April 11, 2016. Accessed October 16, 2019.

3. Angell M. The illusions of psychiatry. The New York Review. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2011/07/14/illusions-of-psychiatry/. Published July 14, 2011. Accessed October 16, 2019.

4. Heath I, Nessa J. Objectification of physicians and loss of therapeutic power. Lancet. 2007;369(9565):886-888.

5. Wang D. Health care, American style: how did we arrive? Where will we go? Psychiatric Annals. 2014;44(7):342-348.

6. Nourbakhsh IR. The coming robot dystopia. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2015-06-16/coming-robot-dystopia. Published July 2015. Accessed October 16, 2019.

7. Darcy AM, Louie AK, Roberts LW. Machine learning and the profession of medicine. JAMA. 2016;315(6):551-552.

1. Bargeman CI. How the new neuroscience will advance medicine. JAMA. 2015;314(3):221-222.

2. Vahabzadeh A. Can machine learning decode depression? Psychiatric News. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2016.4a3. Published April 11, 2016. Accessed October 16, 2019.

3. Angell M. The illusions of psychiatry. The New York Review. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/2011/07/14/illusions-of-psychiatry/. Published July 14, 2011. Accessed October 16, 2019.

4. Heath I, Nessa J. Objectification of physicians and loss of therapeutic power. Lancet. 2007;369(9565):886-888.

5. Wang D. Health care, American style: how did we arrive? Where will we go? Psychiatric Annals. 2014;44(7):342-348.

6. Nourbakhsh IR. The coming robot dystopia. Foreign Affairs. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/2015-06-16/coming-robot-dystopia. Published July 2015. Accessed October 16, 2019.

7. Darcy AM, Louie AK, Roberts LW. Machine learning and the profession of medicine. JAMA. 2016;315(6):551-552.

The woman who couldn’t stop eating

CASE Uncontrollable eating and weight gain

Ms. C, age 33, presents to an outpatient clinic with complaints of weight gain and “uncontrollable eating.” Ms. C says she’s gained >50 lb over the last year. She describes progressively frequent episodes of overeating during which she feels that she has no control over the amount of food she consumes. She reports eating as often as 10 times a day, and overeating to the point of physical discomfort during most meals. She gives an example of having recently consumed a large pizza, several portions of Chinese food, approximately 20 chicken wings, and half a chocolate cake for dinner. Ms. C admits that on several occasions she has vomited after meals due to feeling extremely full; however, she denies having done so intentionally. She also denies restricting her food intake, misusing laxatives or diuretics, or exercising excessively.

Ms. C expresses frustration and embarrassment with her eating and resulting weight gain. She says she has poor self-esteem, low energy and motivation, and poor concentration. She feels that her condition has significantly impacted her social life, romantic relationships, and family life. She admits she’s been avoiding dating and seeing friends due to her weight gain, and has been irritable with her teenage daughter.

During her initial evaluation, Ms. C is alert and oriented, with a linear and goal-directed thought process. She is somewhat irritable and guarded, wearing large sunglasses that cover most of her face, but is not overtly paranoid. Although she appears frustrated when discussing her condition, she denies feeling hopeless or helpless.

HISTORY Thyroid cancer and mood swings

Ms. C, who is single and unemployed, lives in an apartment with her teenage daughter, with whom she describes having a good relationship. She has been receiving disability benefits for the past 2 years after a motor vehicle accident resulted in multiple fractures of her arm and elbow, and subsequent chronic pain. Ms. C reports a distant history of “problems with alcohol,” but denies drinking any alcohol since being charged with driving under the influence several years ago. She has a 10 pack-year history of smoking and denies any history of illicit drug use.

Two years ago, Ms. C was diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma, and treated with surgical resection and a course of radiation. She has regular visits with her endocrinologist and has been prescribed oral levothyroxine, 150 mcg/d.

Ms. C reports a history of “mood swings” characterized by “snapping at people” and becoming irritable in response to stressful situations, but denies any past symptoms consistent with a manic or hypomanic episode. Ms. C has not been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, nor has she received any prior psychiatric treatment. She reluctantly discloses that approximately 3 years ago she had a less severe episode of uncontrollable eating and weight gain (20 to 30 lb). At that time, she was able to regain her desired physical appearance by going on the “Subway diet” and undergoing liposuction and plastic surgery.

At her current outpatient clinic visit, Ms. C expresses an interest in exploring bariatric surgery as a potential solution to her weight gain.

[polldaddy:10446186]

Continue to: EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

We refer Ms. C for a physical examination and routine blood analysis to rule out any medical contributors to her condition. Her physical examination is reported as normal, with no signs of skin changes, goiter, or exophthalmos. Ms. C is noted to be obese, with a body mass index of 37.2 kg/m2, and an abdominal circumference of 38.5 in.

A blood analysis shows that Ms. C has elevated triglyceride levels (202 mg/dL) and elevated cholesterol levels (210 mg/dL). Her thyroid function tests are within normal limits based on the dose of levothyroxine she’s been receiving. A pregnancy test is negative.

Ms. C gives the team at the clinic permission to contact her endocrinologist, who reports that he does not suspect that Ms. C’s drastic weight gain and abnormal eating patterns are attributable to her history of thyroid carcinoma because her thyroid function tests have been stable on her current regimen.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. C’s initial presentation, we strongly suspected a diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED). Several differential diagnoses were considered and carefully ruled out; Ms. C’s medical workup did not suggest that her weight gain was due to an active medical condition, and she did not meet DSM-5 criteria for a mood or psychotic disorder or anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

With an estimated lifetime prevalence in the United States of 2.6%, BED is the most prevalent eating disorder (compared with 0.6% for anorexia nervosa and 1% for bulimia nervosa).1 BED is more prevalent in women than in men, and the mean age of onset is mid-20s.

Continue to: BED may be difficult...

BED may be difficult to detect because patients may feel ashamed or guilty and are often hesitant to disclose and discuss their symptoms. Furthermore, they are frequently frustrated by the subjective loss of control over their behaviors. Patients with BED often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics.

Screening for eating disorders

Several screening instruments have been developed to help clinicians identify patients who may need further evaluation for possible diagnosis of an eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and BED.2 The SCOFF questionnaire is composed of 5 brief clinician-administered questions to screen for eating disorders.2 The 7-item Binge Eating Disorder Screener (BED-7) is a screening instrument specific for BED that examines a patient’s eating patterns and behaviors during the past 3 months.3

In general, suspect BED in patients who have significant weight dissatisfaction, fluctuation in weight, and depressive symptoms. The DSM-5 criteria for binge eating disorder are shown in Table 14.

BED and comorbid psychiatric disorders

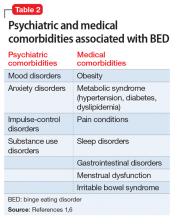

Patients with BED are more likely than the general population to have comorbid psychiatric disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. Swanson et al5 found that 83.5% of adolescents who met criteria for BED also met criteria for at least 1 other psychiatric disorder, and 37% endorsed >3 concurrent psychiatric conditions. Once BED is confirmed, it is important to screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities that are often present in individuals with BED (Table 21,6).

The rates of diagnosis and treatment of BED remain low. This is likely due to patient factors such as shame and fear of stigma and clinician factors such as lack of awareness, ineffective communication, hesitation to discuss the sensitive topic, or insufficient knowledge about treatment options once BED is diagnosed.

[polldaddy:10446187]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

Ms. C is ambivalent about her BED diagnosis, and becomes angry about it when the proposed treatments do not involve bariatric surgery or cosmetic procedures. Ms. C is enrolled in weekly individual psychotherapy, where she receives a combination of CBT and psychodynamic therapy; however, her attendance is inconsistent. Ms. C is offered a trial of fluoxetine, but adamantly refuses, citing a relative who experienced adverse effects while receiving this type of antidepressant. Ms. C also refuses a trial of topiramate due to concerns of feeling sedated. Finally, she is offered a trial of lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, which was FDA-approved in 2015 to treat moderate to severe BED. We discuss the risks, benefits, and adverse effects of lisdexamfetamine with Ms. C; however, she is hesitant to start this medication and expresses increasing interest in obtaining a consultation for bariatric surgery. Ms. C is provided with extensive education about the risks and dangers of surgery before addressing her eating patterns, and the clinician provides validation, verbal support, and counseling. Ms. C eventually agrees to a trial of lisdexamfetamine, but her insurance denies coverage of this medication.

The authors’ observations

When developing an individualized treatment plan for a patient with BED, the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities should be considered. Treatment goals for patients with BED include:

- abstinence from binge eating

- sustainable weight loss and metabolic health

- reduction in symptoms associated with comorbid conditions

- improvement in self-esteem and overall quality of life.

A 2015 comparative effectiveness review of management and outcomes for patients with BED evaluated pharmacologic, psychologic, behavioral, and combined approaches for treating patients with BED.7 The results suggested that second-generation antidepressants, topiramate, and lisdexamfetamine were superior to placebo in reducing binge-eating episodes and achieving abstinence from binge-eating. Weight reduction was also achieved with topiramate and lisdexamfetamine, and antidepressants helped relieve symptoms of comorbid depression.

Various formats of CBT, including therapist-led and guided self-help, were also superior to placebo in reducing the frequency of binge-eating and promoting abstinence; however, they were generally not effective in treating depression or reducing patients’ weight.7

OUTCOME Fixated on surgery

We appeal the decision of Ms. C’s insurance company; however, during the appeals process, Ms. C becomes increasingly irritable and informs us that she has changed her mind and, with the reported support of her medical doctors, wishes to undergo bariatric surgery. Although we made multiple attempts to engage Ms. C in further treatment, she is lost to follow-up.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Diagnosing and managing patients with binge eating disorder (BED) can be challenging because patients may hesitate to seek help, and/or have psychiatric and medical comorbidities. They often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics. Once BED is confirmed, screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities. A combination of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions can benefit some patients with BED, but treatment should be individualized.

Related Resources

- National Eating Disorders Association. NEDA. www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/.

- Safer D, Telch C, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2017.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358.

2. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1467-1468.

3. Herman BK, Deal LS, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Development of the 7-Item Binge-Eating Disorder screener (BEDS-7). Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(2):10.4088/PCC.15m01896. doi:10.4088/PCC.15m01896.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714.

6. Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Casuto LS, et al. Binge eating disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2017;40(2):255-266.

7. Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, et al. Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338312/. Published December 2015. Accessed July 29, 2019.

CASE Uncontrollable eating and weight gain

Ms. C, age 33, presents to an outpatient clinic with complaints of weight gain and “uncontrollable eating.” Ms. C says she’s gained >50 lb over the last year. She describes progressively frequent episodes of overeating during which she feels that she has no control over the amount of food she consumes. She reports eating as often as 10 times a day, and overeating to the point of physical discomfort during most meals. She gives an example of having recently consumed a large pizza, several portions of Chinese food, approximately 20 chicken wings, and half a chocolate cake for dinner. Ms. C admits that on several occasions she has vomited after meals due to feeling extremely full; however, she denies having done so intentionally. She also denies restricting her food intake, misusing laxatives or diuretics, or exercising excessively.

Ms. C expresses frustration and embarrassment with her eating and resulting weight gain. She says she has poor self-esteem, low energy and motivation, and poor concentration. She feels that her condition has significantly impacted her social life, romantic relationships, and family life. She admits she’s been avoiding dating and seeing friends due to her weight gain, and has been irritable with her teenage daughter.

During her initial evaluation, Ms. C is alert and oriented, with a linear and goal-directed thought process. She is somewhat irritable and guarded, wearing large sunglasses that cover most of her face, but is not overtly paranoid. Although she appears frustrated when discussing her condition, she denies feeling hopeless or helpless.

HISTORY Thyroid cancer and mood swings

Ms. C, who is single and unemployed, lives in an apartment with her teenage daughter, with whom she describes having a good relationship. She has been receiving disability benefits for the past 2 years after a motor vehicle accident resulted in multiple fractures of her arm and elbow, and subsequent chronic pain. Ms. C reports a distant history of “problems with alcohol,” but denies drinking any alcohol since being charged with driving under the influence several years ago. She has a 10 pack-year history of smoking and denies any history of illicit drug use.

Two years ago, Ms. C was diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma, and treated with surgical resection and a course of radiation. She has regular visits with her endocrinologist and has been prescribed oral levothyroxine, 150 mcg/d.

Ms. C reports a history of “mood swings” characterized by “snapping at people” and becoming irritable in response to stressful situations, but denies any past symptoms consistent with a manic or hypomanic episode. Ms. C has not been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, nor has she received any prior psychiatric treatment. She reluctantly discloses that approximately 3 years ago she had a less severe episode of uncontrollable eating and weight gain (20 to 30 lb). At that time, she was able to regain her desired physical appearance by going on the “Subway diet” and undergoing liposuction and plastic surgery.

At her current outpatient clinic visit, Ms. C expresses an interest in exploring bariatric surgery as a potential solution to her weight gain.

[polldaddy:10446186]

Continue to: EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

We refer Ms. C for a physical examination and routine blood analysis to rule out any medical contributors to her condition. Her physical examination is reported as normal, with no signs of skin changes, goiter, or exophthalmos. Ms. C is noted to be obese, with a body mass index of 37.2 kg/m2, and an abdominal circumference of 38.5 in.

A blood analysis shows that Ms. C has elevated triglyceride levels (202 mg/dL) and elevated cholesterol levels (210 mg/dL). Her thyroid function tests are within normal limits based on the dose of levothyroxine she’s been receiving. A pregnancy test is negative.

Ms. C gives the team at the clinic permission to contact her endocrinologist, who reports that he does not suspect that Ms. C’s drastic weight gain and abnormal eating patterns are attributable to her history of thyroid carcinoma because her thyroid function tests have been stable on her current regimen.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. C’s initial presentation, we strongly suspected a diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED). Several differential diagnoses were considered and carefully ruled out; Ms. C’s medical workup did not suggest that her weight gain was due to an active medical condition, and she did not meet DSM-5 criteria for a mood or psychotic disorder or anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

With an estimated lifetime prevalence in the United States of 2.6%, BED is the most prevalent eating disorder (compared with 0.6% for anorexia nervosa and 1% for bulimia nervosa).1 BED is more prevalent in women than in men, and the mean age of onset is mid-20s.

Continue to: BED may be difficult...

BED may be difficult to detect because patients may feel ashamed or guilty and are often hesitant to disclose and discuss their symptoms. Furthermore, they are frequently frustrated by the subjective loss of control over their behaviors. Patients with BED often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics.

Screening for eating disorders

Several screening instruments have been developed to help clinicians identify patients who may need further evaluation for possible diagnosis of an eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and BED.2 The SCOFF questionnaire is composed of 5 brief clinician-administered questions to screen for eating disorders.2 The 7-item Binge Eating Disorder Screener (BED-7) is a screening instrument specific for BED that examines a patient’s eating patterns and behaviors during the past 3 months.3

In general, suspect BED in patients who have significant weight dissatisfaction, fluctuation in weight, and depressive symptoms. The DSM-5 criteria for binge eating disorder are shown in Table 14.

BED and comorbid psychiatric disorders

Patients with BED are more likely than the general population to have comorbid psychiatric disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. Swanson et al5 found that 83.5% of adolescents who met criteria for BED also met criteria for at least 1 other psychiatric disorder, and 37% endorsed >3 concurrent psychiatric conditions. Once BED is confirmed, it is important to screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities that are often present in individuals with BED (Table 21,6).

The rates of diagnosis and treatment of BED remain low. This is likely due to patient factors such as shame and fear of stigma and clinician factors such as lack of awareness, ineffective communication, hesitation to discuss the sensitive topic, or insufficient knowledge about treatment options once BED is diagnosed.

[polldaddy:10446187]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

Ms. C is ambivalent about her BED diagnosis, and becomes angry about it when the proposed treatments do not involve bariatric surgery or cosmetic procedures. Ms. C is enrolled in weekly individual psychotherapy, where she receives a combination of CBT and psychodynamic therapy; however, her attendance is inconsistent. Ms. C is offered a trial of fluoxetine, but adamantly refuses, citing a relative who experienced adverse effects while receiving this type of antidepressant. Ms. C also refuses a trial of topiramate due to concerns of feeling sedated. Finally, she is offered a trial of lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, which was FDA-approved in 2015 to treat moderate to severe BED. We discuss the risks, benefits, and adverse effects of lisdexamfetamine with Ms. C; however, she is hesitant to start this medication and expresses increasing interest in obtaining a consultation for bariatric surgery. Ms. C is provided with extensive education about the risks and dangers of surgery before addressing her eating patterns, and the clinician provides validation, verbal support, and counseling. Ms. C eventually agrees to a trial of lisdexamfetamine, but her insurance denies coverage of this medication.

The authors’ observations

When developing an individualized treatment plan for a patient with BED, the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities should be considered. Treatment goals for patients with BED include:

- abstinence from binge eating

- sustainable weight loss and metabolic health

- reduction in symptoms associated with comorbid conditions

- improvement in self-esteem and overall quality of life.

A 2015 comparative effectiveness review of management and outcomes for patients with BED evaluated pharmacologic, psychologic, behavioral, and combined approaches for treating patients with BED.7 The results suggested that second-generation antidepressants, topiramate, and lisdexamfetamine were superior to placebo in reducing binge-eating episodes and achieving abstinence from binge-eating. Weight reduction was also achieved with topiramate and lisdexamfetamine, and antidepressants helped relieve symptoms of comorbid depression.

Various formats of CBT, including therapist-led and guided self-help, were also superior to placebo in reducing the frequency of binge-eating and promoting abstinence; however, they were generally not effective in treating depression or reducing patients’ weight.7

OUTCOME Fixated on surgery

We appeal the decision of Ms. C’s insurance company; however, during the appeals process, Ms. C becomes increasingly irritable and informs us that she has changed her mind and, with the reported support of her medical doctors, wishes to undergo bariatric surgery. Although we made multiple attempts to engage Ms. C in further treatment, she is lost to follow-up.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Diagnosing and managing patients with binge eating disorder (BED) can be challenging because patients may hesitate to seek help, and/or have psychiatric and medical comorbidities. They often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics. Once BED is confirmed, screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities. A combination of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions can benefit some patients with BED, but treatment should be individualized.

Related Resources

- National Eating Disorders Association. NEDA. www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/.

- Safer D, Telch C, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2017.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Topiramate • Topamax

CASE Uncontrollable eating and weight gain

Ms. C, age 33, presents to an outpatient clinic with complaints of weight gain and “uncontrollable eating.” Ms. C says she’s gained >50 lb over the last year. She describes progressively frequent episodes of overeating during which she feels that she has no control over the amount of food she consumes. She reports eating as often as 10 times a day, and overeating to the point of physical discomfort during most meals. She gives an example of having recently consumed a large pizza, several portions of Chinese food, approximately 20 chicken wings, and half a chocolate cake for dinner. Ms. C admits that on several occasions she has vomited after meals due to feeling extremely full; however, she denies having done so intentionally. She also denies restricting her food intake, misusing laxatives or diuretics, or exercising excessively.

Ms. C expresses frustration and embarrassment with her eating and resulting weight gain. She says she has poor self-esteem, low energy and motivation, and poor concentration. She feels that her condition has significantly impacted her social life, romantic relationships, and family life. She admits she’s been avoiding dating and seeing friends due to her weight gain, and has been irritable with her teenage daughter.

During her initial evaluation, Ms. C is alert and oriented, with a linear and goal-directed thought process. She is somewhat irritable and guarded, wearing large sunglasses that cover most of her face, but is not overtly paranoid. Although she appears frustrated when discussing her condition, she denies feeling hopeless or helpless.

HISTORY Thyroid cancer and mood swings

Ms. C, who is single and unemployed, lives in an apartment with her teenage daughter, with whom she describes having a good relationship. She has been receiving disability benefits for the past 2 years after a motor vehicle accident resulted in multiple fractures of her arm and elbow, and subsequent chronic pain. Ms. C reports a distant history of “problems with alcohol,” but denies drinking any alcohol since being charged with driving under the influence several years ago. She has a 10 pack-year history of smoking and denies any history of illicit drug use.

Two years ago, Ms. C was diagnosed with thyroid carcinoma, and treated with surgical resection and a course of radiation. She has regular visits with her endocrinologist and has been prescribed oral levothyroxine, 150 mcg/d.

Ms. C reports a history of “mood swings” characterized by “snapping at people” and becoming irritable in response to stressful situations, but denies any past symptoms consistent with a manic or hypomanic episode. Ms. C has not been admitted to a psychiatric hospital, nor has she received any prior psychiatric treatment. She reluctantly discloses that approximately 3 years ago she had a less severe episode of uncontrollable eating and weight gain (20 to 30 lb). At that time, she was able to regain her desired physical appearance by going on the “Subway diet” and undergoing liposuction and plastic surgery.

At her current outpatient clinic visit, Ms. C expresses an interest in exploring bariatric surgery as a potential solution to her weight gain.

[polldaddy:10446186]

Continue to: EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

EVALUATION Obese; stable thyroid function

We refer Ms. C for a physical examination and routine blood analysis to rule out any medical contributors to her condition. Her physical examination is reported as normal, with no signs of skin changes, goiter, or exophthalmos. Ms. C is noted to be obese, with a body mass index of 37.2 kg/m2, and an abdominal circumference of 38.5 in.

A blood analysis shows that Ms. C has elevated triglyceride levels (202 mg/dL) and elevated cholesterol levels (210 mg/dL). Her thyroid function tests are within normal limits based on the dose of levothyroxine she’s been receiving. A pregnancy test is negative.

Ms. C gives the team at the clinic permission to contact her endocrinologist, who reports that he does not suspect that Ms. C’s drastic weight gain and abnormal eating patterns are attributable to her history of thyroid carcinoma because her thyroid function tests have been stable on her current regimen.

The authors’ observations

Based on Ms. C’s initial presentation, we strongly suspected a diagnosis of binge eating disorder (BED). Several differential diagnoses were considered and carefully ruled out; Ms. C’s medical workup did not suggest that her weight gain was due to an active medical condition, and she did not meet DSM-5 criteria for a mood or psychotic disorder or anorexia nervosa or bulimia nervosa.

With an estimated lifetime prevalence in the United States of 2.6%, BED is the most prevalent eating disorder (compared with 0.6% for anorexia nervosa and 1% for bulimia nervosa).1 BED is more prevalent in women than in men, and the mean age of onset is mid-20s.

Continue to: BED may be difficult...

BED may be difficult to detect because patients may feel ashamed or guilty and are often hesitant to disclose and discuss their symptoms. Furthermore, they are frequently frustrated by the subjective loss of control over their behaviors. Patients with BED often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics.

Screening for eating disorders

Several screening instruments have been developed to help clinicians identify patients who may need further evaluation for possible diagnosis of an eating disorder, including anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and BED.2 The SCOFF questionnaire is composed of 5 brief clinician-administered questions to screen for eating disorders.2 The 7-item Binge Eating Disorder Screener (BED-7) is a screening instrument specific for BED that examines a patient’s eating patterns and behaviors during the past 3 months.3

In general, suspect BED in patients who have significant weight dissatisfaction, fluctuation in weight, and depressive symptoms. The DSM-5 criteria for binge eating disorder are shown in Table 14.

BED and comorbid psychiatric disorders

Patients with BED are more likely than the general population to have comorbid psychiatric disorders, including mood and anxiety disorders, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, and substance use disorders. Swanson et al5 found that 83.5% of adolescents who met criteria for BED also met criteria for at least 1 other psychiatric disorder, and 37% endorsed >3 concurrent psychiatric conditions. Once BED is confirmed, it is important to screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities that are often present in individuals with BED (Table 21,6).

The rates of diagnosis and treatment of BED remain low. This is likely due to patient factors such as shame and fear of stigma and clinician factors such as lack of awareness, ineffective communication, hesitation to discuss the sensitive topic, or insufficient knowledge about treatment options once BED is diagnosed.

[polldaddy:10446187]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

Ms. C is ambivalent about her BED diagnosis, and becomes angry about it when the proposed treatments do not involve bariatric surgery or cosmetic procedures. Ms. C is enrolled in weekly individual psychotherapy, where she receives a combination of CBT and psychodynamic therapy; however, her attendance is inconsistent. Ms. C is offered a trial of fluoxetine, but adamantly refuses, citing a relative who experienced adverse effects while receiving this type of antidepressant. Ms. C also refuses a trial of topiramate due to concerns of feeling sedated. Finally, she is offered a trial of lisdexamfetamine, 30 mg/d, which was FDA-approved in 2015 to treat moderate to severe BED. We discuss the risks, benefits, and adverse effects of lisdexamfetamine with Ms. C; however, she is hesitant to start this medication and expresses increasing interest in obtaining a consultation for bariatric surgery. Ms. C is provided with extensive education about the risks and dangers of surgery before addressing her eating patterns, and the clinician provides validation, verbal support, and counseling. Ms. C eventually agrees to a trial of lisdexamfetamine, but her insurance denies coverage of this medication.

The authors’ observations

When developing an individualized treatment plan for a patient with BED, the patient’s psychiatric and medical comorbidities should be considered. Treatment goals for patients with BED include:

- abstinence from binge eating

- sustainable weight loss and metabolic health

- reduction in symptoms associated with comorbid conditions

- improvement in self-esteem and overall quality of life.

A 2015 comparative effectiveness review of management and outcomes for patients with BED evaluated pharmacologic, psychologic, behavioral, and combined approaches for treating patients with BED.7 The results suggested that second-generation antidepressants, topiramate, and lisdexamfetamine were superior to placebo in reducing binge-eating episodes and achieving abstinence from binge-eating. Weight reduction was also achieved with topiramate and lisdexamfetamine, and antidepressants helped relieve symptoms of comorbid depression.

Various formats of CBT, including therapist-led and guided self-help, were also superior to placebo in reducing the frequency of binge-eating and promoting abstinence; however, they were generally not effective in treating depression or reducing patients’ weight.7

OUTCOME Fixated on surgery

We appeal the decision of Ms. C’s insurance company; however, during the appeals process, Ms. C becomes increasingly irritable and informs us that she has changed her mind and, with the reported support of her medical doctors, wishes to undergo bariatric surgery. Although we made multiple attempts to engage Ms. C in further treatment, she is lost to follow-up.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Diagnosing and managing patients with binge eating disorder (BED) can be challenging because patients may hesitate to seek help, and/or have psychiatric and medical comorbidities. They often present to medical facilities seeking weight loss solutions rather than to psychiatric clinics. Once BED is confirmed, screen for other psychiatric and medical comorbidities. A combination of pharmacologic and psychotherapeutic interventions can benefit some patients with BED, but treatment should be individualized.

Related Resources

- National Eating Disorders Association. NEDA. www.nationaleatingdisorders.org/.

- Safer D, Telch C, Chen EY. Dialectical behavior therapy for binge eating and bulimia. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2017.

Drug Brand Names

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisdexamfetamine • Vyvanse

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358.

2. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1467-1468.

3. Herman BK, Deal LS, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Development of the 7-Item Binge-Eating Disorder screener (BEDS-7). Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(2):10.4088/PCC.15m01896. doi:10.4088/PCC.15m01896.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714.

6. Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Casuto LS, et al. Binge eating disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2017;40(2):255-266.

7. Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, et al. Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338312/. Published December 2015. Accessed July 29, 2019.

1. Hudson JI, Hiripi E, Pope HG Jr, et al. The prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61(3):348-358.

2. Morgan JF, Reid F, Lacey JH. The SCOFF questionnaire: assessment of a new screening tool for eating disorders. BMJ. 1999;319(7223):1467-1468.

3. Herman BK, Deal LS, DiBenedetti DB, et al. Development of the 7-Item Binge-Eating Disorder screener (BEDS-7). Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(2):10.4088/PCC.15m01896. doi:10.4088/PCC.15m01896.

4. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

5. Swanson SA, Crow SJ, Le Grange D, et al. Prevalence and correlates of eating disorders in adolescents. Results from the national comorbidity survey replication adolescent supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(7):714.

6. Guerdjikova AI, Mori N, Casuto LS, et al. Binge eating disorder. Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2017;40(2):255-266.

7. Berkman ND, Brownley KA, Peat CM, et al. Management and outcomes of binge-eating disorder. Comparative Effectiveness Reviews, No. 160. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US). https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK338312/. Published December 2015. Accessed July 29, 2019.

Effects of psychotropic medications on thyroid function

Ms. L, age 53, presents to an inpatient psychiatric unit with depression, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, cognitive blunting, loss of appetite, increased alcohol intake, and recent suicidal ideation. Her symptoms began 3 months ago and gradually worsened. Her medical and psychiatric history is significant for hypertension, fibromyalgia, and chronic pain (back and neck), major depressive disorder (MDD; recurrent, severe), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Ms. L’s current medication regimen includes lisinopril, 40 mg daily; fluoxetine, 60 mg daily; mirtazapine, 30 mg at bedtime; gabapentin, 300 mg twice daily; alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily as needed for anxiety; and oral docusate, 100 mg twice daily as needed. Her blood pressure is 124/85 mm Hg, heart rate is 66 beats per minute, and an electrocardiogram is normal. Laboratory workup reveals a potassium level of 4.4 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen level of 20 mg/dL, serum creatinine level of 0.8 mg/dL, estimated creatinine clearance of 89.6 mL/min, free triiodothyronine (T3) levels of 2.7 pg/mL, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 7.68 mIU/L, free thyroxine (T4) level of 1.3 ng/dL, and blood ethanol level <10 mg/dL. In addition to the symptoms Ms. L initially described, a review of systems reveals word-finding difficulty, cold intolerance, constipation, hair loss, brittle nails, and dry skin.

To target Ms. L’s MDD, GAD, fibromyalgia, and chronic pain, fluoxetine, 60 mg daily is cross titrated beginning on Day 1 to duloxetine, 60 mg twice daily, over 4 days. Mirtazapine is decreased on Day 3 to 7.5 mg at bedtime to target Ms. L’s sleep and appetite. Due to the presence of several symptoms associated with hypothyroidism and a slightly elevated TSH level, on Day 6 we initiate adjunctive levothyroxine, 50 mcg daily each morning to target symptomatic subclinical hypothyroidism, and to potentially augment the other medications prescribed to address Ms. L’s MDD.

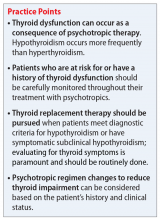

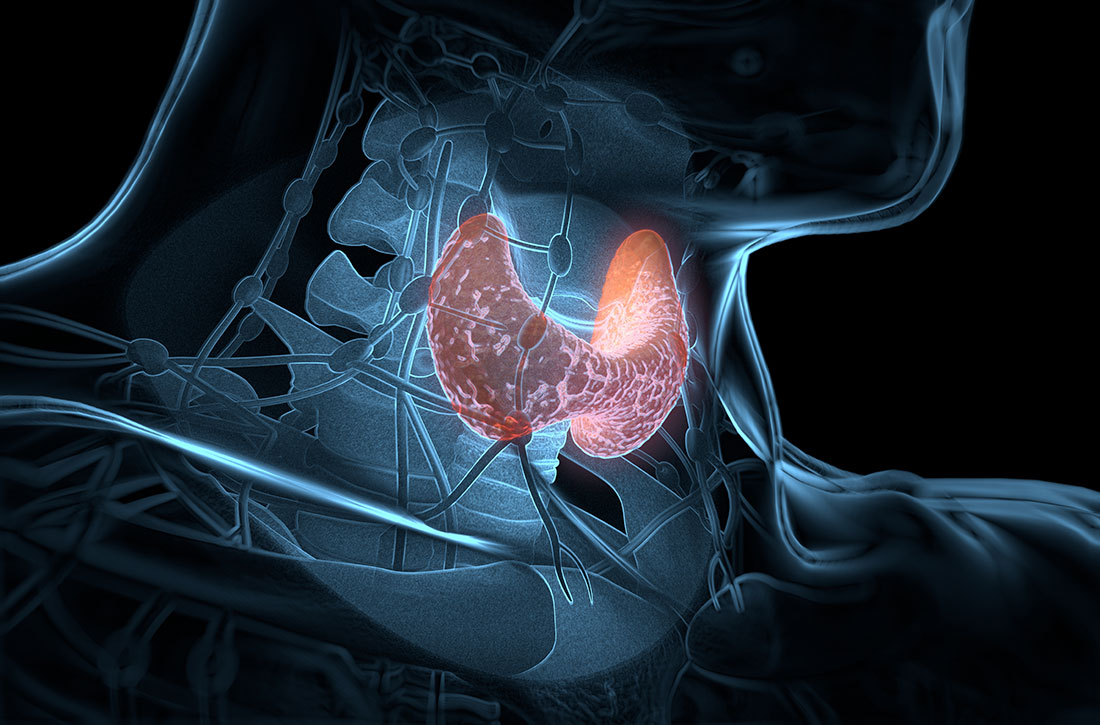

Thyroid hormone function is a complex physiological process controlled through the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis. Psychotropic medications can impact thyroid hormone function and contribute to aberrations in thyroid physiology.1 Because patients with mental illness may require multiple psychotropic medications, it is imperative to understand the potential effects of these agents.

Antidepressants can induce hypothyroidism along multiple points of hormonal synthesis and iodine utilization. Tricyclic antidepressants have been implicated in the development of drug-iodide complexes, thus reducing biologically active iodine.2 Tricyclic antidepressants also can bind thyroid peroxidase, an enzyme necessary in the production of T4 and T3, altering hormonal production, resulting in a hypothyroid state.1 Non-tricyclic antidepressants (ie, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] and non-SSRIs [including serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and mirtazapine]) have also been implicated in thyroid dysfunction. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have the propensity to induce hypothyroidism through inhibition of thyroid hormones T4 and T3.1,3 This inhibition is not always seen with concurrent reductions in TSH levels. Conversely, non-SSRIs can influence thyroid hormone levels with great variation, leading to thyroid hormone levels that are increased, decreased, or unchanged.1 Patients with a history of thyroid dysfunction should receive close thyroid function monitoring, especially while taking antidepressants.

Antipsychotics have a proclivity to induce hypothyroidism by means similar to antidepressants via hormonal manipulation and immunogenicity. Phenothiazines impact thyroid function through hormonal activation and degradation, and induction of autoimmunity.1 Autoimmunity may develop by means of antibody production or antigen immunization through the major histocompatibility complex.2 Other first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) (eg, haloperidol and loxapine) are known to antagonize dopamine receptors in the tuberoinfundibular pathway, resulting in increased prolactin levels. Hyperprolactinemia may result in increased TSH levels through HPT axis activation.1 Additionally, FGAs can induce an immunogenic effect through production of antithyroid antibodies.1 Similar to FGAs, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) can increase TSH levels through hyperprolactinemia. Further research focused on SGAs is needed to determine how profound this effect may be.

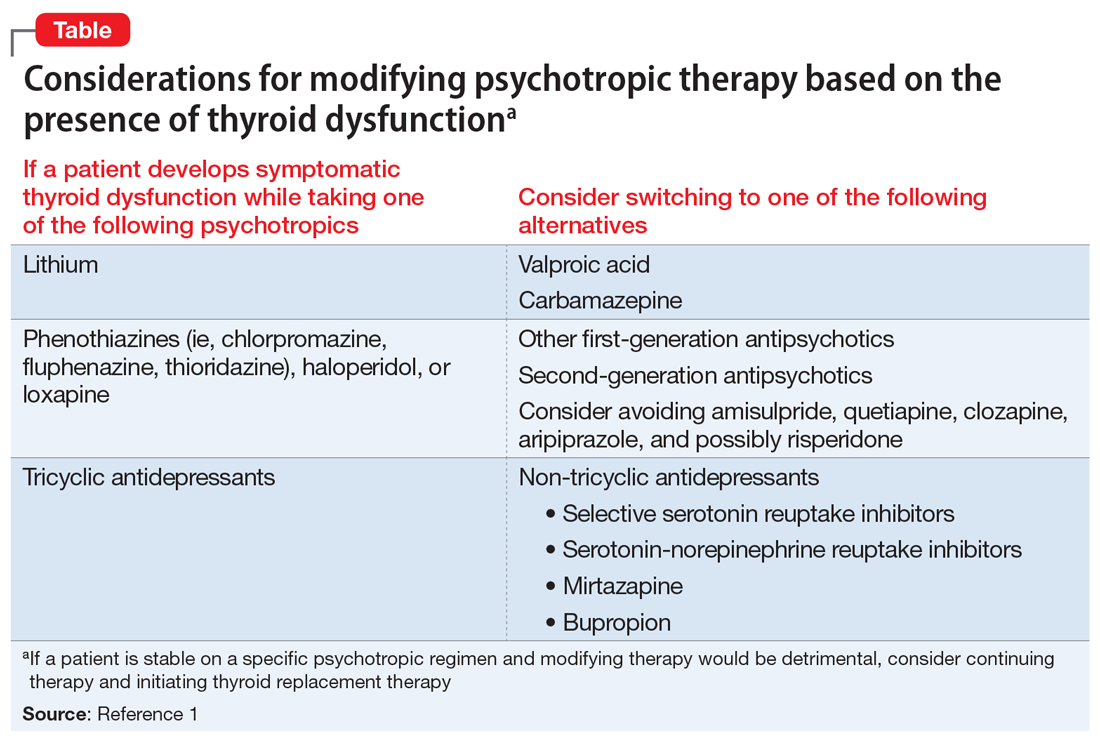

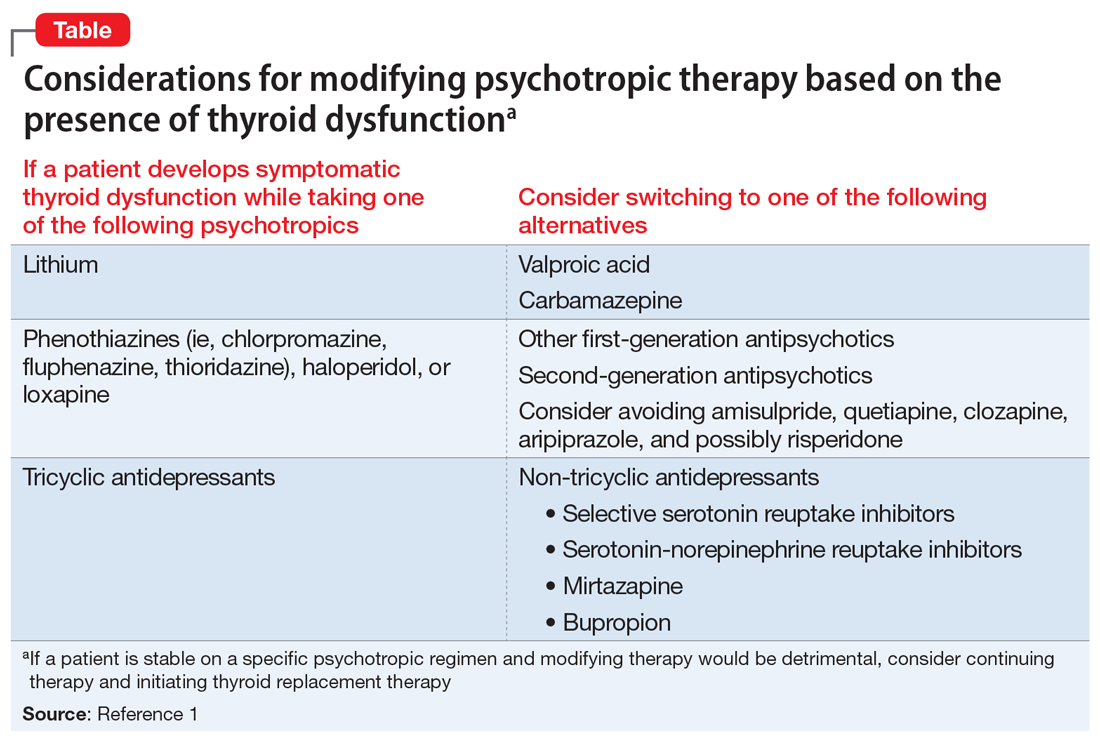

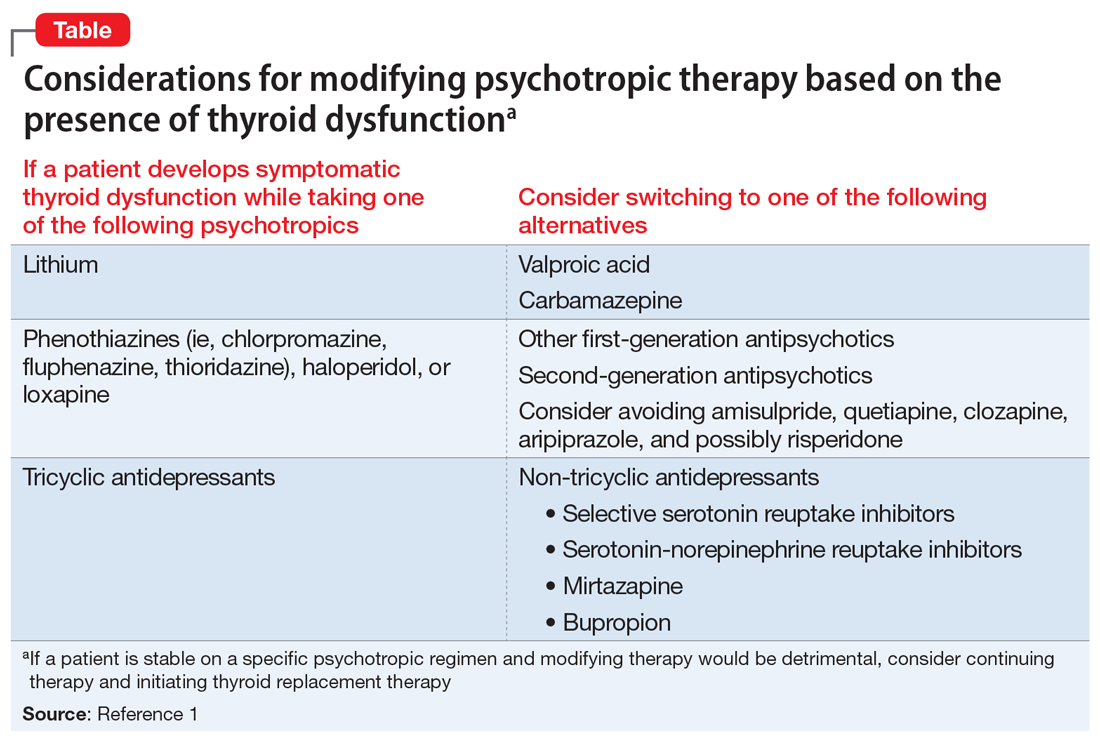

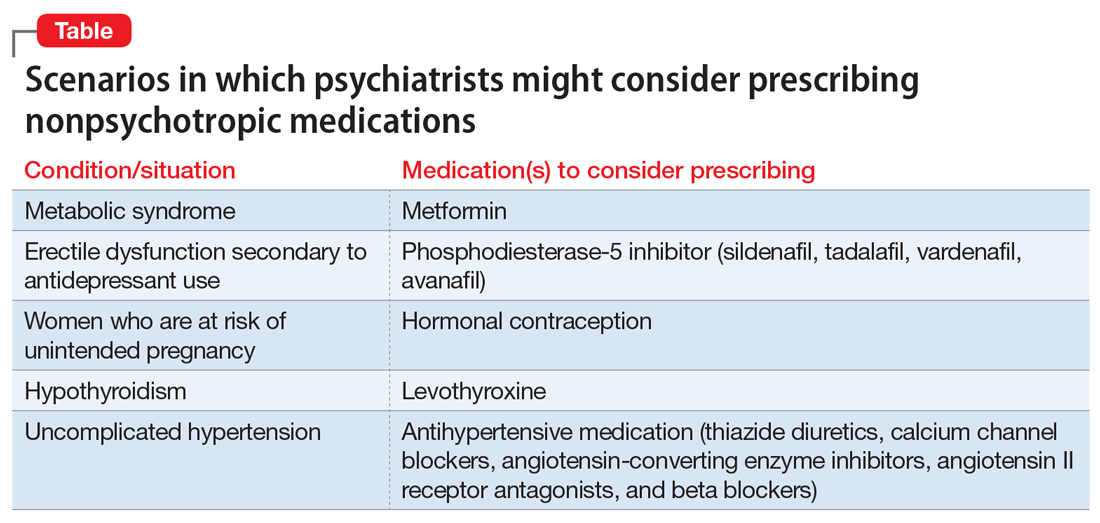

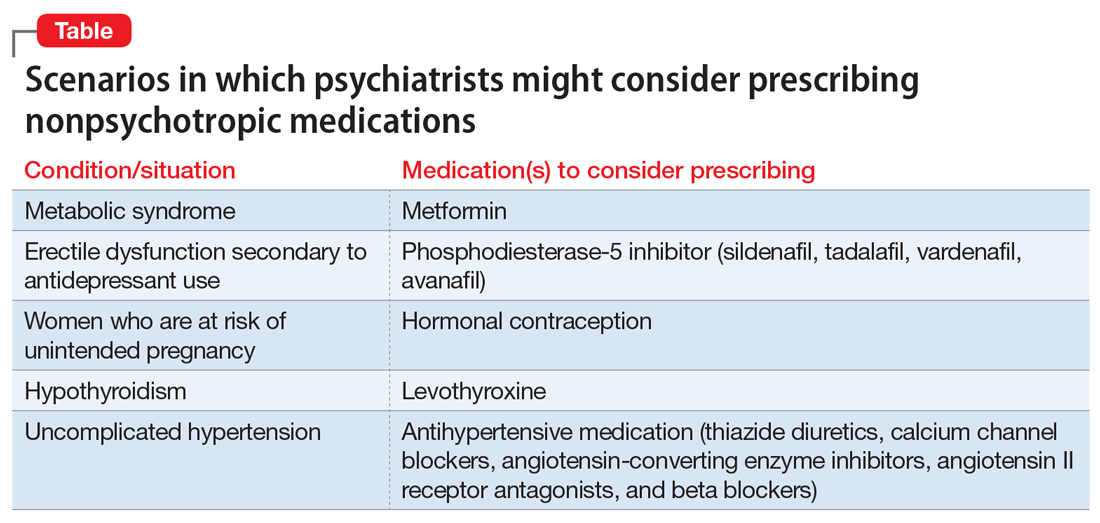

The Table1 outlines considerations for modifying psychotropic therapy based on the presence of concurrent thyroid dysfunction. Thyroid function should be routinely assessed in patients treated with antipsychotics.

Mood stabilizers are capable of altering thyroid function and inducing a hypothyroid state. Lithium has been implicated in both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism due to its inhibition of hormonal secretion, and toxicity to thyroid cells with chronic use, respectively.1,4 Hypothyroidism can develop shortly after initiating lithium; women tend to have a greater predilection for thyroid dysfunction than men.1 Carbamazepine (CBZ) can reduce thyroid hormone levels without having a direct effect on TSH or thyroid dysfunction.1 As with lithium, women tend to be more susceptible to this effect. Valproic acid (VPA) has been shown to either increase, decrease, or have no impact on thyroid hormone levels, with little effect on TSH.1 When VPA is given in combination with CBZ, significant reductions in thyroid levels with a concurrent increase in TSH can occur.1 In patients with preexisting thyroid dysfunction, the combination of VPA and CBZ should be used with caution.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

By Day 8, Ms. L reports less fatigue, clearer thinking, improved concentration, and less pain. She also no longer reports suicidal ideation, and demonstrates improved appetite and mood. She is discharged on Day 9 of her hospitalization.

The treatment team refers Ms. L for outpatient follow-up in 4 weeks, with a goal TSH level <3.0. Unfortunately, the effects of levothyroxine on Ms. L’s TSH level could not be determined during her hospital stay, and she has not returned to the facility since the initial presentation.

Thyroid function and mood

Ms. L’s case illustrates how thyroid function, pain, cognition, and mood may be interconnected. It is important to address all potential underlying comorbidities and establish appropriate outpatient care and follow-up so that patients may experience a more robust recovery. Further, this case highlights the importance of ruling out other potential medical causes of MDD during the initial diagnosis, and during times of recurrence or relapse, especially when a recent stressor, medication changes, or medication nonadherence cannot be identified as potential contributors.

Related Resources

- Cojić M, Cvejanov-Kezunović L. Subclinical hypothyroidism – whether and when to start treatment? Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(7):1042-1046.

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2012;22(12):1200-1235.

- Iosifescu DV. ‘Supercharge’ antidepressants by adding thyroid hormones. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(7):15-20,25.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clozapine • Clozaril

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Loxitane

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Valproic acid • Depakote

1. Bou Khalil R, Richa S. Thyroid adverse effect of psychotropic drugs: a review. Clin Neuropharm. 2001;34(6):248-255.

2. Sauvage MF, Marquet P, Rousseau A, et al. Relationship between psychotropic drugs and thyroid function: a review. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;149(2):127-135.

3. Shelton RC, Winn S, Ekhatore N, et al. The effects of antidepressants on the thyroid axis in depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1993;33(2):120-126.

4. Kundra P, Burman KD. The effect of medications on thyroid function tests. Med Clin North Am. 2012;96(2):283-295.

Ms. L, age 53, presents to an inpatient psychiatric unit with depression, difficulty concentrating, fatigue, cognitive blunting, loss of appetite, increased alcohol intake, and recent suicidal ideation. Her symptoms began 3 months ago and gradually worsened. Her medical and psychiatric history is significant for hypertension, fibromyalgia, and chronic pain (back and neck), major depressive disorder (MDD; recurrent, severe), and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD). Ms. L’s current medication regimen includes lisinopril, 40 mg daily; fluoxetine, 60 mg daily; mirtazapine, 30 mg at bedtime; gabapentin, 300 mg twice daily; alprazolam, 0.5 mg twice daily as needed for anxiety; and oral docusate, 100 mg twice daily as needed. Her blood pressure is 124/85 mm Hg, heart rate is 66 beats per minute, and an electrocardiogram is normal. Laboratory workup reveals a potassium level of 4.4 mEq/L, blood urea nitrogen level of 20 mg/dL, serum creatinine level of 0.8 mg/dL, estimated creatinine clearance of 89.6 mL/min, free triiodothyronine (T3) levels of 2.7 pg/mL, thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) level of 7.68 mIU/L, free thyroxine (T4) level of 1.3 ng/dL, and blood ethanol level <10 mg/dL. In addition to the symptoms Ms. L initially described, a review of systems reveals word-finding difficulty, cold intolerance, constipation, hair loss, brittle nails, and dry skin.

To target Ms. L’s MDD, GAD, fibromyalgia, and chronic pain, fluoxetine, 60 mg daily is cross titrated beginning on Day 1 to duloxetine, 60 mg twice daily, over 4 days. Mirtazapine is decreased on Day 3 to 7.5 mg at bedtime to target Ms. L’s sleep and appetite. Due to the presence of several symptoms associated with hypothyroidism and a slightly elevated TSH level, on Day 6 we initiate adjunctive levothyroxine, 50 mcg daily each morning to target symptomatic subclinical hypothyroidism, and to potentially augment the other medications prescribed to address Ms. L’s MDD.

Thyroid hormone function is a complex physiological process controlled through the hypothalamic-pituitary-thyroid (HPT) axis. Psychotropic medications can impact thyroid hormone function and contribute to aberrations in thyroid physiology.1 Because patients with mental illness may require multiple psychotropic medications, it is imperative to understand the potential effects of these agents.

Antidepressants can induce hypothyroidism along multiple points of hormonal synthesis and iodine utilization. Tricyclic antidepressants have been implicated in the development of drug-iodide complexes, thus reducing biologically active iodine.2 Tricyclic antidepressants also can bind thyroid peroxidase, an enzyme necessary in the production of T4 and T3, altering hormonal production, resulting in a hypothyroid state.1 Non-tricyclic antidepressants (ie, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRIs] and non-SSRIs [including serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors and mirtazapine]) have also been implicated in thyroid dysfunction. Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have the propensity to induce hypothyroidism through inhibition of thyroid hormones T4 and T3.1,3 This inhibition is not always seen with concurrent reductions in TSH levels. Conversely, non-SSRIs can influence thyroid hormone levels with great variation, leading to thyroid hormone levels that are increased, decreased, or unchanged.1 Patients with a history of thyroid dysfunction should receive close thyroid function monitoring, especially while taking antidepressants.

Antipsychotics have a proclivity to induce hypothyroidism by means similar to antidepressants via hormonal manipulation and immunogenicity. Phenothiazines impact thyroid function through hormonal activation and degradation, and induction of autoimmunity.1 Autoimmunity may develop by means of antibody production or antigen immunization through the major histocompatibility complex.2 Other first-generation antipsychotics (FGAs) (eg, haloperidol and loxapine) are known to antagonize dopamine receptors in the tuberoinfundibular pathway, resulting in increased prolactin levels. Hyperprolactinemia may result in increased TSH levels through HPT axis activation.1 Additionally, FGAs can induce an immunogenic effect through production of antithyroid antibodies.1 Similar to FGAs, second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) can increase TSH levels through hyperprolactinemia. Further research focused on SGAs is needed to determine how profound this effect may be.

The Table1 outlines considerations for modifying psychotropic therapy based on the presence of concurrent thyroid dysfunction. Thyroid function should be routinely assessed in patients treated with antipsychotics.

Mood stabilizers are capable of altering thyroid function and inducing a hypothyroid state. Lithium has been implicated in both hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism due to its inhibition of hormonal secretion, and toxicity to thyroid cells with chronic use, respectively.1,4 Hypothyroidism can develop shortly after initiating lithium; women tend to have a greater predilection for thyroid dysfunction than men.1 Carbamazepine (CBZ) can reduce thyroid hormone levels without having a direct effect on TSH or thyroid dysfunction.1 As with lithium, women tend to be more susceptible to this effect. Valproic acid (VPA) has been shown to either increase, decrease, or have no impact on thyroid hormone levels, with little effect on TSH.1 When VPA is given in combination with CBZ, significant reductions in thyroid levels with a concurrent increase in TSH can occur.1 In patients with preexisting thyroid dysfunction, the combination of VPA and CBZ should be used with caution.

Continue to: CASE

CASE CONTINUED

By Day 8, Ms. L reports less fatigue, clearer thinking, improved concentration, and less pain. She also no longer reports suicidal ideation, and demonstrates improved appetite and mood. She is discharged on Day 9 of her hospitalization.

The treatment team refers Ms. L for outpatient follow-up in 4 weeks, with a goal TSH level <3.0. Unfortunately, the effects of levothyroxine on Ms. L’s TSH level could not be determined during her hospital stay, and she has not returned to the facility since the initial presentation.

Thyroid function and mood

Ms. L’s case illustrates how thyroid function, pain, cognition, and mood may be interconnected. It is important to address all potential underlying comorbidities and establish appropriate outpatient care and follow-up so that patients may experience a more robust recovery. Further, this case highlights the importance of ruling out other potential medical causes of MDD during the initial diagnosis, and during times of recurrence or relapse, especially when a recent stressor, medication changes, or medication nonadherence cannot be identified as potential contributors.

Related Resources

- Cojić M, Cvejanov-Kezunović L. Subclinical hypothyroidism – whether and when to start treatment? Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2017;5(7):1042-1046.

- Garber JR, Cobin RH, Gharib H, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for hypothyroidism in adults: cosponsored by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and the American Thyroid Association. Thyroid. 2012;22(12):1200-1235.

- Iosifescu DV. ‘Supercharge’ antidepressants by adding thyroid hormones. Current Psychiatry. 2006;5(7):15-20,25.

Drug Brand Names

Alprazolam • Xanax

Aripiprazole • Abilify

Bupropion • Wellbutrin

Carbamazepine • Carbatrol, Tegretol

Chlorpromazine • Thorazine

Clozapine • Clozaril

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluphenazine • Prolixin

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Haloperidol • Haldol

Levothyroxine • Synthroid

Lisinopril • Prinivil, Zestril

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Loxapine • Loxitane

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Quetiapine • Seroquel

Risperidone • Risperdal

Thioridazine • Mellaril

Valproic acid • Depakote