User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Antipsychotics ineffective for symptoms of delirium in palliative care

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

CLINICAL QUESTION: Do antipsychotics provide symptomatic benefit for delirium in palliative care?

BACKGROUND: Antipsychotics are frequently used for the treatment of delirium and guideline recommended for delirium-associated distress. However, a 2016 meta-analysis found antipsychotics are not associated with change in delirium duration or severity. Antipsychotics for palliative management of delirium at end of life is not well studied.

STUDY DESIGN: Double-blind randomized controlled trial with placebo, haloperidol, and risperidone arms.

SETTING: Eleven Australian inpatient hospice or palliative care services.

SYNOPSIS: 247 patients (mean age, 74.9 years; 88.3% with cancer) with advanced incurable disease and active delirium were studied. Most had mild-moderate severity delirium. All received nonpharmacological measures and plan to address reversible precipitants. Patients were randomized to placebo (84), haloperidol (81), or risperidone (82) for 72 hours. Dose titration was allowed based on delirium symptoms. In intention to treat analysis the delirium severity scores were statistically higher in haloperidol and risperidone arms, compared with placebo. This reached statistical significance although less than the minimum clinically significant difference. Mortality, use of rescue medicines, and extrapyramidal symptoms were higher in antipsychotic groups.

BOTTOM LINE: Antipsychotics cause side effects without efficacy in palliation of symptoms of delirium.

CITATIONS: Agar MR, Lawlor PG, Quinn S, et al. Efficacy of oral risperidone, haloperidol, or placebo for symptoms of delirium among patients in palliative care: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2017 Jan;177:34-42.

Dr. Cumbler is the associate chief of hospital medicine, Division of Hospital Medicine, University of Colorado School of Medicine, Aurora.

A little rivaroxaban goes a long way

In patients with venous thromboembolism at equipoise for further anticoagulation therapy, treatment with a 10-mg dose of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) had comparable efficacy to a 20-mg dose, with both leading to fewer recurrences than treatment with aspirin. There were no statistically significant differences in clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding between the three groups.

The study’s conclusions are limited to relatively healthy patients such as the ones who were selected for the study.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med 2017 March 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700518).

Anticoagulants are the primary treatment for prevention of venous thromboembolism recurrences, but the medications are often stopped after 6-12 months because of concerns about bleeding. To counter that issue, physicians may prescribe lower doses of anticoagulants such as rivaroxaban, or substitute aspirin.

The work follows another recent study of apixaban (Eliquis), which showed that a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose performed the same as did a 5.0-mg twice-daily dose in the prevention of venous thromboembolism recurrence (N Engl J Med. 2013;368[8]:699-708).

“I think the story is kind of the same here,” said David Garcia, MD, professor of hematology at the University of Washington, Seattle, who was one of the principal investigators in the trial.

Patients with unprompted venous thromboembolism are increasingly being offered anticoagulant therapy to prevent recurrences. Those drugs have inherent bleeding risks, but the newer drugs and even warfarin are becoming safer. Even so, “as we embark on that, one has to remember that the risk of anticoagulants is cumulative. It may only carry a risk of 1% per year of major hemorrhage, but if the patient has to take it for 10 or 20 or 30 years, it’s a nontrivial risk of major bleeding over that time,” said Dr. Garcia.

The researchers conducted the Reduced-Dose Rivaroxaban in the Long-Term Prevention of Recurrent Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism (EINSTEIN CHOICE) trial, in which 3,365 patients from 24 sites were randomized to receive 20 mg rivaroxaban, 10 mg rivaroxaban, or 100 mg aspirin for up to 1 year following an initial 6-12 months of treatment with anticoagulation therapy.

During a median follow-up of 1 year, 4.4% of patients on aspirin experienced a recurrence, compared with 1.5% of patients in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group (hazard ratio versus aspirin, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.59; P less than .001), and 1.2% in the 10-mg rivaroxaban group (HR versus aspirin, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.14-0.47; P less than .001). There was no statistical significance between the two doses of rivaroxaban.

The rates of fatal thromboembolism were similar, at 0.2% in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group, 0% in the 10-mg group, and 0.2% in the aspirin group.

Major bleeding occurred in 0.5% of patients in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group, in 0.4% of the 10-mg rivaroxaban group, and 0.3% in the aspirin group. Nonmajor, clinically relevant bleeding was also similar between groups, at 2.7% in the 20-mg group, 2.0% in the 10-mg group, and 1.8% in the aspirin group. These differences were not statistically significant.

The study is good news for clinicians as they help patients decide whether to undergo preventive therapy. “Even before the newer agents arrived on the market, we had moved the needle a lot in terms of maximizing the safety of warfarin. I think these drugs take it to yet another level,” said Dr. Garcia.

Bayer Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Garcia has received honoraria from Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

“Given the protection from recurrent venous thromboembolism afforded by reduced-dose rivaroxaban, extending treatment beyond 3 months could be considered in patients with provoked venous thromboembolism who are at average risk for bleeding and who are strongly averse to having another episode of venous thromboembolism. In light of the safety profile of low-dose rivaroxaban, the benefit of this strategy does not need to be large in order to justify the extension of therapy.

“This trial suggests that it would be helpful to evaluate the effects of reduced doses of rivaroxaban within 6 months after an episode of venous thromboembolism.

“For patients without cancer, the use of direct oral anticoagulant agents might be considered as first-line treatment for those with acute venous thromboembolism. Full-dose treatment could be continued for a minimum of 3-6 months. In patients in whom there is equipoise with respect to continuing anticoagulant therapy beyond this period, the use of a reduced-intensity direct oral anticoagulant agent might be considered. Clinicians who choose this strategy can be confident of excellent efficacy and low bleeding risk similar to that observed with aspirin or placebo” (N Engl J Med 2017 March 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1701628).

Mark Crowther, MD, is professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. Adam Cuker is assistant professor of medicine at the hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Given the protection from recurrent venous thromboembolism afforded by reduced-dose rivaroxaban, extending treatment beyond 3 months could be considered in patients with provoked venous thromboembolism who are at average risk for bleeding and who are strongly averse to having another episode of venous thromboembolism. In light of the safety profile of low-dose rivaroxaban, the benefit of this strategy does not need to be large in order to justify the extension of therapy.

“This trial suggests that it would be helpful to evaluate the effects of reduced doses of rivaroxaban within 6 months after an episode of venous thromboembolism.

“For patients without cancer, the use of direct oral anticoagulant agents might be considered as first-line treatment for those with acute venous thromboembolism. Full-dose treatment could be continued for a minimum of 3-6 months. In patients in whom there is equipoise with respect to continuing anticoagulant therapy beyond this period, the use of a reduced-intensity direct oral anticoagulant agent might be considered. Clinicians who choose this strategy can be confident of excellent efficacy and low bleeding risk similar to that observed with aspirin or placebo” (N Engl J Med 2017 March 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1701628).

Mark Crowther, MD, is professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. Adam Cuker is assistant professor of medicine at the hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

“Given the protection from recurrent venous thromboembolism afforded by reduced-dose rivaroxaban, extending treatment beyond 3 months could be considered in patients with provoked venous thromboembolism who are at average risk for bleeding and who are strongly averse to having another episode of venous thromboembolism. In light of the safety profile of low-dose rivaroxaban, the benefit of this strategy does not need to be large in order to justify the extension of therapy.

“This trial suggests that it would be helpful to evaluate the effects of reduced doses of rivaroxaban within 6 months after an episode of venous thromboembolism.

“For patients without cancer, the use of direct oral anticoagulant agents might be considered as first-line treatment for those with acute venous thromboembolism. Full-dose treatment could be continued for a minimum of 3-6 months. In patients in whom there is equipoise with respect to continuing anticoagulant therapy beyond this period, the use of a reduced-intensity direct oral anticoagulant agent might be considered. Clinicians who choose this strategy can be confident of excellent efficacy and low bleeding risk similar to that observed with aspirin or placebo” (N Engl J Med 2017 March 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1701628).

Mark Crowther, MD, is professor of medicine at McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont. Adam Cuker is assistant professor of medicine at the hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

In patients with venous thromboembolism at equipoise for further anticoagulation therapy, treatment with a 10-mg dose of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) had comparable efficacy to a 20-mg dose, with both leading to fewer recurrences than treatment with aspirin. There were no statistically significant differences in clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding between the three groups.

The study’s conclusions are limited to relatively healthy patients such as the ones who were selected for the study.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med 2017 March 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700518).

Anticoagulants are the primary treatment for prevention of venous thromboembolism recurrences, but the medications are often stopped after 6-12 months because of concerns about bleeding. To counter that issue, physicians may prescribe lower doses of anticoagulants such as rivaroxaban, or substitute aspirin.

The work follows another recent study of apixaban (Eliquis), which showed that a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose performed the same as did a 5.0-mg twice-daily dose in the prevention of venous thromboembolism recurrence (N Engl J Med. 2013;368[8]:699-708).

“I think the story is kind of the same here,” said David Garcia, MD, professor of hematology at the University of Washington, Seattle, who was one of the principal investigators in the trial.

Patients with unprompted venous thromboembolism are increasingly being offered anticoagulant therapy to prevent recurrences. Those drugs have inherent bleeding risks, but the newer drugs and even warfarin are becoming safer. Even so, “as we embark on that, one has to remember that the risk of anticoagulants is cumulative. It may only carry a risk of 1% per year of major hemorrhage, but if the patient has to take it for 10 or 20 or 30 years, it’s a nontrivial risk of major bleeding over that time,” said Dr. Garcia.

The researchers conducted the Reduced-Dose Rivaroxaban in the Long-Term Prevention of Recurrent Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism (EINSTEIN CHOICE) trial, in which 3,365 patients from 24 sites were randomized to receive 20 mg rivaroxaban, 10 mg rivaroxaban, or 100 mg aspirin for up to 1 year following an initial 6-12 months of treatment with anticoagulation therapy.

During a median follow-up of 1 year, 4.4% of patients on aspirin experienced a recurrence, compared with 1.5% of patients in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group (hazard ratio versus aspirin, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.59; P less than .001), and 1.2% in the 10-mg rivaroxaban group (HR versus aspirin, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.14-0.47; P less than .001). There was no statistical significance between the two doses of rivaroxaban.

The rates of fatal thromboembolism were similar, at 0.2% in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group, 0% in the 10-mg group, and 0.2% in the aspirin group.

Major bleeding occurred in 0.5% of patients in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group, in 0.4% of the 10-mg rivaroxaban group, and 0.3% in the aspirin group. Nonmajor, clinically relevant bleeding was also similar between groups, at 2.7% in the 20-mg group, 2.0% in the 10-mg group, and 1.8% in the aspirin group. These differences were not statistically significant.

The study is good news for clinicians as they help patients decide whether to undergo preventive therapy. “Even before the newer agents arrived on the market, we had moved the needle a lot in terms of maximizing the safety of warfarin. I think these drugs take it to yet another level,” said Dr. Garcia.

Bayer Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Garcia has received honoraria from Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

In patients with venous thromboembolism at equipoise for further anticoagulation therapy, treatment with a 10-mg dose of rivaroxaban (Xarelto) had comparable efficacy to a 20-mg dose, with both leading to fewer recurrences than treatment with aspirin. There were no statistically significant differences in clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding between the three groups.

The study’s conclusions are limited to relatively healthy patients such as the ones who were selected for the study.

The findings were presented at the annual meeting of the American College of Cardiology and published simultaneously in the New England Journal of Medicine (N Engl J Med 2017 March 18. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1700518).

Anticoagulants are the primary treatment for prevention of venous thromboembolism recurrences, but the medications are often stopped after 6-12 months because of concerns about bleeding. To counter that issue, physicians may prescribe lower doses of anticoagulants such as rivaroxaban, or substitute aspirin.

The work follows another recent study of apixaban (Eliquis), which showed that a 2.5-mg twice-daily dose performed the same as did a 5.0-mg twice-daily dose in the prevention of venous thromboembolism recurrence (N Engl J Med. 2013;368[8]:699-708).

“I think the story is kind of the same here,” said David Garcia, MD, professor of hematology at the University of Washington, Seattle, who was one of the principal investigators in the trial.

Patients with unprompted venous thromboembolism are increasingly being offered anticoagulant therapy to prevent recurrences. Those drugs have inherent bleeding risks, but the newer drugs and even warfarin are becoming safer. Even so, “as we embark on that, one has to remember that the risk of anticoagulants is cumulative. It may only carry a risk of 1% per year of major hemorrhage, but if the patient has to take it for 10 or 20 or 30 years, it’s a nontrivial risk of major bleeding over that time,” said Dr. Garcia.

The researchers conducted the Reduced-Dose Rivaroxaban in the Long-Term Prevention of Recurrent Symptomatic Venous Thromboembolism (EINSTEIN CHOICE) trial, in which 3,365 patients from 24 sites were randomized to receive 20 mg rivaroxaban, 10 mg rivaroxaban, or 100 mg aspirin for up to 1 year following an initial 6-12 months of treatment with anticoagulation therapy.

During a median follow-up of 1 year, 4.4% of patients on aspirin experienced a recurrence, compared with 1.5% of patients in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group (hazard ratio versus aspirin, 0.34; 95% confidence interval, 0.20-0.59; P less than .001), and 1.2% in the 10-mg rivaroxaban group (HR versus aspirin, 0.26; 95% CI, 0.14-0.47; P less than .001). There was no statistical significance between the two doses of rivaroxaban.

The rates of fatal thromboembolism were similar, at 0.2% in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group, 0% in the 10-mg group, and 0.2% in the aspirin group.

Major bleeding occurred in 0.5% of patients in the 20-mg rivaroxaban group, in 0.4% of the 10-mg rivaroxaban group, and 0.3% in the aspirin group. Nonmajor, clinically relevant bleeding was also similar between groups, at 2.7% in the 20-mg group, 2.0% in the 10-mg group, and 1.8% in the aspirin group. These differences were not statistically significant.

The study is good news for clinicians as they help patients decide whether to undergo preventive therapy. “Even before the newer agents arrived on the market, we had moved the needle a lot in terms of maximizing the safety of warfarin. I think these drugs take it to yet another level,” said Dr. Garcia.

Bayer Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Garcia has received honoraria from Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

FROM ACC 17

Key clinical point: In venous thromboembolism prevention, a 10-mg dose matched 20 mg.

Major finding: The recurrence rates were 1.2% at 10 mg versus 4.4% with aspirin.

Data source: Randomized comparison trial of 3,365 patients.

Disclosures: Bayer Pharmaceuticals funded the study. Dr. Garcia has received honoraria from Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Pfizer, and Boehringer Ingelheim.

What are indications, complications of acute blood transfusions in sickle cell anemia? Key Points Additional Reading

Case

A 19-year-old female with a history of sickle cell anemia and hemoglobin SS, presents with a 2-day history of worsening lower back pain and dyspnea. Physical exam reveals oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, a temperature of 39.2° C, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, and right-sided rales. Her hemoglobin is 5.3 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin of 7.8 g/dL). Chest radiograph reveals a right upper lobe pneumonia, and she is diagnosed with acute chest syndrome.

What are indications and complications of acute transfusion in sickle cell anemia?

Background

Chronic hemolytic anemia is a trademark of sickle cell anemia (SCA) or hemoglobin (Hb) SS as is acute anemia during illness or vaso-occlusive crises. Blood transfusions were the first therapy used in sickle cell disease, long before the pathophysiology was understood. Transfusion of red blood cells (RBC) increases the percentage of circulating normal Hb A, thereby decreasing the percentage of abnormal, sickled cells. This increases the oxygen-carrying capacity of the patient’s RBCs, improves organ perfusion, prevents organ damage, and can be life saving. SCA patients are the largest users of the United States rare donor blood bank registry.1

Unfortunately, transfusion comes with many risks including infection, transfusion reactions, alloimmunization, iron overload, hyperviscosity, and volume overload.

As SCA is a low-prevalence disease in a minority population, very few studies have been performed. Currently, the guidance available regarding blood transfusion is primarily based on expert opinion.

What to transfuse

Leukoreduced and intensive phenotypically matched RBC are not possible in many medical centers. Previous studies have noted decreased incidence of febrile nonhemolytic anemia transfusion reactions, cytomegalovirus transmission, and human leukocyte antigen alloimmunization in leukoreduced blood transfusions, however, these studies did not include SCA patients.2

Complications from transfusion

Complications from blood transfusions include febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, acute hemolytic transfusion reaction (ABO incompatibility), transfusion-associated lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), infections, and anaphylaxis. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines specifically highlight the complications of delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction, iron overload, and hyperviscosity in SCA.Approximately 30% of SCA patients have alloantibodies.2 SCA patients may also develop autoimmunization, an immune response to their own RBC, particularly if the patient has multiple autoantibodies.

Infection is a risk for all individuals receiving transfusion. Screening for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, human T-cell lymphotropic virus, syphilis, West Nile virus, Trympanosoma, and bacteria are routinely performed but not 100% conclusive. Other diseases not routinely screened for include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Babesia, human herpesvirus-8, dengue fever, malaria, and newer concerns such as Zika virus. 2,3

Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions present as an increase in body temperature of more than 1° C during or shortly after receiving a blood transfusion in the absence of other pyrexic stimulus. Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction occurs more frequently in patients with a previous history of transfusions. The use of leukoreduced RBCs reduces the occurrence to less than 1%.2

TRALI presents with the acute onset of hypoxemia and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema within 6 hours of a blood transfusion in the absence of other etiologies. The mechanism of TRALI is caused by an inflammatory response causing injury to the alveolar capillary membrane and the development of pulmonary edema.1

TACO presents with cardiogenic pulmonary edema not from another etiology. This is usually seen after transfusion of excessive volumes of blood or after excessively rapid rates of transfusion.1

Delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction (DHTR) may be a life-threatening immune response to donor cell antigens. The reaction is identified by a drop in the patient’s hemoglobin below the pretransfusion level, reticulocytopenia, a positive direct Coombs test, and occasionally jaundice on physical exam.2 Patients may have an unexpectedly high hemoglobin S% after transfusion from the hemolysis of donor cells. The pathognomonic feature is development of a new alloantibody. DHTR occurs more often in individuals who have received recurrent transfusions and has been reported in 4%-11% of transfused SCA patients.3 Donor and native cells hemolyze intra- and extravascularly 5-20 days after receiving a transfusion.2 DHTR is likely underestimated in SCA as it may be confused for a vaso-occlusive crisis.

Iron overload from recurrent transfusions is a slow, chronic process resulting in end organ damage of the heart, liver, and pancreas. It is associated with more frequent hospitalizations and higher mortality in SCA.3 The average person has 4-5 g of iron with no process to remove the excess. One unit of packed red blood cells adds 250-300 mg of iron.2 Ferritin somewhat correlates to iron overload but is not a reliable method because it is an acute-phase reactant. Liver biopsy is the current diagnostic gold standard, however, noninvasive MRI is gaining diagnostic credibility.

Hb SS blood has up to 10 times higher viscosity than does non–sickle cell blood at the same hemoglobin level. RBC transfusion increases the already hyperviscous state of SCA resulting in slow blood flow through vessels. The slow flow through small vessels from hyperviscosity may result in additional sickling and trigger or worsen a vaso-occlusive crisis. Avascular necrosis is theorized to be a result of hyperviscosity as it occurs more commonly in sickle cell patients with higher hemoglobin. It is important not to transfuse to baseline or above a hemoglobin of 10 g/dL to avoid worsening hyperviscosity.2

When to consider transfusion

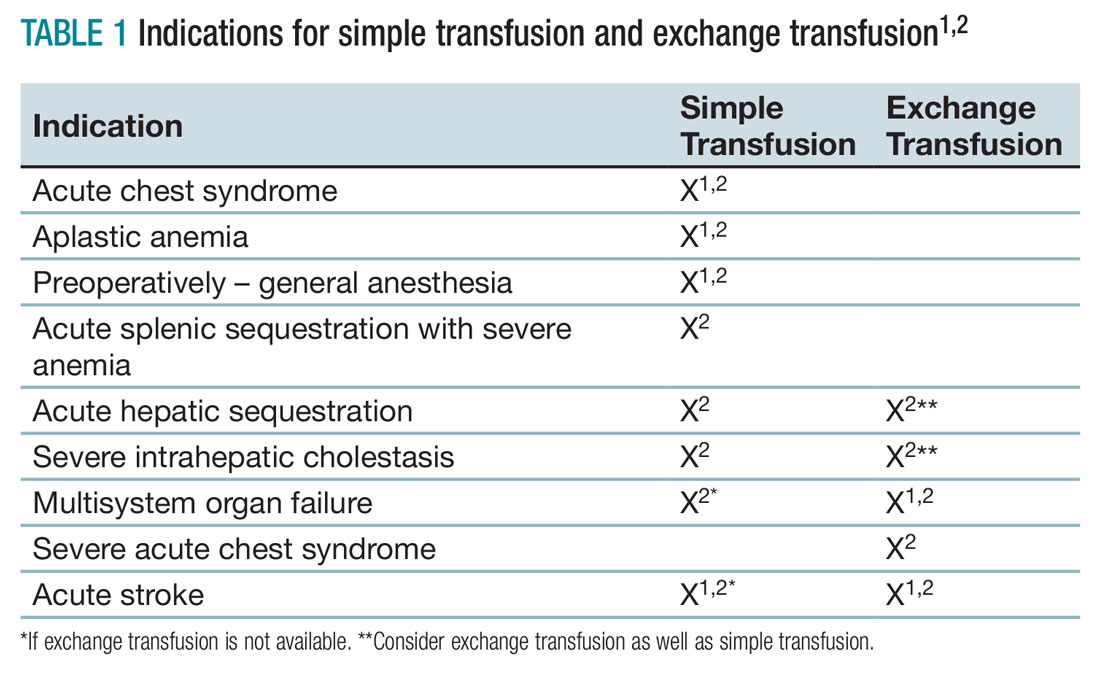

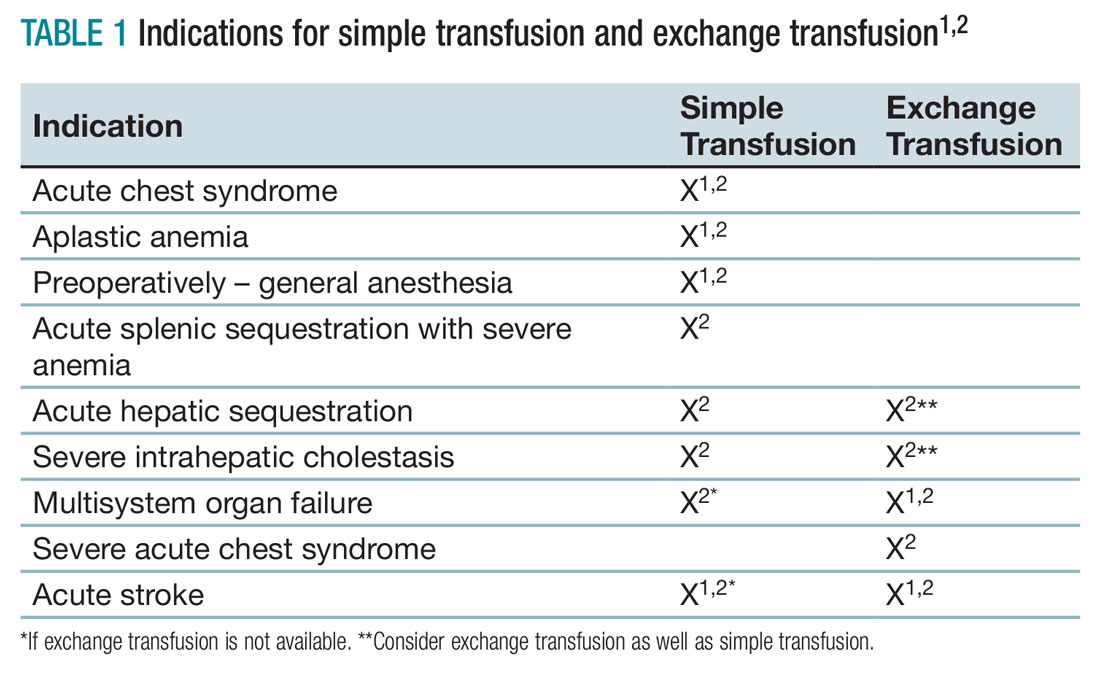

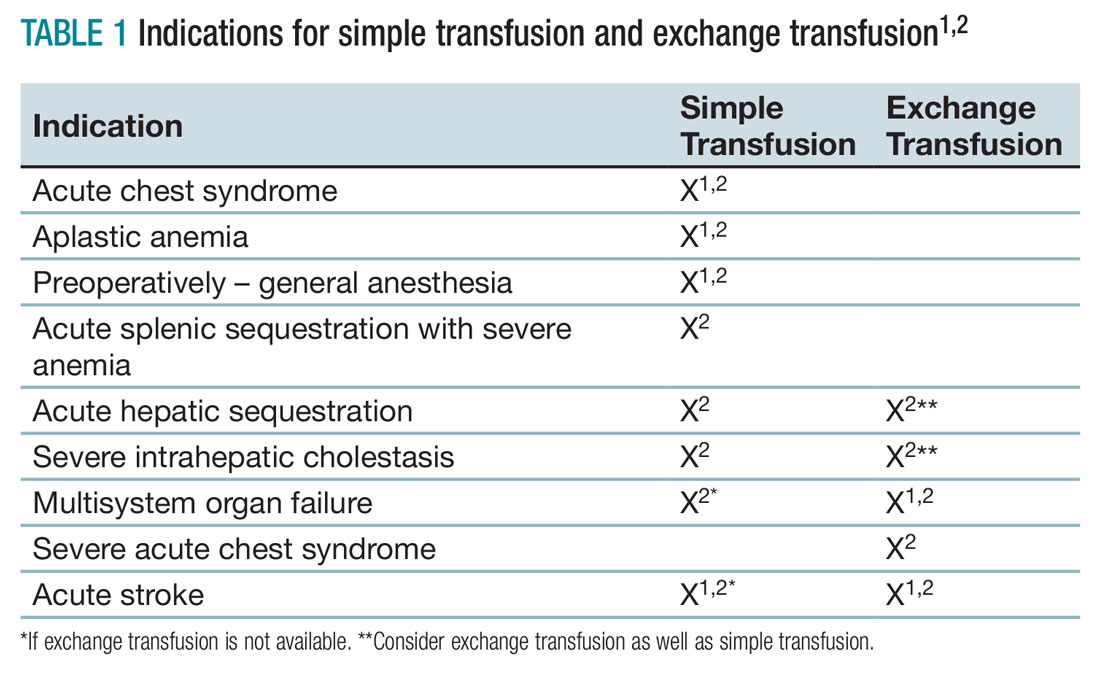

Unfortunately, there are no strong randomized controlled trials to definitively dictate when simple transfusions or exchange transfusions are indicated. Acute simple transfusions should be considered in certain circumstances including acute chest syndrome, acute stroke, aplastic anemia, preoperative transfusion, splenic sequestration plus severe anemia, acute hepatic sequestration, and severe acute intrahepatic cholestasis.2

Few studies compare simple transfusion and exchange transfusion.2 The decision to use exchange transfusion over simple transfusion often is based on availability of exchange transfusion, ability of simple transfusion to decrease the percentage of hemoglobin S, and/or the patient’s current hemoglobin to avoid hyperviscosity from simple transfusion.3 Exchange transfusion should be considered for hemoglobin greater than 8-9 g/dL.2

Acute hepatic sequestration (AHS) occurs with the sequestration of RBCs in the liver and is marked by greater than 2 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin and hepatic enlargement, compared with baseline. The stretching of the hepatic capsule results in right upper quadrant pain. AHS often develops over a few hours to a few days with only mild elevation of liver function tests. AHS may be underestimated as two-thirds of SCA patients have hepatomegaly. Unless the hepatomegaly is radiographically monitored it may not be possible to determine an acute increase in liver size.2

Aplastic crisis presents as a gradual onset of fatigue, shortness of breath, and sometimes syncope or fever. Physical examination may reveal tachycardia and occasionally frank heart failure. The hemoglobin is usually far below the patient’s baseline level with an inappropriate, severely low reticulocyte count. Aplastic crisis should be transfused immediately because of the markedly short life expectancy of hemoglobin S RBCs, but does not need to be transfused to baseline.2

Acute splenic sequestration presents as a decrease in hemoglobin by greater than 2 g/dL, elevated reticulocyte count and circulating nucleated red blood cells, thrombocytopenia, and sudden splenomegaly.2 The goal of transfusion is for partial correction because of the risk of hyperviscosity when the spleen releases the sequestered RBCs.

Acute chest syndrome (ACS) presents as a pneumonia radiographically consistent with a respiratory tract infection caused by cough, shortness of breath, retractions, and/or rales. ACS is the most common cause of death in SCA. ACS is usually from infection but may be because of fat embolism, intrapulmonary aggregates of sickled cells, atelectasis, or pulmonary edema.2 If ACS has a hemoglobin decrease of greater than 1g/dL, consider transfusion.1,2

Severe acute chest syndrome is distinguished by radiographic evidence of multilobe pneumonia, increased work of breathing, pleural effusions, and oxygen saturation below 95% with supplemental oxygen. Severe ACS may have a decrease in hemoglobin despite receiving transfusion. Exchange transfusion is recommended because of the high mortality in severe ACS.2

Preoperative transfusion is used to decrease the incidence of postoperative vaso-occlusive crisis, acute stroke, or ACS for patients receiving general anesthesia. The goal for transfusion hemoglobin is 10g/dL. In SCA patients with a hemoglobin greater than 9g/dL, exchange transfusion may be considered to avoid hyperviscosity.1,2

Multisystem organ failure (MSOF) is severe and life-threatening lung, liver, and/or kidney failure. MSOF may occur after several days of hospitalization. It is often unanticipated and swift, frequently presenting with fever, a rapid increase in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and altered mental status. Lung failure often presents as ACS. Liver failure is marked by hyperbilirubinemia, elevated transaminases, and coagulopathy. Kidney failure is marked by elevated creatinine, with or without change in urine output and hyperkalemia. Rapid treatment with transfusion or exchange transfusion reduces mortality.

The incidence of acute ischemic stroke in SCA decreases with prophylactic transfusion of patients with elevated transcranial Dopplers. Acute stroke is usually secondary to stenosis or an occlusion of the internal carotid or middle cerebral artery. Acute hemorrhagic stroke may present as severe headache and loss of consciousness. Acute stroke should be confirmed radiographically, then exchange transfusion instituted rapidly.2

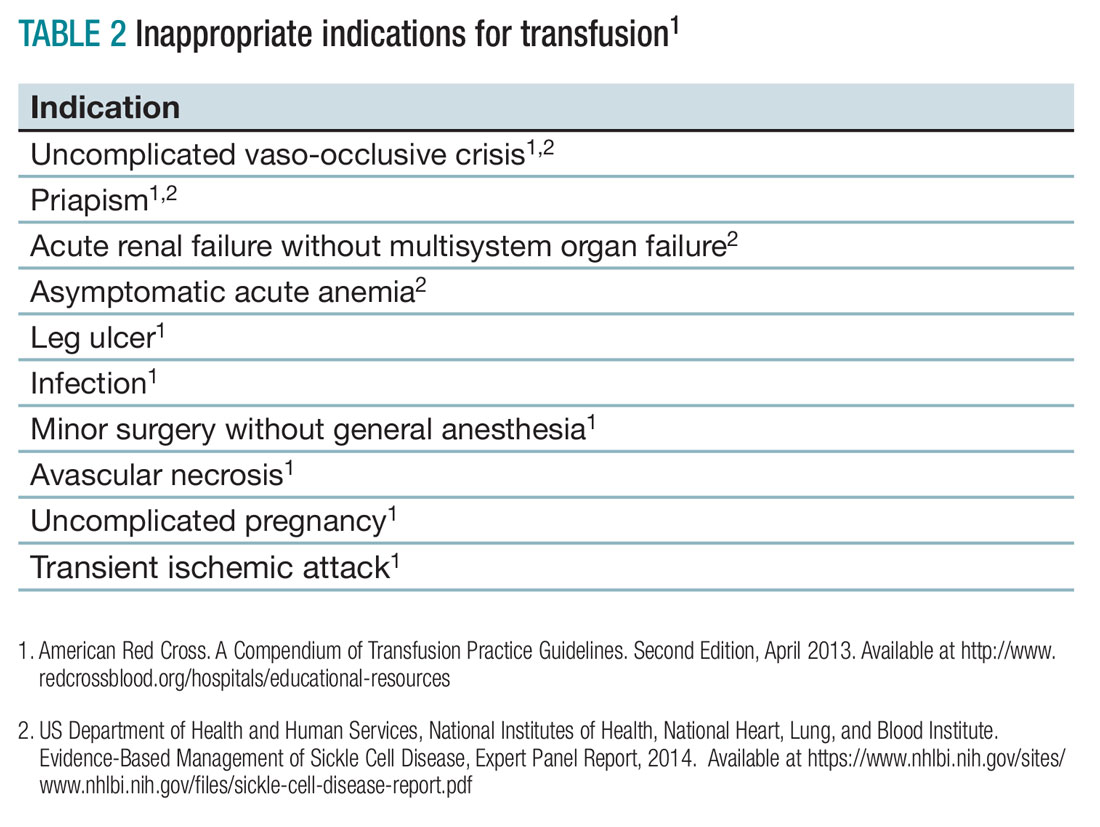

When not to transfuse

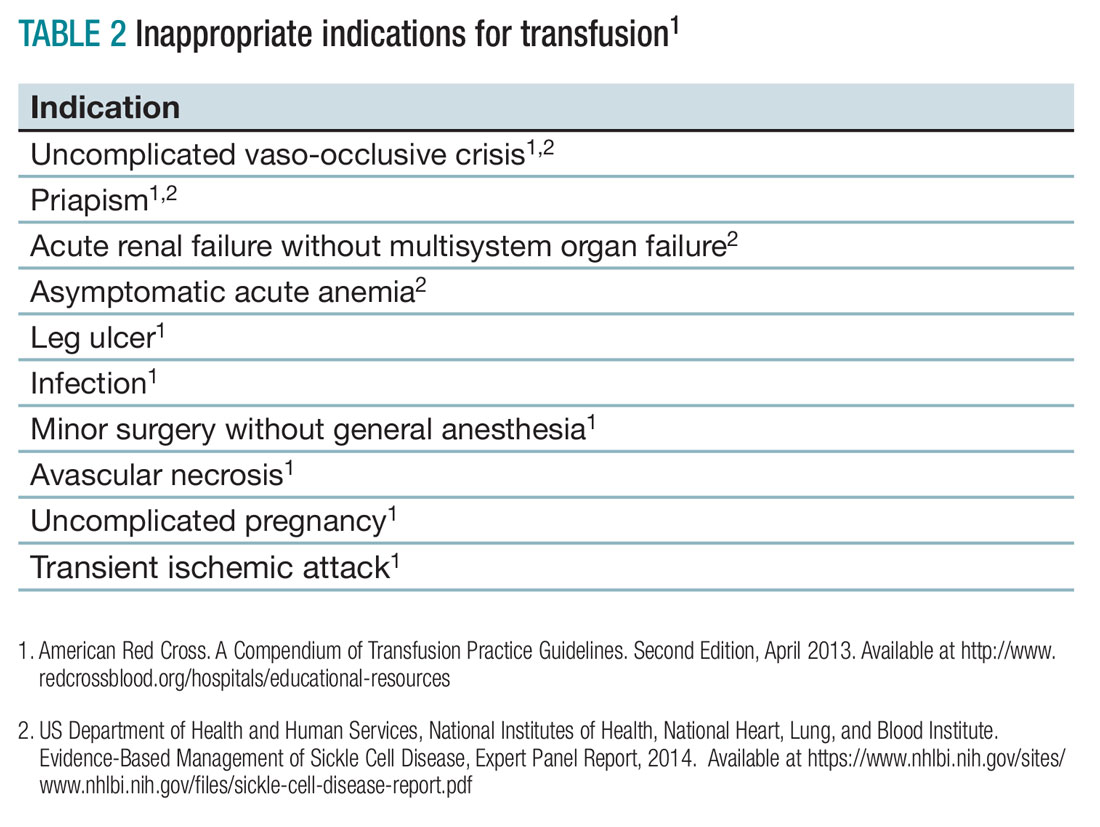

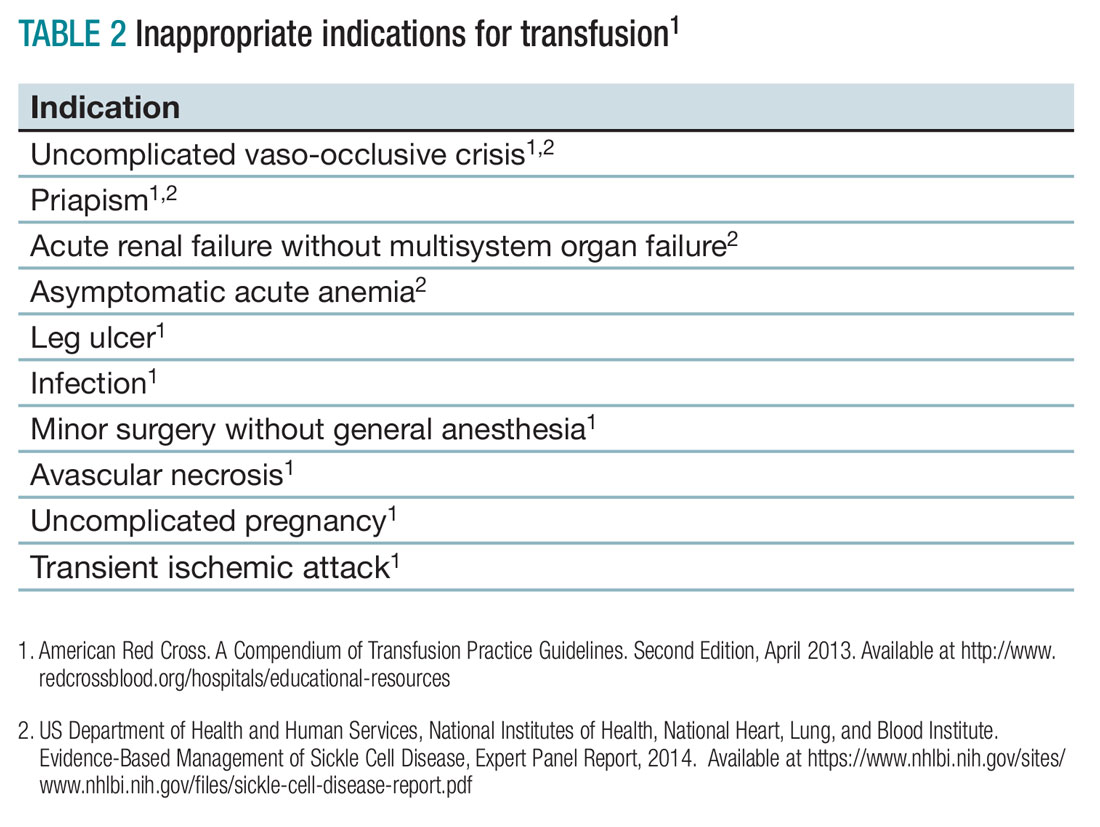

- Do not transfuse for simple vaso-occlusive crisis in the absence of symptoms attributable to acute anemia.1-3

- Do not transfuse for priapism.2

- Do not transfuse for acute renal failure unless there is MSOF.2

Back to the case

The patient was admitted for vaso-occlusive crisis and was started on patient-controlled analgesia with hydromorphone and IV fluids. Azithromycin and ceftriaxone were initiated empirically for community-acquired pneumonia. She was given one unit of phenotypically matched, leukoreduced RBCs for acute chest syndrome. Her hemoglobin increased to 6.1 g/dL. Her fever resolved on day 2, and her dyspnea improved on day 3 of hospitalization. She was weaned off of her patient-controlled analgesia on day 4 and discharged home on day 5 with moxifloxacin to complete 7 days of antibiotics.

Bottom line

Acute simple transfusions and exchange transfusions are indicated for multiple serious and life-threatening complications in SCA. However, transfusion has many serious and life-threatening potential adverse effects. It is essential to conduct a thorough risk-benefit analysis for each individual SCA patient. Whenever possible, intensive phenotypically matched and leukoreduced RBCs should be used. TH

References

1. American Red Cross. A Compendium of Transfusion Practice Guidelines. Second Edition, April 2013.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease, Expert Panel Report, 2014.

3. Smith-Whitely, K and Thompson, AA. Indications and complications of transfusions in sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(2):358-64.

- SCA patients are at risk for serious transfusion complications including iron overload, delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction, and hyperviscosity in addition to the usual transfusion risks.

- Do not transfuse an uncomplicated vaso-occlusive crisis without symptomatic anemia.1-3

- Repeated transfusions create alloimmunization in SCA patients increasing risk for life-threatening transfusion reactions and difficulty locating phenotypically matched RBCs.

- Transfusion should be considered in SCA patients experiencing acute chest syndrome, aplastic anemia, splenic sequestration with acute anemia, acute hepatic sequestration, and severe intrahepatic cholestasis.1,2

- If available, exchange transfusion should be considered for SCA patients experiencing multisystem organ failure, acute stroke, and severe acute chest syndrome.1,2

- American Red Cross. A Compendium of Transfusion Practice Guidelines. Second Edition, April 2013.

Case

A 19-year-old female with a history of sickle cell anemia and hemoglobin SS, presents with a 2-day history of worsening lower back pain and dyspnea. Physical exam reveals oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, a temperature of 39.2° C, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, and right-sided rales. Her hemoglobin is 5.3 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin of 7.8 g/dL). Chest radiograph reveals a right upper lobe pneumonia, and she is diagnosed with acute chest syndrome.

What are indications and complications of acute transfusion in sickle cell anemia?

Background

Chronic hemolytic anemia is a trademark of sickle cell anemia (SCA) or hemoglobin (Hb) SS as is acute anemia during illness or vaso-occlusive crises. Blood transfusions were the first therapy used in sickle cell disease, long before the pathophysiology was understood. Transfusion of red blood cells (RBC) increases the percentage of circulating normal Hb A, thereby decreasing the percentage of abnormal, sickled cells. This increases the oxygen-carrying capacity of the patient’s RBCs, improves organ perfusion, prevents organ damage, and can be life saving. SCA patients are the largest users of the United States rare donor blood bank registry.1

Unfortunately, transfusion comes with many risks including infection, transfusion reactions, alloimmunization, iron overload, hyperviscosity, and volume overload.

As SCA is a low-prevalence disease in a minority population, very few studies have been performed. Currently, the guidance available regarding blood transfusion is primarily based on expert opinion.

What to transfuse

Leukoreduced and intensive phenotypically matched RBC are not possible in many medical centers. Previous studies have noted decreased incidence of febrile nonhemolytic anemia transfusion reactions, cytomegalovirus transmission, and human leukocyte antigen alloimmunization in leukoreduced blood transfusions, however, these studies did not include SCA patients.2

Complications from transfusion

Complications from blood transfusions include febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, acute hemolytic transfusion reaction (ABO incompatibility), transfusion-associated lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), infections, and anaphylaxis. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines specifically highlight the complications of delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction, iron overload, and hyperviscosity in SCA.Approximately 30% of SCA patients have alloantibodies.2 SCA patients may also develop autoimmunization, an immune response to their own RBC, particularly if the patient has multiple autoantibodies.

Infection is a risk for all individuals receiving transfusion. Screening for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, human T-cell lymphotropic virus, syphilis, West Nile virus, Trympanosoma, and bacteria are routinely performed but not 100% conclusive. Other diseases not routinely screened for include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Babesia, human herpesvirus-8, dengue fever, malaria, and newer concerns such as Zika virus. 2,3

Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions present as an increase in body temperature of more than 1° C during or shortly after receiving a blood transfusion in the absence of other pyrexic stimulus. Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction occurs more frequently in patients with a previous history of transfusions. The use of leukoreduced RBCs reduces the occurrence to less than 1%.2

TRALI presents with the acute onset of hypoxemia and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema within 6 hours of a blood transfusion in the absence of other etiologies. The mechanism of TRALI is caused by an inflammatory response causing injury to the alveolar capillary membrane and the development of pulmonary edema.1

TACO presents with cardiogenic pulmonary edema not from another etiology. This is usually seen after transfusion of excessive volumes of blood or after excessively rapid rates of transfusion.1

Delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction (DHTR) may be a life-threatening immune response to donor cell antigens. The reaction is identified by a drop in the patient’s hemoglobin below the pretransfusion level, reticulocytopenia, a positive direct Coombs test, and occasionally jaundice on physical exam.2 Patients may have an unexpectedly high hemoglobin S% after transfusion from the hemolysis of donor cells. The pathognomonic feature is development of a new alloantibody. DHTR occurs more often in individuals who have received recurrent transfusions and has been reported in 4%-11% of transfused SCA patients.3 Donor and native cells hemolyze intra- and extravascularly 5-20 days after receiving a transfusion.2 DHTR is likely underestimated in SCA as it may be confused for a vaso-occlusive crisis.

Iron overload from recurrent transfusions is a slow, chronic process resulting in end organ damage of the heart, liver, and pancreas. It is associated with more frequent hospitalizations and higher mortality in SCA.3 The average person has 4-5 g of iron with no process to remove the excess. One unit of packed red blood cells adds 250-300 mg of iron.2 Ferritin somewhat correlates to iron overload but is not a reliable method because it is an acute-phase reactant. Liver biopsy is the current diagnostic gold standard, however, noninvasive MRI is gaining diagnostic credibility.

Hb SS blood has up to 10 times higher viscosity than does non–sickle cell blood at the same hemoglobin level. RBC transfusion increases the already hyperviscous state of SCA resulting in slow blood flow through vessels. The slow flow through small vessels from hyperviscosity may result in additional sickling and trigger or worsen a vaso-occlusive crisis. Avascular necrosis is theorized to be a result of hyperviscosity as it occurs more commonly in sickle cell patients with higher hemoglobin. It is important not to transfuse to baseline or above a hemoglobin of 10 g/dL to avoid worsening hyperviscosity.2

When to consider transfusion

Unfortunately, there are no strong randomized controlled trials to definitively dictate when simple transfusions or exchange transfusions are indicated. Acute simple transfusions should be considered in certain circumstances including acute chest syndrome, acute stroke, aplastic anemia, preoperative transfusion, splenic sequestration plus severe anemia, acute hepatic sequestration, and severe acute intrahepatic cholestasis.2

Few studies compare simple transfusion and exchange transfusion.2 The decision to use exchange transfusion over simple transfusion often is based on availability of exchange transfusion, ability of simple transfusion to decrease the percentage of hemoglobin S, and/or the patient’s current hemoglobin to avoid hyperviscosity from simple transfusion.3 Exchange transfusion should be considered for hemoglobin greater than 8-9 g/dL.2

Acute hepatic sequestration (AHS) occurs with the sequestration of RBCs in the liver and is marked by greater than 2 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin and hepatic enlargement, compared with baseline. The stretching of the hepatic capsule results in right upper quadrant pain. AHS often develops over a few hours to a few days with only mild elevation of liver function tests. AHS may be underestimated as two-thirds of SCA patients have hepatomegaly. Unless the hepatomegaly is radiographically monitored it may not be possible to determine an acute increase in liver size.2

Aplastic crisis presents as a gradual onset of fatigue, shortness of breath, and sometimes syncope or fever. Physical examination may reveal tachycardia and occasionally frank heart failure. The hemoglobin is usually far below the patient’s baseline level with an inappropriate, severely low reticulocyte count. Aplastic crisis should be transfused immediately because of the markedly short life expectancy of hemoglobin S RBCs, but does not need to be transfused to baseline.2

Acute splenic sequestration presents as a decrease in hemoglobin by greater than 2 g/dL, elevated reticulocyte count and circulating nucleated red blood cells, thrombocytopenia, and sudden splenomegaly.2 The goal of transfusion is for partial correction because of the risk of hyperviscosity when the spleen releases the sequestered RBCs.

Acute chest syndrome (ACS) presents as a pneumonia radiographically consistent with a respiratory tract infection caused by cough, shortness of breath, retractions, and/or rales. ACS is the most common cause of death in SCA. ACS is usually from infection but may be because of fat embolism, intrapulmonary aggregates of sickled cells, atelectasis, or pulmonary edema.2 If ACS has a hemoglobin decrease of greater than 1g/dL, consider transfusion.1,2

Severe acute chest syndrome is distinguished by radiographic evidence of multilobe pneumonia, increased work of breathing, pleural effusions, and oxygen saturation below 95% with supplemental oxygen. Severe ACS may have a decrease in hemoglobin despite receiving transfusion. Exchange transfusion is recommended because of the high mortality in severe ACS.2

Preoperative transfusion is used to decrease the incidence of postoperative vaso-occlusive crisis, acute stroke, or ACS for patients receiving general anesthesia. The goal for transfusion hemoglobin is 10g/dL. In SCA patients with a hemoglobin greater than 9g/dL, exchange transfusion may be considered to avoid hyperviscosity.1,2

Multisystem organ failure (MSOF) is severe and life-threatening lung, liver, and/or kidney failure. MSOF may occur after several days of hospitalization. It is often unanticipated and swift, frequently presenting with fever, a rapid increase in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and altered mental status. Lung failure often presents as ACS. Liver failure is marked by hyperbilirubinemia, elevated transaminases, and coagulopathy. Kidney failure is marked by elevated creatinine, with or without change in urine output and hyperkalemia. Rapid treatment with transfusion or exchange transfusion reduces mortality.

The incidence of acute ischemic stroke in SCA decreases with prophylactic transfusion of patients with elevated transcranial Dopplers. Acute stroke is usually secondary to stenosis or an occlusion of the internal carotid or middle cerebral artery. Acute hemorrhagic stroke may present as severe headache and loss of consciousness. Acute stroke should be confirmed radiographically, then exchange transfusion instituted rapidly.2

When not to transfuse

- Do not transfuse for simple vaso-occlusive crisis in the absence of symptoms attributable to acute anemia.1-3

- Do not transfuse for priapism.2

- Do not transfuse for acute renal failure unless there is MSOF.2

Back to the case

The patient was admitted for vaso-occlusive crisis and was started on patient-controlled analgesia with hydromorphone and IV fluids. Azithromycin and ceftriaxone were initiated empirically for community-acquired pneumonia. She was given one unit of phenotypically matched, leukoreduced RBCs for acute chest syndrome. Her hemoglobin increased to 6.1 g/dL. Her fever resolved on day 2, and her dyspnea improved on day 3 of hospitalization. She was weaned off of her patient-controlled analgesia on day 4 and discharged home on day 5 with moxifloxacin to complete 7 days of antibiotics.

Bottom line

Acute simple transfusions and exchange transfusions are indicated for multiple serious and life-threatening complications in SCA. However, transfusion has many serious and life-threatening potential adverse effects. It is essential to conduct a thorough risk-benefit analysis for each individual SCA patient. Whenever possible, intensive phenotypically matched and leukoreduced RBCs should be used. TH

References

1. American Red Cross. A Compendium of Transfusion Practice Guidelines. Second Edition, April 2013.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease, Expert Panel Report, 2014.

3. Smith-Whitely, K and Thompson, AA. Indications and complications of transfusions in sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(2):358-64.

- SCA patients are at risk for serious transfusion complications including iron overload, delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction, and hyperviscosity in addition to the usual transfusion risks.

- Do not transfuse an uncomplicated vaso-occlusive crisis without symptomatic anemia.1-3

- Repeated transfusions create alloimmunization in SCA patients increasing risk for life-threatening transfusion reactions and difficulty locating phenotypically matched RBCs.

- Transfusion should be considered in SCA patients experiencing acute chest syndrome, aplastic anemia, splenic sequestration with acute anemia, acute hepatic sequestration, and severe intrahepatic cholestasis.1,2

- If available, exchange transfusion should be considered for SCA patients experiencing multisystem organ failure, acute stroke, and severe acute chest syndrome.1,2

- American Red Cross. A Compendium of Transfusion Practice Guidelines. Second Edition, April 2013.

Case

A 19-year-old female with a history of sickle cell anemia and hemoglobin SS, presents with a 2-day history of worsening lower back pain and dyspnea. Physical exam reveals oxygen saturation of 87% on room air, a temperature of 39.2° C, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute, and right-sided rales. Her hemoglobin is 5.3 g/dL (baseline hemoglobin of 7.8 g/dL). Chest radiograph reveals a right upper lobe pneumonia, and she is diagnosed with acute chest syndrome.

What are indications and complications of acute transfusion in sickle cell anemia?

Background

Chronic hemolytic anemia is a trademark of sickle cell anemia (SCA) or hemoglobin (Hb) SS as is acute anemia during illness or vaso-occlusive crises. Blood transfusions were the first therapy used in sickle cell disease, long before the pathophysiology was understood. Transfusion of red blood cells (RBC) increases the percentage of circulating normal Hb A, thereby decreasing the percentage of abnormal, sickled cells. This increases the oxygen-carrying capacity of the patient’s RBCs, improves organ perfusion, prevents organ damage, and can be life saving. SCA patients are the largest users of the United States rare donor blood bank registry.1

Unfortunately, transfusion comes with many risks including infection, transfusion reactions, alloimmunization, iron overload, hyperviscosity, and volume overload.

As SCA is a low-prevalence disease in a minority population, very few studies have been performed. Currently, the guidance available regarding blood transfusion is primarily based on expert opinion.

What to transfuse

Leukoreduced and intensive phenotypically matched RBC are not possible in many medical centers. Previous studies have noted decreased incidence of febrile nonhemolytic anemia transfusion reactions, cytomegalovirus transmission, and human leukocyte antigen alloimmunization in leukoreduced blood transfusions, however, these studies did not include SCA patients.2

Complications from transfusion

Complications from blood transfusions include febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction, acute hemolytic transfusion reaction (ABO incompatibility), transfusion-associated lung injury (TRALI), transfusion-associated circulatory overload (TACO), infections, and anaphylaxis. The National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute guidelines specifically highlight the complications of delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction, iron overload, and hyperviscosity in SCA.Approximately 30% of SCA patients have alloantibodies.2 SCA patients may also develop autoimmunization, an immune response to their own RBC, particularly if the patient has multiple autoantibodies.

Infection is a risk for all individuals receiving transfusion. Screening for hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV, human T-cell lymphotropic virus, syphilis, West Nile virus, Trympanosoma, and bacteria are routinely performed but not 100% conclusive. Other diseases not routinely screened for include Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, Babesia, human herpesvirus-8, dengue fever, malaria, and newer concerns such as Zika virus. 2,3

Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reactions present as an increase in body temperature of more than 1° C during or shortly after receiving a blood transfusion in the absence of other pyrexic stimulus. Febrile nonhemolytic transfusion reaction occurs more frequently in patients with a previous history of transfusions. The use of leukoreduced RBCs reduces the occurrence to less than 1%.2

TRALI presents with the acute onset of hypoxemia and noncardiogenic pulmonary edema within 6 hours of a blood transfusion in the absence of other etiologies. The mechanism of TRALI is caused by an inflammatory response causing injury to the alveolar capillary membrane and the development of pulmonary edema.1

TACO presents with cardiogenic pulmonary edema not from another etiology. This is usually seen after transfusion of excessive volumes of blood or after excessively rapid rates of transfusion.1

Delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction (DHTR) may be a life-threatening immune response to donor cell antigens. The reaction is identified by a drop in the patient’s hemoglobin below the pretransfusion level, reticulocytopenia, a positive direct Coombs test, and occasionally jaundice on physical exam.2 Patients may have an unexpectedly high hemoglobin S% after transfusion from the hemolysis of donor cells. The pathognomonic feature is development of a new alloantibody. DHTR occurs more often in individuals who have received recurrent transfusions and has been reported in 4%-11% of transfused SCA patients.3 Donor and native cells hemolyze intra- and extravascularly 5-20 days after receiving a transfusion.2 DHTR is likely underestimated in SCA as it may be confused for a vaso-occlusive crisis.

Iron overload from recurrent transfusions is a slow, chronic process resulting in end organ damage of the heart, liver, and pancreas. It is associated with more frequent hospitalizations and higher mortality in SCA.3 The average person has 4-5 g of iron with no process to remove the excess. One unit of packed red blood cells adds 250-300 mg of iron.2 Ferritin somewhat correlates to iron overload but is not a reliable method because it is an acute-phase reactant. Liver biopsy is the current diagnostic gold standard, however, noninvasive MRI is gaining diagnostic credibility.

Hb SS blood has up to 10 times higher viscosity than does non–sickle cell blood at the same hemoglobin level. RBC transfusion increases the already hyperviscous state of SCA resulting in slow blood flow through vessels. The slow flow through small vessels from hyperviscosity may result in additional sickling and trigger or worsen a vaso-occlusive crisis. Avascular necrosis is theorized to be a result of hyperviscosity as it occurs more commonly in sickle cell patients with higher hemoglobin. It is important not to transfuse to baseline or above a hemoglobin of 10 g/dL to avoid worsening hyperviscosity.2

When to consider transfusion

Unfortunately, there are no strong randomized controlled trials to definitively dictate when simple transfusions or exchange transfusions are indicated. Acute simple transfusions should be considered in certain circumstances including acute chest syndrome, acute stroke, aplastic anemia, preoperative transfusion, splenic sequestration plus severe anemia, acute hepatic sequestration, and severe acute intrahepatic cholestasis.2

Few studies compare simple transfusion and exchange transfusion.2 The decision to use exchange transfusion over simple transfusion often is based on availability of exchange transfusion, ability of simple transfusion to decrease the percentage of hemoglobin S, and/or the patient’s current hemoglobin to avoid hyperviscosity from simple transfusion.3 Exchange transfusion should be considered for hemoglobin greater than 8-9 g/dL.2

Acute hepatic sequestration (AHS) occurs with the sequestration of RBCs in the liver and is marked by greater than 2 g/dL decrease in hemoglobin and hepatic enlargement, compared with baseline. The stretching of the hepatic capsule results in right upper quadrant pain. AHS often develops over a few hours to a few days with only mild elevation of liver function tests. AHS may be underestimated as two-thirds of SCA patients have hepatomegaly. Unless the hepatomegaly is radiographically monitored it may not be possible to determine an acute increase in liver size.2

Aplastic crisis presents as a gradual onset of fatigue, shortness of breath, and sometimes syncope or fever. Physical examination may reveal tachycardia and occasionally frank heart failure. The hemoglobin is usually far below the patient’s baseline level with an inappropriate, severely low reticulocyte count. Aplastic crisis should be transfused immediately because of the markedly short life expectancy of hemoglobin S RBCs, but does not need to be transfused to baseline.2

Acute splenic sequestration presents as a decrease in hemoglobin by greater than 2 g/dL, elevated reticulocyte count and circulating nucleated red blood cells, thrombocytopenia, and sudden splenomegaly.2 The goal of transfusion is for partial correction because of the risk of hyperviscosity when the spleen releases the sequestered RBCs.

Acute chest syndrome (ACS) presents as a pneumonia radiographically consistent with a respiratory tract infection caused by cough, shortness of breath, retractions, and/or rales. ACS is the most common cause of death in SCA. ACS is usually from infection but may be because of fat embolism, intrapulmonary aggregates of sickled cells, atelectasis, or pulmonary edema.2 If ACS has a hemoglobin decrease of greater than 1g/dL, consider transfusion.1,2

Severe acute chest syndrome is distinguished by radiographic evidence of multilobe pneumonia, increased work of breathing, pleural effusions, and oxygen saturation below 95% with supplemental oxygen. Severe ACS may have a decrease in hemoglobin despite receiving transfusion. Exchange transfusion is recommended because of the high mortality in severe ACS.2

Preoperative transfusion is used to decrease the incidence of postoperative vaso-occlusive crisis, acute stroke, or ACS for patients receiving general anesthesia. The goal for transfusion hemoglobin is 10g/dL. In SCA patients with a hemoglobin greater than 9g/dL, exchange transfusion may be considered to avoid hyperviscosity.1,2

Multisystem organ failure (MSOF) is severe and life-threatening lung, liver, and/or kidney failure. MSOF may occur after several days of hospitalization. It is often unanticipated and swift, frequently presenting with fever, a rapid increase in anemia, thrombocytopenia, and altered mental status. Lung failure often presents as ACS. Liver failure is marked by hyperbilirubinemia, elevated transaminases, and coagulopathy. Kidney failure is marked by elevated creatinine, with or without change in urine output and hyperkalemia. Rapid treatment with transfusion or exchange transfusion reduces mortality.

The incidence of acute ischemic stroke in SCA decreases with prophylactic transfusion of patients with elevated transcranial Dopplers. Acute stroke is usually secondary to stenosis or an occlusion of the internal carotid or middle cerebral artery. Acute hemorrhagic stroke may present as severe headache and loss of consciousness. Acute stroke should be confirmed radiographically, then exchange transfusion instituted rapidly.2

When not to transfuse

- Do not transfuse for simple vaso-occlusive crisis in the absence of symptoms attributable to acute anemia.1-3

- Do not transfuse for priapism.2

- Do not transfuse for acute renal failure unless there is MSOF.2

Back to the case

The patient was admitted for vaso-occlusive crisis and was started on patient-controlled analgesia with hydromorphone and IV fluids. Azithromycin and ceftriaxone were initiated empirically for community-acquired pneumonia. She was given one unit of phenotypically matched, leukoreduced RBCs for acute chest syndrome. Her hemoglobin increased to 6.1 g/dL. Her fever resolved on day 2, and her dyspnea improved on day 3 of hospitalization. She was weaned off of her patient-controlled analgesia on day 4 and discharged home on day 5 with moxifloxacin to complete 7 days of antibiotics.

Bottom line

Acute simple transfusions and exchange transfusions are indicated for multiple serious and life-threatening complications in SCA. However, transfusion has many serious and life-threatening potential adverse effects. It is essential to conduct a thorough risk-benefit analysis for each individual SCA patient. Whenever possible, intensive phenotypically matched and leukoreduced RBCs should be used. TH

References

1. American Red Cross. A Compendium of Transfusion Practice Guidelines. Second Edition, April 2013.

2. US Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Evidence-Based Management of Sickle Cell Disease, Expert Panel Report, 2014.

3. Smith-Whitely, K and Thompson, AA. Indications and complications of transfusions in sickle cell disease. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2012;59(2):358-64.

- SCA patients are at risk for serious transfusion complications including iron overload, delayed hemolytic transfusion reaction, and hyperviscosity in addition to the usual transfusion risks.

- Do not transfuse an uncomplicated vaso-occlusive crisis without symptomatic anemia.1-3

- Repeated transfusions create alloimmunization in SCA patients increasing risk for life-threatening transfusion reactions and difficulty locating phenotypically matched RBCs.

- Transfusion should be considered in SCA patients experiencing acute chest syndrome, aplastic anemia, splenic sequestration with acute anemia, acute hepatic sequestration, and severe intrahepatic cholestasis.1,2

- If available, exchange transfusion should be considered for SCA patients experiencing multisystem organ failure, acute stroke, and severe acute chest syndrome.1,2

- American Red Cross. A Compendium of Transfusion Practice Guidelines. Second Edition, April 2013.

2016 Updates to AASLD Guidance Document on gastroesophageal bleeding in decompensated cirrhosis

Clinical question: What is appropriate inpatient management of a cirrhotic patient with acute esophageal or gastric variceal bleeding?

Study design: Guidance document developed by expert panel based on literature review, consensus conferences and authors’ clinical experience.

Background: Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal hemorrhage were last published in 2007 and endorsed by several major professional societies. Since then, there have been a number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and consensus conferences. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) published updated practice guidelines in 2016 that encompass pathophysiology, monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment of gastroesophageal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. This summary will focus on inpatient management for active gastroesophageal hemorrhage.

Synopsis of Inpatient Management for Esophageal Variceal Hemorrhage: The authors suggest that all VH requires ICU admission with the goal of acute control of bleeding, prevention of early recurrence, and reduction in 6-week mortality. Imaging to rule out portal vein thrombosis and HCC should be considered. Hepatic-Venous Pressure Gradient (HVPG) greater than 20 mm Hg is the strongest predictor of early rebleeding and death. However, catheter measurements of portal pressure are not available at most centers. As with any critically ill patient, stabilization of respiratory status and ensuring hemodynamic stability with volume resuscitation is paramount. RCTs evaluating transfusion goals suggest that a restrictive transfusion goal of HgB 7 g/dL is superior to a liberal goal of 9 g/dL. The authors hypothesize this may be related to lower HVPG observed with lower transfusion thresholds. In terms of treating coagulopathy, RCTs evaluating recombinant VIIa have not shown clear benefit. Correction of INR with FFPs similarly not recommended. No recommendations are made regarding utility of platelet transfusions. Vasoactive drugs should be administered when VH is suspected with the goal of decreasing splanchnic blood flow. Octreotide is the only vasoactive drug available in the United States. RCTs show that antibiotics administered prophylactically decrease infections, recurrent hemorrhage, and death. Ceftriaxone 1 g daily is the drug of choice in the United States and should be given up to a maximum of 7 days. A reasonable strategy is discontinuation of prophylaxis concurrently with discontinuation of vasoactive agents. After stabilization of hemodynamics, patients should proceed to endoscopy no more than 12 hours after presentation. Endoscopic Variceal Ligation (EVL) should be done if signs of active or recent variceal bleeding are found. After EVL, select patients at high risk of rebleeding (Child-Pugh B with active bleeding seen on endoscopy or Child-Pugh C patients) may benefit from TIPS within 72 hours. If TIPS is done, vasoactive agents can be discontinued. Otherwise, vasoactive agents should continue for 2-5 days with subsequent transition to nonselective beta blockers (NSBB) such as nadolol or propranolol. For secondary prophylaxis of esophageal bleeding, combination EVL and NSBB is first-line therapy. If recurrent hemorrhage occurs while on secondary prophylaxis, rescue TIPS is recommended.

Synopsis of Inpatient Management for Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage: Management of Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage is similar to Esophageal Variceal (EV) Hemorrhage and encompasses volume resuscitation, vasoactive drugs, and antibiotics with endoscopy shortly thereafter. Balloon tamponade can be used as a bridge to endoscopy in massive bleeds. In addition to the above, anatomic location of Gastric Varices (GV) affects choice of intervention. GOV1 varices extend from the gastric cardia to the lesser curvature and represent 75% of GV. If these are small, they can be managed with EVL. Otherwise these can be managed with injection of cyanoacrylate glue. GOV2 varices extend from the gastric cardia into the fundus. Isolated GV type 1 varices (IGV1) are located entirely in the fundus and have the highest propensity for bleeding. For these latter two types of “cardio-fundal varices” TIPS is the preferred intervention to control acute bleeding. Data on the efficacy of secondary prophylaxis for GV bleeding is limited. A combination of NSBB, cyanoacrylate injection, or TIPS can be considered. Balloon Occluded Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (BRTO) can be considered if fundal varices are associated with a large gastrorenal or splenorenal collateral. However, no RCTs have compared BRTO with other strategies. Isolated GV type 2 (IGV2) varices are not localized to the esophageal or gastric cardio-fundal region and are rare in cirrhotic patients but tend to occur in pre-hepatic portal hypertension. Management requires multidisciplinary input from endoscopists, hepatologists, interventional radiologists, and surgeons.

Bottom line: For esophageal variceal bleeding related to cirrhosis: volume resuscitation, antibiotic prophylaxis, and vasoactive agents are mainstays of therapy to stabilize patient for endoscopic intervention within 12 hours. This should be followed by early TIPS within 72 hours in high risk patients.

A similar approach applies to gastric variceal bleeding, but interventional management is dependent on the anatomic location of the varices in question.

Citations: Garcia-Tsao G et al. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis and management – 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2017 Jan;65[1]:310-35.

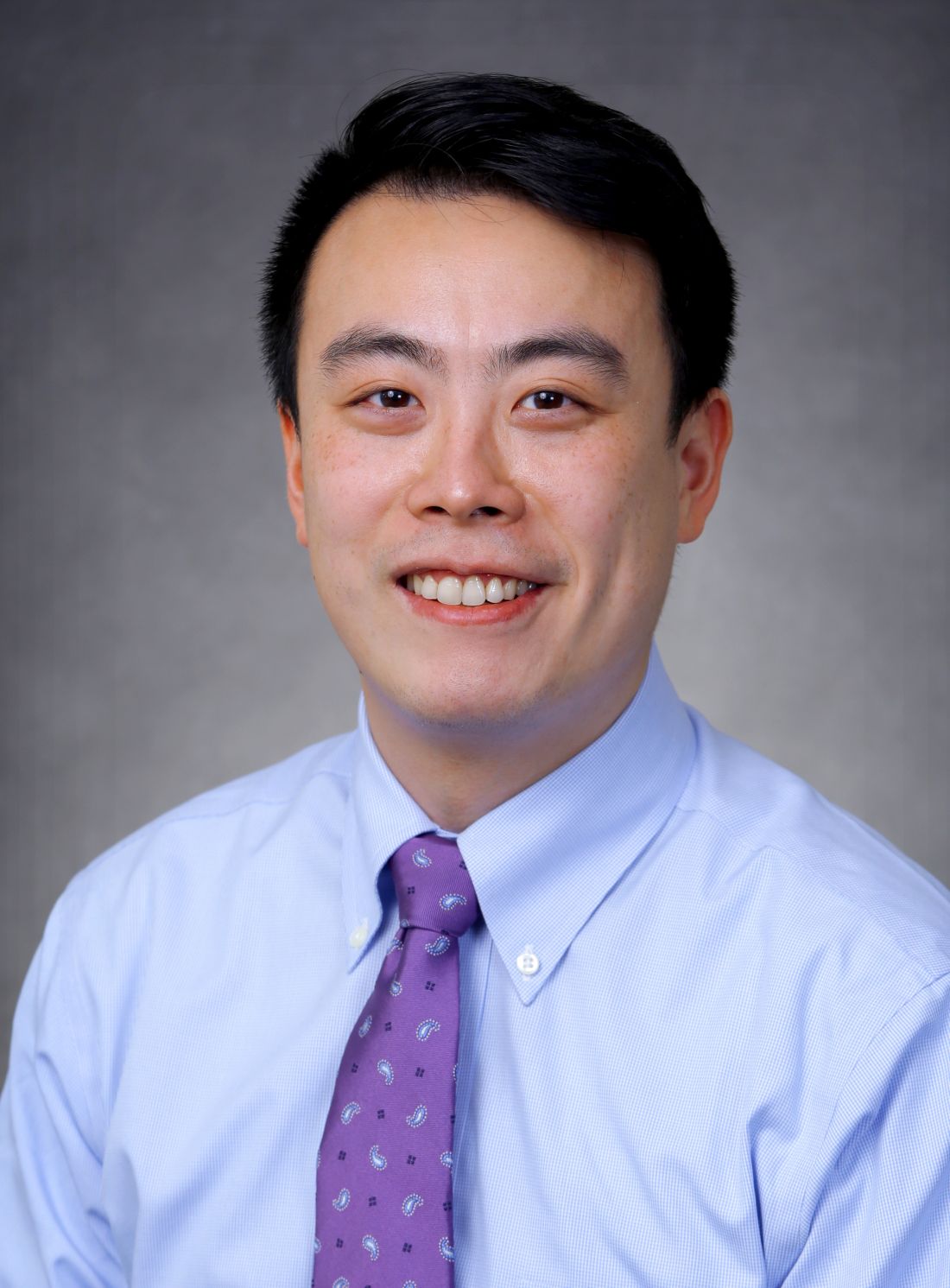

Dr. Lu is a hospitalist at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J.

Clinical question: What is appropriate inpatient management of a cirrhotic patient with acute esophageal or gastric variceal bleeding?

Study design: Guidance document developed by expert panel based on literature review, consensus conferences and authors’ clinical experience.

Background: Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal hemorrhage were last published in 2007 and endorsed by several major professional societies. Since then, there have been a number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and consensus conferences. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) published updated practice guidelines in 2016 that encompass pathophysiology, monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment of gastroesophageal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. This summary will focus on inpatient management for active gastroesophageal hemorrhage.

Synopsis of Inpatient Management for Esophageal Variceal Hemorrhage: The authors suggest that all VH requires ICU admission with the goal of acute control of bleeding, prevention of early recurrence, and reduction in 6-week mortality. Imaging to rule out portal vein thrombosis and HCC should be considered. Hepatic-Venous Pressure Gradient (HVPG) greater than 20 mm Hg is the strongest predictor of early rebleeding and death. However, catheter measurements of portal pressure are not available at most centers. As with any critically ill patient, stabilization of respiratory status and ensuring hemodynamic stability with volume resuscitation is paramount. RCTs evaluating transfusion goals suggest that a restrictive transfusion goal of HgB 7 g/dL is superior to a liberal goal of 9 g/dL. The authors hypothesize this may be related to lower HVPG observed with lower transfusion thresholds. In terms of treating coagulopathy, RCTs evaluating recombinant VIIa have not shown clear benefit. Correction of INR with FFPs similarly not recommended. No recommendations are made regarding utility of platelet transfusions. Vasoactive drugs should be administered when VH is suspected with the goal of decreasing splanchnic blood flow. Octreotide is the only vasoactive drug available in the United States. RCTs show that antibiotics administered prophylactically decrease infections, recurrent hemorrhage, and death. Ceftriaxone 1 g daily is the drug of choice in the United States and should be given up to a maximum of 7 days. A reasonable strategy is discontinuation of prophylaxis concurrently with discontinuation of vasoactive agents. After stabilization of hemodynamics, patients should proceed to endoscopy no more than 12 hours after presentation. Endoscopic Variceal Ligation (EVL) should be done if signs of active or recent variceal bleeding are found. After EVL, select patients at high risk of rebleeding (Child-Pugh B with active bleeding seen on endoscopy or Child-Pugh C patients) may benefit from TIPS within 72 hours. If TIPS is done, vasoactive agents can be discontinued. Otherwise, vasoactive agents should continue for 2-5 days with subsequent transition to nonselective beta blockers (NSBB) such as nadolol or propranolol. For secondary prophylaxis of esophageal bleeding, combination EVL and NSBB is first-line therapy. If recurrent hemorrhage occurs while on secondary prophylaxis, rescue TIPS is recommended.

Synopsis of Inpatient Management for Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage: Management of Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage is similar to Esophageal Variceal (EV) Hemorrhage and encompasses volume resuscitation, vasoactive drugs, and antibiotics with endoscopy shortly thereafter. Balloon tamponade can be used as a bridge to endoscopy in massive bleeds. In addition to the above, anatomic location of Gastric Varices (GV) affects choice of intervention. GOV1 varices extend from the gastric cardia to the lesser curvature and represent 75% of GV. If these are small, they can be managed with EVL. Otherwise these can be managed with injection of cyanoacrylate glue. GOV2 varices extend from the gastric cardia into the fundus. Isolated GV type 1 varices (IGV1) are located entirely in the fundus and have the highest propensity for bleeding. For these latter two types of “cardio-fundal varices” TIPS is the preferred intervention to control acute bleeding. Data on the efficacy of secondary prophylaxis for GV bleeding is limited. A combination of NSBB, cyanoacrylate injection, or TIPS can be considered. Balloon Occluded Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (BRTO) can be considered if fundal varices are associated with a large gastrorenal or splenorenal collateral. However, no RCTs have compared BRTO with other strategies. Isolated GV type 2 (IGV2) varices are not localized to the esophageal or gastric cardio-fundal region and are rare in cirrhotic patients but tend to occur in pre-hepatic portal hypertension. Management requires multidisciplinary input from endoscopists, hepatologists, interventional radiologists, and surgeons.

Bottom line: For esophageal variceal bleeding related to cirrhosis: volume resuscitation, antibiotic prophylaxis, and vasoactive agents are mainstays of therapy to stabilize patient for endoscopic intervention within 12 hours. This should be followed by early TIPS within 72 hours in high risk patients.

A similar approach applies to gastric variceal bleeding, but interventional management is dependent on the anatomic location of the varices in question.

Citations: Garcia-Tsao G et al. Portal hypertensive bleeding in cirrhosis: Risk stratification, diagnosis and management – 2016 practice guidance by the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases. Hepatology 2017 Jan;65[1]:310-35.

Dr. Lu is a hospitalist at Cooper University Hospital in Camden, N.J.

Clinical question: What is appropriate inpatient management of a cirrhotic patient with acute esophageal or gastric variceal bleeding?

Study design: Guidance document developed by expert panel based on literature review, consensus conferences and authors’ clinical experience.

Background: Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of gastroesophageal hemorrhage were last published in 2007 and endorsed by several major professional societies. Since then, there have been a number of randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and consensus conferences. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) published updated practice guidelines in 2016 that encompass pathophysiology, monitoring, diagnosis, and treatment of gastroesophageal hemorrhage in cirrhotic patients. This summary will focus on inpatient management for active gastroesophageal hemorrhage.

Synopsis of Inpatient Management for Esophageal Variceal Hemorrhage: The authors suggest that all VH requires ICU admission with the goal of acute control of bleeding, prevention of early recurrence, and reduction in 6-week mortality. Imaging to rule out portal vein thrombosis and HCC should be considered. Hepatic-Venous Pressure Gradient (HVPG) greater than 20 mm Hg is the strongest predictor of early rebleeding and death. However, catheter measurements of portal pressure are not available at most centers. As with any critically ill patient, stabilization of respiratory status and ensuring hemodynamic stability with volume resuscitation is paramount. RCTs evaluating transfusion goals suggest that a restrictive transfusion goal of HgB 7 g/dL is superior to a liberal goal of 9 g/dL. The authors hypothesize this may be related to lower HVPG observed with lower transfusion thresholds. In terms of treating coagulopathy, RCTs evaluating recombinant VIIa have not shown clear benefit. Correction of INR with FFPs similarly not recommended. No recommendations are made regarding utility of platelet transfusions. Vasoactive drugs should be administered when VH is suspected with the goal of decreasing splanchnic blood flow. Octreotide is the only vasoactive drug available in the United States. RCTs show that antibiotics administered prophylactically decrease infections, recurrent hemorrhage, and death. Ceftriaxone 1 g daily is the drug of choice in the United States and should be given up to a maximum of 7 days. A reasonable strategy is discontinuation of prophylaxis concurrently with discontinuation of vasoactive agents. After stabilization of hemodynamics, patients should proceed to endoscopy no more than 12 hours after presentation. Endoscopic Variceal Ligation (EVL) should be done if signs of active or recent variceal bleeding are found. After EVL, select patients at high risk of rebleeding (Child-Pugh B with active bleeding seen on endoscopy or Child-Pugh C patients) may benefit from TIPS within 72 hours. If TIPS is done, vasoactive agents can be discontinued. Otherwise, vasoactive agents should continue for 2-5 days with subsequent transition to nonselective beta blockers (NSBB) such as nadolol or propranolol. For secondary prophylaxis of esophageal bleeding, combination EVL and NSBB is first-line therapy. If recurrent hemorrhage occurs while on secondary prophylaxis, rescue TIPS is recommended.

Synopsis of Inpatient Management for Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage: Management of Gastric Variceal Hemorrhage is similar to Esophageal Variceal (EV) Hemorrhage and encompasses volume resuscitation, vasoactive drugs, and antibiotics with endoscopy shortly thereafter. Balloon tamponade can be used as a bridge to endoscopy in massive bleeds. In addition to the above, anatomic location of Gastric Varices (GV) affects choice of intervention. GOV1 varices extend from the gastric cardia to the lesser curvature and represent 75% of GV. If these are small, they can be managed with EVL. Otherwise these can be managed with injection of cyanoacrylate glue. GOV2 varices extend from the gastric cardia into the fundus. Isolated GV type 1 varices (IGV1) are located entirely in the fundus and have the highest propensity for bleeding. For these latter two types of “cardio-fundal varices” TIPS is the preferred intervention to control acute bleeding. Data on the efficacy of secondary prophylaxis for GV bleeding is limited. A combination of NSBB, cyanoacrylate injection, or TIPS can be considered. Balloon Occluded Retrograde Transvenous Obliteration (BRTO) can be considered if fundal varices are associated with a large gastrorenal or splenorenal collateral. However, no RCTs have compared BRTO with other strategies. Isolated GV type 2 (IGV2) varices are not localized to the esophageal or gastric cardio-fundal region and are rare in cirrhotic patients but tend to occur in pre-hepatic portal hypertension. Management requires multidisciplinary input from endoscopists, hepatologists, interventional radiologists, and surgeons.

Bottom line: For esophageal variceal bleeding related to cirrhosis: volume resuscitation, antibiotic prophylaxis, and vasoactive agents are mainstays of therapy to stabilize patient for endoscopic intervention within 12 hours. This should be followed by early TIPS within 72 hours in high risk patients.

A similar approach applies to gastric variceal bleeding, but interventional management is dependent on the anatomic location of the varices in question.