User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

Everything We Say & Do: What PFACs reveal about patient experience

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care.

Patient and Family Advisory Councils (PFACs) provide a tool for understanding the patient perspective and are utilized nationwide. These councils, typically consisting of former and current patients and/or their family members, meet on a regular basis to advise provider communities on a wide range of care-related matters. At my institution, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, our PFAC has weighed in on a wide range of issues, such as how to conduct effective nursing rounds and the best methods for supporting patients with disabilities.

Most recently, we have utilized an innovative approach to both understanding the patient experience and capitalizing on the expertise of our PFAC members. Modeled after a program developed at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, we have trained members of our PFAC to interview inpatients at the bedside about their experience. Time-sensitive information is immediately reported back to the nurse manager, who responds with real-time solutions. Oftentimes, problems can be easily resolved using the right communication, or just providing the “listening ear” of someone to whom the patient relates.

In addition, the information is aggregated to provide us with a broad-based perspective of the patient experience at BIDMC. For example, we found that our patients often discuss issues with volunteers that they have not addressed with providers, suggesting they may at times feel more comfortable disclosing concerns to people outside of their medical team.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) also recognizes the central role of the patient’s voice in quality medical care. Through the work of its Patient Experience Committee, SHM has convened a nationwide “virtual” PFAC consisting of leaders of PFACs from medical facilities across the country. Members of the SHM PFAC share questions posed by SHM’s committees with their constituents, and the responses are reported back to the Patient Experience Committee.

What lessons have we learned from the SHM PFAC? Make no assumptions. While some of us have been patients ourselves and all of us interact with patients, our ability to understand the patient perspective is blurred by the lenses of medical training, system constraints, and the pressures of the challenging work that we do.

It is often impossible to predict the response when you question a patient about his or her experience. For example, the first question we asked SHM’s nationwide PFAC was: “What is one thing that a hospitalist could do to improve the patient experience?” The most common response we received was: “What is a hospitalist?” These responses suggest that we (hospitalists) need to redirect our efforts in a way that we had not anticipated, with a focus on clarifying who we are and what we do.

Other, more predictable themes emerged as well. Our patients want consistency and continuity throughout their hospitalization. They value a good bedside manner and want us to engage in sensitivity training. They ask us to work on minimizing errors and ensuring accountability both during hospitalization as well as pre- and post hospitalization.

Ultimately we hope that the SHM PFAC will be utilized by all of SHM’s committees, allowing for the patient experience to be a common thread woven through all SHM initiatives.

Amber Moore, MD, MPH, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor of medicine, Harvard Medical School.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care.

Patient and Family Advisory Councils (PFACs) provide a tool for understanding the patient perspective and are utilized nationwide. These councils, typically consisting of former and current patients and/or their family members, meet on a regular basis to advise provider communities on a wide range of care-related matters. At my institution, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, our PFAC has weighed in on a wide range of issues, such as how to conduct effective nursing rounds and the best methods for supporting patients with disabilities.

Most recently, we have utilized an innovative approach to both understanding the patient experience and capitalizing on the expertise of our PFAC members. Modeled after a program developed at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, we have trained members of our PFAC to interview inpatients at the bedside about their experience. Time-sensitive information is immediately reported back to the nurse manager, who responds with real-time solutions. Oftentimes, problems can be easily resolved using the right communication, or just providing the “listening ear” of someone to whom the patient relates.

In addition, the information is aggregated to provide us with a broad-based perspective of the patient experience at BIDMC. For example, we found that our patients often discuss issues with volunteers that they have not addressed with providers, suggesting they may at times feel more comfortable disclosing concerns to people outside of their medical team.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) also recognizes the central role of the patient’s voice in quality medical care. Through the work of its Patient Experience Committee, SHM has convened a nationwide “virtual” PFAC consisting of leaders of PFACs from medical facilities across the country. Members of the SHM PFAC share questions posed by SHM’s committees with their constituents, and the responses are reported back to the Patient Experience Committee.

What lessons have we learned from the SHM PFAC? Make no assumptions. While some of us have been patients ourselves and all of us interact with patients, our ability to understand the patient perspective is blurred by the lenses of medical training, system constraints, and the pressures of the challenging work that we do.

It is often impossible to predict the response when you question a patient about his or her experience. For example, the first question we asked SHM’s nationwide PFAC was: “What is one thing that a hospitalist could do to improve the patient experience?” The most common response we received was: “What is a hospitalist?” These responses suggest that we (hospitalists) need to redirect our efforts in a way that we had not anticipated, with a focus on clarifying who we are and what we do.

Other, more predictable themes emerged as well. Our patients want consistency and continuity throughout their hospitalization. They value a good bedside manner and want us to engage in sensitivity training. They ask us to work on minimizing errors and ensuring accountability both during hospitalization as well as pre- and post hospitalization.

Ultimately we hope that the SHM PFAC will be utilized by all of SHM’s committees, allowing for the patient experience to be a common thread woven through all SHM initiatives.

Amber Moore, MD, MPH, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor of medicine, Harvard Medical School.

Editor’s note: “Everything We Say and Do” is an informational series developed by the Society of Hospital Medicine’s Patient Experience Committee to provide readers with thoughtful and actionable tactics that have great potential to positively impact patients’ experience of care.

Patient and Family Advisory Councils (PFACs) provide a tool for understanding the patient perspective and are utilized nationwide. These councils, typically consisting of former and current patients and/or their family members, meet on a regular basis to advise provider communities on a wide range of care-related matters. At my institution, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, our PFAC has weighed in on a wide range of issues, such as how to conduct effective nursing rounds and the best methods for supporting patients with disabilities.

Most recently, we have utilized an innovative approach to both understanding the patient experience and capitalizing on the expertise of our PFAC members. Modeled after a program developed at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, we have trained members of our PFAC to interview inpatients at the bedside about their experience. Time-sensitive information is immediately reported back to the nurse manager, who responds with real-time solutions. Oftentimes, problems can be easily resolved using the right communication, or just providing the “listening ear” of someone to whom the patient relates.

In addition, the information is aggregated to provide us with a broad-based perspective of the patient experience at BIDMC. For example, we found that our patients often discuss issues with volunteers that they have not addressed with providers, suggesting they may at times feel more comfortable disclosing concerns to people outside of their medical team.

The Society of Hospital Medicine (SHM) also recognizes the central role of the patient’s voice in quality medical care. Through the work of its Patient Experience Committee, SHM has convened a nationwide “virtual” PFAC consisting of leaders of PFACs from medical facilities across the country. Members of the SHM PFAC share questions posed by SHM’s committees with their constituents, and the responses are reported back to the Patient Experience Committee.

What lessons have we learned from the SHM PFAC? Make no assumptions. While some of us have been patients ourselves and all of us interact with patients, our ability to understand the patient perspective is blurred by the lenses of medical training, system constraints, and the pressures of the challenging work that we do.

It is often impossible to predict the response when you question a patient about his or her experience. For example, the first question we asked SHM’s nationwide PFAC was: “What is one thing that a hospitalist could do to improve the patient experience?” The most common response we received was: “What is a hospitalist?” These responses suggest that we (hospitalists) need to redirect our efforts in a way that we had not anticipated, with a focus on clarifying who we are and what we do.

Other, more predictable themes emerged as well. Our patients want consistency and continuity throughout their hospitalization. They value a good bedside manner and want us to engage in sensitivity training. They ask us to work on minimizing errors and ensuring accountability both during hospitalization as well as pre- and post hospitalization.

Ultimately we hope that the SHM PFAC will be utilized by all of SHM’s committees, allowing for the patient experience to be a common thread woven through all SHM initiatives.

Amber Moore, MD, MPH, is a hospitalist at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, and instructor of medicine, Harvard Medical School.

The beginning of the end

No matter on which side of the aisle you sit, and even if you’d prefer to just sit in your car and check Instagram, the results of the November election were likely a surprise. Speculation abounds by pundits and so-called experts as to what a Trump presidency means for health care in this country. The shape and scope of health care initiatives that a Trump administration will attempt to advance in place of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which has likely met its demise, is unknown at the time of this writing. How Trump’s new initiatives fare in Congress and then get translated into practical changes in health care delivery and financing is even more muddled.

The U.S. medical community has remained largely silent, which is wise given the lack of evidence that would support any rational prediction, but perhaps it’s easier to pronounce judgment from across the pond. The Lancet recently reported the comment of Sophie Harman, PhD, a political scientist at Queen Mary University in London, who told an audience at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine to “ignore the dead cat in the room.”1 I spent 6 months of my residency in the United Kingdom, and this phrase never came up in my travels across the wards, streets, and pubs of the mother country. Apparently, the “dead cat strategy” is a legislative maneuver to distract attention from a party’s political shortcomings by raising a ruckus about a salacious or social hot-button topic. In this case, the dead cat may just be the carcass of Obamacare, exuding the fetor of millions of people losing their health insurance.

The BMJ, another respected U.K. journal, offered the pronouncement by Don Berwick, MD, former administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, that Trump’s election would be “disastrous” for U.S. health care, but not much else.2

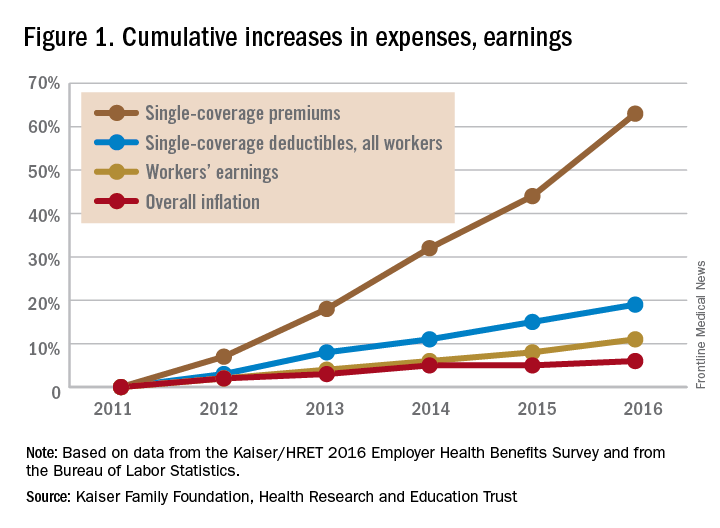

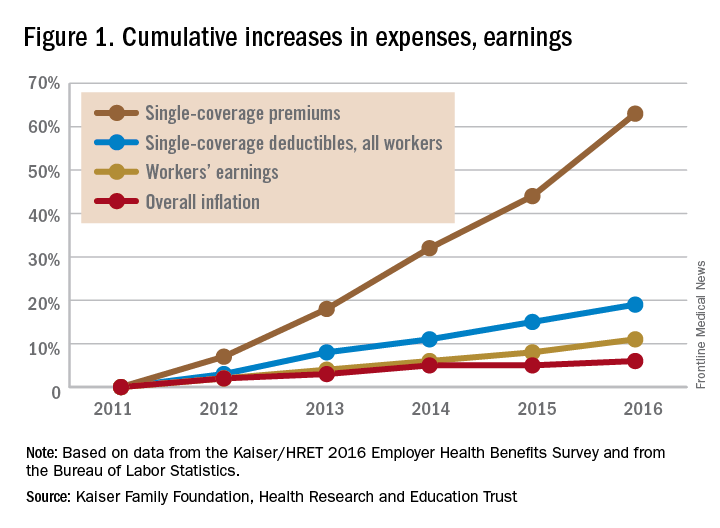

Out-of-pocket health care expenses for patients and families insured under Medicaid and its ACA-mandated expansion decreased to, on average, less than $500 per year; however, 19 states, all with Republican governors, blocked the Medicaid expansion.5 This denied more than 2.5 million people Medicaid coverage in these states; the overwhelming majority of these people remained uninsured. Uninsured people incur significant out-of-pocket costs when they do require health care, and have worse outcomes.6,7 The end of ACA throws Medicaid expansion in any state, with its protections to limit out-of-pocket expenses, into doubt.

Before the ACA expanded Medicaid coverage, patients faced significant wait times and travel costs associated with the low numbers of providers accepting Medicaid’s low reimbursement rate.8 These numbers had begun to improve after the ACA increased primary care physicians’ Medicaid reimbursements to Medicare rates in 2013 and 2014, but only a limited number of states will continue the increases after the end of federal subsidies.

For people who purchased plans on the ACA’s marketplace, out-of-pocket exposure is capped in 2017 at no more than $7,150 for an individual plan and $14,300 for a family plan before marketplace subsidies. Even those who qualified for cost-sharing deductions, with incomes between 100% and 250% of the federal poverty level, had out-of-pocket caps that varied widely depending on plan and state. For example, in 2016 at the $17,000 annual income level, out-of-pocket caps could range from $500 to $2,250.9

Clinician concern

On a provider level, incentives to reduce readmissions and limit health care–associated harm events mandated by the ACA may soon evaporate, throwing into question many quality metrics pursued by health systems. In response, will health system administrators abandon efforts to reduce readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions (HACs)? Or will health systems, despite the lack of a Medicare penalty “stick,” move forward with efforts to reduce readmissions and HACs? There’s no question of what would benefit the pocketbooks of our patients the most – every hospitalization results in significant direct out-of-pocket costs, not to mention lost productivity and income.10

It seems unlikely that a Republican-led government will pursue efforts to decrease out-of-pocket expenses. More likely, new proposals will aim to provide tax benefits to encourage use of health savings accounts (HSAs), continuing the shift of health care to employees.11 HSAs benefit employers, who pay less for the health care costs of employees, but are associated with worsened adherence to recommended treatments for patients.8,12

A 2016 study analyzed health care policies considered by Trump, including the following:

- Full repeal of the ACA.

- Repeal of the ACA plus tax deductions of health insurance premiums.

- Repeal of the ACA plus block grants to states for Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

- Repeal plus promotion of selling health insurance across state lines.

Not surprisingly, all four scenarios resulted in significant increases in out-of-pocket expenses for those in individual insurance plans.13

Although at the time of writing, the “replace” segment of “repeal-and-replace” is not known, Mr. Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.), has given a hint of what he would champion based on his prior legislative proposals. Along with his support of increasing accessibility of armor-piercing bullets, reduced regulations on cigars, and opposition to expanding the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, he proposed H.R. 2300, “Empower Patients First Act.” This would eliminate the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and replace it with flat tax credits based on age, not income, which turns out to offer greater subsidies relative to income for those with higher incomes. A 30-year-old would, on average, face a premium bill of $2,532, along with a potential out-of-pocket liability of $7,000, with only a $1,200 credit to cover this from Mr. Price’s plan.14

In sum

So what’s a conscientious advocate for the physical and financial health of patients to do? Beyond political action, hospitalists need to keep abreast of the effect of changes in health care policy on their patients, as unpleasant as it may be. Do you know what the copays and out-of-pocket costs are for your patient’s (or your own) health care? Knowing how your recommendations for treatment and follow-up affect your patient’s pocketbook will not only help protect their finances, but will also protect their health, as people are less likely to be compliant with treatment if it involves out-of-pocket costs.

And easy as it would be to simply tune out the partisan rancor, stay engaged as a citizen, if for nothing else, the benefit of your patients.

Dr. Chang is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. He is associate clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children's Hospital, Springfield, Mass. Send comments and questions to [email protected].

References

1. Horton R. Offline: Looking forward to Donald Trump. The Lancet. 2016;388[10061]:2726.

2. Page L. What Donald Trump would do with the US healthcare system. BMJ. 2016;353:i2996.

3. Uberoi N, Finegold, K. and Gee, E. Health Insurance Coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. Department of Health and Human Services, ASPE Issue Brief, 2016 March 3.

4. Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, Damico A, Whitmore H, Foster G. Health Benefits In 2016: Family Premiums Rose Modestly, And Offer Rates Remained Stable. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016 Sep. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0951.

5. Ku L, Broaddus M. Public and private health insurance: stacking up the costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:w318-327.

6. Waters H, Steinhardt L, Oliver TR, Burton A, Milner S. The costs of non-insurance in Maryland. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007 Feb;18[1]:139-51.

7. Cheung MR. Lack of health insurance increases all cause and all cancer mortality in adults: an analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14[4]:2259-63.

8. Gillis JZ, Yazdany J, Trupin L, et al. Medicaid and access to care among persons with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57[4]:601-7.

9. Collins SR, Gunja M, Beutel S. How Will the Affordable Care Act’s Cost-Sharing Reductions Affect Consumers’ Out-of-Pocket Costs in 2016? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2016;6:1-17.

10. Leader S, Yang H, DeVincenzo J, Jacobson P, Marcin JP, Murray DL. Time and out-of-pocket costs associated with respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization of infants. Value Health. 2003;6[2]:100-6.

11. Antos J CJ. The House Republicans’ Health Plan. Bethesda, MD: Health Affairs Blog, Project HOPE; 2016 June 22.

12. Fronstin P, Roebuck MC. Health care spending after adopting a full-replacement, high-deductible health plan with a health savings account: a five-year study. EBRI Issue Brief 2013 July:3-15.

13. Saltzman E EC. Donald Trump’s Health Care Reform Proposals: Anticipated Effects on Insurance Coverage, Out-of-Pocket Costs, and the Federal Deficit. The Commonwealth Fund September 2016.

14. Glied SA, Frank RG. Care for the Vulnerable vs. Cash for the Powerful – Trump’s Pick for HHS. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:103-5.

No matter on which side of the aisle you sit, and even if you’d prefer to just sit in your car and check Instagram, the results of the November election were likely a surprise. Speculation abounds by pundits and so-called experts as to what a Trump presidency means for health care in this country. The shape and scope of health care initiatives that a Trump administration will attempt to advance in place of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which has likely met its demise, is unknown at the time of this writing. How Trump’s new initiatives fare in Congress and then get translated into practical changes in health care delivery and financing is even more muddled.

The U.S. medical community has remained largely silent, which is wise given the lack of evidence that would support any rational prediction, but perhaps it’s easier to pronounce judgment from across the pond. The Lancet recently reported the comment of Sophie Harman, PhD, a political scientist at Queen Mary University in London, who told an audience at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine to “ignore the dead cat in the room.”1 I spent 6 months of my residency in the United Kingdom, and this phrase never came up in my travels across the wards, streets, and pubs of the mother country. Apparently, the “dead cat strategy” is a legislative maneuver to distract attention from a party’s political shortcomings by raising a ruckus about a salacious or social hot-button topic. In this case, the dead cat may just be the carcass of Obamacare, exuding the fetor of millions of people losing their health insurance.

The BMJ, another respected U.K. journal, offered the pronouncement by Don Berwick, MD, former administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, that Trump’s election would be “disastrous” for U.S. health care, but not much else.2

Out-of-pocket health care expenses for patients and families insured under Medicaid and its ACA-mandated expansion decreased to, on average, less than $500 per year; however, 19 states, all with Republican governors, blocked the Medicaid expansion.5 This denied more than 2.5 million people Medicaid coverage in these states; the overwhelming majority of these people remained uninsured. Uninsured people incur significant out-of-pocket costs when they do require health care, and have worse outcomes.6,7 The end of ACA throws Medicaid expansion in any state, with its protections to limit out-of-pocket expenses, into doubt.

Before the ACA expanded Medicaid coverage, patients faced significant wait times and travel costs associated with the low numbers of providers accepting Medicaid’s low reimbursement rate.8 These numbers had begun to improve after the ACA increased primary care physicians’ Medicaid reimbursements to Medicare rates in 2013 and 2014, but only a limited number of states will continue the increases after the end of federal subsidies.

For people who purchased plans on the ACA’s marketplace, out-of-pocket exposure is capped in 2017 at no more than $7,150 for an individual plan and $14,300 for a family plan before marketplace subsidies. Even those who qualified for cost-sharing deductions, with incomes between 100% and 250% of the federal poverty level, had out-of-pocket caps that varied widely depending on plan and state. For example, in 2016 at the $17,000 annual income level, out-of-pocket caps could range from $500 to $2,250.9

Clinician concern

On a provider level, incentives to reduce readmissions and limit health care–associated harm events mandated by the ACA may soon evaporate, throwing into question many quality metrics pursued by health systems. In response, will health system administrators abandon efforts to reduce readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions (HACs)? Or will health systems, despite the lack of a Medicare penalty “stick,” move forward with efforts to reduce readmissions and HACs? There’s no question of what would benefit the pocketbooks of our patients the most – every hospitalization results in significant direct out-of-pocket costs, not to mention lost productivity and income.10

It seems unlikely that a Republican-led government will pursue efforts to decrease out-of-pocket expenses. More likely, new proposals will aim to provide tax benefits to encourage use of health savings accounts (HSAs), continuing the shift of health care to employees.11 HSAs benefit employers, who pay less for the health care costs of employees, but are associated with worsened adherence to recommended treatments for patients.8,12

A 2016 study analyzed health care policies considered by Trump, including the following:

- Full repeal of the ACA.

- Repeal of the ACA plus tax deductions of health insurance premiums.

- Repeal of the ACA plus block grants to states for Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

- Repeal plus promotion of selling health insurance across state lines.

Not surprisingly, all four scenarios resulted in significant increases in out-of-pocket expenses for those in individual insurance plans.13

Although at the time of writing, the “replace” segment of “repeal-and-replace” is not known, Mr. Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.), has given a hint of what he would champion based on his prior legislative proposals. Along with his support of increasing accessibility of armor-piercing bullets, reduced regulations on cigars, and opposition to expanding the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, he proposed H.R. 2300, “Empower Patients First Act.” This would eliminate the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and replace it with flat tax credits based on age, not income, which turns out to offer greater subsidies relative to income for those with higher incomes. A 30-year-old would, on average, face a premium bill of $2,532, along with a potential out-of-pocket liability of $7,000, with only a $1,200 credit to cover this from Mr. Price’s plan.14

In sum

So what’s a conscientious advocate for the physical and financial health of patients to do? Beyond political action, hospitalists need to keep abreast of the effect of changes in health care policy on their patients, as unpleasant as it may be. Do you know what the copays and out-of-pocket costs are for your patient’s (or your own) health care? Knowing how your recommendations for treatment and follow-up affect your patient’s pocketbook will not only help protect their finances, but will also protect their health, as people are less likely to be compliant with treatment if it involves out-of-pocket costs.

And easy as it would be to simply tune out the partisan rancor, stay engaged as a citizen, if for nothing else, the benefit of your patients.

Dr. Chang is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. He is associate clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children's Hospital, Springfield, Mass. Send comments and questions to [email protected].

References

1. Horton R. Offline: Looking forward to Donald Trump. The Lancet. 2016;388[10061]:2726.

2. Page L. What Donald Trump would do with the US healthcare system. BMJ. 2016;353:i2996.

3. Uberoi N, Finegold, K. and Gee, E. Health Insurance Coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. Department of Health and Human Services, ASPE Issue Brief, 2016 March 3.

4. Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, Damico A, Whitmore H, Foster G. Health Benefits In 2016: Family Premiums Rose Modestly, And Offer Rates Remained Stable. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016 Sep. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0951.

5. Ku L, Broaddus M. Public and private health insurance: stacking up the costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:w318-327.

6. Waters H, Steinhardt L, Oliver TR, Burton A, Milner S. The costs of non-insurance in Maryland. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007 Feb;18[1]:139-51.

7. Cheung MR. Lack of health insurance increases all cause and all cancer mortality in adults: an analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14[4]:2259-63.

8. Gillis JZ, Yazdany J, Trupin L, et al. Medicaid and access to care among persons with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57[4]:601-7.

9. Collins SR, Gunja M, Beutel S. How Will the Affordable Care Act’s Cost-Sharing Reductions Affect Consumers’ Out-of-Pocket Costs in 2016? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2016;6:1-17.

10. Leader S, Yang H, DeVincenzo J, Jacobson P, Marcin JP, Murray DL. Time and out-of-pocket costs associated with respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization of infants. Value Health. 2003;6[2]:100-6.

11. Antos J CJ. The House Republicans’ Health Plan. Bethesda, MD: Health Affairs Blog, Project HOPE; 2016 June 22.

12. Fronstin P, Roebuck MC. Health care spending after adopting a full-replacement, high-deductible health plan with a health savings account: a five-year study. EBRI Issue Brief 2013 July:3-15.

13. Saltzman E EC. Donald Trump’s Health Care Reform Proposals: Anticipated Effects on Insurance Coverage, Out-of-Pocket Costs, and the Federal Deficit. The Commonwealth Fund September 2016.

14. Glied SA, Frank RG. Care for the Vulnerable vs. Cash for the Powerful – Trump’s Pick for HHS. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:103-5.

No matter on which side of the aisle you sit, and even if you’d prefer to just sit in your car and check Instagram, the results of the November election were likely a surprise. Speculation abounds by pundits and so-called experts as to what a Trump presidency means for health care in this country. The shape and scope of health care initiatives that a Trump administration will attempt to advance in place of the Affordable Care Act (ACA), which has likely met its demise, is unknown at the time of this writing. How Trump’s new initiatives fare in Congress and then get translated into practical changes in health care delivery and financing is even more muddled.

The U.S. medical community has remained largely silent, which is wise given the lack of evidence that would support any rational prediction, but perhaps it’s easier to pronounce judgment from across the pond. The Lancet recently reported the comment of Sophie Harman, PhD, a political scientist at Queen Mary University in London, who told an audience at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine to “ignore the dead cat in the room.”1 I spent 6 months of my residency in the United Kingdom, and this phrase never came up in my travels across the wards, streets, and pubs of the mother country. Apparently, the “dead cat strategy” is a legislative maneuver to distract attention from a party’s political shortcomings by raising a ruckus about a salacious or social hot-button topic. In this case, the dead cat may just be the carcass of Obamacare, exuding the fetor of millions of people losing their health insurance.

The BMJ, another respected U.K. journal, offered the pronouncement by Don Berwick, MD, former administrator of the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, that Trump’s election would be “disastrous” for U.S. health care, but not much else.2

Out-of-pocket health care expenses for patients and families insured under Medicaid and its ACA-mandated expansion decreased to, on average, less than $500 per year; however, 19 states, all with Republican governors, blocked the Medicaid expansion.5 This denied more than 2.5 million people Medicaid coverage in these states; the overwhelming majority of these people remained uninsured. Uninsured people incur significant out-of-pocket costs when they do require health care, and have worse outcomes.6,7 The end of ACA throws Medicaid expansion in any state, with its protections to limit out-of-pocket expenses, into doubt.

Before the ACA expanded Medicaid coverage, patients faced significant wait times and travel costs associated with the low numbers of providers accepting Medicaid’s low reimbursement rate.8 These numbers had begun to improve after the ACA increased primary care physicians’ Medicaid reimbursements to Medicare rates in 2013 and 2014, but only a limited number of states will continue the increases after the end of federal subsidies.

For people who purchased plans on the ACA’s marketplace, out-of-pocket exposure is capped in 2017 at no more than $7,150 for an individual plan and $14,300 for a family plan before marketplace subsidies. Even those who qualified for cost-sharing deductions, with incomes between 100% and 250% of the federal poverty level, had out-of-pocket caps that varied widely depending on plan and state. For example, in 2016 at the $17,000 annual income level, out-of-pocket caps could range from $500 to $2,250.9

Clinician concern

On a provider level, incentives to reduce readmissions and limit health care–associated harm events mandated by the ACA may soon evaporate, throwing into question many quality metrics pursued by health systems. In response, will health system administrators abandon efforts to reduce readmissions and hospital-acquired conditions (HACs)? Or will health systems, despite the lack of a Medicare penalty “stick,” move forward with efforts to reduce readmissions and HACs? There’s no question of what would benefit the pocketbooks of our patients the most – every hospitalization results in significant direct out-of-pocket costs, not to mention lost productivity and income.10

It seems unlikely that a Republican-led government will pursue efforts to decrease out-of-pocket expenses. More likely, new proposals will aim to provide tax benefits to encourage use of health savings accounts (HSAs), continuing the shift of health care to employees.11 HSAs benefit employers, who pay less for the health care costs of employees, but are associated with worsened adherence to recommended treatments for patients.8,12

A 2016 study analyzed health care policies considered by Trump, including the following:

- Full repeal of the ACA.

- Repeal of the ACA plus tax deductions of health insurance premiums.

- Repeal of the ACA plus block grants to states for Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP).

- Repeal plus promotion of selling health insurance across state lines.

Not surprisingly, all four scenarios resulted in significant increases in out-of-pocket expenses for those in individual insurance plans.13

Although at the time of writing, the “replace” segment of “repeal-and-replace” is not known, Mr. Trump’s nominee for Secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS), Rep. Tom Price (R-Ga.), has given a hint of what he would champion based on his prior legislative proposals. Along with his support of increasing accessibility of armor-piercing bullets, reduced regulations on cigars, and opposition to expanding the State Children’s Health Insurance Program, he proposed H.R. 2300, “Empower Patients First Act.” This would eliminate the ACA’s Medicaid expansion and replace it with flat tax credits based on age, not income, which turns out to offer greater subsidies relative to income for those with higher incomes. A 30-year-old would, on average, face a premium bill of $2,532, along with a potential out-of-pocket liability of $7,000, with only a $1,200 credit to cover this from Mr. Price’s plan.14

In sum

So what’s a conscientious advocate for the physical and financial health of patients to do? Beyond political action, hospitalists need to keep abreast of the effect of changes in health care policy on their patients, as unpleasant as it may be. Do you know what the copays and out-of-pocket costs are for your patient’s (or your own) health care? Knowing how your recommendations for treatment and follow-up affect your patient’s pocketbook will not only help protect their finances, but will also protect their health, as people are less likely to be compliant with treatment if it involves out-of-pocket costs.

And easy as it would be to simply tune out the partisan rancor, stay engaged as a citizen, if for nothing else, the benefit of your patients.

Dr. Chang is pediatric editor of The Hospitalist. He is associate clinical professor of pediatrics at the University of Massachusetts, Worcester, and chief of pediatric hospital medicine at Baystate Children's Hospital, Springfield, Mass. Send comments and questions to [email protected].

References

1. Horton R. Offline: Looking forward to Donald Trump. The Lancet. 2016;388[10061]:2726.

2. Page L. What Donald Trump would do with the US healthcare system. BMJ. 2016;353:i2996.

3. Uberoi N, Finegold, K. and Gee, E. Health Insurance Coverage and the Affordable Care Act, 2010-2016. Department of Health and Human Services, ASPE Issue Brief, 2016 March 3.

4. Claxton G, Rae M, Long M, Damico A, Whitmore H, Foster G. Health Benefits In 2016: Family Premiums Rose Modestly, And Offer Rates Remained Stable. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016 Sep. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0951.

5. Ku L, Broaddus M. Public and private health insurance: stacking up the costs. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27:w318-327.

6. Waters H, Steinhardt L, Oliver TR, Burton A, Milner S. The costs of non-insurance in Maryland. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2007 Feb;18[1]:139-51.

7. Cheung MR. Lack of health insurance increases all cause and all cancer mortality in adults: an analysis of National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) data. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2013;14[4]:2259-63.

8. Gillis JZ, Yazdany J, Trupin L, et al. Medicaid and access to care among persons with systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2007;57[4]:601-7.

9. Collins SR, Gunja M, Beutel S. How Will the Affordable Care Act’s Cost-Sharing Reductions Affect Consumers’ Out-of-Pocket Costs in 2016? Issue Brief (Commonw Fund) 2016;6:1-17.

10. Leader S, Yang H, DeVincenzo J, Jacobson P, Marcin JP, Murray DL. Time and out-of-pocket costs associated with respiratory syncytial virus hospitalization of infants. Value Health. 2003;6[2]:100-6.

11. Antos J CJ. The House Republicans’ Health Plan. Bethesda, MD: Health Affairs Blog, Project HOPE; 2016 June 22.

12. Fronstin P, Roebuck MC. Health care spending after adopting a full-replacement, high-deductible health plan with a health savings account: a five-year study. EBRI Issue Brief 2013 July:3-15.

13. Saltzman E EC. Donald Trump’s Health Care Reform Proposals: Anticipated Effects on Insurance Coverage, Out-of-Pocket Costs, and the Federal Deficit. The Commonwealth Fund September 2016.

14. Glied SA, Frank RG. Care for the Vulnerable vs. Cash for the Powerful – Trump’s Pick for HHS. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:103-5.

Revisiting citizenship bonus and surge capacity

I devoted an entire column to the idea of a citizenship bonus in November 2011. At that time I expressed some ambivalence about its effectiveness. Since then I’ve become disenchanted and think it may do more harm than good.

SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, based on 2015 data, shows that 46% of Hospital Medicine Groups (HMGs) connect some portion of bonus dollars to a provider’s citizenship.1 This is a relatively new phenomenon in the last 5 years or so. My anecdotal experience is that it isn’t limited to hospitalists; it is pretty common for doctors in any specialty who are employed by a hospital or other large organization.

HMGs vary in their definitions of what constitutes citizenship, but usually include things like committee participation, lectures, grand rounds presentations, community talks, research publications.

Our hospitalist group at my hospital has well-defined criteria that require attendance at more than 75% of meetings as a “light switch” (pays nothing itself, but “turns on” availability to citizenship bonus). Bonus dollars are paid for success in any one of several activities, such as making an in-person visit to two PCP offices or completing a meaningful project related to practice operations or clinical care.

I’ve been a supporter of a citizenship bonus for a long time, but two things have made me ambivalent or even opposed to it. The first is a book by Daniel Pink titled Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. It’s a short and very thought-provoking book summarizing research that suggests the effect of providing external rewards like compensation is to “…extinguish intrinsic motivation, diminish performance, crush creativity, and crowd out good behavior.”

The second reason for my ambivalence is my experience working with a lot of HMGs around the country. Those that have a citizenship bonus don’t seem to realize improved operations, more engaged doctors, or lower turnover, and so on. In fact, my experience is that the bonus tends to do exactly what Pink says – steer individuals and the group as a whole away from what is desired.

I’m not ready to say a citizenship bonus is always a bad idea. But it sure seems like it works out badly for many or most groups.

But if you do have a citizenship bonus, then don’t make the mistake of tying it to very basic expectations of the job, like attending group meetings or completing chart documentation on time. Doing those things should never be seen as a reason for a bonus.

Jeopardy (‘surge’) staffing: Not catching on?

As I write, influenza has swept through our region, and my hospital – like most along the west coast – is experiencing incredibly high volumes. I enter the building through a patient care unit that has been mothballed for several years, but today people from building maintenance were busy getting it ready for patients. The hospital is offering various incentives for patient care staff to work extra shifts to manage this volume surge, and our hospitalists have days with encounters near or at our highest-ever level. So surge capacity is once again on my mind.

But if every hospitalist in the group went from, say, 156 to 190 shifts annually, the practice might be able to staff every day with an additional provider without adding staff or spending more money. And a doc’s average day would be less busy, which for some people (okay, not very many) would be a worthwhile trade-off. I realize this is a tough sell and to many people it sounds crazy.

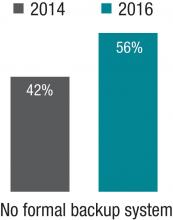

The 2014 SOHM showed 42% of HMGs had “no formal backup system,” and this had climbed to 58% in the 2016 Report. I don’t know if jeopardy or surge backup systems are really becoming less common, but it seems pretty clear they aren’t becoming more common. So it’s worth thinking about whether there is a practical way to remove inhibitors of surge capacity.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Endnotes

1. Note that this is down from 2014, when 64% of groups reported having a citizenship element in their bonus. But I’m skeptical this is a real trend of decreasing popularity and suspect the drop is mostly explained by a much larger portion of respondents in this particular survey coming from hospitalist management companies which I think much less often have a citizenship bonus.

I devoted an entire column to the idea of a citizenship bonus in November 2011. At that time I expressed some ambivalence about its effectiveness. Since then I’ve become disenchanted and think it may do more harm than good.

SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, based on 2015 data, shows that 46% of Hospital Medicine Groups (HMGs) connect some portion of bonus dollars to a provider’s citizenship.1 This is a relatively new phenomenon in the last 5 years or so. My anecdotal experience is that it isn’t limited to hospitalists; it is pretty common for doctors in any specialty who are employed by a hospital or other large organization.

HMGs vary in their definitions of what constitutes citizenship, but usually include things like committee participation, lectures, grand rounds presentations, community talks, research publications.

Our hospitalist group at my hospital has well-defined criteria that require attendance at more than 75% of meetings as a “light switch” (pays nothing itself, but “turns on” availability to citizenship bonus). Bonus dollars are paid for success in any one of several activities, such as making an in-person visit to two PCP offices or completing a meaningful project related to practice operations or clinical care.

I’ve been a supporter of a citizenship bonus for a long time, but two things have made me ambivalent or even opposed to it. The first is a book by Daniel Pink titled Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. It’s a short and very thought-provoking book summarizing research that suggests the effect of providing external rewards like compensation is to “…extinguish intrinsic motivation, diminish performance, crush creativity, and crowd out good behavior.”

The second reason for my ambivalence is my experience working with a lot of HMGs around the country. Those that have a citizenship bonus don’t seem to realize improved operations, more engaged doctors, or lower turnover, and so on. In fact, my experience is that the bonus tends to do exactly what Pink says – steer individuals and the group as a whole away from what is desired.

I’m not ready to say a citizenship bonus is always a bad idea. But it sure seems like it works out badly for many or most groups.

But if you do have a citizenship bonus, then don’t make the mistake of tying it to very basic expectations of the job, like attending group meetings or completing chart documentation on time. Doing those things should never be seen as a reason for a bonus.

Jeopardy (‘surge’) staffing: Not catching on?

As I write, influenza has swept through our region, and my hospital – like most along the west coast – is experiencing incredibly high volumes. I enter the building through a patient care unit that has been mothballed for several years, but today people from building maintenance were busy getting it ready for patients. The hospital is offering various incentives for patient care staff to work extra shifts to manage this volume surge, and our hospitalists have days with encounters near or at our highest-ever level. So surge capacity is once again on my mind.

But if every hospitalist in the group went from, say, 156 to 190 shifts annually, the practice might be able to staff every day with an additional provider without adding staff or spending more money. And a doc’s average day would be less busy, which for some people (okay, not very many) would be a worthwhile trade-off. I realize this is a tough sell and to many people it sounds crazy.

The 2014 SOHM showed 42% of HMGs had “no formal backup system,” and this had climbed to 58% in the 2016 Report. I don’t know if jeopardy or surge backup systems are really becoming less common, but it seems pretty clear they aren’t becoming more common. So it’s worth thinking about whether there is a practical way to remove inhibitors of surge capacity.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Endnotes

1. Note that this is down from 2014, when 64% of groups reported having a citizenship element in their bonus. But I’m skeptical this is a real trend of decreasing popularity and suspect the drop is mostly explained by a much larger portion of respondents in this particular survey coming from hospitalist management companies which I think much less often have a citizenship bonus.

I devoted an entire column to the idea of a citizenship bonus in November 2011. At that time I expressed some ambivalence about its effectiveness. Since then I’ve become disenchanted and think it may do more harm than good.

SHM’s 2016 State of Hospital Medicine (SOHM) Report, based on 2015 data, shows that 46% of Hospital Medicine Groups (HMGs) connect some portion of bonus dollars to a provider’s citizenship.1 This is a relatively new phenomenon in the last 5 years or so. My anecdotal experience is that it isn’t limited to hospitalists; it is pretty common for doctors in any specialty who are employed by a hospital or other large organization.

HMGs vary in their definitions of what constitutes citizenship, but usually include things like committee participation, lectures, grand rounds presentations, community talks, research publications.

Our hospitalist group at my hospital has well-defined criteria that require attendance at more than 75% of meetings as a “light switch” (pays nothing itself, but “turns on” availability to citizenship bonus). Bonus dollars are paid for success in any one of several activities, such as making an in-person visit to two PCP offices or completing a meaningful project related to practice operations or clinical care.

I’ve been a supporter of a citizenship bonus for a long time, but two things have made me ambivalent or even opposed to it. The first is a book by Daniel Pink titled Drive: The Surprising Truth About What Motivates Us. It’s a short and very thought-provoking book summarizing research that suggests the effect of providing external rewards like compensation is to “…extinguish intrinsic motivation, diminish performance, crush creativity, and crowd out good behavior.”

The second reason for my ambivalence is my experience working with a lot of HMGs around the country. Those that have a citizenship bonus don’t seem to realize improved operations, more engaged doctors, or lower turnover, and so on. In fact, my experience is that the bonus tends to do exactly what Pink says – steer individuals and the group as a whole away from what is desired.

I’m not ready to say a citizenship bonus is always a bad idea. But it sure seems like it works out badly for many or most groups.

But if you do have a citizenship bonus, then don’t make the mistake of tying it to very basic expectations of the job, like attending group meetings or completing chart documentation on time. Doing those things should never be seen as a reason for a bonus.

Jeopardy (‘surge’) staffing: Not catching on?

As I write, influenza has swept through our region, and my hospital – like most along the west coast – is experiencing incredibly high volumes. I enter the building through a patient care unit that has been mothballed for several years, but today people from building maintenance were busy getting it ready for patients. The hospital is offering various incentives for patient care staff to work extra shifts to manage this volume surge, and our hospitalists have days with encounters near or at our highest-ever level. So surge capacity is once again on my mind.

But if every hospitalist in the group went from, say, 156 to 190 shifts annually, the practice might be able to staff every day with an additional provider without adding staff or spending more money. And a doc’s average day would be less busy, which for some people (okay, not very many) would be a worthwhile trade-off. I realize this is a tough sell and to many people it sounds crazy.

The 2014 SOHM showed 42% of HMGs had “no formal backup system,” and this had climbed to 58% in the 2016 Report. I don’t know if jeopardy or surge backup systems are really becoming less common, but it seems pretty clear they aren’t becoming more common. So it’s worth thinking about whether there is a practical way to remove inhibitors of surge capacity.

Dr. Nelson has been a practicing hospitalist since 1988. He is cofounder and past president of SHM, and principal in Nelson Flores Hospital Medicine Consultants. He is course co-director for SHM’s “Best Practices in Managing a Hospital Medicine Program” course. Write to him at [email protected].

Endnotes

1. Note that this is down from 2014, when 64% of groups reported having a citizenship element in their bonus. But I’m skeptical this is a real trend of decreasing popularity and suspect the drop is mostly explained by a much larger portion of respondents in this particular survey coming from hospitalist management companies which I think much less often have a citizenship bonus.

Sneak Peek: Journal of Hospital Medicine

Background: Communication among team members within hospitals is typically fragmented. Bedside interdisciplinary rounds (IDR) have the potential to improve communication and outcomes through enhanced structure and patient engagement.

Objective: To decrease length of stay (LOS) and complications through the transformation of daily IDR to a bedside model.

Setting: Two geographic areas of a medical unit using a clinical microsystem structure.

Patients: 2,005 hospitalizations over a 12-month period.

Interventions: A bedside model (mobile interdisciplinary care rounds [MICRO]) was developed. MICRO featured a defined structure, scripting, patient engagement, and a patient safety checklist.

Measurements: The primary outcomes were clinical deterioration (composite of death, transfer to a higher level of care, or development of a hospital-acquired complication) and length of stay (LOS). Patient safety culture and perceptions of bedside interdisciplinary rounding were assessed pre- and post-implementation.

Results: There was no difference in LOS (6.6 vs. 7.0 days, P = .17, for the MICRO and control groups, respectively) or clinical deterioration (7.7% vs. 9.3%, P = .46). LOS was reduced for patients transferred to the study unit (10.4 vs. 14.0 days, P = .02, for the MICRO and control groups, respectively). Nurses and hospitalists gave significantly higher scores for patient safety climate and the efficiency of rounds after implementation of the MICRO model.

Limitations: The trial was performed at a single hospital.

Conclusions: Bedside IDR did not reduce overall LOS or clinical deterioration. Future studies should examine whether comprehensive transformation of medical units, including co-leadership, geographic cohorting of teams, and bedside interdisciplinary rounding, improves clinical outcomes compared to units without these features.

Also in the Journal of Hospital Medicine …

Standardized Attending Rounds to Improve the Patient Experience: A Pragmatic Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

Authors: Bradley Monash, MD, Nader Najafi, MD, Michelle Mourad, MD, Alvin Rajkomar, MD, Sumant R. Ranji, MD, Margaret C. Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, Marcia Glass, MD, Dimiter Milev, MPH, Yile Ding, MD, Andy Shen, BA, Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, FACP, SFHM, James D Harrison, MPH, PhD

All Together Now: Impact of a Regionalization and Bedside Rounding Initiative on the Efficiency and Inclusiveness of Clinical Rounds

Authors: Kristin T. L. Huang, MD, Jacquelyn Minahan, Patricia Brita-Rossi, RN, MSN, MBA, Patricia Aylward, RN, MSN, Joel T. Katz, MD, SFHM, Christopher Roy, MD, Jeffrey L. Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, Robert Boxer, MD, PhD

Family Report Compared to Clinician-Documented Diagnoses for Psychiatric Conditions Among Hospitalized Children

Authors: Stephanie K. Doupnik, MD, Chris Feudtner, MD, PhD, MPH, Steven C. Marcus, PhD

Perceived Safety and Value of Inpatient ‘Very Important Person’ Services

Authors: Joshua Allen-Dicker, MD, MPH, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, Shoshana J. Herzig, MD, MPH

A Time and Motion Study of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians Obtaining Admission Medication Histories

Authors: Caroline B. Nguyen, PharmD, BCPS, Rita Shane, PharmD, FASHP, FCSHP, Douglas S. Bell, MD, PhD, Galen Cook-Wiens, MS, Joshua M. Pevnick, MD, MSHS

Background: Communication among team members within hospitals is typically fragmented. Bedside interdisciplinary rounds (IDR) have the potential to improve communication and outcomes through enhanced structure and patient engagement.

Objective: To decrease length of stay (LOS) and complications through the transformation of daily IDR to a bedside model.

Setting: Two geographic areas of a medical unit using a clinical microsystem structure.

Patients: 2,005 hospitalizations over a 12-month period.

Interventions: A bedside model (mobile interdisciplinary care rounds [MICRO]) was developed. MICRO featured a defined structure, scripting, patient engagement, and a patient safety checklist.

Measurements: The primary outcomes were clinical deterioration (composite of death, transfer to a higher level of care, or development of a hospital-acquired complication) and length of stay (LOS). Patient safety culture and perceptions of bedside interdisciplinary rounding were assessed pre- and post-implementation.

Results: There was no difference in LOS (6.6 vs. 7.0 days, P = .17, for the MICRO and control groups, respectively) or clinical deterioration (7.7% vs. 9.3%, P = .46). LOS was reduced for patients transferred to the study unit (10.4 vs. 14.0 days, P = .02, for the MICRO and control groups, respectively). Nurses and hospitalists gave significantly higher scores for patient safety climate and the efficiency of rounds after implementation of the MICRO model.

Limitations: The trial was performed at a single hospital.

Conclusions: Bedside IDR did not reduce overall LOS or clinical deterioration. Future studies should examine whether comprehensive transformation of medical units, including co-leadership, geographic cohorting of teams, and bedside interdisciplinary rounding, improves clinical outcomes compared to units without these features.

Also in the Journal of Hospital Medicine …

Standardized Attending Rounds to Improve the Patient Experience: A Pragmatic Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

Authors: Bradley Monash, MD, Nader Najafi, MD, Michelle Mourad, MD, Alvin Rajkomar, MD, Sumant R. Ranji, MD, Margaret C. Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, Marcia Glass, MD, Dimiter Milev, MPH, Yile Ding, MD, Andy Shen, BA, Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, FACP, SFHM, James D Harrison, MPH, PhD

All Together Now: Impact of a Regionalization and Bedside Rounding Initiative on the Efficiency and Inclusiveness of Clinical Rounds

Authors: Kristin T. L. Huang, MD, Jacquelyn Minahan, Patricia Brita-Rossi, RN, MSN, MBA, Patricia Aylward, RN, MSN, Joel T. Katz, MD, SFHM, Christopher Roy, MD, Jeffrey L. Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, Robert Boxer, MD, PhD

Family Report Compared to Clinician-Documented Diagnoses for Psychiatric Conditions Among Hospitalized Children

Authors: Stephanie K. Doupnik, MD, Chris Feudtner, MD, PhD, MPH, Steven C. Marcus, PhD

Perceived Safety and Value of Inpatient ‘Very Important Person’ Services

Authors: Joshua Allen-Dicker, MD, MPH, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, Shoshana J. Herzig, MD, MPH

A Time and Motion Study of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians Obtaining Admission Medication Histories

Authors: Caroline B. Nguyen, PharmD, BCPS, Rita Shane, PharmD, FASHP, FCSHP, Douglas S. Bell, MD, PhD, Galen Cook-Wiens, MS, Joshua M. Pevnick, MD, MSHS

Background: Communication among team members within hospitals is typically fragmented. Bedside interdisciplinary rounds (IDR) have the potential to improve communication and outcomes through enhanced structure and patient engagement.

Objective: To decrease length of stay (LOS) and complications through the transformation of daily IDR to a bedside model.

Setting: Two geographic areas of a medical unit using a clinical microsystem structure.

Patients: 2,005 hospitalizations over a 12-month period.

Interventions: A bedside model (mobile interdisciplinary care rounds [MICRO]) was developed. MICRO featured a defined structure, scripting, patient engagement, and a patient safety checklist.

Measurements: The primary outcomes were clinical deterioration (composite of death, transfer to a higher level of care, or development of a hospital-acquired complication) and length of stay (LOS). Patient safety culture and perceptions of bedside interdisciplinary rounding were assessed pre- and post-implementation.

Results: There was no difference in LOS (6.6 vs. 7.0 days, P = .17, for the MICRO and control groups, respectively) or clinical deterioration (7.7% vs. 9.3%, P = .46). LOS was reduced for patients transferred to the study unit (10.4 vs. 14.0 days, P = .02, for the MICRO and control groups, respectively). Nurses and hospitalists gave significantly higher scores for patient safety climate and the efficiency of rounds after implementation of the MICRO model.

Limitations: The trial was performed at a single hospital.

Conclusions: Bedside IDR did not reduce overall LOS or clinical deterioration. Future studies should examine whether comprehensive transformation of medical units, including co-leadership, geographic cohorting of teams, and bedside interdisciplinary rounding, improves clinical outcomes compared to units without these features.

Also in the Journal of Hospital Medicine …

Standardized Attending Rounds to Improve the Patient Experience: A Pragmatic Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial

Authors: Bradley Monash, MD, Nader Najafi, MD, Michelle Mourad, MD, Alvin Rajkomar, MD, Sumant R. Ranji, MD, Margaret C. Fang, MD, MPH, FHM, Marcia Glass, MD, Dimiter Milev, MPH, Yile Ding, MD, Andy Shen, BA, Bradley A. Sharpe, MD, FACP, SFHM, James D Harrison, MPH, PhD

All Together Now: Impact of a Regionalization and Bedside Rounding Initiative on the Efficiency and Inclusiveness of Clinical Rounds

Authors: Kristin T. L. Huang, MD, Jacquelyn Minahan, Patricia Brita-Rossi, RN, MSN, MBA, Patricia Aylward, RN, MSN, Joel T. Katz, MD, SFHM, Christopher Roy, MD, Jeffrey L. Schnipper, MD, MPH, FHM, Robert Boxer, MD, PhD

Family Report Compared to Clinician-Documented Diagnoses for Psychiatric Conditions Among Hospitalized Children

Authors: Stephanie K. Doupnik, MD, Chris Feudtner, MD, PhD, MPH, Steven C. Marcus, PhD

Perceived Safety and Value of Inpatient ‘Very Important Person’ Services

Authors: Joshua Allen-Dicker, MD, MPH, Andrew Auerbach, MD, MPH, SFHM, Shoshana J. Herzig, MD, MPH

A Time and Motion Study of Pharmacists and Pharmacy Technicians Obtaining Admission Medication Histories

Authors: Caroline B. Nguyen, PharmD, BCPS, Rita Shane, PharmD, FASHP, FCSHP, Douglas S. Bell, MD, PhD, Galen Cook-Wiens, MS, Joshua M. Pevnick, MD, MSHS

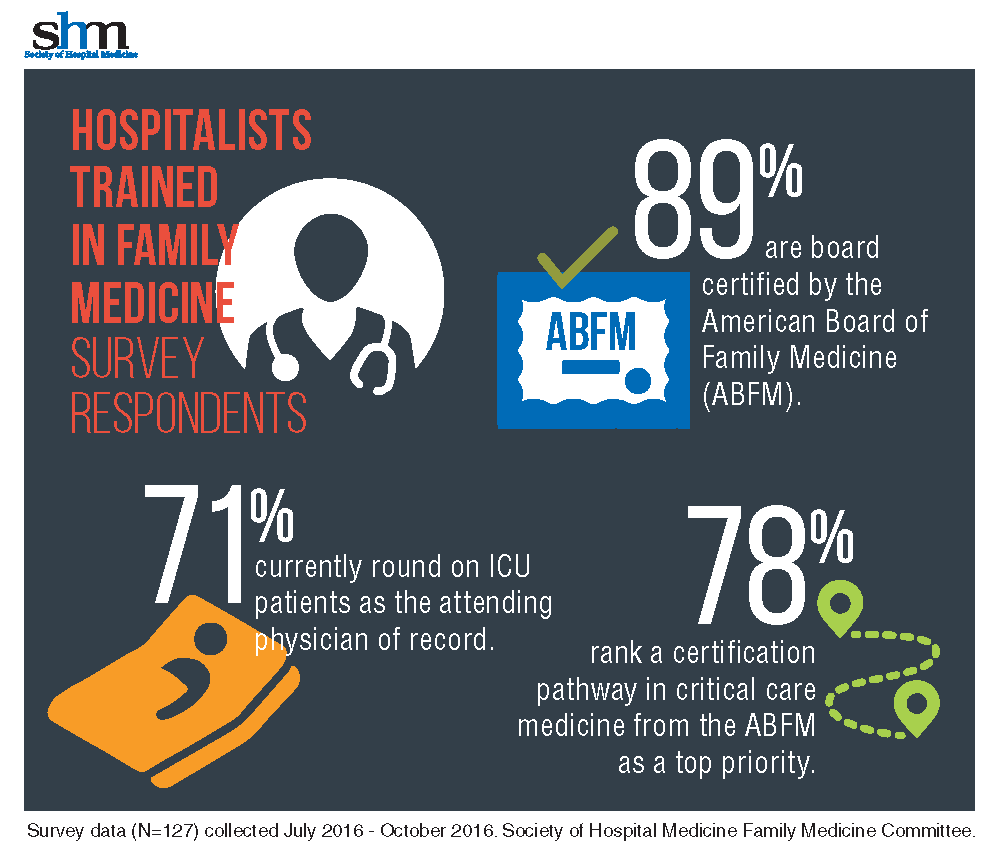

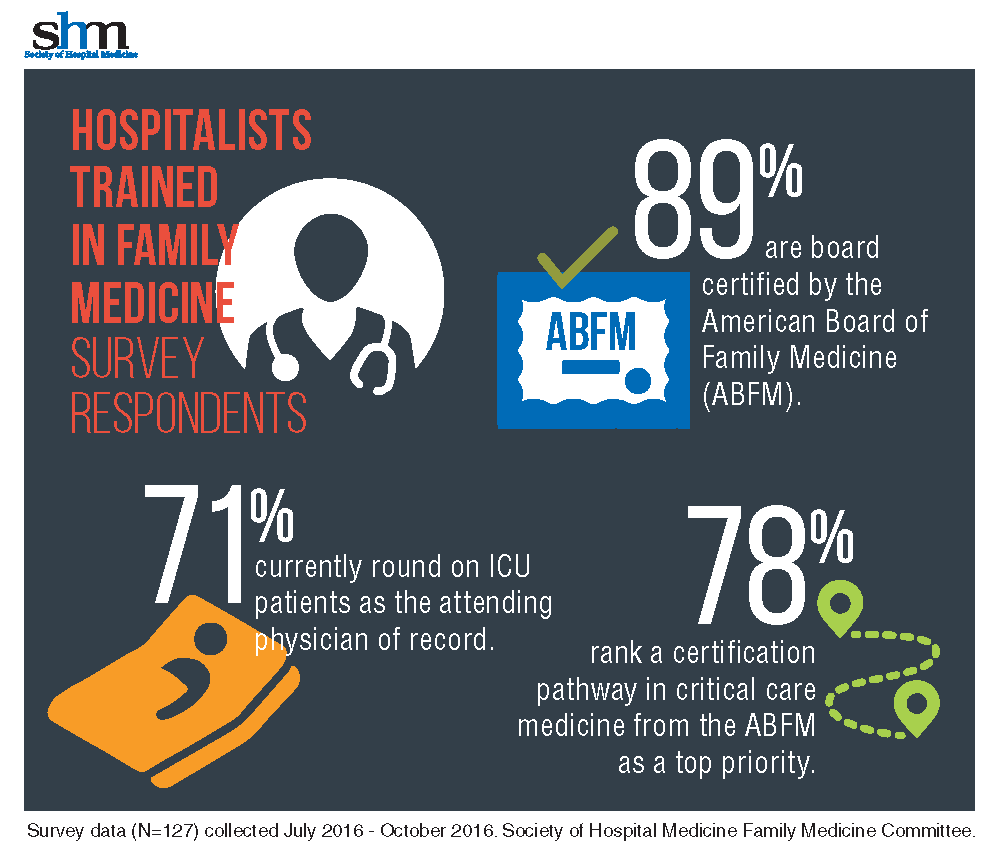

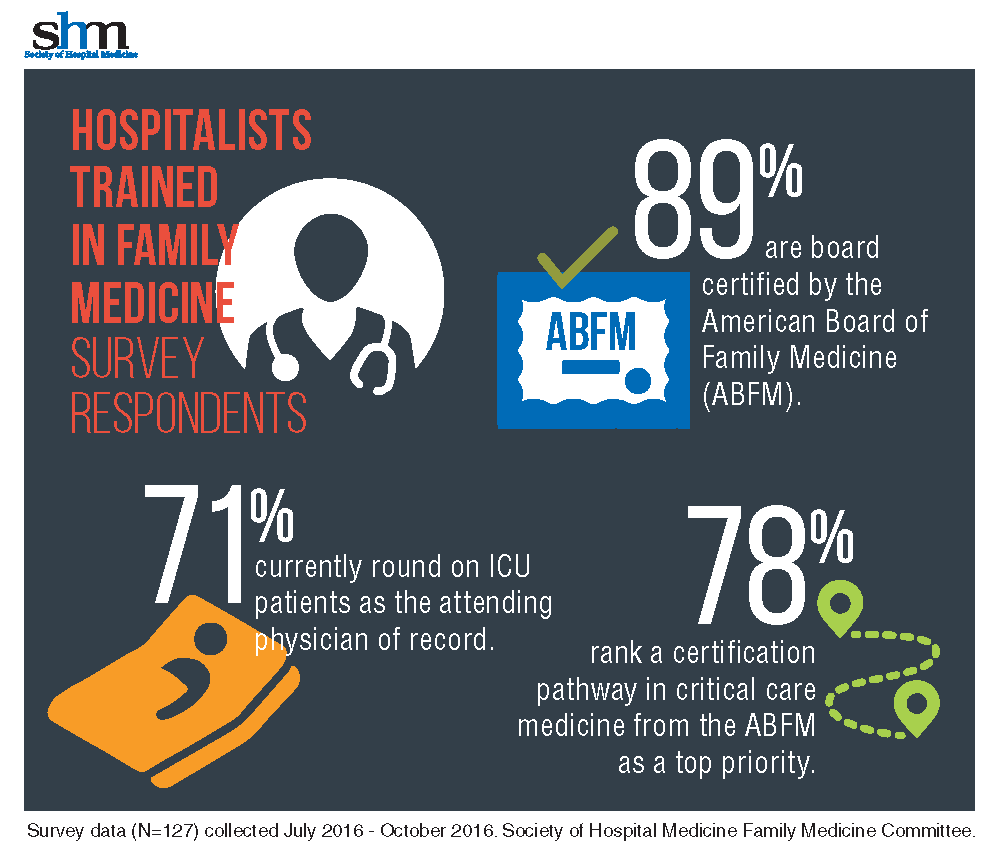

Hospitalists trained in family medicine seek critical care training pathway

A nationwide shortage of intensivists has more hospitalists stepping into the critical care arena, but not all with the level of preparation and comfort of David Aymond, MD, a Louisiana-based hospitalist trained in family medicine (HTFM).

Dr. Aymond gained his ICU experience in a fellowship with the University of Alabama, where hospitalists also “were responsible for ICU patients,” he said. Years later, as an employee of both small and large hospitals with busy ICU services, and a faculty member for a family medicine residency with a busy ICU, Dr. Aymond moves seamlessly between roles.

“It was eye-opening to learn how many [HTFM] are not only caring for patients in the ICU, but also are requesting additional training,” said Dr. Aymond, a member of the SHM Family Medicine Committee. “A critical care pathway would provide them with a level of expertise already available to physicians in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and surgery.”

With 71% of HTFM reporting that they round on ICU as the attending physician, the strong endorsement (78%) for critical care certification is not surprising.

“I am currently practicing as a full time intensivist and take consults from other providers, yet I only have a certificate from fellowship, no formal board certification in critical care,” noted a survey respondent.

Other participants stated, “it makes perfect sense to have a pathway to critical care if both family medicine and internal medicine coexist as hospitalists,” that certification is “imperative at rural and underserved hospitals,” and also “helpful for those …who work in larger hospitals and take care of critically ill patients.” More than half of those surveyed want the Family Medicine Committee to work with ABFM to create the pathway.

The majority (87%) of the HTFM survey respondents are certified by the ABFM, and 8% have attained Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine. Common pathways for additional credentialing include SHM’s Fellow of Hospital Medicine program (38%), a fellowship in hospital medicine (19%), and certification in hospice and palliative care (15%). More than 38% reported “other qualifications,” such as years of work experience, certification by the American Osteopathic Board of Family Physicians, and prior training in internal medicine.

The survey also found that certification differences in internal medicine and family medicine hospitalists, which may have posed employment obstacles in the past for HTFM, are not as much of an issue.

“The critical care pathway is the bigger concern,” Dr. Aymond said.

SHM’s Family Medicine Committee will be working on a proposal to ABFM to create the training pathway in the coming months. Dr. Aymond wants intensivists to know that this not an attempt to encroach on their professional domain, “but an opportunity to fill the existing professional gap.

Family medicine physicians are already providing critical care services, so a pathway to obtain formal training makes sense,” he adds. “If a family medicine doc completes the fellowship and takes it back to a residency program [the residents] will be more prepared for their potential careers in hospital and ICU medicine and much more comfortable with high-acuity patients.”

Claudia Stahl is SHM’s content manager.

A nationwide shortage of intensivists has more hospitalists stepping into the critical care arena, but not all with the level of preparation and comfort of David Aymond, MD, a Louisiana-based hospitalist trained in family medicine (HTFM).

Dr. Aymond gained his ICU experience in a fellowship with the University of Alabama, where hospitalists also “were responsible for ICU patients,” he said. Years later, as an employee of both small and large hospitals with busy ICU services, and a faculty member for a family medicine residency with a busy ICU, Dr. Aymond moves seamlessly between roles.

“It was eye-opening to learn how many [HTFM] are not only caring for patients in the ICU, but also are requesting additional training,” said Dr. Aymond, a member of the SHM Family Medicine Committee. “A critical care pathway would provide them with a level of expertise already available to physicians in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and surgery.”

With 71% of HTFM reporting that they round on ICU as the attending physician, the strong endorsement (78%) for critical care certification is not surprising.

“I am currently practicing as a full time intensivist and take consults from other providers, yet I only have a certificate from fellowship, no formal board certification in critical care,” noted a survey respondent.

Other participants stated, “it makes perfect sense to have a pathway to critical care if both family medicine and internal medicine coexist as hospitalists,” that certification is “imperative at rural and underserved hospitals,” and also “helpful for those …who work in larger hospitals and take care of critically ill patients.” More than half of those surveyed want the Family Medicine Committee to work with ABFM to create the pathway.

The majority (87%) of the HTFM survey respondents are certified by the ABFM, and 8% have attained Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine. Common pathways for additional credentialing include SHM’s Fellow of Hospital Medicine program (38%), a fellowship in hospital medicine (19%), and certification in hospice and palliative care (15%). More than 38% reported “other qualifications,” such as years of work experience, certification by the American Osteopathic Board of Family Physicians, and prior training in internal medicine.

The survey also found that certification differences in internal medicine and family medicine hospitalists, which may have posed employment obstacles in the past for HTFM, are not as much of an issue.

“The critical care pathway is the bigger concern,” Dr. Aymond said.

SHM’s Family Medicine Committee will be working on a proposal to ABFM to create the training pathway in the coming months. Dr. Aymond wants intensivists to know that this not an attempt to encroach on their professional domain, “but an opportunity to fill the existing professional gap.

Family medicine physicians are already providing critical care services, so a pathway to obtain formal training makes sense,” he adds. “If a family medicine doc completes the fellowship and takes it back to a residency program [the residents] will be more prepared for their potential careers in hospital and ICU medicine and much more comfortable with high-acuity patients.”

Claudia Stahl is SHM’s content manager.

A nationwide shortage of intensivists has more hospitalists stepping into the critical care arena, but not all with the level of preparation and comfort of David Aymond, MD, a Louisiana-based hospitalist trained in family medicine (HTFM).

Dr. Aymond gained his ICU experience in a fellowship with the University of Alabama, where hospitalists also “were responsible for ICU patients,” he said. Years later, as an employee of both small and large hospitals with busy ICU services, and a faculty member for a family medicine residency with a busy ICU, Dr. Aymond moves seamlessly between roles.

“It was eye-opening to learn how many [HTFM] are not only caring for patients in the ICU, but also are requesting additional training,” said Dr. Aymond, a member of the SHM Family Medicine Committee. “A critical care pathway would provide them with a level of expertise already available to physicians in internal medicine, emergency medicine, and surgery.”

With 71% of HTFM reporting that they round on ICU as the attending physician, the strong endorsement (78%) for critical care certification is not surprising.

“I am currently practicing as a full time intensivist and take consults from other providers, yet I only have a certificate from fellowship, no formal board certification in critical care,” noted a survey respondent.

Other participants stated, “it makes perfect sense to have a pathway to critical care if both family medicine and internal medicine coexist as hospitalists,” that certification is “imperative at rural and underserved hospitals,” and also “helpful for those …who work in larger hospitals and take care of critically ill patients.” More than half of those surveyed want the Family Medicine Committee to work with ABFM to create the pathway.

The majority (87%) of the HTFM survey respondents are certified by the ABFM, and 8% have attained Recognition of Focused Practice in Hospital Medicine. Common pathways for additional credentialing include SHM’s Fellow of Hospital Medicine program (38%), a fellowship in hospital medicine (19%), and certification in hospice and palliative care (15%). More than 38% reported “other qualifications,” such as years of work experience, certification by the American Osteopathic Board of Family Physicians, and prior training in internal medicine.

The survey also found that certification differences in internal medicine and family medicine hospitalists, which may have posed employment obstacles in the past for HTFM, are not as much of an issue.

“The critical care pathway is the bigger concern,” Dr. Aymond said.

SHM’s Family Medicine Committee will be working on a proposal to ABFM to create the training pathway in the coming months. Dr. Aymond wants intensivists to know that this not an attempt to encroach on their professional domain, “but an opportunity to fill the existing professional gap.

Family medicine physicians are already providing critical care services, so a pathway to obtain formal training makes sense,” he adds. “If a family medicine doc completes the fellowship and takes it back to a residency program [the residents] will be more prepared for their potential careers in hospital and ICU medicine and much more comfortable with high-acuity patients.”

Claudia Stahl is SHM’s content manager.

Sneak Peek: The Hospital Leader Blog

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on “The Hospital Leader” blog. Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

In December, I wrote a letter to hospital executives, urging them to deliberately invest their own personal time and effort in fostering hospitalist well-being. I suggested several actions that leaders can take to enhance hospitalist job satisfaction and reduce the risk of burnout and turnover.

Following publication of that post, I heard from several hospital executives and was pleasantly surprised that they all responded positively to my message. Several execs told me that they gained valuable new insights about their hospitalists’ challenges and needs; others said they planned to take action on one or more of my suggestions that had never occurred to them before.

Their feedback reinforced my belief that most hospital leaders actually do care a lot about promoting healthy, stable, and sustainable hospitalist programs, but the hospital leaders I talked with also had some messages for their hospitalist colleagues, and I think it’s important to share them in the spirit of fostering a healthy exchange of perspectives. Your hospital’s leaders would be delighted and encouraged if you engaged them in dialogue about these issues.

Help us help you

Several hospital leaders told me that their hospitalists grumble about being treated by the medical staff (and even nurses) like second-class citizens or glorified residents. Those same hospitalists, however, routinely show up for work dressed in scrubs and tennis shoes rather than professional attire. They rarely come in early when it’s busy or invest more time than is absolutely needed to see the patients on their list, making it easy for others to dismiss them as shift workers.

Hospitalists, they say, are unwilling to come in on their own time to attend a medical staff meeting, something other doctors do as a matter of course. And instead of interacting as social peers with other physicians when opportunity arises (i.e., in the cafeteria or doctors’ lounge), the hospitalists just grab food and head back to eat together in their work room.

The executives said they want to help enhance the stature of their hospitalists within the medical staff, but the Here’s a typical comment:

“[Hospitalists] also need to be willing to participate in hospital and system committees. Although this may require them to interrupt their workflow and stay late on some days they are working or come in on days off, they will never garner the respect of their colleagues if they are unwilling to do so.”

Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

Leslie Flores is a hospital medicine consultant and member of SHM’s Practice Analysis Committee.

Also on The Hospital Leader. . .

• Creating Value through Crowdsourcing & Finding ‘Value’ in the New Year, by Vineet Arora, MD, MPP, FHM

• BREAKING NEWS: “Physicians Deemed Unnecessary”; Social Worker Promoted to Hospital CEO, by Jordan Messler, MD, SFHM

• ER Docs and Out-of-Network Billing: Are We in the Same Boat?, by Brad Flansbaum, DO, MPH, MHM

• The Best Way to Die?, by David Brabeck, MD

Editor’s note: This article first appeared on “The Hospital Leader” blog. Read the full post at hospitalleader.org.

In December, I wrote a letter to hospital executives, urging them to deliberately invest their own personal time and effort in fostering hospitalist well-being. I suggested several actions that leaders can take to enhance hospitalist job satisfaction and reduce the risk of burnout and turnover.

Following publication of that post, I heard from several hospital executives and was pleasantly surprised that they all responded positively to my message. Several execs told me that they gained valuable new insights about their hospitalists’ challenges and needs; others said they planned to take action on one or more of my suggestions that had never occurred to them before.

Their feedback reinforced my belief that most hospital leaders actually do care a lot about promoting healthy, stable, and sustainable hospitalist programs, but the hospital leaders I talked with also had some messages for their hospitalist colleagues, and I think it’s important to share them in the spirit of fostering a healthy exchange of perspectives. Your hospital’s leaders would be delighted and encouraged if you engaged them in dialogue about these issues.

Help us help you

Several hospital leaders told me that their hospitalists grumble about being treated by the medical staff (and even nurses) like second-class citizens or glorified residents. Those same hospitalists, however, routinely show up for work dressed in scrubs and tennis shoes rather than professional attire. They rarely come in early when it’s busy or invest more time than is absolutely needed to see the patients on their list, making it easy for others to dismiss them as shift workers.